Abstract

Terahertz communication systems demand versatile devices capable of simultaneously controlling propagating waves and surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) in far-field (FF) and near-field (NF) channels, yet existing solutions are constrained by volatile operation, single-function limitations, and the inability to integrate NF and FF functionalities. Here, we present a nonvolatile reconfigurable terahertz metasurface platform leveraging the phase-change material Ge2Sb2Te5(GST) to achieve on-demand dual-channel modulation—a first in the terahertz regime. By exploiting the stark conductivity contrast of GST between amorphous and crystalline states, our design enables energy-efficient switching between NF-SPP manipulation and FF-wavefront engineering without requiring continuous power input. Experimental validation demonstrates two devices: Device I dynamically transitions between NF SPP focusing and FF vortex beam generation, while Device II toggles NF anomalous SPP focusing and FF holographic imaging. The metasurface uniquely integrates simultaneous amplitude/phase control for SPPs and free-space waves, overcoming the single-channel limitations of prior works. With reversible switching cycles and nonvolatile state retention (>10 years), this platform bridges the gap between on-chip plasmonics and free-space terahertz technologies, offering transformative potential for applications in 6 G communication, encrypted data storage, and multifunctional metasensors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the contemporary era of rapid technological innovation and industrial transformation, the development of the 6 G communication system faces unprecedented challenges. Terahertz waves, emerging as key enablers for 6 G networks, offer immense potential for creating more efficient and adaptable network architectures1. As a crucial information carrier in 6 G systems, terahertz waves can propagate through free space as propagating waves (PWs) or be confined to medium/metal interfaces as surface plasmons polaritons (SPPs), corresponding to far-field (FF) and near-field (NF) channels, respectively. Far-field regulation of terahertz waves supports applications such as remote sensing2, communication3, and imaging4, while near-field manipulation is vital for terahertz photonics-on-chip technologies5, essential for high-speed on-chip information processing6, photonic integrated circuits7, and on-chip communication8. However, conventional optical devices made from natural materials often suffer from bulkiness and limited functionality, making them inadequate for the demands of the terahertz band.

Metasurface, as two-dimensional metamaterials composed of a series of functional-driven artificial atoms, have attracted significant attention due to their sub-wavelength thickness and unprecedented ability to manipulate the amplitude, phase, and polarization of electromagnetic waves. Currently, numerous terahertz metasurface devices have been proposed for both far-field (e.g., chirality switching9, anomalous deflection10, and holographic plates11) and near-field applications (e.g., on-chip metalens12, logic operations13, and on-chip vortex interferometers14). While these devices have significantly advanced terahertz wave manipulation, they still exhibit notable limitations. First, most existing terahertz devices are static with fixed optical properties, restricting their adaptability. Therefore, it is highly desirable to develop reconfigurable metasurface devices to achieve active manipulation of terahertz waves. Recently, various active control methods have been proposed, including the use of VO215, liquid crystals16,17, graphene18,19, semiconductor material20,21, and MEMS22,23, whose optical properties can be changed through external stimuli such as light, electricity, and heat. These methods have led to various dynamic terahertz devices, such as spatial light modulators24, optical switches25, and dynamic holography26. However, most of these methods are volatile, requiring continuous energy input to maintain performance and thus causing the high consumption of energy, which is misaligned with carbon neutrality goals. Alternatively, the chalcogenide phase change material Ge2Sb2Te5 (GST) exhibits dramatic terahertz property contrast between its amorphous and crystalline phases due to entirely different bonding mechanisms27. As demonstrated before, the phase-transition process of GST can be achieved by multiple external stimuli (e.g., thermal annealing, optical pump, and electrical bias) with fast transition speed and long-term stability. Notably, GST’s phase states are non-volatile and can be maintained for over 10 years without energy consumption28,29. These characteristics make GST ideal for developing functional, integrated chip-level terahertz modulators. Second, most terahertz metasurface devices are designed to modulate either far-field30 or near-field12 channels individually. Although far-field and near-field multiplexing devices have been realized in the optical band31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39, most of these devices are static and cannot realize active control, moreover,the near-field manipulation in these works primarily focused on structural colors34,35,36,37 or polarization-dependent amplitude38,39, which are localized properties of the metasurface and can only be detected within the metasurface area. Consequently, these metasurface devices are primarily designed for display applications and unsuitable for on-chip communication. As a result, existing near- and far-field multiplexing strategies cannot be directly applied to the THz regime. Given the importance of both far-field and near-field channels in future terahertz communication systems, the above two limitations severely hinder the integration and miniaturization of systems. There is still a lack of dynamic reconfigurable Nonvolatile devices that integrate both far-field and near-field functions for versatile terahertz manipulation.

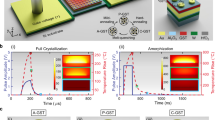

In this study, we propose a generic strategy for designing non-volatile reconfigurable far- and near-field multiplexed terahertz devices using GST-integrated metasurface and experimentally demonstrate that such devices can exhibit distinct functionalities in the NF and FF channels at terahertz region, achieving simultaneous amplitude/phase control for both SPPs. To further verify this strategy, we designed and fabricated two different dual-channel modulation devices. The first device achieves SPP focusing in the near field while generating a vortex beam in the far field. The second device enables anomalous SPP focusing and hologram formation in the near and far fields, respectively. The non-volatile and reversible reconfigurability of these two devices was both experimentally verified with high switching ratios through optical and thermal stimuli. This breakthrough bridges the gap between on-chip plasmonic signal processing and free-space terahertz wavefront engineering, addressing the longstanding challenge of integrating NF and FF functionalities in a single platform. Our work establishes a scalable paradigm for energy-efficient, multifunctional terahertz devices with transformative implications for 6 G communication systems, high-density data storage, and secure on-chip photonic networks (Fig. 1).

The central panel highlights the core design principle, with the left and right panels illustrating the schematic diagrams of devices I and II, respectively. These devices are devised to exhibit distinct functionalities under different states of phase change material GST. Specifically, in its amorphous phase, the devices are configured for NF functionality, while in its crystalline phase, they switch to FF operation

Results

Design strategy and characterizations of meta-atoms

According to the basic principles of metasurfaces, different functionalities require distinct complex amplitude distributions, which are determined by pre-designed near-field (NF) and far-field (FF) wave-controlled operations. To achieve this, we employed a block design principle, dividing the metasurface into passive and active regions. The passive region corresponds solely to the FF functionality, while the active region contributes to both NF and FF channels. The FF diffraction patterns of passive and active regions exhibit nearly identical amplitude with a π phase delay, causing destructive interference in the amorphous state of GST. There are two essential differences between these regions. First, GST is incorporated only into the active region to enable dynamic control. Second, the active region features a complex amplitude distribution that satisfies the two-dimensional Fresnel formula, contributing to the surface plasmons distribution within the NF channel, which is not needed in the passive region.

To achieve both NF and FF functions, we arranged the meta-atoms using the metasurface computational holography method. The design of the metasurface is based on the principle of optical path reversibility. In this approach, the false target image is composed of multiple point sources, and the amplitude and phase of their propagation to each point on the holographic plate are recorded by the corresponding metasurface meta-atoms. Thus, when light at the target frequency passes through the metasurface, the target image is reconstructed along the far optical path. The passive zone design adheres to this method. Similarly, in the active region, the holographic design of SPPs also follows the principle of optical path reversibility. The plasmon field at the target region is composed of many point sources, where the nth point source can be represented as \({S}_{{\rm{n}}}={A}_{{\rm{n}}}{e}^{i{{\varphi }}_{{\rm{n}}}}\), with \({A}_{{\rm{n}}}\) and \({{\varphi }}_{{\rm{n}}}\) represent its amplitude and phase, respectively. All SPPs emitted by these hypothetical sources interfere along the two-dimensional interface, forming the final image we need. Thus, the superimposed electric field at point m on the metasurface region, excited by all point sources, can be calculated as40:

where \(\mathop{{r}_{{\rm{nm}}}}\limits^{\rightharpoonup }\) is the vector pointing from the point source \({S}_{{\rm{n}}}\) to point m on the metasurface region, \({\lambda }_{{\rm{spp}}}\) and \({k}_{{\rm{spp}}}=2\pi /{\lambda }_{{\rm{spp}}}\) are the wavelength and the wave number of SPPs, respectively. Considering that holographic imaging is an inverse process, the sign on the natural exponent here is negative. Then, the metasurface complex amplitude distribution in active (U1) and passive (U2) regions can be obtained as follows:

where \({A}_{{\rm{FF}}}{e}^{i{{\varphi }}_{{\rm{FF}}}}\) is the complex amplitude distribution corresponding to the FF functionality, which can be obtained through some spatial reverse design algorithms. (Gerchberg–Saxton algorithms41, Fienup Fourier algorithm42, etc.) According to the formula, when GST is in the amorphous state, the active and passive regions work together, with a π phase difference between the second term of the active and passive regions, leading to destructive interference. As a result, the effective light intensity distribution in the FF channel approaches zero, and only the NF region can maintain an effective light intensity distribution. At this point, only the NF functionality is supported by the metasurface. When GST is in the crystalline state, the active region U1 is shut down, and the effective structure is U2. Although SPPs are generated in the excitation region (as shown in Fig. 4d), they do not satisfy the interference condition constrained by the two-dimensional Fresnel formula, hindering the formation of an effective SPP distribution in the NF functional region. Therefore, the metasurface can only support the functionality in the FF channel.

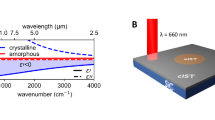

Here, we select a C-shaped slit resonator (CR) as the fundamental unit of the metasurface to simultaneously manipulate the phase and amplitude of terahertz waves in both NF and FF channels. The CR was selected for two main reasons. First, the SPP conversion efficiency of CR is relatively higher compared to other terahertz SPP excitation structures (see Supporting information, Figs. S2 and S3). Second, the CR allows simultaneous control of amplitude and phase by adjusting structural parameters in both the near-field43 and far-field44 channels. As shown in Fig. 2a, the CR consists of a complementary aluminum structure and a silicon substrate, where r denotes the radius, w is the slot width, Px and Py are the periods in the x and y directions, respectively, α is the opening angle, and θ is the rotation angle relative to the x-axis. The working principle of CR is based on the superposition of two orthogonal local surface plasmon resonances, allowing the resonators to be viewed as cross-polarized point sources. By adjusting the geometric parameters of CR, the amplitude and phase of cross-polarization can be simultaneously controlled. As shown in Fig. 2b, the amplitude and phase of cross-polarized terahertz waves transmitted through CRs with different geometric parameters were numerically simulated using computer simulation technology (CST) software. In the simulation, y-polarized terahertz waves are normally incident from the substrate side, with x-polarized output detected. The results confirm that arbitrarily desired amplitude and phase of cross-polarized waves can be achieved by selecting CR with optimal geometry.

a Schematic diagram of G-CR meta-atom, with r, w, α, θ representing outer radius, line width, orientation angle, and opening angle of CR structure, respectively. b Simulated amplitude and phase of cross-polarized terahertz waves transmitted through CRs with Px = Py = 80 μm, r ranging from 35 μm to 39.5 μm, w ranging from 5 μm to 8.5 μm, α ranging from 5° to 120°, θ ranging from −45° to 45°. The simulation was carried out at 0.7 THz. c Simulated cross-polarized terahertz transmission of G-CR structure with different GST conductivities: 0, 2000, 5000, 10,000, 1,00,000, 3,00,000 S/m. The geometrical parameters of CR are fixed at r = 37 μm, w = 8 μm, α = 70°, θ = 40°. d Measured terahertz transmission at 0.7 THz of reamorphized and the corresponding recrystallized GST layer at a 130 mJ/cm2 pump energy over 20 switching cycles

Next, a 200 nm-thick GST layer is inserted between the substrate and metallic layer of the CR structure, enabling the non-volatile tunability of terahertz wave transmission. Figure 2c illustrates the simulated cross-polarization transmission of a GST-integrated CR (G-CR) with varying GST conductivity. As conductivity increases from 0 S/m to 3,00,000 S/m, the transmission of cross-polarized terahertz waves, and thus the SPP conversion efficiency (See Supporting information, Fig. S4), decreases from maximum to nearly zero, confirming the feasibility of multi-level terahertz transmission modulation. The reconfigurability and cyclability of GST were further investigated. 200 nm-thick GST films were sputter-deposited from a Ge2Sb2Te5 stoichiometric target onto a 500 μm-thick high-resistivity silicon substrate and characterized using a homemade terahertz time-domain spectroscopy system. During measurement, the crystallization of GST was achieved by annealing the sample at 300 °C on a hot plate for 2 min. The reamorphization of GST was realized under the optical pump of a 10 ns laser pulse with 1064 nm wavelength and 130 mJ/cm2 energy. As illustrated in Fig. 2d, nearly consistent terahertz transmission for both amorphous and crystalline GST is observed over 20 switching cycles, indicating good reconfigurability and cyclability of our GST material. (See more characterization of GST for Supporting information, Figs. S5 and S6)

Non-volatile reconfigurable dual-channel terahertz modulator device I: NF SPP focusing and FF vortex beam generation

To validate the feasibility of the proposed method, we designed and implemented a non-volatile reconfigurable dual-channel terahertz modulation device operating at 0.7 THz. As illustrated in Fig. 3a, b, the device can generate SPP focusing and spatial vortex beam when the GST is in its amorphous and crystalline states, respectively. Based on the desired NF and FF functionalities, the metasurface should exhibit the following complex amplitude distributions:

Here, U1 and U2 represent the complex amplitude distribution of the electromagnetic field in the active and passive regions, respectively. \({A}_{1}\) and\({\theta }_{1}\) denote the amplitude and phase of the FF focal point. \(\mathop{|{r}_{nm}|}\limits^{\rightharpoonup }\) represents the distance from the NF focal point to the center of the mth meta-atom and \(k={k}_{{\rm{spp}}}=2\pi /{\lambda }_{{\rm{spp}}}\) is the wavenumber of SPP. fFF and l = 2 denote the focal length and topological charge of the vortex beam in the FF channel, respectively. Next, the device’s response under different states of GST was numerically simulated. When the GST is in the amorphous state, both the active and passive regions contribute to the target area, forming a SPP focus point in the NF channel (Fig. 3c) while canceling each other in the FF channel. In contrast, when the GST is in the crystalline state, the active region is shut down, leaving only the passive region operational, which generates a focused vortex beam with a topological charge of 2 in the FF channel, as illustrated in Fig. 3d, e. These simulation results confirm the performance of device I, validating the feasibility of the proposed design strategy.

The proposed device I is expected to a focus SPP in the NF channel and b focus the vortex beam with the topological charge of 2 in the FF channel under amorphous and crystalline GST, respectively. c Simulated terahertz intensity distribution in the NF channel under amorphous GST. Simulated d intensity and e corresponding phase distribution in the focus plane of the FF channel under crystalline GST. f Optical microscope image of part of the fabricated device I

Meta-device I (shown in Fig. 3f) was fabricated using conventional multistep lithography (see the Experimental Methods section for detailed procedures) and characterized using a self-built fiber-based near-field scanning terahertz microscopy (NSTM) system to validate our design. In the experiment, y-polarized terahertz waves were normally incident from the substrate side onto the sample as the excitation source. To systematically investigate the effects of sample modulation on terahertz waves, with an emphasis on distinguishing between spatial light and SPP behavior, distinct detection setups were used. For SPP detection, the photoconductive probe, sensitive to z-polarized terahertz waves, was positioned 75 μm above the sample and mounted on an electric translation stage to facilitate scanning in the x–y plane. The scanning area was 15.6 mm × 6 mm with a step size of 0.2 mm. In contrast, for detecting propagating waves in the FF channel, the probe was configured to detect x-polarized terahertz waves and placed 6 mm above the sample, with scanning conducted over a 6 mm × 6 mm area with a 0.2 mm step size.

As shown in Fig. 4, the experimental results present the normalized intensity distributions of metasurface device I in both the NF and FF channels with GST in amorphous and crystalline states, respectively. Figure 4a demonstrates that when the GST is in the amorphous state, SPPs excited on the CRs array of the metasurface propagate to the right and subsequently converge at the focal point, aligning perfectly with the design. As a terahertz SPP metalens, this device exhibits a focal depth of 2.4 mm along the propagation axis. The normalized intensity distribution along the focal plane (Fig. 4c) reveals a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 0.59 mm, comparable to the effective wavelength of the SPP. An effective numerical aperture (NA) of 0.46 was further calculated using the formulate \({\rm{NA}}={\lambda }_{{\rm{spp}}}/\pi w\) 45, where w is half of the FWHM. This NA could be further improved by increasing the area of the designed metalens. In contrast, as illustrated in Fig. 4b, the FF channel results reveal an average random electric field distribution at the target plane, indicating the absence of vortex beam generation. Then, the transition of GST from amorphous to crystalline state was achieved by annealing at 300 °C on a hot plate for 2 min. At this point, a doughnut-shaped intensity distribution and corresponding phase profile on the x–y focal plane of the FF channel are shown in Fig. 4e, f, respectively, clearly indicating the generation of a focused vortex beam with a topological charge of 2. However, no significant focusing characteristics were observed in the NF channel, as depicted in Fig. 4d. It is worth noting that the residual electric field distributions in the structural region (see Fig. 4d) are primarily induced by the passive area of the device. Specifically, in the crystalline state of GST, only the active region becomes inactive, while the passive region remains functional. Consequently, the electric field distribution generated by the passive CRs can still be observed within the structural region. However, this complex amplitude distribution does not conform to the two-dimensional Fresnel diffraction formula. As a result, the SPPs are confined to the excited region and are absent from the functional region, ensuring that they do not affect the device’s performance, as shown in Fig. 4d. These results confirm that functionality switching between NF and FF channels in device I can be achieved by inducing the crystallization of GST.

Normalized terahertz intensity distribution on the a x–y plane 75 μm above the sample and b FF focal plane under the amorphous GST. c Extracted normalized intensity profiles along the white dash lines in (a) and (d). Normalized terahertz intensity distribution on the d x–y plane 75 μm above the sample and e FF focal plane under the crystalline GST, with the corresponding phase profile depicted in (f). g–l Same characterization results with a–f under the reamorphized GST and recrystallized GST, respectively

To further validate the reconfigurability of device I, reamorphization and subsequent recrystallization processes of GST were induced by applying a single 130 mJ/cm2 laser pulse with 1064 nm wavelength, 10 ns pulse width, and 1 cm spot diameter and heating the sample at 300 °C for 2 min, respectively. The same characterizations were then performed for both NF and FF channels. By comparing Fig. 4g–l with Fig. 4a–f, it is observed that the responses of device I remain stable under the same state of GST across different switching cycles, thereby fully demonstrating the device’s reconfigurable modulation capability. To further quantify the modulation effect, we calculated the extinction ratio (ER) of the device under different operational states using the formula: ER(dB) = 10 log(Ion/Ioff), where Ion and Ioff represent the intensity at the target plane when the function is activated and deactivated, respectively. The extinction ratio for the FF and NF functions reached 19.86 dB and 18.96 dB, respectively, indicating the ideal switching characteristics of device I. In addition to reconfigurability, the switching of device I also exhibits non-volatility, meaning that its current functionality remains unchanged when external stimuli are removed. Thus, the proposed terahertz FF and NF modulation device is both energy-efficient and reconfigurable, with potential applications in terahertz on-chip integrated circuits, spatial communication, data storage, and computing.

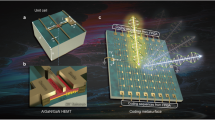

Non-volatile reconfigurable dual-channel terahertz modulator device II: NF SPP anomalous focusing and FF hologram

The proposed scheme is not limited to realizing devices with specific functionalities but is generic enough to design devices exhibiting distinct functionalities in NF and FF channels. As an explicit illustration, we further developed a novel terahertz modulation device capable of generating SPP anomalous focusing in the NF channel or a hologram in the FF channel, depending on the amorphous or crystalline state of GST, as illustrated in Fig. 5a, b. According to the desired NF and FF functionalities, the metasurface is expected to exhibit the following complex amplitude distributions:

Here, U1 and U2 denote the complex amplitude distributions of the terahertz field in the active and passive regions, respectively. While \({A}_{\rm{FF}}\) and \({\phi }_{\rm{FF}}\) are the amplitude and phase derived from the improved Gerchberg–Saxton algorithm based on the target FF hologram (See Supporting information, Fig. S7)). \(\mathop{|{r}_{nm}|}\limits^{\rightharpoonup }\) is the distance from the NF anomalous focal point to the center of the mth meta-atom. By selecting the required meta-atoms from our established database, device II can be realized. As shown in Fig. 5c, when device II is in the amorphous state of GST, both the active and passive regions contribute to the target area, resulting in SPP anomalous focusing in the NF channel and destructive interference in the FF channel. When GST transitions to its crystalline state, only the passive region is active, forming a holographic pattern in the FF channel, as illustrated in Fig. 5d, e.

The proposed device II is expected to a realize anomalous SPP focusing in the NF channel and b generate hologram in the FF channel under amorphous and crystalline GST, respectively. c Simulated terahertz intensity distribution in the NF channel under amorphous GST. Simulated d intensity and e corresponding phase distribution in the hologram imaging plane of FF channel under crystalline GST. f Optical microscope image of part of the fabricated device II

Device II (shown in Fig. 5f) was then fabricated and characterized using an NSTM system with y-polarized terahertz wave incidence. As illustrated in Fig. 6a–c, when GST is in its amorphous state, the NF channel is active, with excited SPPs exhibiting abnormal deflection and focusing 7 mm away from the edge of the sample region. Calculations indicate that the FWHM of the focal point is about 0.48 mm, corresponding to an NA value of 0.55. In contrast, the FF channel is inactive, with only an irregular light spot that can be detected on the holographic imaging plane, as shown in Fig. 6b. When GST is crystallized by annealing at 300 °C for 2 min, the SPPs focusing functionality in the NF channel is turned off, as illustrated in Fig. 6d. Meanwhile, a well-recognized letter “T” is observed on the holographic imaging plane of the FF channel, as depicted in Fig. 6e, f. These results are consistent with our theoretical predictions. Additionally, the responses of device II under reamorphized and subsequent recrystallized GST were also experimentally characterized, as shown in Fig. 6g–i, j–l, respectively. The stability of device II’s responses under the same state of GST across different switching cycles confirms the good reconfigurability of such the device. These findings demonstrate that the proposed strategy is generic and capable of designing non-volatile reconfigurable terahertz devices with distinct functionalities in NF and FF channels.

Normalized terahertz intensity distribution on the a x–y plane 75 μm above the sample and b FF hologram imaging plane under the amorphous GST. c Extracted normalized intensity profiles along the white dash lines in (a) and (d). Normalized terahertz intensity distribution on the d x–y plane 75 μm above the sample and (e) FF hologram imaging plane under the crystalline GST, with the corresponding phase profile depicted in (f). g–l Same characterization results with a–f, respectively, for reamorphized and recrystallized GST

Discussion

In summary, we propose a versatile strategy for designing reconfigurable dual-channel devices capable of manipulating terahertz waves in both spatial propagating and SPP modes, utilizing GST-integrated metasurface. Based on this strategy, two reconfigurable meta-devices were designed, fabricated, and experimentally characterized. The non-volatile switching between near-field (SPP focusing/anomalous focusing) and far-field (vortex beams/holograms) functionalities, as experimentally validated in Devices I and II, enables transformative applications in 6 G communication systems (on-chip SPP routing and free-space beam steering), encrypted data storage (dual-channel information splitting with >10-year state retention), and multifunctional metasensors (simultaneous local/remote sensing). Compared to prior reconfigurable terahertz devices, our platform uniquely integrates dual-mode control with zero static power consumption, addressing critical limitations in energy efficiency and functional integration. This work paves the way for advanced terahertz technologies in communication, sensing, and security domains.

Notably, compared to near- and far-field multiplexing metasurfaces proposed in the optical band33,34,35,36,37,38,39, our work demonstrates fundamental differences in manipulation targets, manipulation degrees of freedom (DoFs), and thus application scenarios. First, previous studies primarily focused on structural colors34,35 or polarization-dependent amplitude38,39 as manipulation targets in the near-field channel, which are localized properties confined to the metasurface area. In contrast, our works focused on SPP modes in the near-field channel, which can propagate along the device interface and can be detected far from the metasurface area5. Second, in earlier works, near-field manipulation was limited to amplitude control based on structural color theory34,35 or Malus’s law38,39. In contrast, our devices enable simultaneous manipulation of both the amplitude and phase of SPP modes in the near-field channel, introducing additional manipulation DoFs. These advancements make proposed metasurfaces hold significant potential for applications such as integrated terahertz communication systems, advanced terahertz metasensors, and information encryption.

Moreover, compared to previous works on reconfigurable terahertz devices12,30,46, our proposed strategy offers two significant advantages. First, the designed devices can simultaneously modulate terahertz waves in two distinct modes, i.e. spatial propagating mode and SPP mode, which are both crucial for potential terahertz applications. Second, leveraging the non-volatile and stable properties of GST, the operational states of these devices can be maintained without any energy consumption, which is highly desirable, considering the issue of energy shortages. Therefore, our work has introduced a novel approach for simultaneous control of propagating waves and SPPs in the terahertz frequency range, paving the way to develop energy-efficient reconfigurable terahertz devices for potential applications. First, the proposed terahertz devices can support both intrachip high-speed data transmission and long-distance information transmission within future communication systems using a single device, thus enabling multifunctionality and miniaturization. Moreover, these metasurface devices can store distinct information in two independent channels with nonvolatile tunability, providing a promising platform for achieving terahertz information encryption. Notably, unlike in the optical band, where near-field storage usually comprises pure-amplitude nanoprinting images34,35, the near-field channel in our devices can store information in complex-amplitude form. Finally, given that our proposed metasurfaces are capable of simultaneously manipulating the terahertz complex amplitudes in two distinct channels, these metasurfaces can serve as integrated, multifunctional platforms for advanced near- and far-field multiplexed terahertz metasensors.

It is worth noting that several studies have demonstrated electrically controlled GST devices in the optical regime47,48,49, demonstrating the theoretical feasibility of electrically reconfigurable terahertz devices based on GST. However, there remain significant technical challenges. First, due to the larger area of terahertz devices, the total energy required for the phase transition process of GST in these devices is relatively high, placing greater demands on the output power and bandwidth of voltage source equipment. Second, as demonstrated in previous works50,51, the phase transition temperatures of GST increase with higher heating rates. As a result, the face-centered cubic (FCC) to hexagonal close-packed (HCP) phase transition process in GST, which is highly desirable for THz modulation, may disappear under ultrafast heating rates. This constraint significantly limits the modulation speed of terahertz devices based on GST. Nevertheless, we believe that these limitations can be addressed by improving the design of GST devices and optimizing GST properties via doping52, controlling the growth environment53, adjusting the Ge, Sb, and Te atomic ratios54, or other innovative approaches.

Methods

Numerical simulation

The numerical simulations of meta-atoms were performed using CST Microwave Studio. In the simulations, aluminum (Al) was modeled as a lossy metal with a conductivity of σAl = 3.56 × 107 S/m, and the silicon substrate was treated as a lossless dielectric with a permittivity of εSi = 11.9. The conductivity of the GST layer in its amorphous and crystalline states was set to be 500 S/m and 3 × 105 S/m, respectively, extracted from measured terahertz transmission results using a time-domain spectroscopy (THz-TDS) system. The NF channel signal was defined as the intensity of z-polarized terahertz waves 75 μm above the sample, while the FF channel signal was defined as the intensity of x-polarized terahertz waves 6 mm above the sample.

Experimental characterization

The performance of the metasurface devices was experimentally characterized using an all-fiber NSTM system, which can directly detect the propagating waves and SPPs above the sample surface. This system utilizes a photoconductive antenna to generate a broadband terahertz free-space beam, which is collimated by a terahertz lens and then incident vertically from the bottom of the substrate to excite the electromagnetic field on the metasurface device. SPPs were probed approximately 75 μm above the sample surface using a terahertz near-field probe that is sensitive only to the z-polarized electric field component. In contrast, propagating waves were probed approximately 6 mm above the sample surface using another terahertz near-field probe, which responds exclusively to the x-polarized electric field component.

References

Akyildiz, I. F., Han, C., Hu, Z., Nie, S. & Jornet, J. M. Terahertz band communication: an old problem revisited and research directions for the next decade. IEEE Trans. Commun. 70, 4250–4285 (2022).

Zhao, M. et al. Applications of satellite remote sensing of nighttime light observations: advances, challenges, and perspectives. Remote Sens. 11, 35 (2019).

Jornet, J. M., Knightly, E. W. & Mittleman, D. M. Wireless communications sensing and security above 100 GHz. Nat. Commun. 14, 841 (2023).

Li, W. et al. Dual-color terahertz spatial light modulator for single-pixel imaging. Light 11, 191 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Terahertz surface plasmonic waves: a review. Adv. Photonics 2, 014001 (2020).

Jiang, X. et al. On-chip terahertz orbital angular momentum demultiplexer. Photonics Res. 12, 1044 (2024).

Ren, H. et al. Terahertz flexible multiplexing chip enabled by synthetic topological phase transitions. Natl Sci. Rev. 11, nwae116 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Terahertz topological photonics for on-chip communication. Nat. Photonics 14, 446–451 (2020).

Bao, J. et al. Nonvolatile chirality switching in terahertz chalcogenide metasurfaces. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 8 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Broadband terahertz wave deflection based on C-shape complex metamaterials with phase discontinuities. Adv. Mater. 25, 4567–4572 (2013).

Wang, Q. et al. Reflective chiral meta-holography: multiplexing holograms for circularly polarized waves. Light 7, 25 (2018).

Zhang, S. et al. On‐chip non‐volatile reconfigurable THz varifocal metalens. Laser Photonics Rev. 17, 202300482 (2023).

Yuan, M. et al. Terahertz spoof surface plasmonic logic Gates. iScience 23, 101685 (2020).

Lang, Y. et al. On‐chip plasmonic vortex interferometers. Laser Photonics Rev. 16, 2200242 (2022).

Liu, M. et al. Switchable chiral mirrors. Adv. Opt. Mater. 8, 1154 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. Broadband tunable liquid crystal terahertz waveplates driven with porous graphene electrodes. Light 4, 6 (2015).

Shrekenhamer, D., Chen, W. C. & Padilla, W. J. Liquid crystal tunable metamaterial absorber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 5 (2013).

Lee, S. H. et al. Switching terahertz waves with gate-controlled active graphene metamaterials. Nat. Mater. 11, 936–941 (2012).

Li, Q. et al. Active graphene-silicon hybrid diode for terahertz waves. Nat. Commun. 6, 6 (2015).

Hu, Y. et al. Pump-color selective control of ultrafast all-optical switching dynamics in metaphotonic devices. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.) 7, 2000799 (2020).

Hu, Y. et al. Ultrafast terahertz transmission/group delay switching in photoactive WSe2-functionalized metaphotonic devices. Nano Energy 68, 104280 (2020).

Cong, L. Q., Pitchappa, P., Lee, C. & Singh, R. Active phase transition via loss engineering in a terahertz MEMS metamaterial. Adv. Mater. 29, 7 (2017).

Pitchappa, P. et al. Active control of electromagnetically induced transparency analog in terahertz MEMS metamaterial. Adv. Opt. Mater. 4, 541–547 (2016).

Zeng, H. et al. Ultrafast modulable 2DEG Huygens metasurface. Photonics Res. 12, 1004 (2024).

Hu, Y. Z., Tong, M. Y., Xu, Z. J., Cheng, X. G. & Jiang, T. Bifunctional spatiotemporal metasurfaces for incident angle-tunable and ultrafast optically switchable electromagnetically induced transparency. Small 17, 10 (2021).

Liu, X. B. et al. Thermally dependent dynamic meta-holography using a vanadium dioxide integrated metasurface. Adv. Opt. Mater. 7, 7 (2019).

Chen, X. et al. Reconfigurable and nonvolatile terahertz metadevices based on a phase-change material. ACS Photonics 9, 1638–1646 (2022).

Kolobov, A. V. et al. Understanding the phase-change mechanism of rewritable optical media. Nat. Mater. 3, 703–708 (2004).

Zhang, S. et al. Terahertz multi-level nonvolatile optically rewritable encryption memory based on chalcogenide phase-change materials. iScience 25, 104866 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. Nonvolatile reconfigurable terahertz wave modulator. PhotoniX 3, 7 (2022).

Dai, C., Liu, T., Wang, D. & Zhou, L. J. P. Multiplexing near-and far-field functionalities with high-efficiency bi-channel metasurfaces. PhotoniX 5, 11 (2024).

Jiang, Q. et al. Bi-channel near-and far-field optical vortex generator based on a single plasmonic metasurface. Photonics Res. 8, 986–994 (2020).

Fu, R., Chen, K., Li, Z., Yu, S. & Zheng, G. Metasurface-based nanoprinting: principle, design and advances. Opto-Electron. Sci. 1, 220011 (2022).

Yoon, G., Lee, D., Nam, K. T. & Rho, J. “Crypto-Display” in dual-mode metasurfaces by simultaneous control of phase and spectral responses. Acs Nano 12, 6421–6428 (2018).

Wei, Q. et al. Simultaneous spectral and spatial modulation for color printing and holography using all-dielectric metasurfaces. Nano Lett. 19, 8964–8971 (2019).

Yang, W. et al. Dynamic bifunctional metasurfaces for holography and color display. Adv. Mater. 33, 2101258 (2021).

Wan, C. et al. Electric-driven meta-optic dynamics for simultaneous near-/far-field multiplexing display. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2110592 (2022).

Deng, L. et al. Malus-metasurface-assisted polarization multiplexing. Light 9, 101 (2020).

Ren, R. et al. Non-orthogonal polarization multiplexed metasurfaces for tri-channel polychromatic image displays and information encryption. Nanophotonics 10, 2903–2914 (2021).

Teperik, T. V., Archambault, A., Marquier, F. & Greffet, J. J. Huygens-Fresnel principle for surface plasmons. Opt. Express 17, 17483–17490 (2009).

Gerchberg, R. A practical algorithm for the determination of phase from image and diffraction plane pictures. optik 35, 237–246 (1972).

Dorsch, R. G., Lohmann, A. W. & Sinzinger, S. Fresnel ping-pong algorithm for two-plane computer-generated hologram display. Appl. Opt. 33, 869–875 (1994).

Xu, Q. et al. Efficient metacoupler for complex surface plasmon launching. Adv. Opt. Mater. 6, 201701117 (2018).

Liu, L. et al. Broadband metasurfaces with simultaneous control of phase and amplitude. Adv. Mater. 26, 5031–5036 (2014).

Wintz, D., Genevet, P., Ambrosio, A., Woolf, A. & Capasso, F. Holographic metalens for switchable focusing of surface plasmons. Nano Lett. 15, 3585–3589 (2015).

Zhang, S. et al. Nonvolatile reconfigurable dynamic Janus metasurfaces in the terahertz regime. Photonics Res 10, 1731 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. Electrically reconfigurable non-volatile metasurface using low-loss optical phase-change material. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 661 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Electrical tuning of phase-change antennas and metasurfaces. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 667 (2021).

Abdollahramezani, S. et al. Electrically driven reprogrammable phase-change metasurface reaching 80% efficiency. Nat. Commun. 13, 1696 (2022).

Orava, J., Greer, A. L., Gholipour, B., Hewak, D. W. & Smith, C. E. Characterization of supercooled liquid Ge2Sb2Te5 and its crystallization by ultrafast-heating calorimetry. Nat. Mater. 11, 279–283 (2012).

Lu, H. et al. Single pulse laser-induced phase transitions of PLD-deposited Ge2Sb2Te5 films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 3621–3627 (2013).

Wang, K. et al. Influence of doping upon the phase change characteristics of Ge2Sb2Te5. Microsyst. Technol. 13, 203–206 (2007).

Dieker, H. & Wuttig, M. Influence of deposition parameters on the properties of sputtered Ge2Sb2Te5 films. Thin Solid Films 478, 248–251 (2005).

Guerin, S., Hayden, B., Hewak, D. W. & Vian, C. Synthesis and screening of phase change chalcogenide thin film materials for data storage. ACS Comb. Sci. 19, 478–491 (2017).

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 62235013, 62335012, 62405215); China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2024M752359); Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (Grant No. GZC20241200).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, Y., Chen, X., Zhang, S. et al. Dynamic dual-mode terahertz device with nonvolatile switching for integrated on-chip and free-space applications. Microsyst Nanoeng 11, 169 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01020-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01020-3