Abstract

Liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinomas are two major causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide, and can synergistically interact to expedite the tumor progression. How fibrosis promotes the hepatoma growth remains completely unexplained. Using an in situ murine hepatoma model together with fibrosis induction by thioacetamide (TAA), the hepatoma growth and the immune factors in the fibrotic liver were analyzed. We found that TAA–fibrosis induction enhanced hepatoma cell growth in the liver and increased the mortality of hepatoma-bearing mice. The tumor-infiltrating CD4+ or CD8+ T cells are downregulated by fibrosis induction. The Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Treg) cells were induced. We conclude that fibrosis induction causes further immunosuppression, in which Treg cells exert a downregulation effect on the antitumor immunity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Liver cancer is the predominant cause of cancer mortality in males of Southern China and Taiwan. Most liver cancers are hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC), which have unique epidemiologic features with dynamic temporal trends, and vary in different geographic regions, racial and ethnic group, sex and risk factors.1, 2, 3 Although its hepatocarcinogenesis is not clearly illustrated, chronic active hepatitis is recognized as the major risk factor for HCC, and is accompanied by liver cell necrosis, inflammation, cytokine abnormal synthesis and fibrosis. The most common condition associated with hepatocarcinogenesis is cirrhosis, which develops after a latency of 20–40 years of chronic liver disease. HCC risk remains low during chronic liver disease, but exponentially increases at the cirrhosis stage, suggesting that important events precipitate the increase in liver tumor formation at the cirrhosis stage.

Cirrhosis causes alterations of the liver environment by altering the cytokine secretion from activated stellate cells and inflammatory signaling from infiltrating immune cells.4 Liver fibrosis, a wound-healing response to a variety of chronic stimuli, is characterized by excessive deposition of extracellular matrix protein with type I collagen predominance. The activation of the hepatic stellate cells is primarily responsible for excess collagen deposition and amplifying the fibrogenic response. Its initiation is provoked by oxidative stress, apoptotic bodies, LPS, cytokines and so on. Perpetuation follows, including proliferation, contractility, fibrogenesis, altered matrix degradation, chemotaxis and inflammatory signaling. Cirrhosis, the most advanced stage of fibrosis, indicates not only more scar than fibrosis alone, but also distortion of the liver parenchyma, altered blood flow and risk of liver failure. However, it remains in a dynamic and evolving state with fibrosis.5, 6 How fibrosis promotes hepatoma growth remains unclear. In this study, we use an in situ murine hepatoma model to evaluate the progressive growth of hepatoma in a fibrotic liver. Our studies show that hepatoma cells grow faster in a fibrotic liver environment, as the fibrosis induction-associated immunosuppression with regulatory T cells (Treg) will downregulate the antitumor response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse Model

Eight- to ten-week-old male BALB/c mice were treated with thioacetamide (TAA) 200 mg/kg by intraperitoneal injection three times a week for 4 weeks to induce liver fibrosis.7 The in situ murine hepatoma model was established as previously described.8 In brief, mouse hepatoma ML1 cells were injected into the mouse spleen, and after colonizing in the spleen, ML1 migrated to the liver, forming different sizes of hepatoma nodules. Three treatment schedules were used as shown in Figure 1. TAA injection after ML-1 implantation represents fibrosis induction after tumor growth (ML1–TAA). TAA injection before ML1 implantation represents tumor growth after fibrosis (TAA–ML1). TAA continuing treatment is the combination of the above two protocols (TAA–ML1–TAA), in which mice was first treated with TAA for 2 weeks, ML1 was then implanted, and then treated for a further 2 weeks with TAA injection. Considering that the nodule formation in the liver is ML1 dose and time dependent, and that the fibrosis is a dynamic and reversible process, a screen was performed to determine the optimal conditions to observe the relationship between liver fibrosis and tumor growth. Different ML1 doses and time schedules for the comparison between the ML1 and the ML1 fibrosis coexisting group were performed in this study. The animals were raised and cared for according to the guidelines set up by the National Science Council, ROC. The mouse experiments were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee.

Liver fibrosis induction enhances hepatoma cell growth. Intra-spleen inoculation of ML-1 established tumor nodule formation in the liver of BALB/c mice. TAA was used to induce fibrosis. The protocol of dose and timing was as indicated. (a) TAA injection after ML-1 implantation represents fibrosis induction after tumor growth (ML1–TAA). (b) TAA injection before ML1 implantation represents tumor growth after fibrosis (TAA–ML1). (c) TAA continuing treatment is the combination of the two above (TAA–ML1–TAA). Each group contains at least five mice, three of each experiment were repeated with similar results. (d) The representative hepatoma tumor nodules for model A in ML1-bearing mice (ML1) or ML-1 growth in fibrotic liver (ML1–TAA).

Picrosirius Red Staining

Liver fibrosis status was evaluated by picrosirius red staining.9 Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were stained by 1% Sirius red (Sigma-Aldrich, France) dissolved in saturated picric acid for 90 min at room temperature. Sections were washed twice with 0.5% acetic acid, and then dipped in 70% alcohol for 5 min followed by 5 min in xylene. The slides were mounted and observed by microscope.

Intrahepatic Leukocyte Population Analysis

Mice livers were perfused with 10 ml PBS and 10 ml HBSS containing 0.01% collagenase type IV and 0.001% DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich), then whole livers were harvested and digested in HBSS containing 2% FBS, 0.01% collagenase type IV and 0.001% DNase I at 37°C for 30 min. Single cell suspensions were prepared by passing the liver extract through a mesh. After removing hepatocytes by centrifuging at 300 r.p.m. for 3 min, the leukocytes were then isolated subsequent to a further centrifuge in 30% opti-prep (Sigma-Aldrich) at 2500 r.p.m. for 20 min. The cells in the interface were collected and further stained with CD3-FITC, CD19-PE, CD4-FITC, CD8-PE, panNK-PE and F4/80-FITC (eBioscience, USA). Treg cells were determined by intracellular staining of Foxp3-FITC with the Foxp3 Staining Set (eBioscience). Each population of leukocytes was determined by FACS Calibur (Beckton Dickinson).

Immunofluorescent Staining of Tumor-Infiltrating CD4+, CD8+ Cells and Foxp3+ T Cells

Frozen liver tissues were cut into 5 μm sections, fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 1 min, and for 3 min in ice-cold acetone, and then washed in PBS. Tissues were incubated with anti-CD4, anti-CD8 (Becton, Dickinson and Company, USA) or anti-Foxp3 (Abcam, UK) at 4°C overnight, and subsequently incubated with either goat anti-rat-conjugate Alexa Fluor 488 (Life Technology, USA) or goat anti-rabbit-conjugate Alexa Fluor 594 at room temperature for 1 h. The slides were further stained with DAPI for 15 min to show the tumor nodule position. Three fields containing tumor were randomly selected from each liver section. Each group contained four to five mice. Tumor infiltrated CD4+ or CD8+ T-cell numbers were then calculated. The indicating tumor area was counted after image capture. One tumor area unit is equal to 0.19 mm2.

CD4 and CD8 T-Cell Depletion

Anti-CD4 antibody (clone GK-1.5) or anti-CD8 antibody (clone 2.43) were injected intraperitoneally at 1 mg per mouse every 7 days throughout the entire treatment period. The depletion efficacy was evaluated by determination of the blood lymphocyte population by flow cytometry, and it was found that more than 95% of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were depleted by anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibody, respectively.

Intrahepatic Cytokine Expression

Liver tissues harvested from mice were suspended in PBS and homogenized into a 100 mg/ml concentration. The cell lysates were centrifuged at 8000 r.p.m. for 15 min. The supernatants were then used to detect IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-6 expression by ELISA kits (R&D Systems, USA). The chemokine expression status was evaluated by TransSignal Mouse Cytokine Antibody Array 1.0 (Panomics, USA). All procedures followed the manufacturers’ instructions.

RESULTS

Fibrosis Induction Enhances Hepatoma Cell Growth in the Liver

Using a liver fibrosis model induced by TAA, we evaluated the growth of hepatoma cells in the fibrotic liver. ML-1 hepatoma cells were implanted by intra-spleen injection, then treated with TAA for 4 weeks to induce fibrosis, and the nodule formation of the metastatic hepatoma cells in the liver were measured. As shown in Figure 1a, greater numbers of tumor nodule were present in TAA-treated liver than in the non-treated control. The tumor nodule sizes (>4 mm, 1–4 mm) were larger in the TAA-treated group. The timing of TAA treatment was further changed. TAA was given for 6 weeks to induce fibrosis beforehand, and the ML-1 hepatoma cells were then implanted. Although the difference between experimental and control groups is low, the number of tumor nodules in the TAA-pretreated mice was still significantly higher than that seen in the control group (Figure 1b). When TAA is continuingly administered, the numbers of tumor nodules in the liver were significantly enhanced in TAA-treated mice compared with the non-treated control (Figure 1c). A representative tumor nodule of hepatoma or hepatoma with fibrosis is shown in Figure 1d. When the hepatoma overgrows, the mice will die in 8–10 weeks after tumor implantation. The tumor-bearing mice with fibrosis died 1–2 weeks earlier than non-fibrotic ones in all three treatment protocols (Figure 2). The ML-1 hepatoma grows in the liver and the original injection site of the spleen. At the very late stage, some ML-1 cells are found in the intestine. The collagen stain with Picrosirius red for fibrotic liver is shown in Figure 3. Most of the collagen was deposited along the blood vessel of the liver after TAA treatment. In addition, tumor growth also increased collagen deposition within the tumor mass. The growth of ML1 in the liver is dose and time dependent with a predictable manner, and three protocols with different initial inoculums of ML1 cells or TAA treatment are shown for the evaluation of the interaction of fibrosis with hepatoma growth. We conclude that TAA-induced fibrosis enhances hepatoma cell growth in fibrotic liver and also increases the mortality for hepatoma-bearing mice.

Fibrosis induction enhances the mortality of hepatoma-bearing mice. Intra-spleen inoculation of ML-1 established tumor nodule formation in the liver of BALB/c mice. TAA was used to induce fibrosis. The protocol was the same as the experimental procedure shown in Figure 1a–c. The survival of the tumor-bearing mice was shorter in TAA-treated groups than control (n=9). P<0.05 by log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test.

Picrosirius red staining of fibrotic liver. Intra-spleen inoculation of ML-1 established tumor nodule formation in the liver of BALB/c mice. TAA was used to induce fibrosis. Paraffin-embedded liver tissue sections were stained in 1% Sirius red, collagen-positive sites were indicated in red. (a–c) Showed collagen expression in ML1–TAA treatment group, whereas d–f showed the results of TAA–ML1 treatment group, and g–i showed TAA–ML1–TAA-treated group. Black arrow indicates fibrosis region, arrow head indicates tumor part.

Fibrosis Induction Downregulates the Immune Response to Hepatoma

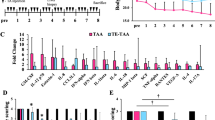

The mechanism of enhanced hepatoma growth in fibrotic liver was investigated. First, the levels of cytokine and chemokines were compared among four groups of treatment: naïve, TAA-induced fibrosis, ML-1 hepatoma and ML-1 hepatoma with fibrosis. A cytokine/chemokine array was used to detect the cytokine and chemokine profile in the liver extract. Cytokines/chemokines, such as G-CSF, M-CSF, GM-SCF, MIG, MIP-1α, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IP10, RANTES, VEGF, IL-1α, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, are present in the liver of naïve mice. There are lower expressions of some cytokines/chemokines in the three experimental groups compared with the naïve mice, particularly in the hepatoma with fibrosis group (Supplementary Figure 1). As the cytokine/chemokine array is a qualitative assay and the detection time was at the final stage of killing, we chose three cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-6) for further quantitation post tumor implantation. Naive mice have high levels of IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-6. More cytokines are found in the ML1 hepatoma group, whereas the fibrosis and ML1 hepatoma combined group has the lowest cytokine level (Figure 4). As the cytokines are measured in digested tissue lysates, their physiological function is not clear without direct staining in the tumor mass. We further analyzed the infiltrating lymphocytes in the liver. The intrahepatic leukocytes from the liver of various treated groups were isolated, stained with antibody, and determined by flow cytometry. Although the percentage of the T or B cells is increased in ML1 hepatoma-bearing liver, but downregulated after fibrosis induction (Supplementary Figure 2), there is no significant difference between different groups due to the high experimental variation. We further analyzed the tumor-infiltrating T cells by immunofluorescent staining. The CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were stained with anti-CD4 or anti-CD8-FITC-conjugated antibody on the tumor section that had a higher density of DAPI staining, and the number of the intratumor T cells was quantitated under a microscope (Figure 5a). Both CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells infiltrating into the tumors are fewer in TAA-treated mice than in non-treated ones (Figure 5b). This inhibition pattern was also observed in the TAA-continuing treatment group (Figure 5f). Although the CD4+ T infiltration is lower in the TAA-pretreatment group than in the control, it has not reached a significant level (Figure 5d). The analysis was performed at the killing time point of the protocol in Figure 1, and we further determined the kinetic changes of the CD4+ or CD8+ tumor-infiltrating T cells. Using Figure 1c protocol, the time point of 3 weeks is also 1 week after tumor implantation. At tumor early growth (1 week), many CD4+ or CD8+ T cells infiltrate into the tumor mass. But a dramatic decrease of the tumor-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells occurs from week 3 to week 4, equivalent to between week 1 to week 2 after tumor implantation (Figure 5g). At a later time (>week 6), a significantly lower number of infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are found in the fibrotic group than in non-fibrotic one, which is consistent with the result of Figure 5f. Fibrosis induction thus further downregulates the tumor-infiltrating T cells.

Cytokine expression status in the liver of fibrotic or fibrotic combined tumor mice. Liver tissues were harvested at 1–4 weeks after tumor implantation. Digested tissue lysates were used to evaluate IFN-γ, IL-6 and IL-4 expression level by ELISA. Each group contains at least three mice, and each experiment was repeated once with similar results.

Fibrosis induction inhibits CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell infiltration into tumor. Intra-spleen inoculation of ML-1 established tumor nodule formation in the liver of BALB/c mice. TAA was used to induce fibrosis. CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were stained in frozen tissue section, shown in green. DAPI (blue) were used to stain the nuclei, the condensed nodule marked by white dotted line is the tumor part. Images are representative of 4–5 mice in each group. Magnification was 400-fold. The number of tumor infiltrated CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were counted as described in Materials and Methods section. One tumor area unit is equal to 0.19 mm2. (a, b) ML1–TAA treatment. (c, d) TAA–ML1 treatment. (e, f) TAA–ML1–TAA treatment. (g) The tumor-infiltrating CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were counted at different time points in TAA–ML1–TAA-treated mice.

Treg Cells in Tumor-Bearing Fibrotic Mice

Whether downregulation of tumor-infiltrating T cells involves the Treg cells was investigated. First, the CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were depleted by anti-CD4 antibody or anti-CD8 antibody, respectively, to observe its effects. As stated above, fibrosis enhanced the ML1 tumor growth in TAA-treated mice. Depletion of CD4+ T cells greatly diminished the numbers of tumor nodules in TAA-treated mice (Figure 6a). In the TAA-non-treated mice, the numbers of tumor nodules were also decreased after CD4+ T-cell depletion, but to a lesser degree. In contrast, depletion of the CD8+ T cells slightly enhanced the hepatoma cell growth, indicating that CD8+ T cells might be the antitumor effector cells (Figure 6b). On checking whether depletion of CD4+ T cells, including the CD4+ Treg, would enhance the antitumor activity of CD8+ T cells infiltrating into the tumor mass, we found that the CD8+ T-cell infiltrations into tumor mass were indeed enhanced. Fibrosis would inhibit the CD8+ T-cell infiltration in the tumor, but after depletion of CD4+ T cells, the tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells in the fibrotic liver were also increased. (Figure 6c). The Treg cells were further characterized by Foxp3 staining of CD3+ T cells. The flow cytometric analysis of intrahepatic Foxp3+CD3+ T cells is shown in Supplementary Figure 3. TAA treatment alone can enhance the development of the intrahepatic Foxp3+ CD3+ T cells. ML1 hepatoma growth by itself also favored the increase of the intrahepatic Foxp3+ CD3+ T cells (Figure 6d). The induction of Treg cells in the liver is observed for all three protocols. We further stained the Foxp3+ CD3+ T cells in the liver. TAA treatment induced Foxp3+ CD3+ T cells in the fibrotic part (data now shown). The ML1 tumor growth-induced Foxp3+ CD3+ T cells were primarily located in the tumor mass. When the fibrosis and hepatoma growth were combined, more Foxp3+ CD3+ T cells were found in the tumor mass (Figure 6e and f). This suggests that Treg cells participate in the antitumor activity during tumor growth, and TAA-induced fibrosis enhances this induction.

Regulatory T cells in the liver of fibrotic or fibrotic combined with tumor mice. Intra-spleen inoculation of ML-1 established tumor nodule formation in the liver of BALB/c mice. TAA was used to induce fibrosis. CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were depleted by intraperitoneal injection of anti-CD4 antibody (clone GK 1.5) or anti-CD8 antibody (clone 2.43) every 7 days from 1 week before ML1 implantation. (a) Tumor nodule formation in CD4+ T-depleted mice. (b) Tumor nodule formation in CD8+ T-depleted mice. (c) Tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells in normal or CD4+ T-cell depleted mice. (d) The percentages of Foxp3+/CD3+ T cells in intrahepatic leukocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry. The cells isolated from fibrosis combined with hepatoma-treated mice were stained with anti-CD3 and anti-Foxp3. (e) Immunofluroscence staining of Foxp3+ (red), CD3+ (green) and DAPI (blue) in mice liver. The DAPI condensed parts are considered as tumor area (white dotted line). The images are representative of six mice in each group. (f) Shows the quantitative result in e.

DISCUSSION

Liver cirrhosis and HCC have been the two major causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide, but how tumor cells interact with the fibrotic environment to expedite the tumor progression is not clearly illustrated. In this study, we used a liver fibrosis model, created by TAA induction, to evaluate the growth of the transplanted hepatoma in the fibrotic liver. We demonstrate that a fibrotic environment would promote the growth of the implanted tumor cells. The survival time of the hepatoma-bearing mice was also shortened after fibrosis induction. TAA-induced fibrosis can enhance the tumor cell growth by downregulating the antitumor immunity. The cytokine/chemokine production, hepatic-infiltrating lymphocytes or more specifically the tumor-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are downregulated during fibrotic induction. The CD3+ Treg cells were primarily involved in the inhibition of the antitumor immune responses in fibrosis.

Many differences between normal and fibrotic livers may affect hepatic homing, cellular growth or angiogenesis to influence the antitumor immunities. A complex interaction or cross-regulation between the hepatoma microenvironment and immune surveillance exists. That fibrosis can enhance the orthotopic hepatoma growth in a fibrotic liver has been reported by Kuriyama et al10 and Kornek et al.11 Hepatoma cells grow faster and invade a tumor mass after implantation into the liver, and a comparison of the intratumor factors that favor the tumor cell growth or invasion in either a normal or fibrotic liver reveal that the increases of proangiogenic and prometastatic factors are found to accelerate the hepatoma growth. However, the immune surveillance was not evaluated in the liver. We chose an in situ hepatoma model to study the interaction between fibrosis induction and individual nodules of hepatoma cell growth. In this model, the direct effect of TAA on ML1 cell migration or proliferation, as well as on lymphocyte cytotoxicity and activation are minimum (Supplementary Figure 4). Our previous study showed that CD8+ T cells are the effector cells to kill the ML1 tumor nodule after Con A injection.8 To perform a comprehensive analysis of the interaction between fibrosis and hepatoma growth, three conditions are compared: fibrosis induction after (ML1–TAA), before (TAA–ML1) or continuously with (TAA–ML1–TAA) tumor implantation, as outlined in the protocol of Figure 1. The tumor nodule formation in the liver is ML1 dose and time dependent with a predictable manner. For a better comparison of tumor growth in the fibrotic liver, a prescreen was performed to find optimal dose and time in our model. All three systems show that fibrosis induction enhances the hepatoma cell growth. Among these, the protocol B of fibrosis before tumor implantation is least effective, with only a small difference of tumor nodule being found (Figure 2b), whereas the CD4+ or CD8+ T infiltration is not significantly inhibited in the TAA-pretreatment group compared with the control (Figure 5d). A higher inoculum dose of tumor cells was used for protocol B than for A or C, and it became more difficult for T cells to inhibit a high tumor cell mass. The second possibility is that with no continuing injection of TAA in protocol B, the suppressive function of Treg is not continuingly induced or sustained, and therefore, no significant inhibition occurs of the CD4 and CD8 T cells’ infiltration into the tumor nodule on the TAA–ML1 group. Fibrosis per se is not enough to downregulate the T-cell infiltration into the tumor mass. Fibrosis induction has a more significant role in the downregulation of the antitumor immunities. During the TAA-caused hepatocyte damage, Treg cells will be more likely to inhibit the hepatic inflammation. There are additive effects of fibrosis and ML1-induced Treg activities to downregulate the antitumor immunities.

Chen et al12 reported that more T, B and NK cells are present in the livers of HCC patients than those of liver cirrhosis or healthy controls, and that the numbers decreased along with the stage or progression of the HCC, so that the antitumor activity was apparently downregulated along with cirrhosis and tumor progression.12 In this study, the tumor-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells decreased along with the development of fibrosis induction, so the antitumor activity was therefore downregulated, and hepatoma cells overgrew in a fibrotic environment. Several possibilities exist. First, some of the extracellular matrix may modulate the immune responses. A collagen receptor, the inhibitory leukocyte-associated Ig-like receptor-1 might inhibit the cytotoxic activity of CD8+ T cells, the cytokine-mediated signal, the differentiation of blood precursor toward DC and induce apoptosis.13 This is expressed on cells of the immune system including T, B, NK, monocytes and DC that interact with the hydroxyproline of collagen. Hyaluronan could also induce activated T cells to undergo cell death.14 As tumor cells and/or tumor stroma in the fibrotic tissue produce extracellular matrix and trans-membrane collagens, it might downregulate the response against tumors by effector cells such as CD8+ T cells. Second, the imbalance of Th1/Th2 cytokines may affect immune response against the tumor. In the fibrotic liver environment, the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ suppresses the collagen synthesis by fibroblasts, whereas Th2 cytokines IL4, IL-5 and IL-13 enhance collagen deposition. IL-13 is the main profibrotic mediator, as it can cooperate with TGF-β to promote the collagen deposition by fibroblasts.5, 15, 16 TAA causes hepatocyte damage, which leads to inflammation and activation of hepatic stellate cells to secrete fibrillar collagens, culminating in the development of fibrosis and ultimately cirrhosis. The inflammation-associated fibrosis is a reversible process, as it will spontaneously resolve after removal of injury, and remodeling of fibrillar collagens can occur when the balance of matrix metalloproteinase and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase favor the degradation of the extracellular matrix. Several factors such as IL-10, IL-23Rα2 (decoy receptor of IL-23) or Treg are known as endogenous inhibitors of tissue fibrosis. But during the continuing development of fibrosis, the bias Th2 response will inhibit the generation of the antitumor CD8+ T-cell activity. Third, the hepatic cytokines might be modulated in the fibrotic liver. HCC were reported to associate with selective cytokines.17 Both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines are detected in HCC tumors. In our in situ hepatoma model, the implanted hepatoma will stimulate the production of cytokines as the IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-4 or chemokines were highest in the hepatoma group. The TAA fibrosis induction will deposit the collagen of extracellular matrix protein along the blood vessel and downregulate the cytokine/chemokine production. Moreover, the intrahepatic lymphocytes or tumor-infiltrating T cells were also decreased.

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes represent the immune response to a tumor that are composed of the CD8+ cytotoxic T cells as positive responders and the Treg as negative immunosuppressor. Kobayashi et al18 reported that the prevalence of Treg in HCC was significantly higher than that in the non-tumor part. The patient's CD8+ T cells infiltrating tumors is associated with a good prognosis, but a high prevalence of Treg-infiltrating HCC seems to be an indicator of a poor prognosis.18 Marquez et al19 reported that CD4+CD25+ Treg was increased in cirrhosis patients.19 The CD4+CD25+ T cells have been shown to suppress antitumor immunity, as depletion of CD4 T cells by anti-CD4 antibody enhanced the tumor immunosurveillance that is mediated by tumor-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cells.20, 21, 22 HCC cell culture supernatant was reported to contain substances that can prompt expansion of Treg and enhance their suppressive function.23 The activated hepatic stellate cells in the fibrotic environment can preferentially expand Treg cells, which may further affect antitumor immunity.24 Moreover, TGF-β is abundant in the sinusoidal endothelial cells, Kupffer cells, stellate cells and hepatocytes in the liver.25 TGF-β has an important and pleiotropic role in angiogenesis, fibrosis and cancer. The effect of TGF-β is context dependent, as it will promote Foxp3 expression and induce the Treg differentiation, in the presence of IL-6, it will instead induce the differentiation of Th17 cells.26, 27 In this fibrosis and tumor model, the Foxp3+CD3+ T cells were demonstrated in the fibrotic part as well as the tumor part, and the additive or synergistic effect of fibrosis and tumor growth on the enhancement of Treg development will inhibit the infiltration of CD8+ T cells into the tumor mass. The depletion of CD4+ Treg by anti-CD4 antibody increases the tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells, and inhibit tumor nodule formation in the liver.

Tumors are rigid because they have a stiff stroma and elevated Rho-dependent cytoskeletal tension that drives focal adhesions. Matrix rigidity will regulate growth, morphogenesis and intergrin adhesions of tumor cells.28 Both exogenous force from the extracellular matrix and transformed cells with focal adhesion assembly through ERK- and Rho-dependent cytoskeletal contractility will regulate the cell and tissue phenotype. Conditions that induce tissue fibrosis (matrix stiffening) and oncogene activation of enhanced ERK will facilitate malignant transformation. Although we have not determined the elastic modulus (Pa) for the stiffness of the fibrotic tissue, as well as for the tumor part of a non-fibrotic liver and the tumor in the fibrotic liver, the possibility of better tumor cell growth in the fibrotic ‘stiff’ lesions is not excluded.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Laboratory Investigation website (http://www.laboratoryinvestigation.org)

References

Parkin DM . Global cancer statistics in the year 2000. Lancet Oncol 2001;2:533–543.

Brechot C, Gozuacik D, Murakami Y, et al. Molecular bases for the development of hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Semin Cancer Biol 2000;10:211–231.

Arbuthnot P, Kew M . Hepatitis B virus and hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Exp Pathol 2001;82:77–100.

El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL . Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology 2007;132:2557–2576.

Wynn TA . Fibrotic disease and the T(H)1/T(H)2 paradigm. Nat Rev Immunol 2004;4:583–594.

Iredale JP . Models of liver fibrosis: exploring the dynamic nature of inflammation and repair in a solid organ. J Clin Invest 2007;117:539–548.

Ikejima K, Honda H, Yoshikawa M, et al. Leptin augments inflammatory and profibrogenic responses in the murine liver induced by hepatotoxic chemicals. Hepatology 2001;34:288–297.

Chang CP, Yang MC, Liu HS, et al. Concanavalin A induces autophagy in hepatoma cells and has a therapeutic effect in a murine in situ hepatoma model. Hepatology 2007;45:286–296.

Junqueira LC, Bignolas G, Brentani RR . Picrosirius staining plus polarization microscopy, a specific method for collagen detection in tissue sections. Histochem J 1979;11:447–455.

Kuriyama S, Yamazaki M, Mitoro A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in an orthotopic mouse model metastasizes intrahepatically in cirrhotic but not in normal liver. Int J Cancer 1999;80:471–476.

Kornek M, Raskopf E, Tolba R, et al. Accelerated orthotopic hepatocellular carcinomas growth is linked to increased expression of pro-angiogenic and prometastatic factors in murine liver fibrosis. Liver Int 2008;28:509–518.

Chen G, Luo DZ, Liu L, et al. Hepatic local micro-environmental immune status in hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhotic tissues. West Indian Med J 2006;55:403–408.

Meyaard L . The inhibitory collagen receptor LAIR-1 (CD305). J Leukoc Biol 2008;83:799–803.

Ruffell B, Johnson P . Hyaluronan induces cell death in activated T cells through CD44. J Immunol 2008;181:7044–7054.

de Visser KE, Eichten A, Coussens LM . Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer 2006;6:24–37.

Henderson NC, Iredale JP . Liver fibrosis: cellular mechanisms of progression and resolution. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007;112:265–280.

Budhu A, Wang XW . The role of cytokines in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Leukoc Biol 2006;80:1197–1213.

Kobayashi N, Hiraoka N, Yamagami W, et al. FOXP3+ regulatory T cells affect the development and progression of hepatocarcinogenesis. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:902–911.

Marquez M, Fernandez-Gutierrez C, Montes-de-Oca M, et al. Chronic antigenic stimuli as a possible explanation for the immunodepression caused by liver cirrhosis. Clin Exp Immunol 2009;158:219–229.

Terabe M, Berzofsky JA . Immunoregulatory T cells in tumor immunity. Curr Opin Immunol 2004;16:157–162.

Ormandy LA, Hillemann T, Wedemeyer H, et al. Increased populations of regulatory T cells in peripheral blood of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2005;65:2457–2464.

Unitt E, Rushbrook SM, Marshall A, et al. Compromised lymphocytes infiltrate hepatocellular carcinoma: the role of T-regulatory cells. Hepatology 2005;41:722–730.

Cao M, Cabrera R, Xu Y, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma cell supernatants increase expansion and function of CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells. Lab Invest 2007;87:582–590.

Jiang G, Yang HR, Wang L, et al. Hepatic stellate cells preferentially expand allogeneic CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in an IL-2-dependent manner. Transplantation 2008;86:1492–1502.

Bissell DM, Wang SS, Jarnagin WR, et al. Cell-specific expression of transforming growth factor-beta in rat liver. Evidence for autocrine regulation of hepatocyte proliferation. J Clin Invest 1995;96:447–455.

Prud’homme GJ . Pathobiology of transforming growth factor beta in cancer, fibrosis and immunologic disease, and therapeutic considerations. Lab Invest 2007;87:1077–1091.

Liu Y, Zhang P, Li J, et al. A critical function for TGF-beta signaling in the development of natural CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol 2008;9:632–640.

Paszek MJ, Zahir N, Johnson KR, et al. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell 2005;8:241–254.

Acknowledgements

Ming-Chen Yang is partly supported by grants from Liver Disease Prevention and Treatment Research Foundation. This work was supported by Grants NSC91-2320-B006-036 and NSC94-3112-B006-005 from the National Science Council, Taiwan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, MC., Chang, CP. & Lei, HY. Induction of liver fibrosis in a murine hepatoma model by thioacetamide is associated with enhanced tumor growth and suppressed antitumor immunity. Lab Invest 90, 1782–1793 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.2010.139

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.2010.139