Abstract

The development of point-of-care testing technologies can enable early diagnosis and regular monitoring of disease course and the response to medications. However, the need for a reliable home-based diagnostic technology that can be integrated with healthcare systems remains unmet. Urine is a rich bodily fluid containing distinctive biomarkers and nutrients, which can be obtained through non-invasive sampling. Here, strategies to re-engineer toilet systems for applications in health monitoring are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biochemical testing of bodily fluids has transformed modern medicine by enabling precise detection and monitoring of disease and response to treatment (i.e., medications). Urine is a valuable biological fluid and contains various nutrients and disease biomarkers formed as a result of metabolic processes1,2,3,4. This rich body fluid has varying concentrations of electrolytes (Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, and Cl− ions), nitrogenous chemicals (urea and creatinine), vitamins, hormones, and organic acids (e.g., uric acid)5,6,7. The concentrations of compounds can vary from day to day and person to person, depending on diet, physical activity, health status, and environmental conditions5. Owing to its abundant biological properties, urinalysis can enable the early identification of diseases, such as urinary tract infections, acute kidney disease, chronic kidney disease, or diabetes, and provide valuable information regarding chronic medical conditions. While the use of urinalysis is common in hospitals and clinical settings, its application in at-home continuous health monitoring and point-of-care (POC) testing has remained underexplored. Traditional laboratory based urinalysis assays have some caveats, including their reliance on centralized facilities and trained personnel, delayed turnaround times, and high costs for longitudinal monitoring applications8. Recently, the development of POC urine analysis or at-home urine analysis systems has attracted widespread attention. By integrating strategies such as microfluidics and machine learning (ML) applications into urinalysis platforms, recent studies have addressed some challenges associated with traditional laboratory testing9,10,11. Studies have highlighted the potential of at-home health monitoring using smart sanitary hardware such as sensor-integrated toilets or non-expert-user-friendly rapid urinalysis kits9. Such tools have shown great promise in advancing personalized healthcare by enabling continuous, real-time tracking of physiological biomarkers12. In addition to individual health management, recent technological advancements also can also enable population-level applications8. A prominent focus within community health monitoring has been wastewater-based epidemiology, which enables population-level disease surveillance through the analysis of biomarkers in communal sewage systems13,14.

Here, we review the applications of sewage and toilet systems, highlighting established analytical strategies and emerging tools. We discuss emerging smart sanitary hardware technologies and their role in health monitoring, potentially addressing the demand for decentralized user-friendly real-time health monitoring. Furthermore, we explore emerging applications of artificial intelligence (AI) in novel urinalysis platforms.

Point-of-care and longitudinal health monitoring

Regular screening of human waste, such as urine and stool, which are produced in large volumes on a daily basis can allow the early detection of disease, increase healthcare delivery, and improve patient well-being12. Early detection not only improves patient outcomes, but it can also help reduce the cost of healthcare and the burden on centralized healthcare centers by eliminating more expensive treatments and hospital visits12. Technologies developed with this goal in mind have huge potential to improve overall health of communities and individuals and can be integrated into sanitation infrastructure, enabling continuous long term waste monitoring9,12. Integrating such technologies into daily routines and preexisting infrastructure demands innovative engineering and design strategies to create the next generation of toilet and wastewater systems. However, integrated smart toilets and wastewater systems for both diagnostic settings and energy-efficient sustainable wastewater resource recovery pose huge challenges, such as sample heterogeneity and biomarker degradation, sensor fouling and signal instability in complex matrices, high energy and maintenance demands, difficulties in data integration and privacy protection, and the lack of standardized frameworks for clinical validation, biosafety, and large-scale implementation. Challenges arise due to the complex nature of the technology, infrastructure requirements, and social factors involved. Several key aspects need to be addressed to overcome such challenges and unlock the full potential of integrated smart toilets and wastewater systems.

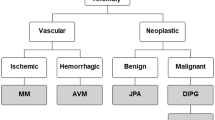

Several strategies have been developed to analyze urine for diagnostic, screening, and monitoring purposes (Leveraging the biological properties of urine for diagnostics, screening, and health monitoring). Traditional biochemical and reagent based assays provide rapid and low-cost detection of specific analytes (Reagent strips). Microscopic analysis enables morphological evaluation (Microscopic analysis). Advances in biosensors and smart sanitary technologies have expanded urine diagnostics toward automated, sensor-integrated, and network-connected systems (Smart toilets), supporting applications in anti-fouling surface design (Anti-fouling) and population-level monitoring through wastewater based epidemiology applications (Wastewater-based epidemiology).

Leveraging the biological properties of urine for diagnostics, screening, and health monitoring

Kidneys not only regulate blood pressure and water homeostasis but also offer an important homeostasis mechanism of the body and play an indispensable role filtering out toxic substances from the blood15,16. Therefore, by analyzing the appearance (clear vs. turbid), amount, density, and constituents (i.e., glucose, nitrites, protein, etc.) of urine, it is possible to monitor overall health, screen for a medical condition (i.e., diabetes, chronic kidney disease), and monitor a treatment (i.e., renally excreted medications)8. A healthy individual who takes about 2 L of fluid per day, will filter 200 L of fluid in 24 h and produce between 0.75 and 2 L of urine17. Over 100 metabolites have been identified in the human urinary metabolome, and 3429 different proteins and more than 10,000 peptides have been uniquely identified in the human urinary proteome18. More than 99% of the substances dissolved in urine consist of 68 analytes, mainly 42 compounds, with minimum concentrations of 10 mgL−1 19. The kidneys regulate internal homeostasis by filtering the blood through a multistep process comprising glomerular ultrafiltration, tubular reabsorption, and tubular secretion, which together facilitate the excretion of metabolic waste products while conserving water and essential solutes. In addition to their excretory role, the kidneys synthesize and release hormones that modulate blood pressure, erythropoiesis, and systemic electrolyte and acid–base balance20. In addition to providing information about metabolism, nutrition, kidney function, urine samples play a critical role in diagnosing urinogenital diseases, neurological disorders, cardiovascular disorders, musculoskeletal diseases, and integumentary diseases18.

The color of urine ranges from pale yellow to amber, due to the urochrome pigment. In urine, coloration and turbidity can indicate dehydration, an infection, or metabolic disease, the presence of red blood cells, white blood cells, or bacteria17. Urine production below 0.75 L in 24 h indicates conditions such as dehydration, infection, obstruction, renal stones, kidney failure, or stenosis17. Accurate pathogen-level identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing remain central to urinary tract infection diagnostics, but conventional urine culture typically requires 24–72 h and may miss polymicrobial pathogens21,22. While molecular POC tests (including PCR and CRISPR-based assays) offer high sensitivity and shorter turnaround times, unlike respiratory or blood infections, urinary pathogen identification is still predominantly culture-based, and molecular assays are not yet widely adopted as first-line diagnostics in clinical microbiology laboratories. Therefore, POC assays are useful for detecting that an infection is likely present, but they do not typically determine the exact infectious agent.

Besides the analytical and microscopic analysis, appearance and quantification of the urine samples have provided a decisive and guiding screening method over the last century23,24. Recent advancements in ML, AI, and digital microscopy can enable the automated analysis of both macroscopic and microscopic characteristics of urine, providing objective, reproducible diagnostic information25,26. Quantitative and qualitative examination of urine is an effective method in the evaluation of many pathological conditions such as diabetes, infections, kidney and liver dysfunction, hereditary diseases, genitourinary system cancer, and sexually transmitted diseases17,23,27,28,29,30. Urine can also be used to measure substances such as glucose, protein, blood, drugs of abuse, and medications17,23,27,28,29,31,32,33.

Urine’s molecular complexity and non-invasive accessibility provide a foundation for developing sensitive diagnostic tools; understanding its biological composition is critical for optimizing downstream biosensing and analytical technologies.

Reagent strips

Reagent strips are solid-phase colorimetric sensors in which reagent-impregnated pads undergo visible color changes upon reacting with urinary analytes such as glucose, protein, or nitrite34. Strips are often low-cost assays and remain a mainstay of POC urinalysis, enabling rapid biochemical screening in both clinical and home settings35. Reagent strips are the most common method used in urinalysis (Fig. 1), and many strips are commercially available36,37. The color change on the reagent strip is determined after immersion in the urine sample, representing a fast, cost-effective, and easy-to-apply method28,38. The color change can be detected with the naked eye or with an electronic reader, adhering to the color chart based on pre-determined concentration ranges. However, the analysis must be done within 1 h after collection, and the immersion time of the reagent strip and the reading time must be accurate38. Reagent strip is the most widely used method for the determination of pH value, urobilinogen, glucose, bilirubin, ketones, blood, protein, nitrite, and leukocyte concentrations in urine39. The presence of glucose, bilirubin, ketones, blood, protein, nitrite, and leukocytes in the urine can be a sign of serious metabolic or infectious diseases17. Although sensitivity is approximately 85%, it plays an active role in the detection of blood in urine (hematuria) due to its simplicity and low false negative rate28,40. However, microscopic and endoscopic (cystoscopy) imaging is recommended in high-risk patients due to the relatively higher false positive rate28. The lateral-flow assay is another simple urine-based test utilized as a pregnancy test that can be administered at home41. Compared with lateral flow assays, dipsticks are more prone to false-positive results due to interfering substances28. In lateral flow assays, the analyses of exogenous chemicals, drug, and doping, drug interactions, therapeutic dosing, and nutrition requires high-cost complex clinical chemistry equipment that includes spectrometric and chromatographic platforms38,42. Proteomic, transcriptomic, and multiplexed platforms can allow for the determination of biomarkers of cancer types (ovarian, bladder, and breast), in which the survival rate increases significantly with early detection43,44,45,46,47. Studies to identify a combination of multiple urinary biomarkers (e.g., ANXA3, sarcosine, gene fusions, PCA3) for the type of prostate cancer, in which tumor cells are shed in urine, are promising in early disease detection48,49. Although reagent strips offer rapid, inexpensive screening, their qualitative nature and susceptibility to user error highlight the need for quantitative and automated biosensing alternatives.

Rapid POC testing can be achieved through the use of reagent strips and lateral flow tests, which can enable the detection of acute changes in urine metabolites. Intelligent hardware (i.e., sensors) can be integrated into toilets to facilitate automated urinalysis and tracking of health parameters. Wastewater based epidemiology can enable community-level health tracking. Machine learning (ML)-based applications can improve capabilities of traditional urinalysis, and smartphone-based testing can offer easy user access. This figure was designed using BioRender.

Microscopic analysis

Microscopic imaging of urine is a widely used method for the diagnoses of diseases affecting the urogenital system. Microscopic analysis of urine includes screening for white blood cells in urinary tract infections, glomerulonephritis, vaginal and cervical infections, and infections of the external urethral meatus (men and women), bacteria for abundant normal microbial flora of the vagina or external urethral meatus; yeast for infection, renal tubular epithelial cells for nephrotic syndrome, evidence of tubular degeneration, crystals (calcium oxalate, triple phosphate, amorphous phosphates, uric acids) for hypercalcemia, and cystine crystals for renal failure17. Another analysis technique deploys smartphones with easily accessible and built-in sensors to reduce reliance on centralized healthcare settings and laboratory instrumentation (Fig. 1)50,51,52,53,54. An image of the reagent strip or paper-based microfluidic device can be taken by a smartphone camera and analyzed by a mobile application developed specifically to interpret colorimetric results52,53,54. In one study, off-the-shelf electronics and smartphones were utilized in combination with loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) for urinary sepsis monitoring50. In this study, to assess pathogen ID, freshly collected urine specimens were lysed with NaOH and detergent. Treated samples were heated to generate fluorescence intensity changes that varied according to specific gene concentrations under LED illumination. Finally, fluorescence signals were obtained by using smartphone camera to process and detect pathogen ID using a coarse derivative algorithm that can quantitatively determine concentration of gDNA. Therefore, pathogen ID was detected by an off-the-shelf hardware that consisted of a housing, a heating block, LEDs, and a smartphone camera. Integrating such a system into a urine-diverted toilet can eliminate user-induced contamination and the need for a healthcare professional during sample collection and analysis. Microscopic urinalysis remains an indispensable diagnostic tool, yet automation and digital image analysis are essential for improving reproducibility and integrating morphology with molecular findings. Such technologies may complement the requirement for diagnostic applications such as blood analysis or subsequent medical imaging and biopsy in the screening and follow-up of kidney failure and cancer types, where the early detection is critical.

For any given application, selecting the most appropriate diagnostic modality is essential to improve patient outcomes. While clinical laboratory methods offer high analytical accuracy and standardized workflows, they require trained personnel (typically) larger sample volumes, longer turnaround times, and higher operational costs55,56,57. POC at-home tests are often rapid, user-friendly, and cost-effective, yet sacrifice specificity and quantitative ability. Emerging lab-on-chip and microfluidics systems aim to bridge the gap between POC and centralized testing.

Smart toilets

Lab-on-chip inspired devices and sensors can be designed and inserted into toilets to seamlessly monitor target compounds (Fig. 1)33,58,59,60. Achieving the capability of processing samples directly collected from patients would eliminate the need for high-cost facilities and complex and time-consuming procedures, while significantly reducing healthcare costs associated with transportation, storage, and maintenance of clinical chemistry instruments12,60,61,62.

In general, urine is a sterile product, unlike feces, which may contain various pathogens depending on the prevalence of infectious diseases in a given population. Therefore, the first step in developing a smart toilet involves the adoption of a urine-diverting toilet system, which is used to prevent urine from mixing with feces prior to sampling and analysis. The establishment of urine monitoring toilet systems can enable analysis by quantity, appearance, and chemical components. Such urine monitoring systems can contribute to monitoring health status of individuals and provide early diagnosis of diseases8,12,63,64. Applications can also be expanded into community-level health monitoring through wastewater epidemiology14,65,66. Integrating urinalysis technologies into toilets can enable a holistic approach for mass-scale disease screening. Urine may also contain small amounts of hormones, drug residues, and heavy metals, which can prove useful for wastewater-based epidemiology and community-level health monitoring applications.

One smart-toilet design by Park et al., proposed a proof-of-concept demonstration of a toilet based device9 utilizing two high-speed cameras for assessing uroflowmetry, urinalysis, and stool-form analysis using computer vision algorithms and urine strip (Fig. 2a)9. To assess the performance of their proposed uroflowmetry module, the researchers conducted a study involving simulated urination events within a typical range of 50–670 ml and real urinations from ten male participants aged 19–40. This study included a total of 31 urination events by the participants and 68 simulated streams conducted over a 5-week period. They estimated the flow rate by analyzing pixel counts in specific areas of each video frame and applying cross-correlation analysis. A comparison between an image generated by the standard uroflowmeter and one generated using computer-vision uroflowmetry showed a significant correlation, although some disparities were observed during the terminal dribbling phase. Nevertheless, voiding times recorded by both standard and computer-vision uroflowmetry exhibited a strong linear correlation with the number of video frames, offering valuable insights into prostate and bladder functions. Furthermore, their algorithm accurately determined the total voided volume by using depth- and flow-rate-adjusted pixel data from synchronized video frames. This method displayed a linear correlation with the total voided volume measured via standard uroflowmetry. Notably, discrepancies primarily arose with urine streams of extremely high flow rates, which could potentially be addressed by using a higher-frame-rate camera and optimizing the camera’s field of view. In addition, the researchers trained two independent deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) using separate gold standards provided by surgeons. To evaluate the CNNs’ classification performance, they enlisted six medical students with a minimum of 2 years of medical school training to grade stool images based on the Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS). The CNNs’ predictions were compared with those of the medical students. Despite the students’ initial lack of familiarity with BSFS grading, the CNNs outperformed the untrained students in the training sets and achieved similar results to trained medical students in the test sets. The outcomes can be correlated with total bowel transit time, which can be an indicator of irritable bowel syndrome, HIV-related diarrhea, and fecal incontinence59,60. Although the workflow is seamless, accurate, and repeatable, the major drawback of such design is the utilization of cameras for identifying each different individual, where the identification process is handled by a camera that captures an image of user’s anal silhouette (analprint) and fingerprint. In general, surveys have shown that the overwhelming majority of the participants are unlikely to prefer devices that utilize direct biometric identification methods such as camera, voice recognition, and fingerprint compared to the indirect approaches such as distance between the user’s heel and toilet bowl, rotating a flush lever, duration of lavatory usage, weight distribution sensed by mountable toilet seat and pulling technique for paper roll62.

a A perspective depiction of a toilet equipped with a device designed for continuous monitoring of human excreta baseline parameters9. This toilet system comprises several key components: A 10-parameter test-strip-based urinalysis with a retractable cartridge, computer-vision uroflowmetry featuring two high-speed cameras (the blue dashed lines indicate the field of view for each camera), stool classification accomplished through deep learning (the blue dashed lines denote the field of view of the defecation monitoring camera), measurement of defecation duration using a pressure sensor located beneath the toilet seat (the red arrow signifies the force detected by the pressure sensor), two biometric identification methods: an analprint scan (represented by the green box, utilizing a template-matching algorithm) and a fingerprint scanner integrated into the flush lever. b A design for utilizing toilets as continuous health screening platforms. (i) Seamless sample collector design that can be easily integrated into toilets to prevent cross contamination effects. (ii) Photograph of full experimental setup consisting of acrylic holder, phial turret, collector, flush water pump, sample pump, and peristaltic collector pump powered by a DC motor. (iii) An imaging box to block outside light while capturing an image of an inserted dipstick to quantify protein concentration. Tests for colorimetric detection methods are also conducted to prove accurate diagnostics. Reprinted from ref. 11 under CCBY 4.0 license.

Restricting camera usage from toilet may necessitate the development of indirect approaches that are not associated with privacy concerns. One of these approaches is to separate the urine and transfer it to a sample collector with a module integrated into the toilet11. The integrated sample collector is painless and offers a non-body contact method; hence, it is likely to be compatible with the user’s behavioral preferences. This system, shown in Fig. 2b, is designed as a cylindrical reservoir that can be mounted on the side wall of an existing toilet bowl and is easy to target while the person is urinating, the collected samples can then be routed to a dedicated urinalysis module11,12. The analysis module can be integrated either internally or externally within the toilet system. Figure 2b illustrates an internal system designed for measuring protein concentration in urine11. To enable long-term cyclic use of the sample collector, it is attached at a 10° angle using a mounting plate fixed on a plastic tray to contain the water. The setup includes a vial holder capable of accommodating eight vials and one draining tube for uncollected liquid. A servo motor is affixed to the bottom of the vial holder, enabling a 20° clockwise rotation for each sample collection. A peristaltic pump, controlled by a speed reduction DC motor, is assembled to transfer protein samples from the collector to the turret via thermoplastic tubing. The holder, collector pump, and turret are securely attached to a breadboard. A submersible water pump is utilized as the sample pump, employing polyurethane tubing to transfer protein samples from the sample container to the collector. Additionally, a flush water pump, drawing water from the water reservoir, is employed to clean the collector after protein sample collection by directing the water toward the collector via tubing.

An alternative example of an analysis module that can be integrated with the sample collector entails employing a colorimetric detection technique within the toilet’s design (Fig. 2b)11. This analysis of the test strip could be performed using RGB sensors that can easily quantify analyte concentrations by reading digital red, green, blue hues of the sensing regions. This colorimetric sensing method was validated by Temirel et al. utilizing an imaging box, a built-in camera, and commercial urine strips, where solutions with different standard bovine serum albumin (BSA) concentrations were applied to urine pad and then fed into imaging box to observe color changes11. Results showed that different compound concentrations yielded distinguishable color changes. Due to direct urine-equipment contact requirements of the proposed design, extra care is needed for eliminating cross contamination effects. To assess the cross-contamination elimination capabilities of the proposed design, the main part responsible for collecting urine samples was filled repeatedly with BSA solution with various concentrations, followed by 2 s flushing to rinse the leftover water. Finally, samples were gathered from the water that was left after rinsing and draining. Results revealed that the sample collector holds ~250 μL of leftover water with almost zero BSA concentration. Furthermore, those leftover samples did not cause any color change in urine dipsticks; thus, a sample collector was developed for holding urine samples and colorimetric analysis. However, this design did not include any approach regarding the identification and scalability of the detection mechanism.

Smart toilets represent a transformative interface between users and digital health ecosystems, though challenges in sensor integration, hygiene, data privacy, and standardization must be addressed for clinical translation. In addition to technical considerations, smart toilet implementation must address user-related and anatomical challenges, including differences in urine flow and collection between men and women, as well as limited applicability in children and elderly individuals who may rely on diapers or assisted care. Hybrid systems that integrate toilet-based sensing with wearable or diaper-embedded biosensors have been proposed to extend monitoring beyond conventional toilet use67. While wearable sensors have been explored in various context, further validation is required for urinalysis applications68.

Anti-fouling

Anti-Fouling is a surface coating strategy used to prevent the deposition of unwanted proteins, microorganisms, and cell-like substances on the surface and to minimize contamination as much as possible69. Antifouling has enabled significant progress in the performance, reusability, and longevity of microfluidic devices. This approach, which ranges from surface coatings and liquid-infused films70,71 to capillary-stabilized liquid Gates72 and magnetically actuated cilia73 and enzyme-based cleaning methods74, when combined with microfluidic technology, prevents nonspecific adhesion of biological materials such as blood, mucus, proteins71,75, and microorganisms73 while maintaining critical functions such as real-time detection76, sample processing, and optical clarity in clinical and laboratory settings. Applications include blood-contact catheters69,70, endoscopic lenses70,71, lab-on-a-chip systems72,73, electrochemical biosensors76, and digital microfluidics77, and many platforms have been successfully validated in vivo. Microfluidic chips have been engineered with antifouling strategies for use in biomedical applications (Fig. 3).

a Disposable glass-coverslip lubricant coatings on endoscopes: mounting with PDMS; performance of 350 cSt and 500 cSt silicone-oil coatings vs uncoated (red), noting transient aberrations from droplet pinning/detachment. Adapted from ref. 70. Copyright (2016) National Academy of Sciences. b Magnetic artificial cilia (MAC): (i) SEM side view (Ø50 μm, h = 350 μm, pitch = 250 μm); (ii) Bright-field after 28 days actuation, showing reduced algae fouling; (iii) Antifouling over time for partial MAC coverage. Adapted from ref. 73 under CC BY license. c Protein-fouling mitigation in PDMS chips: (i) Protein in effluent after 20 mg/mL BSA, 10 min, 1 mL/min; (ii) Total uptake after cleaning (10 mL); (iii) Six cleaning cycles comparing untreated vs PLL-g-PEG-treated; (iv) Cumulative uptake with/without pretreatment and trypsin post-treatment. Adapted from ref. 74 with permission. d (i) Two-step mechanochemical activation and grafting render PDMS antibiofouling; (ii) demonstration on a toilet bowl. Adapted from ref. 72 with permission.

Applications include omniphobic coatings applied to catheters and tubes, preventing clot formation and biofilm adherence75, silicone-based liquid coatings applied to keep the lens surface clean during repeated tests with blood (Fig. 3a)70, magnetic artificial cilia integrated into the surface repelling microalgae from the surface (Fig. 3b)73, and microfluidic chips reducing protein contamination after washing (Fig. 3c)74. Antifouling can also facilitate personalized treatments by continuously and instantly monitoring serum drug concentrations. The purpose of this microfluidic sensor system is to prevent biological substances, such as blood cells and proteins, from adhering to the sensor surface and to ensure the target molecules are distributed uniformly across the sensor surface. This prevents biofouling and maintains accuracy during measurements76. SLIPS (Slippery Liquid-Infused Porous Surfaces) film used in the digital microfluidic system prevented biomolecule adhesion by preventing both conductive and insulating droplets from contacting the surface. This approach enabled smooth liquid transfer over long cycles77. Ball milling can also be used to apply and activate poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) on ceramic and glass surfaces, the researchers created a durable, water-repellent coating that significantly reduces bacterial adhesion by mechanically breaking siloxane bonds in PDMS without the need for any solvents and high temperatures (Fig. 3d). Maintaining its transparency and not affecting the appearance of the substrate, this coating achieved a 100,000-fold reduction in bacterial adhesion from urine samples when applied to a real ceramic toilet bowl. This result makes it ideal for protecting embedded sensors and microfluidic channels in toilet-based PoC systems72. Liquid-infused membranes have been shown to demonstrate an antifouling effect by reducing the surface accumulation of substances such as proteins, particles, and blood in microchannels. Images show virtually no bioaccumulation on the liquid-coated surfaces78.

Effective anti-fouling design is fundamental to ensuring sensor reliability, long-term performance, and maintenance-free operation in smart sanitary and wastewater diagnostic systems. Environmental factors such as water quality, mineral deposits (e.g., limescale), and cleaning chemicals can interfere with sensor accuracy and longevity, highlighting the need for antifouling materials, self-cleaning designs, and standardized maintenance protocols79.

Wastewater-based epidemiology

The sewage problem has become a serious public health concern in rapidly developing industrial societies and urban areas. Especially with the increase of epidemic diseases, it has become imperative to solve this problem with a modern system. Despite the public health benefits of separating clean and dirty water via integrated wastewater treatment plants, rapid increase in the world population has inevitably resulted in wasting of clean water. Initially, quickly disposing of urine along with other wastes such as excreta and toilet paper to the sewer system by a large amount of clean water seemed quite practical. The value of urine, historically used in fertilizing crops, tanning leather, washing clothes, and making gunpowder in some societies, has regained popularity following studies on the use of urine as a diagnostic medium and raw material source in soil fertilizing and electricity generation. To constitute such a system, urine processing facilities should be integrated with urine-diverted toilets that separate urine from other wastes80. Such strategies can save and recycle a significant amount of water and nutrients, as well as increase the lifespan of existing sewer systems by reducing the total load81. Sewers also have significant potential to be used as a platform to assess public population-level indicators that provide insights into health trends82,83,84,85, drugs85,86, and pharmaceuticals use83. These indicators would be helpful for policymaking to provide a set of solutions for existing or urgent public health concerns due to sanitation issues, drug overuse, antibiotic resistance, and pathogens83,84,85,87.

Monitoring sewage for both solid and liquid compounds by applying bioanalytical measurement methods such as liquid chromatography, mass spectroscopy, and PCR reveals the presence of viral compositions85,86,87,88. Measurements can be stored for long-term monitoring to track the effects or progress of the certain decisions or actions. Quantifying metoprolol acid in sewage to estimate hypertension prevalence in the population aged over 15 years by Hou et al. showed that 28 ± 10% of the population had hypertension while the result of the China Hypertension Survey was indicated as 28%83. Consistent estimation results have been achieved for various target compounds such as alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, pharmaceuticals, and drugs83. Target analytes can be quantified at trace levels (ng L−1) in a consistent fashion. Thus, sewage monitoring or wastewater epidemiology can serve as indicators of public health trends82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89. Although some of the target analytes or agents of interest may be degraded due to sewer conditions, chemical compounds that can be used as drug biomarkers in wastewater can be considered as comparably stable and preserved8. A challenge is to locate target biomarkers inside a complex wastewater matrix since a wide range of inorganic, chemical, and biological substances are present. The target substance, such as fat, protein, and other chemicals, must be extracted from the matrix while utilizing PCR analysis8789. However, high complexity also illustrates the possibility of extracting numerous valuable insights regarding the health status of a community. Therefore, potential biomarkers (e.g., proteins) in wastewater would be a valuable metadata collection resource that can enhance accuracy and effectiveness of policymakers and provide well suited set of solutions.

WBE offers unprecedented insight into community health dynamics, yet harmonization of sampling protocols, biomarker normalization, and data interpretation remains essential for actionable epidemiological intelligence. However, privacy and ethical concerns must be addressed by considering social perceptions and adoptions, such as eliminating direct identification in waste analysis for both diagnostics and overall wastewater monitoring10,90,91. Innovative and indirect sampling systems are required instead of relying on cameras or other direct identification protocols12.

Emerging technologies

Urine diversion combined with the emerging technologies such as microfluidic chips, IoT based edge devices, ML algorithms, and biosensors, indirect workflows can be adopted for at-home settings where all the required infrastructure is readily available92. These technologies must contain strict privacy procedures during diagnostic testing in toilets for early disease screening. With this goal in mind, those platforms can be easily integrated into people’s daily lives and reduce the workload of centralized healthcare centers, and eliminate troublesome, time-consuming, and costly procedures while significantly contributing to healthcare expenditure reduction12.

Artificial intelligence (AI) in diagnostics

Advances in algorithm hardware infrastructure and computing capabilities, along with data from wearable biosensors, medical imaging technologies, individual health records, and public health institutions, have paved the way for more effective use of biosensors in healthcare93,94. Advanced models can successfully detect complex patterns, monitor bodily electrophysiological and electrochemical signals, and detect low-level trends and anomalies by processing large datasets at high speed. Consequently, they can significantly increase the real-time predictive accuracy of biosensors94. Models, which enable the wider use of biosensors, have the potential to radically transform diagnostic processes by integrating them into POC biosensors, enabling capabilities such as data processing, quantitative analysis, instant decision-making, and adaptive sensing. Furthermore, they enable rapid, low-cost, reliable, and easily accessible assessment of patient-specific health status93,95,96. Traditional urinalysis methods, such as manual microscopy and visual dipstick interpretation, are limited by operator variability, subjective assessment, and lack of longitudinal data integration. AI-driven platforms address these limitations by enabling automated sediment analysis, digital interpretation of reagent strips, biomarker prediction, and integration within smart toilet and connected health systems9,12.

One of the promising applications of AI in urinalysis leverages AI-enhanced imaging technology. Super resolution Faster Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) has been used to detect and classify urine sediments97. Similarly, a deep learning (DL) classification algorithm that employed CNNs was developed to enable optimal parameter tuning for urinary sediment classification98. However, for strategies involving CNNs, large sets of manually annotated data are typically required, which increases the computational burden of systems. To overcome this issue, a model named YOLOv5 was developed using an evolutionary genetic algorithm99. The hyperparameter optimization model was faster and better automated for microscopic urinalysis compared to other counterparts. Other image-based diagnostic platforms have focused on utilizing ML-enhanced Surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) for early-stage bladder cancer detection in endoscopic images100. SERS-based strategies have also proved useful for the label-free detection of cancer biomarkers in urine, saliva, and blood samples101,102. ML-based strategies have been employed to automate the traditional urinalysis pipeline. The development of gravity sedimentation cartridges has enabled centrifugation-free urinalysis and eliminated the need for experienced technicians to prepare samples103. Following uptake of samples, an AI-based object detection model was used to auto-analyze reports and deliver results. Such automated processes can enable POC testing as well as at-home testing for non-experts, reducing the reliance on complex laboratory infrastructure. Several studies have also used ML to achieve predictive modelling for health conditions, including kidney disease104,105. Seamless, at-home or POC urinalysis that feeds algorithms with data can enable earlier disease detection and personalized health decisions106,107,108,109.

Conclusion

Urine-based diagnostics offer significant advantages, including non-invasiveness, low cost, minimal sample volume, and potential for continuous, decentralized health monitoring, and therefore, can enable early disease detection, longitudinal surveillance, and personalized healthcare decision-making. However, their clinical translation and widespread adoption are limited by several challenges: variable sensitivity and specificity in POC tests, sensor degradation in continuous-use environments, data privacy concerns, and user reluctance. Mitigation strategies include implementing anti-fouling coatings, microfluidic pre-processing, and AI-based result interpretation. For successful fundamental integration, it is critical to develop user-friendly, easy-to-maintain, and odorless systems.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Larsen, T. A., Lienert, J., Joss, A. & Siegrist, H. How to avoid pharmaceuticals in the aquatic environment. J. Biotechnol. 113, 295–304 (2004).

Karak, T. & Bhattacharyya, P. Human urine as a source of alternative natural fertilizer in agriculture: a flight of fancy or an achievable reality. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 55, 400–408 (2011).

Lind, B.-B., Ban, Z. & Bydén, S. Volume reduction and concentration of nutrients in human urine. Ecol. Eng. 16, 561–566 (2001).

Von Münch, E. Basic overview of urine diversion components (waterless urinals, UD toilet bowls and pans, piping and storage). Sustain. Sanitation Alliance 4, 1–24 (2009).

Rose, C., Parker, A., Jefferson, B. & Cartmell, E. The characterization of feces and urine: a review of the literature to inform advanced treatment technology. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 1827–1879 (2015).

Gao, Y. in Urine Proteomics in Kidney Disease Biomarker Discovery (ed Youhe G.) 3–12 (Springer, 2015).

Sarigul, N., Korkmaz, F. & Kurultak, İ. A new artificial urine protocol to better imitate human urine. Sci. Rep. 9, 20159 (2019).

Yigci, D., Bonventre, J., Ozcan, A. & Tasoglu, S. Repurposing sewage and toilet systems: environmental, public health, and person-centered healthcare applications. Glob. Chall. 8, 2300358 (2024).

Park, S. M. et al. A mountable toilet system for personalized health monitoring via the analysis of excreta. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 624–635 (2020).

Ge, T. J. et al. Passive monitoring by smart toilets for precision health. Sci. Transl. Med. 15, eabk3489 (2023).

Temirel, M., Yenilmez, B. & Tasoglu, S. Long-term cyclic use of a sample collector for toilet-based urine analysis. Sci. Rep. 11, 2170 (2021).

Tasoglu, S. Toilet-based continuous health monitoring using urine. Nat. Rev. Urol. 19, 219–230 (2022).

Lorenzo, M. & Picó, Y. Wastewater-based epidemiology: current status and future prospects. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 9, 77–84 (2019).

Choi, P. M. et al. Wastewater-based epidemiology biomarkers: past, present and future. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 105, 453–469 (2018).

Renkin, E. M. & Robinson, R. R. Glomerular filtration. N. Engl. J. Med. 290, 785–792 (1974).

Jamison, R. L. & Maffly, R. H. The urinary concentrating mechanism. N. Engl. J. Med. 295, 1059–1067 (1976).

Baig, A. Biochemical composition of normal urine. Nat. Preced. https://doi.org/10.1038/npre.2011.6595.1 (2011).

Mathai, T. Disease Markers in Urine. 38 (Department of Biosciences and Bioengineering, Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay, Indian Institute of Technology, 2020).

Thomas, L. “Urine Composition: What’s Normal?”, (2022).

Balcı, A. K. et al. General characteristics of patients with electrolyte imbalance admitted to emergency department. World J. Emerg. Med. 4, 113–116 (2013).

Szlachta-McGinn, A. et al. Molecular diagnostic methods versus conventional urine culture for diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 44, 113–124 (2022).

Xu, R., Deebel, N., Casals, R., Dutta, R. & Mirzazadeh, M. A new gold rush: a review of current and developing diagnostic tools for urinary tract infections. Diagnostics 11, 479 (2021).

Antic, T. & DeMay, R. M. The fascinating history of urine examination. J. Am. Soc. Cytopathol. 3, 103–107 (2014).

Iorio, L. & Avagliano, F. Observations on the Liber medicine orinalibus by Hermogenes. Am. J. Nephrol. 19, 185–188 (1999).

Yildirim, M., Bingol, H., Cengil, E., Aslan, S. & Baykara, M. Automatic classification of particles in the urine sediment test with the developed artificial intelligence-based hybrid model. Diagnostics 13, 1299 (2023).

Cho, S. Y. & Hur, M. Advances in automated urinalysis systems, flow cytometry and digitized microscopy. Ann. Lab. Med. 39, 1–2 (2018).

Wald, C. Diagnostics: a flow of information. Nature 551, S48–S50 (2017).

Simerville, J. A., Maxted, W. C. & Pahira, J. J. Urinalysis: a comprehensive review. Am. Fam. physician 71, 1153–1162 (2005).

Mascini, M. & Tombelli, S. Biosensors for biomarkers in medical diagnostics. Biomarkers 13, 637–657 (2008).

Yigci, D., Ergönül, Ö & Tasoglu, S. Mpox diagnosis at POC. Trends Biotechnol. 43, 2427–2439 (2025).

Il’yasova, D., Scarbrough, P. & Spasojevic, I. Urinary biomarkers of oxidative status. Clin. Chim. Acta 413, 1446–1453 (2012).

Varghese, S. A. et al. Urine biomarkers predict the cause of glomerular disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 18, 913 (2007).

Sands, B. E. Biomarkers of inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 149, 1275–1285.e1272 (2015).

Sarabi, M. R. et al. Disposable paper-based microfluidics for fertility testing. IScience 25, 104986 (2022).

Yeasmin, S. et al. Current trends and challenges in point-of-care urinalysis of biomarkers in trace amounts. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 157, 116786 (2022).

Oyaert, M. & Delanghe, J. R. Semiquantitative, fully automated urine test strip analysis. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 33, e22870 (2019).

Vuljanić, D. et al. Analytical verification of 12 most commonly used urine dipsticks in Croatia: comparability, repeatability and accuracy. Biochem. Med. 29, 123–132 (2019).

Ryan, D., Robards, K., Prenzler, P. D. & Kendall, M. Recent and potential developments in the analysis of urine: a review. Anal. Chim. Acta 684, 8–20 (2011).

von Münch, E. Basic overview of urine d components (waterless urinals, UD toilet bowls and pans, piping and storage). Sustainable Sanitation Alliance 4, 1–24 (2009).

Gleeson, M. J., CONNOLLY, J., GRAINGER, R., McDERMOTT, T. E. D. & BUTLER, M. R. Comparison of reagent strip (dipstick) and microscopic haematuria in urological out-patients. Br. J. Urol. 72, 594–596 (1993).

Mak, W. C., Beni, V. & Turner, A. P. Lateral-flow technology: from visual to instrumental. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 79, 297–305 (2016).

Guo-Qiang, W., Yu, Z., Bao-Kun, Q. & Jia-Yi, T. Solid phase extraction-silyl derivation-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry for the analysis of atrazine and its n-desalkalated metabolites in urine. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 37, 441–444 (2009).

Grayson, K., Gregory, E., Khan, G. & Guinn, B.-A. Urine biomarkers for the early detection of ovarian cancer – are we there yet?. Biomark. Cancer 11, 1179299X19830977 (2019).

Decramer, S. et al. Urine in clinical proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 7, 1850–1862 (2008).

Xylinas, E. et al. Urine markers for detection and surveillance of bladder cancer. Urol. Oncol. 32, 222–229 (2014).

Böhm, D. et al. Comparison of tear protein levels in breast cancer patients and healthy controls using a de novo proteomic approach. Oncol. Rep. 28, 429–438 (2012).

Gaikwad, N. W. et al. Urine biomarkers of risk in the molecular etiology of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Basic Clin.Res. 3, BCBCR. S2112 (2009).

Ploussard, G. & de la Taille, A. Urine biomarkers in prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 7, 101–109 (2010).

Swensen, A. C. et al. A comprehensive urine proteome database generated from patients with various renal conditions and prostate cancer. Front. Med. 8, 548212 (2021).

Barnes, L. et al. Smartphone-based pathogen diagnosis in urinary sepsis patients. EBioMedicine 36, 73–82 (2018).

Chen, W. et al. Application of smartphone-based spectroscopy to biosample analysis: a review. Biosens. Bioelectron. 172, 112788 (2021).

Jalal, U. M., Jin, G. J. & Shim, J. S. Paper–plastic hybrid microfluidic device for smartphone-based colorimetric analysis of urine. Anal. Chem. 89, 13160–13166 (2017).

Lewińska, I., Speichert, M., Granica, M. & Tymecki, Ł Colorimetric point-of-care paper-based sensors for urinary creatinine with smartphone readout. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 340, 129915 (2021).

Anthimopoulos, M., Gupta, S., Arampatzis, S. & Mougiakakou, S. in 2016 IEEE International Conference on Imaging Systems and Techniques (IST) 368–372 (IEEE, 2016).

Shaw, J. L. Practical challenges related to point of care testing. Pract. Lab. Med. 4, 22–29 (2016).

Snyder, S. R. et al. Effectiveness of barcoding for reducing patient specimen and laboratory testing identification errors: a Laboratory Medicine Best Practices systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Biochem. 45, 988–998 (2012).

Murphy, D. R., Satterly, T., Rogith, D., Sittig, D. F. & Singh, H. Barriers and facilitators impacting reliability of the electronic health record-facilitated total testing process. Int. J. Med. Inform. 127, 102–108 (2019).

Lewis, S. J. & Heaton, K. W. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 32, 920–924 (1997).

Blake, M., Raker, J. & Whelan, K. Validity and reliability of the Bristol Stool Form Scale in healthy adults and patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Alimentary Pharmacol. Ther. 44, 693–703 (2016).

Mínguez Pérez, M. & Benages Martínez, A. Escala de Bristol:¿un sistema útil para valorar la forma de las heces?. Rev. Enferm. Dig. 101, 305–311 (2009).

Kurahashi, M., Murao, K., Terada, T. & Tsukamoto, M. in 2017 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops (PerCom Workshops) 521–526 (IEEE, 2017).

Ku, W.-y., Conn, N., Borkholder, D. & Nwogu, I. in 2018 IEEE 9th International Conference on Biometrics Theory, Applications and Systems (BTAS) 1–7 (IEEE Press, 2018).

Antoury, L. et al. Analysis of extracellular mRNA in human urine reveals splice variant biomarkers of muscular dystrophies. Nat. Commun. 9, 3906 (2018).

Sinnott-Armstrong, N. et al. Genetics of 35 blood and urine biomarkers in the UK Biobank. Nat. Genet. 53, 185–194 (2021).

Aßmann, E. et al. Augmentation of wastewater-based epidemiology with machine learning to support global health surveillance. Nat. Water https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-025-00444-5 (2025).

Li, X. et al. Wastewater-based epidemiology predicts COVID-19-induced weekly new hospital admissions in over 150 USA counties. Nat. Commun. 14, 4548 (2023).

Vine, T., Carpenter, R. E. & Bridges, D. Diaper-based diagnostics: a novel non-invasive method for urine collection and molecular testing of uropathogens. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 113, 116939 (2025).

Yigci, D., Ahmadpour, A. & Tasoglu, S. AI-based metamaterial design for wearables. Adv. Sens. Res. 3, 2300109 (2024).

Russo, M. J. et al. Antifouling strategies for electrochemical biosensing: mechanisms and performance toward point of care based diagnostic applications. ACS Sens 6, 1482–1507 (2021).

Sunny, S. et al. Transparent antifouling material for improved operative field visibility in endoscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 11676–11681 (2016).

Lepowsky, E. & Tasoglu, S. Emerging anti-fouling methods: towards reusability of 3D-printed devices for biomedical applications. Micromachines 9, 196 (2018).

Celik, N. et al. Mechanochemical activation of silicone for large-scale fabrication of anti-biofouling liquid-like surfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 54060–54072 (2023).

Zhang, S., Zuo, P., Wang, Y., Onck, P. & Toonder, J. Anti-biofouling and self-cleaning surfaces featured with magnetic artificial cilia. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 12, 27726–27736 (2020).

Amin, R., Li, L. & Tasoglu, S. Assessing reusability of microfluidic devices: urinary protein uptake by PDMS-based channels after long-term cyclic use. Talanta 192, 455–462 (2019).

Leslie, D. C. et al. A bioinspired omniphobic surface coating on medical devices prevents thrombosis and biofouling. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 1134–1140 (2014).

Ferguson, B. S. et al. Real-time, aptamer-based tracking of circulating therapeutic agents in living animals. Sci. Transl. Med. 5, 213ra165 (2013).

Geng, H. & Cho, S. K. Antifouling digital microfluidics using lubricant infused porous film. Lab Chip 19, 2275–2283 (2019).

Hou, X., Hu, Y., Grinthal, A., Khan, M. & Aizenberg, J. Liquid-based gating mechanism with tunable multiphase selectivity and antifouling behaviour. Nature 519, 70–73 (2015).

Fdez-Sanromán, A. et al. Biosensor technologies for water quality: detection of emerging contaminants and pathogens. Biosensors 15, 189 (2025).

Cid, C. A., Stinchcombe, A., Ieropoulos, I. & Hoffmann, M. R. Urine microbial fuel cells in a semi-controlled environment for onsite urine pre-treatment and electricity production. J. Power Sources 400, 441–448 (2018).

Kirchmann, H. & Pettersson, S. Human urine-chemical composition and fertilizer use efficiency. Fertilizer Res. 40, 149–154 (1994).

Sinclair, R. G., Choi, C. Y., Riley, M. R. & Gerba, C. P. Pathogen surveillance through monitoring of sewer systems. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 65, 249 (2008).

Hou, C. et al. Estimating the prevalence of hypertension in 164 cities in China by wastewater-based epidemiology. J. Hazard. Mater. 443, 130147 (2023).

Daughton, C. G. Monitoring wastewater for assessing community health: sewage Chemical-Information Mining (SCIM). Sci. Total Environ. 619, 748–764 (2018).

Erickson, T. B. et al. “Waste not, want not”—leveraging sewer systems and wastewater-based epidemiology for drug use trends and pharmaceutical monitoring. J. Med. Toxicol. 17, 397–410 (2021).

Ort, C. et al. in New Psychoactive Substances 543–566 (Springer, 2018).

Mao, K. et al. The potential of wastewater-based epidemiology as surveillance and early warning of infectious disease outbreaks. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 17, 1–7 (2020).

Boogaerts, T. et al. Current and future perspectives for wastewater-based epidemiology as a monitoring tool for pharmaceutical use. Sci. Total Environ. 789, 148047 (2021).

Chen, C. et al. Towards finding a population biomarker for wastewater epidemiology studies. Sci. Total Environ. 487, 621–628 (2014).

Mittelstadt, B. Ethics of the health-related internet of things: a narrative review. Ethics Inf. Technol. 19, 157–175 (2017).

Martinez-Martin, N. et al. Ethical issues in using ambient intelligence in health-care settings. Lancet Digit. Health 3, e115–e123 (2021).

Ge, T. J., Chan, C. T., Lee, B. J., Liao, J. C. & Park, S. -m Smart toilets for monitoring COVID-19 surges: passive diagnostics and public health. npj Digit. Med. 5, 39 (2022).

Akkaş, T., Reshadsedghi, M., Şen, M., Kılıç, V. & Horzum, N. The role of artificial intelligence in advancing biosensor technology: past, present, and future perspectives. Adv. Mater. 37, 2504796 (2025).

Qureshi, R. et al. Artificial intelligence and biosensors in healthcare and its clinical relevance: a review. IEEE Access 11, 61600–61620 (2023).

Wasilewski, T., Kamysz, W. & Gębicki, J. AI-assisted detection of biomarkers by sensors and biosensors for early diagnosis and monitoring. Biosensors 14, 356 (2024).

Flynn, C. D. & Chang, D. Artificial intelligence in point-of-care biosensing: challenges and opportunities. Diagnostics 14, 1100 (2024).

Avci, D. et al. A new super resolution Faster R-CNN model based detection and classification of urine sediments. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 43, 58–68 (2023).

Nagai, T., Onodera, O. & Okuda, S. Deep learning classification of urinary sediment crystals with optimal parameter tuning. Sci. Rep. 12, 21178 (2022).

Suhail, K. & Brindha, D. Microscopic urinary particle detection by different YOLOv5 models with evolutionary genetic algorithm based hyperparameter optimization. Comput. Biol. Med. 169, 107895 (2024).

Lee, S. et al. Early-stage diagnosis of bladder cancer using surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy combined with machine learning algorithms in a rat model. Biosens. Bioelectron. 246, 115915 (2024).

Constantinou, M., Hadjigeorgiou, K., Abalde-Cela, S. & Andreou, C. Label-free sensing with metal nanostructure-based surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy for cancer diagnosis. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 5, 12276–12299 (2022).

Shin, H. et al. Single test-based diagnosis of multiple cancer types using Exosome-SERS-AI for early stage cancers. Nat. Commun. 14, 1644 (2023).

Sahu, A. et al. AI driven lab-on-chip cartridge for automated urinalysis. SLAS Technol. 29, 100137 (2024).

Bai, Q., Su, C., Tang, W. & Li, Y. Machine learning to predict end stage kidney disease in chronic kidney disease. Sci. Rep. 12, 8377 (2022).

Tsai, M.-H., Jhou, M.-J., Liu, T.-C., Fang, Y.-W. & Lu, C.-J. An integrated machine learning predictive scheme for longitudinal laboratory data to evaluate the factors determining renal function changes in patients with different chronic kidney disease stages. Front. Med. 10, 1155426 (2023).

De Bruyne, S., De Kesel, P. & Oyaert, M. Applications of artificial intelligence in urinalysis: is the future already here?. Clin. Chem. 69, 1348–1360 (2023).

Çelik, H., Caf, B. B., Geyik, C., Çebi, G. & Tayfun, M. Enhancing urinalysis with smartphone and AI: a comprehensive review of point-of-care urinalysis and nutritional advice. Chem. Pap. 78, 651–664 (2024).

Yang, Z., Cai, G., Zhao, J. & Feng, S. An optical POCT device for colorimetric detection of urine test strips based on Raspberry Pi imaging. Photonics 9, 784 (2022).

Flaucher, M. et al. Smartphone-based colorimetric analysis of urine test strips for at-home prenatal care. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 10, 1–9 (2022).

Acknowledgements

S.T. acknowledges Tubitak 1001 awards (123S582 and 123Z050) for financial support of this research. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the TÜBITAK. This work was partially supported by Science Academy’s Young Scientist Awards Program (BAGEP), Outstanding Young Scientists Awards (GEBIP), and Bilim Kahramanlari Dernegi the Young Scientist Award. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: S.T. Acquisition and synthesis of literature: D.Y., O.O., B.O., I.C., and B.K.T. Analysis and interpretation of evidence: D.Y., O.O., B.O., I.C., and B.K.T. Drafting of the manuscript: D.Y., O.O., B.O., I.C., and B.K.T. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: D.Y., A.K.Y., and S.T.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yigci, D., Ozarslan, O., Ozdalgic, B. et al. Smart sanitary hardware for health monitoring. npj Biosensing 3, 8 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00074-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00074-7