Abstract

Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying cognitive resilience in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is essential for identifying novel drivers of preserved cognitive function despite neuropathology. Rather than directly searching for individual genetic factors, we focus on latent factors and deep learning modeling as a systems-level approach to capture coordinated transcriptomic patterns and address the problem of missing heritability. We developed a conditional-gaussian mixture variational autoencoder (C-GMVAE) that integrates single-cell transcriptomic data with behavioral phenotypes from a genetically diverse BXD mouse population carrying 5XFAD mutations. This framework learns a structured latent space that captures biologically meaningful variation linked to cognitive resilience. The resulting latent variables are highly heritable and reflect genetically regulated molecular programs. By projecting samples along phenotype-aligned axes in the latent space, we obtain continuous gradients of genetic features associated with AD cognitive resilience. These findings highlight the potential of latent variable approaches not only to model high-dimensional biological data but also to reveal hidden factors driving phenotypic variability in neurodegeneration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by progressive neurodegeneration and cognitive decline1,2, yet there exists considerable heterogeneity in how individuals respond to similar levels of neuropathological burden3,4. Some individuals maintain relatively preserved cognitive function despite significant amyloid and tau pathology, a phenomenon referred to as cognitive resilience5,6,7. Understanding the molecular mechanisms that underlie this resilience offers a promising path toward identifying protective factors and novel therapeutic targets that go beyond traditional amyloid-centric approaches8,9.

Most transcriptomic studies of cognitive resilience in AD have relied on bulk RNA sequencing, which averages gene expression across diverse cell types within a tissue10,11. This approach obscures cell-type-specific signals and masks the heterogeneity of molecular responses across different cellular populations12,13,14. As a result, it can overlook critical resilience-related pathways that are active only in specific cell types or subclasses15,16. To address this, recent efforts have turned to single-cell transcriptomics, which provide the resolution necessary to resolve cell-type-specific mechanisms17,18,19,20. However, many of these studies remain focused on individual molecular markers by evaluating one gene or protein at a time19,21, thereby missing higher-order transcriptional patterns such as coordinated regulatory modules or latent molecular states22,23,24. This reductionist approach contributes to the phenomenon of missing heritability, in which a large portion of phenotypic variation remains unexplained by known genetic or molecular features25,26.

Latent variable modeling provides a promising framework to address these limitations by capturing multivariate and potentially nonlinear structures embedded in high-dimensional transcriptomic data24,27,28,29. Rather than examining genes in isolation, latent variable approaches uncover low-dimensional representations that summarize coordinated gene activity across cells24,30. When applied to transcriptomics data, they can reveal biologically meaningful axes of variation that are not apparent at the level of individual genes nor linear combinations of genes. Importantly, unlike some traditional methods, which aim to analyze groups of genes, such as gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)22, which rely on predefined gene sets or pathways, latent variable models are data-driven and exploratory in nature. This allows them to identify novel, unanticipated patterns of transcriptional coordination that may be missed by methods constrained by predefined biological annotations. These latent features can also serve as endophenotypes, which are intermediate and heritable traits that bridge the gap between molecular variation and complex phenotypic outcomes such as cognitive resilience31,32.

However, extracting meaningful latent structure from transcriptomic data poses several challenges. First, single-cell transcriptomic data are inherently sparse and noisy, complicating the learning of robust and generalizable latent features33,34. Second, the latent space must be able to integrate multiple sources of variation, such as gene expression and behavioral phenotypes, while disentangling biologically relevant signals from technical confounders35. Third, many conventional dimensionality reduction techniques commonly used in transcriptomics, such as principal component analysis (PCA)36, rely on linear assumptions and are inappropriate for capturing complex gene-gene relationships or nonlinear biological trajectories. Nonlinear dimensionality reduction techniques like t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE)37 and uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP)38 reveal local clustering structures but lack an explicit generative framework and often distort global geometry, making them unsuitable for tasks that require continuous interpolation or modeling phenotypic gradients39. These limitations highlight the need for latent modeling approaches that can learn nonlinear yet globally coherent representations and support integrative, interpretable analyses across phenotypic and molecular domains.

Variational autoencoders (VAEs)40 have been widely applied in the analysis of high-dimensional single-cell transcriptomic data, especially for tasks such as cell type identification41,42, clustering43,44,45, and trajectory inference46,47. In contrast to traditional methods like PCA, which assume linearity, VAEs can model complex, nonlinear gene-gene relationships and learn latent dimensions that reflect underlying biological structure48. Unlike t-SNE and UMAP, which are limited to visualization and often distort distances between samples, VAEs provide a generative framework that enables interpolation across the latent space, denoising, and probabilistic interpretation of uncertainty49. These properties make VAEs particularly well-suited for modeling continuous biological processes and for discovering latent trajectories aligned with complex phenotypic traits. Existing applications of VAEs in single-cell studies have largely focused on classification or unsupervised annotation tasks, rather than explicitly modeling phenotypic variation across disease states. Few studies have leveraged VAE-based latent variable modeling to explore phenotype-driven axes of variation learned by combining genetic and behavioral data, such as resilient versus susceptible states in neurodegenerative disease, despite the unique capacity of VAEs to reveal continuous and multivariate structure aligned with behavioral outcomes. This represents a major gap in the current literature and necessitates the use of deep generative models to capture biologically and clinically meaningful dimensions of variation.

The primary goal of our study is to extract hidden factors that underlie cognitive resilience to autosomal dominant human AD mutations in a set of genetically diverse AD-BXD mice. The AD-BXDs are a panel of mice that incorporates the 5XFAD mutation into the genetically diverse BXD genetic reference panel50. In this study, we define cognitive resilience as the ability of 5XFAD transgenic mouse strains to exhibit better behavioral performance at 14 months of age compared to their non-transgenic counterparts of the same genetic background at 6 months, quantified using a cognitive resilience trait. To address the challenges in latent variable modeling, we developed a conditional-Gaussian mixture variational autoencoder (C-GMVAE), a latent variable model designed to integrate single-cell transcriptomic data with behavioral phenotypes while imposing structured organization by cognitive resilience traits on the latent space.

Results

C-GMVAE efficiently learns a stable data representation

Our C-GMVAE model builds upon the basic VAE structure with encoder and decoder layers trained to reconstruct our input data while subject to a central state, called the latent space, that is low-dimensional and follows a probability distribution of a mixture of Gaussians (Fig. 1A)51,52. We chose a Gaussian mixture design rather than the standard single Gaussian to encourage our encoder to regularize the latent space to reflect the heterogeneous structure of cognitive resilience conditions. To further enhance the model’s capacity to disentangle phenotypic variation, we incorporated condition labels derived from a quantitative resilience trait (QRT), which quantifies each sample’s cognitive resilience class based on contextual fear memory (CFM) measured in a contextual fear conditioning (CFC) behavioral experiment. This conditional structure enables the model to learn phenotype-aware latent representations by aligning each sample with a Gaussian component corresponding to its resilience class and encouraging the emergence of distinct yet continuous phenotypic gradients in the latent space53. As a result, the model preserves phenotype-specific and heritable variation, enhances the clustering of biologically similar samples, and enables smooth class-conditional interpolation across the cognitive resilience spectrum.

Our C-GMVAE model integrates multi-modal data as input with single-cell transcriptomic profiles and behavioral outcomes. Specifically, the model was trained using a gene expression count matrix derived from the hippocampus of 14-month AD-BXD mice, with CFM scores at the same age serving as behavioral input. We chose a 10-dimensional space as the internal latent representation of all data. To evaluate model performance, we calculated loss functions including three terms (see Methods for details): (1) reconstruction loss of the reduced gene expression count matrix, (2) reconstruction loss of the CFM score, and (3) Kullback–Leibler (KL) loss. Successful training of our models was indicated by stable convergence and a consistent reduction in loss values across epochs (Fig. 1B). Notably, both the CFM reconstruction loss and the KL loss decreased in tandem, reflecting effective learning of phenotypically relevant structure in the latent space. Overall, the loss convergence demonstrates effective training of the model on combined molecular and behavioral inputs, laying the foundation for downstream assessment of latent space structure and biological relevance.

Learned latent spaces characterizing cognitive resilience

Following model training, we analyzed the 10-dimensional latent space learned by the C-GMVAE to identify axes of variation aligned with cognitive resilience. A two-dimensional t-SNE visualization of the 10-dimensional latent space learned by the C-GMVAE model revealed clear boundaries between different resilience conditions, with samples from the same condition tightly clustered together (Fig. 2A). Consistent with this visual pattern, the latent space exhibited a low Davies Bouldin Index (DBI ≈ 0.5), reflecting high intra-group compactness and distinct separation between groups. This structure suggests that the model captures latent representations that are well-aligned with cognitive resilience phenotypes. In contrast, latent spaces derived from other comparative models that lack key features performed less well. We compared against a standard VAE with a single Gaussian prior, a C-VAE, which added a conditional layer to the standard VAE, and a GMVAE, which has a Gaussian Mixture prior yet no conditional layer. These latent spaces presented as more diffuse in t-SNE visualizations (Supplementary Fig. 2) and yielded higher DBI values, providing reference examples of less compact and less structured latent organization (Supplementary Fig. 3).

A Scatter plot of a 2D t-SNE embedding derived from the 10-dimensional latent space. B Kernel density estimation (KDE) plot of phenotypic extremal projection values computed from the same latent space; Ordering and Separation Degree (OSD) = 0.98. Both plots are colored by resilience condition labels derived from our quantitative resilience trait (QRT).

To further evaluate the phenotypic relevance of the latent space, we calculated a phenotypic extremal projection, which is a single directional axis within the latent space spanning from samples with strong susceptibility to those with strong resilience (see the “Methods” section). We projected all samples onto this axis, effectively overlaying the full dataset along the discovered resilience gradient in the latent space. Analysis of the phenotypic extremal projection revealed a clear and continuous modulation of resilience conditions (from strongly susceptible to strongly resilient) (Fig. 2B). Kernel density estimate (KDE) plots showed that samples from different resilient conditions were distributed in distinct yet marginally overlapping regions along this axis. This distribution reflects the stratification observed in the original QRT scores, supporting the phenotypic relevance of the learned latent representation. To assess the contribution of specific model design elements (conditioning layer and the Gaussian mixture prior), we also compared the sample distribution in this phenotypic extremal projection axis of C-GMVAE to the standard VAE, C-VAE, and GMVAE. In all cases, the resulting phenotypic projections exhibited greater overlap between resilience conditions and reduced separation between the centroids of each condition (Supplementary Fig. 4), suggesting that neither conditioning nor mixture priors alone are sufficient to capture a coherent phenotypic gradient.

To quantify the degree of separation among resilience conditions captured by each model, we computed the pairwise Euclidean distance between the centroids of each condition in the projection space. The C-GMVAE exhibited substantially greater separation compared to the alternative models (Supplementary Fig. 5), supporting its ability to disentangle phenotypic variation along the cognitive resilience spectrum. Importantly, while these conditions represent segments along a continuum rather than fully discrete groups, the smooth yet ordered separation observed here enables refined modeling of resilience as a gradient, rather than an artificial dichotomy, consistent with the continuous nature of cognitive resilience.

In addition, to complement the visual assessment of the phenotypic extremal projection, we designed a quantitative metric, termed the ordering and separation degree (OSD), to evaluate how coherently the latent space captures the phenotypic resilience gradient (see the “Methods” section for details). The OSD integrates two aspects of the projection: the monotonic ordering of condition peaks and the separability of adjacent distributions. By construction, the OSD ranges from –1 to +1, where positive values indicate that samples from higher resilience bins are consistently shifted along the projection relative to lower bins (reflecting a correctly ordered and well-separated gradient), values near zero denote weak or inconsistent ordering, and negative values correspond to an inverted relationship. Applying this metric to the C-GMVAE model yielded an OSD of 0.98, substantially higher than that of other VAE architectures (VAE, C-VAE, and GMVAE, all < 0.3; Supplementary Fig. 4), confirming that the latent representation encodes a continuous and phenotypically consistent progression from susceptible to resilient states.

Next, we assessed the association between phenotypic extremal projections and the QRT by computing Pearson correlation coefficients across all cell subclasses. The phenotypic extremal projection demonstrated a strong and statistically significant correlation with the QRT, with subclass-specific Pearson r values ranging from 0.725 to 0.973 (Fig. 3A). As a reference, correlation coefficients below 0.5 or associations with p-values ≥ 0.05 are generally considered weak or non-significant in this context and were occasionally observed in alternative VAE model architecture (Fig. 3A, B). The consistently high correlations observed between the C-GMVAE-derived phenotypic extremal projections and the QRT suggest that the model captures biologically meaningful variation aligned with cognitive resilience across cell types. Notably, this resilience spectrum emerges even though cell-type information was not provided during training. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, the distribution of phenotypic extremal projection values within each cell subclass mirrors the subclass-specific QRT distribution, indicating that the latent space regularization encourages phenotype-relevant structure to form independently within diverse cellular contexts. This highlights the model’s ability to disentangle resilience-associated variation in a cell type-agnostic yet biologically coherent manner.

A Line plot showing the correlation coefficients between the phenotypic extremal projection and the quantitative resilience trait (QRT), computed separately for each cell subclass. B Box plot comparing the distribution of correlation coefficients across different model architectures, computed separately for each cell subclass.

To assess whether these latent variables captured more variance in cognitive resilience than traditional dimensionality reduction techniques, we performed linear regression using features derived from PCA, t-SNE, UMAP, and our C-GMVAE model, with the QRT as the response variable. Analyses were conducted separately for each subclass, and both R² values and adjusted p-values were calculated to quantify the strength and significance of each association. The results were visualized in a dot plot (Fig. 4), where spot color indicates variance explained (R²) and spot size reflects statistical significance. Latent variables from the C-GMVAE model consistently exhibited the highest R² values, often exceeding 0.5 across subclasses, and demonstrated strong statistical significance (adjusted p < 0.05), outperforming all other feature types. Unlike features from traditional methods, even non-linear ones, such as PCA, t-SNE, or UMAP, which either isolate orthogonal axes of variance or prioritize local structure without preserving global relationships, latent variables learned by the C-GMVAE more effectively capture biologically meaningful transcriptomic and behavioral variation associated with cognitive resilience.

For each feature—PC, t-SNE, UMAP, and latent variable (LV) from our C-GMVAE model, linear regression was performed with QRT as the response variable. R² values and adjusted p-values were computed separately for each subclass, with multiple testing corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. Dot color represents the R² value (ranging from 0 to 1), and dot size reflects statistical significance. This visualization highlights both the strength and reliability of each association. Significance levels: ns not significant (adjusted p ≥ 0.05); *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

C-GMVAE demonstrates strong reconstruction capacity

While the loss function convergence (Fig. 1) demonstrated that our C-GMVAE model learned to reconstruct CFM, its reconstruction capacity is further evaluated by visualizing the distribution of reconstructed CFM values across training epochs and comparing them to the original CFM distribution. As shown in Fig. 5, the reconstructed CFM values generated by C-GMVAE increasingly resemble the distribution of the original CFM over the course of training. Critically, in our model, the goal of reconstruction is not to perfectly replicate the original distribution, but to strike a balance between reconstruction accuracy and maintaining a continuous and well-structured latent space for capturing biologically meaningful variation and enabling smooth interpolation across phenotypic states. The C-GMVAE achieves this balance, producing realistic behavioral reconstructions while preserving latent space continuity necessary for downstream phenotypic analysis.

To quantitatively assess the alignment between reconstructed and observed behavioral outcomes, we calculated the Pearson correlation between the reconstructed and original CFM values at selected training epochs. The correlation values remained consistently high throughout training (Fig. 5), further supporting the model’s capacity to accurately reconstruct individual-level behavioral variation. These results demonstrate that the C-GMVAE captures meaningful behavioral signals and successfully integrates them into the latent representation.

For context, we also examined the reconstructed CFM distributions generated by the VAE models with different configurations (Supplementary Fig. 6). These models served as illustrative examples in which reconstructed values deviated noticeably from the original CFM distribution with lower correlation values (Supplementary Fig. 7). These findings suggest that both conditioning on behavioral phenotypes and enforcing a structured prior are essential for preserving accurate reconstruction in the decoder.

Latent variables exhibit high heritability

To evaluate the biological relevance of the C-GMVAE latent space, we estimated the broad-sense heritability (H²) of each latent variable as well as the phenotypic extremal projection derived from the 10-dimensional representation. Heritability was calculated using a linear mixed model with strain identity as a random effect, capturing the proportion of variance attributable to genetic background (see Methods). The C-GMVAE produced a latent space characterized by consistently high heritability, with individual latent variables exhibiting H² values ranging from 0.946 to 0.963 (Fig. 6). The phenotypic extremal projection also demonstrated a substantial heritability estimate (H² = 0.964), indicating that the resilience-relevant variation embedded in the latent space is strongly shaped by inherited transcriptomic and behavioral patterns.

To contextualize these findings, we applied the same heritability estimation procedure to latent spaces derived from other VAE architectures, including the standard VAE, C-VAE, and GMVAE. These alternative models yielded markedly lower heritability across most latent dimensions (typically below 0.2), suggesting that the combination of conditional inputs and a Gaussian mixture prior in the C-GMVAE is critical for capturing genetically structured molecular variation (Fig. 6). This result implies that using either conditioning or a Gaussian mixture prior alone is insufficient to produce a heritable latent structure. It is the joint contribution of both components that enables the model to disentangle and preserve genetically driven transcriptomic signals.

Latent space interpolation reflects continuous resilience trajectories

Part of the power of generative models like VAEs is their ability to produce new samples from the latent space via the trained decoder layer. The space between where experimental data lies can be sampled from and used to generate realistic data, effectively interpolating between observations in a potentially highly nonlinear manner. To thus examine trajectories of how genetic features change across the spectrum of resiliency, we developed a density-guided interpolation framework leveraging kernel density estimation (KDE) and local label estimation. We specifically examined continuous trajectories between extreme phenotypic conditions—from strong susceptible to strong resilient states as indicated by the decoded CFM scores.

For each such trajectory, we optimized a latent space path under density regularization to maintain locally nearby existing data in the latent space with the added constraint of decoding continuous CFM values (see the “Methods” section). Our C-GMVAE model demonstrates successful continuity of CFM decoding (Fig. 7), with smooth CFM transitions that reflect a continuous transition from data associated with cognitive susceptibility to those associated with cognitive resilience or the reverse. As the latent space is fully generative, we also decoded latent genetic features along these optimized paths to identify which sets of latent factors are most strongly co-modulated with cognitive outcomes. From these latent factors, we then reconstructed gene expression values across all genes and considered only genes highly connected to the top latent factors. Individual genes show different trends across the trajectory (e.g., Acadm increases expression from susceptible to resilient locations), but their collective pattern is what the C-GMVAE identifies as a novel latent factor that is potentially driving cognitive resilience.

A Trajectories in latent space decoded into CFM values across multiple trajectories, both forward (moving from susceptible to resilient locations, solid lines) and backward (from resilient to susceptible, dashed lines). B Normalized expression of the top latent genetic factor strongly correlated with CFM (|r| = 0.948), shown for all forward and backward traversals of the latent space (black line denotes average trajectory). C Top highly weighted genes (normalized expression) along the average trajectory in (B) yield trends with decoded CFM as a function of step through the latent space.

Together, these analyses outline a clear conceptual workflow for using latent variable models like the C-GMVAE to progress from discovery to mechanism. The process begins with training a model that learns a structured latent space aligned with phenotypic outcomes, followed by confirming that individual latent dimensions and phenotypic projections are heritable and thus genetically grounded. Mechanistic hypotheses can then be derived by examining the most significant molecular features along latent traversals or phenotypic axes, such as the trajectory shown in Fig. 7, where coordinated shifts in the expression of multiple genes, including Acadm, Nat10, and others, reflect systematic transcriptional changes across the resilience continuum. These analyses generate testable hypotheses regarding gene sets that may underlie heritable variation in resilience. In future work, genome editing, perturbation assays, or other functional validation approaches could be used to experimentally manipulate these candidate genes or their networks to test their causal roles in cognitive resilience. This stepwise framework demonstrates how deep generative models can bridge statistical representation learning with mechanistic and translational neuroscience.

Discussion

The results of our study demonstrate that the C-GMVAE effectively models the complex and heterogeneous landscape of cognitive resilience in AD-BXD mice by integrating behavioral and transcriptomic data. The model’s architecture, which leverages both a mixture of Gaussians and a conditionally informed latent space, proved especially powerful in capturing biologically and phenotypically meaningful structure in the data. The convergence of loss functions, particularly the KL divergence and CFM reconstruction losses, indicates that the C-GMVAE learns a stable and interpretable latent representation that reflects underlying behavioral variability.

Although the C-GMVAE is a deep learning framework with greater architectural complexity than traditional dimensionality reduction methods, this complexity is warranted for modeling the nonlinear and multimodal structure of this biological data. Simpler linear models are limited in capturing hierarchical and conditional dependencies among molecular and phenotypic features. The conditional and probabilistic design of the C-GMVAE enables it to represent these dependencies more faithfully, yielding latent dimensions that generalize across cell types and align with genetically driven resilience. These design choices were made to enhance interpretability and ensure that model outputs reflect meaningful biological mechanisms.

Compared with the established methods included in our benchmarking analyses, such as PCA, t-SNE, UMAP, and baseline VAE variants (VAE, C-VAE, GMVAE), the C-GMVAE differs in both objective and modeling scope. Traditional linear and nonlinear approaches capture variance or local structure in the data but do not explicitly model conditional relationships between molecular features and behavioral outcomes. The C-GMVAE’s conditional and mixture-based architecture overcomes this limitation by learning latent dimensions that directly align with phenotypic variation, thereby linking molecular patterns to cognitive resilience.

A key strength of the model lies in its ability to generate a novel phenotypic extremal projection from the latent space that exhibits strong correlation with the QRT across multiple cell subclasses. This cross-cell-type consistency suggests that the learned latent features are not only statistically robust but also biologically conserved, enabling insight into shared molecular signatures of cognitive resilience. To further assess the strength of latent variables as endophenotypes, we performed linear regression analyses to compare the association of latent variables learned by C-GMVAE and traditional methods with the quantitative resilience trait (QRT) across subclasses. Several latent variables exhibited significantly higher R² values than other types of latent variables (e.g., PCs), particularly among features passing the adjusted p-value threshold, indicating that the latent space captures a larger proportion of variance in cognitive resilience. These results underscore the advantage of latent variables in summarizing nonlinear and multivariate patterns that are aligned with cognitive resilience, highlighting their value over traditional dimensionality reduction approaches.

Our learned structured latent space facilitates interpretation and enables downstream analyses such as interpolation, trajectory inference, and heritability estimation. The latter is particularly noteworthy—heritability estimates of individual latent dimensions and the phenotypic projection revealed remarkably high values. This suggests that the latent space effectively captures genetically regulated transcriptomic patterns that are linked to behavioral resilience, thus bridging the gap between genotype and phenotype in a biologically meaningful way. Moreover, the model’s ability to reconstruct individual-level behavioral scores with high fidelity provides strong evidence of its capacity to encode salient phenotypic variation. Notably, the C-GMVAE showed markedly outstanding performance relative to baseline VAE models in this regard, suggesting that both the Gaussian mixture structure and the conditional alignment to resilience classes contribute substantially to reconstruction accuracy.

Finally, our interpolation framework illustrates a novel application of the learned latent space to infer hypothetical molecular trajectories across phenotypic states. The smooth and continuous transitions of decoded CFM values along density-regularized interpolation paths suggest that the model is not merely clustering data but learning a meaningful continuum of resilience. This capacity opens new avenues for exploring potential molecular pathways that mediate transitions from cognitive susceptibility to resilience and for identifying candidate genes or regulatory programs that shape these trajectories.

Collectively, these results position C-GMVAE as a powerful tool for modeling high-dimensional, multimodal biological data and extracting interpretable latent representations that align with both behavioral traits and genetic architecture. The model provides a framework not only for understanding the molecular basis of cognitive resilience but also for generating new hypotheses about how genetic and transcriptional factors drive phenotypic variability in neurodegenerative disease contexts.

Future directions include extending this framework to male AD-BXD mice to investigate sex-specific molecular mechanisms of resilience and to assess how the identified latent dimensions generalize across sexes. Because females show both molecular susceptibility and resilience earlier in disease progression, their inclusion provided a more diverse range of phenotypes for modeling these processes. In addition, the candidate genes identified through mapping trajectories across the latent space represent computational predictions that warrant experimental validation. Follow-up perturbation studies, including gene knockdown or overexpression, functional assays in neuronal systems, and sequencing-based validation approaches, will be critical for confirming their causal roles and translating these findings to human biology.

Methods

Animals

All mice used in this study were group-housed (2–5 per cage) at either the University of Tennessee Health Science Center or The Jackson Laboratory, maintained under a standard 12-h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. Female 5XFAD mice on a C57BL/6 J background, harboring five human familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations, were crossed with males from the genetically diverse BXD recombinant inbred panel derived from C57BL/6J × DBA/2J strains50. The resulting F1 offspring represent recombinant inbred backcross progeny, each carrying a maternally inherited B6-5XFAD allele and a paternally inherited B or D allele from the BXD lineage54. Additionally, F1 populations of AD-B6 and AD-D2 mice were generated by crossing 5XFAD females (C57BL/6J background) with C57BL/6J or DBA/2J males, respectively (Fig. 8A). Only female mice were used in this study. Genotyping to confirm transgene carrier status was performed either in-house at The Jackson Laboratory’s Transgenic Genotyping Services or by Transnetyx (TN, USA). All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) at both institutions and were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Contextual fear conditioning

A total of 92 mice underwent behavioral testing using a standard contextual fear conditioning (CFC) protocol, including training and testing sessions (Fig. 8B)50,55,56. The training session began with a 3-min (180-s) baseline period, followed by four mild foot shocks (1 s duration, 0.9 mA), each spaced approximately 115 ± 20 s apart. Following each shock, a 40-s post-shock (PS) interval was included, during which the proportion of freezing period of the mouse was recorded. Freezing behavior was again recorded as contextual fear memory (CFM) was measured when mice were recalled to the same chamber 24 h later for a 10-min testing session. All animals were tested using this CFC paradigm at either 6 or 14 months of age.

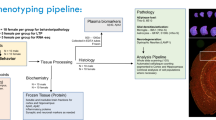

Tissue collection and transcriptomics data acquisition

Following behavioral testing, brain tissue from the hippocampus was harvested from one mouse per strain for RNA extraction (Fig. 8C). Frozen nuclei were isolated and visually assessed using brightfield microscopy. More than 10,000 nuclei per sample were loaded onto a single lane of the 10X Genomics Chromium Controller. Single-nucleus encapsulation, barcoding, and library preparation were conducted using the Chromium Single Cell 3’ Reagent Kits v3 (10X Genomics). The sequencing data were demultiplexed using Illumina’s bcl2fastq software to generate FASTQ files.

Transcriptomics data preprocessing

Base call files were converted to FASTQ files using bcl2fastq (version 2.20.0.422). Reads were aligned to a custom reference genome based on GRCm39 pre-mRNA transcriptome, incorporating 5XFAD mutations to generate sample-level cell count matrices using the Cell Ranger count pipeline with intronic reads included (version 7.0.0, chemistry V3, 10x Genomics). To confirm the genetic integrity of B6 x BXD samples, RNA-strain-match (v.1.0.0)57 assessed alignment of reads to strain-specific SNP data. Read counts in the ddx3y and xist regions verified the assigned sample sex for each sample. Three samples that did not meet the sample integrity criteria were excluded, resulting in a final set of 53 samples included for analysis. Ambient RNA background noise was removed using CellBender (v.0.3.0)58 with a learning rate of 1e-5 across 150 epochs.

All sample processing was done using Seurat (version 5.1.0)59 in R (version 4.4.1). Initial cell-level filtering retained cells with unique molecular identifiers (nUMIs) from 500 to 20,000, and mitochondrial and ribosomal gene content (Rps, Rpl, and pseudogenes) up to 5%. After filtering, each sample was individually normalized using SCTransform followed by dimensionality reduction via PCA. Samples were integrated using Harmony60. Subsequently, the construction of a shared neighbor graph, Louvain community detection clustering, and visualization using UMAP were executed on the integrated data space.

DoubletFinder (version 2.0.3)61 was used to identify and filter doublets starting with a doublet rate estimate of 5%. For each sample, the algorithm was executed twice: initially using parameter sweeps to find optimal parameters for expected doublet counts, and then with adjustments based on homotypic doublet proportions. Clustering was performed at high resolution to determine the proportions of doublets within clusters. A two-stage filtering process was implemented: initially removing individual cells marked as doublets and then filtering out clusters exhibiting over 70% doublet proportions. Nuclei belonging to these high-doublet clusters were flagged and removed from further analysis.

Cell type and subclass annotation

Following doublet removal, cell type annotation was conducted using the MapMyCells (RRID:SCR_024672) from the Allen Brain Institute, which compares input data to high-quality reference datasets. For this analysis, the 10x Whole Mouse Brain (CCN20230722) taxonomy62 was selected, and a hierarchical mapping algorithm was employed. Doublet-filtered data in Seurat format was converted to H5AD format, suitable for MapMyCells, by aligning raw counts with SCT features and incorporating necessary cell metadata and gene annotations.

After cell-type annotation, nuclei were assigned class labels based on hierarchical taxonomy. Initial filtering involved excluding top-level classes with fewer than 10 nuclei. Nuclei were then grouped into specific cell types, including excitatory neurons, inhibitory neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, immune, and vascular. Expected and mixed class markers were defined for each nucleus type based on canonical markers to guide the cleanup process. For each nuclear type, clustering was conducted at high resolution within the integrated data space (Seurat, FindClusters, resolution = 1.5), and the resulting data were visualized in UMAP (Seurat, RunUMAP, dims = 1:30). Iterative removal of clusters with mixed marker signals was performed based on marker-based cluster summaries, ensuring refined, type-specific groupings. The final cleaned dataset was clustered with a resolution of 0.5 to establish the definitive groupings for further analysis.

A custom regional reference file was developed from the Allen Brain Institute’s whole brain taxonomy to establish ground truth and aid in subclass annotations. Raw files across all chemistries for the region of interest were downloaded. Taxonomic annotations, including class, subclass, supertype, and cluster, were then integrated with the expression data. Subsequently, data were filtered to ensure sufficient representation across all classes and subclasses for each chemistry, retaining only datasets where each class contained at least 50 cells. This filtering step led to the exclusion of 10 x Multi chemistry due to insufficient cell counts. The resulting datasets were combined into a single Seurat object. For each cell type, the reference dataset was further refined by filtering subclasses with at least 30 counts, ensuring only valid subclasses were included. Each cell type reference file underwent SCTransform normalization to regress out the effects of library preparation methods, creating a tailored reference for subclass annotation.

To address increased subclass diversity beyond what marker-based methods could resolve, subclass annotation was reinforced through integration with the custom regional reference file. Initial filtering ensured valid subclasses by using count thresholds, retaining only data with sufficient representation. For each cell type, both the reference and query datasets were subsampled to ensure equal representation across all top-level classes. This subsampling facilitated a balanced comparison and parameter optimization for optimal integration settings.

Using the rliger package (version 2.1.0), the subsampled datasets were first used to determine the optimal parameters, k and λ, for UINMF-based alignment63. Subsequently, full datasets were integrated with refined parameters, typically set to k = 30 and a lambda value tailored for each cell type, allowing for robust integration and precise alignment of cell identities. k-nearest neighbors (kNN) was employed to transfer subclass annotations from reference to query samples, leveraging the integration results. Factor loadings obtained through Liger integration allowed for the identification of the nearest reference cells, with subclass annotations assigned based on the predominant class among the top five closest neighbors for each query cell. The predicted subclass annotations underwent validation using predefined subclass markers for each cell type. Marker gene expression patterns were compared across the integrated data space to assess whether each subclass exhibited the expected marker profiles in both the reference and query datasets.

Quantitative resilience trait

To quantify AD cognitive resilience, we leveraged the CFM of aged AD-BXD mice harboring the 5XFAD transgene with that of younger Ntg-BXD mice of the same strain that did not have the transgene. First, we calculated the average CFM score for each AD-BXD strain at 14 months of age (51 mice total, 2–8 mice per strain) and for each corresponding Ntg-BXD strain at 6 months of age (41 mice total, 2–5 mice per strain). We then performed a weighted linear regression of the 14-month CFM score for AD-BXD mice against the 6-month Ntg-BXD strain means (Fig. 9A). This strain-level regression allowed us to estimate residuals that reflect cognitive decline from expected age and genotype-matched baselines64.

A Weighted least squares analysis of all 14-month AD-BXD contextual fear memory (CFM) observations against the strain means of 6-month Ntg CFM. Observations are weighted by \({{n}_{{\rm{BXD}}}}^{-1}\) (where \({n}_{{\rm{BXD}}}\) is the number of mouse samples per BXD strain) to ensure equal weight is given to each BXD strain. B Mean residual was used as QRT, a measure to stratify AD-BXD strains into different resilient conditions. Strains were assigned a number generated by k-means clustering based on their QRT. Cluster numbers from 0 to 3 correspond to the following cognitive resilience conditions: Strong susceptible, Weak susceptible, Weak resilient, and Strong resilient, respectively. This cluster number was subsequently used as a conditioning label in the C-GMVAE model.

In this regression of 14-month CFM scores for 5XFAD mice on the corresponding Ntg-BXD strain means, we observed a statistically significant but modest explanatory power (R² = 0.062, p < 0.05), with a regression slope less than 1 (Fig. 9A). This result suggests that while the 5XFAD transgene generally impairs cognitive function, much of the individual variability in cognitive decline remains unexplained by baseline strain performance alone. We quantified this unexplained variance as “14-month AD-BXD vs. 6-month Ntg-BXD CFM residuals”, which were standardized, resulting in a z-score as the quantitative resilience trait (QRT), representing a continuous measure of cognitive resilience. To stratify strains for conditional modeling, we applied k-means clustering to the QRT values and selected k = 4 as the smallest number of clusters beyond a binary susceptible–resilient split, while maintaining balanced representation across the 12 strains (three strains per group). This choice ensured sufficient biological diversity within each category while avoiding over-fragmentation, resulting in four cognitive resilience conditions: Strong susceptible, Weak susceptible, Weak resilient, and Strong resilient (Fig. 9B).

Conditional–Gaussian mixture variational autoencoders (C-GMVAE)

To model the heterogeneous transcriptomic and behavioral features underlying cognitive resilience, we developed a conditional Gaussian mixture variational autoencoder (C-GMVAE) (Fig. 1A). The architecture builds upon the basic VAE framework, consisting of an encoder and decoder network trained to reconstruct high-dimensional input data through a lower-dimensional latent space constrained by a probabilistic prior. The encoder network compresses the input features through a series of fully connected layers with decreasing dimensionality: 128, 64, and 32 neurons, respectively, before projecting the data into a 10-dimensional latent space (the bottleneck layer). The decoder mirrors this structure, taking the latent representation as input and sequentially expanding it through layers of 32, 64, and 128 neurons, ultimately reconstructing the data back to the original input dimensionality.

The C-GMVAE was trained using multi-modal input data that integrates molecular and behavioral features. Transcriptomic input consisted of a gene expression count matrix with 31,483 genes acquired from the hippocampus of 14-month AD-BXD mice. Due to the high dimensionality and data sparsity in single-cell transcriptomic datasets, we first applied Gaussian random projection65,66 to the original gene expression count matrix before incorporating it with behavioral measurement. This step was designed to improve computational efficiency and reconstruction capability, which are particularly pronounced when working with tens of thousands of gene features in sparse expression matrices. Gaussian random projection works by projecting the data into a lower-dimensional subspace using a random matrix whose elements are drawn from a Gaussian distribution. The minimum number of projected dimensions was determined by the Johnson–Lindenstrauss lemma67, which provides theoretical guarantees that the pairwise distances between data points are preserved with high probability under projection. By applying Gaussian random projection as a preprocessing step, we ensured that essential biological variation was preserved while reducing noise and redundancy. To validate this, we computed pairwise sample distances in both the original and projected spaces and observed a correlation coefficient of ~0.7, indicating a moderate preservation of global structure. This facilitated more stable model convergence and enabled the C-GMVAE to focus on extracting meaningful latent features from a compressed, yet representative, input space.

To incorporate behavioral context, we used CFM scores measured at 14 months of age for each AD-BXD mouse. These continuous behavioral values were concatenated with the random projected features and provided as part of the input vector to the encoder. Prior to concatenation, both the projected gene expression features and the behavioral CFM scores were standardized (z-scored) to ensure comparable numerical ranges and prevent scale-related biases in gradient updates and loss optimization. This normalization follows standard neural network practice for stabilizing training and avoiding feature dominance due to differing variances68 and is consistent with best practices in multimodal learning for balancing heterogeneous inputs69.

Resilience condition labels derived from QRT were used to condition both the encoder and decoder with sampling steps, while aligning each data point with a specific Gaussian component in the latent prior. In our model, we generated priors in the form of a Gaussian mixture model for each latent dimension. For initialization, four distinct values were randomly selected as the centers (means) of the Gaussian components for each dimension. These values were chosen to ensure that the range and pairwise distances between centers were unique across dimensions, introducing variability and encouraging dimension-specific structure in the latent space. Each of the four selected centers was paired with a fixed standard deviation of 2, defining moderately overlapping Gaussian components that remained sufficiently separated to preserve cluster identity. Using these parameters, we generated 512 samples per latent dimension to match the batch size used during model training. The resulting samples formed a mixture distribution where individual components exhibited partial overlap but remained visually and statistically distinguishable, thus supporting the formation of separable and interpretable modes in the latent space. All VAE models were trained with 28,247 single-cell samples representing 41 cell subclasses, spanning five major cell types (excitatory neurons, inhibitory neurons, microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes), across 12 mouse strains.

Loss functions of VAE models

The total loss function applied in VAE models is defined as the sum of all reconstruction losses40 and the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence loss40,70. Specifically, it includes (1) the reconstruction loss of the random projection of the gene expression count matrix, (2) the reconstruction loss of the CFM score, and (3) the KL divergence loss between the approximate posterior and the condition-specific Gaussian mixture prior. This combined objective balances accurate reconstruction of both molecular and behavioral data with regularization of the latent space, guiding the model to learn compressed representations that are both generative and biologically structured. The neural network weights were optimized using the Adam optimizer to minimize the total loss function, enabling efficient backpropagation and stable convergence during training. The model was trained for 15,000 epochs to ensure stable optimization and thorough exploration of the latent space.

The reconstruction loss in our model is composed of two components, each reflecting a distinct aspect of the input data. First, we calculated the reconstruction loss of the random projected count matrix. This loss is computed using the average value of mean squared error (MSE) of all input features (4842 random projection features), which quantifies how accurately the decoder can reconstruct the transcriptomic data from the latent representation71. It ensures that the core transcriptomic features compressed via random projection are preserved during encoding and decoding. Second, we incorporated a reconstruction loss for the CFM score, which was provided alongside the count matrix input during training. The decoder was trained to reconstruct this scalar phenotype value as part of the model’s output, and the corresponding loss was also computed using MSE. We compared reconstruction losses across multiple model configurations, with standard VAE, C-VAE, GMVAE, and our proposed C-GMVAE to evaluate each architecture’s ability to capture both transcriptomic and behavioral structure. These comparisons were performed separately for the matrix loss (Supplementary Fig. 8B) and behavioral reconstruction (CFM loss in Supplementary Fig. 8C). The enhanced performance of C-GMVAE suggests that incorporation of both Gaussian mixture priors and conditional label information enables the model to more accurately reconstruct high-dimensional, multimodal data reflective of cognitive resilience.

In VAE models, the latent space is optimized not only to encode compressed representations of the input data but also to align with a predefined prior distribution. This regularization is achieved through the KL divergence loss, which encourages the approximate posterior distribution learned by the encoder to match the specified prior. Enforcing such prior helps promote more interpretable and disentangled latent representations while also enabling generative capabilities such as sampling, interpolation, and conditional synthesis. We monitored the KL divergence loss throughout model training as a key indicator of successful latent space regularization. A progressive decrease and eventual stabilization of the KL loss across epochs indicated that the encoder was learning to generate posterior distributions that closely matched the predefined priors. Additionally, comparing KL loss across different model configurations (provided insight into how effectively each architecture preserved the structure of the Gaussian mixture, with lower KL divergence reflecting better alignment and more coherent latent representations (Supplementary Fig. 8D). While lower KL loss typically reflects better alignment with the imposed prior and more coherent latent representations, direct comparisons between models using different prior distributions, specifically, a single Gaussian prior in the VAE and C-VAE versus a Gaussian mixture prior in the GMVAE and C-GMVAE, are not strictly equivalent or fully interpretable. Nevertheless, these comparisons offer valuable insight into how each model regularizes the latent space relative to its prior assumptions.

Phenotypic extremal projection

While the 10-dimensional latent space captures rich transcriptomic variation, interpreting or modeling all 10 latent variables simultaneously is challenging due to their complexity and potential correlations. To address this, we developed a phenotypic extremal projection, which is a method that reduces the latent space to a single scalar coordinate aligned with a biologically defined axis of cognitive resilience, ranging from strongly susceptible to strongly resilient.

This projection offers several key advantages. First, it enhances interpretability by providing an intuitive measure of where each sample lies along the cognitive resilience spectrum, as opposed to requiring interpretation of a multidimensional vector. Second, it facilitates comparability across individual samples, mouse strains, or cell types by anchoring them to a shared, biologically grounded coordinate system. Third, by collapsing the multi-dimensional latent space into a single value, the projection reduces model complexity and mitigates the curse of dimensionality, thereby improving statistical power for downstream analyses such as heritability (H²) estimation and cell type-specific correlation analysis. In summary, this approach ensures that the projected values explicitly align with known phenotypic extremes, thereby focusing on variation most relevant to cognitive resilience.

The phenotypic extremal projection is computed through the following steps. First, we identify the centroids of the latent space representations for samples in the strong susceptible condition and the strong resilient condition. These centroids represent the average position of each phenotypic extremal group within the 10-dimensional space. Next, we define a vector referred to as the phenotypic extremal axis that connects these two centroids. This axis captures the primary direction of phenotypic variation relevant to cognitive resilience. Each sample’s 10-dimensional latent representation is then projected onto this axis by calculating the scalar projection, which is the dot product of the sample’s latent vector and the unit vector of the extremal axis. The resulting scalar value represents the sample’s position along the resilience gradient and serves as its phenotypic extremal projection score.

Ordering and separation degree

To quantitatively evaluate the structure of the phenotypic extremal projection, we developed a composite metric termed the ordering and separation degree (OSD), which was applied exclusively to this projection axis. The OSD quantifies how coherently the phenotypic gradient—from the most susceptible to the most resilient—is represented within the latent space. Each cell sample was first projected onto the phenotypic extremal axis, and for each resilience bin \(b\in \{0,\,1,\,2,\,3\}\), corresponding respectively to Strong Susceptible, Weak Susceptible, Weak Resilient, and Strong Resilient conditions, we estimated the distribution of projection values using KDE. The mode (peak location) of each distribution, denoted \(\widehat{{{rn}}_{b}}\), represented the characteristic coordinate of that condition along the resilience gradient. The global monotonic relationship among these conditions was quantified using Spearman’s rank correlation72 between the ordered bin indices and their corresponding KDE peaks:

where Spearman’s \(\rho\) approaching positive 1 indicates a perfectly monotonically increasing order along the resilience gradient, near 0 indicates no consistent ordering, and approaching negative 1 indicates a reversed pattern.

Local separability between adjacent conditions (0 vs. 1, 1 vs. 2, 2 vs. 3) was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), treating the higher bin as the positive class. Each AUC was converted to Somers’ D73 to standardize its range as

where positive values indicate stronger directional separation between neighboring phenotypic states.

The mean adjacent Somers’ D summarized the average pairwise separability:

where n is the total number of resilience bins included in the analysis (here n = 4); n−2 is the upper bound of the summation index, representing the last adjacent bin pair considered when computing the mean Somers’ D.

Finally, the ordering and separation degree was defined as

This composite metric integrates global monotonic ordering with local separability, yielding a single interpretable measure in the range [−1,1], where positive values indicate a correctly ordered and well-separated resilience gradient, values near zero reflect weak or inconsistent ordering, and negative values denote an inverted pattern.

Heritability estimates

To assess the genetic basis of the learned latent variables, we estimated their heritability (H²) using a variance decomposition approach74. Heritability was defined as the proportion of total variance attributable to genetic factors and was calculated using the following equation:

where \({\sigma }_{{\rm{g}}}^{2}\) is genetic variance attributed to genotype or strain; \({\sigma }_{{\rm{e}}}^{2}\) is the residual error term that captures all non-genetic variations, including environmental noise, technical variability, and biological variability within strains (e.g., single-cell data aggregated across diverse cell types).

To estimate these variance components, we employed a linear mixed model (LMM) framework, which enables partitioning of total variance into strain-level (genetic) and residual components75. Specifically, for each latent variable and phenotypic projection, we modeled its value across single cell samples using the following formulation:

where \({z}_{{ij}}\) is the latent variable value for the jth cell in strain \(i\); \(\mu\) is the overall intercept (fixed effect); \({u}_{i}{\mathscr{ \sim }}{\mathcal{N}}(0,\,{\sigma }_{{\rm{g}}}^{2})\) is a random effect associated with strain \(i\), capturing the contribution of genetic background; and \({\epsilon }_{{ij}}{\mathscr{ \sim }}{\mathcal{N}}(0,\,{\sigma }_{{\rm{e}}}^{2})\) is the residual error for each observation which serves to model all non-genetic sources of variation such as environmental influences and intrinsic biological variability within strains (e.g., heterogeneity among cells of the same strain and cell type subclass).

Association between latent variables and cognitive resilience

To evaluate the biological relevance of latent space representations in relation to cognitive resilience, we quantified their association with the QRT scores. Specifically, we performed Pearson’s correlation between the standardized values of the phenotypic extremal projection and the corresponding QRT scores. The resulting p-values were used to assess the statistical significance of each correlation. To investigate the role of cell-type-specific variation, this analysis was conducted separately for each cell subclass, allowing us to examine how different cellular contexts influence the relationship between transcriptomic latent space and resilience phenotypes. To correct multiple hypothesis testing across comparisons, we applied the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure76 to control the false discovery rate (FDR) at a threshold of 0.05.

To further quantify the proportion of variance in QRT captured by the latent variables, we performed linear regression with one latent variable as the predictor and QRT as the response variable. This analysis was conducted independently for each cell subclass. For each regression, we computed the coefficient of determination (R²) to measure the variance explained, along with p-values to assess statistical significance. Multiple comparisons were also corrected using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure to control the FDR at a threshold of 0.05.

Latent space clustering

To assess how well the learned latent space reflected underlying phenotypic structure, we used a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches. Evaluating the structure of the latent space is critical for determining whether the model captures biologically meaningful variation rather than noise or irrelevant features. In the context of phenotypic stratification, a well-organized latent space should separate samples according to meaningful biological or behavioral differences, such as cognitive resilience or disease state. Without such an evaluation, it is unclear whether the latent representation supports downstream tasks such as classification, clustering, or trajectory inference. Therefore, assessing both the visual structure and quantitative separability of conditions in the latent space is essential for validating model interpretability and biological relevance. For qualitative evaluation, we applied t-SNE to project the 10-dimensional latent representations into two dimensions. This nonlinear dimensionality reduction method preserves local relationships between points, allowing for visual inspection of how samples are organized in latent space. We generated t-SNE plots for each model at the final training epoch, with each sample colored by its resilience condition. Well-clustered latent representations are expected to show compact, non-overlapping groups in the t-SNE projection, corresponding to distinct phenotypic categories.

For quantitative evaluation, we calculated the Davies–Bouldin Index (DBI)77 to measure clustering quality at multiple stages of training (epochs 100, 300, 1000, up to 15,000). DBI evaluates the average similarity between each cluster and its most similar neighboring cluster based on within-cluster compactness and between-cluster separation. Lower DBI values indicate better clustering, with more compact and well-separated groups; value below 1 typically suggests that clusters are well-defined and distinct relative to their internal variability. This metric was used to compare clustering performance across different models and to monitor how the latent space structure evolved during training. Among the models tested, lower DBI scores were interpreted as evidence of a more discriminative and biologically meaningful latent space.

Latent space trajectories

We began by identifying representative trajectory endpoints by selecting cells from the bottom and top deciles of the decoder-predicted CFM distribution in latent space. These endpoints were further constrained to differ in their susceptibility class labels, ensuring that interpolations reflected meaningful phenotypic transitions. For each low-to-high CFM pair, we generated continuous trajectories in the 10-dimensional latent space using a density-guided interpolation method. A Gaussian kernel density estimator (KDE) was first fitted to all latent representations to estimate the data manifold. At each step t, a new point was computed via a weighted blend of the vector toward the target and the local log-density gradient:

where \({d}_{{\rm{goal}}}\) is the normalized direction to the endpoint, \({\nabla }_{z}\log p\left({z}_{t}\right)\) encourages the path to remain within regions of high latent density. The trade-off parameter and \(\lambda \in \left[\mathrm{0,1}\right]\) control the influence of local density versus the direct interpolation direction. The step size \(\eta\) is adaptively increased to reach the next sufficiently dense region when the KDE log-density drops sharply between steps to ensure biological plausibility.

The step size \(\eta\) was initialized as the Euclidean distance between the trajectory endpoints divided by the total number of interpolation steps (chosen here as 24) and was adaptively reduced by 10% whenever the proposed next point entered a low-density region where the log-density dropped by more than 0.5 log-units relative to the previous step. The final \(\lambda =0.5\) value was selected empirically after comparison with \(\lambda =0.1\) and \(\lambda =0.9\), as it consistently produced smooth and biologically plausible trajectories (Fig. 7A). These heuristic settings yielded stable, reproducible trajectories across runs and achieved a balance between trajectory smoothness, computational efficiency, and biological interpretability.

To assign interpretable identities along the trajectory, we applied a Dirichlet neighborhood model. At each point, class frequencies of k-nearest neighbors in the latent space were used to compute a Dirichlet distribution over susceptibility labels. The expected label (argmax of the posterior mean) was assigned, and per-step uncertainty was estimated using the entropy of the distribution, allowing us to track label transitions and ambiguity.

Each trajectory point, along with its assigned label, was decoded into two outputs: the reconstructed gene expression vector and a predicted CFM score (Supplementary Fig. 9). Projected gene features were reverse transformed into the original gene space by un-scaling and applying the pseudoinverse of the random projection matrix used during data preprocessing. This enabled full recovery of gene-level trajectories corresponding to modulation along the cognitive resilience axis.

Functional enrichment analysis

To investigate gene-level contributions to behaviorally relevant latent gene features, 10 pairs of trajectory endpoints were selected to represent transitions in both forward (low to high CFM) and backward (high to low CFM) directions. For each of the resulting 20 trajectories, projected gene features and their gene-level trajectories were reconstructed. Among the top 0.1% of high-dimensional genes (ranked by the absolute value of their connection weights to latent gene features), only those associated with latent features showing an absolute Pearson correlation with CFM ≥ 0.65 were retained. From this subset, unique genes were extracted and divided into positively or negatively effective groups based on their directional effect on CFM.

Predicted genes, RIKEN cDNAs, unannotated entries, and duplicates were excluded, and only genes annotated as “protein-coding” according to MyGeneInfo (https://mygene.info/) were retained, ensuring that the final lists included only curated protein-coding genes with either positive or negative effective correlation to CFM. Curated gene lists from all trajectories were further filtered by selecting only those genes present in the intersection of all positive (or all negative) lists across the 20 trajectories, ensuring that downstream analysis focused on genes consistently and robustly associated with CFM in every comparison. The final list for the 20 trajectories considered above contained 256 protein-coding genes. Functional enrichment analysis (over representation analysis) was performed using g:GOSt module of g:Profiler (https://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/gost), mapping the final gene sets to Gene Ontology Biological Process (GO:BP) terms for Mus musculus (Supplementary Fig. 10). Enrichment significance was assessed using g:Profiler’s built-in multiple testing correction method (g:SCS), with a significance threshold of 0.05.

Data availability

All code files developed for this study are available. The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Wong, W. Economic burden of Alzheimer disease and managed care considerations. Am. J. Manag. Care 26, S177–S183 (2020).

Jack, C. R. Jr et al. Revised criteria for diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer’s disease: Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup. Alzheimer’s Dement. 20, 5143–5169 (2024).

Rahimi, J. & Kovacs, G. G. Prevalence of mixed pathologies in the aging brain. Alzheimer's Res. Ther. 6, 82 (2014).

Stern, Y. et al. Whitepaper: Defining and investigating cognitive reserve, brain reserve, and brain maintenance. Alzheimers Dement. 16, 1305–1311 (2020).

Arenaza-Urquijo, E. M. & Vemuri, P. Resistance vs. resilience to Alzheimer disease: clarifying terminology for preclinical studies. Neurology 90, 695–703 (2018).

Negash, S. et al. Cognitive and functional resilience despite molecular evidence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Alzheimer’s Dement.: J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 9, e89–e95 (2013).

Negash, S. et al. Resilient brain aging: characterization of discordance between Alzheimer’s disease pathology and cognition. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 10, 844–851 (2013).

Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia 47, 2015–2028 (2009).

Selkoe, D. J. Alzheimer’s disease is a synaptic failure. Science 298, 789–791 (2002).

Patel, H., Dobson, R. J. B. & Newhouse, S. J. A meta-analysis of Alzheimer’s disease brain transcriptomic data. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 68, 1635–1656 (2019).

Aguzzoli Heberle, B. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of bulk RNAseq studies in human Alzheimer’s disease brain tissue. Alzheimer's Dement.: J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 21, e70025 (2025).

Patel, A. P. et al. Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intratumoral heterogeneity in primary glioblastoma. Science 344, 1396–1401 (2014).

Zeisel, A. et al. Cell types in the mouse cortex and hippocampus revealed by single-cell RNA-seq. Science 347, 1138–1142 (2015).

Tirosh, I. et al. Dissecting the multicellular ecosystem of metastatic melanoma by single-cell RNA-seq. Science 352, 189–196 (2016).

Macosko, E. Z. et al. Highly parallel genome-wide expression profiling of individual cells using nanoliter droplets. Cell 161, 1202–1214 (2015).

Mathys, H. et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 570, 332–337 (2019).

Efthymiou, A. G. & Goate, A. M. Late onset Alzheimer’s disease genetics implicates microglial pathways in disease risk. Mol. Neurodegener. 12, 1–12 (2017).

Olah, M. et al. Single cell RNA sequencing of human microglia uncovers a subset associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun. 11, 6129 (2020).

Brase, L. et al. Single-nucleus RNA-sequencing of autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease and risk variant carriers. Nat. Commun. 14, 2314 (2023).

Telpoukhovskaia, M. A. et al. Conserved cell-type specific signature of resilience to Alzheimer’s disease nominates role for excitatory intratelencephalic cortical neurons. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.12.487877 (2022).

De Vries, L. E. et al. Gene-expression profiling of individuals resilient to Alzheimer’s disease reveals higher expression of genes related to metallothionein and mitochondrial processes and no changes in the unfolded protein response. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 12, 68 (2024).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545–15550 (2005).

Zhang, B. et al. Integrated systems approach identifies genetic nodes and networks in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Cell 153, 707–720 (2013).

Hodgson, L. et al. Supervised latent factor modeling isolates cell-type-specific transcriptomic modules that underlie Alzheimer’s disease progression. Commun. Biol. 7, 591 (2024).

Eichler, E. E. et al. Missing heritability and strategies for finding the underlying causes of complex disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 446–450 (2010).

Matthews, L. J. & Turkheimer, E. Three legs of the missing heritability problem. Stud. Hist. Philos. Sci. 93, 183–191 (2022).

Way, G. P. & Greene, C. S. Extracting a biologically relevant latent space from cancer transcriptomes with variational autoencoders. In Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing 2018: Proc. of the Pacific Symposium 80–91 (eds Altman, R. B. et. al ) (World Scientific, 2018).

Lou, S. et al. Latent-space embedding of expression data identifies gene signatures from sputum samples of asthmatic patients. BMC Bioinforma. 21, 1–13 (2020).

Palla, G. & Ferrero, E. Latent factor modeling of scRNA-seq data uncovers dysregulated pathways in autoimmune disease patients. Iscience 23, 101451 (2020).

Buettner, F., Pratanwanich, N., McCarthy, D. J., Marioni, J. C. & Stegle, O. f-scLVM: scalable and versatile factor analysis for single-cell RNA-seq. Genome Biol. 18, 1–13 (2017).

Dumitrescu, L. et al. Genetic variants and functional pathways associated with resilience to Alzheimer’s disease. Brain: J. Neurol. 143, 2561–2575 (2020).

Wang, Q. et al. Single cell transcriptomes and multiscale networks from persons with and without Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun. 15, 5815 (2024).

Pierson, E. & Yau, C. ZIFA: Dimensionality reduction for zero-inflated single-cell gene expression analysis. Genome Biol. 16, 1–10 (2015).

Eraslan, G., Simon, L. M., Mircea, M., Mueller, N. S. & Theis, F. J. Single-cell RNA-seq denoising using a deep count autoencoder. Nat. Commun. 10, 390 (2019).

Gayoso, A. et al. Joint probabilistic modeling of single-cell multi-omic data with totalVI. Nat. Methods 18, 272–282 (2021).

Sumithra, V. & Surendran, S. A review of various linear and non linear dimensionality reduction techniques. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. 6, 2354–2360 (2015).

Kobak, D. & Berens, P. The art of using t-SNE for single-cell transcriptomics. Nat. Commun. 10, 5416 (2019).

Becht, E. et al. Dimensionality reduction for visualizing single-cell data using UMAP. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 38–44 (2019).

Chari, T. & Pachter, L. The specious art of single-cell genomics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 19, e1011288 (2023).

Kingma, D. P. & Welling, M. Auto-encoding variational Bayes. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6114 (2013).

Wang, D. & Gu, J. VASC: dimension reduction and visualization of single-cell RNA-seq data by deep variational autoencoder. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 16, 320–331 (2018).

Grønbech, C. H. et al. scVAE: variational auto-encoders for single-cell gene expression data. Bioinformatics 36, 4415–4422 (2020).

Tian, T., Zhang, J., Lin, X., Wei, Z. & Hakonarson, H. Model-based deep embedding for constrained clustering analysis of single cell RNA-seq data. Nat. Commun. 12, 1873 (2021).

Xu, J. et al. Graph embedding and Gaussian mixture variational autoencoder network for end-to-end analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing data. Cell Rep. Methods 3, 100382 (2023).

Choi, Y., Li, R. & Quon, G. siVAE: interpretable deep generative models for single-cell transcriptomes. Genome Biol. 24, 29 (2023).

Tran, D. et al. Fast and precise single-cell data analysis using a hierarchical autoencoder. Nat. Commun. 12, 1029 (2021).

Du, J. H., Chen, T., Gao, M. & Wang, J. Joint trajectory inference for single-cell genomics using deep learning with a mixture prior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2316256121 (2024).

Yelmen, B. & Jay, F. An overview of deep generative models in functional and evolutionary genomics. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Data Sci. 6, 173–189 (2023).

Lopez, R., Regier, J., Cole, M. B., Jordan, M. I. & Yosef, N. Deep generative modeling for single-cell transcriptomics. Nat. Methods 15, 1053–1058 (2018).

Neuner, S. M. et al. Harnessing genetic complexity to enhance translatability of Alzheimer’s disease mouse models: a path toward precision medicine. Neuron 101, 399–411.e5 (2019).

Dilokthanakul, N. et al. Deep unsupervised clustering with Gaussian mixture variational autoencoders. arXiv preprint arXiv:1611.02648 (2016).

Saseendran, A., Skubch, K., Falkner, S. & Keuper, M. Shape your space: a Gaussian mixture regularization approach to deterministic autoencoders. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 7319–7332 (2021).

Norlander, E. & Sopasakis, A. Latent space conditioning for improved classification and anomaly detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.10599 (2019).

Peirce, J. L. et al. A new set of BXD recombinant inbred lines from advanced intercross populations in mice. BMC Genet. 5, 1–17 (2004).

Neuner, S. M. et al. TRPC3 channels critically regulate hippocampal excitability and contextual fear memory. Behav. Brain Res. 281, 69–77 (2015).

Neuner, S. M. et al. Systems genetics identifies Hp1bp3 as a novel modulator of cognitive aging. Neurobiol. Aging 46, 58–67 (2016).

Willcox, J. A. L. et al. RNA Strain-Match: a tool for matching single-nucleus, single-cell, or bulk RNA-sequencing alignment data to its corresponding genotype. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.14.548847 (2023).

Fleming, S. J. et al. Unsupervised removal of systematic background noise from droplet-based single-cell experiments using CellBender. Nat. Methods 20, 1323–1335 (2023).

Hao, Y. et al. Dictionary learning for integrative, multimodal and scalable single-cell analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 293–304 (2024).

Korsunsky, I. et al. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with Harmony. Nat. Methods 16, 1289–1296 (2019).

McGinnis, C. S. et al. DoubletFinder: doublet detection in single-cell RNA sequencing data using artificial nearest neighbors. Cell Syst. 8, 329–337.e324 (2019).

Yao, Z. et al. A high-resolution transcriptomic and spatial atlas of cell types in the whole mouse brain. Nature 624, 317–332 (2023).

Kriebel, A. R. & Welch, J. D. UINMF performs mosaic integration of single-cell multi-omic datasets using nonnegative matrix factorization. Nat. Commun. 13, 780 (2022).

Saul, M. C. et al. Hippocampus glutathione S reductase potentially confers genetic resilience to cognitive decline in the AD-BXD mouse population. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.01.09.574219 (2024).

Bingham, E. & Mannila, H. Random projection in dimensionality reduction: applications to image and text data. In Proc. of the seventh ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 245–250 (2001).

Wan, S., Kim, J. & Won, K. J. SHARP: hyperfast and accurate processing of single-cell RNA-seq data via ensemble random projection. Genome Res. 30, 205–213 (2020).