Abstract

This systematic review synthesizes currently available empirical evidence on generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools for drafting responses to patient messages. Across a total of 23 studies identified, GenAI was found to produce empathetic replies with quality comparable to that of responses drafted by human experts, demonstrating its potential to facilitate patient–provider communication and alleviate clinician burnout. Challenges include inconsistent performance, risks to patient safety, and ethical concerns around transparency and oversight. Additionally, utilization of the technology remains limited in real-world settings, and existing evaluation efforts vary greatly in study design and methodological rigor. As this field evolves, there is a critical need to establish robust and standardized evaluation frameworks, develop practical guidelines for disclosure and accountability, and meaningfully engage clinicians, patients, and other stakeholders. This review may provide timely insights into informing future research of GenAI and guiding the responsible integration of this technology into day-to-day clinical work.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patient portals, as an integral part of electronic health records (EHRs), are now available in nearly 90% of health systems in the United States, enhancing patient engagement and transforming patient–provider communication1,2. Through portal messaging, patients can contact their care teams outside of scheduled visits to ask questions, request medication refills, and follow up on lab-test results3,4. Incentivized by the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act5, messaging has become one of the most frequently used patient portal features6. Over the past decade, message volume has grown substantially7,8, with the COVID-19 pandemic further accelerating this surge, driving a 157% increase compared to pre-pandemic levels. This elevated rate of use has persisted since9. While enhanced communication is associated with improved patient care, it has also increased the burden on clinicians. The influx of messages has overwhelmed clinicians’ “in-baskets”—the EHR-based inboxes—resulting in a workload that often extends beyond regular work hours8,10,11,12. This sustained burden has been linked to clinician burnout, job dissatisfaction, and challenges in maintaining work–life balance10,13,14,15,16.

Human, technological, and policy-level strategies have been adopted to address this growing burden. These efforts have included forming designated administrative teams17, refining management workflows2,18, developing artificial intelligence (AI) applications for message triage19,20, and introducing new billing codes for e-visits21,22. Most recently, generative AI (GenAI), particularly generative large language models (LLMs), has emerged as a potential solution for alleviating clinician in-basket overload23. Capable of interpreting complex texts and generating human-like responses, these models have demonstrated the ability to answer medical questions with expert-level knowledge24,25 and to respond to patient forum posts in a more empathetic tone than physicians26,27. With such capability, GenAI offers a novel approach to assist clinicians by creating draft replies to patient messages. Figure 1 illustrates how this technology works in general. The initial patient message is shown on the top left corner, and the AI-generated draft is shown below it. Clinicians can choose to compose the reply by using/modifying the AI-generated draft (top right) or by creating one from scratch (bottom right).

Several large health systems in the United States have begun implementing Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant GenAI tools for this purpose within their EHR systems28,29,30. These early adopters have highlighted GenAI’s potential to generate useful first drafts, reduce clinician exhaustion, and ultimately enable and improve the efficiency of asynchronous care31,32.

Despite encouraging progress, use of GenAI in facilitating clinical communication is still at an early stage, and the existing literature is highly fragmented. Prior reviews on GenAI in medical question-answering have mainly focused on its performance and efficacy in medical exams, clinical decision support, and patient education, rather than on its role in assisting clinicians with replying to patient messages33,34,35. Yet, when applied to emotionally engaged and potentially high-stakes patient–provider communication, GenAI may be associated with distinct ethical and operational concerns such as disclosure and patient consent regarding AI involvement in such interactions36,37. As interest in this application grows, there is no consensus to date on how to evaluate AI-drafted responses or what lessons can be drawn from initial explorations. Current studies vary widely in design, outcome measures, and evaluation methods. Clinical contexts for these studies also differ, spanning various specialties and diverse patient populations, each of which may present nuanced differences in communication practices. The lack of standardization presents challenges for synthesizing findings. These gaps underscore the need to assess the emerging body of evidence, both to guide the development and implementation of GenAI tools and to inform efforts to understand clinician and patient perspectives and preferences regarding AI-assisted communication. As these tools continue to evolve and become more integrated into care delivery, it is essential to ensure that they help reduce clinician burnout without eroding patients’ trust in healthcare providers and systems.

This review addresses these gaps by systematically identifying and synthesizing empirical studies that evaluate GenAI for drafting replies to patient messages through EHR-embedded patient portals. By examining study settings, objectives, designs, outcomes, and key findings, we aimed to provide a timely overview of the current evidence and outline directions for future research. Specifically, this review seeks to answer the following questions:

-

1.

How have GenAI tools been studied for drafting responses to patient portal messages, and what are the study settings, objectives, and designs?

-

2.

In what clinical contexts have these tools been evaluated?

-

3.

Who are the users participating in these evaluations, and what approaches and outcome measures have been used?

-

4.

What early consensus has emerged from the findings?

In answering these questions, we also discuss the challenges and opportunities surfaced by early studies and emphasize ethical considerations that should be prioritized to ensure the responsible use of GenAI in replying to patient messages. Our synthesis offers guidance for future evaluations and implementations of GenAI designed to aid in patient–provider communication, particularly through patient portals.

Results

This section presents our synthesis of current research on the use of GenAI for drafting responses to patient messages. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics and quality assessment results of the included studies, and Table 2 provides an overview of the information extracted from these studies.

Results of literature search and screening

Figure 2 shows the literature search and screening process following the PRISMA flow diagram format. Our search across five databases (ACM Digital Library, IEEE Xplore, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science) resulted in 3980 potentially relevant papers. After removing 2003 duplicates, 1977 articles remained. Screening based on title and abstract further excluded 1284 additional papers, leaving 693 for full-text review. After reviewing the full text of these 693 papers, 23 were deemed to meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria (detailed in the Methods section) and were included in the final review.

Study characteristics

All 23 studies were conducted in the United States and published between 2023 and 2025. The majority of them (n = 16) appeared in medical and informatics journals, including JAMA Network Open, Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, JAMIA Open, and Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Digital Health. The remainder (n = 7) were published in clinical specialty-focused venues, such as Urology Practice, Ophthalmology Science, and Annals of Plastic Surgery. In terms of type of publication, 17 were full-length research articles, while the others consisted of three research letters, one brief communication, one perspective, and one commentary.

Study setting, objective, and design

The included studies evaluated GenAI for drafting replies to patient messages in two settings: live EHR systems (n = 7) and simulated environments (n = 16). Across these settings, studies primarily aimed to evaluate: (1) the content of AI-generated drafts (n = 19); (2) the implementation of GenAI and its impact on clinical efficiency (n = 8); (3) user perceptions, preferences, or experiences (n = 12); and (4) the effects of prompt engineering (n = 5). Many studies addressed more than one objective.

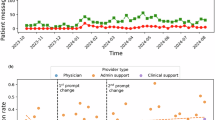

The live EHR system setting refers to real-world clinical environments where GenAI tools are embedded into existing in-basket workflows to generate draft replies for patient messages. All seven studies in this setting evaluated GenAI tools integrated into the Epic EHR (Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, Wisconsin, USA), using OpenAI’s Generative Pre-Trained Transformer (GPT)-4 for response generation31,32,38,39,40,41,42. Several studies explored GenAI implementation and its impact on clinical efficiency and user experience, using measures such as draft utilization31,38,39, extent of edits38, time spent31,32, and clinician burden31,41. Some evaluated user perceptions of AI-drafted content, aiming to understand how clinicians in different roles judged its usefulness39 or how linguistic features were associated with perceived empathy40. Three studies primarily examined prompt engineering. Two iteratively modified prompts in live settings and assessed their effect on draft usability and clinician feedback38,39. The third adopted a structured, human-in-the-loop process to refine prompts in a test environment before deploying them in production, evaluating their impact on provider acceptance and patient satisfaction41. A distinct effort sought to bridge qualitative and quantitative evaluation metrics by proposing a unified framework for assessing LLM performance in healthcare, which was then applied to Epic’s in-basket GenAI feature42. All implementations were conducted as pilot-scale efforts, with most framed as quality improvement projects31,32,39,40,41. The majority employed prospective31,39,41 or quasi-experimental38 designs to evaluate GenAI deployment or prompt modifications in real time. One study used a modified waitlist randomized design to compare outcomes between clinicians with and without access to GenAI drafts32, while another used a cross-sectional survey to capture provider perceptions of draft quality40.

In contrast, studies conducted in the simulated setting evaluated GenAI tools outside of live clinical workflows. These controlled experiments involved generating replies to either de-identified patient messages extracted from the EHR43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53 or hypothetical inquiries modeled on real patient portal communications54,55,56,57,58. The 16 studies conducted in this setting primarily focused on assessing the content quality44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57 and user perceptions43,45,47,48,52,55,58 of AI-drafted replies, using a range of outcome measures detailed later. Many compared GenAI drafts across different models45,46,48,50,54,57 or against human-authored responses43,44,45,46,47,48,50,51,52,55,57,58. Although not embedded in actual workflows, a few studies examined GenAI’s impact on efficiency through subjective ratings and self-reported time for responding or editing drafts50,51,55,57. While GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 were the most frequently used models, some studies evaluated alternative or customized variants. These included GPT-4-based, specialty-specific retrieval-augmented models48,51, fine-tuned versions of LLaMA adapted for clinical use46,54, and institution-developed GPT-powered tools45,48. One study also compared multiple commercial models, including Bard, Claude, and Bing, alongside GPT variants57. To approximate the EHR context, one study included simulated medical records alongside messages when prompting GPT55, while another connected a customized model to the local EHR system to access clinical notes and patient details in support of drafting51. A few studies also incorporated clinician editing processes to examine the human–AI synergistic effect in message drafting55,57 as well as to explore patient preferences regarding the disclosure of AI involvement58. Cross-sectional evaluations or surveys were commonly used to gather user perceptions and assessments, often through randomized and blinded review designs comparing responses by different GenAI models or humans43,45,47,48,50,52,55,57,58. Two studies had distinct objectives and approaches. One developed and fine-tuned a large language model on portal message data and evaluated its performance against baseline GPT and clinician drafts46. The other conducted a retrospective qualitative study focused specifically on GenAI responses to negative patient messages, using thematic analysis to compare content differences between GenAI and clinical care team replies44.

Clinical context, message topic, and participant

GenAI for responding to patient messages was evaluated across various clinical contexts, with primary care, including internal medicine, family medicine, and pediatrics, being the most common setting (n = 10)31,32,38,39,40,41,45,46,52,53. Four studies conducted evaluations across primary care and specialties31,38,39,45, while the remaining studies focused on specific specialty domains, including dermatology47, urology48,49,51, ophthalmology56,57, oncology55, and surgery50,54.

Across the included studies, GenAI was used to generate draft replies for patient messages covering a variety of topics, ranging from administrative inquiries, such as appointment scheduling and medication refills40,46,52,54,58, to medical advice requests related to symptoms, postoperative concerns, and test results49,50,51,56,58. Several studies deliberately varied message seriousness58, complexity54, or level of detail56 to include comprehensive test cases, while others focused solely on clinical questions involving decision-making implications or condition-specific issues41,43,45,47,48,49,50,51,56,57. Some studies curated representative messages to ensure that evaluations covered the most commonly asked topics in patient portals43,46,48,57, while others randomly selected samples from the in-baskets of participating clinicians or from messages sent by a particular patient group40,41,47,53. To ensure fair GenAI evaluation under simulated conditions without integrated data sources, two studies excluded messages that required access to external information40,46. In addition, some studies collected unique message samples to meet specific research objectives. For example, one study evaluated GenAI using a mix of adolescent patient and proxy messages53, while another tested GenAI in emotionally sensitive scenarios using negative patient messages44.

Participants in the studies can be grouped into two high-level categories: clinical and non-clinical experts. Over 90% of the studies (n = 21) involved clinical experts across diverse contexts and roles, including physicians31,38,39,40,41,44,46,47,48,49,50,52,53,54,55,56,57, advanced practice providers31,39,41,50,52, nurses31,38,39,51, medical trainees (medical students, residents, and fellows)50,51, medical assistants39, and clinical pharmacists31. Clinician participants reviewed GenAI draft replies, shared pilot experiences, and either edited AI drafts or created human-authored counterparts for comparative analysis. In contrast, only a few studies engaged non-clinical participants, including patient advisors or laypeople41,43,45,48,58. These participants were typically asked to rate tone, identify the authorship, or share their personal preferences for the given responses, rather than evaluate their clinical quality. While considered laypersons in the medical context, many were active care stakeholders, such as long-term patient advisors with extensive experience using patient portals41, participants recruited from institutional research registries45, or pre-screened volunteers with a clinical condition of interest48. Only two studies focused exclusively on non-clinical perspectives. One surveyed over 1400 members of a patient advisory committee to evaluate preferences for AI-generated responses under varying disclosure conditions58. Another recruited a nationally representative sample of laypersons through a crowdsourcing platform to assess their ability to distinguish between human and AI responses as well as their trust in AI’s advice43.

Evaluation method and outcome measure

All 23 studies incorporated human ratings using Likert scales to assess GenAI responses and their impact. Ten evaluations also calculated basic computational metrics, including text length, utilization rate, and time changes31,32,38,39,40,44,45,50,55,57, while only six studies employed more advanced computational metrics, such as BERTScore and Flesch-Kincaid grade level38,40,42,46,50,51. Among these six, one evaluation framework study intentionally mapped outcome measures to both human ratings and computational metrics to assess their alignment42. Building on the grouping approach used in prior work40, we categorized the common outcome measures examined in these studies into five groups: (1) information quality, (2) communication quality, (3) user perception, experience, and preference, (4) utilization and efficiency, and (5) composite measures.

Information Quality (n = 14). Information quality was consistently evaluated across the studies, encompassing measures such as accuracy40,46,47,48,49,50,52, completeness40,42,48,49,51,54, relevance40,42,51,52,53, and factuality42,53. These measures assess the integrity of the information presented in AI drafts, with accuracy (n = 7) being the most frequently evaluated. While similar or identical terms were often used, they may reflect subtle differences. For instance, some studies evaluated completeness by checking whether drafts lacked essential information needed to answer patients’ questions40,42,49,51,54, while others examined whether responses were comprehensive beyond the minimum required content47,48. Relevance or responsiveness was typically rated based on whether AI responses addressed patients’ concerns40,41,46,52,53. In contrast, studies using computational methods defined relevance by how well AI drafts inferred patient inquiries51 or matched clinician-authored replies42. Two studies treated information quality as a single dimension, without specifying the subcomponents it included45,57.

Communication Quality (n = 14). Communication quality was another important focus, capturing the patient-centered aspects of responses, with empathy (n = 9) being the most commonly measured aspect39,45,46,47,48,50,51,52,57. AI drafts were also evaluated for their tone or style, determining whether their wording and expressions were appropriate for the context of the conversation39,40,41,53. Readability47,52 and related subdimensions, such as clarity42,51, understandability40,49, and brevity (or verbosity)40,42,53, were assessed to ensure that responses could be easily comprehended by patients without semantic confusions, literacy challenges, or distractions. Several studies used computational metrics to assess these aspects, including DiscoScore, lexical diversity, and the Flesch reading ease score40,42,50. Two studies analyzed the overall sentiment of the replies40,51, while another calculated BERT Toxicity to detect any pejorative terms or non-inclusive language42.

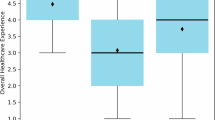

User Perception, Experience, and Preference (n = 12). A variety of measures were used to evaluate user perceptions, experiences, and preferences regarding the use of GenAI to draft replies to patient messages. A recurring focus was the perception of authorship, specifically whether participants could distinguish between AI-generated and human-written replies41,43,48,52. Some studies also asked participants to indicate their preference or rate their satisfaction with each response38,45,47,48,58. Additionally, patients’ trust and perceived level of care from AI-generated replies were assessed43,58. GenAI’s impact on clinician burnout was examined in one study by comparing physician task load and work exhaustion scores in pre- and post-implementation surveys31. In parallel, a few other studies captured clinicians’ perceptions of reduced cognitive load, time savings, and improved efficiency to evaluate the potential benefits of GenAI assistance39,41,55. The net promoter score was also used as a measure of clinicians’ overall support for the GenAI tool31,32,39,41.

Utilization and Efficiency (n = 11). Measures related to utilization and efficiency often focused on basic characteristics or objective metrics of GenAI drafts and their implementation. Length (n = 7) was the most frequently evaluated characteristic32,40,44,45,50,55,57, as it may affect how efficiently clinicians review AI-generated drafts. Time-related measures included the time spent reading messages, as well as writing or editing replies. Some studies measured time changes before and after GenAI implementations31,32, while others compared the completion time of AI-generated, clinician-written, and clinician-edited replies50,51,57. Three implementation studies reported real-world utilization rates of AI drafts in clinical practices, typically measured by how often clinicians selected “Start with Draft” instead of “Start Blank Reply.”31,38,39 One of these studies also calculated the Damerau-Levenshtein distance between AI-generated drafts and final replies as a metric for estimating the editing effort required before clinical use38.

Composite Measures (n = 10). In several studies, some measures were framed to assess multiple dimensions of quality through subjective judgment. Appropriateness, treated as a composite concept, involves evaluating whether the tone of the message was suitable and whether the information provided was adequate in a reply54,56. Potential harm associated with AI-generated responses was assessed by considering not only the risk of incorrect content compromising patient safety but also the possibility of communication that appeared unfriendly or perpetuated bias39,49,55,57. Usefulness or acceptability was often rated based on whether clinicians believed that AI-generated responses could be directly sent to patients, used as a starting point, or help improve the quality of a final response31,39,40,41,46,49.

Consensus from early findings

GenAI responses were generally found to match, and in some cases exceed, the quality of human-authored replies across several dimensions, though risks and limitations remain. GenAI drafts were frequently rated as comparable in information quality and more favorable in communication style compared to clinician-authored responses40,45,46,48,50,51,52,57. Empathy consistently emerged as a notable strength of GenAI drafts39,40,45,46,48,50,51,52,57, with GPT-4 most often recognized as the top-performing model46,48,50,54. However, potential harms associated with these responses, although minimal, were documented39,42,44,49,51,53,54,55,56,57. Common challenges included hallucinations, incoherent language, and limited contextual understanding31,42,51,54,56. One study found that 7% of AI-generated replies posed a risk of severe harm or death55, while another reported two instances in which AI disclosed unsolicited confidential information in messaging involving proxies53. Additionally, studies noted inconsistent AI performance across message types, with reduced reliability in clinically complex inquiries and an increased risk of escalating emotionally charged conversations42,43,44,49,54,56.

Laypersons—and even clinicians—often could not accurately distinguish between AI- and human-authored responses in blinded reviews. Relatedly, several studies asked participants to identify the authorship of responses and reported only low to modest accuracy, with averages ranging from 24% (among patients) to 73% (among clinicians), suggesting that AI-generated replies closely resemble human communication41,43,48,52. While several blinded evaluations showed that participants, particularly patients, tended to favor AI responses45,48,58, one study found that more empathetic and preferable responses were often attributed to human authorship, even when they were actually generated by AI48. Similarly, another study noted that disclosing AI involvement in reply drafting led to a slight decrease in patient satisfaction, although participants still valued transparency over nondisclosure58.

Despite positive attitudes, adoption of GenAI for drafting patient message replies in real-world settings remained limited. While recognizing GenAI’s limitations and the need for edits, clinicians still viewed these tools as helpful aids for managing inbox burden. Several studies highlighted that clinicians found the drafts acceptable or useful as starting points and appreciated features such as templates or pleasantries32,40,41,42,44,46,47,49. Many clinicians also expressed willingness to recommend GenAI tools to colleagues and to retain the tools in future workflows31,32,39,41. However, this enthusiasm did not translate into consistent use. Across pilot implementations, actual utilization of AI-generated drafts was low, with average usage rates no higher than 20%31,38,39. Few studies have explored the disconnect between perceived benefits and limited uptake.

While no strong evidence suggests time savings, current GenAI implementations were associated with perceived efficiency gains and burnout relief. Despite expectations for streamlining workflows, early implementations reported no statistically significant changes in message reply time31,32, and one study even observed an increase in read time following GenAI integration32. Moreover, all studies comparing length found that AI-generated responses were considerably longer than human-written ones, raising concerns about increased burden for draft review and editing32,40,44,45,50,55,57. Nevertheless, survey data revealed that clinicians perceived a meaningful reduction in task and cognitive load, along with decreased work exhaustion31,41. Some also reported a subjective sense of time saved and improved efficiency31,39,41,55, even in the absence of objective evidence for reduced time or workload.

Prompt engineering consistently emerged as an effective strategy for enhancing the quality and usability of GenAI drafts. Across studies, prompt optimization was associated with measurable improvements in response quality, tone, and user acceptance. One study reported a significant increase in clinician acceptance of AI-generated replies after three rounds of prompt refinement, alongside improvements in patient-rated tone and overall message quality41. Another found that a revised prompt led to a reduction in negative clinician feedback on drafts38. Incorporating the most recent assessment and plan into prompts was shown to improve perceived usefulness among clinicians39, while purposely designed prompts helped mitigate inconsistencies between AI- and clinician-authored responses, particularly in relational tone, content relevance, and clinical recommendations44.

Discussion

The synthesis of current research demonstrates a growing interest among health systems in GenAI-assisted replying to patient messages, with various efforts to evaluate draft quality, impacts on clinical efficiency, user perceptions, and the role of prompt engineering. Although varied in study design, scope, and evaluation methods, these early explorations reached some consensus. GenAI-drafted replies were generally perceived as acceptable starting points, especially when enhanced by tailored prompts. Both clinicians and patients recognized its potential to alleviate in-basket burden and enhance patient–provider communication. However, current real-world adoption of GenAI drafts remains limited, and important concerns regarding performance reliability and potential patient risks persist. In this section, we examine the key methodological and implementation limitations, explore ethical considerations, and outline future directions for advancing the effective and responsible integration of GenAI into high-volume clinical in-basket workflows.

Early evaluations and implementations were often constrained in scope, scale, and generalizability. Most studies were conducted at a specific site, within a single health system, or involved relatively small sample sizes of message corpora and participants32,39,40,41,42,43,44,48,51,52,53. Several studies focused on clinicians from certain specialties or patient groups with limited demographic diversity, raising concerns about how well the findings translate across clinical settings or populations31,43,47,48,49,50,54,55,56,57,58. Evaluations were more commonly conducted in simulated environments rather than in live clinical workflows, with many studies assessing carefully selected single-turn messages or hypothetical inquiries46,49,50,51,52,54,55,56,57,58. As a result, these findings may not fully capture the complexity of real-world patient–provider messaging interactions, including diverse topics, contextual cues, or evolving patient conditions.

Studies employed diverse, often unvalidated evaluation rubrics and relied heavily on human judgment from evaluators with varying levels of clinical training31,38,39,41,50,51,52. Draft quality assessments were typically conducted by convenient samples of clinical experts40,52,53, and while most studies did not report inter-rater reliability, a few noted low to moderate levels of reviewer agreement40,46,48. Prompt engineering also differed widely across studies, with many relying on ad hoc or trial-and-error approaches, limiting the reproducibility of these optimizations41,44,52. Additionally, while poor rater agreement suggests diverse communication styles and preferences, current deployments fall short in supporting prompt personalization. This review also noted a lack of transparency around how GenAI tools integrated with EHR systems accessed and utilized medical records. Few studies reported details about incorporating problem lists, clinical notes, or messaging history in draft generation31,51,53, limiting the understanding of how GenAI contextually grounded their responses52. Without consistent access to comprehensive, up-to-date clinical information, the risk of generating inaccurate or context-agnostic replies increases.

Many early explorations acknowledged that patients were underrepresented38,40,41,52,57, with none of the current studies involving patients who actually received AI-generated replies during pilot implementations—pointing to a significant gap in which patient-facing impacts and their preferences were often inferred rather than directly assessed45. Another limitation in understanding user experiences is that, while a few studies collected and analyzed qualitative user feedback, efforts to explore user perspectives in depth remain absent. Without these explorations, it is difficult to interpret current facilitators and barriers48,58 or reconcile conflicting findings, such as disagreements among evaluators40 and the misalignment between positive perceptions and low real-world utilization. Differences in model performance and user perceptions across demographic subgroups were also largely unexplored40,41,43,44,48.

Several studies highlighted important ethical and legal considerations surrounding the responsible integration of GenAI into patient–provider messaging. Transparency—specifically whether and how to disclose AI contributions to patients—emerged as a key question to be addressed39,43,48,58. Despite findings that disclosure may reduce patient satisfaction58, upholding ethical norms in healthcare AI requires supporting patients’ right to be informed when AI is involved in the delivery of their medical information and care39,58,59,60. Concerns on biased model training, cultural insensitivity, lack of AI attribution, and unequal accessibility also raised important liability and equity implications40,42,43,44,45,46,48,50,52,54,56,57. However, current studies often flagged but rarely investigated these risks across patient subgroups. The findings underscore the need to align GenAI deployment with responsible principles from the outset across stages, addressing these issues proactively rather than reactively. Finally, in line with broader recognition in healthcare AI61, human oversight was consistently emphasized across studies as a key safeguard for ensuring the accountable and safe use of GenAI tools in clinical settings42,44,48,50,51,52,53,55,57.

Given the limitations and implications surfaced in early research, this emerging area presents substantial opportunities for advancement. Future research should build on the efforts of Hong et al.42 to continuously refine standardized evaluation frameworks that incorporate both human and computational assessments. A core set of validated and scalable measures would enable more reliable benchmarking, improve reproducibility, and inform best evaluation practices across settings and specialties. While the need for standardization is clear, it is also important to acknowledge the subjective nature of patient–provider communication. Future research should explore personalized GenAI prompting to accommodate individual variation and improve clinical relevance31,32,40. Moreover, as GenAI tools become more embedded in routine clinical workflows, the field would benefit from more longitudinal and multi-center trials to enhance the reliability and generalizability of outcomes31,32,57. Future work should include longer-term evaluations that track GenAI impact on response quality, clinician burnout, patient satisfaction, and clinical outcomes over time to better understand its real-world implications in care delivery. In parallel, greater attention is needed to examine how GenAI systems access and incorporate clinical information from the EHR31,44,46. Studies should also explore how this process might be customized by clinical specialty or patient group to improve draft relevance.

Patient perspectives should also be prioritized in future research31,32,38,40,43,46,52. While patients are the recipients of AI-generated replies, few studies have directly evaluated their experiences. The linguistic complexity of GenAI outputs may be manageable for clinicians but burdensome for patients with limited health or English literacy40. Future studies should assess patient expectations, comprehension, preferences, and satisfaction with GenAI-assisted replies and involve patients directly in the co-design of prompt engineering, usability evaluations, and disclosure or consent strategies. Additionally, a few studies reported that GenAI did not generate drafts for all patient messages during pilot deployments32,41. How the absence of certain drafts may lead to inconsistency in communication style and affect patient experience or trust warrants further investigation. Addressing fairness and mitigating model bias will also be essential to ensure GenAI systems function equitably across diverse patient populations43,62. To promote responsible GenAI applications, patient perspectives, along with ethical and inclusive considerations, should be prioritized and integrated early across all stages of design, development, evaluation, and implementation.

User training represents another critical area for future inquiry. Despite the recognized benefit of human–AI collaboration, clinicians currently work with GenAI drafts with limited guidance or support31. Targeted training programs are needed to help clinicians understand GenAI’s capabilities and limitations56, enabling them to make informed edits, prevent over-reliance, and ensure adequate oversight. At the same time, researchers, health system leaders, and policymakers should work to establish clear governance frameworks for AI-assisted messaging in response to ongoing calls for responsible AI in healthcare63,64. This includes addressing automation bias43,46,55, which can influence provider behavior, judgment, and decision-making, and ultimately affect patient outcomes. Additionally, the growing prevalence of billing for patient portal messaging may further complicate the integration of GenAI into patient communication21. This makes the need for guidelines and oversight even more pressing to safeguard patient satisfaction and trust. Institutions must develop clear policies on AI disclosure, informed consent, and data privacy to ensure transparency and uphold ethical standards in digitally mediated care.

This review contributes to the growing body of knowledge on using GenAI to respond to patient questions and inquiries, particularly within the EHR context, where it integrates medical records to assist patient–provider communication as part of clinical care. The synthesis presented here can be compared with existing reviews that examine GenAI as a tool for patient and medical education25,34, as well as literature investigating its use as a medical chatbot65. These comparisons help reveal the distinct benefits and challenges of GenAI applications across various health information-seeking settings and underscore the differences between viewing GenAI as a supportive assistant versus as an independent agent. Such distinctions may guide researchers and clinical stakeholders in further identifying appropriate directions and priorities. Additionally, as recent work has also begun to examine the use of LLMs to assist patients in writing efficient messages to their healthcare providers66, it is important to consider how AI’s presence on both sides of the communication may create interactive effects and reshape the patient–provider relationship.

This review processes several limitations. All studies included in this review were conducted in English and based in the United States, which limits the generalizability of our findings and does not reflect global efforts relevant to this topic. Generative AI applications in patient communication may differ substantially across countries due to variations in language, digital infrastructure, and regulatory environments. As such, this review may primarily inform contexts with similar health system characteristics. During the screening process, we also identified early studies that evaluated AI-generated replies using public patient inquiries from platforms such as social media or institutional websites, conducted prior to the availability of HIPAA-compliant tools27. While these studies provided useful early insights into the feasibility of GenAI-assisted messaging, we excluded them to maintain a focus on evaluations situated within health systems or EHR-integrated settings. We conducted a quality assessment using the MMAT; however, the quality results may be suboptimal due to the variability and exploratory nature of these early studies, which often aim to test feasibility and explore emerging practices rather than follow standardized methodological rigor. Despite these limitations, this review offers an important synthesis of empirical evaluations and highlights emerging opportunities and challenges in the integration of GenAI into patient–provider communication via portal messaging, addressing the growing interest in this rapidly evolving field.

In conclusion, this review systematically synthesizes early studies exploring the use of GenAI to draft responses to patient messages, highlighting the promising quality of AI-generated replies and the positive reception from both clinicians and patients. In addition to these encouraging findings, we also identified key limitations in the current evidence base, along with persistent risks and challenges to the effective and safe integration of GenAI into real-world clinical workflows. As these technologies continue to evolve, it is critical to establish shared evaluation standards, develop practical guidelines for disclosure and oversight, and engage diverse stakeholders in shaping responsible implementation. Our findings offer timely insights for health system researchers, leaders, and policymakers aiming to leverage GenAI as a novel tool to address clinician in-basket overload and enhance patient–provider communication via portal messaging.

Methods

This review followed the 2020 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)67 guideline for systematic reviews without meta-analysis to ensure methodological transparency and reproducibility. The review protocol was not registered in systematic review registries due to its focused scope and rapid timeline.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This review focuses on original research articles that explore the use of GenAI to draft replies to patient messages within the EHR context. Eligible studies were required to present empirical findings from implementations, evaluations, or stakeholder perspectives. As this is an emerging area of research, we also included short reports such as brief communications, research letters, and perspective papers with empirical results. Studies were excluded if they were not published in English or focused solely on non-English outputs. We also excluded studies evaluating GenAI responses to general frequently asked patient questions on institutional websites or to inquiries posted on public platforms outside the EHR or patient portal setting. Patient-facing chatbots developed as standalone health assistants were also not considered. Lastly, we excluded non-peer-reviewed preprints, posters, and abstracts due to incomplete reporting, as well as non-empirical articles such as editorials, opinion pieces, and system design descriptions.

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed on April 5, 2025, using five electronic databases: PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, IEEE Xplore, and the ACM Digital Library. The search targeted metadata fields (title, abstract, and keywords) and was tailored to each database’s syntax. Search terms included “generative artificial intelligence”, “patient, message”, and “response” as well as their synonyms and variants. To maximize retrieval sensitivity, we also included the terms “question” and “inquiry”, which may be used in place of “message” in this context, to capture studies evaluating GenAI responses to patient messages described with different terminology. No time or language filters were applied during the search. A complete list of searching terms is provided in (Table 3).

Study screening and data extraction

Titles and abstracts were independently screened by two of four authors (DH, YG, YZ, LF). At this stage, without reviewing full-text content, we focused on identifying studies that explored GenAI for responding to messages, inquiries, or questions from patients. Disagreements were resolved through consensus discussions involving at least two authors. Articles meeting these criteria were retrieved for full-text screening. Each full text was independently reviewed by two of three authors (DH, YG, and YZ), based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with the senior author (KZ).

Following the screening process, an initial data extraction template was developed based on the full-text review of the included studies and the research questions of this review. Two authors (DH and YG) performed data extraction for the first five studies and held meetings to adjust the template as needed. The final template captures study characteristics, context, objectives, design, participants, outcomes, findings, limitations, and implications. After finalizing the template, each included study was independently coded by the two authors. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved with input from the senior author (KZ), ensuring consistency and interpretive rigor across the dataset. Table 2 in the Results section reflects the key structure of our extraction template.

Quality assessment

We conducted quality assessment using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT)68, a critical appraisal tool developed for systematic mixed-studies reviews. The MMAT provides evaluation criteria across five study types: qualitative research, randomized controlled trials, nonrandomized studies, quantitative descriptive studies, and mixed methods. These categories reflected the study designs included in our review. Two authors (DH and either YG or YZ) performed the assessments independently and resolved any disagreements through discussion. Ratings for each criterion were based on informed judgment guided by the MMAT manual, considering the study objectives, context, and the developmental stage of research in this area. As encouraged by the MMAT, we reported criterion-level ratings in (Table 1).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Lyles, C. R. et al. Using electronic health record portals to improve patient engagement: research priorities and best practices. Ann. Intern. Med. 172, S123–S129 (2020).

Lieu, T. A. et al. Primary care physicians’ experiences with and strategies for managing electronic messages. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e1918287 (2019).

Haun, J. N. et al. Evaluating user experiences of the secure messaging tool on the Veterans Affairs’ patient portal system. J. Med. Internet Res. 16, e2976 (2014).

Sun, S., Zhou, X., Denny, J. C., Rosenbloom, T. S. & Xu, H. Messaging to your doctors: understanding patient-provider communications via a portal system. In Proc. IGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 1739–1748 https://doi.org/10.1145/2470654.2466230 (ACM, 2013).

Rights (OCR), O. for C. HITECH Act Enforcement Interim Final Rule. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/hitech-act-enforcement-interim-final-rule/index.html (2009).

Griffin, A., Skinner, A., Thornhill, J. & Weinberger, M. Patient portals. Appl. Clin. Inform. 7, 489–501 (2016).

North, F. et al. A retrospective analysis of provider-to-patient secure messages: how much are they increasing, who is doing the work, and is the work happening after hours? JMIR Med. Inform. 8, e16521 (2020).

Holmgren, A. J., Apathy, N. C., Crews, J. & Shanafelt, T. National trends in oncology specialists’ EHR inbox work, 2019-2022. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djaf052 (2025).

Holmgren, A. J. et al. Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinician ambulatory electronic health record use. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 29, 453–460 (2022).

Adler-Milstein, J., Zhao, W., Willard-Grace, R., Knox, M. & Grumbach, K. Electronic health records and burnout: Time spent on the electronic health record after hours and message volume associated with exhaustion but not with cynicism among primary care clinicians. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. JAMIA 27, 531–538 (2020).

Akbar, F. et al. Physicians’ electronic inbox work patterns and factors associated with high inbox work duration. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. JAMIA 28, 923–930 (2021).

Arndt, B. G. et al. Tethered to the EHR: primary care physician workload assessment using EHR event log data and time-motion observations. Ann. Fam. Med. 15, 419–426 (2017).

Akbar, F. et al. Physician stress during electronic health record inbox work: in situ measurement with wearable sensors. JMIR Med. Inform. 9, e24014 (2021).

Tai-Seale, M. et al. Physicians’ well-being linked to in-basket messages generated by algorithms in electronic health records. Health Aff. Proj. Hope 38, 1073–1078 (2019).

Hilliard, R. W., Haskell, J. & Gardner, R. L. Are specific elements of electronic health record use associated with clinician burnout more than others? J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. JAMIA 27, 1401 (2020).

Ariely, D. & Lanier, W. L. Disturbing trends in physician burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance: dealing with malady among the nation’s healers. Mayo Clin. Proc. 90, 1593–1596 (2015).

Smith, L., Kirk, W., Bennett, M. M., Youens, K. & Ramm, J. From headache to handled: advanced in-basket management system in primary care clinics reduces provider workload burden and self-reported burnout. Appl. Clin. Inform. 15, 869–876 (2024).

Fogg, J. F. & Sinsky, C. A. In-basket reduction: a multiyear pragmatic approach to lessen the work burden of primary care physicians. NEJM Catal. 4, CAT.22.0438 (2023).

Cronin, R. M., Fabbri, D., Denny, J. C., Rosenbloom, S. T. & Jackson, G. P. A comparison of rule-based and machine learning approaches for classifying patient portal messages. Int. J. Med. Inf. 105, 110–120 (2017).

Yang, J. et al. Development and evaluation of an artificial intelligence-based workflow for the prioritization of patient portal messages. JAMIA Open 7, ooae078 (2024).

Liu, T., Zhu, Z., Holmgren, A. J. & Ellimoottil, C. National trends in billing patient portal messages as e-visit services in traditional Medicare. Health Aff. Sch. 2, qxae040 (2024).

Holmgren, A. J., Grouse, C. K., Oates, A., O’Brien, J. & Byron, M. E. Changes in secure messaging after implementation of billing e-visits by demographic group. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2427053 (2024).

Matulis, J. & McCoy, R. Relief in sight? Chatbots, in-baskets, and the overwhelmed primary care clinician. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 38, 2808–2815 (2023).

Waldock, W. J. et al. The accuracy and capability of artificial intelligence solutions in health care examinations and certificates: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e56532 (2024).

Zong, H. et al. Large language models in worldwide medical exams: platform development and comprehensive analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e66114 (2024).

Luo, M., Warren, C. J., Cheng, L., Abdul-Muhsin, H. M. & Banerjee, I. Assessing empathy in large language models with real-world physician-patient interactions. In Proc. 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData) 6510–6519 https://doi.org/10.1109/BigData62323.2024.10825307 (2024).

Ayers, J. W. et al. Comparing physician and artificial intelligence chatbot responses to patient questions posted to a public social media forum. JAMA Intern. Med. 183, 589–596 (2023).

Armitage, H. A. I. assists clinicians in responding to patient messages at Stanford Medicine. News Center https://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2024/03/ai-patient-messages.html (2024).

Introducing Dr. Chatbot. https://today.ucsd.edu/story/introducing-dr-chatbot.

Gen A.I. Saves nurses time by drafting responses to patient messages. EpicShare https://www.epicshare.org/share-and-learn/mayo-ai-message-responses.

Garcia, P. et al. Artificial intelligence–generated draft replies to patient inbox messages. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e243201 (2024).

Tai-Seale, M. et al. AI-generated draft replies integrated into health records and physicians’ electronic communication. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e246565 (2024).

Singh, G. B., Kumar, R., Ghosh, R. C., Bhakhuni, P. & Sharma, N. Question answering in medical domain using natural language processing: a review. In Proc. ata Management, Analytics and Innovation (eds. Sharma, N., Goje, A. C., Chakrabarti, A. & Bruckstein, A. M.) 385–397 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-3245-6_26. (Springer Nature, Singapore, 2024).

Aydin, S., Karabacak, M., Vlachos, V. & Margetis, K. Large language models in patient education: a scoping review of applications in medicine. Front. Med. 11, 1477898 (2024).

Wei, Q. et al. Evaluation of ChatGPT-generated medical responses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Biomed. Inform. 151, 104620 (2024).

Ford, D. W., Tisoskey, S. P. & Locantore-Ford, P. A. Building trust: developing an ethical communication framework for navigating artificial intelligence discussions and addressing potential patient concerns. Blood 142, 7229 (2023).

Binkley, C. E. & Pilkington, B. C. Informed consent for clinician-AI collaboration and patient data sharing: substantive, illusory, or both. Am. J. Bioeth. 23, 83–85 (2023).

Afshar, M. et al. Prompt engineering with a large language model to assist providers in responding to patient inquiries: a real-time implementation in the electronic health record. JAMIA Open 7, ooae080 (2024).

English, E., Laughlin, J., Sippel, J., DeCamp, M. & Lin, C.-T. Utility of artificial intelligence–generative draft replies to patient messages. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2438573 (2024).

Small, W. R. et al. Large language model–based responses to patients’ in-basket messages. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2422399 (2024).

Yan, S. et al. Prompt engineering on leveraging large language models in generating response to InBasket messages. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 31, 2263–2270 (2024).

Hong, C. et al. Application of unified health large language model evaluation framework to In-Basket message replies: bridging qualitative and quantitative assessments. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc 32, ocaf023 https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaf023 (2025).

Nov, O., Singh, N. & Mann, D. Putting ChatGPT’s medical advice to the (Turing) test: survey study. JMIR Med. Educ. 9, e46939 (2023).

Baxter, S. L., Longhurst, C. A., Millen, M., Sitapati, A. M. & Tai-Seale, M. Generative artificial intelligence responses to patient messages in the electronic health record: early lessons learned. JAMIA Open 7, ooae028 (2024).

Kim, J. et al. Perspectives on artificial intelligence–generated responses to patient messages. JAMA Netw. Open 7, e2438535 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. Leveraging large language models for generating responses to patient messages—a subjective analysis. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 31, 1367–1379 (2024).

Reynolds, K. et al. Comparing the quality of ChatGPT- and physician-generated responses to patients’ dermatology questions in the electronic medical record. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 49, 715–718 (2024).

Robinson, E. J. et al. Physician vs. AI-generated messages in urology: evaluation of accuracy, completeness, and preference by patients and physicians. World J. Urol. 43, 48 (2024).

Scott, M. et al. Assessing artificial intelligence–generated responses to urology patient in-basket messages. Urol. Pract. 11, 793–798 (2024).

Soroudi, D. et al. Comparing provider and ChatGPT responses to breast reconstruction patient questions in the electronic health record. Ann. Plast. Surg. 93, 541 (2024).

Hao, Y. et al. Retrospective comparative analysis of prostate cancer in-basket messages: responses from closed-domain large language models versus clinical teams. Mayo Clin. Proc. Digit. Health 3, 100198 (2025).

Kaur, A., Budko, A., Liu, K., Steitz, B. & Johnson, K. Primary care providers acceptance of generative AI responses to patient portal messages. Appl. Clin. Inform. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-2565-9155 (2025).

Tse, G. et al. Large language model responses to adolescent patient and proxy messages. JAMA Pediatr. 179, 93–94 (2025).

Athavale, A., Baier, J., Ross, E. & Fukaya, E. The potential of chatbots in chronic venous disease patient management. JVS Vasc. Insights 1, 100019 (2023).

Chen, S. et al. The effect of using a large language model to respond to patient messages. Lancent Digit. Health 6, e379–e381 (2024).

Tailor, P. D. et al. Appropriateness of ophthalmology recommendations from an online chat-based artificial intelligence model. Mayo Clin. Proc. Digit. Health 2, 119–128 (2024).

Tailor, P. D. et al. A comparative study of responses to retina questions from either experts, expert-edited large language models, or expert-edited large language models alone. Ophthalmol. Sci. 4, 100485 (2024).

Cavalier, J. S. et al. Ethics in patient preferences for artificial intelligence–drafted responses to electronic messages. JAMA Netw. Open 8, e250449 (2025).

Jeyaraman, M., Balaji, S., Jeyaraman, N. & Yadav, S. Unraveling the ethical enigma: artificial intelligence in healthcare. Cureus 15, e43262 (2023).

Park, H. J. Patient perspectives on informed consent for medical AI: a web-based experiment. Digit. Health 10, 20552076241247938 (2024).

De Cremer, D. & Kasparov, G. The ethical AI—paradox: why better technology needs more and not less human responsibility. AI Ethics 2, 1–4 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. Ethical considerations of using ChatGPT in health care. J. Med. Internet Res. 25, e48009 (2023).

Upadhyay, U. et al. Call for the responsible artificial intelligence in the healthcare. BMJ Health Care Inform. 30, e100920 (2023).

Trocin, C., Mikalef, P., Papamitsiou, Z. & Conboy, K. Responsible AI for digital health: a synthesis and a research agenda. Inf. Syst. Front. 25, 2139–2157 (2023).

Giuffrè, M. et al. Systematic review: the use of large language models as medical chatbots in digestive diseases. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 60, 144–166 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. Using large language model to guide patients to create efficient and comprehensive clinical care message. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 31, 1665–1670 (2024).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71 (2021).

Hong, Q. N. et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 34, 285–291 (2018).

Acknowledgements

No specific funding support or contributions to acknowledge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.H. conceptualized the study, developed the search strategy, conducted the literature searches, led study review, and drafted the manu. Contributed to refining the inclusion criteria and participated in data screening and extraction. L.F. participated in the data screening and contributed to consensus discussions. K.Z. Supervised the study, provided methodological guidance, and helped resolve discrepancies during screening and extraction. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, D., Guo, Y., Zhou, Y. et al. A systematic review of early evidence on generative AI for drafting responses to patient messages. npj Health Syst. 2, 27 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44401-025-00032-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44401-025-00032-5