Abstract

The high-frequency and high-quality factor characteristics of bulk acoustic wave (BAW) resonators have significantly advanced their application in sensing technologies. In this work, a fluidic sensor based on a BAW resonator structure is fabricated and investigated. Embedded microchannels are formed beneath the active area of the BAW device without the need for external processes. As liquid flows through the microchannel, pressure is exerted on the upper wall (piezoelectric film) of the microchannel, which causes a shift in the resonant frequency. Using density functional theory, we revealed the intrinsic mechanism by which piezoelectric film deformation influences BAW resonator performance. Theoretically, the upwardly convex piezoelectric film caused by liquid flow can increase the resonant frequency. The experimental results obtained with ethanol solutions of different concentrations reveal that the sensor, which operates at a high resonant frequency of 2.225 GHz, achieves a remarkable sensitivity of 5.1 MHz/% (221 ppm/%), with an ultrahigh linearity of 0.995. This study reveals the intrinsic mechanism of liquid sensing based on BAW resonators, highlights the potential of AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film BAW resonators in liquid sensing applications and offers insights for future research and development in this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Owing to their excellent stability, resolution, and accuracy, as well as their low cost, compact size, and properties that allow devices to be easily interfaced with digital systems, resonators have attracted widespread interest in the detection and characterization of liquids. The ability to detect the concentration of liquids in a mixture is critical for many applications, such as water quality assessment1, chemical processing2, environmental monitoring3, and biosensing4. Resonator-based fluidic sensors monitor liquids through changes in the spectral response of the resonator, such as the quality factor (Q), resonance amplitude, and resonant frequency. Resonators commonly used as sensors can be divided into microwave resonators and piezoelectric resonators. Some studies have investigated split ring resonators (SRRs) and their derived resonator structures to realize high-sensitivity fluid sensors based on microwave resonators5,6. However, miniaturization, integration, anti-interference, and high sensitivity remain major challenges for fluid sensors in the detection and characterization of binary mixtures. The size of microwave resonators is larger than that of piezoelectric resonators. An increasing number of studies have investigated piezoelectric resonators to achieve compact size and high-sensitivity sensors based on piezoelectric resonators7,8.

Piezoelectric resonators are known for their precise control of frequency9. Bulk acoustic wave (BAW) resonators, as tiny piezoelectric devices manufactured by microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), have significant advantages as high-precision resonant sensors10, including smaller size, complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) compatibility, higher sensitivity, and low fabrication and measurement costs11. In addition, BAW resonators, as sensors that convert physical signals to electrical signals, have the advantage of high frequency, which can avoid interference. With the maturity of the BAW resonator manufacturing process, an increasing number of types of sensors based on BAW resonators have been designed. Using a BAW resonator, Yan et al. fabricated a mass sensor with a high sensitivity of 8–10 kHz cm2/ng at 3–4 GHz12. He et al. investigated the pressure sensing of a BAW resonator with a sensitivity of approximately −17.4 ppm kPa−1, 13.

BAW resonators also show great application potential in liquid sensors. Link et al. utilized a BAW resonator to detect water and 59% glycerol14. Vorobiev et al.15 and Rezazadeh et al.16 demonstrated the potential of the BAW resonator in characterizing the viscosity of liquids. Chen et al. fabricated a BAW resonator with c-axis tilted AlN films to achieve a sensitivity of 15 Hz cm2/μg for liquid loading17. In 2017, Liang et al. designed a glucose sensor with a sensitivity of 10.8 MHz/M through a glucose solution flowing on a BAW resonator18. Zhou et al. extended the application of BAW resonators in liquid viscosity sensing19. However, the intrinsic mechanism of resonant liquid sensors based on BAW resonators is lacking.

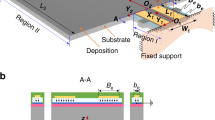

In this work, we presented a high-sensitivity liquid sensor with an embedded microchannel under the AlN/AlScN BAW resonator, with the same fabrication process (6 masks) as the BAW resonator, as shown in Fig. 1a. Through the application of DFT calculations and finite element methods (FEMs), it was discovered that the frequency drift of the BAW resonator is caused by the deformation of the piezoelectric film, which is influenced by the liquid flow beneath the resonator, as shown in Fig. 1b, c. Different frequency drifts can reflect the concentration and type of liquid. These experimental results are in good agreement with our simulation results.

Theory and design

Based on the frequency sensitivity of the BAW resonator, we designed embedded microchannels under BAW resonators for ultrasensitive sensing in liquids, as shown in Fig. 1a. This high-sensitivity liquid sensor has a low fabrication cost because it uses the same fabrication process (6 masks) as the BAW resonator. In this design, when liquid flows through the microchannel under the action of droplet pressure, the piezoelectric film under the microchannel will undergo mechanical deformation, as shown in Fig. 1b. The pressure formula of liquid flow on the microchannel wall is given by

where μ is the fluid viscosity, v is the average fluid velocity, l is the unit flow length, and dh is the hydraulic diameter of the microchannel. According to Formula (1), the deformation of the microchannel wall is directly influenced by the fluid viscosity.

The deformation of the piezoelectric film under the microchannel was investigated via the FEM when different liquids flow through the microchannel, as demonstrated in Fig. 2. As water with different velocities flows through the microchannel under the BAW resonator, the piezoelectric film deforms more as the flow speed increases, as depicted in Fig. 2a–c. Table 1 lists the peak displacement values of piezoelectric films under microchannels with various water velocities. When liquids with the same velocity are different, the deformations of the piezoelectric film are different. We select a variety of liquids (water, diethyl ether, ethanol, and ethylene glycol) to simulate the deformation of piezoelectric films under microchannels. Table 2 lists the viscosity parameters of these liquids at 25 °C. As shown in Fig. 2c–f, the deformation of the piezoelectric film increased as the viscosity of the liquid increased. Table 2 lists the peak displacement values of piezoelectric films under microchannels with various liquids flowing at 5 cm/s. These simulation results are consistent with the theoretical formula calculations. These different types of film deformation caused by different liquid flows directly affect the performance of the BAW resonator. These findings show that the embedded microchannels under BAW resonators have great application potential in ultrasensitive sensing in liquids.

As the liquid flows through the microchannels under the resonator, the film bulges because the main effect of the z-direction is pressure on the film. This film deformation directly changes the lattice structure of the film material, which changes its physical properties. The mechanical and piezoelectric properties of piezoelectric materials are intrinsically linked to the resonant frequency and the effective electromechanical coupling coefficient of BAW resonators20,21. These characteristics significantly increase the potential of BAW resonators for sensing applications.

To analyze the effect of piezoelectric film bulging (the main effect of the z-direction exerting pressure) on the performance of the resonator, the change in the AlN lattice at different pressures in the z-direction is calculated. Through the first-principles software Material Studio (MS), which is based on density functional perturbation theory (DFT)22, a 32-atom hexagonal supercell of wurtzite AlN was constructed and used in calculations, as shown in Fig. 1c. The generalized gradient approximation of Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (GGA–PBE) was utilized to calculate the exchange-correlation total energy23. The first Brillouin-zone integrals are performed on a Monkhorst–Pack mesh of 9 × 9 × 3 k-points, and the plane wave cutoff is set to 570 eV. For precise calculation, the crystalline structures of 2 × 2 × 2 AlN used for calculation are a-axis lattice constants (a) and c-axis lattice constants (c), as depicted in Fig. 1c.

The pressure directly affects the a-axis and c-axis lattice constants of the film material24. To calculate the change in the AlN lattice at different pressures in the z direction, the linear response method was utilized with the Cambridge Sequential Total Energy Package (CASTEP)22,23,25. As presented in Fig. 3a, the a and c lattice constants had opposite linear relationships with the z-direction pressure in the range of −2 GPa to 2 GPa. The a lattice constant has a negative linear relationship with the z-direction pressure, and the c lattice constant has a positive linear relationship with the z-direction pressure. This law is consistent with the deformation of some materials under z-direction pressure26.

a Lattice constants (a and c) of the AlN film dependence of the Z-direction exerted pressure; b lattice volume (V) and density (\(\rho\)) of the AlN film as a function of the z-direction pressure; c variation in the elastic constants of AlN in the residual z direction under pressure; d Piezoelectric coefficient (e24, e31, and e33) dependence of the z-direction exerted pressure. e Variations in the dielectric coefficients (\({\varepsilon }_{11}\) and \({\varepsilon }_{33}\)) of AlN in the z direction under pressure; f variation in important characterization parameters (fp, fs, K2, and \({K}_{t}^{2}\)) of AlN-BAW resonators in the z direction under pressure

Moreover, as depicted in Fig. 3b, the lattice volume (V) also has a positive linear relationship with the z-direction pressure, and the lattice density (\(\rho\)) has a negative linear relationship with the z-direction pressure. These lattice changes directly affect physical properties, such as piezoelectric properties and the elastic stiffness tensor.

To obtain the elastic constants under different pressures in the z-direction, crystalline structures deformed at different pressures were computed via CASTEP. The variation in the relative elastic constants with pressure (x) can also be found in the calculation results, as shown in Fig. 3c. In the range of −2 GPa to 2 GPa, this trend was fitted by quadratic Eqs. (2)–(6):

For the piezoelectric film used in BAW resonators, another crucial characteristic is the piezoelectric constant. Piezoelectricity is intimately linked to material polarization. In the absence of external fields, the overall macroscopic polarization (P) in a piezoelectric material consists of two components: strain-induced or piezoelectric polarization (\(\delta P\)) and spontaneous polarization (Ps). The piezoelectric polarization is defined as27

where e is the piezoelectric stress coefficient. Since precision BAW resonators mainly use e33 to create vibrations along the z-axis, in this work, we only examine polarizations along the (0001) axis. In the c-axis orientation of AlN, the piezoelectric polarization can be simply expressed as28

where \({s}_{1}={s}_{2}=({\rm{a}}-{a}_{0})/{a}_{0}\) is the in-plane strain and \({s}_{3}=({\rm{c}}-{c}_{0})/{c}_{0}\) is the strain along the c-axis. c0 and a0 are the lattice constants in the equilibrium structure. Equation (8) is a macroscopic phenomenological equation. From a microscopic perspective, we separate the clamped ion term and the internal relaxation term29:

where

The internal parameter u is defined as the bond length between anions and cations along the c-axis, and it determines the relative positions of atoms within the cell. Polarization changes caused linearly by relative sublattice shifts (variations in u) can be measured by the effective charge Z*:

where e is the electronic charge. According to formulas (9)–(13), the piezoelectric coefficients and the lattice constants are closely related.

Using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP), a set of piezoelectric coefficients was calculated for AlN lattices deformed under various pressures. After the influence of pressure applied in the z-direction on the piezoelectric coefficient is analyzed, their relationship can be approximated via a quadratic equation, as illustrated in Fig. 3d. The corresponding equations are fitted as follows:

Additionally, the effect of pressure applied in the z-direction on the dielectric permittivity is investigated, as shown in Fig. 3e. Within the pressure range of −2 GPa to 2 GPa, the variation in relative permittivity with pressure (x) in the z-direction is described by quadratic Eqs. (17) and (18) in the following form:

These physical parameter formulas directly reflect the effect of pressure applied in the z-direction on the performance of piezoelectric devices, such as BAW resonators and filters. For MEMS BAW resonators, the frequency and bandwidth are extremely tightly controlled. The frequency and bandwidth of BAW resonators are limited by the elastic constant (c33), dielectric permittivity (\({\varepsilon }_{33}\)), and piezoelectric coefficient (e33)30. The corresponding formula is as follows31:

where Z is the input impedance; w is the angular frequency; C0 is the electrostatic capacitance; d is the film thickness of the device; \({K}_{t}^{2}\) is the piezoelectric coupling constant of the transversely clamped material (\({K}_{t}^{2}={e}^{2}/({c}^{E}+\frac{{e}^{2}}{{\varepsilon }^{s}}){\varepsilon }^{s}={K}^{2}/{K}^{2}+1\), where \({K}^{2}={e}^{2}/{{c}^{E}\varepsilon }^{s}\) is the electromechanical coupling factor32); and k is the wavenumber. According to the variations in c and e with pressure, the variations in \({K}_{t}^{2}\) and K2 of AlN with pressure were calculated. They increase with increasing pressure, as shown in Fig. 3f. Since infinite input impedance corresponds to the parallel resonance of the lossless circuit, the corresponding acoustic frequency (fp) is given by

where \({v}^{D}=\sqrt{{c}^{E}/\rho ({K}^{2}+1)}\) is the acoustic velocity in the piezoelectric medium. The series resonant frequency (fs) is similarly obtained from Eq. (19) for Z = 0 and is therefore obtained from

In this sensor, which is based on BAW resonators, the first resonator frequency is used; therefore, n is equal to 0. Based on the 1 μm thick AlN film and the above equations, the ideal variations in fp and fs with pressure applied in the z direction can be obtained, as shown in Fig. 3f. They increase with increasing pressure applied in the z-direction, and the increasing trend of fs is greater than that of fp, which is in agreement with the experimental study of Zhou et al.19.

Results and discussion

Film Fabrication and Characterization

The piezoelectric properties of materials strongly influence the mechanical quality factors (QM), fp, and \({K}_{t}^{2}\) of piezoelectric resonators33. Wei Wu et al. reported that the \(-\Delta f/f\) of piezoelectric plate sensors increased with increasing electromechanical coupling constant k31 due to the extrinsic effect of polarization orientation switching at room temperature34. A. Talbi et al. also indicated that a better \({K}_{t}^{2}\) of the resonator could increase the sensitivity of the resonant sensor35. AlScN, which enhances the piezoelectric property of AlN, has been used to fabricate resonant sensors that are more sensitive than those based on AlN36. However, during the deposition of the AlScN film by the RF magnetron sputtering system, there are numerous abnormally oriented grains (AOGs). As demonstrated in Fig. 4a, atom force microscopy (AFM) revealed that the AOGs were large triangular pyramidal grains randomly distributed on the surface of the Al0.8Sc0.2N film. AOGs affect the piezoelectric and mechanical properties of AlScN films37.

AFM images of the a Al0.8Sc0.2N film, b AlN film, and c AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film. Piezoelectric amplitude curves of the d Al0.8Sc0.2N film, e AlN film, and f AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film. X-ray diffraction (XRD) rocking curves of the g Al0.8Sc0.2N film, h AlN film, and i AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film. Film-stress measurement curves of the j Al0.8Sc0.2N film, k AlN film, and l AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film

Therefore, this work utilized an AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film (500 nm AlN + 500 nm Al0.8Sc0.2N) to inhibit the growth of AOGs, which was investigated in our previous research38. A 1 μm AlN, 1 μm Al0.8Sc0.2N, and 1 μm AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film (500 nm AlN + 500 nm Al0.8Sc0.2N) was prepared through an RF magnetron sputtering system. During deposition, the distance between the target and the substrate was 50 mm, and the deposition temperature was 200 °C. According to the AFM characterization results, no AOGs exist on the AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film, and the AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film has a relatively small root-mean-square (rms) roughness (AlScN: 3.93 nm; AlN: 1.02 nm; AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N: 0.93 nm), as depicted in Fig. 4a–c. This smooth film surface reduces scattering losses, thereby improving the Q value of the resonator39. Through piezoresponse force microscopy (PFM), the piezoelectric properties (d33) of the AlN film, the Al0.8Sc0.2N film, and the AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film were measured, as shown in Fig. 4d-f. It is reasonable that d33 = 6.818 pC/N of the AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film is in the middle position among them. Moreover, the AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film improved the film quality of the piezoelectric layer in the BAW resonators. The full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the X-ray diffraction (XRD) rocking curves was used to characterize the film quality of these three piezoelectric films. As shown in Fig. 4g, h, and i), the FWHMs of the AlN film, Al0.8Sc0.2N film, and AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N film were 1.43°, 1.54°, and 1.29°, respectively, which confirmed that the AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film had better crystal quality. In addition, the AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film neutralized the residual stress from the AlN film and the Al0.8Sc0.2N film, as demonstrated in Fig. 4j–l. An AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film could be an alternative for regulating the residual stress of a film to reduce the damage caused by residual stress in MEMS devices.

Fabrication and experiments

Based on this sensor design, the fabrication process is illustrated in Fig. 5a. The high-sensitivity liquid sensor decreased the fabrication cost because the same fabrication process (6 masks) was used for the BAW resonators. (1) A 2.5 μm microchannel pool was etched by deep reactive ion etching (DRIE). (2) Then, the 3.5 μm released SiO2 layer was deposited via plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD), and the excess SiO2 beside the swimming pool was removed through chemical mechanical polishing (CMP). (3) An RF magnetron sputtering system was used to deposit a 25 nm AlN seed film and a 200 nm Mo film. The Mo film is subsequently patterned and etched as bottom electrodes. (4) AlN and Al0.8Sc0.2N piezoelectric films were deposited successively. Inductively coupled plasma (ICP) was used to etch the AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film to expose the pads of the bottom electrodes. (5) The top Mo film was deposited and patterned as top electrodes. The Al film was evaporated and then peeled off into the pad shape. (6) The AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film was etched to form a release hole, and SiO2 in the microchannel pool and liquid hole was released via VHF. The embedded microchannel sensor under the BAW resonators was fabricated as shown in Fig. 5b. A scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the cross-sectional BAW resonator is shown in Fig. 5c.

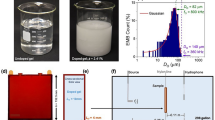

Before testing, the height variation of the AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film along the red line was measured via confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM), as shown in Fig. 6a, b. This film height variation could reflect the film deformation before and after the liquid flows through the microchannel. When liquid water flows through it, the film on the microchannel bulges due to upward pressure, as demonstrated in Fig. 6b. These measurement results are in agreement with the theoretical calculations and simulation results.

a Line of the height of the AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film; b height variation of the red line (a) before and after the liquid flows through the microchannel; c image of the setup of the liquid flow measurement; d measured behavior for liquid flow; e impedance signals measured as microchannel-filled air and water; and f impedance signals measured for different concentrations of microchannel-filled ethanol

The liquid flow impacts on the BAW resonator were measured via the setup illustrated in Fig. 6c. This setup pushed a fixed amount of liquid through the spiral annotation tube to drop into the liquid hole. The droplet pressure drives the solution to flow through the microchannel, as shown in Fig. 6d. First, the BAW resonator was measured in air by a Keysight network analyzer (N5222B) with a Cascade Microtech GSG probe station (Cascade, USA). This impedance signal measured as microchannel-filled air is depicted in Fig. 6e. While the GSG probe remained tested, we pushed water into the liquid hole. Therefore, the impedance signal can eliminate the influence of other interference. As shown in Fig. 6e, fp increased at 3 MHz, and Qp decreased sharply from 184 to 47.9 as water flowed. This reduction in Qp occurred because the liquid hindered the vibration of the BAW resonator and increased the energy loss of the BAW resonator. This frequency draft originating from the bulged AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film confirms the accuracy of the first-principles calculation.

Subsequently, different concentrations of ethanol solutions were used to measure the sensitivity of this sensor. Figure 6f shows the impedance variations of the BAW resonator at different ethanol mass percentage concentrations (10%, 20%, 30%, and 40%). A noticeable frequency shift is observed with increasing ethanol concentration, and the quality factor (Qp) fluctuates with increasing ethanol concentration. Figure 7a shows the variation in fp as a function of the ethanol concentration. After linear approximation, the measured frequency variation under ethanol concentration was 0.51 MHz/%, and the corresponding concentration sensitivity (\(\Delta f\)/\({f}_{p}\)) was 211 ppm/%, with an ultrahigh linearity of 0.995, as illustrated in Fig. 7b.

Conclusions

Based on the pressure of liquid flow on the microchannel wall, this work designed and fabricated a high-sensitivity resonant liquid sensor with an embedded microchannel under BAW resonators. Through FEM simulations, it was determined that at the same flow rate, different viscosities of liquids caused different pressures on the microchannel wall. As the viscosity of the liquid increased, the deformation of the membrane wall also increased. When the liquid flows in the microchannel, the main force that causes the film to bulge is the z-direction pressure. Through first-principles calculations, we characterized the physical properties of the 32-atom hexagonal supercell of wurtzite AlN under different pressures in the z direction. These calculation results reveal the variation rule of the lattice constant, density, elastic constant, piezoelectric constant, etc. Subsequently, we revealed the intrinsic mechanism of how the z-direction pressure affects the performance of AlN-based BAW resonators. Theoretically, the upwardly convexness of the piezoelectric film caused by liquid flow can increase the resonator frequency.

During fabrication, the liquid sensor used an AlN/Al0.8Sc0.2N composite film to effectively suppress the abnormal orientation of the AlScN grains. The experimental results with different concentrations of ethanol reveal that our sensor, operating at a high resonant frequency of 2.225 GHz, achieves a remarkable sensitivity of 5.1 MHz/% (221 ppm/%) with an ultrahigh linearity of 0.995. These results of the frequency shift trend of the resonator are in agreement with the theoretical prediction. This study reveals the intrinsic mechanism of force sensing based on BAW resonators and offers insights for future research and development in this field.

References

Connolly, D. & Paull, B. Rapid determination of nitrate and nitrite in drinking water samples using ion-interaction liquid chromatography. Anal. Chim. Acta 441, 53–62 (2001).

Nikolic-Jaric, M. et al. Microwave frequency sensor for detection of biological cells in microfluidic channels. Biomicrofluidics 3, 34103 (2009).

Liang, Y. et al. Wireless microfluidic sensor for metal ion detection in water. ACS Omega 6, 9302–9309 (2021).

Schwerthoeffer, U., Weigel, R. & Kissinger, D. in 2013 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Workshop Series on RF and Wireless Technologies for Biomedical and Healthcare Applications. 1–3 (IEEE).

Javed, A., Arif, A., Zubair, M., Mehmood, M. Q. & Riaz, K. A low-cost multiple complementary split-ring resonator-based microwave sensor for contactless dielectric characterization of liquids. IEEE Sens. J. 20, 11326–11334 (2020).

Mohammadi, S., Adhikari, K. K., Jain, M. C. & Zarifi, M. H. High-resolution, sensitivity-enhanced active resonator sensor using substrate-embedded channel for characterizing low-concentration liquid mixtures. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 70, 576–586 (2021).

Rey-Mermet, S., Lanz, R. & Muralt, P. Bulk acoustic wave resonator operating at 8 GHz for gravimetric sensing of organic films. Sens. Actuators B 114, 681–686 (2006).

Xuan, W. et al. Bulk acoustic wave resonator based wireless and passive pressure sensor. Vacuum 178, 109433 (2020).

Benes, E., Gröschl, M., Burger, W. & Schmid, M. Sensors based on piezoelectric resonators. Sens. Actuators A 48, 1–21 (1995).

Zhao, Z. et al. Design considerations for frequency shifts in a laterally finite FBAR sensor in contact with the newtonian liquid. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 67, 2402–2412 (2020).

Ebrahimi, A., Withayachumnankul, W., Al-Sarawi, S. & Abbott, D. High-sensitivity metamaterial-inspired sensor for microfluidic dielectric characterization. IEEE Sens. J. 14, 1345–1351 (2013).

Yan, Z. et al. Material and device properties of ZnO-based film bulk acoustic resonator for mass sensing applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 253, 9372–9380 (2007).

He, X. L. et al. Film bulk acoustic resonator pressure sensor with self temperature reference. J. Micromech. Microeng. 22, 125005 (2012).

Link, M. et al. Solidly mounted ZnO shear mode film bulk acoustic resonators for sensing applications in liquids. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 53, 492–496 (2006).

Vorobiev, A. & Gevorgian, S. Ferroelectric film bulk acoustic wave resonators for liquid viscosity sensing. J. Appl. Phys. 114, 084106 (2013).

Rezazadeh, G. & Ghanbari, M. On the mathematical modeling of a MEMS-based sensor for simultaneous measurement of fluids viscosity and density. Sens. Imaging 19, 1–20 (2018).

Chen, Y.-C., Chang, W.-T., Kao, K.-S., Yang, C.-H. & Cheng, C.-C. The liquid sensor using thin film bulk acoustic resonator with c-axis tilted AlN films. J. Nanomater. 2013, 2–2 (2013).

Liang, J. et al. On-chip nanofluidic integration of acoustic sensors towards high Q in liquid. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 203501 (2017).

Zhou, Y. et al. Investigation of film bulk acoustic resonators for sensing applications in liquid environment. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 213501 (2022).

Yu, H., Pang, W., Zhang, H. & Kim, E. S. in IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems. 28–31 (IEEE).

Wang, J., Zheng, Y. & Ansari, A. Ferroelectric aluminum scandium nitride thin film bulk acoustic resonators with polarization-dependent operating states. Phys. Status Solidi (RRL) 15, 2100034 (2021).

Segall, M. D. et al. First-principles simulation: ideas, illustrations and the CASTEP code. J. Phys. 14, 2717 (2002).

Clark, S. J. et al. First principles methods using CASTEP. Z. Kristallogr. Crystall. Mater. 220, 567–570 (2005).

Wickramaratne, D., Bernstein, N. & Mazin, I. I. Impact of biaxial and uniaxial strain on V 2 O 3. Phys. Rev. B 100, 205204 (2019).

Pfrommer, B. G., Côté, M., Louie, S. G. & Cohen, M. L. Relaxation of crystals with the quasi-Newton method. J. Comput. Phys. 131, 233–240 (1997).

Sharma, H., Kreisel, J. & Ghosez, P. First-principles study of PbTiO 3 under uniaxial strains and stresses. Phys. Rev. B 90, 214102 (2014).

Nye, J. F. Physical Properties of Crystals: Their Representation by Tensors and Matrices. (Oxford university press, 1985).

Posternak, M., Baldereschi, A., Catellani, A. & Resta, R. Ab initio study of the spontaneous polarization of pyroelectric BeO. Phys. Rev. Lett. 64, 1777 (1990).

Dal Corso, A., Posternak, M., Resta, R. & Baldereschi, A. Ab initio study of piezoelectricity and spontaneous polarization in ZnO. Phys. Rev. B 50, 10715 (1994).

Liu, Y. et al. Materials, design, and characteristics of bulk acoustic wave resonator: a review. Micromachines 11, 630 (2020).

Rosenbaum, J. F. Bulk Acoustic Wave Theory and Devices. (Artech House Acoustics Library, 1988).

Hashimoto, K.-Y. RF Bulk Acoustic Wave Filters for Communications. (Artech House, 2009).

Zhang, S. & Yu, F. Piezoelectric materials for high temperature sensors. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 94, 3153–3170 (2011).

Wu, W., Shih, W. Y. & Shih, W.-H. Enhancing detection sensitivity of piezoelectric plate sensor by increasing transverse electromechanical coupling constant. J. Appl. Phys. 114, 064505 (2013).

Talbi, A. et al. ZnO/quartz structure potentiality for surface acoustic wave pressure sensor. Sens. Actuators A 128, 78–83 (2006).

Wang, H., Zhang, L., Zhou, Z. & Lou, L. Temperature performance study of SAW sensors based on AlN and AlScN. Micromachines 14, 1065 (2023).

Liu, C. et al. Evaluation of the impact of abnormal grains on the performance of Sc0. 15Al0. 85N-based BAW resonators and filters. J. Micromech. Microeng. 32, 034002 (2022).

Gu, X. et al. Experimental and theoretical studies of effective piezoelectric coefficients of 2-2 connectivity AlN/AlScN composite piezoelectric films. Compos. Commun. 38, 101502 (2023).

Bousquet, M. et al. in IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium. 1–4 (IEEE).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFF0723000), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62201405) and the Key R&D Program of Hubei Province under Grant No. 2022BAA049 and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2023T160496). The numerical calculations in this paper were performed on the supercomputing system at the Supercomputing Center of Wuhan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, X., Liu, Y., Qu, Y. et al. Ultrasensitive liquid sensor based on an embedded microchannel bulk acoustic wave resonator. Microsyst Nanoeng 10, 143 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-024-00790-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-024-00790-6