Abstract

In the digital economy, the relationship between customers and companies is a win-win cooperation, and value co-creation has become the mainstream business development concept. Against this background, customer citizenship behaviours have received increasing and widespread attention in marketing and consumer behaviour research. However, previous studies have not sufficiently considered the importance of trait emotions in predicting customer citizenship behaviours. By focusing on a specific emotional disposition with positive functions, dispositional awe, this study develops an integrative model based on the prototype model of awe and the elaborated model of awe’s prosocial effects. This model examines the impact of dispositional awe on customer citizenship behaviours and analyses the roles of construal level and social connectedness in it. Drawing on a sample of 701 questionnaires from Chinese adults and using structural equation modelling, this study finds that dispositional awe contributes positively to three types of customer citizenship behaviours: making recommendations, helping other customers, and providing feedback. In addition, dispositional awe can influence customer citizenship behaviours through the independent mediating effect of social connectedness as well as the serial mediating effect of construal level and social connectedness. These findings suggest that frequent experiences of awe help develop an individual’s internal abstract mindset and subjective sense of connection to external society, thereby motivating customer citizenship behaviours. This study provides valuable insights into whether and how dispositional awe can influence customer citizenship behaviours and offers operational strategies for marketing practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Imagine you are a loyal customer of a particular brand of mobile phone. Would you enthusiastically recommend this brand when someone asks for advice on buying a mobile phone or when your friends or family are considering changing their mobile phones? Would you help other customers in the brand’s community or related forums with questions about using, setting up or troubleshooting their mobile phones? Would you actively participate in the brand’s user surveys or questionnaires to provide feedback to the brand on product performance, user experience and more? In today’s “value co-creation” era, these questions often arise in people’s daily lives.

In recent years, with the rapid changes in the competitive market environment and the widespread use of digital technologies, business development has embraced value co-creation. (Assiouras et al., 2019; Rangaswamy et al., 2022). Customer Citizenship Behaviours (CCBs), which include recommending products to others, helping other customers in trouble, and providing feedback to the company to improve products, play vital roles in value co-creation (Yi and Gong, 2013). CCBs are voluntary and extra-role customer behaviours contributing to a company’s value creation (Mitrega et al., 2022). They have become a focus of marketing and consumer behaviour research. CCBs have been shown to enhance customer happiness and repeat business (Gong and Yi, 2021), improve employee productivity (Shannahan et al., 2017), and help companies gain more valuable information to build a competitive advantage (Curth et al., 2014). Given the ubiquity and practical significance of CCBs, continued research into the mechanisms that drive them is essential.

Antecedents of CCBs can be divided into five categories: customer characteristics, other customer characteristics, service characteristics, employee characteristics, and organisational characteristics (Gong and Yi, 2021). Among the five types of antecedents, customer characteristics are the most important in driving CCBs because the customer is the behavioural subject (Anaza, 2014). Many scholars have investigated the relationship between customers’ attitudinal characteristics and CCBs. They found that customer identification (Ahearne et al., 2005), customer satisfaction (Bettencourt, 1997), and justice perceptions (Yi and Gong, 2008) positively predict CCBs. In recent years, scholars have increasingly focused on how customers’ individual traits affect CCBs, finding that individual self-efficacy (Alves et al., 2016), public self-awareness (Dang and Arndt, 2017), agreeableness, extraversion (Anaza, 2014), and prosocial or proactive personality (Choi and Hwang, 2019) are significant predictors of CCBs. According to Choi and Hwang (2019) and Anaza (2014), being voluntary and spontaneous actions outside of an individual’s role obligations, CCBs tend to be driven less by attitudes and more by personal traits, personality attributes, and daily emotional states. For example, consider two customers: one proactive and one inactive. Although they identify with a brand, they may not both promote it to others. The proactive customer is more likely to recommend. Therefore, exploring the promotion mechanism of CCBs from the perspective of customers’ individual traits is one of the current research topics (Mitrega et al., 2022).

However, the existing studies in this area have some shortcomings. Although individual traits strongly influence CCBs, the traits studied to date (e.g., prosocial personality, agreeableness, public self-consciousness) are pretty stable and hardly change over time or with external stimuli. These studies are of limited practical use because companies can only passively match target segments to these traits in the hope of producing CCBs. In contrast, trait emotions, as dispositional emotional tendencies that indicate the frequency and intensity of specific emotions experienced by individuals (Guedes et al., 2018; Lerner et al., 2015), not only are individual trait variables but also exhibit higher variability. These properties suggest that trait emotions can be a strong predictor of CCBs; furthermore, there is a high degree of scope for companies to cultivate and develop specific trait emotions to promote CCBs. Thus, trait emotions should be used to study the promotion of CCBs. Dispositional awe, on the other hand, is a trait emotion that has recently received much attention in psychology and consumer behaviour. It promotes prosocial behaviours such as helping others (Piff et al., 2015), socially responsible consumption (Hu, 2023), organisational citizenship behaviours (Tian et al., 2016), and tourists’ helping behaviours (Chen et al., 2021). As customers voluntarily engage in prosocial behaviours to benefit other customers, companies, or employees (Chen et al., 2013), can CCBs also be driven by dispositional awe? Are people who frequently experience awe more likely to engage in CCBs? What are the intrinsic mechanisms? Unfortunately, these questions have received little attention.

Frequent experiences of awe would create a sense of interconnectedness with everything around one (Yaden et al., 2019), promoting prosocial tendencies or behaviours (Luo et al., 2023). Therefore, dispositional awe may enhance CCBs through social connectedness. In addition, few studies have examined the mediation pathways between awe and social connectedness. Construal level, which measures the abstraction of mental representations, may reflect the richness of mental resources and depth of thought (Trope and Liberman, 2010). We propose that construal level would help to explain the above pathways. Moreover, dispositional awe may improve social connectedness by increasing construal level and ultimately inspiring CCBs. In this paper, we present hypotheses and a theoretical model based on the prototype model of awe and the elaborated model of awe’s prosocial effects and demonstrate the association between dispositional awe and CCBs, the independent mediating role of social connectedness, and the serial mediating role of construal level and social connectedness through questionnaires and structural equation modelling.

There are theoretical contributions and practical implications to this study that are worth highlighting. First, we present a response to the recent call by Mitrega et al. (2022) in their systematic review to further explore other antecedents of CCBs from the perspective of customer traits. The introduction of trait emotions will fill the gap in previous studies. Second, we extend the prosocial nature of dispositional awe to the context of customer-company value co-creation, thereby broadening the behavioural outcome studies of awe. This extension will also provide the basis for subsequent studies of awe and other co-creative consumer behaviours, such as customer participation in new product innovation. Third, disentangling the mediating roles of construal level and social connectedness can deepen the exploration of the psychological mechanisms of the impact of dispositional awe on prosocial behaviours. The relationship between intrapersonal and interpersonal mental elements facilitating CCBs will become more apparent. In addition, we provide valuable practical ideas on how marketers can motivate CCBs in the business era of “co-creation.”

Literature review and hypothesis formulation

Awe and dispositional awe

Awe is an emotional response to something vast, incomprehensible, and beyond current cognition. It is a complex mixture of shock, wonder, novelty, and fear (Keltner and Haidt, 2003). Magnificent natural landscapes, stunning product designs, deep theoretical knowledge, and outstanding great leaders can all elicit awe-inspiring experiences (Septianto et al., 2020). There are two types of awe: state awe and dispositional awe (Li et al., 2019). State awe can be generated by watching a documentary about magnificent scenery or novel creatures in a laboratory (Guan et al., 2019). Dispositional awe refers to individual differences in feeling awe. Those with higher dispositional awe have more awe experiences (Shiota et al., 2006). Dispositional awe is positively associated with low cognitive closure needs and high uncertainty tolerance (Shiota et al., 2007). This ability enables people to enjoy being among information-rich, complex, and novel stimuli (Chen and Mongrain, 2021).

The prototype model of awe

The most initial and representative theory in the science of awe is the prototype model of awe proposed by Keltner and Haidt. The theory suggests that two critical features of awe are perceived vastness and the need for accommodation (Keltner and Haidt, 2003). The former refers to an individual’s perception of a vast stimulus beyond cognitive reference frames, such as students experiencing Einstein’s theory of relativity for the first time. The latter refers to the need to actively extend old schemas to accommodate new content when an individual’s initial cognitive schema cannot assimilate novel stimuli (Zhao et al., 2021). Understanding the theory of relativity requires adjusting one’s conceptual framework of time and space (Chirico and Yaden, 2018). In other words, awe is an emotional response that experiences the shock of an external stimulus and requires cognitive restructuring to adapt to it (Richesin and Baldwin, 2023). The characteristics of vastness and accommodation dictate that awe has a transformative ability to induce psychological changes and facilitate behavioural adjustments (Lucht and van Schie, 2024).

The elaborated model of awe’s prosocial effects

Much of awe’s transformative nature is reflected in its prosocial effects. Awe makes people feel connected to others (Yaden et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2024), reduces integrity violation (Zhao et al., 2023), and can lead to greater identification with universal category labels (Shiota et al., 2007), such as “inhabitant of the Earth.” Table 1 summarises some previous research on the prosocial effects of awe.

Most previous studies have relied on the small-self hypothesis for the causes of these prosocial effects. This view suggests that a sense of vastness in response to awe-inspiring stimuli makes the self small, causing people to perceive themselves and their daily concerns as insignificant and to shift attention from the self to external others, thereby promoting prosociality (Bai et al., 2017; Piff et al., 2015; Yang and Hu, 2021). However, as the study of awe has deepened, many scholars have criticised it recently. On the one hand, scholars argue that the meaning of the small self is not clear enough and that there is conceptual confusion. Using exploratory factor analyses, Tyson et al. (2022) identified distinct dimensions in existing measures of the small self. For example, vastness relative to self was positively associated with self-esteem, whereas self-smallness (or self-diminishment) was negatively associated with self-esteem (Hornsey et al., 2018; Tyson et al., 2022). The former represents self-expansion, whereas the latter represents self-shrinking. The simple summation of such opposed dimensions is not rigorous. A similar view is held by Yuan et al. (2024), who argued that if the small self implies the diminishment of excessive self-focus or the decrease of self-salience, the small self will increase meaning in life. Whereas, if the small self implies a negative self-evaluation of oneself as insignificant and small, then the small self will decrease meaning in life.

On the other hand, Perlin and Li (2020) argued that the small-self hypothesis oversimplifies the complex concept of the self. They claimed that the small-self hypothesis pits attention to the self against attention to others without emphasising attention to the interdependent “we.” At the same time, the small-self hypothesis overemphasises shifting attention. It fails to account for the transformative growth inherent in individuals under the influence of the accommodative processing of awe, which is inconsistent with Keltner and Haidt’s (2003) original account of awe.

Considering these shortcomings, Perlin and Li (2020) proposed the elaborated model of awe’s prosocial effects to address the shortcomings of the small-self hypothesis. First, the theory suggests that in the psychological mechanism of the prosocial effects of awe, awe increases concern for the interdependent “we” between self and others. This collective concern is different from a single selfish concern, nor is it blind obedience for the sake of others, but rather a balanced sense of interconnectedness. Second, the theory also suggests that this increased awareness of interdependence reflects an abstract, high-level intrinsic motivation. Furthermore, this motivation arises from the cognitive adjustments and self-development produced by the need for accommodation. In other words, the cognitive accommodation brought about by awe facilitates an internal transformation of the individual, leading to greater attention to the interdependence between the self and the outside world, which results in a range of concrete prosocial behaviours. Current research exists to confirm the theoretical logic of this model. For example, Jiang and Sedikides (2022) found that awe promotes prosociality through authentic-self pursuit. We believe the model can adequately explain the psychological mechanisms underlying the relationship between dispositional awe and customer citizenship behaviours.

Dispositional awe and customer citizenship behaviours

Customer citizenship behaviours (CCBs) are an extension of organisational citizenship behaviours (OCBs), which are voluntary consumer actions that benefit the company (Groth, 2005). It can also be considered nonessential extra-role behaviours in addition to customer transactional behaviours (Mitrega et al., 2022). Voluntariness, positivity, and non-tradability define CCBs. Voluntariness means that CCBs are customer-generated rather than company-mandated. Positivity means that CCBs are ecologically beneficial to the company. Non-tradability means that CCBs do not fulfil the traditional customer role and are unnecessary for production or service transactions. Groth (2005) divided CCBs into customer recommendation, helping, and feedback. Recommendation involves actively recommending products or services to others, for example, praising the quality of a company’s products to a friend through positive word-of-mouth. Helping involves assisting other customers with the company’s goods and services, for example, offering advice, experience or support to customers with problems using a product. Feedback involves providing requested information to the company to improve products or services, for example, participating in the company’s customer survey and making genuine suggestions (Gong and Yi, 2021). We use the above classification approach because many scholars (Anaza, 2014; Li and Wei, 2021; Wang et al., 2021) accept this three-dimensional model.

Given the extensive previous research on the prosocial effects of awe, we have sufficient arguments to infer a predictive role for dispositional awe on CCBs. First, as an emotion with self-transcendent properties (Hu et al., 2018), awe, like compassion and gratitude, can encourage people to transcend their personal interests and consider the needs of others (Stellar et al., 2017), which may influence recommendation or sharing behaviour. Piff et al. (2015) found that participants in a dictator game with higher dispositional awe shared more tokens with strangers. Wang et al. (2022) found that awe encourages resource-sharing. Thus, in everyday brand communication, customers with higher dispositional awe are more likely to recommend or share their favourite or familiar brands.

Second, awe is also an epistemological emotion. It transforms an individual’s self-concept, worldview, or view of time (Perlin and Li, 2020; Richesin and Baldwin, 2023), affecting self-other relationships and helping behaviour. Jiang and Sedikides (2022) found that dispositional awe increased authentic-self pursuit and genuine altruism. Chen et al. (2021) found that tourists who felt more awe perceived more time and were more willing to help other tourists actively. Thus, customers with high dispositional awe will be intrinsically motivated to help other customers with confusion or problems.

Third, positive emotions are associated with creativity, openness and altruism (Fredrickson, 2001). Awe can be positive or negative (Gordon et al., 2017), but most scholars believe it belongs to the family of positive emotions (Chirico and Yaden, 2018; Danvers and Shiota, 2017; Monroy and Keltner, 2023), which allows people to give feedback or voice behaviour. Hu and Meng (2022) claimed that awe increases organisational citizenship behaviours. Tian et al. (2016) found that dispositional awe motivates organisational members to contribute constructive ideas actively. Thus, as a “part-time employee”, the higher the level of dispositional awe, the more likely a customer is to offer genuine advice or suggestions to the company out of openness or altruism in today’s value co-creation context. Awe also inspires creativity, as Rudd et al. (2018) found. Accordingly, customers with higher dispositional awe are more likely to provide feedback with innovative ideas. Thus, we hypothesise the following:

H1: Dispositional awe positively influences the recommendation behaviour (a)/helping behaviour (b)/feedback behaviour (c) of CCBs.

Mediating effect of social connectedness

We can learn more about why this happens by examining how dispositional awe affects CCBs via mediators. According to the elaborated model of awe’s prosocial effects, in promoting prosociality, awe may increase concern about the interdependence of self and others (Perlin and Li, 2020). At the same time, social connectedness reflects an individual’s overall sense of closeness, solidarity, and dependence between self and others or society (Zhao and Zhang, 2023). Therefore, we believe that social connectedness will be an essential mediator.

Social connectedness refers to an individual’s full awareness of the closeness of interpersonal relationships (Lee et al., 2001), an essential component of the sense of belonging. According to ego psychology theories, belonging has three components: companionship, subordinate relationships, and social connectedness, where social connectedness is a self-identified structure of interpersonal relationships in a broader social context that reflects the individual’s subjective feelings about the degree of connection between self and others or society (Lee and Robbins, 1998). Social connectedness is negatively associated with loneliness, alienation, and inferiority (Lee and Robbins, 1995). It can reduce anxiety, distress, and depression (Nitschke et al., 2021; Taylor et al., 2020) and increase self-esteem, interpersonal trust, and subjective well-being (Arslan, 2018).

There is a strong relationship between awe and social connectedness. Theorists suggest that one of the hallmarks of self-transcendent experiences, such as awe, is the creation of a sense of connectedness with other people or other beings in the environment beyond the self (Stellar et al., 2017; Yaden et al., 2017). This increased level of connectedness reflects an expansion of the self. As the boundaries of the self expand to encompass other people, groups, or nature, a sense of oneness with the outside world is even felt (Diebels and Leary, 2019). Empirical research confirms that awe leads people to perceive themselves as more connectedness and oneness with others (Van Cappellen and Saroglou, 2012). Awe can also lead people to describe themselves in terms of universal groups, such as humans or sentient beings (Shiota et al., 2007). They will see themselves as part of a larger group or even an entire species (Bai et al., 2017). According to Seo et al. (2023), awe may promote cosmopolitan citizenship and global citizenship identification, increasing a sense of connectedness to humanity. Experiencing awe increases an individual’s connection to the world and positively predicts empathic concern and prosocial behaviour (Luo et al., 2023). Research more relevant to our trait emotions of interest has found that social connectedness mediates the relationship between dispositional awe and psychosocial flourishing (Zhao and Zhang, 2023). We therefore hypothesise the following:

H2: Dispositional awe positively influences social connectedness.

Little research has been done on social connectedness and CCBs. However, some inferences can be drawn from the following points. First, social exchange theory states that the “reciprocity principle” requires people to return social value (Gong and Yi, 2021). Highly socially connected people actively feel emotional warmth from family, community, strangers, and society (Lee and Robbins, 1998). They are more likely to follow the “reciprocity principle” and engage in prosocial behaviours to satisfy their social exchange motivation. These behaviours may include making recommendations, helping others, and providing feedback that benefits other customers, employees, or the company during daily brand communication or company interactions. Second, the review by Morelli et al. (2015) showed that social connectedness increases empathy for others, which in turn enhances customer satisfaction and CCBs (Anaza, 2014). These findings suggest that social connectedness increases perspective-taking ability, making people more likely to put themselves in others’ shoes (Lee and Robbins, 1998), more attentive and empathetic to companies’ and customers’ needs, and more likely to recommend, help, and provide feedback. Third, from a motivational perspective, Dubois et al. (2016) found that low levels of interpersonal closeness activate motivations to enhance self, and high levels activate motivations to protect others. Because social connectedness leads individuals to feel that self and society are closely connected, highly socially connected individuals are more likely to engage in behaviours that protect the interests of other customers and the company, such as recommendation, helping, and feedback behaviours. Thus, we hypothesise the following:

H3: Social connectedness positively influences the recommendation behaviour (a)/helping behaviour (b)/feedback behaviour (c) of CCBs.

In summary, social connectedness may play a mediating role between dispositional awe and CCBs, suggesting the following hypothesis:

H4: Social connectedness mediates the association between dispositional awe and the recommendation behaviour (a)/helping behaviour (b)/feedback behaviour (c) of CCBs.

Serial mediating effect of construal level and social connectedness

Dispositional awe may affect CCBs through social connectedness, but is there a variable that explains well how dispositional awe affects social connectedness in the first stage of this mediation pathway? According to the elaborated model of awe’s prosocial effects, the concern for interdependence enhanced by awe stems from the individual’s more profound understanding of self and self-motivation, and this intrinsically transformative growth is closely linked to the accommodative cognitive integration that comes with awe (Perlin and Li, 2020). According to the prototype model of awe, the awe-eliciting stimulus challenges the individual’s original cognitive structure, creating a cognitive imbalance and a need for accommodation to expand the cognitive schema. Once the cognitive schema is successfully expanded, epiphany, rebirth and growth are achieved (Keltner and Haidt, 2003; Richesin and Baldwin, 2023). Taking the two theories together, it is likely that accommodative processing of awe enhances an individual’s cognitive abilities, enhancing the sense of interdependence. Thus, construal level, a key variable in cognitive representation, may play a role.

Construal level is the level of abstraction at which people make mental representations of cognitive objects (Trope and Liberman, 2010). High-level construal produces abstract, decontextualised, superordinate, and highly schematised representations that reflect core properties. Low-level representations are concrete, contextualised, subordinate, and less schematised, reflecting surface properties (Septianto et al., 2023). In action identification, high-level construal asks “why” and identifies “reading” as “acquiring knowledge,” which is more abstract. Low-level construal emphasises action performance, thinking about “how” and identifying “reading” as “reading line by line,” which is more concrete (Vallacher and Wegner, 1989). The psychological distance between a person and a cognitive object determines construal level (Trope and Liberman, 2010). In addition to being influenced by context, construal level can also be a habit or characteristic that develops over time. Thus, construal level varies from person to person. High-construal people are used to abstract representations, whereas low-construal people prefer concrete representations (Bullard et al., 2019). Those with a high construal level are more likely to engage in abstract, holistic and inclusive thinking (Hong and Lee, 2010).

Construal level is related to accommodation in awe. Accommodation reduces cognitive closure and updates cognitive schemas for changing environmental stimuli (Shiota et al., 2007). Increasing cognitive flexibility helps integrate mental resources and expand thinking (Bullard et al., 2019). As schema updating and mental resources increase, people will interpret problems with a more abstract, global, and deeper mindset (high-level construal processing). Several recent empirical studies have provided direct evidence for the relationship between awe and construal level. Pan and Jiang (2023) concluded that awe triggers high-construal-level mental representations and enhances people’s global processing to promote global self-continuity. Dai and Jiang (2023) also argued that the self-transcendence property of awe would help people achieve higher construal level. Septianto et al. (2023) found that construal level mediates the relationship between state awe and advertising effectiveness. Awe increased construal level and abstract thought, making people prefer ads emphasising product desirability. Furthermore, construal level has been found to mediate the relationship between awe and tourists’ environmentally responsible behaviour (Xu and Hu, 2023). These findings provide clues for inferring the relationship between dispositional awe and construal level. Thus, we hypothesise the following:

H5: Dispositional awe positively influences construal level.

In turn, increasing the construal level further strengthens social connectedness. First, construal level increases cognitive processing from concrete to abstract (Trope and Liberman, 2010). Awe can produce a more abstract perspective that allows the individual to think about the nature of the world in an intelligent, philosophical view (Stellar, 2021). This nature is to see everything that exists as part of an all-encompassing root entity. This idea of the oneness of all things promotes a deeper understanding of our common humanity and a greater acceptance of the statement, “I feel that, on a higher level, we all share a common bond” (Diebels and Leary, 2019). In addition, Levy et al. (2002) found that people who are used to describing behaviour in abstract terms see more similarities than differences between themselves and others. They are more likely to empathise with and help others, demonstrating the link between construal level and social connectedness.

Second, increasing the construal level changes a person’s focus from personal to holistic (Trope and Liberman, 2010). Liberman et al. (2002) discovered that high-construal individuals use more inclusive categories to categorise objects. In Henderson’s (2011) negotiation study, high-construal individuals were more likely to consider the pros and cons from a global perspective and seek a win-win outcome. Septianto et al. (2022) found that subjects who activated a high construal level had a broader range of thinking, were more able to transcend narrow egocentric emotions, were more caring, and engaged in more charitable behaviours than those in the low construal condition. These findings suggest that high-construal individuals may feel more socially connected. Thus, we hypothesise the following:

H6: Construal level positively influences social connectedness.

Expanding the mechanism’s first half will help refine dispositional awe’s effects on CCBs. Overall, frequent experiences of awe will continually create a need for accommodation, and through cognitive accommodative processing, individuals high in dispositional awe will gain an increased construal level. As the construal level increases, abstract and holistic thinking increase social connectedness. Social connectedness increases social exchange, empathy, and protective motives, leading to more recommendation, helping, and feedback behaviours in the context of brand communication and interaction with companies. Thus, dispositional awe may influence CCBs via construal level and social connectedness, supporting the following hypothesis:

H7: Dispositional awe is positively associated with the recommendation behaviour (a)/helping behaviour (b)/feedback behaviour (c) of CCBs via the serial mediation of construal level and social connectedness.

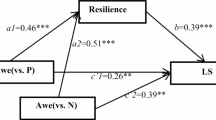

The theoretical model for this study is summarised in Fig. 1.

Materials and methods

Measurement tools and questionnaire design

This questionnaire-based study was conducted in China. The instruments measured each variable:

Dispositional awe

Shiota et al.’s (2006) DPES awe subscale was used. The subscale includes six items, such as “I often feel awe” and “I enjoy seeking out experiences that challenge my understanding of the world.”

Construal level

Vallacher and Wegner’s (1989) Behaviour Identification Form was used. Twenty-five items on the form require participants to choose the best of two behavioural explanations (corresponding to a low-level and a high-level construal). For example, “Chopping a tree” can mean “wielding an axe” or “getting firewood.” The former emphasises “how”—a concrete, low-level construal—to describe the behaviour. The latter emphasises the “why” behind the behaviour, which is abstract and matches the high-level construal. Low-level choices score 0 points, and high-level choices score 1 point. Higher scores indicate a higher construal level.

Social connectedness

Lee et al. (2001) revised the 20-item Social Connectedness Scale used here. It has ten reverse-scoring and ten forward-scoring items. Representative items include “I feel disconnected from the world around me” (reverse-scoring) and “I am in tune with the world.”

Customer citizenship behaviours

Groth’s (2005) Customer Citizenship Behaviours Scale was adopted. The three dimensions—customer recommendation, helping, and feedback—have four items each. Examples of recommendation behaviour include “I would recommend the brand’s products or services to my peers.” Examples of helping behaviour include “I would assist other customers in finding products or services of this brand.” Examples of feedback behaviour include “I would provide helpful feedback to the brand officialFootnote 1.”

Control Variable

The confounding variable must be controlled to rule out customer attitude factors as an explanation for CCBs. Social identity theory suggests that people’s emotional attachment to a company or brand causes them to act in ways that benefit the company and related groups (Ahearne et al., 2005). Thus, as a control variableFootnote 2, we measured respondents’ brand identification. The Consumer-Brand Identification Scale by Tuškej et al. (2013) was used. It has three questions, such as “I feel that my personality and the personality of this brand are very similar.”

These mainstream journal scales have been validated in China. We used translation first and back-translation for localisation and invited experts to verify face and content validity. We also created a panel to reasonably revise some questionnaire items to fit Chinese reading habits and avoid semantic ambiguity and vagueness. All scales except the construal level used seven-point Likert scales ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (7). All scale items are included in the Supplementary Material.

The final questionnaire contained 66 academic scale items, one screening item, one fill-in-the-blank item, and four demographic information items. There were four parts. The first part explained the questionnaire’s anonymity and confidentiality and obtained informed consent from the respondents. The second part assessed dispositional awe, construal level, social connectedness, and a screening question to determine whether the respondent was careful (“Please select 7 for this item”). In the third part, the respondents were asked to review and report a brand they were more familiar with (an additional fill-in-the-blank question). Then, the Brand Identification Scale and Customer Citizenship Behaviours Scale were completed for that brand. In the fourth part, the respondents provided their gender, age, education, and occupation, and we thanked them at the end. Each respondent was allowed one anonymous questionnaire. The respondents had the option to opt-out.

Power analysis

Before data collection, we conducted power analyses inspired by Zhai et al. (2022) to estimate the minimum sample size required to construct this study’s structural equation model (SEM). We used their SEM statistical power threshold of 0.95.

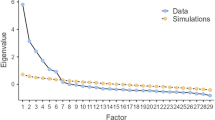

We power-analysed the model fit test. Jak et al. (2021) developed the online programme power4SEM (https://sjak.shinyapps.io/power4SEM/) to perform MacCallum RMSEA tests of close and not-close fit. First, the statistical power of the measurement model was examined using the original item numbers. The measurement model degrees of freedom (Crede and Harms, 2019) for the original data in this study were (66 × (66 + 1)/2) − 2 × 66 − (7 × (7 − 1)/2) = 2058. The sample size analysis showed that for a close fit (α = 0.05, RMSEA H0 = 0.05, RMSEA H1 = 0.08), it was 31, and for a not-close fit (α = 0.05, H0 = 0.05, H1 = 0.01), it was 47. Second, the statistical power of the structural model was examined. We planned to parcel scales with too many measurement items in the structural modelling part using the factorial algorithmFootnote 3 (Rogers and Schmitt, 2004). The construal level scale items were parcelled from 25 to 5, and the social connectedness scale items were parcelled from 20 to 4. Figure 2 shows this study’s theoretical model’s SEM path diagram. Thirty indicators were measured. In addition to the fixed latent variable variances, there were 75 freely estimated parameters, including 30 factor loadings, 30 residual variances, 12 structural path parameters, and three residual covariances. Thus, the model’s degrees of freedom were (30 × (30 + 1)/2) − 75 = 390. The sample size analysis showed that for close fit, it was 80, and for not-close fit, it was 112.

DA dispositional awe; CL construal level; SC social connectedness; RB CCB recommendation behaviour; HB CCB helping behaviour; FB CCB feedback behaviour; BI brand identification. Circles indicate latent variables, rectangles indicate observed variables, and single arrows indicate linear regression coefficients. Double-headed rings beginning and ending on the same variable indicate variances or residual variances, and double-headed arrows connecting two variables indicate covariances. Dashed lines indicate fixed parameters and solid lines indicate free parameters.

We also power-analysed the model parameter estimation. The R source code provided by Wang and Rhemtulla (2021) was run, opening pwrSEM (also available at https://yilinandrewang.shinyapps.io/pwrSEM/) and using Monte Carlo simulation to analyse the power of the target mediating effects. After using lavaan syntax and the parcelled model, a model path diagram corresponding to Fig. 2 was created. Then, we set parameters in the “set parameter values” tab. First, we conservatively set all factor loadings to 0.5 according to the criteria of Comrey and Lee (1992). Second, Cohen (1988) classified observed variable correlation analysis effect sizes as small, medium, or large: 0.1, 0.3, or 0.5. We set the latent regression coefficients to 0.3 with an effect size below medium, as the estimate of the correlation between the latent variables using the “help” tab is 0.25–0.35 (0.1 ≤ r ≤ 0.3, 0.7 ≤ Cronbach’s alpha ≤ 0.9). Next, the “set residual variances for me” function automatically set each observed variable’s residual variance to 0.75, and the residual covariances among the three CCBs were set to 0.6 (r = 0.5, 0.7 ≤ Cronbach’s alpha ≤ 0.9). Three independent mediators had effect values of 0.09; three serial mediators had effect values of 0.03. Then, we performed the final estimation. The results showed that for the analysis of the six mediating effects, when the alpha level was 0.05, the number of simulations was 1000, and the sample sizes were 200, 400, 600, and 800, the minimum values of the six statistical powers were 0.03, 0.47, 0.87, and 0.98, respectively. When the statistical power was 0.95, the sample size was 686.

Therefore, we need at least 686 respondents to reach the maximum value of the power analysis.

Sampling and data collection

The questionnaires were distributed, collected, and verified through Credamo’s data market in September 2022. The respondents who passed data verification were rewarded with a certain amount of RMB. Credamo (https://www.credamo.world/) is a Chinese professional online research platform similar to MTurk or Prolific. Due to its versatility, data recovery efficiency, and verification rigour, Credamo is widely used by researchers for experimental and survey research (Jiang and Sedikides, 2022; Pan and Jiang, 2023; Yuan et al., 2024). Credamo’s data market has over 3 million registered Chinese respondents, which allows us to randomly sample Chinese respondents of all ages, regions, occupations, and educational backgrounds, improving our study’s external validity.

We collected 776 questionnaires. We rejected 75 questionnaires for “not answering the screening questions correctly,” having a “too short or too long answer time,” coming from a “repeated IP address,” and “repeated selection of the same option” in multiple rounds of verification, leaving 701 valid questionnaires for a valid recovery rate of 90.3%. A calculated sample size of 686 was achieved. Table 2 shows the sample composition. Respondents averaged 29.71 years old. They had diverse backgrounds and educations. The brands that respondents filled in covered a wide range of industries, such as mobile phones/computers (e.g., Apple, Huawei), apparel (e.g., Nike, Li Ning), cosmetics (e.g., Lancome, Chanel), home appliances (e.g., Haier, Panasonic), and catering/food (e.g., Coca-Cola, Starbucks). Therefore, the results of this study are highly generalisable.

Results

Measurement model and preliminary analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis

Using Mplus 8.3, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of a seven-factor measurement model based on dispositional awe, construal level, social connectedness, customer recommendation behaviour, helping behaviour, feedback behaviour, and brand identification. The results showed that χ2/df = 2.478, RMSEA = 0.046, SRMR = 0.051, CFI = 0.916, and TLI = 0.910, which met the discriminant criteria of χ2/df less than 3, RMSEA less than 0.06, and SRMR less than 0.08 (Hu and Bentler, 1999). CFI and TLI were also greater than 0.9, which reached an acceptable range (Wen et al., 2018), indicating a good fit for the measurement model.

Common Method Bias Tests

To statistically test for common method bias (CMB), we used three approaches to minimise the potential imprecision of any single approach. First, Harman’s single-factor test was used to test for CMB. The first common factor explained 28.231% of the total variance in nonrotated exploratory factor analysis, well below the 50% requirement (Kock et al., 2021).

Second, we also used the unmeasured latent method construct (ULMC) approach (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The rationale for this approach is to introduce a common method factor encompassing all items as indicators in the original CFA model. If the CFA fit is significantly better (RMSEA and SRMR decreased by more than 0.05, and CFI and TLI increased by more than 0.1), it indicates a serious CMB (Wen et al., 2018). Our data suggested that the inclusion of the method factor did not significantly improve the fit indices (ΔRSMEA = 0.009 < 0.05, ΔSRMR = 0.016 < 0.05, ΔCFI = 0.052 < 0.1, ΔTLI = 0.052 < 0.1).

Third, further tests were carried out using the CFA marker technique. This approach has higher power (Richardson et al., (2009)). The rationale of this approach is to progressively build several competing models by introducing a marker variable that is theoretically unrelated to the substantive variables and then sequentially comparing the models’ differences. A significant difference between the final Method-R and Method-C or Method-U models indicates a serious CMB (Williams et al., 2010; Simmering et al., 2015). As Podsakoff et al. (2012) suggested, we chose educational attainment as a marker variable in this study. The goodness-of-fit values and model comparison results for each model are shown in Table 3. Finally, when the Method-U model was compared with the Method-R model, the difference was insignificant (p = 0.256).

Based on the above test results, no serious CMB was found in this study.

Reliability and validity of measures

Each scale’s average variance extraction (AVE), composite reliability (CR), and Cronbach’s alpha were calculated. The results (see Table 4) showed that the CR values and Cronbach’s alphas were greater than 0.7, the factor loadings and AVE values were greater than 0.5, indicating that the constructs had good reliability and convergent validity. We also conducted descriptive statistics and correlation analysis. As shown in Table 5, the square roots of the AVEs are greater than the correlation coefficient between the variables, indicating that the constructs have good discriminant validity.

In addition, dispositional awe was significantly and positively correlated with customer recommendation (r = 0.499), helping (r = 0.579), feedback (r = 0.528), social connectedness (r = 0.633), and construal level (r = 0.336). Social connectedness was significantly and positively correlated with recommendation (r = 0.521), helping (r = 0.578), feedback (r = 0.551), and construal level (r = 0.335). The results of the correlation analysis initially supported our research hypotheses. In addition, since age is significantly correlated with various CCBs, we also used age as a control variable in the subsequent hypothesis testing.

Structural model and hypothesis testing

Test of main effects

Using Mplus 8.3, we analysed the structural model using maximum likelihood (ML) parameter estimation without including mediator variables. The effects of dispositional awe on three CCBs were examined after controlling for age and brand identification. The goodness of fit indices indicated a reasonably good model fit: χ2/df = 2.797, RMSEA = 0.051, SRMR = 0.047, CFI = 0.966, TLI = 0.957. Figure 3 shows that dispositional awe significantly and positively influenced customer recommendation behaviour (β = 0.608, SE = 0.035, t = 17.422, p < 0.001), helping behaviour (β = 0.704, SE = 0.029, t = 24.278, p < 0.001), and feedback behaviour (β = 0.666, SE = 0.033, t = 20.394, p < 0.001). The R2 effect size of recommendation, helping, and feedback behaviour were 0.387, 0.508, and 0.485. H1a–H1c were confirmed.

Item parcelling and model comparisons

To improve the mediation model’s modelling efficiency and fit stability, we parcelled two mediating variables with too many items using the factorial algorithm (Rogers and Schmitt, 2004). Specifically, the items of the two scales were parcelled separately according to the size of the factor loadings based on the CFA results, using a balancing strategy to ensure that the means of the factor loadings in each parcel were equivalent (Wu and Wen, 2011). The construal level items were parcelled into five indicators, and the social connectedness items were parcelled into four.

Next, we conducted model comparisons to ensure that our theoretical model best fit the sample data before proceeding to hypothesis testing of the mediating effects. After controlling for age and brand identification and incorporating the parcelled mediating variables, the base model (Model A), the nested models (Models B–E), and the alternative model (Model F) were constructed separately for comparison using the SEM method. As shown in Fig. 4, Model A added three direct pathways from construal level to three types of CCBs to our theoretical model as the base model. Model B was nested within Model A; it removed these pathways and matched our theoretical model. Model C reduced dispositional awe to CCBs over Model B. Model D reduced construal level and social connectedness serial mediation over Model B. Model E reduced the social connectedness independent mediation path over Model B. Models C–E were nested within Model B and Model A. Model F had no mediating effects: dispositional awe, construal level, and social connectedness all directly affected CCBs as an alternative model.

Model B and the nested models were compared using model fit indices (Model A, Models C–E). The fit indices of Model A and Model B were acceptable (see Table 6), with no significant differences. With age as a control variable, Model B has 416 degrees of freedom, up from 390 in the power analysis section. At this point, we must compare the chi-squared change between the two models, choosing the simple path model if Δχ2 is not significant and the complex path model if Δχ2 is significant (Widaman and Thompson, 2003). The chi-squared change between Model A and Model B was insignificant: Δχ2(3) = 6.61, p = 0.085. Therefore, the simpler Model B was selected. Model B fits better than Models C, D, and E. The chi-squared changes between Model B and Model C (Δχ2(3) = 96.632, p < 0.001), Model B and Model D (Δχ2(133) = 168.962, p = 0.019 < 0.05), and Model B and Model E (Δχ2(1) = 370.537, p < 0.001) were all significant, so the more complex Model B was selected. Since Model B and Model F are non-nested, the smaller AIC and BIC model is better (West et al., 2012). Thus, Model B outperformed Model F in terms of fit. In summary, Model B best modelled the sample data’s variable relationships.

Test of mediation model

Based on our theoretical model (i.e., Model B), we used the ML parameter estimation method and bootstrapping resampling method (5000 samples) to test path coefficients and mediating effects. Figure 5 shows that dispositional awe increased social connectedness (β = 0.602, SE = 0.033, t = 18.242, p < 0.001), confirming H2. Social connectedness positively affected customers’ recommendation behaviour (β = 0.514, SE = 0.085, t = 6.047, p < 0.001), helping behaviour (β = 0.542, SE = 0.074, t = 7.324, p < 0.001), and feedback behaviour (β = 0.530, SE = 0.083, t = 6.386, p < 0.001), confirming H3a–H3c. Dispositional awe positively influenced construal level (β = 0.410, SE = 0.040, t = 10.178, p < 0.001), confirming H5, and construal level positively predicted social connectedness (β = 0.394, SE = 0.033, t = 11.939, p < 0.001), confirming H6. After including the mediating variables of construal level and social connectedness, the direct effects of dispositional awe on recommendation behaviour (β = 0.219, SE = 0.086, t = 2.547, p = 0.011), helping behaviour (β = 0.295, SE = 0.074, t = 3.981, p < 0.001), and feedback behaviour (β = 0.265, SE = 0.084, t = 3.156, p = 0.002) were attenuated, indicating that the mediating variables played their effects. The R2 effect size of construal level, social connectedness, recommendation behaviour, helping behaviour and feedback behaviour were 0.380, 0.620, 0.609, 0.669, 0.649.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. DA, dispositional awe; CL, construal level; SC, social connectedness; RB, CCB recommendation behaviour; HB, CCB helping behaviour; FB, CCB feedback behaviour. Covariances, variances, residual variances, and control variables are omitted for simplicity. Total effect values are shown in parentheses.

Table 7 shows the standardised mediation results. The bootstrap method considers a mediating effect to be significant if the 95% CI of the indirect effect does not include zero (Hayes, 2022). In the first part of the results, the effect of dispositional awe on recommendation behaviour mediated by social connectedness was significant (β = 0.310) because the 95% CI [0.138, 0.474] did not include zero. The effect size PM for the mediation analysis, which is the ratio of the mediating effect to the total effect (Preacher and Kelley, 2011), was 50.6%. These results support H4a. The indirect effect of construal level and social connectedness was significant, β = 0.083, 95% CI [0.038, 0.134], PM = 13.6%, supporting H7a. In the second part, dispositional awe indirectly influenced helping behaviour through social connectedness, β = 0.326, 95% CI [0.194, 0.460], PM = 46.1%, supporting H4b. The indirect effect of construal level and social connectedness was significant, β = 0.088, 95% CI [0.049, 0.132], PM = 12.3%, supporting H7b. In the third part, dispositional awe indirectly influenced feedback behaviour through social connectedness, β = 0.319, 95% CI [0.161, 0.468], PM = 47.6%, supporting H4c. The indirect effect of construal level and social connectedness was significant, β = 0.086, 95% CI [0.044, 0.133], PM = 12.8%, supporting H7c.

Discussion

Research findings and relationship to previous studies

Based on previous research and in line with the prototype model of awe and the elaborated model of awe’s prosocial effects, we developed an integrative model to explore whether and how dispositional awe can influence CCBs. Using data collected from Chinese consumers and testing the hypotheses through structural equation modelling, the results support our hypotheses.

The results suggest that dispositional awe can positively influence three types of CCBs. First, dispositional awe can promote recommendation behaviour, suggesting that individuals who easily or frequently experience awe are more likely to recommend products or services to others. Previous research has shown that awe for a product inspires a willingness to spread positive word-of-mouth (Guo et al., 2018), awe for a brand increases people’s desire to share (Kim et al., 2021), and awe for an artificially intelligent voice assistant promotes consumers’ eWOM (Kautish et al., 2023). Consistent with these studies, our research provides further evidence for the effects of awe on recommendation, sharing, and word-of-mouth, and we extend the existing literature from the perspective of dispositional awe.

Second, dispositional awe promotes helping behaviour, suggesting that individuals high in dispositional awe are more willing to help other customers with their problems. This finding reaffirms the effect of awe on helping behaviour and is consistent with previous research (Chen et al., 2021; Guan et al., 2019; Prade and Saroglou, 2016; Rudd et al., 2012; Stamkou et al., 2023). Our findings also suggest that awe-inspired helping behaviour can manifest not only in donating money, time, travel assistance, or aid to refugees, but also in helping other customers solve product problems and obtain information, thereby contributing new knowledge.

Third, dispositional awe promotes feedback behaviour, suggesting that individuals high in dispositional awe provide more feedback to the company. This feedback suggests that highly awe-prone people are more open and empathetic (Luo et al., 2023; Shiota et al., 2006). They can thus share their views to help companies improve their products. At the same time, this ability to offer advice reflects increased creativity and inspiration. Rudd et al. (2018) found that people in awe are more likely to engage in experiential creativity, and Dai and Jiang’s (2023) study confirmed that awe inspires inspiration. Our study provides further support for such ideas from a dispositional awe perspective.

We also confirmed the independent mediating role of social connectedness between dispositional awe and CCBs. This finding suggests that the more awe people feel in their daily lives, the more connected they feel to the social world, further promoting CCBs. This finding reaffirms the facilitating effect of awe on social connectedness, consistent with previous research (Bai et al., 2017; Van Cappellen and Saroglou, 2012; Zhao and Zhang, 2023). Recent research suggests that awe promotes the tendency to stay close to others through social connectedness, leading to the choice of products most people choose (Yang et al., 2021) and the choice of places most people travel to (Yang et al., 2024). Together with these studies, we contribute to the literature on the downstream effects of consumer behaviour after awe promotes social connectedness. More importantly, our findings support the elaborated model of awe’s prosocial effects. Perlin and Li (2020) argue that awe promotes prosocial behaviour not simply by shifting attention from the self to others but by promoting attention to the interdependent “we”. The mediating role of social connectedness provides direct evidence for this view.

The results confirm the serial mediating effect of construal level and social connectedness. This finding suggests that everyday awe-inspiring experiences broaden people’s thinking, leading to deeper, more abstract, and more comprehensive mental representations that enhance social connectedness and increase the likelihood of CCBs. This finding again provides empirical evidence that awe increases construal level and is highly consistent with several recent studies (Pan and Jiang, 2023; Septianto et al., 2023; Xu and Hu, 2023). Meanwhile, the effect of construal level on social connectedness confirms that the ability to think abstractly broadens thinking horizons (Septianto et al., 2022) and enables people to recognise the common features of the interconnected self and other (Burgoon et al., 2013). Zhang and Zhang (2022) found that individuals with high construal level have greater self-control over intrinsic goals and can more deeply appreciate the importance of social relationships. Our findings are similar to theirs. More importantly, our findings again validate the elaborated model of awe’s prosocial effects. Perlin and Li (2020) argued that awe-inspired awareness of interdependence does not arise solely from attention shifts but may also arise from the transformative power of awe on cognition, motivation, and self-development. Our study’s choice of construal level as a proxy for the cognitive domain supports this view. The finding that awe facilitates cognitive accommodative processing, which in turn triggers psychological changes and behavioural adjustments, is also closely aligned with the prototype model of awe (Keltner and Haidt, 2003).

Theoretical contribution

Compared to previous studies, this study contributes in three ways. First, it extends the study of antecedent variables of customer characteristics that affect CCBs. Previous studies have shown a shift from customer attitude to individual trait factors. For example, Anaza (2014) found that agreeableness and extraversion personality traits helped predict CCBs, and Choi and Hwang’s (2019) study showed that prosocial and proactive personalities positively affected CCBs. Our study continues this line and examines the mechanisms that facilitate CCBs from the perspective of trait factors, supporting the perspective that customer characteristics can affect CCBs (Gong and Yi, 2021). However, previous studies of this type have focused on overly stable personality trait variables, and there is still no research to confirm whether trait emotions can promote CCBs. In contrast, trait emotions are more accessible to development and could have significant theoretical implications for real-world marketing operations. The present study fills this gap precisely by investigating the role of dispositional awe in promoting CCBs, not only responding to Mitrega et al.’s (2022) call to focus on more customer traits but also providing a valuable theoretical addition to the research content in this area.

Second, this study advances research on the consumer behavioural consequences of awe. Awe has become a hot academic topic in consumer behaviour research. Previous research has shown that awe-inspiring product design can increase purchase intention (Septianto et al., 2020). Adding awe to ads increases the persuasiveness of desirability, charity, and green ads (Septianto et al., 2022; Septianto et al., 2023; Yan et al., 2024). Incidental awe increases the likelihood that consumers will choose healthy foods (Cao et al., 2020), reduces impulsive consumption (Zhang et al., 2023), increases consumer forgiveness (Yang and Hu, 2021), and influences aversion to option ambiguity (Ahmmad et al., 2024). Regarding our interest, dispositional awe has been shown to reduce conspicuous consumption tendencies (Hu et al., 2018) and increase socially responsible consumption (Hu, 2023). Together with the studies mentioned above, our research contributes to the extension of awe into consumer behaviour research, which will deepen the understanding of the critical role of awe in everyday human consumption activities. However, to our knowledge, previous research has paid little attention to the role of awe in value co-creation. The value co-creation framework includes many concepts, such as customer participation (CP), customer engagement (CE), and CCBs (Mitrega et al., 2022). Therefore, unlike previous studies, this study points out the positive role of dispositional awe in promoting CCBs, which further broadens the field of awe research and lays the foundation for further research in the future.

Third, building on the prototype model of awe and the elaborated model of awe’s prosocial effects, this study deepens the understanding of how awe promotes prosocial behaviour. Previously, most researchers believed that frequent feelings of awe could lead to a small self or diminished self-awareness (Bai et al., 2017; Piff et al., 2015; Shiota et al., 2007; Stellar et al., 2018), which could promote outward attentional shifts and prosocial behaviours (Stellar et al., 2017). More recently, scholars have focused more on internal factors such as the authentic self (Jiang and Sedikides, 2022) and the self-transcendence meaning of life (Li et al., 2019), suggesting that awe may lead to internal transformations that motivate prosocial behaviour. Using the prototype model of awe and the elaborated model of awe’s prosocial effects as the underlying theory, we again demonstrate the inadequacy of the small-self hypothesis (Perlin and Li, 2020; Tyson et al., 2022; Yuan et al., 2024). On the one hand, the mediating role of social connectedness reflects that awe enhances awareness of the interconnectedness and interdependence between the self and the external world rather than a simple sense of self-insignificance or distraction. On the other hand, the mediation of construal level and social connectedness reflects that this sense of interdependence may arise from the transformative intra-individual cognitive growth brought about by awe’s need for accommodation. In other words, frequent experiences of awe generate a need for accommodation that leads to increased construal level, increased awareness of social connectedness, and ultimately facilitates CCBs. It also suggests that the prosocial effects of awe actually involve a process of internal cognitive growth and a deeper understanding of the interdependence between self and others, in addition to the attentional shifts described in the small-self hypothesis (Zhao et al., 2021). Thus, our findings provide empirical support for Perlin and Li’s (2020) seminal theoretical perspective and contribute to the literature on construal level and social connectedness, intrapersonal and interpersonal mental factors that promote CCBs are also better understood.

Practical implications

Our findings provide further ideas on how companies can market to encourage CCBs. First, marketing should target customer segments with high dispositional awe. Companies should deeply understand this group’s core characteristics and values to effectively target and attract individuals with high dispositional awe. These individuals typically profoundly respect and honour nature, history, culture, and wisdom (Monroy and Keltner, 2023). Therefore, in terms of marketing strategy, companies should emphasise the brand’s alignment with these values and demonstrate the brand’s appeal through storytelling brand narratives. In addition, companies can use existing psychometric tools or questionnaires to assess customer scores on dispositional awe. Companies can invite customers to participate in these measures through online or offline channels and group them based on the results. Customers with high dispositional awe can be matched with surveys or phone interviews. These customer segments are more likely to participate in CCBs.

Next, awe elements should be incorporated into the process of engaging customers. Since frequent awe drives CCBs, companies can use awe in marketing scenarios to nurture and develop customers’ dispositional awe. Companies can create an awe-inspiring brand image through superior product quality, unique brand storytelling, stunning advertising design, and respected brand spokespersons. Companies can also create an awe-inspiring customer experience by hosting special events, offering unique product experiences or creating memorable shopping environments. For example, organising factory tours for customers, demonstrating the power of the technology behind products, or hosting brand-related charity events. Companies should also use social media platforms to publish brand-related, inspirational content, such as design inspirations, innovations, and social responsibility practices. Through well-planned content marketing, customers are inspired to feel awe and encouraged to share and spread this content.

Finally, customers’ high-level construal and social connectedness should be activated. Providing information and experiences at an abstract level is crucial to brand communication and marketing campaigns. Rather than focusing solely on a product’s specific features and uses, companies can communicate the brand’s core values and long-term vision to customers. For example, by telling the brand story and showcasing the company’s culture and mission, customers can understand and identify with the brand on a higher level. In addition, companies need to continue to activate customers’ social connectedness. Companies can encourage customer communication and interaction by setting up online forums, social media groups or offline event platforms. Companies can use the words “we,” “all of us,” “together,” and “joint” in announcements and promotional videos. Companies can also engage in collaborative activities to encourage customers to participate in product design or brand communication decision-making. These will enhance social connectedness and encourage CCBs.

Limitations and future directions

Indeed, this study has several limitations. First, this study uses cross-sectional data. We have tried to clarify the relationships among the variables based on relevant literature and theoretical derivation, but we cannot thoroughly and rigorously reveal their causality. To test the diachronic causal order, a longitudinal design is needed in the future. Second, this study discusses only dispositional awe. It is still unknown whether short-term induced state awe (Yaden et al., 2019) can immediately affect CCBs. This issue can be investigated in the future by designing contextual simulation experiments that accurately measure CCBs. Third, the results indicate that dispositional awe and CCBs still have significant direct effects, suggesting that there may be undiscovered mediating mechanisms between them. Changes in values (Richesin and Baldwin, 2023) and weakening of territoriality (Wang et al., 2022) may also be factors. Fourth, this study lacks moderating variables. Dispositional awe and CCBs may be moderated by customer attitude and firm/brand characteristics. For example, awe may reduce people’s desire for conspicuous consumption (Hu et al., 2018), so the findings of this study may have some limitations in the application of symbolic status brands (e.g., luxury goods). However, the veracity of this claim needs to be confirmed in future empirical studies.

In addition, mobile phones/computers and apparel are the two most numerous industry types of brands we surveyed, both of which are part of the product retail market. At the same time, we collected a small number of brands from the service sector. Such a sample distribution may affect the applicability of our findings. Therefore, in the future, more data could be collected from the service sector to test our findings, and it would be necessary to compare the results obtained from different industries. Finally, our study was collected from a single source, Credamo, and only a Chinese sample. As East Asians are generally more inclined to process information holistically and abstractly (Hong and Lee, 2010), generalising our findings to other cultures should be a caution. Future research is needed to expand the sample sources and to revalidate our findings in other cultural contexts.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study illustrates the positive role of dispositional awe in promoting CCBs. Dispositional awe positively influences the recommendation behaviour, helping behaviour, and feedback behaviour of CCBs. The independent mediating mechanism of social connectedness and the serial mediating mechanism of construal level and social connectedness are also identified to explain this relationship. These findings further support the role of awe in promoting prosociality and extend this prosociality to the reality of customer-company value co-creation, providing the basis for subsequent studies of awe and other co-creative consumer behaviours. The relationship between state awe and value co-creation needs to be explored in future experimental studies.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to ongoing research and analysis. However, the datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

Customers’ perceptions of a company’s product or service are its brand. Thus, when measuring customer citizenship behaviour and brand identification below, we asked the respondents to report the brand they were most familiar with, not the company name. This would encourage the respondents to complete the scale based on their personal experience accurately.

Due to concerns that a lengthy questionnaire would fatigue the respondents, only one attitude variable, brand identification, was selected as a control variable. However, demographic variables significantly associated with CCBs will also be included as control variables in the hypothesis testing model during data analysis.

According to Wu and Wen (2011), item parcelling works for structural models but not measurement models, so we would parcel after measurement model analysis.

References

Ahearne M, Bhattacharya CB, Gruen T (2005) Antecedents and consequences of customer-company identification: expanding the role of relationship marketing. J Appl Psychol 90(3):574–585. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.3.574

Ahmmad K, Harrold M, Howlett E, Perkins A (2024) The effects of awe-eliciting experiences on consumers’ aversion to choice ambiguity. Psychol Market https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21976

Alves H, Ferreira JJ, Fernandes CI (2016) Customer’s operant resources effects on co-creation activities. J Innov Knowl 1(2):69–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2016.03.001

Anaza NA (2014) Personality antecedents of customer citizenship behaviors in online shopping situations. Psychol Mark 31(4):251–263. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20692

Arslan G (2018) Psychological maltreatment, social acceptance, social connectedness, and subjective well-being in adolescents. J Happiness Stud 19(4):983–1001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9856-z

Assiouras I, Skourtis G, Giannopoulos A, Buhalis D, Koniordos M (2019) Value co-creation and customer citizenship behavior. Ann Tour Res 78:102742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102742

Bai Y, Maruskin LA, Chen S, Gordon AM, Stellar JE, McNeil GD, Peng K, Keltner D (2017) Awe, the diminished self, and collective engagement: universals and cultural variations in the small self. J Pers Soc Psychol 113(2):185–209. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000087

Bettencourt L (1997) Customer voluntary performance: customers as partners in service delivery. J Retail 73(3):383–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(97)90024-5

Bullard O, Penner S, Main KJ (2019) Can implicit theory influence construal level? J Consum Psychol 29(4):662–670. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcpy.1101

Burgoon EM, Henderson MD, Markman AB (2013) There are many ways to see the forest for the trees: a tour guide for abstraction. Perspect Psychol Sci 8(5):501–520. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691613497964

Cao F, Wang X, Wang Z (2020) Effects of awe on consumer preferences for healthy versus unhealthy food products. J Consum Behav 19(3):264–276. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1815

Chen R, Bai K, Luo Q (2021) To help or not to help: the effects of awe on residents and tourists’ helping behaviour in tourism. J Travel Tour Mark 38(7):682–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2021.1985041

Chen SK, Mongrain M (2021) Awe and the interconnected self. J Posit Psychol 16(6):770–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1818808

Chen X, Shi W, Gao W (2013) The research of customer citizenship behavior: review and prospect. Bus Manag J 35:189–199. https://doi.org/10.19616/j.cnki.bmj.2013.09.022

Chirico A, Yaden DB (2018) Awe: a self-transcendent and sometimes transformative emotion. In: Lench HC (ed) The function of emotions: when and why emotions help us. Springer International Publishing, Cham, p 221–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77619-4_11

Choi L, Hwang J (2019) The role of prosocial and proactive personality in customer citizenship behaviors. J Consum Mark 36(2):288–305. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-01-2018-2518

Cohen J (1988) Statistical Power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge, New York. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Comrey AL, Lee HB (1992) A first course in factor analysis. Psychology Press, New York. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315827506

Crede M, Harms P (2019) Questionable research practices when using confirmatory factor analysis. J Manag Psychol 34(1):18–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-06-2018-0272

Curth S, Uhrich S, Benkenstein M (2014) How commitment to fellow customers affects the customer-firm relationship and customer citizenship behavior. J Serv Mark 28(2):147–158. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-08-2012-0145

Dai YW, Jiang TL (2023) Inspired by awe: awe promotes inspiration via self-transcendence. J Posit Psychol https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2023.2254737

Dang A, Arndt AD (2017) How personal costs influence customer citizenship behaviors. J Retail Consum Serv 39:173–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.08.012

Danvers AF, Shiota MN (2017) Going off script: effects of awe on memory for script-typical and -irrelevant narrative detail. Emotion 17(6):938–952. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000277

Diebels KJ, Leary MR (2019) The psychological implications of believing that everything is one. J Posit Psychol 14(4):463–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2018.1484939

Dubois D, Bonezzi A, De Angelis M (2016) Sharing with friends versus strangers: how interpersonal closeness influences word-of-mouth valence. J Mark Res 53(5):712–727. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.13.0312

Fredrickson BL (2001) The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol 56(3):218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Gong T, Yi Y (2021) A review of customer citizenship behaviors in the service context. Serv Ind J 41(3-4):169–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2019.1680641

Gordon AM, Stellar JE, Anderson CL, McNeil GD, Loew D, Keltner D (2017) The dark side of the sublime: distinguishing a threat-based variant of awe. J Pers Soc Psychol 113(2):310–328. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000120

Groth M (2005) Customers as good soldiers: examining citizenship behaviors in internet service deliveries. J Manag 31(1):7–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206304271375

Guan F, Chen J, Chen O, Liu L, Zha Y (2019) Awe and prosocial tendency. Curr Psychol 38(4):1033–1041. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00244-7

Guedes IMES, Domingos SPA, Cardoso CS (2018) Fear of crime, personality and trait emotions: an empirical study. Eur J Criminol 15(6):658–679. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370817749500

Guo SY, Jiang LB, Huang R, Ye WL, Zhou XY (2018) Inspiring awe in consumers: relevance, triggers, and consequences. Asian J Soc Psychol 21(3):129–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12215

Hayes AF (2022) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guilford Press, New York

Henderson MD (2011) Mere physical distance and integrative agreements: when more space improves negotiation outcomes. J Exp Soc Psychol 47(1):7–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.07.011

Hong J, Lee AY (2010) Feeling mixed but not torn: the moderating role of construal level in mixed emotions appeals. J Consum Res 37(3):456–472. https://doi.org/10.1086/653492

Hornsey MJ, Faulkner C, Crimston D, Moreton S (2018) A microscopic dot on a microscopic dot: self-esteem buffers the negative effects of exposure to the enormity of the universe. J Exp Soc Psychol 76:198–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2018.02.009

Hu B, Meng L (2022) Understanding awe elicitors in the workplace: a qualitative inquiry. J Manag Psychol 37(8):697–715. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-04-2021-0257

Hu J (2023) Dispositional awe, meaning in life, and socially responsible consumption. Serv Ind J https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2022.2154757

Hu J, Yang Y, Jing F, Nguyen B (2018) Awe, spirituality and conspicuous consumer behavior. Int J Consum Stud 42(6):829–839. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12470

Hu L, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Jak S, Jorgensen TD, Verdam MGE, Oort FJ, Elffers L (2021) Analytical power calculations for structural equation modeling: a tutorial and Shiny app. Behav Res Methods 53(4):1385–1406. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-020-01479-0

Jiang J, Gao BW, Su X (2022) Antecedents of tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior: the perspective of awe. Front Psychol 13:619815. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.619815

Jiang T, Sedikides C (2022) Awe motivates authentic-self pursuit via self-transcendence: implications for prosociality. J Pers Soc Psychol 123(3):576–596. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000381

Kautish P, Purohit S, Filieri R, Dwivedi YK (2023) Examining the role of consumer motivations to use voice assistants for fashion shopping: the mediating role of awe experience and eWOM. Technol Forecast Soc Change 190:122407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122407

Keltner D, Haidt J (2003) Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cogn Emot 17(2):297–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930302297

Kim J, Bang H, Campbell WK (2021) Brand awe: a key concept for understanding consumer response to luxury and premium brands. J Soc Psychol 161(2):245–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2020.1804313

Kock F, Berbekova A, Assaf AG (2021) Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: detection, prevention and control. Tour Manag 86:104330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104330

Lee RM, Draper M, Lee S (2001) Social connectedness, dysfunctional interpersonal behaviors, and psychological distress: testing a mediator model. J Couns Psychol 48(3):310–318. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.48.3.310

Lee RM, Robbins SB (1995) Measuring belongingness: the social connectedness and the social assurance scales. J Couns Psychol 42(2):232–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.42.2.232

Lee RM, Robbins SB (1998) The relationship between social connectedness and anxiety, self-esteem, and social identity. J Couns Psychol 45(3):338–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.45.3.338