Abstract

Conventional computational pathology treats diagnostic tasks as independent and individual image classification problems, leading to inefficiencies and high costs. To address this, we introduce CAMP (Continuous and Adaptive learning Model in Pathology), a unified and universal framework for pathology image classification. CAMP is a generative and adaptive classification model that can continuously adapt to new tasks by leveraging pathology-specific prior knowledge and learning task-specific knowledge with minimal computational cost and without catastrophic forgetting. Evaluated CAMP on 22 datasets, including 1,171,526 patches and 11,811 pathology slides, across 17 classification tasks, CAMP achieves state-of-the-art classification performance at both patch- and slide-levels. It also reduces up to 94% of computation time and 85% of storage memory in comparison to the conventional classification models. Our results demonstrate that CAMP can offer a fundamental transformation in pathology image classification, paving the way for the fully digitized and computerized pathology practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and imaging techniques and easy access to digital systems, computational pathology is promising to revolutionize and evolve the pathology landscape at a fast pace1. A recent study demonstrates that the impact of computational pathology will be significant in many aspects of the pathology workflow2, including but not limited to disease detection and diagnosis (e.g., lymphovascular invasion detection3,4 and colorectal cancer grading5,6,7), quantification (e.g., counting nuclei8,9 or mitosis10,11 and quantification of biomarkers12,13), standardization of the slide preparation14,15, and quality control and assurance of whole-slide images and reports16,17,18. However, a limited number of computational pathology tools have been adopted as a part of the routine clinical workflow19. Therefore, gaps or barriers exist in translating computational pathology tools into clinical practice.

A large portion of routine pathology practice can be formulated as an image classification task where an examiner (i.e., a pathologist) assigns a class label to an image of interest (e.g., biopsy specimens). Class labels can vary from the presence of cancer and metastasis, histological sub-types, to the survival rate of subjects. To tackle such classification tasks, the current practice of computational pathology, in general, focuses on a single task at a time, such that an individual and independent AI model, built based upon convolutional neural networks (CNNs)6,7,20,21,22 and/or vision transformers (ViT)23,24,25, is developed and validated per classification task. This approach has two major drawbacks. First, it cannot fully utilize the existing knowledge and resources. The characteristics of tissues among different tasks can be shared. For example, there can be two tasks for colorectal tissues, such as colorectal cancer grading with 4 categories (benign, well-differentiated cancer, moderately differentiated cancer, and poorly differentiated cancer) and colorectal tissue sub-typing with 7 categories (adipose, background, debris, lymphocyte, normal, stroma, and tumor). The structure and shape of liver cancers (benign, grade 1, grade 2, and grade 3) and kidney cancers (benign, grade 1, grade 2, grade 3, and grade 4) are analogous to each other. As AI models are individually and independently developed and validated, taking advantage of other related tissues and tasks is challenging. Second, it is not scalable. Some showed that the same AI model can be adopted for other classification tasks23, but one still needs to repeat the entire training and validation process per task. Though successful in resolving each task, this approach inevitably results in numerous computational pathology tools, as many as classification tasks in pathology, being implemented and utilized in clinics. Consequently, this comes at the cost of computational resources, maintenance, and energy. The more tools we use in clinics, the higher the cost and complexity it may add up to. Neither the scientific nor the medical communities have taken such costs and issues into account.

There are two ways to tackle the above problem. The first approach is to develop a unified AI model for all classification tasks26. As a new task is incorporated, the previous universal AI models need full training and validation for the new and existing tasks. Due to the vast number of tasks and data samples per task, training and deployment require a tremendous amount of time, which considerably limits the applicability of the method, and thus, it is infeasible. The second approach is to utilize a so-called foundation model that can be applied to a wide range of applications23,27,28,29,30. These models have recently drawn significant attention for their superior learning capability29. These can be applied to differing classification tasks with and without adaptation procedures via zero-shot learning. The most common adaptation strategy is fine-tuning and/or linear probing, yet no optimal adaptation strategy for each task is available. The more fine-tuned or adjusted the model is, the higher performance it achieves per task. However, this approach suffers from catastrophic forgetting, which is a phenomenon where AI models lose the information from the previous tasks as learning or adapt to a new task31,32. Using foundation models without adaptation is also not an option since there is a considerable performance gap between zero-shot learning and traditional supervised learning. Therefore, the field of computational pathology needs not only a new type of AI model but also an efficient and effective manner of training and adaptation methodologies to handle a variety of classification tasks together without substantial loss of information and performance.

In this study, we propose a Continuous and Adaptive learning Model in Pathology, so-called CAMP, as a generic, unified, and universal framework for pathology image classification, which addresses the challenges and limitations of the current pathology image classification approaches in computational pathology as outlined above. The major strength of CAMP is fourfold. First, CAMP is a generative model. It transforms or reformulates the image classification problems as text generation problems; for instance, given a pathology image, CAMP directly generates a text phrase or label, such as in situ carcinoma and mucus, instead of choosing an index designated to the particular class label. Second, CAMP is adaptive. It can adapt to a given classification task without losing prior knowledge and classification performance, allowing it to learn from new tasks continuously. Third, CAMP is efficient. To adapt to a new task, CAMP only trains a minor number of learnable parameters for new task-specific knowledge, while the common knowledge and other tasks’ knowledge are decoupled and preserved. Therefore, minimal modifications and costs are required for the adaptation, which maintains the efficiency of CAMP when increasing the number of downstream tasks. Fourth, CAMP is versatile. It is able to conduct various classification tasks in pathology at both the patch level and the whole-slide image (WSI) level with high accuracy by adapting itself to each task efficiently and effectively. In experiments with 17 classification tasks, including 1,171,526 patches and 11,811 slides from 22 pathology image classification datasets originating from 8 different organs (Fig. 3), we demonstrate that CAMP is highly adaptive and efficient in learning and conducting a variety of classification tasks as well, and can achieve highly accurate classification results regardless of the types of classification tasks, organs, and datasets.

We build CAMP under the following hypotheses: (1) there exists common knowledge for pathology image analysis that is applicable to any classification tasks; (2) tasks are distinctive from each other, and thus, there also exists task-specific knowledge; (3) both common and task-specific knowledge is required to achieve high performance in each task. In order to utilize the common knowledge, we adopt the pre-trained weights trained on a large-scale pathology image dataset. As for the task-specific knowledge, we employ adapters that are adjusted and optimized per task. Then, the weights of the adapters (i.e., task-specific knowledge) are added to the pre-trained weights (i.e., common knowledge on pathology images) to conduct a particular classification task.

CAMP receives two inputs, including a pathology patch/slide and a text prompt. The text prompt instructs CAMP on which task it needs to conduct, such as "The cancer sub-type of this breast tissue is”. CAMP processes the two inputs and generates the text label by combining and utilizing both a visual model (a visual encoder) and a language model (a text decoder). The visual model extracts image features from the input pathology image. The image features are fused with the text embedding, extracted from the text prompt by the language model, and fed into the language model to produce the text label in an auto-regressive manner. In CAMP, common knowledge in a single visual and language model is sufficient to perform numerous classification tasks. In other words, the same visual and language model is shared among various types of classification tasks. The conventional methods, however, need to adopt at least two separate layers with the same or differing numbers of neurons (or processing units) to conduct two classification tasks together. Though the intermediate layers can be shared between two models and employed from the previous models via transfer learning, the new layers are often randomly initialized. These may contribute to the increase in the size and complexity of the classification models and the decrease in the classification performance due to the lack of prior knowledge of pathology. However, CAMP does not suffer from such issues with computational complexity and performance degradation, holding the potential for transforming the approaches to classification tasks.

CAMP is a framework for image classification tasks in computational pathology, transitioning from the long-lasting discriminating approaches to the generative approaches, from the category assignment to the text generation, and from static learning to dynamic and continual learning (Figs. 1 and 2). We systematically evaluate the ability of CAMP on one of the most extensive collections of pathology images and tasks ever used together for image classification tasks (Fig. 3). We show that CAMP is superior to the conventional image classification models in computational pathology and other domains. We also investigate the effect of the prior knowledge, i.e., pre-trained weights and the text prompt, on the classification performance. Moreover, we examine the computational requirements of CAMP and other methods to validate the scalability and utility of CAMP in clinics.

The numbers in the brackets index the order of the procedure. a For each patch classification task, the image-text prompt input and text ground truth are generated. The patch query generation is generated by a pre-trained visual encoder and a pre-trained text decoder. b During training, \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\) is used for optimizing adapters, whereas \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\mathcal{K}}}\) is utilized for updating a key. This process only updates the training task and preserves the knowledge of previously learned tasks. c During inference, a query is generated based on an input to retrieve the most suitable adapters. After being integrated with the adapters, CAMP generates a textual prediction.

The numbers in the brackets index the order of the procedure. a For each slide classification task, the image-text prompt input and text ground truth are generated. The slide query generation is produced by a pre-trained visual encoder, a pre-trained text decoder, and a non-parametric aggregator. b Similar to patch-level, \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\) and \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\mathcal{K}}}\) are used for optimizing adapters and a key during training a current task. A visual encoder is frozen in this process. c The slide-level inference is similar to patch-level, except for the adapters. Note that the aggregator (blue) in the generative model is parametric, which is different from the non-parametric aggregator (gray) in the query generation procedure.

Results

CAMP improves the performance of pathology foundation models on a wide range of patch- and slide-level classification tasks

To investigate the effectiveness of CAMP, four pathology foundation models, including CTransPath23, Phikon30, UNI28, and Virchow233, were employed and compared to the framework of CAMP on 22 datasets from 8 organs with 17 patch-level datasets (11 tasks with about 1.1 million images) and on 5 slide-level datasets (6 tasks with nearly 12,000 WSIs). In other words, each of the four foundation models was individually and independently fine-tuned per classification task via linear probing, while four CAMP models (CAMP-CTransPath, CAMP-Phikon, and CAMP-UNI) were built and optimized for the entire slide- and patch-level classification tasks by using the corresponding foundation model as \({\mathcal{V}}\). For CAMP models, the text decoder is adopted from PLIP27. The results were measured using F1, accuracy, quadratic-weighted kappa, precision, and recall. Here, we primarily evaluate the models using F1 since it can be shared among different types of tasks. The detailed results are shown in Supplementary Tables 1–27. Figures 4 and 5 demonstrate the performance of CAMP with four pathology foundation models on both slide-level and patch-level datasets. Across all 17 patch-level datasets, it was noticeable that CAMP improves upon the performance of the pathology foundation models. In a head-to-head comparison, CAMP, on average, increased F1 by 4.41% for CTransPath, 4.40% for UNI, and 5.12% for Phikon. We observed that the effect of CAMP varied across the datasets. For example, for colorectal cancer grading, CAMP increased F1 by 1.4%, 4.6%, 4.1%, and 2.1% for CTransPath, UNI, Phikon, and Virchow2, respectively, on Colon-1. F1 was further improved on Colon-2, such as +4.3% for CTransPath, +4.4% for UNI, +6.3% for Phikon, and +2.1% for Virchow2. As for colorectal tissue sub-typing (K19, K16, and HunCRCP), the average improvement in F1 by CAMP was 0.3%, 4.0%, and 10.0% for K19, K16, and HunCRCP, respectively. In regard to prostate cancer grading (UHU, UBC, AGGC, and PANDAP), CAMP substantially enhanced the performance of the foundation models except for Phikon on UBC, where F1 was dropped by 1.1% by CAMP-Phikon in comparison to Phikon; on AGGC, which is highly imbalanced toward grade-4 samples (more than 50%), CAMP attained the greatest performance improvement in F1 by 14.3%, 7.8%, 11.4%, and 3.4% for CTransPath, UNI, Phikon, Virchow2, respectively. Across all 5 slide-level datasets, CAMP, in general, offered the superior performance gain for the four pathology foundation models regardless of the type of aggregators. Overall, using CAMP, the classification performance, measured by F1, was improved by 2.59% for breast cancer detection (CAMELYON16), 4.15% for colon tissue sub-typing (HunCRC-S), 3.69% for kidney cancer sub-typing (DHMC), 3.85% for prostate cancer grading (PANDA-S), 3.11% for coarse-grained breast cancer sub-typing (BRACS-3), and 6.63% for fine-grained breast cancer sub-typing (BRACS-7). There were only two exceptions where CAMP was inferior to the foundation model; F1 of CAMP-UNI decreased by 1.2% and 1.9% in comparison to that of UNI on BRACS3 on HumCRCW, respectively. For Virchow2, CAMP consistently provided modest but stable improvements, yielding, on average a 1–2% F1 gain across datasets, which further demonstrates its adaptability to different visual encoders. Regarding the four aggregators, CAMP, on average, increased F1 by 4.12%, 3.75%, 3.83%, and 4.31% for CLAM-MB, TransMIL, IB-MIL, and AB-MIL, respectively.

The results on the patch- and slide-level classification tasks suggest that CAMP is capable of conducting a variety of classification tasks at both patch- and slide-levels with high accuracy, CAMP is able to improve upon the pathology foundation models across different datasets and tasks, CAMP is robust to the choice of \({\mathcal{V}}\) and/or aggregator, and thus CAMP can serve as a generic framework for classification tasks. Among the four CAMP models (CAMP-CTransPath, CAMP-Phikon, CAMP-UNI, and CAMP-Virchow2), the performance of CAMP-CTransPath was, in general, inferior to that of the other three models on both patch- and slide-level classification tasks. Comparing CAMP-Phikon, CAMP-UNI, and CAMP-Virchow2, the two models achieved comparable performance; however, the computational complexity and memory requirement were much more substantial for CAMP-UNI and CAMP-Virchow2 since Phikon is based on 86M-param ViT-Base while UNI and Virchow2 are built on 307M-param ViT-Large and 632M-param ViT-H. Hence, we chose Phikon as the default visual encoder \({\mathcal{V}}\) for CAMP, i.e., CAMP-Phikon is used to further evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of CAMP in comparison to other classification models under various settings.

CAMP outperforms fully fine-tuned vision models

We further evaluated the classification performance of CAMP on the 11 patch-level classification tasks (colorectal cancer grading, prostate cancer grading, gastric cancer grading, bladder cancer grading, liver cancer grading, kidney cancer grading, breast cancer sub-typing, colorectal tissue sub-typing, colorectal polyp sub-typing, breast metastasis detection, and lung cancer detection) from 8 organs. There are 13 datasets that were split into training, validation, and testing sets. Using them, we trained CAMP in a serial fashion. The trained CAMP is applied to 4 external datasets (1 for colorectal cancer grading, 2 for prostate cancer grading, and 1 for colorectal tissue sub-typing) to test the generalization ability of CAMP on unseen datasets. We compared CAMP with 10 classification models (4 deep vision models: ConvNeXt-B, RegNet, ViT-B, and SwinV2-B, 4 task-agnostic deep vision models: ConvNeXt-BTA, RegNetTA, ViT-BTA, and SwinV2-BTA, and 2 generative models: GPC and GIT-B). Figure 6b, d shows the comparison between CAMP and other competitors in terms of F1 on the 17 datasets. Detailed results of all evaluation metrics are reported in Supplementary Tables 1–11.

a The three configurations under consideration are task-specific, task-agnostic, and task-agnostic generative classification. b, d CAMP performs better than other considered methods in 16/17 patch-level datasets. The numbers in the bar show the gap between CAMP and the second-best competitors. c Comparison between CAMP and competitors in terms of the computation time and memory consumption during training and inference.

Overall, CAMP was able to conduct the 11 different classification tasks in an accurate and consistent manner (Fig. 6), achieving 0.756~0.861 F1, 0.809 F1, 0.488~0.905 F1, 0.478~0.998 F1, 0.961 F1, 0.915 F1, 0.895 F1, 0.782 F1, 0.985 F1, 0.486 F1, and 0.838 F1 for colorectal cancer grading (Colon-1 and Colon-2), gastric cancer grading, prostate cancer grading (UHU, UBC, AGGC, and PANDA), colorectal tissue sub-typing (K19, K16, and HunCRCP), liver cancer grading, kidney cancer grading, bladder cancer grading, breast cancer sub-typing, breast metastasis detection, colorectal polyp sub-typing and lung cancer detection, respectively.

CAMP outperformed the 4 task-specific competitors in 16 of 17 datasets; the exception is BACH (breast cancer sub-typing), where RegNet obtained an F1 of 0.782, whereas CAMP achieved an F1 of 0.771. It was remarkable that CAMP is superior to the second-best task-specific models by 3.6%~5.1% in colorectal cancer grading, 4.5% in gastric cancer grading, 2.5%~8.2% in prostate cancer grading, 0.1%~11.4% in colorectal tissue sub-typing, 0.2% in liver cancer grading, 2.9% in kidney cancer grading, 1.8% in bladder cancer grading, 0.3% in breast metastasis detection, 1.2% in lung cancer detection, and 11.7% in colorectal polyp sub-typing. We note that the second-best task-specific model varied depending on the datasets. This indicates that the performance of the task-specific models, which were fully fine-tuned for downstream tasks, is inconsistent across differing datasets and tasks, whereas CAMP permits reliable and superior performance on a wide range of tasks and datasets.

Furthermore, CAMP surpassed the 6 task-agnostic competitors across the 11 classification tasks except for liver cancer grading. We made similar observations; CAMP outperformed the second-best task-agnostic models by 0.2%~4.7% in colorectal cancer grading, 5.3% in gastric cancer grading, 2.1%~5.6% in prostate cancer grading, 0.1%~3.6% in colorectal tissue sub-typing, 3.0% in kidney cancer grading, 1.2% in bladder cancer grading, 0.4% in breast metastasis detection, 2.1% in lung cancer detection, and 11.7% in colorectal polyp sub-typing; the performance of the task-agnostic models was unsteady, and thus the second-best model differed from one dataset to another. It is worth noting that the task-agnostic models were trained on the entire collection of the training datasets from the 11 classification tasks. This implies that the vanilla framework of the task-agnostic models is sub-optimal, and the superior performance by CAMP is not simply due to the usage of the large datasets.

CAMP outperforms multi-task MIL classifiers but reveals limitations of patch-based approaches for WSI-level classification

To further assess the effectiveness of CAMP for slide-level classification, we compared it against a multi-task MIL, designated as Unified MIL, which utilizes a single model for all classification tasks using AB-MIL. Table 28 reports the performance of CAMP and a multi-task MIL across five slide-level benchmark datasets. We observed that CAMP-UNI, CAMP-Phikon, and CAMP-Virchow2 consistently match or outperform Unified MIL in most evaluation metrics. CAMP-CTransPath was generally inferior to Unified MIL. On BRACS-3, the highest F1 was obtained by CAMP-Virchow2, with an improvement of 4.2% over Unified MIL. On BRACS-7, Unified MIL achieved the best F1 of 0.468, while CAMP-UNI and CAMP-CTransPath attained the second-best F1 of 0.451. On HunCRCW, CAMP-Phikon obtained the best F1 of 0.890, with a +4.6% gain in comparison to Unified MIL. For PANDAW, CAMP-Virchow2 was shown to be the best-performing model, improving F1 from 0.781 to 0.795, as compared to Unified MIL. Similarly, on DHMC, CAMP-UNI improved F1 from 0.869 to 0.890 over Unified MIL. Overall, these results demonstrate that CAMP provides more robust and balanced performance across diverse datasets, confirming the effectiveness of the proposed framework for multi-task slide-level classification.

Conventional MIL frameworks are typically constructed around task-specific classifiers that operate over aggregated patch-level features. Although these methods often share a common visual encoder, each MIL head is trained independently for a particular classification objective, with minimal interaction across tasks34,35,36. This design inherently precludes the sharing of representational structures beyond the encoder. At the level of the classification heads, knowledge transfer is therefore limited, and no common knowledge is maintained. In contrast, CAMP reformulates classification as a text-conditioned generation problem. Each task is expressed through a natural language query, and the model learns to generate the appropriate diagnostic response conditioned on this query. Within this framework, query-adapters act as lightweight, task-specific modules that modulate the shared generative backbone. This design offers a key advantage over conventional MIL: both encoder and decoder share common knowledge, and the generation-based formulation enables the decoder to fully exploit the shared knowledge for improved classification.

Moreover, we compared CAMP with WSI-level pathology foundation models for slide-level classification. Two WSI-level foundation models were employed, including Prov-GigaPath37 and CHIEF38. As shown in Table 29, the results show that both Prov-GigaPath and CHIEF outperform CAMP, achieving on average +4.4% and +4.6% higher F1 across five slide-level classification benchmarks. Specifically, CHIEF obtained the highest F1 of 0.790, 0.474, and 0.909 on BRACS-3, BRACS-7, and DHMC, while the best-performance CAMP variants, CAMP-Virchow2, CAMP-UNI, and CAMP-UNI, obtained 0.760, 0.451, and 0.885, respectively. On HunCRCW and PANDAW, the highest F1 of 0.910 and 0.829 were obtained by Prov-GigaPath, compared to 0.890 (CAMP-Phikon and CAMP-Virchow2) and 0.795 (CAMP-UNI and CAMP-Virchow2).

These results highlight an intrinsic limitation of patch-based approaches. WSI foundation models are highly specialized for slide-level recognition tasks, benefiting from both scale and domain-specific pre-training. In contrast, CAMP is built based on a patch-level visual encoder, which is specifically designed and trained on large-scale patch datasets. The performance gap can thus be attributable to fundamental differences in how slide-level classification is approached. While WSI-level pathology foundation models learn holistic slide-level representations optimized for global classification, CAMP and other patch-based approaches must aggregate dispersed local information across patches to arrive at a slide-level decision. Hence, such MIL-based aggregation strategies are inherently sub-optimal for slide-level classification.

Prior knowledge of pathology data plays a critical role

In CAMP, we employ the visual encoder \({\mathcal{V}}\) and the text decoder \({\mathcal{T}}\) that were pre-trained on a large pathology image data. \({\mathcal{V}}\) learned the pathology-specific knowledge from ~43 million pathology images via contrastive learning30, whereas \({\mathcal{T}}\) was trained on about 200,000 pathology images paired with text descriptions27. Therefore, CAMP was exposed to pathology data prior to the adaptation to downstream tasks, i.e., 11 classification tasks. To investigate the importance of the pathology-specific prior knowledge on CAMP, we conducted the classification tasks by replacing the weights of \({\mathcal{V}}\) and \({\mathcal{T}}\) with the weights obtained from the natural images and natural languages, which are designated as the general prior knowledge. Specifically, in the first experiment, the weights of \({\mathcal{V}}\) were substituted by those from ImageNet, producing \({{\mathcal{V}}}_{g}\), while the weights of \({\mathcal{T}}\) were kept the same. In the second experiment, we adopt the weights of the text decoder of CLIP39, which were pre-trained on 400 million natural image-text pairs, and used them as the weights for \({\mathcal{T}}\), assigned as \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{g}\), but retained \({\mathcal{V}}\). The last experiment employed \({{\mathcal{V}}}_{g}\) and \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{g}\), in which CAMP was only equipped with the general prior knowledge. In the absence of the pathology-specific prior knowledge, the classification performance in patch-level tasks generally dropped (Fig. 7a, b); for instance, the average performance drop for the patch-level classification tasks was −3.6%, −2.6%, and −3.8% by employing \({{\mathcal{V}}}_{g}\), \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{g}\), and both \({{\mathcal{V}}}_{g}\) and \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{g}\), respectively. Similar observations were made for the slide-level classification tasks, in which F1 decreased by 2.1% for \({{\mathcal{V}}}_{g}\), 1.5% for \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{g}\), and 2.5% for both \({{\mathcal{V}}}_{g}\) and \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{g}\). On the examination of each dataset, we found that the adoption of both \({{\mathcal{V}}}_{g}\) and \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{g}\) consistently results in a reduction in the classification performance; however, the degree of reduction in the performance varied across the datasets; for example, in the patch-level tasks, the largest performance drop of −6.68% was achieved in AGGC (prostate cancer grading) and, in PCam (breast metastasis detection), the least performance drop of −0.97% was attained. We also observed that \({\mathcal{V}}\) plays a crucial role in the classification at both patch- and slide-levels. The performance drop by \({{\mathcal{V}}}_{g}\) was almost always larger than the drop by \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{g}\), especially for the patch-level classification tasks. This might be due to the way CAMP processes the inputs and predicts the class labels. The output of the visual encoder is directly used for the text generation, and thus, the misinterpretation of the input image by the visual encoder would provide incorrect information for the text generation by the text decoder. In other words, the better the visual encoder is, the better information the text decoder attains, leading to improved classification performance.

Though the average performance had substantially dropped by \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{g}\), its effect was disproportionate across the classification tasks. For most of the tasks, CAMP with \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{g}\) resulted in the performance drop ranging from −1.03% (KMC-Liver) to −5.61% (AGGC) for the patch-level classification tasks and from −0.96% (HunCRCW with IB-MIL) to −4.32% (BRACS7 with TransMIL) for the slide-level classification tasks. For some cases, the adoption of \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{g}\) did not affect the slide-level tasks such as Camelyon16 by TransMIL and AB-MIL, DHMC by AB-MIL, and BRACS3 by AB-MIL. It even increased the patch-level classification performance by 1.33% and 2.02% for breast cancer detection (PCam) and lung cancer detection (WSSS4LUAD), respectively. This is a contributory factor in the small decrease in the performance when CAMP employed both \({{\mathcal{V}}}_{g}\) and \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{g}\). The increase in the performance by \({{\mathcal{T}}}_{g}\) may be ascribable to the nature of the classification tasks and class labels. For PCam and WSSS4LUAD, there exist only two labels, including normal and tumor, of which each label is relatively short and simple. Other classification tasks usually have more class labels; the labels tend to be long and complicated, such as tubular poorly differentiated cancer, invasive carcinoma, and lymphocyte, and/or the labels are infrequently used in natural languages.

CAMP is robust to the variations in the text prompt

CAMP needs two inputs, including a pathology image and a text prompt. In conclusion, the two inputs serve two purposes: one is to retrieve the appropriate adapters, and the other is to generate the text output using the adapters. For an accurate and reliable prediction, the accurate retrieval of the adapters is a prerequisite. In order to assess the accuracy of the adapter retrieval on the classification tasks, we conducted the following three experiments. We first computed the rate of mis-retrieval of the adapters given the input image-text prompt pairs per task. Then, we repeated the same experiment in the absence of the task or organ information. For example, the breast cancer sub-typing task initially has the text prompt The cancer sub-type of this breast tissue is, i.e., both organ and task information are available. In the following two experiments, the text prompt changed to this breast tissue is and the cancer sub-type of this tissue is. The former contains the organ information only, and the latter includes the task information only.

Figure 7c depicts the rate of mis-retrieval with varying text prompts. Provided with both organ and task information, CAMP retrieved the correct adapters without failure for the entire classification tasks. Missing either the organ or task information resulted in minimal mis-retrieval rates regardless of the classification tasks. For the organ only, there was a mis-retrieval rate of 0.57% on average, ranging from 0.22% to 1.49%. As for the task only, the mis-retrieval rate varied from 0.00% to 2.79% and averaged 1.43% across the 17 classification tasks. These results indicate that CAMP is able to retrieve the correct adapters even though it is provided with the incomplete text prompt, demonstrating the validity of the key optimization.

Furthermore, we investigated the effect of the incorrect retrieval of the adapters by comparing the predicted text outputs in the three experiments. It is remarkable that CAMP was, in general, able to generate the correct or semantically related text outputs even though the adapters from different tasks were employed (Fig. 8). For example, given a well-differentiated cancer pathology image for colorectal cancer grading, CAMP retrieved the adapters from colorectal tissue sub-typing and gastric cancer grading for the text prompt with the organ only and the task only, respectively, and the corresponding text outputs were tumor and tubular well-differentiated cancer, respectively. Similarly, for the grade 3 cancer pathology image in liver cancer grading, the adapters from liver cancer grading (organ only) and kidney cancer grading (task only) were retrieved. Using these adapters, CAMP generated grade 3 cancer and grade 4 cancer for the organ-only and task-only text prompts, respectively. As for the normal pathology images from colorectal tissue sub-typing and lung cancer detection, CAMP produced either normal or benign images regardless of the text prompts. Overall, CAMP almost always predicted benign/normal pathology images as benign or normal. Tumor/cancer pathology images were classified as tumor or a similar type of cancer. Hence, CAMP is capable of addressing incomplete information and providing contextually relevant outputs. As CAMP is exposed to more diverse and related tasks (e.g., tissue sub-typing), the quality and relevance of the output would be improved, holding the potential to serve as a robust, unified pathology image classification model.

a Absence of pathology-specific knowledge in the encoder, decoder, and both encoder and decoder for path-level classificationtasks. b Absence of pathology-specific knowledge in the encoder, decoder, and both encoder and decoder for slide-level classificationtasks. c Rate of mis-retrieval with varying text prompts.

CAMP achieves efficiency in both computation and storage

There are numerous classification tasks in computational pathology. The more computational pathology tools we use in the clinics, the more computational resources we need to provide. AI in healthcare, in general, faces critical sustainability issues on computer power, energy, and storage with the increase in the size and complexity of models40. To understand and analyze the potential impact of CAMP and other competitors on the clinics, we examined the efficiency of CAMP and other competitors in terms of the model complexity and the computational and storage requirement, including the number of parameters, Giga floating-point operations per second (GFLOPS), training time and memory consumption, and inference time and memory consumption (Fig. 6c). The training and inference time were estimated in milliseconds per image.

Overall, the traditional classification models (CNN and Transformer models) usually required a less amount of parameters, GFLOPs, time, and memory for both training and inference in comparison to the generative classification models (CAMP, GPC, and GIT-B) (Fig. 6c). This is mainly because the generative classification models consist of two modules, one for encoding and the other for decoding. Comparing the traditional classification models, Transformer models (MaxViT, SwinV2-B, ViT-B, PLIP-V, and CTransPath) were computationally more expensive than CNN models (ConvNeXt-B, EfficientNetV2-S, ResNet50, RegNet, and ResNeXt50). Among the generative classification models, CAMP was shown to be the most efficient model with respect to the number of parameters, GFLOPS, and the time and memory consumption for training and inference. CAMP was also comparable to the recent CNN and Transformer models with respect to the training and inference time and memory consumption.

However, the above measurements are valid as we consider a single task only, which ignores the practical and forthcoming issues in the digital pathology era. The more realistic scenario would involve a great deal of tasks that are entirely or partially conducted or aided by AI-driven tools. To analyze CAMP and other models from this perspective, we investigated the scalability of CAMP and others by measuring the training time and storage memory as the number of datasets (tasks) increases (Fig. 9). Other competitors were grouped into two categories: one includes task-specific models, and the other contains task-agnostic models. The more datasets or tasks we have, the more storage memory the task-specific models require. This is because a new model is needed every time a new dataset or task is given. However, the storage memory that task-agnostic models and CAMP need was shown to be steady since these only use a single model with and without additional, tiny parameters. For the 22 datasets used in this study, CAMP could save up to 85% of the storage memory as compared to the task-specific models, while remaining comparable to task-agnostic models. As for the training time, the training time of task-agnostic models was exponentially increasing, as all datasets were repeatedly used for each task. In contrast, both task-specific models and CAMP showed a gradual increase, reducing the training time by up to 94% compared with task-agnostic models. These observations suggest that CAMP is efficient in both computation time and storage memory, whereas other models (both task-agnostic and task-specific models) are inefficient in at least one of the two aspects.

In order to learn and adapt to a new task, CAMP introduces low-rank adaptation (LoRA), which keeps and freezes the original weight matrices and only learns the amount of the additive adjustments to the weight matrices. LoRA decomposes each of the adjusted weight matrices into two low-dimensional weight matrices with a lower rank and a smaller number of trainable parameters. The traditional methods often adopt fine-tuning approaches that directly adjust the original weight matrices, and thus a new set of weight matrices is needed for each task, leading to a substantial increase in the number of parameters. To investigate the efficiency and effectiveness of LoRA, we trained and tested CAMP on the 17 classification tasks (11 patch-level and 6 slide-level) using the two approaches (LoRA and full fine-tuning). Then, we compared the training time and storage memory between the two approaches. We note that, in LoRA, we only adjusted a small portion of the weight matrices, i.e., the projection matrices for self-attention in the Transformer layers. As for the full fine-tuning, the entire weight matrices in CAMP were independently adjusted per classification task, and thus this can be considered task-specific. The amount of storage memory for the full fine-tuning continuously grows as the number of tasks/datasets increases, while LoRA needs a tiny amount of additional storage memory for a new task. On the examination of the training time and memory, the efficiency of LoRA was evident. On average, LoRA required 382.4 milliseconds and 3.4 GB of memory to process an image during training, which saves 16.7% of training time and 15.0% of training memory as compared to the full fine-tuning (Fig. 9b). This leads to a considerable reduction in power and memory consumption as well as processing time during the development of the classification models, thereby shorting the time for the deployment to the clinics. We note that this experiment is designed to assess the efficiency of CAMP with respect to time and storage requirements and does not involve other classification models used in the patch-level and slide-level classification experiments. The observed gains in computational efficiency should be interpreted within the context of the framework of CAMP, as other task-specific models can be trained using LoRA, which enables parameter-efficient fine-tuning and helps reduce the overall computational cost.

CAMP attends to critical regions

To deepen our understanding of the diagnosis of CAMP, we visualized and interpreted the relative importance of differing regions in the pathology slides using the attention weights of the aggregator. The attention weights represent the relative contribution of the corresponding patches in generating the slide-level embedding. Using the attention weights, we generated the attention heatmaps by converting the attention weights into percentiles, normalizing them, and plotting the normalized scores as color maps using the corresponding patch coordinates. Following ref. 35, we generated fine-grained attention heatmaps by overlapping the regions/patches and averaging the attention scores. The exemplary WSIs and the corresponding heatmaps are depicted in Fig. 10. For each pair of a WSI and a heatmap, we show three highly attended regions and 2–3 patches that receive high and low attention at high magnification.

a–d For each row, the name of the task and the prediction of CAMP are shown. The blue texts are similar to the ground truth, whereas the orange text is different from the label. In the first two columns, a WSI and a generated attention heatmap are shown. The heatmaps represent the contribution of tissue patches to the final prediction. We show three important regions at the bottom of each WSI/heatmap, which are directly related to the diagnosis of the slide, e.g., tumors in breast cancer sub-typing. Additionally, patches with high and low scores are depicted in the last two columns for detailed observation.

Although the supervisory signal/information, i.e., ground truth, was weak in the slide-level classification tasks, CAMP was able to attend to pathologically important regions for diagnosis. In other words, without any pixel- and patch-level annotations, the model identified and used critical regions in the slides for diagnosis. For example, for a grade 4 cancer WSI in prostate cancer grading (Fig. 10a), CAMP clearly attended to malignant tumors, and the highly attended regions showed grade 4 patterns. At high magnification, we observed that CAMP focused on the cribriform pattern of the tumors and ignored loose collagenous stromal tissue. In the case of papillary renal cell carcinoma WSI in renal cell cancer sub-typing (Fig. 10b), CAMP highly focused on the malignant kidney tumors and moderately attended to chronic inflammation and inflammatory areas around the inflamed renal cortical tissue. At the patch level, the glomeruloid growth pattern of the tumor received high attention, while the fibrotic stromal tissue was weakly focused. As for breast metastasis detection (Fig. 10c), all highly attended regions indicated metastases. These regions were surrounded by normal stroma with low attention. Comparing the patches with the high and low attention, we found that the highly attended patches involve malignant regions with solid clusters of tumor cells, whereas the low-attention patches show mature small lymphocytes. In regard to breast cancer sub-typing (Fig. 10d), though CAMP highly highlighted the malignant tumors, the predicted label (ductal carcinoma in situ) was different from the ground truth label (invasive carcinoma). The examination of the highlighted regions provided insight into the wrong classification. Overall, the three regions with high attention showed the pattern of ductal carcinoma in situ. At high magnification, the high-attention patches demonstrated carcinoma with a clinging pattern, whereas loosely fibrotic collagenous stroma was observed in the low-attention patches.

These observations suggest that CAMP, with attention to heatmaps, permits the interpretation and explanation of the classification results without fine-grained annotations. The ability to recognize essential pathology regions, e.g., tumors, is particularly useful for generating pseudo-labels since the annotation process is time-consuming and labor-intensive. However, we note that the specific meanings of the (highlighted) regions may vary depending on the level of attention, type of WSIs and tasks, and other factors. The detailed interpretation of the results still requires a manual inspection by experienced human experts.

Discussion

Computational pathology, powered by advanced AI techniques, has facilitated automated and precise analysis and diagnosis of pathology images. The adoption of computational pathology holds excellent potential for substantially transforming and easing the workflow of conventional pathology. Image classification accounts for a large proportion of pathology tasks. For this reason, a vast amount of research effort in computational pathology has been made to improve the accuracy and reliability of the classification tasks. However, traditional computational pathology approaches do not consider efficiency and scalability with respect to computational costs and resources. In this study, we demonstrated that CAMP is the solution for image classification tasks in pathology that achieves accuracy, reliability, efficiency, and scalability. Most of the previous studies in pathology image classification focused on a specific disease, including a single dataset or, at most, a few datasets. The applicability and adaptability of these methods were independently and individually assessed, i.e., task-specific. Though these models have been widely applied to several tasks in computational pathology and other domains, there has been, to the best of our knowledge, no such study that sought to validate and test over 22 datasets from 17 pathology patch- and slide-level classification tasks. The experimental results in this study showed that the performance of these models considerably varies across different tasks and datasets, questioning the diagnostic accuracy and reliability in the clinics. In addition, CAMP is a versatile framework that can handle both patch- and slide-level classification tasks. The former allows CAMP to be employed for categorizing fine-grained pathological characteristics in the region-of-interest level, whereas the latter facilitates the diagnosis at the coarse-grained slide-level. Moreover, in the previous studies, the efficiency and scalability of these models were not considered in regard to the number of tasks in pathology. With the growing interest and concern in computational resources, these issues need to be taken into account at the developmental stage of computational pathology tools to transform and reshape the current pathology workflow and realize computational pathology in practice. Based upon the classification results and the analyses of the computation time and memory consumption, CAMP exhibited the potential for addressing the current and emerging issues and for improving diagnostic accuracy and reliability in pathology. The results on 22 datasets show that CAMP can improve upon the performance of various foundation models on numerous tasks of pathology image classification. Moreover, these benefits are observed on both patch- and slide-level tasks, outperforming previous works that are specifically designed for the patch- and slide-level tasks. For example, in PCAM (patch-level breast metastasis detection), QUILT-1M29 with linear probing obtained 87.9% Acc, which is substantially lower than CAMP (91.9% Acc); in Colon-2 (patch-level colorectal cancer grading), an F1 of CAMP was 0.756, which is higher than the previous joint learning method6, built based upon a convolutional neural network, obtaining an F1 of 0.729. In the slide-level breast metastases detection (CAMELYON16), CAMP obtained 97.24% Acc, which is superior to Transformer-based models, including 96.89% Acc by BIMIL-GAT41, built based upon a Transformer and a graph attention network, and 88.37% Acc by TransMIL42, a Transformer-based MIL approach. In the slide-level breast invasive carcinoma sub-typing, CAMP attained 50.4% Acc for BRACS-7, which outperforms the Transformer model with an efficient long sequence modeling (MambaMIL)43, achieving 49.8% Acc. In the slide-level prostate cancer grading, WholeSIGHT44, a graph-based weakly supervised method, obtained 0.679 F1, which is substantially inferior to CAMP by 0.114 F1. This study has several limitations. First, although CAMP is able to adapt to a new task in an efficient and effective fashion, it is not designed to adapt to a new task without annotated examples, i.e., zero-shot learning. Previous models, such as PLIP, were shown to be capable of conducting zero-shot image classification; however, one needs to provide the appropriate prompts, and the performance is not only sub-optimal compared to other learning paradigms but also dependent on the quality of prompts45, thereby reducing the chance of routine use in the clinics. Second, CAMP shares the existing common knowledge but independently and individually learns the task-specific knowledge for the downstream classification tasks. The knowledge learned from the downstream tasks is not shared among the other tasks or used to advance the common knowledge. Ensemble or federated learning approaches could be explored to aggregate the task-specific knowledge and to update the common knowledge without loss of generality. Our future work will investigate the mechanism that can harmonize the existing common knowledge and the new knowledge from various downstream tasks. Third, CAMP was applied to 17 classification tasks on both patch- and slide-level, of which 3 tasks included external, independent test datasets. It is generally accepted that the performance could vary on such test datasets due to several reasons, such as variations in slide preparation and image quality46,47. For the tasks with the independent test datasets, CAMP was still the best-performing model compared to other competitors. For the rest of the classification tasks, an additional validation study needs to be conducted to verify the superiority of CAMP. Fourth, we examined the performance of CAMP using 22 datasets; however, most of the datasets are related to cancer diagnosis. There exist numerous types of classification tasks in computational pathology, such as artifact detection48, survival prediction49,50, and treatment response prediction51,52. CAMP is a generic and general framework that can conduct such classification tasks without modifications in the model design. Fifth, CAMP was inferior to WSI-level foundation models for slide-level classification, revealing the inherent limitations of CAMP and other MIL-based methods for slide-level classification. Nevertheless, CAMP is a lightweight and storage-efficient framework that can be flexibly paired with any visual encoder. In particular, it can leverage WSI-level foundation models as visual encoders, combining their strong slide-level representational capacity with the adaptable, query-driven framework of CAMP. We leave this integration as an avenue for future work. Last, we employed several evaluation metrics in this study. Among them, we primarily used F1 to assess the effectiveness of CAMP against various classification models across multiple benchmarks. While the results demonstrate clear performance trends, we acknowledge that the absence of formal statistical significance testing can limit the interpretability and statistical reliability of our findings. Given the scale and computational cost of our experiments, we consider comprehensive significance testing an important direction for future work. Incorporating such analysis will enable a more rigorous and quantitative comparison between frameworks like CAMP and specialized classification models, ultimately contributing to more robust and reproducible benchmarking practices in computational pathology. With superior performance across extensive and diverse classification tasks, CAMP represents a fundamental transformation in the field of computational pathology for image classification tasks. It moves away from the traditional discriminating methods towards generative techniques, shifts from the category assignment to the production of textual descriptions, and evolves from static learning to a dynamic and continuous learning approach. We anticipate that CAMP can serve as a universal framework for any classification tasks in pathology, paving the way for the fully digitized and computerized practice of pathology.

Method

CAMP

CAMP is a highly efficient and easily adaptable framework for patch- and whole-slide-level image classification tasks in computational pathology. The framework consists of three primary components: (1) a visual encoder \({\mathcal{V}}\), (2) a text decoder \({\mathcal{T}}\), and (3) an adapter storage \({\mathcal{S}}\). \({\mathcal{V}}\) receives a pathology image of interest and extracts an embedding vector with meaningful information for classification. \({\mathcal{T}}\) is to generate a class label as a text, such as lymphocyte and invasive carcinoma. It obtains two inputs: visual input and text input. The visual input is an embedding vector from a pathology image, while the text input is a task-specific prompt that instructs the decoder to generate the relevant and proper prediction. \({\mathcal{S}}\) stores a set of adapters that learn the task-specific representation in a resource- and computation-efficient manner. The overall architecture of the patch-level and slide-level CAMP is illustrated in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2, respectively.

For efficient and effective image classification, CAMP utilizes two types of knowledge: common knowledge and task-specific knowledge. The common knowledge is suitable for various tasks and is shared across different tasks. By contrast, the task-specific counterpart is utilized for a particular task, which is used in addition to the common knowledge to achieve a specialized capability for each classification task. In CAMP, the common knowledge is stored in \({\mathcal{V}}\) and \({\mathcal{T}}\), whereas task-specific knowledge is managed by \({\mathcal{S}}\). The common knowledge is preserved by freezing corresponding modules, while the adapters for the task-specific knowledge are trainable.

Visual encoder

The role of the visual encoder \({\mathcal{V}}\) is to extract informative features in the form of an embedding vector, given a pathology image. Any arbitrary CNN or Transformer-based models can be adopted and used as \({\mathcal{V}}\). Among various models, we consider four Transformer-based models, including CTransPath23, Phikon30, UNI28, and Virchow233, that are trained on a large number of pathology images in a self-supervised manner and shown to be effective in analyzing pathology images. CTransPath is based on a 28M parameter SwinTransformer-Tiny53 with a patch partition layer replaced by a CNN. It was trained via a MoCoV354 contrastive learning framework with diverse positive pairs sampled from different histopathology patches. The pre-training data includes about 15 million image patches from 32 thousand WSIs curated from TCGA (www.cancer.gov/tcga) and PAIP. Phikon is an 86M parameter ViT-Base55 that is pre-trained on approximately 6 thousand TCGA WSIs. The pre-training procedure is based on the iBOT56 contrastive learning framework with 43 million extracted patches. UNI is built on a 307M parameter ViT-Large55 on the in-house dataset Mass-100K with approximately 100 thousand WSIs. ~100 million tiles are extracted for pre-training with the DINOv257 contrastive objective. Virchow2 is built on a 632M parameter ViT-H33. It was pre-trained using DINOv2 contrastive objective on 1.7 billion image tiles from 3.1M WSIs, spanning 5×, 10×, 20×, and 40× magnifications.

Text decoder

The second module in CAMP is text encoder. The text decoder \({\mathcal{T}}\) is responsible for pathology image classification in a generative fashion, given an image input and text input. The image input is an embedding e processed by \({\mathcal{V}}\), which is adjusted by \({\mathcal{S}}\). The text input is a text prompt, such as “the cancer grade of this prostate tissue is", used to guide \({\mathcal{T}}\) to generate a suitable prediction. This text prompt is converted by a tokenizer into tokens with the same dimension as the visual embedding e. These two inputs are then concatenated to form a final sequence. Given this sequence, \({\mathcal{T}}\) generates a class label in the form of a natural language term, such as well-differentiated or poorly differentiated. The generation process is auto-regressive, i.e., \({\mathcal{T}}\) sequentially produces a new token based on previous tokens. Similar to the visual encoder, we also employ the text decoder pre-trained on pathology datasets to take advantage of rich in-domain knowledge. Although the generated text prediction in CAMP is shorter than other language tasks, such as image captioning or visual-question answering, the prediction contains specialized pathological words, e.g., carcinoma or lymphocyte, that are not exposed to general-domain language models. We employ 86M parameter PLIP27 as the textual decoder \({\mathcal{T}}\), containing a stack of 12 Transformer encoder layers. PLIP was trained using OpenPath, a large-scale collection of approximately 200 million pathology image-text pairs curated from medical Twitter and other public sources.

Adapter storage

Both \({\mathcal{V}}\) and \({\mathcal{T}}\) are equipped with common knowledge in pathology acquired from a large collection of pathology data. Though such common knowledge can be utilized for various downstream tasks, one still needs to adapt to each task to further improve the performance. In other words, one needs to learn task-specific knowledge per downstream task. Since there exist numerous downstream tasks, the adaptation process to each task should not interfere with other tasks, and task-specific knowledge should not revise the common knowledge. To this end, we design a dedicated component called adapter storage \({\mathcal{S}}\) that allows us to learn task-specific knowledge. We construct \({\mathcal{S}}\) as a dictionary with task-specific key-value pairs. Each classification task has a unique \(key\,{\mathcal{K}}\), represented as a trainable embedding vector. Each \({\mathcal{K}}\) is associated with a value comprising a set of adapters to tune the classification model to each downstream task. These adapters facilitate easy adaptation to a particular downstream task with the corresponding task-specific knowledge while preserving the common knowledge of \({\mathcal{V}}\) and \({\mathcal{T}}\). Hence, this decouples the optimization procedure of \({\mathcal{V}}\) and \({\mathcal{T}}\) from the adaptation procedure per task, and thus it prevents catastrophic forgetting (overwriting common knowledge with task-specific knowledge), allowing CAMP to effectively learn and conduct a variety of classification tasks. The composition of the adapters differs between the patch-level and slide-level classifications.

For patch-level classification, the adapter set includes a visual encoder adapter \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{E}\), a text decoder adapter \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{D}\), and a projector adapter \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{P}\). \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{E}\) and \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{D}\) are added to the original weights of \({\mathcal{V}}\) and \({\mathcal{T}}\) via low-rank adaptation (LoRA)58. \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{P}\) serves as a connector that matches the embedding space of \({\mathcal{V}}\) with that of \({\mathcal{T}}\), ensuring the seamless alignment between \({\mathcal{V}}\) and \({\mathcal{T}}\). We build \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{P}\) using an efficient multiple-layered perceptron with four fully-connected layers.

For slide-level classification, the adapter set comprises an aggregator adapter \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{A}\), a text decoder adapter \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{D}\), and a projector adapter \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{P}\). For visual embedding, we utilize \({\mathcal{V}}\) only, which is fixed during the adaptation procedure following recent multiple-instance learning (MIL) frameworks59. \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{A}\) is a parametric aggregator to combine patch embeddings into a single slide embedding in a trainable manner. \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{D}\) and \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{P}\) are the same as in the patch-level classification.

To retrieve a suitable adapter set for a given classification task, we devise a straightforward optimization and query generation mechanism. For each pair of an input image and text prompt, we generate a query by concatenating a visual embedding (from the visual encoder) and a textual embedding (from the text decoder). During training, the queries are employed to optimize \({\mathcal{K}}\) under two constraints. First, \({\mathcal{K}}\) should be similar to the query of the same classification task. Second, \({\mathcal{K}}\) should be far away from \({\mathcal{K}}\) of other tasks. The optimization of \({\mathcal{K}}\) is accomplished with a designated loss function \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\mathcal{K}}}\), which is described in the section CAMP training. In conclusion, the query is compared with all keys in the adapter storage to retrieve the most suitable value, i.e., the most suitable adapters for the classification task of interest.

Aggregator

WSI classification is often formulated as a multiple-instance learning (MIL) problem59, a weakly supervised learning problem in which an aggregator is used to obtain a slide embedding from several patch embeddings. Following this, we employ the adapting aggregator \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{A}\) to generate a slide-level representation for WSI classification. We adopt four parametric aggregators from state-of-the-art MIL frameworks, including AB-MIL34, CLAM-MB35, TransMIL42, and IB-MIL36. AB-MIL uses basic linear layers to predict attention scores for patch embeddings, uses these attention scores to compute the weighted combination of the embeddings, and generates a slide-level representation. CLAM-MB employs a multiple-branch attention aggregator where each branch is responsible for a classification class. It also learns an auxiliary classifier to distinguish features between strongly and weakly attended patches. IB-MIL utilizes a structured causal aggregator that conducts predictions at the bag level, mitigating confounders between bags and labels, and aims to uncover causal relationships and neutralize their influence through backdoor adjustments. TransMIL adopts a Transformer-based aggregator with a dedicated position encoding component called PPEG, which enables it to capture both morphological and spatial information of WSIs.

Low-rank adaptation

We adopt LoRA58 to adjust the weights of CAMP so as to conduct task-specific classification in an efficient and effective manner. Traditional fine-tuning methods adjust the entire weight matrix as follows Wnew = W + δW where \(W\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d\times k}\) is the weight matrix and \(\delta W\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d\times k}\) represents the amount of adjustment. Assuming that models have a low intrinsic dimension, LoRA decomposes the (large) weight matrix into smaller matrices as follows Wnew = W + δW = W + A × B where \(A\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{d\times r}\) and \(B\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{r\times k}\) are the low dimension weight matrices that approximate δW and r ≪ min(d, k). LoRA can be utilized for any weight matrices in a model; however, we only apply LoRA to the projection matrices of the self-attention mechanism in the Transformer layers. We adjust the three matrices Wq, Wk, and Wv that are used to calculate the query, key, and value in the attention mechanism, respectively. We note that the query, key, and value differ from those in the adapter storage. For the rest of the paper, the query, key, and value are referred to as a component in the adapter storage.

CAMP training

During training, we optimize the weights of key-value pairs in the adapter storage \({\mathcal{S}}\) by employing two loss functions \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\mathcal{K}}}\) and \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\) where \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\mathcal{K}}}\) is the loss for the key optimization and \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\) is the loss for the optimization of the adapters (\({{\mathcal{S}}}_{E}\), \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{A}\), \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{P}\), and \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{D}\)). The detailed illustration is shown in Fig. 1b, Fig. 2b, and Algorithm 1. \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\mathcal{K}}}\) tries to pull the key \({\mathcal{K}}\) of the current task closer to the queries of the image-text prompt inputs (to learn the characteristic of the current task), while pushing it away from that of previous tasks (to clearly distinguish among classification tasks). The former is calculated by the dissimilarity of \({\mathcal{K}}\) and the queries, whereas the latter is the sum of similarity between \({\mathcal{K}}\) and previous keys. In this manner, \({\mathcal{K}}\) captures the task-related embedding in both visual and textual dimensions. We formally define \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\mathcal{K}}}\) as follows:

where Q is the query, M is the number of tasks (M − 1 tasks have already been examined), ∣∣ ∣∣ denotes the Euclidean norm, \({{\mathcal{K}}}^{cur}\) is the key of the current task, and \({\{{{\mathcal{K}}}_{i}^{prev}\}}_{i = 1}^{M-1}\) are the keys of the previous tasks.

Algorithm 1

CAMP training process

\({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\) quantifies the correctness of the text output in comparison to the ground truth text label. It is used to update \({\mathcal{S}}\) only, while preserving the pre-trained weights of \({\mathcal{V}}\) and \({\mathcal{T}}\). Given the token sequence generated by CAMP and the ground truth token sequence, \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\) aims to minimize the difference between the probability distributions of the two token sequences. \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\mathcal{S}}}\) is formulated as follows:

where N is the size of the token sequence and yi and pi are the ground truth and output probability for the ith token, respectively.

CAMP inference

The inference of CAMP can be split into two phases, including the retrieval of task-specific adapters and the generation of the text output. In the first phase, the image input and text prompt input are fed into \({\mathcal{V}}\) and \({\mathcal{T}}\), respectively, and the resultant embedding vectors are concatenated to generate a query. The query is compared against all the keys in the adapter storage, and the most similar key-adaptor pair is retrieved. In the second phase, the retrieved adapters are integrated into the generative classification model to effectively adapt to the inference task. Then, the image input and text prompt input are forwarded to the adapted classification model to produce text tokens in an auto-regressive fashion. Specifically, the input image goes through \({\mathcal{V}}+{{\mathcal{S}}}_{E}\) (patch-level)/\({\mathcal{V}}+{{\mathcal{S}}}_{A}\) (slide-level) and \({{\mathcal{S}}}_{P}\) to produce the image embedding vector. The text prompt input is processed by \({\mathcal{T}}\) to generate the text embedding vector. The two input embedding vectors are then concatenated, forming an input embedding vector, and fed into \({\mathcal{T}}+{{\mathcal{S}}}_{D}\) to generate a new text token. The embedding vector of the new text token is concatenated with the input embedding vector and is used to generate the next text token. This process is repeated until it generates the EOS (end-of-sequence) token. The inference process is demonstrated in Fig. 1c, Fig. 2c, and Algorithm 2.

Algorithm 2

CAMP inference process

Datasets

We employ 22 datasets from 8 organs, including colorectal, gastric, lung, breast, kidney, prostate, bladder, and liver tissues, for pathology image classification (Fig. 3). There exist 17 classification tasks that are categorized into 5 categories, such as cancer grading, metastasis detection, cancer sub-typing, tissue sub-typing, and polyp sub-typing.

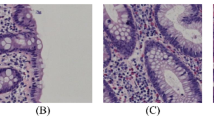

Colorectal cancer grading: Two public datasets (Colon-1 and Colon-2) are collected from ref. 6. Colon-1 contains 9857 patch images obtained from 3 WSIs and 6 tissue microarrays (TMAs), scanning at 40× magnification by an Aperio digital slide scanner (Leica Biosystems). Colon-2 has 110,170 patch images derived from 45 WSIs, digitized at 40× magnification using a NanoZoomer digital slide scanner (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K). Colon-1 is split into training (7027), validation (1242), and test set (1588). Colon-2 is utilized as an independent test set. Each patch image has a spatial size of 512 × 512 pixels and is assigned a class label, including benign, well-differentiated cancer, moderately differentiated cancer, and poorly differentiated cancer. We use "The cancer grade of this colon tissue is” as the text prompt for the colorectal cancer grading task.

Prostate cancer grading: Five public datasets are utilized for prostate cancer grading. The first set (UHU), acquired from the Harvard Dataverse (https://dataverse.harvard.edu/), includes 22,022 image patches of size 750 × 750 extracted from 5 TMAs with 886 tissue cores. These 5 TMAs were digitally scanned at 40× magnification using a NanoZoomer digital slide scanner (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K.) at the University Hospital Zurich. The second dataset (UBC) is the training set of the Gleason 2019 challenge (https://gleason2019.grand-challenge.org/). This dataset comprises 17,066 image patches of size 690 × 690 from 244 prostate tissue cores, and each core was digitally scanned at 40x magnification using an Aperio digital slide scanner (Leica Biosystems). The third set (AGGC60) includes 22,023 image patches of size 512 × 512 obtained from WSIs of prostatectomy and biopsy specimens scanned at 20× magnification using multiple scanners, including Akoya Biosciences, Olympus, Zeiss, Leica, KFBio, and Philips. The last two datasets are obtained from the PANDA challenge61. The fourth dataset, PANDAW61, is the slide-level classification dataset, which includes 10,616 WSIs digitized at 20× magnification using a 3DHistech Pannoramic Flash II 250 scanner. Among them, we utilize 9555 high-quality WSIs following ref. 28. The fifth dataset, PANDAP, is the patch-level classification dataset derived from PANDAW, including 88,199 patch images of size 512 × 512. All the image patches and WSIs are labeled with four classes: benign, grade 3 cancer, grade 4 cancer, and grade 5 cancer. UHU is divided into training (15,303), validation (2482), and test set (4237). PANDAP is split into training (53,479), validation (17,023), and test (17,697) sets. PANDAW is split into training (7647), validation (954), and test (954) sets. UBC and AGCC are adopted as independent test sets for the patch-level classification. The text prompt for this task is "The cancer grade of this prostate tissue is”.

Gastric cancer grading: We utilize a public dataset Gastric7, comprising 98 WSIs of 98 patients, which was digitized at 40× magnification using an Aperio digital slide scanner (Leica Biosystems). A total of 265,066 image patches, each with a spatial size of 512 × 512 pixels, are extracted and annotated with four class labels, including benign, tubular well-differentiated cancer, tubular moderately differentiated cancer, and tubular poorly differentiated cancer. The entire dataset is partitioned into a training (233,898), a validation (15,381), and a test set (15,787). The text prompt for this task is "The cancer grade of this gastric tissue is”.

Bladder cancer grading: A public bladder dataset Bladder62, comprising 913 WSIs that are scanned at 40× magnification, is employed for bladder cancer grading. This consists of 58,539 patch images of size 1024 × 1024 that are extracted and split into a training (26,450), validation (12,912), and testing set (19,177). The patch images are categorized into 3 classes: normal, low-grade cancer, and high-grade cancer. "The cancer grade of this bladder tissue is” is used for the text prompt for bladder cancer grading.

Liver cancer grading: A public dataset for liver cancer grading is collected from ref. 63, denoted as KMC-Liver. This comprises 3109 patch images of size 214 × 214 pixels that were initially obtained from 257 WSIs. The images are categorized into four sub-types of liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) tumors: benign, grade 1 cancer, grade 2 cancer, and grade 3 cancer. The entire dataset is utilized for training (2549), validation (280), and testing (280) with "The cancer grade of this liver tissue is” as the text prompt.

Kidney cancer grading: We collect a kidney cancer grading dataset (KMC-Kidney) from ref. 64, comprising 4077 patch images of size 224 × 224 pixels. The patch images were initially obtained from surgical biopsies of kidney tissues. Each image is classified into five categories: benign, grade 1 cancer, grade 2 cancer, grade 3 cancer, and grade 4 cancer. The entire dataset is divided into training (3432), validation (503), and test set (142). The text prompt for kidney cancer grading is "The cancer grade of this kidney tissue is”.

Colorectal tissue sub-typing: We employ four publicly available datasets for colorectal tissue sub-typing. The first dataset, K1965, comprises 100,000 20×-digitized images of size 244 × 224 pixels from 9 tissue classes, whereas the second dataset, K1666, consists of 5000 images sized at 150 × 150 pixels with 8 classes. Following ref. 67, we match the number of classes between K19 and K16 by excluding one class (625 complex stroma images) from K16 and by grouping stroma/muscle and debris/mucus into stroma and debris, respectively, in K19, resulting in 7 classes for both. The 7 classes are adipose, background, debris, lymphocyte, normal, stroma, and tumor. K19 is utilized for training (70,000), validation (15,000), and testing (15,000), whereas K16 is used as an independent test set. Moreover, we utilize HunCRC68 as the third (HunCRCW) and fourth (HunCRCP) datasets. HunCRCW is the slide-level classification dataset with 200 WSIs scanned at 20x magnification that are annotated with 4 classes: negative, non-neoplastic lesion, carcinoma, and adenoma. HunCRCP is the patch-level classification dataset, including 101,398 patch images of size 512 × 512 pixels. The patch images are classified into 9 categories: adenocarcinoma, high-grade dysplasia, low-grade dysplasia, inflammation, tumor necrosis, suspicious for invasion, resection edge, technical artifacts, and normal. Both datasets are divided into training, validation, and test sets, such as 158, 21, and 21 WSIs for HunCRCW and 81,118, 10,140, and 10,140 patch images for HunCRCP, respectively. The prompt for these datasets is "The tissue type of this colon tissue is”.

Colorectal polyp sub-typing: We employ UniToPatho69 for the classification of colorectal polyps. The dataset includes 9536 patch images of size 1812 × 1812 pixels, scanned at 20× magnification. The images are grouped into 6 sub-types: normal, hyperplastic polyp, tubular adenoma with high-grade dysplasia, tubular adenoma with low-grade dysplasia, tubulo-villous adenoma with high-grade dysplasia, and tubulo-villous adenoma with low-grade dysplasia. The training, validation, and test sets include 6329, 560, and 2647 patch images, respectively. The prompt for UniToPatho is "The polyp type of this colon tissue is”.

Kidney cancer sub-typing: We utilize DHMC70 for the 5-class renal cell carcinoma classification, including oncocytoma, chromophobe, clear cell, papillary, and benign. The dataset consists of 563 WSIs, originally scanned by an Aperio AT2 whole-slide scanner at 20× magnification, and is split into training (393), validation (23), and testing (147) sets. The prompt for DHMC is "The sub-type of renal cell carcinoma is”.

Breast cancer sub-typing: We employ two public datasets. The first dataset, BACH, is obtained from the Grand Challenge on Breast Cancer Histology Images71. This dataset comprises 14,258 patch images of size 512 × 512 pixels digitized at 20× magnification. Each image is annotated with one of the following four classes: normal tissue, benign, in situ carcinoma, and invasive carcinoma, which were unanimously determined by two pathologists. We split them into training (8752), validation (2674), and test (2832) sets. We use "The cancer type of this breast tissue is” as the text prompt for this task. We adopt the second dataset, BRACS, from www.bracs.icar.cnr.it for the slide-level breast carcinoma classification. The dataset includes 547 WSIs collected from 189 patients with two different ways of labeling. The coarse sub-typing includes 3 classes: benign tumor, atypical tumor, and malignant tumor, whereas the 7-way fine-grained categories are normal, pathological benign, usual ductal hyperplasia, flat epithelial atypia, usual ductal hyperplasia, ductal carcinoma in situ, and invasive carcinoma. The dataset is divided into training (395), validation (65), and testing (87) sets. The text prompts are "The sub-type of this breast cancer is” for the coarse-grained task and "The fine-grained sub-type of this breast cancer is” for the fine-grained task.

Breast metastasis detection: We utilize two public datasets (one for slide-level and the other for patch-level) derived from the Camelyon16 Challenge72, which are labeled with normal and tumor. The slide dataset, denoted as CAMELYON16, comprises 400 WSIs, digitized at 40× magnification, of sentinel lymph node sections. These slides are split into training (243), validation (27), and test (129) sets, excluding one mislabeled slide. The patch dataset, called PCam, has 327,680 patch images of size 96 × 96 pixels. The entire images are split into training (262,144), validation (32,768), and test (32,768) sets. The text prompt used for both datasets is "The metastasis screening of this breast tissue is".

Lung cancer detection: We use WSSS4LUAD73 for the lung cancer detection task. This dataset consists of 97 WSIs digitized at 10× magnification. Initially, the dataset includes pixel-level semantic segmentation masks for tumor epithelial tissue, tumor-associated stroma tissue, and normal tissue. Using these masks, 13,526 patch images of size 224 × 224 pixels are extracted. These images are divided into training (10,091), validation (1372), and test set (2063). "The status of this lung tissue is" is the text prompt for this task.

Experimental settings