Abstract

This study investigates the impact of irrigation water sources on the quality of olive oil from the Chemlal olive variety in the Hadjadj region, northeast of Mostaganem, Algeria, a coastal area known for its semi-arid climate and intensive olive cultivation. Olive trees (n = 50 per irrigation group) were irrigated with treated wastewater, spring water, and normal water, and the resulting oils were assessed for physicochemical properties, fatty acid composition, and bioactive compound profiles. Treated wastewater demonstrated distinct water quality characteristics, including elevated temperature (15.00 °C), chemical oxygen demand (COD: 58.38 mg/L), biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5: 29.00 mg/L), ammonium (15.60 mg/L), nitrite (2.55 mg/L), suspended solids (14.00 mg/L), pH (7.40), and conductivity (2.80 µS/cm), reflecting residual organic material and ionic content post-treatment. Heavy metal concentrations in all water sources were within permissible limits for irrigation and drinking purposes, affirming their safety for agricultural use. Olive oil from treated wastewater-irrigated trees exhibited superior quality parameters, including low acidity (1.99%), low peroxide value (6.8 meq O2/kg), enhanced oxidative stability, higher fat content (96.5%), and favorable saponification values. Fatty acid analysis revealed a higher oleic acid content (62.6 mg/kg), known for cardiovascular health benefits. Bioactive compound analysis indicated significantly elevated levels of α-tocopherol (180.25 mg/kg), squalene (7500.8 mg/kg), carotenoids (25.1 mg/kg), and polyphenols (604.76 mg GAE/kg), contributing to increased antioxidant capacity (63.50% DPPH inhibition, a measure of free radical scavenging) and lower lipid peroxidation (0.25 TBARS, an index of oxidative degradation), indicative of superior oxidative stability. Spring water-irrigated oils showed higher acidity, peroxide values, and linoleic acid concentrations, alongside notable antibacterial efficacy against Escherichia. coli, Pseudomonas. aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus. aureus. Oils from normal water irrigation were characterized by higher linolenic acid levels, providing a more balanced fatty acid profile. These findings underscore treated wastewater’s potential to enhance olive oil’s nutritional and functional qualities, particularly its antioxidant activity and stability, while highlighting the role of spring water in enhancing antibacterial properties despite slightly reduced antioxidant stability. These findings are relevant to water-scarce Mediterranean and arid regions, informing sustainable irrigation strategies in line with global climate-resilient agriculture policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Olive oil is a fundamental component of the Mediterranean diet, known for its diverse health-promoting attributes, including potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, alongside its protective role in cardiovascular health1,2. In Algeria, olive oil production plays a pivotal role in the agricultural sector, contributing to the national economy and the livelihoods of many farmers across the country3. The quality of olive oil is primarily assessed through its physicochemical properties, including acidity, peroxide value, and UV absorption as well as its fatty acid composition. These parameters are critical in determining olive oil’s purity, oxidative stability, and nutritional value, which directly influence its commercial quality and health benefits4.

The region faces a critical challenge such as water scarcity. This scarcity is exacerbated by climate change, increasing water demand, and the limited availability of freshwater resources, making it imperative to find sustainable irrigation alternatives5. This study is particularly relevant for Algeria, where water scarcity is a pressing issue, and olive cultivation represents a significant part of the agricultural sector, making sustainable irrigation practices essential. Treated wastewater has increasingly been recognized as a viable and innovative solution to address water scarcity in agriculture. Treated wastewater, derived from municipal or industrial sources, undergoes biological and physical treatment processes, including aeration, sedimentation, and filtration, to ensure its suitability for irrigation6. Furthermore, utilizing treated wastewater in agriculture not only conserves freshwater resources but also provides a reliable water supply. Additionally, it enhances nutrient recycling and reduces the environmental impact of wastewater disposal7,8.

Previous research has investigated the feasibility and benefits of using treated wastewater in various agricultural contexts. These studies have examined the effects of various irrigation sources on olive oil composition, highlighting both benefits and challenges associated with wastewater reuse in agriculture. They have demonstrated that treated wastewater can effectively support crop growth and improve yield without posing significant health risks to consumers9. Furthermore, the reuse of treated wastewater offers an eco-friendly approach to resource management, aligning with sustainable agricultural practices. However, long-term use of treated wastewater has been associated with soil salinization and potential accumulation of heavy metals, which necessitates cautious implementation and monitoring. Factors such as the presence of residual contaminants, changes in soil chemistry, and the uptake of nutrients by olive trees could influence the sensory and chemical properties of the resulting olive oil. To address these concerns, this study thoroughly evaluates the impact of wastewater irrigation on olive oil composition, ensuring that potential risks are properly assessed7. Moreover, these concerns are especially pertinent in Algeria, where specific environmental conditions and agricultural practices could further impact the outcomes of wastewater irrigation10.

This study aims to investigate the impact of treated wastewater irrigation on the physicochemical properties, fatty acid composition and biological activities of olive oil produced in Algeria. Specifically, the research evaluates acidity, peroxide value, UV absorption, fatty acid profile, antioxidant and antibacterial activities, all of which are key indicators of oil stability and quality. By conducting a comprehensive analysis, this study aims to provide valuable insights that can inform agricultural practices and policies, promoting the sustainable use of water resources while ensuring the production of high-quality olive oil. To address these questions, this study evaluates olive oil quality from trees irrigated with normal water, spring water, and treated wastewater, using established analytical methods. Additionally, this research could contribute to global efforts in sustainable agriculture, offering a model for other regions facing similar water scarcity. By comparing different irrigation sources, this research contributes valuable data on sustainable water use in olive cultivation, offering insights into optimizing irrigation for quality oil production.

Results and discussion

Physicochemical properties of different water sources

The comparative analysis of water quality parameters for treated wastewater, spring water, and normal water sources provides valuable insights into the impacts of treatment processes and environmental factors on water chemistry. These findings are crucial for assessing the suitability of treated wastewater for agricultural applications, especially in regions experiencing water scarcity. Among the three water sources (Table 1), treated wastewater exhibited significantly (p < 0.05) the highest temperature (15.00 °C), followed by normal water (14.50 °C) and spring water (14.00 °C). The slightly elevated in treated wastewater can be attributed to thermal processes during the treatment process, a common outcome observed in processed effluents11,12. Elevated temperatures in treated effluents may impact microbial activity and the chemical stability of certain compounds, this is particularly relevant where the potential use of treated wastewater is a consideration for specific agricultural or industrial uses. Treated wastewater exhibited the significantly (p < 0.05) highest chemical oxygen demand (COD) levels (58.38 mg/L), indicating that residual organic material persists even after treatment. In comparison, COD levels were lower in normal water (30.00 mg/L) and significantly (p < 0.05) lower in spring water (15.00 mg/L). These results are consistent with previous researches, which indicate that certain organic compounds are resistant to conventional wastewater treatment methods, suggesting that additional treatment steps may be needed if the effluent is to be used in settings sensitive to organic contamination13,14. Biochemical oxygen demand (BOD₅) levels were also significantly (p < 0.05) higher in treated wastewater (29.00 mg/L) compared to normal water (10.00 mg/L) and spring water (6.00 mg/L). These elevated levels in treated wastewater highlight the presence of biodegradable organic com-pounds that may not have been fully decomposed during treatment process. High BOD₅ values in treated wastewater could impact its reuse in oxygen-sensitive environments, such as irrigation for crops or soils that are vulnerable to oxygen depletion. The COD and BOD₅ values of the treated wastewater were within the WHO permissible limits for agricultural irrigation (COD < 250 mg/L; BOD₅ < 100 mg/L), indicating its suitability for field use. These findings align with prior research demonstrating partial biodegradation of organic matter in treat-ed effluents11,15.

Suspended solid concentrations also varied significantly (p < 0.05) highest among the water sources. Treated wastewater exhibited the highest levels (14.00 mg/L), reflecting residual particulate matter that may remain post-treatment. Spring water showed moderate levels (10.00 mg/L), while normal water recorded the lowest concentration (8.00 mg/L). This variability supports the efficiency of natural filtration processes in groundwater sources like wells, which reduce particulate loads compared to treated wastewater16,17. However, elevated suspended solids in treated wastewater could have implications for its reuse, as particulates may interfere with irrigation systems or contribute to sediment buildup in soil. Furthermore, Dissolved Oxygen (DO) levels were highest in treated wastewater (10.50 mg/L), likely due to aeration during the treatment process, a step commonly used to improve DO levels in effluents18. By contrast, DO levels in spring water (8.00 mg/L) and normal water (8.22 mg/L) were slightly lower, reflecting natural oxygenation without artificial intervention. Moreover, high DO in treated wastewater can be beneficial for certain applications, as it may enhance aerobic processes in soil and support microbial communities important for nutrient cycling19.

The pH varied among the three water sources, with treated wastewater exhibiting a significantly (p < 0.05) higher pH (7.40), possibly due to the buffering agents applied during the treatment process. Additionally, normal water displayed a moderate pH (7.09), while spring water showed a significantly (p < 0.05) lower pH (6.50). These differences in pH can significantly influence nutrient solubility and availability, impacting the suitability of these water sources for reuse. Furthermore, the observed stability in treated wastewater pH aligns with previous findings on effluent treatment processes15,16. Proper pH management in treated wastewater is crucial for its reuse, as even slight deviations can affect soil chemistry, microbial activity, and overall plant health. In terms of nutrient content, treated wastewater had the significantly (p < 0.05) highest ammonium (NH₄⁺) concentration (7.32 mg/L), suggesting that nutrient retention remains a challenge in standard treatment processes. Elevated ammonium levels are a common characteristic of treated effluent, consistent with observations reported by Zhao et al.20. In contrast, normal water and spring water had significantly lower ammonium concentrations, reflecting fewer nutrient inputs or lower contamination levels in these sources. However, high ammonium in treated wastewater could pose a risk of nutrient leaching in soils, which may lead to water quality issues in surrounding ecosystems21. Nitrite (N-NO₂⁻) was also significantly (p < 0.05) higher in treated wastewater (15.60 mg/L), indicative of ongoing nitrogen transformations within the treatment facility. In contrast, spring water (0.10 mg/L) and normal water (1.97 mg/L) demonstrated much lower nitrite levels, which may be attributed to limited organic input and natural degradation processes in these sources17,22. Furthermore, elevated nitrite concentrations in treated wastewater could limit its reuse for certain applications, due to the potential for nitrogen toxicity. Addition-ally, nitrate (N-NO₃⁻) levels were highest in treated wastewater (2.55 mg/L), likely a result of nitrification processes during treatment. Moderate levels were observed in spring water (0.50 mg/L), while the lowest levels were found in normal water (0.26 mg/L. This nitrate distribution is consistent with findings on the natural stability of nitrate in groundwater, as reported in earlier studies16,17. However, the accumulation of nitrogen-based compounds in treated wastewater shows the importance of enhancing the treatment processes in order to make them efficient for the reuse of water in agricultural or environmental usages.

Conductivity is a way of measuring the capacity of a solution to allow electric current through it. This gives an idea of the salt, acid or base ions present in water. In the context of water quality, conductivity is an useful parameter because it gives an idea about the total ionic load of the water which has implications in its acceptability for different end uses including drinking, irrigation and industrial uses23. Conductivity as presented in (Table 1), was significantly (p < 0.05) highest in treated wastewater (2.80 µS/cm), reflecting the presence of residual ions remaining after the treatment process. Furthermore, normal water exhibited moderate conductivity (2.24 µS/cm), while spring water had lowest conductivity (2.12 µS/cm). This trend is consistent with lower ionic content typically found in natural water sources. Moreover, the elevated conductivity in treated wastewater suggests that residual salts may remain post-treatment, which could affect soil structure and plant health over time, especially if this water is reused for irrigation. In other words, High conductivity in water typically indicates higher levels of dissolved salt which can affect waters suitability for various uses, including agriculture, drinking, or aquatic ecosystem. Conversely low conductivity suggests fewer dissolved ions and is often associated with purer water16,24. Phosphate (PO₄³⁻) concentrations were also highest in treated wastewater (4.70 mg/L) likely due the partial retention of phosphorus during the treatment process. Additionally, spring water (4.50 mg/L) and normal water (4.11 mg/L) showed slightly lower phosphate levels, reflecting minimal anthropogenic influence and natural phosphorus cycling in these sources. However, excess phosphate in treated wastewater poses environmental risks such as eutrophication in receiving water bodies, which can disrupt aquatic ecosystems. Otherwise, some studies suggest that phosphorus recovery technology could trans-form this nutrient into a valuable resource, supporting agriculture nutrient recycling and reducing the environmental burden24,25. This analysis demonstrates that treated wastewater has the potential for reuse, particularly in agricultural applications, though However, certain parameters such as elevated COD, BOD₅, ammonium, nitrite, and conductivity warrant careful monitoring and management. Furthermore, while current treatment processes significantly reduce the organic load and nutrient levels, residual concentrations of certain compounds suggest that additional treatment or targeted interventions may be necessary to mitigate environmental and agriculture risks. treatment effectively reduces organic load and nutrient levels; residual concentrations of certain compounds suggest that additional processing or targeted management may be necessary to mitigate environmental risks. These findings contribute to the growing body of research supporting the safe and sustainable reuse of treated wastewater in water-scarce regions, where careful oversight can ensure both environmental health and agricultural productivity18.

Heavy metals composition of different water sources

The analysis revealed that the concentrations of heavy metal in spring water, treated wastewater, and normal water were within permissible limits for both drinking and irrigation purposes (Table 2). Specifically, lead (Pb) levels ranged from 0.005 to 0.008 mg/L, cadmium (Cd) from 0.002 to 0.004 mg/L, mercury (Hg) from 0.0005 to 0.0008 mg/L, and nickel (Ni) from 0.01 to 0.015 mg/L, all compliant with standard safety thresholds26,27. Moreover, these results suggest that natural filtration processes in spring water effectively minimize heavy metal contamination, while the treatment processes for wastewater sufficiently reduce metal concentrations to safe levels., This finding aligns with previous studies by Agoro et al.28 and Shrestha et al.29, which emphasize the efficacy of both natural and engineered filtration systems. However, slightly higher concentrations of heavy metal in treated wastewater and normal water compared to spring water indicate external factors, such as urban runoff and proximity to contamination sources like industrial sites and agricultural activities, as potential contributors30. Furthermore, while the observed heavy metal concentrations are within safe limits, the potential for bioaccumulation in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystem remains a concern. For instance, interactions between heavy metals and emerging contaminants including microplastic and persistent organic pollutants, could amplify their environmental and health impact31. Additionally, long -term exposure, even at low levels, may pose risks to human health and agriculture productivity. To ensure the continued safety and quality of water resources, continuous monitoring and the advancement of wastewater treatment technologies are recommended.

Physicochemical properties of olive oil

The acid value a key indicator of free fatty acid content and hydrolytic degradation in olive oil, varied significantly (p < 0.05) among the samples analyzed in this study (Table 3). The highest acid value was observed in olive oil from trees irrigated with spring water (5.06 mg KOH/g), followed by those irrigated with treated wastewater (3.94 mg KOH/g) and normal water (2.87 mg KOH/g). the acid value is a marker of the oil’s freshness and quality. A lower acid value indicates fresher, more stable, and higher-quality oil, while a higher acid value suggests degradation and poorer quality. Furthermore, these findings are consistent with research by Balesteros et al.32, who highlighted that higher acidity values in olive oils correlates with reduced quality, often attributed to increased triglyceride hydrolysis, which aligns with our findings that spring water irrigation, perhaps due to contaminants or specific ionic compositions, contributes to a higher acid value, therefore reduced stability. Additionally, Grossi et al.33 developed an electrochemical impedance spectroscopy method for rapid determination of olive oil acidity, demonstrated that environ-mental factors, such as irrigation practices, significantly influence acid values. Moreover, the differences in acid values observed in this study attributed to the distinct mineral content and potential impurities in the water sources used for irrigation. Al Shdiefat et al.34 similarly reported that reclaimed wastewater can alter olive oil acidity, suggesting that specific water quality parameter such as salinity, ion concentration, and organic matter, play a crucial role in oil composition and stability. The higher acidity observed in olive oil from spring water-irrigated trees may also be linked to the microbial activity or specific mineral content present in spring water. Spring sources, though generally clean, can harbor naturally occurring microbial communities or trace elements (e.g., iron, manganese, or sulfate) that may influence the rhizosphere and promote enzymatic hydrolysis of triglycerides, leading to elevated free fatty acid levels. Additionally, certain minerals can act as cofactors for lipase activity, potentially accelerating lipid breakdown. Similar associations between irrigation water quality and increased oil acidity have been reported by Conde-Innamorato et al.35, who found that irrigation practices influenced olive oil acidity, possibly due to interactions between environmental conditions, water composition, and enzymatic activity in the fruit tissues.

Similarly, the free acidity levels in our samples followed a comparable trend, with spring water-irrigated samples showing the highest acidity (2.53%) and normal water samples the lowest (1.45%). According to Bedbabis et al.36, irrigation with treated wastewater led to free acidity levels that were lower than those observed with other types of irrigation, potentially due to the stabilizing effect of specific nutrients in the wastewater. This finding aligns with our result that treated wastewater produced oil with lower free acidity compared to spring water. The variations in acidity across water sources may be due to the presence of trace elements or organic compounds that affect lipid stability, as discussed in studies by Ben Brahim et al.37 and Roiaini et al.38 found that water quality impacts enzymatic activities responsible for hydrolysis in olive oils, which could explain the trends observed in this study.

The peroxide value, a critical measure of primary oxidation in olive oil, exhibited significant difference (p < 0.05) across irrigation treatment, with highest value recorded in the spring water-irrigated sample (14.60 meq O2/kg) and lowest in the treated wastewater-irrigated sample (6.80 meq O2/kg) (Table 3). These results suggest that spring water irrigation may contribute to increase oxidative instability, potentially due to the presence of trace metals or organic residues that act as pro-oxidants. All peroxide values were below the international olive oil council (IOOC) limit of 20 mg O2/kg, indicating good oxidative stability across treatments. Zhang et al.39 highlighted the environmental factors, such as mineral composition in irrigation water, could elevate peroxide values in edible oils. This is consistent with our finding that spring water-irrigated oil had the highest peroxide value, suggesting greater oxidative stress. Conversely, treated wastewater-irrigated samples demonstrated the lowest peroxide values, suggesting improved oxidative stability. This finding is consistent with Bedbabis et al.36, who reported reduced oxidative degradation in olive oil irrigated with treated wastewater. Moreover, the stabilization effect of treated wastewater may be explained by its lower concentration of pro-oxidative minerals or organic contaminates34.

The saponification value, an indicator of the average molecular weight of fatty acids, varied significantly (p < 0.05) among samples (Table 3). The highest saponification value was recorded in the spring water-irrigated oil (194.04 mg KOH/g), while the lowest was observed in the treated wastewater oil (181.02 mg KOH/g). Elevated saponification values, such as those found in the spring water-irrigated oil, suggest a higher proportion of shorter-chain fatty acids. This aligns with finding by de Medina et al.40, who reported that shifts in saponification values reflect changes in fatty acid composition, potentially due to environmental or cultivation factors. Vani et al.41 suggests that for edible oils, lower saponification values are generally preferable, as they indicate a more stable oil with long-er-chain fatty acids, which are beneficial for both health and cooking. Furthermore, Alajtal et al.42, demonstrated the composition of irrigation water significantly effects the fatty acid profile in vegetable oils. These research supports our observation that treated wastewater irrigation may favor the production of longer-chain fatty acid, contributing to a lower saponification value. In the term of drying index, which reflect the oil’s stability to form a film upon are exposure, showed minimal variation across the oil samples, ranging from 7.20 to 7.73 (Table 3). This indicates that the type of water source used for irrigation has a limited impact on the drying properties of olive oil. Yunus et al.43, noted the drying index is more strongly influenced by the degree of unsaturation in the oil’s fatty acid rather than by external factors such as irrigation water composition. Which may explain the minimal impact of irrigation type on this parameter. This finding suggests that drying index is largely determined by the intrinsic fatty acid composition of the oil rather than external factors, as supported by Kharazi et al.44.

The refractive index of olive oil showed slightly variation, as presented in (Table 3), though the differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). The highest refractive index was observed in the oil from treated wastewater-irrigated olives (1.468), followed by normal water-irrigated oil (1.462) and spring water-irrigated oil (1.456). This parameter provides insights into the oil’s purity and composition characteristic. Higher refractive indices are often indicative of increased unsaturated fat content or other minor components. Yunus et al.43 reported that variations in refractive index could reflect differences in triglyceride, potentially signaling shifts in oil purity. The slight increase in refractive index in the treated wastewater sample may indicate a higher unsaturated fatty acid content, which is generally associated with health oils, as unsaturated fats are beneficial for cardiovascular health. This aligns with Cobzaru et al.45, who attributed changes refractive index to compositional shifts influenced by storage or environmental factors. The specific extinction coefficients (K270 and K232), which serve as indicator of secondary oxidation and the presence of conjugated dienes and trienes, exhibited the highest values in the spring water-irrigated olives (K270: 0.112; K232: 2.268) and lowest in the treated wastewater-irrigated olives (K270: 0.059; K232: 1.611). Elevated K values are associated with greater oxidative degradation, possibly driven by contaminates or trace metals in spring water that act as pro-oxidant. Lolis et al.46 reported that K values rise significantly under storage conditions favoring oxidation, such as prolonged storage or exposure to environmental stressor. Conversely, the lower K values in the treated wastewater indicate reduced oxidative stress and greater oil stability. These results are consistent with Ben Brahim et al.37, who found that treated wastewater irrigation can mitigate oxidative degradation in olive oil, potentially due to its unique composition that limits pro-oxidant interaction.

Lastly, the iodine value, a key indicator of the degree of unsaturation in oils, varied significantly (p < 0.05) across the samples, as shown in (Table 3). The treated wastewater-irrigated sample iodine value (93.9 g I2/100 g oil), followed up by the normal water-irrigated sample (85.90 I2/100 g oil), with the spring water-irrigated sample showing the lowest value (77.54 g I2/100 g oil). Higher iodine values suggest a greater proportion on unsaturated fatty acid, which are nutritionally advantageous but more prone to oxidation. Yang et al.47 emphasized that oils with elevated iodine value typically exhibit improved nutritional profiles due to their higher content of unsaturated fatty acid, aligning with our result for treated wastewater. The reduced iodine value in the spring water sample may reflect a lower degree of unsaturation, potentially due to shorter-chain fatty acid profiles as indicated by the saponification values. The relationship between irrigation practices and unsaturation levels is also reported by García Martín48, who found that irrigation practices significantly impact fatty acid unsaturation level in olive oil.

Impact of irrigation water sources on olive oil composition

The olive oil from wastewater-irrigated samples (Table 4) exhibited the highest dry matter content (0.46%) significantly (p < 0.05) exceeding that of oils from normal water-irrigated (0.14%) and spring water-irrigated sample (0.03%). Elevated dry matter levels reflect a greater concentration of solid component in the oil, potentially enriching its nutritional value and bioactive compound profile, including polyphenol and antioxidant. Yubero Serrano et al.49 highlighted the critical role of polyphenol in enhancing olive oil health benefits, oxidative stability, and resistance to rancidity. The nutrient-enriched treated wastewater likely contributes to the accumulation of these beneficial compounds, suggesting that such irrigation practices could yield olive oil with nutritional and functional properties. Furthermore, fat content, another vital attribute of olive oil, serve as marker of caloric density, quality, and stability. Among the samples, the treated wastewater-irrigated oil exhibited the highest fat content (96.50%), followed by oil from spring water irrigation (95.33%) and normal water irrigation (93.33%). The elevated fat content in wastewater-irrigated oil may indicate a reduce rate of lipid oxidation, as higher fat concentrations often correlate with better preservation of lipid integrity. Boskou et al.50 emphasized that lipid oxidation significantly affects fat content and overall oil quality. The result suggest that treated wastewater might contain minerals or bioactive com-pounds with mild antioxidant proprieties, which could stabilize lipid structure and enhance oil quality. Moreover, this finding supports the hypothesis that nutrient availability directly influences lipid synthesis and retention in olive oil51.

The mineral matter content in the olive oil derived from wastewater-irrigated oil (0.01 g) was significantly (p < 0.05) higher compared to those irrigated with normal water (0.002 g) and spring water (0.001 g) (Table 4). Although olive oil typically contains minimal minerals levels, the absorption of certain minerals from treated wastewater could enhance its nutritional profiles and contribute to its antioxidant proprieties. For instance, minerals like potassium, calcium, and magnesium. Which commonly found in treated wastewater, play a crucial role in enzymatic activity within olive trees, potentially influencing both the stability and quality of the oil. furthermore, these minerals may positively impact oxidative stability, helping to prolong the shelf life and retain the functional proprieties of the oil52,53. The elevated mineral content in wastewater oil (0.01 g) may contribute to subtle sensory changes such as increased bitterness, while also enhancing micronutrient value. However, it remains essential to carefully monitor the mineral composition to prevent the accumulation of harmful heavy metals, which could pose health risks. As shown in (Table 4), the moisture content was lowest in the treated wastewater-irrigated oil (0.02%), compared to the normal water-irrigated oil (0.17%), and spring water-irrigated oil (0.23%). Notably, lower moisture content level are highly advantageous for olive oil stability, as they minimize the risk of microbial growth and hydrolytic rancidity54. As a result, oil with lower moisture content is less prone to spoilage and oxidative degradation, thereby exhibiting improved storage stability.

Impact of irrigation water sources on fatty acid profile of olive oil

The fatty acid composition of olive oil is a key determinant of its nutritional quality, stability, and health benefits. This study examines the impact of different irrigation water sources treated wastewater, normal water, and spring water on the fatty acid profile of olive oil. The results, presented in (Table 5), highlight significant variations in saturated (SFA), monounsaturated (MUFA), and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) across the three irrigation treatments.

That fatty acid composition of olive oil (Table 5), particularly monounsaturated (MUFA) and polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA), showed significant difference (p < 0.05) across different irrigation treatments. Treated wastewater irrigation resulted in the highest concentration of oleic acid (62.60 mg/kg), a predominant MUFA recognized cardiovascular benefit. The oleic acid content of 62.6 mg/kg in treated wastewater-irrigated samples is consistent with, and in some cases exceeds, values reported for high-quality Mediterranean olive oils. For example, Spanish cultivars such as Picual and Arbequina typically contain oleic acid concentrations ranging from 55 to 75 mg/kg, while Italian varieties like Frantoio and Leccino also fall within this range37,50. This positions the Chemlal variety, under treated wastewater irrigation, as competitive in oleic richness with internationally recognized oils, affirming its potential nutritional and commercial value under water-scarce Algerian conditions. This observation aligns with findings by Tome-Rodriguez55 and Al-Bachir & Sahloul56, who highlighted the influence of environmental factors, such as irrigation type on fatty acid profiles. Moreover, Ben Brahim et al.37 found that both treated wastewater and olive mill wastewater irrigation could significantly alter the fatty acid profile and bioactive compounds of olive oil, supporting the results observed in this study. Additionally, Boskou et al.50 further underscore the important of MUFAs, particularly oleic acid in enhancing olive oil’s stability, quality and health-promoting proprieties. The elevated oleic acid level observed in this study suggest that treated wastewater irrigation may favor the synthesis of beneficial MUFAs. Conversely, spring water irrigation recorded the highest level of linoleic acid (10.83 mg/kg). this finding is consistent with Monfreda et al.57, who reported that fatty acid such as linoleic acid serve as critical indicator of oil quality. Ben Brahim et al.37 also reported that irrigation practices including the use of wastewater, significantly influence the concentration of both MUFAs and PUFAs in olive oil. The influence of water type on saturated fatty acids (SFA) was also notable. Butyric acid levels were similar in treated wastewater (0.010 mg/kg) and spring water (0.009 mg/kg), with normal water showing a slightly higher concentration (0.013 mg/kg), which may favor gut health benefits due to the role of short-chain fatty ac-ids like butyric acid. Myristic acid showed little variation across treatments (0.200, 0.201, and 0.203 mg/kg), indicating it is unaffected by water source. However, heptadecanoic acid was significantly higher in spring water (0.400 mg/kg) compared to normal and treated wastewater (0.03 mg/kg), which may have positive implications for metabolic health, as shown in other studies. Treated wastewater samples showed elevated palmitic acid levels (10.50 mg/kg) compared to normal water (3.42 mg/kg) and spring water (2.20 mg/kg), which could impact cardiovascular health due to its association with LDL cholesterol elevation. Normal water yielded the highest levels of stearic acid (3.56 mg/kg), which is a saturated fat with a neutral effect on cholesterol, making it less harmful com-pared to other SFAs.

In monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) (Table 5), palmitoleic acid was highest in spring water (6.45 mg/kg), followed by normal water (3.21 mg/kg) and treated wastewater (0.81 mg/kg), potentially enhancing anti-inflammatory properties under spring water conditions. Oleic acid concentration was highest in treated wastewater (62.60 mg/kg), slightly surpassing spring water (60.26 mg/kg) and normal water (50.37 mg/kg), reflecting the benefits for cardiovascular health associated with oleic acid-rich oils. In contrast, vaccenic acid levels were highest in normal water (1.83 mg/kg), which is beneficial for lipid profiles. The presence of erucic acid and eicosenoic acid showed only slight variation across the three sources, indicating relative stability in content regardless of irrigation type. For polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), spring water supported the highest linoleic acid levels (10.83 mg/kg), followed by normal water (8.42 mg/kg) and treated wastewater (6.80 mg/kg), enhancing the nutritional quality due to linoleic acid’s essential role in diet. Linolenic acid, known for anti-inflammatory properties, was notably higher in normal water samples (1.79 mg/kg) compared to treated wastewater (0.65 mg/kg) and spring water (0.33 mg/kg), suggesting that normal water irrigation supports healthier PUFA profiles. Normal water also favored arachidic acid synthesis (2.01 mg/kg), contributing to a more balanced PUFA profile compared to the other water types. The lipid classes, diacylglycerols and monoacylglycerols, showed the highest percentages under treated wastewater irrigation. Diacylglycerols reached 2.53% in treated wastewater samples, followed by 1.82% in normal water and 1.67% in spring water, while monoacylglycerols were 0.30% in treated wastewater, decreasing to 0.25% and 0.20% in normal and spring water, respectively. This increase may reflect a metabolic response, enhancing energy storage and possibly contributing to better stability and functionality in oil.

The fatty acid composition observed in this study shows both consistencies and divergences when compared to Bedbabis et al.36, who investigated the impact of treated wastewater on olive oil from the Chemlali cultivar. In our case, oleic acid levels reached 62.6%, which is within the range (60.3–64.1%) as reported by Bedbabis et al.36 under similar irrigation conditions. However, we observed slightly higher linoleic acid values and lower palmitic acid concentrations, which may be attributed to differences in climatic conditions, irrigation frequency, and olive maturity at harvest. These findings reinforce the idea that while wastewater irrigation generally maintains the monounsaturated-rich profile of olive oil, minor variations in saturated and polyunsaturated fractions can arise due to local environmental or agronomic factors.

The calculated PUFA/SFA ratios were 0.89 (treated wastewater), 1.22 (normal water), and 1.79 (spring water), indicating variation in nutritional quality across irrigation types. Although the highest ratio was observed with spring water, suggesting a potentially more favorable lipid profile for cardiovascular health, the treated wastewater oil maintained a better overall balance of bioactive compounds and oxidative stability.

Impact of irrigation water sources on bioactive compounds of olive oil

The influence of different water sources treated wastewater, normal water, and spring water on the sterol content, and pigment concentrations highlights the potential for treated wastewater irrigation to modify olive oil composition and enhance bioactive compounds (Table 6). Notably, these changes have significant implication for the oil’s nutritional value and associated health benefits. As shown in (Table 6), olive oil derived from treated wastewater-irrigated sample exhibited elevated levels of essential bioactive compounds, including α-tocopherol, carotenoids, squalene and chlorophylls. These finding align with results reported by Jimenez-Lopez et al.3 and Gonzalez-Hedstrom et al.58, who emphasize the vital role of tocopherols and squalene as antioxidant. Furthermore, these compounds contribute to reducing oxidative stress, improving oil stability and extending shelf life. Basheer et al.59 similarly reported that reclaimed wastewater irrigation positively influences olive oil quality by enhancing the concentration of bioactive compounds.

The sterol content in treated wastewater-irrigated plants was significantly higher (2800.56 mg/kg) compared to other irrigation methods (Table 6). This observation aligns with Gutiérrez-Luna et al.60, who demonstrated the critical role of sterols in enhancing the nutritional and health benefits of vegetable oils, as well as improving their overall quality. Similarly, Sdiri et al.61 and Basheer et al.59 demonstrated that wastewater irrigation can elevate sterol and antioxidant levels, suggesting that such practices positively influence the bioactive lipid profile of oils. The elevated sterol content observed in this study may also provide additional stability to the oil, reducing oxidative degradation, as noted by Jimenez-Lopez et al.3. Additionally, treated wastewater-irrigated samples exhibited notably higher levels of squalene (7500.80 mg/kg). This aligns with findings by Bourazanis et al.62 and Tekaya et al.63, who reported that wastewater irrigation could modify oil composition, potentially enhancing beneficial compounds like squalene, known for its anticarcinogenic properties and antioxidant benefits. Gutiérrez-Luna et al.60 also highlights the importance of squalene in enhancing the nutritional value of vegetable oils, suggesting that treated wastewater could offer a means to boost squalene con-tent in crops.

The enhanced levels of antioxidants like tocopherols and pigments in treated wastewater samples could be indicative of a defense response to the nutrient or stress conditions presented by this irrigation type. In this study (Table 6), treated wastewater irrigation led to the highest α-tocopherol concentration (180.25 mg/kg), followed by normal water (120.75 mg/kg) and spring water (90.50 mg/kg). The α-tocopherol content of 180.25 mg/kg observed in the Chemlal olive oil under treated wastewater irrigation is relatively high compared to values reported for Algerian and Mediterranean cultivars. Previous studies on Chemlal olives typically report α-tocopherol levels ranging from 90 to 150 mg/kg, depending on environmental conditions, cultivar maturity, and irrigation practices3,37. Therefore, the level measured in this study can be considered exceptional, suggesting that treated wastewater irrigation may stimulate tocopherol biosynthesis or reduce oxidative degradation during fruit development. This enhancement reinforces the functional value of the oil, as α-tocopherol is a primary antioxidant that contributes both to oil stability and to human health benefits, particularly in protecting lipids from oxidative damage. α-Tocopherol is a potent antioxidant that plays a crucial role in protecting oils from oxidation and contributes to the stability and shelf life of the product. The findings are in line with Baptista et al.64, who emphasized the importance of α-tocopherol in enhancing the stability of emulsions containing olive oil. Similarly, Psomiadou et al.65 studied Greek virgin olive oils and identified α-tocopherol as a primary antioxidant component, reinforcing the role of tocopherol in maintaining the quality and health benefits of olive oil. The elevated levels of α-tocopherol in treated wastewater-irrigated samples may reflect a stress response, where plants produce more antioxidants in response to the nutrient profile or stress factors associated with wastewater.

Squalene content (Table 6) was also highest in treated wastewater-irrigated samples (7500.80 mg/kg), significantly higher than in normal (5000.45 mg/kg) and spring water-irrigated samples (3000.75 mg/kg). Squalene is a valuable bioactive compound known for its antioxidant and anticarcinogenic properties. The squalene content (7500.8 mg/kg) supports previous reports of its anticarcinogenic potential, highlighting its nutritional relevance66. The importance of squalene content in specific olive oil varieties, noting its health benefits and contribution to oil stability67. The increased squalene levels in treated wastewater-irrigated plants suggest that this irrigation method might stimulate the synthesis of this beneficial lipid, possibly due to stress-induced metabolic responses that promote squalene production as a protective mechanism. Regarding carotenoids, treated wastewater-irrigated plants demonstrated the highest levels of total carotenoids (25.10 mg/kg), with normal water-irrigated plants having 15.20 mg/kg and spring water-irrigated plants showing 10.35 mg/kg. Carotenoids are essential antioxidants that contribute to the oil’s color and stability, while also offering health benefits linked to reduced oxidative stress. Furthermore, the high carotenoid levels may enhance the golden-green hue of the oil, potentially increasing consumer visual appeal without compromising taste. Portarena et al.68 developed a rapid quantification method for the lutein/β-carotene ratio in olive oil using Raman spectroscopy, underscoring the importance of carotenoid profiling in evaluating oil quality. Additionally, Martín Vertedor et al.69 demonstrated the nutraceutical potential of olive oil enriched with lutein and zeaxanthin, highlighting the importance of these compounds in promoting eye health and reducing the risk of age-related macular degeneration. The enhanced total carotenoid levels in treated wastewater-irrigated samples suggest that this water source may induce carotenoid synthesis, possibly as a protective response to oxidative stress or nutrient variability.

β-Carotene, a specific carotenoid with pro-vitamin A activity, was most abundant in treated wastewater samples (0.60 mg/kg), followed by normal water (0.42 mg/kg) and spring water (0.23 mg/kg). β-Carotene’s antioxidant properties are well-documented, contributing to cellular protection against oxidative stress and enhancing the oil’s stability. Portarena et al.68 found that the β-carotene content in extra virgin olive oil is a quality indicator, providing insight into the nutritional profile of the oil. The elevated β-carotene levels in treated wastewater samples align with this observation, suggesting that wastewater irrigation could enhance the oil’s nutritional quality by boosting bioactive compounds. Lutein, another carotenoid with significant antioxidant properties, was also highest in treated wastewater samples (3.02 mg/kg), followed by normal water (2.01 mg/kg) and spring water (1.05 mg/kg). Lutein is known for its protective effects on eye health and its potential as a nutraceutical component in olive oil. Martín Vertedor et al.69 discussed the role of lutein-enriched olive oil as a nutraceutical agent, reinforcing the health benefits of lutein for human health. The increased lutein levels in treated wastewater-irrigated plants further support the hypothesis that nutrient-rich or stress-inducing irrigation sources can stimulate the production of protective bioactive compounds.

Overall, treated wastewater irrigation appears to boost the levels of key bioactive components, including α-tocopherol, squalene, β-carotene, lutein, and total carotenoids. This enhancement in bioactive compounds could improve the nutritional quality and health-promoting properties of the oil, adding value to agricultural products irrigated with treated wastewater. However, as noted by Baptista et al.64, while these elevated bioactive levels are beneficial, it is crucial to monitor the quality and safety of oils produced under different irrigation methods, particularly regarding potential contaminants in treated wastewater. Further research on the long-term safety and efficacy of using treated wastewater in agriculture is needed to ensure both consumer safety and environmental sustainability.

Impact of irrigation water sources on polyphenol and flavonoids content of olive oil

The polyphenol content was highest in treated wastewater-irrigated samples (604.76 mg GAE/kg), followed by normal water-irrigated samples (500.58 mg GAE/kg) and spring water-irrigated samples (226.89 mg GAE/kg) as shown in (Table 7). Polyphenols, recognized as key antioxidants in olive oil, are crucial for protecting against lipid oxidation and enhancing oxidative stability. The elevated polyphenol content in treated wastewater samples may be due to specific nutrients or trace elements in treated wastewater that stimulate polyphenol synthesis. This enhancement may specifically be attributed to the elevated levels of ammonium (NH₄⁺) in treated wastewater. Nitrogen in the form of ammonium is known to stimulate the phenylpropanoid pathway by upregulating key enzymes such as phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), which catalyzes the first step in polyphenol biosynthesis. As a result, increased nitrogen availability can trigger the accumulation of phenolic compounds as part of the plant’s metabolic adaptation to nutrient-rich or mildly stressful environments. This mechanism may explain the higher total polyphenol levels observed in the treated wastewater-irrigated olives in our study. A similar effect was reported by Gagliardi et al.70 in globe artichokes irrigated with treated wastewater, which showed an enhanced polyphenolic profile. In contrast, flavonoid content was highest in spring water-irrigated samples (125.72 mg EAQ/kg), and decreasing in normal water (72.57 mg EAQ/kg) and treated wastewater samples (63.03 mg EAQ/kg). While flavonoids also contribute to antioxidant activity, their synthesis appears more sensitive to environmental conditions. The higher flavonoid levels in spring water-irrigated samples may be attributed to the unique mineral composition or organic compounds in spring water, which could induce mild stress favorable for flavonoid production71. Salazar et al.72 reported the cardiovascular bene-fits of flavonoids, particularly when consumed through sources like olive oil, emphasizing their importance in antioxidant activity. The elevated flavonoid levels in spring water samples are consistent with findings from Fernández-Calderón et al.73, specific water conditions could promote flavonoid synthesis in plant-derived products such as propolis.

Antioxidant activity of olive oil across irrigation treatments

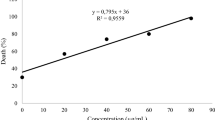

The 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) antioxidant activity, measured by free radical scavenging capacity (Table 7), was highest in treated wastewater-irrigated samples (63.50%), followed by normal water irrigated samples (48.06%) and spring water-irrigated samples (41.74%). A higher DPPH inhibition percentage indicates stronger antioxidant potential, which are likely at-tributed to the elevated polyphenol content observed in treated wastewater samples. Zullo and Ciafardini74 demonstrated that DPPH radical scavenging capacity can be used as a quality indicator for olive oil, where higher values correlate with better oxidative stability. Vasilescu et al.75 also utilized the DPPH assay to measure olive oil’s antioxidant properties, supporting the direct relationship between polyphenol concentration and enhanced DPPH inhibition.

The TBARS values (Table 7), which serve as markers of lipid peroxidation and oxidative degradation, were lowest in olive oil from treated wastewater-irrigated samples (0.25), followed by oils from normal water samples (0.36) and spring water samples (0.55). Lower TBARS values correspond to better oxidative stability, meaning that treated wastewater-irrigated oils exhibit greater resistance to oxidative processes. This is consistent with studies by Berasategi et al.76, who demonstrated that oils with elevated polyphenol content are less prone to degradation during heating. Similarly, Lammi et al.77 reported that polyphenol-rich olive oil extracts significantly reduce oxidative stress, supporting the protective effect of polyphenols against lipid oxidation and explaining the lower Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) values observed in treated wastewater samples. The influence of treated wastewater on polyphenol synthesis and overall antioxidant capacity is further supported by the review of Hoogendijk et al.78, who reported that irrigation with treated wastewater can enhance the nutritional and antioxidant properties of crops by altering their chemical composition. Cuellar et al.79 observed comparable effects in wastewater-irrigated plants, where in-creased polyphenol content was associated with higher antioxidant activity, which aligns with the higher antioxidant activity and lower TBARS values observed in our study. Additionally, the impact of sewage water on phenolic accumulation in plants, suggesting that treated wastewater may enhance polyphenol biosynthesis, contributing to higher antioxidant capacity in olive oil80.

Antibacterial effect of olive oil across irrigation treatments

The findings highlight a clear variation in the antibacterial efficacy of polyphenols against three bacterial pathogens: E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus (Table 8). Remarkably, polyphenols extracted from olives irrigated with spring water exhibited the highest antibacterial activity, as evidenced by inhibition zones measuring 14.8 mm for E. coli, 14.1 mm for P. aeruginosa, and 15.3 mm for S. aureus. In comparison, olives irrigated with normal water and treated wastewater demonstrated reduced antibacterial efficacy. The inhibition zones for E. coli were 13.5 and 12.0 mm, respectively, while for S. aureus, they measured 14.0 mm and 13.0 mm, respectively. Interestingly, the observed inhibition zone against S. aureus (15.35 mm) suggests the potential of olive oil, especially from treated wastewater irrigation, as a natural antimicrobial agent for food preservation.

These results align with the findings of Nazzaro et al.81, which emphasize the significant role of polyphenol content and composition in determining the antibacterial properties of olive oils. The efficacy variations can be attributed to differential polyphenol profiles, which are influenced by the water quality used in irrigation. As Guo et al.82 suggest, the mechanisms through which olive oil polyphenols exert their antibacterial effects such as disrupting bacterial cell walls and interfering with quorum sensing path-ways might be enhanced by higher polyphenol concentrations typically found in spring-water irrigated olives. The chemical profiles and antibacterial activity of olive polyphenols, similar to those found in other natural products like propolis, have been shown to possess high amounts of bioactive compounds73. This similarity supports the potential for synergistic effects, as explored by Tafesh et al.83, who report enhanced antibacterial activity through the combined effects of polyphenolic compounds from olive mill wastewater.

Materials and methods

Experimental station and pedoclimatic conditions

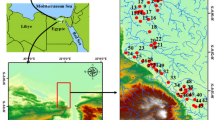

The investigation was conducted over two years (2022 and 2023) in Mostaganem, Algeria. The experimental field was located in the Hadjadj region (36.0703° N, 0.2084° E). The soil had a pH of 7.8, organic matter content of 1.9%, and was classified as clay-loam. This study focused on an olive grove, established in 2013, with trees planted at a distance of 8 × 8 m. The grove employs a dual-line drip irrigation system, with emitters spaced 50 cm apart, providing a flow rate of 4 l/h at 1 bar pressure. The olive grove is divided into two sections: one irrigated with normal water, the second with spring water, and the other with treated domestic wastewater from an aerated treatment facility. The normal water refers to tap water sourced from municipal groundwater supplies served as the control, allowing for direct comparisons between the effects of different water sources on tree growth and olive oil quality. The treated wastewater used in this study originates from an aerated treatment facility and underwent preliminary filtration, biological treatment, and chlorination to meet irrigation standards. The process includes aeration to promote microbial degradation of organic matter, sedimentation to remove suspended solids, and sand filtration to improve water clarity and quality. The spring water used for irrigation is sourced locally, drawn from a natural underground aquifer known for its mineral-rich composition and stable water quality. The grove exclusively features the Chemlal olive variety, which is primarily grown for oil production. The climate of the study area is semi-arid, with an average annual precipitation of 296 mm and a dry season spanning from May to September. The soil in the experimental plot is classified as sandy loam, consisting of 13.86% clay, 20.72% silt, and 65.42% sand. Each irrigation group consisted of 50 trees, randomly assigned based on field constraints and to ensure statistical power for comparing physicochemical and bioactive properties of oil across treatments. Daily meteorological data is recorded via a weather station located at the site, providing essential information for the study’s environmental monitoring.

Physicochemical analysis of water

The three types of irrigation water (normal water, spring water, and treated wastewater) were subjected for various physicochemical analysis. The parameters measured included pH, electrical conductivity (EC), total suspended solids (TSS), chemical oxygen demand (COD), and five-day biochemical oxygen demand (BOD5). Additionally, Phosphate ions (PO4 −3) were quantified, and bicarbonate ions (HCO3−) were measured through acid titration using hydrochloric acid (HCl). Nitrate (NO3−) concentrations were determined using a reflectometric technique with test strips, Furthermore, chlorine ions (Cl−) were quantified using Mohr’s titration method84. These analyses provided valuable insights about the water quality which is important when assessing the suitability of the water sources for irrigation.

Heavy metals analysis of water

The concentration of heavy metals, including lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), mercury (Hg), chromium (Cr), nickel (Ni), iron (Fe), copper (Cu), manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), cobalt (Co), and selenium (Se), was measured using Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) on a PerkinElmer Optima 8000 spectrometer (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA)85. Samples were prepared by acid digestion using a mixture of nitric acid (HNO₃) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in a microwave digestion system, ensuring complete dissolution of metal contents. The instrument was calibrated with multi-element certified standard solutions, and measurements were taken at specific analytical wavelengths for each metal to ensure precise quantification. Detection limits were established for each element, and quality control procedures included the use of blank samples, standard reference materials, and triplicate measurements to ensure reproducibility and accuracy. This analytical approach provided a high level of sensitivity and reliability, allowing for the precise determination of heavy metal concentrations in the irrigation water. The results were expressed in mg/L, facilitating direct comparison with regulatory thresholds for agricultural water safety.

To ensure the reliability of the safety assessment, the detection limits (LODs) of the ICP-OES method were established for each metal based on calibration standards and instrumental sensitivity. The LODs for the analyzed elements were as follows: lead (Pb), 0.001 mg/L; cadmium (Cd), 0.0002 mg/L; mercury (Hg), 0.0001 mg/L; nickel (Ni), 0.002 mg/L; zinc (Zn), 0.005 mg/L; arsenic (As), 0.0005 mg/L; chromium (Cr), 0.001 mg/L; copper (Cu), 0.005 mg/L; manganese (Mn), 0.001 mg/L; iron (Fe), 0.002 mg/L; cobalt (Co), 0.0005 mg/L; and selenium (Se), 0.0005 mg/L. All the detected concentrations in our water samples were well above these detection thresholds, confirming the analytical accuracy and supporting the conclusion that metal levels remained within permissible limits for irrigation and consumption.

Virgin olive oil extraction

Virgin olive oil (VOO) is primarily extracted through mechanical extraction process, which is semi-continuous process, with malaxation identified as the most variable and critical stage. Following harvest, the olives undergo cleaning, washing, and crushing. The mechanical crushing reduces the size of the olives and disrupts their cellular structure, facilitating the release of oil. The resulting olive paste was malaxed at 27 ± 1 °C for 30 min in a stainless-steel mixer under controlled atmosphere to minimize phenolic degradation. This stage is crucial for improving extraction efficiency by promoting the coalescence of oil droplets. After malaxation, the paste is processed in a decanter centrifuge, which separates the oil from the solid pomace and the aqueous phase. Subsequently, a vertical centrifuge to clarify the oil by removing residual water and fine solid particles53.

Analytical methods of olive oil

Acid, peroxide, saponification, and iodine values

The analytical characterization of olive oil included the determination of acid Value (mg KOH/g) and Acidity (%) were determined via titration with potassium hydroxide using standard protocols86. The Peroxide Value (mg O₂/kg), which indicates the presence of primary oxidation products, was assessed using iodine titration following Ponphai boon et al.87. The Saponification Value (mg KOH/kg) was measured using ethanolic potassium hydroxide88. Additionally, drying and refractive indices were measured using gravimetric and refractometric methods respectively89. The specific extinction K232 and K270, which are critical for evaluating oil quality and oxidation status, were evaluated using UV spectrophotometry. Iodine Value (g/100 g oil), an indicator of the degree of unsaturation in the oil, was calculated following the Wijs method90.

Physicochemical parameters

The physicochemical properties of olive oils were assessed through standard analytical methods. Moisture (%) and Dry Matter (%) were determined gravimetrically by oven-drying the sample at 105 °C until a constant weight was achieved91. Fat Content (%) was analyzed by Soxhlet extraction using petroleum ether as a solvent92. Ash content, was measured by incinerating the sample in a muffle furnace at 550 °C until a constant weight was achieved93.

Fatty acids composition

The fatty acid composition of olive oil was determined using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) on a Shimadzu GCMS-QP2020 NX system94,95. Lipids were first extracted and converted to fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) through transesterification using methanolic potassium hydroxide, a process that enhances volatility and improves separation efficiency. The FAMEs were then analyzed using a gas chromatograph equipped with a Supelco SP-2560 polar capillary column (100 m × 0.25 mm, 0.20 μm film thickness), which allows for effective resolution of individual fatty acids. A controlled temperature gradient was applied, starting at 140 °C, increasing to 220 °C at a rate of 4 °C/min, and holding for 10 min to optimize separation. Helium (99.999% purity) was used as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1 mL/min, facilitating efficient elution of compounds through the column.

Identification of fatty acids was performed by comparing the retention times and mass spectra of the sample components with those of certified FAME standards. Mass spectral detection was conducted in electron ionization (EI) mode at 70 eV, and the detector was operated in full scan mode (m/z 50–550) to ensure comprehensive compound identification. Quantification was achieved by integrating the peak areas of detected compounds and normalizing them to the total fatty acid content. C17:0 methyl ester was used as an internal standard to improve accuracy and account for any variations in derivatization or injection. The results were expressed as a percentage of total fatty acids, providing a comprehensive profile of olive oil composition. This method ensures precise fatty acid characterization, which is crucial for evaluating olive oil quality, authenticity, and compliance with regulatory standards96. Certified reference materials (FAME mix, Supelco 37 Component FAME Mix, Sigma-Aldrich) were used to calibrate the GC-MS instrument and validate fatty acid identification and quantification. These standards ensured accuracy in retention time matching and peak area integration. The instrument performance and reproducibility were monitored through routine injections of the CRM alongside olive oil samples.

Analysis of carotenoids, tocopherols, squalene, pheophytin, Lutein, and sterols in olive oil

Carotenoids, tocopherols, squalene, pheophytin, lutein, and sterols were simultaneously analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography with a diode-array detector (HPLC-DAD) based on the method described by Martakos et al.97. Separation was performed on a C18 reversed-phase column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm particle size) using a gradient elution program with methanol and acetonitrile as the mobile phase. Carotenoids, including lutein and β-carotene, were detected at 450 nm, while tocopherols (α-, β-, and γ-tocopherol) were monitored at 295 nm, and squalene was detected at 210 nm. Pheophytin was analyzed at 410 nm, and sterols were detected at 230 nm. A 20 µL sample was injected after dilution with 2-propanol and filtered through a 0.22 μm RC syringe filter. Quantification was carried out using calibration curves established with external standards (Sigma-Aldrich), and results were expressed in mg/kg. To validate HPLC-DAD quantification and compound identification, certified reference materials (Sigma-Aldrich) were used for α-tocopherol, β-carotene, lutein, squalene, and sterols. Calibration curves were constructed with these CRMs to ensure accuracy and linearity, and periodic CRM injections confirmed system stability and method robustness throughout the analysis.

Total polyphenol content, total flavonoids, antioxidant activity and lipid peroxidation

The total polyphenol content of olive oil was quantified using the Folin-Ciocalteu method, which is based on the reduction of the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent by phenolic compounds in an alkaline medium, producing a blue complex measurable at 760 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. The results were expressed in milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per kilogram (mg GAE/kg), with a calibration curve prepared using standard gallic acid solutions (0–200 mg/L)98,99. The total flavonoid content was determined using the aluminum chloride colorimetric assay, where flavonoids react with AlCl₃ in methanolic solution to form a stable complex, measured at 415 nm. The results were expressed in milligrams of quercetin equivalents per kilogram (mg QE/kg), with a calibration curve based on quercetin standard solutions (5–100 mg/L).

Antioxidant activity was evaluated using the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging assay, a widely used method for assessing free radical neutralization capacity. A methanolic DPPH solution (0.1 mM) was prepared, and olive oil extracts were mixed with the solution and incubated in the dark at 25 °C for 30 min100,101. The decrease in absorbance at 517 nm was measured, and antioxidant activity was expressed as the percentage of DPPH inhibition, calculated using the formula:

Where A517 blank represents the absorbance of the blank, and A517 sample represents the absorbance of the sample containing the extract.

Lipid peroxidation was assessed using the TBARS (thiobarbituric acid reactive substances) method, which quantifies malondialdehyde (MDA) equivalents formed during oxidative degradation of lipids. Oil extracts were mixed with a TBA solution (0.375% in 15% trichloroacetic acid, with 0.25 M HCl) and heated at 95 °C for 30 min to form a pink chromogenic complex. After cooling, absorbance was measured at 532 nm, and MDA concentration was calculated using an extinction coefficient of 155 mM−1 cm−1102.

Antibacterial activity

To extract the phenolic compounds from three distinct olive oil samples, each derived from olives irrigated differently (treated wastewater, normal water, and spring water), 1.5 g of each oil were combined with 1.5 milliliters of hexane and processed through C18 SPE cartridges. The polyphenols were then eluted using 3 milliliters of methanol, a step repeated twice to maximize recovery28. Antibacterial activity of olive oil polyphenols was evaluated using an adapted methodology based on protocols from Fratianni et al.103 and Tamariz-Angeles et al.104. The process involved the cultivation of pathogenic bacteria strains including Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923, Escherichia coli ATCC10536, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC27853. These bacteria were selected due to their relevance to food safety and public health, as they are common indicators of microbial contamination in food products. Then, these bacteria were grown in tryptic soy broth at 37 °C to achieve an OD600 of 0.08, followed by spreading onto Müller–Hinton agar plates. Olive oil polyphenol extracts, standardized at 5 µg, were then applied to the inoculated agar. After incubating the plates for 24 h at 37 °C, the zones of inhibition around the polyphenol extracts were precisely measured using a caliper105. The efficacy of these polyphenols was assessed in comparison to controls using sterile DMSO, highlighting their significant antibacterial properties against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted with triplicates per treatment, and data were analyzed using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The results are presented as mean ± standard deviation, and differences between treatments were evaluated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test at a significance level of p < 0.05. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality, and Levene’s test was applied to verify homogeneity of variance before performing ANOVA.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that irrigation water source significantly influences the physicochemical properties, fatty acid profile, antioxidant capacity, and bioactive compound content of olive oil. Among the water sources evaluated, treated wastewater exhibited distinct water quality characteristics, including higher organic load (COD and BOD₅), nutrient content (ammonium and nitrite), residual suspended solids, and increased conductivity and pH, reflecting the presence of organic material and ionic content post-treatment. Despite these variations, heavy metal concentrations in all water sources remained within permissible limits for irrigation and drinking purposes, affirming their safety for agricultural use. Treated wastewater irrigation consistently produced olive oil with superior quality attributes. Oils derived from treated wastewater-irrigated exhibited higher levels of bioactive compounds such as polyphenols, tocopherols, squalene, and sterols, which collectively enhanced oxidative stability, nutritional value, and health-promoting properties. These samples also showed improved fatty acid composition, with elevated levels of monounsaturated fatty acids like oleic acid, known for cardiovascular benefits. The treated wastewater-irrigated oil dis-played the highest antioxidant activity, as evidenced by DPPH radical scavenging and low TBARS values, reflecting strong resistance to oxidative degradation. Additionally, the favorable physicochemical properties, including lower moisture content and increased dry matter, further enhanced the oil’s stability and shelf life. These findings indicate that treated wastewater represents a viable and sustainable alternative for olive tree irrigation, contributing not only to water conservation efforts but also to the enrichment of olive oil with valuable nutritional and bioactive compounds. Specifically, irrigation with treated wastewater was associated with enhanced antioxidant activity and improved oxidative stability, which are key indicators of prolonged shelf life and product quality. In contrast, spring water irrigation resulted in olive oil with superior antibacterial properties, highlighting its potential in food safety and preservation contexts. Meanwhile, normal water irrigation supported a more balanced fatty acid profile, although the overall levels of bioactive compounds were comparatively lower. These differential outcomes underscore the influence of irrigation water source on the functional and compositional quality of olive oil and provide valuable insights for optimizing irrigation strategies in water-scarce regions. However, this study has certain limitations that should be acknowledged, Future research should incorporate advanced analytical techniques to detect trace contaminants such as pharmaceutical residues, pesticides, or microplastics and ensure food safety. Additionally, further multi-location studies are needed to confirm the findings across different agroecological conditions. Furthermore, future research should incorporate long-term monitoring to assess the cumulative effects of treated wastewater irrigation on soil health, tree productivity, and oil composition over multiple growing seasons.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article. Any other data can be available upon request from the corresponding author or first author.

References

Kiritsakis, A. et al. Olive oil and mediterranean diet: The importance of olive oil constituents, and mainly of its polyphenols. In Human Health—The redox system—Xenohormesis hypothesis 603–619 (Elsevier, 2024).

Campo, C., Gangemi, S., Pioggia, G. & Allegra, A. Beneficial effect of olive oil and its derivates: focus on hematological neoplasm. Life 14 (5), 583 (2024).

Jimenez-Lopez, C. et al. Bioactive compounds and quality of extra virgin olive oil. Foods 9 (8), 1014 (2020).

Cecchi, L., Migliorini, M. & Mulinacci, N. Virgin olive oil volatile compounds: composition, sensory characteristics, analytical approaches, quality control, and authentication. J. Agric. Food Chem. 69 (7), 2013–2040 (2021).

Gharby, S. Olive oil: extraction technology, chemical composition, and enrichment using natural additives. In Olive Cultivation (IntechOpen, 2022).

Hashem, M. S. & Qi, X. Treated wastewater irrigation—A review. Water 13 (11), 1527 (2021).

Ofori, S., Puškáčová, A., Růžičková, I. & Wanner, J. Treated wastewater reuse for irrigation: pros and cons. Sci. Total Environ. 760, 144026 (2021).

Kesari, K. K. et al. Wastewater treatment and reuse: a review of its applications and health implications. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 232, 1–28 (2021).

Fdil, J. et al. Effect of alternating well water with treated wastewater irrigation on soil and Koroneiki olive trees. Water 15 (16), 2988 (2023).

Singh, A. A review of wastewater irrigation: environmental implications. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 168, 105454 (2021).

Kaur, J., Kaur, V., Pakade, Y. B. & Katnoria, J. K. A study on water quality monitoring of Buddha Nullah, Ludhiana, Punjab (India). Environ. Geochem. Health 43, 2699–2722 (2021).

Badr, A. M., Abdelradi, F., Negm, A. & Ramadan, E. M. Mitigating water shortage via hydrological modeling in old and new cultivated lands West of the nile in Egypt. Water 15 (14), 2668 (2023).

Sela, S. K., Nayab-Ul-Hossain, A. K. M., Hussain, S. Z. & Hasan, N. Utilization of Prawn to reduce the value of BOD and COD of textile wastewater. Clean. Eng. Technol. 1, 100021 (2020).

Wei, G. et al. BOD/COD ratio as a probing index in the O/H/O process for coking wastewater treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 466, 143257 (2023).

Skoczko, I., Struk-Sokołowska, J. & Ofman, P. Seasonal changes in nitrogen, phosphorus, BOD and COD removal in bystre wastewater treatment plant. J. Ecol. Eng. 18 (4), 185–191 (2017).

Ma, W. L. et al. Concentrations and fate of Parabens and their metabolites in two typical wastewater treatment plants in Northeastern China. Sci. Total Environ. 644, 754–761 (2018).

Taziki, M., Ahmadzadeh, H., Murry, M. A. & Lyon, S. R. Nitrate and nitrite removal from wastewater using algae. Curr. Biotechnol. 4 (4), 426–440 (2015).

Noureddine, B. Assessing the impact of treated wastewater irrigation on citrus fruit quality: nutritional, heavy metal, and phytochemical analyses. Tob. Regul. Sci. 1466–1474 (2023).

Li, D., Zou, M. & Jiang, L. Dissolved oxygen control strategies for water treatment: a review. Water Sci. Technol. 86 (6), 1444–1466 (2022).

Zhao, G. et al. Treated wastewater and weak removal mechanisms enhance nitrate pollution in metropolitan rivers. Environ. Res. 231, 116182 (2023).

Hyánková, E. et al. Irrigation with treated wastewater as an alternative nutrient source (for crop): numerical simulation. 11 (10), 946 (2021).

Wei, X. et al. Comparative performance of three machine learning models in predicting influent flow rates and nutrient loads at wastewater treatment plants. ACS ES&T Water 4 (3), 1024–1035 (2023).

Mizuhata, M. Electrical conductivity measurement of electrolyte solution. Electrochemistry 90 (10), 102011 (2022).

Kodera, H. et al. Phosphate recovery as concentrated solution from treated wastewater by a PAO-enriched biofilm reactor. Water Res. 47 (6), 2025–2032 (2013).

Ye, S. et al. Co-occurrence and interactions of pollutants, and their impacts on soil remediation—A review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47 (16), 1528–1553 (2017).

Lone, S. A., Jeelani, G. & Mukherjee, A. Elevated fluoride levels in groundwater in the Himalayan aquifers of upper indus basin, India: sources, processes and health risk. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 25, 101096 (2024).

Hussain, N., Ahmed, M. & Hussain, S. M. Potential health risks assessment cognate with selected heavy metals contents in some vegetables grown with four different irrigation sources near Lahore, Pakistan. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 29 (3), 1813–1824 (2022).

Agoro, M. A., Adeniji, A. O., Adefisoye, M. A. & Okoh, O. O. Heavy metals in wastewater and sewage sludge from selected municipal treatment plants in Eastern cape Province, South Africa. Water 12 (10), 2746 (2020).

Shrestha, R. et al. Technological trends in heavy metals removal from industrial wastewater: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9 (4), 105688 (2021).

Laskar, N. Statistical analysis and water quality modeling towards holistic health assessment of Himalayan and Peninsular rivers of India. Environ. Challenges 15, 100917 (2024).

Sarkar, D. J. et al. Occurrence, fate and removal of microplastics as heavy metal vector in natural wastewater treatment wetland system. Water Res. 192, 116853 (2021).

Balesteros, M. R. et al. Determination of olive oil acidity by CE. Electrophoresis 28 (20), 3731–3736 (2007).

Grossi, M. & Riccò, B. Oil concentration measurement in metalworking fluids by optical spectroscopy. P-ESEM 13 (2014).

Al-Shdiefat, S., Ayoub, S. & Jamjoum, K. Effect of irrigation with reclaimed wastewater on soil properties and olive oil quality. Jordan J. Agric. Sci. 5, 2 (2009).

Conde-Innamorato, P. et al. The impact of irrigation on Olive fruit yield and oil quality in a humid climate. Agronomy 12 (2), 313 (2022).

Bedbabis, S. et al. Long-terms effects of irrigation with treated municipal wastewater on soil, yield and olive oil quality. Agric. Water Manag. 160, 14–21 (2015).