Abstract

This paper describes the performance of a fabricated prototype Al0.2Ga0.8As 55Fe radioisotope microbattery photovoltaic cells over the temperature range −20 °C to 50 °C. Two 400 μm diameter p+-i-n+ (3 μm i-layer) Al0.2Ga0.8As mesa photodiodes were used as conversion devices in a novel X-ray microbattery prototype. The changes of the key microbattery parameters were analysed in response to temperature: the open circuit voltage, the maximum output power and the internal conversion efficiency decreased when the temperature was increased. At −20 °C, an open circuit voltage and a maximum output power of 0.2 V and 0.04 pW, respectively, were measured per photodiode. The best internal conversion efficiency achieved for the fabricated prototype was only 0.95% at −20 °C.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Radioactive sources coupled to semiconductors have received research attention for producing long life radioisotope microbatteries1. High-energy particles are emitted during nuclear decay of a radioisotope which is coupled to a semiconductor converter device. The semiconductor material absorbs the particles, creating electron-hole pairs and producing electrical energy over a long period of time, governed by the half-life of the chosen radioisotope. In biomedical applications, providing a power supply, that has no need of periodic recharge or replacement, is a priority for the life-quality of patients requiring implanted medical devices2. Microbatteries that can operate over an extended period of time are also essential in security and defense applications, for example, FPGA encryption keys with battery backed memory are used for secure exchange of information between personnel3. Radioisotope microbatteries are candidate devices to help meet the needs and opportunities within these research fields, as well as being potentially useful more generally in microelectromechanical system technologies (MEMS)1.

Nuclear (radioisotope) microbatteries provide important characteristics such as high energy density and stability; for these reasons, they can be better options than traditional power supplies (e.g. chemical batteries) in certain circumstances. Compared to narrow bandgap semiconductors, wide bandgap semiconductors are preferable as converter materials in nuclear batteries; firstly because the nuclear battery conversion efficiency increases linearly with bandgap4, and secondly because they can operate at elevated temperatures without cooling and are commonly radiation tolerant5,6. This makes their use possible in harsh environment conditions and reduces the likelihood of radiation damage from the integrated radioisotope or from external radiation sources. Recently, multiple types of nuclear microbattery have been reported7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Diamond detectors were investigated by Bormashov et al.7 for developing 63Ni-diamond beta-voltaic and 238Pu-diamond alpha-voltaic microbatteries with total battery efficiencies as high as 0.6% and 3.6%, respectively, at room temperature. GaN devices were reported by Cheng et al.8 for producing a high open circuit voltage (1.64 V) 63Ni-GaN beta-voltaic microbattery with a total battery efficiency of 0.98% at room temperature. Si and GaAs converter materials were used by Wang et al.10 for two different types of beta-voltaic microbattery: at 20 °C, a conversion efficiency of 0.05% was found for a 147Pm-Si microbattery, while 0.075% was obtained for a 63Ni-GaAs microbattery. SiC detectors were used by Chandrashekhar et al.11 and Eiting et al.12 at room temperature: while the first reported a 63Ni-SiC microbattery with at least 6% efficiency, the second demonstrated a 33P-SiC microbattery with 4.5% efficiency. Until recently, because of the high specific energy per Curie, mainly only alpha- and beta- emitting radioisotopes have been used in nuclear microbatteries (e.g. 0.3 μW·g·Ci−1·cm−2 for the beta emitter 147Pm1). However, recently, the electron capture X-ray emitter 55Fe (0.017 μW·g·Ci−1·cm−2 1) has received research attention for nuclear microbattery use13,14. Butera et al. reported temperature dependent characterisation of different types of 55Fe radioisotope X-ray microbatteries using GaAs and Al0.52In0.58P p+-i-n+ photodiodes as conversion devices13,14: at −20 °C (the lowest temperature investigated and the temperature at which the devices had the best performance) the 55Fe-GaAs microbattery and the 55Fe-Al0.52In0.58P microbattery had internal conversion efficiencies of 9% and 22%, respectively. Although 55Fe has a lower energy per Curie compared to other candidate radioisotope sources, its use is attractive because of the reduced damage risk for the converter device due to the low energy photons emitted. Furthermore, the wide availability, relatively low cost, and the need for only comparatively little shielding to protect users of the microbattery from the radioisotope also contribute to making 55Fe an attractive option.

In this paper, an Al0.2Ga0.8As 55Fe radioisotope microbattery is reported for the first time. The effect of temperature on the microbattery key parameters of the X-ray-photovoltaic microbattery are described over the temperature range −20 °C to 50 °C. The choice of Al0.2Ga0.8As (bandgap = 1.67 eV at room temperature15) as the converter material was expected to give advantages such as lower thermally generated leakage currents than would be experience by narrower bandgap devices of same geometry. Moreover, Al0.2Ga0.8As can be grown lattice matched with GaAs, which makes its growth relatively cheap, and GaAs/AlGaAs processing techniques are more routinely available for both academia and industry when compared with alternative wide bandgap materials. These characteristics combine to make AlGaAs a desirable material for building photovoltaic cells. Recently, different types of high efficiency solar cells, based on AlGaAs structures, have been demonstrated and their properties studied16,17,18. The spectroscopic detection of X-ray photons using AlGaAs was firstly reported by Lauter et al.19; subsequent work by Barnett et al.20,21,22,23,24 further developed the material in a higher aluminium fraction variant (Al0.8Ga0.2As) for X-ray photon counting spectroscopy applications.

Materials and Method

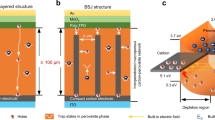

Radioactive source and energy conversion device

The prototype X-ray photovoltaic microbattery consisted of an 55Fe radioisotope X-ray source (activity 230 MBq) coupled to two 400 μm diameter unpassivated p+-i-n+ Al0.2Ga0.8As mesa conversion photodiodes (D1 and D2), located on the same die. The X-ray source was positioned 5 mm away from the Al0.2Ga0.8As devices’ top surfaces. The Al0.2Ga0.8As epilayer of the devices was grown and fabricated to the Authors’ specifications by the EPSRC National Centre for III-V Technologies, Sheffield, UK. The Al0.2Ga0.8As wafer was grown on a commercial GaAs n+ substrate using metalorganic vapour phase epitaxy (MOVPE). The thickness of the Al0.2Ga0.8As i-layer was 3 μm; further refinement and optimisation of the growth process may enable thick, high quality Al0.2Ga0.8As epilayers to be produced in future. After growth, the wafer was processed to form mesa structures using wet etching techniques, in particular 1:1:1 H3PO4:H2O2:H2O solution followed by 10 s in 1:8:80 H2SO4:H2O2:H2O solution. Table 1 summarises the device layers, their relative thicknesses and materials. The p+-side Ohmic contact, consisting of 20 nm of Ti and 200 nm of Au, covered 33% of the surface of each photodiode.

The X-ray quantum efficiency (QE) of the Al0.2Ga0.8As 55Fe radioisotope X-ray photovoltaic microbattery was calculated using the Beer-Lambert law and assuming a collection efficiency of 100% in the i-layer. A top metal contact coverage (33%) of each Al0.2Ga0.8As device surface was also taken into account. QE values of 23% (QEKα) and 18% (QEKβ) were calculated for 5.9 keV and 6.49 keV photons, respectively. The Al0.2Ga0.8As X-ray linear attenuation coefficients at 5.9 keV and 6.49 keV were estimated to be 0.0788 μm−1 and 0.0604 μm−1 25,26. At the same energies, the GaAs, Ti and Au attenuation coefficients used were from refs 25, 27.

Experiment and measurements

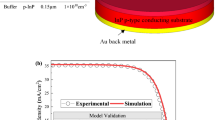

The Al0.2Ga0.8As 55Fe radioisotope X-ray-photovoltaic microbattery was placed inside a TAS Micro MT climatic cabinet with a dry nitrogen atmosphere (relative humidity <5%). Illuminated current as a function of forward bias characteristics of the Al0.2Ga0.8As 55Fe radioisotope X-ray-photovoltaic microbattery were investigated over the temperature range −20 °C to 50 °C. Forward bias measurements from 0 V to 0.5 V were made in 0.005 V increments using a Keithley 6487 picoammeter/voltage source. The uncertainty associated with a single current measurement reading was 0.3% of their values plus 400 fA, while the uncertainty associated with the applied biases was 0.1% of their values plus 1 mV28. It has to be noted that the uncertainty in current readings decreased for a set of measurements taken at the same Keithley working conditions (e.g. no variations in electrical connections, temperature); in this situation fittings on the experimental data give more appropriate current uncertainty values. Exponential fittings on the measured Al0.2Ga0.8As currents as a function of forward bias characteristics have been performed, current uncertainty <0.05 pA was estimated. Figure 1a shows the measured illuminated characteristics. Comparable results were obtained for both devices but for clarity only the results from one device, D1, are shown in the Fig. 1a. As shown in Fig. 1a, the softness in the knee of the measured current as a function of applied forward bias decreased when the temperature increased. Figure 1b shows dark and illuminated current characteristics as a function of forward bias for D2 at 20 °C.

(a) Current as a function of applied forward bias for D1. The temperatures studied were 50 °C (filled circles), 40 °C (empty circles), 30 °C (filled squares), 20 °C (empty squares), 10 °C (filled triangles), 0 °C (empty triangles), −10 °C (filled rhombuses) and −20 °C (empty rhombuses). (b) Dark (filled circles) and illuminated (empty circles) current characteristics as a function of forward bias for D2 at 20 °C.

The short circuit current (ISC) is defined as the current through the device when the voltage across it is zero. At every temperature, the experimental short circuit current values were obtained as the interception point of the curves in Fig. 1a on the vertical axis. In Fig. 2 the ISC values measured for D1 are reported as a function of temperature; comparable results were found for D2.

For a simple p-n diode, the short circuit current is proportional to the rate of optical (X-ray) carrier generation and the carrier diffusion length29. When the temperature is increased, it is expected that the optically (X-ray) generated carrier rate should increase because of the lower electron-hole pair creation energy at higher temperatures, whilst the carrier diffusion lengths should decrease because of the increased scattering with phonons. Although measurements of the electron-hole pair creation energy are yet to be reported for Al0.2Ga0.8As, it was reasonable to assume a decrease of electron-hole pair creation energy at high temperature (Barnett et al. reported a reduction in the average energy consumed in the generation of an electron-hole pair at high temperatures for Al0.8Ga0.2As illuminated with X-rays30). In Fig. 2, an almost flat trend was observed for the short circuit current with temperature; this was possibly due to the increased optical (X-ray) carrier generation being compensated by the decrease in the carrier diffusion lengths when the temperature was increased. The values of short circuit current observed for the Al0.2Ga0.8As 55Fe radioisotope microbattery were much lower than that previously reported for GaAs (~7 pA at −20 °C)13 and Al0.52In0.48P (~1.15 pA at −20 °C)14 55Fe radioisotope microbatteries. This smaller short circuit current in the presently reported Al0.2Ga0.8As microbattery was mainly attributed to the poorer crystalline quality of the Al0.2Ga0.8As structure with respect to the GaAs and Al0.52In0.48P detectors. In comparison with the GaAs microbattery, the Al0.2Ga0.8As converter layer also had a thinner i-layer (3 μm instead of 10 μm). Further analysis need to be conducted such to confirm the crystalline quality problem in the fabricated Al0.2Ga0.8As device.

The open circuit voltage (VOC) is defined as the voltage across the device when the current is zero. At each temperature, the open circuit voltage was obtained as the interception point of the curves in Fig. 1a on the horizontal axis. In Fig. 3, the VOC measured for D1 are reported as a function of temperature; similar results were found for D2.

For a simple p-n diode, the open circuit voltage is given by Equation 1,

where ISC is the short circuit current, I0is the saturation current, T is the temperature, k the Boltzmann’s constant, q the electronic charge and n the ideality factor11. Since I0 increases exponentially with temperature due to the thermal excitation of carriers in the conduction band; VOC is expected to decrease linearly when the temperature increases11. As expected and shown in Fig. 3, the open circuit voltage (VOC) decreased with temperature in the studied Al0.2Ga0.8As devices. The observed values of open circuit voltage of the presently reported microbattery were lower than those of the previously reported GaAs13 and Al0.52In0.48P14 55Fe radioisotope microbatteries. At −20 °C, for example, the Al0.2Ga0.8As 55Fe radioisotope microbattery had a VOC of 0.2 V; whilst the GaAs and Al0.52In0.48P microbatteries had VOC of 0.3 V and 1 V, respectively. This result can be explained by the lower ISC and possibly higher I0 in the Al0.2Ga0.8As structures. Material issues, such as the presence of traps in the structure, could be the one cause of the poor Al0.2Ga0.8As microbattery performance: trapped carriers from previous events can enhance the devices dark current resulting in higher I0 observed. The increased dark current also affected the number of photo-generated carriers detected by the devices: the photo-generated carriers can recombine with the charges trapped in the device resulting in lower ISC31.

At every investigated temperature, the output power (P) from each Al0.2Ga0.8As photodiode was computed as P = IV. When the bias was increased, the output power increased to a maximum (Pm) and then decreased. Figure 4 shows the output power from D1, similar results were obtained for D2. Figure 5 shows the magnitude of the maximum output power achieved for D1 at different temperatures. Similar results were found for D2.

Output power as a function of applied forward bias for D1 at different temperatures.

The temperatures studied were 50 °C (filled circles), 40 °C (empty circles), 30 °C (filled squares), 20 °C (empty squares), 10 °C (filled triangles), 0 °C (empty triangles), −10 °C (filled rhombuses) and −20 °C (empty rhombuses).

As the temperature was increased, the magnitude of the maximum output power decreased. This behaviour was expected considering that the dependence of the maximum output power (Pm) on the open circuit voltage32. In a photovoltaic cell, the maximum output power is given by Equation 2:

where VOC is the open circuit voltage, ISC is the short circuit current, and FF is a parameter called the fill factor. The fill factor is the measure of the squareness of the current as a function of voltage characteristic presented in Fig. 1a.

A maximum output power of 0.04 pW, corresponding to 0.017 μW/Ci (ratio between the maximum output power, 0.04 pW, and the number of photon expected on the detector, 0.08 × 106 s−1 = 2.26 × 10−6 Ci), was observed from the Al0.2Ga0.8As cell D1 at −20 °C.

The number of photons per second emitted in any direction by the source was estimated knowing the activity of the source and the emission probabilities of Mn Kα and Mn Kβ X-rays from 55Fe (0.245 and 0.0338, respectively25); it was found that 6.4 × 107 photons per second are emitted by the 55Fe radioactive source. Of these 6.4 × 107 photons per second, only half are emitted in the direction of the devices (we assumed that half of the photons were lost because they were emitted up). The number of photons per second on the devices (0.08 × 106 s−1) was estimated knowing the number of photons per second emitted by the source towards the devices (3.2 × 107 s−1), the thickness of the radioisotope X-ray source’s Be window (0.25 mm) and the geometry of the source and detectors. The ratio between the area of the devices (0.13 mm2) and the area of the radioactive 55Fe source (28.27 mm2) was calculated to be 0.0046. The number of photons on the detector was estimated by multiplying 0.0046 for the number of photons per seconds transmitted trough the X-ray source’s Be window (1.8 × 107 s−1).

The observed maximum output power value is much lower than the maximum output powers previously observed using GaAs cell (~1 pW)13 and Al0.52In0.48P cell (~0.62 pW)14 55Fe radioisotope microbatteries, at the same temperature. This was due to the smaller open circuit voltage and short circuit current values measured in the Al0.2Ga0.8As 55Fe radioisotope microbattery. The Al0.2Ga0.8As 55Fe radioisotope microbattery was of a two cell design (i.e. two photodiodes) such that the output power of the cells could be combined, giving a total microbattery output power of 0.07 pW at −20 °C. This was still less than the single cell GaAs and single cell Al0.52In0.48P 55Fe microbatteries previously reported.

The internal conversion efficiencies (η) of the Al0.2Ga0.8As photodiodes were investigated in the temperature range studied. Dividing the measured single cell maximum output power (Pm) by the maximum power (Pth) obtainable from the X-ray photons usefully absorbed by the device, the internal conversion efficiency of each Al0.2Ga0.8As device was calculated (equation 3).

Pth was calculated using equation 4

where A is the activity of the 55Fe radioactive source (230 MBq), AFe area of the 55Fe radioactive source (28.27 mm2), AAlGaAs area of the Al0.2Ga0.8As detector (0.13 mm2), EmKαand EmKβ the emission probabilities of Mn Kα and Mn Kβ X-rays from 55Fe (0.245 and 0.0338, respectively33), TKαand TKβ the transmission probabilities of Mn Kα and Mn Kβ X-rays through the 0.25 mm Be window (0.576 and 0.667, respectively25,27), QEKα and QEKβ the quantum efficiency values calculated in section “Material and Method A”, ωAlGaAs the Al0.2Ga0.8As electron-hole pair creation energy (4.4 eV, 2.5 times the bandgap). In equation 4 the activity of the 55Fe radioactive source was halved because we assumed that half of the X-ray photons were lost since they were emitted up. Pth was found to be 4 pW.

In Fig. 6, the internal conversion efficiency as a function of temperature for D1 is shown. Decreasing the temperature, the efficiency increased, in accordance with the maximum output power results presented in Fig. 5. At −20 °C, internal conversion efficiencies as high as 0.95% and 0.85% were observed for D1 and D2, respectively.

Although the bandgap of Al0.2Ga0.8As (1.67 eV at room temperature15) was greater than that of GaAs (1.42 eV at room temperature34), the internal conversion efficiency in the Al0.2Ga0.8As 55Fe radioisotope microbattery was lower than that observed in the GaAs 55Fe radioisotope microbattery13 at the same temperature. Material quality issues such as the presence of traps in the fabricated structure could explain the poorer performance observed. The presence of traps in AlGaAs devices have been previously reported by other researchers35,36,37,38. Traps can cause polarisation effects that may contribute to the device function39: the charge generated by the X-ray radiation can be trapped, building up space charges in the detector, which collapses the electric field and results in device degradation. The resulting change in the electric field has consequences for the electron transport within the semiconductor: the electron transit time in the detector depletion region increases, whilst the lifetime decreases due to recombination process. This causes a lower charge collection efficiency that reduced the photocurrent observed. Further analysis needs to be conducted such to confirm the crystalline quality problem of the fabricated Al0.2Ga0.8As device.

In the next generation of Al0.2Ga0.8As 55Fe radioisotope microbatteries, the maximum output power and consequently the internal conversion efficiency of the microbattery prototype (in accordance with what is expected by its wide bandgap) will have to be increased if Al0.2Ga0.8As is to become a realistic prospect for nuclear microbattery applications. The quality of the material must be improved to maximise the performance of the converter device. The system design must also be improved to increase the number of photons impinging upon the Al0.2Ga0.8As devices. The fraction of photons emitted by the 55Fe radioisotope X-ray source that impinged upon the devices was estimated knowing the activity of the source, the emission probabilities of the 55Fe Mn Kα and Mn Kβ X-rays (0.245 and 0.0338, respectively33), the thickness of the radioisotope X-ray source’s Be window (0.25 mm), and the geometry of the source and detectors. It was computed that only 0.26% of the photons emitted by the 55Fe radioisotope X-ray source were incident on the conversion devices.

Conclusion

In this paper, a prototype Al0.2Ga0.8As 55Fe radioisotope microbattery has been reported for the first time: a 230 MBq 55Fe radioisotope X-ray source was coupled to p+-i-n+ Al0.2Ga0.8As mesa photodiodes to achieve the direct conversion of nuclear energy into electrical energy. The performances of the fabricated prototype are described; in particular, the changes in key microbattery parameters are reported as a function of temperature. As the temperature was increased, the open circuit voltage, maximum power and internal conversion efficiency decreased. An open circuit voltage of 0.2 V was observed in a single cell Al0.2Ga0.8As p+-i-n+ mesa structure at −20 °C. An internal conversion efficiency of 0.95% was observed at −20 °C, taking into account attenuation from contacts and dead layer. Combining the output powers extracted from both the Al0.2Ga0.8As photodiodes, a total microbattery maximum output power of 0.07 pW was measured at −20 °C. Further studies need to be conducted such to assess the suitability of the Al0.2Ga0.8As material performance as X-ray energy conversion material, this will allow to conclude which of the above microbattery parameters are limited by the material itself and which depend on fabrication procedure and structure design.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Butera, S. et al. AlGaAs 55Fe X-ray radioisotope microbattery. Sci. Rep. 6, 38409; doi: 10.1038/srep38409 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Bower, K. E., Barbanel, Y. A., Shreter, Y. G. & Bohnert, G. W. Polymers, phosporors, and voltaics for radioisotope microbatteries (CRC Press LLC, Boca Raton, 2002).

Joung, Y. H. Development of implantable medical devices: from an engineering perspective. Int. Neurourol. J. 17, 98–106 (2013).

Trimberger, S. M. & Moore, J. J. FPGA security: Motivations, features, and applications. Proceedings of the IEEE 102, 1248–1265 (2014).

Chandrashekhar, M., Thomas, C. I., Li, H., Spencer, M. G. & Lal, A. Demonstration of a 4H SiC betavoltaic cell. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 033506 (2006).

Grant, J. et al. Wide bandgap semiconductor detectors for harsh radiation environments. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 546, 213–217 (2005).

Monroy, E., Omnès, F. & Calle, F. Wide-bandgap semiconductor ultraviolet photodetectors. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 18, R33 (2003).

Bormashov, V. et al. Development of nuclear microbattery prototype based on Schottky barrier diamond diodes. Phys. Status Solidi A 212, 2539–2547 (2015).

Cheng, Z., Chen, X., San, H., Feng, Z. & Liu, B. A high open-circuit voltage gallium nitride betavoltaic microbattery. J. Micromech. Microeng. 22, 074011 (2012).

Li, X.-Y., Ren, Y., Chen, X.-J., Qiao, D.-Y. & Yuan, W.-Z. 63Ni schottky barrier nuclear battery of 4H-SiC. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 287, 173–176 (2011).

Wang, H., Tang, X.-B., Liu, Y.-P., Xu, Z.-H., Liu, M. & Chen, D. Temperature effect on betavoltaic microbatteries based on Si and GaAs under 63Ni and 147Pm irradiation. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B 359, 36–43 (2015).

Chandrashekhar, M., Duggirala, R., Spencer, M. G. & Lal, A. 4H SiC betavoltaic powered temperature transducer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 053511 (2007).

Eiting, C. J., Krishnamoorthy, V., Rodgers, S. & George, T. Demonstration of a radiation resistant, high efficiency SiC betavoltaic. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 064101 (2006).

Butera, S., Lioliou, G. & Barnett, A. M. Gallium arsenide 55Fe X-ray-photovoltaic battery. J. Appl. Phys. 119, 064504 (2016).

Butera, S., Lioliou, G., Krysa, A. B. & Barnett, A. M. Al0.52In0.48P 55Fe X-ray-photovoltaic battery. J. Phys. D 49, 355601 (2016).

Berger, L. Semiconductor Materials (CRC Press LLC, Boca Raton, 1996).

Teran, A. S. et al. AlGaAs photovoltaics for indoor energy harvesting in mm-scale wireless sensor nodes. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 62, 2170–2175 (2015).

Abderrahmane, H., Dennai, B., Khachab, H. & Helmaoui, A. J. Effect of Temperature on the AlGaAs/GaAs Tandem Solar Cell for Concentrator Photovoltaic Performances. Nano- Electron. Phys. 8, 01015 (2016).

Aperathitis, E. et al. Effect of temperature on GaAs/AlGaAs multiple quantum well solar cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 51, 85–89 (1998).

Lauter, J., Protić, D., Förster, A. & Lüth, H. AlGaAs/GaAs SAM-avalanche photodiode: an X-ray detector for low energy photons. Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 356, 324–329 (1995).

Barnett, A. M., Lioliou, G. & Ng, J. S. Characterization of room temperature AlGaAs soft X-ray mesa photodiodes. Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 774, 29–33 (2015).

Barnett, A. M. et al. Temperature dependence of AlGaAs soft X-ray detectors. Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 621, 453–455 (2010).

Barnett, A. M. et al. Modelling results of avalanche multiplication in AlGaAs soft X-ray APDs. Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 626–627, 25–30 (2011).

Barnett, A. M., Lees, J. E., Bassford, D. J. & Ng, J. S. A varied shaping time noise analysis of Al0.8Ga0.2As and GaAs soft X-ray photodiodes coupled to a low-noise charge sensitive preamplifier. Nucl. Instr. Meth. A 673, 10–15 (2012).

Barnett, A. M., Lees, J. E. & Bassford, D. J. First spectroscopic X-ray and beta results from a 400 μm diameter Al0.8Ga0.2As photodiode. J. Inst. 8, P10014 (2013).

Cromer, D. T. & Liberman, D. Relativistic calculation of anomalous scattering factors for X rays. J. Chem. Phys. 53, 1891–1898 (1970).

Jenkins, R., Gould, R. W. & Gedcke, D. Quantitative X-ray Spectrometry, Second Ed. (CRC Press, New York, 1995).

Hubbell, J. H. Photon mass attenuation and energy-absorption coefficients. Int. J. Appl. Radiat. Is. 33, 1269–1290 (1982).

Keithley Instruments Inc., Model 6487 Picoammeter/Voltage Source Reference Manual, 6487-901-01 Rev B Cleveland (2011).

Radziemska, E. The effect of temperature on the power drop in crystalline silicon solar cells. Renew. Energy 28, 1–12 (2003).

Barnett, A. M., Lees, J. E. & Bassford, D. J. Temperature dependence of the average electron-hole pair creation energy in Al0.8Ga0.2As. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 181119 (2013).

Sheng, S. et al. Deep-level defects, recombination mechanisms, and their correlation to the performance of low-energy proton-irradiated AlGaAs—GaAs solar cells. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 27, 857–864 (1980).

Sze, S. M. & Ng, K. K. Physics of semiconductor devices, Third Ed. (John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, 2007).

Helene, O. A. M. et al. Update of X ray and gamma ray decay data standards for detector calibration and other application, Vol. 1 (International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, 2007).

Bertuccio, G. & Maiocchi, D. Electron-hole pair generation energy in gallium arsenide by x and γ photons. J. Appl. Phys. 92, 1248–1255 (2002).

Yamanaka, K., Naritsuka, S., Kanamoto, K., Mihara, M. & Ishii, M. Electron traps in AlGaAs grown by molecular‐beam epitaxy. J. Appl. Phys. 61, 5062–5069 (1987).

Afalla, J. et al. Deep level traps and the temperature behavior of the photoluminescence in GaAs/AlGaAs multiple quantum wells grown on off-axis and on-axis substrates. J. Lumin. 143, 517–520 (2013).

Mari, R. H. et al. Electrical characterisation of deep level defects in Be-doped AlGaAs grown on (100) and (311) A GaAs substrates by MBE. Nanosc. Res. Lett. 6, 1–5 (2011).

Ren, M. et al. Al0.8Ga0.2As Avalanche Photodiodes for Single-Photon Detection. IEEE J. Quant. Electron. 51, 1–6 (2015).

Bale, D. S. & Szeles, C. Nature of polarization in wide-bandgap semiconductor detectors under high-flux irradiation: Application to semi-insulating Cd1−xZnxTe. Phys. Rev. B 77, 035205 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by STFC grant ST/M002772/1 (University of Sussex, A. M. B., PI). The authors are grateful to B. Harrison, R. J. Airey, S. Kumar at the EPSRC National Centre for III-V Technologies for material growth and device fabrication. G. Lioliou and M. D. C. Whitaker each acknowledge funding received from University of Sussex in the form of PhD scholarships.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.B. conceived the study; S.B. carried out the experiment; M.D.C.W. carried out preliminary characterisation of the Al0.2Ga0.8As photodiodes; G.L. created the automated scripts required for data collection and helped to set up the experiment; S.B. and A.M.B. discussed the data and wrote the manuscript; all authors contributed to the review, edit and approval of the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Butera, S., Whitaker, M., Lioliou, G. et al. AlGaAs 55Fe X-ray radioisotope microbattery. Sci Rep 6, 38409 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38409

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38409

This article is cited by

-

Temperature effects on an InGaP (GaInP) 55Fe X-ray photovoltaic cell

Scientific Reports (2017)