Abstract

Sexual and gender minority (SGM) populations experience disproportionately high rates of depression, anxiety, stress, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) offers a promising method for capturing real-time fluctuations in these psychological states. This systematic review evaluated the feasibility, acceptability, and predictive utility of EMA for assessing mental health in SGM. We searched PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, CINAHL, and Cochrane Library databases and identified 11 studies from 815 records. Most studies reported high feasibility and moderate-to-high acceptability, although concerns about participant burden and privacy were noted. Studies identified dynamic predictors of poor mental health, such as discrimination, affective instability, and interpersonal conflict, as well as protective factors, including social support and gender affirmation. Three studies used predictive modeling, and two incorporated EMA into just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs). These findings suggest that EMA is feasible, with untapped potential for delivering responsive mental health care to SGM individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sexual and gender minorities (SGM) include, but are not limited to, those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, non-binary, and queer individuals experience disproportionately high rates of mental health challenges, such as anxiety, depression, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STBs)1,2,3. These disparities are largely shaped by stigma, discrimination, and rejection and are further compounded by structural inequities and barriers to care4,5. Family pressure to conform to heteronormativity, rigid gender norms, and societal stigma contribute to interpersonal conflict and emotional distress6,7,8,9,10. Structural barriers, such as legal restrictions, workplace discrimination, and limited institutional support, further exacerbate mental health disparities11. Daily experiences of microaggressions and cultural invalidation further increases vulnerability to stress, disordered eating, anxiety, depressive symptoms, and STBs12,13,14,15.

The dynamic and unpredictable nature of these stressors requires methods that can capture real-time fluctuations in mental health. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) enables repeated measurements of emotional and behavioral states in daily life, reducing recall bias and enhancing ecological validity16,17. Delivered through smartphone applications, online platforms or wearable devices, EMA can be used signal-contingent, event-contingent, or interval-based prompts. It also captures contextual factors, such as real-time environmental stressors, that may contribute to fluctuations in mental health, providing more robust data to strengthen causal inference17,18. Existing research has relied heavily on methodologies that require retrospective recall, which, in contrast, often overlooks rapid changes in psychological states. Therefore, EMA represents an innovative approach to capture real-time, contextually rich data necessary to understand dynamic and nuanced mental health experiences as they occur16,17.

Among SGM populations, the feasibility and acceptability of EMA may differ from those of the other groups. The minority stress theory posits that chronic exposure to stigma and identity concealment creates distinctive psychological burdens that may influence both engagement with intensive assessments and types of predictors of EMA identifies19,20. Privacy concerns about disclosing sensitive experiences on a digital platform, as well as vigilance related to stigma, may also influence compliance21,22,23. Simultaneously, EMA could be particularly valuable for SGM, as it can capture rapid shifts in distress following discriminatory encounters or interpersonal rejection events that retrospective methods often miss or underestimate24,25.

Despite the growing use of EMA in mental health research, its application among SGM remains limited. While EMA has been applied across diverse populations, existing reviews have either focused on behavioral outcomes in SGM, such as substance use and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men26, or on mental health symptoms in non-SGM populations, such as veterans and individuals with cancer27,28. These prior reviews were narrative or scoping in nature and did not provide systematic evaluations of EMA feasibility, acceptability, or predictive utility of mental health outcomes among SGMs.

This systematic review addresses this gap by synthesizing findings from EMA studies that assess mental health among SGM. Specifically, we sought to (1) evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of EMA for capturing psychological distress, including stress, depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors, and (2) identify predictors of these outcomes measured through EMA to inform the development of timely and contextually grounded mental health interventions for SGM.

Results

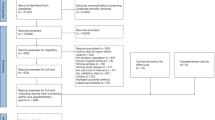

The initial search yielded 815 potentially qualifying records. After removing 63 duplicates, 752 titles and abstracts were screened. Of these, 671 records were excluded for not meeting eligibility criteria. The full texts of 81 studies were assessed, and 70 were excluded for reasons such as wrong population (k = 33), wrong outcomes (k = 20), no use of digital EMA (k = 10), and the absence of disaggregated SGM data (k = 7). Eleven studies met the inclusion criteria for this review (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of the included studies

The characteristics of the 11 included studies are summarized in Table 1. These studies were published between 2020 and 2025. Eight studies used observational designs, including four that evaluated the feasibility and acceptability of EMA protocols29,30,31,32, three that employed daily diary methods to track participants’ real-time experiences and affective mechanisms33,34,35, and one dyadic diary study of partnered sexual minority women36. Two studies used mixed-method designs that combined EMA and qualitative interviews37,38, with Sizemore et al.37 embedding EMA within an intervention framework. One of the studies used a qualitative design39. Sample sizes ranged from 16 to 321, and the participants’ ages ranged from 12 to 48 years.

Eight studies were conducted in the United States29,30,32,33,34,35,36,37, one each in Vietnam39, China31, and the United Kingdom38.

Recruitment strategies included clinical settings37,39, community-based recruitment outreach30,33,34, online platforms, such as social media platforms, mobile apps, research panels, targeted digital advertisements29,31,35,36,38, and a combination of in-person and online methods32.

Funding source

Eight of the included studies (72.7%) reported funding sources. Four studies were funded by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and four received support from foundations, international collaborators, or LGBTQ+ health-focused agencies and advocacy groups. Three studies did not report funding.

Major findings

EMA protocols

EMA study durations ranged from 7 days38,39 to 6 months32. Shorter monitoring periods (7–14 days) often used higher prompt frequencies (2 to 6 times per day), while longer studies deployed fewer daily prompts to reduce participant burden. Two studies incorporated 6–8 prompts per day to capture momentary experiences35,39.

Sampling strategies included signal-contingent (EMA prompts delivered at random or fixed times during the day)29,33,34,37,38, interval-contingent (assessments scheduled at regular, predetermined intervals, such as end-of-day)30,31,32,36, and mixed approaches35,39, which combined multiple sampling strategies such as interval- and signal-contingent, and in some cases included event-contingent assessments (initiated by participants in response to specific events, such as substance use or emotional distress). Most studies utilized smartphone apps or web-based platforms to deliver EMA prompts, with frequencies ranging from one to eight times per day. One study included the JITAI element37.

Mental health outcomes assessed

All studies examined state-based, momentary mental health outcomes including stress, depression, anxiety, and STBs. Six studies focused on STBs30,31,33,34,35,38. Depression and mood fluctuations were assessed in four studies29,31,32,33, anxiety in three29,30,38, and stress in five31,35,37,39. One study assessed disordered eating in the context of momentary stress and emotional dysregulation, aligning with the review’s focus on real-time mental health predictors36. The specific outcome measures and measurement tools used across studies are provided in Supplementary Data 1.

Feasibility of EMA

Feasibility was assessed in 10 of the 11 studies. Participant retention was high across studies, with full retention reported by Heron et al.36 and Williams et al.38 and minimal attrition noted in other studies. None of the studies reported difficulty with retention during the study period.

EMA prompt completion was the most frequently reported feasibility indicator (10 studies), with a mean completion rate of 76.1% ± 13.7%. Nine studies with durations between 7 and 30 days reported completion rates ranging from 61.8% to 97.3%29,30,31,33,34,35,36,38,39, whereas two studies lasting 90 days or more reported lower completion rates (56% and 66.19%)32,37. Higher completion rates were commonly reported in shorter-duration protocols using structured prompting schedules (2–6 fixed or randomly timed prompts per day)29,34,35,38. In contrast, mixed-sampling designs that incorporate participant-initiated or event-contingent assessments have shown greater variability in engagement35,39. Incentives were common, with eight studies providing performance-based bonuses for achieving completion thresholds31,32,33,35,36,37,38,39.

Feasibility was also reflected in the EMA protocol implementation support employed to sustain participation. Structured onboarding was common in all studies, involving in-person or virtual orientations, guided app installation, and practice surveys to enhance comfort with the protocol. Three studies monitored survey completion in real time and followed up with participants who missed daily EMA prompts via personalized reminders32,38 and weekly compliance updates with targeted coaching35. Technical support was also consistently provided to the study participants, usually via phone or email29,31,36,37.

Acceptability of EMA

Acceptability was assessed in three studies37,38,39. In the JITAI pilot study, participants rated the app above a priori benchmarks: System Usability Scale (M = 4.19/5, SD = 0.65), Information Quality (M = 2.98/3, SD = 0.08), and Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (M = 3.42/4, SD = 0.45). Participants also reported high perceived usefulness of EMA-based just-in-time messages and strong satisfaction with the intervention content37.

Exit interviews in other studies reflected themes related to perceived benefits (insight, self-monitoring) and burdens and concerns (emotional reactivity, repetition, and privacy concerns). Participants frequently described the EMA as helpful for insight and self-monitoring. For example, one participant noted, “It made me think and learn more,” “allowed me to better understand myself, my emotions as they really were.”37. At the same time, in two studies38,39, some participants described the frequency and repetition of prompts as burdensome or even triggering. In Trang et al.39, one participant mentioned “…you ask me to do too many surveys, I will get lazy and won’t want to do any more…I just completed a prompt, and since that time, nothing has changed. So, I won’t do the other survey”. Similarly, in Williams et al.38, participants acknowledged that daily self-harm questions sometimes heightened awareness of risk: “So I started to overanalyze my, essentially my emotions and everything… Yeah, well, it was triggering in that I felt like I had a bit of an impulse to do like, you know, bad things [self-harm]”. Concerns about others seeing participants answer sensitive questions were also noted, particularly when participants were in public or with family members.

Despite reporting some burdens, no adverse events were reported in any of these studies. All 11 studies included participant safeguarding protocols such as structured onboarding, access to crisis hotline information, and referral options for mental health services. In studies assessing suicidal thoughts and behavior30,31,33,34,38, EMA responses were monitored in real time, with protocols in place for escalation and clinical referrals when participants were at risk.

Predictors of mental health identified from EMA variables

Figure 2 summarizes the key predictors and protective factors of mental health identified by EMA across studies. Stress severity was predicted by alcohol- and drug-involved condomless anal sex, with higher stress among low-sensation seekers in three-level mixed-effects models of post-event periods35. Daily experiences of minority stressors, such as discrimination and identity invalidation, were also associated with greater same-day stress and anxiety in multilevel models36. Discrimination further predicted higher same-day depressed mood through two-level multilevel models in Livingston et al.29.

Identity invalidation and internalized homophobia predicted risk of suicidal ideation and non-suicidal self-injury through affective pathways in a multilevel structural equation model30. Real-time exposure to negative SGM-related media was associated with increased suicidal ideation, partly mediated by expectation of rejection in within-person path models34. Negative affect instability (such as fluctuations in sadness, irritability, happiness, and calmness) and daily stressors (such as rejection, invalidation, conflict, and discrimination) predicted next-day suicidal ideation, while better sleep quality reduced this risk in lagged multilevel analyses31. Machine learning models further demonstrated the feasibility of short-term risk prediction31.

Protective factors such as social support buffered against depressive symptoms and stabilized daily mood32. Resilience and affirming environments were associated with lower suicidal ideation33. Good sleep quality further predicted reduced next-day suicidal ideation in lagged and machine-learning analyses31.

EMA data for personalized intervention

Two studies demonstrated how EMA can inform or deliver adaptive interventions. One study incorporated a JITAI framework, triggering in-app support when participants reported stress, which they found helpful and responsive to their needs37. In another study with high-risk MSM in Vietnam, EMA data were used to inform the development of culturally sensitive mental health interventions tailored to participants’ lived experiences39.

Risk of bias

The results of the quality assessment of the included studies are provided in Supplementary Table 1. Among the eleven studies, six were rated as high quality29,30,31,32,35,39 and five as moderate quality33,34,36,37,38. None of the studies were rated as low-quality.

Among the quantitative descriptive studies (k = 8), most utilized validated mental health measures, EMA designs, or relevant sampling strategies. EMA adherence was reported in all but one study33. Two studies34,36 provided limited details on statistical modeling procedures and missing data handling, leading to reduced transparency in their analytical approaches. The remaining five studies met all MMAT criteria and were rated as high-quality.

The only qualitative study39 was rated as high-quality. The study employed a clearly defined design and appropriate data collection procedures, and presented illustrative participant quotes that supported the thematic findings. Although some aspects of the analytic process, such as coding procedures, reflexivity, and documentation of theme development, were not described in detail, which introduced initial uncertainty in the appraisal, the interpretations were sufficiently substantiated by the data, and the overall analysis demonstrated coherence and methodological transparency.

Two mixed-methods studies37,38 clearly justified the use of the mixed-methods approach and adequately interpreted the integrated findings. However, limitations were observed in the connection, joint interpretation, and the use of qualitative and quantitative data to draw cohesive conclusions. In Sizemore et al.37, the connection between qualitative themes and EMA data was not clearly explained. In Williams et al.38, inconsistencies between participant feedback and survey performance were described, but not fully reconciled.

Discussion

This systematic review synthesized evidence from 11 peer-reviewed studies that utilized EMA to assess mental health among SGM. EMA was found to be a generally feasible method for capturing real-time fluctuations in stress, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation, although adherence varied across studies. Higher adherence was observed in protocols with shorter durations and lower prompt frequencies, suggesting that participant burden may influence engagement31,34. Acceptability was assessed more inconsistently, with mixed findings among the studies that evaluated it. These findings are consistent with prior EMA studies conducted on the general population’s physical and mental health, which have emphasized the role of design features, such as user interface, prompt length, and timing, in optimizing compliance40,41,42.

Feasibility and acceptability were generally favorable, though highly dependent on contextual and design factors. The majority of the study sample consisted of younger participants (mean age <25 years) with moderate to high educational attainment and regular access to smartphones31,32,33. Studies with younger digitally literate participants reported smooth onboarding experiences, high completion rates34, and perceived benefits of EMA in promoting emotional reflection and self-awareness37,38. In contrast, studies involving individuals with intersecting vulnerabilities, including people living with HIV and from lower-income or migrant backgrounds, encountered challenges related to device access, privacy, and emotional fatigue37,39. In some cases, frequent prompts triggered distress, particularly when assessing self-harm or identity-related stressors, an issue previously noted in EMA research on high-risk populations43,44. These findings align with prior literature, highlighting that while EMA can empower marginalized groups by centering on their daily lived experiences, it may exacerbate disparities if issues of accessibility, digital literacy, and cultural safety are not addressed45,46. These findings reinforce the need for trauma-informed, user-centered EMA designs that balance intensity with psychological safety.

EMA designs varied considerably across studies. Most employed signal- or interval-contingent protocols are effective for capturing structured symptom dynamics but may overlook spontaneously occurring events. Only a few studies adopted event-contingent or hybrid designs, despite their potential to enhance ecological validity and sensitivity to momentary fluctuations. Prior work suggests that symptoms such as mood, anxiety, and suicidal ideation can shift rapidly and are not always tied to identifiable external events, making flexible EMA strategies especially valuable47,48,49,50. For SGMs who are disproportionately exposed to sudden, identity-related stressors such as microaggressions or rejection, rigid prompting schedules may miss critical experiences. Hybrid designs that incorporate both signal- and event-contingent elements may offer greater responsiveness to these fluctuations. Emerging EMA research in psychology has also increasingly supported hybrid designs to balance feasibility and flexibility51.

EMA studies identified a consistent set of key momentary predictors influencing mental health outcomes among SGM. Discrimination, identity invalidation, internalized homophobia, and exposure to negative SGM-related media were linked to heightened stress, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation, with daily fluctuations in negative affect further predicting next-day risk29,31,34,35,36. At the same time, family and social support, resilience, affirming environments, and good sleep quality buffered against these stressors, stabilizing mood and reducing the likelihood of suicidal ideation31,32,33. These insights show how the EMA can capture the dynamic interplay of risk and resilience in daily life, providing a temporal nuance to minority stress theory19 and suggesting its use for identifying proximal triggers of crises and distress in marginalized populations.

Only three studies examined the predictive utility of EMA30,31,34. These studies performed advanced analytical approaches, including lagged analyses, machine learning, and multilevel structural equation models. However, most other studies relied on same-day or aggregated associations29,32,36,38, which limited the capacity of EMA to capture temporal sequencing and intra-individual variability, both of which are central to its methodological strengths in capturing how mental health states fluctuate within individuals over time and in identifying short-term predictors of risk. The limited use of dynamic modeling is consistent with broader critiques in intensive longitudinal research and digital mental health, where predictive models frequently lack external validation and transparent reporting of performance metrics42,52.

Importantly, no studies in this review tested interventions triggered by EMA data. Two studies integrated EMA into the early-stage JITAI framework37,39, delivering mindfulness and self-regulation prompts in response to elevated risks. These efforts mirror recent advances in personalized real-time interventions that leverage mobile sensing, EMA, and machine learning to deliver mental health support adaptively45,53,54. Although promising, a critical gap remains in translating EMA data into adaptive community-informed interventions tailored to the unique needs of SGMs.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to synthesize EMA studies that focus on mental health outcomes among SGM. While EMA has been widely applied in general mental health research, prior reviews have not focused on its feasibility, acceptability, or predictive utility, specifically for the SGM population who face elevated mental health risks due to minority stress, social exclusion, and systemic stigma. The review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines and included studies from diverse settings. Notably, all included studies were published between 2020 and 2025, reflecting a rapidly developing area of inquiry in response to recent advances in digital health and rising awareness of SGM mental health disparities. The use of the MMAT enabled the consistent evaluation of methodological quality across various study designs. Furthermore, the emphasis on digital EMA approaches in this review reflects the evolving role of mobile technologies in capturing mental health experiences within real-world contexts and the broader move toward ecologically valid and temporally sensitive methodologies.

However, this study has several limitations. First, the studies included in the review were predominantly conducted in high-income settings and primarily sampled younger digitally literate participants with moderate to high levels of education. Few studies included older adults, economically disadvantaged individuals, or gender-diverse subgroups such as non-binary or transgender participants. Second, the heterogeneity of study designs, EMA protocols, and outcome measures limited the ability to perform meta-analyses and directly compare results across studies. The reliance on small sample sizes and predominantly observational longitudinal study designs in the included studies limits the generalizability of the findings and restricts their ability to infer causality. Finally, while feasibility and acceptability were commonly assessed, only a subset of studies reported participant-level feedback or systematically examined emotional burden, which may affect long-term engagement and the ethical deployment of EMA in vulnerable populations.

This review highlights EMA as a promising methodology for capturing dynamic mental health processes among SGMs, offering a foundation for developing adaptive real-time interventions. When integrated into clinical and community-based settings that deliver mental health and psychosocial support, the EMA can facilitate the early identification of stress, depression, and STBs, and inform personalized care, particularly through JITAIs. Studies primarily relied on purpose-built EMA apps or adapted survey platforms, but few examined how such tools could integrate with existing service delivery, representing a key opportunity for digital mental health innovation. At the policy level, investing in affirming digital infrastructure that addresses the needs of structurally marginalized SGM communities is important. Efforts should focus on ensuring digital accessibility, protecting user autonomy, and incorporating privacy and safety features, particularly in contexts where SGM faces heightened legal or social risks.

Future research should prioritize longer EMA protocols and expand the representation to include diverse SGM subgroups. Methodological consistency in sampling strategies, outcome measurements, and external validation of predictive modeling is required to strengthen comparability and translational potential. Equally important is the co-design of culturally grounded JITAIs that leverage EMA data to deliver timely, ethical, and contextually relevant support integrated into clinical settings.

In conclusion, research applying EMA to mental health among SGM remains in its early stages, with all included studies published within the past 5 years. While findings underscore EMA’s potential for capturing dynamic predictors of psychological distress, the current studies are methodologically heterogeneous and largely descriptive, with limited predictive modeling, minimal inclusion of older adults and gender-diverse subgroups, and limited progress toward the development of EMA-informed interventions. As the field advances, shifting from passive monitoring to real-time monitoring and providing adaptive interventions such as JITAIs will be critical. EMA holds considerable promise, but its success will depend on addressing these gaps through rigorous research and thoughtful implementation that reflects the realities of the communities it aims to serve.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines55 (Supplementary Table 2) and was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024620214).

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they (1) used digital EMA methods, such as experience sampling or daily diary techniques delivered via mobile phones, personal digital assistants (PDAs), smartwatches, or online survey tools; (2) focused on SGMs, defined as individuals identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, non-binary, or other non-cisgender and non-heterosexual identities; (3) assessed outcomes related to psychological distress, including stress, depression, anxiety, and STBs; and (4) included participants regardless of baseline mental health status (i.e., with or without existing symptoms or diagnoses). Only peer-reviewed quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods studies were included.

Studies were excluded if they included SGM participants along with other populations but did not report findings for SGM separately. Additional exclusion criteria included the use of non-digital methods (e.g., paper-and-pen diaries), a sole focus on physical health without connection to mental health, or insufficient methodological details regarding EMA implementation or mental health measurement. Studies that exclusively recruited participants with severe mental illnesses (e.g., psychotic disorders) were also excluded.

We included studies that used digital EMA methods involving repeated assessments in real-world settings, even if prompts asked about experiences over the past few hours (e.g., “since the last prompt” or “in the past 2 h”), as long as the recall window was brief, clearly defined, and situated within the day-level temporal context typical of EMA protocols.

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted across five electronic databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Scopus, and Cochrane Library, from inception through April 30, 2025. The strategy incorporated both Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text keywords, organized around three concept groups: (1) EMA methods, including “ecological momentary assessment,” “experience sampling method,” “daily diary,” “ambulatory assessment,” “real-time monitoring,” and “electronic diary”; (2) mental health outcomes, including “psychological distress,” “depression,” “anxiety,” “stress,” “suicidal ideation,” “suicide plan,” “suicide attempt,” “self-harm,” “minority stress”; and (3) sexual and gender minority populations, including “sexual and gender minorities,” “LGBTQ,” “sexual orientation,” “gender identity,” “lesbian,” “gay,” “bisexual,” “transgender,” “queer,” “non-binary,” “GBMSM,” and “gender diverse”.

The full search strategy for each queried database is provided in Supplementary Table 3. All results were exported to EndNote for de-duplication and transferred to the online Covidence tool for screening. The reference lists of relevant retrieved papers were manually searched for additional studies.

Screening, data extraction, and coding

Two reviewers (KG and BB) independently screened the titles and abstracts using Covidence, followed by full-text reviews based on the predefined eligibility criteria (Supplementary Data 2). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consultation with a third reviewer (KP). The first author (KG) extracted data from the eligible studies using a structured coding template and cross-verified it with a second reviewer (KP). The extracted data included study characteristics (e.g., author, year, study design, and geographic location), sample details (e.g., demographics and SGM subgroups), EMA methodology (e.g., type of tool, frequency, and duration of prompts), and outcomes (e.g., mood, stress, depression, anxiety, STBs). The feasibility and acceptability measures, including retention rates, adherence rates, and participant feedback, were also recorded (Supplementary Data 1). The second author (KP) performed cross-verification of the extracted data. We contacted the corresponding authors in two cases where study eligibility was unclear due to the absence of disaggregated data56,57. Farmer et al.56 responded and clarified that disaggregated data were not available. Moscardini et al.57 responded that their IRB does not permit sharing the data.

Risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers (KG and KP) independently assessed the methodological quality of all included studies using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT, 2018 version), which is designed to evaluate qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies58. The MMAT consists of five core criteria for each study design, including the appropriateness of the study design, the adequacy of data collection and analysis, and the coherence between the data and interpretation. Each study was rated according to the number of criteria it met: studies meeting all five criteria were rated as high-quality, those meeting three to four criteria as moderate-quality, and those meeting one to two criteria as low-quality. Disagreements in quality ratings were resolved through discussion.

Data synthesis

A narrative synthesis was conducted to combine the findings of the included studies guided by the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews59,60. Qualitative and quantitative data were reviewed separately to extract and summarize key findings within each category. These findings were integrated into overarching themes by using a narrative synthesis approach. The synthesis was organized around the key domains identified across studies, including EMA protocols and methodologies, mental health outcomes assessed, feasibility, acceptability, and predictive utility for interventions. The main findings are presented within these themes and summarized in standardized tables to support systematic comparisons through tabulation, basic data transformation, and descriptive summaries.

Data availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its supplementary files.

References

King, M. et al. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry 8, 70–70 (2008).

Lucassen, M. F. G., Stasiak, K., Samra, R., Frampton, C. M. A. & Merry, S. N. Sexual minority youth and depressive symptoms or depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Aust. N.Z. J. Psychiatry 51, 774–787 (2017).

Paudel, K. et al. Suicidal ideation, plan, and attempt among men who have sex with men in Nepal: findings from a cross-sectional study. PLOS Glob. Public Health 3, e0002348 (2023).

Hoy-Ellis, C. P. Minority stress and mental health: a review of the literature. J. Homosex. 70, 806–830 (2023).

Geoffroy, M. & Chamberland, L. Mental health implications of workplace discrimination against sexual and gender minorities: a literature review. Santé Ment. au Qué. 40, 145–172 (2015).

Lin, C.-Y., Griffiths, M. D., Pakpour, A. H., Tsai, C.-S. & Yen, C.-F. Relationships of familial sexual stigma and family support with internalized homonegativity among lesbian, gay and bisexual individuals: the mediating effect of self-identity disturbance and moderating effect of gender. BMC Public Health 22, 1–1465 (2022).

Sharma, K. “I thought they would at least love me”: the gay experiences of heteronormative regimentation in Indian families, a phenomenological ethnography. LGBTQ+ Fam. Interdiscip. J. 20, 122–139 (2024).

Clark, K. A., Salway, T., McConocha, E. M. & Pachankis, J. E. How do sexual and gender minority people acquire the capability for suicide? Voices from survivors of near-fatal suicide attempts. Ssm. Qual. Res. Health 2, 100044 (2022).

Gautam, K. et al. Preferences for mHealth intervention to address mental health challenges among men who have sex with men in Nepal: qualitative study. JMIR Hum. Factors 11, e56002 (2024).

Xie, Y. & Peng, M. Attitudes toward homosexuality in China: exploring the effects of religion, modernizing factors, and traditional culture. J. Homosex. 65, 1758–1787 (2018).

Seiler-Ramadas, R. et al. “I don’t even want to come out”: the suppressed voices of our future and opening the lid on sexual and gender minority youth workplace discrimination in Europe: a qualitative study. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 19, 1452–1472 (2022).

Cancela, D., Stutterheim, S. E., Uitdewilligen, S. & Hülsheger, U. R. The time-lagged impact of microaggressions at work on the emotional exhaustion of transgender and gender diverse employees. Int. J. Transgend. Health 115, 1–18 (2024).

Ropero-Padilla, C. et al. Exploring the microaggression experiences of LGBTQ+ community for a culturally safe care: a descriptive qualitative study. Nurse Educ. Today 115, 105423–105423 (2022).

Kimber, B., Oxlad, M. & Twyford, L. The impact of microaggressions on the mental health of trans and gender-diverse people: a scoping review. Int. J. Transgend. Health, 1–21 https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2024.2380903 (2024).

Santoniccolo, F. & Rollè, L. The role of minority stress in disordered eating: a systematic review of the literature. Eat. Weight Disord. 29, 41–11 (2024).

Shiffman, S., Stone, A. A. & Hufford, M. R. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 4, 1–32 (2008).

Moskowitz, D. S. & Young, S. N. Ecological momentary assessment: what it is and why it is a method of the future in clinical psychopharmacology. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 31, 13–20 (2006).

Abplanalp, S. J., Reavis, E. A., Le, T. P. & Green, M. F. Applying continuous-time models to ecological momentary assessments: a practical introduction to the method and demonstration with clinical data. NPP - Digit. Psychiatry Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44277-024-00004-x (2024).

Meyer, I. H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 129, 674–697 (2003).

Hatzenbuehler, M. L. Structural stigma and the health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 23, 127–132 (2014).

Khati, A. et al. Ethical issues in the use of smartphone apps for HIV prevention in Malaysia: focus group study with men who have sex with men. JMIR Form. Res. 6, e42939 (2022).

Rudolph, A. E., Young, A. M. & Havens, J. R. Privacy, confidentiality, and safety considerations for conducting geographic momentary assessment studies among persons who use drugs and men who have sex with men. J. Urban health 97, 306–316 (2020).

Rendina, H. J. & Mustanski, B. Privacy, trust, and data sharing in web-based and mobile research: participant perspectives in a large nationwide sample of men who have sex with men in the United States. J. Med. Internet Res. 20, e233 (2018).

Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Nolen-Hoeksema, S. & Dovidio, J. How does stigma “get under the skin”? The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychol. Sci. 20, 1282–1289 (2009).

English, D., Rendina, H. J. & Parsons, J. T. The effects of intersecting stigma: a longitudinal examination of minority stress, mental health, and substance use among black, Latino, and multiracial gay and bisexual men. Psychol. Violence 8, 669–679 (2018).

Clark, V. & Kim, S. J. Ecological momentary assessment and mHealth interventions among men who have sex with men: scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e27751–e27751 (2021).

Gromatsky, M. et al. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) of mental health outcomes in veterans and servicemembers: A scoping review. Psychiatry Res. 292, 113359 (2020).

Hall, M., Scherner, P. V., Kreidel, Y. & Rubel, J. A. A systematic review of momentary assessment designs for mood and anxiety symptoms. Front. Psychol. 12, 642044–642044 (2021).

Livingston, N. A. et al. Real-time associations between discrimination and anxious and depressed mood among sexual and gender minorities: the moderating effects of lifetime victimization and identity concealment. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 7, 132–141 (2020).

Mereish, E. H. et al. A daily diary study of minority stressors, suicidal ideation, nonsuicidal self-injury ideation, and affective mechanisms among sexual and gender minority youth. J. Psychopathol. Clin. Sci. 132, 372–384 (2023).

Lei, C., Qu, D., Liu, K. & Chen, R. Ecological momentary assessment and machine learning for predicting suicidal ideation among sexual and gender minority individuals. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2333164 (2023).

Bitran, A. M. et al. The effects of family support and smartphone-derived homestay on daily mood and depression among sexual and gender minority adolescents. J. Psychopathol. Clin. Sci. 133, 358–367 (2024).

Hoelscher, E. C., Victor, S. E., Trieu, T. H. & Edmiston, E. K. Gender minority resilience and suicidal ideation: a longitudinal and daily examination of transgender and nonbinary adults. Behav. Ther. 46, 32–38 (2023).

Clark, K. A. et al. Real-time exposure to negative news media and suicidal ideation intensity among LGBTQ young adults in a high-stigma US state. Eur. J. Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckae144.733 (2024)

Wray, T. B., Emery, N. N. & Guigayoma, J. P. Emotional reactions to high-risk sex among sexual minority men: exploring potential opportunities for just-in-time intervention. J. Sex. Res. 60, 718–727 (2023).

Heron, K. E. et al. Sexual minority stressors and disordered eating behaviors in daily life: a daily diary study of sexual minority cisgender female couples. Eat. Disord. 33, 25–43 (2025).

Sizemore, K. M. et al. A proof of concept pilot examining feasibility and acceptability of the positively healthy just-in-time adaptive, ecological momentary, intervention among a sample of sexual minority men living with HIV. J. happiness Stud. 23, 4091–4118 (2022).

Williams, A. J., Arcelus, J., Townsend, E. & Michail, M. Feasibility and acceptability of experience sampling among LGBTQ+ young people with self-harmful thoughts and behaviours. Front. Psychiatry 13, 916164–916164 (2022).

Trang, K. et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and design of a mobile ecological momentary assessment for high-risk men who have sex with men in Hanoi, Vietnam: qualitative study. JMIR Form. Res. 6, e30360–e30360 (2022).

Dunton, G. F. Ecological momentary assessment in physical activity research. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 45, 48–54 (2017).

Myin-Germeys, I. et al. Experience sampling methodology in mental health research: new insights and technical developments. World Psychiatry 17, 123–132 (2018).

Kivelä, L., van der Does, W. A. J., Riese, H. & Antypa, N. Don’t miss the moment: a systematic review of ecological momentary assessment in suicide research. Front. Digit. Health 4, 876595–876595 (2022).

Hubach, R. D. et al. “Out here the rainbow has mud on it”: perceived confidentiality risks of mobile-technology-based EMA to assess high risk behaviors among rural MSM. Arch. Sex. Behav. 50, 1641–1650 (2020).

Hsiang, E. et al. Bridging the digital divide among racial and ethnic minority men who have sex with men to reduce substance use and HIV risk: mixed methods feasibility study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 8, e15282 (2020).

Balaskas, A., Schueller, S. M., Cox, A. L. & Doherty, G. Ecological momentary interventions for mental health: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 16, e0248152–e0248152 (2021).

Torous, J. et al. The growing field of digital psychiatry: current evidence and the future of apps, social media, chatbots, and virtual reality. World Psychiatry 20, 318–335 (2021).

Cramer, A. O. J. et al. Major depression as a complex dynamic system. PLoS ONE 11, e0167490–e0167490 (2016).

Ebner-Priemer, U. W., Eid, M., Kleindienst, N., Stabenow, S. & Trull, T. J. Analytic strategies for understanding affective (in)stability and other dynamic processes in psychopathology. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 118, 195–202 (2009).

Trull, T. J. & Ebner-Priemer, U. Ambulatory assessment. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 9, 151–176 (2013).

Kleiman, E. M. et al. Examination of real-time fluctuations in suicidal ideation and its risk factors: results from two ecological momentary assessment studies. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 126, 726–738 (2017).

Dawood, S. et al. Comparing signal-contingent and event-contingent experience sampling ratings of affect in a sample of psychotherapy outpatients. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 42, 13–24 (2020).

Schick, A. et al. Novel digital methods for gathering intensive time series data in mental health research: scoping review of a rapidly evolving field. Psychol. Med. 53, 55–65 (2023).

Coppersmith, D. D. L. et al. Just-in-time adaptive interventions for suicide prevention: promise, challenges, and future directions. Psychiatry 85, 317–333 (2022).

Nahum-Shani, I. et al. Just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs) in mobile health: key components and design principles for ongoing health behavior support. Ann. Behav. Med. 52, 446–462 (2018).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J. & Altman, D. G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Phys. Ther. 89, 873–880 (2009).

Farmer, S., Mindry, D., Comulada, W. S. & Swendeman, D. Mobile phone ecological momentary assessment of daily stressors among people living with HIV: elucidating factors underlying health-related challenges in daily routines. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 28, 737–751 (2017).

Moscardini, E. H. et al. Frequency and predictors of virtual hope box use in individuals experiencing suicidal ideation: an ecological momentary assessment investigation. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 54, 61–69 (2024).

Hong, Q. N. et al. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 34, 285–291 (2018).

Campbell, M. et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ 368, l6890–l6890 (2020).

Higgins, J. P. T. et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, second edn (Wiley-Blackwell, 2019).

Acknowledgements

This study received no funding. The work was carried out as part of the first author’s PhD dissertation at the University of Connecticut.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.G. conceptualized the study, led the study design, and oversaw all stages of the review process. K.G. and B.B. conducted the title/abstract screening and full-text review, with K.P. serving as the third reviewer to resolve discrepancies. K.G. extracted and coded the data, which was cross-verified by K.P. K.G. and K.P. performed the risk of bias assessments. K.G. drafted the manuscript. R.S., P.K.V., C.L.P., J.A.W., A.K., and K.P. contributed to the interpretation of findings and provided critical revisions. R.S., R.X., and M.M.C. supervised the project and provided ongoing mentorship. All other authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gautam, K., Paudel, K., Bautista, B. et al. Systematic review of ecological momentary assessment for assessing mental health among sexual and gender minorities. npj Digit. Public Health 1, 3 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44482-025-00006-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44482-025-00006-2