Abstract

There is broad recognition of the essential requirement for collaboration and co-producing knowledge in addressing sustainability crises and facilitating societal transitions. While much effort has focused on guiding principles and retrospective analysis, there is less research on equipping researchers with fit-for-context and fit-for-purpose approaches for preparing and implementing engaged research. Drawing on literature in co-production, collaboration and transdisciplinary science, we present an operationalising framework and accompanying approach designed as a reflexive tool to assist research teams embarking in co-production. This framework encourages critical evaluation of the research contexts in which teams are working, examining the interactions between positionality, purpose for co-producing, contextual and stakeholder power, and the tailoring of co-production processes. We tested this diagnostic approach with four interdisciplinary research teams preparing for co-production in sustainability research in Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO. Data collected during and after these applications, indicate that the approach effectively stimulated a greater understanding and application of a critical co-production lens in the research team’s engagement planning. Workshop discussions revealed opportunities for reflexivity were generated across four learning domains; cognitive, epistemic, normative and relational. We argue that fostering opportunities for reflexivity across these learning domains strengthens teams’ abilities to apply a critical co-production lens, in their engagement work. While this approach has been tested only in the initial preparatory phase for research teams, the framework and diagnostic questions are likely applicable to later work with collaborators and could support iterative re-application of the critical lens at important times during or throughout the life of a project.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transitioning to a more sustainable future requires navigating the complexities of advancing multiple societal outcomes concurrently. As a result, there is an increasing call for knowledge co-production with non-researcher societal actors, also referred to as transdisciplinary research (Bettencourt and Kaur, 2011, Shrivastava et al. 2020), knowledge integration and collaboration sciences (Kauffman and Arico, 2014, Tengö and Andersson, 2022, Mauser et al. 2013, Clark and Harley, 2020). Research agencies and governments are increasingly looking to the social sciences for guidance in science-society interactions (e.g. Jasanoff, 2016, Vertesi and Ribes, 2019, Goldstein and Nost, 2022). Responding to this demand, various approaches have emerged, ranging from overly simplified and process-oriented tools to theoretical platitudes or purist methodological responses often lacking adaptability to contextual nuances or incumbent standpoints (Stirling, 2010). This paper introduces an approach to support interdisciplinary research teams prepare for knowledge co-production with non-researchers.

The rapidly growing literature on knowledge co-production has provided modes of critique, analysis and practice that can help to address sustainability challenges (Chambers et al. 2022, Robinson et al. 2022b, van der Hel, 2016). The origins and applications of co-production span three core strands (Miller and Wyborn, 2020, Wyborn et al. 2019): 1) processes to address complex and contested challenges through collaborative practices (e.g. Berkes, 2009) 2) modes of critical analyses for understanding how knowledge and societal values and goals are created inter-dependently (e.g. Jasanoff, 2004) and, 3) means of coordinating public, private and third sector action to create societal outcomes (e.g. Ostrom and Ostrom, 1977). Its application across different sectors and disciplines has generated diverse meanings (Bandola-Gill et al. 2021) and purposes (Chambers et al. 2021). Here we refer to co-production, after Wyborn et al. (2019 p. 320) as the ‘processes that iteratively bring together diverse groups and their ways of knowing and acting to create new knowledge and practices to transform societal outcomes’. This definition and emerging tradition link the three strands of co-production described above into a form of praxis that is, ideally, reflexive and critical, engaged and empathetic, and oriented by clear and shared societal goals.

Across these distinct lineages of co-production there has been tensions between analytical and instrumental framings of co-production. On one hand, analytical and descriptive modes of co-production seek to critique the relationships between knowledge and power, while instrumental and normative framings look to build and navigate the relationships between knowledge and power (Perry, 2022, Wyborn, 2015, Lövbrand, 2011). Like Perry (2022), we argue for co-production praxis that applies a ‘critical co-production lens’ to engaged work, whereby these dual framings can be complimentary forms of praxis and a means of embedding critical analyses within applied engagements (and vice versa). Here we develop and test an approach that brings this critical, analytical co-production lens to the normative, engaged research of interdisciplinary teams.

Readiness for co-production, especially in the form described above, is a challenge for teams and a significant gap in co-production literature. To our knowledge there is only limited guidance regarding preparatory work for teams embarking in co-production work (Horcea-Milcu et al. 2022) and in building reflexivity through the preparatory processes (Lotrecchiano et al. 2023). Existing literature primarily focuses into co-production principles and approaches (Norström et al. 2020, Pearsall et al. 2022, Fazey et al. 2014, Fleming et al. 2023), or highlights the qualities and capabilities required of researchers engaging in such work (Chambers et al. 2022, Caniglia et al. 2023). West and Schill (2022) highlight the need for researchers to negotiate ethical-political dimensions of diverse research methods in co-produced research. Less attention has been given to the ways interdisciplinary research teams can diagnose possible co-production approaches that fit the contexts and purposes of their engaged research. With transdisciplinary collaboration becoming an increasingly popular means to catalyse societal and economic transitions (Schneidewind et al. 2016), we argue that readiness for critically reflexive co-production is an undervalued capability, and lack of it poses significant risks of failure, capture, or mis-alignment. To learn collectively, and to engage humbly, critically, and effectively with contexts in order to co-produce meaningful outcomes or generate change takes time (Lang et al. 2012, Caniglia et al. 2023). The question of how researcher teams can be best supported to apply a critical co-production lens within engagement work, and to do so relatively rapidly is itself an important empirical question.

We structured this research, and paper, around two questions. Firstly, we asked what might a diagnostic approach to assess readiness for knowledge co-production look like, to support researchers in scoping fit-for-context, fit-for-purpose, outcome-oriented co-production approaches? Fit here is used in a Darwinian sense of being well-suited to the setting. ‘Outcome-oriented’ is a reminder, from the preparatory stage, of the need to generate meaningful outcomes through the co-production endeavours (i.e. that hold relevancy, legitimacy and saliency) for the parties involved, to build/maintain trust in the partnership and, particularly for publicly funded research organisations, with the public. We use the term ‘diagnose’ in the sense of distinguishing, discerning, or distinctively characterising the research context, the research team’s composition and capabilities and potential strategic approaches. To progress such work, we developed a diagnostic approach, including an operationalising framework and workshop activities to support research teams to critically reflect on foundational aspects of co-production for their research. Given the multiple possible options for doing co-production and uncertainties that exist prior to engaging with stakeholders, we intend this framework as a heuristic device to be adaptively applied with and by teams (McKeown et al. 2022).

Secondly, in trialling and testing the heuristic and workshop series process (hereafter ‘approach’), we asked in what ways (in the immediate-short term) did the approach assist research teams with reflexive practice, in planning fit-for-purpose, outcome-oriented co-production within their research? At a practical level, the approach can be used to self-assess and catalyse readiness for engagement within these teams. We examine if the approach has the accessibility, practical utility, and theoretical depth to enable reflexivity and learning to prepare teams for co-production praxis. We applied and tested the approach with interdisciplinary project teams to develop an early iteration of their engagement plans within their projects. Capability developed prior to engagement is anticipated to manifest initially as opportunities for different forms of learning. We use a modified analytical framework based on domains of learning (after Brymer et al. 2018, Baird et al. 2014) to analyse how the approach facilitated learning and reflexivity. These teams were drawn from within CSIRO’s Valuing Sustainability Future Science Platform, an investment to build capacity to address sustainability challenges using transdisciplinary research. Insights from this analysis are discussed, including how the approach facilitates reflexivity via multiple learning domains and rapidly via diagnostic questions that go to the heart of rich threads of learning across project contexts and teams.

From a theoretical context to a diagnostic framework for co-production

In this section we draw on literature reviewed from collaboration and co-production literature in sustainability, science and technology studies, environmental management, learning and transdisciplinary sciences and expert core team perspectives to formulate a methodologically robust but intuitively accessible framework for diagnosing co-production (examined empirically in section 3).

There has been considerable work on identifying guiding principles for co-production in sustainability, to enhance the effectiveness of researcher engagement processes (Norström et al. 2020, Mach et al. 2020, Mills et al. 2022, O’Connor et al. 2019, Fleming et al. 2023, Polk, 2015, Pearsall et al. 2022). While potentially useful for design and practice, such principles remain challenging to implement or embed in team practices and processes, when working across new contexts and with new teams. While efforts to demonstrate principles applied in practice have been made previously (e.g. Robinson et al. 2022a, Maclean et al. 2022), newly formed research teams could benefit from more structured exploration and reflection on foundational elements of co-production within intended research settings and with respect to what forms of engagement could fit their and context.

Co-production research has also focused on identifying co-production approaches or pathways retrospectively. Chambers et al. (2021) present a heuristic, derived from analysis of 32 case studies, evaluating strengths, weaknesses, risks and benefits associated with specific purposes and modes of co-production. Harvey et al. (2019) outline a spectrum of co-production approaches for reflecting on process and outcomes-based spectrums. While these heuristics aid in considering options and associated issues or risks, they are not primarily designed as operationalising devices. Djenontin and Meadow (2018) consider the ‘how to’ of co-production by emphasising design and implementation processes, barriers and enablers, required practices, competencies and ‘variables’ of knowledge co-production. Although these approaches outline processes for co-production design, they leave room for addressing learning and enabling aspects associated with more critical and analytic approaches to co-production.

In terms of enabling reflexive thinking, co-production has faced criticism for not fully realizing its ambitious agenda of facilitating societal transformations. Some scholars argue that it can perpetuate existing incumbencies by insufficiently engaging with critiques of the relationships between knowledge and power (Jagannathan et al. 2020, Turnhout et al. 2020). In some instances, it risks being seen as an end in itself, without careful consideration of whether co-production is in fact the most effective way to achieve goals (Lemos et al. 2018). Turnhout et al. (2020) advocate understanding co-production as both knowledge making and political practice that aims to avoid re-enforcing incumbent unequal power/knowledge dynamics. Such work is central to just and sustainable transformational change (Scoones et al. 2020, Colloff et al. 2021). Researchers and interdisciplinary teams attempting to operationalise the knowledge making and political practice of co-production, can be supported by heuristics and approaches that foster reflexivity from the outset of their projects or programs (Horcea-Milcu et al. 2022).

Operationalising co-production

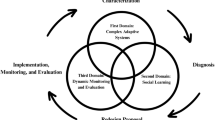

The above trends in critical co-production literature motivated us to develop a framework that could be used as a heuristic device to support research teams in practical engagement planning (Fig. 1, and Table 1). Context is at its core, as central to the research thinking and logic in which every project operates, with unique characteristics that shape decision making, including how and whose knowledge is generated and used. To consider in relation to context, the ‘four P’s’ are used to encapsulate interrelated elements of co-production: Positionality, Purpose, Power and Process (Fig. 1). To explore and apply these elements requires a collective learning environment underpinned by trust, equity, inclusiveness and reflexivity about how processes and arrangements are made and adapted to change (Section 2.2., and Fig. 1). These elements were iteratively defined and refined through engagement with co-production and relevant literatures (Table 1) and building and prototyping processes within the core team and discussed further below.

Context

The truism that ‘context is critical’ creates an imperative to critically consider assumptions and perspectives about the settings in which projects embed. Context is the building block of our framework, influencing all the other elements. Co-production requires grounding research firmly within the context that researchers and their collaborators are working within, and deciding what constitutes context is a shared endeavour with collaborators. Depending on the circumstance, mapping or painting a context can be approached through different lens: a ‘domain of change’ (Fazey et al. 2018), a socio-ecological ‘system’ (Partelow, 2016, Ostrom, 2009, Fabinyi et al. 2014), ‘place-based’ (Switalski, 2020) including a ‘co-constituted place’ (Bawaka Country et al. 2015), an ‘operating environment’ (Leith et al. 2014) or a ‘decision context’ (Gorddard et al. 2016). Characteristics comprising context include ecological, political, institutional, economic, cultural, historical, and spatial, temporal or actor-network boundaries. For co-production inquiries particular attention should be given to understanding the knowledge systems in use and the way particular epistemologies are valued within the system (e.g. McCarthy et al. 2011, Campion et al. 2023) as well as the social, historical and cultural norms of knowledge processes (Wyborn et al. 2019, Schneider et al. 2022).

Open and enquiring discussions of context can reveal what is known, assumed and imagined about the research setting, and therefore link context to positionality of team members. Connecting context to power can be preliminarily unpacked by considering what is at stake, for whom within the setting providing an avenue to explore how different actors might frame the problem the research team is exploring (Leith et al. 2014). In First Nations contexts, for example, particular attention to positionality and power is required given the ongoing structural inequities arising through colonisation (Zurba et al. 2022).

Positionality

Positionality refers here to ‘an individual’s world view and the position they adopt about a research task and it’s social and political context’ (Holmes, 2020). Positionality is fundamentally related to power (McCabe et al. 2021) and could be contained within the Power element in this framework. We keep it distinct and make it the first of the four P’s because it allows teams to reflect on their own power/knowledge/values dynamics. It is also context dependent, as positionality is relational, equally a reflection of how one is perceived by others and how one perceives the world (Secules et al. 2021). Respectfully and safely unpacking divergent views and values within research teams from the outset can assist in building readiness for wider engagement, cooperative processes (Ulrich, 2000) and lay a robust foundation for building trust and fostering constructive co-production action. It can highlight power differentials and biases stemming from social, cultural, ethnic or disciplinary background. Exploring positionalities reflexively and with care, can generate ‘critical-emancipatory’ knowledge as advanced in feminist methodologies (Staffa et al. 2022).

Research teams benefit from discussing individual and collective onto-epistemologies and values shaping problem framing and therefore the purpose for co-producing and the selection of research methodology and methods informing engagement processes. Creating a shared understanding of the different values framing sustainability problems and methodologies, can help reveal underpinning stakes of researchers, countering potential assumptions or biases (Leith et al. 2017).

Reflection on positionality would ideally occur on multiple levels, including individually, within the research team, and within the wider knowledge-action context involving researchers and stakeholders. Individual positionality involves both social and researcher identities, and is influenced by demographic and socio-cultural characteristics and philosophical orientation (e.g. Moon and Blackman, 2014, Moon et al. 2021, Miller et al. 2008) that underpin research. Social and researcher identities intersect generating particular insider-outsider status and exerting knowledge-power asymmetries in research context (e.g. Holmes, 2020, Magaya and Fitchett, 2022). While some aspects of social identity are fixed over time (e.g. race, sex), economic, parental, or age-group status are not, nor is researcher identity static. Researcher identity can shift or continue to evolve over time, with experience or even during the lifespan of a single, impactful, research project.

Practical tools for investigating researcher positionality include positionality statements (Secules et al. 2021), social identity maps (Jacobson and Mustafa, 2019), reflecting on researcher archetypes (Schrage et al. 2023, Chambers et al. 2022) or stances (Hazard et al. 2020). Collective positionality has been explored through tools like Q-methodology (Radinger-Peer et al. 2022, Zabala et al. 2018). Deeper reflection on positionality enables the navigation of ontological differences (e.g. Campion et al. 2023) to combat epistemic injustices and generate epistemic innovation (Ottinger, 2022).

Purpose

Co-production can have various purposes (e.g. Chambers et al. 2021). Yet, choices around these purposes are often made without close attention to researchers’ positionality, power relations among various actors, or an interpretation of context. Agreeing on a purpose for co-producing requires recognising that the problem constitution/framing will quite likely be different depending on individual’s positionality and power asymmetries (interest and influence), which ultimately shapes ‘what is at stake, for whom’ (Leith et al. 2017).

Ideally the research purpose and purpose for co-production would be tightly aligned and co-designed with collaborators (Lang et al. 2012). Collaborators may have divergent interests and generate multiple purposes for doing co-production. Transparently laying out core concerns and motivators will provide the opportunity to identify those purposes which are shared by all, in order to work with common purpose. Having the capacity to listen to others around the knowledge co-production ‘table’ is critical, but more important is paying attention to possible different interpretations about a problem or solutions to it. The level of complexity of the problem and context can also affect agreeing on a goal. This can be influenced by preferences for using certain forms of knowledge or disciplinary approaches. Having a clearly identified and common purpose is critical to underpinning co-production (Norström et al. 2020) and maintaining cohesion and ongoing progress through challenges.

Identifying divergent and shared purposes is challenging where there is a lack of awareness of positionality (e.g. failure to value contribution of diverse or marginalised perspectives or to recognise ontological difference) or power asymmetries among stakeholders. Power asymmetries and practicalities (e.g. previous partner/known entity with certainty in time and capability to contribute) shape who researchers choose to partner with, which also influences the settled upon purpose for co-producing the research. Using multiple context and problem representations which open up and broaden problem formulations to recognise and appreciate asymmetries and tensions in the various values, disciplines and knowledge (Stirling, 2008, Bosomworth et al. 2017) can be useful for teams to explore and build reflexive practice (Pearce and Ejderyan, 2020).

Power

Power is ubiquitous in any research-policy-practice context, manifesting in various forms (Avelino, 2017, Saif et al. 2022). Power relates to exercising some form of control in social contexts, including the ability to make decisions, set agendas and shaping problem-solving approaches. In co-production, it refers to the asymmetries within a research project team or research collectives, including external stakeholders and how the project is situated in the broader societal context (e.g. Pereira et al. 2020, Mahajan et al. 2023). These asymmetries can manifest as different capacities to shape, respond, or act in research and practice contexts (Stirling, 2014).

Recognising that the inherent power imbalances in existing modes of ‘doing’ and ‘knowing’ influence every aspect of research, is crucial for managing and navigating existing power differences, across researchers, collaborators, and end users/those affected. Power dynamics play a pervasive and essential role in all aspects of research and engaged work, influencing funding, contextual understandings, problem definition, research purpose, methodological preferences, among others (Lahsen and Turnhout, 2021, Turnhout et al. 2020). Understanding and acknowledging this is critical to building trust, effective collaborative relationships and governance processes (Wyborn et al. 2019, Turnhout et al. 2020). Based on the work from Avelino (2017), Saif et al. (2022) and McCabe et al. (2021), we explored three forms of power in co-production praxis: i) actor and resource power (including knowledge, relations and influence asymmetries), ii) structural power (political-economic systems shaping decision making processes and how groups interact), and iii) normative and discursive power (as how groups maintain the status quo, or shape discussion based on moulded interests and preferences).

Addressing power involves engaging in the complex political aspects of co-production. This implies recognising that science operates in political settings with competing values, knowledges, and organizations. Particular attention must be given to power sharing arrangements and the ongoing structural inequities arising through colonisation, in First Nation contexts (Zurba et al. 2022, Turnhout et al. 2020). Adopting decolonising methodologies and making explicit space for Indigenous methodologies throughout the research lifespan will be essential to counter these (Hill et al. 2020, Parsons et al. 2016, Ruwhiu et al. 2022). Creating safe spaces for deliberation and contestation, making visible different voices, claims, and interests of all those with a stake in the project are crucial steps (Turnhout et al. (2020). Rather than depoliticising research contexts, research teams and partners should facilitate open dialogue, ensuring communicative competence (O’Connor et al. 2019) and access to necessary resources, to maximise opportunities for engaging and fair distribution of benefits and identification of risks across collaborators.

Addressing power requires unpacking the visible and invisible dynamics influencing how decisions are made, who participates, and how stakeholder relations and interactions are shaped (McIlwain et al. 2023). Engaging with power dynamics can begin with examining an individual’s own role (Positionality), prevailing assumptions and motivations, and preferred knowledge and methods to frame problems (Woroniecki et al. 2020, Muhl et al. 2022). Researchers should scrutinize assumptions about scientific inputs, the influence of their research skillset on research design, output, and long-term outcomes (Fazey et al. 2018) and consider who benefits and who bears potential risks arising from the research. Ärleskog et al. (2021), for example, proposes a model to encourage reflection on power-related premise for co-production and the interactions between discourse, resource and contextual power. Explicitly addressing power dynamics opens options for more equitable engagement (Sharpe et al. 2016, Chambers et al. 2022), manages tensions from dominant narratives, and decision making processes regarding who will use or benefit from (and how) research outputs.

Process

A team’s reflection on context, positionalities, power and purpose provides a foundation for considering effective, tailored and transparent processes for initiating and building external engagement. This encompasses preparing for negotiations on the mechanisms and processes for working effectively together with collaborators, considering governance and decision making processes, (e.g. Hill et al. 2020, Woodward et al. 2020), roles and responsibilities (O’Connor et al. 2019, Reed and Abernethy, 2018, Schrage et al. 2023, Hilger et al. 2021), risk and benefit sharing, knowledge infrastructure (e.g. (Jennings et al. 2023, Robinson et al. 2023), and designing and implementing learning and evaluation processes (Plummer et al. 2022, Perry and Atherton, 2017, Robinson et al. 2022a, Robinson et al. 2021, Fielke et al. 2017). Considering what constitutes an effective collective learning environment requires contextually specific reflection on the pillars of trust, equity, reflexivity and openness and inclusivity (Cvitanovic et al. 2021, O’Connor et al. 2019). While negotiating procedural aspects all needs to be done with collaborators in genuine co-production work, thinking in advance on these aspects is part of the preparedness work. In addition, prior to engagement, interdisciplinary teams can consider the team’s own non-negotiables (resources, timelines, outputs) and institutional requirements, the likely form of engagement (i.e. collaborating, partnering or facilitating an externally led process) and the governance implications (e.g. Hill et al. 2012, Reed et al. 2018), the suite of potentially appropriate methods and the suite of ways to support deliberation and action, including dedication to those ‘virtue ethics’ (Caniglia et al. 2023) of justice, care, courage and humility. While patterns and types of engagement processes may be decipherable (Chambers et al. 2021 etc), each involves a unique tailoring with collaborators (Moser, 2016), given in our context-centred framing.

Applying the framework in a collective learning environment

To examine and deliberate on the elements above requires a safe and effective collective learning environment. Pathways between theorisation and practical action that enable richly informed praxis are notoriously challenging to navigate (Wyborn, 2015, Lövbrand, 2011). Our efforts centred around a methodologically grounded approach to creating a collective learning environment. This requires underpinning foundations of trust, inclusivity, equity and reflexivity.

Building trust requires clarity and reciprocity around roles, responsibilities and expectations through consistent behaviour, open communication, and genuine good will, particularly in efforts to resolve points of disagreement (Ostrom and Walker, 2003). Equity, requires accommodating difference, through deliberation processes and supporting capabilities to engage on equal terms, as part of commitments to fairness/justice (Caniglia et al. 2023, Suboticki et al. 2023, O’Connor et al. 2019). Openness and inclusivity implies embracing and navigating pluralism and the often-subtle power/knowledge dynamics within groups (e.g. Miller et al. 2008), in turn requires awareness of the potential bias and epistemic injustices (e.g. Ottinger, 2022). With reflexivity, we refer to the internal critical enquiry and reflection of examining existing assumptions, norms and values and the collective processes of recognising and learning from past wrongs, anticipating impacts of decisions, rethinking current practices, considering knowledge/power dynamics, with the aim to adapt or change current practices and discourses (Dryzek and Pickering, 2018, Montana et al. 2020, Polk, 2015) and ultimately enable learning (Reed et al. 2010, Brown et al. 2005).

If capacities do not exist for providing these foundational pillars of a safe and effective collective learning environment, then adequate resourcing to put these pillars in place is required. For example, providing adequate time, communicative and translation capabilities and appropriate forms of representation and negotiation are required (Austin et al. 2019, O’Connor et al. 2019, Colloff et al. 2021, Ansari et al. 2023). Finally, a researcher’s ‘practical wisdom and virtue ethics’ (Caniglia et al. 2023) are required in navigating this challenging space. Particularly those of humility, in recognition that, amid the complex and contested sustainability problems, our ignorance is usually greater than our knowledge (Jasanoff, 2022, Jasanoff, 2007) and so requires care for people and the process, and the courage to embark (Caniglia, 2023).

Diagnosing co-production within sustainability science teams

Here we present the methodology and results of empirical work testing our co-production preparedness approach with sustainability science research teams.

Empirical methods

Data collection

To test this co-production framework and the elements within, we developed a primer document of the co-production framework and literature, and a workshop series as an approach through which to explore and iteratively refine the framework, with four Valuing Sustainability Future Science Platform (VS FSP) sustainability science research teams. Each team was working on different sustainability issues across diverse contexts funded through a program that aimed to build transdisciplinary sustainability science capability through research projects. These projects variously focused on aspects of just transitions in agrifood and mining, participatory modelling of thresholds and drivers in socio-ecological systems, sustainability in sea food supply chains and the development of leading indicators of ecosystem functions and change. All project teams comprise members with a variety of disciplinary backgrounds including biophysical, systems, data, and social sciences. Projects were at early stages of planning, all with theories of change but not all with well-defined settings and stakeholders yet identified. We engaged with 32 participants across the four teams, who effectively became collaborators for the dual purposes of enabling and research. The authors are also members of the VS FSP, in a team developing and assessing the methodological scaffolding required to better integrate knowledge systems in sustainability science.

Workshop activities were the same across workshops (Table 2) with tailoring of each workshop drawing on pre-discussion, pre-survey results, and reviews of project theories of change by the core team (first four authors). Immediately after each workshop the core team reflected on the session, considering options to adapt future workshop delivery or content. Researchers were in different regions across Australia, so workshops were delivered online, using an online collaboration whiteboard (hereafter ‘Board’) to enable interaction around boundary objects and capture responses. The primer was designed to help facilitate cognitive learning (new terms and concepts) in advance, and teams also had the opportunity to view and explore the Board pre-loaded with synthesised results to consider ahead of time. Workshops were recorded (except for break out groups for larger Teams in Workshop #2) and transcribed verbatim to capture details of dialogue, learning and reflexive practice.

Capturing learning and feedback on this process was facilitated through a pre-workshop survey, rapid feedback via three online poll questions immediately following each workshop and post-workshop series survey. Pre-workshop surveys asked qualitative questions including researcher disciplinary background and research interests, reasons for engaging in co-production, prior co-production experience, what teams hoped to gain from engaging in the co-production workshops, what successful co-production looks like for the project, markers of success along the way, and what were the biggest challenges identified? Quantitative, likert questions asked how important aspects relating to a) researcher positionality (epistemology) b) reasons for engaging with co-production and c) the outcomes and outputs individuals most valued. Results were aligned with each co-production element, and reflected back to teams via the Board to provide project teams the opportunity to capture reflections in real time. We asked teams to reflect on the synthesised results (both qualitative and quantitative) asking, “this is what we heard, is this right?” and “how important are these differences?” prompting them to clarify and discuss the findings. The immediate post-workshop polls asked: what most resonated, what could we improve on and what was difficult or challenging for you about the workshop today? This rapid feedback capture contributed to minor refinements in our activities and delivery methods within subsequent workshops. The post-workshop series survey reflected on the approach overall, occurred 2–6 months afterwards (11/32 responses; minimum 2 responses across all teams).

Learning domains as an analytical framework for reflexivity

Following from the diagnostic framework explanation above, we argue that transdisciplinary co-production for sustainability science requires deep and reflexive learning (Schneider et al. 2019). Such learning is foundational to understand, proactively engage with, and potentially catalyse shifts in incumbent power/knowledge dynamics within specific contexts through work with those who have a stake in the related sustainability outcomes. The primary precursor in this formulation – reflexive learning – thus becomes an early indicator of success within any approach to embedding co-production within a research team or project. Reflexive learning moments and outcomes associated with any approach might be understood via a ‘learning domains’ framework, modified from Brymer et al. (2018)’s ‘domains of learning’ and Baird et al. (2014)’s ‘typology of learning effects’. Parallels between the learning domains, and social learning loops (e.g. after Reed et al. 2010) can be drawn. Single single-loop learning involves the acquisition or restructuring of knowledge, e.g. cognitive- learning about the consequences of specific actions). Double loop and triple loop learning indicate stronger degrees of reflexivity and could occur across the remaining domains (Table 3), with double-loop learning involving reflection on the assumptions which underlie our actions and triple-loop learning challenging the values, norms and thinking processes that underpin assumptions and actions (Reed et al. 2010).

Data analysis

Analysis was focused on understanding what was effective in promoting learning about co-production as an opportunity for fostering reflexivity across teams in the research process (designing, engaging, defining impact metrics). All individual pre workshop surveys were collated into anonymous results for each team and used to illustrate common and divergent ground and facilitate discussion within the team during workshops. This included qualitative material, thematically synthesised as what ‘we heard’ for the team to reflect upon, and quantitative material, presented in Likert graphs (Fig. 2).

The group discussions were transcribed and analysed (NVivo). Qualitative material from post-workshops surveys and transcribed workshop dialogue were coded in three rounds. Firstly, inductive coding was used to understand what individuals found worked well, or found challenging in relation to the co-production framework or workshop activities. Secondly, deductive coding was used to classify workshop dialogue directly related to co-production elements. Finally, the integrated ‘domains of learning’ (Table 3; cognitive, normative, epistemic or relational) were used to deductively code workshop dialogue (either question and answer exchanges or statements). For the reflexive opportunities to be increasing or enhanced, we would expect to see evidence of multiple or layering of learning domains. Intersections across learning domains and co-production elements (i.e. context, positionality, purpose, power, process/collective learning) were explored through interpretive analyses of coded material to examine where and how opportunities for reflexivity were generated. Moments in the dialogue (e.g. statements or question and answer exchanges) are considered as reflexive moments, rather than evidence of a definitive shift in thinking. The latter would require tracking learning over the long term, throughout the project progression and beyond, which is outside the scope of this analysis. Rather the value is investigating where and how reflexive opportunities arise through this approach.

Empirical results: learning domains and opportunities for reflexivity

4P’s Framework and approach overall

Here we unpack the opportunities for reflexive learnings among sustainability science teams and the project team (as the architects and facilitators of the co-production approach) using the analytical framework of learning domains, cognitive, epistemic, normative and relational. Overall, the approach resonated with respondents in providing their team “a sounding board” (Team D), the opportunity to take a “helicopter view of the processes we’re involved in” (Team A), or to generate the space to consciously pursue reflexive inquiry; “So often we just barrel into projects without asking those questions so consciously. And so I’m finding it quite refreshing to be in a project where we do that, even if it takes time, feels messy, opens boxes before they close.” (Team C).

Post-survey data also showed the approach and framework elements were largely ‘mostly or very useful’ for respondents’ understanding of co-production. All the co-production elements overall were deemed 'somewhat' to 'very useful' (post-workshop series survey). Individually, elements were rated similarly useful and as such there was no alteration made to the context centred 4 P’s framework in response to respondent’s feedback. Qualitatively, respondents valued the interconnections drawn between positionality, purpose and process, the opportunity to explore power, and to understand perspectives within the team. There was also positive commentary on the structure, logic, flow and layout of the workshop, miro board and activities, although language used in the workshop was noted as sometimes difficult). Importantly, post-survey data also referred to the process being useful for having targeted discussions around “purposes and the approaches to achieve those purposes” (Team C) and making aspects usually hidden or less visible aspects more visible. For example, in response to the benefits of undertaking the approach:

“The fact it reveals a set of considerations/dimensions that we don’t always acknowledge explicitly (especially in relation to the 4 P’s), and some approaches for integrating these things into our team discussions and planning.” (post-survey, Team B)

And

“[The co-production framework elements] help give us a language for talking about things that are not always made explicit, and yet are present and influential in decision making and actions. They support the kind of reflections that allow us to be curious about and open to changing our practices.” (post-survey, Team D)

While this rendering visible was referred to in regards the overall approach, it also applies across any of the co-production elements or reflexive learning domains (epistemic, relational, normative).

A key indicator of the creation of a collective learning environment is that some participants engaged deeply with the framework and approach to make recommendations to improve various activities or aspects of the approach. In the spirit of expressing our learning from this we identified the need for recognising diverse learning styles (i.e. suitability of relying on online whiteboards), the value of using relevant applied examples, and the need for explicit and clear guides for learning styles and types, for example “a list of questions to work through within teams could be helpful” (e.g. Workshop #2, Activity 3). For those who found abstract concepts like power and positionality challenging, feedback suggested providing more tangible or worked examples to illustrate concepts. Experience with the collective learning environment brainstorming activity highlighted the importance of taking a solution-oriented approach.

Cognitive learning domain

Overall, cognitive learning here involved teams learning new terms or clarifying understandings of unfamiliar co-production concepts, or engagement methods, or new contextual descriptions or other methods. This form of learning sits at single-loop level of social learning (Baird et al, 2014), but can enable rather than require reflexivity. For example, experience with ‘Power’ conceptually and theoretically was highly varied within and across teams, and the feedback reflected this, ranging from strongly resonating, to finding it conceptually challenging. In some cases, team learning about Power resonated, for example as “Understanding that we all seem to be struggling with questions of power” (Slido 1, Team C) or was something to explore further; “Definitely questions of power and how to manage it. In previous work I’ve not really engaged with power and now that I know more about it, I wish I’d been more attentive to it.” (post-survey, Team B). This suggests cognitive learning, and a precursor for opening up towards epistemic or relational learning domains.

Pre-survey work also provided a means of opening up discussion to understand the diverse modes and purposes of co-production that may exist within the team (Fig. 2). These results, for example, were used to facilitate and unpack researchers’ thoughts on the interconnections between positionality, purpose for co-producing and preferred processes within their team and in doing so unlocked opportunities for learning across all the domains. Comparison across teams also revealed the role of positionality and purpose. Different research orientations across the teams influenced their framing of the research purpose. For example, these ranged from purposes oriented to delivering scientific outputs (realist approaches) to understanding how research outputs facilitate critical engagement with context and transformative change (constructivist approaches). This characterisation and profiling also helped the core team tailor their delivery approach.

The following three learning domains (epistemic, normative and relational) provide opportunities for reflexivity in co-production praxis, as evidenced by these opportunities for reflexive moments opened up during workshop discussion.

Epistemic learning domain

Epistemic learning includes instances where a researcher’s assumptions about the context, problem or the stakeholders are challenged. For example, we observed evidence of epistemic learning in this exchange between a team member and a co-production facilitator, during workshop #2 discussing engagement around potential context-mapping boundary object:

Team member: “I was expecting that everyone would come up with something looking like a network, but actually it was the minority. The majority of people came up with different kind of representations. So, you are right. I didn’t think about that. Maybe even the representation of a network that we take for granted […]. We will need to check whether that is actually the kind of currency that people keep in their head.” [explanation of a particular visual elicitation method]

Facilitator: “[…] so that you can draw out those ways of conceptualising in a visual sense […]”

Team member: “Yeah, it’s a good point.[…] I think in our case […] we kind of took for granted that it is a network so it must be understood as a network. But yeah, it’s worth checking.”

This form of realisation of the disjuncts across the way teams saw the problem was not uncommon, especially in reflections between diversity of positionality and purpose. Where an open and enquiring discussion was flowing among team members, the alignments between positionality of researchers and the purposes of the team’s engagement with stakeholders became more visible. Moreover, the diversity of their perspectives, and the reasons for them, were brought into relief, opening up moments where participants were able to challenge their own assumptions. A precursor to fostering epistemic learning was openness to exploratory and enquiring dialogue among participants (i.e. within teams and with the facilitators). This finding highlights the importance of personal predisposition or capabilities, to foster relational learning as we explain below.

Normative learning domain

Reflexive opportunities in the normative learning domain were frequently generated in discussions on purpose for co-producing. This arose in Workshop 1 where it was discussed directly, and Workshop #2, through building engagement strategies in which teams frequently revisited and questioned the purpose for co-producing. For example, in discussing challenges around representation and risks for particular groups, one researcher returned to seeking clarity of purpose via exploring different potential beneficiaries of the research with the team. This question of “who are we doing this work for and what are our objectives?” reframed the problem of engagement from being largely about getting input into research processes to choosing trajectories of a project that could have different consequences for different groups. The recognition that questions of engagement in trans-disciplinary research are also questions of alignments between purpose and values of prospective participants, highlights a form of normative learning. The early findings here suggest that such normative reconfigurations can be generated when and if groups are able to move flexibly between consideration of power, purpose and their own positionality.

Relational learning domain

Relational learning enabled reflexivity in two ways. Firstly, teams inwardly examined positionality and purpose, distilled improved understanding of other team members’ views, and this led to enquiring discussion about the purpose of the research project within the contextual setting. The opportunity to explore common ground and divergence within teams was widely valued in respondents’ feedback, across all teams, particularly in relation to the spectrum of positionality and purpose within the team (Fig. 2). For example: “I like that it revealed differences within the team, and it created an opportunity to bring curiosity to those differences (without trying to force agreement). It also revealed things we have in common” (Team D). Using the pre-workshop survey results as a boundary object generated create a space for enquiry. However, in core team reflections, we recognised asking ‘are these differences important?’ too early may have closed down this learning opportunity prematurely. Asking teams instead to go with the difference and explore what the minority view may have looked like could have continued to open space for inquiry.

Secondly, evidence of reflexivity in terms of the relational work required by teams considering their engagement work in advance. This included discussion on managing power dynamics, building trust and collaboration networks, generating interest, and appropriate communication tools. Pre-survey responses as to likely indicators of success in team’s co-production praxis, showed all teams considering relational indicators for external stakeholders. In combination with workshop discussion, three of the four teams also referred to the need to develop markers for internal team collaboration. This indicates that research teams are paying attention to relational learning for both within-team processes and those with external collaborators/partners. Finally, the relational learning domain had clear intersections with epistemic and normative learning opportunities.

Layering of learning domains

Frequently a reflexive moment in one learning domain provided a stepping off point into learning opportunities in the other domains. For example, discussions on engagement processes and researcher roles initiated through Process related activities (relational learning domain) prompted reflexive learning moments across normative and epistemic domains for all teams. Discussions across positionality, purpose and process, facilitated by sharing of pre-survey results in workshop #1 (e.g. Fig. 3), opened up discussion as to the role of a scientist in managing power, revealing diverse perspectives and requiring learning across intersecting domains (cognitive, epistemic, normative, relational) (Table 4 below). Respondents in Team A and C, for example, suggested that navigating power or empowering actors was outside of both their purpose for co-production in their project and general remit as scientists/researchers (Table 4), also reflected in their similar positionalities (Fig. 2). Several participants recognised that construction of stakeholder interest/influence diagrams, and its potential to have distributional effects, were exactly the decisions about power that they had previously consider outside of their role. These kinds of linked discussions presented opportunities for reflexivity for the team, across relational, epistemological and normative learning domains. Rather than static moments, they occur in a wider process and demonstrate how such opportunities can be animated by connections between concepts of power, purpose and positionality, enabling articulation of assumptions that are often implicit, and therefore minimally explored.

Timing and team readiness influences capacity for engaging with learning opportunities (across all domains)

There was mixed feedback in relation to the timing of engaging with this diagnosing work across teams. Teams were at different stages of identifying and confirming their research contexts and scope, and in turn the stakeholders they would be engaging with, with Team A relatively settled, but Team B-D at earlier, initial inquiry stages (Table 5). For some, this impacted the effectiveness of activities such as stakeholder interest/influence mapping, and made identifying appropriate engagement processes more challenging. For projects further along, the approach also prompted teams to reflect on decisions already made and the additional opportunities or challenges of making changes to these (if possible) (e.g. Table 5, Slido 2, Team B).

Discussion

Sustainability scientists face the challenge of effectively engaging with plural knowledges, values and power dynamics in formulating interventions that could lead to transformative change (Chambers et al. 2022). Institutional settings and structures, competing priorities, lack of resourcing for monitoring, evaluation and learning processes within projects all create challenges to embedding the sorts of reflexivity that is so often recommended for navigating such contexts (Wyborn et al. 2019, Montana, 2019). We have argued that instigating critical co-production thinking early in the life (Montana et al. 2020) of sustainability science projects relies on creating opportunities for reflexivity (e.g. Feindt and Weiland, 2018) and learning in individuals and teams. We suggest and test an approach to apply critical co-production thinking and generate opportunities for reflexivity within interdisciplinary teams in preparatory work for transdisciplinary research. Drawing on our analysis above, we now discuss how the approach developed in this paper can serve such a purpose, and key ways to improve upon it. In short, we argue that our framework and approach catalyse reflexive opportunities, importantly across multiple learning domains, to support team readiness for co-production.

A diagnostic approach supporting reflexivity praxis

Firstly, we found that the approach did create reflexive learning moments across our projects. Learning opportunities occurred across all four learning domains (epistemic, normative, relational, cognitive) and contributed to building critical co-production capacities within teams. While our approach was sufficiently general to be applied across our research projects, introducing and applying terms and concepts rapidly did occasionally present challenges for coherence of discussion and suggests the need for more explicit focus on concepts and terminology (cognitive learning) initially. We highlight the role of different domains of learning the approach revealed, including prior work (primer) to create a common language (cognitive) before moving to relational and epistemic domains. In this way, teams can clarify purpose, reflect on roles and responsibilities, and challenge normative assumptions.

The approach worked because it was embedded in the real decisions facing teams via practical planning and review of how a team builds out its engagement. Yet the value went beyond the development of an engagement plan. Individuals across all teams highlighted that space and time to undertake critical reflection on both their internal team assumptions and understandings and their intended external engagement activities was valuable, and in some cases contributed to a team culture of reflexivity. While it is broadly recognised that co-production praxis requires this reflexivity to be embedded in iterative learning cycles within researcher teams, researcher-practitioner collectives, and throughout the life of the project, this paper provides rare explicit guidance on how to achieve this (see also Lotrecchiano et al. 2023, Horcea-Milcu et al. 2022). While we designed this framework and associated questions (Table 6) as a scaffold for learning and diagnosis in preparation for co-production, it could also guide ongoing reflexivity for a broader collective, throughout research co-development and co-delivery phases of co-production. This will require future empirical work to test.

The discussions on positionality and power were challenging for some. Scientific training and institutionalised narratives often rest on objectivity and separations of science from politics, power and even policy (Turnhout et al. 2020, Turnhout, 2024), and these narratives held currency for some participants. By encouraging reflexive moments relating to positionality, purpose and the role of researchers and projects, particularly in navigating power, this approach did open up consideration of new positions, less as traditional scientist ‘spectators’ and more as agents within the sustainability system (or interventionists after Fazey et al. 2018). New knowledge then gathered via co-production practice may take the form of purposive action and where critical reflection is an integral part of that action. Similarly, power is normally considered external to the means of ‘justification’ and praxis in science. This framework seeks to counter this and proposes a way to locate power as integral to the approach. The process facilitated what West and Schill (2022 p.7) refer to as ‘surfacing the ethical-political dimensions of research methods’, as inseparable from power and context, as well as by extension, the role of the researcher-actor. This can be a challenging notion to individuals, where it is increasingly recognised as a core competency for researchers (West and Schill, 2022) but also for scientific institutions (Shrivastava et al. 2020). We found that limited language and comfort with expressing identities and linking these to larger societal patterns of power in contexts can be countered via boundary objects, such as interest-influence diagrams, to facilitate more applied discussion, surface assumptions and turn them into questions for enquiry within projects.

We identified broad alignment between learning domains and co-production for sustainability. Norström et al. (2020), for instance, highlight principles (context-based, pluralistic, goal-oriented and interactive) that closely align with learning domains (Fig. 3). For example, the pluralistic principle of co-production arises from engagement with multiple knowledges and prompts epistemic learning opportunities (Fig. 3). The interactive principle arises from multiple actors working together and requires relational learning (Fig. 3). The very nature of co-production for sustainability requires cognitive and normative learning in generating new knowledge with a directionality for sustainable outcomes (Fig. 3). In terms of our framework, epistemic and relational learning were necessary at the intersection of positionality and purpose in order embrace pluralism. Where researchers came to understand epistemic diversity within their team they often did this most effectively through activities that enabled team reflection on positionality, followed by consideration of which stakeholders should be engaged, and why. Cognitive learning appeared necessary to understand contextual characteristics, and methodologies required to generate new knowledge and was particularly highlighted as teams grappled with new contexts, as well as co-production concepts. Relational learning supported interactive enquiry within diverse teams, and often arose during process-focused considerations. Normative learning highlighted values attached to particular methods, roles or processes and can drive innovative sustainability outcomes through consolidation in building shared goals, values and directions or options for activity. The interactivity between modes of learning and the 4Ps framework points to numerous ways that cognitive, relational, epistemic and normative learning can layer, buttress and support each other applying critical co-production thinking to develop readiness for co-production.

Practical transferability and future work

In terms of challenges the teams raised, that of developing and monitoring of markers of success both internally and with external partners, throughout project life, remained one which concerned teams. The co-production process of marker or indicator development provides a concrete example illustrating the influence of power dynamics influencing from conceptualisation, to decision making regarding preferred knowledges from certain groups (positionality and purpose), and operationalised through preferred practices of a subset of stakeholders (process) which can have different implications (distribution of outcomes, risks or benefits) for stakeholders across different scales or sectors (Muhl et al. 2022). Context critically informs indicator development, including how monitoring systems will be financed, who will collect, access, and manage the information, how benefits and risks are distributed and whose interests prevail in decision making (McCabe et al. 2021). An effective co-production approach should embrace learning and monitoring together with collaborators as an inherent part throughout the process, with teams embracing the tailoring of context-specific indicators with collaborators wherever appropriate.

The spectrum of responses regarding team readiness to engage with diagnosing co-production suggest challenges to anticipating co-production ‘readiness’. These will always be individual, team, project and context specific. For example, individuals vary in their comfort with ambiguity, and individuals and teams may or may have limited pre-existing understanding of the context. We particularly noted that uncertainty about place-based contexts or sectors, the scale(s) the projects intended to work at, and identification of stakeholders and their positions (e.g. in terms of interest/influence/affected) made it difficult to meaningful ground discussion of power. These uncertainties were often being explored concurrently and resolve over time with partners, collaborators and/or stakeholders. While these present challenges for the approach, it was clear that reflection could alleviate stumbling blocks for teams. For example, having engagement pathways entrained, or a particular problem framing defined can be avoided through reflexive learning that allows for consideration of plural pathways and contingencies. We suggest that early-stage implementation of this approach should aim to build an enquiring mindset and open-up questions that will inform and be addressed by future engagements and reflections with collaborators. Similarly, an awareness of timing for both entry points and also managing the potentially divergent temporal requirements between researchers and collaborators was found in recent work designed to action transdisciplinary work (Horcea-Milcu et al. 2022).

Additionally, there were some parts of the approach which consistently resonated with participants and focusing on these aspects may save time, particularly for those less familiar with critical co-production thinking (e.g. trained in more deductive and positivist orientations). We have condensed these into a list of questions intended as prompts to initiate and open up thinking, rather than as a definitive ‘check list’ (Table 6).

Future work could test the application of these diagnostic prompt questions in conjunction with the framework. Given the approach was tested with interdisciplinary teams prior to and in preparation for, their engagement, future work exploring the application of the approach with engaged transdisciplinary teams would be valuable. Additionally, our approach could be complemented by other methods to encourage reflexivity at various stages or by researchers occupying various roles. For example, reflexive monitors can play diverse, context-dependent roles (devil’s advocate, critical enquirer, mediator) in fostering team reflexivity throughout monitoring and evaluation activities (Fielke et al. 2017, Rijswijk et al. 2015). Methods such as Q-methodology can be used to reveal different values or perspectives about a problem (Radinger-Peer et al. 2022, Zabala et al. 2018), which could help unpack positionality and purpose within research teams. It can also be used to identify and track changes in individual narratives over time which might support process-related evaluation over the longer-term (Charli-Joseph et al. 2023). Scenario planning can also increase reflexivity about power and process (Rutting et al. 2024). However, is important to recognise the feasibility of complementary approaches, depending on context requirements, resources and capabilities. For instance, applying a Q-method is time demanding, and requires careful development and selection of statements to avoid bias.

The critical co-production lens embedded in the applied approach in this paper is attuned in important ways that other ‘end-user’ or engagement focused frameworks are not (for example, see marketing or design thinking) (Tidd and Bessant, 2020, Johansson‐Sköldberg et al. 2013). It is deployed to encourage reflexivity pertaining to societal or stakeholder-specific equity concerns, arising from knowledge-politic interactions. As such, this approach can assist researchers in navigating the tension between multiple agendas, institutional practices, diverse values, and provide opportunities to weave and embed critical reflection on equitable research praxis in terms of both processes and outcomes. This kind of thinking is not rapidly or easily arrived at (nor via a simple checklist approach, though these can be helpful to initiate critical co-production thinking), but rather through commitment to ongoing learning and building of capabilities, including those practical ethics and researcher capabilities described by Caniglia et al. (2023).

Conclusion

This research sought to enable interdisciplinary teams to rapidly apply a critical co-production lens in preparation for co-production approaches that are fit for context and purpose. We developed a context centred ‘4 P’s framework comprising essential and interconnected co-production elements: context, positionality, purpose, power and process, fostered via a collective learning environment, underpinned by pillars of trust, equity, reflexivity, openness and inclusivity. The approach was explored with four sustainability research teams through a workshop series designed to support the diagnosis of appropriate co-production approaches and reflexive practice in preparing for engaging with co-production. Applying a learning framework, our analysis found the approach supported opportunities for learning and reflexivity by creating interactions across four learning domains: cognitive, epistemic, normative and relational and often prompted through intersecting co-production elements (for example, positionality, purpose, process). Learning domains and their intersection also aligned conceptually with the nature and characteristics of knowledge co-production in sustainability science. Team readiness and stage of problem framing/project development including understanding of context and stakeholders, were factors in the effectiveness of the approach. Engaging with power and positionality was also challenging for some individuals and teams, and concrete, relevant examples and activities were required to support cognitive learning of co-production concepts where these were new or unfamiliar.

Approaches such as these invest time and capacity in reflexivity and learning processes, which is a critical aspect and capability for co-production in transdisciplinary and sustainability science researchers. Institutional support and processes are critical to embed and mainstream co-production thinking and approaches. Embedded co-production thinking in researcher praxis also requires personal researcher commitment to continual learning and reflexivity, as projects span diverse contexts, comprise new teams and an individual’s experience, skillsets and networks continue to change over their research life.

Data availability

The data of this research consists of interview transcripts, qualitative and quantitative (provided) survey responses. The qualitative datasets, generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to commitments made to research participants (as required by social ethics process) that their contributions would be confidential and only accessed by the research team. The themes derived from the analysis of surveys and workshop material are available on request.

References

Ansari D, Schönenberg R, Abud M, Becerra L, Brahim W, Castiblanco J, De La Vega-Leinert AC, Dudley N, Dunlop M, Figueroa C, Guevara O, Hauser P, Hobbie H, Hossain MAR, Hugé J, Janssens De Bisthoven L, Keunen H, Munera-Roldan C, Petzold J, Rochette AJ, Schmidt M, Schumann C, Sengupta S, Stoll-Kleemann S, Van Kerkhoff L, Vanhove MPM, Wyborn C (2023) Communicating climate change and biodiversity loss with local populations: exploring communicative utopias in eight transdisciplinary case studies. UCL Open Environ. 5:e064

Ärleskog C, Vackerberg N, Andersson A-C (2021) Balancing power in co-production: introducing a reflection model. Humanities Soc. Sci. Commun. 8:108

Austin B, Robinson C, Mathews D, Oades D, Wiggin A, Dobbs R, Lincoln G, Garnett S (2019) An Indigenous-led approach for regional knowledge partnerships in the Kimberley region of Australia. Hum. Ecol. 47:577–588

Avelino F (2017) Power in Sustainability Transitions: Analysing power and (dis)empowerment in transformative change towards sustainability. Environ. Policy Gov. 27:505–520

Baird J, Plummer R, Haug C, Huitema D (2014) Learning effects of interactive decision-making processes for climate change adaptation. Glob. Environ. Change 27:51–63

Bandola-Gill J, Arthur M, Leng RI (2021) What is co-production? Conceptualising and understanding co-production of knowledge and policy across different theoretical perspectives. Evid Policy: J Res, Debate Pract 19(2):275–298

Bawaka Country, Wright S, Suchet-Pearson S, Lloyd K, Burarrwanga L, Ganambarr R, Ganambarr-Stubbs M, Ganambarr B, Maymuru D (2015) Working with and learning from Country: Decentring human author-ity. Cultural geographies 22:269–283

Berkes F (2009) Evolution of co-management: Role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. J. Environ. Manag. 90:1692–1702

Bettencourt LM, Kaur J (2011) Evolution and structure of sustainability science. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 108:19540–19545

Bosomworth K, Leith P, Harwood A, Wallis PJ (2017) What’s the problem in adaptation pathways planning? The potential of a diagnostic problem-structuring approach. Environ. Sci. Policy 76:23–28

Brown VA, Dyball R, Keen M, Lambert J, Mazur N (2005) The reflective practitioner: practising what we preach. Social Learning in Environmental Management. Routledge

Brymer ALB, Wulfhorst J, Brunson MW (2018) Analyzing stakeholders' workshop dialogue for evidence of social learning. Ecol Soc 23(1):42

Campion OB, West S, Degnian K, Djarrbal M, Ignjic E, Ramandjarri C, Malibirr GW, Guwankil M, Djigirr P, Biridjala F, O'ryan S, Austin BJ (2023) Balpara: a practical approach to working with ontological difference in indigenous land & sea management. Soc Nat Resour 37(5):695–715

Caniglia G, Freeth R, Luederitz C, Leventon J, West SP, John B, Peukert D, Lang D, Von Wehrden H, Martín-López B (2023) Practical wisdom and virtue ethics for knowledge co-production in sustainability science. Nat Sus 1–9

Caniglia G, Freeth R, Luederitz C, Leventon J, West SP, John B, Peukert D, Lang DJ, von Wehrden H, Martín-López B, Fazey I, Russo F, von Wirth T, Schlüter M, Vogel C (2023) Practical wisdom and virtue ethics for knowledge co-production in sustainability science. Nat Sustain 6:493–501

Chambers JM, Wyborn C, Ryan ME, Reid RS, Riechers M, Serban A, Bennett NJ, Cvitanovic C, Fernández-Giménez ME, Galvin KA (2021) Six modes of co-production for sustainability. Nat. Sust 4:983–996

Chambers JM, Wyborn C, Klenk NL, Ryan M, Serban A, Bennett NJ, Brennan R, Charli-Joseph L, Fernández-Giménez ME, Galvin KA (2022) Co-productive agility and four collaborative pathways to sustainability transformations. Glob. Environ. change 72:102422

Charli-Joseph L, Siqueiros-García JM, Eakin H, Manuel-Navarrete D, Mazari-Hiriart M, Shelton R, Pérez-Belmont P, Ruizpalacios B (2023) Enabling collective agency for sustainability transformations through reframing in the Xochimilco social–ecological system. Sust Sci. 18:1215–1233

Clark WC, Harley AG (2020) Sustainability Science: Toward a Synthesis. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 45:331–386

Colloff MJ, Gorddard R, Abel N, Locatelli B, Wyborn C, Butler JRA, Lavorel S, Van Kerkhoff L, Meharg S, Múnera-Roldán C, Bruley E, Fedele G, Wise RM, Dunlop M (2021) Adapting transformation and transforming adaptation to climate change using a pathways approach. Environ. Sci. Policy 124:163–174

Cvitanovic C, Shellock RJ, Mackay M, Van Putten EI, Karcher DB, Dickey-Collas M, Ballesteros M (2021) Strategies for building and managing ‘trust’ to enable knowledge exchange at the interface of environmental science and policy. Environ. Sci. Policy 123:179–189

Djenontin INS, Meadow AM (2018) The art of co-production of knowledge in environmental sciences and management: lessons from international practice. Environ. Manag. 61:885–903

Dryzek JS, Pickering J (2018) The politics of the Anthropocene, Oxford University Press

Fabinyi M, Evans L, Foale SJ (2014) Social-ecological systems, social diversity, and power: insights from anthropology and political ecology. Ecol Soc 19(4):28

Fazey I, Fazey JA, Fazey DM (2005) Learning more effectively from experience. Ecol Soc 10(2):4

Fazey I, Bunse L, Msika J, Pinke M, Preedy K, Evely AC, Lambert E, Hastings E, Morris S, Reed MS (2014) Evaluating knowledge exchange in interdisciplinary and multi-stakeholder research. Glob. Environ. Change 25:204–220

Fazey I, Schäpke N, Caniglia G, Patterson J, Hultman J, Van Mierlo B, Säwe F, Wiek A, Wittmayer J, Aldunce P, Al Waer H, Battacharya N, Bradbury H, Carmen E, Colvin J, Cvitanovic C, D’Souza M, Gopel M, Goldstein B, Hämäläinen T, Harper G, Henfry T, Hodgson A, Howden MS, Kerr A, Klaes M, Lyon C, Midgley G, Moser S, Mukherjee N, Müller K, O’Brien K, O’Connell DA, Olsson P, Page G, Reed MS, Searle B, Silvestri G, Spaiser V, Strasser T, Tschakert P, Uribe-Calvo N, Waddell S, Rao-Williams J, Wise R, Wolstenholme R, Woods M, Wyborn C (2018) Ten essentials for action-oriented and second order energy transitions, transformations and climate change research. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 40:54–70

Feindt PH, Weiland S (2018) Reflexive governance: exploring the concept and assessing its critical potential for sustainable development. Introduction to the special issue. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 20:661–674

Fielke S, Nelson T, Blackett P, Bewsell D, Bayne K, Park N, Rijswijk K, Small B (2017) Hitting the bullseye: Learning to become a reflexive monitor in New Zealand. Outlook Agriculture 46:117–124

Fleming A, Bohensky E, Dutra LXC, Lin BB, Melbourne-Thomas J, Moore T, Stone-Jovicich S, Tozer C, Clarke JM, Donegan L, Hopkins M, Merson S, Remenyi T, Swirepik A, Vertigan C (2023) Perceptions of co-design, co-development and co-delivery (Co-3D) as part of the co-production process – Insights for climate services. Clim. Serv. 30:100364

Freeth R, Caniglia G (2020) Learning to collaborate while collaborating: advancing interdisciplinary sustainability research. Sust Sci. 15:247–261

Goldstein J, Nost E (2022) The nature of data: Infrastructures, environments, politics, University of Nebraska Press

Gorddard R, Colloff MJ, Wise RM, Ware D, Dunlop M (2016) Values, rules and knowledge: Adaptation as change in the decision context. Environ. Sci. Policy 57:60–69

Greenaway A, Hohaia H, Le Heron E, Le Heron R, Grant A, Diprose G, Kirk N, Allen W (2022) Methodological sensitivities for co-producing knowledge through enduring trustful partnerships. Sust Sci. 17:433–447

Harvey B, Cochrane L, Van Epp M (2019) Charting knowledge co‐production pathways in climate and development. Environ. Policy Gov. 29:107–117

Hazard L, Cerf M, Lamine C, Magda D, Steyaert P (2020) A tool for reflecting on research stances to support sustainability transitions. Nat. Sust 3:89–95

Hilger A, Rose M, Keil A (2021) Beyond practitioner and researcher: 15 roles adopted by actors in transdisciplinary and transformative research processes. Sust Sci. 16:2049–2068

Hill R, Grant C, George M, Robinson CJ, Jackson S, Abel N (2012) A Typology of Indigenous Engagement in Australian Environmental Management Implications for Knowledge Integration and Social-ecological System Sustainability. Ecol Soc 17(1):23

Hill R, Walsh FJ, Davies J, Sparrow A, Mooney M, Council CL, Wise RM, Tengö M (2020) Knowledge co-production for Indigenous adaptation pathways: transform post-colonial articulation complexes to empower local decision-making. Glob. Environ. Change 65:102161

Holmes AGD (2020) Researcher Positionality–A Consideration of Its Influence and Place in Qualitative Research–A New Researcher Guide. Shanlax Int. J. Educ. 8:1–10

Horcea-Milcu A-I, Leventon J, Lang DJ (2022) Making transdisciplinarity happen: Phase 0, or before the beginning. Environ. Sci. Policy 136:187–197

Jacobson D, Mustafa N (2019) Social Identity Map: A Reflexivity Tool for Practicing Explicit Positionality in Critical Qualitative Research. Int J Qual Methods 18:1–12

Jagannathan K, Arnott JC, Wyborn C, Klenk N, Mach KJ, Moss RH, Sjostrom KD (2020) Great expectations? Reconciling the aspiration, outcome, and possibility of co-production. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustainability 42:22–29

Jasanoff S (2004) States of Knowledge: The Co-production of Science and the Social Order. Routledge, London and New York

Jasanoff S (2007) Technologies of humility. Nature 450:33–33

Jasanoff S (2016) The ethics of invention: Technology and the human future, WW Norton & Company

Jasanoff S (2022) Humility in the Anthropocene. Time, Climate Change, Global Racial Capitalism and Decolonial Planetary Ecologies. Routledge

Jennings L, Anderson T, Martinez A, Sterling R, Chavez DD, Garba I, Hudson M, Garrison NA, Carroll SR (2023) Applying the ‘CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance’to ecology and biodiversity research. Nat. Ecol. Evolution 7:1547–1551

Johansson‐Sköldberg U, Woodilla J, Çetinkaya M (2013) Design thinking: past, present and possible futures. Creativity Innov. Manag. 22:121–146

Kauffman J, Arico S (2014) New directions in sustainability science: promoting integration and cooperation. Sust Sci. 9:413–418

Lahsen M, Turnhout E (2021) How norms, needs, and power in science obstruct transformations towards sustainability. Environ. Res. Lett. 16:025008

Lang DJ, Wiek A, Bergmann M, Stauffacher M, Martens P, Moll P, Swilling M, Thomas CJ (2012) Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: practice, principles, and challenges. Sust Sci. 7:25–43

Leith P, O’Toole K, Haward M, Coffey B, Rees C, Ogier E (2014) Analysis of operating environments: a diagnostic model for linking science, society and policy for sustainability. Environ. Sci. Policy 39:162–171