Abstract

Solid-state nanopores (SSNPs) have emerged as a transformative platform in nanotechnology and biotechnology, yet their application is limited by the lack of cost-effective, reproducible fabrication technology. Here, we introduce a novel SpacerX process for wafer-scale fabrication of well-ordered nanopore arrays inspired by spacer patterning used in the standard semiconductor manufacturing process. This technique is intrinsically scalable and features tunable nanopore dimensions, with an open-pore rate exceeding 99.9%, even in an academic cleanroom. We successfully demonstrated a silicon nitride (Si3N4) nanopore array with a diameter of ~30 nm, non-uniformity below 10%, and spacing of 10 μm. By further reducing the spacer size, the nanopore diameter can be minimized to 10 nm. We fabricated multi-pore devices and showed that dual-pore devices offer higher detection throughput for DNA molecules. The SpacerX process only involves two ultraviolet lithography steps with one mask, and can be readily adopted by commercial foundries, thus opening the possibility of mass-producing sub-10 nm SSNPs at extremely low cost.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Solid-state nanopores (SSNPs) have attracted considerable interest due to their potential for various applications, including single-molecule sensing, DNA sequencing, nanofiltration, energy conversion, and storage, etc.1,2,3,4,5,6. Compared to biological nanopores, SSNPs offer superior mechanical and chemical stability, making them particularly suitable for high-stress operational environments. Moreover, widely tunable pore sizes are available, ranging from a few to several hundred nanometers, further broadening the application space7,8,9.

Up to now, scalable, cost-effective, and reproducible fabrication technology for SSNP remains elusive. Lithography is the most widely used technique for defining nanoscale structures at scale. Deep ultraviolet (DUV) lithography can achieve resolution below 100 nm, while extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography is able to define features below 10 nm10,11. Unfortunately, EUV lithography is extremely expensive and not readily available. As a result, various techniques for fabricating nanoscale SSNPs have been developed, including focused ion beam12, transmission electron microscopy-based drilling13,14,15, electron beam lithography (EBL)16,17, heavy ions18, and laser etching, etc19,20. These technologies suffer from low throughput, high cost, and poor scalability. Chemical and electrochemical techniques, such as dielectric breakdown21,22,23,24 and metal-assisted chemical etching25, nanobubble electrochemical deposition, and nanopipette-based glass nanopores26,27,28,29 have also been explored. While some of them are potentially scalable, these methods are limited in terms of precision, reproducibility, and uniformity. Current wafer-scale fabrication methods mainly include self-assembly, nanoimprint lithography (NIL), and wet etching based on silicon-on-insulator (SOI) wafers. Self-assembly enables low-cost and sub-10 nm pore sizes but suffers from poor pore size uniformity and spatial control25,30. NIL reduces per-pore cost, nevertheless, the initial fabrication of high-quality stamps typically mainly relies on EBL and dry etching on hard substrates31, resulting in high stamp fabrication costs. Moreover, any adjustment to pore size or distribution requires the production of a new stamp. Alternatively, using materials with special lattice structures lowers costs but limits control over nanopore array distribution32. Wet etching on SOI wafers is compatible with semiconductor processes and at low cost33,34, but pore size uniformity is limited, with variations of several tens of nanometers for ~30 nm pores33. Spacer patterning is commonly used in the semiconductor industry to define features with resolution well beyond lithography limit35. Inspired by this approach, we developed a novel wafer-scale technology (“SpacerX” process) for manufacturing silicon nitride (Si3N4) nanopore arrays. The spacer process forms structures via self-aligned deposition and anisotropic etching, achieving precise and uniform dimensions independent of lithography limits. High-uniformity deposition and controllable etching ensure excellent across-wafer consistency. Fully compatible with wafer-scale production, the spacer technique enables reliable fabrication of sub-lithographic features without advanced lithography tools.

The SpacerX process involved only a single mask and two steps of UV lithography. We demonstrated a uniform nanopore array with ~30 nm diameter and 10 µm spacing. The nanopore size can be tuned by varying process parameters, and 10 nm diameter was realized. Si3N4 nanopore devices with multi-pore structures were successfully built. Similar to conventional spacer patterning techniques, the SpacerX process is fully compatible with wafer-scale mass production, making it intrinsically scalable and readily transferable to commercial foundries. This opens the possibility for the large-scale fabrication of sub-10 nm SSNPs at extremely low cost and high uniformity. Furthermore, the compatibility of this process with standard CMOS manufacturing lines significantly enhances its potential for future integration into CMOS systems, greatly improving the scalability and applicability of solid-state nanopore technologies.

Results

Process flow of Si3N4 nanopore array fabrication

Figure 1 illustrates our process for fabricating Si3N4 nanopore array. A < 100> silicon (Si) wafer is used as the substrate, onto which Si3N4 is deposited via low-pressure chemical vapor deposition (LPCVD) in Step 1. The Si wafer refers to silicon wafers of varying sizes (e.g., 4-inch, 8-inch, etc.). In Steps 2 and 3, amorphous silicon (α-Si) is deposited using plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD). The α-Si layer is then patterned through UV lithography and inductively coupled plasma (ICP) etching, forming strip structures with a width of a and a spacing of b, which directly determine the periodicity of the nanopore array. In Steps 4 and 5, atomic layer deposition (ALD) and ICP etching are employed to form alumina (Al2O3) sidewalls, which adhere to the α-Si strips. The thickness of the Al2O3 sidewalls directly defines the final nanopore size. Another layer of α-Si is then deposited to encapsulate the Al2O3 sidewalls, forming a sandwich structure (Step 6). After chemical-mechanical polishing (CMP), the Al2O3 sidewalls are exposed and create a nanostrip array in the top view (Step 7). In Step 8, the wafer is rotated 90°, and Steps 2–7 are repeated to create a crossed nanostrip array. Significantly, the same mask used in Step 2 can be employed during this process, with the mask rotated 90°. Step 9 involves a dilute hydrochloric acid bath to selectively etch the Al2O3 nanostrips, resulting in dual-layer perpendicular spacers (“SpacerX”) that serve as nanopore etching masks. Due to the high etching selectivity between amorphous Al2O3 and silicon-based materials in acidic solutions, both the SpacerX structures and the Si3N4 membrane remain intact during this step. Following ICP etching, nanopores are fabricated in the Si3N4 layer (Step 10). Finally, the SpacerX is removed in Step 11 using alkaline solutions, yielding a well-ordered array of Si3N4 nanopores, with periodicity determined by a and b, as shown in Step 11.

Process development

To validate the feasibility of the proposed process, we implemented Steps 2–7 of the complete flow. A 50 nm thick Al2O3 layer was deposited, with α-Si strips having a width and spacing of 5 μm, and approximately 100 nm thick silicon oxide (SiO2) was employed as the target etching layer. Following the etching of the Al2O3 nanostrips, spacers with a 5 μm spacing were successfully obtained, as shown in the scanning electron microscope (SEM) images in Fig. 2a, with the corresponding cross-sectional view in Fig. 2b. In Step 6, a ~25 nm SiO2 layer was deposited before α-Si deposition to mitigate stress. This approach was applied in every α-Si deposition step. To preserve the integrity of the target film, a portion of the α-Si layer was left unetched. After the removal of the Al2O3 nanostrips, a single-layer spacer approximately 50 nm wide and 300 nm deep was created, as shown in Fig. 2b. Subsequent etching using ICP with CF4 gas removed the residual α-Si entirely, as shown in Fig. 2c. Over-etching, for 60% and 100% more etching time, resulted in deeper spacers, as illustrated in Fig. 2d, e, with bottom widths of approximately 20 nm and 30 nm, respectively. These etching conditions led to a characteristic “V”-shaped profile, significantly narrower than the initial 50 nm width.

During the etching process, CF4 gas is ionized into CF4 plasmas36. Notably, in ICP etching, the etchant particles do not strike the wafer surface perfectly vertically, as depicted in the etching model in Fig. 2f. Due to the reduced dimensions of the spacers and their high aspect ratio (approximately 1:6 in this case), it becomes increasing difficult for etchant particles to reach the bottoms of the spacers at larger deflection angles. However, the overall impact on the spacers remains minimal. As observed in Fig. 2c–e, longer etching times lead to deeper spacers without significantly compromising the spacer formation. Additionally, we noted that the “V”-shaped openings widened progressively with increased etching time. This widening is attributed to the poor collimation of some etchant particles, which primarily strike the upper edges of the spacers. A portion of the etchant particles undergoes collisions near the “V” opening and subsequently “slides” toward the bottom of the spacer, as illustrated in Fig. 2f. This behavior resembles the “micro-trenching effect” commonly observed in ICP etching37. As the “V”-shaped opening expands, it enhances the direct impact or sliding of additional etchant particles toward the bottom of the spacer, thereby improving etching efficiency. In conclusion, by controlling the thickness of the Al2O3 sidewalls, we can modulate the dimensions of the etched spacers and even achieve structures thinner than the Al2O3 thickness. This capability offers a reliable approach for fabricating nanopores with diameters smaller than the 50 nm spacers used as the starting template.

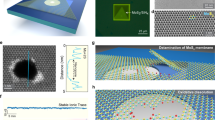

Fabrication of Si3N4 nanopore array

After the initial validation, we implemented the complete process flow. Figure 3 shows the step-by-step process SEM images, with the wafer designated as Wafer 1. In this case, the Al2O3 thickness was maintained at 50 nm, with the α-Si strip width a and spacing b both set to 10 μm. The Si3N4 film used had a thickness of 45 nm. As shown in Fig. 3a, b, we achieved a well-defined vertical α-Si layer and tightly adhered Al2O3 sidewalls after UV lithography and ICP etching, corresponding to Steps 3 and 5 in Fig. 1. Figure 3c shows the sandwiched Al2O3 sidewall structure formed after the second α-Si deposition (Step 6 in Fig. 1). After the first CMP step, Al2O3 nanostrips were exposed on the wafer surface, as shown in Fig. 3d (Step 7 in Fig. 1). The nanostrip width matched the ALD-deposited Al2O3 thickness (~50 nm). Subsequently, the wafer was rotated 90°, and Steps 2–7 in Fig. 1 were repeated. Figure 3e illustrates the structure after the repetition of Step 3 (top view, with the wafer tilted by 20°). Upon patterning the second α-Si layer, the exposed Al2O3 nanostrips reappeared, confirming the successful intersection of the two Al2O3 nanostrips during Steps 4–5 of Fig. 1. Following Step 8 in Fig. 1, the wafer was immersed in dilute hydrochloric acid, resulting in the formation of SpacerX structure, as shown in Fig. 3f (Step 9 in Fig. 1). We refer to the upper spacer as USP and the bottom one as BSP. The SpacerX structure was taken along the dashed lines in Fig. 3f, as shown in Fig. 3g (Section 1: USP ~ 80 nm, BSP ~ 230 nm) and Fig. 3h (Section 2: USP ~ 210 nm, BSP ~ 250 nm). Both spacers exhibited good verticality and retained the Al2O3 thickness of 50 nm. However, due to the micron-level precision of the CMP equipment used, nanoscale thickness uniformity was less than ideal, resulting in some variation in spacer thickness. A similar situation can be observed in Fig. 1 (Supplementary Information). Overall, the fluctuation range of the two-layer spacer thickness is at least between 80 and 330 nm. Despite this, the SpacerX structure successfully formed the foundation for the nanopore structure.

The α-Si layer strip (a), coated with Al2O3 sidewalls (b) and re-coated with α-Si (c). a–c were obtained from dummy wafers. d Top view of Al2O3 nanostrip structure after CMP. e The structure after Step 3 of Fig. 1 was repeated (wafer tilted by 20°). Top view of the SpacerX (f) and cross-sections at Sections 1 g and 2 h. The top view SEM image of the SpacerX after etching i, and the wafer tilted by 20° (j). Si3N4 nanopore array (k), a single nanopore (l), and the enlarged nanopore. The nanopore by reducing the etching time to 60% (m) and increasing the etching time to 150% (n). The scale bars are a–j 100 nm, k 50 μm, l 500 nm, the enlarged image of l, m and n 100 nm

Unetched Al2O3 residues led to the formation of horizontal spacers (Fig. 3g, h), the impact of which will be analyzed in the discussion. After ICP etching (Step 10 in Fig. 1), SEM images (Fig. 3i) revealed an increase in the spacer dimensions compared to those shown in Fig. 3f. Tilting the wafer by 20° (Fig. 3j, top view) allowed for the visualization of the intersection points of the two spacers (within the dashed box). Following the removal of the SpacerX, an array of nanopores with a 10 μm spacing was obtained, as shown in Fig. 3k (Step 11 in Fig. 1). A magnified SEM image of a single nanopore revealed an elliptical shape with dimensions of approximately 50 nm × 35 nm, as shown in Fig. 3l and the enlarged image. The nanopore morphology is discussed extensively in the next section. Notably, each nanopore was enclosed within a square cavity, which was formed because the alkaline solution used to remove the SpacerX structure selectively etched the silicon but not the Si3N4 layer. This selective etching created cavities in the Si substrate at the locations of the nanopores. These periodic cavities, visible in Fig. 3k, confirmed the presence of nanopores, as their absence would have prevented etching into the Si substrate. Interestingly, the cavity dimensions were large enough to be observed via optical microscopy, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, where approximately 10,000 nanopores were analyzed in a local region. The optical data indicated that only 9 nanopores were missing, resulting in an open-pore rate exceeding 99.9%. Additionally, based on our earlier validation experiments (Fig. 2d, e), we hypothesize that nanopore diameters could be tuned by adjusting the etching time. Reducing the etching time to 60% of the original led to nanopores with feature sizes of approximately 25 nm (Fig. 3m), while increasing the etching time to 150% produced nanopores with feature sizes of approximately 70 nm (Fig. 3n). This shows that nanopore sizes can be precisely tuned within a specific range using the same SpacerX structure.

Process optimization

We constructed a three-dimensional model for the nanopore etching process, as shown in Fig. 4a. In this model, the BSP is in direct contact with the Si3N4 layer, restricting etchant particles movement along the Y-direction, while the USP is suspended, restricting etchant particles motion in the X-direction. To assess the uniformity of the nanopores, we sampled and statistically analyzed 30 nanopores from the central, middle, and near-edge regions of the wafer, as shown in Fig. 4b. The nanopores predominantly exhibited an elliptical shape, with significant variation in dimensions. The non-uniformity in the length (L) and width (W) of the nanopores was measured as 54.6 ± 4.7 nm (average ± standard deviation) and 43.3 ± 4.0 nm, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3g, h, one of the major contributing factors to this variability is the thickness variation of the spacers, which inevitably leads to more significant non-uniformity in the nanopore dimensions. The USP is suspended, allowing well-aligned etchant particles to pass directly through the top and BSP and strike the Si3N4 film vertically, as shown in Fig. 4a. However, some etchant particles with poor alignment, although deviating from 90°, still manage to graze the two spacer structures at an angle and strike the Si3N4 film. Specifically, some of those etchant particles can first strike the sidewall of the USP, may strike the BSP secondarily, and then “slide” down to the Si3N4 film. This leads to some particles striking the Si3N4 film in the X-direction, deviating more from the intended area.

a Schematic diagram of the SpacerX etching model. b Statistical chart of the L and W of the nanopores of Wafer 1, with an inset illustrating the L and W. SEM cross-sectional images of the BSP and USP (c, d), and the corresponding SEM image of the nanopores (e) of Wafer 2. SEM cross-sectional images of the BSP and USP (f, g), and the corresponding SEM image of the nanopore (h) of Wafer 3. i Statistical chart of the L and W of the nanopores of Wafer 3, with an inset illustrating the L and W. Film materials: c and f correspond to Fig. 3g; d and g correspond to Fig. 3h; e and h correspond to Fig. 3l. All of the SEM image scale bars are 100 nm

The ICP etching particles generally exhibit good uniformity in the etching chamber, including their concentration and collimation. Therefore, there should be a quantitative relationship between the dimensions of the nanopores and SpacerX. We define the coefficient \({R}_{{BSP}}\) as the reduction ratio of the W of the nanopore critical dimension (\(C{D}_{{pore\_W}}\)) relative to BSP (\(C{D}_{{BSP}}\)). As seen in Fig. 2c–e, the spacer at the bottom gradually increases with etching time, indicating that \({R}_{{BSP}}\) is proportional to the etching time (\({t}_{{etch}}\)). Thus, the etching ratio coefficient for BSP is expressed via Eq. (1):

Similarly, the coefficient \({R}_{{USP}}\) is defined as the reduction ratio of the L of the nanopore critical dimension (\(C{D}_{{pore\_L}}\)) relative to USP (\(C{D}_{{USP}}\)). Thus, the etching ratio coefficient for USP is calculated using the following Eq. (2):

In addition, we define a coefficient β in Eq. (3):

Under conditions where the etchant particles are perfectly collimated at a 90° angle, the shape of the nanopores should closely match the SpacerX pattern. The dimensions may, however, vary due to chemical reactions between the etchant particles and the material being etched. In this case, the coefficient β should be close to 1, since both \(C{D}_{{pore\_L}}\) and \(C{D}_{{pore\_W}}\) will scale proportionally to \(C{D}_{{USP}}\) and \(C{D}_{{BSP}}\). We summarize the data from Fig. 4b in Table 1 and calculate the β value as 1.27 ± 0.17. This value is significantly higher than the theoretical expectation, which can be attributed to the practical limitation of non-collimated etchant particles. The interaction between the SpacerX geometry and the etchant particles thus contributes to this deviation. Moreover, the non-uniformity in the SpacerX thickness further introduces fluctuations in the β value. While the fluctuations in the thickness of USP and BSP reach up to ~200 nm (Fig. 3g, h, Fig. 1 of Supplementary Information), the variation in β is only 0.17, indicating that while β is affected by the SpacerX thickness, the sensitivity is low.

Based on the empirical value of β, to achieve a near-circular pore shape where \(C{D}_{{pore\_W}}\) and \(C{D}_{{pore\_L}}\) are both 43.3 nm, we calculated that \(C{D}_{{USP}}\) should be reduced to ~39 nm. However, due to the poor uniformity of CMP on Wafer 1, we could not establish a direct relationship between the thickness ratio of USP and BSP and the nanopore dimensions. Considering that a thinner spacer facilitates the penetration of etchant particles, we intentionally reduced the thickness of the USP. Additionally, before the process, we replaced the CMP equipment with one offering better uniformity, ensuring that the post-processing non-uniformity was <10%. Two parameters were designed: Wafer 2 with USP ~ 80 nm and BSP ~ 250 nm (Fig. 4c, d) and Wafer 3 (the photograph is shown in Fig. 4 of Supplementary Information) with USP ~ 140 nm and BSP ~ 250 nm (Fig. 4f, g, Fig. 3 of Supplementary Information). Both showed significant improvements in thickness uniformity. To further minimize the nanopore size, we reduced the etching time to 90% of the original. After the nanopore etching process, we observed that the nanopore of Wafer 2 transitioned from elliptical to closer to square, as shown in Fig. 4e, with characteristic dimensions of approximately 34 nm × 34 nm. We hypothesize that the thinner spacer allowed more etchant particles to directly hit the Si3N4 film according to the SpacerX pattern, resulting in square-shaped nanopores. For Wafer 3, more circular nanopores were achieved (Fig. 4h), with the non-uniformity reduced to 34.4 ± 2.2 nm and 34.2 ± 2.7 nm, respectively (Fig. 4i, 60 nanopores from the central, middle, and near-edge regions of Wafer3). This indicates that the non-uniformity is now controlled within a 10% range. Similarly, we present the related statistical and calculation data in Table 2, where we obtain a β value of 1.26 ± 0.06. This consistency in the β value indicates that nanopore size and shape can be systematically designed and controlled based on this coefficient. The β may vary with the performance of the ICP equipment or the thickness of the SpacerX, as different equipment can exhibit varying collimation properties of the etchant particles. However, we can integrate SpacerX thickness to summarize similar coefficients for nanopore size design across different equipment.

Nanopore shrinking process

We developed a strategy to reduce the nanopore size further. Using the SpacerX of Wafer 3, we performed ALD of SiO2, as illustrated in Fig. 5a. The deposited SiO2 layer had a thickness of 10 nm, which reduced the USP from approximately ~39 nm to ~19 nm (Fig. 5b). Additionally, the width of the BSP was reduced from ~50 nm to ~30 nm (Fig. 5c). As a result, we successfully fabricated nanopores with a diameter of approximately 10 nm (Fig. 5d). While ALD has been previously employed in other studies to shrink nanopores38, it generally not only reduces the nanopore diameter but also increases the nanopore thickness. In contrast, our method leverages the ALD process to shrink the size of the SpacerX without affecting the final nanopore thickness, as the processed SpacerX is removed at the end. This approach has been experimentally validated, demonstrating its effectiveness in producing smaller nanopores while preserving the desired geometry.

a Schematic diagram of the nanopore shrinking process. The SEM images top view (b, c) sectional view of the narrowed SpacerX. d The SEM image of the nanopore fabricated by the shrinking SpacerX. Film materials: c corresponds to Fig. 3g; d corresponds to Fig. 3l. All of the SEM image scale bars are 100 nm

Nanopore Devices Fabrication

After successfully fabricating a nanopore array with a 10 μm period on a 4-inch Si wafer, we further build Si3N4 nanopore devices. In Step 8 of Fig. 1, following the formation of intersecting Al2O3 nanostrips, a SiO2 layer was deposited on the chip, as illustrated in Fig. 6a. The target nanopore regions were then exposed through UV lithography and etching. Afterward, the Al2O3 nanostrips were removed via a water bath etching process. SEM images following Al2O3 etching are shown in Fig. 6b, c, which correspond to single-pore and dual-pore devices. Figure 5a, b (Supplementary Information) provides the microscope images of the single-pore and dual-pore nanopore etching windows. In the next step, Si3N4 windows are created on the backside of the wafer through backside lithography alignment and alkaline solution water bath etching (Fig. 6 of Supplementary Information). The alkaline solution simultaneously removes the SpacerX and SiO2 mask from the chip surface (Supplementary Information, Fig. 5c, d). This customized process enabled the successful fabrication of single-pore and dual-pore devices. The chip used here is from Wafer 3, with consistent etching conditions, resulting in a nanopore diameter of ~34 nm.

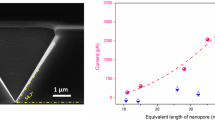

As shown in Fig. 7a, we measured the conductivity of six single- and six dual-pore Si3N4 nanopore devices, yielding values of 216.6 ± 15.4 nS and 457.4 ± 22.8 nS, respectively, comparable to previous studies39. The conductivity of the nanopores is directly proportional to the number of pores6. Additionally, both device types exhibited a linear relationship between current and voltage, as shown in the inset in the lower-right corner of Fig. 7a. A photograph of a single-pore device is displayed in the upper-left corner inset. Furthermore, we used the two types of nanopore devices to detect the circular phiX174 viral DNA using 2 M LiCl at 140 mV, as depicted in Fig. 7b. The following insets show a schematic of DNA translocation through a Si3N4 nanopore and a typical translocation event. The curves in Fig. 7b exhibit the current within 20 s after stabilization for both devices. The dual-pore device demonstrates a higher capture rate while translocation current magnitudes remain similar. However, this dual-pore structure introduces higher noise levels, which may be attributed to the superposition of noise sources from both pores, as well as increased parasitic capacitance or resistance. Additionally, cross-talk and signal interference through the shared electrolyte may contribute to the noise. In future work, we plan to increase the spacing between the two pores to reduce cross-talk, and to incorporate passivation layers and optimize membrane design to minimize overall noise sources. Figure 7c and d present scatter plots and corresponding histograms of dwell time and current for translocation events over 5 minutes for both device types. For the single-pore device (Fig. 7c), the dwell time and current predominantly fall within the ranges of 0.6–0.8 ms and 0.8–1 nA, with 212 events recorded (~0.7 events per second). A similar distribution is observed for the dual-pore device (Fig. 7d), with dwell times and currents in the ranges of 0.6–0.8 ms and 0.8–1 nA, respectively, and 521 events recorded (~1.7 events per second). The capture rate of the dual-pore device is nearly 2.4 times that of the single-pore device, exceeding the theoretical value of 2. This improvement may be attributed to the dual-pore distribution, which disperses the DNA concentration, thereby increasing the likelihood of DNA translocation through the nanopores. Consequently, the dual-pore device enables more data collection within the same time and energy consumption.

a The conductivities of single and dual-pore devices, with the bottom-right inset displaying their current-voltage curves, and the top-left inset showing the image of a single Si3N4 nanopore device. b The translocation current signals of circular phiX174 viral DNA through single and dual-pore devices. The bottom inset shows the schematic illustrations of the DNA translocating through the Si3N4 nanopore and a typical event. Scatter plots of translocation events and corresponding histogram of dwell time versus peak current of single (c) and dual-pore (d) devices, respectively. All experiments were performed in 2 M LiCl, pH 8.0, at 140 mV

Discussion and Conclusion

In summary, we developed a wafer-scale method (“SpacerX”) for fabricating nanopore arrays using mature semiconductor processing techniques. This manufacturing technology is intrinsically manufacturable with an open-pore rate of up to 99.9%, even in an academic cleanroom. We successfully demonstrated a Si3N4 nanopore array with a 10 μm pitch, an approximate diameter of 30 nm, and a size non-uniformity of less than 10%. Due to the compatibility of this fabrication strategy with semiconductor processes, the shape and size of the nanopores can be effectively tailored by precisely adjusting the width and thickness of the SpacerX structures. Using this approach, we fabricated nanopores with elliptical, near-square, and circular geometries. Varying the crossing angle or thickness of the SpacerX allows for further customization. For instance, crossing angles less than 90° can yield diamond-shaped nanopores, while increasing the width of one spacer can result in elliptical nanopores with specific aspect ratios. Upon shrinking the SpacerX, we were able to reduce the nanopore diameter to approximately 10 nm. In the future, the size of the nanopore can be further tuned by controlling the ALD Al2O3 thickness during the Al2O3 nanostrips fabrication. With this approach, nanopores ranging from a few to hundreds of nanometers can be made at roughly the same cost. We can extend this SpacerX nanopore fabrication method beyond Si3N4 to other materials, provided that appropriate etching recipes are chosen. We have also established a correlation between nanopore size and SpacerX thickness, facilitating the design and optimization of nanopore shapes and sizes for various applications. Compared to existing methods, this approach leverages mature CMOS processing techniques to achieve high controllability over nanopore size, shape, and distribution. It does not rely on any stamps, and enables low-cost fabrication within a laboratory environment, while also being readily transferable to commercial foundries.

Figure 4b and i reveal several sources of non-uniformity in the fabricated nanopores: (1) SpacerX thickness variation: inconsistent spacer thickness leads to uneven restriction of etchant particles, contributing to larger size variability (Fig. 4b). (2) SpacerX shape non-uniformity: as observed in Fig. 3g, h and Fig. 4c, d, f, g, the SpacerX exhibits irregularities in both vertical and horizontal directions, likely due to uneven etching of the Al2O3 film. This non-uniformity can be attributed to the etching equipment. Etching systems with better uniformity could mitigate this issue and enhance the consistency of nanopore formation. (3) Roughness of α-Si sidewalls: supplementary Fig. 7 highlights the presence of slight roughness along the sidewalls of the α-Si strips, which may cause variations in the SpacerX profiles and influence etching uniformity. Addressing this roughness through process optimization could further improve nanopore size uniformity in future work.

Nanopore devices based on the SSNP array were built, and dual-pore devices were shown to enhance the throughput of biomolecule detection. In conclusion, our novel wafer-scale SpacerX process leveraging mature semiconductor processing technology opens up the possibility for reproducibly mass-producing uniform SSNPs at extremely low cost.

Methods

Materials

PhiX174 Virion ssDNA was procured from New England Biolabs. The <100> Si wafers (1–10 Ω·cm resistivity, 500 μm thick, double-side polished) with a 45 nm low-stress Si3N4 layer were purchased from Suzhou Boyan Micro Nano Co., Ltd., China.

Si3N4 nanopore fabrication process

The etching of Al2O3 nanostrips was carried out using an 80 °C diluted hydrochloric acid solution (30% HCl: H2O = 1:4) for approximately 5 hours to ensure complete over-etching of the Al2O3 nanostrips. The Si windows were opened with a 50% KOH: H2O (1:1) alkaline solution and heated at 80 °C for about 10 hours. All processes involving α-Si, SiO2, Al2O3, and Si3N4 thin films followed the default equipment recipes.

Measurement Methods

The Si3N4 nanopore devices were assembled and secured using a fixture, incorporating two Teflon plastic electrolytic cells and two perfluorinated rubber rings. This setup allows electrolytes in the left and right electrolytic cells to conduct through the nanopore devices. The phiX174 Virion ssDNA was introduced to the ground electrode side and diluted in a 2 M LiCl solution (pH 8.0) to achieve a final concentration of ~5 nM. Two AgCl electrodes connected the solutions in both cells to the amplifier (Element srl), with signal recording managed by the Elements Data Reader software. The amplifier operated at a sampling frequency of 200 kHz with a 2 kHz filter.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Lee, K. et al. Recent Progress in Solid‐State Nanopores. Adv. Mater. 30, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201704680 (2018).

Meyer, N., Torrent, J. & Balme, S. Characterizing Prion‐Like Protein Aggregation: Emerging Nanopore‐Based Approaches. Small Methods, https://doi.org/10.1002/smtd.202400058 (2024).

Pal, S., Naik, A., Rao, A., Chakraborty, B. & Varma, M. M. Aptamer-DNA Origami-functionalized solid-state nanopores for single-molecule sensing of G-Quadruplex formation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 5, 8804–8810 (2022).

Schmid, S. An external speed control for nanopore reads. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 1261–1262 (2023).

Tsou, T.-Y. & Hsu, J.-P. Nanofiltration through cylindrical nanopores end-grafted with polyelectrolytes. J. Membr. Sci. 686, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2023.121968 (2023).

Hu, R. et al. Solid-state quad-nanopore array for high-resolution single-molecule analysis and discrimination. Adv. Mater. 35, e2211399 (2023).

Liu, H., Zhou, Q., Wang, W., Fang, F. & Zhang, J. Solid‐state nanopore array: manufacturing and applications. Small 19, https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202205680 (2022).

Zhou, S. et al. A DNA-Schiff base functional nanopore sensing platform for the highly sensitive detection of Al3+and Zn2+ions. Dalton Trans. 52, 1524–1532 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Solid-State Nanopore/Nanochannel Sensors with Enhanced Selectivity through Pore-in Modification. Anal. Chem. 96, 2277–2285 (2024).

ASML. TWINSCAN NXT:2100i. at https://www.asml.com/en/products/duv-lithography-systems/twinscan-nxt2100i (2023).

Fomenkov, I. et al. Light sources for high-volume manufacturing EUV lithography: technology, performance, and power scaling. Adv. Opt. Technol. 6, 173–186 (2017).

Li, J. et al. Ion-beam sculpting at nanometre length scales. Nature 412, 166–169 (2001).

van den Hout, M. et al. Controlling nanopore size, shape and stability. Nanotechnology 21, https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/21/11/115304 (2010).

Russo, C. J. & Golovchenko, J. A. Atom-by-atom nucleation and growth of graphene nanopores. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 109, 5953–5957 (2012).

Yang, H., Saqib, M. & Hao, R. Single-Entity Detection With TEM-Fabricated Nanopores. Front. Chem. 9, https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2021.664820 (2021).

Pedone, D. et al. Fabrication and electrical characterization of a pore–cavity–pore device. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 22, https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/22/45/454115 (2010).

Chou, Y.-C., Masih Das, P., Monos, D. S. & Drndić, M. Lifetime and stability of silicon nitride nanopores and nanopore arrays for ionic measurements. ACS Nano 14, 6715–6728 (2020).

Olejniczak, A. & Rymzhanov, R. A. From nanohole to ultralong straight nanochannel fabrication in graphene oxide with swift heavy ions. Nat. Commun. 14, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36357-8 (2023).

Zvuloni, E., Zrehen, A., Gilboa, T. & Meller, A. Fast and deterministic fabrication of Sub-5 nanometer solid-state pores by feedback-controlled laser processing. ACS Nano 15, 12189–12200 (2021).

Gilboa, T., Zvuloni, E., Zrehen, A., Squires, A. H. & Meller, A. Automated, ultra‐fast laser‐drilling of nanometer scale pores and nanopore arrays in aqueous solutions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201900642 (2019).

Ying, C., Ma, T., Xu, L. & Rahmani, M. Localized nanopore fabrication via controlled breakdown. Nanomaterials 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12142384 (2022).

Xie, W. et al. Direct optical observation of DNA clogging motions near controlled dielectric breakdown silicon nitride nanopores. Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 349, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2021.130796 (2021).

Bandara, Y. M. N. D. Y., Karawdeniya, B. I., Dutt, S., Kluth, P. & Tricoli, A. Nanopore fabrication made easy: a portable, affordable microcontroller-assisted approach for tailored pore formation via controlled breakdown. Anal. Chem. 96, 2124–2134 (2024).

Waugh, M. et al. Solid-state nanopore fabrication by automated controlled breakdown. Nat. Protoc. 15, 122–143 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. Achieving a sub-10 nm nanopore array in silicon by metal-assisted chemical etching and machine learning. International Journal of Extreme Manufacturing 3, https://doi.org/10.1088/2631-7990/abff6a (2021).

Chen, K. et al. Super‐resolution detection of DNA nanostructures using a nanopore. Adv. Mater. 35, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202207434 (2023).

Kong, J., Zhu, J., Chen, K. & Keyser, U. F. Specific Biosensing Using DNA Aptamers and Nanopores. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201807555 (2018).

Sze, J. Y. Y., Ivanov, A. P., Cass, A. E. G. & Edel, J. B. Single molecule multiplexed nanopore protein screening in human serum using aptamer modified DNA carriers. Nat. Commun. 8, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01584-3 (2017).

Chau, C. et al. Probing RNA conformations using a polymer–electrolyte solid-state nanopore. ACS Nano 16, 20075–20085 (2022).

Smith, B. D., Patil, J. J., Ferralis, N. & Grossman, J. C. Catalyst self-assembly for scalable patterning of sub-10 nm ultrahigh aspect ratio nanopores in silicon. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 8043–8049 (2016).

Lee, D.-S., Song, H.-W., Choi, C.-G. & Jung, M. Y. Pore-size reduction protocol for SiN membrane nanopore using the thermal reflow in nanoimprinting for nanobio-based sensing. J. Biomed. Opt. 19, https://doi.org/10.1117/1.Jbo.19.5.051211 (2014).

Lang, X., Wang, X., Ma, J. & Qiu, T. Flexible fabrication of new-type porous anodic alumina membranes with tunable geometric features by low-cost nanoimprint lithography. Nanoscale Adv. 3, 2918–2923 (2021).

Chen, Q., Wang, Y., Deng, T. & Liu, Z. Fabrication of nanopores and nanoslits with feature sizes down to 5 nm by wet etching method. Nanotechnology 29, 085301 (2018).

Hong, H. et al. Study on the controllability of the fabrication of single-crystal silicon nanopores/nanoslits with a fast-stop ionic current-monitored TSWE method. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 9, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-023-00532-0 (2023).

Cheng, K. et al. Air spacer for 10 nm FinFET CMOS and beyond. in 2016 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) (2016).

Mogab, C. J., Adams, A. C. & Flamm, D. L. Plasma etching of Si and SiO2—The effect of oxygen additions to CF4 plasmas. J. Appl. Phys. 49, 3796–3803 (1978).

Schaepkens, M. & Oehrlein, G. S. Asymmetric microtrenching during inductively coupled plasma oxide etching in the presence of a weak magnetic field. Appl. Phys. Lett. 72, 1293–1295 (1998).

Chen, P. et al. Atomic layer deposition to fine-tune the surface properties and diameters of fabricated nanopores. Nano Lett. 4, 1333–1337 (2004).

Kowalczyk, S. W., Wells, D. B., Aksimentiev, A. & Dekker, C. Slowing down DNA translocation through a nanopore in lithium chloride. Nano Lett. 12, 1038–1044 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was jointly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant No. 62188102, the National Key R&D Program of China No. 2022YFF1202002, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant No. 62174107.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lihuan Zhao, Xin Zhao conceived the project. Lihuan Zhao proposed the idea of SpacerX process and designed the nanopore fabrication methodology. Jiajun Wang developed the device measurement method. Lihuan Zhao performed the fabrication and measurement process. Lihuan Zhao analyzed the data. Xin Zhao supervised the project. Lin-Sheng Wu provided constructive ideas. Lihuan Zhao wrote the manuscript, and all authors read and discussed it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, L., Wang, J., Wu, LS. et al. Wafer-scale fabrication of solid-state nanopore array with a novel SpacerX process. Microsyst Nanoeng 11, 129 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-00979-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-00979-3