Abstract

This work describes the design of reproducible mock-ups with controlled soot deposition, created to support comparative cleaning tests within the EU Horizon MOXY project. The latter develops atmospheric, plasma-generated, monoatomic oxygen as a cleaning method to remove (amongst others) fire-born soot from heritage objects. A literature review highlights the complexity of soot while revealing a lack of focus on the representativeness of artificial soot in previous studies. We benchmarked two approaches: (I) indirect/cold application of pre-fabricated soot and (II) direct/hot application via ongoing combustion. The results demonstrate that direct combustion yields soot with markedly different physical and chemical characteristics. Chemical analysis (Raman, XRPD, TGA, EGA-MS, XPS) and microscopic imaging (3D optical, SEM) revealed differences in composition, morphology, and deposition behaviour on substrates like paper, silk, paint and plaster. We selected the ‘smoke drum’ method as the most practical and reproducible approach for mimicking fire-born soot in heritage cleaning research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Within the preservation of cultural heritage (CH), soot remains an unresolved challenge. When conservation strategies are designed for soot-affected objects, first-aid cleaning procedures are often applied, as the carbon-based deposition either darkens and discolours the appearance of the object significantly1 or decreases its transparency (e.g. in case of stained glass)2,3,4. More importantly, soot is also considered to jeopardize the long term stability of the underlying materials. A well-known example is for instance the surface recession of limestone5, due to the catalytic role that soot plays in gypsum crust formation6. Lamhasni et al. demonstrated that the presence of hazardous polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the black crust, associated to diesel soot, is causing degradation of historical buildings in urban areas7. Also, Gomez-Heras et al. demonstrated how the permeability and hydrophobicity of stone was reduced by a layer of soot, leading to severe dehydration of the surface8. Next to that, soot has been observed to accelerate the degradation process of metals and textiles due its pH acidity by absorbed pollutant gasses such as SO29,10,11,12.

Nevertheless, soot is difficult to remove. Soot aggregates can electrostatically or chemically bond to surfaces due to their submicrometric size and chemical nature, risking tighter adherence or deeper penetration into objects upon treatment. The complexity for conservators is further amplified when dealing with porous or fibrous substrates (e.g. lithic materials, paper, textiles etc.) or highly fragile objects precluding contact cleaning methods. In spite of this relevance, soot-related research remains relatively limited within the field of heritage science. However, as illustrated by the graph in Fig. 1, the overall interest in particulate matter, of which soot is a fraction, has been growing since the turn of the millennium. This is partly due to an increasing interest in effects of air pollution but also to the emerging awareness for climate change, with warmer and drier conditions contributing to a higher probability of fire ignitions13. In 2023, the hottest year in human history, wildfires burned across an area of 135,000 ha in four Mediterranean countries in just 12 days14, and devastated historic sites and museums on the Hawaiian island of Maui15. It is predictable that soot impairment of cultural heritage will become commonplace as climate becomes more extreme. This paper frames within this concern, as the research reported here is part of the MOXY project, funded by the European Horizon 2020 program, that aims to develop plasma-generated atomic oxygen into a viable treatment method for climate-related cleaning challenges.

Left: graph showing the chronological distribution of 159 WoS papers, published between 1997 and 2024, with topics in “particulate matter” AND “cultural heritage”. Right: graph showing 33 WoS articles published between 2002 and 2024 with topics in “soot” AND “cultural heritage”. Please note that half of these papers were published since 2018, whereas the dotted trend lines in both graphs illustrate an overall increasing interest in soot-related issues in heritage conservation.

Soot usually refers to dark deposits observed visually but it is a more intricate material as often assumed. In fact, Grau-Bové and Strlič pointed out that there is no standard definition of the word “soot” in a heritage context16. Baumgardner et al. defined soot as the carbonaceous material in particulate matter that is produced by combustion. Based on its optical properties, the light-absorbing fraction is often referred to as black carbon (BC). However, BC has a large surface area that can absorb a wide variety of organic and inorganic chemicals, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and toxic metals. From a chemical perspective, soot can contain elemental carbon (EC) and organic carbon (OC)17 as well as inorganic impurities, as illustrated by Fig. 2, with OC representing a large variety of particulate organic compounds, including aliphatic, alcohols, acids and PAHs. We therefore define soot as the light-absorbing, carbonaceous aerosols (i.e. elemental carbon and organic carbon) associated with the dark fraction of particulate matter (PM)17,18,19,20. Still, the composition, morphology, size, and optical properties of soot can differ substantially depending on its origin and generation conditions. Long et al. compared the physical and chemical characteristics among diesel, gasoline, biomass, and residential wood-burning21. According to this paper, diesel soot contains an average higher EC content than other sources, whereas fresh soot particles from biomass burning are often brownish due to a higher OC content of approximately 55% of the fine particle emission22.

Therefore, a first distinction is made between instantaneous deposition of ‘hot’ soot from open fires and the delayed and gradual deposition of ‘cold’ soot stemming from air pollution. In aerosol and environmental science, the terms “particulate matter (PM)” and “black carbon” are extensively used. (Source: Scopus and web of science). In this context, the main source of PM comes from energy production, of which the (incomplete) combustion of fossil fuels and biomass plays a prominent role. In heritage literature, PM-related issues are mostly associated with the ensuing impact on architectural heritage and its constituting lithic materials23, on which soot particles accumulate and with which it can eventually interact. The well-known black encrustations formed on stone monuments result from the reaction with SO2 together with the embedding of carbonaceous PM24. Nevertheless, museum objects can be affected as well, as authors demonstrated that fine particles are able to penetrate to the indoor environment even when a filtered air ventilation system is in place25. Anaf et al. monitored that outdoor particulates contributed to 80% fine fractions of all indoor particles (PM2.5 and PM1) at the Plantin-Moretus Museum (Antwerp, Belgium)19,26.

However, in this work we focus on ‘hot’ soot that is deposited instantly from an open flame that is in close distance to the art object, i.e. candle burning and fire calamities, and not on the gradual deposition of ‘cold’ soot by air pollution27. Falk et al. recently indicated fire as one of the most prominent hazards for cultural heritage sites, with 48% of sites in Europe falling into the high risk and 31% in medium risk category. Apart from soot covering, fires obviously have other detrimental effects on the object itself, among which discoloration due to thermal oxidation and cracking, but these fall outside the scope of this paper28,29. Next to the nature of the damage also the magnitude of structure fires is defying. Fires typically affect a vast number of artefacts, or large surfaces, within a brief period. For example, after the fire at the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek in 2004, 47% of the 118.000 damaged books were found contaminated with soot, taking conservators 14 years for cleaning30.

The physical structure of soot freshly emitted from flames was characterized as fractal aggregates and composed of particles in the 10–50 nm range31. Next to simply drifting down, fire-born soot usually adheres to any substrate that is cooler than the heart of the fire32. The inadequate combustion of joss sticks, oil lamps and candles used for lighting or spiritual purposes typically results in a blackening of walls and ceilings, with the deposits following the thermally-induced vertical airflows33,34. Pagels et al. measured that church candles emit about 16 mg of soot per hour, with particles containing a multitude of organic substances next to elemental carbon. As the particle size is extremely fine, soot can penetrate into the surface of buildings and artefacts and attach to the substrate with chemical forces35,36. From a chemical point of view, present-day candles are mostly made up of paraffin wax which are mixtures of hydrocarbons with carbon numbers ranging from C20-C40. The soot formation process involves six well-known processes, starting from pyrolysis of hydrocarbons, formation of precursors and nucleation, to surface growth, agglomeration, till soot oxidation, which entirely occur in a few milliseconds37. According to Veshkini et al., the first generated species including molecular precursors and PAHs are decided by the composition of feedstock and oxygen level, then polymerized into primary soot particles which grows by surface reaction and coagulation (see in Fig. 3)38. In the particle (or sooting) zone where usually black smoke appears, the particles become larger through agglomeration, as they move away from the flame and eventually oxidize in the air. Therefore, one can obtain different species possessing certain physio-chemical properties (e.g. particle size, attractive force, adhesion energy) at different heights above the burner39. In the case of candle burning, the flame is not always steady and can be easily fluctuated by draft air, and soot is generated when there is not sufficient oxygen for combustion. In contrast, the steady-burn state is often colourless, containing complete combustion products, e.g. CO2 and H2O40.

Schematic diagram of soot formation38.

Soot from fire calamities is anticipated to be even more complex and of unpredictable composition as the mixture of gases and particles in the smoke varies with the specific combustion sources, temperature, and oxygen concentration of each fire41. A typical structure fire may involve various plastics (insulations foams, fabrics, carpets, surface coatings, etc.) and natural products (wood, paper, wool, oils etc.) that undergo pyrolysis32. The distinction is relevant as soot particles generated from the burning of candles, coal, tobacco or diesel fuel have common features, such as a high EC content which is combined with other chemical elements, a high light absorbance, and an aggregate-like shape. Most of these particulates adhere less strongly to substrates as compared to soot from structure fires and can be removed by means of vacuuming or dedicated sponges42. On the other hand, soot from structure fires is often greasy due to high content in OC. For example, after the 1985 fire at the Huntingdon Art Gallery, the EC/OC ratio of soot was 50/50, particularly sticky and left yellow or brown staining after cleaning. While fire that burned from organic material such as plastics and rubbers is often harder to observe and has a pungent odour43.

In view of this complexity, and as a starting point of our own MOXY research project that aims to remove fire-born soot from heritage objects, a literature search was performed on how cleaning tests for soot removal were performed in the past. Next to a number of papers that aim to provide a first-aid protocol for fire emergencies44,45, allowing to secure artworks swiftly, our query resulted in nine publications that (comparatively) test various cleaning approaches33,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53. In some cases, the cleaning tests were conducted on historical samples, secured after fire damage or naturally contaminated by their environment54,55. Notwithstanding being realistic, each case is anticipated to be somewhat different in terms of soot composition and type of the substrate material, with the specific conservation state of each object potentially having an unknown effect on the test results. It is also not always clear to what extent the artefacts and their contamination are representative and can be extrapolated to a larger corpus of cases. In order to allow for systematic and reproduceable comparison with other materials and to permit benchmarking with other cleaning methods, we propose to integrate the testing on real-life cases in a methodology involving Simplified Model Samples (SMS), often referred to as “mock-ups”, and a standardized soot application routine. Such a generic framework for cleaning tests is further developed within the MOXY project and its assessment will be subject of a separate paper. In this paper, the processes that were reported in literature for soot application on mock-ups are summarized and assessed according to the repeatability, morphology and representativity of the resulting soot. In this way, the most reliable soot reproduction method for assessing atomic oxygen cleaning within the MOXY project was selected.

In our literature survey, we found authors discussing soot removal using various methods, not seldom a combination of wet and dry cleaning methods. Approaches include vacuum cleaners42,56, sponges57, brushing58, erasers47,59,60, groomsticks (a sticky, kneadable eraser)60, solvent61,62 and gel cleaning46,63,64, dry ice blasting65,66,67,68, supercritical CO258,69, laser ablation51,52,70,71 and plasma-generated atomic oxygen54,55,72,73,74. Overall, most papers focus on the cleaning results, rather than assessing the soot simulation itself. Although an understandable approach, by passing over this step, the eventual outcome of the results might be jeopardized from the beginning. In search for a controllable and representative reproduction method to contaminate simplified model samples with soot, we assess the ways fire-born soot was reproduced and applied on substrate materials in these studies. As illustrated by the scheme in Fig. 4, the methods can be divided into two main categories: (I) indirect ‘cold’ application of pre-made soot particles and (II) direct ‘hot’ deposition by an ongoing combustion.

Several authors employ an indirect-cold application method (I) which can be further divided into dry (IA) and wet (IB) application of prefabricated soot particles (Table 1). For (IA), brushing with soot is the most straightforward way to apply. Mašková et al. artificially soiled paper samples by brushing and rolling three types of carbonaceous soiling, including candle soot, PM1 ambient particles, and library dust. The particles were applied directly without solvents, to avoid dissolution of the soot itself65,75. Duncan et al. proposed a method in which samples are shaken in a closed container together with a weighted amount of soot powder. After allowing the soot to settle for 2 min, any loosely adhered particles were removed by a hand-pumped air blower. In this case, the samples were pieces of paper mounted to glass slides and adhered to the bottom of a secured plastic container which was shaken by hand for 30 s47,48. This approach is similar to, and possibly grafted on, an industrial protocol for soiling tests of textiles, such as ISO 11378-2 for floor coverings. According to this procedure, a standard soiling compound is first pre-mixed with the samples in a container, after which these are placed in rotating drum for 30 min together with a heavy, chrome alloy steel ball. In the third and final step, the soiled mock-ups are cleaned with a suction cleaner to remove any loose soil and textile fibres. The prescribed standard soiling compound, referred to as “C5”, contains only 1.75% of soot, next to 38% of peat moss and 51% of various inorganic ingredients (cement, clay and silica), but it can obviously be customised76. K.von Lerber et al. had silk crêpe fabrics soiled by Swissatest technicians. The process was described as “rubbing the carbon into the fabric” in an as evenly distributed way as possible. According to the author, the process took >30 min, but it was not possible to make a quantitative indication of the soot amount, also as during shipping, some carbon was detached from the silk71.

A superior degree of control can be obtained by a commercial combustion aerosol generator (‘MiniCAST’, Jing Ltd, CH) that was developed for calibration purposes and testing of soot filters, smoke alarms and environmental research. These instruments are designed to simulate particulate matter by incinerating propane or fuel gasses in a diffusion flame. In contrast to e.g. Bunsen burners that produce premixed flames, the oxidizer and fuel remain separated before burning thus involving both diffusion and convection processes similar to regular fires. In a diffusion flame, combustion takes place at the flame surface only. As there is not always sufficient oxidizer for complete reaction, diffusion flames usually produce more soot and (yellow to orange) light than premixed flames. Tuning the oxygen vs fuel gas mixture, as well as the flow of quenching and dilution gasses allows adjusting mass output, particle size and organic vs. elemental carbon content. According to Ess et al., the ensuing soot generation is stable and reproduceable. In contrast with other methods, the combustion chamber is completely sealed thus preventing any impact by ambient temperature and RH, while an inert quenching gas (e.g. N2) stabilizes the soot by inhibiting further combustion. More detailed information can be found elsewhere77,78. MiniCASTS are usually included in larger setups for environmental studies, such as the CIME climate chamber that simulates gaseous pollution and various PM deposition in an urban environment, including climate control (RH, temperature, irradiation, etc.)79. As the sample chamber is controlled at 20 °C with a continuous injection of quenched soot, rather than positioning the sample directly next to the flame, this method is not categorized as II. Hot Combustion but rather as IA. Cold Application. To our knowledge, the CIME setup in Paris is the only instrument employed for heritage materials but this was not accessible for our study. Nonetheless, in spite of being very promising, the prerequisite of a gaseous combustion source can be a limitation in the context of cleaning heritage objects, at it excludes burning solid sources such as wood, plastics etc.

For (IB), the cold and wet application of soot, Ortega-Saez et al. proposed manually brushing out soot particles that were first dispersed in water and applied to the substrate by rubbing a cotton swab over the surface. In this case, the substrate was a barite-silver-gelatin layer on photographic print paper. Afterwards, the prints were allowed to air dry between two layers of tissue paper and a light weight was placed on top to avoid deformation of the paper64. Bertasa et al. artificially soiled feathers using carbon black pigment which was selected to simulate soot contamination due to the past display in coal-heated rooms in Victorian times or damage from fire. Carbon black was applied by brushing after damping the feather with milli-Q water, then dried at room temperature for 7 days and the excess of soot was brushed away52.

Brockmann et al. dispersed lamp black powder in white spirit and sprayed it onto the surface of silk fabric in an attempt to obtain a more homogenous distribution of particles while avoiding damaging the textile fibres. As pointed out by the author, the latter can happen through rubbing applications that are sometimes used in industry. Before spraying, 0.06 g of lamp black pigment was added to 40 ml petroleum in a beaker and placed in an ultrasonic bath for 15 min to disperse evenly. The sprayer had a two-fluid nozzle, which used air with a pressure of 3 bar, and sprayed from a distance of c. 29 cm. In order to improve homogenous distribution, the author designed an automated setup, shown in Fig. 5. A silk fabric was attached on a holder and passed the spray outlet four times at a constant speed and distance. After the application, the solvent was allowed to evaporate. The latter (semi-)automated spray setup is anticipated to yield the highest degree of reproducibility, but the eventual amount of soot retained on the sample seems hard to control and/or to check.

Scheme showing the home-built spraying setup used by Brockman for automated soot application70.

However, next to the application method, the source of the simulated soot particles is a key parameter as well. Despite the fact that soot from an open flame can have an EC/OC ratio in the range of 50/50 (as mentioned earlier in this section), the aforementioned studies employed a commercial ‘carbon black’ (CB) pigment, consisting of fine black powder of nearly pure EC (>97%) in an attempt to mimic soot47,52,70. As such, the choice for CB pigments can endanger the representativeness of the SMS for real fire-born soot, and this is especially the case when considering the potential confusion of commercial nomenclature and the fact that few pigment suppliers specify what materials are exactly burned and in which manner. Duncan et al. used a ‘lamp black’ from Natural Pigments company (NP), which is described as retaining variable proportions of the tarry products from imperfect combustion in modern oil furnaces48. Brockmann et al. employed Kremer’s ‘Flammruß’, nowadays sold as ‘furnace black’, product nr. 47250. This is described as a largely pure amorphous carbon with only small admixtures of inorganic components and tar, obtained artificially by “controlled” combustion70. It is assumed to be chemically identical to the lamp black from Natural Pigments, according to the same CAS Number: 1333-86-4.

However, ‘carbon black’ appears a generical term that includes several products made by different processes methods, i.e. ‘furnace black’, ‘lamp black’, ‘acetylene decomposition’, and ‘thermal process’ as summarized in Table 280. ‘Furnace black’ is produced by partial combustion of liquid hydrocarbons in a closed furnace at higher temperatures around 1800 oC with a deficiency of oxygen. The particle size and distribution are well controlled to obtain a specific grade of carbon black20,21. The historical way to produce ‘lamp black’ is by burning various organic materials, such as tree resins, tar, pitch, wood, mineral or vegetable oils etc, and collecting the condensed smoke from the walls of the combustion chamber. This method was used to obtain black pigment until the nineteenth century when industrial production became dominating. Modern lamp black is made from burning aromatic oil in an apparatus similar to the historical way, but with a more controlled air flow. Nowadays, historical lamp black processes were mostly replaced by the ‘furnace process’, which is the most popular and well-established process contributing to about 90% of the CB production worldwide. The associated “acetylene black” and “thermal black” is produced via thermal decomposition of acetylene and natural gas respectively, which is significantly different from the typical oxidation process.

As Georg Kremer specified in e-mail communication that furnace black from Kremer pigments (product nr. 47250) is produced by thermal decomposition of acetylene gas around 2000 °C, we can consider this as acetylene black as explained previously. The ensuing product consists of nearly pure carbon, but lacks the semi-burnt, partly aromatic carbon compounds, like remnants from wax or tar. In an attempt to obtain soot that is closer to the soot contamination from fire damage, the supplier recommends to use (or mix furnace black with) beechwood tar (product nr. 79800, containing ca 40% of phenol and <1% of naphthalene) or beechwood soot (called ‘bistre’, product nr. 12100) that they offer for sale as a varnish additive and watercolour pigment respectively81. On the other hand, the lamp black from Natural Pigments is described “not a pure carbon, but retains variable proportions of the tarry products of imperfect combustion; these tarry products impart to lamp black a more or less pronounced warm brownish hue……”. Although undoubtedly suitable for their intended use as a black pigment, it can be questioned whether these products are representative substitutes for fire-born soot.

Instead of using manufactured carbon black pigments, Ortega-Saez et al. came closer to reality by collecting the soot that accumulated over time inside a domestic wood stove, but reservations can be made regarding reproducibility and the unknown raw materials. Mašková et al. applied PM1 particles collected from outdoor air (suburban environment) which was filtered using a filter device LVS-3 (Sven Leckel). The average mode size of the particles was analyzed to be 0.12 μm, and has organic matters as predominant and EC as the second most abundant, which is reverse for carbon black. In this case, the soot soiling is considered realistic to the carbonaceous particulate from ambient air, but not from fire-born soot65.

Next to the application method and the soot source, it can be questioned if merely bringing carbon black or soot particles in contact with a substrate material is representative enough in the context of comparative cleaning tests for fire-born soot. The adherence of submicron soot particles to a surface is primarily driven by Van der Waal’s forces82 and electrostatic interactions in indoor conditions, while soot nanoparticles can be physically trapped in the microstructure of the substrates as well83. However, in case of instant deposition in the vicinity of an open flame, the temperature can easily increase above the glass transition temperature of a material, making it more likely for soot to attach or become embedded into the surface32. Therefore, several authors experimented with this approach, that we classified as (II) direct/‘hot’ application by combustion. The most obvious way to deposit soot directly from combustion is by moving the sample back and forth over an open flame, such as from a paraffin (or rendered animal fat) candle. Mašková et al., Rutledge et al. employed this method for sooting paper and artistic canvas, respectively65,84. However, since the burning temperature of candle flames is very high (up to around 1700 oC) the samples can be easily burned or damaged, especially for organic materials if the contact time is long85. In addition, due to the fact that the flame can easily flicker under slight movement, Banks et al. discarded this method as insufficiently reproduceable54.

In response, Rutledge et al. went to great lengths by simulating an actual building fire in the training facilities of a fire department73,74. A stack of mattresses soaked with an accelerant solvent were put on fire at one end of a room. Replica rooms were fitted with wooden furniture while paper and straw were added to help spreading the fire. Thermocouples on the walls measured the temperature at various heights. The fire was allowed to burn for about 23 min with wall temperatures not exceeding 177 oC. In the first fire, canvas and acrylic paint samples involved, received a very thin coating of soot, with the thickness increasing for samples that were placed higher/closer to the ceiling. In order to obtain a thicker smoke layer on the surfaces, samples were placed in a stainless box in another fire. A temperature sensor was installed inside the box and connected to a control system that regulated the opening of the lid and a cool air vent. This setup was designed to prevent charring for those sensitive samples, such as textile and paper73,84. The controlled house fire method was also adopted by Mari Grønlund in her master thesis research on solid CO2 blasting on fire-damaged textiles. By spreading samples at different locations, textiles were obtained showing different levels of soot and heat damage (from 130 to 230 oC) in a highly realistic manner11. Tsang et al. worked on acrylic paint samples from a simulated fire, but details on the sample preparation are missing in the paper68. Nevertheless, this simulated structure fire approach seems less feasible for the routine and iterative production of model samples, not only due to the reported variation in homogeneity, but especially in view of sustainability issues and intensive deployment of resources (e.g. support from firefighters). However, the enhanced degree of veracity does make it a potential, one-time validation technique, allowing to benchmark the outcome of systematic mock-up research with a situation that is closer to reality.

Banks et al. recognised the aforementioned limitations and subsequently experimented with the design of a straightforward smoke deposition drum: a metal cylinder container with a burning piece of cotton cloth, soaked in motor oil, on the bottom and a motorized carousel with samples above. The steady rotation of the mock-ups in a horizontal plane resulted in a more homogeneous deposition of soot. In this way, it was feasible to obtain thicker coatings of soot at lower temperatures, without causing thermal damage to the samples, whereas the cloth can be exchanged by any other combustion source54.

Methods

Experimental

Samples were prepared according to the aforementioned methods found in literature, the outcome of the experiments is compared and discussed in the Results section, as shown in Fig. 4.

Preparation of mock-ups

We used furnace black pigment (CAS No. 1333-86-4) from Kremer which has been mostly cited in literature. The pigment was used directly in powder form, or mixed with ethanol to 1% dispersion for the brushing, rolling and spraying applications. Carbon black and lamp black from Natural pigment were analysed and compared to furnace black (Kremer GmbH). A candle (SPAAS) containing paraffin (90−60%) and stearin (10−40%) was used for producing candle soot on glass substrates, and analysed after collection. The black pigments, candle soot and soot from Shellsol D40 were used directly without any further treatment, and analysed using Raman Spectroscopy (RS), XPS, EDS, XRPD and TGA. In total, four types of substrate material including plaster, paper, silk and oil paint were tested as substrates (listed in Table 3). Degummed white silk, known as ‘Pongee 08’ (50 g/m2) was supplied by Ideen company and was used as purchased. According to the description, the silk is boiled off (washed in very hot water) after weaving, and there is no further processing after washing (i.e. no bleaching, soaking, finishing nor surface treatment). Whatman® qualitative filter paper, Grade 1 (WHA1001150) was used as paper substrate. Pre-formulated titanium white oil paint applied on pre-primed cotton canvas with plain weave was provided by our partner at University of Amsterdam. Plaster was prepared using plaster of Paris, CaSO4 hemihydrate at National Gallery of Denmark. All the samples were soiled with the methods described below, and the soiling outcome in terms of the distribution and morphology of soot was observed by means of a 3D digital optical microscope (OM) and the secondary electron images recorded by a scanning electron microscopy (SEM-SE). The weight of the samples was measured with a balance (precision 0.1 mg) before and after soiling at room condition. The thickness of soot on the surface was characterized by OCT (CNR, Italy).

We evaluated six approaches to simulate soot contamination on four types of substrates with details provided in Table 4. Shaking and brushing methods involve only soot powders, whereas rolling and spraying are performed with a soot suspension of 1 w% in ethanol. As soot in reality also contains a certain number of hydrocarbons and other impurities that are not present in this pigment, soot generated from combustion was taken into account and compared with the pigment. We study three pigments: furnace black from Kremer, and carbon black and lamp black from Natural Pigment. For brevity in all figures and tables we use the abbreviations furnace black_Kr, carbon black_NP, and lamp black_NP. We used only the Kremer furnace black for assessing the application methods, which was mostly applied in the literature.

-

1.

Brushing: A brush is dipped into soot powder and the excess amount is shaken off until no aggregates fall down. The sample is brushed in the same direction multiple times until the surface looks homogenously sooted and the blackness ceases to increase. The loose, excess particles are blown from the surface.

-

2.

Shaking: specimens were adhered in the bottom of a 25 × 18 x 15 cm (L x W x H) carboard container with masking tape. Two mg of soot is sprinkled on the surface of the mock-ups and shaken for 2 min to allow the soot to disperse well. After 1 min, the soot is settled down. Samples were removed and the excess soot is blown away.

-

3.

Paint Roller: One mg of soot was suspended in 100 mg ethanol and stirred for 15 min until the 1% solution became homogenous. A foam paint roller was saturated with this dispersion in a tray and excess liquid was squeezed out before applying on the substrate. The solution was rolled on the samples in the same direction for three times with only slight pressure. The movement was repeated to improve the homogeneous distribution. The samples were left to dry in room environment, to allow for ethanol to evaporate.

-

4.

Spraying: A portable airbrush (HBM Portable Rechargeable Airbrush Gun Model 2) with a 0.4 mm nozzle diameter and maximum air flow 7 L/min was loaded with the soot dispersion described above (3). The samples were placed vertically in front and perpendicular to the air flow direction. The instrument was used at maximum flow rate while moving the airbrush in horizontal direction slowly at a constant speed until the whole sample was coated. The diameter of the soiled area is around 3 cm at a nozzle-sample distance of 15 cm approximately. The spraying was repeated three times for each sample and left to dry at room conditions.

-

5.

Candle flame: samples were manually subjected to the middle part – incomplete sooting area of the flame by moving the sample horizontally in one direction and passed. As the temperature in this area is around 1000 oC85., sooting was done in a fast motion to prevent localized over-heating since heat transfer took time, while an attempt was made to keep the speed constant for each movement. The candle was kept in a closed environment to avoid flame flickering. The silk textile fabrics were mounted on glass slides due to their flexibility. However, the deposition of candle soot proved challenging to produce in a spatially homogenous manner.

-

6.

Smoke drum: The soot deposition process involved burning a dense cotton cloth wick soaked in Shellsol D40 (Kremer) liquid. The samples itself were fixed to cardboards as backing measuring 5 × 10 cm, which were attached to a carousel equipped with clamps. To ensure uniform smoke deposition on each sample, the carousel rotated at 17 rpm in a horizontal plane powered by an electric motor, ca. 20 cm above the flame. The entire system was contained within a metal cylinder to reduce flame flickering effects caused by air draft. After completing the sooting process in 30 min, samples were removed from the metal slides and stored in container.

Characterisation Methods

-

1.

Digital 3D optical microscope: an Olympus DSX510 instrument with polarized light was used to observe the surface morphology of fabrics. At least three photos were taken at different areas on each sample.

-

2.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): the morphology of samples was visualized using a JEOL JSM-6010 PLUS/LV. Secondary electron (SE) imaging was used to capture the surface details. Test samples were first coated with a thin layer of gold by means of a JEOL JFC-1300 Auto Fine coater. The SEM images were acquired with an accelerating voltage of 7 kV under low vacuum condition.

-

3.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT): the analysis was performed by CNR-INO (Italy) with a commercial Spectral-Domain OCT device (Ganymede, Thorlabs) featuring a super-luminescent diode light source with centre wavelength: 900 nm and bandwidth: 100 nm, entailing an axial resolution of 3 μm in air. The 18 mm objective effective focal length (EFL) sets a lateral resolution of 4 μm, maximum field of view (FOV) of 6.0 × 6.0 mm2, and imaging depth of 1.9 mm. The OCT detection system incorporates a spectrograph comprising a diffraction grating coupled with a fast camera, achieving a maximum A-scan rate of 248 kHz. The scanning probe integrates a co-aligned pointing camera for precise sample visualization and alignment. The system is equipped with motorized micropositioning stages that provide fine XY translational control (with micrometer-level precision) and sample rotation capability, allowing for optimal positioning and multi-angle examination of specimens. This integrated design facilitates high-resolution volumetric imaging while maintaining operational flexibility for diverse sample geometries. For each sample, two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) OCT datasets were acquired. The acquisition protocol consisted of three XZ cross-sectional tomograms (B-scans) and three XYZ volumetric scans (tomocubes), as shown in the schematic drawing of the microscope slide with the soot layer in Fig. 6a. The 2D cross-sections (XZ = 4.5 × 0.4 mm, pixel size = 0.45 × 1.96 µm) were systematically analyzed by taking six random thickness measurements per section, yielding a total of 18 measurements per sample. These measurements were subsequently used to calculate mean thickness values and corresponding standard deviations (Fig. 6b). The 3D volumetric data (XYZ = 4.5 × 3.5 × 0.4 mm, voxel size = 3 × 3 × 1.96 µm) allowed detailed characterization of the soot layer’s surface morphology (Fig. 6c), providing complementary topographical information to the thickness measurements obtained from 2D sections.

-

4.

X-ray Photoemission Spectroscopy (XPS): a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source (hν = 1486.6 eV) running at 25 W was used to perform XPS surface analysis on a PHI 5000 Versaprobe II spectrometer. For all measurements, a vacuum of at least 10-6 Pa was established. At a take-off angle of 45◦ and a beam size of 100 µm, survey scans and high-resolution spectra (C 1 s, O 1 s, S 1 s) were acquired with pass energies of 187.85 eV (step size = 0.8 eV) and 23.50 eV (step size = 0.1 eV), respectively. Four points were measured for each sample. For elemental analysis, Multipak (v9.6.1) was used with a Shirley background and the respective sensitivity parameters provided by the manufacturer. Multipak was also used for charge correction of the XPS high resolution spectra. The peak of the C 1 s spectra was shifted to 284.50 eV (C-C bond).

-

5.

Raman spectroscopy (RS): a Renishaw inVia™ Qontor® confocal Raman microscope equipped with 100 mW 785 nm and a charged-coupled device (CCD) array detector was used. For all measurements a 1200 l/mm grating was used. The slit width of the Raman spectrometer was set to 65 μm. The laser was attenuated to 0.10 mW at the sample. The laser beam was focused onto the sample surface through a Leica HC PL Fluotar 20x and 0.5 NA objective lens, resulting in a spot size of 1.9 µm. Prior to the analysis the wavenumber was calibrated and verified using an internal silicon standard with a Raman shift at 520.2 ± 0.5 cm-1. A minimum of 4 point spectra were collected per sample with a measuring time of 600 s per spectrum. The spectral range was set to 881 to 1942 cm-1. All data acquisition was performed using the Renishaw WiRE v.5.6 software package. Background subtraction, smoothing and curve fitting were processed by origin9.

-

6.

X-ray Powder diffraction (XRPD): XRPD patterns were collected on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer equipped with an autochanger and LynxEye XE-T Silicon strip Line detector, operated at 40 kV, 30 mA using Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) in Bragg-Brentano geometry. Powdered samples were scanned from 10-70o in 2 theta range with 0.03o step interval and 192 s/step counter time. The patterns were baseline corrected using the Bruker DIFFRAC.EVA software.

-

7.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed using a NETZSCH STA 449 F3 Jupiter® thermal analyzer. Measurements were conducted under air at a heating rate of 10 °C/min from room temperature to 1000°C.

-

8.

Evolved gas analysis-mass spectrometry (EGA-MS): Soot samples were analyzed using Multi-Shot EGA/PY-3030D micro-furnace pyrolyzer (Frontier Laboratories, Japan) coupled to Agilent GC System 8860 with split/splitless injector and a quadrupole Mass Spectrometry detector Agilent 5977 GC/MSD. Mass range of 50 to 600 m/z was used. The interface between the furnace and the GC injector was kept 100 °C above the furnace temperature, to a maximum of 350 °C. The pyrolyzer and mass spectrometer were connected by an Ultra-ALLOY deactivated and uncoated stainless-steel capillary tube (UADTM-2.5 N, 2.5 m x 0.15 mm, Frontier Laboratories, Japan), which was kept at 300 °C. Temperature of the quadrupole analyzer was set to 150°C and of the ion source – to 230 °C. Sample size ranged between 50−100 ug. For the analysis soot sample was placed in the stainless-steel cup and positioned in the furnace chamber. Heating program was set to start at 50°C with consequent heating to 600°C at 10 °C/min heating rate. Helium was utilized as the carrier gas (1 mL/min). Injector was utilized in split mode with ratio of 1:15.

-

9.

Statistical assessment: to assess differences in chemical properties among the different soot types, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)87 was performed after each chemical analysis. Prior to conducting ANOVA, the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were evaluated using Shapiro-Wilk test88 and Levene’s test89, respectively. In cases where these assumptions were not met, the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test, a robust non-parametric alternative to ANOVA90, was applied instead. Both ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis tests were complemented by parametric and non-parametric multiple comparison tests, respectively, such as Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD)91 and Dunn’s tests (the latter with a Bonferroni correction)92. A significance level of α = 0.05 was used for all statistical tests. The detailed results are found in Supplementary Section 5.

a Schematic representation of the microscope slide (3 × 1 cm) with the soot layer indicated in grey. The red arrows and squares indicate the position of the 2D and 3D images, respectively; b detail of a 2D image with the thickness of the soot layer in yellow annotation; c 3D image of square scan on the sample.

Results

Assessment of soot application methods

The application methods found in literature were tested and various aspects of the resulting mock-ups were considered, including (1) reproducibility (amount of soot deposited and layer thickness), (2) morphology, (3) particle size (4) adherence and (5) distribution on surfaces with variable texture. Micrographs collected from the same mockups were collected at higher magnification (x10) using a digital 3D optical microscope and shown in Fig. 7, whereas Fig. 8 displays relevant SEM-SE images at 1000−4000x magnification.

(IA) dry + cold application of soot particles

Brushing and shaking in a container yields less favourable results, especially in terms of distribution. As demonstrated by Fig. 7-A1, B1 ~ B3, the soot tends to aggregate around texture features on the substrate, resulting in accumulations of particles rather than the homogenous, fine distribution that is sought. This is particularly true when brushing on paper and textile fabric where particles amass around the fibers (see Fig. 7-A1, A3), whereas smooth surfaces with a fine and even texture, such as plaster (see Fig. 7-A4) give a more uniform outcome. Due to the 3D weaving structure and the twisted silk fibril, textile fabrics have a larger surface area to make contact with contaminants, as compared to flat surfaces, i.e. paper, plaster and oil paint93. This appears in particular the case for brushing, where a larger amount of particles aggregate on the top of fabrics and along the direction of brushing, while small particles can penetrate in between the overlapping warp and weft thread, or even in between the fibers. Nevertheless, the brushing action spreads the particles over the entire surface, while slightly embedding the powder into the surface texture of the substrate. As seen in Fig. 8-C1, soot was pushed in between and under the threads. Therefore, the particles appear better attached and fall off less easy after sooting, e.g. upon manipulating the mock-up, or when the sample is exposed to ambient air movement. Then again, the manual aspect jeopardizes the reproducibility of this approach as small adjustments in brush handling and soot addition, resulted in a different outcome.

The total amount of soot that eventually remains on the substrate is also difficult to monitor as not all of the (quantified/weighted) soot adheres to the surface. Excess soot either falls off during manipulation or is deliberately blown away after application. Finally, there a practical restrictions associated with these dry+cold methods, especially for shaking in a container, as mounting the substrates inside the box proved challenging. Adhesive tape employed for these purposes can collect part of the soot particles, avoiding them to make contact with the mockup, whereas we did not find a conclusive solution to keep the heavier and porous plaster samples fixed inside the container during shaking. The latter accounts for the missing micrograph in Fig. 7-B4. Although being relatively straightforward methods, and considering that aspects of the process can be further improved, the dry+cold methods were dismissed for comparative cleaning tests in the MOXY project due, at this stage, to their lower distribution homogeneity and reproducibility.

(IB) wet + cold application of soot particles

The use of an ethanol dispersion reduces the tendency of soot aggregation, as can be seen in Fig. 8-C3. Although carbon black is not soluble in ethanol as it is hydrophobic, the high polarity of ethanol allows stronger intermolecular interactions with the particles and meanwhile minimizes the attraction forces among particles. Therefore, the particles can be distributed more evenly in the suspension and have less chance to pile into coarse particles. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S1, soot particles can be trapped on irregular surfaces and in the spaces within and between yarns, in case of textiles. The implementation of a paint roller clearly favours the uniform distribution of the soot throughout the fabric. When using a paint roller, soot in dispersion can be applied on most of the surfaces, except for oil paint that has high hydrophobicity. As demonstrated by Fig. 8-C2, little soot is deposited on the paint surface. In these tests, the roller was moved very gently by hand, avoiding to apply pressure. Nevertheless, this still resulted in a variation of soot deposition. In addition, the head of the roller is a foam, with the pores leaving minute ‘empty spots’ that give rise to a visible pattern. This heterogeneity can be mitigated to some extent by applying multiple layers on top of each other. In general, airbrush results in a higher homogeneity than other cold application methods, whereas the soot is applied in a contact-less way that does not affect the surface structure of the substrate. Airbrush was therefore rated better than the foam roller, as this results in a finer and more even distribution. It offers a higher control of the amount that is deposited, if needed the movement can be controlled by motors to further enhance reproducibility (e.g. CNC airbrushing). However, in our test (see Fig. 7-D1 ~ D4), larger aggregates showed up due to the precipitation of soot in the dispersion and fluctuations in the air flow caused by accumulated particles in the channel that need to be cleaned away regularly. In summary, both rolling and spraying can be effective methods to apply soot homogenously through a suspension on the mock-ups and without altering the substrate structure. Although there is aggregate formation, the outcome is better than brushing or shaking in terms of homogeneity and controllability.

(II) Hot/direct soot application by combustion

Although the aforementioned indirect/cold application methods are practical and safer for the operator than the hot/direct combustion methods, the latter offer clear advantages in terms of representativeness. Real combustion does not only imply a thermal effect, the ensuing soot also has an EC/OC ratio that is closer to soot stemming from structural fires, as explained in the introduction. In addition, the size of soot particles applied by candle or fire drum are substantially finer than those of carbon black pigment. Non-thermal application results in soot particles with a diameter around 0.3 µm, aggregated into coarse particle up to 800 µm (see Fig. 7-B2), while the particles generated by direct combustion approach the nanometer scale, making them challenging to distinguish and measure with a standard, tungsten filament SEM. Figure 8-E3,F3 illustrates how the soot seems to cover the yarns as a uniform layer. This confirms the optical microscope images in Fig. 7-E1 ~ F4, where particles can be hardly distinguished.

In theory, the adhesion between soot and the substrate is an aspect that is of critical importance in the context of comparative cleaning tests. As introduced in Fig. 2, small molecules such as VOCs, polycyclic PAHs generated from the complete combustion area can adhere to the substrates through chemical bonds, and play a role as reactive sites on the substrates and soot particles. The adhesive force between soot and the deposited surface is (partly) related to the particle size and surface area, where smaller particles generated at higher temperature have larger contact area94. Candle soot is produced with the substrate moving swiftly through the flame at a higher temperature than the other methods, whereas the rotating samples inside the soot drum are situated roughly 20 cm above the flame at around 70oC. When considering the cold/indirect methods, carbon black pigments are usually significantly larger as these are commonly produced in an area that is separated from the burning source, where soot particles are quenched and accumulated into larger aggregates.

When describing the adhesive force between soot and the sample, the intermolecular interaction is the total sum of the force between each particle and the sample, including Van der Waals and capillary forces which is neglectable. Finer particles have larger surface-to-volume ratio than coarse aggregates, which leads to a larger value for Fa. As shown in formula (1) for a single particle, Fa is related to Hamaker constant (A), which is determined by the material property and has been proved positively correlated to the graphitization degree of soot. The graphitization degree can be interpreted by G and D band ratio (IG/ID) calculated from Raman spectra, which will be investigated in this paper39.

where A is the Hamaker constant, R is the radius of particle, and D is the distance between particle and the surface.

An important concern with combustion methods was the potential effect of heat towards substrates, especially for organic materials. For the candle flame method, the temperature is too high for organic materials, i.e. paper and protein-based silk fabrics, which can be damaged or burned when moving through the flame. However, silk samples appeared undamaged whereas the soot was distributed homogenously despite the pronounced texture. SEM-SE images show that the soot particles are finer (see Fig. 8-A6 toD6) and therefore allow deeper penetration into the substrate. A soot drum session typically runs for half an hour and temperature close to the sample holder is around 70°C measured with a thermocouple. The microscopic photos confirmed that there is no evident damage to the substrate. From the experiments, we can conclude that the overall best results were obtained with the soot drum method, in particular in terms of reproducibility, the aspect that proved the most challenging for other methods.

Next to the mock-ups, two sets of glass slides were placed into the drum to assist in validating the reproducibility and controllability of this method. However, the thickness of a soot layer is difficult to measure, as (a) it is too thin to be measured by optical microscopic techniques, whereas (b) the layer is easily affected during manipulation or embedding (e.g. cross-sectioning). OCT is a non-contact, interferometric technique for imaging the internal microstructure of moderately scattering and/or absorbing materials. Originally developed for biomedical applications requiring high-resolution cross-sectional analysis, OCT has become established in cultural heritage studies for the measuring of varnish and semi-transparent paint layers, with capabilities for underdrawing visualization in some cases95. In order to evaluate the repeatability between separate soot drum experiments, the sooting experiment was repeated three times for 30 min, resulting in soot layers with comparable thicknesses with an average of 8.1 ± 0.7 μm, calculated from three test results: 7.5 ± 0.7, 7.9 ± 0.6, and 8.9 ± 0.7 μm. The second experiment shows how the soot layer becomes gradually thicker as the exposure time increases, from 7.8 µm to 14.7 µm after 20−60 min (Table 5). From this, we can conclude that the average deposition rate is ca. 0.3 µm/min, but varies from 0.39 at the beginning to 0.25 µm/min towards the end of the experiment, as the amount of hydrocarbon fuel reduces during the burning process. In addition to thickness, the total amount of soot was measured by weight change and the standard derivation is calculated based on three identical glass slides (3 × 1 cm2) exposed in the same drum session. As shown in Fig. 9 and Table 6, in group A, a 30 min drum session was repeated three times and the average mass gain was 0.1259 ± 0.0064 mg per glass slide, corresponded to 0.0420 ± 0.0021 mg/cm2 after 30 min of combustion with a deposition rate of 0.0014 mg/cm2/min. For group B, the mass increased from 0.1000 ± 0.1155 mg, 0.1667 ± 0.0667, to 0.3333 ± 0.2404 for 20 min, 30 min to 60 min exposure time respectively. The mass almost doubled when comparing 1 hand half an hour of exposure. The deposition rate per area for different durations are relatively stable at 0.0018 ± 0.0001 mg/cm2/min. So that we can conclude that the amount of soot can be controlled to some extent by increasing the combustion time. Overall, the smoke drum method is relatively reproducible and controllable within certain limits, offering the most representative method of simulating fire-born soot within the methods reported in literature.

Group A (A1, A2, A3 on the X-axis): the result of three repeated sooting experiments, in which each experiment three glass slides were exposed to combustion for 30 min; Group B (B1, B2, B3 on the X-axis): the result of three sooting experiments with incremental exposure time (20−60 min) to combustion. For each experiment, the mass of three glass slides were measured and the standard derivation are shown in the error bar.

Chemical analysis of soot

In addition to differences in distribution and morphology across application methods, also potential chemical differences between the produced fire born soot and the applied commercial soot were considered. In particular, the aim of the chemical analysis was to assess the potential variation through the carbon and oxygen content, microcrystal structure, and thermal degradation properties. In total, five types of soot were analyzed. In particular, our drum soot was compared with paraffin candle soot (hot/direct methods) and three commercial carbon black pigments (cold/indirect methods): furnace black from Kremer, carbon black NP, lamb black NP as described in the experimental.

Surface properties - XPS

As illustrated by Fig. 10a, the different elements associated core energy levels are identified as C1s, O1s, and other peaks arising from secondary Auger electrons labelled in standard KL format. The atomic content and C/O ratio for all the samples are listed in Table 7. The carbon content ranges from 92.33 ± 1.07% up to 98 ± 0.67%, and oxygen takes up from 1.12 ± 0.62% to 7.61 ± 1.05%. Upon comparing the C/O ratios, the commercial pigments (I. direct/cold method) stand out with a clearly higher C/O ratio than the soot from direct combustion (II. direct/hot methods). Furnace black has the highest ratio of 88, whereas lamp black and carbon black have a similar C/O level at around 48. The soot from direct/hot methods (II), i.e. candle and drum soot, have significantly lower ratios of 26 and 11 respectively. It can be thus concluded that the oxidation degree of drum and candle soot is substantially higher than that of the carbon pigments.

An example of a high-resolution scan over the nominal C1s region for drum soot is shown in Fig. 10b. Each carbon peak was deconvolved in order to extract information on the sp2 and sp3 carbon bonding percentages and oxygen functional groups. In some cases, exclusion of the C = O peak provides a better functional fit (a lower chi-square value), however the FWHM may be too large for the other peaks, e.g C-O, or COOH. After peak deconvolution and fitting process, the C1s peak can be fitted well by seven fitted peaks, including fullerenic, sp3, sp2, C-O, C = O, COOH and π-π* bonds for all samples. The binding energies corresponding to the chemical state and the peak areas are listed in Table 8. The sp2 hybridized carbon corresponds to graphitic carbon within the basal plane, whereas the sp3 hybridized carbon atom is a class of defect that can disrupt the sp2 hybridized network and will require bond terminations other than adjacent π bonded carbon atoms41,96,97,98,99.

In this way, surface analysis by means of XPS demonstrated that drum soot has the highest oxygen content (lowest C/O ratio) introduced by surface functional groups, whereas the deconvoluted C1s spectra indicated the complexity in chemical environment of carbon including sp2, sp3, C-O, C = O, COOH, π-π* and fullerenic that are potentially contained.

Bulk properties - RS and XRPD

Raman spectroscopy is frequently employed for structural investigations of carbon materials100. As illustrated by Fig. 11a, the first-order spectra of soot exhibit two strong overlapping peaks at ~1350 cm-1 and ~1580 cm-1 as D (“Defect”) and G (“Graphite”) bands of the graphite structure. Both the G and the D bands are generally attributed to graphitic sp2 bonded carbon101. As shown in Fig. 11b, the most intensive peak at ~1350 cm−1 is the D1 band that corresponds to a disordered graphitic lattice vibration mode with A1g symmetry. The G band at 1580 cm-1 can be assigned to the vibration of the ideal graphite lattice (E2g symmetry). It exhibits a shoulder at 1620 cm-1 which is the D2 band corresponding to lattice vibration mode. This band D4 has been reported as sp2-sp3 bonds or C–C and C = C stretching vibrations of polyene-like structures for flame soot. The high signal intensity between the two intense peaks is due to another D3 band at 1500 cm-1, which is attributed to the amorphous carbon fraction, consisting of organic molecules, functional groups, and sp2 bonded carbon101,102. Analysis of Raman spectra for each type of soot was done by peak fitting at ~1580, ~1350, ~1620, ~1500 and 1200 cm−1 using a combination of Lorentzian and Gaussian functions listed in Table 9. The original curve was baseline corrected and smoothened for 15 points. The fitting used peak filtering by height 10% which resulted in low Χ2 calculated to be below 2. The G/D ratio indicates the ratio of graphite to the disordered graphite content, where D is the sum of intensity of D1, D3, and D4 bands (see detail in Supplementary Table 1)102,103.

a Raman spectra of five types of soot (785 nm laser attenuated to 0.10 mW at the sample); b fitted curve of drum soot as an example, and other fitted curves can be found in Supplementary Fig. S1; c FWHM of fitted peaks.

It can be interpreted from this that soot has highly disordered graphitic structures due to the presence of amorphous carbon and other potential functional groups or impurities. Soot from hot combustion methods (II) differs significantly from the commercial carbon blacks (I) as the latter display a larger content of ideal graphite structures. As shown in Fig. 11c, the FWHM of the D2 peak for candle and drum soot (211 and 33 cm-1) is much lower than for the carbon black pigments which is around 672 cm-1103. The integrated peak intensity ratio (ID/IG) is widely used to estimate the graphitization degree of soot. ID/IG is linked to the size and defects in the basal plane of the graphene layers, of which the crystalline size (La) can be determined by Tuinstra-Koenig law, by applying the wavelength (λ) of the incident laser as expressed in formula 2102.

The calculated graphitic domain size La for the soot samples was listed in Table 10, based on D/G Raman band ratio ID/IG. A low value of ID/IG is representative of a high graphitization degree104. Also here, we see a distinction between the combustion soot and the pigments, with furnace black as an outlier. The domain size for furnace black is only 8.83 nm, while drum soot has the largest (23.94 nm). Candle soot is only slightly smaller (17.58 nm), whereas the carbon black and lamp black from natural pigments have a similar domain size around 12 nm. In summary, the Raman spectra suggested that the surface of thermal soot (candle and smoke drum) exhibit higher graphitization compared to the commercial carbon black pigments (indirect/cold application), with smoke drum soot showing the highest degree of graphitization based on the lowest ID/IG ratio.

The XRPD patterns of five soot samples are shown in Fig. 12a. Two broad peaks, at 2ϑ = 24.6° and 2ϑ = 43.2°, are observed in all soot types and attributed to the (002) and (100) planes. One additional peak, with a relative weak intensity, appears at around 2ϑ = 52.7° from (004) plane, emerged in the XRPD pattern of lamp black only. The overall broadness and weak intensity of these three peaks indicates that the soot aggregates have a high degree of structural disorder, characteristic of turbostratic graphite-like structures. It was detected that the basal planes of quasi-crystalline domains are parallel but angularly distorted, which is different from pure graphite97,105,106. The intensity of (002) peak and (100) peak of commercial black pigments are much stronger than for candle or drum soot, in which lamp black shows the highest peak intensity and the (100) peak is almost absent for candle and drum soot. For the (002) peak, all samples have a nearly symmetric profile, except for candle soot which is asymmetric and can be deconvoluted into two peaks, i.e. less-developed crystalline carbon (LDCC) and more-developed crystalline carbon (MDCC) at 2θ = 24o and 2θ = 26o respectively107. As shown in Fig. 12b, the (002) peak was subjected to smoothing and then deconvoluted by Gaussian fitting into the LDCC and MDCC fractions. The interlayer spacing d is calculated using Bragg’s law with 2θ and FWHM value obtained from each band.

n is the order of reflection and taken as 1 in the calculation, λ is the wavelength of the incident X-ray beam. The Lc and La values can be calculated by Scherrer’s equation using FWHM of out-of-plane (002) and in-plane (100) peak, respectively. The constant K is set to 0.89 and 1.84 for Lc and La, respectively108. The FWHM value extracted by Gaussian peak fitting and the structure parameters are summarized in Table 11. The crystallite thickness for commercial soot and drum soot are between 14.4 to 16.0 Å. For candle soot, the Lc values were 13.671 Å and 9.502 Å for LDCC and MDCC respectively. The in-plane crystallite size La is from 43.5 to 46.5 Å for the commercial soot. The crystalline index (Xc) is calculated from the peak area over the total area of each curve after Gaussian fitting. In conclusion, the commercial soot types differ from self-made soot, in the sense that carbon black pigments exhibit a much higher crystalline content (from 81.6 to 87.0%), compared to candle and drum soot which are around 52.8%.

In brief, XRPD patterns showed two broad peaks of (002) plane for all soot samples and a (100) plane for commercial soot, indicating turbostratic graphite-like structures with angular distortions. The (100) peak is absent for both candle and drum soot due to a lack of the long-range order. Instead, an asymmetric 002 peak is present for candle soot and attributed to less-developed crystalline carbon (LDCC) and more-developed crystalline carbon (MDCC). The crystallographic parameters including Lc, La and crystallinity were calculated and the results confirmed that drum and candle soot has more amorphous carbon and less crystallinity compared to commercial soot.

Definitions: Xc (%)—crystallinity index, computed as crystalline peak area / total area after baseline removal; 2θ (°)—Bragg angle at peak maximum (Cu Kα, λ = 1.5406 Å); FWHM (°2θ)—full width at half maximum of the fitted band; d002, d100 (Å)—interplanar spacings from Bragg’s law, d = λ/(2 sin θ) with n = 1; Lc (Å)—stacking height (c-axis) from the Scherrer equation on the (002) band, Lc = 0.89 λ/(β cos θ); La (Å)—in-plane crystallite size from Scherrer on the (100) band, La = 1.84 λ/(β cos θ); β is the FWHM in radians. “/” denotes that the (100) reflection was not observed for candle and drum soot.

The thermal property of the soot samples was characterized by TGA and confirmed the clear distinction between drum soot and the other pigments. As shown in Fig. 13a, b and Table 12, the moisture content of drum soot is higher than the other three pigments, where 1 w% mass loss happened at 49.4 °C which is much lower than the others. Under air condition, the onset (Tonset) and thermal degradation temperature at maximum rate (Tmax) for drum soot are lower at 568.3 °C and 669.4 °C, respectively. In contrast, Tonset and Tmax are around 655.8 ( ± 4.6 °C) and 733.5 ( ± 10.9 °C) respectively for the other types of soot. The lower Tonset and Tmax values of drum soot suggest that it has a less thermally stable structure and therefore a higher oxidative reactivity, due to a higher content of oxygen content, as indicated by XPS.

Samples were analysed also with EGA-MS to gain molecular insights into the differences between the black pigments and soot. The black pigments present similar thermograms and mass spectral features (Fig. 14). Upon heating, two main thermal degradative regions are observed. The first one peaks at around 150°C, and is due to the volatilization of xylene and other aromatic species. The second one peaks at around 450°C, and the mass spectra of molecules evolving in this region present the typical features of aromatic species, indicating that it derives from the thermal decomposition of complex amorphous organic carbon with a high degree of aromaticity.

extracted ion thermograms of relevant fragment ions. Mass spectra associated to the main thermos-degradative regions are reported in Supplementary Fig. S4.

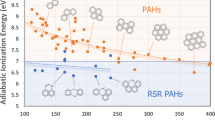

As also highlighted by TG analyses, candle and drum soot are quite different from the black pigments. All types of soot present two main thermal degradative regions. The second region peaks at about 400°C, and the mass spectra associated with this region indicate that – as in the case of black pigments – it can be associated with the thermal decomposition of complex amorphous organic carbon with a high degree of aromaticity. The first region differs between samples. Candle soot shows the evolution of aromatic species around 160°C, with mass spectra consistent with aromatic compounds including alkyl-substituted biphenyls. Drum soot shows the evolution of condensed polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), among which the most abundant species typically consist of two to four fused aromatic rings. Low temperature drum soot yields a relatively higher amount of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons with respect to high temperature drum soot.

EGA-MS data confirm that soot samples have a higher molecular heterogeneity than the black pigments. Moreover, they contain relatively low molecular weight aromatic species which are very scarce in black pigments.

Discussion

This study looked extensively into the reproduction of soot in the context of comparative cleaning tests by identifying, classifying, replicating and evaluating the various methods for applying soot on mock-ups, that were found in heritage science and conservation literature. To do so, paper, paint, silk and plaster substrates were subjected to these methods that were classified in (I) indirect/cold methods and (II) hot/direct methods. The ensuing model samples were compared in terms of practicality, accessibility, controllability and reproducibility of the procedure, whereas the distribution, layer thickness, surface morphology and particle size of the soot was assessed. The Minicast aerosol generator as well as controlled house fires at fire brigade training grounds were not considered as these methods were inaccessible during this study or, as for the latter, were deemed unsustainable and impractical. In general, prefabricated soot (I) displayed significantly different characteristics from direct combustion soot (II), to such an extent that it is questionable whether the indirect/cold methods are sufficiently representative for comparative cleaning treatments.

Among the tested application methods, the home-built smoke drum with rotating sample carousel appeared to provide the best alternative to mimic soot deposited on cultural heritage objects during wildfires or house fires. In particular, the soot nanoparticles generated from combustion of Shellsol D40 and candle flame are significantly finer than the black pigments which are in micrometers range. In particular, indirect/cold methods resulted in soot aggregates with a wide distribution of particle size ca. 0.3 up to 800 µm, while direct combustion methods produced particles in the nano-scale range without big aggregation, spreading more homogeneously over the surface, penetrating deeper into the texture of the substrate. Digital 3D OM and SEM-SE images demonstrated that this smoke drum setup results in a more homogenous distribution of the contamination on all substrates, but also allowed controlling the soot amount and thickness which was non-invasively measured on glass slides by OCT. These experiments demonstrated a certain degree of reproducibility and controllability allowing soot to be produced with a relatively constant amount and thickness.

The chemical and microstructure profile of different types of soot was characterized using XPS, Raman, XRPD, TGA and EGA-MS techniques and indicated a significant difference between the thermal soot (II) and commercial carbon black pigments (I). Raman spectra indicated that soot from the direct/hot methods (i.e. smoke drum and candle) exhibited higher graphitization (lower ID/IG ratio) compared to the commercial carbon blacks. XPS analysis also revealed a substantially higher oxidation level (lower C/O) in drum and candle soot, attributed to more oxygen-containing functional groups, while XRPD revealed a higher disorder at a larger-scale in the bulk of thermal soot types. These findings are further supported by EGA-MS results, which confirm greater molecular heterogeneity and higher levels of low molecular weight aromatic species in thermal soot compared to black pigments.

Our analysis confirmed that thermally generated soot differs from other soot types, characterized by higher surface graphitization together with greater bulk-scale disorder and defect density. Accordingly, we conclude that the smoke-drum method is the most reliable and reproducible approach for simulating soot contamination representative of open fires. This controlled design enables side-by-side benchmarking of cleaning approaches under identical contamination loads and provides ground truth for interpreting XPS, Raman, FTIR, and colorimetric data. It also establishes a reproducible reference that other labs can replicate, improving inter-laboratory comparability and accelerating consensus on safe operating windows. Consequently, we adopted it within MOXY to reproduce fire-borne soot and anticipate that it will be a valuable platform for future cleaning tests in cultural heritage conservation.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Change history

03 December 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-02224-6

References

Zolli, D. M. & Jacobi, L. Contamination and Purity in Early Modern Art and Architecture Vol, 368 (Amsterdam University Press, 2021).

Van Grieken, R., Delalieux, F. & Gysels, K. Cultural heritage and the environment. Pure Appl. Chem. 70, 2327–2331 (1998).

Lombardo, T. et al. Characterisation of particulate matter deposition inducing soiling of modern glass. In Air Pollution and Cultural Heritage (ed. C. Saiz-Jimenez) 209–214 (A.A. Balkema, Lisse, 2004).

Di Turo, F. et al. Impacts of air pollution on cultural heritage corrosion at European level: what has been achieved and what are the future scenarios. Environ. Pollut. 218, 586–594 (2016).

Spezzano, P. Mapping the susceptibility of UNESCO World Cultural Heritage sites in Europe to ambient (outdoor) air pollution. Sci. Total Environ. 754, 142345 (2021).

Wilczynska-Michalik, W. Air pollution and damages to cultural heritage in cities: the decay of the cultural heritage in Krakow. In Urban Environmental Management: Reports from the SUPERBS Project (ed. L. Rydén) 42–53 (Baltic University Press, 2003).

Lamhasni, T. et al. Air pollution impact on architectural heritage of Morocco: Combination of synchronous fluorescence and ATR-FTIR spectroscopies for the analyses of black crusts deposits. Chemosphere 225, 517–523 (2019).

Gomez-Heras, M., McCabe, S., Smith, B. J. & Fort, R. Impacts of fire on stone-built heritage: an overview. J. Archit. Conserv. 15, 47–58 (2009).

Australian War Memorial. Conservation: Soot.https://www.awm.gov.au/about/our-work/projects/conservation/soot (2019).

Bellan, L. M., Salmon, L. G. & Cass, G. R. A study on the human ability to detect soot deposition onto works of art. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34, 1946–1952 (2000).

Grønlund, M. An Evaluation Of Solid Carbon Dioxide (Co2) Blasting As A Cleaning Method To Remove Soot From Textiles After Smouldering Fire And Fire, With The Possibility To Transfer The Method To Historical Textiles Within A Museum Context. https://journals.openedition.org/ceroart/4277 (2014).

Northeast Document Conservation Center. Preservation leaflets 7.2: Surface cleaning of paper.https://www.nedcc.org/free-resources/preservation-leaflets/7.-conservation-procedures/7.2-surface-cleaning-of-paper (2018).

Huber, K. Resilience Strategies for Wildfire. https://www.c2es.org/document/resilience-strategies-for-wildfire/ (2018).

European Commission’s Joint Research Centre.Wildfires in the Mediterranean: EFFIS Data Reveal the Extent of Summer 2023.https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/jrc-news-and-updates/wildfires-mediterranean-effis-data-reveal-extent-summer-2023-09-08_en(2023).

Ho, K. K. Wildfires in Maui Destroy Cultural Heritage Sites, Raising Alarm Among Experts. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/wildfires-maui-hawaii-destroy-cultural-heritage-sites-1234676951/ (2023).

Grau-Bové, J. & Strlič, M. Fine particulate matter in indoor cultural heritage: a literature review. Herit. Sci. 1, 8 (2013).

Baumgardner, D. et al. Soot reference materials for instrument calibration and intercomparisons: a workshop summary with recommendations. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 5, 1869–1887 (2012).

Watt, J., Tidblad, J., Kucera, V. & Hamilton, R. The Effects of Air Pollution on Cultural Heritage 1st edn, Vol. 306 (Springer, 2009).

Krupińska, B., Van Grieken, R. & De Wael, K. Air quality monitoring in a museum for preventive conservation: Results of a three-year study in the Plantin-Moretus Museum in Antwerp, Belgium. Microchem. J. 110, 350–360 (2013).

Islam, N. & Saikia, B. K. An overview on atmospheric carbonaceous particulate matter into carbon nanomaterials: a new approach for air pollution mitigation. Chemosphere 303, 135027 (2022).

Long, C. M., Nascarella, M. A. & Valberg, P. A. Carbon black vs. black carbon and other airborne materials containing elemental carbon: physical and chemical distinctions. Environ. Pollut. 181, 271–286 (2013).

Li, R., Han, Y., Wang, L., Shang, Y. & Chen, Y. Differences in oxidative potential of black carbon from three combustion emission sources in China. J. Environ. Manag. 240, 57–65 (2019).

Huang, H. et al. On-road emissions of fine particles and associated chemical components from motor vehicles in Wuhan, China. Environ. Res. 210, 112900 (2022).

Comite, V. et al. The impact of atmospheric pollution on outdoor cultural heritage: an analytic methodology for the characterization of the carbonaceous fraction in black crusts present on stone surfaces. Environ. Res. 201, 111565 (2021).

Lazaridis, M., Katsivela, E., Kopanakis, I., Raisi, L. & Panagiaris, G. Indoor/outdoor particulate matter concentrations and microbial load in cultural heritage collections. Herit. Sci. 3, 34 (2015).

Anaf, W., Bencs, L., Van Grieken, R., Janssens, K. & De Wael, K. Indoor particulate matter in four Belgian heritage sites: case studies on the deposition of dark-colored and hygroscopic particles. Sci. Total Environ. 506-507, 361–368 (2015).

Falk, M. T. & Hagsten, E. Assessing different measures of fire risk for Cultural World Heritage sites. Herit. Sci. 11, 189 (2023).

Delegou, E. T. et al. The effect of fire on building materials: the case-study of the varnakova monastery cells in central Greece. Heritage 2, 1233–1259 (2019).

Zhu, R., Wang, H., Wang, X. & Liu, H. Standard source of atmospheric black carbon aerosol generated from ultrasonic spray of BC suspension. Atmos. Meas. Tech. Discuss. 2017, 1–12 (2017).

Knoche, M. The herzogin anna amalia library after the fire. IFLA J. 31, 90–92 (2005).

Jacobson, R. S., Korte, A. R., Vertes, A. & Miller, J. H. The molecular composition of soot. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 4484–4490 (2020).