Abstract

Learning engagement has attracted increasing interest in recent years, with teacher support, academic self-efficacy, psychological resilience, and positive academic emotion identified as key factors. However, the moderated mediating mechanisms between teacher support and learning engagement remain unexplored. This study aimed to investigate the roles of academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience as mediators, and positive academic emotion as a moderator, in the relationship between teacher support and secondary school students’ learning engagement, from the perspective of the Self-determination Theory and Emotion Regulation Theory. The study involved 665 participants (Mage = 14 years, SD = 0.790) randomly selected from four public secondary schools in Eastern China. Data were analyzed with the structural equation model (SEM) in SPSS 24.0, AMOS 24.0, and PROCESS 3.5. Results indicated that teacher support was directly and positively associated with learning engagement. The results also indicated that teacher support was indirectly and positively related to learning engagement through academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience. Additionally, the moderation role of positive academic emotion manifests in the association between academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience. These findings illuminate the complex dynamics underlying learning engagement and provide valuable insights for educators and researchers in promoting optimal learning experiences for secondary school students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Learning engagement has received significant attention in recent years due to its impact on a student’s academic achievement and overall success in school1. High levels of engagement are associated with active participation in classroom discussions, strong interest and motivation to learn, and exceptional academic achievements2. Conversely, low levels of engagement are linked to reduced academic expectations, increased likelihood of experiencing negative emotions such as anxiety and boredom, disruptive behaviors, and even school dropout3. Therefore, enhancing students’ learning engagement is a critical issue that demands attention in current education reform.

Learning engagement can be defined as the extent to which students actively participate in activities related to learning, encompassing behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement4,5. Behavioral engagement refers to students’ active involvement in learning activities, displaying high levels of focus, involvement, and adherence to school rules4. Emotional engagement refers to students’ positive emotional responses to learning, whereas cognitive engagement refers to a self-regulated approach to learning, involving the use of metacognitive strategies to monitor and regulate one’s own learning process6.

Teacher support has been consistently identified as a significant facilitator of students’ learning engagement, supported by a substantial body of research7,8,9. Teacher support refers to the attitudes and behaviors exhibited by teachers towards students’ academic lives, encompassing two dimensions: emotional support and academic support10. Academic support covers students’ perceptions of their teachers’ commitment to their learning and their readiness to offer tangible assistance when needed, while emotional support involves teachers’ care, trust, encouragement, respect, and equality towards their students11. The two concepts, academic support and emotional support, are closely interrelated and can be considered as a unified measure12. Teacher support plays a crucial role in fostering positive teacher-student relationships, which are fundamental for students to develop their social interactions and academic capacities within the classroom context13. This, in turn, motivates students to actively participate in classroom activities and promotes their concentration on academic tasks, ultimately enhancing students’ engagement14.

Academic self-efficacy, psychological resilience, and positive academic emotion are three psychological constructs extensively studied in connection with learning engagement15,16,17,18,19,20. They have been found to exhibit a positive correlation with learning engagement. For example, Shao and Kang suggested that students with a high level of academic self-efficacy possess a strong belief in their ability to do well in learning, which motivates them to establish ambitious goals, persist in the face of challenges, and invest effort in their academic pursuits, ultimately leading to the increased levels of engagement in the learning process21. Romano et al. proposed that psychological resilience positively influences learning engagement, as individuals with higher levels of psychological resilience are better equipped to adapt to challenges and difficulties encountered during the learning process, leading to increased engagement and improved learning outcomes22. Sadoughi and Hejazi indicated that positive academic emotions have a positive impact on students’ learning engagement by enhance students’ interest, attention, and focus on the learning tasks, resulting in increased effort, persistence, and active involvement in the learning process8. The findings underscore the significance of incorporating academic self-efficacy, psychological resilience, and positive academic emotion into the understanding of learning engagement.

Despite scholars recognizing the influence of these factors on learning engagement, there exists a research gap regarding the specific mechanisms through which teacher support is connected to learning engagement through the mediating roles of academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience, along with the moderating role of positive academic emotion. To address this research gap, this study aims to investigate the interactive effects of teacher support, academic self-efficacy, psychological resilience, positive academic emotion on learning engagement, thereby providing a holistic understanding of the relationship between these factors. Furthermore, this study endeavors to explore the chain mediating roles of academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience, as well as the moderating role of positive academic emotion, in the association between teacher support and learning engagement among secondary school students. This study is significant as it addresses a gap in the existing literature and provides insights and guidance for educators and policymakers seeking to enhance students’ learning engagement.

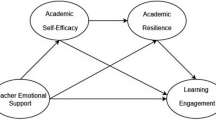

The Self-determination Theory (SDT) and Emotion Regulation Theory (ERT) provide a conceptual framework guiding the construction of a moderated mediating model in this study. SDT, proposed by American psychologists Deci and Ryan, elucidates the motivational processes underpinning self-determined behaviors in humans23. According to SDT, human behaviors are motivated by the satisfaction of psychological needs, including autonomy, competence, and relatedness, which are influenced by social partners such as parents, teachers, and peers23. Empirical evidence suggests that teacher support can enhance students’ sense of choice and control over their learning by providing opportunities for students to align their inner resources with their classroom activity24, contributing to the satisfaction of autonomy needs. Additionally, support from teachers, such as clarifying learning objectives and promoting deep learning25, can facilitate students’ achievement of competence needs. Furthermore, teacher support can foster a sense of belonging and meaningful connection among students26, promoting the fulfillment of relatedness needs. Within the SDT framework, teacher support plays a crucial role in promoting students’ psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, thereby enhancing their engagement in the learning process27. When students’ psychological needs are met through teacher support, their motivation and autonomous learning are enhanced, thereby improving their academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience28. This, in turn, influences their learning engagement, making students more likely to engage in learning activities21. Furthermore, ERT, proposed by Gross, elucidates the moderating role of positive academic emotions. The theory emphasizes how emotions impact individual psychology and behavior29, as well as how individuals manage and modulate their emotional experiences through various strategies30. Within this theoretical framework, positive academic emotions act as a crucial emotional regulatory resource, fostering a positive evaluation of one’s abilities, enhancing academic self-efficacy, and aiding individuals in coping with challenges and difficulties31, thereby improving psychological resilience. Specifically, when students experience positive academic emotions, they are more likely to hold positive beliefs about their academic capabilities, which in turn strengthens their psychological resilience and equips them to better handle academic challenges. Thus, positive academic emotions are posited to moderate the relationship between academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience. By employing emotion regulation strategies, students can more effectively manage their emotional responses, which may lead to enhanced academic engagement. The theoretical model is presented in Fig. 1.

Teacher support and learning engagement

Teacher support positively influences on students’ engagement in learning7. Hagenauer et al. suggested that students are more likely to proactively involve themselves in learning activities when they receive support from their teachers32. Wong et al. demonstrated that teacher support enhances students’ interest, pleasure, investment in the learning process33. Emotional support from teachers has been shown to foster positive interest and motivation, leading to increased effort and dedication to studies11. Similarly, academic support from teachers influences students’ engagement by helping them clarify learning objectives, adjust their learning plans, and promote deep learning25. These findings highlight the crucial role of teacher support in fostering students’ learning engagement. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Teacher support is positively correlated with secondary school students’ learning engagement.

The mediating role of academic self-efficacy

Bandura defines self-efficacy as an individual’s judgement of their overall ability to achieve a goal when initiating an educational program34. In the academic context, self-efficacy is often referred to as academic self-efficacy35.

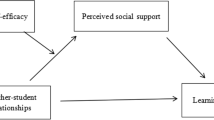

Teacher support significantly impacts students’ academic self-efficacy14. Greater perceived support from teachers is associated with improved attitudes towards learning and stronger belief students’ abilities11. Emotional support from teachers has been linked to a greater sense of academic self-efficacy by reducing psychological stress and boosting students’ confidence in overcoming difficulties36. Additionally, students who receive more academic support from teachers tend to achieve higher grades, leading to a higher sense of academic self-efficacy37. In conclusion, teacher support is positively correlated with secondary school students’ academic self-efficacy.

Academic self-efficacy has a significant impact on students’ engagement in learning19. Research has indicated that students with higher academic self-efficacy are more engaged in the classroom, while those with lower academic self-efficacy tend to participate less and show more indifference in the classroom20. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that higher academic self-efficacy fosters confidence, persistence, and positive attitudes, enhancing students’ engagement, while lower academic self-efficacy can lead to reduced motivation and participation in classroom activities. Additionally, Syed Sahil and Awang Hashim found that teacher support is significantly related to learning engagement through academic self-efficacy among 450 adolescents from 11 secondary schools in Malaysia38. Although this study was conducted over a decade ago with Malaysian secondary school students, and may not be directly applicable to the current population of Chinese participants, it still offers some valuable insights. These findings collectively suggest that teacher support may influence students’ engagement in learning through the mediation effect of academic self-efficacy. Therefore, the following hypothesis is formulated:

The mediating role of psychological resilience

Psychological resilience refers to an individual’s ability to respond and adapt positively to major setbacks, adversity, threats, and other challenges39. Teacher support has been found to play a significant role in shaping psychological resilience40. Liao et al. argue that teachers’ emotionally supportive behaviors, such as caring and encouragement, can help students cope with frustrations positively and increase their psychological resilience41. Similarly, Permatasari et al. emphasize that students who perceive more teacher support tend to become more psychologically resilient42. Therefore, existing evidence suggests that teacher support can strengthen students’ psychological resilience.

Psychological resilience has been found to influence students’ learning engagement17. Romano et al. propose that psychological resilience is a positive predictive factor for learning engagement22. Furthermore, Furrer et al. qualitatively explored this relationship among 11-14-year-olds, revealing that increased teacher support is linked to heightened psychological resilience, subsequently enhancing learning engagement15. Building on this qualitative research, the current study hypothesizes not only a significant positive correlation between psychological resilience and learning engagement, but also that psychological resilience may mediate the relationship between teacher support and learning engagement among secondary school students in a quantitative research setting.

Academic self-efficacy can help students regain self-confidence and adapt positively to adversity, further fostering their psychological resilience. It is believed that academic self-efficacy contributes to psychological resilience and learning engagement43. Specifically, students with a strong sense of self-efficacy are better able to accomplish learning tasks and achieve their desired goals through their resilient qualities. Grounded on the above empirical studies, it is believed that teacher support may be positively associated with secondary school students’ learning engagement via academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience. Accordingly, the hypotheses are developed as follows:

The moderating role of positive academic emotion

Academic emotion encompasses the full range of emotional responses that students experience in connection with their academic endeavors, including feelings such as enjoyment, relief, anxiety, and depression44. Academic emotion is typically categorized into four dimensions: positive high arousal, positive low arousal, negative high arousal, negative low arousal45. Positive academic emotion specifically refers to the favorable emotional experiences that students may encounter within the academic context46. In this survey, we have specifically chosen the subscales related to positive dimensions to assess students’ positive academic emotions in line with the research requirements.

According to the Emotion Regulation Theory, individuals with high positive academic emotions tend to employ positive emotion regulation strategies to cope with learning tasks, leading to higher confidence in learning and higher academic self-efficacy47, which in turn fosters stronger psychological resilience43. Conversely, individuals with low positive academic emotions tend to use negative emotion regulation strategies, resulting in decreased confidence and lower psychological resilience48. Zuo et al. found a significant association between positive academic emotions and academic self-efficacy, indicating that individuals with high positive academic emotions are more likely to maintain an optimistic attitude and actively cope with challenges, leading to higher academic self-efficacy49. Additionally, individuals with high positive academic emotions exhibit greater resilience in facing learning difficulties and completing tasks50,51. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H5: Positive academic emotion moderates the association between academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience in such a way that the association will be stronger when positive academic emotion is higher.

Materials and methods

Sampling and procedure

This study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was granted approval by the Ethics Committee at Weifang Engineering Vocational College (approval no: 2024-0086). A stratified random sampling method was employed to select a diverse sample of 750 students, aged 13 to 15 years, from four public secondary schools in Eastern China for participation in a survey conducted in April 2024. The selected schools varied in terms of student demographics, academic performance, and socio-economic backgrounds, ensuring a representative cross-section of the regional student population. Before the survey, the informed consent was obtained from the principals, the students, and their parents respectively. During the survey, the protection of personal privacy was ensured, and the questionnaires were distributed and explained to the participants. After the questionnaires were completed anonymously and collected on the spot. The data from the questionnaires were then sorted and analyzed. Ultimately, 665 valid samples with a response rate of 88.67% were obtained for analysis.

Research instruments

Teacher support scale

Teacher support was measured by the Teacher Support Scale developed by Johnson et al.52, adapted by Patrick et al.10. This scale consists of 8 items, categorized into two dimensions: emotional support (e.g., “My teacher really understands how I feel about things.”) and academic support (e.g., “My teacher wants me to do my best in school.”). Responses were recorded using a 5-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 1(almost never) to 5(often), where higher average scores indicate greater levels of teacher support. The reliability and validity of this scale have been confirmed in Liu ’s empirical research conducted among 869 basic education students in China14.

Academic self-efficacy scale

Academic self-efficacy was assessed using the efficacy subscale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey (MBI-SS)53. This unidimensional scale comprises 6 items (e.g., “I feel stimulated when I achieve my study goals.”). Participants rated all items on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (always), with higher average scores indicating higher levels of academic self-efficacy. The reliability and validity of this scale have been confirmed in Liu et al.’s empirical research on 1487 Chinese students aged 11 to 17 years54.

Psychological resilience scale

Psychological resilience was evaluated using the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale, developed by Campbell-Sills55 based on the scale created by Connor and Davidson56. This scale comprises 10 items with a unidimensional structure (e.g., “I can achieve goals despite obstacles.”). Participants rated each item on a five-point scale ranging from 0 (not true at all) to 4 (true nearly all the time). Average scores are computed, with higher scores indicating greater psychological resilience. The scale has exhibited robust reliability and validity among adolescents, as evidenced by She et al.’s empirical study involving 24,499 secondary school students in Hong Kong, China57.

Positive academic emotion scale

Positive academic emotions were assessed using the positive emotion subscale of the Academic Emotion Scale, a Chinese version developed by Dong and Yu44. Originally, the positive emotion scale included two subscales: positive-high arousal emotions (e.g. pride, enjoyment, hope), positive-low arousal emotions (e.g. contentment, calmness, relief). For the purpose of this study, we selected enjoyment and relief to assess students’ positive academic emotions. Enjoyment was measured by seven items (e.g. “I feel happy that I can get al.l the questions right.”), and relief was measured by five items (e.g. “I can easily complete the learning tasks.”). Responses were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree), with higher average scores indicating greater levels of positive academic emotions. The reliability and validity of the 12-item scale selected for this study were confirmed in Liu’s empirical research conducted among 869 basic education students in China14.

Learning engagement scale

Learning engagement was measured using the Learning Engagement Scale revised by Skinner et al.58. This scale consists of 10 items, with 5 items assessing behavioral engagement (e.g., “When I’m in class, I listen very carefully”) and 5 items assessing emotional engagement (e.g., “I enjoy learning new things in class.”). Responses were rated on a 5-point scale, with 1 indicating “completely disagree” and 5 indicating “completely agree”, where higher average scores indicate greater levels of learning engagement. The scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity in Wu and Sun’s research on 4226 students, including primary school students, middle school students, and college students59.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 24.0, AMOS 24.0, and PROCESS 3.5. First, the Harman single-factor test was conducted to assess common method bias. Second, descriptive analysis was performed to examine sample characteristics. Third, structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis was carried out to investigate the model, including the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to evaluate the validity and reliability of the measurement model, and the goodness-of-fit index analysis to assess the structural model. Fourth, the significance of the mediating effects was determined using the bootstrapping approach with 5,000 bootstrap samples. Finally, a multiple regression analysis was conducted to test the moderating role of positive academic emotion.

Results

Common method variance

Harman’s one-factor test was conducted to examine common method variance (CMV)60. This test involved performing an exploratory factor analysis on all items from the five scales, using an unrotated principal component analysis method in SPSS 24.0. The results revealed that 6 factors had eigenvalues greater than 1, explaining 74.361% of the total variance. Additionally, the first extracted factor explained only 25.832% of the total variable, falling below the critical criterion of 40%61, indicating that there was no serious common method variance.

Sample characteristics

The sample consisted of 665 participants with an average age of 14 years (SD = 0.790, range = 13–15 years). The gender distribution was nearly equal, with 348 males (52.3%) and 317 females (47.7%). Participants were spread across different grades, with 206 (31.0%) in 7th grade, 251(37.7%) in 8th grade, and 208 (31.3%) in 9th grade. Participants from only-child families accounted for a smaller group at 15.9% (106 participants). In terms of the median monthly household income of the students, the percentages were as follows: less than 3000 Yuan (16.7%), 3000–5000 Yuan (43.5%), 5000–10,000 Yuan (29.0%), and 10,000 Yuan and more (10.8%).

Measurement model

The measurement model was evaluated for reliability and validity. Reliability, assessed using Cronbach’s α, demonstrated high values from 0.80 to 0.90, indicating strong reliability62. Convergent validity was assessed through standardized factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE), all of which exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.5, indicating satisfactory convergent validity63. Discriminant validity was assessed by comparing the square root of the AVE with the correlation coefficient between constructs, with the square root of AVE exceeding the correlation coefficient, indicating high discriminant validity64,65.

As presented in Table 1, the value of Cronbach’s α ranged from 0.886 to 0.981, indicating high reliability. The standardized factor loadings covered a range between 0.613 and 0.946 (p < .001), while the values of CR and AVE ranged from 0.892 to 0.981 and from 0.553 to 0.815 respectively, indicating sound convergent validity. In Table 2, the square root of AVE for each construct was greater than the correlation coefficient with any other construct, indicating acceptable levels of discriminant validity.

Structural model

The structural model was evaluated using goodness-of-fit indices in Amos 24.0, encompassing Chi Square/ DF (X2/df), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). The suggested values for these indices are as follows: X2/df should be between 1 and 3, IFI, CFI, TLI, GFI, and AGFI should be greater than 0.9, and RMSEA should be less than 0.0866. In the study, the value of X2/df was 1.159 (X2 = 1134.39, df = 979), and the values of IFI, CFI, TLI, GFI, AGFI, SRMR, and RMSEA met or exceeded the suggested standards, indicating that the structural model was appropriate for the data.

Analyses of the mediating effects

The study examined the mediating effects of academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience through bootstrap analysis67. A bias-corrected 95% confidence interval was employed, with a non-zero interval indicating that the mediation effect is statistically significant. In AMOS24.0, learning engagement was analyzed as the dependent variable, teacher support as the independent variable, academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience as the mediating variables, with a resampling size of 5000.

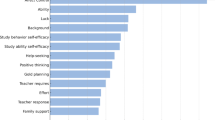

As indicated in Table 3, the direct effect of teacher support on learning engagement was significant, with a value of 0.400 (95% bias-corrected CI [0.291, 0.511], P = .003), providing support for H1. The total indirect effect of teacher support on learning engagement was significant with a value of 0.102 (95% bias-corrected CI [0.064, 0.151], P = .001). Specifically, the pathway of teacher support→ academic self-efficacy→ learning engagement had a mediation effect of 0.056 (95% bias-corrected CI [0.033, 0.092], P = .001), the pathway of teacher support→ psychological resilience→ learning engagement had a mediation effect of 0.034 (95% bias-corrected CI [0.014, 0.066], P = .002), and the pathway of teacher support → academic self-efficacy → psychological resilience →learning engagement had a mediation effect of 0.011 (95% bias-corrected CI [0.004, 0.026], P = .001). These results confirm that academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience played a partial mediating role in the relationship between teacher support and learning engagement, thus confirming H2, H3, and H4.

In addition, the effect percentage of teacher support on learning engagement was examined. As indicated in Table 3, the direct effect of teacher support on learning engagement accounted for 79.8%, while the indirect effect of teacher support on learning engagement accounted for 20.2%, smaller than the direct effect. Among the three significant indirect mediators, the indirect effect of academic self-efficacy is the greatest, accounting for 55.1% of the total indirect effect, while the combined indirect effect of academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience is the smallest, representing 11.1% of the total indirect effect.

Analyses of the moderating effect

Model 91 in PROCESS68 was used to examine the moderating effect of positive academic emotion on the mediation model. All the variables except for gender were standardized before performing the moderated mediation analysis69. R-squared (R2) is a widely used measure of accuracy in linear models and ANOVA. It represents the percentage of variance in the dependent variable explained by the independent variables70. As shown in Table 4, before adding the interaction effect, the model had an R2 value of 0.049. However, with the inclusion of the interaction effect, the R2 value increased to 0.209. This suggests that the interaction effect significantly contributes to explaining the dependent variable. The interactivity of academic self-efficacy and positive academic emotion had a significant positive moderating effect on psychological resilience (coeff = 0.119, t = 6.097, p = .000), indicating academic emotion moderated the intermediate part of the chain mediator. In other words, positive academic emotion played a moderating role in the effect of academic self-efficacy on psychological resilience.

To visually demonstrate the moderating effect of positive academic emotions, a simple slope test was conducted. As shown in Fig. 2, in the low positive academic emotion group (M-1SD), the positive correlation between academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience is statistically significant (simple slope = 0.097, t = 3.159, p < .001). In contrast, in the high positive academic emotion group (M + 1SD), the positive correlation between academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience is strengthened and statistically significant (simple slope = 0.356, t = 10.247, p < .001). Therefore, H5 was further validated.

.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the moderated mediating mechanisms between teacher support and learning engagement, specifically investigating the indirect effects of teacher support on learning engagement through academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience, moderated by positive academic emotion. The findings are presented as follows.

The results of the study indicated that teacher support was directly and positively related to secondary school students’ learning engagement, which not only confirms the research result of Jin and Wang7 and Sadoughi and Hejazi8. These studies underscore the significance of teacher support in fostering learning engagement. From the perspective of Self-Determination Theory, we can delve deeper into this relationship by examining how teacher support satisfies the three fundamental psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. As Sun notes, teacher support is instrumental in fulfilling these needs, which SDT posits as crucial for enhancing intrinsic motivation71. When teachers offer academic and emotional support, they empower students’ autonomy by allowing them to make voluntary learning choices, enhance their sense of competence through challenges and constructive feedback, and fulfill their need for relatedness through care and encouragement, making students feel part of a learning community. Moreover, the study suggests that secondary school students with more support and encouragement from their teachers become less distracted and more actively engaged in the learning process14. This study further demonstrates that teacher support is a predictive factor of learning engagement.

The results of the study revealed academic self-efficacy plays a significant partial mediating role in the relationship between teacher support and secondary school students’ learning engagement. This finding is consistent with previous research indicating a positive relationship between teacher support and academic self-efficacy14,36, as well as a positive association between academic self-efficacy and learning engagement19. These findings support the notion that when students receive high levels of support from their teachers, it enhances their belief in their academic abilities, which in turn leads to increased engagement in their learning activities38. Besides, the finding aligns with the principles of Self-Determination Theory. teacher support is a key factor in fulfilling three needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness, as it fosters a learning environment where students feel supported, capable, and connected to their teachers72. When teachers provide support, they enhance students’ sense of autonomy by aligning their inner resources with classroom activities, boost their competence through encouragement and feedback, and strengthen their relatedness by fostering a sense of belonging24,25,26. These supportive behaviors are crucial for building students’ academic self-efficacy, which is the belief in one’s ability to succeed in academic tasks. As academic self-efficacy increases, so does students’ engagement in learning activities, as they are more likely to persevere in the face of challenges and invest more effort into their learning. The finding provides more evidence of the role of academic self-efficacy in the relationship between teacher support and learning engagement.

The results of the study demonstrated that psychological resilience is another significant partial mediating role between teacher support and secondary school students’ learning engagement. This finding aligns with Furrer et al.’s perspective, emphasizing the crucial role of psychological resilience in the association between teacher support and learning engagement15. Students with higher psychological resilience are more likely to exhibit flexibility and perseverance when faced with challenges and display self-assurance in resolving difficulties, which are vital in promoting active engagement in learning21. Furthermore, this result is consistent with Fang et al.’s study which indicated that students’ perceived teacher support enhances their ability to meet their fundamental psychological needs, stimulates their autonomous motivation, and improves their psychological resilience, all of which ultimately promote learning engagement73. In summary, this finding provides further evidence of the significant role of psychological resilience in mediating the relationship between teacher support and learning engagement.

The results of the study further showed that both academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience played a chain mediating role between teacher support and secondary school students’ learning engagement, representing one of the most remarkable conclusions drawn from the investigation. The finding is well-supported by the self-determination theory (SDT), as articulated by Deci and Ryan23, which posits that social facilitators, such as teacher support, are instrumental in enhancing internal traits like academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience, thereby fostering a greater propensity for students to engage in learning activities. This finding advances the previous research by shedding light on how teacher support can increase students’ learning engagement7,8,11. While some studies have emphasized the mediating role of academic self-efficacy, and others have focused on psychological resilience, this study bridges the gap by integrating both areas of research and uncovering the latent link between academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience. Additionally, this study identified the proportion of the chain mediating effect of academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience, which, although accounting for only 11.1% of the indirect effect, holds significance in comprehending the overall impact of teacher support on students’ learning engagement.

The results of the study revealed that positive academic emotion moderated the relationship between academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience. This finding can be further illuminated by Emotion Regulation Theory (ERT), which suggests that the ability to regulate emotions is crucial for maintaining a positive emotional state that facilitates goal-directed behavior and stress management30. For students with low levels of positive academic emotion, the relationship between academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience may be more fragile. They might lack the emotional resources necessary to employ effective emotion regulation strategies, which could limit their ability to transform self-efficacy into resilience in the face of academic stressors. This is consistent with findings by Xu, who noted that students with higher levels of positive academic emotions are better equipped to withstand stress and maintain commitment to their goals74. The finding may also help to reconcile inconsistent results regarding the relationship between academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience, as noted by Amitay and Gumpel75 and Mao et al.50. The role of positive academic emotions as a moderator suggests that the strength of the relationship between self-efficacy and resilience is not uniform across all students but is contingent upon their emotional states. This emotional state, as per ERT, is a critical factor in how individuals perceive and respond to challenges, which can either bolster or undermine their resilience. Therefore, positive academic emotion can be viewed as a promising indicator for discriminating whether students with high academic self-efficacy achieve high psychological resilience.

Limitations and future research directions

Limitations should be acknowledged in the study. Firstly, the cross-sectional design utilized precludes making causal inferences about the relationships between variables. Future studies should employ longitudinal or experimental designs to confirm the causal hypotheses. Secondly, the reliance on self-reported measures from secondary school students introduces the possibility of biases, such as social desirability. Collecting data from multiple sources, such as teachers or peers, could help validate the findings. Thirdly, the sample in this study was limited to four secondary schools in eastern China, which, to a certain extent, may restrict the generalizability of the results. Future studies should aim to include more diverse samples to enhance the external validity.

Implications

The findings of this study carry significant implications for educators and researchers. First, the study highlights the crucial role of teacher support in enhancing secondary school students’ learning engagement. Equipping teachers with adequate training to actively provide support and improve students’ learning engagement is crucial. Additionally, implementing supportive behaviors, such as sincere communication and effective learning strategies is vital to meeting students’ basic psychological need and ultimately enhances their engagement in their studies. Second, the study underscores the importance of academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience in mediating the relationship between teacher support and secondary school students’ learning engagement. Effective interventions to improve students’ academic self-efficacy and psychological resilience are crucial for enhancing their learning engagement. For instance, teachers can encourage students to reflect on their academic progress to enhance their sense of autonomy and their confidence in their ability to succeed. Moreover, purposeful activities such as showing motivational movies and conducting life education can help students cope with setbacks and develop psychological resilience76. Third, the study emphasizes the moderating role of positive academic emotion in the indirect relationship between teacher support and secondary school students’ learning engagement. Efforts should be made to enhance students’ positive academic emotions, with teachers leading by example and influencing students with their positive emotional state. Additionally, strengthening communication with students can help them feel cared for and supported, alleviating their worries and problems.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Dunn, T. J. & Kennedy, M. Technology enhanced learning in higher education; motivations, engagement and academic achievement. Comput. Educ. 137, 104–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.04.004 (2019).

Shao, Y., Kang, S., Lu, Q., Zhang, C. & Li, R. How peer relationships affect academic achievement among junior high school students: the chain mediating roles of learning motivation and learning engagement. BMC Psychol. 12 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01780-z (2024).

Kim, H. J., Hong, A. J. & Song, H. D. The roles of academic engagement and digital readiness in students’ achievements in university e-learning environments. Int. J. Educational Technol. High. Educ. 16 (1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0152-3 (2019).

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C. & Paris, A. H. School engagement: potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 74, 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059 (2004).

Reeve, J. & Tseng, C. M. Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 36 (4), 257–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.05.002 (2011).

Wang, M. T. & Eccles, J. S. Adolescent behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement trajectories in school and their differential relations to educational success. J. Res. Adolescence. 22 (1), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00753.x (2012).

Jin, G. & Wang, Y. The influence of gratitude on learning engagement among adolescents: the multiple mediating effects of teachers’ emotional support and students’ basic psychological needs. J. Adolesc. 77, 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.09.006 (2019).

Sadoughi, M. & Hejazi, S. Y. Teacher support and academic engagement among EFL learners: the role of positive academic emotions. Stud. Educational Evaluation. 70, Article 101060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.101060 (2021).

Xerri, M. J., Radford, K. & Shacklock, K. Student engagement in academic activities: a social support perspective. High. Educ. 75, 589–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0162-9 (2018).

Patrick, H., Ryan, A. M. & Kaplan, A. Early adolescents’ perceptions of the classroom social environment, motivational beliefs, and engagement. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.83 (2007).

Liu, Q., Du, X. & Lu, H. Teacher support and learning engagement of EFL learners: the mediating role of self-efficacy and achievement goal orientation. Curr. Psychol. 42, 2619–2635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-04043-5 (2023).

Wentzel, K. R. Student motivation in middle school: the role of perceived pedagogical caring. J. Educ. Psychol. 89 (3), 411. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.89.3.411 (1997).

Bedeck, K. Children’s Bullying and Victimization on School Engagement: The Influence of Teacher Support [Unpublished undergraduate thesis]. King’s University College. (2015). https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/psychK_uht/27

Liu, R. D. et al. Teacher support and math engagement: roles of academic self-efficacy and positive emotions. Educational Psychol. 38 (1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2017.1359238 (2018).

Furrer, C. J., Skinner, E. A. & Pitzer, J. R. The influence of teacher and peer relationships on students’ classroom engagement and everyday motivational resilience. Teachers Coll. Record. 116 (13), 101–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811411601319 (2014).

Li, J. & Lerner, R. M. Academic-related emotions and self-regulated learning in middle school: a structural equation model. Educational Psychol. Rev. 25 (3), 325–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-013-9231-0 (2013).

Simões, C. et al. Assessing the impact of the European resilience curriculum in preschool, early and late primary school children. School Psychol. Int. 42, 539–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/01430343211025075 (2021).

Tan, Y. A study on the relationship between middle school students’ perception of teacher support, academic emotions, learning engagement and countermeasures. (Unpublished master’s thesis of China). Yunnan Normal University (2021).

Zhao, Y., Zheng, Z., Pan, C. & Zhou, L. Self-esteem and academic engagement among adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 12, 690828. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.690828 (2021).

Zhen, R. et al. The mediating roles of academic self-efficacy and academic emotions in the relation between basic psychological needs satisfaction and learning engagement among Chinese adolescent students. Learn. Individual Differences. 54, 210–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.01.017 (2017).

Shao, Y. & Kang, S. The association between peer relationship and learning engagement among adolescents: the chain mediating roles of self-efficacy and academic resilience. Front. Psychol. 13, Article 938756. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.938756 (2022).

Romano, L., Angelini, G., Consiglio, P. & Fiorilli, C. Academic resilience and engagement in high school students: the mediating role of perceived teacher emotional support. Eur. J. Invest. Health Psychol. Educ. 11, 334–344. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11020025 (2021).

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. Intrinsic Motivation and self-determination in Human Behavior (Springer Science + Business Media, 1985).

Reeve, J. & Jang, H. What teachers say and do to support students’ autonomy during a learning activity. J. Educ. Psychol. 98 (1), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.209 (2006).

Zhao, W., Song, Y., Zhao, Q. & Zhang, R. The effect of teacher support on primary school students’ reading engagement: the mediating role of reading interest and Chinese academic self-concept. Educational Psychol. 39 (2), 236–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1497146 (2018).

Osterman, K. F. et al. Teacher practice and students’ sense of belonging. In T. Lovat (eds.), In Second International Research Handbook on Values Education and Student Wellbeing (pp. 971–993). Springer International Publishing. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-24420-9_54

Reeve, J. A self-determination theory perspective on student engagement. In Christenson, S., Reschly, A., Wylie, C. (eds.), In Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 149–172). Springer US. (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_7

Carmona-Halty, M., Schaufeli, W. B. & Salanova, M. Good relationships, good performance: the mediating role of psychological capital–a three-wave study among students. Front. Psychol. 10, 306. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00306 (2019).

Gross, J. J. The emerging field of emotion regulation: an integrative review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2 (3), 271–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271 (1998).

Gross, J. J. Emotion regulation: conceptual and empirical foundations. In (ed Gross, J. J.) Handbook of Emotion Regulation (2nd ed., 3–20). The Guilford Press (2014).

Pillay, D., Nel, P. & Van Zyl, E. Positive affect and resilience: exploring the role of self-efficacy and self-regulation. A serial mediation model. SA J. Industrial Psychol. 48 (1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v48i0.1913 (2022).

Hagenauer, G., Hascher, T. & Volet, S. E. Teacher emotions in the classroom: associations with students’ engagement, classroom discipline and the interpersonal teacher-student relationship. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 30, 385–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-015-0250-0 (2015).

Wong, T. K., Tao, X. & Konishi, C. Teacher support in learning: Instrumental and appraisal support in relation to math achievement. Issues Educational Res. 28 (1), 202–219. https://doi.org/10.3316/ielapa.437960747459453 (2018).

Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84 (2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191 (1997).

Honicke, T. & Broadbent, J. The influence of academic self-efficacy on academic performance: a systematic review. Educational Res. Rev. 17, 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.11.002 (2016).

Yang, Y., Li, G., Su, Z. & Yuan, Y. Teacher’s emotional support and math performance: the chain mediating effect of academic self-efficacy and math behavioral engagement. Front. Psychol. 12, Article 651608. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.651608 (2021).

Cheng, K. & Tsai, C. An investigation of Taiwan University students’ perceptions of online academic help seeking, and their web-based learning self-efficacy. Internet High. Educ. 14 (3), 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.04.002 (2011).

Syed Sahil, S. A. & Awang Hashim, R. The roles of social support in promoting adolescents’ classroom cognitive engagement through academic self-efficacy. Malaysian J. Learn. Instruction. 8, 49–69 (2011). https://e-journal.uum.edu.my/index.php/mjli/article/view/7626

Fletcher, D. & Sarkar, M. Psychological resilience. Eur. Psychol. 18 (1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000124 (2013).

Liebenberg, L. et al. Bolstering resilience through teacher-student interaction: lessons for school psychologists. School Psychol. Int. 37 (2), 140–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034315614689 (2016).

Liao, Y., Ye, B. & Li, A. The effects of teachers’ caring behavior on the social adjustment of ethnic minority pre-chinese students in Han Area (published manuscript of China). Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 27 (01), 124–128 (2019).

Permatasari, N., Ashari, R., Ismail, N. & F., & Contribution of perceived social support (peer, family, and teacher) to academic resilience during COVID-19. Gold. Ratio Social Sci. Educ. 1 (1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.52970/grsse.v1i1.94 (2021).

Cassidy, S. Resilience building in students: the role of academic self-efficacy. Front. Psychol. 6, Article1781. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01781 (2015).

Dong, Y. & Yu, G. Development and application of the adolescent academic emotion questionnaire (published manuscript of China). J. Psychol. 39 (5), 852–860 (2007).

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W. & Perry, R. P. Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: a program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educational Psychol. 37 (2), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3702_4 (2002).

Villavicencio, F. T. & Bernardo, A. B. Positive academic emotions moderate the relationship between self-regulation and academic achievement. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 83 (2), 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2012.02064.x (2013).

Boekaerts, M. & Pekrun, R. Emotions and emotion regulation in academic settings. In (eds Corno, L. & Anderman, E. M.) In Handbook of Educational Psychology (90–104). Routledge (2015).

Li, D. The mediating role of adolescent emotional regulation self-efficacy between family harmony and psychological resilience (Unpublished master’s thesis of China). Tianjin University (2017).

Zuo, C. et al. The impact of students’ positive academic emotions on learning engagement in the context of the specialized delivery classroom (published manuscript of China). Chin. J. Educational Technol. 9, 91–100 (2023).

Mao, Y., Yang, R., Bonaiuto, M., Ma, J. & Harmat, L. Can flow alleviate anxiety? The roles of academic self-efficacy and self-esteem in building psychological sustainability and resilience. Sustainability 12 (7). https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072987 (2020). Article 2987.

Sainio, P., Eklund, K., Hirvonen, R., Ahonen, T. & Kiuru, N. Adolescents’ academic emotions and academic achievement across the transition to lower secondary school: the role of learning difficulties. Scandinavian J. Educational Res. 65 (3), 385–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2019.1705900 (2021).

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. & Anderson, D. Social interdependence and classroom climate. J. Psychol. 114 (1), 135–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.83 (1983).

Schaufeli, W. B., Martinez, I. M., Pinto, A. M., Salanova, M. & Bakker, A. B. Burnout and engagement in university students: a cross-national study. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 33 (5), 464–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022102033005003 (2002).

Liu, H., Yao, M., Li, R. & Zhang, L. The relationship between regulatory focus and learning engagement among Chinese adolescents. Educational Psychol. 40 (4), 430–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2019.1618441 (2020).

Campbell-Sills, L. & Stein, M. B. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the connor–davidson resilience scale (CD‐RISC): validation of a 10‐item measure of resilience. J. Trauma. Stress: Official Publication Int. Soc. Trauma. Stress Stud. 20 (6), 1019–1028. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20271 (2007).

Connor, K. M. & Davidson, J. R. T. Development of a new resilience scale: the connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety. 18 (2), 76–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113 (2003).

She, R., Yang, X., Lau, M. M. & Lau, J. T. Psychometric properties and normative data of the 10-item Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale among Chinese adolescent students in Hong Kong. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 51, 925–933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-020-00970-1 (2020).

Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A. & Furrer, C. J. A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection: conceptualization and assessment of children’s behavioral and emotional participation in academic activities in the classroom. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 69 (3), 493–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164408323233 (2009).

Wu, S. & Sun, B. The impact of students’ adaptability on learning engagement in the context of the epidemic: the mediating effect of academic emotions (published manuscript of China). Contemp. Educational Sci. 8, 87–95 (2021).

Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 (2003).

Zhou, H. & Long, L. R. Statistical remedies for common method biases. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 12, 942–950. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 (2004).

Yockey, R. D. SPSS is actually very simple (published book). Liu, C., Wu, Z. translating. China Renmin University Press (2010).

Abed, S. S. Social commerce adoption using TOE framework: an empirical investigation of Saudi Arabian SMEs. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 53, 102118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102118 (2020).

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104 (1981).

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M. & Ringle, C. M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 31 (1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203 (2019).

Jackson, D. L., Gillaspy, J. A. Jr & Purc-Stephenson, R. Reporting practices in confirmatory factor analysis: an overview and some recommendations. Psychol. Methods. 14 (1), 6–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014694 (2009).

MacKinnon, D. P. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis (Routledge, 2012).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications (2022).

Wen, Z. & Ye, P. Mediated model testing methods with moderation: competition or substitution? (published manuscript of China). J. Psychol. 46 (5), 714–726 (2014).

Cameron, A. C. & Windmeijer, F. A. An R-squared measure of goodness of fit for some common nonlinear regression models. J. Econ. 77 (2), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-4076(96)01818-0 (1997).

Sun, Y. The Relationship between Teacher Support, Learning Motivation, and College Students’ English Academic Performance (Unpublished master’s thesis of China). Shandong University of Finance and Economics (2023).

Xu, B. Mediating role of academic self-efficacy and academic emotions in the relationship between teacher support and academic achievement. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 24705. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75768-5 (2024).

Fang, G., Wing Keung, C. P. & Penelope, K. Social support and academic achievement of Chinese low-income children: a mediation effect of academic resilience. Int. J. Psychol. Res. 13 (1), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.21500/20112084.4480 (2020).

Xu, H. The effect of positive emotions on college students’ academic resilience (published manuscript of China). High. Educ. Res. 3, 74–77 (2015).

Amitay, G. & Gumpel, T. Academic self-efficacy as a resilience factor among adjudicated girls. Int. J. Adolescence Youth. 20 (2), 202–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2013.785437 (2015).

Sesma, A., Mannes, M. & Scales, P. C. Positive adaptation, resilience and the developmental assets framework. In S. Goldstein & R.B. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of Resilience in Children (pp. 427–442). Springer Science + Business Media New York. (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3661-4_25

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Special Project on “Foreign Language Teaching Reform in the Context of High-quality Development” for Foreign Language Education in Jiangsu Universities in 2024 (2024WYJG022) and the 2023 Huaiyin Normal University Teacher Education Collaborative Research Project “Innovation in Foreign Language Education from the Perspective of Building a Community with a Shared Future for Mankind” (2023JSY009). We are grateful to Chao Zhang and Lijuan Wang for their contributions to data collection and entry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y. conceptualized and designed the study, and wrote the first draft. F.Y. and L.G. collected data. Z.X analyzed the data and polished the language. Z.L. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shao, Y., Feng, Y., Zhao, X. et al. Teacher support and secondary school students’ learning engagement: A moderated mediation model. Sci Rep 15, 2974 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87366-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87366-0