Abstract

MicroRNAs are essential molecules that regulate many biological functions, including intestinal tight junction (TJ) barriers. They regulate pro-inflammatory cytokines, which increase TJ permeability, and anti-inflammatory cytokines, which protect against inflammation and promote intestinal balance. This review explores the role of miRNAs in controlling inflammation and as a potential therapeutic approach for treating IBD and other intestinal disorders. Circulating miRNAs can also serve as biomarkers for intestinal damage and disease progression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are single-stranded non-coding (16 to 24 nucleotides long) RNA molecules that act as post-transcriptional or translational regulators of gene expression by hybridizing to target mRNA 3′-untranslated regions (3’-UTR) and thereby regulating their translation1. It has been extrapolated from the existing data that more than one-third of human genes are expected to be regulated by miRNAs2,3. The synthesis of mature miRNAs with a ≈ 70 nucleotides stem-loop structure is complex, while capped miRNAs are exported to cytoplasm directly by exportin-1 (EXP-1) e.g., miR-320a-3p is transcribed to a primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) by RNA polymerase II and cropped by the RNase III-type enzyme Drosha to a pre-cursor miRNA (pre-miRNA; most miRNAs) except Mitrons (e.g., miR-877-5p) which are processed by spliceosome instead4. Exportin-5 (EXP-5) mediates the transfer of uncapped pre-miRNAs to the cytoplasm. Subsequently, the RNase III-type enzyme Dicer cleaves pre-miRNAs in the cytoplasm to produce mature and functional miRNA, which is then incorporated into the argonaut protein in the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). Dicer is required for the processing of miRNAs, hence conditional gene ablation has been used to inactivate this gene and explore the function of miRNAs in various organ systems5. Other miRNA-specific proteins involve terminal uridylyl transferase (TUTase; TUT7, TUT4), AGO2, TENT2, TRBP, and PARN6.

The structural and functional organization of the intestines consists of various cell types with distinct physiological properties and locations, such as enterocytes, Paneth cells, goblet cells, and neuroendocrine cells7. With increasing research in this area, it is clearer that miRNAs target and regulate major biological processes in the intestine and influence gene expressions multifariously in different cell types8. There are ~2600 known mammalian miRNAs with each miRNA influencing hundreds of gene transcripts9. Thus, the expression of different miRNAs and different sets of genes in each cell type in response to stimulation produces a complex symphony of functional shifts that is unique at the single-cell level and exhibits robust eukaryotic cell adaptability and genetic programming10. Several studies have shown that changes in intracellular miRNA expression profiles may correlate with various bowel diseases, including chronic inflammatory diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)11. There is also evidence that miRNA expression profiles differ between gut diseases with different etiologies12.

This review summarizes the current state of knowledge on the role of different miRNAs in intestinal diseases and highlights the functions of the most relevant miRNAs that play a specific role in regulating intestinal tight junctions (TJs). In addition, we discuss the emerging utility of miRNAs as potential diagnostic biomarkers in prognosis assessment/monitoring of gut diseases and promising aspects of heterogenous miRNAs in therapeutic interventions.

MicroRNA mechanism in the regulation of tight junction proteins

The intestinal epithelium is a highly organized and rapidly self-renewing tissue that forms a primary barrier separating our internal body compartments from an external environment, namely bacterial toxins, antigens from food, and other harmful substances in the intestinal lumen13,14. The epithelial barrier is an important non-immunological component of the intestinal barrier, characterized by the polarized distribution of organelles and membrane-bound proteins between their apical and basal surfaces15. The permeability of the intestinal epithelium is a highly regulated dynamic process. The extent of permeation of molecules can serve as a quantitative means of assessing the integrity of the mucosal barrier in health and disease16. Several factors play a role in regulating intestinal epithelium permeability. Our main interest is in epithelial TJ proteins, the most apical component of the epithelial intracellular junctions, which seal the paracellular space between cells and severely restrict the transport of intramembrane proteins, microbial lipids and peptides, and other harmful molecules such as bacterial endotoxins17. TJ consists of several functional proteins, which are either (i) integral transmembrane proteins that form a network between neighboring cell membranes with paracellular interaction, these include occludin, claudins, tricellulin, and junctional adhesion molecules (JAM), or (ii) cytoplasmic proteins, zonula occludens (ZO), and cingulin, which are cytoskeletal binding proteins that fasten integral membrane proteins and the actin cytoskeleton and are classified under control of signaling proteins18. This event is crucial in maintaining homeostasis and the intricate structure of the intestinal epithelium. When this barrier becomes more permeable, it can lead to the development of several gastrointestinal diseases, such as IBD, Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC), celiac disease, food allergies and Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) infection. The pathobiology of C. difficile infection also involves the modulation of TJ by its endotoxins. A small change in the structure of the TJ can prove to be harmful to the body due to an early inflammatory response. Despite the recognized importance of a defective intestinal TJ barrier or “leaky gut” in the development of intestinal inflammation associated with IBD and other inflammatory diseases, there are no approved therapeutic agents that can restore the TJ barrier19. Several studies have shown that strengthening the TJ intestinal barrier prevents the development of inflammatory bowel disease or leads to faster resolution of the inflammatory disease20,21,22,23,24,25,26. It is still not entirely apparent how intestinal permeability diseases compromise the TJ barrier integrity which is crucial from a therapeutic standpoint. It has been proposed that a deeper comprehension of the epigenetic mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of IBD may prove beneficial in the development of novel therapeutic strategies and improved diagnostic techniques for these conditions. Thus, miRNAs play a crucial role in regulating the function of the intestinal TJ by either increasing the expression of leaky gut inflammatory proteins or controlling protein synthesis through induced cleavage (translational inhibition)23,27. Since the miRNA transcriptome is involved in numerous molecular processes required for cellular homeostasis, any changes in its expression can trigger the development and progression of various intestinal pathologies. Notably, abnormal miRNA expression in IBD patients is associated with changes in intestinal permeability, visceral hyperalgesia, inflammatory pathways, and pain sensitivity28. Several relevant studies in recent years have shown that dysregulated miRNAs affect the TJ protein and a wide range of molecular mechanisms associated with IBD and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Therefore, molecules that enable targeted control of specific miRNAs in a specific context should improve the efficiency of existing treatments. However, the role of miRNAs in regulating epithelial TJ in the context of chronic gut inflammation priming and prognosis has not yet been sufficiently investigated.

NFκB, EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; MLCK, myosin light-chain kinase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; TNFR, tumor necrosis factor receptor; ZO-1, zonula occludens-1; Cingulin/Claudin. The Green background represents Higher cellular permeability associated with multiple pathologies. Sky blue background shows normal behavior and miRNAs with restorative/healing properties. Differentially expressed miRNAs (highlighted in yellow) are connected to the target via. Black arrow. A green circle with an arrow facing upwards represents miRNA upregulation or target overexpression/activation if shown at the beginning or the end of the arrow respectively. A red circle with an arrow facing downwards represents miRNA suppression or target suppression/de-activation if shown at the beginning or the end of the arrow respectively. Cross talks with Paneth cells, Mast cells and T cells are shown outside the intestinal epithelium (pink) doesn’t represent actual topology of the cells. This figure was drawn with the support of the bioicons website (https://bioicons.com/) using Inkscape software version 1.1.1 (3bf5ae0d25, 2021-09-20).

In our previous studies, we have shown that TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor α), a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine, causes a rapid increase in the expression of miR-122a in enterocytes and Caco-2 cells (human epithelial cells isolated from the colon of colorectal adenocarcinoma disease), as well as in the intestinal tissue of mice23. The overexpressed miR-122a in the enterocytes binds to a binding motif at the 3’-UTR of the occludin mRNA and induces its degradation, resulting in increased intestinal TJ permeability (Fig. 1). Interestingly, transfection of enterocytes with an antisense oligoribonucleotide against miR-122a blocked the TNF-α-induced increase in enterocytic expression of miR-122a, the degradation of occludin mRNA, and the increase in intestinal permeability. Also, overexpression of miR-122a in enterocytes using pre-miR-122a was sufficient to induce the degradation of occludin mRNA and an increase in intestinal permeability. Caveolin-1 (Cav1) and the caveolin-mediated transfer of occludin is an important regulation of TJ permeability25. Recently, miR-1258-x has been reported to regulate the expression of Cav1 and is under the control of the lncRNA Zeb129.

MicroRNA mechanisms in regulating the immune cascade that affects TJ proteins

We also investigated the effect of TNF-α on other transmembrane proteins, where it increased the expression of claudin-2 and claudin-8 but did not affect the expression of claudin-1, -3, or -5. These data suggest that the TNF-α-induced depletion of the occludin protein is specific to occludin and does not apply to other TJ proteins. Yujie Shen et al. in 2017 also reported that TNF-α did not alter the expression of the proteins claudin-1 and ZO-1 in the Caco-2 cells, but interestingly significantly interfered with TJ through the IL-8 (CXCL-8) signaling cascade, which reversed by increased or excessive expression of miR-200b by attenuation of the signaling pathways of JNK/c-Jun/AP-1 and myosin light chain kinase (MLCK)/phosphorylated myosin light chain (p-MLC)30 (Fig. 1). In our latest research, we examined the impact of proinflammatory cytokine IL1β-regulated microRNAs on intestinal permeability and TJ protein expression26. The miRNAs that may bind to the occludin 3′ UTR region were found to be miR-122, miR-200b-3p, and miR-200c-3p (Fig. 1). In Caco-2 cells, enterocytes, or intestines derived from animals exposed to IL1β (colitis), we were able to demonstrate that miR-200c-3p increased rapidly, increasing TJ permeability and lowering occludin protein and mRNA expression without changing the other transmembrane TJ proteins26. The AntagomiR-200c prevented the undesirable effect of IL1β on occludin mRNA and protein and decreased TJ permeability26. Interestingly, colon tissue and organoids from patients with UC had elevated levels of miR-200c-3p compared to healthy controls26. Through 3-dimensional molecular modeling and mutational analysis, we previously identified the nucleotide bases in the occluding mRNA 3ʹUTR that interact with miR-200c-3p26. Qiuke Hou et al. in 2018 showed that in the IBD rat model, 8 miRNAs were upregulated whereas 18 were downregulated31. They discovered that there was a considerable upregulation of miR-144, which resulted in the downregulation of ZO1 and OCLN expression, increasing intestinal hyperpermeability. The downregulation of miR-144 mitigated these negative effects and verified the direct target effect of miR-144 on OCLN and ZO1. Furthermore, rescue studies demonstrated that the inhibitory impact of miR-144 was offset by overexpressing OCLN and ZO1, indicating a larger effect on attenuating intestinal hyperpermeability31. Cristina Martínez et al. showed interest in identifying the participation of miRNAs in the differential expression of mRNA, which is correlated with ultrastructural abnormalities of the epithelial barrier function in patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS-D (irritable bowel syndrome)32. When compared to healthy controls, IBS-D samples displayed unique mRNA and miRNA (transcriptional and post-transcriptional) profiles. Seventy-five percent of the genes involved in the function of the epithelial barrier showed persistent overexpression upon further confirmation of a subset of genes. In silico mapping of putative miRNA binding sites miR-125b-5p and miR-16 suggested as expression regulators of the TJ genes cingulin and claudin-2, respectively. The protein expression of these TJ genes was upregulated in IBS-D, while the respective targeting miRNAs were downregulated32. Huiling Wang et al. showed significant downregulation of Claudin-8 in the colon of CD and UC patients, and TNBS-induced colitis33. Remarkably, TNBS colitis conditions and claudin-8 abundance were recovered by IL23 antibody treatment. miRNA prediction algorithms proposed that miR223 targets 3’-UTR Claudin-8 to elucidate the mechanism by which IL23 targets claudin-8. Claudin-8’s IL23 pathway is controlled more effectively by miR-223. Therefore, strategies to target this connection could offer novel treatment options for the treatment of IBD33. Different studies showed that miR-29 regulates intestinal permeability in patients with IBS-D (Fig. 1 and Table 1), where IBS-D increased levels of miR29a and b, but reduced levels of claudin-1 and nuclear factor-kB–repressing factor (NKRF)34. These results were identical with the induced colitis mouse model; however, these effects were significantly far fewer in the miR29−/− mice, in which expression of miR-29a and b, but not c, is lost. Using both TargetScan and 4-way PicTar, claudin-1 and NKRF genes were identified as functional integrity targets within the miR-29 family, and this was confirmed by dual-luciferase assay. Yuhua Zhu et al. studied neonates’ intestinal barrier function under intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) using a pig model, finding 83 upregulated and 76 downregulated miRNAs in the jejunum35. An overexpression/inhibition of miR-29a in IPEC-1 (intestinal epithelial cell line) can suppress/increase the expression of integrin-β1, collagen I, collagen IV, fibronectin, and claudin 1, both at transcriptional and translational levels35. A subsequent luciferase reporter assay confirmed a direct interaction between miR-29a and the 3’-UTR of these genes. In summary, IUGR impaired intestinal barrier function through the downregulation of ECM and TJ protein, which was regulated by miR-29a35. Other studies also showed an increased expression of miR-29a in IBS (IBS-D) models, which leads to a decreased level of glutamine synthetase gene (GLUL), and aquaporins (AQP1/3/8), ZO-1, and claudin-1 which results in increased intestinal membrane permeability36,37,38. Therefore, strategies to block miR-29 might be a new therapeutic approach to regulate the signaling mechanism of intestinal permeability, and for the treatment of IBS-D patients. Lindsay B. McKenna et al. linked the intestinal phenotype of Dicer1-mutants, mice lack functional miRNAs, to dysregulation of specific classes of mRNAs, where miRNAs affect protein translation3. Microarray analysis identified 3156 differentially expressed protein-coding genes in the jejunal mucosa of Dicer1 mutants, surprisingly, these genes were associated with immune pathways. Also, Dicer1-deficient mice showed disorganization in the intestinal barrier function with a decrease in goblet cells, a dramatic increase in apoptosis, and inflammation with lymphocyte and neutrophil infiltration. In addition, it was revealed that specific miRNAs play unique roles in different portions of the intestinal (jejunum to the large intestine) epithelium3.

MiRNA mechanism in intestinal inflammation following impaired intestinal permeability

An important function of IECs is to maintain the integrity of the mucosal barrier. TJs are pivotal in regulating intestinal permeability, transepithelial resistance, and the diffusion of macromolecules ( > 8-Å diameter) across the epithelial luminal surface39,40. Disruption of TJs increases bacterial or luminal antigen translocations, which overreact the mucosal immune response and chronic intestinal inflammation. Inflammation challenges the integrity of the mucosal barrier, and the intestinal epithelium needs to adapt to a multitude of signals to perform barrier function and maintain intestinal homeostasis41. IECs can show resolution against pathogens via an innate immune response and cytokines and chemokines signaling that link innate (e.g., macrophages, eosinophils, neutrophils, mast cells, etc.) and adaptive (lymphocytes; B cells and T cells) immune cell responses42. Together with an increased bacterial translocation or antigenic penetration, epithelial barrier failure and immune reaction can play a central role in intestinal inflammatory disease (Fig. 1). Central to this, several studies have reported an enhancement of the intestinal TJ barrier prevents the development of intestinal inflammation or leads to a more rapid resolution of the inflammatory disease. In parallel, studies showed that the production of different cytokines is responsible for the modulation or downregulation of different TJ proteins in the inflamed intestinal mucosa. Also, we know that the physiological imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines affects TJs. Pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL6, IL8, IL9, and IL-12 are the reason for increased TJ permeability and intestinal inflammation both in vitro and in vivo, while some anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10, IL-4, and TGF-β protect against the disruption mediated inflammation of the intestinal TJ barrier and advance of intestinal homeostasis43. Several studies showed these cytokines interact with their enterocyte receptors and induce intracellular signaling cascades resulting in the altered activity of various transcriptional factors (e.g., NF-κβ, STAT, FOS, and HIF1β) in the nucleus44,45. Among these cytokines, TNF-α plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of IBS. We and others demonstrated that the TNF-α significantly increases TJ permeability via activation of nuclear transcription factor (NF-κβ), which binds to the cis-κB binding site on the MLCK promoter region, and activates the MLCK gene transcription and protein synthesis process (Fig. 1). The phosphorylation of the regulatory light chain of myosin II by MLCK induces ring contraction and increases paracellular permeability43,46,47,48,49. Also, TJ permeability increases downstream of TNF-α involved activation of the ERK1 signaling pathway and not the p38 kinase pathway. ERK1/2 activates ELK-1 (ETS Like-1 protein, transcription activator), which leads to the activation of MLCK promoter activity and gene transcription50. In another study, we delineated the upstream signaling mechanisms that regulate the TNF-a modulation of intestinal TJ barrier function, where TNF-α activated NF-κB inducing kinase (NIK) and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase-1 (MEKK-1). NIK mediated the TNF-α activation of inhibitory κβ kinase (IKK)-α, and MEKK1 thereby activating the IKK complex, including IKK-β. NIK/IKK-α axis which regulated the activation of both NF-kβ p50/p65 and RelB/p52 pathways. Surprisingly, the siRNA-induced knockdown of NIK, but not MEKK-1, prevented the TNF-α activation of both NF-κβ p50/p65 and RelB/p52 and the increase in intestinal TJ permeability. Also, the NIK/IKK-α/ NF-κβ p50/p65 axis mediated the TNF-α-induced MLCK gene activation and the subsequent MLCK increase in intestinal TJ permeability. Thus, our data show that NIK/IKK-α/regulates the activation of NF-κβ p50/p65 and plays an integral role in the TNF-α-induced activation of the MLCK gene and increase in intestinal TJ permeability51. Christopher T. Capaldo et al. showed that IFN-γ/TNF-α treatment results in an increase in claudin 2 and a decrease in claudin 4, and depletion of claudin 4 by siRNA results in a striking increase in claudin 252. Thus, suggested that balanced claudin 2/4 protein expression is required to maintain TJ barrier function52. Min Cao et al., also showed that IFN-γ and TNF-α induced TJs disruption via the alteration of TJ proteins ZO-1, occludin, and claudin-1, which mediated through the signaling pathway of MLCK-dependent MLC phosphorylation arbitrated by HIF-1α and NF-κβ53 (Fig. 1). Our findings in addition to others provided novel insight into the cellular and molecular processes that regulate the TNF-α-induced increase in intestinal epithelial TJ permeability. Similar to TNF-α, IL-1β, a prototypical proinflammatory cytokine, significantly increased Caco-2 TJ permeability through NF-κβ. The use of NF-κβ inhibitors (pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate and curcumin) and siRNA-induced knockdown of NF-κβp65 completely prevented the action of IL-1β. IL-1β led to a decrease in occludin protein expression and an increase in claudin-1 expression but did not cause any change in the expression of the ZO-1 protein54. Our other studies suggested that the mechanism of IL-1β-induced increase in mouse intestinal permeability involved NF-κB-induced activation of the mouse enterocyte MLCK gene. We also showed that IL-1β did not cause an increase in intestinal permeability in MLCK-deficient mice (C57BL/6 MLCK−/−) and intestine tissue-specific siRNA transfection of NF-κB p6555,56,57. Correspondingly, several researchers demonstrated TNF-α/IL-1β-MLCK-NF-κBp65 signaling role in arbitrating intestinal inflammation and TJ proteins of either ZO-1, occludin, claudin-1, claudin-2, claudin-4, claudin-5 and JAM-A58,59,60,61. Nevertheless, under these circumstances, the contributions of occludin to barrier function have been questioned using occludin-deficiency models, in vitro and in vivo62,63,64. Contrarily, several studies demonstrated that occludin overexpression within the intestinal epithelium markedly attenuates TNF-α/IFN-γ-induced intestinal dysfunction65,66. Thus, targeting cytokines for homing cytokines-TJs cellular signaling plays a fundamental role in controlling intestinal inflammation and TJs permeability. Cytokine networks or altered changes in the cytokine production in immune cells, serum, and intestinal tissues of IBD patients are described elsewhere67,68,69. However, the functional relevance of the observed changes in terms of IBD prognosis and pathophysiology remained unclear. From this perspective, several attempts have been made to treat IBD patients using recombinant anti-inflammatory cytokines or antibodies specific to pro-inflammatory cytokines. The patient’s recovery or response with anti-inflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-α, IL-12/23, IL6, IL-23/Th17, IFNβ, IL-10, and IL-11) is unsatisfactory, and adjusting therapeutic dosages alone or in combinations while minimizing side effects is challenging70,71,72. Despite the advancement in understanding the disease, a specific microenvironmental offender triggering IBD complexities remains unknown. The latest research has discovered miRNA’s role in IBD disorders, where it post-transcriptionally regulates pro-inflammatory, apoptosis, cell proliferation, etc., which offers new insights into its pathogenesis (Fig. 2). As we detailed above, the imbalance of the inflammatory process primarily affects TJ functions and eventually increases intestinal leakage. Thus, using 3 different bioinformatics algorithms (MiRbase, UCSC, and PicTar), miRNA binding sites on 3′UTR of occludin mRNA were determined. The PicTar algorithm, which has the highest accuracy and sensitivity among the bioinformatics algorithms currently in use predicted three potential miRNA binding motifs on occludin 3′UTR: miR-122a, miR-200b, and miR-200c. The PicTar algorithm predicted with a very high likelihood (98% probability) that miR-122a had functional activity; miR-200b (86%) and miR-200c (91%) were predicted with lower probabilities. The TNF-α treatment induced miR-122a expression in a rapid manner. Conversely, TNF-α had only minimal effect on miR-200b and miR-200c expression suggesting a regulatory role of miR-122a in TJ permeability maintained by occludin23. We have previously assessed the role of miR-122a in a TNF-α-induced increase in Caco-2 TJ permeability through in-vitro transfection of miR-122a-M-ASO (2’-O-methyl-modified miR-122a antisense oligoribonucleotide). This resulted in an inhibition of TNF-α mediated miR-122a induction thereby normalizing inulin flux and preventing the TNF-α-induced decrease in occludin mRNA and protein expression. Pre-miR-122a co-transfection with occludin 3′UTR plasmid vector inhibited the luciferase (reporter gene) activity. The deletion of the miR-122a binding sequence on 3′UTR prevented the pre-miR-122a inhibition of luciferase activity, suggesting that miR-122a inhibits the luciferase activity by binding to its complementary sequence on 3′UTR. We have also transfected mouse intestinal mucosal surface using M-ASO directed against miR-122a. M-ASO transfection in vivo inhibited the TNF-α induced increase in miR-122a expression in mouse enterocytes and prevented the TNF-α induced increase in intestinal permeability. M-ASO transfection also protected enterocyte occludin mRNA expression levels against TNF-α induction. These results indicated that M-ASO inhibition of miR-122a expression inhibits the TNF-α induced increase in intestinal permeability23. In concurrence, as we explained in the above section, studies also showed that IL1β increases intestinal permeability24,26,54,55,57,73 and thus we have investigated microRNAs that are regulated by IL1β and their effects on the expression of TJ proteins. Targetscan server analysis helped to identify the miR-200c-3p target which was rapidly increased in Caco-2 cells incubated with IL1β; the antagomiR-200c prevented the IL1 β-induced decrease in occludin mRNA and protein and reduced TJ permeability 26. Thus, our study suggests that microRNAs that are regulated by pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α/ IL1 β) show deleterious effects on the expression of TJ proteins and intestinal permeability 26. Few other studies showed a fascinating function of miRNAs via regulating different molecules, which in due course affect intestinal TJs and homeostasis. Toshie Nata et al. showed differential expression of miRNAs in the IL-10 deficient large intestine mice74. Interestingly miR-146b improves intestinal inflammation by up-regulating NF-κB with decreased expression of SIAH2 (member of the seven in absentia homolog family), which ubiquitinates TRAF proteins. Thus, targeting miR-146b expression can act as therapy for intestinal inflammation via activation of the NF-κB pathway (Fig. 1)74. In situ hybridization analysis indicated that miR-192 expression significantly decreased in UC, and was predominantly localized to colonic epithelial cells. Macrophage inflammatory peptide (MIP)-2 alpha, a chemokine-induced by TNF-α in epithelial cells was associated with a reduction in miR-192 expression and was normalized by restoring miR-19275. Feng Wu et al. showed UC differential expressed 11 miRNAs; 3 were significantly decreased and 8 were significantly increased in UC tissues76. Also, described that intestinal tissues from patients with UC, and possibly other chronic inflammatory diseases, have altered miRNA expression patterns76. miR-193a-3p also has a positive effect by reducing mucosal inflammation of UC patients by targeting PepT1 which is a di/tripeptide transporter overexpressed in the small intestine and uptakes bacterial products. Downregulation of miR-193a-3p was associated with the upregulation of PepT1 in inflamed colon tissues of UC. While PepT1 activity has been shown to reduce nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein (MAP), PepT1 downregulation by overexpression of miR-193a-3p mediated reduction in inflammation suggests inversion of its function in case of dysbiosis associated with UC77. Christos Polytarchou et al. showed higher levels of miR-214 in colon tissues of UC or CAC patients compared to other disorders78. Here, it was shown that IL-6 up-regulates STAT3-mediated transcription of miR-214 in colon tissues, which reduces phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and PDZ and LIM domain 2 (PDLIM2), increases phosphorylation of AKT, and activates NF-κB. The activity of this circuit correlates with disease activity in patients with UC and progression to colorectal cancer (Fig. 3)78. Also, Lin Zhang et al. suggested that miR-21 may regulate intestinal epithelial TJ permeability through the PTEN/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, thus targeting miR-21 can preserve the intestinal barrier function79, later reported to be also involving Rho GTPase RhoB80. Few studies also confirmed significant upregulation of miR-155 in UC patients, where the expression of FOXO3a was decreased markedly. Luciferase reporter assays demonstrated that miR-155 directly targets FOXO3a and affects its translation in HT29 epithelial cells. Moreover, silenced FOXO3a and the overexpression of miR-155 increased the levels of IL-8 in TNF-α-treated cells by suppressing the inhibitory IκBα81,82. miR-155 has recently been reported to be susceptible to long noncoding RNA BFAL1-mediated sponging83. Recent studies point to claudin-7 as a direct TJ target of miR-155 in eosinophilic esophagitis84 and could be targeted by Kaempferol85.

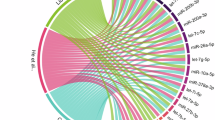

Different functions are represented as quadrants of a circular guide wheel. miRNAs are involved in the occurrence and development of DSS colitis like UC/Crohn’s disease. The majority of differentially expressed miRNAs regulate the generation, differentiation, and function of multiple immune cells (e.g., macrophages, DCs, T-cell) and associated fibroblasts, thus regulating inflammatory responses (Buff colored quadrant). miRNAs also affect the physical barrier of intestinal tract by regulating IEC’s tight junctions (Sky blue color quadrant). In addition, miRNAs can also govern healing or gut lining destruction through autophagy (purple quadrant) or cellular regeneration (turquoise color quadrant). A green circle with an arrow facing upwards represents miRNA upregulation or target function overexpression/activation if shown at the beginning or the end of the arrow respectively. A red circle with an arrow facing downwards represents miRNA suppression or target function suppression/de-activation if shown at the beginning or the end of the arrow respectively. This figure was drawn with the support of the bioicons website (https://bioicons.com/) using Inkscape software version 1.1.1 (3bf5ae0d25, 2021-09-20).

Different functions are represented as quadrant of a circular guide wheel. The majority of differentially expressed miRNAs regulate the generation, differentiation, and function of multiple immune cells (e.g., macrophages, DCs, T-cell) and associated fibroblasts, thus regulating inflammatory responses (Buff colored quadrant) which contribute to AOM-DSS component of CRC. Mi148/152 affects the physical barrier of intestinal tract around a polyp site by regulating IEC’s tight junctions (blue color quadrant). In addition, miRNAs can also govern CRC progression by promoting tumor growth by miR214 (purple quadrant) or Metastasis (green color quadrant). A green circle with an arrow facing upwards represents miRNA upregulation or target function overexpression/activation if shown at the beginning or the end of the arrow respectively. A red circle with an arrow facing downwards represents miRNA suppression or target function suppression/de-activation if shown at the beginning or the end of the arrow respectively. This figure was drawn with the support of the bioicons website (https://bioicons.com/) using Inkscape software version 1.1.1 (3bf5ae0d25, 2021-09-20).

Besides the disrupted epithelial barrier function, the hallmark of IBD is infiltrating immune cells. Several studies investigated the role of miR-146a in regulating intestinal immunity and barrier function. Using miR-146a−/− mice, demonstrated that miR-146a represses a subset of the gut barrier and inflammatory genes within a network of immune-related signaling pathways. It also found that miR-146a restricts the expansion of intestinal T cell populations, including Th17, Tregs, and Tfh cells. Similarly, the flavonoid compound Alpinetin from Alpinia Katsumadai Hayata seeds suppresses colitis by promoting Treg differentiation through AHR regulating miR-30286. Consistent with an enhanced intestinal barrier, miR-146a−/− mice were resistant to DSS-induced colitis, and this correlated with elevated colonic miR-146a expression in human UC patients87,88. MicroRNAs critically involved in inflammation and TJs disruptions are summarized in Table 2 and mapped in Fig. 2. In summary, although miRNA-mediated gene regulation is involved in several courses of IBD, the biological function of miRNAs in the pathogenesis of IBD has not been completely elucidated, especially as a potential anti-inflammatory agent where it improves epithelial TJ functions. Also, miRNA’s role in cellular crosstalk (e.g., immune cells and epithelial cells) perturbation in IBD has not been fully clarified. Thus, understanding different cellular functions in association with intestinal epithelium is vibrant. miR-135a is suppressed in IBD patients89. It was recently reported that miR-135a neutralization by ceRNA (competitive endogenous RNA) circSMAD disrupts barrier function by targeting Janus Kinase 290.

Extracellular microRNA’s role in intestinal barrier function

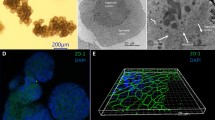

Exosomes (EXO) are small extracellular vesicles (EV; 30 to 100 nm) of endocytic origin and are released by a broad range of cell types that are found in most bodily fluids. Functional biomolecules, miRNAs, are believed to be transmitted between mammalian cells via exosomes that play important roles in cell-to-cell communication, both locally and systemically. While, EXO has been implicated in a wide variety of physio-pathological functions including barrier function, inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, immune response, and infection91. However, the clinical application of this knowledge requires further investigation. Shuji Mitsuhashi et al. investigated exosome contents aspirated from the intestinal luminal of an IBD patient, which contained significantly higher mRNA and proteins of IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α as compared to healthy control92. Also, the cultured colonic epithelial cells showed an enhanced translation of IL-8 protein when treated with EV from patients with IBD. Thus, it is suggested that EV content may reflect the transcriptional activity of their originator cells at inflammatory sites92. Hadi Valadi et al. described the exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs, where some of the miRNAs were expressed at higher levels in exosomes than in the cells, supporting EXO microRNAs cellular crosstalk functions93. Qichen Shen et al. discussed the modulatory functions of EV derived from various sources (e.g., IECs, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, mast cells) in the intestine, especially their effects and applications in IBD clinical therapy. It also describes the role of EV microRNAs in mediating interactions between intestinal and immune systems and their signaling mechanism for IBD pathogenesis and its cure94. Feihong Deng et al. demonstrated M2 macrophage-derived exosomal miR-590-3p reduces inflammatory signals and promotes epithelial regeneration by targeting LATS1 (Large tumor suppressor kinase 1) and subsequently activating YAP/β-catenin signaling in DSS-induced mucosal damage95 (Fig. 3). Triet M Bui et al. emphasized EV-associated miRNA’s role in regulating epithelial barrier function in inflamed intestines via resident and recruited immune cells96. Xiu Cai et al. described that human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell (hucMSC)-derived exosomes act as novel cell-free therapeutic agents for IBD. hucMSC-EXO-miR-378a-5p treatment inhibited NLRP3 (NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain-containing 3) inflammasomes and abrogated cell pyroptosis following DSS-induced colitis97. Also, Gaoying Wang et al. showed that hucMSC-exosomes carrying miR-326 inhibit neddylation to relieve IBD in mice98. Dong Sun et al. identified that exosomes derived from HO-1/BMMSCs (Heme Oxygen-1 modified bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells) play a vital role in alleviating the inflammatory injury of IECs. Here, exosomal miR-200b suppresses the abnormally increased expression of the HMGB3 gene in IECs99. Musheng Li et al. described mast cells (MCs) play a critical role in the development of IBD characterized by dysregulation of inflammation and impaired intestinal barrier function. The obtained results indicated that enrichment of exosomal miR-223 from MCs-1 inhibited CLDN8 expression, leading to the destruction of intestinal barrier function. These findings provided a novel insight into MCs as a new target for the treatment of IBD100. Kyriaki Bakirtzi et al. showed that SP/NK-1R (substance-P/neurokinin 1 receptor) signaling regulates exosome production in human colonic epithelial cells and colonic crypts and induces miR-21 cargo sorting101. EXO and miRNAs originate from both endogenous synthesis and dietary sources such as milk. Miao-Miao Guo et al. showed that human breast milk-derived exosome (BM-EXO) treatment exerts a significant protective effect on NEC (necrotizing enterocolitis) mice via miR-148a-3p/p53/SIRT1 axis by inhibiting inflammation and improving intercellular TJs. Here, miR-148a-3p directly targets p53 on its 3’-UTR, which significantly reduces p53 expression and upregulates sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) in the LPS milieu. In addition, decreased nuclear translocation of NF-κB and cell apoptosis were observed by the miR-148a-3p mimic102. On the other hand, miR-34a increased nuclear translocation of NF-κB and is the target of Krüppel-like factor (KLF) 4 mediated restoration of gut permeability in LPS/HFHC diet in vitro/in vivo models103. Mei-Ying Xie et al. showed that porcine milk EXO attenuated DON (deoxynivalenol)-induced damage to the intestinal epithelium. In vitro, EXO treatment upregulated the expression of miR-181a, miR-30c, miR-365-5p, and miR-769-3p in IPEC-J2 cells (porcine intestinal columnar epithelial cells) and then down-regulated their target genes via p53 pathway for promoting cell proliferation and TJs and by inhibiting cell apoptosis104. Xiu Cai et al. described that human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell (hucMSC)-derived exosomes act as novel cell-free therapeutic agents for IBD. hucMSC-EXO-miR-378a-5p treatment inhibited NLRP3 (NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain-containing 3) inflammasomes and abrogated cell pyroptosis following DSS-induced colitis97. Yi Chen et al. described that circulating exosomal microRNA-18a-5p accelerates Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis, and apoptosis by targeting RORA and inhibiting SIRT1/NFκB pathways105. Guoku Hu et al. reported that the luminal release of EXO is a critical component of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-associated gastrointestinal epithelial defense against infection by Cryptosporidium parvum, an obligate intracellular protozoan that infects gastrointestinal epithelial cells106. Extracellular miRNAs involved in intestinal homeostasis are summarized in Table 3.

MicroRNAs as a biomarker and intestinal disease diagnosis

IBDs have unknown etiology and are chronic gastrointestinal diseases with an autoimmune component. The patients in the IBD population are diverse and have different disease trajectories, necessitating individualized treatment plans. The diagnosis and the start of the right therapy are frequently delayed due to the disease’s intricacy. The gold standard for the diagnosis and evaluation of IBD (CD) is endoscopy/colonoscopy, although this is invasive, costly, and associated with risks to the patient107. The complexity of IBD involves multiple cell types, microbiomes, and endotoxins, and in addition to variability by disease site and associated conditions, limits the usage of conclusive biomarker panels. In recent years, circulating microRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as promising noninvasive biomarkers. Both tissue-derived and circulating microRNAs have emerged as promising biomarkers in the differential diagnosis and the prognosis of disease severity of IBD as well as predictive biomarkers in drug resistance. The paracrine signaling of differently expressed microRNAs warrants the interpretation of their biological significance as epigenetic regulators as they may contribute to an alternate repertoire of biomarkers108,109. Numerous reports suggest significant differential miRNA expression established in the very early phases of disease pathogenesis and is highly specific to the direction of the progression. Circulating miRNAs are being extensively studied as biomarkers of disease distinctly in cancer conditions, as their serum or tissue levels are altered in various pathological conditions107,108,109,110,111 (Fig. 3). Quite a few recent publications have described exosomes or exosomes-miRNA’s role in intestinal inflammation97,105,110,111,112,113,114,115,116. Geoffrey W. Krissansen et al. showed that miR-595 and miR-1246 were significantly upregulated in the sera of active colonic CD, and UC patients and are biomarkers of active IBD117. Also, reported that miR-595 impairs epithelial TJs, whereas miR-1246 indirectly activates the proinflammatory NF-κB of activated T cells117 (Fig. 2). miR-595 targets the cell adhesion molecule neural cell adhesion molecule-1 (NCAM1), and fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2), which plays a key role in the differentiation, protection, and repair of colonic epithelium, and maintenance of TJs. Thus, these miRNAs warrant testing as potential targets for therapeutic intervention in the treatment of IBD117. Peng Chen et al. recorded an increase in serum exosomal miR-144-3p levels in CD patients, which positively correlated with the simple endoscopic score of CDs as well as the Rutgeerts score. Also, exosomal miR-144-3p accurately identifies post-operative recurrence compared to C-reactive protein (CRP). Therefore, serum exosomal miR-144-3p can be a reliable biomarker of mucosal inflammation and CD118. Lina Sun et al. revealed that several aberrantly expressed miRNAs were reported in IBD, specifically miR-21, miR-16, and miR-192, and these showed to consistently up-regulated in the blood of patients with IBD, fulfilling a principal requirement as biomarkers for use in clinical practice119. Sarah Stiegler et al. described those intestinal cells at the gut epithelial barrier functions compromised because of dysregulated miRNA expression, which serve as biomarker panels and therapeutic strategies of gut permeability11. Adam M. Zahm et al. reported differential expression of miRNAs in serum samples of pediatric CD patients compared to pediatric celiac disease and healthy control. Thus, serum miRNA acts as a diagnostic potential107. Cristina Felli et al. discussed circulating miRNAs as powerful non-invasive biomarkers in the diagnosis of pediatric coeliac disease120. In parallel, studies also confirmed that Circular RNA (circRNA) had acted as ceRNA (competing endogenous RNA) for miRNA, thereby indirectly regulating downstream targets of disease121,122,123. Another study showed miR-197-3p had a protective role for Occludin expression and maintaining gut barrier in celiac disease duodenal biopsies124. Wei Ouyang et al. showed overexpression of circ_0001187 in UC patients, where its knockdown enhanced the proliferation while suppressing apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress of TNF-α. Effects of circ_0001187 were overturned by miR-1236-3p inhibitor, a target of MYD88. Therefore circ_0001187 facilitates UC progression by modulating the miR-1236-3p/MYD88 axis and therefore is a potential treatment target as well as a diagnosis biomarker for UC125. Also, studies showed that circ_0007919, and circAtp9b were upregulated in UC patients, and it might be a therapeutic target or biomarker for IBD126,127 (Fig. 2). The potential diagnostic and prognostic miRNA biomarkers are listed in Table 4 and Fig. 3. In recovering CD patients Circulating let-7e and miR-126 are shown to be markers for successful clinical remission128. The distinct composition of tissue-specific and circulatory miRNAs points to a multilevel regulatory machinery with separate autocrine and endocrine roles which may have overlapped. Given the complexity of miRNA networks influenced by a variety of factors, such as disease subtype and patient characteristics, the heterogeneity seen in miRNA expression patterns across studies highlights the necessity for standardized methodologies and protocols in miRNA research. Particularly, In conclusion, this knowledge should stimulate further studies to link circulating or EXO miRNAs to tissue or organ-specific disease pathogenesis and response to different therapies, which might be used as routine-powerful non-invasive biomarkers in the diagnosis, prognosis, or therapy response of IBD conditions.

Conclusions

The role of miRNAs in intestinal diseases and disorders is an area of rapidly growing interest. It is becoming increasingly clear that miRNAs can either speed up or slow down specific genes that regulate TJs, and their functions can vary depending on the cell type or tissue environment. While some effects of miRNAs on target genes are well understood, more research is needed to explore their cell-specific regulatory potential and how they are altered in disease conditions.

The biological importance of extracellular miRNAs, which may be especially significant in disorders like cancer and IBD, is another emerging field of research. Little is currently understood about how TJs or inflammatory factors are targeted by miRNAs associated with exosomes in disease or injury conditions. It is widely recognized that circulating miRNAs are more stable compared to many other biological markers, which has led to significant progress in identifying IBD- and cancer-specific miRNA biomarkers. However, understanding the role and changes in miRNAs in regulating TJs and cellular functions in different disease conditions provides a solid foundation for developing treatments that target miRNAs. It is reasonable to anticipate that within the next ten years, gastroenterologists will have access to miRNA-based therapeutics as a therapy option to treat tight junction aspects of various diseases.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Szabo, G. & Bala, S. MicroRNAs in liver disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10, 542–552 (2013).

Lewis, B. P., Burge, C. B. & Bartel, D. P. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 120, 15–20 (2005).

McKenna, L. B. et al. MicroRNAs control intestinal epithelial differentiation, architecture, and barrier function. Gastroenterology 139, 1654–1664, 1664.e1 (2010).

Kim, Y.-K., Kim, B. & Kim, V. N. Re-evaluation of the roles of DROSHA, Exportin 5, and DICER in microRNA biogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 113, E1881-9 (2016).

Yi, T., et al. eIF1A augments Ago2-mediated Dicer-independent miRNA biogenesis and RNA interference. Nat. Commun. 6, 7194 (2015).

Han, J. & Mendell, J. T. MicroRNA turnover: a tale of tailing, trimming, and targets. Trends Biochem. Sci. 48, 26–39 (2023).

Börner, K. et al. Anatomical structures, cell types and biomarkers of the Human Reference Atlas. Nat. Cell Biol. 23, 1117–1128 (2021).

Ruiz-Roso, M. B. et al. Intestinal lipid metabolism genes regulated by miRNAs. Front. Genet. 11, 707 (2020).

Plotnikova, O., Baranova, A. & Skoblov, M. Comprehensive analysis of human microRNA-mRNA interactome. Front Genet 10, 933 (2019).

Peck, B. C. E. et al. Functional transcriptomics in diverse intestinal epithelial cell types reveals robust MicroRNA sensitivity in intestinal stem cells to microbial status. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 2586–2600 (2017).

Stiegeler, S., Mercurio, K., Iancu, M. A. & Corr, S. C. The impact of MicroRNAs during inflammatory bowel disease: effects on the mucus layer and intercellular junctions for gut permeability. Cells 10, 3358 (2021).

Tarallo, S. et al. Stool microRNA profiles reflect different dietary and gut microbiome patterns in healthy individuals. Gut 71, 1302–1314 (2022).

Parigi, S. M., Eldh, M., Larssen, P., Gabrielsson, S. & Villablanca, E. J. Breast milk and solid food shaping intestinal immunity. Front. Immunol. 6, 415 (2015).

Gomez-Sanchez, J. A. et al. After nerve injury, lineage tracing shows that myelin and remak Schwann cells elongate extensively and branch to form repair Schwann cells, which shorten radically on remyelination. J. Neurosci. 37, 9086–9099 (2017).

Odenwald, M. A. & Turner, J. R. The intestinal epithelial barrier: a therapeutic target?. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14, 9–21 (2017).

Farhadi, A., Banan, A., Fields, J. & Keshavarzian, A. Intestinal barrier: an interface between health and disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18, 479–497 (2003).

Nighot, P. & Ma, T. Endocytosis of intestinal tight junction proteins: in time and space. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 27, 283–290 (2021).

Heiskala, M., Peterson, P. A. & Yang, Y. The roles of claudin superfamily proteins in paracellular transport. Traffic 2, 93–98 (2001).

Luettig, J., Rosenthal, R., Barmeyer, C. & Schulzke, J. D. Claudin-2 as a mediator of leaky gut barrier during intestinal inflammation. Tissue Barriers 3, e977176 (2015).

Al-Sadi, R. et al. Occludin regulates macromolecule flux across the intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 300, G1054–G1064 (2011).

Al-Sadi, R. et al. Lactobacillus acidophilus induces a strain-specific and toll-like receptor 2-dependent enhancement of intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier and protection against intestinal inflammation. Am. J. Pathol. 191, 872–884 (2021).

Al-Sadi, R. et al. Interleukin-6 modulation of intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability is mediated by JNK pathway activation of claudin-2 gene. PLoS One 9, e85345 (2014).

Ye, D., Guo, S., Al-Sadi, R. & Ma, T. Y. MicroRNA regulation of intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability. Gastroenterology 141, 1323–1333 (2011).

Kaminsky, L. W., Al-Sadi, R. & Ma, T. Y. IL-1β and the intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier. Front. Immunol. 12, 767456 (2021).

Nighot, P. K., Leung, L. & Ma, T. Y. Chloride channel ClC- 2 enhances intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier function via regulation of caveolin-1 and caveolar trafficking of occludin. Exp. Cell Res. 352, 113–122 (2017).

Rawat, M. et al. IL1B increases intestinal tight junction permeability by up-regulation of MIR200C-3p, which degrades occludin mRNA. Gastroenterology 159, 1375–1389 (2020).

Cichon, C., Sabharwal, H., Rüter, C. & Schmidt, M. A. MicroRNAs regulate tight junction proteins and modulate epithelial/endothelial barrier functions. Tissue Barriers 2, e944446 (2014).

Bravo-Vázquez, L. A. et al. Functional implications and clinical potential of MicroRNAs in irritable bowel syndrome: a concise review. Dig. Dis. Sci. 68, 38–53 (2023).

Yang, X., et al. Whole transcriptome-based ceRNA network analysis revealed ochratoxin A-induced compromised intestinal tight junction proteins through WNT/Ca2+ signaling pathway. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 224, 112637 (2021).

Shen, Y. et al. miR-200b inhibits TNF-α-induced IL-8 secretion and tight junction disruption of intestinal epithelial cells in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 312, G123–G132 (2017).

Hou, Q. et al. MiR-144 increases intestinal permeability in IBS-D rats by targeting OCLN and ZO1. Cell Physiol. Biochem 44, 2256–2268 (2017).

Martínez, C. et al. miR-16 and miR-125b are involved in barrier function dysregulation through the modulation of claudin-2 and cingulin expression in the jejunum in IBS with diarrhoea. Gut 66, 1537–1538 (2017).

Wang, H., et al. Pro-inflammatory miR-223 mediates the cross-talk between the IL23 pathway and the intestinal barrier in inflammatory bowel disease. Genome Biol. 17, 58 (2016).

Zhou, Q. et al. MicroRNA 29 targets nuclear factor-κB-repressing factor and Claudin 1 to increase intestinal permeability. Gastroenterology 148, 158–169.e8 (2015).

Zhu, Y. et al. MicroRNA-29a mediates the impairment of intestinal epithelial integrity induced by intrauterine growth restriction in pig. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 312, G434–G442 (2017).

Zhou, Q., Souba, W. W., Croce, C. M. & Verne, G. N. MicroRNA-29a regulates intestinal membrane permeability in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 59, 775–784 (2010).

Chao, G. et al. MicroRNA-29a increased the intestinal membrane permeability of colonic epithelial cells in irritable bowel syndrome rats. Oncotarget 8, 85828–85837 (2017).

Zhu, H. et al. Inhibition of miRNA-29a regulates intestinal barrier function in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome by upregulating ZO-1 and CLDN1. Exp. Ther. Med 20, 155 (2020).

Ménard, S., Cerf-Bensussan, N. & Heyman, M. Multiple facets of intestinal permeability and epithelial handling of dietary antigens. Mucosal Immunol. 3, 247–259 (2010).

Buckley, A. & Turner, J. R. Cell biology of tight junction barrier regulation and mucosal disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 10, a029314 (2018).

Peterson, L. W. & Artis, D. Intestinal epithelial cells: regulators of barrier function and immune homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 141–153 (2014).

Mahapatro, M., Erkert, L. & Becker, C. Cytokine-mediated crosstalk between immune cells and epithelial cells in the gut. Cells 10, 111 (2021).

Al-Sadi, R., Boivin, M. & Ma, T. Mechanism of cytokine modulation of epithelial tight junction barrier. Front Biosci.14, 2765–2778 (2009).

Andrews, C., McLean, M. H. & Durum, S. K. Cytokine tuning of intestinal epithelial function. Front Immunol. 9, 1270 (2018).

Pavlidis, P., et al. Cytokine responsive networks in human colonic epithelial organoids unveil a molecular classification of inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Rep. 40, 111439 (2022).

Ma, T. Y. et al. TNF-alpha-induced increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability requires NF-kappa B activation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 286, G367–G376 (2004).

Ma, T. Y., Boivin, M. A., Ye, D., Pedram, A. & Said, H. M. Mechanism of TNF-{alpha} modulation of Caco-2 intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier: role of myosin light-chain kinase protein expression. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 288, G422–G430 (2005).

Watari, A. et al. Rebeccamycin attenuates TNF-α-induced intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction by inhibiting myosin light chain kinase production. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 41, 1924–1934 (2017).

Leppkes, M., Roulis, M., Neurath, M. F., Kollias, G. & Becker, C. Pleiotropic functions of TNF-α in the regulation of the intestinal epithelial response to inflammation. Int. Immunol. 26, 509–515 (2014).

Al-Sadi, R., Guo, S., Ye, D. & Ma, T. Y. TNF-α modulation of intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier is regulated by ERK1/2 activation of Elk-1. Am. J. Pathol. 183, 1871–1884 (2013).

Al-Sadi, R., Guo, S., Ye, D., Rawat, M. & Ma, T. Y. TNF-α modulation of intestinal tight junction permeability is mediated by NIK/IKK-α axis activation of the canonical NF-κB pathway. Am. J. Pathol. 186, 1151–1165 (2016).

Capaldo, C. T. et al. Proinflammatory cytokine-induced tight junction remodeling through dynamic self-assembly of claudins. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 2710–2719 (2014).

Cao, M., Wang, P., Sun, C., He, W. & Wang, F. Amelioration of IFN-γ and TNF-α-induced intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction by berberine via suppression of MLCK-MLC phosphorylation signaling pathway. PLoS One 8, e61944 (2013).

Al-Sadi, R. M. & Ma, T. Y. IL-1beta causes an increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability. J. Immunol. 178, 4641–4649 (2007).

Al-Sadi, R. et al. Mechanism of interleukin-1β induced-increase in mouse intestinal permeability in vivo. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 32, 474–484 (2012).

Al-Sadi, R., Ye, D., Said, H. M. & Ma, T. Y. Cellular and molecular mechanism of interleukin-1β modulation of Caco-2 intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier. J. Cell Mol. Med. 15, 970–982 (2011).

Al-Sadi, R., Ye, D., Said, H. M. & Ma, T. Y. IL-1beta-induced increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability is mediated by MEKK-1 activation of canonical NF-kappaB pathway. Am. J. Pathol. 177, 2310–2322 (2010).

Clayburgh, D. R. et al. Epithelial myosin light chain kinase-dependent barrier dysfunction mediates T cell activation-induced diarrhea in vivo. J. Clin. Investig. 115, 2702–2715 (2005).

Zuo, L., Kuo, W. -T. & Turner, J. R. Tight junctions as targets and effectors of mucosal immune homeostasis. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10, 327–340 (2020).

Zolotarevsky, Y. et al. A membrane-permeant peptide that inhibits MLC kinase restores barrier function in in vitro models of intestinal disease. Gastroenterology 123, 163–172 (2002).

Shen, L. et al. Myosin light chain phosphorylation regulates barrier function by remodeling tight junction structure. J. Cell Sci. 119, 2095–2106 (2006).

Saitou, M. et al. Complex phenotype of mice lacking occludin, a component of tight junction strands. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 4131–4142 (2000).

Schulzke, J. D. et al. Epithelial transport and barrier function in occludin-deficient mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1669, 34–42 (2005).

Saitou, M. et al. Occludin-deficient embryonic stem cells can differentiate into polarized epithelial cells bearing tight junctions. J. Cell Biol. 141, 397–408 (1998).

Marchiando, A. M. et al. Caveolin-1-dependent occludin endocytosis is required for TNF-induced tight junction regulation in vivo. J. Cell Biol. 189, 111–126 (2010).

Van Itallie, C. M., Fanning, A. S., Holmes, J. & Anderson, J. M. Occludin is required for cytokine-induced regulation of tight junction barriers. J. Cell Sci. 123, 2844–2852 (2010).

Sanchez-Munoz, F., Dominguez-Lopez, A. & Yamamoto-Furusho, J. -K. Role of cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 14, 4280–4288 (2008).

Műzes, G., Molnár, B., Tulassay, Z. & Sipos, F. Changes of the cytokine profile in inflammatory bowel diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 18, 5848–5861 (2012).

Korolkova, O. Y., Myers, J. N., Pellom, S. T., Wang, L. & M’Koma, A. E. Characterization of serum cytokine profile in predominantly colonic inflammatory bowel disease to delineate ulcerative and Crohn’s colitides. Clin. Med. Insights Gastroenterol. 8, 29–44 (2015).

Schreiner, P. et al. Mechanism-based treatment strategies for IBD: cytokines, cell adhesion molecules, JAK inhibitors, gut flora, and more. Inflamm. Intest. Dis. 4, 79–96 (2019).

Cai, Z., Wang, S. & Li, J. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a comprehensive review. Front Med.8, 765474 (2021).

Friedrich, M., Pohin, M. & Powrie, F. Cytokine networks in the pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel disease. Immunity 50, 992–1006 (2019).

Al-Sadi, R., Ye, D., Dokladny, K. & Ma, T. Y. Mechanism of IL-1beta-induced increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability. J. Immunol. 180, 5653–5661 (2008).

Nata, T. et al. MicroRNA-146b improves intestinal injury in mouse colitis by activating nuclear factor-κB and improving epithelial barrier function. J. Gene Med. 15, 249–260 (2013).

Yarani, R. et al. Differentially expressed miRNAs in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Front. Immunol. 13, 865777 (2022).

Wu, F. et al. MicroRNAs are differentially expressed in ulcerative colitis and alter expression of macrophage inflammatory peptide-2 alpha. Gastroenterology 135, 1624–1635.e24 (2008).

Dai, X. et al. MicroRNA-193a-3p reduces intestinal inflammation in response to microbiota via down-regulation of colonic PepT1. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 16099–16115 (2015).

Polytarchou, C. et al. MicroRNA214 is associated with progression of ulcerative colitis, and inhibition reduces development of colitis and colitis-associated cancer in mice. Gastroenterology 149, 981–992.e11 (2015).

Zhang, L., Shen, J., Cheng, J. & Fan, X. MicroRNA-21 regulates intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability. Cell Biochem. Funct. 33, 235–240 (2015).

Yang, Y. et al. Overexpression of miR-21 in patients with ulcerative colitis impairs intestinal epithelial barrier function through targeting the Rho GTPase RhoB. Biochem. Biophys. Res Commun. 434, 746–752 (2013).

Min, M. et al. MicroRNA-155 is involved in the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis by targeting FOXO3a. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 20, 652–659 (2014).

Takagi, T. et al. Increased expression of microRNA in the inflamed colonic mucosa of patients with active ulcerative colitis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 25, S129–S133 (2010).

Bao, Y., et al. Long noncoding RNA BFAL1 mediates enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis-related carcinogenesis in colorectal cancer via the RHEB/mTOR pathway. Cell Death Dis. 10, 675 (2019).

Markey, G. E. et al. Hypoxia-inducible microRNA-155 negatively regulates epithelial barrier in eosinophilic esophagitis by suppressing tight junction claudin-7. FASEB J. 38, e23358 (2024).

Zhong, W., Chen, J., Xu, G. & Xiao, L. Kaempferol ameliorated alcoholic hepatitis through improving intestinal barrier function by targeting miRNA-155 signaling. Pharmacology https://doi.org/10.1159/000537964 (2024).

Lv, Q., et al. Alpinetin exerts anti-colitis efficacy by activating AhR, regulating miR-302/DNMT-1/CREB signals, and therefore promoting Treg differentiation. Cell Death Dis. 9, 890 (2018).

Runtsch, M. C. et al. MicroRNA-146a constrains multiple parameters of intestinal immunity and increases susceptibility to DSS colitis. Oncotarget 6, 28556–28572 (2015).

Neudecker, V., Yuan, X., Bowser, J. L. & Eltzschig, H. K. MicroRNAs in mucosal inflammation. J. Mol. Med ((Berl.)) 95, 935–949 (2017).

Iborra, M. et al. Identification of serum and tissue micro-RNA expression profiles in different stages of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 173, 250–258 (2013).

Zhao, J. et al. circSMAD4 promotes experimental colitis and impairs intestinal barrier functions by targeting Janus kinase 2 through sponging miR-135a-5p. J. Crohn’s. Colitis 17, 593–613 (2023).

Wani, S., Man Law, I. K. & Pothoulakis, C. Role and mechanisms of exosomal miRNAs in IBD pathophysiology. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 319, G646–G654 (2020).

Mitsuhashi, S. et al. Luminal extracellular vesicles (EVs) in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) exhibit proinflammatory effects on epithelial cells and macrophages. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 22, 1587–1595 (2016).

Valadi, H. et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 654–659 (2007).

Shen, Q., Huang, Z., Yao, J. & Jin, Y. Extracellular vesicles-mediated interaction within intestinal microenvironment in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Adv. Res. 37, 221–233 (2022).

Deng, F. et al. M2 macrophage-derived exosomal miR-590-3p attenuates DSS-induced mucosal damage and promotes epithelial repair via the LATS1/YAP/ β-catenin signalling axis. J. Crohns Colitis 15, 665–677 (2021).

Bui, T. M., Mascarenhas, L. A. & Sumagin, R. Extracellular vesicles regulate immune responses and cellular function in intestinal inflammation and repair. Tissue Barriers 6, e1431038 (2018).

Cai, X. et al. hucMSC-derived exosomes attenuate colitis by regulating macrophage pyroptosis via the miR-378a-5p/NLRP3 axis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 12, 416 (2021).

Wang, G., et al. HucMSC-exosomes carrying miR-326 inhibit neddylation to relieve inflammatory bowel disease in mice. Clin. Transl. Med. 10, e113 (2020).

Sun, D., et al. MiR-200b in heme oxygenase-1-modified bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes alleviates inflammatory injury of intestinal epithelial cells by targeting high mobility group box 3. Cell Death Dis. 11, 480 (2020).

Li, M., et al. Mast cells-derived MiR-223 destroys intestinal barrier function by inhibition of CLDN8 expression in intestinal epithelial cells. Biol. Res. 53, 12 (2020).

Bakirtzi, K., Man Law, I. K., Fang, K., Iliopoulos, D. & Pothoulakis, C. MiR-21 in Substance P-induced exosomes promotes cell proliferation and migration in human colonic epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 317, G802–G810 (2019).

Guo, M. -M., Zhang, K. & Zhang, J. -H. Human breast milk-derived exosomal miR-148a-3p protects against necrotizing enterocolitis by regulating p53 and Sirtuin 1. Inflammation 45, 1254–1268 (2022).

Nie, H. et al. Intestinal epithelial Krüppel-like factor 4 alleviates endotoxemia and atherosclerosis through improving NF-κB/miR-34a-mediated intestinal permeability. Acta Pharmacol. Sin https://doi.org/10.1038/s41401-024-01238-3 (2024).

Xie, M. -Y., et al. Porcine milk exosome miRNAs protect intestinal epithelial cells against deoxynivalenol-induced damage. Biochem. Pharm. 175, 113898 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Circulating exosomal microRNA-18a-5p accentuates intestinal inflammation in Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis by targeting RORA. Am. J. Transl. Res 13, 4182–4196 (2021).

Hu, G. et al. Release of luminal exosomes contributes to TLR4-mediated epithelial antimicrobial defense. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003261 (2013).

Zahm, A. M. et al. Circulating microRNA is a biomarker of pediatric Crohn disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 53, 26–33 (2011).

James, J. P. et al. MicroRNA biomarkers in IBD-differential diagnosis and prediction of colitis-associated cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 7893 (2020).

Masi, L. et al. MicroRNAs as innovative biomarkers for inflammatory bowel disease and prediction of colorectal cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 7991 (2022).

Ayyar, K. K. & Moss, A. C. Exosomes in intestinal inflammation. Front. Pharm. 12, 658505 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. Exosome-induced regulation in inflammatory bowel disease. Front Immunol. 10, 1464 (2019).

Stremmel, W., Weiskirchen, R. & Melnik, B. C. Milk exosomes prevent intestinal inflammation in a genetic mouse model of ulcerative colitis: a pilot experiment. Inflamm. Intest Dis. 5, 117–123 (2020).

Park, E. J., Shimaoka, M. & Kiyono, H. Functional flexibility of exosomes and MicroRNAs of intestinal epithelial cells in affecting inflammation. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 854487 (2022).

Ocansey, D. K. W. et al. Exosome-mediated effects and applications in inflammatory bowel disease. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 95, 1287–1307 (2020).

Liu, H., et al. Exosomes from mesenchymal stromal cells reduce murine colonic inflammation via a macrophage-dependent mechanism. JCI Insight 4, 131273 (2019), e131273

Yang, S. et al. A novel therapeutic approach for inflammatory bowel disease by exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells to repair intestinal barrier via TSG-6. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 12, 315 (2021).

Krissansen, G. W. et al. Overexpression of miR-595 and miR-1246 in the sera of patients with active forms of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 21, 520–530 (2015).

Chen, P., et al. Serum exosomal microRNA-144-3p: a promising biomarker for monitoring Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterol. Rep. 10, goab056 (2022).

Sun, L. et al. MicroRNAs as potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Int. Med. Res. 50, 3000605221089503 (2022).

Felli, C., Baldassarre, A. & Masotti, A. Intestinal and circulating MicroRNAs in coeliac disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 1907 (2017).

Zhong, Y., et al. Circular RNAs function as ceRNAs to regulate and control human cancer progression. Mol. Cancer 17, 79 (2018).

Song, W. & Fu, T. Circular RNA-associated competing endogenous RNA network and prognostic nomogram for patients with colorectal cancer. Front. Oncol. 9, 1181 (2019).

Yu, M. et al. A novel circRNA-miRNA-mRNA network revealed exosomal circ-ATP10A as a biomarker for multiple myeloma angiogenesis. Bioengineered 13, 667–683 (2022).

Asri, N. et al. The role of miR-197-3p in regulating the tight junction permeability of celiac disease patients under gluten free diet. Mol. Biol. Rep. 50, 2007–2014 (2023).

Ouyang, W., Wu, M., Wu, A. & Xiao, H. Circular RNA_0001187 participates in the regulation of ulcerative colitis development via upregulating myeloid differentiation factor 88. Bioengineered 13, 12863–12875 (2022).

Wang, T. et al. Integrated analysis of circRNAs and mRNAs expression profile revealed the involvement of hsa_circ_0007919 in the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis. J. Gastroenterol. 54, 804–818 (2019).

Li, F. et al. Overexpression of circAtp9b in ulcerative colitis is induced by lipopolysaccharides and upregulates PTEN to promote the apoptosis of colonic epithelial cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 22, 1404 (2021).

Guglielmi, G. et al. Expression of circulating let-7e and miR-126 may predict clinical remission in patients with Crohn’s disease treated with anti-TNF-α biologics. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 30, 441–446 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. MALAT1 maintains the intestinal mucosal homeostasis in Crohn’s disease via the miR-146b-5p-CLDN11/NUMB pathway. J. Crohns Colitis 15, 1542–1557 (2021).

Ma, D. et al. CCAT1 lncRNA promotes inflammatory bowel disease malignancy by destroying intestinal barrier via downregulating miR-185-3p. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 25, 862–874 (2019).

Zhang, B. et al. MicroRNA-122a regulates zonulin by targeting EGFR in intestinal epithelial dysfunction. Cell Physiol. Biochem 42, 848–858 (2017).

Xiong, Y., Wang, J., Chu, H., Chen, D. & Guo, H. Salvianolic acid B restored impaired barrier function via downregulation of MLCK by microRNA-1 in rat colitis model. Front Pharm. 7, 134 (2016).

Yu, T. et al. Overexpression of miR-429 impairs intestinal barrier function in diabetic mice by down-regulating occludin expression. Cell Tissue Res. 366, 341–352 (2016).

Tang, S., Guo, W., Kang, L. & Liang, J. MiRNA-182-5p aggravates experimental ulcerative colitis via sponging Claudin-2. J. Mol. Histol. 52, 1215–1224 (2021).

Wang, M., Guo, J., Zhao, Y. -Q. & Wang, J. -P. IL-21 mediates microRNA-423-5p /claudin-5 signal pathway and intestinal barrier function in inflammatory bowel disease. Aging12, 16099–16110 (2020).

Li, L. et al. Cytokine IL9 triggers the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease through the miR21-CLDN8 pathway. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 24, 2211–2223 (2018).

Zhuang, X., et al. Hypermethylation of miR-145 promoter-mediated SOX9-CLDN8 pathway regulates intestinal mucosal barrier in Crohn’s disease. EBioMedicine 76, 103846 (2022).

Guo, J. -G., Rao, Y. -F., Jiang, J., Li, X. & Zhu, S. -M. MicroRNA-155-5p inhibition alleviates irritable bowel syndrome by increasing claudin-1 and ZO-1 expression. Ann. Transl. Med. 11, 34 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Silencing LncRNA-DANCR attenuates inflammation and DSS-induced endothelial injury through miR-125b-5p. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 44, 644–653 (2021).

Scalavino, V. et al. miR-195-5p regulates tight junctions expression via claudin-2 downregulation in ulcerative colitis. Biomedicines 10, 919 (2022).

Scalavino, V. et al. The increase of miR-195-5p reduces intestinal permeability in ulcerative colitis, modulating tight junctions’ expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 5840 (2022).

Chu, Y., et al. Tetrandrine attenuates intestinal epithelial barrier defects caused by colitis through promoting the expression of Occludin via the AhR-miR-429 pathway. FASEB J. 35, e21502 (2021).

Kumar, V. et al. miR-130a and miR-212 disrupt the intestinal epithelial barrier through modulation of PPARγ and occludin expression in chronic simian immunodeficiency virus-infected Rhesus Macaques. J. Immunol. 200, 2677–2689 (2018).

Liu, Z. et al. MicroRNA-21 increases the expression level of occludin through regulating ROCK1 in prevention of intestinal barrier dysfunction. J. Cell Biochem. 120, 4545–4554 (2019).

Cao, Y. -Y., Wang, Z., Wang, Z. -H., Jiang, X. -G. & Lu, W. -H. Inhibition of miR-155 alleviates sepsis-induced inflammation and intestinal barrier dysfunction by inactivating NF-κB signaling. Int Immunopharmacol. 90, 107218 (2021).

Béres, N. J. et al. Role of altered expression of miR-146a, miR-155, and miR-122 in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 22, 327–335 (2016).

Lu, X., Yu, Y. & Tan, S. The role of the miR-21-5p-mediated inflammatory pathway in ulcerative colitis. Exp. Ther. Med. 19, 981–989 (2020).

El-Daly, S. M., Omara, E. A., Hussein, J., Youness, E. R. & El-Khayat, Z. Differential expression of miRNAs regulating NF-κB and STAT3 crosstalk during colitis-associated tumorigenesis. Mol. Cell Probes 47, 101442 (2019).

Lai, C. -Y. et al. MicroRNA-21 plays multiple oncometabolic roles in colitis-associated carcinoma and colorectal cancer via the PI3K/AKT, STAT3, and PDCD4/TNF-α signaling pathways in zebrafish. Cancers13, 5565 (2021).

He, C. et al. MicroRNA 301A promotes intestinal inflammation and colitis-associated cancer development by inhibiting BTG1. Gastroenterology 152, 1434–1448.e15 (2017).

Wang, T. et al. miR-19a promotes colitis-associated colorectal cancer by regulating tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced protein 3-NF-κB feedback loops. Oncogene 36, 3240–3251 (2017).

Signs, S. A. et al. Stromal miR-20a controls paracrine CXCL8 secretion in colitis and colon cancer. Oncotarget 9, 13048–13059 (2018).

Zhu, Y. et al. miR-148a inhibits colitis and colitis-associated tumorigenesis in mice. Cell Death Differ. 24, 2199–2209 (2017).

Tang, K. et al. Elevated MMP10/13 mediated barrier disruption and NF-κB activation aggravate colitis and colon tumorigenesis in both individual or full miR-148/152 family knockout mice. Cancer Lett. 529, 53–69 (2022).

Lamichhane, S., Mo, J. -S., Sharma, G., Choi, T. -Y. & Chae, S. -C. MicroRNA 452 regulates IL20RA-mediated JAK1/STAT3 pathway in inflammatory colitis and colorectal cancer. Inflamm. Res 70, 903–914 (2021).

Zhang, W. et al. miR-26a attenuates colitis and colitis-associated cancer by targeting the multiple intestinal inflammatory pathways. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 24, 264–273 (2021).

Shi, C. et al. MicroRNA-21 knockout improve the survival rate in DSS induced fatal colitis through protecting against inflammation and tissue injury. PLoS One 8, e66814 (2013).

Guo, J., Yang, L. -J., Sun, M. & Xu, L. -F. Inhibiting microRNA-7 expression exhibited a protective effect on intestinal mucosal injury in TNBS-induced inflammatory bowel disease animal model. Inflammation 42, 2267–2277 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. Inhibition of miR-16 ameliorates inflammatory bowel disease by modulating Bcl-2 in mouse models. J. Surg. Res. 253, 185–192 (2020).

Tian, Y. et al. MicroRNA-31 reduces inflammatory signaling and promotes regeneration in colon epithelium, and delivery of mimics in microspheres reduces colitis in mice. Gastroenterology 156, 2281–2296.e6 (2019).

Neudecker, V. et al. Myeloid-derived miR-223 regulates intestinal inflammation via repression of the NLRP3 inflammasome. J. Exp. Med. 214, 1737–1752 (2017).

Xu, M. et al. MiR-155 contributes to Th17 cells differentiation in dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis mice via Jarid2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 488, 6–14 (2017).

Kim, H. -Y. et al. MicroRNA-132 and microRNA-223 control positive feedback circuit by regulating FOXO3a in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 31, 1727–1735 (2016).

Pierdomenico, M. et al. NOD2 is regulated by Mir-320 in physiological conditions but this control is altered in inflamed tissues of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 22, 315–326 (2016).

Li, M. et al. Upregulation of miR-665 promotes apoptosis and colitis in inflammatory bowel disease by repressing the endoplasmic reticulum stress components XBP1 and ORMDL3. Cell Death Dis. 8, e2699 (2017).

Shi, T. et al. The signaling axis of microRNA-31/interleukin-25 regulates Th1/Th17-mediated inflammation response in colitis. Mucosal Immunol. 10, 983–995 (2017).

Zhao, Y. et al. MicroRNA-124 promotes intestinal inflammation by targeting aryl hydrocarbon receptor in Crohn’s disease. J. Crohns Colitis 10, 703–712 (2016).

Tian, T., et al. MicroRNA-16 is putatively involved in the NF-κB pathway regulation in ulcerative colitis through adenosine A2a receptor (A2aAR) mRNA targeting. Sci. Rep. 6, 30824 (2016).

Wu, W. et al. MicroRNA-206 is involved in the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis via regulation of adenosine A3 receptor. Oncotarget 8, 705–721 (2017).

Mo, J. -S. et al. MicroRNA 429 regulates mucin gene expression and secretion in murine model of colitis. J. Crohns Colitis 10, 837–849 (2016).

Mahurkar-Joshi, S. et al. The colonic mucosal MicroRNAs, MicroRNA-219a-5p, and MicroRNA-338-3p are downregulated in irritable bowel syndrome and are associated with barrier function and MAPK signaling. Gastroenterology 160, 2409–2422.e19 (2021).

Cheng, W. et al. Exosomes-mediated transfer of miR-125a/b in cell-to-cell communication: a novel mechanism of genetic exchange in the intestinal microenvironment. Theranostics 10, 7561–7580 (2020).

Bauer, K. M., et al. CD11c+ myeloid cell exosomes reduce intestinal inflammation during colitis. JCI Insight 7, e159469 (2022).

Huang, Z. et al. miR-141 regulates colonic leukocytic trafficking by targeting CXCL12β during murine colitis and human Crohn’s disease. Gut 63, 1247–1257 (2014).

Larabi, A., Dalmasso, G., Delmas, J., Barnich, N. & Nguyen, H. T. T. Exosomes transfer miRNAs from cell-to-cell to inhibit autophagy during infection with Crohn’s disease-associated adherent-invasive E. coli. Gut Microbes 11, 1677–1694 (2020).

Cao, Y. et al. Enterotoxigenic bacteroidesfragilis promotes intestinal inflammation and malignancy by inhibiting exosome-packaged miR-149-3p. Gastroenterology 161, 1552–1566.e12 (2021).

Wang, S., Zhang, Z. & Gao, Q. Transfer of microRNA-25 by colorectal cancer cell-derived extracellular vesicles facilitates colorectal cancer development and metastasis. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 23, 552–564 (2021).