Abstract

Plastic products can release particles during everyday use, contaminating food and beverages and ultimately entering the human body through ingestion. However, the concentrations of these particles and the extent of human exposure remain poorly understood. While many studies have focused on characterizing the release of microplastics (MPs, > 1 μm), studies on nanoplastics (NPs, < 1 μm) remain limited due to significant analytical challenges associated with their small size. This study addressed this knowledge gap by investigating the release of both NPs and MPs from Australian-sourced polypropylene plastic kettles under normal use conditions using multiple orthogonal analytical techniques. During the initial boil cycles, the average releases were 0.011 ± 0.005 µg/cm2 for NPs and 0.032 ± 0.016 µg/cm2 for MPs. These releases decreased to around 0.003 ± 0.002 µg/cm2 for NPs and 0.013 ± 0.007 µg/cm2 for MPs by the tenth boil, stabilizing at levels below 0.002 ± 0.001 µg/cm2 and 0.006 ± 0.004 µg/cm2, respectively following 50 boils. After 150 boil cycles, the release declined significantly to 0.0004 ± 0.0002 µg/cm2 for NPs and 0.002 ± 0.001 µg/cm2 for MPs. The release of particles followed first-order kinetics, indicating that the release rate was directly proportional to the concentration of particles on the kettle’s inner surface. Although the number of nanoparticles declined over time, their size remained constant, with modal diameters of approximately 210 nm (measured via nanoparticle tracking analysis) and 580 nm (measured using Microtrac Sync particle analysis). To identify and characterize the polymeric composition of the released nanoparticles, we employed a novel analytical approach combining asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation with multi-angle light scattering (AF4-MALS) with fraction collection followed by pyrolysis-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (Pyr-GC-MS/MS). This integrated method enabled precise detection and chemical profiling of polypropylene NPs, representing a significant methodological advancement in NP analysis. Notably, the study also found that water chemistry influences particle release: boiling with hard tap water (125 ppm) significantly reduced NP concentrations compared to ultrapure MilliQ water. These findings provide new evidence on the release of NPs and MPs from plastic kettles, contributing to our understanding of potential exposure sources.

Created in BioRender. Shi, K. (2025) https://BioRender.com/7jhhu0q

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plastics are among the most widely used materials globally, valued for their durability, lightweight nature, and low production cost1. However, microplastics (MPs, particles between 1 and 5000 µm) and nanoplastics (NPs, particles < 1 µm) can be released during the routine use of plastic products2, representing an important and increasingly recognized pathway of human exposure3. Studies have shown that the repeated use of polyethylene (PE) chopping boards can result in an annual intake of 7.4 to 51 g of MPs per person, while polypropylene (PP) chopping boards may contribute approximately 50 g per person annually3. Steeping a single plastic teabag has been reported to release approximately 11.6 billion MPs and 3.1 billion NPs4. Additionally, the concentration of MPs released from PP infant feeding bottles can be as high as 16.2 million particles/L5. These findings highlight that plastic consumer products can release quantities of NPs and MPs, contributing to human exposure, particularly through ingestion.

In recent years, plastic particles have been reported in various human biological samples, including of human breast milk6, blood, urine7, stool8 and tissues such as the placenta9, lung10, and liver11 suggesting the potential for internal exposure. However, definitive studies are still lacking12. Therefore, understanding the direct release of NPs and MPs from everyday plastic products is crucial for accurately assessing human exposure. Identifying these sources is essential to enable policymakers to develop effective mitigation strategies that safeguard both human health and the environment.

Plastic kettles, a common household appliance, have emerged as a potential source of NP and MP exposure. In 2018, sales of electric kettles in the EU-27 (excluding the UK) were approximately 16.3 million units/year, with PP being the most commonly used kettle body material, accounting for 83% of the market share13,14. Research has shown that plastic kettles can release up to 30 million particles per liter during boiling15. However, the study employed comparative dynamic image analysis with the FlowCam technique, which relies solely on optical particle detection and does not provide definitive or unequivocal identification of the particles as plastics or polymers. Similarly, after boiling deionized water in a plastic kettle 40 times, the concentration of MPs increased to 15 million per liter14. Raman micro-spectroscopy, with a detection size-limit of approximately 1 µm, was employed to chemically identify the particles. Meanwhile the particle count quantity, concentration and size distribution of MPs were analyzed using ImageJ software14. This aforementioned approach cannot definitively confirm the chemical composition of all released particles, raising uncertainty about whether they are plastics or potentially oligomers. Consequently, the study inferred the polymeric nature of the particles without direct chemical confirmation using polymer standards14. Although not yet conclusive, these earlier findings suggest that the regular use of plastic kettles may contribute to human ingestion of plastic particles. This highlights the need to better understand the characteristics and release mechanisms of plastic particles from these appliances.

Despite the above studies reporting the release of potential plastic particles from kettles, a substantial knowledge gap persists in the quantitative detection and comprehensive characterization of NPs released from plastic products as their size provides many analytical challenges. A recent review article on the NPs and MPs released from food containers and packaging, highlighted that current studies lacked methodological capabilities to detect particles (<10 µm) and NPs, with the size detection limits often above 10 µm16, depending on the analytical techniques employed. These methodological limitations have hindered the accurate assessment of NPs prevalence and hampered exposure assessment, leaving a critical knowledge gap in our understanding of the direct release or exposure to NPs through plastic products. The toxicity and health risks of ingested NPs and MPs are strongly size-dependent, with particles < 10 µm, including NPs, posing the greatest concerns due to their ability to cross biological barriers, penetrate biological membranes, and potentially disrupt cellular function17,18,19,20,21. This underscores the urgent need for methodological advancements to accurately evaluate exposures to these particles. Given the growing body of evidence on the potential health hazards posed by NPs and their significantly smaller size22,23,24,25,26,27,28, investigating their release from plastic products, including kettles, is essential. Such research will provide comprehensive data that can inform exposure assessments and human health risk evaluations.

This study aims to provide the first comprehensive investigation into the presence and characterization of both NPs and MPs released from PP plastic kettles under normal use conditions. A multi-technique analytical orthogonal approach was employed to ensure robust detection and characterization. Samples were filtered to separate MPs (>1 µm), while NPs (<1 µm) were further pre-concentrated using an Amicon® Stirred Cell ultrafiltration system (100 kDa cutoff, ~10 nm). For chemical identification and quantification, pyrolysis-gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (Pyr-GC/MS) was used to determine the mass concentrations of PP-derived NPs and MPs. The NP fraction was further characterized by combining asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation with multi-angle light scattering (AF4-MALS) and Pyr-GC-MS/MS. Physical characterization of the released nanoparticles including surface morphology and size was conducted using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) was employed to assess particle size distribution and concentration, while a Microtrac Sync particle analyzer was used to further evaluate particle size, shape, and count.

Results and discussion

Nanoplastic and microplastic release

The efficiency of NP and MP recovery was evaluated by spiking MilliQ water with known concentrations of plastic standards of varying particle sizes. The samples were then processed through the full treatment and extraction protocols, with the procedure repeated in triplicate to ensure accuracy and consistency. The rates of recovery for the selected NPs (PS, PMMA) and MPs (PE, PP) were 78.7–106.4% and 70.4–82.8%, respectively (Supplementary Table 1 and 2), and comparable to previous studies29,30. This is likely due to the combined effects of particle interactions with the container surface, variable retention or release during ultrafiltration, and the cumulative losses or recoveries introduced through multi-step processing (including ultrafiltration, freeze-drying, and cup loading).

Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure 1 presents the release and mass concentration of PP NPs and MPs from the two kettle brands investigated in this study following multiple boil cycles, respectively. The release of MPs (0.038 ± 0.016 µg/cm2) from brand A kettle was significantly higher than that from brand B kettle (0.026 ± 0.014 µg/cm2) at the first boil (Fig. 1). This release decreased to around 0.013 ± 0.007 µg/cm2 by the tenth boil, then continued to decline more gradually, stabilizing below 0.006 ± 0.004 µg/cm2 following approximately 50 boils. Similarly, the release of NPs significantly decreased and then stabilized with increased boils (Fig. 1). The initial release of NPs from the two new kettles (brands) were 0.013 ± 0.004 µg/cm2 and 0.010 ± 0.005 µg/cm2, respectively (Fig. 1). The release dropped to approximately 0.003 ± 0.002 µg/cm2 by the tenth boiling cycle, stabilizing at levels below 0.002 ± 0.001 µg/cm2 after about 50 boils. After 150 boils, the release of NPs dropped to 0.0004 ± 0.0002 µg/cm2, representing a 96.36% reduction compared to the first boil. The results suggest that the kettle manufacturing process may have contributed to the production of a substantial quantity of loosely adhered surface NPs and MPs or particles located near the surface14. Consequently, the observed decrease in the release of NPs and MPs after multiple boil cycles could be attributed to the gradual removal of these loosely bound particles during boiling, coupled with the potential formation of new NPs and MPs within the kettle over time.

Dynamics of NP and MP release

The release of PP NPs and MPs from the plastic kettles over time was modelled to better understand the release dynamics (Supplementary Figure 2 a-d). This approach showed that the release of the PP particles occurred in first-order kinetics, indicating that the rate of release is directly proportional to the concentration of particles on the inner surface of the kettle. The release of the MPs demonstrated a strong fit to this model (R2 > 0.94 for both brand A and brand B). Similarly, for NPs, brand A and B showed reasonable correlation fits, with R2 values of 0.90 and 0.81, respectively. The overarching trend of a high initial release of PP particles followed by a gradual decline over time was evident and aligned well with a first-order release model or release mechanism. These results provide valuable insights into the mechanism of NP and MP release from plastic kettles.

Quantification of nanoparticle release: Particle concentration

Compared to MPs, NPs are of greater concern to environmental and human health due to their high surface area-to-volume ratio and increased potential to cross biological barriers due to their small size19,20,24,31. Therefore, this study focused on analyzing the particle size distribution and particle count concentration of nanoparticles (not chemically identified or confirmed as plastics). The mean sizes of the nanoparticles released from the new kettles were 209 and 584 nm when measured by NTA and Sync analysis, respectively (Fig. 2a, e). The size distribution peaks for the released nanoparticles varied according to NTA analysis at different boiled cycles (Fig. 2a–c). Additionally, NTA data showed smaller sized particles compared to Sync analysis (Fig. 2). This discrepancy may be due to NTA’s assumption that all particles are spherical32, as well as different instrument detection limits and measurement uncertainties.

The particle size distribution of nanoparticles at a boil 1, b boils 75, and c boils 150 was detected by NTA. The black line represents the mean value, while the shaded area represents the deviation of the three measurements. The particle size distributions of nanoparticles at e boil 1, f boils 75 g boils 150 were detected by Sync. The particle count concentration of nanoparticles was detected by d NTA and h Sync with the contribution from the blank samples subtracted. See Supplementary Figure 4 for blank sample data.

In the blank samples, the particle count concentration of nanoparticles was 1.24 × 106 particles/L and 251 particle/L, as detected by NTA and Sync, respectively (Supplementary Figure 3). The particle count concentration in the samples, with the blank contributions subtracted, are shown in Fig. 2d, h. The new kettles released 1.18 × 107 and 10768 particles/L, as detected by NTA and Sync, respectively. Furthermore, the particle count concentration decreased significantly with repeated boiling cycles, while the size of the released particles remained relatively consistent (Fig. 2). The relatively constant particle size distributions observed over repeated boiling cycles suggest minimal detectable morphological changes in polypropylene under the tested conditions; however, future work could investigate polymer degradation and crystalline structure alterations to further elucidate release mechanisms. NTA can overestimate particle count concentrations compared to other methods and the application of NTA for the analysis of polydisperse samples is challenging33,34,35. Bachurski et al. found that the NanoSight NS300 overestimated the particle count concentration of PS and silica nanospheres by a factor of 2.0 to 2.136.

There were significant discrepancies between the particle size and count concentration data obtained by the NTA and Sync. The Microtrac Sync measures scattering intensity, which may result in reduced sensitivity for smaller particles due to their lower light scattering, potentially leading to an underestimation of nanoparticle concentration, especially when the sample contains a high number of very small particles. In contrast, NTA tracks the Brownian motion of individual particles, offering higher sensitivity and enabling more accurate measurement of both nanoparticle size and count concentration37.

Morphological characterization of released nanoparticles

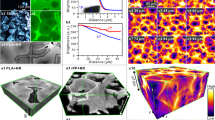

The surface morphology of nanoparticles released from the kettles following different numbers of boils was assessed by SEM (Figure 3). The nanoparticles exhibited a variety of irregular shapes, including pellets, slices, and strips. After 150 boils, the kettle released nanoparticles that were smaller in size and more dispersed (Fig. 3d). Nanoparticle sizes were estimated from the SEM images using ImageJ software, with sizes concentrated at 35 and 79 nm (Supplementary Figure 5). SEM images also confirmed that concentrated MilliQ water (blank sample) contained a small number of nanoparticles (Supplementary Figure 6). These results are consistent with the NTA and Sync analysis (Supplementary Figure 3). To further observe the morphologies of the nanoparticles and facilitate physical characterization, TEM was used to image the region of interest as shown in Fig. 4. Figure 4 shows a variety of irregular shapes, including flakes, smaller aggregates or dispersed clusters of very fine particles and larger or more defined fragment nanoparticles in the samples analyzed (i.e., images for boil 1 and boils 150). However, due to lack of chemical characterization, it could not be definitively confirmed whether the nanoparticles observed in the SEM and TEM images were or contained PP NPs.

SEM image of the control group can be found in Supplementary Figure 6.

Chemical characterization of released nanoparticles

To chemically characterize if the nanoparticles measured in the boiled water samples were composed of or contained PP NPs, their particle size distribution was further characterized using AF4-MALS. Particles within each size range or associated with each size range (60 to 300 nm, Table 1) were fractionated and collected for subsequent analysis using Pyr-GC-MS/MS to determine polymer composition38. No PP nanoparticles were detected in the blank control samples (Supplementary Figure 7). Compared to a mixed PS standard analyzed by the AF4-MALS, the peak of the released nanoparticles from the kettle sample was broader and less intense (Supplementary Figure 8 and 9). This possibly indicates that some nanoparticles aggregated during the filtration process, altering their size39. Table 1 shows the size ranges of nanoparticles measured from kettles after 1 and 150 boils by AF4-MALS, along with the mass concentration of PP quantified within each size range by Pyr-GC-MS/MS. PP NPs were detected in both size ranges separated by AF4, with higher mass concentrations of released NPs at the first boil compared to the 150th boil. Larger PP NPs (200–300 nm) were more prevalent during the kettle’s first use, whereas a greater proportion of smaller-sized NPs (60–130 nm) was observed after 150 boils. This trend could suggest that the release of larger NPs may be associated with initial shedding from material layers, surface coatings, or manufacturing residues, whereas the formation of smaller NPs over time could result from progressive material degradation or wear. Additionally, the total concentration of PP NPs collected after AF4 separation was lower than that determined by direct Pyr-GC/MS analysis (as shown in Table 1and Supplementary Figure 1b). This discrepancy may be due to nanoparticle aggregation during the AF4 separation process, leading to shifts in retention times or incomplete separation, or losses due to interaction with surfaces within the instrument (channel membrane, tubing etc.) resulting in an underestimation of the total concentration of PP NPs.

This study represents the first comprehensive effort to simultaneously characterize nanoparticles release from plastic kettles and chemically quantify the polymer mass concentrations or chemical compositions within specific size ranges or collected fractions. By combining these approaches, the study provides definitive evidence that the detected nanoparticles composed of or contained PP NPs. This advancement addresses a critical gap in previous studies, where nanoparticles were often presumed to be NPs without direct chemical confirmation.

Effect of water hardness on NP and MP release rates

Differences in water hardness have previously been shown to affect the efficiency and concentration of MPs released from kettles14. Since both brands of plastic kettles exhibited similar trends in PP particle release (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figure 1 and 2), the brand A kettle was selected to investigate the effect of water hardness on particle release. Two new and identical brand A kettles were thoroughly cleaned and then boiled with tap water (approximately 25 °C) for 1, 5, 25, 75, and 100 boils, following the same procedure as described above for MilliQ water. The hardness of tap water and MilliQ water (used in this study) was measured using water hardness test strips and was 125 and 0 ppm, respectively. The tap water test was duplicated, showing consistent trends in PP NPs and MPs release from the plastic kettle.

To determine potential contamination during the sample preparation process, triplicate 1 L samples of tap water were placed in a glass beaker with a glass cover and boiled on a hotplate as blank samples. Figure 5 shows the release and mass concentrations of NPs and MPs released from the kettle using tap water, respectively. The MP concentrations did not show a significant trend after the boil cycles, which may be due to the inherent uncertainty in measuring MPs both in the kettle and in tap water. However, the release of NPs decreased from 0.004 ± 0.0008 to 0.0002 ± 0.00001 µg/cm2 following 100 boils. The mass concentration of NPs release for the tap water boiled kettle experiment was slightly lower compared to MilliQ water (Fig. 5d).

a Influence of tap water on the release of MPs concentration; b Influence of tap water on the release of NPs concentration; c Influence of tap water on the release of MPs and NPs; d The mass concentration of NPs released using tap water and MilliQ water; Horizontal axes show the number of boils; vertical axes show the amount released per cm2and mass concentrations.

Tap water typically contains various ions that are likely to precipitate, potentially transferring released NPs into the scale precipitate. Tap water with specific alkalinity (\({{\rm{HCO}}}_{3}^{-}\), \({{\rm{CO}}}_{3}^{2-}\), OH−) and hardness (Ca2⁺, Mg2⁺) will gradually form limescale deposits (CaCO3, Mg(OH)2) during the boiling and cooling process40. Hard water leads to the formation of limescale films on kettle surfaces, which may affect the release of NPs. This finding is consistent with previous research showing that synthetic drinking water boiled in kettles released significantly lower levels of MPs, regardless of the type of ions present14.

Surface morphology

To better understand the source of the particles from the kettles, the inner surface of the kettle before and after use was characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM). The inner surface of the new kettle (before the release experiments) was shown to be relatively rough with noticeable texture (Fig. 6a). The particles observed on the surface are likely residues from the manufacturing process, which may have contributed to the release of NPs and MPs during the kettle’s initial use (Fig. 6a). For the kettles boiled with MilliQ water (following 150 boils), the surface structure was different to that of a new kettle (Fig. 6a and b), with the inner surface becoming relatively smooth by prolonged boiling (Fig. 6b). When the kettle was boiled with tap water, rod-like and granular deposits formed on the interior surface (Fig. 6c). These deposits create a passivation layer, which may reduce the release of NPs by acting as a protective barrier over time41. This supports the Pyr-GC/MS analysis data where the mass concentration of NPs decreased from 0.004 ± 0.0008 to 0.0002 ± 0.00001 µg/cm2 following 100 boils (Fig. 5c). The AFM results showed that the roughness of the new kettle (22 nm) was similar to that of kettle boiled with MilliQ water (34 nm) but increased substantially to 92 nm with tap water (Fig. 6d–f). This increase in roughness is likely due to the formation of mineral deposits on the inner surface of the kettle. This finding is consistent with previous studies that showed the roughness of PP surfaces increased substantially during exposure to tap water and synthetic drinking water41.

The release of NPs and MPs from kettles under normal use conditions is influenced by several factors, including the number of uses, water hardness, and the material properties of the kettle. The surface of new kettles exhibited a distinct texture, with particles likely adhering loosely to the surface. Consequently, the concentration of NPs and MPs released from the kettle decreased significantly during the first ten boils and finally stabilized after about 50 to 150 boils. In addition, tap water contains ions which may form a passivation layer in the internal surface of the kettle14. This passivation layer acts as a protective barrier, covering the surface with scale or reducing the release of NPs by trapping the released particles in the mineral precipitate. This study enhances our understanding of the release mechanisms of NPs and MPs from kettles by analyzing the inner surface of the kettles and the release of NPs and MPs.

Implications of the Study

This study provides evidence that PP plastic kettles can contribute to daily human exposure to NPs and MPs. The findings demonstrate that new plastic kettles can release substantial concentrations of NPs and MPs into water during boiling, exposing consumers to plastic particles in the <10 μm size range. While the release (expressed as µg/cm2) significantly decreased with repeated use, both NPs and MPs were still detected following 150 boil cycles, indicating a continuous, albeit reduced, release over time. The small size and high bioavailability of NPs raises concerns about prolonged exposure17,18,19,20,22,23,24,25. Importantly, the study confirmed that tap water (hard water) reduced the amount of NPs compared to MilliQ water, suggesting that water chemistry, including factors such as mineral content, plays a key role in influencing NP and MP release dynamics. This may occur through mechanisms such as particle stabilization, deposition, or interaction with water constituents. Understanding this interplay is vital for assessing exposure risks across diverse geographical regions and water-quality conditions. Future research should systematically investigate how water quality parameters (e.g., hardness, pH, mineral content) affect plastic degradation and particle release.

A key methodological advancement of this study was the use of a novel combination of AF4-MALS and Pyr-GC-MS/MS. This integrated approach enabled the first confirmed detection and characterization of PP NPs released from plastic kettles. These findings provide a robust analytical framework for future studies seeking to identify and quantify released NPs in other consumer products.

The results of this study highlight practical opportunities to reduce NP and MP exposure from plastic kettles. Discarding the first few boils, already recommended by certain manufacturers, can significantly reduce early-stage particle release, particularly when kettles are new, thereby lowering the amount/number of particles ingested. However, many consumers may overlook or skip this step, underscoring the need for clearer communication in product labelling and instructions. While simple rinsing before first use is common, it does not achieve the same level of removal as repeated cycles of boiling and discarding. From a manufacturing perspective, alternative designs incorporating more glass or stainless-steel components and improved polymer formulations could further minimize particle release during normal use. While the study was designed to characterize NP and MP release under controlled and varied conditions, the tap water measurements from later boil cycles (Fig. 5 are particularly relevant for potential exposure assessment, as they reflect more typical consumer use. Although quantitative exposure risk assessment was not the primary aim, these later-cycle results can be directly utilized by regulatory bodies and risk assessors.

Given the widespread reliance on kettles for boiling water, it is important to extend investigations beyond the specific models tested here. Future research should prioritize: (1) evaluating other kettle designs/brands/types and materials, to identify options with lower NP and MP release, (2) expanding studies to other commonly used household appliances in contact with hot water or food, to determine whether they represent more significant or comparable particle sources, (3) assessing the influence of varying usage patterns (e.g., repeated boiling cycles, water chemistry, product age) on particle release. By identifying plastic kettles as a source of NPs and MPs, this study adds to the understanding of how the use of consumer products can contribute to NP and MP exposure. The practical recommendations and research directions outlined here can help inform design improvements, consumer choices, and future investigations aimed at reducing human exposure from everyday items.

Methods

Chemical and materials

Whatman glass fibre filters with diameter of 47 mm and pore sizes of 0.3 μm were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA), and glass fiber membrane filters (21 mm, 1 μm) were purchased from Advantec Co., Ltd. (Japan). Ultrapure water from a MilliQ system (Millipore, 0.22 μm filtered, 18.2 MΩ cm−1, Bedford, USA) was additionally filtered with 0.3 μm pore size glass fibre filter (47 mm) before use and is referred to as MilliQ water in this study. Acetone and dichloromethane (DCM) of liquid chromatography grade were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Plastics calibration standard-low set (MPCS-L) in SiO2 diluent powder was purchased from Frontier labs, Japan. This calibration standard allows the creation of calibration curves for the quantification of NPs and MPs. The standard comprised 12 polymers: polystyrene (PS), PE, polycarbonate (PC), PP, poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), Nylon 6, Nylon 66, styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR), acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene resin (ABS), polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polyurethane (PU), however in this study PP was the only polymer type measured. We should point out that no other plastic polymer types apart from PP were identified when the plastic materials of the investigated kettles or the leachates from the boiling cycles were analysed (see section on the Release and extraction of NPs and MPs). Deuterated polystyrene (d5-PS, powder) internal standard was provided by Polymer Source, Inc. (Dorval, Canada). Analytical reference materials of polyethylene (PE) (low-density polyethylene, referred to as PE in this study) (CAS 9002-88-4, 500 µm) was purchased from Alfa Aesar (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) while polypropylene (PP, isotactic (EP341R), powder, 20–120 µm) was donated by LyondellBasell (Melbourne, Australia). A dispersion of polystyrene (PS) NPs particles (nominal sizes 95, and 700 nm) and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) NPs particles (nominal sizes 110, and 700 nm) were purchased from the Bangs Laboratories, Inc. (Indiana, USA). All chemicals, including reagents and solvents, were obtained in glass bottles and used as received without further purification.

Release and extraction of NPs and MPs

From October 2023 to April 2024, 8 new polypropylene (PP) plastic kettles from different manufactures and typical of those used in Australian households were purchased from two different national supermarket chains in Brisbane, Australia. Five of the kettles were bought from supermarket chain ‘A’ and was labelled as ‘Kettle brand A’ (#ID 1 - 5) while the other three kettles were bought from supermarket chain ‘B’ and was labelled as ‘Kettle brand B’ (#ID 6 - 8). Although sourced from different brands, the two kettle models featured nearly identical internal geometries, characterized by a base diameter of 15.5 cm and a consistent internal height profile. For the release kinetics experiments, triplicates from ‘Kettle brand A’ (ID #1 - 3) and ‘Kettle brand B’ (ID #6 - 8) were filled with 1.1 L of MilliQ water (approximately 25 °C), which was measured using a graduated cylinder. Additionally, kettles from ‘Kettle brand A’ (ID #4 - 5) were filled with tap water (approximately 25 °C) to compare the effects of hard versus MilliQ water on particle release. All the kettles were marked as PP and had a volume capacity of 1.7 L. Consequently, the wetted inner surface area of the polypropylene plastic, calculated based on the consistent geometry and fill volume, was determined to be 472.34 cm2 for both kettle types under the experimental conditions. The kettles (ID 1 - 8) were bought while stored or packaged in paper boxes and transported to the laboratory for analysis. The specific model number and details of the kettles used in this study are not included as we wanted to de-identify the products.

Prior to the particle release experiments, all the newly purchased kettles (i.e., all internal surfaces) were washed three times with 600 mL of MilliQ water, and the water was discarded. The MilliQ water was swirled to coat the entire sample surface and rapidly poured out to remove interference particles caused by dust and residues, as well as to eliminate potential NPs and MPs that might have arisen during manufacturing, processing, and transportation. Figure 7 shows the release experiments and separation procedures of NPs and MPs in kettles. The kettles (triplicates from ‘Kettle brand A’ and ‘Kettle brand B’, respectively) were filled with 1.1 L of MilliQ water (approximately 25 °C), which was at least 65% of the volume of the kettle and then boiled at 150 time points. After the first boil, the boiled water was collected as the ‘1 time point’ sample. The kettle was then refilled with fresh MilliQ water, boiled again, and this second batch of boiled water was discarded. To ensure consistent initial conditions for every boil and to prevent the effect of residual heat, the kettle was allowed to cool down to room temperature after each boiling cycle before the subsequent one was initiated. Samples were collected only after specific cumulative boil numbers, namely 1, 3, 5, 10, 25, 50, 75, 100, and 150. This procedure was designed to assess the release of particles over repeated use. After boiling and the automatic shutdown of the kettles, the hot boiled water (all at 100 °C, monitored with a thermometer) was immediately transferred to a glass beaker to cool down at room temperature while covered with a glass lid and then extracted for NPs and MPs. It should be noted that the boiled water collected between the points tested were discarded. To account for any potential contamination during the sample preparation and extraction processes, triplicates 1.0 L of Milli Q water was placed in a glass beaker with a glass cover and was boiled on a hotplate. The water was boiled to 100 °C (as measured for the kettle release experiments) and then cooled down at room temperature while covered. This is referred to as the ‘MilliQ water Blank’ experiment and represents the average of three measurements. The blank samples underwent the same pre-treatment, concentration, and analysis as the real samples. The blank data was subtracted from the plastic kettle release experiment samples and captured any plastic particles in the MilliQ water and from sample handling.

The schematic covers details of boiling, NPs and MPs collection, and characterization. SEM: scanning electron microscopy; NTA: nanoparticle tracking analysis; TEM: Transmission electron microscopy; AF4-MALS: Asymmetrical Flow Field-Flow Fractionation Multiple Angle Light Scattering. Created in BioRender. Shi, K. (2025) https://BioRender.com/2pba2sy.

The plastic material from the kettles used in this study were sampled to characterized and identify their polymer composition and content using Pyr-GC/MS. Small (~1 mg) slivers of each container materials and lids were collected with a precleaned (DCM) scalpel in duplicate subsamples. The subsamples were added to pyrolysis cups, spiked with 0.02 µg of d5-PS internal standard, and analysed with Pyr-GC/MS for polymer identification. The results from the plastic material analysis for all the kettles were found to match PP. Hence, the main polymer of focused in this study was PP.

The extraction methods for NPs and MPs have been described in our previous studies42,43. The collected leachate samples were filtered by negative pressure filtration using a 1 µm pore size glass filter to collect MPs and separate NPs before analysis. The sample holding beakers were rinsed 3 times with MilliQ water and added to the filtering apparatus to make sure all adhered particles were transferred. For MPs, the 1 µm filters were securely wrapped in pre-furnaced aluminum foil and were dried in an Orbital incubator at 60 °C to a constant weight for 24 h. For analysis, the dried filters were then carefully rolled and loaded into 80 µL pyrolysis cups (Eco-Cup LF, Frontier Labs). The cups were covered with aluminum foil and placed on a hot plate at 60 °C for 3 h to remove residual water from the filters. Before Pyr-GC/MS analysis, the cups were spiked with 5 µL of a 0.02 mg/mL d5-PS internal standard solution. The cups were placed onto the autosampler of the Pyr-GC/MS system for analysis for PP polymer concentrations according to previously reported methods43,44,45.

For NPs, the filtrate water (<1 µm) was concentrated using a 200 mL Amicon® Stirred Cell ultrafiltration system with a 100 kDa, approximately 10 nm, poly (ether sulfone) membrane (Merck, Australia). The detailed steps for the Amicon® Stirred Cell concentration method can be found in our previously published studies29,46. Briefly, a nitrogen pressure of 75 psi was applied to drive the samples through the membranes. The concentrated NPs in the retentate were carefully transferred into glass tubes, and the sample (10 ± 2 mL) was subsequently freeze-dried to obtain a nanoparticle powder. To ensure all adhered particles were transferred, the collection flask from the filtering apparatus and the inside of the filtrate collection bottles as well as Amicon® Stirred Cell were washed and rinsed three times with MilliQ water. DCM (2 mL) was added to this powder, and the final suspension (after sonication and vortex-mixing for 30 to 40 mins to resuspend) was transferred multiple times through repeat aliquots of 80 µL into a pyrolysis cup (covered with aluminum foil and placed on a hot plate at <45 °C to evaporate off the DCM). The cup was then placed on a heating plate maintained below 50 °C to evaporate the DCM, preparing the sample for subsequent Pyr-GC/MS. It should be noted that any possible agglomerated NPs filtered out by the first step of membrane filtration (>1 µm) or adsorbed on possible large particles like MPs in the water samples were generally considered MPs and were excluded from the downstream analysis. Similarly, the membrane filtration procedures for the sample might retain aggregated or agglomerated particles, potentially leading to an underestimation of NP concentrations.

Pyrolysis Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry Analysis

The analysis of the mass concentrations of PP particles released from the plastic kettles by Pyr-GC/MS was conducted using a multi-shot micro-furnace pyrolyzer EGA/PY-3030D with an auto-shot Sampler (AS-1020E) from Frontier Laboratories (Fukushima, Japan), coupled to a Shimadzu GC/MS-QP2010-Plus (Shimadzu Corporation, Japan) and an Ultra Alloy 5 capillary column (30 m, 0.25 mm I.D., 0.25 μm film thickness). We note that Pyr-GC/MS was employed to quantify the particle mass concentration, while a combination of Pyr-GC-MS/MS and asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation coupled with multi-angle light scattering (AF4-MALS) was used for the characterization of nanoparticles. Supplementary Table 3 and 4 provides a summary of the typical experimental parameters used for Pyr-GC/MS and Pyr-GC-MS/MS. The pyrolysis was performed using the parameters reported previously43,45,47 with a double-shot mode: the first pyrolysis shot temperature of 100° to 300 °C and pyrolysis temperature of 650 °C for 0.2 min45. Samples were injected into the Ultra Alloy 5 capillary column using a 5:1 split ratio, and data were collected in full scan mode with a mass range of m/z 40-600. 2,4-dimethyl-1-heptene (m/z 126, 70, RT at 4.98 min), was the major pyrolysis product of PP and was monitored for identification and quantification43,45,48,49,50.

Nanoparticle Characterization

Based on the release kinetics, no significant difference was observed in the release of NPs between the two kettle brands. Particle characterization was therefore performed on water from the brand A kettle. For each sample all measurements were performed in triplicate. The particle size distribution, count concentration, and morphology of the released nanoparticles (10–1000 nm) were analyzed using the Microtrac Sync 5000 system, equipped with the FlowSync (wet) module (Microtrac Retsch GmbH, Haan/Duesseldorf, Germany). Additionally, nanoparticle size distribution and count concentration were assessed using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) with a Nanosight NS300 (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Malvern, UK), with each sample recorded three times for 60 seconds. To further examine the morphology of the released nanoparticles, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) were employed. The inner surface morphology of the kettles used in the release experiments was also analyzed using an Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) (Bruker Dimension Icon XR, Germany) and SEM.

Microtrac Sync Analysis

The particle size distribution, count concentration and shape of the released nanoparticles (particles 10–1000 nm) were characterized using the Microtrac Sync 5000 system, which includes the FlowSync (wet) module (Microtrac Retsch GmbH, Haan/Duesseldorf, Germany), employing laser diffraction and dynamic image analysis with a high-resolution camera. A 50 mL sub-sample of the concentrated water was loaded into the FlowSync analyzer using a micropipette to achieve a loading factor of 0.0255–0.0049. The system (wet) was set to a 25% flow rate with each run lasted 180 seconds. The system was rinsed and re-reaerated before the introduction of subsequent samples. Prior to analyses the instrument was calibrated with 200 nm PS standard. The average of three measurements was calculated. The particle size had an upper limit of 2000 μm and a lower limit of 0.0107 μm. Particle size parameters D10, D50 and D90 were measured, representing the 10%, 50% and 90% points of the cumulative undersize particle size distribution. The span of the distribution was calculated according to the following formula1.

Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis

The particle size distribution and count concentration of the released nanoparticles (10–1000 nm) was characterized by NTA with a Nanosight NS300 (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Malvern, UK). Prior to analyses, the NTA instrument was calibrated using standard 200 nm PS NPs diluted in MilliQ water (at 0.5 μg/mL) (Supplementary Table 5and Supplementary Figure 10). The nanoparticle count concentration was approximately 1.14 × 108 particles/mL, based on the density of PS, which is 1.05 g/cm3. The samples were analysed to achieve a particle count of 4.63 × 108 particles/mL and mean size of 169.1 ± 10.4 nm. For analysis of samples, 1 mL sub-sample of the concentrated water was introduced into the optical viewing cell, and the camera recorded at 25 frames per second, producing a video file of the particles exhibiting Brownian motion. Each sample was recorded three times with a capturing time of 60 seconds.

Scanning Electron Microscopy

The morphology of the released nanoparticles (10-1000 nm) was determined with scanning electron microscope (SEM, JEOL-7100F, JEOL Ltd., Japan). The sample (100 μL sub-sample of the concentrated water) was carefully drop-cast onto silicon wafers. Silicon wafers were first washed with ethanol to render the surface hydrophilic, and only 10 μL of leachate was drop-casted at a time to avoid the so-called coffee ring effect during the drying of the leachate. After vacuum drying overnight, the sample surface was sputter-coated with a 15 nm layer of platinum using the Quorum tech Q150-TS coater to conduct electrons. Particle sizes were estimated using the ImageJ analysis software. Images were taken at various magnifications with a working distance of 3.5 mm and an accelerating voltage at 3 kV.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Images were acquired using a Hitachi HT7700 B transmission electron microscope, equipped with a tungsten filament and operated at 100 kV and emission current of 10 uA, to obtain the morphological information of the nanoparticles. The samples were prepared by drop-casting approximately 100 μL sub-sample of the concentrated water onto a 3 mm carbon-coated TEM grid using a glass pipette and dried at room temperature.

Characterization of the inner surface of kettles with SEM and AFM

The morphology of the inner surface of the kettles used in the release experiment (i.e., that of a new kettle compared with boiled 150 for MilliQ water and boiled 100 for tap water) was observed with a SEM (SEM, JEOL-7800F, JEOL Ltd., Japan) and an atomic force microscopy (AFM, Bruker Dimension Icon XR, Germany). SEM was performed with an acceleration voltage of 3 kV. To obtain three-dimensional topography of kettle surface the AFM characterization was performed by scanning a 10 μm × 10 μm area using the ScanAsyst-Air probe, and the results were analyzed using NanoScope Analysis software.

Asymmetrical Flow Field-Flow Fractionation

Particle size distribution of the released nanoparticles (< 1 µm) and their separation was performed by asymmetrical flow-field-flow fractionation multi angle light scattering (AF4-MALS), which included a long channel (LC) frit inlet connected to an Eclipse Dualtec - system equipped with an Optilab and DAWN unit (Wyatt Technology Corporation Wyatt) and a fraction collector. An aliquot of the stirred cell concentrated water sample (100 µL) was injected for analysis, and fractions (~0.5 mL) collected every min at the highest point of each detected peak in glass collection vessels using a Shimadzu FRC-40 controlled Realtime Analysis LabSolutions. The collected fractions were then transferred to 1.5 mL amber glass vials, with the original fractionation vessels being rinsed with 0.5 mL of filtered MilliQ water and added to the amber vials to facilitate transfer of particles captured. The collected samples were then analyzed by Pyr-GC-MS/MS (Supplementary Table 4) by aliquoting 80 µL of the sample to a cup and evaporating to dryness. The AF4-MALS was calibrated using a dispersion of PS NPs particles (nominal sizes 20, 80, 200, 500, and 900 nm) as shown in Supplementary Figure 9. Like the nanoparticle characterization section, water from the brand A kettle was characterized using AF4-MALS with fraction collection and subsequent Pyr-GC-MS/MS analysis of the fractions.

Detail AF4-MALS operation

Size separation and recording was performed on an in-house Wyatt system with a Shimadzu UV detector, which included a long channel (LC) frit inlet connected to an Eclipse Dualtec asymmetrical flow-field-flow fractionation multiple angle light scattering (AF4-MALS) system equipped with an Optilab and DAWN unit. The channel was fitted with a 10 kDa polyethersulfone (PES) membrane (Part no. 165668-10-C, Wyatt Technology Corporation, California, USA) and a 250 µm mylar spacer (Part no. 165688-250 W, Wyatt Technology Corporation, California, USA). 0.3 µm glass fiber filtered (GFF) (SKU GF7547MM, Advantec MFS Inc., California, USA) MilliQ water acted as the system solvent, with 45 mg of NaNO3 added to every 1 L of solvent as an antimicrobial. 20% MeOH was employed as a needle rinse solution. Solvent flow was provided by a Shimadzu LC-20AD, while the Shimadzu SIL-20AC autosampler housed and injected each sample as the analysis was performed. The system parameters for the developed separation procedure were established within the Voyager DS software (v2.0.2.9, Wyatt Technology Corporation, California, USA) and communicated to the attached devices through the Shimadzu CBM-20A unit. An FRC-40 Shimadzu unit controlled by Realtime Analysis LabSolutions (v5.117, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) was used to collect the fractionated sample sizes exiting the AF4 system. Data cleaning and particle size analysis of the detected particles utilizing a combination of the sphere and radius of hydration calculation models within ASTRA 8 software (v8.0.0.19, Wyatt Technology Corporation, California, USA).

100 µL of each sample was injected for analysis and fractionation, with the applied Voyager methodology (summarized within Supplementary Table 6) consisting of a short injection and focusing step at the channels front, before applying an exponential decrease in cross flow within the system from 0.7 mL/min to 0.12 mL/min over a period of 60 mins to elicit particle size separation. Particles were carried through the system by a constant detector flow of 0.5 mL/min. 1 min fractions (~0.5 mL) were collected at the highest point of each detected peak within glass fraction vessels using a Shimadzu FRC-40 controlled Realtime Analysis LabSolutions (v5.117, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) software for particle identification purposes. The collected fractions were then transferred to 1.5 mL amber glass vials, with the original fractionation vessels being rinsed with 0.5 mL of filtered MilliQ water and added to the amber vials to facilitate the near complete transfer of particles captured.

Polystyrene (PS) nanospheres of 20 nm (Cat No. 3020 A, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA), 80 nm (Cat No. 3080 A, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA), and 200 nm (Cat No. 3200 A, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) sizes were utilized for method development. These standards were ran as additional checks among the runs to monitor system integrity and ensure the detectors were accurately recording the separation and sizes of particles present. In cases where particle size calculations could not be accurately determined, relation of the individual eluting peaks to these reference standard sizes were performed to provide a rough estimation on predicted particles size ranges.

Release per cm2 calculation

To determine the amount plastic particle release during the boiling experiments, we normalized the measured concentration values (µg/L) to amount released per cm2. This was achieved by first converting the concentration to total mass released per boil by multiplying by the water volume used in each experiment (1.1 L/boil). The resulting mass was then divided by the total internal surface area of the kettle in contact with water (472.34 cm2). This approach allowed normalization for surface area and enabled direct comparison of PP release across different boiling cycles. Because analyses were performed in triplicate for both kettle brands, A and B, this method also ensured consistent geometry and contact area, thus isolating the effect of repeated boiling on particle release. The calculated release (µg/cm2) provided a quantitative basis for comparing the dynamics of plastic particle release over time. The values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), calculated from three independent replicates.

The inner surface area of 472.34 cm2 was determined as a simplified geometric estimate based on the kettle’s internal dimensions when filled with 1.1 L of water, effectively approximating it to a cylindrical shape. This calculation represents the total area of the PP surfaces in contact with the water. The internal structure of the kettles was smooth, without significant protrusions, thus validating the use of this simplified model. Furthermore, although a metal heating element is present at the bottom, it is not a plate that covers the entire base. Therefore, no area was subtracted for the heater.

First order kinetics model

The mass concentration data for PP NPs and MPs were fitted using first order kinetic model - single exponential decay function via Origin. The data was fitted using an exponential decay model using the model equation:

Where (y) is the mass concentrations of NPs or MPs, (x) is the number of boils (time), (A1) is the initial amplitude, (t1) is the decay constant at which the concentration decreases, (y0) is the offset.

Recovery of spiked nanoplastic and microplastic particles in MilliQ water

To confirm the reliability of the method for extracting NPs and MPs, recovery tests were conducted using PS (nominal sizes 95 and 700 nm) and PMMA (nominal sizes 110 and 700 nm) NPs (4.5–15.3 µg/L) and PP (20-120 µm powder) and PE (500 µm powder) MPs (8.9–20.2 µg/L) (Supplementary Table 1 and 2). The reference standards and sizes were employed as near to representative as possible to represent the target NPs and MPs and sizes and for evaluating their recoveries. This said, we should note that while the NP recovery rates of the proposed method were assessed using commercial PS and PMMA NPs, these rates might differ for PP NPs. However, analytical standards for many nanosized polymer types are not yet commercially available. Three MilliQ water samples were simultaneously spiked with MPs (PE, PP) and NPs (PS, PMMA) and put through filtering and stirred cell concentration using the same procedure as described above and prepared for Pyr-GC/MS analysis. Additionally, three MilliQ water samples without particles spiking were analyzed as blank samples following the same procedures.

Recovery rates were calculated using the following equation:

where C0 (μg/L) is mass concentration of NPs and MPs in the control samples (un-spiked samples) and C2 (μg/L) is mass concentration of NPs and MPs detected in samples spiked with a known concentration C1 (μg/L).

Quality Assurance and Quality Control (QA/QC)

To minimize the risk of airborne NPs and MPs contamination, all sample treatment was carried out in a clean fume hood with samples covered with pre-cleaned (with DCM) aluminum foil when not being processed. Cotton laboratory coats and nitrile gloves were worn continuously during the experiment to ensure that external contamination was prevented. Working areas and surfaces were wiped with 70% ethanol before use. All glassware (e.g., beakers, vials, forceps) were thoroughly rinsed with DCM before use. To avoid plastic contamination from the ultrafiltration membrane, prior to use, all the membranes were washed and soaked in filtered MilliQ water. Similarly, to prevent contamination before and in between treatment of different samples, the Amicon® Stirred Cell and its assembling parts were thoroughly washed three times with filtered MilliQ water and dried upside-down in a fume hood on a pre-cleaned (DCM rinse) aluminum foil (wrapped). Before conducting Pyr-GC/MS analysis, a system clean was performed to verify the absence of plastic contamination in the system. All pyrolysis cups used in this study were new and were cleaned with DCM prior to sample addition. Target plastic (PP) was either not detected or below detection limits in all blank samples analyzed (Supplementary Tables 7 and 8).

Limits of detection and quantification

Instrumental calibration was achieved through the injection of 8-point calibration standard, covering concentrations ranging from 0.003 to 161 μg/cup for the target plastics, with regression coefficients (R2) of the calibration curves equal to or >0.95. Calibration curves were constructed by plotting the peak area ratio of the selected indicator ions to the d5-PS internal standard ion (d5-PS-monomer) against the concentration of target plastic, utilizing the integration results for quantification. d5-PS served as the internal standard for all target plastics. Consequently, all mass concentration values reported in this study were adjusted for the recovery of the d5-PS internal standard spiked into the samples before Pyr-GC/MS. Method detection limits (MDLs) for PP were calculated from concentrations observed in blanks as the mean concentration plus 3 times the standard deviation (Supplementary Table 7 and 8). In instances where PP was not detected, MDLs were calculated as the lowest concentration of a peak with a signal-to-noise ratio of 10:1. Before further processing, all data underwent blank subtraction.

Data availability

References

Wen, J. et al. Environmentally Relevant Concentrations of Microplastic Exposure Cause Cholestasis and Bile Acid Metabolism Dysregulation through a Gut-Liver Loop in Mice. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 1832–1841 (2024).

Okoffo, E. D., Tscharke, B. J. & Thomas, K. V. Release of Micro- and Nanosized Particles from Plastic Articles during Mechanical Dishwashing. ACS EST Water 5(6), 2870–2881 (2025).

Yadav, H. et al. Cutting Boards: An Overlooked Source of Microplastics in Human Food?. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57(22), 8225–8235 (2023).

Hernandez, L. M. et al. Plastic Teabags Release Billions of Microparticles and Nanoparticles into Tea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53(21), 12300–12310 (2019).

Li, D. et al. Microplastic release from the degradation of polypropylene feeding bottles during infant formula preparation. Nat. Food 1(11), 746–754 (2020).

Ragusa, A. et al. Raman microspectroscopy detection and characterisation of microplastics in human breastmilk. Polymers 14(13), 2700–2714 (2022).

Pironti, C. et al. First Evidence of Microplastics in Human Urine, a Preliminary Study of Intake in the Human Body. Toxics 11(1), 40 (2022).

Schwabl, P. et al. Detection of Various Microplastics in Human Stool. Ann. Intern. Med. 171(7), 453–457 (2019).

Ragusa, A. et al. Plasticenta: First evidence of microplastics in human placenta. Environ. Int 146, 106274 (2021).

Amato-Lourenco, L. F. et al. Presence of airborne microplastics in human lung tissue. J. Hazard. Mater. 416, 126124–126130 (2021).

Horvatits, T. et al. Microplastics detected in cirrhotic liver tissue. EBioMedicine 82, 104147 (2022).

Xu, J.-L., Wright, S., Rauert, C. & Thomas, K. V. Are microplastics bad for your health? More rigorous science is needed. Nature 639(8054), 300–302 (2025).

Durand, A., Hirzel, S., Rohde, C., Gebele, M., Lopes, C., Olsson, E. & Barkhausen, R. Electric Kettles: An Assessment of Energy-Saving Potentials for Policy Making in the European Union. Sustainability 14(20), 12963, (2022).

Shi, Y. et al. The influence of drinking water constituents on the level of microplastic release from plastic kettles. J. Hazard Mater. 425, 127997 (2022).

Sturm, M. T., Kluczka, S., Wilde, A. & Schuhen, K. Determination of particles produced during boiling in differenz plastic and glass kettles via comparative dynamic image analysis using FlowCam®. Analytik NEWS. https://analytik.news/en/papers/2019/8.html (assessed on 23/01/2025) (2019).

Yang, L., Kang, S., Luo, X. & Wang, Z. Microplastics in drinking water: A review on methods, occurrence, sources, and potential risks assessment. Environ. Pollut. 348, 123857 (2024).

Wei, W. et al. Anionic nanoplastic exposure induces endothelial leakiness. Nat. Commun. 13(1), 4757–4771 (2022).

Lin, S. et al. Metabolomics Reveal Nanoplastic-Induced Mitochondrial Damage in Human Liver and Lung Cells. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56(17), 12483–12493 (2022).

Schirinzi, G. F. et al. Cytotoxic effects of commonly used nanomaterials and microplastics on cerebral and epithelial human cells. Environ. Res. 159, 579–587 (2017).

Brown, D. M., Wilson, M. R., MacNee, W., Stone, V. & Donaldson, K. Size-Dependent Proinflammatory Effects of Ultrafine Polystyrene Particles: A Role for Surface Area and Oxidative Stress in the Enhanced Activity of Ultrafines. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 175(3), 191–199 (2001).

Marfella, R. et al. Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Atheromas and Cardiovascular Events. N. Engl. J. Med. 390(10), 900–910 (2024).

Zhu, X. et al. Micro- and nanoplastics: A new cardiovascular risk factor?. Environ. Int 171, 107662 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. Microplastics in infant milk powder. Environ. Pollut. 323, 121225 (2023).

Prata, J. C., da Costa, J. P., Lopes, I., Duarte, A. C. & Rocha-Santos, T. Environmental exposure to microplastics: An overview on possible human health effects. Sci. Total Environ. 702, 134455 (2020).

Kannan, K. & Vimalkumar, K. A Review of Human Exposure to Microplastics and Insights Into Microplastics as Obesogens. Front Endocrinol. ((Lausanne)) 12, 724989 (2021).

World Health Organization. Dietary and inhalation exposure to nano- and microplastic particles and potential implications for human health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. Licence: CC BY- NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240054608; 2022.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Generation Plastic: Unpacking the Impact of Plastic on Children. UNICEF, New York, November 2024. https://ceh.unicef.org/events-and-resources/knowledge-library/generation-plastic-unpacking-impact-plastic-children; 2024.

Xu, J.-L., Lin, X., Wang, J. J. & Gowen, A. A. A review of potential human health impacts of micro- and nanoplastics exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 851, 158111 (2022).

Okoffo, E. D. & Thomas, K. V. Quantitative analysis of nanoplastics in environmental and potable waters by pyrolysis-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Hazard. Mater. 464, 133013–133024 (2024).

Xu, Y. et al. Assessing the mass concentration of microplastics and nanoplastics in wastewater treatment plants by pyrolysis gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57(8), 3114–3123 (2023).

Das, A., Terry, L. R., Sanders, S., Yang, L. & Guo, H. Confocal Surface-Enhanced Raman Imaging of the Intestinal Barrier Crossing Behavior of Model Nanoplastics in Daphnia Magna. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 11615–11624 (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Identification of Poly(ethylene terephthalate) Nanoplastics in Commercially Bottled Drinking Water Using Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57(22), 8365–8372 (2023).

Vestad, B. et al. Size and concentration analyses of extracellular vesicles by nanoparticle tracking analysis: a variation study. J. Extracell. Vesicles 6(1), 1344087 (2017).

Schimek, A.; Strebl, M.; Blech, M.; Garidel, P., Challenges at Submicron Particle Characterisation: A Case Study Using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA). Journal of Pharmaceutical Innovation 2024, 19, (3).

Huber, M. J. et al. Physicochemical characterization and quantification of nanoplastics: applicability, limitations and complementarity of batch and fractionation methods. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 415(15), 3007–3031 (2023).

Bachurski, D. et al. E., Extracellular vesicle measurements with nanoparticle tracking analysis - An accuracy and repeatability comparison between NanoSight NS300 and ZetaView. J. Extracell. Vesicles 8(1), 1596016 (2019).

Wells, M. J. M. et al. Multi-laser nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA): A unique method to visualize dynamic (shear) and dynamic (Brownian motion) light scattering and quantify nonliving natural organic matter (NNOM) in environmental water. Sci. Total Environ. 949, 174985 (2024).

Li, H., Lee, L. M., Yu, D., Chan, S. H. & Li, A. An optimized multi-technique based analytical platform for identification, characterization and quantification of nanoplastics in water. Talanta 272, 125800 (2024).

Li, H., Lee, L. M., Yu, D., Chan, S. H. & Li, A. An optimized multi-technique based analytical platform for identification, characterization and quantification of nanoplastics in water. Talanta 272, 125800–125807 (2024).

Li, L. et al. New insight into scale inhibition during tea brewing: Ca2+/Mg2+ complexing and alkalinity consumption. J. Environ. Sci. 124, 901–914 (2023).

Shi, Y. et al. Real-world natural passivation phenomena can limit microplastic generation in water. Chem. Eng. J. 428, 132466 (2022).

Okoffo, E. D. & Thomas, K. V. Mass quantification of nanoplastics at wastewater treatment plants by pyrolysis–gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Water Res. 254, 121397 (2024).

Okoffo, E. D. & Thomas, K. V. Quantitative analysis of nanoplastics in environmental and potable waters by pyrolysis-gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J. Hazard. Mater. 464, 133013 (2024).

Okoffo, E. D., Chan, C. M., Rauert, C., Kaserzon, S. & Thomas, K. V. Identification and Quantification of Micro-Bioplastics in Environmental Samples by Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56(19), 13774–13785 (2022).

Okoffo, E. D. et al. Identification and quantification of selected plastics in biosolids by pressurized liquid extraction combined with double-shot pyrolysis gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Sci. Total Environ. 715, 136924 (2020).

Okoffo, E. D. & Thomas, K. V. Mass quantification of nanoplastics at wastewater treatment plants by pyrolysis-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Water Res. 254, 121397–121408 (2024).

Ribeiro, F. et al. Quantitative Analysis of Selected Plastics in High-Commercial-Value Australian Seafood by Pyrolysis Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54(15), 9408–9417 (2020).

Fischer, M. & Scholz-Böttcher, B. M. Simultaneous Trace Identification and Quantification of Common Types of Microplastics in Environmental Samples by Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51(9), 5052–5060 (2017).

Rauert, C., Pan, Y., Okoffo, E. D., O’Brien, J. W. & Thomas, K. V. Extraction and Pyrolysis-GC-MS analysis of polyethylene in samples with medium to high lipid content. J. Environ. Exposure Assess. 1(2), 13 (2022).

Tsuge, S.; Ohtani, H.; Watanabe, C., Pyrolysis-GC/MS data book of synthetic polymers: pyrograms, thermograms and MS of pyrolyzates. Elsevier: 2011.

Acknowledgements

The Queensland Alliance for Environmental Health Sciences, The University of Queensland, gratefully acknowledges the financial support of Queensland Health, Australia. We acknowledge the facilities and scientific and technical support from the Australian Microscopy & Microanalysis Research Facility at the Centre for Microscopy and Microanalysis (CMM) at The University of Queensland. We also acknowledge the support for the AFM imaging at The Australian National Fabrication Facility - Queensland Node (ANFF-QLD). This work was financially supported by the program of China Scholarship Council (202306120298). We also acknowledge the use of facilities (AF4-MALS with Pyr-GC-MS/MS), and scientific and technical support from Angus Bagley at the Minderoo Centre– Plastics and Human Health at The University of Queensland. EDO, CR and KVT are supported by the Australian Research Council (ARC) Training Centre for Hyphenated Analytical Separation Technologies (HyTECH) (IC220100035). Cassandra Rauert is supported by the Minderoo Foundation, an independent not for profit philanthropic organization. The authors acknowledge the use of facilities and technical support from Frontier Laboratories, Japan for most of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.S.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Data analysis, Methodology, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, revised manuscript. E.D.O.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Data analysis, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Writing - review & editing, Supervision. H.F.: Data analysis, Methodology. C.B.: Data curation, Data analysis. J.J.: Resources. C.R.: Methodology, Writing - review & editing. K.V.T.: Conceptualization, Resources, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, K., Okoffo, E.D., Fu, H. et al. Release of nanoplastic from polypropylene kettles. npj Emerg. Contam. 1, 16 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44454-025-00018-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44454-025-00018-w