Abstract

Cardiovascular events occur 20 years earlier in Sub-Saharan Africa compared to Europe. The risk factors for atherosclerosis differ between population groups and according to age. We compared the main correlates of carotid intima-media thickness (IMT, an index of atherosclerosis) in young and older adults of African ancestry. Hemodynamic (central and peripheral arterial pressures) and metabolic factors (lipids, glucose, glycated haemoglobin), smoking status and carotid IMT were determined in 573 adult Africans. In young (age<35years, n = 181) and middle-aged (35–59years, n = 231) adults, carotid IMT was associated with hemodynamic and metabolic cardiovascular risk factors on bivariate analyses. In older (age≥60years, n = 161) adults only hemodynamic factors were associated with carotid IMT. After adjustments for confounders, lipids were not associated with carotid IMT at any adult age. Carotid IMT was independently associated with backward wave pressure (Pb, p = 0.001) and age (p = 0.006) in young adults; with hemodynamics (central systolic blood pressure, p = 0.003; Pb, p = 0.02), age (p = 0.0002), body mass index (BMI, p = 0.005) and heart rate (p = 0.007) in middle-aged adults; and with Pb (p < 0.0001), male sex (p = 0.03), and HR (p = 0.04) in older adults. Increased carotid IMT was related to Pb in young (odds ratio [OR] = 1.233, p = 0.0003) and older (OR = 1.086, p = 0.0059) adults, and BMI (OR = 1.089, p = 0.0005) in middle-aged adults. Improvements in predictive performance for detecting increased carotid IMT were shown with Pb in young (p = 0.0032) and older (p = 0.0031) adults, and with BMI (p = 0.0004) in middle-aged adults. In conclusion, in African adults in Sub-Saharan Africa, carotid IMT is associated with hemodynamic factors, but not lipids. Moreover, in young adults, carotid IMT is primarily associated with hemodynamic factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the primary cause of death worldwide [1]. However, there are differences in the burden of CVD between countries, with concerns of an emerging pandemic of CVD in Sub-Saharan Africa [2], in contrast to Europe and America, where CVD appears to be on the decline [3]. Moreover, in people of African descent, the onset of cardiovascular outcomes is premature, occurring approximately 15–20 years earlier than in people of European descent [4]. Hence, it is essential to screen for and prevent CVD in Sub-Saharan Africa, especially among young adults.

Carotid artery intima-media thickness (IMT), a proxy for subclinical atherosclerosis, is an important non-invasive screening tool for CVD [5]. However, carotid IMT is lower in African populations living in Africa compared to other populations [6]. Variations in risk factors for CVD in Sub-Saharan African compared to European and American countries, may account for population differences in IMT. A recent systematic review points toward hypertension rather than dyslipidaemia, being the primary risk factor for CVD in Sub-Saharan African countries [7]. Indeed, central arterial stiffness, central arterial blood pressure (BP) [8] and central arterial pressure augmentation [9] are elevated in African compared with European individuals, particularly among young adults [8]. Moreover, in African populations living in Africa compared to in European populations, HDL cholesterol has a greater protective effect and LDL cholesterol a weaker negative impact on carotid IMT [6].

Despite the high prevalence of CVD, there are limited data assessing the determinants of carotid IMT in Sub-Saharan African populations, especially in young adults. Although a large study in four Sub-Saharan African countries identified factors associated with carotid IMT, these data were restricted to adults aged 40–60 years [10]. In this regard, the determinants of carotid IMT have been shown to differ according to age in Chinese [11], and European [12] individuals. However, to our knowledge there are no data assessing the determinants of carotid IMT in young adults of African ancestry. We therefore aimed to identify the main hemodynamic and metabolic cardiovascular risk factors associated with carotid IMT in young (age<35 years) compared to middle-aged (age 35–59 years) and older (age≥60 years) adults of African ancestry.

Methods

Study group

The present study was approved by the Committee for Research on Human Subjects of the University of the Witwatersrand (approval number: M02-04-72 and renewed as M07-04-69, M12-04-108, M17-04-01, and M22-03-93), and conducted according to the principles outlined in the Helsinki declaration. Participants gave informed, written consent. The design of the study has previously been described [13, 14]. Briefly, families of black African descent (Nguni and Sotho chiefdoms) with siblings older than 16 years of age were randomly recruited from the South West Township (SOWETO) of Johannesburg, South Africa. In the present study, 573 participants with both carotid IMT and high quality velocity measurements in the aortic outflow tract were assessed. To identify the cardiovascular risk factors associated with carotid IMT in young compared to older adults, the study group was divided into three age categories: young: age<35 years (n = 181); middle-aged: age 35–59 years (n = 231); elderly: age≥60 years (n = 161).

Clinical, demographic, anthropometric and laboratory information

Demographic, lifestyle and clinical data were obtained by means of a questionnaire [13]. Standard approaches were used to measure height and weight. Participants were considered to be overweight if their body mass index (BMI) was ≥25 kg/m2 and obese if their BMI was ≥30 kg/m2. Blood glucose, lipid profiles, and percentage glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) were assessed after at least a 12 h fast. Diabetes mellitus (DM) was defined as an HbA1c value greater than 6.5%, or the use of insulin or oral glucose lowering agents. We also determined fasting plasma insulin concentrations from an insulin immulite, solid phase, two-site chemiluminescent immunometric assay (Diagnostic Products Corporation, Los Angeles, CA, USA) and insulin resistance was estimated by the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) using the formula (insulin [µU/ml] × glucose [mmol/l])/22.5. High quality office brachial BP measurements were obtained according to guidelines, after 5 min of rest in the seated position, by a trained nurse-technician using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer [13]. Office BP was the mean of 5 brachial BP measurements obtained at least 30 s apart. Hypertension was defined as a mean office systolic BP ≥ 140 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mm Hg or the use of antihypertensive medication. Uncontrolled BP was defined as mean office systolic BP ≥ 140 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mm Hg.

Carotid IMT

Carotid IMT was determined using high resolution B-mode ultrasound (SonoCalc IMT, Sonosite Inc, Bothell, Washington) as previously described [15] employing a linear array 7.5 MHz probe. Images of at least 1 cm length of the far wall of the distal portion of both the right and left common carotid arteries from an optimal angle of incidence (defined as the longitudinal angle of approach where both branches of the internal and external carotid artery are visualised simultaneously) at least 1 cm proximal to the flow divider were obtained. Carotid IMT measurements were determined using semi-automated border-detection and quality control software [15]. At least 3 measurements were obtained from both the right and left sides and the mean of data from both sides was used for analyses. Increased IMT was defined as >75th percentile for decade of age and sex as previously defined in normotensive, nondiabetic participants [15]. Carotid plaque was determined from both longitudinal and cross-sectional images in and around the carotid bifurcation [15]. Carotid plaque was defined according to the Mannheim consensus as a focal structure that encroaches into the arterial lumen of at least 0.5 mm or 50% of the surrounding IMT value or demonstrates a thickness >1.5 mm as measured from the media-adventitia interface to the intima-lumen interface.

Hemodynamic assessments

Hemodynamic parameters were determined from non-invasive central arterial pressure measurements derived from peripheral pulse wave analysis (radial artery applanation tonometry and SphygmoCor software), and the assessment of aortic velocity and diameter in the outflow tract (Acuson SC2000 Diagnostic ultrasound system, Siemens Medical Solutions, USA, Inc.) as previously described [14, 16].

After participants had rested for 15 min in the supine position, arterial waveforms at the radial (dominant arm) pulse were recorded, during an 8 s period, by applanation tonometry using a high-fidelity SPC-301 micromanometer (Millar Instrument, Inc., Houston, Texas). The micromanometer was interfaced with a computer employing SphygmoCor, version 9.0 software (AtCor by Cardiex, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia). The pulse wave was calibrated by manual measurement (auscultation) of brachial systolic and diastolic BP taken immediately before the recordings. A validated generalised transfer function incorporated in SphygmoCor software was used to convert the peripheral pressure waveform into a central aortic waveform. Recordings where the systolic or diastolic variability of consecutive waveforms exceeded 5% or the amplitude of the pulse wave signal was less than 80 mV, were discarded.

Immediately after obtaining the central arterial pressure waveforms, aortic velocity and diameter measurements were acquired by an experienced observer (AJW) using an Acuson SC2000 Diagnostic ultrasound system (Siemens Medical Solutions, USA, Inc.). High quality velocity assessments, obtained in the 5-chamber view, were identified as those with a smooth velocity waveform, a dense leading (outer) edge and a clear maximum velocity. Aortic diameter measurements were obtained just proximal to the aortic leaflets in the long axis parasternal view, and the largest diameter recorded in early systole was used to construct the aortic flow waveform. Taking care to avoid any overshoot of the image, the leading (outer) edge or the most dense, or brightest portion of the spectral image of the velocity waveform was outlined using graphics software. The velocity waveform and aortic diameter measurements were employed to construct an aortic flow waveform where flow = velocity x aortic root cross-sectional area calculated from diameter assessments. Stroke volume (SV) was calculated from the product of the velocity-time integral and aortic root cross-sectional area. Stroke volume was also indexed to body surface area. MAP was determined from the arterial pressure wave using SphygmoCor software. Total arterial compliance (TAC) was calculated as SV/PPc. As it has been recommended that either time or frequency domains are appropriate for the assessment of aortic characteristic impedance (Zc) [17], Zc was determined in the time domain using approaches previously described [14, 16, 18] and validated against invasive pressure measurements [19]. The volume flow waveform was paired with the central arterial pressure waveform by aligning the foot (t0) of the respective signal averaged waveforms. The point at which flow achieves 95% of its peak (tQ95) was identified. The change in pressure between t0 and tQ95 was determined. Aortic characteristic impedance was calculated as the ratio of change in pressure to change in flow in the window t0 to t95. Wave separation analysis was performed using Zc values and flow and pressure waveforms, and backward wave pressures (Pb) determined from (PPc - peak PQxZc)/2. The contribution to forward wave pressures (Pf) of pressures determined by an interaction between flow (Q) and Zc was identified from the pressures generated by the product of peak aortic Q and Zc (peak PQxZc) [20]. The use of peak PQxZc rather than Pf, excludes the possibility of errors inherent in the use of Pf which includes pressures generated by wave re-reflection [20].

Data analysis

Database management and statistical analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.4 (The SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Continuous variables are expressed as mean ( ± SD) for parametric data or median (interquartile range) for non-parametric data. Dichotomous variables are expressed as percentages. As glycated haemoglobin, blood glucose, HOMA-IR, total, LDL, HDL and total/HDL cholesterol were not normally distributed they were logarithmically transformed (natural logarithm, ln) prior to performing linear regression analyses. To identify independent relationships between carotid IMT and hemodynamic and metabolic factors, multivariate adjusted linear regression analyses were performed. Adjustments were for age, sex, BMI, DM (except for glucose due to collinearity), regular alcohol intake, regular tobacco intake, heart rate, treatment for hypertension and MAP (except for hemodynamic factors due to collinearity). Logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the odds of increased carotid IMT in association with one unit increments in hemodynamic or metabolic factors independent of confounders. The performance of hemodynamic or metabolic factors in identifying individuals with increased carotid IMT was assessed using receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, and the determination of integrated discrimination improvement, and net reclassification improvement [21, 22].

Results

Participant characteristics

Table S1 (on-line supplement) shows the general characteristics of all participants in the current study. A large proportion were either overweight or obese, almost a half had hypertension, which was largely uncontrolled, over a third had increased carotid IMT, but the prevalence of plaque was low (< 5%). Almost a half of the women were postmenopausal, however, none of the women were receiving hormone replacement therapy.

Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the participants according to age group. As per definition, the 3 groups differed by age. The young adults had less obesity, hypertension and DM, lower blood glucose, glycated hemoglobin, total and LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, BP, SV, Pb, Q, peak PQxZc, carotid IMT and plaque than the middle-aged and older groups. In addition, the middle-age group had less hypertension and DM, lower blood glucose, glycated hemoglobin, total and LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, BP, SV, Pb, Q, peak PQxZc, carotid IMT, and plaque than the older age group.

Unadjusted associations between cardiovascular risk factors and carotid IMT in all participants

On-line supplemental Table S2 shows the bivariate associations between carotid IMT and cardiovascular risk factors, including hemodynamic and metabolic factors, in all participants. Sex, regular smoking, and regular drinking were the only factors not associated with carotid IMT. Although, on bivariate analysis in women only, postmenopausal status was associated with carotid IMT (Pearson’s r = 0.592, p < 0.0001), after adjustment for age this relationship was no longer significant (Partial r = 0.066, p = 0.19). Furthermore, after inclusion of multiple cardiovascular risk factors (age, BMI, smoking, alcohol, diabetes mellitus, treatment for hypertension, mean arterial pressure, and heart rate), postmenopausal status was not associated with carotid IMT (p = 0.17).

Unadjusted associations between cardiovascular risk factors and carotid IMT in different age groups

Table 2 shows the bivariate associations between carotid IMT and cardiovascular risk factors, including hemodynamic and metabolic factors, in the three age groups. Regular smoking, regular drinking and treatment for hypertension were not associated with carotid IMT at any age. Of the metabolic risk factors, HOMA-IR, total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol were not related to carotid IMT in any of the age groups. Of the hemodynamic factors, blood flow (SV and Q) was not related carotid IMT in any age group.

In the young adults, prior to any adjustments, carotid IMT was associated with age and the presence of hypertension. Central systolic BP and Pb were the only hemodynamic factors, and total/HDL cholesterol was the only metabolic factor associated with carotid IMT in young adults (Table 2).

In middle-aged adults, prior to any adjustments, carotid IMT was associated with age, BMI, the presence of hypertension, and the presence of DM. The hemodynamic factors associated with carotid IMT were brachial systolic, diastolic and mean BP, brachial pulse pressure, central systolic BP, central pulse pressure, heart rate, TAC, Pb and peak PQxZc. The metabolic factors associated with carotid IMT in the middle-aged adults were blood glucose, glycated haemoglobin, total/HDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and triglycerides (Table 2).

In older aged adults, prior to any adjustments, carotid IMT was associated with age and male sex. Brachial systolic and mean BP, brachial pulse pressure, central systolic BP, central pulse pressure, Zc, Pb and peak PQxZc were the hemodynamic factors associated with carotid IMT in older adults (Table 2). None of the metabolic factors were associated with carotid IMT in older adults (Table 2).

Associations between carotid IMT and hemodynamic and metabolic factors independent of confounders in all study participants

On-line supplemental Table S3 shows the multivariate associations between carotid IMT and hemodynamic and metabolic cardiovascular risk factors independent of confounders, in all study participants. Prior to the inclusion of hemodynamic or metabolic factors in the model, age was the primary determinant of carotid IMT, with mean arterial pressure, male sex, heart rate and BMI also showing significant associations (Table S3). In addition, age remained associated with carotid IMT independent of both hemodynamic and metabolic factors (Table S3). In separate models, none of the metabolic factors were associated with carotid IMT independent of confounders including age (Table S3). However, a number of hemodynamic factors (brachial systolic BP, brachial pulse pressure, central arterial systolic BP, central arterial pulse pressure, Zc, Pb, peak PQxZc, and TAC) were significantly associated with carotid IMT independent of confounders including age (Table S3). Furthermore, when included in the same model central arterial PP or Pb, showed strong associations with carotid IMT independent of confounders including age, whereas total/HDL cholesterol, was only weakly associated with carotid IMT (Table S3).

Associations between carotid IMT and hemodynamic and metabolic factors independent of confounders in different age groups

Table 3 (young), 4 (middle-aged) and 5 (older aged) show the multivariate associations between carotid IMT and hemodynamic and metabolic cardiovascular risk factors independent of confounders, in the three age groups. In young adults, prior to the inclusion of hemodynamic or metabolic factors in the model, age was the only determinant of carotid IMT (Table 3). In addition, age remained associated with carotid IMT independent of both hemodynamic and metabolic factors (Table 3). In separate models, total/HDL cholesterol and central arterial systolic BP were not associated with carotid IMT independent of confounders, whereas Pb remained associated with carotid IMT independent of confounders (Table 3). Furthermore, when included in the same model Pb, but not total/HDL cholesterol, was associated with carotid IMT (Table 3).

In middle-aged adults, prior to the inclusion of hemodynamic or metabolic factors in the model, age, BMI, MAP and HR were associated with carotid IMT independent of confounders (Table 4). Age, BMI and HR remained associated with carotid IMT independent of both hemodynamic and metabolic factors (Table 4). In separate models, brachial systolic BP, brachial pulse pressure, central arterial systolic BP, central arterial pulse pressure, Pb and peak PQxZc; but not blood glucose, triglycerides, and total/HDL cholesterol were associated with carotid IMT independent of confounders (Table 4). Central arterial systolic BP was the hemodynamic factor with the numerically greatest standardised beta value and lowest p-value. Hence, central arterial systolic BP was included in the final model. Although, not significantly associated with carotid IMT independent of confounders, total/HDL cholesterol had a numerically greater standardised beta value than triglycerides, and hence was included in the final model. When included in the same model, central arterial systolic BP, but not total/HDL cholesterol, was independently associated with carotid IMT (Table 4).

In older adults, prior to the inclusion of hemodynamic or metabolic factors in the model, age and MAP were associated with carotid IMT independent of confounders (Table 5). However, age was not associated with carotid IMT independent of both hemodynamic and metabolic factors (Table 5). Male sex and HR were associated with carotid IMT independent of both hemodynamic and metabolic factors and confounders (Table 5). In separate models, brachial systolic BP, brachial pulse pressure, central arterial systolic BP, central arterial pulse pressure, Zc, Pb, and peak PQxZc, but not total/HDL cholesterol were associated with carotid IMT independent of confounders (Table 5). Pb was the hemodynamic factor with the numerically highest standardised beta value and lowest p-value. Hence, Pb was the hemodynamic factor included in the final model. When included in the same model Pb, but not total/HDL cholesterol, was associated with carotid IMT in older adults (Table 5).

Hemodynamic and metabolic factors and odds of increased carotid IMT independent of confounders in different age groups

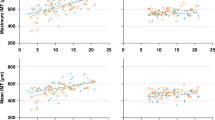

Figure 1 shows the impact of hemodynamic and metabolic cardiovascular risk factors on the odds of increased carotid IMT independent of confounders in the three age groups. In young adults, one unit increase in Pb, but neither age nor total/HDL cholesterol was associated with an increased carotid IMT (Fig. 1A). In middle-aged adults, one unit increase in BMI was the only cardiovascular risk factor significantly associated with an increased carotid IMT (Fig. 1B). In older adults, one unit increase in Pb and age, but not total/HDL cholesterol, sex or HR were associated with an increased carotid IMT (Fig. 1C).

The panels show the odds ratios of an increased carotid intima media thickness associated with one unit increase in hemodynamic and metabolic cardiovascular risk factors in young (age 35 years, A), middle-aged (age 35 to 59 years, B), and older adults (age ≥ 60 years, C). The models included both metabolic and hemodynamic factors (cSBP and Pb separately), where the most significant for each were chosen, and age and total/HDL cholesterol were included as comparators (final model as in Tables 3, 4 and 5). Also included in the models were sex, BMI, regular smoking, regular drinking, diabetes mellitus, treatment for hypertension, and heart rate. BMI body mass index, CI confidence interval, cSBP central arterial systolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate, IMT carotid intima-media thickness, OR odds ratio, Pb backward wave pressure, Total/HDLchol Total to HDL cholesterol ratio.

Performance of hemodynamic and metabolic factors in identifying individuals with increased carotid IMT in different age groups

Figure 2 shows the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis of individual hemodynamic and metabolic cardiovascular factors in identifying individuals with increased carotid IMT in the three different age groups. In young adults (Fig. 2A), only Pb significantly identified individuals with increased carotid IMT. In middle-aged adults (Fig. 2B), BMI, central arterial systolic BP, Pb, and age significantly identified individuals with increased carotid IMT. In older adults (Fig. 2C), age and Pb showed a trend to identify individuals with increased carotid IMT.

The figure shows the area under the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves showing the performance of individual hemodynamic or metabolic factors in identifying individuals with increased carotid IMT in young (age <35 years, A), middle-aged (age 35 to 59 years, B), and older adults (age ≥ 60 years, C). BMI body mass index, cSBP central arterial systolic blood pressure, HR heart rate, Pb backward wave pressure, Tot/HDLchol Total to HDL cholesterol ratio.

The impact of adding hemodynamic or metabolic factors to the base model, consisting of conventional risk factors, on predictive performance for an increased carotid IMT is shown in Table 6 for all participants as well as in young, middle-aged and older adults. The impact of adding age to the base model (excluding age) is included for comparison. In all participants and in young adults, Pb was the only factor to show a significant improvement in predictive performance for detecting an increased carotid IMT. In middle-aged adults, significant improvements in predictive performance for detecting an increased carotid IMT were shown with BMI, and Pb showed only weak significant improvements. In older adults, age and Pb showed significant improvements in predictive performance.

Discussion

In a community sample of adults of African ancestry living in Sub-Saharan Africa, we show that hemodynamic, and not metabolic cardiovascular risk factors are associated with carotid IMT. In addition, we showed that the primary hemodynamic and metabolic cardiovascular risk factors associated with carotid IMT differ across adult age groups. In young adults, hemodynamic factors (Pb) primarily impacted on carotid IMT. In older adults, Pb and age were associated carotid IMT; whereas in middle-aged adults, BMI, central arterial systolic BP and Pb were the primary factors associated with carotid IMT. Blood flow (SV and Q) and smoking status were not related to carotid IMT at any adult age. Moreover, plasma lipid concentrations were not associated with carotid IMT at any adult age. Only Pb was associated with increased carotid IMT in young adults; whereas in older adults age and Pb were determinants of increased carotid IMT, and in middle-aged adults, BMI was the primary determinant of increased IMT. Furthermore, significant improvements in predictive performance for detecting an increased carotid IMT were shown with Pb (young and older adults), and BMI (middle-aged adults). Hence, hemodynamic factors and not plasma lipid concentrations are the predominant cardiovascular risk factors associated with carotid IMT throughout the adult lifespan in individuals of African ancestry, and BMI only has an impact during middle-age.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to report on the hemodynamic and metabolic cardiovascular risk factors associated with carotid IMT in young adults of African ancestry living in Sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, our study is the first to report that the primary hemodynamic and metabolic cardiovascular risk factors associated with carotid IMT differ with age in a group of African ancestry. Although a large study in four Sub-Saharan African countries (Burkina Faso, Kenya, South Africa, Ghana) identified factors associated with carotid IMT, these data were limited to adults aged 40–60 years [10]. In this study, brachial systolic BP, but not LDL cholesterol, was associated with carotid IMT independent of confounders. Nevertheless, previous data assessing the cardiovascular risk factors associated with carotid IMT in young adults of African ancestry are lacking. In other populations (Chinese [11] and European [12]) the determinants of carotid IMT have been shown to differ according to age. In Chinese, the major determinants of carotid IMT beyond age and gender, were BMI at age 35–44 years, LDL cholesterol and brachial systolic BP at age 45–54 years, and brachial systolic BP at 55–64, 65–74 and aged 75 years or older [11]. In Europeans, aged 24 to 39 years, systolic BP, but neither LDL nor HDL cholesterol were independently related to carotid IMT [12]. However, in the same Europeans studied 6 years later, carotid IMT was associated with both brachial systolic BP and HDL cholesterol (inversely) [12]. Although data in adults aged<35 years are limited, it appears from the present study and a study in Europeans [12], that hemodynamic factors (Pb and brachial systolic BP respectively) are more important than metabolic factors (blood lipids) in young adults. As adults mature into middle-age, BMI (present study) and metabolic factors (HDL cholesterol in Europeans [12], LDL cholesterol in Chinese [11] seem to play a role in addition to hemodynamic factors. However, beyond middle-age, hemodynamic factors appear to predominate over metabolic factors [11] and present study.

Reasons for the differential impact of cardiovascular risk factors on carotid IMT with age are unclear. Nevertheless, hemodynamic factors consistently affect carotid IMT throughout the adult age range [11, 12, 23] and present study. On assessing the impact of hemodynamic factors, brachial pulse pressure in comparison to systolic, diastolic, and mean BP, may be the best predictor of carotid IMT in middle-aged (≥45 years) [24] and older (≥65 years) [24, 25] adults. Indeed, elevated brachial pulse pressure is associated with the progression of carotid IMT in older adults [26]. Moreover, increases in central arterial systolic BP, but not peripheral systolic BP, are associated with increases in carotid IMT in middle-aged and older adults [27]. Similarly, we show that central arterial pressures are associated with carotid IMT in middle-aged adults of African ancestry, and that in older adults central arterial pressures were numerically stronger than peripheral BP in association with carotid IMT. Moreover, we extend these findings to show that in young adults of African ancestry carotid IMT is associated with central arterial pressures (Pb) but not peripheral BP. The predominant effect of central arterial pressures on carotid IMT in young adults of African ancestry may be attributed to the high central arterial pressures and stiffness reported in young African adults [8]. Indeed, central arterial stiffness, central arterial pressure [8] and central arterial pressure augmentation [9] are elevated in African compared with European individuals, particularly among young adults [8].

Although, the role of wave reflection in cardiovascular disease is increasingly documented [28,29,30], our findings of a consistent association of central arterial pressures with carotid IMT in all adult age groups may be a consequence of vascular changes rather than a cause of increases in carotid IMT. In this regard, although intima-media thickening represents vascular remodelling and consequent decreases in lumen diameter in response to increases in BP [31], arterial narrowing in turn increases wave reflection and subsequently central arterial SBP and PP [28].

The predominant effect of hemodynamic rather than metabolic risk factors on carotid IMT in people of African ancestry is not surprising. In contrast to European populations, in Sub-Saharan African countries, hypertension, rather than dyslipidaemia, is the primary risk factor for CVD [7]. In this regard, in Sub-Saharan Africa, the prevalence of hypertension amongst adults is higher [5], whereas the prevalence of dyslipidaemia is lower [32], than in other regions of the world. Moreover, the proportion of individuals achieving BP control in Sub-Saharan Africa is lower than in other regions of the world [5]. Similarly, in Chinese populations, who also have lower cholesterol concentrations than European populations [33], hypertension has a higher impact on carotid IMT compared to dyslipidemia and diabetes [34].

Our data showing no relationships between lipid concentrations and carotid IMT independent of confounders in adults of African ancestry concur with findings reported in prior studies. In Nigerian Africans, BP was reported to be the strongest modifiable risk factor associated with carotid IMT [35]. In African populations, LDL cholesterol has a weaker negative impact on carotid IMT compared to in European populations [6]. Moreover, in four separate sub-Saharan African countries (Burkina Faso, Kenya, South Africa, Ghana), brachial systolic BP, but not LDL cholesterol, was associated with carotid IMT independent of confounders [10]. These data are supported by a recent systematic review which identified hypertension rather than dyslipidaemia, as the primary risk factor for CVD in Sub-Saharan African countries [7].

The lack of impact of blood lipids on carotid IMT in persons of African ancestry may be explained by the lower frequency of unfavourable lipid profiles (increased LDL cholesterol and triglycerides, and decreased HDL cholesterol) in Sub-Saharan Africa compared to Western Europe and North America [32]. Indeed, unfavourable lipid profiles are a major cause of atherosclerosis in communities of European ancestry [36]. Moreover, reductions in age-standardised death rates for ischemic stroke and ischemic heart disease in Europe between 1990 and 2019 have been attributed to decreases in total and LDL cholesterol concentrations [32].

The identification of a consistent association of hemodynamic factors with carotid IMT throughout the adult lifespan is of clinical relevance. In this regard, the high prevalence of hypertension, lack of awareness of hypertension and poor BP control in South Africans adults [37] is of concern. In particular, poor BP control and lack of awareness of hypertension seems to be particularly prevalent among young adults in South Africa [37]. As increased carotid IMT is associated with cardiovascular events (stroke, CLTI and CAD) in people of African ancestry living in Sub-Saharan African [15, 38,39,40], identification of factors that can be targeted to prevent increases in carotid IMT is paramount. In this regard, significant improvements in predictive performance for detecting an increased carotid IMT were shown with Pb in young and older adults. The present study therefore, highlights that in the prevention of cardiovascular disease it is imperative to screen for and manage high BP and hence Pb, throughout the adult lifespan. Moreover, screening for hypertension, managing hypertension and maintaining BP control are highly relevant to reduce cardiovascular risk in young adults of African ancestry.

There are several limitations to the present study. As the present study was cross-sectional in design, the relationships noted may not be cause and effect and may be attributed to residual confounding. Further studies evaluating the long-term impact of elevated BP on carotid IMT throughout the adult lifespan in individuals of African ancestry are therefore required. However, the present study provides the critical evidence in support of such future studies. Second, as more women than men participated in this study, the results may pertain more to women than to men. Notably, the high proportion of women compared to men was consistent across all three age groups. The strengths of our study include the thorough assessment of lipid profiles (total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol, total/HDL cholesterol ratio, and triglycerides) and hemodynamic factors (peripheral BP, central arterial pressures and components, and blood flow). Importantly, our data pertain to individuals of African ancestry living in Sub-Saharan Africa, and hence should not be extended to European or US cohorts.

Conclusions

In a population of African ancestry living in Sub-Saharan Africa, hemodynamic factors but not blood lipids, are associated with carotid IMT throughout the adult age range. Furthermore, the cardiovascular risk factors associated with carotid IMT differ across age groups. Hemodynamic factors, primarily central arterial pressures predominate in young and older adults; whereas BMI is the main contributor in middle-age.

Summary

What is known about the topic

-

Cardiovascular events occur 20 years earlier in individuals of African descent living in Sub-Saharan Africa compared to in individuals of European descent.

-

Carotid artery intima-media thickness (IMT), an important screening tool for cardiovascular disease, is lower in African populations living in Sub-Saharan Africa compared to other population groups.

-

The risk factors for cardiovascular disease differ between population groups and according to age.

What this study adds

-

In individuals of African descent living in South Africa:

-

Lipids are not associated with carotid IMT at any age.

-

Hemodynamic factors (primarily central arterial backward wave pressure) are associated with carotid IMT independent of confounders, particularly in young adults ( < 35years of age).

-

BMI is independently associated with carotid IMT only in middle-aged adults (35–59 years of age).

Data availability

All relevant data are contained within the manuscript.

References

GBD 2021 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403:2100–32.

Yuyun MF, Sliwa K, Kengne AP, Mocumbi AO, Bukhman G. Cardiovascular diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa compared to high-income countries: an epidemiological perspective. Glob Heart. 2020;15:15.

Shehu MN, Adamu UG, Ojji DB, Ogah OS, Sani MU. The pandemic of coronary artery disease in the Sub-Saharan Africa: what clinicians need to know. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2023;25:571–8.

Bibbins-Domingo K, Pletcher MJ, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Gardin JM, Arynchyn A, et al. Racial differences in incident heart failure among young adults. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1179–90.

Bots ML, Evans GW, Tegeler CH, Meijer R. Carotid intima-media thickness measurements: relations with atherosclerosis, risk of cardiovascular disease and application in randomized controlled trials. Chin Med J. 2016;129:215–26.

Nonterah EA, Crowther NJ, Klipstein-Grobusch K, Oduro AR, Kavousi M, Agongo G, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in the association between classical cardiovascular risk factors and common carotid intima-media thickness: an individual participant data meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e023704.

Abissegue G, Yakubu SI, Ajay AS, Niyi-Odumosu F. A systematic review of the epidemiology and the public health implications of stroke in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2024;33:107733.

Schutte AE, Kruger R, Gafane-Matemane LF, Breet Y, Strauss-Kruger M, Cruickshank JK. Ethnicity and arterial stiffness. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40:1044–54.

Chirinos JA, Kips JG, Roman MJ, Medina-Lezama J, Li Y, Woodiwiss AJ, et al. Ethnic differences in arterial wave reflections and normative equations for augmentation index. Hypertension. 2011;57:1108–16.

Nonterah EA, Boua PR, Klipstein-Grobusch K, Asiki G, Micklesfield LK, Agongo G, et al. Classical cardiovascular risk factors and HIV are associated with carotid intima-media thickness in adults from Sub-Saharan Africa: findings from H3Africa AWI-Gen study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e011506.

Su TC, Chien KL, Jeng JS, Chen MF, Hsu HC, Torng PL, et al. Age- and gender-associated determinants of carotid intima-media thickness: a community-based study. J Atheroscler Throm. 2012;19:872–80.

Koskinen J, Kähönen M, Viikari JSA, Taittonen L, Laitinen T, Rönnemaa T, et al. Conventional cardiovascular risk factors and metabolic syndrome in predicting carotid intima-media thickness progression in young adults. The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Circulation. 2009;120:229–36.

Woodiwiss AJ, Molebatsi N, Maseko MJ, Libhaber E, Libhaber C, Majane OH, et al. Nurse-recorded auscultatory blood pressure at a single visit predicts target organ changes as well as ambulatory blood pressure. J Hypertens. 2009;27:287–97. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e328317a78f

Woodiwiss AJ, Mmopi KN, Peterson V, Libhaber C, Bello H, Masiu M, et al. Distinct contribution of systemic blood flow to hypertension in an African population across the adult lifespan. Hypertension. 2020;76:410–9.

Kolkenbeck-Ruh A, Woodiwiss AJ, Monareng T, Sadiq E, Mabena P, Robinson C, et al. Complementary impact of carotid intima-media thickness with plaque in associations with noncardiac arterial vascular events. Angiology. 2020;71:122–30.

Yusuf SM, Norton GR, Peterson VP, Malan N, Gomes G, Mthembu N, et al. Attenuated relationships between indexes of volume overload and atrial natriuretic peptide in uncontrolled, sustained volume-dependent primary hypertension. Hypertension. 2023;80:147–59.

Segers P, O’Rourke MF, Parker K, Westerhof N, Hughes A, on behalf of the Participants of the 2016 Workshop on Arterial Hemodynamics: Past, present and future, 2017. Towards a consensus on the understanding and analysis of the pulse waveform: results from the 2016 Workshop on Arterial Hemodynamics: Past, present and future. Artery Res. 2017;18:75–80.

Mitchell GF, Wang N, Palmisano JN, Larson MG, Hamburg NM, Vita JA, et al. Hemodynamic correlates of blood pressure across the adult age spectrum: Noninvasive evaluation in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2010;122:1379–86.

Kelly R, Fitchett D. Noninvasive determination of aortic input impedance and external left ventricular power output: a validation and repeatability study of new technique. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;20:952–63.

Phan TS, Li JK, Segers P, Chirinos JA. Misinterpretation of the determinants of elevated forward wave amplitude inflates the role of the proximal aorta. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003069.

Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB Sr, D’Agostino RB Jr, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27:157–72.

Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB Sr, Steyerberg EW. Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat Med. 2011;30:11–21.

Oishi E, Kagiyama S, Ohmori S, Seki T, Maebuchi D, Kohno O, et al. Association of systolic blood pressure and pulse pressure with carotid intima thickness in elderly Japanese patients. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2013;35:273–8.

Liu J, Lin Q, Guo D, Yang Y, Zhang X, Tu J, et al. Association between pulse pressure and carotid intima-media thickness among low-income adults aged 45 years and older: A population-based cross-sectional study in rural China. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:547365.

Robertson AD, Heckman GAW, Fernandes MA, Roy EA, Tyas SL, Hughson RL. Carotid pulse pressure and intima media thickness are independently associated with cerebral hemodynamic pulsatility in community-living older adults. J Hum Hypertens. 2020;34:768–77.

Zureik M, Touboul P-J, Bonithon-Kopp C, Courbon D, Berr C, Leroux C, et al. Cross-sectional and 4-year longitudinal associations between brachial pulse pressure and common carotid intima-media thickness in a general population. The EVA Study. Stroke. 1999;30:550–5.

Sun P, Yang Y, Cheng G, Fan F, Qi L, Gao L, et al. Noninvasive central systolic blood pressure, not peripheral systolic blood pressure, independently predicts the progression of carotid intima-media thickness in a Chinese community-based population. Hypertens Res. 2019;42:392–9.

Townsend RR, Wilkinson IB, Schiffrin EL, Avolio AP, Chirinos JA, Cockcroft JR, et al. Recommendations for improving and standardizing vascular research on arterial stiffness. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2015;66:698–722.

Wang KL, Cheng HM, Sung SH, Chuang SY, Li CH, Spurgeon HA, et al. Wave reflection and arterial stiffness in prediction of 15-year all-cause and cardiovascular mortalities: a community based study. Hypertension. 2010;55:799–805.

Weber T, Wassertheurer S, Rammer M, Haiden A, Hametner B, Eber B. Wave reflections, assessed with a novel method for pulse wave separation are associated with end-organ damage and clinical outcomes. Hypertension. 2012;60:534–41.

Riccio SA, House AA, Spence JD, Fenster A, Parraga G. Carotid ultrasound phenotypes in vulnerable populations. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2006;4:44.

Pirillo A, Casula M, Olmastroni E, Norata GD, Catapano AL. Global epidemiology of dyslipidaemias. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18:689–700.

Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ounpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: Part II: variations in cardiovascular disease by specific ethnic groups and geographic regions and prevention strategies. Circulation. 2001;104:2855–64.

Ren L, Cai J, Liang J, Li W, Sun Z. Impact of cardiovascular risk factors on carotid intima-media thickness and degree of severity: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0144182.

Owolabi MO, Agunloye AM, Umeh EO, Akpa OM. Can common carotid intima media thickness serve as an indicator of both cardiovascular phenotype and risk among black Africans? Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22:1442–51.

Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, Ray KK, Packard CJ, Bruckert E, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. a consensus statement from the European atherosclerosis society consensus panel. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2459–72.

Woodiwiss AJ, Orchard A, Mels CMC, Uys AS, Nkeh-Chungag BN, Kolkenbeck-Ruh A, et al. High prevalence but lack of awareness of hypertension in South Africa particularly among men and young adults. J Hum Hypertens. 2025;39:111–9.

Kolkenbeck-Ruh A, Woodiwiss AJ, Naran R, Sadiq E, Robinson C, Motau TH, et al. Carotid intima-media thickness, but not chronic kidney disease independently associates with noncardiac arterial vascular events in South Africa. J Hypertens. 2019;37:795–804.

Holland Z, Ntyintyane L, Gill G, Raal F. Carotid intima-media thickness is a predictor of coronary artery disease in South African black patients. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2009;20:237–9.

Omisore A, Ogbole G, Agunloye A, Akinyemi J, Akpalu A, Sarfo F, et al. Carotid and vertebral atherosclerosis in West African stroke patients: findings from the stroke investigative research and education network. Niger Med J. 2022;63:98–111.

Acknowledgements

This study would not have been possible without the voluntary collaboration of the participants and the excellent technical assistance of Mthuthuzeli Kiviet, Nomonde Molebatsi, Nkele Maseko and Delene Nciweni.

Funding

This study was supported by the Medical Research Council of South Africa, the University Research Council of the University of the Witwatersrand, the South African National Research Foundation, and the Circulatory Disorders Research Trust. This work was supported by the Circulatory Disorders Research Trust, the University Research Council of the University of the Witwatersrand, the South African National Research Foundation and The South African Medical Research Council. Open access funding provided by University of the Witwatersrand.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NM and AJW contributed equally to this work. Conceptualization and design: NM, GRN, PHD and AJW; data acquisition: VRP, NHM, CDL, AK-R, GT, PS and AJW; data analysis: NM and AJW; data interpretation: NM, GRN, CDL, PS, PHD and AJW; drafting of the work: NM, GRN, VRP, NHM, CDL, AK-R, GT, PS, PHD, and AJW; substantial revision: NM, PHD and AJW. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Institutional review board statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) of the University of the Witwatersrand (protocol number: approval number: M02-04-72 and renewed as M07-04-69, M12-04-108, M17-04-01, and M22-03-93).

Informed consent

Participants provided informed, written consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Malan, N., Norton, G.R., Peterson, V.R. et al. Hemodynamic factors primarily impact on carotid IMT in young adults of African Ancestry in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Hum Hypertens (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-026-01119-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-026-01119-8