Abstract

The integration of gamification into museum experiences has emerged as a promising approach for cultural heritage communication, yet tensions persist between maintaining professional content integrity and creating engaging visitor experiences. This study explores how to construct an effective museum gamification communication paradigm through embodied cognition theory. Using grounded theory methodology to analyze semi-structured interviews with 23 participants of the “Canal Mystery” exhibition, we identified eight key factors across four dimensions: experience foundation and experience mapping (mapping dimension); sensory, functional, and interactive experience (perception dimension); scene and social experience (situational dimension); and emotional identification (meaning construction dimension). Our theoretical model demonstrates how these factors collectively influence communication effectiveness. Findings reveal that successful museum gamification depends on activating audiences’ bodily experiences, creating multi-sensory environments, facilitating contextualized understanding, and fostering emotional connections. This research provides a systematic framework for museums to balance professional integrity with engaging experiences in cultural heritage communication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cultural heritage is the living cultural memory of nations and peoples, a unique and valuable legacy with important information dissemination value. Kenneth Hudson, in his masterpiece A Social History of Museums: What the Visitors Thought (1975), clearly stated that museums should not only collect and preserve tangible and intangible culture, but also disseminate knowledge in an engaging way1. UNESCO has consistently reaffirmed over the past 50 years that ensuring the effective dissemination of information about cultural heritage is an essential foundation for achieving heritage conservation2. As an important public cultural service and information dissemination subject, museums implement the people-centered development concept through information dissemination to fulfill their social responsibilities3. In the era of deep integration of digital technology and media, the ways of preserving, visiting, experiencing, and consuming culture have become more diversified4. In this process, the audience not only shows stronger initiative and higher emotional needs, but also presents characteristics of distraction. For museums, under the requirements of enhancing the effect of information dissemination and the organizational mission and working principle of “people-oriented,” “games” focusing on human needs and fun experiences have become an unavoidable focus of attention. With the development of digital technology, gamification, as an emerging technology that applies game elements and game mechanics to non-game contexts5, has sparked a global wave of practice and research due to its advantages of high attractiveness and engagement. In 2012, the New Media Consortium Horizon Report indicated that game-based learning would become popular, and in 2013, the report formally added the term gamification and listed it as an emerging technology6,7. From educational innovation8,9, to marketing10, to organizational management11,12, to financial services13, to civic engagement14, gamification has demonstrated its powerful empowering value. Gamification offers new possibilities for cultural heritage information dissemination by stimulating audience curiosity about the unknown and improving the visiting and learning experience.

Currently, the practice of gamification information dissemination in museums mainly focuses on three aspects: first, building immersive display environments with the help of VR/AR and other technologies, to enhance the interaction between the audience and the collection as well as the experience of the cultural scene15,16,17; second, reconstructing the content of the exhibitions through gamification narratives, which play an active role in explaining complex knowledge, expanding the visiting experience and deepening cultural learning18,19; third, through the design of multiple interactive mechanisms, it stimulates users’ curiosity about the unknown and promotes in-depth dialogues between audiences and cultural heritage20,21. These gamification practices not only deepen the audience’s understanding of the value of cultural heritage, but also cultivate the audience’s sense of active participation and promote their transformation from cultural observers to cultural interactors and producers. Therefore, gamification has become an important way for the innovative development of cultural heritage information dissemination, both from the perspective of the expansion of the museum’s collection protection and educational functions, as well as from the perspective of the audience’s needs for cultural experience. Nevertheless, the combination of museums and gamification is still questioned due to concerns about excessive pandering to the audience and the hollowing out of cultural content, and the industry also maintains a cautious, wait-and-see attitude towards gamification22. There is an inherent contradiction between the professionalism and seriousness of cultural heritage information and the fast-paced, entertainment-oriented experience of gamification. The entertainment tendency of gamification may distract the audience from the content of the exhibition, a situation that not only affects the effectiveness of cultural heritage information dissemination, but also deviates from the nature of information dissemination and the original purpose of cultural heritage dissemination23. A deeper problem is that existing studies have focused too much on empirical summaries and lacked theoretical reflections, especially failing to examine in depth the organizational implications of gamification and its related concepts for museums, and failing to adequately elucidate their roles in reconfiguring museum information dissemination modes. Therefore, this study raises two core questions: how to build a museum gamification communication paradigm that is adapted to the characteristics of cultural heritage? How to ensure the effectiveness of communication while taking into account the public experience?

Embodied cognition theory provides a research entry point for addressing the above questions. This theory posits that cognitive processes are not only controlled by the brain, but are also closely related to physical interactions between the body and the environment. In this perspective, the body is not only the carrier of cognition, but also the subject of cognition; perception and understanding are not isolated information processing, but are jointly shaped by embodied experiences and situational factors. This theoretical framework is highly compatible with the immersive experience and multi-sensory interaction pursued by museum gamification24. At the same time, this theory provides a scientific basis for understanding the cognitive processes and learning experiences of audiences in gamified display environments.

The proposition of embodied cognition theory originated from reflections on traditional computational cognitive science. Mainstream cognitive science has long been influenced by René Descartes’ mind-body distinction, which separated thinking from the body and reduced cognition to abstract symbolic operations and information processing. Embodied cognition theory emphasizes that cognitive processes deeply depend on bodily experiences, sensory interactions, and situational factors, arguing that thinking is not only “in the brain” but emerges from dynamic interactions between the body and the environment25. In the 1960s, modern European philosophers such as phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty and existentialist philosopher Martin Heidegger represented an important intellectual movement that laid the philosophical foundation for embodied cognition. Maurice Merleau-Ponty proposed perceptual phenomenology, emphasizing the central position of the body in cognition and revealing the unity and embodiment of perception and action26; Martin Heidegger used the concepts of “Dasein” and “being-in-the-world” to emphasize that the body obtains cognition through interaction with the world, blurring the subject-object boundary27. These ideas collectively questioned the separation of mind and body, highlighted the fundamental position of the body in cognition, and emphasized the dynamic unity of subject and object, body and environment. Based on this, phenomenologist Don Ihde summarized and reflected on various theories related to embodiment, developing the important theoretical framework of the phenomenology of technology. He revealed that technology is not merely an external tool but also a mediating structure that shapes human experience and cognition. Ihde precisely categorized human-technology relationships into four phenomenological modes: embodiment relation, in which technology becomes a seamless extension of bodily perception; hermeneutic relation, where technology serves as a representational system requiring interpretation; alterity relation, where technology appears as a quasi-human interactive object; and background relation, where technology is integrated into the environment as an implicit perceptual background28. Notably, in embodiment relations, technological tools exhibit “quasi-transparency,” meaning they are experienced as part of the body schema during skilled use rather than as external objects29. This phenomenological understanding of technology’s integration with the body provided important theoretical support for subsequent communication studies exploring embodied interactions between humans and media.

With the rise of the embodied cognition paradigm, the field of communication studies also began to reflect on its theoretical foundations, gradually developing the new concept of embodied communication in an attempt to transcend the tendency to ignore the role of the body in traditional communication models. Traditional communication theory, influenced by Western philosophical traditions, viewed communication as an alignment of thoughts and consciousness, emphasizing consciousness while downplaying the intangible communication characteristics of materiality, while viewing the body as an obstacle to information transmission, a theoretical orientation termed “disembodied” that overlooked the importance of the body in the communication process30. The development of digital technology has given rise to new forms of communication, among which gamification is an emerging technology that applies game elements to non-game contexts6,7. Through its interactivity and immersive experience, gamification has profoundly changed traditional communication models. Unlike traditional media, gamification emphasizes audience bodily participation, requiring audiences to no longer be passive recipients of information, but rather to construct meaning through bodily perception and interaction. By reducing the gap between media and body, gamification increases the transparency of the communication process, enabling audiences to receive and process information in a more direct manner. This communication approach that emphasizes bodily participation transcends the limitations of one-way information transmission, challenges traditional disembodied cognition, and forms a new embodied communication paradigm31. However, dialectically speaking, many scholars have also pointed out that excessive reliance on digital technology may lead to sacrificing communication depth and authenticity for efficiency, ignoring the role of the body in this communication process32. Particularly in cultural heritage exhibition, overemphasis on technological interaction may weaken the physical experience of artifacts, thereby distracting the audience’s attention from the artifacts themselves33. Whether from positive or critical perspectives, it is undeniable that with the introduction of embodied cognition theory into communication studies, more scholars have begun to recognize the importance of the body in information communication.

Contemporary museum communication is evolving toward a people-centered approach, emphasizing public deep participation and creativity. This trend echoes embodied communication theory, providing a new perspective for understanding museum gamification communication. Based on embodied communication theory, embodied experience further focuses on how bodily participation shapes people’s perception and understanding34. In the context of digital technology, embodied experience has become an important analytical framework for explaining and understanding audience visiting behavior35. The effectiveness of museum information communication directly depends on the innovation of experiential forms. Experience, as the way people interact with cultural content, continuously evolves with changes in communication methods. The transformation of communication methods has gradually shifted experience from its initial “body-dependent” state to the “body-independent” state in modern society. In this process, direct bodily participation has been replaced by institutionalized viewing norms, with experience confined to the single dimension of visual perception36. Now, the rise of digital technology, particularly gamification, is prompting a resurgence of the body in the experiential process. Experience is no longer limited to the static process of viewing with the eyes, but has transformed into dynamic interaction involving multi-sensory coordination and virtual-real integration37. Current academic research on embodied experience mainly focuses on four aspects: mapping-level research focuses on the foundational role of prior bodily experiences in cognitive formation, exploring how connections with existing experiences facilitate new knowledge construction and understanding38,39; technology-level studies examine how digital technologies such as virtual reality evolve from bodily extensions to mediums for constructing embodied experiences40,41; situational-level research focuses on how environmental factors influence bodily perception and cognitive processes42,43, with studies showing that there exists a dynamic interactive relationship between situation and body, which not only affects direct perception but also shapes broader cognitive processes44,45; experience-level research focuses on the key role of bodily participation in understanding cultural heritage and forming memories46,47, emphasizing how bodily interaction promotes emotional connections with artifacts and deepens the meaning of cultural experiences48,49. These research dimensions are closely related to the four-dimensional analytical framework we will propose, laying a solid foundation for the theoretical framework of this study.

Based on the above understanding, this study proposes a four-dimensional analytical framework of embodied cognition theory applicable to museum gamification cultural heritage communication research50. First, the Mapping Dimension emphasizes that the formation of new cognition is based on past bodily experiences. Cognitive scientist Andy Clark points out that embodied cognition has two core perspectives: cognitive development depends on experiences influenced by individual bodily states; and an individual’s sensorimotor skills are both externalized behaviors and shaped by internal factors such as biological, psychological, and cultural backgrounds51. This theoretical framework echoes research across various fields, showing that human thinking, understanding, and decision-making processes are deeply rooted in the experiential foundation formed by body-environment interactions52,53,54. When individuals face new information or situations, the brain automatically activates related bodily experience memories, understanding new content through analogy and mapping. Furthermore, research shows that when environmental stimuli match bodily experiences, relevant “cognitive potential” is activated - that is, physiological and psychological changes in bodily states that influence high-level cognitive processes. High-level cognition utilizes these cognitive potentials as mental shortcuts based on past experience, thereby transferring heavy mental labor to the body, thus reducing cognitive load55. Second, the Perception Dimension emphasizes that the body is the medium of cognition, and cognitive content is also provided by the body. Embodied cognition theory points out that cognitive processes are not merely mental activities but also involve the comprehensive participation of the body in the process of interacting with the environment56. Bodily states and specific cognitive behavioral patterns together form the foundation of information processing52. Many scholars have confirmed the important role of bodily factors through empirical studies. For example, research shows that changes in posture and facial expressions can affect people’s cognitive processes and emotional experiences57. Third, the Situational Dimension posits that cognition always occurs in specific environments, being a process where subjects construct new meanings by combining their current situation with existing knowledge58. Andy Clark, in his Extended Mind Theory, emphasizes that the environment not only provides a background for cognition but is also an active component of the cognitive system, forming a complex interactive system spanning brain, body, and environment59. Rodney Brooks’ “Intelligence-in-situ” further confirms the situatedness of cognitive activities, emphasizing that intelligent behavior arises from immediate interaction with the actual environment rather than internal abstract representations60. These theories collectively reveal that cognitive processes are not only subject to internal factors but also deeply influenced by the external environment. Finally, the Meaning Construction Dimension articulates the continuous dynamic interactive relationship between cognition, body, and environment. Cognition is not a static information processing mechanism, but rather a dynamically evolving process. This dynamic interaction reveals the essence of cognition: it is not confined to isolated operations within the brain, but is the product of continuous interaction between the body and environment. It forms a unified whole composed of multiple factors that interact with and mutually shape one another61.

In summary, this study selects embodied cognition theory as the analytical framework for the effectiveness of museum gamification cultural heritage information communication. The study collects primary data through interviews, uses grounded theory for coding62, and based on the mapping dimension, perception dimension, situational dimension, and meaning construction dimension, establishes a theoretical model of factors influencing the effectiveness of museum gamification cultural heritage information communication from the perspective of embodied cognition theory. The study aims to discover key factors affecting the museum gamification cultural heritage information communication process from an embodied cognition perspective, explore their roles and patterns in the communication process, achieve better cultural communication effects, and provide new approaches for cultural heritage information communication.

Methods

Research site

The China Grand Canal Museum’s “Imperial Inspector: “Canal Mystery” (hereafter referred to as “Canal Mystery”) project was selected as a case study for this research63. The museum is located in the Canal Sanwan Scenic Area in Ganjiang District, Yangzhou City, Jiangsu Province, and is one of the core exhibition sites of the Grand Canal Cultural Belt, which was inscribed on the World Heritage List in 201464. In July 2022, the museum launched the “Canal Mystery” program. The project adopts the “secret room escape”65 format popular among young people, and based on historical and cultural stories, it has created an original semi-fictional script, “Supervising the Water Division”, which creates an immersive space where plot clues are deduced by solving puzzles through a fascinating plot, and the audience can participate in the exhibition hall games according to the guidelines of the plot. The project won the “Star of Outstanding” award in 2023 from the UNESCO Global Awards for World Heritage Education Innovative Cases, which provides a typical case for researching the gamified information dissemination model of museums66.

Research design

This study adopts a qualitative research methodology, collecting data through semi-structured narrative interviews and analyzing it by applying grounded theory in order to explore in depth the effects of the museum’s gamified cultural heritage information dissemination model under embodied cognition theory.

In terms of data collection, considering the convenience of interviewees and the efficiency of interviews, we used online interviews as the main form, supplemented by face-to-face interviews, which took place from December 2024 to January 2025. To ensure the representativeness of the sample and the validity of the data, the research team released recruitment information through platforms such as Dianping, Xiaohongshu, TikTok, and Weibo, and used purposive sampling methods to screen interviewees67. The inclusion criteria required interviewees to have a basic knowledge of museum gamification, a strong willingness to learn about cultural heritage, and to have experienced the “Canal Mystery” exhibition in the past year. The exclusion criteria mainly considered the interviewees’ participation enthusiasm, expression ability, and whether their understanding of the interview topics, related concepts, and question meanings was accurate. These factors directly affect whether interviewees can provide in-depth and rich perspectives, thus ensuring the scientific validity of the experiment. Additionally, both inclusion and exclusion criteria were reviewed and approved by experts. The research team initially screened potential interviewees through the inclusion criteria, then communicated with these interviewees one week before the formal interview about their visiting experiences and interview matters to assess whether they met the exclusion criteria, thereby completing the secondary screening. Furthermore, to obtain diversified research perspectives, we invited interviewees of different age groups, educational backgrounds, and identities to participate in the study.

The design of the interview questions was based on the research objectives, drawing on the logical framework of established research and using a combination of leading and progressive questions62. To ensure the content validity of the interview outline, the research team conducted pre-testing, and optimized and adjusted the wording of the questions based on the feedback from the three pre-tested interviewees, and the interview outline is shown in Table 1. During the implementation of the interviews, we strictly followed the ethical norms of the research, and obtained informed consent from the interviewees for audio recording and transcribing, and all the data were encrypted for storage and used only for this study. The original interview materials were verified in both Chinese and English and confirmed by the interviewees68.

In terms of data analysis, this study used grounded theory to systematically analyze the interview data, identify relevant influencing factors, construct a mechanism model, and provide theoretical and practical guidance for subsequent research. Grounded theory, proposed by Glaser and Strauss, is a qualitative research method62. Grounded theory searches for core concepts and relationships between concepts that reflect social phenomena through coding, building substantive theory from the bottom up69. It centers on the logic of discovery rather than the logic of verification. Coding is divided into open coding, axial coding, and selective coding, which is the process of conceptualizing, categorizing, and theorizing raw data70. Compared with quantitative research methods, coding is more suitable for integrating and studying complex textual materials, and is often used to explore and refine research constructs and constituent dimensions, as well as to analyze influencing factors and their interrelationships71.The study first screened the original interview texts, extracted valid statements to form an initial database. Subsequently, through the three stages of open coding, axial coding, and selective coding, the key factors affecting the effectiveness of museum gamification information dissemination were explored in depth, ultimately constructing a theoretical model of factors influencing the effectiveness of museum gamification cultural heritage information dissemination based on embodied cognition theory. To ensure the reliability of the coding, the research team used triangulation, with researchers from different social backgrounds but all proficient in qualitative research methods coding separately, and invited an expert panel to review72. At the same time, we developed a strict coding manual, organized regular discussions among coders, and ensured the scientific validity and reliability of the research results through methods such as saturation testing and gender group difference analysis68.

Interview process

This study conducted interviews following qualitative research standards to ensure scientific validity in data collection. Before the formal interviews, the research team conducted preparatory communication with each respondent to assess their participation attitude, comprehension ability, and expression level to ensure interview quality. Based on the results of the preparatory communication, two candidate interviewees were excluded from the study due to misunderstanding of the interview topic.

During the interviews, the researcher gradually guided the interviewees to share their visiting experiences and feelings. In addition to the pre-set interview outline, the researcher would ask in-depth questions at appropriate times according to the interviewees’ answers in order to obtain more comprehensive and rich data. All interviewees maintained good participation throughout the interviews. The average interview length was 41 min, with the longest being 80.2 min and the shortest being 23.5 min, resulting in an interview text of approximately 216,431 words.

In terms of sample composition, this study included a total of 23 interviewees, with an age span from 10 to 60 years old, covering four age levels: children, youths, middle-aged individuals, and elderly individuals. Among them, 10 were males and 13 were females, with education levels primarily at bachelor’s degree or above, including 7 with master’s degrees or above and 10 with bachelor’s degrees. The interviewees were mainly composed of cultural heritage enthusiasts, game enthusiasts, technology enthusiasts, and related practitioners, a sample profile that basically matches the current audience structure of the China Grand Canal Museum73. The basic information of the interviewees is shown in Table 2.

Data analysis

During the open coding phase, the research team conducted a systematic qualitative analysis of the interview texts from the 23 interviewees. First, we carefully reviewed the original interview transcripts and, while respecting the interviewees’ genuine thoughts, deleted meaningless pauses, interjections, and clarified ambiguous expressions through secondary communication with the interviewees. This initial organization ensured textual clarity for subsequent analysis. In the secondary analysis, we further eliminated content that had low relevance to the audience experience or unclear meaning in expressions, thus obtaining more refined and effective textual materials. Through in-depth interpretation and meaning refinement of the original statements, we identified 38 conceptualization labels (A1-A38), which accurately reflect the core content of the interviewees’ expressions. (Supplementary contains a list of open code categories and original records) On this basis, through connotation analysis and category induction of adjacent initial concepts, we formed 16 initial categories (AA1-AA16), laying a solid foundation for subsequent in-depth analysis. The results of the open coding are shown in Table 3.

In the axial coding stage, the research team conducted higher-level concept refinement and category induction based on the 16 initial categories formed during open coding. Through systematic analysis of the relationships between initial categories, we extracted 8 core concepts: experience foundation, experience mapping, sensory experience, functional experience, interactive experience, scene experience, social experience, and emotional identification. These core concepts not only comprehensively reflect the multi-dimensional characteristics of museum gamification experience, but also form clear correspondences with the dimensions of embodied cognition theory. Among them, experience foundation and experience mapping correspond to the mapping dimension, sensory experience, functional experience, and interactive experience correspond to the perception dimension, scene experience and social experience correspond to the situational dimension, and emotional identification corresponds to the meaning construction dimension. These correspondences provide theoretical support for understanding the information dissemination mechanism in museum gamification.The results of the axial coded are shown in Table 4.

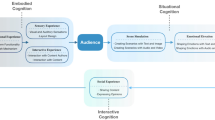

In the selective coding stage, based on the 8 core concepts identified, we deeply analyzed their functional pathways and relational structures, constructing a relationship structure of factors influencing museum gamification cultural heritage information communication, as shown in Fig. 1. This structure not only reveals the interaction mechanisms between different factors but also elucidates how they collectively influence information communication effectiveness.

This figure reveals a relationship structure of factors influencing museum gamification cultural heritage information communication. This figure was created by the author using Adobe Photoshop 2021. The model consists of four key components (Mapping, Perception, Situational, and Meaning Construction Dimensions), with dashed frames dividing each dimension and its included factors, and different shades of gray blocks identifying hierarchical relationships. The arrows between dimension frameworks indicate the direction of information flow, depicting a dynamic cognitive cycle from museums to audiences. Experience Foundation and Experience Mapping provide a priori conditions for information processing; Sensory, Functional, and Interactive Experiences constitute the initial stage of information reception; Scene and Social Experiences provide a situational framework; while Emotional Identification serves as an integration mechanism that promotes audiences’ transformation from “knowing” to “identifying,” completing the entire cognitive process.

These influencing factors form a dynamic interconnected cognitive system in museum gamification cultural heritage information dissemination. Experience Foundation and experience mapping, as a priori conditions, determine the depth of audience information screening and understanding. Sensory Experience and functional experience constitute the initial link of information reception, activating bodily memory and reducing cognitive load. Interactive experience, through dual intervention of installations and personnel, transforms passive reception into active participation, enhancing the degree of bodily engagement. Scene Experience provides a situational framework for sensory experience, concretizing abstract cultural concepts; social experience, through team collaboration and community interaction, enables audiences to deepen their understanding and identification with cultural content through collective communication. Emotional identification, as the core integration mechanism, transforms the aforementioned experiences into internalized cognition through achievement experience and empathetic design, realizing the transition from “knowing” to “identifying.” This identification prompts audiences to activate more cognitive resources, forming a cognitive cycle from information reception to meaning construction to new meaning generation, ultimately achieving a dynamic balance between cultural heritage information dissemination effectiveness and experience quality.

To validate the reliability and completeness of the findings, additional interviews were conducted with five interviewees with various age backgrounds and cultural interests, ensuring a diverse supplementary sample. The results of independent coding of these data indicated that no new logical or causal relationships were created in the categories of interest, and conceptual categories appearing more than three times had already been included in Table 1. Thus, we inferred that the constructed relationship structure of factors influencing museum gamification cultural heritage information communication had reached theoretical saturation, with a relatively complete category structure.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical review and approval was not required for research with human participants in accordance with local laws and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the patient/participant or the patient’s/participant’s legal guardian/next of kin was not required for participation in this study in accordance with state laws and institutional requirements. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation in the study. Participant anonymity and confidentiality were assured and participation was entirely voluntary.

Results

Based on the aforementioned coding results, this study constructed a theoretical model based on embodied cognition theory, showing the key factors influencing the effectiveness of museum gamification cultural heritage information communication, as shown in Fig. 2.

This figure presents a theoretical model of factors influencing the effectiveness of museum gamification cultural heritage information communication from the perspective of embodied cognition theory. This figure was created by the author using Adobe Photoshop 2021, without using any pre-existing materials or third-party content. The model adopts a triangular structure, with the Meaning Construction Dimension as the core, and the three vertices being the Perception Dimension, Situational Dimension, and Mapping Dimension. The icons in each dimension intuitively display their core connotations—the Mapping Dimension icon expresses the retrieval of previous experiences and memories, the Perception Dimension icon presents multi-channel perception systems, and the Situational Dimension icon shows concrete scenarized experiences. The connecting text between dimensions reveals the interaction mechanisms among the three. The icons above the text further reinforce the content—the magnifying glass on the left symbolizes information retrieval, resonating with cognitive load; the document icon on the right represents the formation process of perceptual experiences, emphasizing the evolution from initial sensory reception to interaction-enhanced experiences; and the cube icon at the bottom symbolizes the concretization of abstract concepts, showing how scene and social experiences transform abstract knowledge into understandable conceptual frameworks. Together, these factors form an integrated cognitive system that can guide museums in designing more effective gamification strategies for cultural heritage information communication.

Analysis of museum gamification communication effect from the perspective of mapping dimension

Experience Foundation refers to the perceptual and cognitive experiences accumulated by audiences through bodily interaction with the environment, which plays a fundamental role in museum gamification cultural heritage communication. Embodied cognition theory emphasizes that human cognitive processes are rooted in bodily perception and conceptual understanding, and audiences’ reception efficiency and comprehension level of exhibition content largely depends on their existing experience foundation74. Experience Foundation consists of two sub-factors: Perceptual Representation and Conceptual Understanding, which together influence how audiences perceive and interpret cultural heritage information in museums. Perceptual Representation emphasizes the bodily perceptual experiences formed and stored by audiences through multiple senses in daily life, including two core elements: Body Memory and Body Awareness.

Body Memory refers to various experiences accumulated by audiences in past life experiences, which provides experiential references for understanding new information. For example, one interviewee said: “When I touched those textures, I immediately recalled various fabrics I had touched in my grandfather’s textile factory when I was a child, which gave me a more intimate understanding of the craft techniques introduced in the exhibition.” (Interviewee 5) These rich perceptual experiences lay the foundation for audiences to understand exhibition content. Body Awareness refers to the audience’s ability to be aware of changes in their own bodily states, enabling them to perceive bodily reactions triggered by exhibition content. One interviewee stated: “When the exhibition hall played the sounds of ancient battlefields, I noticed my heart racing and muscles tensing, and these bodily reactions made me truly feel the tense atmosphere of that era.” (Interviewee 19) In terms of Conceptual Understanding, it mainly involves cognitive frameworks about the relationship between body and external world formed by audiences based on past experiences, including Body Knowledge and Body Attitude. Body Knowledge is the understanding of how the body works gained through personal practice. One interviewee shared: “I have learned traditional crafts, so when I saw ancient tools in the exhibition, I could quickly associate them with their functions and operation methods.” (Interviewee 12) Body Attitude reflects the audience’s tendencies toward specific bodily activities based on past experiences. For example, one interviewee mentioned: “I am an escape room enthusiast and have played many escape room games, so when I saw some props or seemingly mechanical installations during the exhibition, I wanted to check them out.” (Interviewee 6).

Experience Mapping refers to the implicit process by which audiences automatically apply their existing bodily experiences to understand new environments and content, a body-cognition connection mechanism that can be activated without deliberate thinking. In museum gamification cultural heritage communication, Experience Mapping influences how naturally audiences can establish connections with exhibition spaces and interactive installations, thereby affecting the fluency and immersion of information reception75. Experience Mapping consists of two sub-factors: Automatic Process and Skill Acquisition, which together shape the interaction patterns of audiences in museum spaces. Automatic Process involves bodily reactions and adaptive adjustments that audiences make without conscious control, including Posture Regulation and Movement Coordination. One interviewee shared: “I think the sail adjustment section is well-designed. Having to bend down to control the mechanism and then look up to see the ship’s reaction on the screen - this change in body posture made me feel like I was really controlling a ship. It’s much more intuitive than just reading text and looking at pictures; you understand how ancient people controlled ships through your own physical movements.” (Interviewee 12) Skill Acquisition reflects Operation Habits and Interaction Patterns formed by audiences through daily practice, and these acquired skill patterns greatly influence how audiences interact with exhibitions and the effectiveness of these interactions. For example, one interviewee stated: “I’m used to playing games on iPad, so when I saw that touchscreen, I knew how to operate it without reading instructions. But my father had no idea and just stared at it without daring to touch it.” (Interviewee 8) Another audience member shared: “When I visit exhibitions by myself, I have a fixed rhythm - I quickly browse through each exhibition area, then select those I’m interested in to look at carefully, spending about three minutes, and then naturally move to the next point.” (Interviewee 11).

Based on the analysis of influencing factors in the mapping dimension, this study proposes the following suggestions: Regarding Experience Foundation, museum gamification design should provide multi-channel stimuli such as visual, auditory, and tactile at key nodes to evoke relevant bodily memories or experiences of the audience. Second, it should consider experiential differences among audiences with different knowledge backgrounds, providing multiple visiting route options to ensure that different audiences can find visiting paths that match their own experience foundations. Additionally, operation interfaces and interaction methods that conform to the audience’s bodily intuition should be designed to reduce dependence on operation instructions and improve the efficiency and effectiveness of cultural heritage information dissemination. Regarding Experience Mapping, information organization should focus on establishing connections with knowledge previously acquired by audiences in museums, forming a progressive cognitive pathway. At the same time, it is necessary to consider the gradient setting of information complexity, gradually transitioning from simple and intuitive interactions to deeper cultural interpretations, enabling audiences to build new knowledge on familiar experiential foundations.

Analysis of museum gamification communication effect from the perspective of perception dimension

Sensory Experience refers to the process by which audiences fully engage multiple senses such as visual and auditory during their visit. It primarily consists of two sub-factors: Multi-sensory Experience and Synesthetic Experience. In terms of multi-sensory experience, Olfactory Experience serves as a preliminary stimulus, presenting specific scents to evoke emotional memories in audiences; Visual Experience, as the dominant sensory channel, provides direct perception of exhibits’ forms, colors, and structures; Auditory Experience, as a supplement to information, creates specific historical atmospheres through environmental sound effects and audio narration; Tactile Experience, as a perceptual identification channel, breaks through the “look but don’t touch” limitation, enhancing bodily participation. When museums fully engage audiences’ multiple sensory channels and promote sensory synergy, audiences’ reception shifts from a single rational cognitive level to deeper embodied experience, not only enhancing the depth and breadth of information reception but also improving memory retention76. One interviewee described her experience this way: “The canal dock area of the exhibition left a particularly deep impression on me. Not only could I see models of ancient ships, but I could also hear the sound of flowing water and boatmen’s work songs, and there was even a place where I could smell the faint scent of river water and timber mixed together. I immediately perked up and felt as if I was truly at an ancient canal dock, which was much more vivid than simply reading text introductions.” (Interviewee 17) Synesthetic Experience includes two key elements: Sensory Fusion and Spatial Perception. Sensory Fusion breaks the isolation between sensory channels, allowing one sensory experience to trigger or enhance another; Spatial Perception creates a sense of “presence” by integrating spatial factors with sensory experience. This synergistic activation of multiple senses not only enhances audiences’ sense of presence but also compensates for the limitations of certain cultural heritage that are difficult to experience directly due to temporal and spatial constraints77. For example, one interviewee stated: “There was one part of the ‘Canal Mystery’ exhibition that particularly surprised me. They designed a special light and shadow effect, and when you looked at those shimmering projections, somehow you felt a slight coolness and moisture of water, even though there was no actual water.” (Interviewee 23).

Functional Experience refers to the process by which audiences experience visits through functional equipment provided by museums. As the foundational link in cultural heritage information transmission from museums to audiences, it establishes audiences’ first impressions of exhibitions. Functional Experience consists of two sub-factors: System Functionality and Guidance Mechanism. In terms of system functionality, Usability, Stability, and Aesthetics constitute key factors affecting gamification experience. When system usage experience is natural and smooth, interface design is intuitive and clear, and audiences can form barrier-free interaction with exhibition systems, deep embodied connections are established, thus improving information communication efficiency78. For example, one audience member commented on the system’s aesthetics: “I think we could first try to improve the screen resolution. Because to be honest, when playing inside, for instance, there was a boat operation segment, right? This should have been a highlight, a very amazing place. But when looking at that screen, the whole picture was gray and hazy, which actually decreased the experience significantly.” (Interviewee 10) Another interviewee commented on the usability and stability of the system functionality: “The functional experience felt somewhat rigid. For example, there was a segment where you draw the Grand Canal map, I remember it was touch screen operation, requiring location selection. But the touch screen wasn’t responsive, sometimes my finger pressed without reaction, needing to press hard several times. After drawing the whole route, I felt quite tired, because there were many decorations on the screen making it uneven, and the touch screen wasn’t responsive, making operation laborious.” (Interviewee 18) In terms of Guidance Mechanism, the design of Accuracy and Flexibility can effectively reduce audiences’ aimless exploration time, further reducing intermediary heterogeneity79. For example, one interviewee described the flexibility of the guidance mechanism as follows: “The exhibition provided basic guidance, but since most people are unfamiliar with this type of visit format, these preset limited information made it difficult for us to understand the activity’s intention, so we often felt confused at the beginning of the visit. I only truly understood the significance of stamping, the method of selection, and the final goal halfway through. Although I later understood that I could re-experience it, if there had been more flexible and complete guidance from the beginning, the overall experience would undoubtedly have been more smooth and perfect.” (Interviewee 9) In summary, the more complete the system functionality and the more precise the guidance mechanism, the smaller the cognitive distance between audiences and exhibition systems, the higher the interaction transparency, thereby enhancing embodiment and in turn improving audiences’ efficiency in receiving cultural heritage information80.

Interactive Experience refers to the process by which audiences interact with exhibition content during their visit. It relies on two sub-factors: Installation Interaction and Personnel Interaction. In terms of Installation Interaction, museums enable audiences to engage with cultural heritage information in more intuitive ways through Physical Interaction and Virtual Experience, deepening their understanding of information; in terms of Personnel Interaction, through game NPCs providing professional explanation services, on-site guidance assistance, and Q&A exchanges, offering audiences opportunities for deep participation and interaction. While maintaining content professionalism, these interactive experiences not only lower the threshold for understanding cultural heritage information but also enable audiences to become participants and co-creators of exhibitions, stimulating audiences’ learning motivation and information communication effectiveness81. One interviewee shared: “The child particularly liked this exhibition, and we played with the simulated sluice operation device several times. The child turned the handle by himself and watched the water level change, which was more effective than if I had explained it ten times.” (Interviewee 20).

Based on analysis of these three influencing factors, this study proposes the following suggestions: For Sensory Experience, consideration should be given to theme scenes, exhibition layout, and environmental atmosphere, fully utilizing digital technology to enrich sensory stimulation dimensions while avoiding excessive reliance on technology that might weaken ontological display effects. For Functional Experience, museum gamification systems should focus on improving user interface usability, aesthetics, and accessibility, establishing unified interaction design standards, and creating clear game rules and tiered guidance mechanisms. For Interactive Experience, tiered interaction schemes should be designed based on audiences’ age characteristics and cognitive levels, integrating cultural content such as artifact stories and historical scenes into the interaction process, promoting cultural cognition through gamified experience, and deploying staff at key nodes to provide professional guidance, ensuring visiting experience for audiences of different cognitive levels.

Analysis of museum gamification communication effect from the perspective of situational dimension

Scene Experience refers to the process by which audiences perceive, understand, and construct cultural information in specific museum environments. Scene Experience is realized through two dimensions: Scene Construction and Narrative Design. In terms of Scene Construction, museums evoke audiences’ intuitive perception of historical culture through Spatial Layout, Theme Scene, and Props and Equipment; in terms of Narrative Design, museums construct a complete experience process through Plot Arrangement, Flow Guidance, and Cultural Interpretation. Through these situational creations and guidance, audiences can integrate existing cognition with newly acquired cultural heritage information, achieving in-depth understanding and reinterpretation of cultural connotations82. For example, one interviewee mentioned: “The exhibition’s scene arrangement was very thoughtful, including tables, memorials, books, and pens that were designed to imitate the style of that era as much as possible. The walls had both scene-matching arrangements and educational content integrated. For instance, where tools were discussed, there would be tool models and corresponding explanations on the wall; when talking about the canal route, the wall would display the canal route, explaining what components made up the entire canal, how official positions were set at the time, and so on. After walking around, the knowledge imperceptibly entered your mind.” (Interviewee 1) Another interviewee mentioned: “I especially liked the scene after the boat-riding segment, which should have been when we arrived in Yangzhou. After passing through a narrow passage, we suddenly entered a spacious area, and what caught my eye was the exquisite and magnificent memorial arch of Yangzhou. This spatial change from confined to open truly gave me a feeling of sudden enlightenment and brightening.” (Interviewee 19).

Social Experience refers to the cultural atmosphere experience formed by audiences through communication and interaction with other visitors during their visit. Embodied cognition theory emphasizes that there is a close interactive relationship between cognition and communication, and audiences not only receive information in social interaction but also actively construct meaning and create content83. In cultural heritage information dissemination, social interaction plays an indispensable role. Through On-site Interaction and Online Sharing, audiences not only expand the scope and influence of information dissemination but also enrich the forms and content of information exchange. On-site Interaction transforms individual cognition into collective construction through Team Collaboration and Peer Communication. One interviewee described the team collaboration experience: “Since it was my first visit, I formed a team with several strangers who entered at the same time to solve puzzles together. Each person contributed different perspectives and knowledge, and I felt that this co-creation experience made the cultural content more vivid.” (Interviewee 13) In terms of Peer Communication, another interviewee stated: “When visiting with friends, we constantly shared our discoveries and understandings, and this exchange experience gave me a completely different new perspective from visiting alone.” (Interviewee 16) Online Sharing breaks the physical space and time limitations of museums through Social Platform Sharing and Online Interactive Communication, allowing cultural dialogue to continue. Audiences can record, share, and discuss experience content, while also providing museums with opportunities for audience feedback and content co-creation. One interviewee stated: “I really liked this exhibition. So after returning, I excitedly recorded this video and uploaded it to social platforms, telling everyone that they must see this exhibition.” (Interviewee 7).

Based on the analysis of these two influencing factors, this study proposes the following suggestions: For Scene Experience, museum display design should clarify information communication objectives and, based on these objectives, deeply explore thematic elements that can trigger audience situational resonance, organically combining them with historical cultural content to help audiences establish connections between personal experience and cultural heritage. Meanwhile, exhibition spaces and supporting props need to be planned and arranged in coordination with narrative plot development, creating immersive cultural experience atmospheres through environmental changes. For On-site Interaction, cultural heritage institutions should fully recognize that behaviors such as cooperation, communication, and sharing are important interactive methods in museum gamification contexts. Institutions should act as facilitators and coordinators, promoting effective communication among audiences through careful content design and environmental creation. Specifically, museum gamification should design team collaboration tasks, such as level puzzles and multiplayer interaction segments, guiding audiences to complete cultural experiences through cooperation. Additionally, exhibition space planning needs to create environments conducive to social interaction, providing favorable conditions for audiences to share knowledge and exchange experiences. For Online Interaction, museums should expand social contexts through digital platforms, extending the temporal-spatial scope of museum experience through social media interaction, online communities, and user-generated content, forming continuous cultural dialogue networks.

Analysis of museum gamification communication effect from the perspective of meaning construction dimension

Emotional Identification refers to the process by which audiences develop empathy with exhibition content and experience emotional arousal during their visit. Emotion is closely related to the body and forms a bidirectional interactive relationship with cognition84. As an emotional catalyst for internalizing cultural content, emotional identification guides audiences from knowledge acquisition toward value identification, deepening memory and understanding of exhibition content, and promoting subsequent behavioral changes and ideological transformation85. Through two sub-factors—Achievement Experience and Empathetic Design—it builds emotional connections between audiences and cultural heritage. In terms of Achievement Experience, Growth Path establishes a development framework, allowing audiences to perceive their learning progress and knowledge accumulation; Task Challenge sets moderately difficult goals on this basis, providing exploration motivation and challenge enjoyment for cultural experiences; Feedback and Rewards confirm audience participation behavior through timely responses and appropriate rewards, forming a positive cycle. The combination of these three elements can stimulate audiences’ sense of achievement, a positive emotion that not only strengthens audience participation behavior but also promotes long-term memory formation86. One interviewee stated: “At the end of the exhibition, there was a scoring device that calculated scores based on the number of stamps collected in your handbook and displayed your ranking compared to other visitors on the leaderboard. Children would get particularly excited when they saw their scores displayed.” (Interviewee 22) In terms of Empathetic Design, Cultural Identity reduces cognitive distance by connecting with audiences’ existing values and backgrounds; Emotional Resonance establishes emotional bonds by triggering emotional understanding of exhibition content. One interviewee stated: “This format is relatively novel with strong interactivity, and I think young people would particularly like it. People who weren’t originally very familiar with this period of history might also develop an interest because of this game and want to see more or experience other content in the museum.” (Interviewee 6).

Based on the key role of emotional identification in cultural heritage embodied cognition, this study proposes the following specific suggestions for interactive cognition: For Achievement Experience, museums should construct clear participation progression systems, designing multi-level cognitive challenges and growth paths. Museums can utilize rich gamification elements such as task challenges, leaderboard mechanisms, role-playing, and storylines, combined with historical and cultural resources, to create visiting experiences that trigger deep emotional resonance in audiences. Task design should adopt progressive difficulty systems, dynamically adjusting according to audience performance, and providing timely feedback to maintain exploration interest. For Empathetic Design, museums should focus on personal narrative and emotional experience design, using individual stories to bridge the distance between audiences and historical culture. Exhibitions should focus on emotional touchpoint design, using immersive scenes and multimedia narratives to stimulate resonance. Emotional buffer spaces should be provided, especially for sensitive historical themes, and attention should be paid to cultural diversity, ensuring that audiences from different backgrounds can find emotional connection points.

Discussion

Cultural heritage is the living cultural memory of nations and peoples, and is a unique and valuable legacy with important protection and dissemination value. In an era of deep integration between digital media and technology, cultural communication and experience methods are becoming increasingly diverse, with the public displaying stronger initiative and emotional needs while also exhibiting characteristics of dispersed attention. Museums, as important public cultural service providers and information dissemination subjects, need to adopt innovative communication strategies to adapt to these changes. Against this backdrop, gamification, with its advantages in high attractiveness and motivation stimulation, has become one of the hot trends in museum practice, offering new possibilities for cultural heritage information dissemination. However, there exists an inherent contradiction between the professionalism of cultural heritage information and the entertainment nature of gamified experiences, raising two core questions: How can we construct a museum gamification communication paradigm adapted to the characteristics of cultural heritage? How can we ensure communication effectiveness while considering public experience? This study, by introducing embodied cognition theory and based on analysis of interview data from 23 visitors to the “Canal Mystery” exhibition, constructs a theoretical model of factors influencing the effectiveness of museum gamification cultural heritage information communication, aiming to provide new theoretical perspectives and practical pathways for addressing these questions.

Specifically, this study analyzes how embodied cognitive factors influence the effectiveness of museum gamification cultural heritage information communication from four dimensions of embodied cognition theory, exploring pathways to resolve the two core questions mentioned above. The mapping dimension reveals how cognitive processes are rooted in a priori bodily experiences. This study shows that audiences’ bodily experience foundation and experience transformation tendencies constitute important prerequisites for cultural cognition, affecting the depth and breadth of information reception. For example, in the “Canal Mystery” exhibition, when audiences touch samples of different materials, they often automatically associate them with relevant past experiences, establishing a more intimate understanding of canal culture. Such experience mapping is not merely knowledge transmission but a deep meaning-construction process based on the body, requiring museum gamification design to fully consider individual audience experience differences and provide information acquisition channels that align with bodily intuition, thereby reducing cognitive load for audiences.

The perception dimension highlights the critical nature of the body as a cognitive medium. The uniqueness of museum communication lies in its spatial characteristics, where audiences must complete their visiting experience through bodily activities. For example, the “Canal Mystery” exhibition effectively activates audiences’ bodily perception through aesthetic interface design and rich multi-sensory stimulation. However, interviews also revealed negative impacts on experience caused by issues such as insufficient system stability and inadequate guidance. This reminds decision-makers that technology application should not remain superficial but should consider how to build bridges connecting audiences’ bodies with cultural content, which is crucial for constructing museum gamification communication paradigms adapted to cultural heritage characteristics.

The situational dimension emphasizes that cognition always occurs in specific environments. Traditional museum displays often focus too much on content itself while neglecting the role of context in information understanding. In the “Canal Mystery” exhibition, audiences are not passive recipients of historical knowledge but enter historical scenes through contextualized game experiences, gradually understanding canal culture while playing specific roles and completing tasks. This situational experience transforms abstract cultural concepts into concrete bodily experiences, turning museums from mere exhibit display spaces into dynamic spaces for meaning generation, thus enhancing audience experience while ensuring communication professionalism.

The meaning construction dimension reveals how dynamic interactions between cognition, body, and environment form holistic cognitive systems. In the “Canal Mystery” exhibition, as audiences experience exhibition content and develop empathy and sense of achievement, they not only gain knowledge-based understanding of cultural heritage but also form emotional identification and resonance. This emotional experience process holds significant importance for both audiences and museums, helping audiences transform from mere “knowing” to value-based “identifying.” This identification prompts audiences to activate more cognitive resources, forming a cognitive cycle from information reception to meaning construction to new meaning generation, ultimately achieving a dynamic balance between cultural heritage information dissemination effectiveness and experience quality.

In summary, the theoretical model proposed in this study responds to the two core questions posed at the beginning of the article. On one hand, the four-dimensional theoretical framework provides systematic pathways for constructing museum gamification communication paradigms adapted to cultural heritage characteristics, clarifying the mechanisms between experience mapping, sensory participation, and situational atmosphere; on the other hand, combined with empirical analysis of the “Canal Mystery” case, it explores how the model ensures communication effectiveness while considering public experience. However, the theoretical model proposed in this study still requires further verification, with current main limitations being sample restrictions and insufficient quantification of inter-variable relationships. Future research should expand sample scope, apply the model to different types and regions of museum cases, and refine inter-variable relationships through quantitative research to further enhance the scientific validity and universality of the theoretical model. Through these in-depth explorations, we look forward to providing more systematic and profound guidance for how museums can effectively communicate cultural heritage in the digital age.

Data availability

The data for this study were obtained through interviews. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The data analysis for this study was conducted using NVivo Release 1.2 (426) software (QSR International). The software was used to assist with coding and grouping qualitative interview data. Access to the NVivo project file is restricted due to privacy concerns, but the general methodology and coding structure can be shared upon request.

References

Arrigoni, G., Schofield, T. & Trujillo Pisanty, D. Framing collaborative processes of digital transformation in cultural organizations: from literary archives to augmented reality. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 35, 424–445 (2020).

UNESCO. Declaration of Principles of International Cultural Co-operation. https://www.unesco.org/en/legal-affairs/declaration-principles-international-cultural-co-operation (UNESCO, 1966).

Li, P. Cultural communication in museums: a perspective of the visitors experience. PLoS ONE 19, e0303026 (2024).

Dah, J. et al. Gamification equilibrium: the fulcrum for balanced intrinsic motivation and extrinsic rewards in learning systems. Int. J. Serious Games 10, 83–116 (2023).

Hamari, J., Koivisto, J. & Sarsa, H. Does gamification work? A literature review of empirical studies on gamification. in Proc. 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences 3025–3034 (IEEE, 2014).

Skiba, D. J. On the horizon: the year of the MOOCs. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 34, 136–137 (2013).

Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R. & Nacke, L. From game design elements to gamefulness: defining “gamification”. in Proc. 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments 9–15 (2011).

Ferdani, D., Fanini, B., Piccioli, M. C., Carboni, F. & Vigliarolo, P. 3D reconstruction and validation of historical background for immersive VR applications and games: the case study of the forum of Augustus in Rome. J. Cult. Herit. 43, 129–143 (2020).

Heide, A. & Želinský, D. Level up your money game: an analysis of gamification discourse in financial services. J. Cult. Econ. 14, 711–731 (2021).

Hewapathirana, N. T. & Caldera, S. A conceptual review on gamification as a platform for brand engagement in the marketing context. Sri Lanka J. Mark. 9, 41–55 (2023).

Hudson, K. A Social History of Museums: What the Visitors Thought (Macmillan, 1975).

Ouariachi, T. & Wim, E. J. L. Escape rooms as tools for climate change education: an exploration of initiatives. Environ. Educ. Res. 26, 1193–1206 (2020).

Prakash, D. & Manchanda, P. Designing a comprehensive gamification model and pertinence in organizational context to achieve sustainability. Cogent Bus. Manag. 8, 1962231 (2021).

Van der Heijden, B. I. J. M. et al. Gamification in Dutch businesses: an explorative case study. SAGE Open 10, 2158244020972371 (2020).

Zainuddin, Z., Kai, S., Chu, W., Shujahat, M. & Perera, J. The impact of gamification on learning and instruction: a systematic review of empirical evidence. Educ. Res. Rev. 30, 100326 (2020).

Krzywinska, T., Phillips, T., Parker, A. & Scott, M. J. From immersion bleeding edge to the augmented telegrapher: a method for creating mixed reality games for museum and heritage contexts. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 13, 1–20 (2020).

Díaz-Kommonen, L., Svinhufvud, L., Thiel, S. & Vishwanath, G. Enriching museum collection with virtual design objects and community narratives: pop-up-VR museum. Collections 20, 77–95 (2024).

Anderson, S. L. The interactive museum: video games as history lessons through lore and affective design. E-Learn. Digit. Media 16, 177–195 (2019).

Garris, R., Ahlers, R. & Driskell, J. E. Games, motivation, and learning: a research and practice model. Simul. Gaming 33, 441–467 (2002).

Hsu, T. Y. & Liang, H. Y. Museum engagement visits with a universal game-based blended museum learning service for different age groups. Libr. Hi Tech 40, 1226–1243 (2021).

Gaudreau, C., Bustamante, A. S., Hirsh-Pasek, K. & Golinkoff, R. M. Questions in a life-sized board game: comparing caregivers’ and children’s question-asking across STEM museum exhibits. Mind Brain Educ. 15, 199–210 (2021).

Deng, Y. & Chai, Q. Reconstructing museums’ relationships with their audience through gamification. Southeast Cult. 4, 140–147 (2024).

Fortunati, L. Is body-to-body communication still the prototype?. Inf. Soc. 21, 53–61 (2005).

Anderson, M. L. Embodied cognition: a field guide. Artif. Intell. 149, 91–130 (2003).

Stein, L. A. Challenging the computational metaphor: implications for how we think. Cybern. Syst. 30, 473–507 (1999).

Hilditch, D. J. At the Heart of the World: Merleau-ponty and the Existential Phenomenology of Embodied and Embedded Intelligence in Everyday Coping [dissertation] (Washington University in St Louis, 1995).

Heidegger, M. Basic Writings: From Being and Time (1927) to the Task of Thinking (1964) (Harper & Row, 1977).

Ihde, D. Technology and the Lifeworld: From Garden to Earth (Indiana University Press, 1990).

Ihde, D. Postphenomenology and Technoscience: The Peking University Lectures (SUNY Press, 2009).

Niedenthal, P. M., Barsalou, L. W., Winkielman, P. & Krauth-Gruber, S. Embodiment in attitudes, social perception, and emotion. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 9, 184–211 (2005).

McLuhan, M. Understanding Media: the Extensions of Man (MIT Press, 1994).

Parisi, D. & Archer, J. E. Making touch analog: the prospects and perils of technologically mediated touch. Soc. Stud. Sci. 47, 582–607 (2017).

Jin, L., Xiao, H. & Shen, H. Experiential authenticity in heritage museums. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 18, 100493 (2020).

Allwood, J. Dimensions of embodied communication-towards a typology of embodied communication. in Embodied Communication in Humans and Machines 257–284 (2008).

Biocca, F. The cyborg’s dilemma: progressive embodiment in virtual environments. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 3, JCMC324 (1997).

Hooper-Greenhill, E. (ed.) The Educational Role of the Museum (Psychology Press, 1999).

Bonacini, E. & Giaccone, S. C. Gamification and cultural institutions in cultural heritage promotion: a successful example from Italy. Cult. Trends 31, 3–22 (2022).

Luo, D., Doucé, L. & Nys, K. Multisensory museum experience: an integrative view and future research directions. Museum Manag. Curation. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2024.2357071 (2024).

Tan, F., Gong, X. & Tsang, M. C. The educational effects of children’s museums on cognitive development: empirical evidence based on two samples from Beijing. Int. J. Educ. Res. 106, 101729 (2021).

Schaper, M. M. & Pares, N. Co-design techniques for and with children based on physical theatre practice to promote embodied awareness. ACM Trans. Comput. Hum. Interact. 28, 22 (2021).

Ahn, S. J., Bailenson, J. N. & Park, D. Short- and long-term effects of embodied experiences in immersive virtual environments on environmental locus of control and behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 39, 235–245 (2014).

Dunkley, R. Ecological kin-making in the multispecies muddle: an analytical framework for understanding embodied environmental citizen science experiences. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 48, 781–796 (2023).

Van Duppen, J. & Spierings, B. Retracing trajectories: the embodied experience of cycling, urban sensescapes and the commute between ‘neighbourhood’ and ‘city’ in Utrecht. NL. J. Transp. Geogr. 30, 234–243 (2013).

Henshaw, V. & Guy, S. Embodied thermal environments: an examination of older-people’s sensory experiences in a variety of residential types. Energy Policy 84, 233–240 (2015).

Truelove, Y. Rethinking water insecurity, inequality and infrastructure through an embodied urban political ecology. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 6, e1342 (2019).

Smith, L. & Campbell, G. The elephant in the room: heritage, affect, and emotion. in A Companion to Heritage Studies 443–460 (John Wiley & Sons, 2015).

Duranti, D., Spallazzo, D. & Petrelli, D. Smart objects and replicas: a survey of tangible and embodied interactions in museums and cultural heritage sites. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 17, 1–32 (2024).

Vom Lehn, D. Embodying experience: a video-based examination of visitors’ conduct and interaction in museums. Eur. J. Mark. 40, 1340–1359 (2006).

Zhang, J. et al. Embodied power: how do museum tourists’ sensory experiences affect place identity?. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 60, 334–346 (2024).

Zhang, J. & Xu, C. A grounded theory-based model of information communication in cultural heritage digital reading on the social media from the perspective of the embodied theory. Herit. Sci. 12, 208 (2024).

Clark, A. Supersizing the Mind: Embodiment, Action, and Cognitive Extension (Oxford University Press, 2010).

Barsalou, L. W. Perceptual symbol systems. Behav. Brain Sci. 22, 577–660 (1999).

Glenberg, A. M. Embodiment as a unifying perspective for psychology. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 1, 586–596 (2010).

Damasio, A. The Strange Order of Things: Life, Feeling, and the Making of Cultures (Vintage, 2019).

Yin, F. Y. & Goller, T. Embodied schema information processing theory: an underlying mechanism of embodied cognition in communication. Commun. Theory 34, 154–165 (2024).

Chiel, H. J. & Beer, R. D. The brain has a body: adaptive behavior emerges from interactions of the nervous system, body and environment. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 553–565 (1997).

Niedenthal, P. M. Embodying emotion. Science 316, 1002–1005 (2007).

Brown, J. S., Collins, A. & Duguid, P. Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educ. Res. 18, 32–42 (1989).

Clark, A. & Chalmers, D. The extended mind. Analysis 58, 7–19 (1998).

Brooks, R. A. Intelligence without representation. Artif. Intell. 47, 139–159 (1991).

Thelen, E. & Smith, L. B. Dynamic systems theories. in Handbook of Child Psychology, Vol. 1 (Wiley, 2007).

Glaser, B. & Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory (Adelin, 1967).

Zheng, J. Game-based learning in museums: the interactive exhibition of “The Directorate of Waters and the Grand Canal in the Ming Dynasty”. Southeast Cult. 3, 161–166 (2021).

Ren, Y. Exploring the immersive cultural and creative operation model of the Grand Canal under the background of culture and tourism integration: a case study of China Grand Canal Museum of Yangzhou. Cult. Relics World 12, 120–123 (2024).

Veldkamp, A. et al. Escape education: a systematic review on escape rooms in education. Educ. Res. Rev. 31, 100364 (2020).

Canal Museum. https://canalmuseum.net/yunboxinwen/420.html (2023).

Patton, M. Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods (SAGE Publications, 1990).

Martin, P. Y. & Turner, B. A. Grounded theory and organizational research. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 22, 141–157 (1986).

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. Grounded theory methodology: an overview. in Handbook of Qualitative Research (eds Denzin, N. K. & Lincoln, Y. S.) 273–285 (SAGE, 1994).

Chen, Q. P., Wu, J. J. & Ruan, W. Q. What fascinates you? Structural dimension and element analysis of sensory impressions of tourist destinations created by animated works. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 26, 1038–1054 (2021).

Noble, H. & Heale, R. Triangulation in research, with examples. Evid. Based Nurs. 22, 67–68 (2019).

Lopez, B. G. Incorporating language brokering experiences into bilingualism research: an examination of informal translation practices. Lang. Linguist. Compass 14, e12361 (2020).

Wang, Y. & Jang, H. Immersive experience of Chinese public cultural space: focusing on the Grand Canal Museum of China. J. Region Cult. 11, 135–151 (2024).

Helmke, A. & Schrader, F.-W. School achievement: cognitive and motivational determinants. in International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (eds Smelser, N. J. & Baltes, P. B.) 13552–13556 (Pergamon, 2001).

Papagiannakis, G. et al. Mixed reality, gamified presence, and storytelling for virtual museums. in Encyclopedia of Computer Graphics and Games 1150–1162 (Springer International Publishing, 2024).

Ch’ng, E., Cai, S., Leow, F. T. & Zhang, T. Adoption and use of emerging cultural technologies in China’s museums. J. Cult. Herit. 37, 170–180 (2019).

Wang, H. et al. Grand challenges in immersive technologies for cultural heritage. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2025.2475996 (2025).

Xu, N. et al. CubeMuseum AR: a tangible augmented reality interface for cultural heritage learning and museum gifting. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 40, 1409–1437 (2023).

Capece, S. et al. Advanced systems and technologies for the enhancement of user experience in cultural spaces: an overview. Herit. Sci. 12, 71 (2024).

Korzun, D., Yalovitsyna, S. & Volokhova, V. Smart services as cultural and historical heritage information assistance for museum visitors and personnel. Balt. J. Mod. Comput. 6, 418–433(2018).

Liu, Y. Evaluating visitor experience of digital interpretation and presentation technologies at cultural heritage sites: a case study of the old town, Zuoying. Built Herit. 4, 14 (2020).