Abstract

The risks of aging, damage, and disappearance of ancient buildings are becoming increasingly severe. Three-dimensional digital technology is increasingly crucial for their protection, restoration, and research. Addressing the low efficiency and poor accuracy of point cloud segmentation in the digital conservation of ancient wooden components, this paper proposes an innovative method that integrates traditional construction knowledge with modern point cloud processing techniques. First, based on construction techniques, we summarize a section acquisition method constrained by the rules of large timber joinery in ancient buildings. Second, we propose a method for extracting component segmentation parameters by fusing Euclidean clustering with construction knowledge, analyzing sectional point cloud data to obtain relevant parameters. Finally, by combining pass-through filtering and region-growing algorithms and utilizing the obtained parameters, this method achieves efficient and high-precision segmentation of components.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ancient architecture can be broadly divided into seven major systems. Among them, Chinese and European architectures have consistently shone throughout history. Distinct from other systems, Chinese ancient architecture developed a timber-frame-based structural system shaped by diverse geographical and cultural factors, a unique patriarchal clan system, and specific moral concepts. As an integral part of Chinese civilization, these structures carry rich historical, cultural, and artistic values. They not only testify to ancient building technologies and craftsmanship but also reflect the social, political, and cultural characteristics of different historical periods. Thus, preserving ancient Chinese architecture is both a tribute to traditional culture and a vital means of transmitting historical memory. However, with the passage of time and changes in the natural environment, these buildings face risks of gradual aging, damage, and even disappearance. According to the third national cultural-heritage survey, China has registered approximately 766,700 immovable cultural relics. Among them, 17.77% are in relatively poor condition, and 8.43% are in poor condition; nearly 50% are timber structures. Effective protective measures for these ancient buildings are therefore urgently needed.

To address this challenge, in recent years, the rapid advancement of three-dimensional (3D) digital technology has established techniques such as 3D scanning, modeling, and visualization as vital tools for ancient architectural conservation. An increasing number of historical structures are being incorporated into digital preservation initiatives, and the associated technologies are continuously being optimized and refined. From laser scanning and photogrammetry to high-precision modeling, modern digital methods enable the accurate capture of geometric forms and surface characteristics of ancient buildings1. Through precise digital documentation, every detail of these structures can be meticulously recorded and preserved. This provides a scientific basis for subsequent restoration work while simultaneously offering researchers a convenient digital platform for the presentation and analysis of these architectural artifacts. Consequently, 3D digital technology plays an increasingly critical role in the protection, restoration, and research of ancient architecture.

Currently, within the domain of digital preservation technologies for ancient architecture, component individualization based on holistic 3D-scanned point clouds constitutes a critical procedure. This process entails isolating and processing each independent structural element separately from the integrated model, which is essential for enabling precise analysis, restoration, and conservation. For example, finite element analysis (FEA) may be applied to standardized models derived from individualized components to investigate their internal forces and deformation characteristics under self-weight, wind loads, or seismic actions, thereby evaluating the current structural safety status2. Additionally, deformation parameters extracted from individualized elements facilitate safety assessments of heritage structures and support the formulation of targeted preservation strategies. Consequently, point cloud individualization for ancient buildings serves not only as a pivotal measure for preventive conservation but also significantly enhances the precision and efficiency of restoration workflows, while simultaneously functioning as an indispensable instrument for elucidating the architectural chronology and cultural significance embedded within these structures.

Point cloud-based individual segmentation of ancient architectural components refers to the process of classifying and partitioning scanned objects based on their spatial characteristics, such as geometric shapes and textures, while grouping points with similar features into the same category. In recent years, significant progress has been achieved in research on individual segmentation of ancient architectural components, with two main technical approaches emerging: deep learning-based point cloud segmentation and traditional point cloud segmentation3.

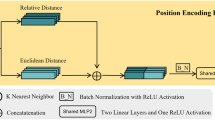

Recent deep learning methods for LiDAR point cloud processing can be primarily categorized into several types: point convolution methods4, multilayer perceptron (MLP)-based methods5, graph-based methods6, RNN-based methods7, and attention mechanism-based methods8. Advanced models such as the PointNet network9 and dynamic graph convolutional neural networks (DGCNN)10 are widely used for the semantic segmentation of LiDAR point cloud data11. They exhibit excellent performance in distinguishing ‘buildings’ from ‘non-buildings’ (such as ground, vegetation). Although these methods are effective for macroscopic semantic segmentation, they have limitations in extracting local features. Further, precisely clustering individual building instance components remains a major challenge. Although strategies such as incorporating attention mechanisms12, hybrid architectures13, and weakly supervised learning14 have been introduced to continuously optimize performance, the problem of misclassification in semantic segmentation due to shape similarities persists. Qiu et al. proposed using YOLOv8 for object detection and instance segmentation tasks15, but the various issues present in traditional architectural roofs are highly complex. These issues are not fully covered by existing datasets, leading to data scarcity challenges. Given that ancient structures are characterized by complex structures, numerous components, diverse architectural styles, and distinct features, the decision-making processes of many deep learning models lack transparency, posing problems of interpretability and explainability. Although deep learning has achieved significant success in many fields, it remains an immature technology in the field of ancient architectural segmentation, still facing numerous challenges and limitations.

Traditional point cloud segmentation methods approach the 3D segmentation problem as structural object detection, primarily relying on point cloud geometric features. These methods can be classified into three categories: RANSAC-based model fitting methods, clustering-based methods, and region-growing methods.

The random sample consensus (RANSAC) method was initially proposed by Fischler and Bolles16 in 1981, which employs a probabilistic approach to estimate models using minimal required point sets. The RANSAC algorithm has been applied to historic building segmentation, generating point cloud subsets corresponding to architectural components. Kivilcim and Duran successfully extracted geometric representations of façade elements from noisy airborne and terrestrial LiDAR data using this approach17. Similarly, Li and Shan employed the RANSAC algorithm to identify and extract multiple primitive shapes or structures that collectively represent a building18.

Clustering-based approaches aggregate points whose normal vectors and spatial positions are mutually proximal. For instance, Xu et al. employed an enhanced density-based clustering algorithm to group points, thereby facilitating the identification and planar fitting of point-cloud facets19. Saglam et al. utilized K-means clustering to partition the point cloud into blocks, which were subsequently refined into planar segments20. Predicated solely on spatial proximity or on the joint consideration of normal orientations, these methods typically necessitate an additional secondary segmentation stage.

The region-growing algorithm proposed by Besl and Jain in 1988 represents another clustering-based planar segmentation approach capable of simultaneously incorporating both spatial and normal vector information21. Grussenmeyer et al. specifically selected the centroid of each voxel cell as seed points for region growing, subsequently extracting planar surfaces from TLS point clouds of medieval castles for parametric modeling22. While region-growing methods have demonstrated efficacy in segmenting point cloud data from ancient historical structures, their performance remains constrained by seed point selection strategies23.

Moreover, hybrid methods that integrate various traditional point cloud segmentation techniques have emerged as a promising strategy to enhance segmentation performance. For instance, Sheng et al. combined RANSAC-extracted planes with the K-means clustering algorithm, where Euclidean distances between fitted surfaces and random spatial points were computed to identify coherent groups, thereby successfully segmenting walls and floors24. Adam et al. introduced a hybrid segmentation method for coplanar objects, leveraging both structural information from 3D point clouds and visual cues from 2D images, augmented by RANSAC plane fitting25. Similarly, Pérez-Sinticala et al. employed a hybrid region-growing algorithm enhanced with RANSAC-based primitive fitting to reduce point clouds into simplified geometric representations26. For heritage applications, Paiva et al. extracted planar elements from point clouds of historical buildings spanning five architectural styles and periods27. Their approach integrated hierarchical watershed transformation, curvature analysis, and region growing to optimize seed selection, demonstrating compatibility with multi-source point clouds from both UAV and terrestrial laser scanners. More recently, Ling et al. proposed a method combining region growing and RANSAC for stair segmentation, addressing efficiency limitations of conventional region growing and inaccuracies in RANSAC-based plane extraction28. However, the least-squares fitting process exhibited sensitivity to noise, resulting in parametric deviations and erroneous planar segmentation. Another advancement was made by Jiang et al. with a hybrid framework incorporating region growing, statistical filtering, and least-squares fitting29. While their case study on the Shandong Theater demonstrated successful segmentation of simple geometric elements (e.g., columns), the method struggled with intricate structural connections, warranting further refinement for complex architectural components.

In summary, current methods for segmenting individual components of historic timber structures face significant challenges, including inaccurate point cloud segmentation, low precision, and difficulties in processing geometrically complex models. To address these limitations, this study proposes a novel methodology that integrates traditional architectural knowledge with hybrid point cloud processing algorithms. The approach involves systematically extracting and formalizing structural knowledge from classical construction treatises, with particular attention to component joint configurations and spatial relationships. This domain-specific knowledge is then combined with optimized point cloud segmentation techniques to achieve precise individualization of primary structural members (columns, beams, and architrave components). The developed framework effectively resolves the critical technical bottleneck of accurately segmenting large timber elements from dense point cloud data. The resulting segmented models provide fundamental data support for historic building research and conservation30, while offering technical solutions for three key aspects of cultural heritage management: precision restoration, interpretive reconstruction, and sustainable digital preservation.

Methods

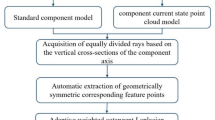

Addressing the challenges of complex model component individualization, segmentation, and low segmentation accuracy in ancient building point clouds, this paper classifies and synthesizes wooden components to investigate their structural principles. Building upon this foundation, we propose an individualization segmentation framework that integrates traditional construction knowledge with a hybrid point cloud segmentation algorithm. The overall technical approach is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Firstly, segmentation sections for the ancient building point cloud are determined based on joinery locations and construction principles, structurally extracting sectional feature maps. Subsequently, combining traditional construction knowledge—such as the Doukou module system from the Engineering Practice Rules—with an improved Euclidean clustering algorithm (including two-stage clustering and construction-knowledge-constrained clustering), we develop a parameter extraction method for individualization. This method acquires segmentation parameters for distinct sectional feature point clouds from the perspective of joinery patterns. Finally, employing the obtained component segmentation parameters and construction knowledge, component individualization is performed using a bounding box algorithm constructed via a pass-through filter and a region-growing algorithm.

Section positioning via traditional construction knowledge

Overview of ancient building structural systems

Ancient architecture can be broadly categorized into seven distinct systems. Throughout architectural history, the Chinese and European systems have emerged as the most prominent. The Chinese architectural tradition differs significantly from other systems, primarily manifested in its unique geographical and cultural context, specific patriarchal clan system, and profound ethical doctrines. These factors collectively shaped a construction system fundamentally based on large timber structures. This defining characteristic establishes ancient Chinese architecture with a distinctive position in the history of world architecture.

Chinese ancient timber architecture has evolved from prehistoric times to the present, culminating in three distinct structural systems: post and lintel, column and tie, and log cabin, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Post and lintel construction represents the most widely distributed structural system within Chinese ancient timber architecture. Its derived architectural forms exhibit significant diversity, predominantly employed in large-scale structures such as palaces, altars, temples, and monasteries. Despite the variety of architectural styles, these forms adhere to specific rules and principles, demonstrating consistent patterns of regularity. This system has evolved into a comprehensive craftsmanship framework. Structurally, the post and lintel construction is characterized by the sequential layering of beams atop columns, followed by the placement of short columns upon these beams, and subsequently shorter beams upon the short columns. This layering progresses progressively until reaching the ridge purlin. Beams are interconnected at their ends by purlins to support the roof structure. Based on distinct roof configurations, the post and lintel construction can be categorized into five primary types: hip roof, gable-and-hip roof, pyramidal roof, overhanging gable roof, and flush gable roof, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

The column and tie construction is predominantly employed in vernacular dwellings and smaller-scale buildings. It is characterized by relatively slender and densely spaced columns. The roof load is transferred directly from the purlins to the columns, eliminating the need for large horizontal beams.

The log cabin construction represents a distinctive form of building construction that dispenses with the need for vertical columns and horizontal beams. Its structural configuration is relatively straightforward, consequently facilitating ease of construction. However, due to its rudimentary nature and substantial timber consumption, its application remains relatively limited. It is primarily suitable for forested regions or colder climates/predominantly employed in heavily forested areas or regions experiencing colder climates.

This study focuses on post-and-lintel architecture as the primary research subject, conducting an in-depth structural analysis and synthesis of these ancient buildings. This focus stems from the fact that the classification of post-and-lintel structures is predominantly determined by variations in roof configuration, whereas the structural components beneath the roof exhibit relative consistency, demonstrating unified construction characteristics.

This uniformity is manifested not only in the overall architectural layout but also in the proportional relationships between different building elements. Adherence to specific proportional and constructional requirements for individual components constitutes a fundamental principle that must govern the design and construction of ancient architecture, ensuring both structural soundness and esthetic harmony.

Joinery principles and section positioning

Through the analysis of roof configurations, preliminary identification of an ancient building’s fundamental typology can be achieved, thereby enabling deeper comprehension of the structural distinctions between different architectural forms. This paper synthesizes common structural patterns, leveraging joinery principles and the inherent symmetry of ancient buildings to determine section positioning.

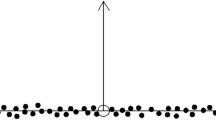

This study adopts the large timber assembly sequence—specifically, “interior before exterior, lower before upper”—to determine section cuts. For instance, in a structure with four rows of columns (two hypostyle columns and two peripheral eave columns, the inner hypostyle columns and their interconnecting members are erected first, followed by the peripheral eave columns and their linking components. Where multiple horizontal or vertical members connect adjacent columns, the lower and intermediate members must be installed prior to the upper ones; reversal of this sequence is structurally non-compliant. Within the large timber framework, components below the column capitals constitute the “lower framework”, while those above form the “upper framework”. Installation of upper framework members commences only after the lower framework assembly is complete. The following demonstrates this methodology using a six-row column structure with a peripheral corridor. For structures without peripheral corridors, the section cut position undergoes a translational adjustment while maintaining identical procedural rigor.

First section: Transverse cross-section at the mid-span of the column grid (section location indicated by the green area in Fig. 4).

This transverse section was acquired from the central region of the overall point cloud dataset. This location selection offers two advantages: it minimizes interference from cluttered points while simultaneously ensuring the acquisition of comprehensive column cross-sectional information. Key parameters (e.g., column center coordinates and radii) were extracted directly as a result of the cross-sectioning.

Traditional construction knowledge application: In traditional Chinese timber structures: Bay direction (building facade width): Features a higher column density with larger intercolumniation. Depth direction (depth perpendicular to facade, aligned with beam direction): Exhibits fewer columns with reduced intercolumn spacing.

Based on the column point cloud distribution within the cross-section, the two primary axes of the column grid are identified as the bay direction and depth direction. These spatial parameters constitute essential prerequisites not only for column individualization but also for subsequent longitudinal section extraction between columns.

Section 2: Longitudinal section through inner hypostyle columns along the depth direction (section location indicated by the red area in Fig. 5).

Structural assembly sequence: Following column erection, ceiling beam connections (5) are installed, adhering to the “interior-before-exterior” principle.

Data acquisition rationale: A global longitudinal section acquired along the depth direction at the inner hypostyle column positions enables extraction of critical height parameters: outer hypostyle column (2), inner hypostyle column (3), short post height (4), penetrating tie beam (6), corner beam (7), double-step beam (11), single-step beam (12), and beam (13)–(15).

These parameters facilitate component individualization. Directional distinction: The ceiling beam aligns parallel to the depth direction. At equivalent elevations, bay-directional members are designated ceiling tie beams.

Section 3: Longitudinal section along the eave column grid axis (section location indicated by the orange area in Fig. 6).

Construction sequence: Following the installation of the penetrating tie beams and corner beams, the architraves were subsequently installed between the eave columns.

Data acquisition and analysis: A longitudinal section was acquired along the Bay Direction (perpendicular to depth direction), positioned centrally between the longitudinal grid axes of the eave columns within the overall point cloud dataset. This sectioning enabled the extraction and subsequent analysis of critical dimensional and positional parameters for: Architraves (8) and (9), Dougong bracketing clusters (10).

Section 4: Longitudinal section of the outer hypostyle column axial plane (section location indicated by the blue area in Fig. 7).

Construction sequence and structural logic: The installation of the primary timber framework constitutes the final structural phase prior to decorative elements. The facade design of palace buildings exhibits bilateral symmetry, featuring door and window openings positioned between peripheral hypostyle columns. Masonry infill walls are strategically arranged along these columns to provide essential lateral support.

Data acquisition method: A longitudinal section was acquired across the longitudinal plane defined by the outer hypostyle columns within the overall point cloud dataset. This sectioning plane was oriented either parallel to the depth direction or the Bay direction, depending on the specific facade under investigation.

Data utility: This longitudinal sectioning methodology enables the extraction and documentation of critical dimensional parameters pertaining to door and window openings, as well as the adjacent masonry infill wall panels.

Parameter derivation via Euclidean clustering algorithm for individual component segmentation

Building upon the acquisition of key sectional point clouds through traditional construction knowledge (incorporating structural attributes and assembly sequences), this chapter employs point cloud processing algorithms to derive component-specific parameters from these profiles. For the first section (column grid cross-section): A dual-stage clustering approach addresses the challenge of extracting centroid coordinates and radii from composite column point clouds. For the remaining three sections: Leveraging predetermined column parameters and spatial distribution, construction-knowledge-constrained clustering obtains component individualization parameters, resolving segmentation parameter acquisition. Subsequent subsections elaborate on these methodologies in detail as follows.

Dual-stage clustering algorithm for individualized parameter extraction in transverse profiles

Column structures within ancient building point clouds manifest two primary typologies: discrete column structures and interconnected column structures. Discrete columns, exemplified by pavilion supports, typically stand independently—open on all sides and structurally isolated. Conversely, interconnected columns exhibit extensive fusion with adjacent components (e.g., walls, door/window frames), resulting in blurred boundaries, geometric incompleteness, and significant extraction challenges. To address complex interconnected column configurations, this paper proposes a dual-stage clustering algorithm for processing column grid cross-sectional point clouds. This methodology resolves the critical challenge of extracting centroid coordinates and radius from composite point clouds encompassing columns fused with wall and fenestration structures. The technical workflow is illustrated in Fig. 8.

For complex column point clouds, Stage 1 acquires parameters for discrete column sections:

Euclidean clustering for isolated column point clouds: This algorithm iteratively partitions the dataset into K distinct clusters by assigning each point to the nearest cluster centroid based on Euclidean distance metrics. The resultant classification is schematically represented in Fig. 9.

The Euclidean clustering algorithm can be formally represented as follows:

The mathematical representation comprises: \(S=\{{S}_{1},\,{S}_{2},\,{......,S}_{k}\}\): Clustered partition of data points, \({\mu }_{i}\): Centroid of the ith cluster,\(\,{N}_{max}\): cardinality of cross-sectional point clouds.

Given that cross-sectional point clouds interfacing with door/window frames substantially exceed discrete column sections in density—and considering traditional post-and-lintel structures typically feature ≤9 column rows—the clustering parameters are constrained as

Maximum cluster size: Nmax/9

Minimum cluster size: 50

This dual-threshold configuration efficiently eliminates sparse noise points and column points fused with fenestration elements while isolating all discrete columnar features. Consequently, it achieves optimal distance-threshold convergence at 1.5× the point cloud density spacing (empirically validated through iterative trials), thereby rendering Euclidean clustering highly effective for heritage structural parameter extraction. Figure 10 (highlighted in blue) visualizes the isolated column clusters obtained during Phase-1 processing.

Parametric extraction via 2D circle fitting to isolated column point clouds: Upon completion of Euclidean clustering, the cardinality (point count) of each cluster is outputted. Subsequently, for each clustered point cloud, this study employs a RANSAC-based 2D circle fitting method to robustly extract its geometric parameters from data that may contain noise and a small number of non-columnar outliers. This method projects the column’s cross-sectional point cloud onto a 2D plane and finds the optimal circle model through the following iterative process:

Model hypothesis: Three non-collinear points are randomly selected from the 2D point cloud dataset. As three points define a circle, these 3 points form a minimal sample set used to generate a candidate circle model.

Model parameter calculation: Based on the 3 selected points, the centroid coordinates (h, k) and radius r of the candidate circle are precisely calculated.

Consensus set validation: A distance threshold is set based on the average density of the point cloud, which is set to 0.01 in this paper. The algorithm iterates through all points in the dataset, calculating the perpendicular distance of each point to the generated candidate circle’s circumference. If this distance is less than the threshold, the point is classified as an “inlier,” i.e., a point that supports the current model.

Iteration and evaluation: The above steps are repeated for N iterations. In each iteration, the number of inliers obtained by the current model is recorded.

Optimal model selection: After N iterations, the candidate circle model supported by the largest number of inliers is selected as the optimal model. The inlier set of this model is considered to best represent the true column cross-section, yielding more precise centroid coordinates and radius. The formula is as follows:

For a given dataset \({\{{p}_{i}\}}_{i=1}^{N}\) where each point \({p}_{i}=({x}_{i},{y}_{i})\), the procedure is formalized as follows: Three points\({p}_{1},{p}_{2},{p}_{3}\), are randomly sampled to instantiate a circle hypothesis. Let \((h,k)\) denote the circle’s centroid coordinates and r its radius. Let \({d}_{i}\) denote the orthogonal distance from point \({p}_{i}\) to the fitted circle; it serves as an inlier–outlier discriminator. If \({d}_{i}\) falls below a predefined threshold, \({p}_{i}\) is classified as an inlier. The average radius of the isolated column point cloud is subsequently computed and recorded.

Phase 2: Parametric acquisition for composite column point clouds: When processing the composite point clouds, in order to separate the column cross-section point cloud portion from the data extensively fused with components such as doors, windows, and walls, this study adopts a multi-directional pass-through filtering strategy constrained by principal axis directions. First, we define the “principal axes,” which are determined according to the main horizontal extension direction of the wall or fenestration components connected to the columns. The specific implementation of this strategy is as follows:

Euclidean clustering of door-column integrated structures: Owing to the significantly larger cardinality of the composite cluster relative to isolated column cross-sections, the minimum cluster size for the second stage is set to twice the point count of the largest cluster identified in the first stage. Consequently, the algorithm successfully isolates the column-door/window composite cluster, highlighted in yellow in Fig. 11.

Boundary parameter extraction for connected column point clouds: Compute the minimum and maximum coordinate values of the composite point cloud along the X, Y, and Z axes. These extrema define the bounding values of the integrated structure.

Point cloud extraction via pass-through filtering: Utilizing the pass-through filtering algorithm, extract point clouds within a range of 1.0–1.5 times the radius along the principal axis from the composite point cloud. This ensures both the inclusion of door and window point clouds and that the extracted point clouds remain disconnected.

Fenestration cloud clustering using Euclidean segmentation: Reapply Euclidean clustering with the minimum cluster size calibrated from isolated column sections. Given that residual column segments manifest as minor circular arc fragments, this configuration successfully extracts discrete fenestration clouds. The sectional boundary parameters are subsequently computed for each fenestration cluster.

Fenestration element removal via axial filtering: Execute directional pass-through filtering along the principal axes to subtract fenestration point clouds from the composite dataset, preserving only columnar geometries.

Cylindrical parameter estimation via 2D circle fitting: Perform RANSAC-based circle fitting on the residual columnar cloud to determine centroid coordinates and radius of each structural member.

For most columns connected to a single wall, applying pass-through filtering along their principal axis is effective. However, for columns located in corner positions (i.e., corner columns), they are typically connected simultaneously to two walls in mutually perpendicular directions. To address this problem, we adopt a multi-directional filtering strategy for corner columns, i.e., applying pass-through filtering along both axes to which the corner column is connected.

The extracted column grid parameters—specifically, centroid coordinates and radius (defining structural positions)—enable the determination of individual column placement, bay widths, and structural depths. This facilitates comprehensive mapping of column distribution patterns essential for analyzing historic buildings’ planar layouts and provides spatial references for subsequent longitudinal section extraction. Within traditional Chinese timber structures, the fundamental spatial unit is termed a “structural bay”, formed by four circumjacent columns. The bay width denotes the east–west dimension. The structural depth signifies the north–south span. Aggregated bay widths constitute a building’s total facade width, while cumulative structural depths define its total structural depth, forming key indicators of traditional architectural proportions.

Component-wise parameter extraction from longitudinal sections via knowledge-constrained clustering

Leveraging the previously extracted column positional parameters—comprising centroid coordinates, radii, and the global column-grid configuration—the precise location and extent of each longitudinal section can be unambiguously determined. This subsection details the acquisition of segmentation parameters for these sections. Specifically, guided by the hierarchical joinery rules of historic timber framing, Euclidean clustering augmented with semantic constraints is applied to the longitudinal point-cloud slices of the wooden superstructure. The procedure systematically extracts component-level parameters for distinct structural zones, as illustrated in Fig. 12.

In this study, a standardized dimensional convention is established to unify component parametrization: the vertical axis is defined as height, the major axis parallel to the material grain as length, and the minor cross-sectional dimension as thickness.

-

1.

Extraction of segmentation parameters from the longitudinal section of the inner hypostyle columns along the depth direction (Section 2)

To eliminate extraneous point clouds while preserving informative data—and to constrict the clustering domain for improved accuracy—Section 2 derives component-wise parameters through a three-stage localized cutting strategy, the framework of which is illustrated in Fig. 13.

Positioning cut location 1: Extract a predetermined-width point cloud section between the eaves column (2) and outer hypostyle column (3), as demarcated in blue in Fig. 14. The component thickness relationship matrix (Table 1) enables proportional estimation of extraction range by modularly calculating component width relative to column diameters.

Fig. 14: Locating section cut position 1. Table 1 Component thickness relationships Euclidean clustering: The minimum cluster size is set to an empirically determined value of 50 to suppress noise; this threshold may be raised if excessive clutter is present. The maximum cluster size is fixed as the total number of points within the extracted slice.

Feature extraction: For each cluster returned by Euclidean clustering, all constituent point coordinates are traversed. The bounding values along the X, Y and Z axes are computed on-the-fly by dynamically updating the respective minima and maxima, yielding the spatial extent of the cluster.

Construction logic sequencing and component parameterization: Fig. 15a shows a structure with Dougong brackets. Based on construction knowledge, if there are 5 clustered parts, they include the Dougong point cloud. Sorted by height value in ascending order, from bottom to top, they are: Ground plane, penetrating tie-beam, partial dougong, corner beam, and partial eaves; if there are 4 clusters, it does not include the partial dougong point cloud. Figure 15b shows a structure without Dougong brackets. The Euclidean clustering also results in 4 clusters, which from bottom to top are: ground plane, penetrating tie-beam, baotou beam, and partial eaves.

Fig. 15: Structural connection schematic between eave columns and outer hypostyle columns. Thickness computation: Table 1 documents component thickness relationships: Penetrating tie-beam and corner beam thickness ≤ Eave column diameter; Thickness ratio penetrating tie-beam: corner beam = 3.2:6; Corner beam thickness can be derived from measured penetrating tie-beam thickness using this ratio.

Computational procedure: Expand the point cloud along the bay direction at the located component positions. Calculate actual thickness values. Length convention: Distance between eave column and outer hypostyle column centroids.

Positioning cut Location 2: Extract a fixed-width point cloud segment outside the inner hypostyle columns, as shown in the red area of Fig. 16, ensuring inclusion of cross-sectional point clouds for ceiling beam (5), double-step beam (11), and single-step beam (12).

Fig. 16: Locating section cut position 2. Euclidean clustering and feature extraction procedures are consistent with Position 1.

Construction hierarchical sequencing and component parameter acquisition: Match beam types in ascending height order:

For five clusters: Ground level (1), ceiling beam (5) (at hypostyle height), double-step beam (2), single-step beam (3), partial eaves.

For six clusters: Ground, ceiling beam, three-step beam, double-step beam, single-step beam, and partial eaves.

Utilizing the obtained component positions, expand point clouds along facade width and depth directions to generate cross-sections. Acquire thickness and length values of beam members. Reference the Doukou module system for beam categories in Table 1 when determining the point cloud expansion range.

Positioning cut Location 3: Extract a fixed-width point cloud segment above the ceiling beam in the longitudinal section between inner hypostyle columns, as shown in the yellow portion of Fig. 17.

Fig. 17: Locating section cut position 3. Euclidean clustering and feature extraction procedures align with Position 1.

Construction-knowledge constrained sorting and component parameter acquisition: Traditional construction principles dictate that ceiling beams support short posts, which in turn bear roof beams—potentially 3-purlin beams, 5-purlin beams, or 7-purlin beams. Intermediate minor columns support each beam tier.

As illustrated, the sequence bottom-to-top is: 7-purlin beam (6) (aligned with short posts height), 5-purlin beam (7), 3-purlin beam (8). Minor column heights supporting inter-beam tiers can be derived from construction knowledge.

Thickness resolution: With beam positions determined, expand point clouds along facade width and depth directions to obtain thickness and length values. Expansion ranges reference the Doukou module-to-column-diameter ratios for beam frames in Table 1.

-

2.

Longitudinal section at eave column axis (third section)

Section positioning: Due to the symmetrical layout of traditional architecture, leverage previously acquired locations of outrigger beams and ground level to extract sections between adjacent eave columns’ center points, eliminating point cloud interference above Dougong brackets.

Euclidean clustering: Since the subject is scanned point cloud data, the central regions of architrave components lack point coverage. As documented in Table 1’s Doukou module system for architraves, component thicknesses vary significantly—with cushion board thickness being substantially thinner than other architrave members. Consequently, for layered architrave assemblies, longitudinal sections will capture only cushion panel point clouds. Additionally, the sectional cutting range referenced the thickness of the cushion boards. By leveraging this difference in thickness, a certain gap is ensured between the sectioned components, thereby facilitating component parameter acquisition using the Euclidean clustering algorithm.

Feature extraction: Measure height values for each clustered segment and sort them in ascending order.

Construction sequencing and parameter acquisition:

The Dougong cluster is invariably the highest; its elevation equals the eave-column height. Given the column centroid, radius, and height, the eave-column cloud is subsequently removed from the global set by a masking strategy, preventing later confusion with sparrow braces.

Repeat Euclidean clustering.

Feature extraction: Calculate positional values for all clusters.

Construction-knowledge constrained sorting and component parameter acquisition: For the remaining architrave components not included in the section, prior knowledge of the component joint rules from traditional construction treatises, specifically the vertical stacking order (e.g., sparrow braces, minor architraves, cushion boards, major architraves, dougong brackets), is utilized. By using the heights between the separated component point clouds, positions are matched against the construction knowledge to output adjacent height pairs, as illustrated in Fig. 18.

For the Major Architraves and Flat Architraves, which are closely connected components and both absent from the sectional point cloud, Doukou-proportional constraints are used to effectively distinguish these overlapping components. This yields the positional coordinates and heights for Dougong brackets, architraves, and sparrow braces.

Using the previously extracted column parameters, the thicknesses of architraves and Dougong are obtained by transverse slicing at the corresponding elevations. The sparrow brace thickness is approximated by the column diameter. The Dougong length is approximately the total bay width or depth plus half a Dougong thickness; the Architrave length is approximately the total bay width or depth; and the sparrow brace length is approximately the individual bay width or depth.

A special mortise-and-tenon joint, known as the encircling-head tenon, is employed when major architraves and columns are combined at the end or corner positions. A transverse slice is generated at the elevation of the major architrave, and the cloud within one column diameter outward from each corner eave column is isolated (Fig. 19). Euclidean clustering is applied, the bounding values of each cluster are computed, and the geometric parameters of the encircling-head tenon are thereby obtained.

-

3.

Longitudinal section of outer hypostyle column axis plane (Section 3)

Section positioning: This section acquires parameters for door/window components in peripheral corridor-style structures. Utilizing the predetermined positions of outer hypostyle columns and the ground plane, extraction is performed along the bay direction. The thickness of ancient building walls is greater than or equal to that of the columns. In contrast, the windows in ancient architecture are primarily wooden structures, and their thickness is very slight compared to the walls—far less than the column thickness. The sectioning method adopted in this paper involves extracting a point cloud within a very small range at the column’s center; therefore, what is extracted is a “small-range” point cloud section along the column’s central axis. Because the windows are very thin and fall within this sectional cutting range, their point clouds are retained in the sectional data. Conversely, the walls are very thick; thus, the wall point clouds are filtered out during this sectioning step.

Euclidean clustering: The total point count of the sectional cloud is tallied; the door- and window-related points differ markedly in quantity from the rest. The Euclidean clustering algorithm is applied, with the minimum cluster size set to one-tenth of the total point count and the maximum cluster size set to the total itself, thereby isolating the door and window point clouds.

Feature extraction: For each clustered segment, the bounding-box coordinates are computed.

Knowledge-constrained ordering and parameter retrieval: Fig. 20 depicts the door–window–wall schematic. This paper adopts an empirical threshold of 0.5 m as the criterion. Clusters whose lowest point lies above 0.5 m are classified as window clouds, and those below 0.5 m as door clouds, from which the length and height of each door and window are obtained. Based on construction knowledge, the vertical distance from the window base to the ground defines the wall height, which can be calculated using the positions of the window and the ground. The thickness is obtained by making a transverse slice at the corresponding positional value.

Individual segmentation of structural components based on hybrid segmentation algorithms

Component segmentation algorithm combining pass-through filtering and region growing

Pass-through filtering, as a linear-complexity preprocessing operation based on spatial coordinate axes, spatially crops point clouds by setting threshold ranges along specified axes (e.g., the Z-axis). It efficiently filters out irrelevant regions, significantly reducing data volume for subsequent processing.

The Region Growing algorithm, conversely, is a clustering method based on local geometric similarity, which iteratively aggregates adjacent points with consistent normal directions and low curvature. This algorithm effectively segments continuous and homogeneous surfaces. The performance of the Region Growing algorithm is highly dependent on the setting of its key parameters, including the normal vector angle threshold and the curvature threshold31. In this study, the determination of these parameters followed a principle combining theoretical analysis and empirical testing.

Normal vector angle threshold: Considering that the surfaces of wooden components in ancient Chinese architecture (such as column surfaces and the faces of beams/architraves) are mostly regular planes or curved surfaces, the normal vector directions of adjacent points on these surfaces exhibit high consistency32. Therefore, we set a small angle threshold of 5 degrees to ensure that only points on the same smooth surface are grouped into one class.

Curvature threshold: Similarly, the curvature values of regular component surfaces are low and change gently. We set a low curvature threshold of 1 to distinguish the smooth surfaces of components from the high-curvature regions at component edges or the junctions between different components.

Parameter optimization: The initial values of the aforementioned parameters were set based on prior knowledge and were refined through iterative testing on the component point clouds. Ultimately, a parameter combination (empirical value) that achieves the best balance between over-segmentation and under-segmentation was selected to ensure the robustness and accuracy of the segmentation.

Combining pass-through filtering and region growing leverages their complementary strengths—a pragmatic and efficient strategy. Pass-through filtering first rapidly pre-filters data, using component parameters obtained in the section “Parameter derivation via Euclidean clustering algorithm for individual component segmentation” to focus on target regions while eliminating large-scale noise interference. This addresses the region growing’s inefficiency and noise sensitivity in large-scale scenes. Subsequently, region growing performs refined segmentation on the simplified point cloud, identifying continuous surfaces through dual constraints of normal vectors and curvature. This approach accommodates minor surface deformations in historic timber columns without over-relying on idealized geometric models (e.g., traditional RANSAC). The integrated methodology synergizes both algorithms’ advantages, effectively mitigating false merging and over-segmentation while resolving computational burdens and segmentation accuracy challenges in complex heritage building point clouds.

Segmentation occlusion strategy

Within the refined segmentation process of heritage building point clouds, particularly after achieving the individual extraction of principal load-bearing components (such as columns), a critical preprocessing step involves applying an occlusion strategy. The core objective of this strategy is to effectively remove successfully segmented component point clouds, significantly reducing the complexity of subsequent segmentation algorithms and improving segmentation accuracy.

The implementation of this occlusion strategy follows the steps below, using column point clouds as an example:

-

1.

Pass-through filtering localization:

Utilize the 3D bounding boxes generated during component individualization. The spatial extent of these bounding boxes should fully encompass all regions previously occupied by columns, along with adjacent areas. Removing all point clouds within these 3D bounding boxes generates a primary candidate residual point cloud dataset.

-

2.

Integration of unclassified points:

Combine all non-column points and unclassified point clouds produced during the individualization process within the 3D bounding boxes. This ensures that after final column removal, any points potentially belonging to other components—non-column points, including those not explicitly classified previously—are seamlessly and securely preserved, preventing data exclusion.

-

3.

Merging residual data:

Merge the integrated point cloud from Step 2 with the primary candidate residual point cloud dataset generated in Step 1. This yields a final residual point cloud where all segmented column point clouds are eliminated while maximizing preservation of information from all other components.

Heritage building component individualization

Table 2 lists the segmentation parameters acquired from corresponding cross-sectional profiles for each structural component. Utilizing these parameters, axis-aligned bounding boxes (AABB) are constructed via the pass-through filtering algorithm to extract point clouds containing target components. Adventitious point clouds within these bounding volumes are subsequently eliminated through the region growing algorithm, ultimately yielding individualized component point clouds.

This study performs component individualization following traditional large timber assembly sequences, sequentially processing: columns, ceiling beams, ceiling tie beams, penetrating tie beams, corner beams, sparrow braces, architraves, Dougong brackets, and finally door/window/wall components for interior finishing.

-

1.

Column individualization

Serving as primary load-bearing elements and topological anchor points for subsequent segmentation, individualized column extraction provides spatial references to enhance segmentation precision (see Fig. 21).

Utilizing pre-acquired cylinder parameters (centroid coordinates, radii), a 0.03 m radial extension around each cylindrical axis forms a cuboid constraint space. Pass-through filtering constructs AABB to isolate regional point clouds, narrowing the processing scope. The region growing algorithm is then applied to achieve preliminary segmentation.

Post-processing strategy for wall-embedded columns: Merging exclusively clusters with consistent geometric parameters (cylinder-fitting radii, axial orientations) to eliminate non-columnar outliers. Validating spatial continuity via KD-Tree spatial indexing to preserve structural integrity. Filtering out clusters lacking geometric coherence or spatial contiguity.

An occlusion strategy subsequently removes segmented column point clouds: Pass-through filtering identifies residual regions; Unclassified points from initial segmentation are reintegrated into the global dataset; Column-stripped residual point clouds are generated for downstream operations. This establishes precise spatial coordinates for inter-column connections while precluding potential confounding interference during subsequent component segmentation.

-

2.

Individualization of ceiling beams and ceiling tie beams

In the section “Parameter derivation via Euclidean clustering algorithm for individual component segmentation” second cross-section, a longitudinal section individualized parameter extraction method based on construction knowledge-constrained clustering was utilized to obtain the positional coordinates, length, thickness, and height of ceiling beams. Using the aforementioned parametric data, the pass-through filtering algorithm was applied to define constraints with upper/lower bounds along all three spatial dimensions, isolating point cloud regions conforming to the specified range. Subsequently, the region growing algorithm eliminated interfering noise points, yielding individualized point clouds of the ceiling beams. The workflow is illustrated in Fig. 22.

-

3.

Individualization of penetrating tie beams and corner beams

Utilizing parameters (position, length, thickness, height) acquired from Section 2 in “Parameter derivation via Euclidean clustering algorithm for individual component segmentation” for penetrating tie beams and corner beams, apply combined pass-through filtering and region-growing segmentation to extract individualized point clouds for these components.

-

4.

Individualization of architraves, dougong brackets, and sparrow braces

Employing parameters (position, length, thickness, height) obtained from Section 3 in “Parameter derivation via Euclidean clustering algorithm for individual component segmentation” for Dougong, architraves, and sparrow braces, implement integrated pass-through filtering and region-growing segmentation to derive individualized point clouds for these elements.

-

5.

Individualization of step beams and roof beams

Using dimensional parameters (length, thickness, height) acquired from Section 2 in “Parameter derivation via Euclidean clustering algorithm for individual component segmentation” for step beams and roof beams, execute combined pass-through filtering and region-growing segmentation to generate individualized point clouds for these structural members.

-

6.

Individualization of doors, windows, and walls

Applying parameters (length, thickness, height) derived from Section 4 in “Parameter derivation via Euclidean clustering algorithm for individual component segmentation” for door/window/wall assemblies, perform integrated pass-through filtering and region-growing segmentation to obtain individualized point clouds for these finishing components.

Results

In this section, we will employ point cloud data from the Hall of Central Harmony in the Forbidden City, utilizing the C++ programming language and Point Cloud Library (PCL) on the Microsoft Visual Studio 2017 platform to implement the component individualization segmentation task.

Experimental data

This experiment obtained point cloud data of the Hall of Central Harmony in China’s Forbidden City through 3D laser scanning. The Hall of Central Harmony was initially constructed in the 18th year of the Yongle era of the Ming Dynasty (1420 AD), and has a history spanning over 600 years.

Acquisition of sections

The Hall of Central Harmony is a quadrangular pyramidal roof palace-style structure, featuring a surrounding colonnade with six rows of columns, as shown in Fig. 23. Its plan is square, with encircling corridors. The framework primarily uses nanmu wood, with a row of front and rear eaves columns along the depth direction. There are four rows of principal columns (categorized by position as inner and outer principal columns). These four rows collectively support the ceiling beam and the timber framework above. The eaves columns and principal columns are interconnected by corner beams and penetrating tie beams. Above the ceiling beam, the framework employs short posts for height extension.

Profile acquisition was performed using a section-cutting location determination method based on ancient architectural tectonic knowledge, obtaining the following section diagrams: a transverse section through the central column grid, a longitudinal section along the inner hypostyle columns in the depth direction, a longitudinal section of the eave column axial plane, and a longitudinal section of the outer hypostyle column axial plane. The section diagrams are shown in Fig. 24.

Parameter extraction

-

1.

Transverse section through the central column grid

For the transverse section through the central column grid, column parameters were acquired using a dual-stage clustered column point cloud processing algorithm. First, through first-stage Euclidean clustering, the complex column point cloud was divided into independent column point clouds and composite column point clouds, as shown in Fig. 25. Then, for the independent column point clouds, RANSAC-based 2D circle fitting was employed to obtain the centroid coordinates and radius of each individual column point cloud, with the average radius calculated from the independent column point clouds.

Subsequently, for the composite column point clouds, second-stage composite column parameter acquisition was performed by filtering out door/window point clouds to retain only the column point clouds, as illustrated in Fig. 26.

2D circle fitting was applied to the remaining column point clouds to derive centroid coordinates and radius values, with extracted column radius parameters provided in Table 3:

Table 3 Column parameters -

2.

Longitudinal section along the inner hypostyle columns in the depth direction

A 10 cm-wide point cloud section was captured between the eave columns and outer hypostyle columns, as shown in the blue fragment of Fig. 27. Positional and parametric values of penetrating tie beams and corner beams were obtained.

A 10 cm-wide point cloud section was extracted 10 cm outward from the interior hypostyle columns, as indicated by the red fragment in Fig. 27. Euclidean clustering was applied for parameter acquisition, yielding six clustering groups - revealing that the Hall of Central Harmony contains minor columns inserted with single-step, double-step, and triple-step beam ends. The longitudinal section component parameter extraction method with structural knowledge-constrained clustering was employed to obtain positional and parametric values of ceiling beams, hypostyle columns, triple-step beams, double-step beams, and single-step beams.

A 10cm-wide point cloud section above the ceiling beams was captured, as highlighted in the yellow fragment of Fig. 27. Euclidean clustering was performed on this section, with boundary values extracted to determine beam frame heights and positions.

Component thickness values were acquired by expanding laterally. Component parameters acquired from the longitudinal section (depth direction) along the inner hypostyle columns are documented in the pink section of Table 4.

Table 4 Component parameters -

3.

Longitudinal section of the eave column axial plane

Using the previously acquired column coordinate parameters and the positions of corner beams and ground level, a longitudinal section point cloud was generated at the centroidal position between two eave pillars (as shown by the red marker in Fig. 28). The longitudinal section component parameter extraction method with structural knowledge-constrained clustering was applied to obtain dougong brackets positions and eave columns heights.

Fig. 28 Leveraging the pre-acquired column centroid coordinates and radius parameters, along with the newly measured eave pillar heights in this section, a segmentation and masking method was implemented on the overall point cloud to remove column points. A longitudinal section was then generated at the same location (indicated by the green marker in Fig. 29a), followed by Euclidean clustering.

Fig. 29: Schematic diagram of longitudinal section along eave column axis plane in Hall of Central Harmony. Positional data extraction was performed for each clustered segment, with construction-constrained sequencing applied to identify component positions(Fig. 29b): Green represents sparrow braces; between green and blue denotes minor architraves; blue indicates cushion boards; between green and red signifies major architraves integrated with flat architraves; and red marks Dougong brackets. At the architrave height plane, a transverse section point cloud was captured and further constrained using eave column diameters. Through Euclidean clustering, encircling—head tenon point clouds were identified, with boundary values such as height calculated. Component parametric values extracted from the longitudinal section of the eave column axial plane are presented in the orange section of Table 4.

-

4.

Longitudinal section of the outer hypostyle column axial plane

For peripheral corridor-style building door/window components, leveraging the pre-acquired positions of outer eave hypostyle columns and ground level, a longitudinal section of the outer hypostyle column axial plane was captured (Fig. 30a). Euclidean clustering was then directly applied to cluster door/window point clouds (Fig. 30b).

Subsequently, door/window identification criteria were implemented to distinguish doors from windows, compute boundary values, and derive positional parameters. Component parametric values extracted from the outer hypostyle column axial plane longitudinal section are presented in the blue rows of Table 4.

Component individualization

Profile positions were initially determined based on timber structural connection patterns and the inherent symmetry of historic buildings. For each profile, enhanced Euclidean clustering was employed to extract individual component segmentation parameters. Table 4 presents the parametric values of columns, beams, and architraves obtained following bottom-to-top and interior-to-exterior sequence principles. To standardize component parameters, vertical dimensions are defined as height, longer edges as length, and shorter edges as thickness.

Certain parameter values were approximated using column diameters or bay dimensions (e.g., in traditional Chinese architecture, four columns define one bay: east–west dimension = bay width, north–south dimension = bay depth). Component segmentation was executed using a method combining pass-through filtering and region-growing algorithms. To enhance segmentation accuracy, a segmentation masking strategy was implemented.

Column individualization: First, individualization segmentation of column components was performed. Building upon the acquired centroid coordinates and diameters of columns, extended bounding boxes were constructed for region-growing segmentation. For instances where columns embedded within wall point clouds exhibited fragmentation, clusters with homogeneous geometric parameters were merged. As illustrated in Fig. 31, Column-individualized point clouds were obtained.

Subsequently, the segmentation masking strategy was applied to subtract column point clouds from the global point cloud for subsequent component individualization, as demonstrated in Fig. 32.

Individualization of ceiling beams and ceiling tie beams: Utilizing parameters (position, length, height, thickness) for ceiling beams and ceiling tie beams obtained in the section “Parameter extraction” (detailed values in Table 4), apply combined pass-through filtering and region-growing segmentation to extract individualized components. Results are shown in Fig. 33b.

Individualization of penetrating tie beams and corner beams: Employing parameters (position, length, height, thickness) for penetrating tie beams and corner beams acquired the section “Parameter extraction” (specified in Table 4), implement integrated pass-through filtering and region-growing segmentation to derive individualized components. Outcomes are illustrated in Fig. 33c and d.

Individualization of architraves, dougong brackets, sparrow braces, and encircling—head tenon: Using parameters (position, length, height, thickness) for architraves, Dougong, sparrow braces, and encircling-head tenon determined the section “Parameter extraction” (tabulated in Table 4), executed combined pass-through filtering and region-growing segmentation to generate individualized components. Visualizations are provided in Fig. 35e–h.

Individualization of roof beams, triple-step beams, double-step beams, and single-step beams: Applying parameters (position, length, height, thickness) for roof beams, triple-step beams, double-step beams, and single-step beams from the section “Parameter extraction” (refer to Table 4), perform integrated pass-through filtering and region-growing segmentation to obtain individualized components. Results are displayed in Fig. 33i.

Individualization of doors, windows, and walls: Leveraging parameters (position, length, height, thickness) for door/window/wall assemblies obtained in the section “Parameter extraction” (see Table 4): Construct bounding boxes using construction-knowledge-constrained pass-through filtering. Implement region-growing segmentation within bounding boxes. Achieve individualized components. Segmentation outcomes are shown in Fig. 33j– l.

Comparative experiments

To rigorously validate the accuracy of ancient architectural component individualization via the proposed segmentation method, this study adopts manually segmented component point clouds as ground truth for comparative experiments against classical traditional segmentation approaches. Two experimental groups were established: one for column component individualization and another for architrave components conforming to regular geometric constraints.

For column components, the column point cloud’s centroid coordinates and radii were previously obtained, and a bounding box was constructed. Then, the RANSAC algorithm, the least-squares method, the cylindrical mathematical model, and the region-growing algorithm used in this paper were applied separately for point cloud segmentation within the bounding box. As shown in Fig. 34.

Validation was conducted through a multi-metric protocol: First, manually segmented data served as ground truth for iterative closest point (ICP) registration against outputs from the three methods, with registration outcomes illustrated in Fig. 35. Second, bidirectional error verification was implemented—measuring both test-to-reference and reference-to-test point cloud distances—to eliminate coverage gaps, with accuracy metrics documented in Table 5.

Third, the comprehensive evaluation included combined root mean square error (synthesizing bidirectional deviations), F1-score (balancing precision and recall), and Intersection-over-Union (IoU) spatial overlap analysis, as quantified in Table 5.

The results demonstrate that the proposed method consistently outperforms the RANSAC fitting, least squares, and cylindrical mathematical model segmentation methods in terms of accuracy when compared to these other three point cloud segmentation approaches. It can be observed from the table that, compared to the RANSAC fitting, least squares, and cylindrical mathematical model segmentation methods, the proposed method consistently achieves a lower RMSE in point cloud matching, a higher F1-score than the other three methods, and an Intersection-over-Union (IoU) that is 0.026, 0.038, and 0.072 higher than the other three methods, respectively.

For architrave components within regular geometric structures, comparative segmentation experiments were conducted using pre-obtained parameter values through three distinct approaches: (a) pass-through filtering, (b) bounding-box-assisted Euclidean clustering, and (c) the proposed bounding-box-aided region-growing algorithm (Fig. 36).

To ensure rigorous validation, manually segmented point clouds served as ground truth for iterative closest point (ICP) registration against outputs from these methods. Figure 37 presents registration comparisons, while Table 6 quantifies accuracy through forward and reverse registration metrics.

Comparative analysis reveals distinct segmentation deficiencies: The pass-through filtering algorithm produced extraneous point clouds relative to the ground truth data, including erroneous points like mortise-tenon joint noise points. Concurrently, the bounding-box-assisted Euclidean clustering method suffered from reduced point cloud density and ambiguous geometric proximities, leading to the erroneous grouping of interfering points with structural architrave points—resulting in indistinguishable clusters and suboptimal segmentation. Our proposed methodology effectively resolved this issue through precise spatial positioning and holistic structural analysis. As quantitatively demonstrated in Table 6 (architrave component evaluation metrics comparison), the approach delivers superior performance.

Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves a root mean square error (RMSE) of 0.00928246, an F1-score of 0.993623, and an Intersection-over-Union (IoU) of 0.98561, significantly exceeding both alternative methods. Our approach outperformed the pass-through filtering and bounding-box-assisted Euclidean clustering methods by IoU margins of 0.05 and 0.02, respectively. These outcomes substantiate the method’s superior accuracy in segmenting geometrically analogous structures and boundaries, particularly for visually ambiguous categories.

Discussion

This study addresses the technical challenges of low efficiency and weak semantic association in point cloud segmentation for digital preservation of ancient timber structures, proposing an innovative method that integrates traditional construction knowledge with modern point cloud processing. Through empirical research on the Hall of Central Harmony in Beijing’s Forbidden City as a representative case study, the following conclusions were drawn:

-

1.

A cross-section determination method for heritage segmentation parameters based on historical construction techniques and structural joinery constraints was established.

-

2.

A parameter extraction framework for heritage component segmentation was developed through the fusion of spatial geometric features and historical architectural knowledge.

-

3.

A component individualization algorithm combining pass-through filtering with region-growing methods was constructed for scanning point clouds of wooden members.

Leveraging traditional timber joining principles for cross-section determination and acquisition, our whole-to-local processing strategy obtains parameters through Euclidean clustering and semantically constrained analysis of sliced point cloud data from structural subsections. Component individualization employs a dual algorithm of pass-through filtering and region growing, implementing sequential masking of extracted components to prevent redundant segmentation. After extracting target component point clouds from the global dataset during individualization, the corresponding subsets are systematically masked in the original point cloud. This critical workflow prevents segmentation errors caused by data overlap while enhancing individualization accuracy.

By transforming historical construction knowledge into computable semantic rules, our algorithm simultaneously determines component types during geometric feature analysis, establishing bidirectional mapping between 3D data and architectural semantics. This approach not only provides a reliable technical pathway for heritage BIM reconstruction, but also enables deformation parameters calculation from individualized components—delivering crucial references for preventive conservation and restoration. The knowledge-fused data processing methodology demonstrates significant reference value for digital preservation in architectural and cultural heritage.

Although this method demonstrates high-precision advantages in processing timber-frame architecture with clear construction rules, its limitations, generalizability, and future development potential also deserve in-depth discussion. The core limitation of the current method lies in its dependence on specific domain knowledge; its successful application is premised on the existence of a systemized set of construction rules that can be computationally translated. However, this core idea of “construction knowledge-driven segmentation” is highly portable. For example, for timber-frame architecture from different cultural backgrounds, such as the Japanese Dougong system and the Chinese Dougong, while differing in modulus and assembly logic, they likewise follow a set of rigorous rules. By encoding and parameterizing these specific rules, this method can be adapted to the corresponding architectural systems. Therefore, this method is applicable to any architectural type that possesses a codified or uncodified, yet systemized, construction “grammar”.

To overcome current limitations and expand the depth and breadth of this method’s application, future research will proceed in the following directions:

-

1.

Multi-modal data fusion and refined segmentation: A key future direction is the deep fusion of this study’s knowledge-driven method with multi-modal data (such as high-resolution imagery, hyperspectral, or thermal infrared data). This strategy will not only enhance segmentation robustness by fusing information like texture and material, but more importantly, it will associate geometric information with physical material information (such as paint finishes, decorative paintings, or deterioration levels). This will endow HBIM with richer semantic content and provide comprehensive data support for deterioration assessment and conservation/restoration.

-

2.

Deepening economic valuation applications: In the practical management of heritage conservation, precise cost control is crucial. By achieving component-level individualization, this method can deepen macroscopic asset valuation down to microscopic cost accounting. Future work will focus on achieving high-precision estimation of conservation project budgets, providing powerful decision support for the cost-benefit analysis of heritage management.

-

3.

Enhancing scalability and automation: This study, using the Hall of Central Harmony as a case study, successfully verified the segmentation effectiveness of the method combining construction knowledge and point cloud algorithms on major components. However, the method’s deeper potential lies in its ability to segment components that remain unsegmented. For instance, when facing morphologically complex components, such as the Guazhu (melon-shaped short posts) in the hip roof of the Hall of Supreme Harmony, purely geometric point cloud processing methods might fail. But based on the construction logic this method relies on, such as the Doukou modular system of Qing-style architecture, the key parameters of these components (like the Guazhu height) can be precisely calculated through their proportional relationship with the Doukou. This eloquently demonstrates that geometric segmentation and construction knowledge reasoning are two complementary paths—two sides of the same coin—for component individualization. Therefore, future research will focus on constructing a formalized knowledge base of ancient architectural construction (such as an architectural ontology or knowledge graph). By establishing such a knowledge system, the algorithm can automatically query and invoke corresponding segmentation rules and parameters based on the building type, thereby significantly enhancing the automation level and scalability of the processing workflow and laying a foundation for intelligent, regional-level heritage monitoring and management.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Yang, X. et al. Review of built heritage modelling: Integration of HBIM and other information techniques. J. Cult. Herit. 46, 350–360 (2020).

Yang, Z. et al. Seismic vulnerability assessment of historical timber temples: a case study of the Hanging Temple in China. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 4 (2025).

Zhang, J. et al. A review of deep learning-based semantic segmentation for point cloud. IEEE Access 7, 179118–179133 (2019).

He, T., Shen, C. & van den Hengel, A. Dynamic convolution for 3D point cloud instance segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 45, 5697–5711 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. GC-MLP: graph convolution MLP for point cloud analysis. Sensors 22, 9488 (2022).

Du, Z., Ye, H. & Cao, F. A novel local–global graph convolutional method for point cloud semantic segmentation. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 35, 4798–4812 (2024).

Morbidoni, C. et al. Learning from synthetic point cloud data for historical buildings semantic segmentation. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 13, 1–16 (2020).

Wang, F. et al. Real-time semantic segmentation of point clouds based on an attention mechanism and a sparse tensor. Appl. Sci. 13, 3256 (2023).

Bayu, A. et al. Semantic segmentation of lidar point cloud in rural area. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Communication, Networks and Satellite (Comnetsat) 73–78 (Makassar, Indonesia 2019).

Wicaksono, S. B., Wibisono, A., Jatmiko, W., Gamal, A. & Wisesa, H. A. Semantic segmentation on LiDAR point cloud in urban area using deep learning. In 2019 International Workshop on Big Data and Information Security (IWBIS) 63–66 (Bali, Indonesia 2019).

Gamal, A. et al. Outdoor LiDAR point cloud building segmentation: progress and challenge. In 2021 International Conference on Advanced Computer Science and Information Systems (ICACSIS) Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc https://doi.org/10.1109/ICACSIS53237.2021.9631345 (IEEE, 2021).

Su, Y. F. et al. DLA-Net: learning dual local attention features for semantic segmentation of large-scale building facade point clouds. Pattern Recognit. 123, 108372 (2022).

Gamal, A. et al. Automatic LIDAR building segmentation based on DGCNN and Euclidean clustering. J. Big Data 7, 102 (2020).

Zhao, J. et al. Semantic segmentation of point clouds of ancient buildings based on weak supervision. Herit. Sci. 12, 232 (2024).

Qiu, H. et al. Research on intelligent monitoring technology for roof damage of traditional Chinese residential buildings based on improved YOLOv8: taking ancient villages in southern Fujian as an example. Herit. Sci. 12, 231 (2024).

Fischler, M. A. & Bolles, R. C. Random sample consensus: a paradigm for model fitting with applications to image analysis and automated cartography. Commun. ACM 24, 381–395 (1981).

Kivilcim, C. Ö & Duran, Z. Parametric architectural elements from point clouds for HBIM applications. Int. J. Environ. Geoinform. 8, 144–149 (2021).