Abstract

Knowledge hoarding has gained significant attention as a counterproductive behavior within organizations. This study explores the impact mechanism and boundary condition of organizational inclusion on employee knowledge hoarding through a survey of 366 knowledge employees in China. The findings indicate that psychological security and perceived cohesion mediate the relationship between organizational inclusion and employee knowledge hoarding, and organizational inclusion can inhibit employee knowledge hoarding by increasing their psychological security and perceived cohesion. Learning goal orientation negatively moderates the indirect influence of organizational inclusion on employee knowledge hoarding through psychological security and perceived cohesion. Organizational inclusion practices should be strongly supported and implemented. Especially for individuals with low learning goal orientation, they are more likely to benefit from organizational inclusion and reduce their knowledge hoarding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Researchers have indicated that knowledge is a crucial intangible resource that is essential for the sustained success of employees and organizations (Al Ahbabi et al., 2019; Oliveira et al., 2021). Individuals or groups may take detrimental actions against the organization or others when sharing, transferring, or exploiting knowledge. These counterproductive knowledge behaviors have specific intentions and can have negative impacts on knowledge management and organizational development (Connelly et al., 2012). Knowledge hiding and knowledge hoarding, as typical counterproductive knowledge behaviors, have gained significant attention due to their negative impact on the generation and flow of knowledge within an organization (Shore et al., 2018). In a dynamic environment, these behaviors hinder organizations from effectively utilizing knowledge resources and responding to external challenges. Both knowledge hiding and knowledge hoarding describe the conscious concealment of information and knowledge by individuals in the workplace (Evans et al., 2015). However, knowledge hiding is the refusal to provide information despite being requested by others, and knowledge hoarding primarily refers to information concealment in the absence of a request from others (Connelly et al., 2012; Evans et al., 2015). Knowledge hoarding may stem from unawareness of others’ need for knowledge, rather than from resistance or hostility towards sharing knowledge. Therefore, compared to deliberate knowledge hiding, knowledge hoarding is more likely to be unintentional and can be addressed more easily with intervention (Gagné et al., 2019). Considering this perspective, it is highly practical and beneficial to explore the antecedents behind knowledge hoarding. By investigating the motivations and circumstances that drive individuals to withhold knowledge within organizations, targeted interventions and strategies can also be developed to foster a more collaborative and knowledge-sharing culture.

Current research primarily focuses on conceptualizing knowledge hoarding and comparing the distinctions between different counterproductive knowledge behaviors (Bilginoğlu, 2019; Gonçalves, 2022). Career threat, justice climate, workplace exclusion, and leadership styles have been demonstrated to predict employee knowledge hoarding (Holten et al., 2016; Zhao and Xia, 2017; Zada et al., 2022; Shukla et al., 2024). However, empirical studies on knowledge hoarding are still in their preliminary stages and relatively lacking. In particular, the impact of organizational practices on employee knowledge hoarding is not sufficiently explicit. Exploring and validating the formation mechanisms and boundary conditions of employee knowledge hoarding in an organizational context can help firms to better cope with this counterproductive behavior.

Social exchange theory indicates that people tend to engage in exchange in social interactions. Through exchange, individuals can gain benefits, meet needs, and maintain relationships. Within the organization, employees provide labor and knowledge, while the organization offers compensation, benefits, and development opportunities (Ahmad et al., 2023). This also forms an exchange relationship, and employees will respond to the organization’s policies and practices accordingly. In an environment of change and diversity, when employees perceive a competitive threat, they will tend to protect and accumulate resources. To cope with future demands and uncertainties, knowledge hoarding is more likely to occur (Tran Huy, 2023). With the growing workforce diversity, the need for organizational inclusion has become increasingly vital (Shore et al., 2018). Employees are treated equally regardless of their background or status. Organizations provide employees with opportunities to participate in decision-making and value their contributions (Sabharwal, 2014). When workforce diversity is operated and utilized in a positive way, the accumulation of knowledge and innovation within an organization is facilitated by inclusive culture and practices (Ferdman and Deane, 2014; Shore et al., 2018). Organizational inclusion can enhance the employees’ psychological security by accepting and respecting their different views and backgrounds. Employees will not be penalized or ostracized for voicing different opinions and will have a more positive attitude towards knowledge sharing (Khalid et al., 2020; Hngoi et al., 2023; Dash et al., 2023). Organizational inclusion also strengthens interpersonal harmony within the team and creates higher internal cohesion. Based on the reciprocity principle of Social Exchange Theory, employees are also more willing to give positive rewards and reduce their counterproductive knowledge behavior (Kakar, 2018; Li et al., 2022). Organizations can make diversity a competitive advantage for the organization by creating an inclusive work environment (Ferdman and Deane, 2014). Given the above analysis, organizational inclusion may effectively inhibit the occurrence of knowledge hoarding by enhancing employees’ psychological security and perceived cohesion.

Individuals have significant differences in their goal orientation, which directly influences how they interpret and rely on organizational practices (Stasielowicz, 2019). In line with Social Exchange Theory, individuals participate in social exchanges to satisfy their basic needs, including material, spiritual, and emotional needs. Goal orientation reflects the attitudes and orientations toward goals in learning, working, or other activities. It describes the ways in which individuals pursue goals and their motivations (Lu et al., 2023). Individuals with high learning goal orientation view effort as a means of self-development, and they believe that personal abilities are malleable and can be improved through effort. As a result, they concentrate on acquiring knowledge, developing skills, and studying hard (Dweck and Leggett, 1988; Templer et al., 2022). They have a strong tendency towards self-reliance, demonstrating a willingness to dedicate substantial time and effort to ensure task completion. Moreover, they exhibit resilience when facing obstacles and setbacks, persistently persevering and seeking more effective strategies to overcome challenges (Vandewalle et al., 2019). Individuals with low learning goal orientation are more influenced by external motivation. They have less initiative in learning and are, therefore, more sensitive to the organizational environment, leadership style, and relationships with colleagues (Dweck, 1999). Positive perceptions due to organizational inclusion are more likely to reduce their psychological defenses and actively participate in knowledge interactions (Yoon and Park, 2023). Thus, learning goal orientation may serve as a boundary condition for the influence of organizational inclusion on employee knowledge hoarding. Individuals with lower learning goal orientation are more likely to inhibit their knowledge hoarding due to organizational inclusion.

Considering the above discussion, this study examines the influence mechanism and boundary condition of organizational inclusion on knowledge hoarding grounded in social exchange theory. As knowledge employees are more involved in sharing and exchanging knowledge within the organization, their counterproductive knowledge behaviors can have serious negative impacts on organizational sustainability. In this study, a two-wave survey was conducted on 366 knowledge employees in Chinese companies through convenience sampling. It is hoped to verify the mediating effects of psychological security and perceived cohesion, as well as the moderating effect of learning goal orientation. Finally, the theoretical and practical implications of this study are discussed.

The contribution of this study lies primarily in the comprehensive discussion of two prominent characteristics of modern organizations, diversity, and knowledge explosion, in the broader context. The explanation of the underlying mechanisms that inhibit employee knowledge hoarding from an organizational inclusion perspective explores existing knowledge management research. Additionally, current research on knowledge hoarding predominantly concentrates on conceptual framing, with a relative lack of quantitative research. In line with social exchange theory, the study seeks to enhance the understanding of the impact of organizational inclusion on employee knowledge hoarding by analyzing cross-sectional data on the knowledge of employees. It recognizes the presence of reciprocity in the exchange between organizations and their employees, making a valuable contribution to empirical research on counterproductive knowledge behaviors.

Theoretical basis and research hypotheses

Organizational inclusion and employee knowledge hoarding

Organizational inclusion reflects acceptance of and respect towards the differences of employees. By creating an open, equal, and safe environment, each member can develop his or her full potential and contribute to the success of the organization (Mor-Barak and Cherin, 1998). Specifically, managers express a commitment to promoting diversity, employees are treated equally and have opportunities to participate in organizational decision-making (Sabharwal, 2014). Organizational inclusion promotes flexibility, selectivity, and diversity in the workplace. Employees’ suggestions are valued and utilized; partnerships are built within and between sections (Van den Groenendaal et al., 2023). Consequently, employees are committed to the organization, and potential applicants can be attracted to the organization. Organizations can advocate for inclusive practices and create an inclusive climate so that diversity becomes the organizational competitive advantage (Shore et al., 2018). Current studies indicate that organizational inclusion positively predicts employees’ organizational commitment, perceived well-being, and job satisfaction (Brimhall and Mor Barak, 2018; Shore et al., 2018; Mousa, 2021). In turn, individuals’ perceived stress, anxiety, conflict, and turnover behaviors at the workplace are also decreased within organizations with higher inclusion (Mor Barak, 2015; Shore et al., 2018; Davies et al., 2019). Meanwhile, organizational inclusion enhances communication between leaders and their subordinates, strengthens mutual trust, and contributes to employees’ innovation and performance (Brimhall and Mor Barak, 2018; Liggans et al., 2019; Lister, 2021).

In the traditional view, knowledge is deemed invaluable. People tend to keep it to themselves and limit its spread to others. This practice of accumulating knowledge for personal gain is commonly referred to as knowledge hoarding (Gonçalves, 2022). As typical counterproductive knowledge behaviors, knowledge hiding and knowledge hoarding are often discussed together. Compared to the conscious rejection tendency of knowledge hiding, knowledge hoarding emphasizes the deliberate concealment of knowledge that is not requested by others (Evans et al., 2015). Thus, knowledge hoarding may occur when individuals do not realize that others need to acquire knowledge, or they lack the willingness to share when others do not ask for it (Gagné et al., 2019). In highly competitive work environments where individuals perceive threats to their occupation, they often become self-protective in their approaches to knowledge management, resulting in more knowledge-hoarding behaviors (Shukla et al., 2024). Employees who experience unfair treatment or ostracism in the workplace are more likely to trigger their defense mechanisms and reduce their willingness to share knowledge (Khalid et al., 2020; Aljawarneh et al., 2022). Organizational inclusion emphasizes that managers value workforce diversity. Each employee is recognized as a respected and valued member of the organization (Shore et al., 2018). It helps build trust between employees and their organizations. According to Social Exchange theory, trust is the basis of exchange relationships, and commitment is essential to maintaining them (Ahmad et al., 2023). The organization’s commitment to inclusion makes employees feel respected and trusted, and they are more inclined to share and contribute knowledge in return for the organization’s support and care. It may reduce their incidence of knowledge hoarding (Mor Barak, 2015; Davies et al., 2019). Hypothesis 1 is proposed

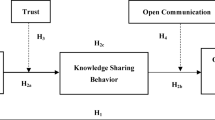

H1: Organizational inclusion is negatively associated with employee knowledge hoarding.

The mediating role of psychological security

Psychological security stems from Maslow’s exploration of the needs hierarchy (Maslow, 1942). When an individual’s safety needs are not met, they will perceive threats and display higher anxiety as a result. Psychological security describes a state in which the individual perceives no harm or threat (Maslow, 1942, Maslow et al., 1945). Individuals with high psychological security usually demonstrate trust and confidence in themselves and others. They have lower anxiety, are willing to build relationships with others, and are more likely to experience happiness in interpersonal interactions (Taormina and Sun, 2015; Yu, 2018). Psychological insecurity in organizations is primarily reflected in job stability and continuity (Keim et al., 2014). Job insecurity occurs when employees are confronted with the possibility of job loss, unrealistic employment expectations, the risk of losing their desired position, or the inability to make changes to the current situation. (Greenhalgh and Rosenblatt, 2010). Current studies have shown that employees’ psychological security in the workplace enhances their organizational identification, which is accompanied by higher work engagement and more positive extra-role behaviors (Ye et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2023).

In an inclusive organization, employees are treated fairly and not discriminated against based on their diversity. Each employee’s contributions are acknowledged and appreciated. A respectful and inclusive work atmosphere ensures that employees are not penalized or ostracized for voicing new ideas or attempting to innovate (Tran Huy, 2023). This contributes to lower workplace anxiety among employees, resulting in higher psychological security (Sabharwal, 2014; Shore et al., 2018). In line with Social Exchange Theory, people exchange to obtain benefits and satisfy needs in social interactions (Ahmad et al., 2023). In the workplace, employees respond behaviorally to positive feelings within the organization. Employees with high psychological security perceive acceptance and respect in their work environment. They believe their opinions and contributions are valued and recognized (Shore et al., 2018). They no longer worry about being exposed to career threats or job insecurity. In return, their tendency to protect knowledge decreases (Khalid et al., 2020; Hngoi et al., 2023). They are more ready to share their knowledge with their coworkers, fostering cooperation and success for the entire team or organization. The likelihood of knowledge hoarding decreases. Organizational inclusion can reduce individuals’ knowledge hoarding by enhancing their psychological security. Hypothesis 2 is proposed.

H2: Psychological security mediates the relationship between organizational inclusion and employee knowledge hoarding.

The mediating role of perceived cohesion

Cohesion describes the overall attraction and commitment of members to their working group, reflecting the desire to work together and contribute to the achievement of shared objectives (Burlingame et al., 2018; Chaudhary et al., 2022). Thus, cohesion reflects the group’s inclination to actively pursue common goals and maintain unity. Perceived cohesion represents a personal assessment of their connection within a group (Greer, 2012; Burlingame et al., 2018). Belonging and morale are important manifestations of perceived cohesion. By recognizing the relationship with their affiliated group, employees can determine their belonging to the group and the morale associated with it (Bollen and Hoyle, 1990; Chaudhary et al., 2022). Higher perceived cohesion is a distinguishing characteristic of high-performing organizations, which is effective in promoting cooperation within the organization. Employees are more likely to demonstrate proactive behaviors regularly, leading to positive work attitudes and increased productivity. Moreover, it also enhances employee job satisfaction and work engagement, fostering recognition and commitment to their roles (Riasudeen et al., 2019; Grossman et al., 2022; Ontrup and Kluge, 2022).

Social Exchange Theory indicates that people tend to establish reciprocal relationships in their interactions. When organization practices make employees feel valued and recognized, they have higher work enthusiasm and respond to those policies positively. Organizational inclusion embodies top-down acceptance of employees’ diversity, emphasizing equal treatment of each organization member and allowing them to make their own decisions (Shore et al., 2018). This not only improves employees’ organizational self-esteem but also can increase members’ mutual trust (Chaudhary et al., 2022; Ontrup and Kluge, 2022). In knowledge management, good interpersonal relationships are the basis for cooperation and sharing. Trust increases employees’ organizational commitment and perceived cohesion, and they are more willing to devote their energy and resources to creating value for the organization. Based on the reciprocity between the organization and the employees, the perceived cohesion can lead to the formation of common goals (Pai and Tsai, 2016). Employees will thus be willing to contribute to the exchange and sharing of information within the organization, thus reducing their knowledge hoarding (Kakar, 2018; Li et al., 2022). Organizational inclusion can reduce individuals’ knowledge hoarding by enhancing their perceived cohesion. Hypothesis 3 is proposed.

H3: Perceived cohesion mediates the relationship between organizational inclusion and employee knowledge hoarding.

The moderating role of learning goal orientation

Individuals have different pursuits and motivations in life, work, or other activities (Che-Ha et al., 2014). Learning goal orientation describes the personal tendency or disposition to engage in learning activities with the primary goal of acquiring new skills and knowledge, rather than focusing on performance outcomes (Dweck, 1986). It reflects a mindset that prioritizes personal growth, career advancement, and new competence development (Dweck and Leggett, 1988). Individuals with high learning goal orientation are more capable of self-regulation (Cellar et al., 2011), and they perceive competencies as malleable and can be improved through effort (Dweck, 1986; Dweck and Leggett, 1988). Thus, high learning goal orientation is often accompanied by higher self-efficacy and intrinsic need fulfillment. They perceive learning as the ultimate objective and prioritize personal empowerment (Yoon and Park, 2023). When confronted with challenges and setbacks, they do not easily give up and persist in exploring methods to find solutions (Templer et al., 2022). They are inclined to adopt problem-focused coping strategies, respond adaptively to difficult tasks, and adjust their behaviors following environmental demands (Dweck and Leggett, 1988). In the workplace, learning goal orientation has been proven to have a significant relationship with feedback seeking, performance adaptation, and proactive behaviors (Stasielowicz, 2019; Lim and Shin, 2021; Mehmood et al., 2023).

In accordance with social exchange theory, individuals obtain rewards and fulfill intrinsic needs through social exchange. When people perceive knowledge and skill development as the desired outcome and view hard work as the path to attain this goal, their behaviors are usually driven by intrinsic motivations (Dweck, 1999; Templer et al., 2022). Individuals with higher learning orientations also show more initiative and openness in their work. They firmly believe that by exerting effort, they can accomplish the set objectives and satisfy their need for personal development (Dweck, 1999; Vandewalle et al., 2019). They are less dependent on the exchange relationship with the organization. On the contrary, individuals with lower learning orientation may be more sensitive to organizational climate, leadership support, and feedback from colleagues, and their behaviors are more dependent on external drivers (Vandewalle et al., 2019). Knowledge hoarding is the conscious and strategic concealment behaviors that are relevant to others but have not been requested (Evans et al., 2015). This behavior does not necessarily indicate intentional withholding but is more likely to be an unconscious or passive response (Gagné et al., 2019). Organizational inclusion that promotes diversity and equality among employees can increase employee job security and cohesion within the organization (Shore et al., 2018), thus reducing knowledge hoarding. Individuals with high learning orientation are more internally driven and less dependent on external circumstances and measures. Their attitude towards knowledge depends more on their self-efficacy and ability to acquire knowledge. However, individuals with low knowledge goal orientation are more likely to benefit from external incentives, and the positive feelings of organizational inclusion may reduce their knowledge hoarding. Therefore, hypotheses 4 and 5 are proposed:

H4: Learning goal orientation negatively moderates the indirect effect of organizational inclusion and employee knowledge hoarding through psychological security.

H5: Learning goal orientation negatively moderates the indirect effect of organizational inclusion and employee knowledge hoarding through perceived cohesion.

The theoretical model is shown in Fig. 1.

Organizational inclusion takes full advantage of the workforce’s diversity, valuing each member’s worth and contribution. By creating a safe and supportive work environment, employees are treated equally and given the opportunity to participate in decision-making (Shore et al., 2018). Organizational inclusion reduces knowledge hoarding among employees by increasing their psychological security and perceived cohesion. Especially for employees with lower learning goal orientation, the inhibitory effect of organizational inclusion on their knowledge hoarding is more significant.

Methods

Procedure and participants

Through a survey of Chinese knowledge employees, this study aims to explore the impact mechanism of organizational inclusion on employee knowledge hoarding, as well as to validate the moderating effect of learning goal orientation. The study was reviewed by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Business at Macau University of Science and Technology. All methods in the study were performed following the Declaration of Helsinki. Before the survey, all respondents were provided with clear information on the aim and procedure of the study. They participated in the survey voluntarily and could terminate it at any time. The collected data was assured to be treated confidentially, with the sole purpose of academic research.

As knowledge employees are provided with more opportunities to use knowledge at the workplace, they are playing an important role in updating and exchanging knowledge within the organization. And their counterproductive knowledge behaviors can have a negative impact on organizational innovation and sustainable development. Therefore, the survey was limited to knowledge employees. Referring to previous studies, this study defines knowledge employees as those who are well educated (with a Bachelor’s degree or higher) and work in sectors related to knowledge use (R&D, consulting, design, etc.) (Reinhardt et al., 2011; Gong et al., 2013). Data collection was facilitated by 30 Doctor of Business Administration students within their organizations. The respondents consisted solely of front-line employees and junior managers from large and medium-sized Chinese organizations (with more than 500 employees), while middle and senior managers were excluded from the survey. The sample has no restrictions on age, gender, region, or industry. The survey lasted from January 2023 to June 2023, and the questionnaire was distributed online through “WJX.com”, China’s largest online survey platform. Respondents are mainly from Guangdong, Guangxi, Hunan, Hubei, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang provinces in China. As Podsakoff et al. (2003) suggested: to minimize the effect of the common method bias, two-wave surveys with a one-month interval were used in this study. Time 1: Data were collected on organizational inclusion, psychological security, and perceived cohesion through convenience sampling. Time 2: Data were collected on learning goal orientation, employee knowledge hoarding, and demographic information by phone number matching.

Out of the 600 questionnaires distributed, 366 were successfully collected and deemed eligible for analysis. This resulted in a valid response rate of 61.0%. 195 (53.3%) of the respondents were men and 171 (46.7%) were women. The gender ratio of the respondents was relatively balanced. Most of the respondents were in the age group of 31–40 (34.4%) and 40–50 (34.7%). All respondents had received higher education. 304 (83.1%) respondents had bachelor’s degrees, 36 (9.8%) respondents had master’s degrees, and 26 (7.1%) respondents had Doctoral degrees. The respondents’ industries were broadly distributed, with a high proportion in energy (30.1%), services (29.8%), information (11.5%), manufacturing (9.6%), and education (6.6%).

Measurement

The survey was conducted with Likert 5-point scales ranging from “completely disagree” to “completely agree”.

Organizational inclusion

The measure was adapted from the scale developed by Sabharwal (2014), which has 23 items and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this scale in the study is 0.957. The specific item is as follows: “My organization involves me in decisions about my job.”

Psychological security

The measure was adapted from the scale developed by May et al. (2004), which has 3 items, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this scale in the study is 0.899. The specific item is as follows: “I’m not afraid to be myself at work.”

Perceived cohesion

The measure was adapted from the scale developed by Bollen and Hoyle (1990), which has 6 items, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this scale in the study is 0.949. The specific item is as follows: “I am enthusiastic about my work within my organization.”

Knowledge hoarding

The measure was adapted from the scale developed by Connelly et al. (2012), which has 4 items and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this scale in the study is 0.951. The specific item is as follows: “I avoid releasing information to others in order to maintain control.”

Learning goal orientation

The measure was adapted from the scale developed by VandeWalle (1997), which has 4 items and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of this scale in the study is 0.856. The specific item is as follows: “I’m willing to select a challenging work assignment so I can learn a lot from it.”

Analytical approach

The data analysis and hypotheses validation were conducted using SPSS 26 and MPLUS 8.6 software. Initially, Mplus 8.6 was employed to perform confirmatory factor analyses to assess the measurement model and scale validity. Subsequently, SPSS 26 was utilized to conduct descriptive statistics and correlation analysis to explore the preliminary relationships among the variables. Hierarchical regressions were then performed to examine the direct effect of organizational inclusion on employee knowledge hoarding. Finally, Mplus 8.6 was employed to test the mediating effect of psychological security and perceived cohesion, as well as the moderating effect of learning goal orientation. Additionally, we compared the boundary differences between high (Mean+1 SD) and low (Mean-1SD) learning goal orientation for the indirect effect of organizational inclusion on employee knowledge hoarding through psychological security and perceived cohesion.

Results

Reliability and validity

The results of scale reliability and validity are presented in Table 1. The item loading of each variable ranges from 0.720 to 0.941, which is greater than the threshold value of 0.50. Internal consistency reliability of each variable ranges from 0.856 to 0.957, which is greater than the threshold value of 0.6. The AVE of each variable ranges from 0.599 to 0.828, which is higher than the threshold value of 0.50. CR of each variable ranges from 0.856 to 0.951, which is higher than the threshold value of 0.70 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2010).

Harman’s single-factor test and confirmatory factor analysis were used to test the common method bias in the study, as suggested by Podsakoff et al. (2003). In Harman’s single-factor test, the variance explained by the first factor was 45.5%, which is lower than the threshold level of 50%. The CFA results indicate that the model fit of the five-factor model (Organizational Inclusion, Psychological Security, Perceived Cohesion, Knowledge Hoarding, Learning Goal Orientation) is acceptable and better (χ2/df = 2.039, RMSEA = 0.053, CFI = 0.976, TLI = 0.971, SRMR = 0.031) than that of other alternative models. Additionally, the model fit of the single-factor model is far from acceptable (χ2/df = 14.622, RMSEA = 0.193, CFI = 0.658, TLI = 0.618, SRMR = 0.100). Therefore, the five-factor model fits the data well, and the common method bias in this study is not significant.

Descriptive statistical analysis

Correlation analyses were conducted with SPSS 26, and the results are presented in Table 2. When controlling the effect of correspondent gender, age, education, and industry, organizational inclusion is positively correlated with psychological security (r = 0.541, p < 0.01) and perceived cohesion (r = 0.713, p < 0.01); Organizational inclusion is negatively correlated with knowledge hoarding (r = −0.478, p < 0.01); Psychological security is negatively correlated with knowledge hoarding (r = −0.688, p < 0.01); Perceived cohesion is negatively correlated with knowledge hoarding (r = −0.603, p < 0.01).

Hypotheses testing

Hypothesis 1 proposed that organizational inclusion is negatively related to employee knowledge hoarding. In Table 3, the result of Model 2 indicates that the direct effect of organizational inclusion on employee knowledge hoarding is significant (−0.474, p < 0.001). Hypothesis 1 is supported.

Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 3 proposed that psychological security and perceived cohesion mediate the relationship between organizational inclusion and employee knowledge hoarding. In Table 4, the results indicate that the indirect effect of organizational inclusion on employee knowledge hoarding through psychological security is significant (b = −0.314, SE = 0.060, 95%CI [−0.440, −0.199]). Organizational inclusion significantly decreases employee knowledge hoarding by increasing their psychological security. Hypothesis 2 is supported. Also, the indirect effect of organizational inclusion on employee knowledge hoarding through perceived cohesion is significant (b = −0.183, SE = 0.062, 95%CI [−0.305, −0.062]). Organizational inclusion significantly decreases employee knowledge hoarding by increasing their perceived cohesion. Hypothesis 3 is supported.

Hypothesis 4 proposed that learning goal orientation moderates the indirect effect of organizational inclusion on employee knowledge hoarding through psychological security. This relationship would be stronger among employees with a lower learning goal orientation, in comparison to those with a higher learning goal orientation. Results in Table 3 indicate that the moderating effect of employee learning goal orientation between psychological security and knowledge hoarding is significant (0.175, p < 0.001). Results in Table 5 indicate that the moderating effect of employee learning goal orientation on the indirect impact is also significant (b = 0.107, SE = 0.029, 95%CI [0.053, 0.159]). In line with our predictions, the indirect impact of organizational inclusion on employee knowledge hoarding through psychological security is stronger when employee learning goal orientation is low (-1SD; b = −0.346, SE = 0.056, 95%CI [−0.462, −0.240]) as compared to the association when employee learning goal orientation is high (+1 SD; b = −0.240, SE = 0.047, 95%CI [−0.333, −0.150]). Hypothesis 4 is supported.

Hypothesis 5 proposed that learning goal orientation moderates the indirect effect of organizational inclusion on employee knowledge hoarding through perceived cohesion. This relationship would be stronger among employees with a lower learning goal orientation, in comparison to those with a higher learning goal orientation. Results in Table 3 indicate that the moderating effect of employee learning goal orientation between perceived cohesion and knowledge hoarding is significant (0.177, p < 0.001). Results in Table 5 indicate that the moderating effect of employee learning goal orientation on the indirect impact is also significant (b = 0.175, SE = 0.049, 95%CI [0.086, 0.252]). In line with our predictions, the indirect impact of organizational inclusion on employee knowledge hoarding through perceived cohesion is stronger when employee learning goal orientation is low (−1SD; b = −0.429, SE = 0.064, 95%CI [−0.554, −0.309]) as compared to the association when learning goal orientation is high (+1 SD; b = −0.254, SE = 0.058, 95%CI [−0.361, −0.134]). Hypothesis 5 is supported.

Conclusions and discussions

Through the survey among 366 knowledge employees in China, this study examines the underlying mechanism of organizational inclusion on employee knowledge hoarding and the moderating effect of learning goal orientation. The findings indicate that psychological security and perceived cohesion have mediating effects on the relationship between organizational inclusion and employee knowledge hoarding, and organizational inclusion can inhibit employee knowledge hoarding by increasing their psychological security and perceived cohesion. Learning goal orientation negatively moderates the indirect influence of organizational inclusion on employee knowledge hoarding through psychological security and perceived cohesion. For individuals with lower learning goal orientations, the inhibitory effect of organizational inclusion on their knowledge hoarding is more pronounced, and they are more likely to benefit from organizational inclusion. All the hypotheses are supported in the study.

Theoretical implications

First, this study verifies that organizational inclusion as a positive organizational practice can inhibit employees’ knowledge hoarding. When they feel valued, involved in decisions, and feel secure at work (Ferdman et al., 2010), organizational inclusion transforms diversity into organizational strengths. By facilitating the exchange and sharing of information within the organization, knowledge-hoarding behaviors are less likely to occur. This is consistent with the findings of previous studies (Holten et al., 2016; Zhao and Xia, 2017; Zada et al., 2022; Shukla et al., 2024). Organizational inclusive practices include giving every employee an equal opportunity to participate in decision-making and valuing members’ contributions. It can reduce employees’ defensiveness by increasing cohesion within the organization and employees’ psychological security (Sabharwal 2014; Shore et al., 2018). In knowledge management, when employees no longer fear that their intangible assets will be plundered, stress reactions due to resource preservation are significantly reduced, and their counterproductive knowledge behaviors are consequently scaled down (Khalid et al., 2020). This finding also reaffirms that an exchange relationship exists between organizations and employees. As indicated in Social Exchange Theory, people tend to establish reciprocal relationships in their interactions, and individuals gain benefits, satisfy needs, and maintain relationships through social exchange (Ahmad et al., 2023). Management practices and work climate can influence employees’ workplace perceptions, and positive feelings will result in fewer negative employee behaviors (Li et al., 2022). Based on the principle of reciprocity, the goodwill that employees perceive from the organization will ultimately be transformed into their proactive behaviors. They are more willing to contribute to the development of the organization. Therefore, this study fully validates the value of Social Exchange Theory in employee knowledge management.

Second, this study examines the boundary conditions under which organizational inclusion has an impact on employee knowledge hoarding. The inhibitory effect of organizational inclusion on employee knowledge hoarding is more significant when individuals have lower learning goal orientations. Individuals with high learning goal orientation have strong intrinsic motivation to improve their learning ability and knowledge. It can stimulate individuals to be self-motivated and they are willing to exert extra effort to achieve their goals (Dweck and Leggett, 1988). They have a more open-minded attitude toward knowledge and view learning as a long-term process, so they are constantly seeking new learning opportunities and challenges. Meanwhile, they will remain inquisitive about knowledge as well as open to different learning experiences. Therefore, they will reduce the anxiety that resources may be plundered by continuously expanding their skills and knowledge (Vandewalle et al., 2019). Given this, individuals with high learning goal orientation have more faith in their efforts and are less dependent on the external environment. Individuals with low learning goal orientation usually avoid new, complex, or challenging tasks and are resistant to new learning opportunities. They lack proactive attitudes and actions because they may doubt their ability to successfully accomplish learning goals. In line with Social Exchange Theory, individuals can satisfy their psychological needs through social exchanges (Ahmad et al., 2023). Due to the lack of intrinsic motivation, employees with low learning goal orientation tend to have more value-efficient organizational policies and harmonious working atmosphere (Dweck, 1999). Through positive interactions and exchanges with the organization, they will reduce negative behaviors at work. Investigating the moderating effect of learning goal orientation offers greater insight into the circumstances in which organizational inclusion impacts employee knowledge behaviors. This research not only reinforces the influential role of individual intrinsic motivation but also identifies potential pathways for mitigating counterproductive knowledge behaviors among employees with low learning goal orientation. The findings are an extension of existing explorations on knowledge hoarding.

Practical implications

The findings have several practical and managerial implications. First, organizational inclusion practices should be strongly supported and implemented. Organizations are now faced with a highly diverse workforce. Organizational inclusion can turn workforce diversity into organizational competitive advantage. Organizational inclusion advocates for hiring employees from different backgrounds and with different experiences. To establish a multicultural and inclusive work environment, the organization should encourage employees to actively share their opinions by providing an open platform for communication. Every employee is treated equally and given the opportunity to participate in decision-making. Organizations should also enhance trust and mutual support among teams by encouraging cooperation and knowledge sharing among employees (Shore et al., 2018). Organizational inclusion improves employees’ psychological security and promotes harmony at work. Second, managers should clarify the difference between knowledge hoarding and knowledge hiding, and adopt different strategies to deal with the two counterproductive knowledge behaviors. Individuals’ knowledge hoarding often precedes knowledge hiding. Individuals do not proactively inform others of the knowledge and information they need without being asked to do so. This could be from not realizing others’ needs or getting used to reacting passively. Knowledge hiding only occurs when explicit refusal persists despite others’ requests (Connelly et al., 2012). The difference in motivation makes the two counterproductive knowledge behaviors differ significantly in their interventions. Organizations should employ different strategies to address these behaviors. Relatively humane and subtle measures may be more appropriate to reduce knowledge hoarding. By creating a positive atmosphere in the workplace and motivating employee initiative, the frequency of knowledge hoarding should decrease. Third, Organizations need to be aware of the impact of employees’ workplace perceptions on their knowledge hoarding. When employees have concerns about their future in the organization, they tend to be protective of their knowledge. Unable to feel work passion and trust in a team, they also resist sharing knowledge (Shukla et al., 2024). Psychological security and perceived cohesion significantly predict an individual’s attitude toward knowledge use. Through inclusive management practices such as treating organization members equally, encouraging employees to participate in decision-making, instant feedback, effective communication, valuing employees’ contributions, and providing necessary resources, employees will be more willing to grow with the organization due to positive workplace feelings. Organizational goodwill can help to alleviate employees’ anxiety and elicit positive responses from them. Finally, organizations should pay more attention to individuals with low learning goal orientations. Their initiative in learning is relatively weak, and they are more susceptible to the influence of the external environment. Unlike individuals with high learning goal orientations, it is difficult for them to reduce anxiety through efforts to accumulate knowledge (Yoon and Park, 2023). They rely more on facilitative organizational practices and a positive working climate. Individuals with low learning goal orientation are more able to benefit from organizational inclusion.

Limitations and future study

Several limitations existed in the study. Firstly, the study used cross-sectional data and relied on self-rating scales. Although this study collected data in two phases to reduce common source bias, a paired survey could be considered in future studies for more accurate measurement, especially on negative behaviors. Secondly, the respondents in this study are all knowledge employees. The attitudes of knowledge employees towards information and knowledge are distinct due to the extensive knowledge demands of their jobs. However, it remains uncertain whether the conclusions drawn from the knowledge employee sample can be applied to non-knowledge workers. Therefore, this study may have external validity issues. Future studies may consider validating the findings in different industries and occupational groups. Third, there are relatively few scale items for knowledge hoarding, psychological security, and learning goal orientation in the study. This can have some impact on the accurate measurement of these variables. In subsequent studies, we will consider using multidimensional and updated scales to gain insight into employees’ psychological security and learning goal orientation. Knowledge hoarding, as a new concern in knowledge management, is currently controversial in its definition and measurement. More comprehensive knowledge hoarding scales are subject to further development and validation in future studies. Finally, research content and scenarios can be further expanded. Current empirical research on knowledge hoarding is limited. Macro environments, organizational policies, team relationships, and personal traits may stimulate or inhibit individual knowledge hoarding. Meanwhile, the substantive effects of knowledge hoarding on individuals and organizations are also unclear. All of them need to be further explored in subsequent studies. In addition, knowledge hoarding and knowledge hiding, as the most typical counterproductive knowledge behaviors, are similar in their manifestations. The comparative study of the inherent differences in their formation mechanisms is also highly valuable.

Data availability

The data in the study (data for statistical analysis and respondent demographic information) is provided via the supplementary file.

References

Ahmad R, Nawaz MR, Ishaq MI, Khan MM, Ashraf HA (2023) Social exchange theory: systematic review and future directions. Front Psychol 13:1015921. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1015921

Al Ahbabi SA, Singh SK, Balasubramanian S, Gaur SS (2019) Employee perception of impact of knowledge management processes on public sector performance. J Knowl Manag 23(2):351–373. https://doi.org/10.1108/jkm-08-2017-0348

Aljawarneh NM, Alomari KAK, Alomari ZS, Taha O (2022) Cyber incivility and knowledge hoarding: does interactional justice matter? VINE J Inf Knowl Manag Syst 52(1):57–70. https://doi.org/10.1108/VJIKMS-12-2019-0193

Bilginoğlu E (2019) Knowledge hoarding: a literature review. Manag Sci Lett 9(1):61–72. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2018.10.015

Bollen KA, Hoyle RH (1990) Perceived cohesion: a conceptual and empirical examination. Soc Forces 69(2):479–504. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/69.2.479

Brimhall KC, Mor Barak ME (2018) The critical role of workplace inclusion in fostering innovation, job satisfaction, and quality of care in a diverse human service organization. Hum Serv Organizations Manag Leadersh Gov 42(5):474–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2018.1526151

Burlingame GM, McClendon DT, Yang C (2018) Cohesion in group therapy: a meta-analysis. Psychotherapy 55(4):384–398. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000173

Cellar DF, Stuhlmacher AF, Young SK, Fisher DM, Adair CK, Haynes S, Riester D (2011) Trait goal orientation, self-regulation, and performance: a meta-analysis. J Bus Psychol 26:467–483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9201-6

Chaudhary M, Chopra S, Kaur J (2022) Cohesion as a cardinal antecedent in virtual team performance: a meta-analysis. Team Perform Manag Int J 28(5/6):398–414. https://doi.org/10.1108/TPM-02-2022-0017

Che-Ha N, Mavondo FT, Mohd-Said S (2014) Performance or learning goal orientation: implications for business performance. J Bus Res 67(1):2811–2820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.08.002

Connelly CE, Zweig D, Webster J, Trougakos JP (2012) Knowledge hiding in organizations. J Organ Behav 33(1):64–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.737

Dash D, Farooq R, Upadhyay S (2023) Linking workplace ostracism and knowledge hoarding via organizational climate: a review and research agenda. Int J Innov Sci 15(1):135–166. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJIS-05-2021-0080

Davies SE, Stoermer S, Froese FJ (2019) When the going gets tough: the influence of expatriate resilience and perceived organizational inclusion climate on work adjustment and turnover intentions. Int J Hum Resour Manag 30(8):1393–1417. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1528558

Dweck CS (1986) Motivational processes affecting learning. Am Psychol 41(10):1040–1048. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.10.1040

Dweck CS, Leggett EL (1988) A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychol Rev 95(2):256–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

Dweck CS (1999) Self-theories: their role in motivation, personality, and development (1st edn.). Psychology Press

Evans JM, Hendron MG, Oldroyd JB (2015) Withholding the ace: the individual-and unit-level performance effects of self-reported and perceived knowledge hoarding. Organ Sci 26(2):494–510. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2014.0945

Ferdman BM, Deane B (2014) Diversity at work: the practice of inclusion. Diversity at work : the practice of inclusion. John Wiley & Sons, San Francisco

Ferdman BM, Avigdor A, Braun D, Konkin J, Kuzmycz D (2010) Collective experience of inclusion, diversity, and performance in work groups. Ram Rev de Adm ção Mackenzie 11:6–26. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-69712010000300003

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800

Gagné M, Tian AW, Soo C, Zhang B, Ho KSB, Hosszu K (2019) Different motivations for knowledge sharing and hiding: The role of motivating work design. J Organ Behav 40(7):783–799. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2364

Gonçalves T (2022) Knowledge hiding and knowledge hoarding: Using grounded theory for conceptual development. Online J Appl Knowl Manag 10(3):6–26. https://doi.org/10.36965/OJAKM.2022.10(3)6-26

Gong Y, Zhou J, Chang S (2013) Core knowledge employee creativity and firm performance: the moderating role of riskiness orientation, firm size, and realized absorptive capacity. Pers Psychol 66(2):443–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12024

Greenhalgh L, Rosenblatt Z (2010) Evolution of research on job insecurity. Int Stud Manag Organ 40(1):6–19. https://doi.org/10.2753/IMO0020-8825400101

Greer LL (2012) Group cohesion: then and now. Small Group Res 43(6):655–661. https://doi.org/10.1177/104649641246153

Grossman R, Nolan K, Rosch Z, Mazer D, Salas E (2022) The team cohesion-performance relationship: a meta-analysis exploring measurement approaches and the changing team landscape. Organ Psychol Rev 12(2):181–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/20413866211041157

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE (2010). Multivariate data analysis a global perspective. New Jersey Pearson Prentice Hall

Hngoi CL, Abdullah NA, Wan Sulaiman WS, Zaiedy Nor NI (2023) Relationship between job involvement, perceived organizational support, and organizational commitment with job insecurity: a systematic literature review. Front Psychol 13:1066734. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1066734

Holten AL, Hancock GR, Persson R, Hansen ÅM, Høgh A (2016) Knowledge hoarding: antecedent or consequent of negative acts? The mediating role of trust and justice. J Knowl Manag 20(2):215–229. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-06-2015-0222

Kakar AK (2018) How do team cohesion and psychological safety impact knowledge sharing in software development projects? Knowl Process Manag 25(4):258–267. https://doi.org/10.1002/kpm.1584

Keim AC, Landis RS, Pierce CA, Earnest DR (2014) Why do employees worry about their jobs? A meta-analytic review of predictors of job insecurity. J Occup Health Psychol 19(3):269–290. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036743

Khalid B, Iqbal R, Hashmi SD (2020) Impact of workplace ostracism on knowledge hoarding: mediating role of defensive silence and moderating role of experiential avoidance. Future Bus J 6(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-020-00045-6

Li N, Yan Y, Yang Y, Gu A (2022) Artificial intelligence capability and organizational creativity: the role of knowledge sharing and organizational cohesion. Front Psychol 13:845277. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.845277

Liggans G, Attoh PA, Gong T, Chase T, Russell MB, Clark PW (2019) Military veterans in federal agencies: organizational inclusion, human resource practices, and trust in leadership as predictors of organizational commitment. Public Pers Manag 48(3):413–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091026018819025

Lim HS, Shin SY (2021) Effect of learning goal orientation on performance: Role of task variety as a moderator. J Bus Psychol 36:871–881. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-020-09705-4

Lister C (2021) Cultural wellbeing index: a dynamic cultural analytics process for measuring and managing organizational inclusion as an antecedent condition of employee wellbeing and innovation capacity. J Organ Psychol 21(4):21–40. https://doi.org/10.33423/jop.v21i4.4542

Lu X, Kluemper D, Tu Y (2023) When does hindrance appraisal strengthen the effect of challenge appraisal? The role of goal orientation. J Organ Behav 44(9):1464–1485. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2749

Maslow AH (1942) The dynamics of psychological security-insecurity. Character Pers Q Psychodiagnostic Allied Stud 10:331–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1942.tb01911.x

Maslow AH, Hirsh E, Stein M, Honigmann I (1945) A clinically derived test for measuring psychological security-insecurity. J Gen Psychol 33(1):21–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.1945.10544493

May DR, Gilson RL, Harter LM (2004) The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J Occup Organ Psychol 77(1):11–37. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317904322915892

Mehmood Q, Hamstra MR, Guzman FA (2023) Supervisors’ achievement goal orientations and employees’ mindfulness: direct relationships and down‐stream behavioral consequences. Appl Psychol 72(4):1593–1607. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps12439

Mor Barak ME (2015) Inclusion is the key to diversity management, but what is inclusion? Hum Serv Organizations Manag Leadersh Gov 39(2):83–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2015.1035599

Mor-Barak ME, Cherin DA (1998) A tool to expand organizational understanding of workforce diversity: Exploring a measure of inclusion-exclusion. Adm Soc Work 22(1):47–64. https://doi.org/10.1300/J147v22n01_04

Mousa M (2021) Does gender diversity affect workplace happiness for academics? The role of diversity management and organizational inclusion. Public Organ Rev 21(1):119–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-020-00479-0

Oliveira M, Curado C, de Garcia PS (2021) Knowledge hiding and knowledge hoarding: a systematic literature review. Knowl Process Manag 28(3):277–294. https://doi.org/10.1002/kpm.1671

Ontrup G, Kluge A (2022) My team makes me think I can (not) do it: team processes influence proactive motivational profiles over time. Team Perform Manag Int J 28(1/2):21–44. https://doi.org/10.1108/TPM-05-2021-0036

Pai P, Tsai HT (2016) Reciprocity norms and information-sharing behavior in online consumption communities: an empirical investigation of antecedents and moderators. Inf Manag 53(1):38–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2015.08.002

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Reinhardt W, Schmidt B, Sloep P, Drachsler H (2011) Knowledge worker roles and actions—results of two empirical studies. Knowl process Manag 18(3):150–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/kpm.378

Riasudeen S, Singh P, Kannadhasan M (2019) The role of job satisfaction behind the link between group cohesion, collective efficacy, and life satisfaction. Psychol Stud 64:401–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-019-00501-6

Sabharwal M (2014) Is diversity management sufficient? Organizational inclusion to further performance. Public Pers Manag 43(2):197–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091026014522202

Shore LM, Cleveland JN, Sanchez D (2018) Inclusive workplaces: a review and model. Hum Resour Manag Rev 28(2):176–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.07.003

Shukla M, Tyagi D, Mishra SK (2024) You reap what you sow”: unraveling the determinants of knowledge hoarding behavior using a three-wave study. J Knowl Manag 28(4):1074–1095. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-10-2022-0856

Stasielowicz L (2019) Goal orientation and performance adaptation: a meta-analysis. J Res Personal 82:103847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2019.103847

Taormina RJ, Sun R (2015) Antecedents and outcomes of psychological insecurity and interpersonal trust among Chinese people. Psychol Thought 8(2):173–188. https://doi.org/10.5964/psyct.v8i2.143

Templer KJ, Kennedy JC, Phang R (2022) Supervisor support and customer orientation: the importance of learning goal orientation in the hotel industry. J Hum Resour Hosp Tour 21(3):482–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332845.2022.2064189

Tran Huy P (2023) High-performance work system and knowledge hoarding: the mediating role of competitive climate and the moderating role of high-performance work system psychological contract breach. Int J Manpow 44(1):77–94. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-06-2021-0331

Van den Groenendaal SME, Freese C, Poell RF, Kooij DT (2023) Inclusive human resource management in freelancers’ employment relationships: the role of organizational needs and freelancers’ psychological contracts. Hum Resour Manag J 33(1):224–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12432

VandeWalle D (1997) Development and validation of a work domain goal orientation instrument. Educ Psychol Meas 57(6):995–1015. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164497057006009

Vandewalle D, Nerstad CG, Dysvik A (2019) Goal orientation: a review of the miles traveled and the miles to go. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 6:115–144. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062547

Wang Y, Han T, Han G, Zheng Y (2023) The relationship among nurse leaders’ humanistic care behavior, nurses’ professional identity, and psychological security. Am J Health Behav 47(2):321–336. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.47.2.12

Ye J, Cardon MS, Rivera E (2012) A mutuality perspective of psychological contracts regarding career development and job security. J Bus Res 65(3):294–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.03.006

Yoon SW, Park JG (2023) Employee’s intention to share knowledge: the impacts of learning organization culture and learning goal orientation. Int J Manpow 44(2):231–246. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-01-2021-0004

Yu ZO (2018) Psychological security as the foundation of personal psychological wellbeing (analytical review). Psychol Russia State Art 11(2):100–113. https://doi.org/10.11621/pir.2018.0208

Zada S, Khan J, Saeed I, Jun ZY, Vega-Muñoz A, Contreras-Barraza N (2022) Servant leadership behavior at workplace and knowledge hoarding: a moderation mediation examination. Front Psychol 13:888761. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.888761

Zhao H, Xia Q (2017) An examination of the curvilinear relationship between workplace ostracism and knowledge hoarding. Manag Decis 55(2):331–346. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-08-2016-0607

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: QHC, TN, and QY; methodology, TN; software, TN; validation, QHC, and TN; formal analysis, TN; investigation, QHC, and QY; resources, QHC; data curation, QHC, and TN; writing—original draft preparation, QHC, TN, and QY; writing—review and editing, QHC and TN; visualization, TN; supervision, TN.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Business at Macau University of Science and Technology (MSB-20230112). The purpose, process, sample, possible harm, and questionnaire of the study were reviewed and approved by the committee on January 15 2023. All research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study before they completed the questionnaire. All respondents were clearly informed about the purpose and process of the study. All participants were fully informed that their anonymity was assured. All respondents were formally informed that the data collected was used only for academic research. All respondents were informed that the study would not cause any harm to the participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, Q., Yan, Q. & Nie, T. Beyond diversity: the impact mechanism of organizational inclusion on employee knowledge hoarding. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1550 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04085-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04085-z