Abstract

Multifactorial interaction among lipoproteins, vascular wall cells, and inflammatory mediators has been recognized as the basis of atherogenesis. In the arterial wall high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and human secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) colocalize with vascular smooth muscle cells and concentrate in the atherosclerotic lesions. It has been shown that gr IIA sPLA2 hydrolyzes lipoproteins, altering their structure and releasing active agents such as lyso-phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho) and free fatty acids. We investigated the impact of normal HDL3 (NHDL3), acute phase HDL3 (APHDL3), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL), both unhydrolyzed and sPLA2-hydrolyzed, and some products of hydrolysis, such as lyso-PtdCho, oleic and linoleic acid, on [3H] thymidine incorporation by DNA of cultured human vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC). NHDL3 markedly enhanced mitogenic activity of VSMC in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Doubling of thymidine incorporation was usually achieved by 40 μg/ml of NHDL3 after 4 hours of incubation. APHDL3 had invariably a stronger inducing effect on the mitogenic activity than NHDL3; 40 μg/ml more than tripled [3H] thymidine incorporation after 4 hours of incubation. NHDL3 preincubated with human apo serum amyloid A apolipoprotein–induced higher mitogenic activity in VSMC than NHDL3 alone. Hydrolysis of NHDL3, APHDL3, or LDL by gr IIA sPLA2 markedly enhanced mitogenic activity of VSMC as compared with unhydrolyzed lipoproteins. sPLA2 concentrations that can be found in atherosclerotic vascular walls markedly enhanced lipoprotein-induced mitogenic activity of VSMC. sPLA2 per se did not affect thymidine incorporation and VSMC did not release sPLA2 into the medium. There was no evidence for hydrolysis of the wall of VSMC by gr IIA sPLA2. The presence of the products of hydrolysis of lipoproteins such as oleic and linoleic acids and lyso-PtdCho or their combinations with NHDL3 explains in part markedly enhanced mitogenic activity of VSMC. It is conceivable that sPLA2, which is known to colocalize with lipoproteins in the vascular wall in the domain of VSMC, is capable of induction of the mitogenic activity in these cells in vivo and should be considered as a proatherogenic enzyme.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is the end stage of a complex interaction of several types of vascular wall resident and infiltrating cells, lipoproteins, and a variety of inflammatory mediators (Daugherty, 1997; Libby et al, 1997; Steinberg and Witztum, 1990). Recently, substantial evidence has accumulated indicating that proinflammatory and immunologic factors play an important role in atherogenesis (Hajjar and Pomerantz 1992; Hansson et al, 1989; Nilsson, 1993; Wick et al, 1995; 1997). It was found that acute phase markedly influences the structure of lipoproteins (Malle et al, 1993; Pruzanski et al, 1998; 2000) and their functions (Kisilevsky and Subrahmanyan, 1992; Shephard et al, 1987; Van Lenten et al, 1995). In acute phase (Baumann and Gauldie, 1994; Steel and Whitehead, 1994) and in some chronic inflammatory diseases in which prolonged overexpression of acute phase reactants takes place (de Beer et al, 1982; Pruzanski et al, 1993; Vadas et al, 1993), serum amyloid A apolipoprotein (SAA) binds avidly to high-density lipoprotein (HDL), converting it into acute-phase (APHDL) (Malle et al, 1993; Van Lenten et al, 1995). While acquiring SAA, APHDL loses in part apo AI and apo AII, and some enzymes such as paroxonase and platelet activating factor (PAF)-acetylhydrolase (Van Lenten et al, 1995). Alterations in the lipid content of APHDL also occur (Pruzanski et al, 2000). APHDL is unable to protect against oxidation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and becomes proinflammatory (Van Lenten et al, 1995).

We reported that another acute phase reactant, human proinflammatory gr IIA secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) is almost invariably co-overexpressed with SAA (Vadas et al 1993). SAA was found to be a cofactor of sPLA2, markedly enhancing its hydrolytic activity (Pruzanski et al, 1995). In turn, sPLA2 hydrolyzes HDL, APHDL, and LDL, releasing lyso-compounds and free fatty acids (Pruzanski et al, 1998), which per se can modify the activity of and may be toxic to a variety of cells (Fang et al, 1997; Kume et al, 1992; Locher et al, 1992; Kaneko et al, 1996; Quinn et al, 1988; Yagi et al, 1996; Yamakawa et al, 1998). APHDL is hydrolyzed by sPLA2 faster than normal (N)HDL (Pruzanski et al, 1998).

It has been shown that in atherosclerosis, lipoproteins and sPLA2 are colocalized in the vascular wall, mainly in the domain of the smooth muscle cells (Hurt-Camejo et al, 1997; Robenek and Severs, 1993; Romano et al, 1998; Sartipy et al, 1998). Thus, it is of significant interest that in some diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, in which SAA and sPLA2 are co-overexpressed for long periods (de Beer et al, 1982; Pruzanski et al, 1994), accelerated atherosclerosis takes place (Bruce et al, 1998; Urowitz and Gladman, 1999). Furthermore, it has been shown that transgenic mice that overexpress human sPLA2 develop accelerated atherosclerosis (Ivandic et al, 1999). It has been shown that one of the important initial steps leading to atherosclerotic changes is proliferation and subsequent migration of the vascular smooth muscle cells (Raines and Ross, 1993; Rosenberg and Simons, 1996; Stein and Stein, 1995). Thus, it was important to investigate whether hydrolytic activity of human sPLA2, used in concentrations that occur in vivo, especially in the vascular wall, has an impact on lipoprotein-induced mitogenic effect in human vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) and whether APHDL enhances it more actively than normal HDL. Herein, we report that HDL3, APHDL3, and LDL hydrolyzed by gr IIA sPLA2 markedly enhanced thymidine incorporation and proliferation of human VSMC. Furthermore, known products of sPLA2-induced hydrolysis of lipoproteins, such as lyso-phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho), and oleic and linoleic acid also exerted a marked mitogenic effect. Thus, sPLA2 may be considered as a novel proatherogenic enzyme, which may be especially important in conditions in which its prolonged overexpression takes place.

Results

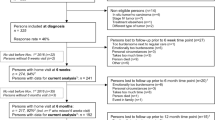

Basic Conditions of Human VSMC Cultures

Human VSMC were cultured with various concentrations of fatty acid free (FAF) BSA. When final BSA concentration was 0.1%, the mean [3H] thymidine incorporation was 10,865 ± 2,541 cpm (sd) per well (n = 12, in triplicate). The addition of 0.1% FAF BSA resulted in an insignificant change: 11,800 ± 5,973 cpm (sd) per well (n = 10, in triplicate). However, the addition of 10% FCS induced a marked increase in thymidine incorporation up to 30,947 ± 19,813 cpm (sd) per well (n = 12, in triplicate) or 607 ± 182% of controls (p < 0.01). The final concentration of FAF BSA in the media assumed more importance when the impact of normal HDL3 (NHDL3) on mitogenic activity was tested. Over the range of concentrations of 20 to 200 μg/ml of NHDL3 (n = 7), lower concentrations of BSA invariably resulted in a stronger induction of mitogenic activity by mitogens, increasing it up to 3.5-fold. Thus, the experiments were performed with low BSA concentrations. At the end of the culturing period before and after the tested agents were added, quiescent VSMC were viable ≥ 95%, and maintained the original shape and size. There was no increase in LDH in the supernatant.

Influence of NHDL3 on Human VSMC

The impact of NHDL3 (n = 6) on mitogenic activity of human VSCM was tested over the range of 20 to 400 μg/ml and incubation times of 1 hour to 24 hours. Invariably, NHDL3 markedly increased thymidine incorporation. Representative results are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. The increase over controls was dose-dependent and varied from 124 ± 29% at 20 μg/ml to 222 ± 36% at 100 μg/ml (p < 0.001). The incubation of VSMC with NHDL3 for 4 hours was usually sufficient to reach the maximum effect; however, the increase in mitogenic activity of 8% to 18% over the controls was already seen after 1 hour of incubation.

Influence of APHDL3 on Human VSMC

APHDL3 (n = 6) markedly enhanced mitogenic activity of VSMC in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Invariably APHDL3 was more active than NHDL3 (Fig. 1, Table 1). Equal mitogenic effect of APHDL3 was usually achieved by a half dose of NHDL3. After 4 hours of incubation, 25 μg/ml APHDL3 enhanced thymidine incorporation equally to 50 μg/ml NHDL3 (p = 0.003).

Influence of NHDL3 Preincubated with SAA on Human VSMC

Preincubation of NHDL3 with SAA (n = 3) led to a significant enhancement of [3H] thymidine incorporation into the human VSMC compared with NHDL3 alone (Fig. 2). As little as 5 μg/ml SAA preincubated with 40 μg/ml NHDL3 for 4 hours was sufficient to increase the incorporation by 25%.

The effect of serum amyloid A apolipoprotein (SAA) on the mitogenic activity of human VSMC induced by NHDL3. HDL3 50 μg/ml, SAA 10 and 25 μg/ml. SAA vs control, not significant; HDL3 vs control, p < 0.01; HDL3 + SAA 10 or 25 mg/ml vs control, p < 0.005; HDL3 + SAA 25 μg/ml vs HDL3, p < 0.01. This experiment represents three experiments (in triplicate) that gave comparable results.

Influence of NHDL3 Hydrolyzed by sPLA2 on Human VSMC

NHDL3 hydrolyzed by sPLA2 invariably increased thymidine incorporation in human VSMC much more than nonhydrolyzed NHDL3 (n = 12). The increase in mitogenic activity was related to the duration of the preincubation of NHDL3 with sPLA2 and to the concentration of sPLA2 (Fig. 3, Table 1). The longer the incubation time, the lower the concentration of sPLA2 required to induce a significant mitogenic effect. For example, incubation of 50 μg/ml NHDL3 with 100 ng/ml sPLA2 for 24 hours resulted in thymidine uptake of 41,285 ± 791 cpm/well, whereas a 48-hour preincubation with only 20 ng/ml sPLA2 enhanced incorporation to 45,955 ± 6,537 cpm/well. sPLA2 per se, tested at the range of 1 to 100 ng/ml, had no effect on mitogenic activity. [3H] thymidine incorporation, testing the effect of gr IIA sPLA2 (100 ng/ml) on VSMC exposed to the enzyme for 24 hours, was 12,093 ± 158 (sem) cpm/well as compared with the controls of 12,171 ± 178 (sem) cpm/well (n = 22). There was no evidence for hydrolysis of the cellular membrane of VSMC by extrinsic sPLA2. Cultured VSMC exposed or not exposed to lipoproteins did not release sPLA2 to the medium (n = 6). There was correlation between the incorporation of radiolabeled thymidine into the VSMC and the number of proliferating cells. As expected, HDL3 alone induced both; however, HDL3 hydrolyzed by sPLA2 further increased both variables (Table 2).

Induction of mitogenic activity in human VSMC by NHDL3 hydrolyzed by gr IIA secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2). Example of 12 experiments in triplicate. ♦ NHDL3 alone 50 μg/ml; ○ NHDL3 + sPLA2 2 ng/ml; ▪ NHDL3 + sPLA2 10 ng/ml; ▾ NHDL3 + sPLA2 20 ng/ml. At 48 hours, NHDL3 vs NHDL3 + sPLA2 10 ng/ml, p < 0.05. At 48 hours, HDL3 vs HDL3 + sPLA2 20 ng/ml, p < 0.01. The sPLA2 range of 2 to 20 ng/ml is equivalent to 80 to 800 U/ml. Such concentrations are similar to those in human serum and are observed in arterial atherosclerotic areas.

Influence of APHDL3 Hydrolyzed by sPLA2 on Human VSMC

Hydrolysis of APHDL3 by sPLA2 enhanced the effect on mitogenic activity of human VSMC (n = 12) proportionately to the time of incubation and the concentration of sPLA2 (Fig. 4, Table 1). The relative effect of sPLA2 on the induction of mitogenic activity by APHDL3 was less than that of NHDL3, because APHDL3 per se was invariably enhancing thymidine incorporation much more than NHDL3. Thus, additional enhancement by APHDL3 hydrolyzed by sPLA2 was less but clearly evident (Fig. 4, Table 1). APHDL3 per se, especially hydrolyzed by sPLA2, enhanced proliferation of the VSMC significantly more than HDL3 and LDL (Table 2).

Influence of LDL Unhydrolyzed and sPLA2-Hydrolyzed on Human VSMC

LDL added to the cultured VSMC markedly enhanced mitogenic activity (n = 3, in triplicate). LDL per se enhanced mitogenic activity more than NHDL3 or APHDL3 (Table 1). LDL hydrolyzed by sPLA2 also enhanced mitogenic activity more than identically treated NHDL3 or APHDL3 (Table 1). LDL alone and LDL hydrolyzed by sPLA2 enhanced proliferation of VSMC significantly more than HDL3 (Table 2).

Influence of Lyso-PtdCho, and Linoleic and Oleic Acids on Human VSMC

Lyso-PtdCho was tested at the concentration range of 10 to50 μm. Concentrations above 30 μm were toxic to the cells as tested by the number of cells and LDH in the supernatant. Lyso-PtdCho (20 μm, n = 5), enhanced thymidine incorporation up to 245 ± 42% of the control, whereas dp PtdCho (10 to 50 μm) had no effect on mitogenic activity of human VSMC. Dose-response of linoleic and oleic acids were tested in the range of 5 to 50 μm. The optimal concentrations of both fatty acids to increase [3H] thymidine incorporation were 10 to 20 μm. Concentrations of linoleic acid above 20 μm and of oleic acid above 30 μm were toxic to the cells. These were, therefore, the maximum concentrations used (Table 3). Linoleic and oleic acids markedly enhanced mitogenic activity of human VSMC, and combinations of lyso-PtdCho with either linoleic or oleic acid were invariably more active than each agent tested separately (Table 3). When NHDL3 (50 μg/ml) was preincubated for 4 hours with lyso-PtdCho (20 μm), oleic acid (20 μm), or linoleic acid (20 μm), and then the mixture was added to the culture of VSMC, there was a marked increase in mitogenic activity of 183%, 239%, and 191%, respectively, compared with NHDL3 alone.

Influence of grIIA sPLA2 on Human VSMC

To rule out the possibility that sPLA2 per se may release phospholipids from the cell membrane, VSMC were incubated for 24 hours with sPLA2, 1 μg/ml. The supernatant was tested for the presence of PtdCho, PtdEtn, SM, lyso-PtdCho and fatty acids, palmitic, stearic, linoleic, oleic, arachidonic, and others as described (Pruzanski et al, 2000). The supernatants from the cells exposed to sPLA2 contained only traces of PtdCho and SM identical to those in the controls. Washed and sonicated cells showed readily detectable amounts of PtdCho, with smaller amounts of PtdEt and SM. There was almost no lyso-PtdCho.

Discussion

The protective role of HDL in the atherosclerotic process is related, in part, to the prevention of the generation of oxidized LDL (Parthasarathy et al, 1990; Steinberg and Witztum 1990). However, investigation of the enzymes linked to HDL, such as lecithin: cholesterol acyl transferase, paraoxonase (PON), PAF-acetylhydrolase (PAF-AH), and others (Navab et al, 1998; Tall, 1990), has indicated much more complex functional roles of HDL (Navab et al, 1998). It was stated that to function normally, HDL has to maintain equilibrium between its apolipoproteins and enzymatic content. For example, in transgenic mice, HDL overexpressing apo A II has a lower content of PON, is unable to protect against oxidation of LDL, and induces monocyte transmigration (Castellani et al, 1997).

In acute phase, when SAA is replacing, in part, apo A I and apo A II, HDL is losing PON and PAF-AH, and is unable to maintain its protective activity (Van Lenten et al, 1995). The addition of external PON to such HDL reinstates its normal function (Van Lenten et al, 1995; Aviram et al, 1998). Because a substantial part of apo A-I is lost during conversion of HDL into APHDL, and because apo A I contains the major part of lecithin: cholesterol acyl transferase, this enzyme activity is also lost in part during conversion (Van Lenten et al, 1995). We recently reported that acute phase HDL also has a substantially different lipid structure from normal HDL (Pruzanski et al, 2000).

Several other functions of HDL have also been described, such as the inhibition of PAF synthesis in stimulated endothelial cells, presumably by inhibiting the activation of acetyltransferase (Sugatani et al, 1996). HDL induced the synthesis of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in VSMC (Pomerantz et al, 1984) and the activators of PLA2 were additive or synergistic with HDL in the induction of PGE2. Because it was reported that PGE2 inhibits VSMC proliferation (Hajjar and Pomerantz, 1992), these results could imply that PLA2 inhibits the proliferative activity of HDL. But our study definitely shows that hydrolysis of NHDL3 by sPLA2 markedly enhances mitogenic activity of VSMC. Therefore, the putative induction of PGE2 by HDL is either inhibited by the hydrolytic process or the protective activity of PGE2 is counteracted by the products of hydrolysis, or both.

Physiologically VSMC are not exposed to the serum, that is to the circulating HDL. It was found, however, that HDL localizes in the arterial wall in the cellular compartment and along with LDL is internalized by the macrophages and by VSMC, especially in the atherosclerotic plaques (Robenek and Severs, 1993). Since sPLA2 co-localizes in the same areas (Hurt-Camejo et al, 1997; Romano et al, 1998; Sartipy et al, 1998), it most probably is capable of interacting with lipoproteins in situ.

Recently, attention has been directed to the alterations of normal HDL induced by acute phase reactants (Malle et al, 1993; Pruzanski et al, 1998). In acute phase, SAA may increase 1,000-fold and binds avidly to HDL, partly displacing apo A I and apo A II (Malle et al, 1993). SAA may be overexpressed for long periods in some chronic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (de Beer et al, 1982). SAA converts HDL into APHDL reducing its protective function (Malle et al, 1993; Van Lenten et al; 1995. During inflammation, APHDL3 is cleared more rapidly from the circulation (Malle et al, 1993). Its affinity to hepatocytes declines and the affinity to macrophages increases as compared with HDL (Kisilevsky and Subrahmanyan, 1992). APHDL3 was found to be degraded 5 to 10 times faster during incubation with neutrophils or neutrophil-conditioned medium (Shephard et al, 1987).

We have reported that another acute phase reactant, human gr IIA sPLA2, hydrolyzes NHDL and APHDL (Pruzanski et al, 1998), thus linking this proinflammatory enzyme to the atherogenic process. APHDL was hydrolyzed by sPLA2 faster and more extensively than NHDL (Pruzanski et al, 1998). Conversely, SAA and APHDL were found to increase the hydrolytic activity of sPLA2, implying that SAA may serve as a cofactor of sPLA2 (Pruzanski et al, 1995). sPLA2 is produced by a variety of cells (Vadas et al, 1993) and can increase 1,000-fold or more in acute inflammatory processes (Vadas et al, 1993). Prolonged overexpression of sPLA2 was found in several diseases such as RA (Lin et al, 1996) and SLE (Pruzanski et al, 1994), that is in the same conditions in which overexpression of SAA takes place (Steel and Whitehead, 1994). In RA the concentrations of circulating sPLA2 may reach values above 400 ng/ml (Lin et al, 1996), whereas in SLE concentrations above 300 ng/ml were found (Pruzanski et al, 1994). Its induction is controlled by the same agents that induce SAA, such as cytokines, endotoxin, and others (Vadas et al, 1993). sPLA2 is present in the media in normal and more so in atherosclerotic arteries specifically colocalizing with VSMC (Hurt-Camejo et al, 1997; Romano et al, 1998). In the atherosclerotic wall, sPLA2 was detected both extracellularly in the lipid core, binding avidly to the proteoglycans synthesized by VSMC (Sartipy et al, 1998), and intracellularly in the macrophages (Hurt-Camejo et al, 1997; Romano et al, 1998). We found concentrations of sPLA2 exceeding 50 ng/mg wet weight in the atherosclerotic arterial walls (Pruzanski et al, unpublished). A specific receptor for sPLA2 was found in some human tissues (Ancian et al, 1995) and is present on the VSMC (M. Lazdunski, personal communication), but no information is available about the effect of the interaction of extrinsic sPLA2 with its receptor on the functions of VSMC.

There are no reports regarding the effect of sPLA2 on proliferation of VSMC. In one study inhibitors of 14 kDa PLA2 had no effect, whereas inhibitors of 85 kDa PLA2 inhibited proliferation of VSMC, suggesting that cytosolic PLA2-mediated liberation of arachidonic acid is required for cell proliferation (Anderson et al, 1997). Our study shows that extrinsic secretory gr IIA sPLA2 per se does not affect the mitogenic activity of VSMC. However, NHDL3 and especially APHDL3 hydrolyzed by sPLA2, markedly enhance [3H] thymidine incorporation by VSMC. Our study also shows that preincubation of NHDL3 with SAA increases mitogenic activity of VSMC more than NHDL3 alone. It does not rule out the possibility that other differences between APHDL3 and NHDL3 may also play a role in the enhancement of mitogenic activity of VSMC. Since hydrolysis of lipoproteins by sPLA2 is associated with marked increase in the lysocompounds and free fatty acids, it is conceivable that the impact of sPLA2 on VSMC is mediated, in part, through the above hydrolytic products. Indeed, lyso-PtdCho, and linoleic and oleic acids and their combinations markedly increased the mitogenic activity of VSMC. We used conventional concentrations of the above products of hydrolysis of lipoproteins (Bandyopadhyay et al, 1987; Keler et al, 1992; Rao et al 1995; Wang et al 1991), but their concentrations in the vascular wall are not known presently, and therefore their relative in vivo impact cannot be estimated.

The impact of LDL on mitogenic activity of VSMC was found to vary, depending on experimental conditions (Chen et al, 1986; Fang et al, 1997; Heery et al, 1995; Leitinger et al, 1999; Libby et al, 1985; Locher et al, 1992; Parthasarathy, et al 1990; Scott-Burden et al, 1989). Whereas only a minimal effect was reported (Libby et al 1985), others found that LDL has a definite mitogenic effect (Fang et al, 1997; Locher et al, 1992). The effect was more pronounced when VSMC were cultured in low-serum medium (Chen et al, 1986) or when LDL was oxidized (Heery et al, 1995). In our system, LDL induced pronounced mitogenic activity that was further enhanced by extrinsic sPLA2. The issue of whether LDL possesses intrinsic PLA2 activity (Parthasarathy and Barnett, 1990) has not been solved, because no PLA2 enzyme was extracted from LDL. Studies of the impact of sPLA2 on LDL have shown that extrinsic sPLA2 hydrolyzes LDL (Pruzanski et al, 1998) and that sPLA2–treated LDL is more efficiently oxidized by cocultures of VSMC with endothelial cells than untreated LDL (Leitinger et al, 1999).

VSMC also proliferate in response to IL-6 (Gaumond et al, 1997; Loppnow and Libby, 1990; Nabata et al, 1990), which is induced by PAF (Gaumond et al, 1997) and is synthesized and released from VSMC, especially when the cells are stimulated by IL-1 or PDGF (Loppnow and Libby, 1990). Activation of IL-6 in VSMC by chlamydial HSP 60 has recently been reported (Kol et al, 1999).

The impact of enzymes linked to lipoproteins on mitogenesis of VSMC has been investigated only recently. Mitogenic activity of VSMC induced by oxLDL was blocked by PAF-receptor antagonist (Heery et al, 1995), and generation of bioactive phospholipids during oxidation of LDL was blocked by PAF-AH (Heery et al, 1995). Yet, PAF inhibitor, SR 27417, did not inhibit the mitogenic effect of PAF on rabbit VSMC (Herbert et al, 1995). Another study reported that in LDL PAF-AH mediates conversion of PtdCho into lyso-PtdCho (Steinbrecher and Pritchard, 1989), a known stimulator of VSMC proliferation. The role of other enzymes such as PON or sphingomyelinase in the induction of mitogenic activity of VSMC has not yet been reported. Our study has shown that human extrinsic gr IIA sPLA2 markedly enhances the mitogenic activity of lipoproteins and their effect on proliferation of VSMC. Therefore, hydrolysis of lipoproteins that colocalize with sPLA2 in the arterial wall may enhance the atherosclerotic process. It remains to be seen whether sPLA2 inhibitors can serve as novel antiatherogenic agents.

Materials and Methods

Blood samples were obtained with informed consent from healthy individuals and from patients in acute phase after cardiac surgery. NHDL3 and APHDL3 were isolated by sequential ultracentrifugation as described (Pruzanski et al, 1998), and purified fractions p 1.13 to 1.18 g/ml were used. Concentration of lipoproteins was expressed in micrograms of protein content. Recombinant human group IIA PLA2 was kindly provided by Dr. J. Browning, Biogen, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Synthetic recombinant human apo SAA was obtained from Pepro Tech (Rocky Hill, New Jersey). This SAA corresponds to human apo SAA 1α with the exception of the N-terminal methionine and substitution of asparagine for aspartic acid at position 60, and was found to be biologically active (Badolato et al, 1994; Su et al, 1999). NHDL3 was preincubated with SAA for 4 hours and then added to the cultures of human VSMC as described.

Cell Culture

Human aortal VSMC were obtained from Cascade Biologics (Portland, Oregon) and maintained as recommended by the supplier. VSMC were plated at 4 × 104/well. Cells were grown in medium 231 containing smooth muscle cell growth supplement (Cascade Biologics). Only passages 6 and 7 were used for experiments. Before treatment with various agents, VSMC were made quiescent by culturing them for 48 hours (with one medium change after 24 hours) in serum-free medium containing FFA free 0.1% BSA, insulin-transferrin-selenium supplement (ITS) (Gibco BRL, Burlington, Ontario, Canada), 0.1 mm vitamin C, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/ml amphotericin B (P/S). In each experiment, the initial and final cell count were made and LDH concentration was tested in the medium. Microscopic assessment of the size and shape of cells and of detachment was made.

Hydrolysis of Lipoproteins with rh gr IIA PLA2

Lipoproteins at concentration 1 to 2 mg/ml in 100 mm TrisHCI buffer, pH 8.0, containing 10 mm CaCI2 and 0.2 mg/ml BSA (fatty acid free) were incubated with human recombinant gr II A PLA2 at concentrations ranging from 0.05 to 5 μg/ml, for desired periods of time, at 37° C (Pruzanski et al 1998). Controls were maintained in identical conditions.

Measurement of DNA Synthesis

[3H] thymidine incorporation was measured to determine the effect on human VSMC DNA synthesis. Quiescent cells were treated with various agents (see below) and 1 μCi of [3H] thymidine was added (methyl- [3H] thymidine 50 Ci/mmol; Amersham, Oakville, Ontario, Canada). After incubation for 24 hours, cells were washed once with 2 ml of ice-cold methanol for 10 minutes, extracted three times with 2 ml of cold 10% TCA for 5 minutes each time, and solubilized for at least 30 minutes at room temperature in 0.25 ml 0.3 n NaOH, 1% SDS. After neutralizing with 0.25 ml 0.3 n HCI, [3H] thymidine activity was measured in a liquid scintillation counter (Beckman LS 7500). Each experiment was performed in triplicate or quadruplicate.

In a separate series of experiments (n = 4), the incorporation of [3H] thymidine into VSMC exposed for 24 hours to lipoproteins and to lipoproteins hydrolyzed with sPLA2 was compared with the number of proliferating cells as described (Heery et al, 1995) (Table 2).

Agents Tested for Induction of Mitogenic Activity of VSMC

Human VSMC were incubated with various concentrations of unhydrolyzed or sPLA2-hydrolyzed NHDL3, APHDL3, or LDL, or with L-α-lysophosphatidylcholine, palmitoyl (C 16:0) approximate purity 99%, molecular weight (MW) 495.6; linoleic acid (cis-9, cis-12-octadecadienoic acid) MW 280.4, minimum purity 99%; or oleic acid (cis-9-octadecenoic acid) MW 282.5 approximate purity 99% (Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, Ontario, Canada). These agents were dissolved in ethanol, using a final nontoxic concentration of 0.1%, which was also used in controls.

Statistical analysis was performed by Student t test, Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test, and Bartlett's test for homogeneity of variances. [Au: These references were not cited in the text: Jimi et al, 1995; Parthasarathy and Barnett, 1990.]

References

Ancian P, Lambeau G, Mattei M-G, and Lazdunski M (1995). The human 180-kDa receptor for secretory phospholipases A2: Molecular cloning, identification of a secreted soluble form, expression, and chromosomal localization. J Biol Chem 270: 8963–8970.

Anderson KM, Roshak A, Winkler JD, McCord M, and Marshall LA (1997). Cytosolic 85-kDa phospholipase A2-mediated release of arachidonic acid is critical for proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 272: 30504–30511.

Aviram M, Rosenblat M, Bisgaier CL, Newton RS, Primo-Parmo SL, and La Du BN (1998). Paraoxonase inhibits high-density lipoprotein oxidation and preserves its functions: A possible peroxidative role for paraoxonase. J Clin Invest 101: 1581–1590.

Badolato R, Wang JM, Murphy WJ, Lloyd AR, Michiel DF, Bausserman LL, Kelvin DJ, and Oppenheim JJ (1994). Serum amyloid A is a chemoattractant: Induction of migration, adhesion and tissue infiltration of monocytes and polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Exp Med 180: 203–209.

Bandyopadhyay GK, Imagawa W, Wallace D, and Nandi S (1987). Linoleate metabolites enhance the in vitro proliferative response of mouse mammary epithelial cells to epidermal growth factor. J Biol Chem 262: 2750–2756.

Baumann H and Gauldie J (1994). The acute phase response. Immunol Today 15: 74–80.

Bruce IN, Gladman DD, and Urowitz MB (1998). Detection and modification of risk factors for coronary artery disease in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: A quality improvement study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 15: 435–440.

Castellani LW, Navab M, Lenten BJV, Hedrick CC, Hama SY, Goto AM, Fogelman AM, and Lusis AJ (1997). Overexpression of apolipoprotein all in transgenic mice converts high density lipoproteins to proinflammatory particles. J Clin Invest 100: 464–474.

Chen J-K, Hoshi H, McClure DB, and McKeehan WL (1986). Role of lipoproteins in growth of human adult arterial endothelial and smooth muscle cells in low lipoprotein-deficient serum. J Cell Physiol 129: 207–214.

Daugherty A (1997). Atherosclerosis: Cell biology and lipoproteins. Curr Opin Lipidol 8: U11–U12.

de Beer FC, Fagan EA, Hughes GRV, Mallya RK, Lanham JG, and Pepys MB (1982). Serum amyloid-A protein concentration in inflammatory diseases and its relationship to the incidence of reactive systemic amyloidosis. Lancet 2: 231–237.

Fang X, Gibson S, Flowers M, Furui T, Bast RC Jr, and Mills GB (1997). Lysophosphatidylcholine stimulates activator protein 1 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase activity. J Biol Chem 272: 13683–13689.

Gaumond F, Fortin D, Stankova J, and Rola-Pleszczynski M (1997). Different signaling pathways in platelet-activating factor-induced proliferation and interleukin-6 production by rat vascular smooth muscle cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 30: 169–175.

Hajjar DP and Pomerantz KB (1992). Signal transduction in atherosclerosis: Integration of cytokines and the eicosanoid network. FASEB J 6: 2933–2941.

Hansson GK, Jonasson L, Seifert PS, and Stemme S (1989). Immune mechanisms in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 9: 567–578.

Heery JM, Kozak M, Stafforini DM, Jones DA, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM, and Prescott SM (1995). Oxidatively modified LDL contains phospholipids with platelet-activating factor-like activity and stimulates growth of smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest 96: 2322–2330.

Herbert JM, Laplace MC, Mares AM, and Dol F (1995). Platelet-activating factor (PAF) is not an essential component of the cascade leading to smooth muscle cell proliferation following vascular injury. J Lipid Mediat Cell Signal 12: 49–57.

Hurt-Camejo E, Andersen S, Standal R, Rosengren B, Sartipy P, Stadberg E, and Johansen B (1997). Localization of nonpancreatic secretory phospholipase A2 in normal and atherosclerotic arteries: Activity of the isolated enzyme on low-density lipoproteins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 17: 300–309.

Ivandic B, Castellani LW, Wang X-P, Qiao J-H, Mehrabian M, Navab M, Fogelman AM, Grass DS, Swanson ME, de Beer MC, de Beer F, and Lusis AJ (1999). Role of group II secretory phospholipase A2 in atherosclerosis. 1. Increased atherogenesis and altered lipoproteins in transgenic mice expressing group IIA phospholipase A2 . Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 19: 1284–1290.

Kaneko T, Baba N, and Matsuo M (1996). Cytotoxicity of phosphatidylcholine hydroperoxides is exerted through decomposition of fatty acid hydroperoxide moiety. Free Radic Biol Med 21: 173–179.

Keler T, Barker CS, and Sorof S (1992). Specific growth stimulation by linoleic acid in hepatoma cell lines transfected with the target protein of a liver carcinogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 4830–4834.

Kisilevsky R and Subrahmanyan L (1992). Serum amyloid A changes high density lipoprotein's cellular affinity. A clue to serum amyloid A's principal function. Lab Invest 66: 778–785.

Kol A, Bourcier T, Lichtman AH, and Libby P (1999). Chlamydial and human heat shock protein 60s activate human vascular endothelium, smooth muscle cells, and macrophages. J Clin Invest 103: 571–577.

Kume N, Cybulsky MI, and Gimbrone MA Jr (1992). Lysophosphatidylcholine, a component of atherogenic lipoproteins, induces mononuclear leukocyte adhesion molecules in cultured human and rabbit arterial endotheial cells. J Clin Invest 90: 1138–1144.

Leitinger N, Watson AD, Hama SY, Ivandic B, Qiao J-H, Huber J, Faull KF, Grass DS, Navab M, Fogelman AM, de Beer FC, Lusis AJ, and Berliner JA (1999). Role of group II secretory phospholipase A2 in atherosclerosis. 2. Potential involvement of biologically active oxidized phospholipids. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 19: 1291–1298.

Libby P, Sukhova B Lee RT, and Liao JK (1997). Molecular biology of atherosclerosis. Int J Cardiol 2: S23–S29.

Libby P, Miao P, Ordovas JM, and Schaefer EJ (1985). Lipoproteins increase growth of mitogen-stimulated arterial smooth muscle cells. J Cell Physiol 124: 1–8.

Lin MK, Farewell V, Vadas P, Bookman AAM, Keystone EC, and Pruzanski W (1996). Secretory phospholipase A2 as an index of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: Prospective double blind study of 212 patients. J Rheumatol 23: 1162–1166.

Locher R, Weisser B, Mengden T, Brunner C, and Vetter W (1992). Lysolecithin actions on vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 183: 156–162.

Loppnow H and Libby P (1990). Proliferating or interleukin 1-activated human vascular smooth muscle cells secrete copious interleukin 6. J Clin Invest 85: 731–738.

Malle E, Steinmetz A, and Raynes JG (1993). Serum amyloid A (SAA): An acute phase protein and apolipoprotein. Atherosclerosis 102: 131–146.

Nabata T, Morimoto S, Koh E, Shiraishi T, and Ogihara T (1990). Interleukin-6 stimulates c-myc expression and proliferation of cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Int 20: 445–453.

Navab M, Hama SY, Hough GP, Hedrick CC, Sorenson R, La Du BN, Kobashigawa JA, Fonarrow GC, Berliner JA, Laks H, and Fogelman AM (1998). High density associated enzymes: Their role in vascular biology. Curr Opin Lipidol 9: 449–456.

Nilsson J (1993). Cytokines and smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res 27: 1184–1190.

Parthasarathy S and Barnett J (1990). Phospholipase A2 activity of low density lipoprotein: Evidence for an intrinsic phospholipase A2 activity of apoprotein B-100. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 9741–9745.

Parthasarathy S, Barnett J, and Fong LG (1990). High-density lipoprotein inhibits the oxidative modification of low-density lipoprotein. Biochim Biophys Acta 1044: 275–283.

Pomerantz KB, Tall AR, Feinmark SJ, and Cannon PJ (1984). Stimulation of vascular smooth muscle cell prostacyclin and prostaglandin E2 synthesis by plasma high and low density lipoproteins. Circ Res 54: 554–565.

Pruzanski W, de Beer FC, de Beer MC, Stefanski E, and Vadas P (1995). Serum amyloid A protein enhances the activity of secretory non-pancreatic phospholipase A2 . Biochem J 309: 461–464.

Pruzanski W, Goulding NJ, Flower RJ, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Goodman PJ, Scott KF, and Vadas P (1994). Circulating group II phospholipase A2 activity and antilipocortin antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus: Correlative study with disease activity. J Rheumatol 21: 252–257.

Pruzanski W, Stefanski E, de Beer FC, de Beer MC, Ravandi A, and Kuksis A (2000). Comparative analysis of lipid composition of normal and acute phase high density lipoproteins. J Lipid Res 41: 1035–1047.

Pruzanski W, Stefanski E, de Beer FC, de Beer MC, Vadas P, Ravandi A, and Kuksis A (1998). Lipoproteins are substrates for human secretory group IIA phospholipase A2: Preferential hydrolysis of acute phase HDL. J Lipid Res 39: 2150–2160.

Pruzanski W, Vadas P, and Browning J (1993). Secretory non-pancreatic group II phospholipase A2: Role in physiologic and inflammatory processes. J Lipid Med 8: 161–167.

Quinn MT, Parthasarathy S, and Steinberg D (1988). Lysophosphatidylcholine: A chemotactic factor for human monocytes and its potential role in atherogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85: 2805–2809.

Raines EW and Ross R (1993). Smooth muscle cells and the pathogenesis of the lesions of atherosclerosis. Br Heart J 69: S30–S37.

Rao GN, Alexander RW, and Runge MS (1995). Linoleic acid and its metabolites, hydroxyoctadecadienoic acids, stimulate c-Fos, c-Jun and c-Myc mRNA expression, mitogen-activated protein kinase activation, and growth in rat aortic smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest 96: 842–847.

Robenek H and Severs NJ (1993). Lipoprotein receptors on macrophages and smooth muscle cells. Curr Top Pathol 87: 73–123.

Romano M, Romano E, Bjorkerud S, and Hurt-Camejo E (1998). Ultrastructural localization of secretory type II phospholipase A2 in atherosclerotic and nonatherosclerotic regions of human arteries. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 18: 519–525.

Rosenberg RD and Simons M (1996). Vascular smooth-muscle-cell proliferation: Basic investigations and new therapeutic approaches. In: Mockrin SC, editor. Molecular genetics and gene therapy of cardiovascular disease. New York: Marcel Dekker, 547–581.

Sartipy P, Bondjers G, and Hurt-Camejo E (1998). Phospholipase A2 type II binds to extracellular matrix biglycan: Modulation of its activity on LDL by colocalization in glycosaminoglycan matrixes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 18: 1934–1941.

Scott-Burden T, Resink TJ, Hahn AWA, Baur U, Box RJ, and Buhler FR (1989). Induction of growth-related metabolism in human vascular smooth muscle cells by low density lipoprotein. J Biol Chem 264: 12582–12589.

Shephard EG, de Beer FC, de Beer MC, Jeenah MS, Coetzee GA, and van der Westhuyzen DR (1987). Neutrophil association and degradation of normal and acute-phase high-density lipoprotein 3. Biochem J 248: 919–926.

Steel DM and Whitehead AS (1994). The major acute phase reactants: C-reactive protein, serum amyloid P component and serum amyloid A protein. Immunol Today 15: 81–88.

Stein O and Stein Y (1995). Smooth muscle cells and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol 6: 269–274.

Steinberg D and Witztum JL (1990). Lipoproteins and atherogenesis: Current concepts. JAMA 264: 3047–3052.

Steinbrecher UP and Pritchard PH (1989). Hydrolysis of phosphatidylcholine during LDL oxidation is mediated by platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase. J Lipid Res 30: 305–315.

Su BSB, Gong W, Gao J-L, Shen W, Murphy PM, Oppenheim JJ, and Wang JM (1999). A seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor, FPRL1, mediates the chemotactic activity of serum amyloid A for human phagocytic cells. J Exp Med 189: 395–402.

Sugatani J, Miwa M . Komiyama Y, and Ito S (1996). High-density lipoprotein inhibits the synthesis of platelet-activating factor in human vascular endothelial cells. J Lipid Mediat Cell Signal 13: 73–88.

Tall AR (1990). Plasma high density lipoproteins: Metabolism and relationship to atherogenesis. J Clin Invest 86: 379–384.

Urowitz MB and Gladman DD (1999). Evolving spectrum of mortality and morbidity in SLE. Lupus 8: 253–255.

Vadas P, Browning J, Edelson J, and Pruzanski W (1993). Extracellular phospholipase A2 espression and inflammation: The relationship with associated disease states. J Lipid Mediat 8: 1–30.

Van Lenten BJ, Hama SY, de Beer FC, Stafforini DM, McIntyre TM, Prescott SM, La Du BN, Fogelman AM, and Navab M (1995). Anti-inflammatory HDL becomes pro-inflammatory during the acute phase response. Loss of protective effect of HDL against LDL oxidation in aortic wall cell cocultures. J Clin Invest 96: 2758–2767.

Wang T and Powell WS (1991). Increased levels of monohydroxy metabolites of arachidonic acid and linoleic acid in LDL and aorta from atherosclerotic rabbits. Biochem Biophys Acta 1084: 129–138.

Wick G, Romen M, Amberger A, Metzler B, Mayr M, Falkensammer G, and Xu Q (1997). Atherosclerosis, autoimmunity, and vascular-associated lymphoid tissue (Review). FASEB J 11: 1199–1207.

Wick G, Schett G, Amberger A, Kleindienst R, and Xu Q (1995). Is atherosclerosis an immunologically mediated disease? Immunol Today 16: 27–33.

Yagi K, Komura S, Kojima H, Sun Q, Nagata N, Ohishi N, and Nishikimi M (1996). Expression of human phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase gene for protection of host cells from lipid hydroperoxide-mediated injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 219: 486–491.

Yamakawa T, Eguchi S, Yamakawa Y, Motley ED, Numaguchi K, Utsunomiya H, and Inagami T (1998). Lysophosphatidylcholine stimulates MAP kinase activity in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension 31: 248–253.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid from The Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario.

We are grateful to Dr. F. C. de Beer for the generous gift of purified lipoproteins.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pruzanski, W., Stefanski, E., Kopilov, J. et al. Mitogenic Effect of Lipoproteins on Human Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells: The Impact of Hydrolysis by gr II A Phospholipase A2. Lab Invest 81, 757–765 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.3780284

Received:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.3780284

This article is cited by

-

Diverse activity of human secretory phospholipases A2 on the migration of human vascular smooth muscle cells

Inflammation Research (2015)