Abstract

While there is a growing body of studies on written corrective feedback (WCF) in current literature, little is known about how L2 learners attend to synchronous WCF (SWCF), an innovation of providing WCF, and what factors influence their engagement. To fill the gaps, our study examined L2 learners’ affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement with such a practice, and the factors contributing to their engagement in the Chinese EFL contexts. Drawing upon a mixed-methods approach, our study comprised two phases (survey study and in-depth study) and collected data from multiple sources including questionnaires, students’ revised drafts of writing, teacher SWCF, semi-structured interviews, and writing journals. The results from survey study and in-depth study showed that Chinese EFL learners generally displayed positive engagement with SWCF in affective, behavioral, and cognitive dimensions, and their engagement was influenced by factors related to students significantly. Specifically, factors including students’ English proficiency, enjoyment of English learning, digital literacy, beliefs about SWCF, and teacher-student relationships were found to mediate whether students could make full use of SWCF and reap benefits from it. The findings of our study contribute to a fine-grained understanding of how learners attended to SWCF from the three perspectives and generate useful implications for promoting their engagement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In L2 writing contexts, written corrective feedback (WCF), referring to feedback on linguistic errors, is a pivotal pedagogical practice and procedure, which benefits L2 learners’ writing processes and written products (Cheng et al., 2025; Crosthwaite, 2017). To maximize WCF efficacy, the extant studies have investigated WCF strategies (i.e., direct and indirect WCF) and WCF scope (i.e., focused and comprehensive WCF) (Bitchener and Knoch, 2010). These studies focus on WCF per se, concerning how it should be offered. However, the effectiveness of feedback is not only associated with offering feedback, but also depends on student engagement (Hiver et al., 2021; Zhang and Hyland, 2023).

Given the importance of student engagement, recent decade has witnessed the proliferation of studies on how L2 learners engage with WCF (Shen and Chong, 2023; Wang and Xu, 2024). Of these studies, WCF tended to be provided after students had completed their writing (i.e., asynchronous WCF, AWCF) (e.g., Zheng and Yu, 2018; Zheng et al., 2023). AWCF is a common pedagogical practice in authentic L2 writing classrooms (Bitchener and Ferris, 2012; Li and Li, 2018). Currently, due to the burgeoning development of educational technology and large language models, online writing platforms and instant editing software programs (e.g., Google Docs and Skydrive) are readily accessible, which empowers teachers to offer WCF while students are working on their tasks (i.e., synchronous WCF, SWCF). With the rise of technology-enhanced education, SWCF has been established as an innovative approach to providing WCF (Cheng and Zhang, 2024a; Chong, 2019; Kim et al., 2020). However, compared with AWCF, SWCF has received relatively little attention in scholarship (Bitchener and Storch, 2016; Cho et al., 2022). To our knowledge, few studies have been conducted to comprehensively examine L2 learners’ engagement with SWCF from affective, behavioral, and cognitive perspectives. Furthermore, the existing studies on learner engagement with written feedback tended to adopt qualitative approaches with limited participants (Mao et al., 2024; Wang and Xu, 2024), which hampered the generalization of the findings. Accordingly, studies with mixed-methods approach in this area are highly recommended.

To fill the gaps, our study employed a mixed-methods design to investigate Chinese EFL learners’ engagement with SWCF in terms of affect, behavior, and cognition, and the factors influencing their engagement. By doing so, we can identify a general pattern of L2 learners’ engagement with SWCF, capture the characteristics of individual learners’ engagement, and present how different factors influenced L2 learners’ engagement process, which enables us to acquire nuanced insights into students’ engagement with this type of feedback. As such, it is believed that our study can contribute to the current literature in this line and provide a refined understanding of L2 learners’ engagement with this type of feedback.

Literature review

Asynchronous and synchronous written feedback

In terms of feedback timing, there are two modes of feedback: Asynchronous feedback and synchronous feedback. Generally speaking, written feedback is administered after students’ tasks, namely asynchronous feedback. However, the proliferation of new technological tools in AI age innovates the approaches to providing feedback. That is, written feedback can be offered in the process of students completing their writing tasks (i.e., synchronous feedback) (Ebadi and Rahimi, 2017; Ho, 2015).

The two modes of feedback are underpinned by different theories. As delayed feedback, asynchronous feedback is grounded in Guidance Hypothesis. Informed by this theoretical perspective, feedback should be delayed since immediate feedback may make learners rely on feedback excessively to correct their errors, impairing their abilities to detect and correct their errors independently (Loncar et al., 2023). With regard to synchronous feedback, it is supported by Skill Acquisition Theory, which argues that learners transform declarative knowledge into procedural knowledge through practice (DeKeyser, 2007). As synchronous feedback is offered as soon as students make errors, it prevents them from proceduralizing errors in following tasks as practice, which helps them avoid error fossilization. Also, synchronous feedback is underpinned by Interaction Hypothesis (Long, 2007), which emphasizes the importance of interaction in learning development. As he argued, immediate feedback (e.g., recasts) helps learners achieve form-function mapping, because this feedback is provided in the process of communicative tasks. In this sense, such feedback is contextualized, enabling students to receive “information on target linguistic structure in context” (Long, 2007, p. 77). Context refers to real-time events (Shintani, 2016). In our study, context means that students receive WCF in the process of writing. While Long’s discussion from the interactionist perspective focuses on corrective feedback (CF) in spoken discourse, it is also applied to SWCF in the context of writing (Shintani, 2016; Shintani and Aubrey, 2016). SWCF is similar to oral CF, given that both of them are generated during students working on their tasks (Cheng and Zhang, 2024a; Shintani and Aubrey, 2016). Based on the above discussion, it is clear that there are controversies regarding the ideal time to provide feedback.

The two types of feedback have their own merits and drawbacks. Within AWCF, learners can deal with the feedback at their own pace and do not attend to other components in writing process such as planning and translating (Shintani, 2016), which requires relatively little cognitive effort. Despite this, it is decontextualized feedback, where students have few opportunities to interact and communicate with their teachers (Shang, 2017; Shintani and Aubrey, 2016).

Compared with AWCF, SWCF enjoys the synchronous nature, which generates several unique advantages. First, receiving feedback during writing process enables learners to notice their errors immediately, understanding the gap between what they can produce and what should be produced. Specifically, SWCF provides learners with both negative (indication of errors they make) and positive evidence (correct forms) (Shintani, 2016), with which learners can make a cognitive comparison between their errors and the correct forms of linguistic structures instantly. This facilitates learners’ noticing, uptake, and internalization of SWCF, which contributes to their learning development (Cheng and Zhang, 2024a; Sauro, 2009). In addition, SWCF improves students’ use of feedback to complete writing tasks (Shintani, 2016). Within SWCF, students have opportunities to take advantage of the feedback to compose new sentences in the same task. That is, while students are writing the sentences in the same task, they can refer to the previously provided feedback, which improves the accuracy. Different from AWCF, SWCF enables learners to experience the three stages of acquisition recursively: Internalization, modification, and consolidation. Thus, in the context of SWCF, learners internalize the knowledge derived from the previously received feedback and modify the errors. Subsequently, they consult the feedback to produce new sentences, which assists consolidating what they have learnt. Having experienced the three phases, students may be able to produce correct sentences without the feedback finally. This means that they shift from other-regulation to self-regulation (Bitchener and Storch, 2016). Third, SWCF is contextualized feedback, in which students have opportunities to interact with their teachers and teachers can monitor their students’ writing process. Thus, students may be more attentive to the feedback in this context than in AWCF condition. As some previous studies (e.g., Cheng et al., 2024; Cho et al., 2022; Shintani, 2016) claimed, students may not engage with the feedback that is provided afterwards. In this sense, providing feedback on site benefits students’ engagement, which contributes to the efficacy of the feedback.

Despite the benefits of SWCF, researchers and teachers also voice their concern about this practice. Considering that teachers offer feedback along with the production of texts, students need to deal with receiving feedback, correcting their errors, and composing sentences. In this condition, students may feel cognitively demanding, thereby their working memory overloaded (Shintani and Aubrey, 2016).

To date, SWCF remains under-investigated compared with AWCF. While studies have reported the beneficial effects of SWCF on error correction and learning (e.g., Cheng and Zhang, 2024a; Shintani and Aubrey, 2016), much to be known about how L2 learners engage with SWCF affectively, behaviorally, and cognitively, as well as what factors influence their engagement.

L2 learners’ engagement with teacher WCF

Originating from educational psychology, engagement is an essential construct to measure the degree of effort students spare in their learning (Handley et al., 2011). Specifically, engagement is an inclusive term, encompassing the extent to which students exercise willingness to utilize their competence and skills to make progress in learning (Zhang and Hyland, 2018). The widely-used framework in examining student engagement was proposed by Fredricks et al. (2004). In a review article, they theorized student engagement from three perspectives: Behavioral, emotional, and cognitive. This tripartite model offers a promising and powerful lens to understand student engagement with learning.

In terms of feedback, following Fredricks et al.’s (2004) framework, Ellis (2010) conceptualized engagement as L2 learners’ responses to oral and written corrective feedback (CF). In his conceptualization, engagement comprised three sub-constructs: Affective, students’ attitudes towards CF they received; behavioral, students’ uptake of CF in revisions; cognitive, how students attend to CF cognitively. On the basis of Ellis’ (2010) conceptualization, scholars have fine-tuned and strengthened the sub-dimensions of student engagement with feedback (e.g., Cheng and Liu, 2022; Cheng and Zhang, 2024b; Fan and Xu, 2020; Han and Hyland, 2015; Zheng and Yu, 2018).

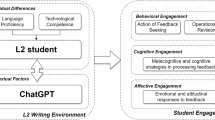

Underpinned by the previous studies, our study viewed student engagement as a meta-construct with three interlocking components:

-

Affective engagement includes students’ attitudinal responses and emotional reactions to SWCF;

-

Behavioral engagement comprises students’ revision operations and revision strategies used to improve accuracy;

-

Cognitive engagement encompasses the depth of students processing SWCF (noticing or understanding), and cognitive/metacognitive operations to address SWCF and promote revisions and writing.

To date, studies on L2 learners’ engagement with teacher WCF have proliferated (e.g., Cheng and Liu, 2022; Han, 2017, 2019; Han and Hyland, 2015; Zheng and Yu, 2018; Zheng et al., 2023). For instance, using a multiple-case design, Han and Hyland (2015) examined how four intermediate EFL learners engaged with WCF in the Chinese context. Their study revealed that there were obvious variations with regard to the four participants’ affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement with WCF, and the variability was ascribed to factors including their beliefs about WCF, their learning goals, and pedagogical contexts. Zheng and Yu (2018) probed into Chinese low-proficiency EFL learners’ engagement with teacher WCF, finding that they generally showed superficial engagement affectively, behaviorally, and cognitively. More recently, Zheng et al. (2023) furthered this issue, focusing on how individual differences mediated low-proficiency learners’ engagement with WCF. In their study, while the two participating students shared a similar level of English proficiency, they engaged with WCF differently: One engaged with WCF intensively, the other at a superficial level. The differences in engagement were attributed to both individual and contextual factors.

In comparison, there are fewer studies on L2 learners’ engagement with SWCF in existing literature. Among these extant studies, many have explored learners’ perceptions about this kind of WCF (i.e., affective engagement) (e.g., Cheng and Zhang, 2024a; Kim et al., 2020; Shang, 2017). For example, Cheng and Zhang (2024a) examined L2 learners’ perceptions and attitudes towards SWCF in the Chinese EFL contexts. The study found that Chinese EFL learners spoke highly of SWCF and identified the merits specific to SWCF. Similar findings were observed in Kim et al. (2020), where there were no differences in terms of L2 learners’ perceptions about direct and indirect SWCF. Specifically, the participants showed positive attitudes towards the two types of SWCF.

Aside from affective engagement, a few studies have investigated L2 learners’ processing and uptake of SWCF (i.e., behavioral engagement) (e.g., Cho et al., 2022; Ene and Upton, 2018; Shintani, 2016). For example, Cho et al. (2022) examined L2 learners’ responses to SWCF on Korean honorifics in collaborative writing and individual writing conditions. Through the analysis of writing samples and think-alouds, the study reported that while collaborative writing enabled L2 learners to address linguistic errors more successfully than individual writing, the two groups exhibited similar patterns in uptake of SWCF.

In summary, while the above studies have added to our understanding of L2 learners’ engagement with teacher WCF regardless of AWCF and SWCF, there are several research gaps to be addressed. First, the current studies on student engagement with SWCF did not paint a comprehensive picture. Few studies have been conducted to examine engagement from the three perspectives. Considering that the three dimensions are interactive and intertwined (Ellis, 2010; Fredricks et al., 2004), examining L2 learners’ engagement from affective, behavioral, and cognitive perspectives is warranted in order to have a deep insight. Additionally, the existing studies in this area did not explore the factors that influence student engagement with SWCF. Consequently, little is known about the mediating factors. Finally, the majority of extant studies on student engagement with written feedback were qualitative in nature (Mao and Lee, 2024; Mao et al., 2024). While the qualitative inquiries afford in-depth and thick characterizations of individual learners’ engagement, we failed to gain a general and holistic understanding about this issue. Accordingly, a mixed-methods approach with a broader range of participants is needed.

To narrow the gaps, the present study employed a mixed-methods design to answer the following research questions:

-

RQ1: How do Chinese tertiary EFL learners engage with SWCF affectively, behaviorally, and cognitively?

-

RQ2: What are the factors influencing their engagement with SWCF?

The study

Participants and contexts

In Phase One of our study, it was a survey study and we recruited the participants from six universities with different tiers in central China drawing upon the authors’ personal network. Using a convenience sampling technique, 202 participants were recruited on a voluntary basis. Their demographic backgrounds are presented in Table 1.

All the respondents attended English course at the time of data collection, which aimed to enhance their foreign language ability, critical thinking skills, and intercultural competence. In this AI age, English instruction at the tertiary level in China is empowered by technology. Specifically, EFL teachers are encouraged to integrate technologies in their curriculum and employ a variety of information technologies to support their courses. With the help of these technologies, teachers have opportunities to communicate with their students instantly, so they could collect immediate feedback and comments from their students. Doing so enables EFL teachers to acquire more knowledge about how well their students have learnt, and then adjust their teaching contents and activities correspondingly, which can improve their teaching effectiveness.

To deepen the understanding of student engagement with SWCF and the influencing factors, we conducted an in-depth study in Phase Two. Of the 202 respondents, 17 students expressed their interests in participating in follow-up study and contacted us. To be representative, we employed the maximal variation sampling strategy to recruit the focal participants, which helps us include the participants with diverse backgrounds and understand the phenomenon under investigation (Creswell, 2014). In the actual selection, we bear the principle in mind that the diversity of the focal participants’ backgrounds should be maximized. Accordingly, we took the following criteria into account: (1) both male and female participants should be included; (2) a range of study phases should be represented; (3) different levels of universities should be represented; (4) students with hard and soft disciplines should be included; (5) during data collection, they needed to receive teacher SWCF. Finally, 10 students were selected as the focal participants in Phase Two (see Table 2).

Data collection

To allow data triangulation, our study collected data from various sources: Questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, students’ revised writing samples, teacher SWCF, and writing journals.

In Phase One, we administered questionnaires to explore how Chinese tertiary EFL learners engaged with SWCF and the factors influencing their engagement in general. Informed by the previous studies (e.g., Mao and Lee, 2024; Wang and Xu, 2024; Zheng et al., 2023), we developed learner engagement with the teacher SWCF questionnaire (LETSWCFQ) and factors influencing engagement questionnaire (FIEQ) (see Appendix A). As for the former one, we conducted exploratory factor analysis through SPSS 26. The analysis revealed that the questionnaire comprised three factors with 15 items, namely affective, behavioral, and cognitive (KMO = 0.854, p < 0.001). Moreover, the internal reliability of the questionnaire was examined: Affective (Cronbach’s α = 0.88), behavioral (Cronbach’s α = 0.85), cognitive (Cronbach’s α = 0.83). All were above the threshold value 0.7, indicating that each dimension had good internal consistency (DeVellis, 2012). The questionnaires were based on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 “strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”.

Regarding FIEQ, we also implemented exploratory factor analysis, finding that the questionnaire was a three-construct model with 9 items (KMO = 0.832, p < 0.001). The three constructs were labeled as student, teacher, and context. Furthermore, Cronbach’s α of the three constructs reached 0.87, 0.83, and 0.79. FIEQ was self-reported with 5-point Likert scale (1=not at all influential to 5=very influential).

In Phase Two, we conducted an in-depth study to explore how L2 learners engaged with SWCF actually. In our study, the 10 focal participants were informed that they needed to undertake their revisions based on SWCF while completing their writing tasks, but they were allowed to revise their errors at any time during task performance. The students wrote down their revisions adjacent to the errors. The students completed their writing on WPS (Word Processing System), which is a free and web-based collaborative writing program in mainland China. WPS enables users to edit documents synchronously and can be accessed through individual account. During feedback provision, the focal participants’ teachers moved between and browsed their writing samples. Once identifying their errors, they provided WCF via the comment box of WPS immediately. After the writing tasks, the participants uploaded and cloud stored their revised drafts with SWCF. Subsequently, we collected the samples completed by the participants.

Shortly after SWCF, we interviewed each focal participant in a semi-structured format to explore how he/she engaged with SWCF affectively, behaviorally, and cognitively, as well as what factors mediated their engagement. To collect more information, each interview was conducted in Chinese (the participants’ L1) and lasted from 30–45 min. In each interview, open-ended and probing questions were asked to make students elaborate and reflect on the issues relevant to engagement with SWCF and influencing factors. With the students’ permission, the interviews were audio-recorded for further analysis.

As an important retrospective instrument, journals are widely used to understand participants’ perceptions in qualitative studies (Dörnyei, 2007). Given that the time for semi-structure interviews was limited, we might miss some important information. Accordingly, we asked the participants after the writing tasks to keep journals to record their attitudes towards SWCF, the strategies they used to address the feedback, the cognitive/metacognitive operations they deployed to deal with SWCF and improve their writing, and the factors influencing their engagement with feedback. The writing journals were prompt-driven and drafted by the participants in Chinese.

Data analysis

Analyzing questionnaires

For the quantitative data from questionnaires, we first screened them and cleaned missing values and outliers. Next, we examined whether the data were normally distributed. In our study, the data met the criteria of normal distribution if the standardized values of skewness and kurtosis fell within |3.0| and |8.0 | , respectively. After examination, the questionnaire data were normal distribution, so we employed independent samples t-tests and one-way ANOVAs to investigate whether the participants’ demographic backgrounds influenced their engagement significantly. Furthermore, we used multiple regression analysis to explore to what extent the factors influenced Chinese EFL learners’ engagement with SWCF.

Analyzing students’ writing samples and teacher SWCF

To contextualize students’ engagement with SWCF, the first author analyzed teachers’ SWCF practices. First, he examined the SWCF that each focal participant received from the perspective of scope. Based on the previous studies (Liu and Brown, 2015), WCF scope was precisely classified into three types: Highly focused (on only one error type), mid-focused (2–5 types), and comprehensive (most or all error types). In addition, he coded the SWCF according to feedback strategy. Informed by the previous studies (e.g., Bitchener and Ferris, 2012; Cheng et al., 2025), the feedback was grouped into direct SWCF (i.e., teachers providing errors with direct corrections) and indirect SWCF (i.e., the indication of errors without corrections).

To understand students’ behavioral engagement, the first author scrutinized their revision operations. Specifically, he first compared the focal participants’ revisions with their teachers’ SWCF, by which the changes that the participants made could be determined. Then, referring to Cheng and Liu (2022) and Zhang and Hyland (2018), he classified revision operations into correct revision, incorrect revision, substitution, deletion, and no revision.

To ensure the reliability, a PhD candidate in applied linguistics was invited to be a co-coder. Roughly 20% of students’ textual data were selected randomly and coded separately by the PhD student and the first author. The inter-coder agreement for feedback scope, feedback strategy, and revision operations reached 95.67%, 94.86%, and 93.77%, respectively. We discussed the disagreements until they were resolved.

Analyzing semi-structured interviews and writing journals

The first author transcribed the recordings of semi-structured interviews verbatim, after which he sent the transcripts to the participants to check accuracy. The analysis was completed manually. To profile students’ engagement in the three dimensions, our study employed a thematic analysis for the qualitative data from semi-structured interviews and writing journals. As an important approach to data analysis in qualitative study, thematic analysis is useful in terms of searching for patterns within data and condensing rich and detailed information to an analyzable and presentable form (Braun and Clarke, 2006). To explore their actual engagement, the first author employed a deductive coding approach of thematic analysis. According to the conceptual framework of student engagement with SWCF, several codes were identified and pre-determined: (1) students’ attitudes towards SWCF; (2) students’ emotional reactions to SWCF; (3) revision strategies; (4) the awareness of SWCF (noticing or understanding of it); (5) cognitive/metacognitive operations that students deployed to address SWCF and refine their writing. Of the five codes, the first two indicated students’ affective engagement, the third one behavioral engagement, and the last two cognitive engagement. In practical coding process, he carefully examined the transcripts and writing journals and coded them along with the five codes. For example, in the interview, one participant expressed that SWCF was helpful. It was coded as students’ attitudinal response to SWCF and then was assigned to the theme “affective engagement”. Also, he was open to new themes that might appear in the coding process in order to avoid missing some important themes.

To explore the factors influencing their engagement, the data from interviews and journals were analyzed inductively with a recursive and iterative process. The first author adhered to data reduction, data verification, and conclusion drawing (Miles and Huberman, 1994). Through data reduction, he mainly focused on the factors influencing students’ engagement. After careful within-case coding, several salient and recurrent themes emerged such as language proficiency, the enjoyment in learning English, and their beliefs regarding SWCF. Next, these themes were compared and refined across cases.

To enhance the trustworthiness of coding, approximately 20% of qualitative data were selected and coded independently by the PhD candidate and first author. The inter-coder reliability for affective engagement, behavioral engagement, cognitive engagement, and influencing factors was 95.31%, 96.24%, 89.57%, and 90.82%, respectively. We discussed and addressed any discrepancies in coding.

Findings

RQ1: How do Chinese tertiary EFL learners engage with SWCF affectively, behaviorally, and cognitively?

Results from survey study

The results from questionnaires established a general picture regarding L2 learners’ engagement with teacher SWCF and the mediating factors. The descriptive data revealed that the mean ratings of affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement were 4.65, 4.37, and 4.18, all exceeding 4.0. This suggested that Chinese EFL learners generally displayed positive engagement with SWCF in the three dimensions.

To deepen our understanding of student engagement, we further investigated whether there were significant differences in students’ engagement in terms of their demographic backgrounds. Specifically, we used independent samples t-tests to compare students’ affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement with regard to their gender and disciplines. According to Table 3, learners’ affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement did not differ significantly across their gender. This also held true for disciplines. Thus, the two variables did not influence students’ engagement.

Moreover, we conducted one-way ANOVAs to see whether students in different study phases and university levels displayed significantly different engagement from the three perspectives (see Table 4). As for study phases, no significant differences were found in terms of affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement across Year 1–4. As regards university levels, this variable did not affect students’ affective and behavioral engagement noticeably, but influenced cognitive engagement significantly (p = 0.003). Tukey post hoc tests were used to check the between-group differences and found that 985 and 211 university students exhibited more profound cognitive engagement with SWCF than those in other universities (985: p = 0.017; 211: p = 0.021), but there was no significant difference between 985 and 211 university students in terms of their cognitive engagement.

Findings from in-depth study

To contextualize the focal students’ engagement with SWCF, we investigated the SWCF that they received from feedback scope and feedback strategy.

As Table 5 shows, the SWCF that the focal participants received was provided in a mid-focused approach. That is, the teacher did not correct a wide array of errors on their students’ writing. In terms of feedback strategy, three participants received SWCF indirectly, while the rest received the feedback in a mixed approach, integrating both direct and indirect SWCF.

Affectively, eight out of ten students were positively oriented towards SWCF, speaking highly of this practice. Their positive attitude can be reflected by the words such as “effective”, “helpful”, and “valuable”. Furthermore, they explained the reasons for their attitudes by elaborating on the merits of SWCF. S6’s explanation seemed to sum up the majority of participants’ opinions:

The feedback highlighted my errors in writing, so I would pay attention to them and avoid making such errors in subsequent writing tasks (S6, interview).

According to the excerpt, S6 referred to a general advantage of WCF, irrespective of feedback timing. More importantly, the participants further pointed out two advantages specific to SWCF. One was helping them recognize and correct the errors in writing instantly, since the feedback was offered during composition stage, which could dispel their uncertainty about how to use the target linguistic structures correctly (e.g., S5, S7, S10).

In addition, SWCF provided students with the online supervision by teachers, which prompted them to engage with feedback more effortfully.

Compared with traditional feedback that was provided after writing process, SWCF enabled me to take the teacher’s feedback more seriously given that the writing process was supervised by the teacher. This contributed to deep engagement with the feedback (S2, journal).

Similarly, as S1 responded in the interview, the traditional feedback, as delayed feedback, was provided asynchronously, so she was not monitored by teachers and tended to leave the feedback unattended. According to the responses, this advantage of SWCF was associated with the nature of immediacy, which enables teachers to monitor their students’ writing and revision processes while providing feedback.

Despite their positive attitudes towards SWCF, they also reflected on its constraints critically due to the immediacy of SWCF. S10’s responses were very typical. As he noted in the journal, it was challenging and demanding for students particularly low-proficiency learners to receive feedback and compose texts at the same time, where they had to spare much effort. In addition, S5 made reference to the other constraint:

SWCF was provided during the writing process, which may distract students’ attention and make them find it difficult to focus on their writing tasks (S5, interview).

Interestingly, two students (S3 and S8) responded to SWCF negatively, attributing to their unfavorable attitudes to the synchronous nature of SWCF. As they remarked in the journals, SWCF was provided immediately, which made it difficult for them to fix attention on completing their writing tasks. The negative attitude was also evident in the interview:

I felt much burdened in the situation, where receiving feedback and composing texts occurred simultaneously. I was not good at handling two things at the same time (S8, interview).

When it comes to emotional reactions, the majority of students felt positive to receive teacher SWCF, as they expressed that SWCF provided them with opportunities to recognize and correct errors immediately in the process of writing. In comparison, three students had more complex emotional reactions. That is, they experienced mood swings. For example, as S2 noted, he initially felt disappointed and embarrassed due to his recurring errors in articles and sentence structures. However, he was able to regulate his negative feelings, as he concentrated on addressing feedback and completing the writing task, “since the teacher provided feedback on site, I had to attend to writing and feedback simultaneously. In this situation, the bad moods disappeared”. Finally, he acknowledged the importance of feedback, saying “the more SWCF I received, the greater progress I made”. The emotional trajectory demonstrates that S2 converted his negative emotions to positive ones and he appeared to perceive and realize the affordances provided by SWCF.

Regarding behavioral engagement, our study examined it from the perspective of revision operations and revision strategies. In terms of revision operations, they deployed a variety of revision operations. As Table 6 presents, 74.70% of SWCF points were addressed correctly, 12.05% incorrectly, 2.41% by substitution, 3.61% by deletion, and 7.23% with no revision. This suggested that the focal participants considered 92.77% of SWCF in some way or another, indicating that they engaged with SWCF extensively in behavior.

With regard to revision strategy, the students (e.g., S1, S6, S7, S9) consulted their teachers online to dismiss confusions and improve their revisions. For example, S1 mentioned that she turned to her teacher online to resolve a piece of indirect SWCF on sentence structure (see Example 1). In the interview, she shared the revision experience:

My teacher underlined this part, which suggested that it contained an error. However, I did not know what was wrong with it, so I asked her for help through the comment box. The teacher responded immediately and made explanations for me (S1, interview).

Example 1:

While making a friend online, safety is the most important thing…

Also, S6 elaborated on the similar experience. When facing the SWCF he did not understand, he took advantage of the comment box to communicate with his teacher. With the help of the synchronous technology, his teacher was empowered to address S6’s confusions and uncertainties immediately, which facilitated his correction of errors and improved his writing accuracy.

As online feedback, SWCF requires teachers and students to be online simultaneously, which makes it possible for the instant interaction between teachers and students. The above two excerpts indicated that the two students had good sense of digital literacy, which enabled them to take advantage of the synchronous nature to address SWCF and refine their writing.

From cognitive perspective, the focal participants in general had assiduous cognitive engagement, which was investigated from the depth of processing SWCF and the cognitive/metacognitive operations they deployed. Regarding the former, the participants stated that they did not have much difficulty noticing SWCF, since the teacher highlighted the errors explicitly with/without corrections. In this sense, they could recognize the corrective intention of SWCF easily.

Furthermore, the students responded that it was not demanding for them to understand nearly all the feedback points. Despite this, they felt it was somewhat challenging to understand SWCF on sentence structure and word choice, especially the indirect SWCF points.

As for the deployment of cognitive/metacognitive operations, the analysis of data showed that they used several strategies to regulate their mental processes. To begin with, the participants conducted ongoing evaluations and analyses of SWCF to check whether the feedback was appropriate. As S7 explained in the journal, it was very demanding for the teacher to provide immediate feedback, which might make some of the feedback inappropriate. S2 also used this strategy due to the similar concern:

In SWCF, the teacher suffered from heavy time pressure. He had to monitor several writing samples at one time. So I thought that he might provide some unsuitable feedback., and I needed to examine whether the feedback was in accordance with my intentions (S2, journal).

According to their responses, the students seemed to exert their agency to assess and reflect on their teachers’ feedback rather than uptake it blindly, suggesting that they were not passive receivers of feedback.

Another operation to regulate mental effort was planning. The focal participants reported that since the feedback had been offered during composition stage, they had to plan their writing and revision processes. S1, for example, commented on this in the interview:

Although feedback was provided in the middle of completing writing task, I did not interrupt the writing process to deal with feedback. Alternatively, I responded to the feedback after I had completed the sentences that I was writing (S1, interview).

In a similar vein, S6 expressed that while the feedback was implemented synchronously, he was not interrupted by the feedback. Specifically, he did not stop the sentences at hand to process feedback and make corresponding corrections. In this sense, while the feedback was provided on site, the students kept their own pace of writing and revision. As such, they seemed to be strategic learners, and did not follow their teachers’ feedback technically.

Students’ cognitive engagement was also manifested in their use of previous SWCF to assist writing and revision in the same writing task. Specifically, the students stated that they made reference to the previous SWCF points to compose new sentences. For example, S5 elaborated on this:

I had access to SWCF at any time during writing process, so I went back to some of them when using the same grammatical points to write new sentences in this task, which helped me avoid similar errors (S5, journal).

Another three students also employed the already provided feedback but in a different approach. They used the feedback to identify errors and make self-corrections in the process of writing. S10 served as an example. In the interview, he responded, “I received SWCF on articles, and had employed the feedback to identify and correct another three similar errors autonomously before the teacher indicated them”. Likewise, S6 demonstrated the same operation in the journal, saying that with the previous SWCF on prepositions, he detected and corrected the similar errors by himself while completing the writing task.

Finally, the participants mobilized the knowledge they immediately acquired from SWCF to address feedback and enhance revisions. This strategy was mentioned by S7 in the journal, emphasizing that with the teacher’s explanations of feedback online, he had a deeper insight into the nature of errors, by which he could correct the following similar errors successfully. The comments from S2 can also illustrate this:

I made two same errors in sentence structure, and the teacher indicated them. With her immediate help for one error, I realized why they were erroneous and understood the rule underlying the feedback. So, I corrected both of them successfully (S2, interview).

In the above explanations, SWCF helped the participants enlarge their grammatical repertoire while composing their writing, by which they were empowered to process the feedback points on the same error types.

In contrast, several students (e.g., S3, S4, S8, S9) did not exercise much cognitive/metacognitive effort to address SWCF. It seemed that they did not use the context (i.e., the paragraphs or the whole text) to determine whether the feedback was appropriate. Additionally, they incorporated the SWCF uncritically in revisions. That is, they copied all the direct SWCF points without fully understanding them. Interestingly, although S3 and S8 held a negative attitude towards SWCF, they incorporated direct SWCF without reservation.

The SWCF was provided by teacher, whose English proficiency was much higher than ours, so his feedback must be right (S3, interview).

Contrastingly, they treated the majority of indirect SWCF points passively. Specifically, they tended to leave them aside.

I did not know how to deal with many indirect SWCF points because of my English proficiency. Furthermore, as the feedback was offered in the process of writing, I felt challenged to interpret and process indirect SWCF while writing (S8, journal).

What are the factors influencing their engagement with SWCF?

Results from survey study

To have a general understanding of the factors mediating students’ engagement, our study administered FIEQ, which comprised 9 items related to student, teacher, and context. The descriptive statistics showed that the mean of the factors relevant to student ranked the first (M = 4.63), which was followed by factors in relation to context (M = 3.51) and teacher (M = 3.24), respectively.

Furthermore, we implemented multiple regression analysis to investigate the extent the factors contributed to their engagement. As Table 7 shows, among the three factors, student was a significant predictor. However, the other two were non-significant factors. Judging from the standardized regression coefficients, we could see that factors related to students had the largest effect on L2 learners’ engagement with teacher SWCF (β = 0.623), followed by context (β = 0.231) and teacher (β = 0.142).

Findings from in-depth study

The follow-up in-depth study provided detailed accounts of how the factors influenced students’ engagement with SWCF actually, affording us a fine-grained understanding of these factors.

English proficiency was identified as an important learner factor. In our study, according to the English scores in College Entrance Examination, College English Test, and the discussion with their teachers, we found that the majority of highly-engaged learners (e.g., S1, S6, S7, S10) generally had relatively high level of English proficiency, while their superficially-engaged peers (e.g., S3, S8) were low-proficiency learners. The different levels of English proficiency led to the variation in their affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement. The high English proficiency enabled the participants to be aware of the affordances of SWCF, address indirect SWCF correctly, and deploy extensive cognitive/metacognitive operations skillfully, which contributed to their deep engagement. In contrast, S3 and S8’s limited English proficiency constrained their involvement, making them feel challenged to receive SWCF, preventing them from making effective revisions and adopting various cognitive/metacognitive strategies to address SWCF.

Another major factor was their enjoyment of English learning. According to the qualitative data, the deeply-engaged learners (e.g., S2, S5, S9, S10) showed a high level of English enjoyment, which motivated them to learn English passionately and inspired them to engage with SWCF substantially.

I was fond of learning English. During the past years, I acquired much knowledge about this language, and made great progress in English. I have won many prizes in different English-related competitions, which prompted me to spare much effort to learn English (S2, journal).

The above excerpt showed that S2’s enjoyment of English learning came from his pride in accomplishment in learning English. Additionally, their enjoyment was in relation to peer support.

My peers were very nice and warm-hearted. They were willing to offer help when I had some troubles in English learning. They were always there when I needed them (S5, interview).

However, the superficially-engaged learners (e.g., S3 and S8) did not enjoy learning English. As complained in the interview, S3 was not interested in learning English. Also, he added that it was very boring to have English classes, and such classes were not conducive to his learning.

Some teachers just read the slides or textbooks during the whole class. Some teachers asked the students to make presentations but did not give any comments on students’ presentations. These practices had little value for our learning, which wasted my time (S3, journal).

According to the excerpt, it was apparent that S3 did not feel enjoyment in learning English. In this situation, it was not surprising that he disengaged with the activities in English class. As such, he displayed engagement with SWCF at the surface level.

Furthermore, students’ engagement was mediated by digital literacy. As an innovative approach to providing WCF in technology-enhanced contexts, SWCF involves synchronous technology. Thus, to address this type of WCF requires digital literacy. According to the data from semi-structured interviews and writing journals, several students (e.g., S2, S6, S10) recognized the advantages and disadvantages of SWCF, and took advantage of synchronous nature to have instant communication with teachers to address the feedback. In this sense, these students were very familiar and felt at ease with the synchronous technology, which indicated that they possessed good digital literacy. In contrast, some students (e.g., S3, S8) appeared to have a weaker sense of digital literacy. As a consequence, they were not used to receiving SWCF, which they felt very demanding and taxing. Additionally, they received SWCF passively, utilizing few cognitive/metacognitive strategies to address the feedback in synchronous settings.

In addition, students’ beliefs about SWCF were found to influence the participants’ engagement. According to the interviews and journals, some participants identified the general and specific merits of SWCF, appreciating and commending this practice. This suggested that they believed in the usefulness of SWCF and acknowledged its important role. In contrast, S3 and S8 were not in favor of such WCF, and pointed out that this type of feedback distracted their attention in writing process and made them feel challenged and burdened. The different beliefs elicited the differences in engagement. The firm belief in SWCF played a facilitative role in students’ engagement, which incentivized them to address the feedback provided, thus having profound engagement in different dimensions. A different picture was painted by the superficially-engaged learners. Due to their disbelief in SWCF, they did not find its worth, which discouraged them from exercising their agency to attend to SWCF. Thus, their affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement was reduced.

The teacher-student relationships worked. Participants such as S1, S5, S6 and S10 trusted their writing teachers, which was evidenced that they expressed gratitude to their teachers, since their instruction helped them enhance their writing performance. As S1 expressed in the interview:

I appreciated my teacher’s instruction, since it enabled me to improve my writing proficiency (S1, interview).

However, this was not true for the superficially-engaged students (e.g., S3, S4, S8). They did not establish a positive relationship with their writing teachers.

The teacher tended to evaluate a student mainly through his/her learning performance, which I thought was unreasonable and unfair. Her teaching was also performance-oriented. In the writing course, she gave us templates and then required us to practice many times with the purpose to help us achieve high scores in writing in examinations. I did not think she really understood the nature of writing (S4, interview).

The teacher mainly focused on how to produce error-free sentences. However, I believed that a piece of good writing went beyond accurate sentences, and it also contained other components such as well-developed ideas and reasonable structure (S3, journal).

From the above extracts, S3 and S4 showed disappointment and dissatisfaction with their teachers’ evaluation criteria and teaching approach to writing. Thus, there was a tension between their perceptions about writing and their teachers’ actual teaching.

Discussion

L2 learners’ engagement with SWCF

In our study, we utilized a mixed-methods approach to examine Chinese EFL learners’ engagement with SWCF in affect, behavior, and cognition. The survey study showed that students generally had profound engagement with SWCF in the three dimensions. We further found that students’ demographic backgrounds such as gender, disciplines, and study phases did not influence their engagement significantly. However, university levels had significant influence on their cognitive engagement. The follow-up study generally agreed with the quantitative results and provided in-depth accounts for them.

Regarding affective engagement, the participants overall showed positive attitude towards teacher SWCF. This result was in line with the previous studies (e.g., Cheng and Liu, 2022; Zheng and Yu, 2018), where L2 learners expected to receive teacher WCF and valued such a practice. Furthermore, the students provided reasons for their supportive orientation. Specifically, they cited the advantages of WCF to support their attitudes, as SWCF has the benefits of general WCF (Shang, 2017). More importantly, they pinpointed the merits unique to SWCF. That is, it enabled them to correct errors instantly and to engage themselves with teacher feedback more deeply. These two advantages are associated with the immediacy of SWCF, which involves teachers’ online supervision and invites L2 learners’ deliberate attention to feedback (Ene and Upton, 2018; Kourtali, 2022; Li and Li, 2018). More interestingly, the immediate nature seemed to be a double-edged sword. The students also reflected on the constraints of SWCF resulted from this nature, identifying that receiving WCF in the process of writing may distract students’ attention and impose a heavy load on them. This constraint is very understandable, since SWCF complicates the writing process. Specifically, writing process consists of planning, translating, and revision (Hayes and Flower, 1980). In SWCF mode, feedback is provided during writing process, so learners have to attend to revision and other aspects of writing (e.g., planning and translating) at the same time. That is, approaching SWCF interferes with writing process. As Shintani and Aubrey (2016) posited, “limited working memory might interfere with simultaneous operations involved in writing” (p. 299). In this situation, much more cognitive resources are entailed than in AWCF condition, which makes L2 learners invest more cognitive effort (Cho et al., 2022; Loncar et al., 2023).

As for their emotional responses, while most participants felt positive to receive SWCF, three students experienced emotional fluctuations. Initially, they had the negative emotions such as disappointment, frustration, and embarrassment. As Truscott (1996) argued, feedback could influence L2 learners’ emotions negatively. Encouragingly, they were not restricted to those negative emotions. Instead, they were able to regulate their emotions, shifting from the initial negative moods to positive feelings. The emotional shifts suggested that these learners were skilled self-regulators who could manage their emotions. This finding is considerably inspiring, given that managing emotions is a crucial dimension of feedback literacy. Specifically, regulating emotions enables L2 learners to interpret, internalize, use feedback, and derive the knowledge conveyed by the feedback to facilitate their learning (Carless and Boud, 2018; Zhang and Mao, 2023). Their skillful regulation of emotions indicated that they seemed to perceive the affordances provided by feedback and regard feedback as an importance of source of new knowledge (Dawson et al., 2019). As such, they were not overwhelmed by the feedback and engaged with it actively to reap the benefits from feedback.

In terms of behavioral engagement, the questionnaire data suggested that our participants showed profound engagement with SWCF in behavior. This result aligned with the findings of the in-depth study. In Phase Two, the focal participants conducted extensive revision operations including correct revision, incorrect revision, substitution, deletion, and no revision. Thus, they made effective and substantial modifications to their writing, which indicated that they had effortful behavioral engagement. Furthermore, the students turned to their teachers for help online to resolve their confusions and address the difficulty. This is a novel strategy, which has not been reported in the previous studies on student engagement with traditional paper-based feedback (e.g., Han and Hyland, 2015; Zheng et al., 2023). Given that feedback occurred during task, it was not very possible for learners to seek help from other external resources such as peers, textbooks, and internet. However, in SWCF condition, instant communication with teachers can be achieved, thus tapping the online dialogue between teachers and students, in which teachers can provide students with immediate scaffolding to assist their revisions. As Ene and Upton (2018) argued, synchronous settings enable students to focus on their tasks and to receive online guidance from teachers.

The finding that our participants sought help from teachers proactively via comment boxes suggested that they leveraged the power of synchronous technology involved in SWCF and showed high sense of digital literacy. Empowered by digital literacy, they engaged with online teacher-student communication to discuss the feedback and address it. In this sense, it appeared that they viewed addressing SWCF as a social practice rather than an individual activity, in which they took advantage of learning community to enhance their writing and learning outcomes.

Cognitively, the results from Phase One and Phase Two revealed that our participants in general engaged with SWCF profoundly. In Phase One, the results of one-way ANOVA suggested that university levels influenced students’ cognitive engagement with SWCF significantly. Students in 985 and 211 universities exhibited deeper cognitive engagement than their peers in other universities. This result may be attributed to students’ English proficiency. Specifically, as tier 1 universities in China, 985 and 211 universities admit students with high scores in College Entrance Examination. Thus, students in these universities tended to have relatively high levels of English proficiency, which was considered as an important factor mediating students’ cognitive engagement with feedback (Cheng and Liu, 2022; Zheng and Yu, 2018).

In Phase Two, the focal students could not only notice teacher SWCF easily but also understand almost all the SWCF points. More importantly, they deployed a variety of cognitive/metacognitive operations. These findings demonstrated that they enacted actively to address SWCF and exploited the learning opportunities provided by SWCF. To be specific, they utilized four cognitive/metacognitive strategies to improve their writing. Interestingly, of the four strategies, three were SWCF-specific. First, they regulated and planned their writing and revision processes. Unlike AWCF, SWCF is administered in the process of writing, which probably interrupts students’ writing process (Shang, 2017). Encouragingly, the students in our study planned when to attend to SWCF and make corrections, attempting to control their own pace of writing and revision. This means that they were not spoon-fed but agentic learners, trying to reduce the negative influence of interruption on their writing process.

Second, they made good use of the previous SWCF points to complete their writing tasks. As Shintani (2016) argued, although SWCF is similar to oral interaction in synchronous settings, SWCF is at a slower pace, increases the visual salience, and remains on the students’ writing. These characteristics make SWCF serve as the linguistic “object” and students can access to it at any time during task (Sauro, 2009; Shintani, 2016). In this situation, they could refer to the feedback as “model” to compose new sentences or compare their output with the feedback, diagnosing and correcting errors by themselves while completing the writing task (Ebadi and Rahimi, 2017; Kourtali, 2022; Zaini and Mazdayasna, 2015). Such an operation suggested that the students made full use of the feedback, transferring the feedback to the subsequent writing and revision processes. As such, they appeared to internalize the SWCF and acquire the conceptual information conveyed by it, which helped them shift from other-regulation to self-regulation (Cho et al., 2022).

Additionally, they employed the newly developed knowledge from SWCF to resolve feedback in the same task. As noted previously, teachers’ onsite responses to students’ writing provide an instant communication between teachers and students (Ebadi and Rahimi, 2017; Zaini and Mazdayasna, 2015), in which teachers can explain the metalinguistic rules underlying the feedback for students to facilitate their understanding. Thus, SWCF has the potential to help L2 learners expand their grammatical knowledge base in the process of writing, empowering them to use the knowledge to correct similar errors. This strategy is interesting and especially relevant to SWCF, since the previous studies have found that L2 learners tended to retrieve their previous knowledge to process feedback in asynchronous environment (e.g., Cheng and Liu, 2022; Fan and Xu, 2020).

To conclude, focusing on L2 learners’ engagement with SWCF, our study yielded some new findings and provided new insights into the field, which have not been reported in the prior studies embedded in asynchronous contexts (e.g., Fan and Xu, 2020; Cheng and Zhang, 2024b; Han and Hyland, 2015; Zheng et al., 2023). For instance, students communicated with teachers instantly to remove confusions, regulated the writing and revision processes to minimize the interruption of SWCF, consulted the previous SWCF instances to complete the writing tasks, and activated the knowledge immediately acquired from SWCF to facilitate revisions. These findings are in relation with the immediacy of SWCF. With this nature, as discussed previously, SWCF has some advantages such as creating online communication between teachers and students, enabling students to experience the stages of acquisition recursively, and improving students’ noticing of feedback (Shintani, 2016). Thus, the synchronous affordance generated by SWCF has the potential for enhancing L2 learners’ engagement (Cheng et al., 2024).

Factors contributing to engagement

The results from questionnaires showed that learner factors influenced students’ engagement significantly, while factors related to teacher and context had non-significant impacts on it. The findings of in-depth study revealed that the focal participants’ engagement was mediated by various factors and explained how such factors influenced their engagement, which deepened our understanding of these influencing factors.

Phase Two showed that our focal participants’ engagement was influenced by two common factors: Students’ English proficiency and their attitudes towards teachers. It is not surprising that English proficiency mediated students’ engagement. As Ferris (2002) stated, the understanding, processing, and uptake of feedback require L2 learners’ adequate linguistic knowledge. This is particularly true in SWCF condition, where students may spare more cognitive effort to address the feedback than AWCF setting (Shang, 2017). Thus, English proficiency may play a more prominent role in students’ engagement with SWCF. Additionally, the relationships between teachers and students were found to mediate students’ engagement. In our study, students in general trusted their teachers, appreciating the helpfulness of their instructions. In contrast, a few participants did not form a trusting and positive teacher-student relationship, which was evident in their disbelief in their teachers’ criteria for assessing students and their teaching approaches. The mediation of students’ attitudes towards their teachers on students’ engagement has been discussed in the prior literature (e.g., Henry and Thorsen, 2018; Zheng et al., 2023).

Apart from the common factors, our study also found some interesting factors contributing to their engagement. First, English learning enjoyment worked in students’ engagement. As a positive emotion in second language acquisition, enjoyment is of considerable significance for foreign language learning and is regarded as a strong predictor of foreign language learners’ achievement (Boudreau et al., 2018). With enjoyment, learners can trigger their motivation in learning, mobilize their problem-solving strategies, and develop their existing knowledge base (Boudreau et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018). As such, this positive emotion encourages learners to overcome their negative emotions (e.g., anxiety and frustration) and engage with classroom practices actively (Fredrickson, 2013). This factor may be particularly important for engagement with SWCF, where students probably feel more challenged and have to invest more effort to process it.

In addition, digital literacy played a significant role. Different from AWCF in traditional paper-based context, SWCF is an innovation of feedback provision and involves technology. To engage with SWCF, L2 learners should equip with digital literacy in addition to language proficiency. That is, they need to be familiar with technology and had a competence including “computer skills, abilities in information and communications technology, information evaluation skills, as well as positive attitudes” (Zhang and Hyland, 2023, p. 2). In our study, some students had good digital literacy, feeling at ease with SWCF, realizing the affordances and constraints of SWCF, and using the synchronous characteristic to interact with teachers. This means that their engagement with SWCF was empowered by technology.

To sum up, both the quantitative and qualitative results suggested that Chinese EFL learners’ engagement with SWCF was a complicated practice, which was mediated by a synthesis of factors. In many previous studies (e.g., Cheng and Liu, 2022; Cheng and Zhang, 2024b; Zheng and Yu, 2018), students’ language proficiency tended to be considered as a decisive factor mediating students’ engagement. According to our findings, we would like to argue that it was too simplistic to ascribe L2 learners’ (dis)engagement to their language proficiency. In this AI age, we need to emphasize the significance of digital literacy in students’ engagement with technology-enhanced feedback.

Despite the positive findings about L2 learners’ engagement with SWCF, some practitioners and researchers may raise concern over the practicability of SWCF in authentic L2 classrooms. As they question, it is challenging and demanding for teachers to implement this practice in classroom pedagogy in that they need to browse their students’ writing as quickly as possible to identify errors on site. Therefore, heavy workload and time pressure are involved in teachers’ provision of SWCF (Cheng and Zhang, 2024a). However, the practicability hinges on many factors such as students’ language proficiency (writing speed), the length of writing tasks, the types of errors targeted by feedback, and class size (Cho et al., 2022; Shintani and Aubrey, 2016). To increase its feasibility in real L2 classrooms, several strategies can be adopted to address the practical constraints. First, L2 teachers need to change the traditional approach to providing feedback in AWCF condition. That is, they should forgo comprehensive feedback, focusing on all or the majority of errors. Instead, they can focus on 2–4 types of errors when providing SWCF. In addition, teachers can ask their students to complete the tasks of paragraph writing rather than whole composition, by which teachers can read smaller number of words and their pressure of offering SWCF can be alleviated correspondingly. Finally, as for large-size classrooms, teachers can implement collaborative writing in groups with 3–5 students. In doing so, they can monitor fewer writing samples at one time. These strategies are expected to reduce teachers’ workload in providing SWCF, making SWCF a feasible approach to enhancing L2 learners’ writing proficiency.

Overall, the novelty of our study lies in the research topic and design. In terms of the research topic, compared with AWCF, SWCF has garnered less scholarly attention (Cho et al. 2022; Kim et al., 2020). While there were several investigations on students’ engagement with synchronous written feedback, they mainly focused on affective engagement or behavioral engagement. Our study examined L2 learners’ engagement comprehensively from three perspectives and further explored the factors influencing engagement, which provided us a nuanced understanding of the research issue. Moreover, this study contributes to the current literature with regard to research design. Despite the growing body of studies on L2 learners’ engagement with WCF, the majority of them were qualitatively oriented and mixed-methods approach is called for (Mao and Lee, 2024; Mao et al., 2024). Following the recommendation, our study employed a mixed-methods design, where a survey study and an in-depth study were included. Such a design can allow data triangulation and achieve both generalizability and the thick-description of the research findings.

Implications, limitations, and future research

Our study brings some possible pedagogical implications. The findings of our study suggested that L2 learners engaged with SWCF substantially in the three dimensions. Accordingly, as an alternative to AWCF, SWCF should be encouraged to use in real L2 writing classrooms. While this approach is questioned for teachers’ workload and pressure, its feasibility depends on a variety of factors and our study formulated several strategies such as asking students to write paragraphs rather than whole texts and adopting collaborative writing. These strategies are believed to help teachers address the challenges of providing SWCF and improve the practicability of SWCF approach.

Second, our study found that students’ engagement was impacted by many factors such as learners’ beliefs, learning experiences, and their attitudes towards teachers. To engage students with feedback and generate better revisions, teachers should pay attention to these factors rather than concentrate their attention on students’ language proficiency. As such, in terms of designing and implementing feedback, it is necessary and important for teachers to be cognizant of students’ learning needs, beliefs about English learning/feedback through informal questionnaires and private talks with students, as well as reflect on the teacher-student relationship. By doing so, teachers can have a deeper understanding of the individual differences among their students and have opportunities to provide their students with individualized and customized feedback. With such feedback, students may attend to it more profoundly and help them reap the benefits from feedback.

Finally, apart from the above factors, our study also found that digital literacy was a crucial factor influencing students’ engagement with feedback in technology-enhanced learning environment. To facilitate engagement and learning in this AI age, digital literacy should be highlighted and teachers as well as university administrators shoulder the responsibility to help their students foster and develop digital literacy. To this end, different forms of training such as seminars and workshops are needed to scaffold students to improve their computer skills, critical thinking, and ability to search, evaluate and process information. Also, students should become self-trainers. Specifically, they can read the latest academic articles and books to acquire the cutting-edge knowledge about digital literacy and the strategies to improve it. Such effort by teachers, university administrators, and students themselves can enable students to enhance their digital literacy skills, being familiar with and at ease with technology. With digital literacy, students can adapt themselves to technology-empowered contexts and exert their agency to utilize technology to assist and facilitate their learning instead of being dominated by technology.

Unsurprisingly, our study is not free from limitations. In the second phase of our study, we mainly used post-writing instruments such as semi-structured interviews and writing journals to examine students’ engagement with SWCF. It may be difficult to capture the participants’ mental activities when they received and addressed the feedback and explore the teacher-student SWCF interaction to illustrate the different engagement styles. Accordingly, future research can employ the instruments such as think-aloud protocols and screencasts during the writing process to examine these issues. Additionally, due to some practical constraints (e.g., teaching schedule and the students’ availability), our study collected data from one round of writing task. Consequently, we could not track the potential changes of student engagement in the three dimensions. Given that student engagement is a malleable construct, longitudinal studies are needed.

Our study opens avenues for future studies. First, in our study, we centered on how L2 learners engaged with SWCF in terms of affect, behavior, and cognition. Given that students’ engagement is mediated by different modes of feedback, future studies examining and comparing how L2 learners attend to SWCF and AWCF affectively, behaviorally, and cognitively will be of interest. By doing so, we can have a nuanced insight into the similarities and differences of students’ engagement with the two types of WCF, which can generate valuable information for improving the effectiveness of WCF. In addition, while our study used large-scale questionnaires to collect data, it mainly focused on tertiary EFL learners in mainland China. As such, future research can recruit other populations of participants such as secondary school students and postgraduate students in other EFL countries. This can explore the sustainability and scalability of SWCF approach and examine whether our findings can transfer to other educational contexts.

Data availability

The data generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions or privacy but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bitchener J, Knoch U (2010) The contribution of written corrective feedback to language development: A ten month investigation. Appl Linguist 31(2):193–214

Bitchener J, Ferris DR (2012) Written feedback in L2 acquisition and writing. Routledge

Bitchener J, Storch N (2016) Written corrective feedback for L2 development. Multilingual Matters

Boudreau C, Maclntyre P, Dewaele J (2018) Enjoyment and anxiety in second language communication: An idiodynamic approach. Stud Second Lang Learn Teach 8(1):149–170

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101

Carless D, Boud D (2018) The development of student feedback literacy: Enabling uptake of feedback. Assess Eval High Educ 44(5):705–714

Cheng L, Hapmton J, Kumar S (2024) Engaging students via synchronous peer feedback in a technology-enhanced learning environment. J Res Technol Educ 56(3):347–371

Cheng X, Liu Y (2022) Student engagement with teacher written feedback: Insights from low-proficiency and high-proficiency L2 learners. System 109:102880

Cheng X, Zhang J (2024b) Engaging secondary school students with peer feedback in L2 writing classrooms: A mixed-methods study. Stud Educ Eval 81:101337

Cheng X, Zhang J, Yan Q (2025) Exploring teacher written feedback in EFL writing classrooms: Beliefs and practices in interaction. Lang Teach Res 29(1):385–415

Cheng X, Zhang LJ (2024a) Investigating synchronous and asynchronous written corrective feedback in a computer-assisted environment: EFL learners’ linguistic performance and perspectives. Comput Assist Lang Learn. (online first)

Cho H, Kim Y, Park S (2022) Comparing students’ responses to synchronous written corrective feedback during individual and collaborative writing tasks. Lang Aware 31(1):1–20

Chong SW (2019) College students’ perceptions of e-feedback: A grounded theory perspective. Assess Eval High Educ 46(1):92–104

Creswell JW (2014) Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Sage

Crosthwaite P (2017) Retesting the limits of data-driven learning: Feedback and error correction. Compute Assist Lang Learn 30(6):447–473

Dawson P, Henderson M, Mahoney P, Phillips M, Ryan T, Boud D, Molloy E (2019) What makes for effective feedback: staff and student perspectives. Assess Eval High Educ 44(1):25–36

DeKeyser R (2007) Practice in a second language: Perspectives from appliedlinguistics and cognitive psychology. Cambridge University Press

DeVellis RF (2012) Scale development: Theory and applications (3rd ed.). Sage

Dörnyei Z (2007) Research methods in applied linguistics: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methodologies. Oxford University Press

Ebadi S, Rahimi M (2017) Exploring the impact of online peer editing using Google Docs on EFL learners’ academic writing skills: A mixed-methods study. Comput Assist Lang Learn 30(8):787–815

Ellis R (2010) A framework for investigating oral and written corrective feedback. Stud Second Lang Acquis 32(2):335–349

Ene E, Upton T (2018) Synchronous and asynchronous teacher electronic feedback and learner uptake in ESL composition. J Second Lang Writ 41:1–13

Fan Y, Xu J (2020) Exploring student engagement with peer feedback on L2 writing. J Second Lang Writ 50:100775

Ferris DR (2002) Treatment of error in second language writing classes. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI

Fredricks J, Blumenfeld P, Paris A (2004) School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev Educ Res 74(1):59–109

Fredrickson BL (2013) Updated thinking on positivity ratios. Am Psychol 68(9):814–822

Han Y (2017) Mediating and being mediated: Learner beliefs and learner engagement with written corrective feedback. System 69:133–142

Han Y (2019) Written corrective feedback from an ecological perspective: The interaction between the context and individual learners. System 80:288–303

Han Y, Hyland F (2015) Exploring learner engagement with written corrective feedback in a Chinese tertiary EFL classroom. J Second Lang Writ 30:31–44

Handley K, Price M, Millar J (2011) Beydond ‘doing time’: Investigating the concept of student engagement with feedback. Oxf Rev Educ 37(4):543–560

Hayes JR, Flower LS (1980) Identifying the organization of writing process. In Gregee L, Steinberg E (eds), Cognitive processes in writing (pp. 3-30). Erlbaum

Henry A, Thorsen C (2018) Teacher-student relationships and L2 motivation. Mod Lang J 102(1):218–241

Hiver P, Mercer S, Al-Hoorie AH (2021) Student engagement in the language classroom. Multilingual Matters

Ho M (2015) The effects of face-to-face and computer-mediated peer review on EFL writers’ comments and revisions. Aust J Educ Technol 31(1):1–15

Kim Y, Choi B, Kang S, Kim B, Yun H (2020) Comparing the effects of direct and indirect synchronous written corrective feedback: Learning outcomes and students’ perceptions Foreign Lang Ann 53(1):176–199

Kourtali N (2022) The effects of face-to-face and computer-mediated recasts on L2 development. Lang Learn Technol 26(1):1–20

Li C, Jiang G, Dewaele J (2018) Understanding Chinese high school students’ foreign language enjoyment: Validation of the Chinese version of the foreign language enjoyment scale. System 76:183–196

Li J, Li M (2018) Turnitin and peer review in ESL academic writing classrooms. Lang Learn Technol 22(1):27–41

Liu Q, Brown D (2015) Methodological synthesis of research on the effectiveness of corrective feedback in L2 writing. J Second Lang Writ 30(4):66–81

Loncar M, Schams W, Liang J (2023) Multiple technologies, multiple sources: trends and analyses of the literature on technology-mediated feedback for L2 English writing published from 2015–2019. Comput Assist Lang Learn 36(4):722–784

Long MH (2007) Problems in SLA. Lawrence Erlbaum

Mao Z, Lee I (2024) Student engagement with written feedback: Critical issues and way forward. RELC J 55(3):810–818

Mao Z, Lee I, Li S (2024) Written corrective feedback in second language writing: A synthesis of naturalistic classroom studies. Lang Teach 57(4):449–474

Miles MB, Huberman AM (1994) Qualitative data analysis (2nd ed.). Sage Publications

Sauro S (2009) Computer-mediated corrective feedback and the development of L2 grammar. Lang Learn Technol 13(1):96–120

Shang H (2017) An exploration of asynchronous and synchronous feedback modes in EFL writing. J Comput High Educ 29(3):496–513

Shen R, Chong SW (2023) Learner engagement with written corrective feedback in ESL and EFL contexts: A qualitative research synthesis using a perception-based framework. Assess Eval High Educ 48(3):276–290