Abstract

The brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus plays a significant role in transmitting pathogens to humans and animals, necessitating control measures. Given the drawbacks of synthetic chemicals, plant-based alternatives are a promising option for tick management. The present study aimed to evaluate the acaricidal potential of thyme oil (TO) and nano-formulations {thyme oil nano-emulsion (TNE), silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), and thyme nano-emulsion containing silver nanoparticles (TNE- AgNPs)} against R. sanguineus using an adult immersion bioassay. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) was used for TO analysis. The UV- visible spectroscopy, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and particle size were used to characterize the nano-formulations. In addition, the freshly dead ticks were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The GC-MS analysis indicated that Thymol (34.08%) was the main oil component, followed by γ-Terpinene (32.99%). The TEM images revealed a spherical-shaped nano droplet with a size of ≤ 100 nm for all nanoformulations. The droplet size and polydispersity index were (445.9 & 0.325), (10.59 & 0.216), and (768.2 & 0.325) for TNE, AgNPs, and TNE-AgNPs, respectively. The calculated LC50 values after 7 days were 11.62, 5.47, 4.08, and 2.38% for TO, TNE, AgNPs, and TNE- AgNPs, respectively. The SEM examination revealed changes in the sensilla base, spiracular plate and anal groove region of the treated ticks. Although the biological parameters of the engorged females did not differ significantly between the treatment and control groups, there was a decrease in the hatchability percent of TO (67%), TNE (65%), and TNE-AgNPs (71%) compared to the control (80%). The used materials demonstrated acaricidal activity and might be candidates for managing the dog tick, R. sanguineus. Further detailed studies are needed to enable good judgment of the use of these materials to control R. sanguineus tick.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ticks and tick-borne pathogens (TBP) pose a significant threat to the livestock industry, causing significant economic losses due to blood loss, disease transmission, and the costs associated with treatment and control measures1. Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Acari: Ixodidae) are widely distributed geographically and are known to transmit Rickettsia conorii, the etiological agent of Boutonneuse Fever in the Mediterranean region2,3. In the USA, it has been linked to the transmission of Rickettsia rickettsii, causing Rocky Mountain spotted fever4. In Egypt, the prevalence rate of tick-borne pathogens among dogs was 23.56%, comprising Ehrlichia and Anaplasma (Anaplasmataceae) at 11.1% and Babesia canis (Piroplasmida; Babesiidae) at 8.2%, which were probably transmitted by R. sanguineus5,6.

The long-standing reliance on synthetic acaricides for tick control has led to challenges such as resistance, environmental contamination, and toxicity concerns. For instance, R. sanguineus has shown resistance to multiple acaricide classes, including amidines, pyrethroids, macrocyclic lactones, and phenylpyrazoles7,8,9,10. In response, research is increasingly focused on developing a more sustainable and safer option. Plant-based products offer a valuable alternative for tick control. Indeed, various plants and their derivatives have shown acaricidal effects against different tick species, including Ixodes scapularis, Rhipicephalus microplus, and Rhipicephalus annulatus11,12,13,14. Essential oils, in particular, exhibit a range of activities, including repellent, antifeeding, chemosterilant, and biocidal effects, making them promising candidates for tick management13,15,16,17. With minimal impact on non-target organisms, essential oils are attractive options. These complex mixtures typically contain 20–60 components at varying concentrations18. The multi-target action of essential oils’ active compounds may delay resistance development, providing a sustainable solution for tick control19.

Thymus vulgaris, commonly known as thyme, is an aromatic plant primarily used for flavoring, culinary, and medicinal purposes20. It is often extracted as essential oil (EO), and the promising biological activity of thyme EO, including antimicrobial and antioxidant activity, has been demonstrated21,22. Thyme EO has also been found to be effective against insect pests23 and ticks, including R. sanguineus24. Thymol, the primary component of thyme EO, has shown acaricidal activity against various tick species, including Ixodes ricinus25, R. sanguineus, R. microplus, and R. annulatus26,27,28,29.

Despite the enormous potential of application of thyme EO, several limitations limit the use of plant EOs in pest management, including poor water solubility, high volatility, and rapid degradation30,31. Therefore, the development of stable and effective acaricide formulations is necessary. Nanotechnology, including nano-emulsion and nano-encapsulation, is a promising approach for improving the properties of plant EOs30,31. Several studies have reported the acaricidal activity of nano-emulsions against R. microplus larvae32 and R. microplus females33,34. In addition, Marimuthu et al.35 tested the biosynthesized silver nanoparticles from Mimosa pudica Gaertn leaf extract against the larvae of R. microplus. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) synthesized by subjecting myrrh and ginger extracts to laser ablation have been shown to exert potent toxic effects on Hyalomma dromedarii ticks, impacting both adult and immature stages36. Studies have demonstrated that AgNPs can cause significant mortality through mechanisms involving oxidative stress, membrane disruption, and interference with key physiological processes in ticks37. In addition to direct lethality, AgNPs can negatively affect reproductive parameters such as egg laying and hatchability, where38 reported that green-synthesized silver nanoparticles using Andrographis paniculata extract significantly reduced the survival rate of R. microplus ticks and inhibited oviposition in treated females.

The present study aimed to evaluate the acaricidal activity of thyme EO and its nano-formulations against R. sanguineus. While a prior study has examined the acaricidal activity of thyme EO and its nano–formulation against R. sanguineus24, our study expands on this knowledge by providing a comprehensive and in-depth evaluation of their acaricidal activity, including morpho-histological changes.

Materials and methods

Ticks

Fully fed female R. sanguineus specimens (N = 100) were obtained from a well-established colony at Cairo University’s Department of Parasitology of Veterinary Medicine, located in Giza, Egypt. These females were placed in a plastic cup for oviposition which lasted 10 days and maintained in an incubator at 25 °C ± 1 °C and 75%–80% relative humidity. After 16 days of incubation, eggs hatched into larvae. Hungry larvae were fed on healthy rabbits using the capsule technique one week later39,40,41. The detached, fully engorged larvae were collected and incubated for one week under the same conditions to molt into nymphs. Hungry nymphs were reared on healthy rabbits to obtain fully engorged nymphs that were incubated for two weeks to molt into unfed adults. In male ticks, the dorsal shield (scutum) covers most of the body, whereas in female ticks, it only covers a portion of the body41.

Source of oil and GC–MS analysis

Thyme oil (TO) was purchased from Ab Chem Company (https://www.abchem.org). Thyme oil analysis was conducted using gas chromatography mass spectrometry (Agilent 8890 GC System, Santa Clara, California), which was joined to an Agilent 5977B GC/MSD mass spectrometer and equipped with an HP-5MS fused silica capillary column (Santa Clara, California, USA) (30 m, 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 mm film thickness). At first, the temperature was maintained at 50 °C. After that, it automatically climbed by 5 °C/min to 200 °C and fell by 10 °C/min to 280 °C. At last, it was kept for seven minutes at 280 °C. Helium was used as the carrier gas, and its flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. 1 µL of the dissolved essential oil (20 µL essential oil / mL diethyl ether) was inoculated into the gas chromatograph with a split ratio of 1:50. The temperature of the injection. 230 °C was the injection temperature. In the electron impact mode (EI), mass spectra were achieved at 70 eV, covering a range of 39 to 500 amu in m/z. Data from the mass spectra database (National Institute of Standards and Technology, NIST) were compared with the isolated peaks41.

Preparation of thyme oil nano-emulsion (TNE)

A low-energy method was used for the preparation of emulsion according to Sugumar et al.42, nano-emulsions were formed with little modification. The oil-in-water nano-emulsion was formed using thyme oil, non-ionic surfactant (Tween 80, MP Biomedicals, United States), and distilled water. In all formulations, the oil concentration (20% v/v) was fixed as a stock solution. The ratio of non-ionic surfactant (Tween 80) to oil was (1:1) at room temperature. After that, the mixture was homogenized, and then the distilled water was added intermittently during stirring using a magnetic stirrer at a high speed of 2000 rpm for 3 h. Finally, the obtained nano-emulsion was left under stirring overnight.

Preparation of thyme nano-emulsion containing silver nanoparticles (TNE- AgNPs)

Silver nanoparticles were purchased from the Nano Gate Company (https://nanogate-eg.com/en). Thyme nanoemulsion mixed with silver nanoparticles (TNE-AgNPs) was prepared by adding 5% AgNPs to 20% thyme nanoemulsion. The AgNPs were synthesized by introducing 0.1 mM AgNO3 to 10 mL of water, adjusting the pH to 10, and heating the solution for 60 min while stirring until it turned dark yellowish-brown. Equal amounts of the AgNPs solution were then combined with the thyme nanoemulsion to produce TNE-AgNPs.

Characterization of prepared nano-formulations

UV-visible spectroscopy

The characterization of TNE and TNE - AgNPs was performed by spectrophotometric analysis (T80 UV/VIS Spectrometer) through a scanning wavelength range of 200–900 nm. The UV–Vis spectral determination gives insight into the actual formation of the nano-formulations by surface plasmon resonance effect43.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The transmission electron microscope was used to measure the sample droplet size. A few drops of the sample and 1% phosphotungstic acid were placed on a carbon-coated copper grid and allowed to dry after the suspension of the materials was sonicated for 20 min on an ultrasonicator (Crest Ultrasonics Corp., New Jersey, USA). Next, the sample-loaded grid was subjected to an examination by a 200 kv HR-TEM (JEOL, JEM-2100, Tokyo, Japan)42,43.

Particle size

Using the dynamic light scattering (DLS) method and a Malvern Zetasizer 3000 HAS (Malvern Instruments, Ltd., UK), the particle size distribution was analyzed at the following conditions: temperature of 23 °C, run time of 2 min, solvent of water, and concentration of 1 mg/ml43.

Tick bioassay using unfed adult immersion test (AIT)

Unfed adult ticks were immersed at different concentrations of TO (40, 30, 20, 10, 5%), TNE (30, 20, 10, 5, 2.5%), AgNPs, and TNE - Ag NPs (5, 4, 3, 2, 1%), which were chosen according to pilot studies. A total of 96 replicates were distributed as three replicates per treatment/tested material (10 ticks/ replicate, five males and five females) of unfed adults were used for each concentration, and the immersion time was 5 min in 2 ml/concentration. Furthermore, unfed adults were immersed in the following solutions: 5% Tween 80 as solvent control (control with Tween), Butox® 5.0 (Deltamethrin) 1 ml/L as a recommended concentration of acaricidal reference (10 µl Butox® 5.0 diluted in 10 ml water), and distilled water only as negative control (control without Tween). Treated ticks were incubated in glass tubes at 25 °C ± 1 °C and 75%–80% relative humidity. Mortality rates were assessed over seven consecutive days to capture any delayed effects, with ticks considered dead if they failed to respond to exhalation-induced stimulation42,43.

Scanning electron microscopy for tick specimens

The five unfed adult tick specimens (3 females and 2 males) treated with 40% TO, 30% TNE, 5% AgNPs, and 5% TNE-AgNPs for 5–7 days, as well as control ticks treated with distilled water were well cleaned by immersion in water–glycerol– potassium chloride (KCl) solution overnight44,45. The ticks were then washed in distilled water several times, followed by immersion in a series of ethanol concentrations: 25%, 50%, 70%, and 80% for 1 h each, and then 90% and 100% ethanol for 10 min each46. Ethanol dehydration was employed to preserve tick samples, as it effectively replaces water without inducing structural collapse or distortion, thereby maintaining morphology for high-quality scanning electron microscopy imaging. Ticks were then adhered to the SEM stub by their dorsal and ventral surfaces, and liquid carbon dioxide was used to dry them in a drier (Blazer Union, F1-9496 Blazer/Furstentum Liechtenstein). A S15OA Sputter Coater was used to apply gold coating to ticks that were fixed on SEM stubs (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, California, United States). The SEM investigation of the coated samples was performed at the National Research Centre using SEM (Quanta FEG 250).

Effect of 50% lethal concentration (LC50) on the reproductive performance of tick females

This experiment aimed to examine the impact of TO, TNE, AgNPs, and TNE-AgNPs on the progeny of unfed adult ticks that survived exposure to LC50 concentrations and later fed on rabbits. The unfed adult of R. sanguineus ticks (20 males and 20 females/conc) were immersed for five minutes at concentrations of the calculated LC50 after 7 days (11.62, 5.47, 4.08, and 2.38%) for TO, TNE, AgNPs, and TNE - AgNPs, respectively. After 24 h, surviving ticks were reared on rabbits using the capsule technique (3 rabbits /conc) to follow the reproductive performance of tick females. Following engorgement, reproductive parameters were calculated for engorged females, including pre-oviposition weight, egg mass weight, egg production index (EPI), oviposition duration, egg incubation period, and hatchability percentage, as per established methods Abo Talep et al.39. The oviposition period was determined by the average time from starting to end laying eggs. The incubation period of eggs was estimated by the average time from start laying eggs to start hatching larvae. The egg productive index (EPI) and hatchability of the laid eggs were calculated as follows: EPI = egg mass weight (mg)/initial weight of engorged females (mg)47. Percentage of hatchability = Number of hatched larvae/number of laid eggs × 10048. Tick eggs were counted before hatching by weighing the egg mass per female, taking a portion, weighing it, and counting it. The total number of eggs per egg mass was then calculated. Larvae were counted for each female after hatching was complete in the untreated group.

Statistical analysis

The percent mortality of unfed adults treated with TO, TNE, Ag NPs, and TNE – AgNPs was statistically analyzed by a one-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s test.

using SPSS program version 20. By using regression equation analysis on the probit-transformed mortality data, 50% lethal concentration (LC50) values were determined using Ehab software. The probit approach was used to examine the dose-response data49.

Results

Gas chromatography – mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis

Ten components were identified in thyme oil using the GC-MS library (Table 1). The analysis indicated that Thymol (34.08%) was the main oil component and followed by γ-Terpinene (32.99%).

Characterization of prepared nano-formulations

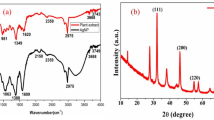

UV-visible spectroscopy

The absorption peak maxima of TNE were observed at 220 nm. In contrast the absorption peak maxima of TNE- AgNPs showed at 225 nm. (Fig. S1).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The results of TEM indicated that TNE droplets, AgNPs, and TNE-AgNPs appeared spherical without aggregations, and the size within the range of nanoparticles (≤ 100 nm) where the size ranged from (10–48), (11–14.7 nm), and (10.44–49.55), respectively (Fig. 1).

Particle size

The particle size for TNE, AgNPs, and TNE-AgNPs were 445.9, 10.59, and 768.2 nm, with a correspondingly low PDI of 0.325, 0.216, and 0.320, respectively (Table 2 and Fig. S2).

Acaricidal effect of TO, TNE, ag NPs, and TNE-Ag NPs

The efficacy of thyme oil (TO) and its nano-formulation (TNE) against unfed R. sanguineus adults is presented in Tables 3 and 4. Mortality rates increased with both time and concentration. At 40%, TO achieved 93% mortality on day 7, while TNE reached 100% mortality on day 6. Even at the lowest concentration (5%), TO induced mortality on day 5, whereas TNE showed effects at 2.5% on day 3. These findings indicate TNE’s slightly superior efficacy. Notably, both TO and TNE showed no significant difference in effectiveness compared to the acaricide Butox at the highest concentration (P ≥ 0.05).

Concerning AgNPs and TNE-AgNPs, the mortalities on the 7th day were 80% and 96.6% at the highest concentration of 5%, respectively. At the concentration of 1% AgNPs recorded no mortality while TNE-AgNPs recorded 13.3% mortality. No significant difference (P ≥ 0.05) was presented between TNE-Ag NPs and Butox® (Table 5). While there was significance between AgNPs and Butox® at the highest concentration (Table 6). There were no mortalities recorded in the controls. The calculated LC50 value after 7 days was 11.62, 5.47, 4.08, and 2.38 for TO, TNE, AgNPs, and TNE-Ag NPs, respectively (Table 7). From the calculated LC50, TNE-AgNPs were more toxic against unfed adults of R. sanguineus, followed by AgNPs, TNE, and TO.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

There were irregular spots on the sensilla base of the all treated ticks while the control group was smooth and integrated in the socket (Fig. 2). In comparing with control, there were changes observed in the spiracular plate of all treated groups in which some aeropyles were obstructed by secretions however the aeropyles of control group were clear and distinct (Fig. 3). The anal groove region showed cuticular disorders and filled with irregular spots (Fig. 4).

Scanning electron microscopy of sensile and the sensile socket of unfed adult males R. sanguineus with different treatments. (A) Untreated Control, (B) Butox®, (C) thyme oil (TO), (D) thyme nano-emulsion (TNE), (E) thyme nano-emulsion containing silver nanoparticles (TNE-AgNPs), ss (sensile), st (sensile socket).

Scanning electron microscopy of the spiracular plate of unfed adult males R. sanguineus with different treatments. (A) Untreated Control, (B) Butox®, (C) thyme oil (TO), (D) thyme nano-emulsion (TNE), (E) thyme nano-emulsion containing silver nanoparticles (TNE-AgNPs), SP (spiracular plate), ap (aeropyle).

Effect of lethal concentration of 50% ticks (LC50) on the reproductive performance of tick females

The biological parameters of engorged females, including female weight, egg weight and number, reproductive index (REPI), oviposition, incubation periods, and hatching percent, are shown in Table 8. Engorged female weights weren’t significantly different across treatments (0.18–0.22 g). However, egg mass weights (0.07–0.12 g), REPI (0.39–0.55), and egg numbers varied significantly (TO: 1552 eggs, AgNPs: 1641 eggs, TNE: 1915 eggs, Control: 2019 eggs, TNE-AgNPs: 2533 eggs). Oviposition period was similar (14.69–15.29 days). TO-exposed ticks had shorter incubation period (18.8 days) vs. other treatments (19.27-20 days).There was a decrease in the hatchability percent of TO (67%), TNE (65%), and TNE-AgNPs (71%) than the control (80%).

Discussion

The growing resistance of ticks to synthetic acaricides poses significant challenges to effective tick management, highlighting the urgent need for alternative management strategies50. In this study, the acaricidal activity of TO and its nanoformulations was investigated against R. sanguineus, and the morphological changes in the treated tick were elucidated.

The GC-MS analysis of TO revealed that Thymol was the major constituent, followed by γ-Terpinene. This result is consistent with Alibeigi et al.24, who identified Thymol (38.37%) and γ-Terpinene (15.09%) as the major components. On the other hand, the study of de Oliveira et al.51 revealed Thymol (40%), p-cymene (19.2%), and γ-terpinene (17.3%) as the most active constituents. The difference in the percentage of each component may be attributed to physiological and environmental conditions, genetic species, harvesting time, geographical location, and extraction methods52,53.

The characteristics of the prepared nanoformulations revealed spherical particles within the nanoscale range (≤ 100 nm), consistent with the fact that efficient nano-droplet sizes range from 20 to 200 nm54. Moreover, the low PDI values (0.2 to 0.3) suggest overall stability and homogeneity of the nanoformulations.

The current study demonstrated that TO and its nano-formulated derivatives had acaricidal activity against R. sanguineus. However, the observed acaricidal activity varied based on the treatment type and exposure period. Moreover, we observed that TNE-AgNPs, followed by AgNPs, and TNE had higher acaricidal activity against the unfed adult ticks than TO, as indicated by their LC50 values. These findings are similar to a previous study, which found that T. vulgaris nano EO had higher acaricidal activity (LC50 = 0.09%) against R. sanguineus compared to T. vulgaris EO (LC50 = 0.69%)24. Besides, enhanced biological activity of plant EOs when prepared and tested as nanoformulations has also been reported for other arthropod pests. For instance, it was reported that Schinus terebinthifolius nanoemulsion demonstrated enhanced larvicidal (LC50 = 6.8 µl L-1) and adulticidal (LC50 = 5.3 µl L-1) activity against Culex pipiens compared to the crude EO, which had LC50 values of 11.3 and 9.1 µl L-1, respectively55. The distinct physical and morphological characteristics of the nanoformulations may have influenced their acaricidal activity against the tick. Indeed, the 5 subcellular size and high specific surface area of nanopesticides (nanoemulsions) enhance their affinity for targeted biological system, improving their spread, bio-membrane permeability, and uptake, thereby enhancing their biological activities55,56,57. While the inherent properties of the nanoformulations may have enhanced their acaricidal activity against R. sanguineus, plant EOs are a complex mixture of volatile compounds, which derive their biological activity from these chemical constituents. Thymol found in the TO composition has been reported to have larvicidal activity (0.67–2.12 mg/mL) against R. microplus populations from different regions of Brazil58. It was also found to have larvicidal activity (LC50 = 6.4 mg/mL) against R. sanguineus24. Moreover, thymol exhibited adulticidal activity (LC50 = 1183.9 mg/L) against the carmine spider mites, Tetranychus cinnabarinus [Wu et al., 2017]. Furthermore, thymol in combination with other active compounds of TO has been shown to produce synergistic acaricidal activity against T. cinnabarinus59. Therefore, it is also possible that the enhanced acaricidal activity of the nanoformulations against R. sanguineus may be due to the way the bioactive compounds of TO interact with the carrier in the nanoformulation, resulting in their synergistic interactions or improved bioavailability, stability/solubility, and controlled release60.

Although the biological parameters of the engorged females did not differ significantly between the treatment and control groups, we found reduced hatchability of R. sanguineus eggs after treatment with TO, TNE, and TNE-AgNPs. A similar effect on the hatchability of ticks after treatment with plant-based acaricides has been reported elsewhere61.

SEM was used to determine if the effect of the tested materials against the ticks was related to potential structural changes. SEM analysis in this study showed irregular spots on the sensilla bases of all treated ticks; some aeropyles were blocked by secretions, and the anal groove region displayed cuticular disorders filled with irregular spots. These observations align with Agwunobi et al.62, where SEM images of EO-treated ticks revealed a disjointed sensilla base from the sockets, cuticular cracks, and blocked aeropyles. Additionally, the extract from Eupatorium adenophorum damaged the cuticular and antennal sensilla of mustard aphids Lipathis erysimi63, causing the sensilla base to detach from its socket. In general, arthropod sensilla are responsible for olfaction, which is vital for feeding behavior and response to environmental stimuli. The sensory function of cuticular sensilla is essential for the survival and normal physiology of ticks. Based on this, the ultrastructural changes observed in the cuticular sensilla of R. sanguineus adults suggest that the tested materials may induce severe morphophysiological disturbances, potentially leading to tick mortality. Previous reports have documented the blockage of spiracular aeropyles by liquid-like secretions, and cuticular alterations64. One possible reason is that the hydrophobic properties of EO disrupt the cuticular wax layer and block the spiracles of the parasite, causing mortality through desiccation or suffocation64.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated the potential of T. vulgaris essential oil and its nano-formulations as acaricidal agents against unfed adults of R. sanguineus. Additionally, these findings extend current knowledge by demonstrating morpho-histological changes and suggesting that nano-biotechnology can enhance the performance of botanical acaricides. However, the in vitro design may not fully replicate field conditions, and the high concentrations required for adult mortality may limit large-scale application. Although mortality increased over time, which may be critical for long-term effect, the delayed effect may limit their suitability in situations where rapid action is critical for tick and tick-borne disease management. Further studies are essential to evaluate safety, and environmental impact under practical conditions.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are either included in this published (or available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request).

References

Henrioud, A. N. Towards sustainable parasite control practices in livestock production with emphasis in Latin America. Vet. Parasitol. 180 (1–2), 2–11 (2011).

Sousa, R. & Bacellar, F. Morbi-mortalidade Por Rickettsia Conorii Em Portugal. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet. 13, 180–184 (2004).

Matsumoto, K., Brouqui, P., Raoult, D. & Parola, P. Experimental infection models of ticks of the Rhipicephalus sanguineus group with Rickettsia Conorii. Vector Borne Zoon Dis. 5 (4), 363–372 (2005).

Demma, L. J. et al. Rocky mountain spotted fever from an unexpected tick vector in Arizona. N Engl. J. Med. 353 (6), 587–594 (2005).

Hegab, A. A. et al. Screening and phylogenetic characterization of tick-borne pathogens in a population of dogs and associated ticks in Egypt. Parasit. Vectors. 15 (1), 222 (2022).

Hegab, A. A. et al. Occurrence and genotyping of Theileria equi in dogs and associated ticks in Egypt. Med. Vet. Entomol. 37 (2), 252–262 (2023).

Eiden, A. L., Kaufman, P. E., Oi, F. M., Allan, S. A. & Miller, R. J. Detection of permethrin resistance and fipronil tolerance in Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Acari: Ixodidae) in the united States. J. Med. Entomol. 52 (3), 429–436 (2015).

Rodriguez-Vivas, R. I., Ojeda-Chi, M. M. & Trinidad-Martinez, I. & De León, A. P. First documentation of ivermectin resistance in Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato (Acari: Ixodidae). Vet. Parasitol 233, 9–13 (2017).

Rodriguez-Vivas, R. I., Ojeda‐Chi, M. M., Trinidad‐Martinez, I. & Bolio‐González, M. E. First report of Amitraz and Cypermethrin resistance in Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu Lato infesting dogs in M Exico. Med. Vet. Entomol. 31 (1), 72–77 (2017).

Becker, S. et al. Resistance to deltamethrin, fipronil and Ivermectin in the brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu stricto, Latreille (Acari: Ixodidae). Tick. Borne Dis. 10 (5), 1046–1050 (2019).

Borges, L. M. F., Ferri, P. H., Silva, W. J., Silva, W. C. & Silva, J. G. In vitro efficacy of extracts of Melia Azedarach against the tick Boophilus Microplus. Med. Vet. Entomol. 17 (2), 228–231 (2003).

Abdel-Shafy, S. & Soliman, M. M. M. Toxicity of some essential oils on eggs, larvae and females of Boophilus annulatus (Acari: ixodida: Amblyommidae) infesting cattle in Egypt. Acarologia 44 (1–2), 23–30 (2004).

Dietrich, G. et al. Repellent activity of fractioned compounds from Chamaecyparis nootkatensis essential oil against nymphal Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae). Med. Vet. Entomol. 43 (5), 957–961 (2006).

Ribeiro, V. L. S., Toigo, E., Bordignon, S. A., Gonçalves, K. & von Poser, G. Acaricidal properties of extracts from the aerial parts of Hypericum polyanthemum on the cattle tick Boophilus Microplus. Vet. Parasitol. 147 (1–2), 199–203 (2007).

Facey, P. C., Porter, R. B., Reese, P. B. & Williams, L. A. Biological activity and chemical composition of the essential oil from Jamaican Hyptis verticillata Jacq. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53 (12), 4774–4777 (2005).

Panella, N. A. et al. Use of novel compounds for pest control: insecticidal and acaricidal activity of essential oil components from Heartwood of Alaska yellow Cedar. Med. Vet. Entomol. 42 (3), 352–358 (2005).

Tunón, H., Thorsell, W., Mikiver, A. & Malander, I. Arthropod repellency, especially tick (Ixodes ricinus), exerted by extract from Artemisia abrotanum and essential oil from flowers of Dianthus Caryophyllum. Fitoterapia 77 (4), 257–261 (2006).

Bakkali, F., Averbeck, S., Averbeck, D. & Idaomar, M. Biological effects of essential oils–a review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 46 (2), 446–475 (2008).

Wang, L., Li, X., Zhang, G., Dong, J. & Eastoe, J. Oil-in-water nanoemulsions for pesticide formulations. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 314 (1), 230–235 (2007).

Halat, D. H., Krayem, M., Khaled, S. & Younes, S. A focused insight into thyme: Biological, Chemical, and therapeutic properties of an Indigenous mediterranean herb. Nutrients 14 (10) (2022).

Galovičová, L. et al. Thymus vulgaris essential oil and its biological activity. Plants 10 (9) (2021).

Chahboun, N. et al. Chemical composition, biological activities, and anti-corrosion performance of Moroccan essential oil Thymus vulgaris from the Oued amlil region, Taza. Int. J. Electro chem. Sci. 19 (12), 100859 (2024).

Pavela, R. & Sedlák, P. Post-application temperature as a factor influencing the insecticidal activity of essential oil from Thymus vulgaris. Ind. Crop Prod. 113, 46–49 (2018).

Alibeigi, Z., Rakhshandehroo, E., Saharkhiz, M. J. & Alavi, A. M. The acaricidal and repellent activity of the essential and nano essential oil of Thymus vulgaris against the larval and engorged adult stages of the brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Acari: Ixodidae). BMC Vet. Res. 21, 135 (2025).

Tabari, M. A., Youssefi, M. R., Maggi, F. & Benelli, G. Toxic and repellent activity of selected monoterpenoids (thymol, carvacrol and linalool) against the castor bean tick, Ixodes ricinus (Acari: Ixodidae). Vet. Parasitol. 245, 86–91 (2017).

Coelho, L. et al. Combination of thymol and Eugenol for the control of Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato: evaluation of synergism on immature stages and formulation development. Vet. Parasitol. 277, 108989 (2020).

Matos, R. S. et al. Determination of the susceptibility of unengorged larvae and engorged females of Rhipicephalus microplus (Acari: Ixodidae) to different methods of dissolving thymol. Parasitol. Res. 108, 1541–1549 (2014).

Costa-Júnior, L. M., Miller, R. J., Alves, P. B., Blank, A. F. & Li, A. Y. León, A. A. P. Acaricidal efficacies of Lippia gracilis essential oil and its phytochemicals against organophosphate-resistant and susceptible strains of Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) Microplus. Vet. Parasitol. 228, 60–64 (2016). de.

Arafa, W. M., Aboelhadid, S. M., Moawad, A., Shokeir, K. M. & Ahmed, O. Toxicity, repellency and anti-cholinesterase activities of thymol-eucalyptus combinations against phenotypically resistant Rhipicephalus annulatus ticks. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 81, 265–277 (2020).

Campolo, O., Giunti, G., Laigle, M., Michel, T. & Palmeri, V. Essential oil-based nano-emulsions: effect of different surfactants, sonication and plant species on physicochemical characteristics. Ind. Crop Prod. 157, 112935 (2020).

Modafferi, A. et al. Bioactivity of Allium sativum essential oil-based nano-emulsion against Planococcus citri and its predator Cryptolaemus Montrouzieri. Ind. Crop Prod. 208, 117837 (2024).

Nogueira, J. A. et al. Repellency effect of Pilocarpus spicatus A. St.-Hil essential oil and nanoemulsion against Rhipicephalus Microplus larvae. Exp. Parasitol. 215, 107919 (2020).

Dos Santos, D. S. et al. Nanostructured cinnamon oil has the potential to control Rhipicephalus Microplus ticks on cattle. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 73, 129–138 (2017).

Baldissera, M. D., Stefani, L. M. & Da Silva, A. S. Effects of essential oil of Eucalyptus globulus loaded in nanoemulsions and in nanocapsules on reproduction of cattle tick (Rhipicephalus microplus). Arc De Zootec. 67, 494–498 (2018).

Marimuthu, S. et al. Evaluation of green synthesized silver nanoparticles against parasites. Parasitol. Res. 108, 1541–1549 (2011).

Nabil, M. et al. Acaricidal efficacy of silver nanoformulations of Commiphora molmol and Zingiber officinale against the camel Tick, Hyalomma dromedarii (Ixodida: Ixodidae). Inorg. Chem. Commun. 147, 110229 (2023).

Majeed, Q. A. H. et al. Acaricidal, larvacidal, and repellent activity of green synthesized silver nanoparticles against Hyalomma dromedarii. Trop. Biomed. 40 (3), 356–362 (2023).

Kumar, B., Smita, K., Cumbal, L. & Debut, A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Andrographis paniculata and their acaricidal activity against Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) Microplus. Vet. Parasitol. 225, 47–53 (2016).

Abo Talep, E., Abuowarda, M., Abdel-Shafy, S., Mahmoud, N. E. & Fahmy, M. Seasonal variation and morphometric differentiation of Egyptian strain of Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Acari: Ixodidae). Egypt. J. Vet. Sci. 55 (4), 1109–1118 (2024).

Abdel-Ghany, H. S. et al. In vitro acaricidal activity of green synthesized nickel oxide nanoparticles against the camel tick, Hyalomma dromedarii (Ixodidae), and its toxicity on Swiss albino mice. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 83, 611–633 (2021).

Abdel-Ghany, H. S. M. et al. Acaricidal activity of some medicinal plant extracts against different developmental stages of the camel tick Hyalomma dromedarii. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 9 (5), 722–733 (2021).

Sugumar, S. et al. Nanoemulsion of Eucalyptus oil and its larvicidal activity against Culex quinquefasciatus. Bull. Entomol. Res. 104 (3), 393–402 (2014).

Abdel-Ghany, H. S. et al. Acaricidal efficacy of biosynthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles against Hyalomma dromedarii (Acari: Ixodidae) and their toxic effects on Swiss albino mice. Acta Parasitol. 67 (2), 878–891 (2022).

Brody, A. R. & Wharton, G. W. Use of glycerol-KCl in scanning microscopy of Acari. Entomol. Soc. Am. Ann. (1971).

Homsher, P. J. & Sonenshine, D. E. Scanning electron microscopy of ticks for systematic studies 2. Structure of Hallerʼs organ in Ixodes brunneus and Ixodes frontalis. J. Med. Entomol. 14 (1), 93–97 (1977).

Keirans, J. E., Clifford, C. M. & Corwin, D. Ixodes sigelos, n. sp.(Acarina: Ixodidae), a parasite of rodents in Chile, with a method for Preparing ticks for examination by scanning electron microscopy. Acarol 18 (2), 217–225 (1976).

Alves, F. M. et al. Heat-stressed Metarhizium anisopliae: viability (in vitro) and virulence (in vivo) assessments against the tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus. Parasitol. Res. 116, 111–121 (2017).

Abuowarda, M. M., Haleem, M. A., Elsayed, M., Farag, H. & Magdy, S. Bio-pesticide control of the brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus) in Egypt by using two entomopathogenic fungi (Beauveria Bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae). Int. J. Vet. Sci. 9 (2), 175–181 (2020).

Finney, D. J. A statistical treatment of the sigmoid response curve. Probit Analysis. 633 (Cambridge University Press, 1971).

Irache, J. M., Esparza, I., Gamazo, C., Agüeros, M. & Espuelas, S. Nanomedicine: novel approaches in human and veterinary therapeutics. Vet. Parasitol. 180 (1–2), 47–71 (2011).

de Oliveira, A. A., França, L. P., Ramos, A. D. S., Ferreira, J. L. P., Maria, A.C. B., Oliveira, K. M., de Andrade Silva, J. R. Larvicidal, adulticidal and repellent activities against Aedes aegypti L. of two commonly used spices, Origanum vulgare L. and Thymus vulgaris L. S. Afr. J. Bot. 140, 17–24. (2021).

Bishr, M. M. & Salama, O. M. Inter and intra GC-MS differential analysis of the essential oils of three Mentha species growing in Egypt. Futur J. Pharm. Sci. 4, 53–56 (2018).

Figueiredo, A. C., Barroso, J. G., Pedro, L. G. & Scheffer, J. J. C. Factors affecting secondary metabolite production in plants: volatile components and essential oils. Flavour. Fragr. J. 23, 213–226 (2008).

Massoud, M. A., Adel, M. M., Zaghloul, O. A., Mohamed, M. I. E. & Abdel-Rheim, K. H. Eco-friendly nano-emulsion formulation of Mentha Piperita against stored product pest Sitophilus oryzae. Adv. Crop Sci. Technol. 6, 404 (2018).

Nenaah, G. E., Almadiy, A. A., Al-Assiuty, B. A. & Mahnashi, M. H. The essential oil of Schinus terebinthifolius and its nanoemulsion and isolated monoterpenes: investigation of their activity against Culex pipiens with insights into the adverse effects on non-target organisms. Pest Manag Sci. 78 (3), 1035–1047. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.6715 (2022).

Athanassiou, C. G. et al. Nanoparticles for pest control: current status and future perspectives. J. Pest Sci. 91 (1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-017-0898-0 (2018).

Lobato Rodrigues, A. B. et al. M. D. S. Development of nano-emulsions based on Ayapana triplinervis essential oil for the control of Aedes aegypti larvae. PloS One. 16 (7), e0254225. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254225 (2021).

Novato, T. P. et al. Acaricidal activity of carvacrol and thymol on acaricide-resistant Rhipicephalus Microplus (Acari: Ixodidae) populations and combination with cypermethrin: is there cross-resistance and synergism? Vet. Parasitol. 310, 109787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2022.109787 (2022).

Wu, L. et al. Acaricidal activity and synergistic effect of thyme oil constituents against Carmine spider mite (Tetranychus cinnabarinus (Boisduval)). Mol 22 (11), 1873. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22111873 (2017).

Parvin, N., Aslam, M., Joo, S. W. & Mandal, T. K. Nano-Phytomedicine: Harnessing Plant-Derived phytochemicals in nanocarriers for targeted human health applications. Mol 30 (15), 3177. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30153177 (2025).

da Silva, L. C. et al. In vitro acaricidal activity of cymbopogon citratus, cymbopogon nardus and mentha arvensis against R. microplus (Acari: Ixodidae). Exp. Parasitol. 216, 107937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exppara.2020.107937 (2020).

Agwunobi, D. O., Pei, T., Wang, K., Yu, Z. & Liu, J. Effects of the essential oil from Cymbopogon citratus on mortality and morphology of the tick Haemaphysalis longicornis (Acari: Ixodidae). Exp. Appl. Acarol. 81 (1), 37–50 (2020).

Dey, S., Sinha, B. & Kalita, J. Effect of Eupatorium adenophorum spreng leaf extracts on the mustard aphid, Lipaphis erysimi kalt: A scanning electron microscope study. Microsc Res. Tech. 66, 31–36 (2005).

Ellse, L. & Wall, R. The use of essential oils in veterinary ectoparasite control: A review. Med. Vet. Entomol. 28, 233–243 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The proprietors and technicians of the Parasitology department at Cairo University’s Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, who authorized the collection of samples and assisted in raising the colony to support our work, have our sincere gratitude.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M.F., M.A., and S.A. assisted with selecting the study topic, gathering relevant material, conceptualizing the work, rewriting the data, interpreting the findings, evaluating the work, analyzing the data, and composing the manuscript. E.A.A., H.S.M.A., and E. I. H. shared in the bioassay of oil, its nano-emulsion, TNE &Ag NPs against the unfed adult stage of R. sanguineus. F.A. prepared and characterized the oil and nano formulations. All authors prepared the literature collection, conceptualization, and wrote the draft of the manuscript, and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All experimental procedures involving animals were conducted in accordance with institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the [The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, IACUC], [Cairo University], under approval number [CUIIF6323]. This study is reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org), ensuring transparency and reproducibility in animal research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Talep, E.A.A., Abuowarda, M., Abdel-Shafy, S. et al. Efficacy of thyme oil and nano-formulated derivatives against Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato (Acari: Ixodidae). Sci Rep 16, 7384 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37451-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-37451-9