Abstract

Optic glioma, a slow-growing tumor, is associated with Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) mutations and increased midkine (MDK) production. A connection between asthma and optic glioma has previously been observed, but the mechanisms are unclear. To elucidate the role of asthma in the regulation of glioma formation, we investigated the role of T cells and the subsequent pathways in the regulation of microglia, a key player in the glioma tumor microenvironment (TME). While asthma is often linked to chronic inflammation, our mathematical analysis and experimental evidence suggest that inflammation can play a key role in suppressing the proliferation of optic glioma cells via immune reprogramming of T cells and the delicate control of signaling networks in microglia. Our mathematical model unveils the complex interactions between tumor and immune cells in optic glioma. Our results indicate that asthma-induced T cell reprogramming inhibits tumor growth by promoting the release of decorin and a subsequent suppression of CCR8 and the intercellular binding kinetics in microglia, followed by blocking of CCL5 production in TME via suppression of NFκB. We developed anti-cancer strategies by leveraging this asthma-induced immune regulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Optic glioma is a low-grade astrocytic tumor that arises primarily within the optic nerve, frequently in pediatric populations, and is strongly associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) mutations1,2,3,4. This tumor type, although histologically benign, poses significant clinical concerns due to potential progressive vision loss and hypothalamic dysfunction. A hallmark of NF1-associated optic glioma is the hyperactivation of RAS signaling, caused by loss-of-function mutations in the NF1 gene, which encodes neurofibromin, a negative regulator of RAS-GTP5,6,7,8. This molecular dysregulation contributes not only to tumor cell proliferation but also to broader alterations in the tumor microenvironment (TME), fostering biochemical conditions that promote immune cell recruitment, chronic inflammation, and tumor progression. Among the key factors influencing this microenvironment is midkine (MDK), a heparin-binding growth factor highly expressed in response to RAS activation9,10,11.

MDK is secreted from the optic nerve and has been shown to exert profound immunomodulatory effects9,10,11. It reshapes the phenotype of infiltrating T cells within the TME, leading to secretion of CCL4, a chemokine that plays a pivotal role in orchestrating immune–glial interactions9,12,13. Once released, CCL4 interacts with the microglial surface receptors, CCR514,15,16,17 and CCR818,19,20, forming ligand–receptor complexes that serve as an upstream activator of the nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) signaling pathway21,22,23. This particular pathway is widely recognized for its role in inflammation and cancer progression, and its activation culminates in the production of CCL5, a potent chemokine that fosters tumor growth by enhancing cell proliferation, migration, and immune evasion mechanisms21,22,24,25. As a result, the midkine–T cell–CCL4–microglia–NFκB–CCL5 axis forms a central pro-tumorigenic feedback loop within the optic glioma microenvironment.

Emerging studies suggest that environmental and inflammatory conditions, such as asthma21, can significantly alter immune cell function within the TME. Asthma is known to induce widespread immune remodeling, including the reprogramming of CD8+ T cells, which acquire non-cytotoxic, regulatory-like phenotypes21,22,26. In the optic glioma, asthma-induced, reprogrammed T cells (re-T cells) were shown to inhibit tumor growth by secreting decorin, a small leucine-rich proteoglycan with established anti-tumor properties22,27. Decorin is known to interact with various components of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and cell surface receptors, overcoming the ECM barrier in oncolytic virus (OV) therapy28 and interfering with CCR8-mediated signaling21,29 in the TME. Decorin can inhibit the formation of the CCL4–CCR8 complexes on microglia by competing with CCL4 in binding to CCR821,29, which leads to suppression of CCL5 induction by the downstream NFκB pathway, and eventually to attenuation of the tumor-promoting microenvironment30,31,32. This intriguing observation of indirect suppression of tumor growth through immune reprogramming rather than direct cytotoxic effects suggests a novel organ–organ control mechanism by which systemic inflammation and immune history, such as asthma, may influence glioma dynamics9,21,33,34, putting decorin on the list of promising avenues for therapeutic exploration in brain tumors. Despite these emerging insights, the full implications of the MDK–CCL4–CCR5/CCR8–NFκB–CCL5 axis, and its regulation by asthma-reprogrammed T cells, remain poorly understood.

In this work, we employed the framework of a differential equation model to account for the role of asthma-reprogrammed T cells and decorin in the regulation of the optic glioma microenvironment and tumor growth. Based on the schematic diagram in Fig. 1, the model consists of a system of ordinary and delay differential equations involving the following variables:

-

[R1](t) = Concentration of CCR5 at time t,

-

[\(\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}\)](t) = Concentration of the CCL4–CCR5 complex at time t,

-

[R2](t) = Concentration of CCR8 at time t,

-

[\(\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}\)](t) = Concentration of the CCL4–CCR8 complex at time t,

-

[L4](t) = Concentration of CCL4 at time t,

-

[D](t) = Concentration of decorin at time t,

-

[\(\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}\)](t) = Concentration of the decorin–CCR8 complex at time t,

-

[F](t) = Concentration of NFκB at time t,

-

[L5](t) = Concentration of CCL5 at time t,

-

M(t) = Density of microglia at time t,

-

T(t) = Density of T cells at time t,

-

Ta(t) = Density of re-programming T cells at time t,

-

C(t) = Density of optic glioma cells at time t.

NF1 mutations disrupt RAS signaling, leading to midkine production, while increased expression of decorin on asthma-induced T cells inhibits activation of NFκB by interfering with CCL4–CCR8 receptor binding on microglia. Down-regulated NFκB leads to a reduction in CCL5 production, a key driver of tumor growth.

This model is then used to: (i) investigate how asthma-induced T cell reprogramming influences the production of decorin and its subsequent inhibitory effects on CCR8, (ii) analyze how the balance between tumor-promoting (CCL5-mediated) and tumor-suppressive (decorin-mediated) pathways impacts glioma growth dynamics, and (iii) develop optimal therapeutic strategies targeting decorin production and CCR8 inhibition to suppress glioma progression effectively.

Our work is to incorporate decorin-mediated control of CCL4–CCR5/8-NFκB–CCL5 intracellular mechanism into a quantitative mathematical framework linking asthma-reprogrammed T-cell signaling to glioma growth dynamics, which leads to a comprehensive understanding of the whole immune assembly and processes with consistent, experimental validation. We show that the mathematical model can reproduce the empirical observations, and we make several predictions as to how various therapeutic interventions can prevent the onset of optic glioma.

Results

Core control system in the absence of asthma

Midkine is a neurotrophic growth factor35 that plays a crucial role in promoting optic glioma growth by inducing CCL4 expression in T cells, which in turn elevates CCL5 levels on microglia, a key driver of tumor progression. Figure 2 shows comprehensive changes of those key molecules ([L4], \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\), \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\), [L5]) as the midkine level is changed. Figure 2A, D show the dose–response curves of [CCL4] (Fig. 2A) and [CCL5] (Fig. 2D) levels for various midkine stimuli. Since midkine directly induces CCL4 production in T cells, a specific range of the midkine level is required for CCL4 expression. The quantitative analysis of the mathematical model shows that the predicted CCL4 expression aligns with observed experiments21 for various midkine input values (Fig. 2B; [MDK] = 0, 1.66, 3.33, 6.67 μM) and an increase in CCL4 levels lead to up-regulated receptor complexes ([CCL4 ⋅ CCR5] (blue) and [CCL4 ⋅ CCR8] (red)) in binding kinetics (Fig. 2C) and up-regulation of CCL5 (Fig. 2D) on microglia by activation of NFκB (Fig. 1). Figure 2E illustrates the positive correlation between CCL4 and CCL5 and up-regulation of both key input–output variables on microglia as midkine levels increase. This down- and up-regulation of CCL5 levels in response to low and high CCL4 stimuli was well quantified in experiments21 and predicted in the mathematical model (Fig. 2F).

A Steady state of [CCL4] in response to high and low midkine levels. B Changes in [CCL4] levels in response to various midkine concentrations ([MDK] = 0, 1.66, 3.33, 6.67 μM): model (blue) and experiments (red;21). C Levels of the CCL4-complex ([CCL4–CCR5] (blue) and [CCL4–CCR8](red)) in the system in response to various midkine concentrations ([MDK] = 0, 1.66, 3.33, 6.67 μM). Steady states of [CCL5] in response to various midkine levels (D) and corresponding SS correlation between CCL4 and CCL5 levels in the L4−L5 phase plane (E). F Comparison with experimental data: [CCL5] levels in the system in response to the low (left) and high (right) of CCL4 levels: simulation (blue) and experiments (red)21.

The delicate control of the intracellular system of [CCL4⋅CCR5] and [CCL4⋅CCR8] is necessary for the stable onset of tumor growth or maintenance of anti-tumorigenic mediation of microglia in a given immune–tumor interaction system. In Fig. 3, we investigate the effect of the binding rates of CCL4–CCR5 complex on the system’s dynamics, especially CCL5 expression, a key driver of optic glioma progression. Since CCL5 is primarily regulated by the activation of NFκB, we explore how modifications in binding and dissociation rates affect the formation of CCL4–CCR5 complexes and their downstream effectors, thus regulating the onset of tumor formation. Figure 3A shows the CCL5 level for various association rates (\({b}_{1}^{+}\)) and midkine levels. Since midkine plays a crucial role in inducing CCL4 production in T cells, its presence indirectly regulates CCL5 expression through the CCL4–CCR5–NFκB axis. While the higher \({b}_{1}^{+}\) and higher midkine levels lead to the up-regulation of CCL5, the lower \({b}_{1}^{+}\) and midkine levels inhibit CCL5 secretion from microglia. For a fixed \({b}_{1}^{+}\), an increase in the midkine leads to up-regulation of the CCL4–CCR5 complex (Fig. 2C), enhancing NFκB activation and CCL5 production (Fig. 3A, B). As \({b}_{1}^{+}\) is decreased from the base value (\({b}_{1}^{+}=12\to 1.2\)), [CCL4–CCR5] complex level (blue, Fig. 2C, E), NFκB expression (blue; Fig. 2F), and CCL5 production (blue, Fig. 2B) are significantly decreased even for high midkine levels, delaying the onset of tumor progression. On the other hand, an increase in \({b}_{1}^{+}\) from the base value (\({b}_{1}^{+}=12\to 120\)) leads to up-regulation of the [CCL4–CCR5] complex (blue, Fig. 3C, E) and elevation in the NFκB activation (blue, Fig. 3D, F) even at lower midkine levels. Consequently, this significantly enhances the expression of CCL5, promoting tumor progression. Because of the separate topological structure of the receptor binding networks among CCL4–CCR5 and CCL4–CCR8, the changes in \({b}_{1}^{+}\) do not affect the CCL4–CCR8 dynamics regardless of midkine concentrations (red, Fig. 3C, E). Figure 3G shows the CCL5 level for various dissociation rates (\({b}_{1}^{-}\)) and midkine concentrations. While the lower \({b}_{1}^{-}\) and higher midkine levels elevate CCL5 production, the higher \({b}_{1}^{-}\) and lower midkine levels suppress CCL5 secretion from microglia. For example, in the absence of midkine, an increase in \({b}_{1}^{-}\), the dissociation rate of the CCL4–CCR5 complexes, results in faster breakdown of the CCL4–CCR5 complex (blue, Fig. 3I) and deactivation of NFκB (blue, Fig. 3J), leading to lower CCL5 secretion (red, Fig. 3J). Even when the midkine level is high, the rapid dissociation of CCL4–CCR5 complexes (\({b}_{1}^{-}=0.18\to 1.8\)) prevents sustained NFκB activation (blue, Fig. 3K), thereby suppressing CCL5 production (Fig. 3H, L). In those cases, the CCL4–CCR8 complex level remains constant due to the network structure. These results suggest that a strategy of either increasing the dissociation rate or decreasing the association rate may serve as an anti-cancer potential to attenuate CCL5-mediated tumor progression by destabilizing CCL4–CCR5 interactions.

A CCL5 level for various midkine concentrations and association rates (\({b}_{1}^{+}\)). B CCL5 levels for various midkine concentrations when \({b}_{1}^{+}=1.2,12,120\) and \({b}_{1}^{-}=0.18\) fixed. Changes in the [CCL4–CCR5] and [CCL4–CCR8] complex levels (C) and NFκB/CCL5 (D) as \({b}_{1}^{+}\) is increased in the absence of midkine. E, F Same as in C, D in response to the high midkine concentration. G CCL5 levels for various midkine concentrations and dissociation rates (\({b}_{1}^{-}\)). H CCL5 levels for various midkine concentrations when \({b}_{1}^{-}=0.018,0.18,1.8\) and \({b}_{1}^{+}=12\) fixed. Changes in the [CCL4–CCR5] and [CCL4–CCR8] complex levels (I) and NFκB/CCL5 (J) as \({b}_{1}^{-}\) is increased in the absence of midkine. K, L Same as in I, J in response to the high midkine concentrations.

Figure 4A shows time courses of concentrations of CCR5 ([R1], solid) and CCL4–CCR5 complex (\([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\), dotted) in response to high ([L4] = 50 nM) and low ([L4] = 0.1 nM) CCL4 stimuli. The dynamic changes in the CCR8 ([R2], solid) and CCL4–CCR8 complex (\([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\), dotted) in the neighboring pathway for the same CCL4 input are shown in Fig. 4B. The initial condition was \([{R}_{1}](0)=50,[\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]=0,[\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]=0\). While a high (normal) CCL4 expression by microglia induces aggressive growth of an optic glioma by forming the CCL4–CCR5 and CCL4–CCR8 complexes and up-regulation of NFκB and CCL5 in microglia, either low levels of CCL4 or strong decorin expression from re-programmed T cells in TME from asthma do not support the onset of this form of glioma. Figure 4C shows the response to CCL4 in the core control system for various CCL4 levels (L4 = 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, 140, 160, 180, 200 nM). An increase in CCL4 levels promotes ligand binding activity in both CCL4–CCR5 and CCL4–CCR8 receptor systems. This transient activation of CCL4–CCR5/CCL4–CCR8 receptor binding and subsequent secretion of CCL5 (blue dashed in Fig. 4F) are in agreement with experimental data7 (Fig. 2F). In Fig. 4E, we investigate key binding activities in two receptor channels in response to a fluctuating CCL4 input expression level (Fig. 4D) over the range of 0–20 nM: \([{L}_{4}](t)=\,10\cos (\pi t/240)+10\). Given a fluctuating CCL4 environment, the CCL4–CCR5 (red solid curves in Fig. 4E) and CCL4–CCR8 (blue dashed curves in Fig. 4E) complexes fluctuate between high and low states. For instance, as the CCL4 input decreases, the high level of the initial CCL4-complexes binding activities is reduced, entering a zone of low tumor growth rates by suppressing NFκB (red curves in Fig. 4F), CCL5 secretion (blue dashed curves Fig. 4F), and essentially inducing the phenotypic transition from the on state (pink box in Fig. 4G) to the off state (blue box in Fig. 4G) of tumor growth. When the CCL4 level is increased again after t = 240 h, the binding activity is enhanced again (Fig. 4E), and the system exits the off state (blue → red box in Fig. 4G) by activating NFκB (red curves in Fig. 4F) and promoting CCL5 secretion (blue dashed in Fig. 4F) by microglia.

Time courses of concentrations of CCR5/CCL4–CCR5 complex (A) and CCR8/CCL4–CCR8 complex (B) in response to high ([L4] = 50 nM) and low ([L4] = 0.1 nM) CCL4 stimuli. C Binding response to CCL4 in the core control system. Time courses of CCL4-CCR5 (red solid, E) and CCL4-CCR8 (blue dashed, E) binding activity in response to a fluctuating CCL4 input (D): \([{L}_{4}](t)=10\cos (\pi t/240)+10\). F Time courses of the NFκB (red solid) and CCL5 (blue dashed) under L4(t) in (D). G Time courses of the cancer cell density under L4(t) in (D).

Given fluctuating CCL4 environment (Fig. 4D), different relative ratios of the dissociation to association in the CCL4–CCR5 pathway (\({K}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{CCR}}5}=0.15,\,15\,){\rm{e}}{\rm{s}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{b}}(\,,\,1500\,{\rm{nM}}\)) induce three types of formation of the CCL4–CCR5 complex (Fig. 5A): static high level (blue dashed), fluctuation between high and low states (red solid), or sustained low level (black dotted). For instance, with the ratio \({K}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{CCR}}5}\), as the CCL4 input decreases (blue solid in Fig. 4D), the high level of initial CCL4–CCR5 binding activities is reduced (red, Fig. 5A), entering a zone of low tumor growth rates (t ∈ [150, 350] in Fig. 5C) by suppressing NFκB (red, middle column in Fig. 5B), CCL5 secretion (blue, middle column in Fig. 5B), and essentially inducing the phenotypic transition from the on state to the off state of tumor growth. When the CCL4 level is increased again after t = 240 h, the binding activity is enhanced again (red, Fig. 5A) and the system exits the off state (red, Fig. 5C) by activating NFκB (red, Fig. 5B) and promoting CCL5 secretion (blue, Fig. 5B) by microglia. When \({K}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{CCR}}5}\) is small (=0.15 nM), the intracellular system induces a high level of CCL4–CCR5 binding (blue dashed, Fig. 5A), maintaining up-regulation of NFκB and CCL5 (left column in Fig. 5B), and thus leading to active tumor growth without entering the suppression zone (blue dashed, Fig. 5C) in spite of the fluctuating CCL4 levels. When \({K}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{CCR}}5}\) is large (=1500 nM), the binding activity of CCL4–CCR5 is significantly reduced (black dotted, Fig. 5A) in response to fluctuation between the high and low CCL4 levels, leading to down-regulation of NFκB and CCL5 (right column in Fig. 5B), leading to constant suppression of tumor growth (black dotted, Fig. 5C). In a similar fashion, different binding ratios in the CCL4–CCR8 pathway (\({K}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{CCR}}8}=0.1,\,10\,){\rm{e}}{\rm{s}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{b}}(\,,\,1000\,{\rm{nM}}\)) induce the same three modes of formation of the CCL4–CCR8 complex (Fig. 5D), the level of NFκB and CCL5 (Fig. 5E), and cancer cell population (Fig. 5F). Figure 5G illustrates phenotypic changes in response to the various dissociation constants (\({K}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{CCR}}5}\) and \({K}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{CCR}}8}\)). As dissociation constants are increased, the TME selects the frequent temporal immune transitions in preference to all time \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{a}\)-mode regardless of CCL4 fluctuation. Fig. 5H, I shows the time courses of concentrations of NFκB (Fig. 5H) and cancer cell population (Fig. 5I) in response to the same continuous temporal profile of CCL4 in Fig. 4D for various binding ratio sets \(({K}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{CCR}}5},{K}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{CCR}}8})=(0.15,0.1),\,(15,10),\,(1500,1000)\). For the base case \(({K}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{CCR}}5},{K}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{CCR}}8})=(15,10)\), a high–low–high fluctuation of CCL4 leads to a cycle of growth-suppression-growth in optic glioma (red, Fig. 5I) via the same regulation of CCL4–CCR5–CCR8–NFκB–CCL5 signaling as in Fig. 5A–F above. As the ratio is lower than the base values, the static high levels of NFκB (blue dashed, Fig. 5H) and CCL5 from sustained receptor complexed (\([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}],[\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\)) induce a continuous high growth rate (blue dashed, Fig. 5I), while as increase in these ratios induces a continuous low growth rate (black dotted, Fig. 5I) via the down-regulation NFκB and CCL5 (black dotted, Fig. 5H).

Time courses of CCL4–CCR5 binding activity (A), levels of NFκB and CCL5 at t = 240 h (comb) and 480 h (filled) (B), and time courses of cancer cell population (C) for various binding ratios \({K}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{CCR}}5}={b}_{1}^{-}/{b}_{1}^{+}=0.15,\,15\,){\rm{e}}{\rm{s}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{b}}(\,,\,1500\,{\rm{nM}}\) in response to a fluctuating CCL4 input Fig. 4D. Time courses of CCL4–CCR8 binding activity (D), levels of NFκB and CCL5 at t = 240 h (comb) and 480 h (filled) (E), and time courses of cancer cell population (F) for various binding ratios \({K}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{CCR}}8}={b}_{2}^{-}/{b}_{2}^{+}=0.1,\,10\,){\rm{e}}{\rm{s}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{b}}(\,,\,1000\,{\rm{nM}}\) in response to a fluctuating CCL4 input Fig. 4D. G The corresponding phenotypic transitions between \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{a}\) and \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{t}\) modes when dissociation constants (\({K}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{CCR}}5},\,{K}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{CCR}}8}\)) are varied. H, I time courses of NFκB levels and cancer cell population for various binding ratios in both CCL4–CCR5 and CCL4–CCR8 pathways: \(({K}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{CCR}}5},{K}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{CCR}}8})=(0.15,0.1),\,(15,10),\,(1500,1000)\).

Figure 6A shows the CCL5 level for various association rates (\({b}_{2}^{+}\)) and midkine levels in the intracellular system of microglia. While the higher \({b}_{2}^{+}\) and higher midkine expression lead to the up-regulation of CCL5, the lower \({b}_{2}^{+}\) and midkine input suppress CCL5 production from microglia. For a fixed \({b}_{2}^{+}\), an increase in the midkine level leads to up-regulation of the CCL4–CCR8 complex (red, Fig. 2C), promoting NFκB activation and CCL5 production (Fig. 6A, B). A decrease in \({b}_{2}^{+}\) from the base value (\({b}_{2}^{+}=12\to 1.2\)) induces suppression of both the [CCL4–CCR8] complex level (red, Fig. 6C, E), and CCL5 expression (red, Fig. 6B, D, and F), delaying the onset of tumor progression. On the other hand, an increase in \({b}_{2}^{+}\) from the base value (\({b}_{2}^{+}=12\to 120\)) leads to significant escalation of the [CCL4–CCR8] complex formation (blue, Fig. 6C, E) and elevation of NFκB levels (blue, Fig. 6D, F) even at lower midkine concentrations, enhancing the expression level of CCL5 (red, Fig. 6D, F). Thus, enhanced association strength of the [CCL4–CCR8] complex will promote tumor even in the absence of midkine. Figure 6G shows the CCL5 level for various dissociation rates (\({b}_{2}^{-}\)) and midkine levels. While the lower \({b}_{2}^{-}\) and higher midkine input promotes CCL5 secretion, the larger \({b}_{1}^{-}\) and lower midkine stimulus suppresses CCL5 expression on microglia. Figure 6H shows steady state values of CCL5 in response to various midkine levels for (\({b}_{2}^{-}=0.012,0.12,1.2\)) when \({b}_{2}^{+}\) is fixed (\({b}_{2}^{+}=12\)). The overall shape of the switching curve of CCL5 moves down (or up) as \({b}_{2}^{-}\) increases (or decreases), changing the probability of CCL5-mediated tumor growth. For example, an increase in \({b}_{2}^{-}\) (\({b}_{2}^{-}=0.12\to 1.2\)) leads to faster dissociation of the CCL4–CCR8 complex (red, Fig. 6I) and continuous down-regulation of NFκB (blue, Fig. 6J), leading to lower CCL5 secretion (red, Fig. 6J, L). Even in response to a high midkine level, the rapid dissociation of the CCL4–CCR8 complex weakens NFκB activation (blue, Fig. 6L) and CCL5 production (red, Fig. 6L). When \({b}_{2}^{-}\) is decreased (\({b}_{2}^{-}=0.12\to 1.2\)), the faster association of the CCL4–CCR8 complex (red, Fig. 6I, K) activates NFκB (blue, Fig. 6J, L) faster, providing the production efficiency of CCL5 (red, Fig. 6J, L) and, thus, sustained tumor growth. Because of the independent topological structure of the receptor binding networks among CCL4–CCR5 and CCL4–CCR8, the changes in \({b}_{2}^{+}\) or \({b}_{2}^{-}\) do not affect the CCL4–CCR5 dynamics in the presence of the low and high midkine levels (blue, Fig. 6C, E, I, and K).

A CCL5 levels at various midkine concentrations and association rates (\({b}_{2}^{+}\)). B CCL5 levels for various midkine levels when \({b}_{2}^{+}=1.2,12,120\) while \({b}_{2}^{-}=0.12\) is fixed. Changes in the [CCL4–CCR5] and [CCL4–CCR8] complex levels (C) and NFκB/CCL5 (D) as \({b}_{2}^{+}\) is increased in the absence of midkine. E, F Same as in C, D in response to the high midkine levels. G CCL5 levels for various midkine concentrations and dissociation rates (\({b}_{2}^{-}\)) and H when \({b}_{2}^{-}=0.012,0.12,1.2\) while \({b}_{2}^{+}=12\) fixed. I–L Changes in the [CCL4–CCR5]/[CCL4–CCR8] complex levels. I, K and NFκB/CCL5 (J, L) as \({b}_{2}^{-}\) is increased in the absence (I, J) and a high level (K, L) of midkine.

Asthma-induced core control system

In Fig. 7, we investigate the role of decorin in the regulation of pre-existing dynamics of CCL4–CCR8 in two-track receptor kinetics in Eqs. (18)–(22). Figure 7A shows time courses of levels of CCR8 and DCN–CCR8 complex in response to high (D = 200 nM) and low (D = 2 nM) decorin stimuli from asthma-induced reprogrammed T cells. The DCN–CCR8 complex is fully formed in the presence of high expression of decorin (red dashes, Fig. 7A) while low binding activities are observed in response to low decorin input (blue, Fig. 7A). On the other hand, this DCN–CCR8 formation upon high decorin stimulus interferes with accumulation of the CCR8/CCL4–CCR8 complex (red dashes, Fig. 7B) by taking up the CCR8 molecules (red dashes, Fig. 7B). Here, the initial condition was [R2](0) = 50, \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}](0)=0\), \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}](0)=0\), \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}](0)=0\). The phase planes in Fig. 7C, D show the corresponding flow of the solutions of the receptor binding with various initial conditions in response to low ([D] = 2 nM in Fig. 7C) and high ([D] = 200 nM in Fig. 7D), respectively. By defining thresholds for these intracellular variables, thD = 23 for the DCN–CCR8 complex and thL = 14 for the CCL4–CCR8 complex, we can define two different phenotypic modes, i.e., the pro-tumorigenic \(({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}})\) and anti-tumorigenic \(({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}})\) modes, as follows:

Figure 7C and D illustrates the pro-tumorigenic (high expression of the CCL4–CCR8 complex, low level of the DCN–CCR8 complex) and anti-tumorigenic (degradation of the CCL4–CCR8 complex, high accumulation of the DCN–CCR8 complex) in a \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]-[\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) plane. A low decorin level ([D] = 2) induces one stable SS (Fig. 7C) where suppression of the DCN–CCR8 complex formation and promotion of CCL4–CCR8-binding activities induce the tumorigenic status (\({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\)), by upregulation of NFκB and CCL5. In contrast, the heavy formation of the DCN–CCR8 complex and decreased activity of CCL4–CCR8 binding are induced under high decorin conditions ([D] = 200; Fig. 7D; one stable SS). In this tumor microenvironment, the system induces down-regulation of NFκB and CCL5, thus leading to the anti-tumorigenic phenotype (\({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\)). Figure 7E shows the dose–response curves of [CCL5] level for various decorin stimuli. Since decorin directly inhibits CCL4–CCR8 binding in microglia, an appropriate range of the decorin level is required to effectively suppress CCL5 expression. Figure 7F illustrates these characterized response patterns of an increase in the DCN–CCR8 complex formation and a decrease in the CCL4–CCR8 binding with respect to DCN levels. An increase in the decorin level ([D]) leads to the phenotypic transition from the tumorigenic mode (\({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\)) to the anti-tumorigenic status (\({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\)), while a decrease in [D] induces the reverse (\({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\to {{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\)) switching.

Time courses of levels of CCR8/DCN–CCR8 complex (A) and CCR8/CCL4–CCR8 complex (B) in response to high (D = 200 nM) and low (D = 2 nM) decorin stimuli. Initial condition: [R2](0) = 50, \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}](0)=0\), \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}](0)=0\), \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}](0)=0\). Dynamics of the core control (\([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\), \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\)) system (18)–(22) in the phase plane in response to low ([D] = 2 nM in (C)) and high ([D] = 200 nM in (D)) levels of the decorin, together with a schematic of anti-tumorigenic (\([\bar{D\cdot {R}_{2}}] > t{h}_{{\rm{D}}}\), \([\bar{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}] < t{h}_{{\rm{L}}}\)) and tumorigenic (\([\bar{D\cdot {R}_{2}}] < t{h}_{{\rm{D}}}\), \([\bar{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}] > t{h}_{{\rm{L}}}\)) regions in the DCN–CCR8/CCL4–CCR8 plane, respectively. Steady states marked with circles. E Steady states of [CCL5] in response to various decorin levels. F Binding response to decorin in the core control system. *thD = 23, thL = 14.

Decorin on the asthma-induced re-T cells plays an important role in reducing optic glioma growth21. We test how the intercellular receptor dynamics on the T cell-microglia respond to reduction (or acceleration) of decorin expression from asthma-free conditions (or asthma development) by introducing a fluctuating decorin function (Fig. 8A): \(D(t)=100\cos (\pi t/120)+100\). (Base parameter: \({K}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{DCN}}}=\frac{{b}_{3}^{-}}{{b}_{3}^{+}}\)=10 nM.) In response to the initial decreasing decorin level, the trajectory of the DCN–CCR8 complex solution follows the upper branches of the response curve (red circle curve, Fig. 7F) and jumps down to the lower values on the branch around [D] = 20. Thus, while \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\) remains constant, a decrease in the decorin level on re-T cells (red arrows, Fig. 8A) leads to the chemical dissociation of the DCN–CCR8 complex but accumulation of \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) (Fig. 8B) following the SS. CCL4–CCR8 complex branch (blue diamond curve, Fig. 7F), resulting in up-regulation of NFκB and CCL5 (Fig. 8C). This essentially increases the growth potential of the optic glioma (Fig. 8D), switching from the off state (\({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\)) to the on state (\({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\)) of glioma growth. When the decorin is delivered from asthma-induced re-T cells (blue arrows, Fig. 8A), the whole process of binding activities is reversed following the reverse direction on the solution branches in Fig. 7F, i.e., up-regulation of DCN–CCR8 complex and down-regulation of \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) (Fig. 8B), which leads to suppression of NFκB and CCL5 (Fig. 8C), and thus the critical transition of the on state (\({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\)) back to the off state (\({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\)) of glioma growth. Figure 8D shows time courses of tumor populations in response to either constant or varying decorin: (i) low decorin ([D] = 2, blue dashes), (ii) high decorin ([D] = 200, black dots), and (iii) fluctuating decorin levels (Fig. 8A). The low decorin level induces \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\)-phase (Fig. 7C), therefore, leading to midkine-mediated, faster glioma growth (blue dashed). When [D] is high, the receptor binding system induces the \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\) TME (Fig. 7D), resulting in asthma-controlled suppression of tumor growth (black dashed). On the other hand, fluctuating decorin induces alternating phenotypic switches between \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\) (blue zone) and \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\) (pink zone) phases at t = t1, t2, t3, t4 (Fig. 8C), which leads to either slow (blue region in Fig. 8D) or fast (pink region in Fig. 8D) tumor growth in \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\) and \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\)-zones, respectively, and eventually leads to an intermediate tumor size at final time (Fig. 8D). These computational results are in good agreement with recent experimental observation21, where decorin expression from asthma-induced re-T cells in the brain TME significantly inhibited fast optic glioma growth. Thus, the expression level of the DCN–CCR8 complex relative to the given CCL4–CCR8 complex level in the given TME can be an important index in predicting the onset of optic glioma in the clinics. Thus, we introduce the following index for the scaled \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\)-to-\([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) ratio at time t:

Thus, if RDe > 1, the system is decorin-induced anti-tumorigenic state for the optic glioma; otherwise, the system is tumorigenic, indicating a poor prognosis. Figure 8E shows the decorin index (RDe) and tumor volume at the final time corresponding to these three cases. The low (or high) index RDe (blue, Fig. 8E) is associated with fast (or slow) tumor growth (red, Fig. 8E) while the average value of RDe from fluctuating decorin stimuli indicates an intermediate level of the tumor formation potential. In Fig. 8F, we show the negative correlation between the decorin index RDe and tumor size. The RDe and tumor size were calculated from levels of \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) and \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) and scaled cancer cell populations at the final time in response to various decorin input values ([D] = 0–200). An increase in the decorin level from asthma-induced T cells results in an increase in RDe, which in turn suppresses NFκB, thus leading to diminished CCL5 production and suppression of the growth potential of the NF1-associated optic pathway gliomas21.

Time courses of binding activities (B), NFκB and CCL5 (C) in response to fluctuating decorin stimulus (A): \(D(t)=100\cos (\pi t/120)+100\). D Time courses of the tumor cell populations in response to a fixed ([D] = 2 (blue dashes); [D] = 200 (black dots)) and fluctuating decorin level. Fluctuating decorin expression induces transitions between \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\)- and \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\)-phenotypes, leading to transient glioma growth over time (t1, t2, t3, t4). The decorin-dominant \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\)-regions were shaded in pink in (C, D). E The scaled \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\)-to-\([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) ratio (called RDe) and tumor size for three decorin conditions in (D). F Negative correlations between the tumor volume and RDe. Base parameter: \({K}_{{\rm{D}}}^{{\rm{DCN}}}=\frac{{b}_{3}^{-}}{{b}_{3}^{+}}\)=10 nM. Other parameters are given in Table 1. Initial conditions: [R2](0) = 50, \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}](0)=0\), \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}](0)=0\), \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}](0)=0\).

In Fig. 9, we investigate the effect of the relative strength of the dissociation to the association in DCN–CCR8-binding activities, i.e.,\({K}_{D}^{{\rm{DCN}}}={b}_{3}^{-}/{b}_{3}^{+}\), on the core control system when embedded in the fluctuating decorin environment in Fig. 8A. In controls (\({K}_{D}^{{\rm{DCN}}}=\)10), the decorin-induced fluctuation in mutual antagonism between \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) (Fig. 9A) and \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) (Fig. 9B) leads to the continuous transition between \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\)- and \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\)-modes (middle, Fig. 9D) and alternation in the RDe index (red, Fig. 9C), thus generating a step-like tumor growth pattern (red solid, Fig. 9E). Here, \({R}_{{\rm{De}}}^{{\rm{ave}}}\) value in Fig. 9C was calculated as an average value of RDe at high (t = t1, t3, t5 in Fig. 9B) and low (t = t2, t4 in Fig. 9B) decorin time points. An increase in \({K}_{D}^{{\rm{DCN}}}\) (\({K}_{D}^{{\rm{DCN}}}=10\to 1000\)) induces up-regulation of \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) and down-regulation of \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) (black dots, Fig. 9A, B), maintaining the \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\) phase (top, Fig. 9D) regardless of decorin fluctuation. These lead to a sustained low decorin index (black dots, Fig. 9C) and fast tumor growth (dotted, Fig. 9E). On the other hand, a decrease in \({K}_{D}^{{\rm{DCN}}}\) (\({K}_{D}^{{\rm{DCN}}}=10\to 0.1\)) induces down-regulation of \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) and up-regulation of \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) (blue dashes, Fig. 9A, B), sustaining the \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\) phase (bottom, Fig. 9D) regardless of various decorin levels. These result in a very high RDe value (blue dashed, Fig. 9C) and significant tumor suppression (blue, Fig. 9E).

Time courses of the concentrations of the CCL4–CCR8 complex (A), DCN–CCR8 complex (B) for various ratios \({K}_{D}^{{\rm{DCN}}}\)=0.1, 10, 1000 nM in response to the fluctuating decorin in Fig. 8A. C The decorin index (RDe) at high and low decorin points (t = ti, i = 1, …, 5 in (B)) for three cases. D The corresponding phenotypic transitions between anti-tumorigenic and tumorigenic modes when \({K}_{D}^{{\rm{DCN}}}\) is varied. E Time courses of the scaled tumor sizes for three cases.

Sensitivity analysis

To further quantify the influence of each parameter on the local system’s behavior, we extended our analysis by conducting a sensitivity analysis on midkine levels and the binding kinetic parameters. The analysis allows us to identify which parameters are sensitive to key variables such as concentrations of [CCL4 ⋅ CCR5] complex, [CCL4 ⋅ CCR8] complex, [DCN ⋅ CCR8] complex, NFκB, and [CCL5], and the cancer cell population. The sensitivity results underscore the dynamic and nonlinear nature of the midkine–CCL4–microglia axis and point to potential therapeutic targets for modulating optic glioma progression through fine-tuned intervention in chemokine-receptor interactions. A range \([{P}_{i}^{min},{P}_{i}^{max}]\) (i = 1, …, 7) for each of the parameters (\([{\rm{MDK}}],{b}_{1}^{+},{b}_{1}^{-},{b}_{2}^{+},{b}_{2}^{-},{b}_{3}^{+},{b}_{3}^{-}\)) was chosen with the minimum (\({P}_{i}^{min}\)) and maximum (\({P}_{i}^{max}\)) values, and we divided each range into 10,000 intervals of uniform length. (Other parameters are fixed as in Table 1.) For a given parameter, a partial rank correlation coefficient (PRCC) value in the range of [− 1, 1] is calculated. A sign of the PRCC value indicates whether an increase (or decrease) in the parameter value will lead to an increase (+) (or decrease (−)) in the concentration of the main variable. The magnitude of the PRCC value indicates the correlation strength. Figure 10 shows the PRCC values of the concentrations/densities of biochemical variables (\([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\), \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\), \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\), NFκB (F), CCL5 (L5), and tumor density (C)) at a given time (t = 20, 50, 100). The levels of [CCL4 ⋅ CCR5], [CCL4 ⋅ CCR8], NFκB, and [CCL5], and the tumor size are positively correlated with midkine. However, the changes in midkine have the reverse effect on its counterpart, the [DCN ⋅ CCR8] complex. The association rate \({b}_{1}^{+}\) is positively correlated with variables such as [CCL4 ⋅ CCR5], NFκB, [CCL5], and cancer cell, as an increase in \({b}_{1}^{+}\) promotes the complex formation and downstream activation (Fig. 3). In contrast, \({b}_{1}^{-}\) shows a negative correlation with these tumor-promoting variables as faster dissociation diminishes complex stability and suppresses the downstream signal transduction (Fig. 3). On the other hand, the association and dissociation of the CCL4–CCR5 chemical reaction is confined to the downstream variables that are regulated via CCR-mediated signaling due to the model structure. Thus, the levels of the [CCL4 ⋅ CCR8] and [DCN ⋅ CCR8] complexes remain unchanged in response to changes in \({b}_{1}^{+},{b}_{1}^{-}\), showing no correlation. In a similar fashion, the association (or dissociation) rate of CCL4-CCR8 binding shows positive (or negative) correlations with variables in the pathway, such as the concentrations of the [CCL4 ⋅ CCR8] complex, NFκB, [CCL5], and tumor size, while showing a negative (or positive) correlation with the concentration of the [DCN ⋅ CCR8] complex. Due to the mutual antagonism between [CCL4 ⋅ CCR8] and [DCN ⋅ CCR8], the exact opposite sensitivities of \({b}_{3}^{+},{b}_{3}^{-}\) to those main variables in the signaling track are observed. Again, changes in these rates in the second route (\({b}_{2}^{+},{b}_{2}^{-}\), \({b}_{3}^{+},{b}_{3}^{-}\)) have little effect on [CCL4 ⋅ CCR5] in the pathway of the other track, as partially illustrated in Fig. 6.

General Latin hypercube sampling (LHS) scheme and partial rank correlation coefficient (PRCC) were performed on the model. The colors in each sub-box indicate PRCC values using the method of Marino et al.36 with a sample size of 10,000.

The detailed sensitivity analysis for the whole system is given in Supplementary information. The sensitivity analysis was performed using the method from Marino et al.36 and files available from the website of Denise Kirschner’s Lab: http://malthus.micro.med.umich.edu/lab/usadata/.

In order to examine the detailed sensitivity of chemical reaction parameters, Monte Carlo simulations are performed as illustrated in Figs. 11–13. In Fig. 11, the association and dissociation rate constants (\({b}_{1}^{+}\) and \({b}_{1}^{-}\)) corresponding to the reaction \([{L}_{4}]+[{R}_{1}]\rightleftharpoons [\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\) are randomly sampled. In Fig. 11A, a three-dimensional Monte Carlo sensitivity analysis is performed to examine the combined effect of the association (\({b}_{1}^{+}\)) and dissociation (\({b}_{1}^{-}\)) rate constants on the steady-state concentration of the CCL4–CCR5 complex (\([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\)). Each pair of (\({b}_{1}^{+},{b}_{1}^{-}\)) values is randomly sampled from logarithmic distributions spanning two orders of magnitude (1.2–120 μM−1 h−1 and 0.018–1.8 h−1, respectively), and 10,000 simulations are conducted. The resulting 3D scatter distribution revealed an inverse relationship between the binding and unbinding rates, where larger \({b}_{1}^{+}\) and smaller \({b}_{1}^{-}\) produced higher equilibrium levels of \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\). Figure 11B, C shows the sensitivity of the \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\) complex formation to variations in the association (\({b}_{1}^{+}\)) and dissociation (\({b}_{1}^{-}\)) rate constants, respectively. The resulting scatter plot demonstrates that the \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\) level increases with \({b}_{1}^{+}\), approaching saturation as receptor sites become occupied (Fig. 11B). In contrast, the scatter distribution indicates a clear negative correlation between \({b}_{1}^{-}\) and \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\), where an increase in \({b}_{1}^{-}\) leads to a pronounced reduction in the steady-state of \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\). Figure 11D shows how variations in \({b}_{1}^{+}\) and \({b}_{1}^{-}\) indirectly influence [L5] levels through the kinetic modulation of the upstream ligand–receptor binding and NFκB activation. Figure 11E presents the co-relationship between the kinetic parameters \({b}_{1}^{+},{b}_{1}^{-}\) and the cancer cell population (C). The results show that the enhanced ligand–receptor binding strength, achieved through higher \({b}_{1}^{+}\) or lower \({b}_{1}^{-}\), leads to an elevated C level over time. Figure 11F shows the histogram of the steady-state \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\) obtained from all 10,000 Monte Carlo runs. The unimodal distribution indicates a predominant equilibrium range, but with a measurable spread reflecting parameter uncertainty. This statistical representation highlights the intrinsic uncertainty of biochemical kinetics and provides a probabilistic measure of model robustness.

A Three-dimensional sensitivity surface showing the combined effect of \({b}_{1}^{+}\) and \({b}_{1}^{-}\) on \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\). Dependence of the steady-state complex \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\) on the association (B) and dissociation (C) rate constants. Dependence of the cytokine [L5] level (D) and cancer cell population (E) on \({b}_{1}^{+}\) and \({b}_{1}^{-}\). F Distribution of the final \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\) concentrations obtained from all Monte Carlo runs, illustrating variability due to kinetic uncertainty. n = 10,000 Monte Carlo samples; log-uniform parameter sampling.

Following the analysis of the L4−R1 binding kinetics, we next investigate the second ligand-receptor interaction, \([{L}_{4}]+[{R}_{2}]\rightleftharpoons [\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\), by varying the kinetics parameters \({b}_{2}^{+}\) and \({b}_{2}^{-}\) and using 10,000 Monte Carlo samples drawn from log-uniform distributions. Figure 12A–C summarize the sensitivity analysis of the \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) complex. Figure 12B shows that an increase in the association rate constant (\({b}_{2}^{+}\)) promotes complex formation, while Fig. 12C demonstrates that the dissociation rate \({b}_{2}^{-}\) is negatively correlated with the steady-state of \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\). Figure 12A presents the joint sensitivity surface for \({b}_{2}^{+},{b}_{2}^{-}\), revealing that strong binding affinity (high \({b}_{2}^{+}\), low \({b}_{2}^{-}\)) maximizes receptor occupancy, consistent with the trend observed for the \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\) (Fig. 11). Figure 12D–F illustrate how these variations propagate through the downstream network. In Fig. 12D, changes in \({b}_{2}^{+}\) and \({b}_{2}^{-}\) significantly alter the [L5] production, indicating that the L4−R2 interaction strongly regulates cytokine expression via NFκB-mediated transcriptional control. Figure 12E shows the corresponding effect of cancer cell population, where enhanced ligand–receptor binding strength leads to accelerated tumor growth, demonstrating the pro-tumoral influence of excessive receptor activation. Figure 12F presents the probability distribution of the equilibrium \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) values obtained from all 10,000 simulations, showing a unimodal yet broadened profile that quantifies the inherent variability caused by kinetic uncertainty.

A Three-dimensional sensitivity surface showing the combined effect of \({b}_{2}^{+}\) and \({b}_{2}^{-}\) on \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\). Dependence of the steady-state complex \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) on the association (B) and dissociation (C) rate constants. Dependence of the cytokine [L5] level (D) and cancer cell population (E) on \({b}_{2}^{+}\) and \({b}_{2}^{-}\). F Distribution of the final \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) concentrations obtained from all Monte Carlo runs, illustrating variability due to kinetic uncertainty. n = 10,000 Monte Carlo samples; log-uniform parameter sampling.

Finally, to assess the stochastic sensitivity of the \([D]+[{R}_{2}]\rightleftharpoons [\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) binding kinetics, Monte Carlo simulations are performed with 10,000 random samples of the association (\({b}_{3}^{+}\)) and dissociation (\({b}_{3}^{-}\)) rate constants drawn from log-uniform distributions. The simulation results provide a quantitative understanding of how variability in decorin-receptor interactions influences downstream signaling and tumor progression under asthmatic conditions (Iasthma = 1). Figure 13A–C illustrates the direct effect of the kinetic parameters on the equilibrium concentration of the \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) complex. In Fig. 13B, the complex level increases with the higher \({b}_{3}^{+}\), reflecting the enhanced binding propensity of decorin to [R2]. Figure 13C shows that an increase in \({b}_{3}^{-}\) significantly decreases the steady-state complex concentration due to accelerated dissociation. Changes in \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) in response to stochastic perturbations in \({b}_{3}^{-}\) and \({b}_{3}^{+}\) are larger than the previous two kinetics in Figs. 11 and 12. The combined parameter dependence in Fig. 13A reveals a distinct nonlinear surface, where strong binding (high \({b}_{3}^{+}\), low \({b}_{3}^{-}\)) produces the largest \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) accumulation, suggesting that stable decorin–receptor engagement is critical for sustaining the signaling pathway. Figure 13D demonstrates that a decrease in \({b}_{3}^{+}\) or an increase in \({b}_{3}^{-}\) leads to an elevation in [L5] production, indicating that decorin binding kinetics indirectly modulates the [L5]-associated cytokine feedback loop via NFκB and microglia. Figure 13E shows that high D−R2 binding affinity correlates with reduced tumor growth, consistent with the tumor-suppressive role of decorin-mediated receptor signaling observed in experiments21. Finally, Fig. 13F summarizes the overall distribution of the final \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) concentrations from all Monte Carlo runs, exhibiting a right-skewed unimodal pattern that reflects the nonlinear sensitivity of the system to stochastic variations in reaction rates.

A Three-dimensional sensitivity surface showing the combined effect of \({b}_{3}^{+}\) and \({b}_{3}^{-}\) on \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\). Dependence of the steady-state complex \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) on the association (B) and dissociation (C) rate constants. Dependence of the cytokine [L5] level (D) and cancer cell population (E) on \({b}_{3}^{+}\) and \({b}_{3}^{-}\). F Distribution of the final \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) concentrations obtained from all Monte Carlo runs, illustrating variability due to kinetic uncertainty. n = 10,000 Monte Carlo samples; log-uniform parameter sampling.

A series of Monte Carlo simulations (10,000 samples) are performed to quantify the sensitivity of the ligand–receptor binding kinetics ([L4] + [R1], [L4] + [R2], and [D] + [R2]) to stochastic variations in their association and dissociation rates. The results consistently revealed that strong binding affinity (high association rate, low dissociation rate) enhances complex formation and downstream cytokine activity, whereas weak binding attenuates signaling and tumor cell growth, emphasizing the critical role of receptor-level kinetic heterogeneity in modulating the overall tumor microenvironment response.

To account for the intrinsic stochasticity arising from discrete molecular interactions in small reaction volumes, the Gillespie stochastic simulation algorithm (SSA)37,38,39 is employed to describe the reversible binding process between ligand [L4] and receptor [R1]:

Since Gillespie’s method operates on discrete molecule counts, the molar concentration [L4] and [R1] are converted to molecule number \({N}_{[{L}_{4}]}\) and \({N}_{[{R}_{1}]}\), using the relation NX = X × NA × V, where NA is Avogadro’s number (=6.022 × 1023) and V is reaction volume (=5 × 10−15)40. Accordingly, the association rate constant with molar unit \({b}_{1}^{+}\) (units: μM−1 h−1) is converted to the molecular stochastic rate \({k}_{1}^{+}={b}_{1}^{+}/({N}_{{\rm{A}}}V)\) (units: molecule−1 h−1), while the dissociation rate constant \({k}_{1}^{-}\) retains its unit of h−1. In the Gillespie framework, the propensities of the forward and reverse reactions are therefore

where Ni (\(i=[{L}_{4}],[{R}_{1}],[\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\)) denotes the dimensionless molecular copy number of each species. Thus, the units of \({k}_{{\rm{on}}}^{{L}_{4}{R}_{1}}\) and \({k}_{{\rm{off}}}^{{L}_{4}{R}_{1}}\) are h−1, and the time to the next reaction event(τ) is sampled from an exponential distribution:

where r1 ∈ (0, 1) is a uniformly distributed random number. The reaction channel (association or dissociation) is then chosen according to the probability \(\frac{{k}_{on}^{{L}_{4}{R}_{1}}}{{k}_{on}^{{L}_{4}{R}_{1}}+{k}_{off}^{{L}_{4}{R}_{1}}}\). The initial concentrations of [L4] and [R1] are set to 0.05 μM, corresponding to \({N}_{[{L}_{4}]}={N}_{[{R}_{1}]}\approx 150\) molecules per species (150 ≈ 0.05 × 10−6 × NA × V)41. This formulation guarantees that the stochastic simulation remains dimensionally consistent with the original biochemical rate constants.

Deterministic trajectories are obtained by numerically integrating the mass-action ODEs, whereas stochastic trajectories are generated using the Gillespie direct algorithm, which explicitly samples the time to each reaction event based on probabilistic reaction propensities. For each reaction, 500 stochastic realizations are performed to visualize the range of molecular fluctuations. The temporal dynamics of the reaction \([{L}_{4}]+[{R}_{1}]\rightleftharpoons [\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\) is shown in Fig. 14A, where the time courses of molecule concentrations (solid curves; \([{L}_{4}],[\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\)) from the deterministic system are overlaid with stochastic trajectories (shadows) representing individual realizations. Similar settings are applied to the other ligand–receptor binding reactions (\([{L}_{4}]+[{R}_{2}]\rightleftharpoons [\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) and \([D]+[{R}_{2}]\rightleftharpoons [\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\)), where each reaction is implemented using the Gillespie SSA under identical computational conditions. All parameters and state variables in these reactions are consistently converted from molar concentrations to molecule-based units to ensure accurate representation of discrete molecular interactions within a confined intracellular volume. Figure 14B and C shows the binding processes of \([{L}_{4}]+[{R}_{2}]\rightleftharpoons [\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\), \([D]+[{R}_{2}]\rightleftharpoons [\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\), respectively. In all cases, the simulations from the deterministic system well represent the expected mean-field kinetics, while the stochastic system exhibits noticeable temporal fluctuations due to discrete reaction events and random timing between association and dissociation processes. The ensemble of stochastic trajectories converges to the deterministic mean, confirming model consistency while emphasizing the influence of intrinsic molecular noise in low copy number regimes. These findings demonstrate that ligand–receptor interactions associated with stochastic variability may become functionally relevant in developing anti-tumor therapy in confined TME domains.

Gillespie algorithm-based stochastic simulation of the reversible reaction \([{L}_{4}]+[{R}_{1}]\rightleftharpoons [\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{1}}]\) (A), \([{L}_{4}]+[{R}_{2}]\rightleftharpoons [\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) (B), and \([D]+[{R}_{2}]\rightleftharpoons [\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) (C), showing intrinsic molecular noise around the deterministic mean.

Asthma-induced suppression of optic glioma formation

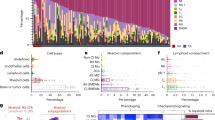

In Fig. 15, we investigate how an asthma attack in the lung can shape the immune microenvironment of the optic glioma in the brain through priming the T cells in the blood circulation. Asthma-induced inflammation leads to the reprogramming of T cells, so-called re-T cells, with high expression of decorin21, a key regulator in the brain TME42. In the absence of asthma, T-cell deficiency, and the decorin-free condition (red dashes, Fig. 15B) induces the \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\)-mode (high \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) and low \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\); red dashed curve in Fig. 15C) in the core binding receptor system, thus tight up-regulation of NFκB (blue in the left column, Fig. 15D) in microglia. The beginning and end points of the solution curve (\([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}](t)\), \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}](t)\)) are marked in ‘B’ and ‘E’ in the pink \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\) box in Fig. 15C. This low decorin index (RDe; red in the left column, Fig. 15D) and elevated production of CCL5 from microglia (blue in the left column, Fig. 15E) essentially lead to fast growth of optic glioma in brain (red dashes, Fig. 15F). On the other hand, an increasing population of the re-T cells in brain (blue solid line, Fig. 15A) from asthma attack with accumulating decorin (blue solid, Fig. 15B) leads to convergence of the solution in the receptor module to the \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\)-mode (low \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) and high \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\); blue curve in Fig. 15C). The location at the final time was marked in ‘E’ in the blue \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\) box in Fig. 15C. This substantial elevation in the decorin level on microglia from asthma-induced T cell reprogramming is a crucial factor in modulating the tumor-associated signaling pathway, increasing RDe (red, 2nd column, Fig. 15D). This shift from \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\) to \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\) mode reduces the availability of CCL4–CCR8, a central activator of the NFκB pathway, thereby down-regulating NFκB signaling (blue, 2nd column, Fig. 15D) and suppressing secretion of CCL5 on microglia (red, Fig. 15E). Thus, the system eventually inhibits tumor growth in the presence of asthma (blue solid, Fig. 15F). This finding aligns well with experimental data21, reinforcing the observation that asthma-induced immune reprogramming can effectively disrupt tumor-promoting pathways. These results suggest that the decorin-mediated suppression of NFκB can mediate a protective effect of asthma on the onset of optic glioma and asthma, despite its well-documented inflammatory nature, and can exert an unexpected tumor-suppressive effect as described in ref. 21.

Time courses of densities of the re-T cells (A) and decorin levels (B) in response to the onset of the asthma attack (solid) compared to control (dashed, no asthma). C Dynamics of the core control (\([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\), \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\)) system in the phase plane and phenotypic transition in the presence and absence of asthma. D Expression level of NFκB and the decorin index (RDe) at the final time. E Comparison with experimental data (red): Asthma attack suppresses CCL5 expression by microglia. F Time courses of the tumor population in both cases.

In Fig. 16, we investigate the impact of the frequency of asthma attacks on the immune changes in the TME in the brain and optic glioma progression. In order to take into account the periodic asthma attacks with a period τa, we modify Eqs. (29) and (30) as follows:

where Na is the number of total asthma attacks, τa = ti+1 − ti, i = 1, …, Na−1, hA is the time duration of an asthma attack, and I[a, b]( ⋅ ) is the indicator function that gives 1 on the time interval [a, b] and 0 otherwise. A relatively frequent asthma attack (τa = 5 days, red, Fig. 16A) induces a large population of re-T cells (red solid, Fig. 16B) and over-expressed decorin in the brain immune environment (red solid, Fig. 16C), maintaining the system in the \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{a}\)-mode (red solid, Fig. 16D) with a consistently high decorin index (RDe(t) > 1, red in Fig. 16E) and down-regulation of NFκB (solid red in Fig. 16G) and CCL5 (solid blue in Fig. 16G). Thus, the asthma-induced, sustained anti-tumorigenic environment (blue box, bottom (τa = 5), Fig. 16H)) leads to suppression of optic glioma (red solid, Fig. 16F) compared to fast tumor growth in controls (no asthma, black dotted, Fig. 16F). On the other hand, a system exposed to less frequent asthma symptoms (once a month, τa = 30 days) only generates two peaks of re-T cells (blue dashed, Fig. 16B), expression level (blue dashed, Fig. 16C) and index (blue dashed, Fig. 16E) of decorin during 60 days. Thus, the cumulative impact of these immune-modulating cycles between \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\)- and \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\)-modes (blue dashed, Fig. 16D) leads to fluctuations in NFκB and CCL5 secretion. Thus, a reduction in tumor burden during an asthma attack with the system in a \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\)-mode leads to slower tumor growth (blue dashed, Fig. 16F) compared to control (black dotted, Fig. 16F), but still a tumor develops under the larger degree of asthma-free conditions in the \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\)-mode (pink boxes, τa = 30, Fig. 16H). Figure 16H illustrates phenotypic changes in response to various periods of asthma attacks (τa = 5, 10, 20, 30 days). As τa is increased, the TME selects the frequent temporal immune transitions in preference to all time \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\)-mode. For instance, in response to asthma attacks every 5–10 days, the cancer cell population is reduced by more than 25% compared to the control (no-asthma) condition, highlighting the potential tumor-suppressive role of asthma-induced immune reprogramming in the optic glioma microenvironment.

A Temporal changes in asthma attacks for two cases (τa = 5, 30). Time courses of the concentrations of the re-T cells (B), decorin (C), decorin index (E), normalized tumor populations relative to control (F), and NFκB/CCL5 (G), and internal dynamics in the phase plane (D) in response to asthma stimuli in A. H Phenotypic changes of microglia in response to a periodic asthma attack with various τa (τa = 5,10,20,30).

Therapeutic approach

We now investigate the effect of re-T cell infusion on tumor dynamics. Recent advances in adoptive cell therapy demonstrated the potential of transferring functionally specialized T cells to modulate tumor immunity, most notably through tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy, where patient-derived T cells from the tumor site are expanded ex vivo and re-infused to target cancer cells43,44,45,46. We assume that re-T cells are injected over time intervals [ti, ti + hT], i = 1, ⋯ , Nt with the duration hT, injection strength sT, and a period τt(=ti+1−ti, ∀ i = 1, ⋯ , Nt−1). Here, Nt is the total number of re-T cell injections. Thus, we have the following for the injection rate of re-T cells (uT(t)) in Eq. (30) during 60 days:

Figure 17B and C shows time courses of the concentrations of re-T cells (Fig. 17B) and decorin (Fig. 17C) in response to two injection schemes (τt = 5(red), 20(blue), Fig. 17A) while the total amount of infused re-T cells is fixed. With the frequent injection scheme (τt = 5), the intercellular system pushes the solution \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}](t),[\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}](t)\) to the anti-tumorigenic phase (Fig. 17D) and maintains the high RDe index (red, Fig. 17E). The relatively low, fluctuating levels of the NFκB along the solution trajectory (Fig. 17D), thus steady \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\)-status (τt = 5, Fig. 17H) lead to suppression in tumor growth (red, Fig. 17F) via suppressed CCL5 levels. On the other hand, injection of the larger population of re-T cells every 20 days (blue dashed, Fig. 17B) induces higher expression of decorin and a larger decorin index (RDe; blue dashed, Fig. 17E) at peak points. However, the less frequent schedule (τt = 20) pushes the dynamic system to the \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\)-mode (curves on the bottom, Fig. 17G) in the lower mode of RDe fluctuation (Fig. 17E, \({{\mathbb{T}}}_{{\rm{a}}}=\{t\in [0,60]:{R}_{{\rm{De}}}(t) < 1\}={\sum }_{j}^{4}{{\mathbb{T}}}_{{\rm{a}},j}={\sum }_{j}^{4}[{t}_{2j-1},{t}_{2j}]\), t1 = 0, t8 = 60). The suppressed NFκB (Fig. 17G; \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\) regions in Fig. 17H) over these multiple time intervals (\({{\mathbb{T}}}_{{\rm{a}}}={\sum }_{j}^{4}{{\mathbb{T}}}_{{\rm{a}},j}\)) leads to a cycle of growth and suppression of the optic glioma (blue dashed, Fig. 17F) via up- and down-regulation of CCL5. These results imply that, given constant resources of re-T cells, the scheduling of injection can make a significant difference in controlling the onset of the optic glioma via the immunosuppressive efficacy of re-T cells and the downstream tumor-promoting signaling mediated by CCL5. These findings provide quantitative evidence supporting strategically timed re-T cell therapies as a potential immunomodulatory approach for controlling optic glioma progression.

A Injection rate of re-T cells (uT) with different periods (τt = 5, 20). Time courses of the concentrations of re-T cells (B), decorin (C), expression levels of decorin (B) RDe (E), and normalized tumor cell populations (F) in response to re-T cell injection in (A). Expression levels of NFκB along the solutions trajectories with τt = 5 (D) and τt = 20 (G) over a time cycle [0, 20] in the \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]-[\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) plane. H Temporal changes between \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\) and \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\) modes with various τt (τt = 5, 10, 20, 30).

Although TIL therapy has shown remarkable clinical efficacy in some cancers, its broader application is limited by the technical challenges and time required for ex vivo expansion. To overcome these limitations, an alternative strategy involves administering IL-2 directly to support the proliferation and activation of both endogenous T cells and therapeutically infused reprogrammed T cells (re-T cells)47,48,49. This method retains the immuno-stimulatory benefits of IL-2 while avoiding the logistical hurdles of ex vivo manipulation, potentially enabling a more streamlined and accessible immunotherapy. In order to test the effect of IL-2 on anti-tumor efficacy, we introduce a new variable I for the concentration of IL-2 and use a modified version of Eqs. (29) and (30) in the absence of re-T cells injection, for the densities of T cells and re-T cells and IL-2 concentration (I) as follows:

where a1 is the enhancement rate by IL-2 in the growth terms in T cells and re-T cells with Hill coefficients (\({a}_{2}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{+}\), \(k\in {{\mathbb{Z}}}^{+}\)), uI(t) is injection rate of IL-2, and μI is the natural decay rate of IL-2. In the simulation, IL-2 is injected over time intervals [ti, ti + hI], i = 1, ⋯ , NI with a duration hI, the base injection rate sI, and the fixed period τI( = ti+1−ti, ∀ i = 1, ⋯ , NI−1). Here, NI is the total amount of IL-2 dose. Thus, we have the following for the injection rate of IL-2 (uI(t)) in Eq. (12):

Figure 18A shows the anti-tumor efficacy of the IL-2 treatment for various injection period τI and total amount of IL-2 dose (TIL−2). While the total amount of IL-2 administered remains constant in a given row, the injection rate for each administration is changed according to the injection period. For a fixed period (τI), the total injection dose is positively correlated with anti-tumor efficacy. However, there is a jump in anti-tumor efficacy from low efficacy to high efficacy as TIL-2 is increased. While the injection amount (TIL-2) is too low, the IL-2 infusion is not able to suppress the onset of the optic glioma (blue, bottom rows, Fig. 18A) regardless of periods. On the other hand, the IL-2 treatment is effective in suppressing tumor growth for all periods when the total dose is large enough (yellow, top rows, Fig. 18A). For TIL-2 between 100 and 200 IU/ml, the anti-tumor efficacy curve illustrates the nonlinear feature, attaining the maximal outcomes for intermediate periods. For instance, when TIL-2 = 150 IU/ml (Fig. 18B), the cancer cell population at the final time decreases initially as τI increases (τI = 5 → 9) but increases again after passing the critical period point (τI > 13). Thus, an intermediate value (e.g., τI = 9) leads to the maximal anti-tumor efficacy. When TIL-2 = 110 IU/ml (Fig. 18C), the smaller injection period tends to show low anti-tumor efficacy overall, but it shows strong nonlinearity in the intermediate values of τI. For instance, the cancer cell population for τI = 13 is lower than the population for τI = 14. The injection of IL-2 every 15 days leads to the best anti-tumor outcomes (black arrow, Fig. 18C). In Fig. 18D–I, we investigate the dynamics of the system of three cases in Fig. 18B (τI = 13,14,15) in detail for a fixed amount of IL-2 (110 IU/ml). The injection of IL-2 with the different periods (τI = 13,14,15 with injection rates sI = 22, 22, 27.5 IU/(ml days), respectively) provides different temporal profiles of IL-2 concentration (Fig. 18D) and a fluctuating population of re-T cells (Fig. 18E) in the TME. When IL-2 was injected every 15 days (τI = 15, sI = 27.5 IU/(ml days)), the larger presence of re-T cells in TME maintains more anti-tumorigenic phases (Fig. 18H) compared to other cases (τI = 13, Fig. 18F; τI = 14, Fig. 18G) due to down-regulation of \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) and up-regulation of \([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) for most of the time, thus suppressing NFκB (Fig. 18K) and reducing tumor growth (black dotted curve, Fig. 18L) significantly. On the other hand, the relatively lower number of re-T cells from more frequent injection with lower doses (blue and red, Fig. 18E) induces the system to stay longer in the tumorigenic status (Fig. 18F and G) and leads to up-regulation of NFκB and faster tumor growth (blue and red, Fig. 18L). Despite the same total amount of IL-2, the injection with τI = 13 (blue, Fig. 18D) results in slower tumor growth compared to the case with τI = 14 (Fig. 18L) due to larger peaks of the re-T cell population and a longer stay in the \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{a}\) mode. These findings indicate that more frequent IL2 injections with shorter resting intervals-even at the same dose and number of administrations- may significantly enhance therapeutic effectiveness.

A Anti-tumor efficacy in response to IL-2 infusion with various injection periods (τI, days) and total amount of IL-2. Scaled tumor size at final time for various τI (5 ≤ τI ≤ 20) when the total amount of IL-2 is fixed (150 IU/ml (B) and 110 IU/ml (C)). Time courses of the concentrations of IL-2 (D) and CCL4–CCR8 and DCN–CCR8 complexes (F–H), population of re-programmed T cells (E), NFκB levels on the phase plane (I–K), and normalized tumor cell populations (L) in response to IL-2 injection with three different periods (τI = 13, 14, 15) with a fixed total amount (110 IU/ml).

Although higher doses per injection may improve anti-tumor efficacy (Fig. 18), practical considerations such as side effects and treatment cost highlight the importance of developing strategies that maximize therapeutic benefits using minimal dosing. Therefore, we now investigate an optimal IL2 treatment protocol through systematic analysis. For each injection rate of IL-2, we identify the second optimal injection time (t2) to maintain the \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{a}\) mode after initial injection of IL-2 at t = t1. Figure 19A shows the waiting time distribution, i.e.,\({\tau }_{{\rm{I}}}^{\ast }={\tau }_{{\rm{I}}}^{\ast }({s}_{{\rm{I}}})={t}_{2}-{t}_{1}\). For instance, when \({\tau }_{{\rm{I}}}^{\ast }\)=25.2, the fluctuating re-T cell population (dashed red, Fig. 19C) from the second injections of IL-2 after 13.25 days (\({\tau }_{{\rm{I}}}^{\ast }=13.25\)) induces strong decorin receptor binding to keep the solution trajectory in \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\) phase (dashed red, Fig. 19D) over the time interval [0, t2 + ϵ] (ϵ > 0, small). In this case, other injection time points ti (i = 3…, red dashed, Fig. 19E) can also be determined by monitoring the solutions \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}](t),[\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}](t)\) to remain in the anti-tumorigenic state for all time (red dashed, Fig. 19D) via corresponding peaks of re-T cells (red dashed, Fig. 19C). A routine injection of IL-2 with the smaller fixed period (\({\tau }_{{\rm{I}}} < {\tau }_{{\rm{I}}}^{\ast }\); τI = 9, blue circle in Fig. 19A) according to Eq. (13) after the initial injection can also maintain \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\) mode (blue, Fig. 19D) via higher peaks in re-T cells supply (blue, Fig. 19C) but with more administrative costs and possible side effects due to the larger total amount of IL-2. However, a period injection of IL-2 with \({\tau }_{{\rm{I}}} > {\tau }_{{\rm{I}}}^{\ast }\) (τI = 18, yellow triangle, Fig. 19A) is not strong enough to activate re-T cells (yellow dotted, Fig. 19C) the solution \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}](t),[\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}](t)\) in the intracellular module on microglia transits between \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\)- and \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\)-modes (yellow dotted, Fig. 19D). While \({\tau }_{{\rm{I}}}^{\ast }\) is increased as dose is increased, \({\tau }_{{\rm{I}}}^{\ast }\) remain almost constant for larger sI (sI > 25.2, Fig. 19A), indicating similar anti-tumor efficacy despite higher costs. Even if an optimal schedule can be chosen for various IL-2 injection rates (sI) in Fig. 19A, each dose lead to a different total amount of IL-2 in the 60-day treatment window (Fig. 19B). For instance, higher single-dose injections lead to accelerated, rapid expansion of the re-T cell population and sustained \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\)-mode due to higher decorin levels, but this also results in the higher total injection amount, thus the higher cost and an increase in side effect potential. Thus, it is beneficial for clinics to reduce cost when the clinical outcome is similar. Figure 19E–I illustrates the system dynamics in response to three injection schedules of IL-2 (sI = 20 (red), 25.2 (red), 40 (black)). While the three cases induce different temporal profiles of IL-2 (Fig. 19E) and re-T cells (Fig. 19F), the solution stays in the \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\) mode (Fig. 19G), leading to sustained, low CCL5 levels (Fig. 19H), thus suppression of tumor growth (Fig. 19I). However, the injection with a rate of 25.2 IU/ml (\({\tau }_{{\rm{I}}}^{\ast }=13.25\,{\rm{days}}\)) minimizes the cost (red dot, Fig. 19B). Thus, this minimizing strategy can be the most efficient therapeutic strategy in the clinic. However, considering that optic glioma predominantly affects pediatric patients, minimizing the per-injection dose—even at the expense of shorter injection intervals—may be more favorable in terms of patient quality of life.

A The waiting time distribution of the second injection \({\tau }_{{\rm{I}}}^{\ast }={\tau }_{{\rm{I}}}^{\ast }({s}_{{\rm{I}}})={t}_{2}-{t}_{1}\) after the first injection of IL-2 to maintain the \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\) mode for various injection rates (sI). B Total amount of IL-2 corresponding to the cases in (A). Time courses of re-T cells (C) and solution trajectories in the phase plane (D) for three cases (τI = 9 (O), 13.25 (x), 18 (Δ) in A). Time courses of IL-2 level (E), re-T cell population (F), trajectories of solutions in the phase plane (G), CCL5 levels (H), and scaled cancer cell populations (I) in response to three (blue, red, black dots) IL-2 infusions in (B).

Discussion

Previous studies suggested the strong correlation between asthma (or other immune diseases such as allergy or atopy) and low risk of developing brain tumors based on clinical observations and epidemiological data50,51,52,53. For instance, Roncarolo et al. and other researchers demonstrated the negative association between asthma and brain tumors in children50,54,55,56,57. In particular, experimental evidence suggested that asthma-induced T cells with decorin expression may suppress the formation and progression of optic glioma, the most common brain tumor among children21,58. However, the fundamental mechanism of the negative correlation between asthma development and the incidence of brain tumors in children has not been clearly understood.

In this work, we showed that optic glioma risk can be modulated by alterations in asthma-induced T cell function by interfering with immune-tumor interactions in brain TME. By inhibiting the conventional CCL4–CCR8–NFκB axis on microglia and reducing CCL5 production, asthma-driven decorin on these re-T cells plays an important role in suppressing glioma growth. T cells in brain TME mediates Nf1-optic glioma growth in mice, and in T cell-deficient mice, a tumor is not formed by murine optic glioma stem cells59. Thus, a new type of primed T cell changes the tumor growth dynamics. We investigated how midkine from the optic nerve induces tumor growth due to CCL5 secretion by microglia13,60 by carrying the conventional receptor binding (CCL4–CCR5, CCL4–CCR8) and activation of NFκB (tumorigenic phase (\({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\)); Figs. 2–4)9 and how secretion of decorin from populated asthma-induced re-T cells in brain TME21 can induce up-regulation of the DCN–CCR8 complex (\([\overline{D\cdot {R}_{2}}]\)) and down-regulation of \([\overline{{L}_{4}\cdot {R}_{2}}]\) (anti-tumorigenic mode; \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\)), leading to suppression of both NFκB and CCL5 which in turn induces an anti-tumorigenic mode (Figs. 7–9). This study identifies a novel anti-oncogenic mechanism by which asthma-induced T cell reprogramming exerts a protective effect against the progression of optic glioma through modulation of the tumor microenvironment. Specifically, asthma-assisted re-T cells secrete decorin, which inhibits CCL4–CCR8 complex formation by competitively binding to CCR8, thereby reducing NFκB-mediated upregulation of CCL5, a cytokine known to enhance glioma cell proliferation. This asthma-induced effect on tumor suppression (Fig. 15) was consistently observed in experiments21. Since the relative balance of binding between CCL4–CCR8 and DCN–CCR8 component leads to the critical decorin index, RDe (in Eq. (3), to determine the suppression and enhancement of the optic glioma (Fig. 8), fluctuation in decorin in TME may change overall anti-tumor efficacy. We found that the intracellular system on microglia illustrates different dynamics on the key transition between \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{t}}}\)- and \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{{\rm{a}}}\)-modes, thus anti-tumor efficacy, in response to repeated asthma attacks with various periods (Fig. 16). Thus, patient-specific treatment or prevention protocols can be created when enough data and experiments on the more detailed mechanism are accumulated.

These findings offer novel insights into the complex interplay between systemic immune responses and tumor dynamics, potentially paving the way for new therapeutic strategies that harness the protective effects of asthma-induced immune modulation. Recent advances in adoptive cell therapy have demonstrated the potential of transferring functionally specialized T cells to modulate tumor immunity, most notably through tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy, where patient-derived T cells from the tumor site are expanded ex vivo and re-infused to target cancer cells43,44,45,46. By isolating these asthma-induced re-T cells from peripheral blood or lymphoid tissue, it may be possible to expand them ex vivo using cytokine stimulation (e.g., IL-2 or anti-CD3/CD28)61,62. Thus, a novel new approach could involve isolating asthma-primed CD8+ T cells, which naturally acquire a tumor-suppressive phenotype through chronic inflammatory conditions. Computational modeling revealed that optimal IL-2 delivery can amplify the population of these re-T cells in brain TME, supporting decorin-mediated anti-tumor effects (Fig. 17). When testing the anti-cancer efficacy of IL-2 administration, intriguingly, a more frequent and moderate dosing schedule yields efficient tumor suppression under constant total IL-2 amount (Fig. 18). These findings suggest a critical interplay between immune modulation, cytokine dynamics, and dosing strategies in shaping tumor outcomes in inflammatory contexts such as asthma.