Abstract

This observational study explores the effect of adaptive cruise control (ACC) on energy in electric vehicles (EVs) and contrasts the findings with prior research on internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles. Using real-world driving data, we show that ACC engagement results in a penalty of +6.62 Wh/km, a 2.5% increase over the fleet-level average of 266 Wh/km. This penalty is smaller than that in ICE vehicles, primarily due to the superior efficiency of EV powertrains and the mitigating role of regenerative braking. On average, human drivers achieve higher regenerative braking efficiency than ACC. However, when braking conditions match, ACC marginally outperforms human drivers across most regions of the speed-deceleration map. This research provides insights into the interplay between energy-efficient technologies and driver-assistance systems, and highlights the need to optimize automation algorithms to leverage the unique characteristics of EV powertrains, maximize energy recovery, and support next-generation energy management solutions in transportation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adaptive cruise control (ACC) is an advanced driver-assistance system designed to enhance safety and convenience by maintaining a steady speed and a safe following distance from the vehicle ahead. By automating acceleration and braking functions, ACC reduces driver workload, particularly in long-distance trips or congested traffic scenarios. However, its impact on energy consumption has been a subject of debate, as its rigid speed control algorithms may not always align with optimal energy efficiency.

For most of automotive history, traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles have dominated the industry. However, the last decade has seen a shift to electric vehicles. This shift is driven by the higher efficiency of EVs and their zero tailpipe emissions, which contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and reliance on fossil fuels, aligning with global environmental objectives. Despite the growing adoption of EVs, there remains a gap in understanding the impact of advanced driver-assistance systems, such as ACC, on their energy consumption in the real world.

This study aims to fill this knowledge gap by examining the effect of ACC on the energy consumption of specifically electric vehicles and comparing the findings with existing research on ICE vehicles. A deeper understanding of this relationship can inform the development of more efficient ACC systems tailored to the specific needs of EVs, ultimately enhancing their driving range and alleviating customer range anxiety, one of the largest barriers to widespread EV adoption.

When comparing the results of EVs and ICE vehicles, it is essential to understand their differences. One significant advantage of EVs is their higher overall energy efficiency compared to ICE vehicles1. This is attributed to the electric motor’s ability to convert battery energy into kinetic energy more efficiently than the internal combustion engine, which loses a substantial amount of energy as heat. EVs not only achieve higher tank-to-wheel efficiency but can also benefit from the use of renewable energy sources, further enhancing their overall well-to-wheel efficiency compared to ICE vehicles2. The distinct differences of the two powertrains can also result in variations in driving styles between EVs and ICE vehicles, with a study finding that 73% of participants altered their driving style when transitioning to an EV3.

Although the previous Argonne study on ICE vehicles is informative4, there remains a notable gap in research concerning the real-world impact of ACC use on energy consumption in EVs, especially when comparing the two vehicle types. One study, however, does investigate the impact of ACC on energy consumption while comparing the effects by powertrain. Overall, the study found that ACC usage increased the energy consumption for both vehicle types: 1.43% for the EV and 2.26% for the ICE vehicle5. While this information is insightful, the study was constrained by a small dataset, spanning only one month of prescribed rural routes in a single city in Thailand.

While there are limited studies examining real-world ACC usage data, there is a wealth of research on improving ACC, such as implementing ecological adaptive cruise control (eco-ACC). For instance, one study proposed equipping vehicles with an extra sensor to collect upcoming trip data, such as an approaching hill, allowing the vehicle to accelerate before the incline, resulting in 15% energy savings6. Taking it a step further, another study developed a semi-autonomous eco-ACC system that adjusts vehicle speed based on road geometry, traffic signs, and the motion of preceding vehicles, achieving a 21% improvement in energy efficiency compared to human drivers7. In another, a learning-based eco-ACC system was able to demonstrate up to 14% efficiency improvements8. Many existing studies rely on simulation-based assessments, laboratory settings, or short road test models, which can be influenced by various factors, such as assumptions and equipment used. This highlights the need for more comprehensive real world data investigations9.

The presence of a battery and electric motor in EVs allows for the integration of regenerative braking systems, which can further increase EV energy efficiency10. Unlike conventional frictional braking, which converts kinetic energy into thermal energy, regenerative braking captures kinetic energy to recharge the battery, essentially operating as an alternator11. The inclusion of regenerative braking adds complexity to the influence of ACC systems on vehicle energy efficiency. One study found that tuning the ACC system to enhance regenerative braking efficiency could result in a 52% improvement in braking energy recovery12. Another study implemented a pulse-and-glide control strategy into the ACC system to improve vehicle energy efficiency with additional regenerative braking, achieving a 28% reduction in energy consumption when compared to traditional cruising behavior13. While numerous studies explore potential ACC methods for regenerative braking, there is a notable lack of research investigating the real-world impacts of ACC on regenerative braking efficiency. This gap highlights the need for more comprehensive studies using real-world data to fully understand and optimize the interaction between ACC and regenerative braking in EVs.

This study also builds on our group’s previous research into the energy implications of ACC in ICE vehicles and expands the analysis to EVs, addressing a critical gap in understanding how ACC influences energy consumption across different powertrain technologies.

In4, we investigated the impact of ACC on fuel consumption in ICE vehicles using a large-scale dataset of real-world driving behavior. A macroscopic trip-level analysis revealed that ACC engagement slightly increased fleet-level fuel consumption. However, a granular situation-based analysis highlighted potential benefits of ACC during specific maneuvers, such as acceleration and braking, where its precision offered improved energy efficiency compared to human drivers. This study underscored the importance of driving context in determining ACC’s overall energy impact.

In14 we explored the interaction between ACC and driver aggressiveness. We introduced a composite metric to classify drivers into calm, average, and aggressive profiles. The results showed that ACC amplified energy consumption penalties for calm drivers while moderating inefficient driving behaviors in aggressive drivers, leading to energy savings. These findings emphasized the role of driver behavior in shaping ACC’s impact and highlighted the potential for adaptive control strategies to tailor ACC performance to individual driving styles.

One unanswered question is whether ACC’s rigid speed control still leads to increased energy consumption in EVs, or if the unique characteristics of EVs (such as their ability to recover energy through regenerative braking) mitigate or even reverse these effects.

This paper aims to answer the following research question: How does ACC influence energy consumption in EVs, and how do the effects compare to ICE vehicles given the operational differences of EV powertrains? We will extend our understanding of ACC’s energy impact across vehicle technologies, provide insights for optimizing ACC systems for EVs, and ensure that their benefits align with the performance and sustainability goals of electrified transportation.

Methods

Data overview

This study focuses on a comprehensive dataset of real-world driving data collected in collaboration with General Motors (GM) under a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA). The dataset captures driving behavior across a diverse fleet of EVs equipped with Super Cruise or adaptive cruise control technology, providing a detailed foundation for analyzing the impact of ACC on EV energy consumption.

The dataset includes data collected from March 2024 through May 2024. It encompasses 10,828 trips taken by a fleet of 151 electric vehicles, covering a cumulative distance of 336,279 kilometers over 5092 hours of driving. ACC was engaged at some point in 36% of all trips, ensuring sufficient data to analyze its influence under various conditions. In Table 1, we compare these trip statistics with our previous research dataset of ICE vehicles from ref. 4. This EV-specific dataset introduces a wealth of detailed information tailored to the unique operational characteristics of electric powertrains. Signals include high-voltage battery usage, accessory loads, and regenerative braking performance, as well as standard driving behavior and vehicle performance metrics from powertrain, sensor, and ADAS data, plus GPS-based information augmented by HERE Maps API for added driving context.

Figure 1 provides an overview of trip characteristics for the EV dataset, offering insights into driving patterns and energy consumption. The trip distance distribution Fig. 1a shows that most trips are short, with a sharp peak below 20 km and an average trip distance of 31 km. This highlights that EVs are used predominantly for short commutes or urban travel, with a limited number of longer trips extending beyond 100 km. The trip electric consumption distribution Fig. 1b shows that most trips fall between approximately 15 and 50 kWh/100 km. The unweighted average consumption across all trips is 27.5 kWh/100 km, while the distance-weighted average (reflecting long-term efficiency) is slightly lower at 26.6 kWh/100 km. This small difference indicates that trips across the dataset are relatively balanced in length and consumption. The trip speed distribution Fig. 1c shows that speeds are concentrated between 20 and 100 km/h. The unweighted average trip speed is 49 km/h, while the time-weighted average speed (accounting for the duration of each trip) is 66 km/h. This overall distribution aligns with urban and suburban driving conditions, where moderate cruising speeds and stop-and-go traffic dominate. Such conditions are significant for evaluating ACC interaction with regenerative braking and energy recovery. Finally, the trip time distribution Fig. 1d indicates that most trips are short, with an average trip time of 28 minutes and a significant skew toward trips under 50 minutes.

This figure presents summary distributions of key driving metrics across electric vehicle trips. a Trip distance distribution shows a strong skew toward short trips, with most under 20 kilometers and an average of 31 km. b Trip electric consumption distribution shows most trips fall between 15 and 50 kWh/100 km, with a fleet average of 27.5 kWh/100 km. c Trip speed distribution shows average speeds centered around 49 km/h (unweighted), and 66 km/h when time-weighted. d Trip time distribution indicates most trips last under 50 minutes, with an average of 28 minutes. Blue bars represent trip percentage count histograms; red lines represent cumulative trip percentages. km kilometers, kWh kilowatt-hours, km/h kilometers per hour, min minutes.

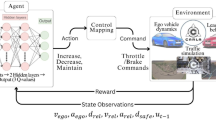

The data collection is managed by GM, while Argonne National Laboratory oversees data processing, quality assurance, and analysis. A robust framework has been developed for data ingestion, processing, and quality control, ensuring reliability and consistency. As shown in Fig. 2, this includes (1) map-matching the trips via HERE Maps API to enhance the dataset with road and route context and enable scenario-based analyses, (2) vehicle identification number (VIN) decoding to extract vehicle model and trim-level details to support vehicle-specific insights, leveraging Argonne’s internal Autonomie Vehicle Information Database of vehicle specifications15, and (3) driving situation segmentation to distinguish the different driving maneuvers and allow a more granular analysis16.

This high-level workflow illustrates the transformation of raw vehicle and sensor data into an analysis-ready dataset used in the study. The process begins with data ingestion and QA/QC, followed by data conversions and transformations. VIN decoding is performed to extract detailed vehicle specifications using Argonne’s internal Autonomie Vehicle Information Database (AuVID). Map-matching is conducted using HERE Maps API to provide route context and enable scenario-based analysis. Exploratory data analysis is conducted via internal dashboards, and the final structured data is stored for modeling and statistical analysis. This diagram is included to provide contextual understanding of the analytical framework and infrastructure supporting the study. QA/QC quality assurance and quality control, VIN vehicle identification number.

Dataset characteristics

The dataset comprises a diverse fleet of electric vehicles spanning multiple makes, models, and model years. Vehicles in the dataset include models from Cadillac, Chevrolet, GMC, BrightDrop, and Acura, primarily from the 2023 to 2025 model years (Fig. 3). Among the most represented vehicles are the Equinox EV and Silverado EV, contributing over 2000 trips each and covering the largest cumulative distances. Other notable entries include the Cadillac Escalade IQ, the GMC Sierra EV, and the Cadillac Lyriq, which cover substantial distances and contribute to the diversity of driving scenarios. The proportion of trips with ACC engagement varies widely across vehicle models but remains around 20% to 30% usage.

This figure presents the composition of electric vehicle makes, models, and years included in the dataset used for analysis. Each horizontal bar represents the number of unique vehicles per vehicle configuration. The bar chart highlights a wide range of vehicle types across various use cases and design generations.

This dataset includes a relatively heterogeneous fleet of EVs, and the composition highlights the importance of interpreting results in light of the specific characteristics and intended functions of these vehicles, as energy consumption patterns and ACC utilization are influenced by vehicle type, size, and technological features.

The geographic distribution of trips in the dataset spans a diverse range of locations across the United States. It reflects a fleet of vehicles driven by GM employees and therefore primarily corresponds to areas where GM facilities are located. As illustrated in the map in Fig. 4, a significant concentration of trips occurs in the Midwest, particularly around the major metropolitan area of southeast Michigan and Detroit, a well-known hub for GM operations. Additional clusters are observed along the West Coast, as well as in parts of Florida, particularly around Miami. A smaller number of trips occur in more remote areas, including parts of the Rocky Mountains and the deserts of Nevada and Utah.

This map highlights the regions where trips from the dataset were recorded, reflecting the locations of General Motors fleets. Clusters of trips are concentrated in the Midwest, particularly around Detroit and southeast Michigan, with additional high-density regions on the West Coast and in southern Florida. Scattered trip data points appear along interstate highways and cross-country routes, and illustrate a combination of local urban driving and long-distance travel. The background map shows state boundaries in gray, while red markers represent aggregated trip locations.

The coverage along major interstate highways and cross-country routes is also evident, with many trips appearing to connect major cities or traverse long distances. These represent travel on arterial highways or cross-regional logistics routes. This is complemented by local driving in suburban and urban environments, with a mix of short commutes and long-distance travel. The geographic spread ensures that the dataset captures a wide spectrum of driving conditions across different terrains, traffic patterns, and environmental contexts.

Analysis: addressing causal bias

As noted in our previous work, a central challenge in such observational studies is the difficulty of isolating the causal impact of ACC on energy consumption due to potential confounding factors. This arises because ACC engagement is not randomly assigned across trips. Drivers are more likely to engage ACC under specific conditions, such as highway driving or consistent traffic flow, which are inherently associated with lower energy consumption. Failing to control for these contextual factors could lead to biased estimates of ACC’s effect on energy consumption.

To address this, we employed a causal inference framework using a linear mixed-effects model. This model controls for trip-specific variables that influence energy consumption and isolates the effect of ACC engagement. Specifically, random effects are used to control for unobserved variability in driving behavior and vehicle characteristics across the dataset, capturing vehicle- and driver-specific differences. Fixed effects are included to account for systematic variations in energy consumption attributable to trip characteristics.

In our previous study4, we estimated the average treatment effect (ATE) of ACC engagement on energy consumption in this framework. The ATE, as shown in equation (1), is formally defined as the expected difference in energy consumption between trips where ACC is engaged (ACC = 1) and trips where it is not engaged (ACC = 0):

Where:

-

Y(1) represents the energy consumption for a trip where ACC is engaged.

-

Y(0) represents the energy consumption for the same trip if ACC had not been engaged.

For any given trip, we observe only Y(1) or Y(0), but never both. This lack of counterfactual observations prevents us from directly computing the individual treatment effect for a trip. To address this, we use statistical modeling to estimate the ATE while controlling for confounding variables. Specifically, we model the observed energy consumption Yij for trip i made by driver or vehicle j as a function of ACC engagement ACCij, fixed effects for trip-level covariates Xij, and random effects for unobserved variability across drivers or vehicles:

Where:

-

ACCij is the binary indicator of ACC engagement for trip i by driver or vehicle j.

-

β1 captures the causal effect of ACC engagement on energy consumption, adjusting for covariates.

-

f(Xij) represents fixed effects for trip-specific covariates, such as average speed, trip distance, elevation changes, etc.

-

\({u}_{j} \sim {\mathcal{N}}\left(0,{\sigma }_{u}^{2}\right)\) represents random effects for driver or vehicle j, accounting for unobserved variability in baseline energy consumption across individuals or vehicles.

-

\({\epsilon }_{ij} \sim {\mathcal{N}}\left(0,{\sigma }_{\epsilon }^{2}\right)\) is the residual error for trip i by driver or vehicle j.

In this framework, the ATE is estimated as the average effect of ACCij, represented by β1 in equation (2), across all trips. It represents the conditional average treatment effect, adjusting for the covariates included in f(Xij), and is therefore approximated by equation (3) as:

For a more detailed exposition of this modeling framework, we refer the reader to our original work4, where the method is developed and discussed extensively.

Analysis: controlled variables

To address potential confounding influences, we carefully selected and controlled for a set of key variables that capture trip, environmental, and vehicle-specific factors shown in Table 2. The controlled variables were chosen based on their known or hypothesized relationship with energy consumption. Energy consumption, the dependent variable, is calculated as total energy consumed divided by total distance and is represented in Wh/km to provide a standardized metric for comparison across trips. To ensure compatibility with the linear modeling framework used in this study, the selected variables have undergone specific transformations (indicated by an asterisk in Table 2) to preserve the linearity assumption. From our exploratory analysis of the data, we designed these transformations to capture non-linear relationships in a manner that aligns with the linear model structure.

Trip characteristics, such as vehicle speed, acceleration energy, and trip distance, are critical components in understanding energy consumption. Vehicle speed, modeled through both inverse average speed and maximum speed, reflects its non-linear influence on energy demand due to factors like aerodynamic drag and rolling resistance. Acceleration energy, measured as the total energy associated with acceleration events during a trip (see4), accounts for driving dynamics such as rapid starts and stops, which can significantly impact efficiency. Similarly, the inverse of total trip distance is included to capture variations in energy consumption between short and long trips, as shorter trips may exhibit disproportionately higher energy use due to auxiliary loads, temperature, and transient powertrain behavior.

Road and terrain characteristics also play a vital role in shaping energy consumption. Elevation difference, represented as the total elevation change during a trip, controls for the additional energy demands of uphill driving and the potential energy recovery provided by regenerative braking on downhill segments. Environmental conditions are equally important, with ambient temperature and high-voltage (HV) battery temperature included as covariates. To better capture the non-monotonic effect of ambient temperature on EV energy consumption, we replaced ambient temperature with the absolute deviation from a thermal-neutral reference point (22°C). Average ambient temperature is a well-established factor influencing battery performance and auxiliary loads, while the average HV battery temperature captures its impact on powertrain efficiency and regenerative braking functionality.

Driver behavior and system engagement variables are used to further refine the analysis. One-pedal engagement, categorized as on or off, reflects driver control strategies that directly affect regenerative braking and energy recovery. As the primary independent variable of interest, ACC engagement is included as a binary indicator to measure its effect on energy consumption, independent of these other factors. Finally, vehicle-specific characteristics are accounted for using vehicle type, represented by make, model, and trim level. This random effect captures inherent differences across vehicle designs, such as aerodynamics, weight, and powertrain efficiency.

Analysis: modeling details

Equations (4) and (5) specify the linear mixed-effect model for the study:

The random effects, αj (random intercept) and β1j (random slope for inverse average speed), are modeled as follows:

for j = 1, …, J.

The dependent variable, Energyi, represents the energy consumption for trip i, measured in Wh/km. The fixed effects include the following:

-

The term β1j[i] ⋅ inv_spdi captures the relationship between the energy consumption for trip i and the inverse of the average speed during that trip inv_spdi, with β1j[i] representing the effect size of this relationship for vehicle type j.

-

The term β2 ⋅ ACCON,i captures the effect of ACC engagement for trip i.

-

The term \({\beta }_{3}\cdot \max {\_}{\text{spd}}_{i}\) captures the effect of maximum speed during trip i.

-

The term β4 ⋅ inv_disti captures the effect of inverse of trip distance.

-

The term β5 ⋅ acc_nrgi captures the effect of acceleration energy for trip i.

-

The term β6 ⋅ elev_chgi captures the effect of total elevation change for trip i.

-

The term β7 ⋅ amb_temp_devi captures the deviation effect from mild ambient temperature (22°C) for trip i.

-

The term β8 ⋅ bat_tempi captures the effect of average battery temperature for trip i.

-

The term β9 ⋅ one_pedalON,i captures the effect of one-pedal driving engagement for trip i.

Our decision to include random slopes β1j[i] for inverse average speed recognizes that the relationship between speed and energy consumption is not uniform across all vehicle types. Different vehicle models have distinct design characteristics that influence how speed affects energy consumption. For example, vehicles with different aerodynamic designs, weights, or control designs may experience different interactional energy effects with speed. Including random slopes enhances the model’s flexibility and fit by letting the data dictate how speed interacts with energy consumption for each vehicle type. This prevents systematic biases that might arise if the speed-energy relationship is incorrectly assumed to be constant across all vehicles.

For the purposes of this study, a binary indicator (β2 ⋅ ACCON,i) was used for ACC engagement. A trip is categorized as “ACC ON” if ACC was engaged at any meaningful point during the trip, and “ACC OFF” otherwise. We acknowledge that more granular modeling is possible, for example, using the proportion of ACC engagement as a continuous covariate. However, we intentionally chose the binary form because a binary indicator provides a clearer interpretation of effect size (the average difference in energy consumption in trips where ACC is used at some point, vs. the counterfactual case where it was not used at all).

Results

Main effects

In Table 3 we show the result of the linear mixed effect model, analyzing the effect of the selected variables on energy consumption, measured in Wh/km.

A few notes on the model fitting show a residual variance of 2080.5 Wh2/km2 and size to 30.6% of the total variance. The model has a good fit, explaining approximately 69.4% of the variability in energy consumption, consistent with the conditional R2 value of 0.704.

The results show significant effects on energy: First, ACC engagement clearly increases energy consumption, with an estimated effect of 6.62 ± 1.74 Wh/km (p < 0.001). In the next section, we discuss in greater detail the interpretation of this specific result. The inverse of average speed has a positive coefficient (14.80 ± 3.71, p < 0.001), indicating that slower average speeds are associated with increased energy consumption. This result aligns with expectations that low-speed conditions, such as urban stop-and-go traffic, often lead to higher energy demands due to frequent acceleration. Maximum speed also has a positive effect (1.11 ± 0.043, p < 0.001), reflecting the well-documented impact of aerodynamic drag at higher speeds. The inverse of trip distance, 108.4 ± 7.40, p < 0.001, strongly influences energy consumption, indicating that shorter trips are associated with disproportionately higher energy consumption per kilometer. This can be attributed to higher relative auxiliary loads, cold start penalties, and transient powertrain inefficiencies during shorter trips. The trip-level energy associated with acceleration (27.03 ± 3.24, p < 0.001) also increases energy consumption, consistent with the additional energy demands of frequent or aggressive acceleration. Elevation change, 0.14 ± 0.0076, p < 0.001 has a positive effect, as expected, reflecting the increased energy required for uphill driving. Ambient temperature has a positive coefficient (3.72 ± 0.14, p < 0.001), indicating increased energy consumption as ambient conditions deviate from 22 °C. One-pedal driving has a negative coefficient (−6.75 ± 1.49, p < 0.001), which suggests reduced energy consumption with enhanced use of regenerative braking. Battery temperature strongly correlates with ambient temperature and is not statistically significant (−0.10 ± 0.11, p = 0.368).

The inclusion of random effects for vehicle type accounts for heterogeneity in baseline energy consumption (αj) and the effect of inverse average speed (β1j). The variance in the random intercept (4401.8 Wh2/km2) and random slope (259.6 Wh2/km2) highlights the substantial variability between vehicle types.

ACC effect in EVs compared to ICE vehicles

Our findings revealed that ACC engagement in EVs leads to an average penalty of +6.62 Wh/km. To put this finding in context, we compared it to the average fleet-level energy consumption of 266 Wh/km (weighted) in EVs, as observed in Fig. 1b. This penalty represents a 2.5% increase in energy consumption attributable to ACC usage and highlights the energy cost associated with this driver assistance feature in EVs. This penalty is notably smaller in absolute terms than the +24.20 Wh/km penalty observed in ICE vehicles (+0.26 L/100 km, based on energy content of 120,214 Btu per gallon of gasoline) in our previous study4. However, the ACC-induced penalty in ICE vehicles corresponded to an approximately 2% increase in fuel consumption over the baseline fleet average.

The reduced absolute energy penalty for EVs reflects the dramatically lower energy requirements for an electric vehicle to complete an equivalent trip to an ICE vehicle, due to the inherently higher efficiency of electric powertrains — electric motors can achieve energy conversion efficiencies of up to 90%, whereas ICE powertrains typically operate at only 25–30% efficiency — and the role of regenerative braking in recovering energy during deceleration. However, given electric vehicles’ highly efficient baseline performance, ACC systems present a greater efficiency penalty for EVs (on a percentage basis) than for ICE vehicles. This underscores the need for ACC algorithms that prioritize reducing tractive energy while in cruise, since road load is the dominant contributor to overall energy loss in electric vehicles.

Regenerative braking overview

By comparing ACC-engaged scenarios with human-driven scenarios, this section evaluates the role of ACC in influencing regenerative braking efficiency and compare how efficiently regenerative braking captures and stores energy during deceleration events.

Regenerative braking event identification

Regenerative braking efficiency η was analyzed by examining individual “regen events,” defined as instances in which the vehicle decelerates and recovers energy. These events were characterized by the following criteria:

-

Current is flowing into the high-voltage battery (at least 15A).

-

The vehicle speed drops by more than 10 km/h.

-

Events last between 5 and 30 seconds.

Events less than 5 seconds were excluded as the noise introduced by uncontrolled factors (e.g., accessory loads) becomes significant in short-duration events where low amounts of overall energy are recovered. Events greater than 30 seconds are excluded because they tend to represent uncommon driving conditions like sustained downhill driving (e.g., mountain passes). Regenerative braking efficiency is defined in equation (6) as the ratio of the actual electrical energy delivered to the HV battery to the total tractive energy theoretically available from the vehicle’s motion.

Here ΔEbatt is the amount of electrical energy transferred into the HV battery during the regen event and ΔEtract is the change in the vehicle’s total tractive energy, computed as the sum of its kinetic and potential energy at the beginning and end of the regen event.

The electrical energy delivered to the HV battery is computed in Eq. (7) as the discrete sum of the product of voltage (Vj), current (Ij), and time interval (Δtj) across all time steps (N) within the regen event:

The energy available for recovery is calculated in Eq. (9) as the difference between the tractive energy at the end (Ef) and the beginning (Eo) of the regen event. The tractive energy at any given point is, as shown in Eq. (8), the sum of the vehicle’s kinetic and potential energy:

Therefore, the tractive energy difference is:

Where:

-

m is vehicle mass (nominal for each VIN).

-

g is gravitational acceleration.

-

ho, Δh: are initial elevation and elevation change during the regen event.

-

vo, vf: Initial and final vehicle speeds during the event.

Note that the road load losses are not explicitly included in the calculation. Any additional road load losses incurred as a result of behavioral choices during a regen event (i.e., the chosen deceleration profile) will reduce the theoretically recoverable energy and apply downward pressure on efficiency values. Accessory loads are also not considered in the efficiency calculation; however, these tend to be negligible in magnitude compared to the recoverable power in a regenerative braking maneuver. The vehicle mass used in the calculations is assumed to be constant and representative for each VIN.

Regen efficiency: comparing direct distributions

Figure 5 shows a comparison of the direct distributions of regenerative braking efficiency. We note that events with ACC OFF exhibit higher efficiency levels on average compared to events with ACC ON. Specifically, the mean regenerative braking efficiency for ACC OFF events is 69%, while for ACC ON events, it is 62%. This represents a noticeable reduction in energy recovery efficiency when ACC is engaged. A small fraction of events exceed 100% efficiency. This anomaly occurs because the methodology assumes nominal vehicle mass, and variations in actual vehicle load (e.g., passengers or cargo) can lead to more energy being available for recovery than expected. Another small fraction of the regen events exhibits negative efficiency. Negative efficiency occurs when road load losses and accessory loads outweigh the energy theoretically available for recovery. In addition, small inaccuracies in elevation measurements can influence the calculated energy available for recovery.

This density plot compares regenerative braking efficiency across events where adaptive cruise control was engaged versus disengaged. The horizontal axis represents regenerative braking efficiency, expressed as a percentage of the total tractive energy recovered and stored in the high-voltage battery during deceleration events. The vertical axis indicates the probability density of efficiency values across all qualifying events. Events where ACC was OFF are shown in a purple curve, and those with ACC ON are shown in green. On average, ACC OFF events achieve higher regenerative braking efficiency (70.6%) compared to ACC ON events (62.6%). The broader distribution in the ACC ON mode suggests higher variability and lower consistency in energy recovery. A small number of events with values above 100% or below 0% appear due to minor modeling assumptions, such as nominal vehicle mass or elevation noise.

That being said, the density plot of regenerative braking efficiency shows a clear shift between the two distributions, with a sharper peak and narrower spread near the mean value in ACC OFF events, while observing a broader distribution, with reduced efficiency on average and greater variability in ACC ON events.

Regen efficiency: stratified analysis

To better understand the differences in regenerative braking efficiency between ACC ON and OFF modes, a stratified analysis was conducted. Regen events were categorized and “binned” according to two key factors: starting speed and delta speed (change in speed during braking).

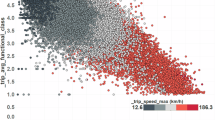

Figure 6 shows how the distribution of regenerative braking events differs markedly between the two modes. When ACC is OFF (human driver), events are more concentrated at lower starting speeds and have larger delta speeds. These conditions typically result in higher regenerative braking efficiency. When ACC is ON, events are clustered at higher starting speeds and smaller delta speeds. These events correspond to braking conditions where regenerative braking is less effective. Typically, high-efficiency regenerative braking occurs in scenarios with a low starting speed and a large deceleration (greater delta speeds), and human-induced braking events are more likely to fall within these high-efficiency zones, as indicated by the density contours in the efficiency heatmap. In contrast, ACC braking tends to operate more frequently in a zone with higher starting speeds and modest deceleration rates, where less energy is recoverable as more energy is lost to road load.

This figure compares regenerative braking events in electric vehicles under the two driving modes. The horizontal axis represents the starting speed of a braking event in kilometers per hour (kph), while the vertical axis shows the magnitude of the speed reduction during the event. Colored contours indicate the density of braking events for each mode: ACC OFF events are concentrated at lower starting speeds and larger speed reductions, while ACC ON events cluster at higher starting speeds and smaller reductions. The background color map shows the mean regenerative braking efficiency (%) for each region of the speed-deceleration space, with warmer colors indicating higher energy recovery.

This stratified analysis reveals that the unequal distribution of braking events is the root cause of the efficiency gap observed in the direct comparison of ACC ON and OFF modes. Because these circumstances heavily influence energy recovery potential, a fair comparison must account for differences in starting speed and delta speed. The subsequent section addresses this by focusing on regenerative braking events that occur under similar conditions.

Comparing equal Regen events

To ensure a fair comparison between ACC and human driver regenerative braking efficiency, events in the starting speed and delta speed bins were matched.

When regenerative braking efficiency was compared within each bin, ACC consistently outperformed human drivers in nearly every region of the map. To remove bias introduced by differences in braking scenarios, the comparison was stratified by 2D speed bins, such as a deceleration of 10-20 km/h from an initial speed of 100-110 km/h. This fine-grained binning ensures that events being compared are contextually similar. The efficiency difference contour plot (Fig. 7) shows regions where ACC braking achieves higher (red areas) or lower (blue areas) efficiency compared to human braking, where red zones appear to dominate the map and highlight an ACC advantage. Blue zones are sparse and indicate limited regions where human drivers perform better. In certain areas of the map, particularly those representing extreme braking scenarios (e.g., high starting speeds or large delta speeds), ACC events are underrepresented. These regions call attention to the need for more data to fully evaluate ACC performance under all possible braking conditions.

This figure shows the difference in regenerative braking efficiency between events where adaptive cruise control was engaged and disengaged. The horizontal axis shows the starting speed in kilometers per hour (kph), and the vertical axis shows the change in speed during the braking event. The color map displays the mean difference in efficiency between ACC ON and OFF, with red areas indicating higher efficiency under ACC, and blue areas indicating higher efficiency under human driving. Efficiency differences are clipped at ± 30 percent to improve contrast and visibility of intermediate trends.

The results indicate that, when braking conditions are comparable, ACC can marginally outperform human drivers in regenerative braking efficiency. This finding contrasts with the direct and stratified analyses, where humans exhibited an edge due to differences in braking context. However, the analysis shows the need for additional data in regions with sparse event representation. This sparsity arises because slicing the data over multiple factors, such as starting speed and delta speed, results in small sample sizes in each bin. Consequently, some of the observed differences might be due to noise rather than consistent patterns. To address this, in the next section, we employ statistical testing to confirm the findings and ensure that the comparisons account for the limitations posed by sparse data in certain areas of the dataset.

Statistical testing by region

A series of independent two-sample t-tests was conducted to evaluate whether the differences in efficiency are meaningful or due to random variation. The t-test assumes that the two samples are independent and compares their means while accounting for variability within each group. In cases where the t-test was not feasible due to non-normality or small sample sizes, a non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was used instead. This approach ensures that the analysis remains robust even in bins with fewer data points or non-normal distributions.

Each 2D region (defined by a specific range of starting speeds and speed decreases) was analyzed to compute the difference in regenerative braking efficiency between ACC ON and OFF events. The statistical tests provide a p-value for each region and quantify the likelihood that the observed differences occurred by chance. To account for multiple comparisons, a conservative Bonferroni correction was applied, as the probability of obtaining at least one false positive (Type I error) increases when performing numerous tests.

The bar charts in Fig. 8 summarize the results of statistical testing across different starting speed ranges (represented by the color bar) and delta speed ranges. Opaque bars indicate regions where the p-value after Bonferroni correction is below the adjusted significance threshold, and represent regions with statistically significant differences in regenerative braking efficiency between ACC ON and OFF modes. Particularly, we note that at medium starting speeds (60–100 km/h), ACC exhibits a statistically significant advantage over human drivers. Certain regions of the 2D map have limited data points for one or both modes. These regions are represented by light, semi-transparent bars with high p-values, indicating that comparisons in these bins lack statistical power. Sparse data limits the ability to draw definitive conclusions in these areas. For example, it is clear that at low city speeds, the data is sparse, and the size of the efficiency gap seems to be modest compared to the noise. The low use of ACC in this speed range makes comparisons and findings inconclusive.

This multi-panel figure presents the difference in regenerative braking efficiency between adaptive cruise control and human driving across three starting speed ranges: a city speeds (20-60 kph), b medium speeds (60–100 kph), and c highway speeds (100–140 kph). Each panel shows bar plots across bins of speed decrease (horizontal axis, in kph). The vertical axis represents the difference in regenerative braking efficiency (ACC minus human), in percentage points. Opaque bars represent bins where the difference is statistically significant after Bonferroni correction (adjusted p-value). Semi-transparent bars indicate regions where differences were not statistically significant. Missing bars reflect bins with insufficient data for comparison. Abbreviations: kph = kilometers per hour, p-value = probability value from hypothesis testing.

In some bins, no bars are present. This indicates regions where no valid comparison could be made due to insufficient data points for either ACC ON or ACC OFF modes. These areas are typically located in extreme braking scenarios (e.g., very high starting speeds combined with large or small deceleration) or rare driving conditions. The absence of bars highlights the need for additional data collection to ensure more comprehensive coverage of all driving scenarios. Data collection for this study remains ongoing, and as more data is gathered, this analysis will be refined in future iterations.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that current automated driving systems are not optimized to take full advantage of the unique characteristics of electric vehicles. That is, because exposure to road loads dominates the trip-level efficiencies observed in this study, future automated driving systems in EVs should strive to minimize exposure to road loads while still meeting the needs (e.g., desired arrival time) of the driver. Furthermore, there is urgency in addressing this efficiency shortfall because of two major ongoing trends — the rise in EV popularity globally, and the increasing prevalence of automated driving systems in new vehicles.

In the next decade, investments in EV infrastructure, advancements in EV technology, and ICE vehicle bans are expected to substantially increase EV penetration. In parallel, autonomous vehicle fleets (which are 100% electric and have greater utilization rates than light-duty consumer vehicles) are expected to expand their global footprint. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the global EV stock could reach 390 million vehicles by 203517.

In parallel, market studies show that the share of vehicles equipped with advanced driver-assistance systems (ADASs) is rising rapidly. A McKinsey study18 projects that the share of vehicles equipped with at least Level 2 ADASs will rise from just 9% of new cars in 2019 to 64% of vehicles in 2030.

When these trends are considered together, a 2% energy penalty incurred during automated driving in a rapidly rising number of ADAS-equipped EVs becomes a difficult figure to ignore. Using the rates of automated driving usage observed in this study (which are only expected to rise as systems improve), the fleet average energy consumption of vehicles in this study, and the IEA projection for global EV stock in 2035, that 2% energy penalty equals 15.4 TWh annually, approximately the entire annual energy consumption of Croatia19. The recommendations in this section have the potential to not only erase this current efficiency penalty but also achieve energy savings over the human driver baseline across this huge vehicle population.

To determine the most effective methods to improve efficiency in EV automated driving systems, it is imperative to first understand where energy is lost on its way from the energy source (battery) to the road. Powertrain efficiency in electric vehicles differs vastly from that in ICE vehicles. There are no sharp discontinuities (e.g., from different gears or engine operating modes in ICE vehicles), because most EVs use single-speed drivetrains, and because tractive motor efficiency varies relatively little as torque output changes. In some cases, EV efficiency can even improve as torque output increases. With dramatically higher and relatively invariant powertrain efficiencies compared to ICE vehicles, EV efficiency (particularly in highway cruising) is dominated by vehicle road load losses. This is best illustrated by an example.

Assume that an ICE pickup truck has 28% engine thermal efficiency, 90% transmission efficiency, and 93% driveline efficiency. Its road load is 30 hp at 70 mph, so the truck must produce 30 hp at the road to maintain speed. To overcome the efficiency losses from its source energy to the road, the truck must extract 30/0.93/0.9/0.28 = 128 hp from the energy source (fuel). In this case, the road load (30 hp) accounts for just 23.4% of the source power requirement to maintain the vehicle’s speed in highway cruising.

By contrast, an electric pickup with the same road load (30 hp at 70 mph) has dramatically different components between the energy source and the road. It may have a 97% inverter efficiency, a 95% tractive motor efficiency, and a 95% drivetrain efficiency with fewer parts than its ICE counterpart. By the same calculations, this means that only 30/0.97/0.95/0.95 = 34 hp needs to be extracted from the energy source. Therefore, the road load accounts for 88% of the power requirement to maintain the vehicle’s speed in highway cruising.

The net result is that decreasing an EV’s road load will have a disproportionately large benefit on its energy consumption, compared to increasing its powertrain efficiency. The most practical way to achieve a road load reduction is by lowering a vehicle’s cruising speed, but simply encouraging drivers to request lower set speeds is not an effective solution. Instead, we can take advantage of the fact that in many common driving scenarios, arrival time at a destination is determined not by the ego vehicle’s chosen speed, but by external factors such as traffic, stop lights and intersections. It is therefore possible to reduce cruising speed strategically while still minimizing travel time and pleasing the customer. Here, we recommend two distinct control strategies (one for highway driving, one for urban/suburban driving) to strategically limit vehicle speed in a manner imperceptible to the passengers.

As discussed above, the goal for an EV’s automated driving system in highway conditions is to limit the average traveling speed, without becoming objectionable (or ideally, even noticeable) to the customer. The easiest way to achieve opportunistic speed reductions is by maintaining approximately steady-state road load torque on inclines, mimicking how a human driver might hold a constant pedal position up a hill while allowing their speed to drop slightly.

The control strategy tested in ref. 20 maintains close to steady-state torque output during inclines, until the speed drops near the driver’s minimum acceptable threshold. Then, it increases torque output as needed to maintain, but not exceed, this lower threshold speed until the hill is passed. Tested back-to-back against conventional cruise control on a dynamometer over a moderate rolling terrain profile at 60 mph, “EcoCruise demonstrates a 3.3% improvement over standard cruise on the Bolt EV. At 70 mph, the benefit increases to 4.2% due to the increased road load reduction associated with dropping 1 mph at higher speeds.”20 In vehicles with higher road load than the relatively efficient Bolt EV, the percentage energy savings with this strategy is even greater. Unlike with ICE vehicles, over-speeds on declines are not permitted with this control strategy; instead, regenerative braking is used on declines to reduce the vehicle’s energy consumption while maintaining the driver’s original set speed.

In addition to the open-road control improvements discussed above, vehicles can react in anticipation of external factors like slowing traffic ahead. These scenarios can increasingly be detected by vehicles with Level 2+ automation equipped with cameras and long-range radars. In scenarios where external factors (like traffic) dictate maximum travel speed, passengers are more tolerant of speed reductions, so the automated driving system can slow down early, limiting road load losses and taking maximum advantage of regenerative braking opportunities.

In most urban and suburban scenarios, prevailing traffic speeds are determined largely by external factors (traffic density, stop lights, stop signs, intersections). Therefore, an optimized control strategy for these scenarios can be designed with these constraints in mind. For example, most urban driving involves accelerating from a full stop to a nominal flow speed, before having to stop again for traffic or infrastructure ahead. In addition, because much of the trip time is spent waiting for conditions ahead to change, drivers are relatively tolerant of their vehicle maintaining a variable gap to the vehicle ahead. This presents an extraordinary opportunity to shape accelerations, decelerations, and short “cruises” to minimize energy consumption.

The inventors of an optimized motor torque control algorithm for EVs21 use the algorithm to accelerate and decelerate using preprogrammed torque profiles that deviate minimally from the absolute minimum-energy path, given the physical characteristics of the drive motor. The study supporting this patent found that “the use of a low-energy torque profile may provide [2%–3%] energy savings on most accelerations.”21 This algorithm computes the minimum-energy profile for both accelerations and decelerations, given the final target speed and a time interval to reach that speed—two input parameters that would be calculated continuously by automated driving systems.

In fact, our current study provides supporting evidence for the stated opportunity to save energy by shaping the torque profile during acceleration events. One-pedal driving effectively shifts control of a vehicle’s deceleration from the driver to the vehicle’s control system, and our data shows that vehicles in one-pedal driving mode save an average of over 9 Wh/km compared to the purely human-driven baseline (this is larger than the negative effect associated with ACC). Furthermore, our statistical regenerative braking analysis shows that in bins where similar decelerations performed by human drivers and ACC are compared, ACC largely outperforms the human drivers in terms of energy efficiency.

Increasing levels of automation will enable automated driving systems to assume control in a greater number of scenarios, including more complex and dynamic urban environments. If these energy-saving control strategies are implemented from the start in these advanced automated systems, the small marginal energy savings across billions of acceleration and deceleration maneuvers will add up to substantial energy savings.

This work is one of the first in-depth investigations into automated driving systems’ impact on the efficiency of specifically electric vehicles, so there are still several areas that can benefit from additional study.

For example, more work can be done to identify the best methods and control strategies to strategically limit EV travel speeds in highly constrained environments (e.g., dense traffic). Ideally, such a study would list several strategies, each requiring a different level of equipment on board the vehicle (e.g., basic radars vs. real-time vehicle-to-infrastructure communication) and assess the potential energy savings of each. The most sophisticated strategies could then be applied to Level 4/5 automated vehicles, which have the most freedom in their operation and spend the most time in dense urban environments.

The potential energy benefits of vehicle-to-vehicle communication can also be explored in greater depth. If several vehicles in an area are all operating under the control of automated driving systems and have the ability to communicate with one another, they can choreograph their individual driving profiles to minimize wasteful reactions to surrounding vehicles and more effectively traverse the road as a group.

Most importantly, we feel this research should be extended by the vehicle manufacturers themselves, using the strategies proposed in this study. Even basic implementations of highway speed flexibility and energy-optimized acceleration and deceleration profiles for production of electric vehicles would extend customers’ EV range, improve the experience of automated driving systems, and theoretically reduce congestion in dense environments by limiting wasteful reactions between vehicles. Major advancements are being made to usher in a new era of personal transportation that is both electric and increasingly autonomous. In parallel, we would like to call upon the manufacturers to pay close attention to energy efficiency at the intersection of EV propulsion and automated driving.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy and confidentiality concerns. The dataset includes personally identifiable information (PII) in the form of GPS data, which traces the driving patterns of GM employees, including their commutes to and from home. As such, sharing the data publicly compromises the privacy of the individuals involved. Researchers interested in the dataset for collaborative projects or further analysis may contact the corresponding author to discuss potential data sharing under specific agreements that ensure the protection of privacy and confidentiality. Any data sharing would require approval and agreement from General Motors and would be contingent upon compliance with applicable privacy regulations and institutional guidelines.

Code availability

The analysis and visualization code used in this study were developed by the authors in Python (v3.10), R (v4.4.1), Matlab (v2024a), and Tableau software, using standard open-source libraries. Because parts of the dataset are derived from proprietary General Motors data under a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement, scripts referencing confidential data structures cannot be publicly released. All modeling parameters and variables used in the analysis are described in Table II and Equations (1–5).

References

Howey, D., Martinez-Botas, R., Cussons, B. & Lytton, L. Comparative measurements of the energy consumption of 51 electric, hybrid and internal combustion engine vehicles. Transp. Res. D: Transp. Environ. 16, 459–464 (2011).

Albatayneh, A., Assaf, M., Alterman, D. & Jaradat, M. Comparison of the overall energy efficiency for internal combustion engine vehicles and electric vehicles. Environ. Clim. Technol. 24, 669–680 (2020).

Rolim, C. C., Gonçalves, G. N., Farias, T. L. & Rodrigues, Ó. Impacts of electric vehicle adoption on driver behavior and environmental performance. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 54, 706–715 (2012).

Moawad, A. et al. Effect of adaptive cruise control on fuel consumption in real-world driving conditions. Nat. Commun. 15, 10016 (2024).

Achariyaviriya, W. et al. Comparative analysis of energy consumption in semi-autonomous vehicles: The influence of adaptive cruise control across various powertrains. AIP Conf. Proc. 3236, 080004 (2024).

Vajedi, M. & Azad, N. L. Ecological adaptive cruise controller for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles using nonlinear model predictive control. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 17, 113–122 (2016).

Sajadi-Alamdari, S. A., Voos, H. & Darouach, M. Ecological advanced driver assistance system for optimal energy management in electric vehicles. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 12, 92–109 (2020).

Kim, S. & Kim, K.-K. K. Learning-based ecological adaptive cruise control of autonomous electric vehicles: A comparison of ADP, DQN and DDPG approaches https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.01004 (2023). 2312.01004.

Noroozi, M. et al. An AI-assisted systematic literature review of the impact of vehicle automation on energy consumption. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 8, 3572–3592 (2023).

Huda, N., Kaleg, S., Hapid, A., Kurnia, M. R. & Budiman, A. C. The influence of the regenerative braking on the overall energy consumption of a converted electric vehicle. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 606 (2020).

Yang, C. et al. Regenerative braking system development and perspectives for electric vehicles: An overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 198, 114389 (2024).

Sun, C. et al. Research on adaptive cruise control strategy of pure electric vehicle with braking energy recovery. Adv. Mech. Eng. 9, 168781401773499 (2017).

Tian, Z., Liu, L. & Shi, W. A pulse-and-glide-driven adaptive cruise control system for electric vehicle. ArXiv abs/2205.08682 https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:238689487 (2021).

Moawad, A. et al. The double-edged sword of cruise control: Balancing fuel efficiency across driver profiles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. (2024). (Forthcoming).

Moawad, A. et al. Explainable AI for a no-teardown vehicle component cost estimation: A top-down approach. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2, 185–199 (2021).

Han, J. et al. Analyzing real-world driving data: Insights on trips, scenarios, and human driving behaviors. Accid. Anal. Prev. (2024). (Forthcoming).

Global EV Outlook 2024. Tech. Rep., International Energy Agency https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024/outlook-for-electric-mobility (2024).

Ondrej Burkacky, J. P. S., Johannes Deichmann. Automotive software and electronics 2030. Tech. Rep. McKinsey and Co., Inc. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/mapping-the-automotive-software-and-electronics-landscape-through-2030 (2023).

International electricity consumption dashboard. https://www.eia.gov/international/data/world/electricity/electricity-consumption.

Grewal, A. & Zebiak, M. Improving cruise control efficiency through speed flexibility & on-board data. SAE Int. https://doi.org/10.4271/2023-01-1606 (2023).

Zebiak, M. & Gessner, J. Electric motor torque control for electric vehicles. U.S. Patent and Trademark Office https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/df/d1/c4/dfdadc1c16a027/-US20240181896A1.pdf (2024). US20240181896A1.

Acknowledgements

The work described was sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Vehicle Technologies Office (VTO) under the Systems and Modeling for Accelerated Research in Transportation (SMART) Mobility Laboratory Consortium, an initiative of the Energy Efficient Mobility Systems (EEMS) Program. The following DOE Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) managers played important roles in establishing the project concept, advancing implementation, and providing ongoing guidance: Erin Boyd, Prasad Gupte, Alexis Zubrow, Jacob Ward, and David Anderson. Additionally, we would like to express our gratitude to Rock Putansu and Scott Simon, and the team at General Motors for their invaluable support and contributions, particularly in the areas of data collection and delivery. Their expertise and dedication were instrumental in the success of this project. The submitted manuscript was created by UChicago Argonne, LLC, Operator of Argonne National Laboratory (``Argonne''). Argonne, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, is operated under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. The U.S. Government retains for itself, and others acting on its behalf, a paid-up nonexclusive, irrevocable worldwide license in said article to reproduce, prepare derivative works, distribute copies to the public, and perform publicly and display publicly, by or on behalf of the Government. The Department of Energy will provide public access to these results of federally sponsored research in accordance with the DOE Public Access Plan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.K., A.R., and A.M conceptualized the study. A.M. developed the methodology and performed the formal analysis for ACC impact. M.Z. developed the methodology and performed the formal analysis for regen efficiency. M.Z., M.S.P., and A.M. conducted the investigation, while A.M curated the data. A.M., M.Z., and M.S.P. contributed to the analysis software. A.M. and M.Z. wrote the original draft, with all authors reviewing and editing the manuscript. A.M. and M.Z. handled the data visualization. D.K. and A.R. provided supervision and project administration. D.K. and A.R. also secured the funding for the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests but the following competing non-financial interest: this study was conducted under a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement between Argonne National Laboratory and General Motors. All authors were involved and had access to proprietary, confidential data provided by General Motors for analysis. No authors hold patents or patent applications related to the work reported in this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Moawad, A., Zebiak, M., Pierre, M.S. et al. Insights into adaptive cruise control and energy efficiency in electric vehicles. npj. Sustain. Mobil. Transp. 2, 49 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44333-025-00066-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44333-025-00066-0