Abstract

The controllable modulation of carrier polarity in semiconductors is essential for enabling dynamic configurations in reconfigurable devices. Ambipolar two-dimensional (2D) semiconductors, characterized by their atomic-scale thickness and excellent gate modulation efficiency, have emerged as highly promising channel materials for such devices. However, existing methods for polarity control encounter challenges in achieving reversible modulation during device operation. Here, we report a novel strategy for reversibly modulating the polarity of ambipolar 2D semiconductors through gate-controlled charge trapping. We demonstrate a double-gate TaOx/WSe2/h-BN field-effect transistor, which can reversibly switch between n-type and p-type transport characteristics via electric-field-driven bipolar charge trapping at the TaOx/WSe2 interface. With this method, an electrically configurable complementary inverter is created with a single WSe2 flake, exhibiting a power consumption of just 0.7 nW. Additionally, a programmable p-n/n-p diode is realized with a > 100,000-fold change in the rectification ratio. These results demonstrate the great potential of gate-controlled bipolar charge trapping for advancing reconfigurable electronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reconfigurable electronic devices offer the technology with run-time reconfigurability at the device level, allowing electronic circuits to be programmed according to specific requirements and diverse functionalities1,2. Recent developments in such devices, including field-effect transistors (FETs)3,4, gate-tunable p-n junctions5, and photodetectors6, have exhibited great potential to enhance circuit functions. Semiconductor polarity control serves as a pivotal technology for advancing these devices7, where reversible polarity modulation enables the dynamic reconfiguration of circuit logic functions and operational modes2. Ambipolar two-dimensional (2D) semiconductors, such as molybdenum ditelluride (MoTe2)8,9, tungsten diselenide (WSe2)10,11, and black phosphorus (BP)12,13, are particularly well-suited for such applications due to their exceptional gate-controlled capability to rapidly and reversibly switch carriers between holes and electrons14.

To date, polarity control in ambipolar 2D semiconductors has primarily relied on two distinct strategies. The first strategy involves extrinsic doping techniques—including substitutional doping15,16, chemical intercalation17, and surface charge transfer18,19—which modulate semiconductor polarity through charge transfer between the dopants and the semiconductor material. However, these methods preclude reversible dynamic modulation after fabrication20. In contrast, the second strategy utilizes electric field gating9,21,22 to achieve dopant-free reversible polarity control. This approach, however, requires a continuous power input to maintain field effects during operation, leading to ongoing power consumption that hinders the practical implementation of reconfigurable multifunctional devices23.

Beyond the aforementioned polarity modulation approaches, recent studies have demonstrated defect engineering strategies for developing reconfigurable electronic devices. Two primary methodologies have emerged: gate-stack-integrated interfacial layers and environmentally responsive approaches. The former utilizes materials such as PbI224, AlOx25, and Bi4Ti3O1226 in gate stacks, where an electric field-modulated charge trapping/detrapping mechanism at the channel-defect layer interface enables the reconfigurability of the devices. The latter employs either gas-phase exposure, leveraging defect-mediated O2 adsorption and desorption on channel surfaces for reversible polarity switching, or photon-assisted interfacial charge trapping to achieve non-volatile device operation27,28,29. Crucially, the intrinsic material defects in crystalline structures and the controllable introduction of defects through processing demonstrate that defect engineering is a critical strategy for advancing reconfigurable electronics. The synergistic combination of inevitable crystalline imperfections and tunable defect engineering provides essential guidelines for semiconductor polarity control in reconfigurable electronic devices.

In this work, we demonstrate dynamically controllable polarity modulation of the double-gate TaOx/WSe2/h-BN FETs through the gate-controlled bipolar charge trapping at the TaOx/WSe2 interface. By manipulating the polarity of the gate voltage, electrons or holes in the WSe2 channel can be selectively captured, resulting in electrostatic doping and polarity modulation of the channel. Using this method, we successfully constructed an electrically configurable complementary inverter within the same WSe2 flake, representing a power consumption of only 0.7 nW. Additionally, programmable diodes were fabricated based on this strategy, exhibiting reversible transitions between p-n and n-p configurations with a rectification ratio change of over 105.

Results and discussion

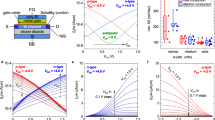

The schematic structure of a double-gate TaOx/WSe2/h-BN FET is shown in Fig. 1a, consisting of a few-layer WSe2 as the channel material, TaOx as the interface layer, h-BN flake as the gate dielectric and Cr/Au as the gate electrodes and source/drain contacts (the detailed fabrication process is illustrated in Fig. S1). The TaOx layer was obtained by oxidizing TaS2 through UV exposure followed by a subsequent heating treatment (see Methods section). The UV treatment enables the rapid formation of oxide layers with nanometer-scale interface uniformity30. It can be observed from atomic force microscopy (AFM) characterizations that the surface roughness of the sample increases slightly with increasing duration of UV exposure while remaining at the nanometer level (Fig. S2a, b), demonstrating interface uniformity. At the same time, the analysis of sample thickness with different oxidation durations indicates that oxidation reached self-limitation after 25–30 min of UV treatment (Fig. S2c). Thus, the subsequent thermal oxidation process effectively circumvents the intrinsic self-limiting oxidation kinetics of TaS2, facilitating the complete conversion to amorphous TaOx while preserving its structural integrity31. Furthermore, this approach simultaneously induces surface reconstruction to reduce roughness (Fig. S2d) and promotes defect formation through high thermal energy input32.

a 3D schematic of the FET, where D, S, TG, and PG represent the drain, source, top gate, and programming gate electrodes, respectively. b Raman spectra of individual WSe2, TaOx, and their heterostructure region. The inset shows the Raman measurement regions, with blue, green, and red spots corresponding to the TaOx, WSe2, and WSe2/TaOx stacking regions, respectively. c Transfer characteristic at an applied bias voltage of 0.5 V, with arrows indicating the direction of the top gate voltage sweep. d Output characteristics under Vtg ranging from -12 V to 12 V with a step of 4 V

The optical differences between TaOx and TaS2 are given in Fig. S3a, b. Due to the larger band gap, TaOx exhibits greater transparency than TaS233,34. The Raman spectra depicted in Fig. S3c provide additional evidence for the oxidation of TaS2 into TaOx, as demonstrated by the observed shifts in the characteristic peaks35,36. Given that a volume decrease of approximately 25% would be expected if the TaS2 was transformed into crystalline TaOx, the observed thickness reduction of only ~2% (Fig. S3d-f) with unchanged lateral dimensions suggests that the TaOx is a likely amorphous structure, exhibiting a significantly lower density compared to crystalline TaOx37,38. It is this lower-density non-crystalline structure that enables atmospheric oxygen to penetrate deeply into the material, facilitating uniform and complete thermal oxidation throughout the sample. Raman characterization is also employed to identify the WSe2, TaOx, and heterostructure region (Fig. 1b). For TaOx, the Raman peaks observed at 302 cm−1 and 435 cm−1 correspond to the 2TA and TA + LA modes, respectively, which arise from two-phonon scattering processes35. The Raman spectra of WSe2 exhibit three distinct peaks at 137 cm−1, 248 cm−1, and 251 cm-1, corresponding to the E1g, E12g, and A1g vibrational modes of the WSe2 flakes39,40. Notably, the Raman spectrum of the WSe2/TaOx heterostructure region contains all the characteristic peaks of both materials, confirming the successful stacking of the TaOx and WSe2 flakes.

Figure 1c, d show the electrical performance of this double-gate FET. The transfer characteristic in Fig. 1c shows a typical ambipolar behavior with an on/off ratio of approximately 105 for n-type transport and over 102 for p-type transport, indicating that n-type behavior dominates in the WSe2 FET. The observed hysteresis between the forward and backward sweeps can mainly be attributed to charge trapping effects at the interface of TaOx/WSe2 or WSe2/h-BN41,42. The output characteristics in Fig. 1d show a significant increase in current as the gate voltage rises, demonstrating the effective modulation of the double-gate FET by the gate electric field.

To investigate the hysteresis mechanism observed in the double-gate FET, we first compared the hysteresis width (∆V) of FETs with and without the stacked TaOx layer. The ∆V is extracted by calculating the voltage difference between forward and backward sweeps at a current level of 10-3 nA for the electron transport branch. As shown in Fig. S4, the transfer characteristics of the WSe2 FET with TaOx stacking exhibit more significant hysteresis, indicating that the hysteresis behavior is related to the TaOx layer. Then, a comparison of the ∆V in double-gate FETs based on TaOx prepared by different UV exposure durations (all followed by 300 °C/3 h thermal treatment) reveals a larger hysteresis in the 1.5 h device (7.90 V) versus the 5 min (1.68 V) and 30 min (6.72 V) devices (Fig. S5), once again proving that the hysteresis behavior of the device originates from the TaOx layer. Therefore, we ascribe the hysteresis in our devices to the presence of TaOx under the WSe2 channel.

Additionally, transfer characteristics under varying top-gate voltage (Vtg) sweep ranges and rates are obtained to further research this mechanism, as illustrated in Fig. 2a, b. It can be found that the ∆V enlarges with the increase of gate voltage sweeping range or with the decrease of sweeping rate, as shown in Fig. 2c, d, respectively, suggesting that the hysteresis observed in our devices originates from charge trapping under the gate electric stress42,43. In particular, as shown in Fig. 2e, when Vtg < 0, the electric field at the WSe2/TaOx interface is oriented downward, which promotes the migration of holes from the WSe2 channel to the TaOx surface. These holes are subsequently trapped by defects, creating a positive electrostatic field that shifts the threshold voltage negatively for the forward sweep. Conversely, when Vtg > 0, electrons are driven and captured, resulting in a negative electrostatic field that causes a positive shift of the threshold voltage for the backward sweep. This bipolar charge trapping behavior, driven by the top-gate electric field, thus generates a clockwise hysteresis for the electron transport branch and a counterclockwise hysteresis for the hole transport branch. As the gate voltage sweeping range increases or the sweeping rate decreases, a greater number of carriers will migrate to and get trapped at the WSe2/TaOx interface, thus leading to an enlarged hysteresis.

Transfer characteristics at different Vtg a sweeping ranges and b sweeping rates. Variation of hysteresis at different Vtg c sweeping ranges d sweeping rates. e Principal mechanism underlying the hysteresis behavior. The solid arrows in a and b indicate the direction of the top-gate voltage sweep. ∆V and the dashed line represent the size and the current level of the hysteresis window, respectively. The dashed arrows in e show the direction of the top gate electric field

Leveraging the established thickness dependence of WSe2 carrier polarity11, we explore the potential of this bipolar charge trapping in polarity modulation of double-gate FETs fabricated with p-type (~4 nm), ambipolar (~7 nm), and n-type (~10 nm) WSe2 flakes (Figure S6), respectively. To investigate dynamic modulation effects, voltage pulses with different polarities are applied to the PG electrode. As shown in Fig. 3a, the conductivity type of the WSe2 FET changes gradually from its initial n-type to a programmed p-type after being programmed by a positive voltage pulse (VPG > 0). And a negative voltage pulse (VPG < 0) can reverse this change. Conversely, the pristine p-type WSe2 FET undergoes a transition to a programmed n-type under a negative program voltage pulse, which can also be reversed by altering the pulse polarity, as shown in Fig. 3b. Furthermore, reversible changes between ambipolar and unipolar transport characteristics are also achieved in the WSe2 FETs through the gate-controlled bipolar charge trapping (Fig. 3c, d). The detailed processes corresponding to Fig. 3a–d are provided in Fig. S7. This polarity control exhibits a retention time exceeding 103 s (Fig. S8). Meanwhile, prolonged pulse durations consistently enhance the efficacy of WSe2 polarity modulation, indicating an effect similar to that observed when manipulating the amplitude of the pulse voltage (Fig. S9). These findings confirm the great advantage of gate-controlled bipolar charge trapping in realizing reversible polarity control for the ambipolar 2D semiconductor.

a Reversible polarity modulation between the pristine n-type and the programmed p-type. b Reversible polarity modulation between the pristine p-type and the programmed n-type. c-d Reversible polarity modulation between ambipolar and unbipolar. e Formation mechanism of the programmed p-/n-type under different voltage pulses. All measurements in a and b were conducted at Vds = 0.5 V. The positive and negative voltage pulses in a and b are (+2 V, -6 V) and (+7 V, -5 V), respectively. The voltage pulses in c and d are -7 V and +5 V, respectively. All voltage pulses are applied with a duration of 4 s

The detailed mechanism underlying the reversible polarity modulation of the double-gate TaOₓ/WSe2/h-BN FET is schematized in Fig. 3e. As discussed earlier regarding the hysteresis mechanism, when VPG > 0, electrons, which are driven and captured at the TaOₓ/WSe2 interface by the gate electric field, induce electrostatic doping to accumulate holes in the WSe2 channel, resulting in a programmed p-type polarity. Conversely, when VPG < 0, holes are trapped to induce electron accumulation and thus form a programmed n-type polarity. Therefore, the polarity of such a double-gate WSe2 FET can be reversibly modulated by gate-controlled bipolar charge trapping through altering the polarity of the PG voltage.

A complementary inverter was fabricated based on a single WSe2 flake to investigate the feasibility of this polarity regulation method for reconfigurable devices. As illustrated in Fig. 4a, the complementary inverter consists of two WSe2 transistors connected in series, with each transistor controlled by an independent PG (PG1 and PG2). Positive and negative voltage pulses are applied to PG1 and PG2, respectively, to establish a p-type and an n-type FET, as evidenced by their distinct transfer characteristics shown in Fig. 4b, c. Subsequently, the voltage transfer curves, plot of input (Vin) versus output voltage (Vout), of the complementary inverter under different supply voltages (Vdd) were measured, as shown in Fig. 4d. Signal inversions are observed with high Vout at negative Vin and low Vout at positive Vin, which further demonstrates that both p- and n-type FETs are successfully achieved through polarity modulation. Figure 4e presents the voltage gain of the programmable inverter, defined as |dVout/dVin | , with a maximum gain of 0.7. Notably, the complementary inverter exhibits a peak power consumption of 0.7 nW at Vdd = 2.0 V (Fig. 4f), indicating that gate-controlled charge trapping is an effective strategy for constructing low-power logic devices.

To further explore the potential of this strategy in reconfigurable electronic devices, we created a programmable diode using a single WSe2 flake. Figure 5a, b shows that the programmable diode has two PGs, PG1, and PG2, which are designed to simultaneously modulate the transport type of the WSe2 channel by programming with opposite voltage pulses. Figure 5c shows that the transfer behavior gradually changes from p-n type to n-p type after being programmed by negative and positive voltage pulses applied to the PG1 and PG2 electrodes, respectively. This transition can be accurately quantified by the change of the current rectification ratio |I+/I−|, where I+ and I− represent the current values at bias voltages of +2 V and -2 V, respectively. As shown in Fig. 5d, the rectification ratio of the diode changes from 6672 to 0.06, indicating a transition from a p-n diode to an n-p diode after programming. Notably, the formed n-p diode can be reversed into the p-n mode with an over 105-fold change in rectification ratio by exchanging the polarity of the voltage pulses applied to PG1 and PG2 electrodes, as shown in Fig. 5e. These results demonstrate reversible conversions between p-n and n-p configurations of the WSe2 channel and highlight the great potential of the gate-controlled charge trapping strategy in reconfigurable electronics.

a Optical image and b schematic diagram of the programmable diode. c I–V characteristics of the diode changing from a p-n to an n-p junction after applying negative and positive pulses to PG1 and PG2, respectively. d Current rectification ratio |I+/I-| for the diode shown in c. e I–V characteristics of the diode reversing from an n-p to a p-n junction after applying opposite pulses. f Current rectification ratio |I+/I-| for the diode shown in e. All voltage pulses are applied with a duration of 8 s

Conclusion

A strategy for reversible polarity modulation in ambipolar 2D FETs via the gate-controlled bipolar charge trapping mechanism is proposed. By inserting a TaOx layer into the gate stack of WSe2 FET, the conductive characteristics can be reversibly switched between n-type and p-type behavior by controlling the polarity of the PG voltage pulses. Based on this strategy, an electrically configurable complementary inverter with a power consumption of 0.7 nW and a programmable diode with a 100,000-fold change in rectification ratio were successfully fabricated using a single WSe2 flake, respectively. Our work demonstrates that gate-controlled bipolar charge trapping is a promising method for reconfigurable electronics.

Materials and methods

Fabrication of the double-gate TaOx/WSe2/h-BN FET

The WSe2, TaS2, and h-BN flakes were obtained by mechanical exfoliation from their bulk crystals. The thickness of p-type, ambipolar, and n-type WSe2 flakes are ~4 nm, ~7 nm, and ~10 nm, respectively. The TaS2 thickness was controlled in the range of 20–50 nm. The stacked TaS2 flake and WSe2/h-BN heterostructure were produced with a dry transfer technique, as reported. TaOx was obtained from TaS2 through 1.5 h of UV exposure and 3 hours of heating at 300 °C. All electrodes, including the PG (5 nm Cr/15 nm Au), the S/D (5 nm Cr/50 nm Au), and the TG (5 nm Cr/70 nm Au), were defined using the MicroWriter ML 3 Pro system (Durham Magneto Optics) followed by metal thermal evaporation and lift-off process. A detailed schematic of the fabrication process for the double-gate TaOx//WSe2/h-BN FET is provided in Fig. S1.

Characterization and measurement of the double-gate TaOx/WSe2/h-BN FET

Raman spectra were acquired using an Invia Qontor instrument (Renishaw) with a 532 nm laser of 5 W power under ambient conditions. The measure setting parameters of samples are shown as follows: 1. accumulations: 50; 2. acquire time: 5 s; 3. grating: 1800 (532 nm); 4. ND filter: 10%; 5. Objective: 50x_LWD. The sample thicknesses were measured by atomic force microscopy (AFM, Oxford Instruments MFP-3D AFM) using an Otespa-R3 probe in tapping mode, with optimized parameters: 1. scan rate: 1.0 Hz; 2. samples/line: 256; 3. integral gain: 0.5; 4. proportional gain: 5.0; 5. drive frequency: 300 kHz; 6. amplitude setpoint: 120 mV; 7. drive amplitude: 120 mV. All electrical measurements were conducted in a vacuum probe station using a Keithley 4200A-SCS system.

References

Zhang, H. T. et al. Reconfigurable perovskite nickelate electronics for artificial intelligence. Science 375, 533–539 (2022).

Fei, W., Trommer, J., Lemme, M. C., Mikolajick, T. & Heinzig, A. Emerging reconfigurable electronic devices based on two-dimensional materials: a review. InfoMat 4, e12355 (2022).

Zhao, Z., Kang, J., Rakheja, S. & Zhu, W. Control-gate-free reconfigurable transistor based on 2D MoTe2 with asymmetric gating. Appl. Phys. Lett. 124, 073506 (2024).

Tsai, M. Y. et al. A reconfigurable transistor and memory based on a two-dimensional heterostructure and photoinduced trapping. Nat. Electron. 6, 755–764 (2023).

Li, D., Wang, B., Chen, M., Zhou, J. & Zhang, Z. Gate-controlled BP-WSe2 heterojunction diode for logic rectifiers and logic optoelectronics. Small 13, 1603726 (2017).

Huang, J. et al. Reconfigurable WSe2 Schottky heterojunctions for logic rectifiers and ultrafast photodetectors. Sci. China Mater. 66, 4711–4722 (2023).

Peng, R. et al. Programmable graded doping for reconfigurable molybdenum ditelluride devices. Nat. Electron. 6, 852–861 (2023).

Sun, X. et al. Contact and injection engineering for low SS reconfigurable FETs and high gain complementary inverters. Sci. Bull. 65, 2007–2013 (2020).

Larentis, S. et al. Reconfigurable complementary monolayer MoTe2 field-effect transistors for integrated circuits. ACS Nano 11, 4832–4839 (2017).

Resta, G. V. et al. Doping-free complementary logic gates enabled by two-dimensional polarity-controllable transistors. ACS Nano 12, 7039–7047 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. Controllable doping in 2D layered materials. Adv. Mater. 33, 2104942 (2021).

Wu, P. et al. Complementary black phosphorus tunneling field-effect transistors. ACS Nano 13, 377–385 (2018).

Wu, P., Reis, D., Hu, X. S. & Appenzeller, J. Two-dimensional transistors with reconfigurable polarities for secure circuits. Nat. Electron. 4, 45–53 (2021).

Hu, W. et al. Ambipolar 2D semiconductors and emerging device applications. Small Methods 5, 2000837 (2021).

Nipane, A., Karmakar, D., Kaushik, N., Karande, S. & Lodha, S. Few-layer MoS2 p-type devices enabled by selective doping using low energy phosphorus implantation. ACS Nano 10, 2128–2137 (2016).

Dolui, K., Rungger, I., Das Pemmaraju, C. & Sanvito, S. Possible doping strategies for MoS2 monolayers: an ab initio study. Phys. Rev. B 88, 075420 (2013).

Gong, Y. et al. Spatially controlled doping of two-dimensional SnS2 through intercalation for electronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 294–299 (2018).

Chang, Y. M. et al. Reversible and precisely controllable p/n-type doping of MoTe2 transistors through electrothermal doping. Adv. Mater. 30, 1706995 (2018).

Fang, H. et al. High-performance single layered WSe2 p-FETs with chemically doped contacts. Nano Lett. 12, 3788–3792 (2012).

Hu, H. et al. Recent advances in doping engineering of black phosphorus. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 5421–5441 (2020).

Beck, M. E. & Hersam, M. C. Emerging opportunities for electrostatic control in atomically thin devices. ACS Nano 14, 6498–6518 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Recent progress on localized field enhanced two-dimensional material photodetectors from ultraviolet-visible to infrared. Small 13, 1700894 (2017).

Luo, P. et al. Doping engineering and functionalization of two-dimensional metal chalcogenides. Nanoscale Horiz. 4, 26–51 (2019).

Liu, C. et al. Highly reliable van der Waals memory boosted by a single 2D charge trap medium. Adv. Mater. 36, 2305580 (2024).

Tan, Z. D. et al. Reconfigurable logic and in‐memory computing based on electrically controlled charge trapping in dielectric engineered 2D semiconductor transistors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2417887 (2025).

Wang, X., Liu, X., Zhou, Y., Yuan, K. & Zhou, D. Z. Reconfigurable Quasi‐nonvolatile memory/subthermionic FET functions in ferroelectric–2D semiconductor vdW architectures. Adv. Mater. 34, 2200032 (2024).

Chen, F. et al. Reversible charge‐polarity control for multioperation‐mode transistors based on van der Waals heterostructures. Adv. Sci. 9, 2106016 (2022).

Kim, S. W. et al. Nonvolatile reconfigurable logic device based on photoinduced interfacial charge trapping in van der waals gap. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 22131–22138 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Synchronous regulation of hydrophobic molecular architecture and interface engineering for robust WORM-type memristor. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2404625 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. A single-crystalline native dielectric for two-dimensional semiconductors with an equivalent oxide thickness below 0.5 nm. Nat. Electron. 5, 643–649 (2022).

Chamlagain, B. et al. Thermally oxidized two-dimensional TaS2 as a high-k gate dielectric for MoS2 field-effect transistors. 2D Mater. 4, 031002 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. Ppb-level NO2 sensing properties at room temperature of ultra-thin SnS2 nanopetals annealed at different temperatures. Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 370, 132398 (2022).

Shvets, V. A. et al. Electronic structure and charge transport properties of amorphous Ta2O5 films. J. Non-crystalline Solids 354, 3025–3033 (2008).

Zhao, R. et al. Tuning phase transitions in 1T-TaS2 via the substrate. Nano Lett. 17, 3471–3477 (2017).

Gritsenko, V. A. et al. Nanoscale potential fluctuations in nonstoichiometrics tantalum oxide. Nanotechnology 29, 425202 (2018).

Fan, S. et al. Excitations of intercalated metal monolayers in transition metal dichalcogenides. Nano Lett. 21, 99–106 (2020).

Revelli, J. F. & Disalv, F. J. Tantalum disulfide (TaS2) and its intercalation compounds. Inorg. Syntheses: Nonmolecular Solids 30, 155–169 (1995).

Reisman, A., Holtzberg, F., Berkenblit, M. & Berry, M. Reactions of the group VB pentoxides with alkali oxides and carbonates. III. Thermal and X-Ray phase diagrams of the system K2O or K2CO3 with Ta2O5. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 78, 4514–4520 (1956).

Terrones, H. et al. New first order Raman-active modes in few layered transition metal dichalcogenides. Sci. Rep. 4, 4215 (2014).

Li, Y., Xiao, J., Cao, X., Gu, Z. & Zhang, W. Lateral WSe2 homojunction through metal contact doping: excellent self-powered photovoltaic photodetector. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2213385 (2023).

Yang, F. S. et al. Oxidation-boosted charge trapping in ultra-sensitive van der Waals materials for artificial synaptic features. Nat. Commun. 11, 2972 (2020).

Lan, C. et al. The origin of gate bias stress instability and hysteresis in monolayer WS2 transistors. Nano Res. 13, 3278–3285 (2020).

Xiao, B. & Watanabe, S. Oxygen vacancy effects on an amorphous-TaOX-based resistance switch: a first principles study. Nanoscale 6, 10169–10178 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the funding support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62371448, 62125112, U24A20228, 62204254, 62301553, 62401563, 52270130), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Science (XDB0520301), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20243004), the Foundation Research Project of Jiangsu Province (BK20230234), the Basic Research Development Program of Suzhou (SJC2023004) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M742556). The authors are grateful for the technical support of AFM and Photolithography from the Nano-X Vacuum Interconnected Workstation of Suzhou Institute of Nano-Tech and Nano-Bionics (SINANO), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Ting Zhang is an Editor for the journal, no other author has reported any competing interest.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, X., Guan, K., Sun, F. et al. Polarity control of 2D semiconductor for reconfigurable electronics. Microsyst Nanoeng 11, 178 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01029-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01029-8