Abstract

Topics oriented towards classroom dynamics have garnered considerable attention from the academic community, given the pivotal and illuminating role educators in tertiary institutions embody in facilitating students’ learning processes. This role is particularly crucial in the milieu of the COVID-19 pandemic, a period during which students’ learning engagement is susceptible to being adversely affected due to necessary epidemic prevention and control measures. In light of this, this study aims to explore the impact of teachers’ transformational leadership styles on 483 students’ acquisition of generic skills within classroom settings under the context of institutional degrees of internationalization. The present study meticulously devises a comprehensive set of conceptual frameworks, drawing inspiration from the IEO model. This endeavor aims to empirically substantiate the interrelationships among transformational leadership, self-efficacy, collaborative learning, generic skills, and the degree of internationalization. This study examined the reliability and validity of all variable by the CFA (Confirmatory Factor Analysis) and Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) with BootStrap was employed to calculate the T-valueThe empirical outcomes elucidate that teachers’ transformational leadership has a positive impact on students’ self-efficacy and collaborative learning motivation. Self-efficacy and collaborative learning are important mediating factors in the relationship between teachers’ transformational leadership and students’ generic skills. Self-efficacy and collaborative learning have a positive and significant impact on generic skills and are positively correlated. Self-efficacy not only affects collaborative learning, but also moderates the relationship between transformational leadership and generic skills. The collaborative learning environment promotes the development of basic skills through mutual support and knowledge sharing among students. Notably, the degree of internationalization serves as a positive moderator, enhancing the relationship between transformational leadership, collaborative learning, and generic skills. The study concludes by proffering theoretical and practical implications derived from the research findings, thereby furnishing valuable insights and contributions designed to fortify the existing theoretical foundation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the academic discussion about student learning in higher education, much attention has been paid to the significant impact of the learning environment on students’ academic outcomes (Astin & Antonio, 2012). These environmental elements include campus climate, classroom environment, interpersonal dynamics, and the overall macro-environment (Astin, 1993; Astin, 2002). Collectively, these elements have an impact on students’ motivational drive, learning engagement, acquisition of expertise and skills, and ultimately learning outcomes (Adams & Velarde, 2021; Chan et al., 2017). The global upheaval caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has prompted transformative changes in students’ lives and academic pursuits (Niță & Guțu, 2023). As a result, the ability to skillfully navigate and adapt to these altered environments has become an indispensable skill for students in the post-pandemic era. Arguably, it has replaced the traditional emphasis on academic performance or achievement (Xie et al., 2019). Astin’s Input-Environment-Output (IEO) model (Astin, 1993; Astin, 2002) provides a powerful theoretical framework. The dynamic interaction between input antecedents and environmental factors on subsequent outputs is elucidated. The model continues to be a cornerstone of reference for countless studies investigating student learning processes (Astin & Antonio, 2012; Jones & Varga, 2021; Wawrzynski et al., 2012). Despite the widespread use of the IEO model, research specifically focusing on student adaptability is significantly lacking. This is especially true in the changing environment caused by COVID-19 (Zainuddin, 2024). It is important to acknowledge that students’ generic skills are not limited to adaptability, but encompass a range of key competencies acquired through the learning process (Chan et al., 2017; Freudenberg et al., 2011; Salam, 2018; Virtanen & Tynjälä, 2018). In light of this, this study seeks to adopt the IEO model as a lens to examine the developmental trajectory of generic skills, as well as the associated input and environmental precursors.

Teachers are indispensable inspirations and guides in the learning process of students. They become valuable resources for students by providing insightful advice and imparting expertise, thereby enhancing students’ motivation and engagement in the learning process (Liu et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2020; Freudenberg et al., 2011). This dynamic emphasizes the need to establish a constructive interaction between teacher leadership and student learning efforts (Öqvist & Malmström, 2016). This positive teacher-student relationship helps to create an environment where students can respond and tackle challenges with a proactive and positive attitude, acquiring enhanced knowledge and skills from their learning environment (Dunbar et al., 2018; Cha et al., 2015). The concept of transformational leadership seems to be the most suitable for cultivating teachers’ transformational leadership capabilities. Its theory is derived from Bandura’s social cognitive theory and Shamir’s concept-based self-charisma explanation. According to this view, schools enhance teachers’ leadership identities and values that reflect their organizational vision or mission by“recruiting”self-concepts and increasing compensation. These transformational leadership effects are the product of conditions that provide motivation for enhancing teachers’ transformational leadership abilities. Given the relative scarcity of research on teacher classroom leadership in academia, in-depth research on the potential positive impact of teachers exhibiting transformational leadership traits on student learning processes will provide substantial theoretical contributions to the input-environment-output (IEO) model (Liu et al., 2020; Astin & Antonio, 2012). Consistent with this discourse, this study intends to use teachers’ transformational leadership as a key input variable to elucidate its impact on student learning outcomes (Bass & Riggio, 2006; Bass Bernand (1990)).

At the environmental echelon, external factors influencing students’ learning can be delineated narrowly as any external elements impinging on students’ academic endeavors. Or more expansively and precisely, encompassing the macro-living environment, the on-campus learning milieu, and students’ individual psychological landscapes (Li et al., 2020; Buckner & Stein, 2020). The intricate interplay between environmental typologies and input variables exerts multifaceted impacts on the development of generic skills (Chan et al., 2017; Freudenberg et al., 2011; Salam, 2018; Virtanen & Tynjälä, 2018). For a nuanced understanding of students’ learning outcomes, it is imperative to dissect the on-campus learning environment and the individual psychological environment separately. The latter epitomizes individual psychological traits or cognitive dispositions, with a robust psychological environment acting as a catalyst for students’ proactive cognitive engagement and problem-solving efficacy, elements integral to students’ self-efficacy (Bayraktar & Jiménez, 2020; Li et al., 2020; Bandura, 1997). The on-campus learning environment plays a pivotal role in steering students towards active learning engagement, with diverse learning scenarios affording students ample opportunities to assimilate new knowledge (Liu et al., 2020; Isohätälä et al., 2019). Academic discourse highlights that learning paradigms crafted by educators encompass deep learning, shallow learning, and problem-oriented learning (Liu et al., 2020; Gokhale, 1995). While these paradigms, including learning, work-integrated learning, and service learning, are instrumental in enhancing students’ multifaceted skills, the emphasis predominantly resides on augmenting individual learning outcomes rather than fostering collaborative, mutually beneficial learning outcomes (Freudenberg et al., 2011). Pike et al. introduced the notion of collaborative learning, positing that fortifying collaborative endeavors among students in the formulation and deliberation of classroom assignments would invariably bolster students’ teamwork acumen and learning efficacy (Pike et al., 2012; Ruys et al., 2014). This collaborative approach can be perceived as an external learning scenario. Historical scholarship is predominantly engaged with students’ reactions to and effects on the external environment within the IEO model framework, seldom incorporating considerations pertaining to students’ internal psychological environment (Bayraktar & Jiménez, 2020; Astin, 1993). A simultaneous exploration of students’ learning processes from both internal, and external environmental perspectives would indubitably contribute to the enrichment of the theoretical underpinnings of the IEO model (Astin, 1993; Astin & Antonio, 2012). Hence, this study is poised to explore the nexus between self-efficacy, collaborative learning, and generic skills, viewed through the lens of internal psychology and the external environment (Bandura, 1997; Gokhale, 1995; Virtanen & Tynjälä, 2018).

In addition to the learning scenarios designed by educators, the external learning environment also includes the institutional level. Although the impact of the learning environment at the institutional level is relatively small compared to the faculty level, its impact is long-lasting, and stable, and complements faculty-level factors (Adams & Velarde, 2021; Hallinger, 2011). The internationalization of higher education has always received attention from the academic community, and is a key aspect of the broader education field (Buckner & Stein, 2020; Ramaswamy et al., 2021; Warwick, 2014). Through the prism of internationalization, higher education institutions can gain insight into various educational models, and practices and promote the continuous cultivation of students’ universal skills in learning environments, and curriculum design (Larbi & Fu, 2017; Neale et al., 2018; Trilokekar, 2010). Furthermore, students’ perception of a higher degree of institutional internationalization broadens their academic perspectives, and the guidance and inspiration provided by educators, thus improving their overall learning experience and outcomes (Neale et al., 2018; Larbi & Fu, 2017; Uys & Middleton, 2011). Therefore, this study aims to examine the enhanced relationship between faculty transformational leadership and environmental factors by including the degree of internationalization as a confounding variable, thereby gaining a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics that influence student learning and development (Roberts & Mancuso, 2014).

Literature review and hypotheses development

IEO model

Astin dedicated over three decades to the study and refinement of the Input-Environment-Outcome (I-E-O) model, employing it as a foundational framework for examining student engagement within institutions of higher education (Niță & Guțu, 2023; McCarthy, McNally, & Mitchell, 2022; Astin, 1993). The I-E-O acronym represents ‘input’, ‘environment’, and ‘outcome’, respectively, with the model’s primary objective being to evaluate the evolution or enhancement of students’ learning experiences under specific environmental conditions (Zainuddin, 2024; Nguyen et al., 2022; Astin & Antonio, 2012). The I-E-O model of Student Engagement is instrumental for various stakeholders—including educators, policymakers, instructors, and students—in understanding the mechanisms through which desired educational objectives can be achieved by aligning student experiences with the ambient university environment (Niță & Guțu, 2023; McCarthy et al., 2022; Kuh et al., 2005). This alignment is a burgeoning focus for scholars engaged in higher education research. Astin’s model accentuates student involvement in activities as a crucial input within the educational milieu and utilizes the I-E-O framework to elucidate the intricate relationships between the educational environment and levels of student engagement (Zainuddin, 2024; Nguyen et al., 2022; Astin, 1993; Astin & Antonio, 2012).

Furthermore, research conducted by Kuh et al. provides a detailed exposition of the environmental component encapsulated in Astin’s I-E-O model, highlighting the collaborative creation of an environment by both students and institutions, which is conducive to fostering positive student outcomes (Wawrzynski et al., 2012; Kuh et al., 2005). The present study engages with the theory of student engagement as posited by Astin (1993) and advocates for the aptness of the I-E-O model in gauging the impact exerted by higher education environments on student outcomes (Astin & Annino, 2012; Jones & Varga, 2021; Astin, 1993). The I-E-O model has been adopted extensively as a blueprint for a myriad of studies investigating various university outcomes, encompassing academic achievements, social competencies, personal abilities (Millunchick et al., 2021), persistence in educational pursuits (Astin, 1993), moral development, among other areas of focus (Millunchick et al., 2021; Astin & Antonio, 2012). This study is predicated on the distinctive characteristics of the I-E-O model, with a concentrated focus on examining the influence of both external environmental factors and internal psychological elements on students’ acquisition of general skills (Zainuddin, 2024; McCarthy, McNally, & Mitchell, 2022; Chan et al., 2017). It aims to delineate the relationships among students’ general skills, teachers’ transformational leadership, external environmental factors, and internal psychological dynamics. Within the context of this study, the input variable is identified as teachers’ transformational leadership, while the environment encompasses both external factors and internal psychological components. The study seeks to explore students’ general skills through the lens of interactions with teachers, collaborative learning endeavors with peers, and the environmental factors contributing to self-efficacy (Niță & Guțu, 2023; Nguyen et al., 2022; Li et al., 2020). Figure 1 shows the relationships among the three components of I-E-O model.

This figure outlines the research framework based on the Input-Environment-Output (IEO) model. It shows the hypothesized relationships among transformational leadership, self-efficacy, collaborative learning, and student generic skills, with the degree of internationalization as a moderating variable. Source: “What Works in College? Four Critical Years Revisited,” by A. W. Astin, 1993, p. 5.

Transformational leadership

Bass and Riggio proposed the theory of transformational leadership and pointed out that when leaders possess qualities such as collaboration, enthusiasm, empowerment, vision, and creativity, these attributes serve as catalysts for followers, engendering heightened motivation, robust performance, and the cultivation of shared values (Peng et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020; Bass & Riggio, 2006). Transformational leadership extends beyond a mere process wherein leaders transmit their emotions, attitudes, values, and beliefs to galvanize subordinates (Öqvist & Malmström, 2016; Liu et al., 2020). Significantly, in the evolution of transformational leadership theory, the seminal work of Bernard Bass and colleagues is paramount. They elucidated: (a) the specific behaviors leaders engage in that precipitate change within followers; (b) the mechanisms through which leaders effectuate change in followers; (c) the consequential relationships that emerge from the dynamic interactions between leaders and followers (Bass & Riggio, 2006; Siangchokyoo et al., 2020; Öqvist & Malmström, 2016). In essence, transformational leadership fosters the development and metamorphosis of followers, thereby enhancing individual and, consequently, organizational performance (Peng et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020).

In recent years, scholarship has noted that transformational leadership is epitomized by educators who not only motivate but also transcend the immediate needs and interests of their students (Bass & Riggio, 2006; Li & Liu, 2020). Such educators wield influence over students’ capabilities while instilling a deep-seated commitment to the attainment of predefined objectives (Bass & Riggio, 2006). These leaders, often characterized by a palpable confidence, routinely adopt approaches and embody traits deemed unconventional (Li & Liu, 2020). Through the application of transformational leadership principles, educators can exert a positive impact on both student behavior and perception (Öqvist & Malmström, 2016; Li & Liu, 2020). For instance, educators who embody transformational leadership principles are attentive to the unique needs and concerns of each student.

Additionally, Pounder found that teachers who were perceived as transformational impacted a variety of outcomes, including: additional student effort, increased student perceptions of leader effectiveness, and increased student satisfaction with the teacher (Pounder, 2008). Similarly, Harvey et al. studied the impact of teachers’ transformational leadership on college students (Harvey et al., 2003). The researchers used the constructs of charisma, personalized consideration, and intellectual stimulation as independent variables and examined their impact on students’ course-related attitudes. Researchers used these data to show that teacher transformational leadership is positively related to important outcome variables in a college classroom setting.

Self-efficacy

The concept of self-efficacy, initially introduced by Bandura within the framework of his Social Cognitive Theory, is articulated as the “conviction in one’s capacities to organize and execute the requisite courses of action to manage prospective situations” (Bandura, 1997). Essentially, self-efficacy is delineated as an individual’s confidence in their ability to navigate and succeed in specific situations or complete particular tasks (Bandura, 1997; Yokoyama, 2019). Within academic contexts, it is plausible to posit that learners endowed with elevated levels of self-efficacy exhibit enhanced motivation and, consequently, superior academic achievement, as they harbor the belief in their capability to realize set objectives (Yokoyama, 2019; Li et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2019). Throughout the educational journey, self-efficacy exerts a positive influence on facets such as learners’ motivation, cognitive prowess, academic enthusiasm, emotional regulation, and overall achievement (Peng et al., 2018; Li et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2019). Hence, a direct correlation between self-efficacy and academic performance is evident (Doménech-Betoret et al., 2017; Dunbar et al., 2018).

Furthermore, self-efficacy serves as a reliable predictor of students’ academic performance across various domains and educational levels (Liu et al., 2020; Peng & Yue, 2022; Li et al., 2020). It significantly impacts motivation, subsequently fostering self-regulated learning and influencing students’ engagement and success in their academic endeavors (Lent et al., 2018; Peng & Yue, 2022; Xie et al., 2019; Yokoyama, 2019). For instance, students with robust self-efficacy, when confronted with daunting tasks, do not succumb to fear of failure; instead, they persistently surmount challenges and are inclined to establish loftier goals (Bandura, 1997; Shi & Liu, 2013). In contrast, those with diminished self-efficacy tend to capitulate easily in the face of adversity, exhibiting reluctance to persevere or undertake decisive action (Zhang et al., 2021). Thus, self-efficacy emerges as a pivotal determinant influencing students’ academic outcomes, encapsulating their ability to execute specific tasks, attain academic success, and embody particular beliefs and attitudes (Li et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2019). Consequently, the influence of self-efficacy is acknowledged as a crucial predictor of students’ academic performance and their reactions to various academic challenges (Müller & Seufert, 2018; Bayraktar & Jiménez, 2020).

Empirical studies exploring the relationship between transformational leadership and self-efficacy describe characteristics of successful leaders, as summarized by Bass Bernand (1990): Resolutely goal-oriented, adept at problem solving, exuding unwavering loyalty and conviction A leader is the epitome of an individual who has: Demonstrated self-efficacy (Bass Bernand (1990); Bass & Riggio, 2006). Transformational leadership is a kind of leadership that can inspire and inspire. Teachers’ teaching methods of transformative leadership can create a more effective learning environment for students. Educational institutions are sustainable organizations that require effective educators and a successful learning environment for students. Teacher transformational leadership is a way for teachers to build encouraging relationships with students based on a shared vision for the curriculum that includes rigor; ethics; inspiration; motivation; compassion; compassion; and respect. Additionally, teaching using a transformational leadership approach provides students with the space, materials. And funds to develop confidence (Boyd, et al., 2019; Gomes et al., 2020; Yüner, 2020). Whether in-person, hybrid, or digital course formats, teachers are leaders in the classroom responsible for igniting student interest in the subject. Likewise, should include behaviors such as preparing for class; implementing effective teaching strategies; having high-quality interpersonal communication skills; and possessing the ability to influence and empower students in productive ways (DeDeyn, 2021; Noland & Richards, 2014). By imparting educational concepts, instilling values, and improving self-efficacy, educators can significantly enhance students’ learning engagement (Peng et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020; Li & Liu, 2020). Thus, empirical evidence highlights the potential correlation between transformational leadership and self-efficacy, with the former providing the latter with valuable resources for followers (Bayraktar & Jiménez, 2020; Li & Liu, 2020). Research confirms that self-efficacy is a mechanism by which transformational leaders can enhance their supportive attitudes toward change, and instill confidence in followers that change initiatives can produce desired results (Bayraktar & Jiménez, 2020).

Self-efficacy is closely related to the collaborative learning process. Students with high self-efficacy are better at setting learning goals, monitoring their own learning progress, and adopting effective strategies when encountering difficulties (Bartimote-Aufflick et al., 2016). Students with high self-efficacy are more likely to actively participate in collaborative learning activities because they believe that their abilities can contribute to the success of the group. These abilities are particularly important in collaborative learning because students need to coordinate and adjust their learning behaviors in groups to achieve common goals (Zimmerman, 2000). Self-efficacy also affects students’ emotions and social interactions in collaborative learning. Students with high self-efficacy are more able to maintain positive emotions when facing challenges and are more willing to cooperate and share knowledge with others. Such positive emotions and social interactions help create a supportive learning environment and promote the success of collaborative learning (Bandura, 1982).

Based on the above discussion, the following hypotheses can be put forward:

H1: Teachers’ transformational leadership is positively correlated with students’ sense of self-efficacy.

H9:Self-efficacy is positively correlated with collaborative learning.

Collaborative learning

In the nascent stages of research on collaborative learning, the phenomenon was delineated as encompassing a spectrum of learning behaviors, including but not limited to mutual inquiry, discussion, explanation, debate, and active participation in the crucible of knowledge construction (Ruys et al., 2014; Smith & MacGregor, 1992). Collaborative learning is also conceptualized as a strategic approach to learning wherein individuals within a cohort engage in interactive learning, navigate through challenges encountered during the learning process, and leverage their cognitive faculties to crystallize their learning beliefs (Hautala & Schmidt, 2019; Ruys et al., 2014; Shi & Liu, 2013; Gokhale, 1995). Chatterjee and Correi posit that collaborative learning fosters the development of learners’ interactive competencies across a myriad of dimensions—such as affective, cognitive, social, and metacognitive—unconstrained by rigid learning paradigms (Isohätälä et al., 2019; Wang & Lin, 2007).

Furthermore, collaborative learning activities are characterized by two distinct forms of interaction: cognitive and socio-emotional. The former entails active participation in cognitive processes such as thinking, reasoning, analysis, and elaboration of acquired knowledge, while the latter encompasses understanding and empathy amongst learners, which are quintessential for fostering cooperation (Isohätälä et al., 2019; Virtanen & Tynjälä, 2018). This approach signifies a paradigmatic shift from conventional teacher-centric or lecture-based educational environments prevalent in higher education institutions. Educators who incorporate collaborative learning methodologies often perceive themselves not merely as conduits of knowledge transfer but as architects of students’ knowledge experiences, adopting roles akin to coaches or facilitators in the learning process (Smith & MacGregor, 1992; Freudenberg et al., 2011). Collaborative learning has been hypothesized to enhance student motivation and engagement, with students within collaborative cohorts supporting and encouraging participatory learning behaviors (Xie et al., 2019; Dunbar et al., 2018).

Empirical studies exploring the intersection between collaborative learning and transformational leadership reveal that Hallinger’s extensive four-decade research on “leadership for learning” encompasses characteristics inherent to pedagogy, transformational leadership, and shared leadership (Hallinger’s, 2011). He proposed a “reciprocal influence” model accentuating the significance of leadership and learning and the indelible impact of the school environment on both facets. While the role of students as organizational members in the collaborative process has not been entirely obviated, there is a requisite for collaborative planning, process execution, and assumption of associated responsibilities (Campbell, 2018; Cha et al., 2015). Hence, the implementation of collaborative learning necessitates educators to establish formal organizational structures, adhere to standardized procedures, and exercise influence to mold student behavior (Campbell, 2018; Cha et al., 2015). This discourse provides empirical evidence suggesting a potential correlation between transformational leadership and collaborative learning. Transformational leaders engender acceptance of organizational change, stimulate innovation, and promote behaviors aligned with transformation (Campbell, 2017a; Campbell, 2018; Gabbar, Honarmand, & Abdelsalam, 2014), thereby creating a normative context where collaboration is valorized as a strategic imperative for addressing organizational challenges (Cha et al., 2015). Based on the aforementioned discussion, the following hypothesis can be formulated:

H2: Teacher transformational leadership is positively correlated with student collaborative learning.

Collaborative learning has been identified as a multifaceted construct, encompassing behavioral, emotional, cognitive, and social dimensions within the learning environment (Xie et al., 2019; Ruys et al., 2014). Within the ambit of group learning environments, collaborative learning entails a process characterized by mutual interpretation, discussion, and cooperation amongst students, aimed at the successful completion of assigned tasks (Xie et al., 2019; Shi & Liu, 2013). It is this essence of collaboration that significantly augments the learning experience for students. Engaging in dialogues with peers allows learners to elucidate course content and glean insights that might remain elusive when working independently (Xie et al., 2019; Hautala & Schmidt, 2019). Furthermore, heightened levels of self-efficacy have been correlated with superior academic achievements within collaborative peer groups (Bandura, 1997; Wang & Lin, 2007). Empirical studies have corroborated the assertion that students’ self-efficacy levels exert influence on their performance within collaborative learning environments (Wang & Lin, 2007; Dunbar et al., 2018). Consequently, the present study furnishes empirical evidence suggesting a potential linkage between self-efficacy and collaborative learning. Engaging in collaborative learning endeavors enhances students’ self-efficacy by affording them both direct and indirect access to the experiences of their peer group members. Research conducted by Araban et al. substantiates the claim that collaborative learning methodologies contribute to improvements in students’ academic performance and self-efficacy levels (Araban et al., 2012; Law et al., 2015). Based on the preceding discussion, the following hypothesis can be postulated:

H3: Student self-efficacy is positively correlated with student collaborative learning.

Generic skills

Over the past two decades, the discourse surrounding generic skills has engendered considerable debate amongst academia, business representatives, and various governmental agencies and councils (Ulger, 2016; Wilson et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2016; Virtanen & Tynjälä, 2018). Irrespective of the specific definition attributed to the term “generic skills,” the core of the concept implies that such skills epitomize the capacity to execute specific tasks or activities, predicated on a foundation of comprehensive knowledge gleaned from both direct experience and mediated learning. This encompasses a reliance on both tacit and explicit forms of knowledge. Within various professions and disciplines, there is a requisite for individuals to possess generic skills, organizational acumen, knowledge acquisition capabilities, and problem-solving skills (Virtanen et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2021; Freudenberg et al., 2011).

Numerous scholars have underscored the utility of generic skills as a metric for international educational comparisons, offering valuable insights for the enhancement of teaching quality (Tremblay et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2021; Virtanen & Tynjälä, 2018). As elucidated by Virtanen & Tynjälä (2018), acquiring a profound understanding of the essence of generic skills can facilitate improvements in curriculum design, the learning environment, and students’ comprehension of self-concept and role identity (Zhang et al., 2021; Virtanen & Tynjälä, 2018). Within the dynamic milieu of the teaching process, educators guide students through interactive engagements, thereby fostering a supportive social context that is conducive to skill acquisition and the development of core competencies (Freudenberg et al., 2011; Chan et al., 2017). Furthermore, generic skills possess inherent characteristics that, distinct from topic-specific knowledge or hard skills, contribute to the cognitive and emotional development of students (Freudenberg et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2021; Virtanen& Tynjälä, 2018). It is imperative for educators to meticulously identify and conceptualize these skills across various disciplines, thereby informing the development of learning activities aimed at fostering generic skills (Chan et al., 2017; Virtanen & Tynjälä, 2018).

Empirical studies have demonstrated that students characterized by high levels of self-efficacy tend to invest considerable effort and time, actively participating and setting challenging objectives to excel in their respective tasks and assignments (Chan et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2021; Bandura, 1997). Analogous findings were observed in research evaluating the relationship between self-efficacy perceptions in career decision-making (CDM) and associated skills. Bandura postulated a direct correlation between self-efficacy expectations and behavioral performance, with students possessing elevated levels of self-efficacy exhibiting a propensity for frequent and successful performance (Luzzo, 1993; Bandura, 1997). Additional research indicates that heightened self-efficacy is correlated with more effective learning and the utilization of learning skills (Robbins et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2021). Research conducted by Satoshi et al. (2009) on the self-efficacy of generic skills revealed that beyond the development of competencies and skill acquisition for curriculum tasks, it is crucial to cultivate a robust belief system that empowers students to successfully complete these tasks (Virtanen & Tynjälä, 2018; Zhang et al., 2021). This provides empirical substantiation for the correlation between generic skills and student self-efficacy (Chan et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2021; Virtanen & Tynjälä, 2018). Generic skills appear to constitute a component of the positive performance associated with self-efficacy (Komarraju et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2021; Virtanen et al., 2009). Consequently, this study furnishes empirical evidence suggesting a potential correlation between generic skills and self-efficacy, with researchers positing that self-efficacy may influence student motivation and enhance academic achievement (Zhang et al., 2021; Virtanen & Tynjälä, 2018). Based on the aforementioned discussion, the following hypothesis can be postulated:

H4: Student generic skills is positively correlated with student self-efficacy.

Gokhale delineated collaborative learning as a pedagogical approach wherein students of disparate performance levels collaboratively engage within small groups, aiming to attain a shared objective (Gokhale, 1995). Consequently, the triumph of an individual student potentially facilitates the success of peers within the group. Generic skills, as defined, embody the capabilities that aid students in various learning contexts to acquire, construct, and utilize knowledge pertaining to these skills (Bureau, 2005; Zhang et al., 2021). In essence, these skills serve as instrumental tools that enhance students’ learning processes (Virtanen et al., 2009). Presently, there are nine identified types of generic skills: (1) collaboration, (2) communication, (3) creativity, (4) critical thinking, (5) information technology, (6) computation, (7) problem-solving, (8) self-management, and (9) learning skills. Given their generic characteristics, these skills might inherently intersect and overlap (Chan et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2021). Educational institutions employ various terminologies to refer to the generic skills they offer, including transferable skills, general attributes, general abilities, or key skills (Barrie, 2007; Ulger, 2016). Empirical studies have elucidated that, unlike individualized learning approaches, collaborative learning significantly enhances the acquisition and development of students’ generic skills (Xie et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2021). Thus, the present study aims to furnish empirical evidence elucidating the potential correlation between self-efficacy and generic skills acquisition, leading to the formulation of the ensuing hypothesis:

H5: Student collaborative learning is positively correlated with student generic skills.

Since the early 1990s, there has been a pronounced preference among employers for hiring individuals possessing adept interpersonal skills (Ulger, 2016). For instance, within the realm of retail, emotional intelligence, leadership acumen, and decision-making prowess are deemed paramount (Leggett et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2016). In the sectors of industry and commerce, verbal communication proficiency is highlighted as a crucial competency; conversely, within academia, there is a heightened focus on overarching communication skills (Leveson, 2000; Leggett et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2021). Drawing from the aforementioned studies, it can be inferred that skills such as interpersonal and communication abilities are intricately linked with leadership qualities (Zhang et al., 2021). If students’ repertoire of generic skills encompasses these interpersonal and communication faculties, a plausible connection between generic skills and teacher leadership, inclusive of transformational leadership styles, can be postulated (Virtanen et al., 2009). Hence, this study endeavors to present empirical evidence signifying a potential correlation between transformational leadership and the acquisition of generic skills (Campbell, 2018; Zhang et al., 2021). It is posited by some scholars that examining generic skills within the framework of leadership yields more immediate and discernible impacts on outcomes compared to the study of leadership in isolation, or analysis of personality, values, or motivation (Zhang et al., 2021). Based on the preceding discourse, the ensuing hypothesis is proposed:

H6: Teacher transformational leadership indirectly affects students’ generic skills.

Degree of internationalization

Ansoff initially conceptualized the degree of internationalization, succinctly defining it as the extent of a firm’s operational presence in foreign markets (Ansoff, 1957). Subsequently, this definition was expanded, characterizing the degree of internationalization as the expansion beyond national borders and across diverse geographical locales globally (Zhou et al., 2016). Universities worldwide have integrated the concept of internationalization into their respective research domains, with empirical studies substantiating the benefits accruing to students, faculty, and administrative staff, thereby exerting a positive influence (Ramaswamy et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021).

However, the interpretation and implementation of internationalization within the higher education sector exhibit variability across different institutions. Numerous scholarly investigations posit that internationalization encompasses the infusion of international elements into the spectrum of activities, practices, and administrative processes undertaken by universities, thereby enhancing the educational and research paradigms (Warwick, 2014; Larbi & Fu, 2017; Neale et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2016). In essence, the term ‘internationalization’ encapsulates a global viewpoint on the educational and administrative methodologies deployed within university settings (Warwick, 2014; Neale et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2021). For institutions embarking on the path of internationalization, this process facilitates closer alignment of faculty with cutting-edge research methodologies, novel academic disciplines, and innovative ideas (Ramaswamy et al., 2021). It provides opportunities for collaboration with eminent experts from prestigious institutions worldwide, fostering knowledge transfer and skill acquisition, and granting students access to superior educational frameworks (Zhang et al., 2021).

Previous research has illuminated the mediating role of the degree of internationalization in the dynamic interplay between teacher competence and student development (Ramaswamy et al., 2021). In the context of the present study, variables such as teacher transfer leadership, student self-efficacy, and collaborative learning are postulated to be predictive indicators of the degree of internationalization, with the latter exerting influence over their behavioral outcomes (Zhang et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2016). Moreover, the degree of internationalization is hypothesized to function as a mediator between teachers’ transformational leadership and students’ self-efficacy and collaborative learning (Warwick, 2014; Larbi & Fu, 2017). Based on the foregoing discussion, the study advances the subsequent hypothesis:

H7: Degree of internationalization moderates the relationship between teacher transformational leadership and student self-efficacy and collaborative learning.

H7a: Degree of internationalization moderates the relationship between teacher transformational leadership and student self-efficacy.

H7b: Degree of internationalization moderates the relationship between teacher transformational leadership and collaborative learning.

Empirical evidence from preceding studies elucidates the mediating role of the degree of internationalization in the nexus between teacher competencies and student learning outcomes (Ramaswamy et al., 2021). As educational institutions endeavor to elevate the international standards pertaining to student learning outcomes, there is a concomitant inclination towards enhancing teacher competency and adopting specific leadership distribution models (Roberts & Mancuso, 2014; Adams & Velarde, 2021). These strategic shifts have been empirically validated to exert positive impacts on student learning outcomes (Robinson et al., 2008; Adams & Velarde, 2021). Within the framework of our research, variables such as teachers’ leadership acumen and students’ generic skills are postulated to serve as predictive indicators of the degree of internationalization (Zhang et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2016). The magnitude of internationalization, in turn, is anticipated to wield influence over their respective behaviors (Warwick, 2014; Larbi & Fu, 2017). Furthermore, the degree of internationalization is hypothesized to mediate the relationship between teachers’ transformational leadership and students’ acquisition of generic skills (Chan et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2021). Consequently, the ensuing hypothesis is formulated:

H8: Degree of internationalization moderates the relationship between teachers’ transformational leadership and students’ generic skills.

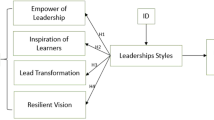

Building on the above arguments, this study thus present Fig. 2.

This framework illustrates the relationships among Transformation Leadership, Degree of Internationalization, Self-efficacy, Collaborative Learning, and Student Generic Skills. It conceptualizes how transformation leadership and internationalization influence self-efficacy and collaborative learning, which in turn contribute to the development of students’ generic skills.

Methodology

Sampling

This study endeavors to scrutinize the impact of teachers’ instructional leadership styles on students’ acquisition of generic skills within classroom settings, while concurrently examining students’ learning statuses, all within the context of institutional degrees of internationalization (Zhang et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2016). To secure a sample that is more emblematic of the population, purposive sampling is employed as the data collection strategy (Tremblay et al., 2012). Nonetheless, it is imperative to acknowledge that scholars have raised concerns regarding the potential introduction of sampling bias inherent to purposive sampling (Robinson et al., 2008). To mitigate such bias, meticulous criteria were established at both the school and student levels during the sampling phase to refine the selection of samples (Adams & Velarde, 2021).

Initially, the study targeted schools engaged in exchange student programs, those admitting international students, and those that have previously or are currently employing foreign teaching staff (Ramaswamy et al., 2021). Moreover, considering that first-year students possess limited insights into their schools’ internationalization efforts, only students enrolled in their second year or higher were considered eligible for participation in the study (Warwick, 2014). Thirdly, given that the study is situated within Mainland China where online classes have been necessitated due to COVID-19 prevention measures, students and schools exclusively engaged in online instruction were excluded to facilitate a more accurate understanding of teachers’ classroom management and leadership practices (Larbi & Fu, 2017). Data collection, conducted through the distribution of questionnaires between March and May 2022, encompassed eight universities located in the eastern coastal cities of Mainland China. Out of the 749 questionnaires retrieved, eight were invalidated, resulting in a total of 741 valid responses.

Within the cohort of 741 respondents, 58% identified as male while 42% were female. The participants were predominantly from social science disciplines, accounting for 54%, with the remaining 46% representing the natural sciences. A significant 64% were first-generation college students, and a substantial 79% harbored aspirations of participating in international exchange programs. The majority reported a monthly disposable income ranging between 2000 and 2500 USD (69%), followed by a bracket of 1500 to 2000 USD (20%).

Measures

Teachers’ transformational leadership is conceptualized as students’ perception of the extent to which educators facilitate critical thinking and active participation in learning processes within classroom settings. The scale designed by Liu et al. was chosen because it comprehensively captures the multifaceted nature of transformational leadership in educational contexts (Liu et al., 2020). This scale includes dimensions such as Idealized Influence (II), Intellectual Stimulation (IS), Individualized Consideration (IC), and Inspirational Motivation (IM), which align well with the study’s focus on critical thinking and active participation, cumulatively consisting of 16 items.

Self-efficacy was measured using the scale developed by Rigotti et al. (Rigotti et al., 2008). This scale was selected due to its robust psychometric properties and its wide application in educational research. The items on this scale are specifically designed to assess students’ beliefs in their abilities to successfully perform academic tasks, which is central to our study’s examination of self-efficacy as a predictor of collaborative learning and generic skills development.

Collaborative learning was assessed using the scale by Pike, Smart, and Ethington (Pike et al., 2012). This scale was chosen because it effectively measures the extent of student engagement in collaborative activities, which is crucial for understanding how students interact and learn together. The scale’s items are designed to capture various aspects of collaboration, including communication, teamwork, and shared responsibility, all of which are pertinent to our research on collaborative learning, comprising a total of three items.

Student generic skills were measured using the scale from Natoli, Jackling, and Seelanatha (Natoli et al., 2014). This scale was selected due to its comprehensive coverage of key generic skills such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and communication. The items on this scale are particularly relevant to our study as they reflect the essential skills that students need to succeed both academically and professionally, incorporating a total of six items.

The degree of internationalization was assessed using Bartell’s scale (Bartell’s, 2003). This scale was chosen because it provides a thorough measure of how internationalization is integrated into the curriculum and the overall educational environment. The scale’s items address various dimensions of internationalization, including curriculum content, international student exchange, and faculty involvement in international activities, all of which are critical to the study’s examination of the impact of internationalization on student outcomes, identifying six indicators pivotal for achieving exemplary levels of internationalization within educational institutions. These indicators have been operationalized for the purposes of this research. To verify the efficacy of the measurement instruments, a preliminary distribution of 50 questionnaires was conducted, yielding satisfactory reliability results (α = 0.874).

Results and analysis

Measurement model

CFA (Confirmatory Factor Analysis) was employed to authenticate the hypothesized factor structure, with the objective of ascertaining whether any modifications were imperative. Following the methodology articulated by Anderson and Gerbing (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988), a two-step CFA approach was executed. This entailed evaluating each construct in isolation, followed by an assessment of the overarching measurement model. Both the Cronbach’s alpha and CR (Composite Reliability) values surpassed the stipulated minimum benchmark of 0.7, thereby indicating satisfactory reliability (Hair et al., 2011). Concurrently, the AVE (Average Variance Extracted) values exceeded the predetermined threshold of 0.50 (Hair et al., 2011), signifying that the convergent validity of the model is commendable. In the empirical analysis conducted in the present study, factor loadings were observed to be in excess of 0.5, with Cronbach’s alpha values exceeding 0.857, CR values surpassing 0.905, and AVE values being greater than 0.664 (refer to Table 1 for details). Discriminant validity was scrutinized through the examination of correlations between variables and constructs, and by juxtaposing the square root of AVE values against the correlations observed between constructs, as per the criteria established by Fornell and Larcker (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Moreover, to ascertain discriminant validity, Henseler et al. recommended the use of the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) of correlations, derived from the multitrait-multimethod matrix (Henseler et al., 2016). In our study, all HTMT values for the constructs were below 0.9, indicating satisfactory discriminant validity. As detailed in Table 3, the results confirm that the constructs possess satisfactory discriminant validity. The outcomes derived from the examination of constructs substantiate that the discriminant validity is indeed satisfactory Table 2.

The IPMA results, illustrated in Fig. 3, show that Transformational Leadership and Self-Efficacy have high importance but relatively low performance, indicating that improvements in these areas could significantly enhance overall model outcomes. Conversely, Collaborative Learning demonstrates high performance but lower importance, suggesting it is effectively implemented but may not be the primary focus for improvement. The Degree of Internationalization exhibits moderate importance and performance, highlighting its balanced role and indicating potential for enhancement to improve overall outcomes.

The IPMA results demonstrate the importance and performance of key constructs, including Transformational Leadership, Self-Efficacy, Collaborative Learning, and the Degree of Internationalization. The map highlights areas of high importance but low performance (e.g., Transformational Leadership and Self-Efficacy), suggesting potential improvement priorities.

Testing of structural model

In this study, Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was selected as the principal analytical method for data analysis, with BootStrap employed to calculate the T-value of the path coefficient. This approach facilitated the estimation of the results pertaining to the hypothesis tests proposed herein. PLS-SEM was chosen due to its flexibility and suitability for handling complex models and multivariate relationships, as well as its ability to accommodate non-normal data distributions (Hair et al., 2011). Moreover, despite our sample size exceeding 700, PLS-SEM remains appropriate as it provides robust estimates and higher model explanatory power in large sample contexts (Sarstedt et al., 2020). The overall model fit was evaluated using the Stone-Geisser Criterion (Q2), the Coefficient of Determination (R2), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residuals (SRMR) (Peng et al., 2023). The obtained R2 values exceeded the benchmark of 0.30, Q2 values were positive, and the SRMR was below the threshold of 0.05.

Upon verification of a satisfactory level of reliability and validity in the measurement results, hypothesis testing was undertaken. As delineated in Table 3 and Fig. 4, the findings reveal that teachers’ transformational leadership exerts positive and significant impacts on both self-efficacy (β = 0.472, p < 0.001) and collaborative learning (β = 0.382, p < 0.001), though not on generic skills (β = 0.077, p > 0.05). Consequently, Hypotheses 1 (H1) and 2 (H2) received support, while Hypothesis 6 (H6) did not. Furthermore, the results indicate that self-efficacy positively and significantly influences collaborative learning (β = 0.300, p < 0.001) and generic skills (β = 0.374, p < 0.001), thereby supporting Hypotheses 3 (H3) and 4 (H4). Collaborative learning was also found to positively affect generic skills (β = 0.143, p < 0.05), leading to the confirmation of Hypothesis 5 (H5).

The figure presents the structural model with path coefficients, indicating the relationships between constructs. Significant paths (e.g., Transformational Leadership → Self-Efficacy, β = 0.472, p < 0.001) and non-significant paths (e.g., Transformational Leadership → Generic Skills, β = 0.077, p > 0.05) are labeled accordingly. The model explains variance in Self-Efficacy, Collaborative Learning, and Generic Skills through key predictors.

Finally, the study examined the moderating effects exerted by the degree of internationalization on the relationships among transformational leadership, self-efficacy, collaborative learning, and generic skills. As depicted in Table 4 and Fig. 2, the degree of internationalization was found to have significant positive moderating effects on the relationship between transformational leadership and collaborative learning (β = 0.066, p < 0.05), though not on the relationship between transformational leadership and self-efficacy (β = 0.028, p > 0.05). This supports Hypothesis 7b (H7b) while refuting Hypothesis 7a (H7a). Additionally, a significant positive moderating effect of the degree of internationalization (β = 0.085, p < 0.01) on the relationship between transformational leadership and generic skills was substantiated, lending support to Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Discussion

The pivotal role of teachers within the classroom setting, as corroborated by numerous studies, is indisputable (Robinson et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2021). Specifically, the manner in which teachers navigate students through learning scenarios and engagement in the classroom, thereby enhancing their acquisition of essential knowledge and skills, is a pressing topic warranting immediate discussion (Roberts & Mancuso, 2014; Adams & Velarde, 2021). Utilizing the Input-Environment-Output (IEO) model as a foundational framework, this study endeavors to construct and validate a model elucidating the influence exerted by teachers’ leadership within the classroom (Warwick, 2014; Larbi & Fu, 2017). This model incorporates measurement variables including teacher transformational leadership, self-efficacy, collaborative learning, and generic skills (Zhou et al., 2016; Ramaswamy et al., 2021). With the international environment and degree of the school serving as moderating variables, the study aims to decipher whether the degree of internationalization impinges upon the relationship between teachers’ transformational leadership and the aforementioned variables (Neale et al., 2018).

Initially, this study asserts that teachers’ transformational leadership exerts a positive influence on students’ self-efficacy and collaborative learning. The findings indicate that transformational leadership significantly enhances both self-efficacy and collaborative learning. These outcomes align with the assertions made by Campbell, Liu et al., and Peng et al., suggesting that transformational leadership effectively navigates students towards cultivating elevated levels of self-confidence and adopting diverse learning styles (Campbell, 2017a, 2018; Liu et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2018). This approach facilitates a departure from traditional thought paradigms, fostering the acquisition of a diverse array of problem-solving knowledge (Zhang et al., 2021). Moreover, the findings resonate with the imperative to employ a multifaceted leadership approach within classroom management, diverging from historical practices where leadership was exclusively exerted from the principal’s perspective (Liu et al., 2020). This multifaceted approach plays a pivotal role within the Input-Environment-Output (IEO) model, serving as a crucial input (Peng & Yue, 2022). Consequently, students experience inspiration derived from both internal and external factors. However, the study’s findings reveal that teachers’ transformational leadership does not significantly impact students’ generic skills. This outcome is not only misaligned with the study’s initial hypotheses but also starkly contrasts with the findings presented by Wefald and van Lttersum. A plausible explanation for this discrepancy may reside in the nature of teachers’ transformational leadership, which primarily aims to guide and inspire students to alter their learning attitudes and methodologies (Peng & Yue, 2022). This approach encourages continuous skill and ability accumulation throughout the learning process, as depicted in the Input-Process-Output and Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) models (Peng & Yue, 2022; Zhang et al., 2021). These models utilize various mediators to enhance subsequent behaviors and responses. Although these results are not statistically significant, they underscore the importance of mediation effects within various theoretical models, thereby enriching the significance and understanding of the mediation effect within the IEO model.

Furthermore, this study posits that self-efficacy exerts a positive influence on collaborative learning and generic skills. The findings illustrate that self-efficacy significantly and positively impacts collaborative learning and generic skills, aligning with previous research outcomes presented by Chan, Komarraju et al., and Zhang et al. (Chan et al., 2017; Komarraju et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2021). Elevated levels of self-efficacy amongst students correlate with increased confidence in completing academic assignments and tasks, subsequently fostering the development of enhanced generic skills (Zhang et al., 2021). This study not only corroborates the influence of self-efficacy on collaborative learning and generic skills through the IEO model but also echoes assertions made within self-efficacy-related theoretical frameworks, such as Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) (Bandura, 1986), Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT) (Lent, Brown, & Hackett, 1994), and general self-efficacy theory (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995). Within these frameworks, self-efficacy is conceptualized as a reflection of an individual’s belief in their capability to execute tasks and achieve goals (Bandura, 1986). This sense of self-assurance and zeal towards goal attainment are pivotal factors influencing a myriad of outcome variables, including but not limited to learning behaviors and responses (Komarraju et al., 2010).

This study posits that collaborative learning positively influences generic skills. The findings reveal that students’ active participation in collaborative learning significantly enhances generic skills (Araban et al., 2012; Law et al., 2015). Engagement in learning is indicative of students’ acknowledgment and active participation within the learning environment, while collaborative learning entails students working cooperatively to address and resolve coursework challenges (Johnson & Johnson, 2009). Through a lens of reciprocity, students mutually motivate and facilitate each other’s developmental journey (Slavin, 2014). The outcomes of this study align with the research conducted by Araban et al. and Law et al., underscoring that heightened engagement in collaborative learning models fosters improvements in generic skills through the process of mutual learning. Furthermore, it is widely acknowledged among scholars that a high degree of learning engagement is reflective of students’ dedication and effort towards learning and academic achievement (Araban et al., 2012; Law et al., 2015; Fredricks et al., 2004). Particularly within learning environments characterized by shared objectives, students are likely to experience increased support and encouragement from peers, facilitating the completion of academic tasks through collaborative efforts (Gillies, 2016). Environmental factors are crucial determinants in students’ learning trajectories (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Historically, there has been limited scholarly discussion regarding the degree of internationalization of educational institutions in the context of students’ learning environments (Knight, 2004). Concurrently, the importance of internationalization for institutional development has been emphasized by the academic community (Altbach & Knight, 2007). Hence, this study incorporates the degree of internationalization as a moderating environmental variable to explore its influence on the relationships between the variables within the proposed structural model (Knight, 2004). The findings suggest that the degree of internationalization exerts a positive and significant moderating effect on the relationships between transformational leadership, collaborative learning, and generic skills (Buckner & Stein, 2020; Stensaker et al., 2019). However, no significant moderating effect was observed on the relationship between transformational leadership and self-efficacy (Ramaswamy et al., 2021). These findings resonate with the research outcomes presented by Buckner and Stein, Stensaker et al. (2019), and Ramaswamy et al. (Buckner & Stein, 2020; Stensaker et al., 2019; Ramaswamy et al., 2021). The findings suggest that as institutions become increasingly internationalized, students, exposed to diverse cultural influences and pedagogical approaches, are more receptive to inspirational leadership within the classroom (Knight, 2004). This receptivity enhances their motivation and investment in learning, subsequently leading to the improvement of generic skills (Zhang et al., 2021). The findings of this study also echo the significance of environmental factors within the IEO model as articulated by Kuh et al., proposing that the introduction of relevant environmental factors for verification purposes serves to strengthen the relationship between input and output variables within the model (Kuh et al., 2005).

Finally, the findings reveal that students with higher self-efficacy are more likely to actively participate in collaborative learning, which in turn enhances their acquisition of generic skills. Importantly, the results show that self-efficacy and collaborative learning serve as significant mediators in the relationship between teachers’ transformational leadership and students’ generic skills. This indicates that enhancing students’ self-efficacy and promoting collaborative learning are crucial pathways through which transformational leadership can positively impact students’ acquisition of generic skills. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have highlighted the importance of self-efficacy in educational settings (Bandura, 1997; Peng et al., 2018). This study extends these findings by demonstrating that self-efficacy not only influences collaborative learning but also mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and generic skills. Furthermore, the mediating role of collaborative learning aligns with Gokhale’s (1995) assertion that collaborative learning enhances critical thinking and problem-solving skills. By demonstrating that collaborative learning mediates the impact of transformational leadership on generic skills, our study supports the idea that collaborative learning environments foster the development of essential skills through mutual support and knowledge sharing among students. However, it is important to note that while our findings highlight the significant mediating effects of self-efficacy and collaborative learning, they also suggest the need for further research to explore other potential mediators and moderators. For instance, environmental factors such as institutional support and resources could also play a role in shaping the effectiveness of transformational leadership in different educational contexts (Freudenberg et al., 2011; Virtanen & Tynjälä, 2018).

Conclusions

This study introduces a comprehensive research model grounded in the IEO framework, elucidating the relationships among transformational leadership, self-efficacy, collaborative learning, degree of internationalization, and student generic skills. It advances several theoretical implications derived from the findings, alongside educational and practical ramifications for educators and administrative professionals within academic institutions. Primarily, the role of educators as pivotal leaders within the classroom environment is accentuated. The employment of diverse leadership styles by educators invariably engenders substantial disparities in students’ learning outcomes and engagement levels. Within the realm of higher education, there is a pronounced emphasis on facilitating students’ acquisition of deep learning and critical thinking competencies; however, not all educators inherently possess the transformational leadership qualities requisite for guiding and inspiring students. Consequently, the study advocates for educators to meticulously craft and assign tasks that are inherently inspiring and conducive to independent learning during the instructional process, thereby bolstering students’ confidence and proficiency in executing tasks, including but not limited to case analysis, discussion, and focus group reporting.

Enhancing students’ self-efficacy proves instrumental in fostering collaborative learning environments, which subsequently augment students’ generic skills. Through the implementation of a curriculum designed around teamwork, interaction and communication amongst students are fortified, facilitating the continuous flow and effective dissemination of professional knowledge within the group. This investigation recommends that educators incorporate an increased number of task-oriented activities into the curriculum design. Such an inclusion would ensure students engage in thorough discussions and employ creative and critical thinking skills pertinent to the professional knowledge encapsulated within the curriculum. It is especially crucial to integrate challenges encountered in everyday life, practical approaches to problem-solving, and the acquisition of corresponding knowledge into the curriculum to render the learning experience more applicable and insightful for students.

In conclusion, the degree of internationalization within an educational institution exerts a significant moderating effect, serving as a crucial explanatory variable within the framework of the IEO model. Nonetheless, achieving a substantial level of internationalization within a school necessitates sustained efforts and is invariably contingent upon the endorsement and support from institutional leaders. The cultivation of an internationalized learning environment is imperative as it fosters interaction between educators and students, thereby amplifying the students’ learning outcomes. Consequently, it is recommended that administrative bodies of educational institutions incrementally enhance internationalization indicators by expanding curricula, facilitating student exchange programs, and refining teacher recruitment processes. Such strategic initiatives are anticipated to not only improve the international ambiance of the school but also to fortify students’ global perspectives and vision.

Limitations

While this study furnishes numerous theoretical and practical implications and augments the understanding and insights pertaining to the IEO model, it is not without limitations in its research design. Initially, this research endeavors to validate the measurement of the internationalization variable through a cognitive survey, utilizing longitudinal data garnered from students’ perspectives, thereby ascertaining students’ perceptions of their institution’s degree of internationalization at a specific temporal juncture. Nonetheless, it is imperative to acknowledge that the degree of internationalization within a school is subject to dynamic adjustments and alterations, evolving in tandem with the changing status of collaborations between the institution in question and international educational bodies. Consequently, future researchers are advised to devise a comprehensive index for measuring the degree of internationalization, systematically investigate the level of internationalization within schools across different time periods, and corroborate these findings with cross-sectional data. Such methodological refinements are anticipated to enhance the robustness and completeness of subsequent studies.

Moreover, this study predominantly employs collaborative learning as the principal learning style to ascertain the extent of students’ engagement in learning. While the research affirms the pivotal role of collaborative learning within the proposed model and its positive influence on students’ generic skills, it is crucial to acknowledge that myriad other variables could potentially guide students towards enhanced focus and commitment to learning. These include, but are not limited to, problem-oriented learning, deep learning, and exploratory learning. Hence, future scholars are encouraged to pinpoint and incorporate appropriate learning variables that align with distinct theoretical frameworks, thereby enriching the theoretical tapestry underpinning this area of study.

Thirdly, the present study encompasses a sample of college students residing in coastal cities within mainland China, yielding a total of 741 valid questionnaires. While the validity of the questionnaires and scales employed has been duly verified, the generalizability of the findings warrants further enhancement. Given the distinct environmental contexts between universities located in the western regions of mainland China and those situated along the eastern coast, substantial disparities in students’ perceptions and cognitions are plausible. Consequently, it is recommended for future researchers to extend their investigations to college students in the western regions of mainland China. Engaging in comparative research would illuminate the variations and biases introduced by regional variables, thereby contributing to a more nuanced understanding of the phenomena under study.

Data availability

This study involves primary data collected through survey questionnaires. To protect respondents’ privacy and comply with ethical guidelines, the raw datasets are not publicly accessible. However, de-identified datasets may be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, provided such requests comply with institutional and ethical requirements.

References

Adams D, Velarde JM (2021) Leadership in a Culturally Diverse Environment: Perspectives from International School Leaders in Malaysia. Asia Pac J Educ 41(2):323–335

Ansoff HI (1957) Strategies for Diversification. Harv Bus Rev 35(5):113–124

Anderson JC, Gerbing DW (1988) Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull 103(3):411

Astin AW (1993) What Works in College? Four Critical Years Revisited. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Astin AW (2002) Assessment for Excellence. Oryx Press, Westport, CT

Astin A, Antonio AL (2012) Assessment for excellence: The philosophy and practice of assessment andevaluation in higher education. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers

Araban S, Zainalipour H, Saadi RHR, Javdan M, Sezide K, Sajjadi S (2012) Study of Cooperative Learning Effects on Self-efficacy and Academic Achievement in English Lesson of High School Students. J Basic Appl Sci Res 2(9):8524–8526

Altbach PG, Knight J (2007) The internationalization of higher education: Motivations and realities. J Stud Int Edu, 11(3–4), 290–305

Bandura A (1997) Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York

Bartell M (2003) Internationalization of Universities: A University Culture-based Framework. High Educ 45:43–70

Barrie SC (2007) A conceptual framework for the teaching and learning of generic graduate attributes. Stud High Educ 32(4):439–458

Bass BM, Riggio RE (2006) Transformational Leadership. Psychology press

Bass Bernand, M (1990). Stogdill. g Leadership

Bayraktar S, Jiménez A (2020) Self-efficacy as a Resource: a Moderated Mediation Model of Transformational Leadership, Extent of Change and Reactions to Change. J Organ Change Manag 41(2):32–35

Buckner E, Stein S (2020) What Counts as Internationalization? Deconstructing the Internationalization Imperative. J Stud Int Educ 24(2):151–166

Bandura A (1986) Social Foundations of Thought and Action, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. The Health Psychology, Sage Publications, New Delhi, 94–106

Boyd BL, Getz CA, Guthrie KL (2019) Preparing the Leadership Educator Through Graduate education. N. Directions Stud Leadersh 1(64):105–121

Bartimote-Aufflick K, Bridgeman A, Walker R, Sharma M, Smith L (2016) The study, evaluation, and improvement of university student self-efficacy. Stud High Educ 41(11):1918–1942

Bandura A (1982) Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychologist 37(2):122

Bureau B (2005) Economie des instruments de protection de l'environnement. Revue française d'économie 19(4):83–110

Bronfenbrenner U (1979) Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. Am Psychol 34(10):844

Campbell JW (2017a) Felt Responsibility for Change in Public Organizations: General and Sector-specific Paths. Public Manag Rev 20(2):232–253

Campbell JW (2018) Efficiency, Incentives, and Transformational Leadership: Understanding Collaboration Preferences in the Public Sector. Public Perform Manag Rev 41(2):277–299

Cha J, Kim Y, Lee JY, Bachrach DG (2015) Transformational Leadership and Inter-team Collaboration: Exploring the Mediating Role of Teamwork Quality and Moderating Role of Team Size. Group Organ Manag 40(6):715–743

Chan CK, Zhao Y, Luk LY (2017) A Validated and Reliable Instrument Investigating Engineering Students’ Perceptions of Competency in Generic Skills. J Eng Educ 106(2):299–325

Dunbar RL, Dingel MJ, Dame LF, Winchip J, Petzold AM (2018) Student Social Self-efficacy, Leadership Status, and Academic Performance in Collaborative Learning Environments. Stud High Educ 43(9):1507–1523

Doménech-Betoret F, Abellán-Roselló L, Gómez-Artiga A (2017) Self-efficacy, satisfaction, and academic achievement: the mediator role of Students’ expectancy-value beliefs. Front psychol 8, 1193

DeDeyn R (2021) Teacher Leadership and Student Outcomes in a US University Intensive English Program. Electron J Engl a Second Lang 24(4):1–23

Freudenberg B, Brimble M, Cameron C (2011) WIL and Generic Skill Development: The Development of Business Students’ Generic Skills Through Work-integrated Learning. Asia-Pac J Cooperative Educ 12(2):79–93

Fredricks JA, Blumenfeld PC, Paris AH (2004) School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev Edu Res 74(1):59–109

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Market Res 18(1):39–50

Gabbar HA, Honarmand N, Abdelsalam AA (2014) Transformational Leadership and Its Impact on Governance and Development in African Nations: Analytical Approach. J Entrepreneurship Organ Manag 3(2):1–12

Gillies RM (2016) Cooperative learning: Review of research and practice. Aust J Teacher Educ (Online) 41(3):39–54

Gokhale AA (1995) Collaborative Learning Enhances Critical Thinking. J Technol Educ 7(1):9–12

Gomes ME, Kime L, Bush JM, Myers AB (2020) The Electronic Media Fast and Student WellBeing: An Exercise in Transformational Teaching. Teach Psychol 3(2):1–7

Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2011) PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J Mark Theory Pract 19(2):139–152

Hallinger P (2011) Leadership for learning: Lessons from 40 Years of Empirical Research. J Educ Adm 49(2):125–142

Hautala J, Schmidt S (2019) Learning Across Distances: an International Collaborative Learning Project Between Berlin and Turku. J Geogr High Educ 43(2):181–200

Harvey S, Royal M, Stout D (2003) Instructor’s Transformational Leadership: University Student Attitude and Ratings. Psychol Rep. 92(2):395–402

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2016) Testing Measurement Invariance of Composites Using Partial Least Squares. Int Mark Rev 33(3):405–431

Isohätälä J, Näykki P, Järvelä S (2019) Cognitive and Socio-emotional Interaction in Collaborative Learning: Exploring Fluctuations in Students’ Participation. Scandinavian J Educ Res 1–21

Komarraju M, Musulkin S, Bhattacharya G (2010) Role of student–faculty interactions in developing college students’ academic self-concept, motivation, and achievement. J Coll Stud Dev 51(3):332–342

Knight J (2004) Internationalization remodeled: Definition, approaches, and rationales. J Stud Int Edu 8(1):5–31

Jones SE, Varga MD (2021) Students Who Experienced Foster Care are on Campus: Are Colleges Ready? Ga J Coll Stud Aff 37(2):3–19

Johnson DW, Johnson RT (2009) An educational psychology success story: Social interdependence theory and cooperative learning. Educ Res 38(5):365–379

Kuh GD, Kinzie J, Schuh JH, Whitt EJ (2005) Assessing Conditions to Enhance Educational Effectiveness: The Inventory for Student Engagement and Success. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Larbi FO, Fu W (2017) Practices and Challenges of Internationalization of Higher Education in China: International Students’ Perspective – A Case study of Beijing Normal University’. Int J Comp Educ Dev 19(2):78–96

Law QPS, Chung JWY, Leung CC, Wong TKS (2015) Enhancement of Self-efficacy and Interest in Learning English of Undergraduate Students with Low English Proficiency Through a Collaborative Learning Programme. Am J Educ Res 3(10):1284–1290

Leggett M, Kinnear A, Boyce M, Bennett I (2004) Student and staff perceptions of the importance of generic skills in science. High Educ Res Develop 23(3):295–312

Lent RW, Brown SD, Hackett G (1994) Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. J Vocat Behav 45(1):79–122

Leveson NG (2000) System safety in computer-controlled automotive systems. SAE Trans 109:287–294

Li H, Liu J, Zhang D, Liu H (2020) Examining the Relationships Between Cognitive Activation, Self-efficacy, Socioeconomic Status, and Achievement in Mathematics: A Multi-level Analysis. Br J Educ Psychol 91(1):101–126