Abstract

Background

Diastolic dysfunction often precedes systolic dysfunction and provides opportunity for management strategies. We aim to present reference ranges for diastolic function parameters in stable preterm infants at 2 timepoints.

Methods

Ultrasound scans of clinically stable preterm infants < 30 weeks gestation with no antenatal or postnatal complications were analysed for left heart size, mitral blood flows, myocardial velocities and shortening during the early (3 to 21 days) and late (corrected gestation 34 to 37 weeks) neonatal period.

Results

92 early scans and 64 late scans were included. Mitral blood flow and myocardial velocities increased with augmented atrial function leading to higher EA and e’a’ ratios and with relatively high Ee’ ratio.

Conclusion

We present reference values for many left ventricular multimodal diastolic ultrasound parameters in preterm infants with uncomplicated fetal and neonatal development to guide prospective studies that explore diastolic function and diastolic heart failure in preterm infants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

There are an increasing number of neonatal clinicians trained in cardiac ultrasound to assess cardiopulmonary instability in the neonatal intensive care setting [1,2,3]. Typical clinical situations where cardiac ultrasound is used are hypotension, birth asphyxia, persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn, septic shock and assessing a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) [4]. This diagnostic approach by bedside clinicians has led to improved clinical outcomes with reduced rates of intraventricular haemorrhage and reduced mortality by targeting treatments towards the found pathophysiology [5,6,7].

Clinical decision-making is based on various ultrasound measurements of cardiac function, assessment of shunts and derivates of blood flows. Often a multimodality approach is used including 2D imaging, pulse wave Doppler, colour Doppler, tissue Doppler and strain rate imaging to be able to assess the different aspects of cardiovascular function and provide a comprehensive hemodynamic consultation [8].

The initial body of research in the field of neonatal hemodynamics focussed on blood flows, shunts and systolic function [9]. With increasing insight and advances in echocardiography technologies there is now a growing interest in diastolic performance, especially left ventricular (LV) diastolic function. Diastolic dysfunction often precedes systolic dysfunction and provides an opportunity for management directives in preterm infants with a PDA [10, 11], septic shock [12], extremely small for gestational age infants [13, 14] and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) [15, 16].

The aim of this study is to present reference ranges for diastolic ultrasound parameters recommended in recent algorithms to assess LV diastolic function in stable preterm infants during the early and late neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission period [17,18,19].

Methods

This retrospective observational study was undertaken at the John Hunter Children’s Hospital in Newcastle, Australia. Ethics approval was obtained from the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee to review the data of preterm infants < 30 weeks gestation admitted in the neonatal department over a 6-year epoch between 2017 and 2023. Our hospital is a tertiary centre with around 4500 deliveries per year, which also receives unwell neonates from 6 large regional hospitals and 11 rural birthing units in New South Wales.

Cardiac ultrasound scans were obtained for clinical indications or research studies using a Vivid E90 (GE healthcare, Chicago, Illinois USA) or Philips EPIQ 5 (Philips ultrasound, Andover, Massachusetts) ultrasound system and images were stored on a local image server with analysis workstation (Philips Ultrasound workspace/Tomtec TTA2 version 51.02 with Cardiac Performance Analysis version 1.4.0.156).

Echocardiography

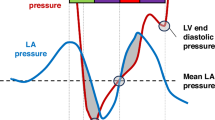

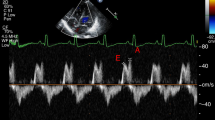

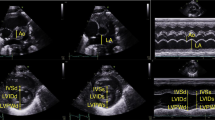

Images were acquired according to the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography and the targeted neonatal echocardiography recommendations and saved at 100 and 200 mm/s sweep speeds [8]. Ultrasound parameters of interest for multimodal LV diastolic function assessment are presented in Table 1, Figs. 1 and 2 and included cardiac size and shape, blood flow velocities, myocardial velocities and myocardial shortening. Most measurements were derived from a 3-beat average at 200 mm/s sweep speed. Partial fusion of the diastolic wave forms is common in preterm infants. When full fusion was apparent, we ensured the infant was settled using facilitated tucking and sucrose before further image acquisition was attempted. Doppler images with persistent full fusion between the early and late diastolic wave forms were omitted from analysis. Strain measurements were taken from apical 4-chamber images in adult orientation, from one heartbeat, and analysed by one investigator using a 6-segment (LV) or 3 segment (LA) model. Images were selected based on image quality criteria such as level of foreshortening, gain settings, clarity of borders, presence of artefacts, frame rate and tracking quality. Pulmonary vein Doppler was not part of our cardiac ultrasound protocol in this epoch.

S outflow wave, MV vti mitral valve velocity time integral, E early diastolic wave, A atrial contraction wave, DT deceleration time, DR deceleration rate, s’ systolic myocardial velocity, e’ early diastolic myocardial velocity, a’ atrial contraction myocardial velocity, IVRT isovolumetric relaxation time.

Reference patient population selection

All preterm infants with a gestational age < 30 weeks and who received at least one cardiac scan in the early NICU period were eligible. The early NICU period was defined as a postnatal age >72 h up till 21 days of age. The late NICU period was defined as a corrected gestational age (cGA) between 34 and 37 weeks. Infants with significant congenital abnormalities were excluded. Clinical data included non-invasive blood pressure measurements at the time of the scan and demographics like postnatal age and weight.

Stable preterm infants in the early NICU period were defined as having no antenatal complications that could affect fetal cardiac development such as gestational diabetes, fetal growth restriction, or prolonged (> 7 days) preterm rupture of membranes. They were born with a birth weight between the 10th and 90th percentile and with normal APGAR scores. At the time of the scan, they did not receive mechanical ventilation and the FiO2 was less than 25%. They had normal blood pressure and did not receive any cardiovascular medications (inotropes, steroids, inhaled nitric oxide, indomethacin, ibuprofen, paracetamol or diuretics). They also had no bradycardia or tachycardia (heart rate between 140 and 180 bpm) and on ultrasound they showed normal ejection fraction (>46%) and a closed or very small PDA (diameter < 0.5 mm). The same infants were eligible for analysis in the late NICU period if all above criteria were still met.

Statistical analysis

Parameters are expressed as mean, standard deviation and percentiles. Simple group analyses (early versus late) were conducted using an independent t-test and ANOVA. Analyses were performed on GraphPad version 6 (Prism, LaJolla, CA, USA) and SPSS version 21 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), and p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

During the 6-year period our unit admitted 657 preterm infants < 30 weeks gestation. Of those, 278 infants received at least one cardiac ultrasound scan in the early NICU period and a total of 389 scans were available for analysis. The flow diagram for inclusion is presented in the supplemental figure. Common reasons for exclusion were fetal growth restriction, higher oxygen requirement often in combination with the presence of a PDA, and concomitant medication use. There were 92 scans available for inclusion in the early NICU period and 64 in the late NICU period. The mean (SD) gestation was 27.6 (1.2) weeks and 51% were less than 28 weeks gestation, birth weight of 1025 (199) grams and a postnatal age of 7 [2] days at the early scan. Weight at time of the early cardiac ultrasound was 1004 (206) gram. The mean corrected gestational age at the late scan was 35.3 (0.7) weeks at a postnatal age of 59 [11] days, and a weight of 2316 (302) gram.

Feasibility was good for most diastolic parameters to average for some: PW velocities 92%, PW timings 77%, TDI velocities 94%, TDI timings 97%, volumes 99%, LV strain 81%, LA strain 85%.

The primary outcome with percentiles of reference ranges is presented in Table 2. Most parameters changed with increasing postnatal age. An increase in blood pressure was seen and increased mitral blood flow and myocardial velocities with augmented atrial function leading to higher EA and e’a’ ratios. In the late NICU period, a relatively high Ee ratio and E/SRE ratio was found, 15 [4] and 35 [2] respectively (Fig. 3). Heart rate showed similar ranges between the early and late NICU periods but with an increased time spent in systole.

Discussion

This study presents reference ranges of multimodal ultrasound parameters to assess LV diastolic function in a large cohort of stable preterm infants at 2 specific time where clinical assessments are frequently made during a NICU admission, either for acute deterioration (eg PDA, sepsis) or for screening before transfer or discharge. We found changes with increasing postnatal age with increased mitral inflow and atrial predominance like what was found in earlier cohorts. Di Maria et al. studied a large cohort of preterm infants <34 weeks around day 7 and at 36 weeks corrected gestational age. All admitted infants were eligible and thus included infants with a PDA, mechanical ventilation and those who later developed BPD [20]. They found that maturational changes in TDI velocities were independent of GA at birth and also of common neonatal complications. However, the study did feature a substantial number of significant outliers that could represent individual changes in diastolic function, and only reported pulse wave and tissue Doppler findings. LV diastolic function has a variety of determinants that are best captured with a multimodal approach with added strain measurements to detect changes in relaxation, recoil, stiffness and LA function simultaneously [21, 22].

Hirose et al. studied 30 stable preterm infants around day 28 and added strain rate analysis, with findings comparable to our data [23]. The authors compared preterm LV diastolic function to that of healthy term infants and hypothesised that preterm infants in the late NICU period have less efficient relaxation and possible increased LV stiffness when compared to healthy term infants, which could lead to impaired early filling with raised left atrial pressure. Our data showed similar findings with an increased Ee ratio and lower SRE at the late scan, and we hypothesise that part of these changes is related to altered cardiac development after preterm birth. Other studies have shown that preterm infants often reveal cardiac remodelling with a dilated, hypertrophied, and a more spherical heart at 36 weeks cGA, contributing to altered diastolic function [24, 25].

Heart rate was similar in both NICU periods, which might have contributed to the relative higher left atrial pressure found in the late NICU period. Fetal heart rate tends to reduce with increasing gestational age, but this does not occur when born preterm [26, 27]. Heart rate has an important effect on diastolic function and its ultrasound parameters. Physiological heart rate changes can affect mitral inflow patterns [28], and the diastolic duration decreases as heart rate increases [29, 30]. We found that the systolic to diastolic ratio increased over time, but further studies are needed to explore how cardiac cycle events changes with significant tachycardia eg. during disease, as we excluded infants with low and high heart rate for this study.

The limitation of our study is the lack of data in very young gestational age infants. Due to their very small cardiac size and relative high heart rate, we expect that changes in diastolic parameters will be disproportional to what is presented in this cohort. We also excluded measurements during the immediate transitional period due to the expected rapid and ongoing hemodynamic changes. One would require measurements at strict set time points (eg. every 6 h) after birth and adjust for various interventions and heart lung interactions to establish reference values during transition. Our ultrasound protocol did not include pulmonary vein Doppler or propagation velocity. Current adult algorithms to assess LV diastolic function recommend adding pulmonary vein Doppler if there are insufficient criteria to diagnose diastolic dysfunction or in special populations [17, 31]. In children with congenital heart disease, a machine learning model analysed ultrasound data and invasive measures of relaxation, end diastolic pressure and contractility [32]. Propagation velocity correlated most with relaxation, and strain measures performed well for LV filling pressure. Diastolic function is complex, and no single ultrasound parameter is likely to be able to accurately assign risk profiles [18, 19]. A multimodal approach, where an increasing number of parameters that fall outside the p10 or p90 range are used to identify diastolic dysfunction, will have the highest likelihood of detecting preterm infants at risk of respiratory or cardiovascular compromise during their NICU stay.

An important question that remains is which parameters to propose in an algorithm to diagnose diastolic dysfunction in preterm infants? In our previous work we proposed and tested an algorithm against signs and symptoms of heart failure in the early NICU period using LAvol, e’, Ee’ ratio, LASR and the presence of pulmonary hypertension [33]. Adult recommendations rely heavily on E and e’ as core criteria for diagnosing diastolic dysfunction [17]. In healthy adults, the mitral E remains relatively unchanged until older age [34]. On the contrary, in our study the mitral E wave nearly doubled over a 7 week period. Only IVRT and left atrial strain remained stable during the NICU period, but most other parameters changed during the NICU admission. These developmental changes will have to be incorporated in any proposed algorithm for preterm infants, likely with different criteria for the early and late NICU period.

Conclusion

We present reference values for a large number of multimodal LV diastolic ultrasound parameters in a cohort of preterm infants with strict classifications to be considered of normal fetal and postnatal development and clinically stable. We found that cardiac postnatal growth after preterm birth with a stable NICU period led to signs of increased LV stiffness and higher LV filling pressure. Cardiac function was maintained through reliance on good LA function. The data in this study can be used to guide further prospective studies that explore diastolic heart failure in preterm infants. Diastolic heart failure is a clinical syndrome characterised by respiratory deterioration and oedema, features recognisable to the neonatologists but not often diagnosed. Further insight into neonatal heart failure could provide an opportunity for early intervention in preterm infants at risk of cardiovascular complications.

References

Noori S, Ramanathan R, Lakshminrusimha S, Singh Y. Hemodynamic assessment by neonatologist using echocardiography: Primary provider versus consultation model. Pediatr Res. 2024;96:1603–8.

Hyland RM, Levy PT, Lai WW, McNamara PJ. Targeted Neonatal Echocardiography Based Hemodynamic Consultation in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: Subspecialty Evolution in Neonatology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2025;38:52–53.

Levy PT, Tissot C, Horsberg Eriksen B, Nestaas E, Rogerson S, McNamara PJ, et al. Application of neonatologist performed echocardiography in the assessment and management of neonatal heart failure unrelated to congenital heart disease. Pediatr Res. 2018;84:78–88.

Giesinger RE, McNamara PJ. Hemodynamic instability in the critically ill neonate: An approach to cardiovascular support based on disease pathophysiology. Semin Perinatol. 2016;40:174–88.

Roze JC, Cambonie G, Marchand-Martin L, Gournay V, Durrmeyer X, Durox M, et al. Association between early screening for patent ductus arteriosus and in-hospital mortality among extremely preterm infants. JAMA. 2015;313:2441–8.

Giesinger RE, Rios DR, Chatmethakul T, Bischoff AR, Sandgren JA, Cunningham A, et al. Impact of early hemodynamic screening on extremely preterm outcomes in a high-performance center. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2023;208:290–300.

Joye S, Kharrat A, Zhu F, Deshpande P, Baczynski M, et al. Impact of targeted neonatal echocardiography consultations for critically sick preterm neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2025;110:200–206

McNamara PJ, Jain A, El-Khuffash A, Giesinger R, Weisz D, Freud L, et al. Guidelines and recommendations for targeted neonatal echocardiography and cardiac point-of-care ultrasound in the neonatal intensive care unit: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2024;37:171–215.

Kluckow M, Seri I, Evans N. Functional echocardiography: an emerging clinical tool for the neonatologist. J Pediatr. 2007;150:125–30.

de Waal K, Costley N, Phad N, Crendal E. Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and diastolic heart failure in preterm infants. Pediatr Cardiol. 2019;40:1709–15.

de Waal K, Phad N, Collins N, Boyle A. Cardiac remodeling in preterm infants with prolonged exposure to a patent ductus arteriosus. Congenit Heart Dis. 2017;12:364–72.

Kharrat A, Nissimov S, Zhu F, Deshpande P, Jain A. Cardiopulmonary physiology of hypoxemic respiratory failure among preterm infants with septic shock. J Pediatr. 2024;278:114384.

Nayak V, Ashwal AJ, Lewis LE, Samanth J, Nayak K, Lalitha SS, et al. Subclinical myocardial dysfunction among fetal growth restriction neonates: a case-control study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2024;37:2392783.

Fouzas S, Karatza AA, Davlouros PA, Chrysis D, Alexopoulos D, Mantagos S, et al. Neonatal cardiac dysfunction in intrauterine growth restriction. Pediatr Res. 2014;75:651–7.

Rigotti C, Doni D, Zannin E, Abdelfattah AS, Ventura ML. Left ventricular diastolic function and respiratory outcomes in preterm infants: a retrospective study. Pediatr Res. 2023;93:1010–6.

Muhsen W, Nestaas E, Hosking J, Latour JM. Echocardiography parameters used in identifying right ventricle dysfunction in preterm infants with early bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a scoping review. Front Pediatr. 2023;11:1114587.

Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, Byrd BF 3rd, Dokainish H, et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;17:1321–60.

Nagueh SF. Left ventricular diastolic function: understanding pathophysiology, diagnosis, and prognosis with echocardiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:228–44.

de Waal K, Phad N, Crendal E. Echocardiography algorithms to assess high left atrial pressure and grade diastolic function in preterm infants. Echocardiography. 2023;40:1099–106.

Di Maria MV, Younoszai AK, Sontag MK, Miller JI, Poindexter BB, Ingram DA, et al. Maturational changes in diastolic longitudinal myocardial velocity in preterm infants. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1045–52.

Prasad SB, Holland DJ, Atherton JJ, Whalley G. New diastology guidelines: evolution, validation and impact on clinical practice. Heart Lung Circ. 2019;28:1411–20.

Venkateshvaran A, Tureli HO, Faxén UL, Lund LH, Tossavainen E, Lindqvist P. Left atrial reservoir strain improves diagnostic accuracy of the 2016 ASE/EACVI diastolic algorithm in patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: insights from the KARUM haemodynamic database. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;23:1157–68.

Hirose A, Khoo NS, Aziz K, Al-Rajaa N, van den Boom J, Savard W, et al. Evolution of left ventricular function in the preterm infant. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:302–8.

Phad NS, de Waal K, Holder C, Oldmeadow C. Dilated hypertrophy: a distinct pattern of cardiac remodeling in preterm infants. Pediatr Res. 2020;87:146–52.

Cox DJ, Bai W, Price AN, Edwards AD, Rueckert D, Groves AM. Ventricular remodeling in preterm infants: computational cardiac magnetic resonance atlasing shows significant early remodeling of the left ventricle. Pediatr Res. 2019;85:807–15.

Serra V, Bellver J, Moulden M, Redman CW. Computerized analysis of normal fetal heart rate pattern throughout gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34:74–9.

Alonzo CJ, Nagraj VP, Zschaebitz JV, Lake DE, Moorman JR, Spaeder MC. Heart rate ranges in premature neonates using high resolution physiologic data. J Perinatol. 2018;38:1242–5.

Harada K, Takahashi Y, Shiota T, Suzuki T, Tamura M, Ito T, et al. Effect of heart rate on left ventricular diastolic filling patterns assessed by Doppler echocardiography in normal infants. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:634–6.

Sarnari R, Kamal RY, Friedberg MK, Silverman NH. Doppler assessment of the ratio of the systolic to diastolic duration in normal children: relation to heart rate, age and body surface area. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:928–32.

Cui W, Roberson DA, Chen Z, Madronero LF, Cuneo BF. Systolic and diastolic time intervals measured from Doppler tissue imaging: normal values and Z-score tables, and effects of age, heart rate, and body surface area. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21:361–70.

Robinson S, Ring L, Oxborough D, Harkness A, Bennett S, Rana B, et al. The assessment of left ventricular diastolic function: guidance and recommendations from the British Society of Echocardiography. Echo Res Pr. 2024;11:16.

Nguyen MB, Dragulescu A, Chaturvedi R, Fan CS, Villemain O, Friedberg MK, et al. Understanding complex interactions in pediatric diastolic function assessment. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2022;35:868–77.e5.

de Waal K, Crendal E, Poon AC, Latheef MS, Sachawars E, MacDougall T, et al. The association between patterns of early respiratory disease and diastolic dysfunction in preterm infants. J Perinatol. 2023;43:1268–73.

Dalen H, Thorstensen A, Vatten LJ, Aase SA, Stoylen A. Reference values and distribution of conventional echocardiographic Doppler measures and longitudinal tissue Doppler velocities in a population free from cardiovascular disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:614–22.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KW had the primary responsibility for the primary version of this paper and was the author of the original draft of the manuscript. EP, NP and EC helped in data acquisition and analysis and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in studies used in this review.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ethical approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in studies used in this review.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Waal, K., Petoello, E., Crendal, E. et al. Reference ranges of left ventricular diastolic multimodal ultrasound parameters in stable preterm infants in the early and late neonatal intensive care admission period. J Perinatol 45, 920–926 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-025-02278-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-025-02278-1

This article is cited by

-

Biventricular adaptation after patent ductus arteriosus ligation

Pediatric Research (2025)

-

Diastolic function in newborn infants: understanding pathophysiology, diagnosis and clinical relevance

Pediatric Research (2025)