Abstract

In museums’ dynamic and culturally rich environments, employee morale and productivity are crucial for achieving organizational goals. However, employees’ perception of organizational politics can undermine these objectives. Hence, this study investigates the buffering role of authentic leadership in mitigating perceptions of organizational politics and its subsequent effects on organizational citizenship behavior (OCBI and OCBO) and task-oriented performance among museum employees. This research involved 436 employees across six public sector museums in Pakistan, including supervisors and their immediate subordinates. Data were collected in four waves and analyzed using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). The findings indicate that perceptions of organizational politics significantly negatively influence both organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBI and OCBO) and task-oriented performance. However, authentic leadership buffers these negative effects, significantly reducing perceptions of organizational politics and positively correlated with enhanced task-oriented performance and citizenship behavior. This study highlights the crucial role of authentic leadership in moderating the adverse impacts of organizational politics, fostering a positive work environment in museums, and enhancing both employee productivity and organizational outcomes. The insights from this research offer valuable implications for museum leaders aiming to enhance organizational performance through effective leadership practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past three decades, leadership studies have witnessed a paradigm shift from traditional, leader-centric models to more interactive and relational approaches emphasizing the dynamic interplay between leaders and followers (Solinger et al. 2020). Amidst this evolution, authentic leadership has emerged as a prominent construct, focusing on genuinely expressing a leader’s values and behaviors, which resonate deeply with followers’ needs and aspirations (Gardner et al. 2011). Despite growing evidence of its positive impacts on follower outcomes (Gardner et al. 2021), a critical gap remains in understanding how authentic leadership functions within specific organizational contexts, particularly those characterized by complex power dynamics and perceived organizational politics.

To address this gap, our study draws on two foundational theories: Social Exchange Theory (SET) and Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory. Social Exchange Theory, rooted in the seminal work of Blau (1964), posits that human relationships are governed by the principle of reciprocity, where individuals engage in exchanges with others based on the expectation of mutual benefits. This manifests as a cycle of giving and receiving within the workplace, where positive interactions between leaders and followers foster trust, commitment, and cooperation (Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005). Authentic leadership, characterized by transparency, integrity, and relational authenticity, aligns perfectly with the principles of SET, as it nurtures positive exchanges and enhances the quality of leader–follower relationships (Luu, 2020). On the other hand, the Conservation of Resources Theory (COR), introduced by Hobfoll (1989), complements SET by focusing on the conservation and protection of personal resources. It posits that individuals strive to acquire, maintain, and defend resources critical to their well-being, such as time, energy, and social support. In high-politics environments, where self-serving influencing tactics permeate decision-making processes, employees may experience resource depletion, leading to stress, disengagement, and reduced performance (Hochwarter et al. 2020). This perspective highlights the importance of understanding how leadership styles can mitigate or exacerbate the resource loss spiral triggered by organizational politics.

Recent studies have shed light on the role of cultural and contextual factors in shaping the effectiveness of authentic leadership. Kelly (2023) demonstrated that involvement culture can serve as a boundary condition for authentic leadership, affecting its impact on workplace spirituality. Akuffo and Kivipõld (2021) explored the mediating role of the political environment in the relationship between authentic leadership and collective thriving, suggesting that the nature of the organizational context influences leadership outcomes. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2022) underscored the importance of organizational culture in explaining variations in authentic leadership manifestation.

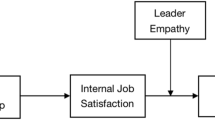

Despite these advances, there is a dearth of research exploring the specific mechanisms through which authentic leadership can buffer the negative effects of perceived organizational politics on employee outcomes. Our study aims to fill this gap by investigating how authentic leadership moderates the relationship between perceived organizational politics and employee task-oriented performance and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) in the museum industry (see Fig. 1). By focusing on museums, we contribute to the literature by examining leadership dynamics within a culturally rich and socially significant context, offering novel insights into the practical application of leadership theories.

Our primary objective is to explore the moderating role of authentic leadership in the relationship between perceived organizational politics and employee outcomes. Specifically, we aim to answer the following questions: How does authentic leadership moderate the relationship between perceived organizational politics and employee task-oriented performance? Does authentic leadership mitigate the negative impact of perceived organizational politics on OCB, including OCBI (individual-focused) and OCBO (organization-focused) behaviors?

Our study is poised to make several significant contributions to leadership research. First, by investigating the moderating role of authentic leadership in a high-politics environment, we enrich the theoretical understanding of leadership effectiveness in complex organizational contexts. Second, by focusing on the museum sector, we contribute to the literature on leadership in cultural institutions, offering practical implications for museum management and policy. Lastly, our research underscores the importance of contextual factors in leadership studies, advocating for a more nuanced and context-sensitive approach to leadership theory and practice. Through this investigation, we anticipate advancing the field’s understanding of how authentic leadership can protect against the deleterious effects of organizational politics, fostering a more engaged, productive, and harmonious work environment.

Hypotheses development

Perception of organizational politics (POP) and task-oriented performance (TP)

POP is a widely considered element in organizational behavior regarding employee performance. POP is viewed as a “subjective appraisal of the extent to which self-serving behavior, favoritism, and manipulation are inherent in decision-making processes” (Ferris et al. 2002). Consequently, employees who view their organization as politicized think outcomes and promotions are resultantly based on favoritism rather than performance, resulting in a win-lose situation. Therefore, employees lose interest and disengage from work, and their intrinsic motivation to perform a job decreases. As a result, employees’ workplace engagement and performance outcomes are reduced (Meisler and Vigoda-Gadot, 2014). Employees who perceive their workplace as politically influenced are likely to feel less committed and satisfied with their jobs. They believe career progression depends more on political factors than individual performance and merit (Hochwarter et al. 2020).

Moreover, Bedi and Schat (2013) revealed a direct effect of POP on emotional exhaustion, directly affecting how employees regulated their work—by satiating their physiological energy, cognitive resources, alertness, emotional stability, and enthusiasm. This research further proves that POP causes employees’ work-related stress and burnout, leading to lower productivity and work quality. Their findings also indicated that POP-induced job stress disrupts the cognitive processes of work—making employees less concerned about their objectives. Likewise, Li et al. (2020) showed that job stress associated with POP led to cognitive distraction and attentional shifting, which translated to diminished task-oriented performance.

Owing to museums’ unique organizational structure and mission-driven nature (Palumbo et al. 2022), we hypothesized that this negative impact might be more substantial than that of other organizations. Specifically, an adversarial organizational and political climate in museums could hinder workers’ ability to collaborate effectively as a team—more than in other workplaces—and, therefore, have a more substantial negative impact on employees’ task-oriented performance. Aligned with this concept, the COR theory, which posits that individuals’ primary goal is “to acquire, retain and protect valued resources” (Hobfoll, 1989), supports this premise, as POP threatens individuals’ resources. COR theory suggests that organizational politics create stress and task-oriented performance declines. The above literature illustrates that a higher level of POP is associated with less motivation, higher levels of burnout, increased job stress, and lower job satisfaction. These factors directly affect how employees perform at work. To minimize POP and promote a fair and transparent working environment; implementing effective strategies to reduce POP, especially within settings like museums that rely on collaboration between colleagues, should be considered.

H1: Perception of organizational politics (POP) negatively related to employees’ task-oriented performance (TP) in the museum industry.

Perception of organizational politics (POP) and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB)

The relationship between POP and OCB is emerging as a prominent scholarly topic regarding specific organizational dynamics (Goo et al. 2022; Kaur and Kang, 2023; Tripathi et al. 2023). In the context of museums, which embrace preserving and fostering cultural heritage while adhering to administrative necessities (Nikolic Deric et al. 2020), it is crucial to uncover this connection to enhance the work environment and advance institutional goals.

SET (Blau, 1964) provides a theoretical backdrop for understanding how POP can predict OCB. Social exchange theory explains how individuals engage in exchanges to fulfill their needs—including exchange within organizations where employees reciprocate by expending effort (i.e., individuals perform OCB) or reciprocated by the organization in the form of rewards obtained (i.e., perform in-role behaviors). For example, in a museum, employees might think of OCB as reciprocal behaviors to create and maintain a positive organizational climate and build opportunities and recognition (Asif et al. 2023). However, the presence of POP may disrupt this exchange and influence OCB and job performance. For example, Syed et al. (2023) found that employees who perceived their organization had a high level of politics were less likely to engage in discretionary efforts to help their coworkers.

More specifically, in a museum environment, POP may be more prevalent and more focused on fostering creativity. For example, employees more politically adept in the organizational environment are strategically engaged in OCB. Kaur and Kang (2023) suggest that employees who are particularly good at politics might also participate in OCBO to increase their visibility and influence. Such employees might see an opportunity and influence the organization. However, the broader pattern suggests that higher perceptions of politics will reduce employees’ prosocial motivation and thus reduce OCBI and OCBO. This association is further reinforced by Tripathi et al. (2023) self-regulation view, which predicts that perceptions of injustice and inequity in politically charged environments are associated with OCB. Employees who perceive organizational politics as unfair and inequitable are likelier to disengage from extra-role behavior, which disrupts the social exchange process, a key element to SET. Hence, the significant association between POP and OCB indicates that the ‘dark side’ of politics should not be ignored when exploring issues about why employees act as they do or whether they exhibit the attitudes deemed important for the successful functioning of the organization (especially in the museum context).

H2: Perception of organizational politics (POP) negatively related to OCBI in the museum industry.

H3: H1: Perception of organizational politics (POP) negatively related to OCBO in the museum industry.

Moderating role of authentic leadership (AL)

As cultural institutions, museums are not immune to organizational politics, which can manifest in various forms, including curatorial decisions, funding patterns, and exhibition schedules, often driven by subtle interpersonal processes (Gray, 2015). Such processes can be viewed as political and authentic leadership, prioritizing values alignment and transparency, and are especially important for working in these environments (Gardner et al. 2011). By maintaining a culture of trust and equity, authentic leaders can minimize the detrimental effects of Perceived Organizational Politics (POP) in preserving and sharing cultural heritage. This, in turn, will help the employees focus on achieving the museum’s mission—including providing exhibitions, educational programs, and services to the public—and implementing organizational strategies.

Social Exchange Theory (SET) posits that relationships are based on a series of exchanges between individuals, where each party expects to receive benefits in return for what they give (Blau, 1964). In museum settings, authentic leaders create a climate of trust by communicating a transparent decision-making framework, reducing feelings of uncertainty, and countering the perceptions of hidden agendas that POP creates (Gardner et al. 2021). This trust-building mechanism aligns with the principles of SET, fostering a reciprocal relationship between leaders and employees. Employees, in turn, are more likely to focus on the museum’s mission, such as providing exhibitions, educational programs, and services to the public and implementing organizational strategies.

Conservation of Resource Theory (COR) suggests that individuals strive to acquire, retain, and protect resources, and resource loss can lead to adverse outcomes (Hobfoll, 1989). Authentic leadership fosters a culture of meritocracy by advocating core values, reducing the perception of favoritism (Akuffo and Kivipõld, 2019). Moreover, such leaders contribute to the psychological well-being of employees by fostering open communication and providing growth opportunities, making employees more resistant to the adverse effects of POP (Awad et al. 2024). By conserving and enhancing resources, authentic leaders can create a positive work environment that encourages employees to focus on their tasks and engage in Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB).

The buffering role of authentic leadership in the relationship between POP and employee Task Performance (TP) in museums is crucial. Employees perceiving politics may become demotivated, affecting their task performance. However, under authentic leadership, employees are encouraged to work towards the organization’s goals despite the perception of politics (Ackerson and Baldwin, 2019). Empirical research in museum settings can provide valuable insights into the practical implications of this proposition, potentially leading to strategies that enhance workplace dynamics and employee effectiveness in cultural institutions.

This research extends the previous studies by suggesting that authentic leaders can buffer the adverse impact of POP on TP and OCB (OCBI and OCBO) by several mechanisms. Firstly, authentic leadership creates a climate of trust by communicating a transparent decision-making framework (Gardner et al. 2021). This openness helps to counter the perceptions of hidden agendas by reducing feelings of uncertainty that POP creates. Secondly, authentic leadership fosters a culture of meritocracy within the organization by advocating core values, thus reducing the perception of favoritism (Akuffo and Kivipõld, 2019). Moreover, such leaders contribute to the psychological well-being of employees by fostering open communication and providing growth opportunities, which makes employees more resistant to the adverse effects of the POP (Awad et al. 2024).

Previous studies have suggested several moderators in the POP–performance relationship. For instance, Park and Lee (2020) identified public service motivation to attenuate this negative association, suggesting that highly motivated employees might overlook such political behaviors because of their dedication to the organization. Additionally, age can buffer the influence of POP. When people exert control over their work, they are less likely to feel influenced by organizational politics, leading to higher task-oriented performance (Chang et al. 2009). Variation in cultural context is another potentially relevant factor (Miller et al. 2008) that influences POP. Perhaps POP exerts a more decisive influence on employee behavior in different cultural settings. For example, in collectivistic cultures, employees might be more tolerant of organizational politics because of group harmony and interpersonal relationships. In contrast, in individualistic cultures such as the US, political behaviors are often perceived as more detrimental to task-oriented performance (Or and Berkovich, 2023).

Hence, authentic leadership might be a significant moderating variable in museums’ relationship between POP and employee task-oriented performance (TP). Instead of being demotivated by the perception of politics, we believe that authentic leaders can instill more transparency, trust, and a value-driven culture in the organization and that employees will work at their best toward their ultimate goals. Therefore, further empirical research within museum settings can provide valuable insights into the practical implications of this proposition, potentially leading to strategies that enhance workplace dynamics and employee effectiveness in cultural institutions.

Similarly, authentic leadership moderates the relationship between POP and OCB in museum settings. Specifically, when authentic leadership is high, the negative effect of POP on OCBI and OCBO is expected to be mitigated, leading to a stronger positive association between employees’ OCBI and OCBO, even in the presence of political maneuvering (Rasheed et al. 2023). While specific studies might be limited to museum settings, the generalizability of the previous findings across different sectors, such as service and non-profit organizations, supports their applicability to the museum industry.

Empirical evidence offers significant moderating effects of leadership in different ways. For instance, Vigoda-Gadot and Beeri (2011) stated that transformational leadership minimized the negative consequences of POP on job satisfaction. In addition, Tziner et al. (2021) suggested that transformational leaders may enable an increased level of OCB by allowing collectivistic goals; it further encapsulates a proposed process of similar moderating influence of authentic leadership. On the other hand, earlier research findings suggested different moderating variables of the POP–OCB relationship. For example, psychological capital—a state of hope, optimism, resilience, and efficacy could be considered a personal resource that might buffer the adverse effects of POP and, in turn, enable employees to perform OCB (Avey et al. 2011; Borman et al. 2001; Vilarino del Castillo and Lopez‐Zafra, 2022). Similarly, organizational justice (Harris et al. 2007; Young, 2020)—especially distributive and procedural justice—could mitigate the detrimental effects of POP on OCB, enabling employees to be more willing to engage in OCB regardless of the political environment.

Moreover, affective commitment is also a key factor in organizations. Meyer and Herscovitch (2001) define affective commitment as an emotional attachment to the organization that stems from a caring relationship; authentic leadership could be particularly helpful in fostering it. Employees committed to their organization will be less discouraged by POP and more likely to exhibit OCB (Tziner et al. 2021). In museums, where a sense of mission is essential, authentic leadership might enhance this connection and make employees more resilient against the consequences of the perception of politics.

Furthermore, Grandey (2000) highlighted the importance of managing emotions in service-oriented industries like museums. Authentic leaders who recognize and support the emotional demands of their staff can reduce emotional exhaustion and increase prosocial behaviors (Kunze et al. 2013). This evidence suggests that authentic leadership can indirectly influence OCB by reducing the emotional toll of POP.

The above literature collectively indicates that the moderating role of authentic leadership in the relationships among POP, OCB, and TP is complex. In for-profit organizations (Sarros et al. 2011), where profit maximization is a key focus, the primary goal of museums is to preserve art artifacts and foster learning experiences, which require a high level of cooperation and discretionary efforts (Murray, 2018). Hence, the buffering role of authentic leadership is crucial. Investigating these propositions from a museum context will likely extend our knowledge of how leadership practices can help shape a positive work environment, leading to greater organizational effectiveness and impact on museums.

H4: Authentic leadership (AL) significantly moderates the negative impact of the perceptions of organizational politics (POP) on employees’ task-oriented performance (TP) in the museum industry.

H5: Authentic leadership (AL) significantly moderates the negative impact of organizational politics (POP) perceptions on OCBI in the museum industry.

H6: Authentic leadership (AL) significantly moderates the negative impact of organizational politics (POP) perceptions on OCBO in the museum industry.

Methodology

Participants

The study focused on employees in six museums across Pakistan, covering diverse roles, including curators, archivists, and administrative and supportive staff. Participants were selected from a stratified random sample within these museums to ensure a representative cross-section of the industry (DeVaro et al. 2007). To be included, participants needed to have a minimum of 6 months of employment in their current position to ensure sufficient familiarity with their work environment and organizational culture (Bagozzi and Yi, 2012).

A total of 586 employees were approached, and 478 (81.57% response rate) agreed to participate. The final sample consisted of 436 participants (91.21% response rate of agreed participants) after accounting for incomplete responses across the four waves of data collection. The multi-wave design enables us to analyze associations more comprehensively and helps to minimize CMB (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Harman’s single-factor test was also applied to check the potential of common method bias due to the same participants during data collection. The highest variance explained for the constructs was 32.73%, which indicated no common method bias in the results. We also applied the common latent factor technique to check the common variance among all constructs, as suggested by Podsakoff et al. (2003). Table 1 displays the demographic details of 436 participants involved in this study. Considering gender distribution, most participants are male, constituting 77.98% of the sample, whereas females comprise 22.02%, indicating a notable male dominance. Regarding age distribution, participants span various age groups, with the most significant proportion falling within the 31–40 years range, accounting for 40.37% of the sample, followed by the 20–30 age range at 21.33%. Representation declines with age, with only 13.99% falling within the 51–60 years range and a mere 3.90% over 60 years old, signaling a focus on younger to middle-aged professionals in the study. Education level reveals that a significant portion of participants possess a Bachelor’s degree (62.16%), followed by those with a Master’s degree (27.98%), while a smaller fraction holds intermediate education (9.86%). Job experience varies across participants, with the highest concentration in the 6–10 years category (38.30%), followed by 1–5 years (21.56%), and 11–15 years (19.72%). This suggests a considerable presence of mid-career professionals, with fewer individuals having less than a year (7.11%) or more than 20 years (2.98%) of experience. Regarding job positions, the distribution shows a mix, with non-managerial staff comprising the most prominent segment (40.83%), followed by junior managers (29.13%) and senior managers (21.56%). Directors constitute the smallest group (8.49%), indicating a focus on middle management and below within the study’s context.

Procedure

Since our study involved multiple data collection waves, first, participants completed a baseline survey to measure their perceptions of authentic leadership and provide demographic details. Two weeks later, they completed the survey to measure OCB and task-oriented performance, and in the third wave, information about participants’ perceptions of organizational politics (POP) was collected. Finally, in the fourth wave, participants completed the follow-up measures of all the variables they had completed in previous waves.

Data collection took place online using a secure survey platform to ensure the confidentiality of responses. Participants signed informed consent statements before each survey and provided detailed information about the study. To achieve a maximum response rate and reduce attrition, weekly email reminders were sent to participants before the survey window closure (Dillman et al. 2014).

Instruments

Authentic leadership (AL)

AL was assessed with a 16-item ALQ scale developed by Walumbwa et al. (2008). The questionnaire evaluates the perceived authenticity of a leader based on “self-awareness, relational transparency, balanced processing, and internalized moral perspective.” The items in the ALQ evaluate whether (1) “a leader accurately describes how he or she is viewed by others”, (2) “how often a leader openly shares information”, (3) “to what extent a leader seeks feedback in order to enhance interactions”, and (4) “how consistent a leader’s actions are with what is stated by the leader”. A five-point Likert scale (“1: never to 5: often”) was used to rate this scale. The Cronbach’s α for AL is 0.93, which shows excellent internal consistency.

Perception of organizational politics (POP)

POP was evaluated with a 15-item scale adapted from Kacmar and Ferris (1991). This scale assesses employees’ experience of political behaviors within their organization, such as self-serving actions and unfair practices. Responses were gathered on a five-point Likert scale (“1: strongly disagree to 5: strongly agree”). An illustrative item from the scale is: “There are cliques or groups that exist in the organization that hinder productivity.” The POP scale presented notable internal consistency, with an α coefficient of 0.87.

Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB)

OCB was assessed using a 16-item scale established by Lee and Allen (2002). This scale measures voluntary, extra-role behaviors by employees that enhance organizational effectiveness and foster a positive work environment. It consists of two subscales: OCB-Individual (OCBI) and OCB-Organizational (OCBO). A five-point Likert scale (“1: never to 5: often”) was used to rate this scale. Examples include “willingly give your time to help others who have work-related problems” for OCBI and “keep up with developments in the organization “ for OCBO. The α coefficients were 0.90 for OCBI and 0.85 for OCBO, indicating high reliability.

Task-oriented performance (TP)

TP was evaluated using a seven-item scale proposed by Williams and Anderson (1991). TP scale evaluates how well employees fulfill their job responsibilities and meet the formal requirements of their roles. A five-point Likert scale (“1: never to 5: often”) was used to rate each item. An example item is: “Performs tasks that are expected of him/her.” The scale showed high internal consistency, with an α coefficient of 0.91.

Control variables

Following prior research on Authentic Leadership (Erkutlu and Chafra, 2013; Xiong et al. 2016), key demographic variables were used as control variables to account for potential confounding effects. These included age, gender, education, and tenure. Age and tenure were analyzed in years. Gender was figured as “1 for male and 2 for female”, while educational qualification was coded as “1 for Master’s and 2 for Undergraduate”.

Results and analysis

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients of all studied variables. Our analysis primarily revolves around five key variables: AL, OCBI, OCBO, TP, and POP. Table 2 reveals that the mean (X̅) score for AL is 3.41, accompanied by a standard deviation (σ) of 0.92, indicating a moderate to high level of AL on average. Similarly, OCBI exhibits an X̅ score of 3.09 and a standard deviation of 1.23, suggesting a moderate average level with a broader variability compared to AL. Notably, OCBI positively correlates with AL (correlation coefficient = 0.49), indicating a strong positive relationship wherein an increase in AL tends to correspond with an increase in OCBI. Moving to OCBO, the mean score is slightly lower at 2.97, with a higher standard deviation of 1.46, indicating a wider range of values. OCBO demonstrates moderate positive correlations with AL (0.28) and OCBI (0.31), indicating that higher scores on AL and OCBI are generally associated with higher scores on OCBO, albeit to a lesser extent than the relationship observed between AL and OCBI. TP, with a mean of 3.27 and a standard deviation of 1.33, displays a similar average to AL and OCBI but with considerable variation in scores. TP exhibits strong positive correlations with all three preceding variables (AL = 0.47, OCBI = 0.49, OCBO = 0.53), indicating meaningful increases as one variable increases.

Contrastingly, POP has the lowest mean score at 2.86, accompanied by a standard deviation of 1.25, indicating a moderate relationship. Remarkably, POP negatively correlates with all previous variables: AL (−0.59), OCBI (−0.39), OCBO (−0.52), and TP (−0.43). These strong negative correlations suggest that an increase in POP corresponds to a decrease in AL, OCBI, OCBO, and TP scores, and vice versa. Furthermore, the values in parentheses denote the discriminant validity of all five variables, ranging from 0.74 to 0.83, surpassing the inter-correlations among these variables (Hair et al. 2022).

Measurement model

The measurement model presented in Table 3 evaluates four key constructs—Authentic Leadership (AL), Task-oriented Performance (TP), Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCBI and OCBO), and Perception of Organizational Politics (POP)—with their respective items, reliability coefficients, factor loadings (λ), standard errors, and t-values. Authentic leadership, comprising 16 items, demonstrates higher internal consistency (α = 0.93, Composite Reliability (CR) = 0.91). Each item exhibits strong factor loadings ranging from 0.721 to 0.829, indicating that these items effectively capture the construct. Task-oriented performance, with seven items, has α = 0.91 and CR = 0.88, highlighting its reliability, with factor loadings between 0.730 and 0.805. Organizational citizenship behavior is split into OCBO (behavior towards organization) and OCBI (behavior towards individuals), with α = 0.90 and CR = 0.88, showing similar reliability. OCBI and OCBO have loadings from 0.723 to 0.807, confirming their validity. With 15 items, POP has slightly lower but acceptable reliability (α = 0.87, CR = 0.83), with factor loadings ranging from 0.723 to 0.790. Results of the measurement model present a reliable and valid framework for assessing the constructs, with each dimension demonstrating consistency and discriminant validity based on established criteria (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Hair et al. 2022; Nunnally, 1994). This model effectively measures the constructs with strong psychometric properties, providing a robust foundation for further analysis.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

Table 4 offers the results of CFA, demonstrating the factorial validity of authentic leadership (AL), task-oriented performance (TP), organizational citizenship behavior (OCBI and OCBO), and perception of organizational politics (POP).

The hypothesized model yields a χ² value of 360.642 with 253 degrees of freedom, resulting in a χ²/df ratio of 1.425, which aligns with conventional standards of good model fit (Bentler and Chou, 1987). The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) at 0.954 and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) at 0.948 surpass the widely accepted benchmarks of 0.90, signifying an excellent fit (Kline, 2012). Additionally, the RMSEA (0.046) and SRMR (0.034) fall well below the 0.08 criterion, further supporting the model’s acceptability (Steiger, 1990).

Contrasting this, the 4-factor model experiences a substantial deterioration in fit, as evidenced by a significant increase in χ² to 701.526, accompanied by a Δχ² of 340.884 against the hypothesized model. This indicates that combining AL and TP into a single factor and maintaining the others separately does not align well with the data, leading to a CFI of 0.871 and TLI of 0.854, below the ideal thresholds. The RMSEA’s rise to 0.078 signals a less precise approximation of the actual population model.

The fit indices systematically decline as the models simplify further to three and two factors and eventually to a single factor. For instance, the three-factor models with different combinations (AL + TP, OCBI + OCBO, POP and AL, TP, OCBI + OCBO + POP) display χ²/df ratios > 3, CFI and TLI values below 0.85, and RMSEA values approaching or exceeding 0.08, which denote increasingly inadequate model fits (MacCallum et al. 1996). The 2-factor and 1-factor models exhibit the poorest fits, with RMSEA values of 0.091 and 0.105, respectively, highlighting the loss of important discriminant validity when all constructs are collapsed into fewer or a single factor.

These results underscore the importance of maintaining the five constructs as distinct in organizational research, as the hypothesized 5-factor model offers the most coherent and theoretically grounded representation of the data. The results align with the principle of factorial specificity in structural equation modeling, emphasizing that treating each construct individually is crucial for accurately capturing their unique contributions to workplace dynamics (Diamantopoulos et al. 2012).

Hypotheses testing

Table 5 revealed the statistical analysis of six hypotheses (H1–H6) concerning direct and moderating relationships involving the POP, AL, OCB (OCBI and OCBO), and TP.

Hypothesis H1 indicates a negative relationship between POP and OCBI, with a coefficient of −0.281, suggesting that as POP increases, OCBI decreases. The standard error (0.113) quantifies the variability of the coefficient estimate, while the t-value (−2.487) and p-value (<0.01) denote statistical significance at the 1% level, indicating that this relationship is unlikely due to chance. The 95% confidence interval [−0.381, −0.455] confirms the likely range of the proper effect size with 95% certainty. Hypothesis H2 also proposes a negative association between POP and OCBO, with a more substantial coefficient (−0.326) than H1. The t-value (−2.763) and p-value (<0.01) reiterate statistical significance at the 1% level. The 95% confidence interval [−0.219, −0.654] provides the probable range of the actual effect size. Hypothesis H3 examines the relationship between POP and TP, presenting a strong negative relationship with a coefficient of −0.357. The t-value (−3.132) and p-value (<0.01) highlight high statistical significance with a 95% confidence interval [−1.212, −3.018].

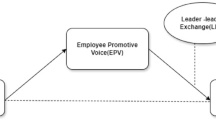

Hypotheses H4, H5, and H6 investigate AL’s role as a moderator in the relationships established in H1, H2, and H3. For example, in H4, AL positively impacts OCBI (coefficient = 0.173), whereas POP negatively influences OCBI (coefficient = −0.188). The interaction term (AL × POP) has a positive coefficient (0.129), suggesting that the negative effect of POP on OCBI diminishes when AL is high. The t-values, p-values, and confidence intervals prove these effects’ statistical significance and magnitude. H5 explores how AL can alter the relationship between POP and OCBO. AL has a small positive effect on OCBO (coefficient = 0.089), although this effect is not statistically significant (p-value = 0.17). This suggests that AL alone does not significantly influence OCBO. However, POP has a negative relationship with OCBO (coefficient = −0.175), which is statistically significant (p-value < 0.01), indicating that a higher level of POP is associated with lower levels of OCBO. The interaction term (AL × POP) shows a positive coefficient (0.114) and is marginally significant (p-value < 0.05). This implies that the negative effect of POP on OCBO is less pronounced when AL is higher. In other words, when authentic leadership is present, the detrimental impact of POP on OCBO is mitigated. The 95% confidence interval [0.098, 0.312] indicates that the actual effect size of this interaction falls within this range with 95% confidence. H6 examines whether AL can moderate the relationship between POP and TP. Although AL positively affects TP (coefficient = 0.167), it is not statistically significant (p-value = 0.21), suggesting AL does not significantly enhance TP. POP, however, has a negative relationship with TP (coefficient = −0.192), which is statistically significant (p-value < 0.01), implying that a higher level of POP is associated with poorer task-oriented performance. The interaction term (AL × POP) also has a positive coefficient (0.138) and is statistically significant (p-value < 0.01). This suggests that when AL is high, the negative impact of POP on TP is reduced. In essence, authentic leadership acts as a buffer against the adverse effects of POP on task-oriented performance. The 95% confidence interval [0.151, 0.785] gives us the range within which the true effect size of this interaction is likely to fall with 95% confidence. SEM results for the moderation effects are also presented in Fig. 2.

Discussion

Theoretically, the negative relationship between the perception of organizational politics (POP) and organizational citizenship behaviors (OCB) has been extensively studied (Ferris et al. 2002; Vigoda-Gadot and Drory, 2006). OCBs, including organizational citizenship behavior toward the organization (OCBO) and individuals (OCBI), are generally regarded as voluntary and prosocial behaviors that benefit the organization (Organ, 1988). Conversely, POP often fosters self-serving behavior, reducing trust and harming overall organizational citizenship behaviors (Hochwarter et al. 2020).

The relationship between POP and OCBO/OCBI in the museum industry was more complex than anticipated. Rather than uniformly negative, the findings suggest that the museum context—where organizational goals often center around cultural preservation—might buffer the adverse effects of POP. This contrasts with corporate settings, where the focus is often on profit and individual gain. Museum employees may engage in OCBO/OCBI despite perceived politics due to their intrinsic connection to the organization’s mission.

These findings contribute to organizational behavior theory by suggesting that the organization’s context plays a significant role in how POP impacts citizenship behaviors. Unlike corporate environments where self-interest dominates, mission-driven organizations like museums may see employees maintain or increase their OCBO and OCBI despite internal politics. This contributes to a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between POP and OCB, advocating for future research that examines sector-specific factors (Chang et al. 2009; Vigoda-Gadot and Beeri, 2011).

POP has a negative impact on task performance, as political environments tend to drain employees’ emotional and cognitive resources (Hochwarter et al. 2020). Organizational politics increases stress and undermines focus, decreasing job performance, particularly in competitive environments (Cropanzano et al. 1997).

In contrast to existing theories, the museum industry did not show a strong negative impact of POP on task performance. This could be explained by employees’ intrinsic motivations, where dedication to the cultural and educational mission overrides the harmful effects of internal politics. In mission-driven organizations like museums, employees may continue to prioritize task performance because they identify with the institution’s purpose, mitigating the adverse effects of POP (Wright and Pandey, 2008). This finding adds to organizational behavior theory by suggesting that the impact of POP on task performance is highly dependent on the sector. Theories of organizational politics often assume that stress from politics directly translates to poorer task outcomes. However, in public or mission-driven environments, the commitment to the organization’s larger goals might play a protective role. This insight opens avenues for further research on the moderating role of intrinsic motivation and organizational mission alignment in politically charged environments (Vigoda-Gadot, 2007).

Authentic leadership (AL) is characterized by relational transparency, self-awareness, and balanced processing, which foster trust and ethical behavior within organizations (Walumbwa et al. 2008). Previous research indicates that authentic leaders encourage open communication and mutual support among members, which reduces the adverse effect of POP by promoting a work environment that discourages self-serving behaviors and encourages openness (Gardner et al. 2011, 2021; Walumbwa et al. 2008).

Our study shows that authentic leadership moderates the relationship between POP and organizational outcomes (e.g., OCBI, OCBO, and task performance). Under high authentic leadership, the detrimental effects of POP were significantly reduced, and in some instances, positive organizational outcomes were even enhanced. This suggests that authentic leadership can transform politically charged environments into more supportive spaces, fostering higher levels of OCB and maintaining task performance. These results contribute to the growing literature on leadership and organizational politics by demonstrating that AL is more than just a mitigating factor—it can actively transform how employees react to organizational politics. While past studies focus on AL’s role in reducing negative outcomes, our findings suggest that AL can reshape organizational dynamics and enhance prosocial behaviors, even in high-politics contexts. This underscores the need for further research into the comparative effects of different leadership styles in moderating the politics-performance link (Walumbwa et al. 2008).

Our study helps to clarify some unresolved issues in the relationship between POP and organizational outcomes. Specifically, we highlight that the negative effects of POP are not uniform across different organizational settings. In contexts like the museum industry, where intrinsic motivations and organizational mission play key roles, the impact of POP on behaviors like OCB and task performance is more nuanced. These findings contribute to a more comprehensive organizational behavior theory by recognizing industry-specific boundary conditions. Additionally, these findings suggest the need for future research to focus on industry-specific factors and leadership styles as moderators of the effects of POP. The nuanced role of authentic leadership in moderating POP’s effects also opens new avenues for research into other leadership styles, such as transformational and servant leadership. Overall, the study contributes to the maturation of organizational behavior theories by recognizing the complexity of POP’s effects across different contexts and sectors. Our study contributes to the theoretical advancement of organizational behavior and leadership theories by demonstrating how context (e.g., the museum industry), intrinsic motivation, and leadership styles, such as authentic leadership, serve as key moderators in the relationship between POP and organizational outcomes. These findings challenge the traditional view of POP as universally detrimental and encourage the development of more context-sensitive theories.

Practically, the complex interplay between POP, OCB (OCBI and OCBO), TP, and AL underscores how important leadership style is in mitigating the negative effects of POP by promoting proper leadership development programs for organizational effectiveness (Hochwarter et al. 2020). These findings would be vital to museum management and HR professionals. The impact of POP on employee task-oriented performance and behavior cannot be overstated. This is especially evident in fair and transparent policies and practices, which reduce the adverse effects of POP. Enhanced leadership development with genuineness is an additional approach to reducing the adverse impacts of POP. Developing authentic museum leaders would lead to higher employee engagement and establishing a positive work culture, ultimately improving organizational performance.

This study suggests that the museum work environment, emphasizing education, cultural preservation, and public engagement, offers a place where the effects of POP and contributions of authentic leadership are intensely magnified. Museum professionals, divided between the curatorial responsibilities to the public and institution and a public service imperative, are likely to be quite sensitive to organizational politics. They will significantly benefit from the supportive and transparent leadership style (Elliott, 2020; Schwarz et al. 2020).

In addition to mitigating adverse outcomes, authentic leadership can proactively advance organizational behavior and performance, shifting the culture from problem management to the flourishing capabilities of a museum’s employees. They encourage creativity, teamwork, and a shared vision to their followers, which is critical for meeting public needs and adapting to the constantly changing demands of the cultural sector (Zhang et al. 2022).

Limitations of the study and future directions

Firstly, this research focuses on the impact of a single moderator (AL) and aims to introduce mediating variables such as trust in management, organizational identity, and autonomy. These variables could help us understand how perceptions of organizational politics influence OCB and task-oriented performance. Secondly, this research is carried out in the museum industry, which is unique. Comparative research across various sectors could help determine if the observed impacts are consistent or vary by industry, providing a broader perspective. Thirdly, intervention studies aimed at reducing perceptions of organizational politics or enhancing authentic leadership practices would provide practical insights into strategies for improving employee behaviors. Fourthly, our research is based on a single nation. Cross-national studies could investigate how national cultural dimensions and institutional environments shape the relationships between perceptions of organizational politics, authentic leadership, and employee outcomes, broadening the scope of the research. Moreover, incorporating technological factors into future studies could reveal how digital tools and platforms influence POP and leadership and their subsequent effects on employee behaviors. Finally, qualitative methods, including case studies, interviews, and ethnographic research, could provide a deeper understanding of the nuanced experiences of employees facing organizational politics and leadership dynamics, enriching our comprehension of these phenomena.

Data availability

The data utilized in this study was gathered from different public sector organizations and is subject to confidentiality agreements with the participants and particular organizations. Due to these confidentiality agreements, the data cannot be shared publicly. However, access to the data may be granted upon reasonable request and with permission from the relevant organization.

References

Ackerson AW, Baldwin JH (2019) Leadership matters: leading museums in an age of discord. Rowman & Littlefield

Akuffo IN, Kivipõld K (2019) Influence of leaders’ authentic competences on nepotism-fasvouritism and cronyism. Manag Res Rev 43(4):369–386

Akuffo IN, Kivipõld K (2021) Authentic leadership competences and positional favouritism: impact on positive and negative organisational effectiveness. Int J Appl Decis Sci 14(1):81–104

Asif M, Li M, Hussain A, Jameel A, Hu W (2023) Impact of perceived supervisor support and leader–member exchange on employees’ intention to leave in public sector museums: a parallel mediation approach [original research]. Front Psychol 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1131896

Avey JB, Reichard RJ, Luthans F, Mhatre KH (2011) Meta-analysis of the impact of positive psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Hum Resour Dev Q 22(2):127–152

Awad AHI, Hassan AHA, Abdel Majeed AA, El-Halim A, Ghanem AAE-K (2024) Effect of organizational politics on job insecurity in hotels and travel agencies: the moderating role of authentic leadership. Minia J Tour Hosp Res 17(2):24–43

Bagozzi RP, Yi Y (2012) Specification, evaluation, and interpretation of structural equation models. J Acad Mark Sci 40(1):8–34

Bedi A, Schat AC (2013) Perceptions of organizational politics: a meta-analysis of its attitudinal, health, and behavioural consequences. Can Psychol/Psychol Can 54(4):246

Bentler PM, Chou C-P (1987) Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociol Methods Res 16(1):78–117

Blau PM (1964) Exchange and power in social life. John Wiley

Borman WC, Penner LA, Allen TD, Motowidlo SJ (2001) Personality predictors of citizenship performance. Int J Sel Assess 9(1–2):52–69

Chang C-H, Rosen CC, Levy PE (2009) The relationship between perceptions of organizational politics and employee attitudes, strain, and behavior: a meta-analytic examination. Acad Manag J 52(4):779–801

Cropanzano R, Howes JC, Grandey AA, Toth P (1997) The relationship of organizational politics and support to work behaviors, attitudes, and stress. J Organ Behav: Int J Ind Occup Organ Psychol Behav 18(2):159–180

Cropanzano R, Mitchell MS (2005) Social exchange theory: an interdisciplinary review. J Manag 31(6):874–900

DeVaro J, Li R, Brookshire D (2007) Analysing the job characteristics model: new support from a cross-section of establishments. Int J Hum Resour Manag 18(6):986–1003

Diamantopoulos A, Sarstedt M, Fuchs C, Wilczynski P, Kaiser S (2012) Guidelines for choosing between multi-item and single-item scales for construct measurement: a predictive validity perspective. J Acad Mark Sci 40:434–449

Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM (2014) Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method. John Wiley & Sons

Elliott J (2020) Tourism: politics and public sector management. Routledge

Erkutlu H, Chafra J (2013) Effects of trust and psychological contract violation on authentic leadership and organizational deviance. Manag Res Rev 36(9):828–848

Ferris GR, Adams G, Kolodinsky RW, Hochwarter WA, Ammeter AP (2002) Perceptions of organizational politics: Theory and research directions. In Yammarino FJ, Dansereau F (Eds.), The many faces of multi-level issues (pp. 179–254). Elsevier Science/JAI Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1475-9144(02)01034-2

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50

Gardner WL, Cogliser CC, Davis KM, Dickens MP (2011) Authentic leadership: a review of the literature and research agenda. Leadersh Q 22(6):1120–1145

Gardner WL, Karam EP, Alvesson M, Einola K (2021) Authentic leadership theory: the case for and against. Leadersh Q 32(6):101495

Goo W, Choi Y, Choi W (2022) Coworkers’ organizational citizenship behaviors and employees’ work attitudes: the moderating roles of perceptions of organizational politics and task interdependence. J Manag Organ 28(5):1011–1035

Grandey AA (2000) Emotional regulation in the workplace: a new way to conceptualize emotional labor. J Occup Health Psychol 5(1):95

Gray C (2015) The politics of museums. Palgrave Macmillan

Hair JF, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Black WC (2022) Multivariate data analysis. I Cengage learning

Harris KJ, Andrews MC, Kacmar KM (2007) The moderating effects of justice on the relationship between organizational politics and workplace attitudes. J Bus Psychol 22:135–144

Hobfoll SE (1989) Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol 44(3):513

Hochwarter WA, Rosen CC, Jordan SL, Ferris GR, Ejaz A, Maher LP (2020) Perceptions of organizational politics research: past, present, and future. J Manag 46(6):879–907

Kacmar KM, Ferris GR (1991) Perceptions of organizational politics scale (POPS): development and construct validation. Educ Psychol Meas 51(1):193–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164491511019

Kaur N, Kang LS (2023) Perception of organizational politics, knowledge hiding and organizational citizenship behavior: the moderating effect of political skill. Pers Rev 52(3):649–670

Kelly L (2023) Authentic leadership: roots of the construct. In: Mindfulness for authentic leadership: theory and cases. Springer, pp. 17–52

Kline RB (2012) Assumptions in structural equation modeling. Handb Struct Equ Model 111:125

Kunze F, Boehm S, Bruch H (2013) Age, resistance to change, and job performance. J Manag Psychol 28(7–8):741–760

Lee K, Allen NJ (2002) Organizational citizenship behavior and workplace deviance: the role of affect and cognitions. J Appl Psychol 87(1):131–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.1.131

Li C, Liang J, Farh J-L (2020) Speaking up when water is murky: an uncertainty-based model linking perceived organizational politics to employee voice. J Manag 46(3):443–469

Luu TT (2020) Linking authentic leadership to salespeople’s service performance: the roles of job crafting and human resource flexibility. Ind Mark Manag 84:89–104

MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM (1996) Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol Methods 1(2):130

Meisler G, Vigoda-Gadot E (2014) Perceived organizational politics, emotional intelligence and work outcomes: empirical exploration of direct and indirect effects. Pers Rev 43(1):116–135

Meyer JP, Herscovitch L (2001) Commitment in the workplace: toward a general model. Hum Resour Manag Rev 11(3):299–326

Miller BK, Rutherford MA, Kolodinsky RW (2008) Perceptions of organizational politics: a meta-analysis of outcomes. J Bus Psychol 22:209–222

Murray C (2018) Arts education: a philanthropic priority? Honors Theses. Paper 886

Nikolic Deric T, Neyrinck J, Seghers E, Tsakiridis E (2020) Museums and intangible cultural heritage. Towards a third space in the heritage sector. Werkplaats immaterieel erfgoed

Nunnally JC (1994) Psychometric theory 3E. Tata McGraw-Hill Education

Or MH, Berkovich I (2023) Participative decision making in schools in individualist and collectivist cultures: the micro-politics behind distributed leadership. Educ Manag Adm Leadersh 51(3):533–553

Organ DW (1988) Organizational citizenship behavior: the good soldier syndrome. Lexington Books/D.C. Heath and Company

Palumbo R, Manna R, Cavallone M (2022) The managerialization of museums and art institutions: perspectives from an empirical analysis. Int J Organ Anal 30(6):1397–1418

Park J, Lee K-H (2020) Organizational politics, work attitudes and performance: the moderating role of age and public service motivation (PSM). Int Rev Public Adm 25(2):85–105

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88:879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Rasheed R, Rashid A, Amirah NA, Afthanorhan A (2023) Quantifying the moderating effect of servant leadership between occupational stress and employee in-role and extra-role performance. Calitatea 24(195):60–68

Sarros JC, Cooper BK, Santora JC (2011) Leadership vision, organizational culture, and support for innovation in not-for-profit and for-profit organizations. Leadersh Organ Dev J 32(3):291–309

Schwarz G, Eva N, Newman A (2020) Can public leadership increase public service motivation and job performance? Public Adm Rev 80(4):543–554

Solinger ON, Jansen PG, Cornelissen JP (2020) The emergence of moral leadership. Acad Manag Rev 45(3):504–527

Steiger JH (1990) Structural model evaluation and modification: an interval estimation approach. Multivar Behav Res 25(2):173–180

Syed F, Raja U, Naseer S (2023) Dark personality in dark times: How dark triad personality interacts with injustice and politics to influence detachment and discretionary behaviours. Can J Adm Sci/Rev Can Sci Adm 40(1):50–66

Tripathi D, Singh S, Varma A (2023) Perceptions of politics and organizational citizenship behavior: political skill and conscientiousness as moderators. J Asia Bus Stud 17(1):170–184

Tziner A, Drory A, Shilan N (2021) Perceived organizational politics, leadership style and resilience: how do they relate to OCB, if at all. Int Bus Res 14(2):1–1

Vigoda-Gadot E (2007) Redrawing the boundaries of OCB? An empirical examination of compulsory extra-role behavior in the workplace. J Bus Psychol 21:377–405

Vigoda-Gadot E, Beeri I (2011) Change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior in public administration: the power of leadership and the cost of organizational politics. J Public Adm Res Theory 22(3):573–596

Vigoda-Gadot E, Drory A (2006) Handbook of organizational politics. Edward Elgar Publishing

Vilarino del Castillo D, Lopez‐Zafra E (2022) Antecedents of psychological capital at work: a systematic review of moderator–mediator effects and a new integrative proposal. Eur Manag Rev 19(1):154–169

Walumbwa FO, Avolio BJ, Gardner WL, Wernsing TS, Peterson SJ (2008) Authentic leadership: development and validation of a theory-based measure†. J Manag 34(1):89–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307308913

Williams LJ, Anderson SE (1991) Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J Manag 17(3):601–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700305

Wright BE, Pandey SK (2008) Public service motivation and the assumption of person—organization fit: testing the mediating effect of value congruence. Adm Soc 40(5):502–521

Xiong K, Lin W, Li JC, Wang L (2016) Employee trust in supervisors and affective commitment: the moderating role of authentic leadership. Psychol Rep 118(3):829–848

Young IM (2020) Justice and the politics of difference. In: The new social theory reader. Routledge, pp. 261–269

Zhang Y, Guo Y, Zhang M, Xu S, Liu X, Newman A (2022) Antecedents and outcomes of authentic leadership across culture: a meta-analytic review. Asia Pac J Manag 39(4):1399–1435

Acknowledgements

This study is financed by the Jiangsu Funding Program for Excellent Postdoctoral Talent (No. 2022ZB646), Philosophy and Social Science Research Innovation team project in Jilin University (No. 2022CXTD17), Jilin Provincial Social Science Foundation Project (No. 2022B180), Ministry of Education Humanities and Social Sciences Research Project (No. 20YJCZH064), and Postgraduate Education Reform Project of Jiangsu Province (No. JGKT22_C091).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: MA; methodology: MA, ZM, and WH; software: MA; validation: ML and GX; formal analysis: MA; investigation: ML and WH; resources: ZM and ML; writing—original draft preparation: MA; writing—review and editing: all authors contributed equally; supervision: ML and ZM.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study received ethical clearance from the Institutional Review Board of Jiangsu University, China (Approval No. JUIRB/15893/2024) on January 3, 2024. All procedures complied with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Before participation, all participants were thoroughly informed about the study's objectives and procedures. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants on January 8, 2024.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Asif, M., Ma, Z., Li, M. et al. Authentic leadership: bridging the gap between perception of organizational politics and employee attitudes in public sector museums. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 47 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04310-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04310-9