Abstract

Despite the expanding landscape of clinical trials, there is a lack of study concerning Malaysian patients’ participation and perspectives. This study addresses these gaps by assessing patients’ willingness, knowledge, perceptions, confidence, and religious barriers related to clinical trial participations at Sarawak General Hospital. We conducted a cross-sectional survey from March to September 2022 on 763 cancer and non-cancer patients. We collected patients’ responses and calculated scores for willingness to participate (40.5/100), knowledge (29.9/100), perceived benefits (66.5/100) and risks (72.4/100) of participations, confidence in clinical trial conducts (66.3/100), and religious barriers (49.8/100). The higher scores indicated greater willingness, better knowledge, stronger perceptions of benefits and risk, increased confidence, and stronger religious barriers. Cancer patient demonstrated significantly greater willingness for trials involving new drugs (31.9/100 vs. 27.4/100, p = 0.021) but slightly higher religious barriers compared to non-cancer cohort (51.4/100 vs. 48.3/100, p = 0.006). Multivariable logistic regression identified female gender, unemployment, poor knowledge, low perceived benefits, high perceived risks, and low confidence as significant factors associated with reduced willingness to participate (p < 0.05). This study underscores the challenges in engaging Malaysian patients in clinical trials, particularly in Sarawak, emphasising the need for targeted strategies to raise awareness, effective communication, and enhancing public confidence in clinical trials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Participant recruitment rate is a major barrier to clinical trial completion. A study showed that only one-third of the approved trials met their original recruitment goals, and half of the trials had to be extended1. Inadequate recruitment can result in an underpowered trial, which increases the risk of prematurely abandoning a potentially effective treatment before its actual clinical effect has been determined. Consequently, participants may be exposed to the uncertain effects of a trial intervention, but the true effect of the trial intervention cannot be determined and raises ethical concerns2.

In Malaysia, over 1800 industry-sponsored research were conducted in the Ministry of Health (MOH) facilities from 2012 to 20213. Malaysia has a large, multi-ethnic population, which provides inherent advantages in terms of genetic diversity for clinical trials. In recent years, the Malaysian government has made efforts to expand the capacity for clinical research. The availability of medical experts and qualified investigators, as well as ethical review and regulatory frameworks for clinical research, all contribute to the growth of Malaysia’s clinical trial industry3,4,5.

Although there is a growing need for, and an increasing number of clinical trials, there is a lack of study on clinical trial participation and patients’ perspectives in Malaysia. Sarawak General Hospital (SGH) as the largest hospital in Sarawak, Malaysia, serves a catchment area of 2.5 millions people. It is also one of the primary clinical trial centres and the first accredited first-in-human trial site in Malaysia4. In this study, we conducted a survey with patients visiting SGH to evaluate their perspectives on clinical trial participation. We assessed their willingness to participate in clinical trials. knowledge, perceived benefits and risks of participations, confidence in clinical trial conducts, and religious barriers that may hinder their participations. We also determined the factors associated with their willingness to participate in clinical trials.

Methods

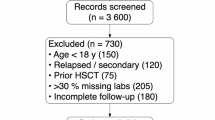

This study was conducted between March 18 and September 20, 2022. We collected responses from adult patients visiting oncology, neurology, respiratory, and endocrinology clinics in SGH during the study period. We excluded individuals who were under the age of 18, those who were illiterate or unable to understand the questionnaire in English, Malay, or Chinese, and those who were mentally incapable to answer the questionnaire. The study protocol was approved by the Medical Research and Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health of Malaysia (NMRR ID-22–00180-FCT) and was conducted in compliance with the Malaysian Guideline for Good Clinical Practice and Declaration of Helsinki. The participants provided their informed consent prior to participating in the study.

We developed and validated a questionnaire called JoinCT Questionnaire, available in three languages: English, Bahasa Malaysia, and Chinese. The development process began with a comprehensive literature review to identify key factors influencing willingness to participate in clinical trials. Content validity was assessed by three subject matter experts—a principal investigator with extensive clinical trial experience and two senior researchers—who evaluated the relevance and validity of each item. Feedback was reviewed and refined until consensus was reached. The original English questionnaire was then translated into Bahasa Malaysia and Chinese using forward and backward translation to ensure linguistic accuracy and consistency across all versions. A pilot study conducted among the oncology cohort demonstrated excellent reliability (Cronbach’s alpha ≥ 0.937) and strong model fit. Full details of the development and validation process can be found in a previously published study6.

In the questionnaire, the participants would rate their willingness to participate in a clinical trial in five scenarios: clinical trials involving a new, unmarketed drug, new indication for marketed drugs, new medical device, new medical procedure, or general clinical trials, on a 10-point numeric scale. We multiplied the score for willingness in each clinical trial scenario by a factor of 10 and then computed the average of these sub-scores across the five scenarios to determine the overall willingness score. A cutoff of > 70/100, corresponding to the 85th percentile of responses, was decided to indicate high willingness to participate in clinical trials.

The participants’ knowledge of clinical trials was evaluated with eight questions; each correct answer would be awarded one point and each incorrect or uncertain response would be awarded zero point. In addition, they would provide their responses about their perceptions of benefits and risks of participating in clinical trials, their confidence in the conduct of clinical trials, and religious barriers, on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. We converted the Likert scale responses into numerical values, with ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ being assigned one to five points, respectively. To calculate the scores, we summed the points obtained in each domain, divided the total by the maximum points, and multiplied the result by 100. The higher scores indicated a greater willingness to participate, better understanding of clinical trials, stronger perceptions of both the benefits and risks, increased confidence in clinical trial conduct, and more significant religious barriers.

In this study, we also collected respondents’ socio-demographic information, cancer status, prior exposure to clinical trials, and participation history. In addition, the respondents would rate their current health status and their relationship with their healthcare providers on a 10-point numeric scale.

Categorical variables, such as gender and other demographics, were reported as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables, such as scores, age, self-rated health status, and relationship with healthcare providers ratings were reported as means and standard deviations. We used independent t-test to compare scores (assuming normal distribution) between cancer and non-cancer patients. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine the factors associated with a high willingness (> 70/100) to participate in clinical trials. The significant variables from the univariable analysis were included in two multivariable models. Model 1 comprised the significant socio-demographic factors and clinical trial knowledge score. Model 2 included all the variables from Model 1, along with the scores for perceived benefits, perceived risks, confidence in clinical trial, and religious barriers to clinical trial participation. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In 2021, SGH recorded 21,767 patient visits to the oncology clinic. For the cancer cohort in this questionnaire study, a sample size of 377 respondents was calculated to achieve a 95% confidence level with a 5% margin of error. Similarly, a sample size of 377 respondents was estimated for the non-cancer cohort, resulting in a combined total sample size of at least 754 respondents for both cohorts.

Results

A total of 763 patients responded to the questionnaire and were included for analysis. The mean age was 51.5 (standard deviation 15.4) years and approximately one-third were female. The majority were Chinese (37.6%) and Malay (30.4%) ethnicity. More than 98% of the respondents claimed to have a religion, with Christians (42.6%) and Muslims (34.2%) being the two largest religious groups. Most of them had received secondary or higher education (80.2%) and were unemployed (53.9%), with 64.6% earning less than RM1200 (~ USD270) per month (Table 1).

Among the respondents, 51.2% had cancer and were from the oncology clinic and the rest were from the neurology (16.8%), endocrinology (16.6%), and respiratory (15.3%) clinics. The majority of the cancer patients had breast cancer (34.9%), followed by colorectal (12.3%), lung (11.3%), and nasopharyngeal (9.5%) cancers; over one-third of them were in stage IV (Supplementary materials, Table S1).

Approximately 40% of respondents had prior exposure to clinical trials, with most learning about clinical trials through doctors (11.1%), social media (9.2%), or family and friends (9.0%). Additionally, only 8.1% had participated in a trial before. Respondents rated their health at a mean value of 6.6/10 and their relationship with healthcare providers at a mean value of 8.2/10 (Table 1).

The respondents reported a mean willingness score of 40.5/100 for participating in clinical trials, with only 13% achieving a high willingness score (> 70/100). They were least willing to participate in trials involving new, unmarketed drugs (29.7/100), but most willing for trials involving medical devices (44.5/100) (Table 2).

Our study respondents showed poor clinical trial knowledge, with a mean score of only 29.9/100 (Table 3). In the post-hoc analyses, significant differences of knowledge score were found across various socio-demographic factors such as ethnicity, religion, education level, employment status, and income (Supplementary materials, Table S2).

Table 4 presents our patients’ perceptions, confidence in clinical trials, and religious barriers hindering their clinical trial participation. The scores for perceived benefits and perceived risks of clinical trial participations are 66.5/100 and 72.4/100, respectively. It is worth mentioning that the statement on receiving monetary benefits is an advantage, received the lowest proportion of agreement, with only about 30% of participants agreeing to it. Besides that, only 28.4% of them agreed that the benefits of participating in clinical trials outweighed the associated risks. In contrast, the majority of patients (60–70%) acknowledged potential risks related to clinical trial participation, including concerns about safety, perceived ineffectiveness, discomforts, giving up certain rights, and the burden of participation. (Table 4).

The score for confidence in clinical trial conducts is 66.3/100. However, less than half of the respondents (40–45%) agreed with the statements in regarding their confidence in clinical trials conducts, including ethical standards and qualification of investigators, safety of participation, and patient’s rights and privacy in trials (Table 4). In terms of religious barriers, the score is 49.8/100. Only about 10–11% of the respondents cited religious teachings or beliefs, religious duty or spiritual practices, and disapproval from religious leaders and/or members as barriers to their participation in clinical trials.

When comparing between cancer patients and non-cancer patients, both groups showed comparable levels of overall willingness to participate in clinical trials (41.2/100 vs. 39.8/100, p = 0.434); however, cancer patients were slightly more inclined to participate in trials involving novel drugs (31.9/100 vs. 27.4/100, p = 0.021). No significant differences were found in other clinical trial scenarios. Although cancer patients showed marginally higher scores concerning religious barriers (51.4/100 vs. 48.3/100, p = 0.006), there are no significant differences in their scores for knowledge, perceived benefits and risks, or confidence in the conduct of clinical trials (Table 5).

In logistic regression analysis, Model 1 shows that being male [OR 1.75 95%CI (1.11, 2.75)] and having a higher knowledge score [OR 1.01 95%CI (1.01, 1.02)] are significantly associated with the high willingness to participate in clinical trials, whereas unemployment has negative association [OR 0.40 95%CI (0.18, 0.89)], In Model 2, unemployment remained significantly associated with lower willingness to participate [OR 0.37 95%CI (0.15, 0.95)], while having a higher perceived benefit score [OR 1.10 95%CI (1.06, 1.13)], a lower perceived risk score [OR 0.95 95%CI (0.93, 0.96)], and a higher score for confidence in clinical trial conducts [OR 1.03 95%CI (1.00, 1.05)] are the significant factors associated with a high willingness score to participate in clinical trials (Table 6). The univariable analysis results are supplied in the supplementary table (Supplementary materials, Table S3).

Discussion

Overall, our study found a relatively low willingness among patients to participate in clinical trials, with trials involving new drugs received the lowest willingness rating. This reluctance likely stem from concerns about the safety and efficacy of new drugs, as evidenced by respondents’ responses on their perceived benefit and risks of clinical trials in this study. Previous studies showed that perception towards unproven treatment and fear of its side effects were the primary reasons for declining to participate in clinical trial7,8. Interestingly, cancer patients showed greater willingness to participate in trials involving new drugs compare to non-cancer patients, possibly due to their greater need for alternative treatments.

To elucidate the factors influencing willingness to participate in clinical trials, we employed two logistic regression models. Model 1 revealed that gender, employment status, and, clinical trial knowledge were significantly associated with willingness to participate. However, in Model 2, which incorporated additional factors, the associations of gender and knowledge became non-significant, albeit with marginal p-values. Notably, perceptions of benefits and risks, as well as confidence in clinical trials, were the significant factors of willingness to participate in Model 2. This shift suggests that perceptions and confidence might play a more critical role in determining willingness to participate in clinical trials.

Consistent with previous studies, our respondents’ concerns revolved around the safety and inefficacy of the treatment9,10,11. We found that higher perceived benefits and lower perceived risks were associated with high willingness to participate in clinical trials. This underscores the crucial need for effective communication about potential benefits and risks, and addressing patients’ concerns12. Researchers or healthcare providers must provide clear information and education about the clinical trials, offering support and reassurance throughout the study process.

We also need to address the lack of confidence in the clinical trial processes and investigator’s roles among our patients. Research indicates that patients’ distrust towards medical researchers hinders their participation in clinical trials13,14, and misinformation from the internet and social media may further undermine confidence and attitudes towards trials15,16. To address these issues, we recommend improving transparency in research, enhancing communication regarding trial process and results, and increasing the visibility of Malaysia’s clinical trial regulatory framework. This can be achieved by strengthening existing channels, such as promoting the official websites of regulatory bodies, ethics committees, and independent review boards, and by leveraging social media to disseminate accurate and accessible information. Additionally, involving patient advocacy groups and individuals with lived experiences in the planning and governance of clinical trials could further foster trust and transparency17.

Public and patient involvement in clinical study design has been shown to enhance the practicality, sustainability, and transparency of research18. Although this approach is relatively new in Malaysia, incorporating patient voices can make trials more patient-cantered and improve overall trial engagement. For example, patient involvement makes information sheets more patient-friendly and study procedures more acceptable. This collaborative approach has the potential to increase enrolment and retention rates, as well as enhance the applicability of findings to the patient population19.

Demographically, our study revealed significant disparity in the willingness to participate in clinical trials. Female patients showed lower willingness, possibly due to higher risk aversion20,21, which may contribute to their lower participation in a perceived high-risk activity such as clinical trials22. Unemployed individuals also showed a significantly lower willingness to participate in clinical trials. We postulate this could be attributed to their sensitivity to the costs of participating due to poorer income and financial insecurities. However, personal income was not found to be significantly associated with willingness to participate in this study. Interestingly, only 30% of our respondents agreed that monetary compensation as a benefit of participating in a trial, indicating that it is not an important driver for clinical trial participation among our patients. This was in contrast to a study from Indonesia that found increased willingness with higher financial compensation23. Nonetheless, we believe this could also be due to the limited understanding of clinical trials, with respondents potentially unaware of possible monetary compensation for participating in a clinical trial.

Only about 40% of our respondents had heard of clinical trial before the survey, and the majority demonstrated poor knowledge. However, those with better knowledge about clinical trials showed increased willingness to participate, aligning with previous findings8,24. We also observed significant disparities in clinical trial knowledge among patients from different socio-economic backgrounds in the post hoc analyses (Supplementary materials, Table S3). These findings highlight the need for targeted efforts, including public campaigns, community education programs, and other outreach initiatives tailored to diverse communities25,26. Social media can be leveraged as an effective tool for disseminating clinical trial information and boosting recruitment27,28, although caution is warranted regarding privacy and confidentiality concern29.

Even though almost all our respondents reported having a religious affiliation, only a small fraction (10–11%) agreed that their religious beliefs, obligations, peers and leaders affected their decision to participate in clinical trials. This showed that religious practice and the religious community support may not play a significant role in affecting clinical trial participation in our community. This is in contrast with a study by Daverio-Zanetti et al., which found that higher religiosity was associated with a perceived lack of community support for clinical trial participation among Hispanic Americans30. Nevertheless, as we did not assess the religiosity of our patients in the present study and our findings may be specific to the local context in Sarawak, further research is needed.

Our study had several limitations. Firstly, it was a single-centred study conducted at SGH. However, SGH as the main tertiary referral centre in Sarawak region serves a large patient population. For instance, SGH is the only public oncology centre, providing care for the majority of cancer patients in Sarawak. Therefore, our study has a good representation of the patient population in Sarawak. Nevertheless, a larger national study is warranted to investigate clinical trial participation in the national population. Secondly, there was a possibility of sampling bias as we only approached patients who were able to answer the survey at the clinics. Illiterate, low-educated patients might have been underrepresented. Thirdly, the study was conducted in a hospital setting, which might have influenced the responses of the patients. They might feel pressured to respond quickly while waiting for their clinic appointments. However, we addressed this issue by ensuring anonymity in answering the questionnaire and allowing participants to submit their responses at a later time or on their next visit to the hospital. Lastly, the cutoff indicating high willingness to participate was arbitrarily determined. Future prospective studies are needed to validate this cutoff in relation to actual patient participation in clinical trials.

In summary, our study highlighted the challenges in engaging Malaysian patients in clinical trials, particularly in Sarawak, Factors such as poor knowledge, low perceived benefits, high perceived risks, and poor confidence in clinical trial conducts contributed to the overall lack of willingness to participate. Our findings suggest the need for targeted efforts to raise awareness and understanding, provide clear and balanced information on benefits and risks, and enhance the public’s confidence in the clinical trial process and investigator’ roles. The insights from the present study would be useful to understand the drivers and barriers to clinical trial participation, as well as for formulating strategies to promote such participations and patient inclusion in clinical trials in Malaysia.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

6. References

McDonald, A. M. et al. What influences recruitment to randomised controlled trials? A review of trials funded by two UK funding agencies. Trials 7, 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-7-9 (2006).

Treweek, S. et al. Strategies to improve recruitment to randomised controlled trials. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. MR000013 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.MR000013.pub5 (2010).

Phase 1 Realisation Project Report (P1RP). 2016– (2021). https://clinicalresearch.my/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/P1RP-report-REVISED_16-Mar__compressed.pdf (2022).

Voon, P. J. et al. Early phase oncology clinical trials in Malaysia: current status and future perspectives. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajco.13886 (2022).

Khalid, K. F. & Ooi, A. J. A. Malaysia’s Clinical Research Ecosystem, (2017). https://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/view/malaysia-s-clinical-research-ecosystem

Tan, S. H. et al. Development and validation of Join Clinical Trial Questionnaire (JoinCT). Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajco.14034 (2023).

Lim, Y. et al. Korean Cancer Patients’ Awareness of Clinical Trials, Perceptions on the Benefit and Willingness to Participate. Cancer Res. Treat. 49, 1033–1043. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2016.413 (2017).

Ellis, P. M., Butow, P. N., Tattersall, M. H., Dunn, S. M. & Houssami, N. Randomized clinical trials in oncology: understanding and attitudes predict willingness to participate. J. Clin. Oncol. 19, 3554–3561. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2001.19.15.3554 (2001).

Quinn, G. P. et al. Cancer patients’ fears related to clinical trial participation: a qualitative study. J. Cancer Educ. 27, 257–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-012-0310-y (2012).

Manne, S. et al. Attitudinal barriers to participation in oncology clinical trials: factor analysis and correlates of barriers. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl). 24, 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12180 (2015).

Unger, J. M. et al. Patient income level and cancer clinical trial participation. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 536–542. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.45.4553 (2013).

Walsh, E. & Sheridan, A. Factors affecting patient participation in clinical trials in Ireland: A narrative review. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 3, 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2016.01.002 (2016).

Abdelhafiz, A. S. et al. Factors Influencing Participation in COVID-19 Clinical Trials: A Multi-National Study. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 8, 608959. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.608959 (2021).

Braunstein, J. B., Sherber, N. S., Schulman, S. P., Ding, E. L. & Powe, N. R. Race, medical researcher distrust, perceived harm, and willingness to participate in cardiovascular prevention trials. Med. (Baltim). 87, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0b013e3181625d78 (2008).

Borges do Nascimento, I. J. et al. Infodemics and health misinformation: a systematic review of reviews. Bull. World Health Organ. 100, 544–561. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.21.287654 (2022).

Islam, M. S. et al. COVID-19 vaccine rumors and conspiracy theories: The need for cognitive inoculation against misinformation to improve vaccine adherence. PLoS One. 16, e0251605. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251605 (2021).

Faulkner, S. D., Somers, F., Boudes, M., Nafria, B. & Robinson, P. Using Patient Perspectives to Inform Better Clinical Trial Design and Conduct: Current Trends and Future Directions. Pharmaceut Med. 37, 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40290-022-00458-4 (2023).

Skovlund, P. C. et al. The impact of patient involvement in research: a case study of the planning, conduct and dissemination of a clinical, controlled trial. Res. Involv. Engagem. 6, 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-020-00214-5 (2020).

Arumugam, A. et al. Patient and public involvement in research: a review of practical resources for young investigators. BMC Rheumatol. 7, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-023-00327-w (2023).

Harris, C. R. & Jenkins, M. Gender Differences in Risk Assessment: Why do Women Take Fewer Risks than Men? Judgm. Decis. Mak. 1, 48–63. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1930297500000346 (2006).

Pawlowski, B., Atwal, R. & Dunbar, R. I. M. Sex Differences in Everyday Risk-Taking Behavior in Humans. Evolutionary Psychol. 6, 147470490800600104. https://doi.org/10.1177/147470490800600104 (2008).

Ding, E. L., Powe, N. R., Manson, J. E., Sherber, N. S. & Braunstein, J. B. Sex differences in perceived risks, distrust, and willingness to participate in clinical trials: a randomized study of cardiovascular prevention trials. Arch. Intern. Med. 167, 905–912. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.9.905 (2007).

Harapan, H. et al. Willingness to Participate and Associated Factors in a Zika Vaccine Trial in Indonesia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Viruses 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/v10110648 (2018).

Mosconi, P. et al. Knowledge and attitudes towards clinical trials among women with ovarian cancer: results of the ACTO study. J. Ovarian Res. 15 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-022-00970-w (2022).

Heller, C. et al. Strategies addressing barriers to clinical trial enrollment of underrepresented populations: A systematic review. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 39, 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2014.08.004 (2014).

Michaels, M. et al. The Promise of Community-Based Advocacy and Education Efforts for Increasing Cancer Clinical Trials Accrual. J. Cancer Educ. 27, 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-011-0271-6 (2011).

Geist, R. et al. Social Media and Clinical Research in Dermatology. Curr. Dermatology Rep. 10, 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13671-021-00350-5 (2021).

Sedrak, M. S., Cohen, R. B., Merchant, R. M. & Schapira, M. M. Cancer Communication in the Social Media Age. JAMA Oncol. 2 https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5475 (2016).

Thompson, M. A. & O’Regan, R. M. Social media and clinical trials: The pros and cons gain context when the patient is at the center. Cancer 124, 4618–4621. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31747 (2018).

Daverio-Zanetti, S. et al. Is Religiosity Related to Attitudes Toward Clinical Trials Participation? J. Cancer Educ. 30, 220–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-014-0696-9 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the Director General of Health of Malaysia for the permission to publish this paper. We also thank Li Fang Lim, Hanisah Hossain and Roisin Lim for their efforts in the questionnaire distribution and data collection.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TLK, SHT, SSNT, WHL, MAB, and PJV developed the questionnaire and designed the study protocol. TLK and SHT collected the data. TLK, SHT, and MAB analysed the data. TLK conceived the manuscript. All authors interpreted the findings and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicting Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

King, T.L., Tan, S.H., Tan, S.S.N. et al. Survey of willingness to participate in clinical trials and influencing factors among cancer and non-cancer patients. Sci Rep 15, 1626 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83626-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-83626-7