Abstract

Ultrafast temperature field detection and identification is crucial for applications ranging from environmental sensing and biomedical monitoring to thermal management in advanced energy systems. Conventional temperature sensors—comprising discrete sensing arrays, data storage units, and external processors—suffer from high latency due to slow sensor response, repeated analog-to-digital conversions, and extensive data transmission inherent to von Neumann architectures. Here, we report a diamond array-based quantum sensor that integrates temperature sensing and real-time processing within a unified in-sensor computing (ISC) architecture. Exploiting the strong linear correlation between temperature and the zero-field splitting of nitrogen-vacancy (NV) color center centers in diamond, we realize a fixed-frequency temperature sensor with ultrafast response and tunable responsivity, enabled by multi-parameter microwave modulate. Matrix-vector multiplication of temperature intensity and responsivity, combined with Kirchhoff’s current summation, enables direct execution of neural-network-style computations on sensed data. The proposed system achieves a single-shot detection and identification latency of just 196.8 μs, as experimentally validated. This work demonstrates a scalable ISC-enabled quantum sensing paradigm, offering a promising route toward high-speed, low-power intelligent temperature field detection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Temperature field detection and identification technologies are vital across diverse domains, including industrial manufacturing, energy infrastructure, medical diagnostics, and fire safety response. The development of ultrafast-response temperature detection and identification sensors could address key challenges in these fields1,2,3,4. For example, real-time thermal monitoring in new energy vehicles can help prevent catastrophic battery failures5,6,7, while repaid and precise temperature tracking in biomedical devices can improve therapeutic outcomes8,9. Conventional temperature sensing systems typically follow a von Neumann architecture, comprising discrete sensing arrays, memory modules, and processors10. In such systems, the sensor array first captures thermal data-often requiring more than 1 ms (thermistors: 100 ms–10 s11; thermocouples: 1 ms–1 s12)—followed by analog-to-digital conversion and storage (100 ns–10 μs13), and finally offloaded to a processor for advanced artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm-based tasks such as classification and feature extration, which may consume up to several seconds depending on algorithm complexity14. Such von Neumann architecture-based sensors suffer from high latency, energy consumption, and hardware costs15. Recent advances in sensing and AI have driven efforts to eliminate data interfaces between sensing arrays, memory, and processors, aiming to develop novel sensor architectures. While ISC (in-sensor computing)-based ultrafast optical sensors have emerged using responsivity-tunable 2D materials16,17,18,19,20,21,22, temperature field ISC sensors remain unrealized due to the slow response and fixed responsivity of conventional temperature sensors (e.g., thermistors, thermocouples, thermal infrared).

Herein, we demonstrate a temperature field detection and identification sensor based on a diamond array, where each unit operates as an ultrafast temperature sensor utilizing nitrogen-vacancy (NV) color centers. The zero-field splitting frequency shift of NV color centers occurs on a femtosecond timescale, comparable to electron transistions23,24. Operating under a fixed microwave frequency, the sensor’s response time is limited only by the photoresponse time of the Si-PIN photodetector (1–100 ns) and the intrinsic thermal conductivity of diamond [2000–2200 W/(m·K), the highest among all known solids25], resulting in a substantial speed advantage over conventional thermal sensors. Through precise microwave modulation in both frequency and power, we realize temperature responsivity that is tunable in both magnitude and polarity. Leveraging this tunable behavior, we construct an in-sensor computing (ISC) architecture that integrates sensing and computation within a unified physical layer. Specifically, the diamond array performs real-time matrix-vector multiplication of temperature intensities and responsivities, and utilizes Kirchhoff’s current summation law to execute fully connected artificial neural network (ANN) operations—directly on the analog sensor output. The resulting temperature field detection and identification diamond quantum sensor (TDI-DQS) integrates the ultrafast characteristics of quantum sensing with the computational efficiency of ISC26, eliminating the need for discrete memory and processor modules and avoiding massive redundant data transmission. This monolithic approach significantly reduces latency, power consumption, and hardware complexity, offering a compelling solution for high-speed, intelligent temperature sensing in advanced applications.

Results

Ultrafast temperature field detection and identification diamond quantum sensor (TDI-DQS)

Conventional temperature field sensors based on von Neumann architectures are composed of three discrete modules: a temperature sensor array, memory, and processor. During operation, the sensor array captures external thermal signals, converts them into digital data for storage, and subsequently transmits them to the processor for advanced tasks such as recognition, classification, edge processing, and selective attention. This sequential sensing-storage-computation workflow, combined with the inherently slow response of traditional sensors, leads to substantial latency27. Additionally, frequent and often redundant data transfer across bus interfaces further increases energy consumption and system complexity. To overcome these limitations, we propose the TDI-DQS, which employs a diamond NV color center array within an ISC architecture. This design physically integrates sensing, memory and processing, enabling real-time, low-latency computation directly within the sensor28. The TDI-DQS comprises a spatially structured diamond array and parallel compensation resistor array (Fig. 1a). The diamond array is divided into N pixel regions, each containing M subpixels. Each subpixel operates as an ultrafast, responsivity-tunable diamond temperature sensor. Subpixels with identical indices across all pixel regions are connected in parallel to form M current outputs. The compensation resistor array—comprising M resistors, RC—is used to offset baseline currents, ensuring zero-point calibration of the output current signal. This hardware configuration effectively realizes the operations of a fully connected artificial neural network (ANN, Fig. S1). When exposed to a temperature field, subpixels perform multiplication: Inm = RnmTn, where Rnm is the subpixel temperature responsivity and Tn is the temperature intensity at the n-th pixel region (n = 1, 2,…, N; m = 1, 2,…, M denote the pixel and sub-pixel indices, respectively). Simultaneously, interconnected subpixels execute current summation via Kirchhoff’s law:

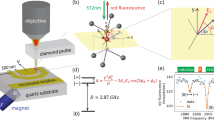

a Schematic layout of the temperature field detection and identification quantum sensor implemented with a diamond array. It consists of N pixel regions. Each pixel region contains M sub-pixels. Sub-pixels sharing the same index across all pixel regions are connected in parallel to form M current outputs. These outputs are connected in parallel with M compensation resistors (Rc) to achieve zero-baseline compensation for the sensor output response curve. b Structure of a TDI-DQS sub-pixel, comprising two diamond temperature sensors. The A-diamond sensing unit is not excited by a microwave signal; its output is solely influenced by the temperature-induced non-radiative transition enhancement effect (NRTE-E). The B-diamond sensing unit is microwave-excited; its output reflects the superimposed states of NRTE-E and the zero-field splitting effect (ZFS-E). The A-unit current is inverted and then connected in parallel with the B-unit output, resulting in an output of B-unit solely dependent on ZFS-E. c Device composition of a diamond temperature sensing unit, including a laser, antenna, diamond, filter film, and Si-PIN photodiode. Inset shows the crystal structure of the NV color center. d Energy level structure of the NV color center. e Mechanism of ultra-fast response speed and tunable responsivity for the diamond temperature sensor. A fixed-frequency ultra-fast temperature detection method is proposed based on the high linear correlation of its optically detected magnetic resonance (ODMR) output. Responsivity magnitude and sign (positive/negative) tuning is achieved by intervening in the electron spin resonance process of the NV color center via multi-parameter (frequency/power) microwave control. f Electron spin state distributions in the sub-pixel diamond under different temperatures and microwave conditions, demonstrating the tunable responsivity characteristic of the diamond temperature sensor

The system performs matrix-vector multiplication I = RT, where R = (Rnm) represents the temperature responsivity matrix of the diamond sensing array, T = (T1,T2,…, TN)T denotes the temperature field pattern vector, and I = (I1,I2,…,IM)T is the output vector. Through training, the TDI-DQS updates R to achieve identification and classification of temperature field targets29. This integrated sensing-processing paradigm is extensible; designing new fully-connected ANN functional models (Supplementary Fig. 1) and modifying the diamond array connectivity could enable encoder or edge processor functionalities.

As the temperature of the diamond NV color center increases, the non-radiative transition of electrons gradually intensifies, leading to an increase or decrease in the probability of excited state ms = ±1 electrons converting to ground state ms = 0 electrons through the intermediate state 1A130. Since this process does not emit photons, an increase in temperature results in a continuous decay of the fluorescence intensity of the NV color center (Supplementary Fig. 2). To address this thermal-induced fluorescence degradation, we introduce a differential sub-pixel architecture in the TDI-DQS design (Fig. 1b). Each sub-pixel comprises two diamond sensing units: a microwave-excited B-unit and a non-excited A-unit. The B-unit’s fluorescence response reflects the combined influence of the non-radiative transition enhancement effect (NRTE-E) and the zero-field splitting effect (ZFS-E), while the A-unit captures only the NRTE-E contribution. The output current from the A-unit is inverted using a voltage follower circuit. The resulting differential structure enhances the thermal specificity of the sensor, ensuring accurate temperature-responsivity modulation under varying thermal environments.

The diamond temperature sensor within each TDI-DQS sub-pixel (Fig. 1c) consists of a 532 nm laser, a 2.87 GHz microwave antenna, a diamond sensing element, a bandpass filter (600–800 nm)(Supplementary Fig. 3), and an Si-PIN photodetector. The temperature-sensitive element is the NV color center in diamond—a spin-lattice defect formed by a nitrogen atom substituting a carbon atom adjacent to a lattice vacancy. Under equilibrium conditions, the NV color center exhibits a ground-state spin triplet ³A₂, with spin sublevels (ms = 0 and ms = ±1) (Fig. 1d). Upon excitation with 532 nm laser light, electrons in the ground state are promoted to excited state. Electrons in the ms = 0 state predominantly return to the ground state via radiative decay, emitting fluorescence at 637 nm31. In contrast, a fraction of electrons in the ms = ±1 states undergo non-radiative relaxation through an intermediate singlet state ¹A₁, resulting in fluorescence quenching. This spin-selective radiative behavior enables optical readout of the NV spin state: higher fluorescence intensity indicates a greater population in the ms = 0 state. When a microwave field is applied, transitions between ms = 0 and ms = ±1 states are induced if the photon energy hf matches the energy splitting between the levels. This spin resonance leads to a redistribution of populations and a corresponding dip in fluorescence intensity, allowing detection of the resonance frequency through optical means. Importantly, the zero-field splitting (ZFS) parameter D shifts linearly with temperature at a rate of ΔD ≈ –74 kHz/°C over a broad mid-temperature range (with minor variations due to strain and impurities), resulting in a corresponding shift in the resonance frequency. Consequently, the external temperature field can be accurately inferred by monitoring the resonance frequency shift via frequency-swept optical detection.

The diamond temperature sensing array exhibits both ultra-fast response and tunable responsivity—two essential prerequisites for enabling the ISC architecture in the TDI-DQS. In conventional designs, NV color center-based temperature sensors typically rely on a PID feedback system to demodulate temperature information via continuous microwave frequency modulation and closed-loop control32,33. However, such PID-based approaches inherently suffer from latency due to slow feedback loops, complex signal processing, and repeated analog-to-digital conversions. To overcome these limitations, we employ a fixed-frequency operational mode, leveraging the strong linear correlation between the ODMR spectrum and temperature. As shown in Fig. 1e, the fluorescence intensity of an NV color center decreases linearly with temperature as the spectral dip in the ODMR curve shifts towards lower frequencies (red curve). By selecting a fixed microwave frequency aligned with either side of the dip, the sensor’s output exhibits either a negative or positive linear response to temperature: for instance, fixing the frequency at the blue dashed line yields a negative slope (blue fit), while the pink dashed line yields a positive slope (pink fit). This strategy allows the sign of responsivity to be tuned simply by adjusting the microwave excitation frequency. Furthermore, the magnitude of responsivity can be tuned via microwave power. Increasing the microwave signal power enhances the probability of spin transitions between the ms=0 and ms = ±1 states by generating more resonant photons. As the ms = 0 population correlates directly with fluorescence intensity, this results in a deeper spectral dip and a steeper slope in the fluorescence-temperature response curve. Therefore, independent control over microwave frequency and power enables dual-parameter tuning of the sign and magnitude of temperature responsivity. Figure 1f illustrates the distribution of NV color center electron spin state within the diamond sub-pixel of the TDI-DQS under varying temperature and microwave conditions. In the differential architecture, the output current follows the expression INM = -INM-A + INM-B + IC, where IC is the compensation current, and INM-A and INM-B denote the currents from the non-excited (A) and microwave-excited (B) diamond units, respectively. As the temperature increases, the population of ms = 0 NV electrons in both A and B units decreases due to NRTE-E. However, under microwave excitation, the B-unit additionally exhibits the influence of the zero-field splitting effect (ZFS-E): at a frequency corresponding to a positive temperature responsivity, the ms = 0 population in the increases with temperature, whereas at a negative response frequency, it decreases further. To isolate the ZFS-E contribution, the current from the A-unit-reflecting only NRTE-E- is inverted via a voltage follower circuit and summed in parallel with the B-unit output. This differential configuration effectively cancels the NRTE-E component, enabling a clean, ZFS-E-dominated temperature response. By tuning the microwave frequency applied to the B-unit, the sign of the temperature responsivity can be selected. Additionally, increasing the microwave power further modifies the transition probability between ms = 0 and ms = ±1 states, thereby adjusting the magnitude of the responsivity: enhancing the fluorescence drop at negative-response frequencies or amplifying the intensity increase at positive-response frequencies. In summary, the fixed-frequency operating mode—combined with dual-parameter microwave control—yields a diamond temperature sensor with both ultrafast response and highly tunable responsivity in sign and magnitude, providing the physical foundation for implementing the ISC architecture in the TDI-DQS.

Implementation of the Ultra-fast TDI-DQS

The photoluminescence spectrum of the diamond NV color center was first characterized, as shown in Fig. 2a. The effective emission lies within the 600–800 nm range, where environmental optical noise above ≥800 nm is minimal. To enhance signal fidelity, a long-pass filter (≥600 nm) was deposited on the polished surface of the diamond, effectively improving the sensor’s sensitivity and signal-to-noise ratio. In the TDI-DQS, both temperature field acquisition and data processing are executed entirely in the analog domain. As a result, the overall detection and identification speed is limited solely by the current generation rate of the diamond temperature sensors and the bandwidth of the operational amplifiers. This allows real-time operation at speeds orders of magnitude faster than those achievable with traditional systems that rely on discrete sensing, memory, and processing modules. Directly measuring the TDI-DQS response time, however, presents a significant challenge due to the limitations of conventional thermal excitation sources, which operate at extremely low modulation frequencies (e.g., vapor heaters <1 Hz and resistive wire heaters <0.1 Hz). These constraints make it difficult to experimentally demonstrate the ultrafast response advantage of the TDI-DQS using standard thermal input methods.

a Photoluminescence spectrum (532 nm excitation) of the diamond NV color center. b Simulation results of temperature changes in the center of a diamond (1 × 1 × 0.6 mm³) under conditions where the upper surface is at 100 °C and the remaining five surfaces are at 20°C. c Optical signal detection and data processing response time of the TDI-DQS. d Frequency-swept outputs at different temperatures. e Determination of fixed frequencies and linear ranges. f Relationship between baseline current of the frequency-swept output and temperature. g Relationship between the peak-to-peak current in the frequency-swept output and temperature. h The relationship between dip current of the frequency-swept output and microwave power. i Output response curves under varying microwave power at fixed frequencies

To evaluate the response time of the TDI-DQS, we decomposed the temperature detection and identification process into two sequential steps. The first step involves the thermal response of the diamond itself, which was assessed via simulation of heat conduction dynamics. Given that the conversion of temperature information into a fluorescence signal in the NV color center occurs almost instantaneously (on the femtosecond timescale, comparable to the electron transition time), the second step-optical signal detection and processing-was exmined experimentally using a pulsed laser system. A diamond model matching the dimensions of the TDI-DQS (1 mm × 1 mm × 0.6 mm) was constructed for simulation. The temperature of the upper surface of the diamond is set to 100 °C, while the temperatures of the other five surfaces are set to 20 °C. And using material parameters (Supplementary Fig. 4) [Parameters: density 3515 kg/m³, thermal conductivity 2300 W/(m·K), specific heat capacity 515 J/(kg·K)], the simulation results showed that the central temperature of the diamond reaches 90% of its final value within 196.7 μs (Fig. 2b). To experimentally determine the optical signal response time, a 532 nm pulsed laser system was established (Supplementary Fig. 5). An acousto-optic modulator (AOM) was used to modulate the laser and generate high-frequency pulsed, which were directed in to the TDI-DQS. As shown in Fig. 2c, the system completed fluorescence signal detection and processing within 113.6 ns, and the data exhibits excellent reproducibility (Supplementary Fig. 6). Combining the thermal and optical response times yields an estimated total detection and identification latency of approximately 196.7 μs + 113.6 ns ≈ 196.8 μs, which highlights the significant speed advantage of the TDI-DQS over conventional thermal sensing systems. Further improvements in response speed are anticipated through optimization of the operational amplifier's bandwidth and photodetector performance, paving the way for future ultra-high-speed temperature field detection and identification applications.

The frequency-swept output signals of the sensor were characterized at various temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 7). As temperature increases, the dip position in the ODMR spectrum (Fig. 2d) exhibits a linear frequency shift, with a slope of approximately −74 kHz/°C). In addition to this spectral frequency shift, a gradual decrease in the baseline current and a reduction in the peak-to-peak current difference were also observed. To determine the optimal fixed microwave frequencies for positive and negative temperature responsivity, we identified regions of high linearity on either side of the ODMR dip. Linear fits were selected to maximize both correlation and usable range (Fig. 2e). Based on a comparison of fits across different spectral intervals (Supplementary Fig. 8), the optimal frequency for positive responsivity was identified as 2.87259 GHz (R² = 0.993), and for negative responsivity was indentified as 2.86257 GHz (R² = 0.991). These correspond to a linear operating range of approximately ΔT = 63.1°C [(2.86257 GHz–2.86724 GHz) / (−74 kHz/°C) = 63.1°C; (2.87259 GHz - 2.87727 GHz) / (−74 kHz/°C) = 63.2°C]. To evaluate the impact of baseline current and peak-to-peak current difference variations, we analyzed the linear relationship between temperature and them. A strong linear correlation was observed in both cases: R² = 0.989 for baseline current (Fig. 2f), and and R² = 0.998 for the peak-to-peak current difference (Fig. 2g). Therefore, the baseline current variation phenomenon is addressed using subpixels of a dual-diamond differential structure, the additional diamond units without microwave excitation can real-time compensate the baseline current variations caused by NRTE-E. And since the superposition of two linear variation processes still results in a linear variation process, the peak-to-peak current variation phenomenon does not affect the linearity quality of the sensor. It merely introduces a slight reduction in slope relative to the ideal fitted line, with a maximum attenuation of 14.9% at the upper limit of the temperature range (ΔT_max).

The frequency-swept outputs of the diamond sensor was further characterized under varying microwave powers levels (Supplementary Fig. 9). As the microwave power increased, the dip current progressively decreased, indicating a steeper slope in the fitted fluorescence–temperature response curve. This trend saturated at approximately 26 dBm (Fig. 2h), confirming that the the magnitude of temperature responsivity can be effectively modulated through microwave power control. Additionally, output response curves were measured at fixed positive and negative responsivity frequencies across a temperature range of 36.2–99.2°C. The results exhibited excellent linearity and high symmetry (Fig. 2i), further validating the tunability and stability of the sensor. These characteristics support the feasibility of implementing the ISC architecture using the diamond temperature sensing array, with both response direction and magnitude readily adjustable via microwave parameters.

The TDI-DQS array consists of 9 pixel regions, each comprising 3 sub-pixels, resulting in a 9 × 3 architecture. Figure 3a illustrates the circuit connection scheme of the array. Sub-pixels with the same index across all pixel regions are connected in parallel along with a corresponding compensation resistor to generate a single output channel. Each sub-pixel includes two diamond temperature sensors connected in parallel with opposite current directions-only one of which is microwave-excited, while the other serves as a baseline compensation unit and operates without microwave excitation. The overall size of the TDI-DQS system is 150 mm × 150 mm (Fig. 3b). The first magnified view highlights a single pixel region (scale bar 10 mm), containing three distinct sub-pixels (scale bar 3 mm), composed of one complete diamond NV color center-based temperature sensor (including laser, diamond, antenna, optical filter, detector) and one non-excited diamond sensor without an antenna for baseline drift correction. We calibrated the initial temperature responsivity of all 27 sub-pixels in the array at a microwave power of 28 dBm (Fig. 3c). The results confirmed excellent consistency across the array, with an average responsivity of 93.77 μA/°C and a total variance 170.07. In practical operations, we adjust the temperature responsivity of the diamond array twice through the antenna microwave power, ensuring that the adjusted actual temperature responsivity ratio is consistent with the temperature responsivity ratio obtained from training. This makes the actual output ratio of TDI-DQS highly consistent with the training result ratio, guaranteeing its high recognition rate characteristic. Furthermore, we evaluated the real-time current output of the three output channels under uniform heating conditions (99.2 °C, the upper limit of the linear range) at the same microwave power. The outputs exhibited exceptional signal stability over 100 seconds, demonstrating the robustness and reliability of our large-scale ODMR sensor integration strategy. While integrating a large-scale diamond temperature sensor array, TDI-DQS maintains its excellent sensitivity advantage. By collecting noise floor signals from sub-pixels for 100 seconds (with microwave modulation power of 28 dBm)34, the noise spectral density was ultimately calculated to be 219.7 μK/Hz1/2. Meanwhile, as the operation of TDI-DQS does not rely on any external memory or processing, it also has certain advantages in terms of power consumption and cost compared to conventional temperature field detection and identification sensors (Table 1). The detailed calculation process is analyzed in detail in Supplementary Note 1.

a Circuit configuration of the 9 × 3 diamond array. Each subpixel is paralleled with a diamond sensor that does not require microwave excitation for baseline current compensation. b Macroscopic image of TDI-DQS with a scale of 20 mm. First magnification: image of a single temperature pixel region composed of three subpixels, scale 10 mm. Second magnification: image of a single subpixel consisting of two diamond temperature sensors (one of which is excited by microwaves), scale 3 mm. c Initial responsivity distribution of 27 diamond NV color center temperature sensors in TDI-DQS, with consistency evaluation. d Three-channel current outputs at 99.2 °C (100 s). e The noise floor and noise spectral density of (e) TDI-DQS sub-pixel (microwave power 28 dBm) over a 100-second period

Ultra-fast temperature field detection and identification using TDI-DQS

TDI-DQS enables ultrafast detection and real-time data processing of temperature fields with varying spatial distributions. Target classification and recognition are accomplished by analyzing the characteristic output currents from its three parallel channels-where the dominant output current uniquely corresponds to a specific spatial temperature pattern (Fig. 4a). To implement this functionality, we designed a fully connected 9 × 3 artificial neural network (ANN) classifier based on the architecture of the TDI-DQS (Fig. 4b). The ANN was trained offline using labeled datasets representing three prototypical temperature field distributions associated with electronic device faults: ‘Battery failure (I1 ≫ I2 ≈ I3 ≈ 0)’, ‘Radiator failure (I2 ≫ I1 ≈ I3 ≈ 0)’, and ‘Chip failure (I3 ≫ I1 ≈ I2 ≈ 0)’ (Supplementary Fig. 10). During training, the mean squared error (MSE) loss function converged to 0.01 within 200 epochs, and a simulated recognition accuracy of 98.54% was achieved under a noise level of 0.2 (Supplementary Fig. 11). The resulting optimized 27-element responsivity matrix was then physically encoded into the TDI-DQS by adjusting the microwave excitation parameters at each sub-pixel (Fig. 4c). This programming step enabled the device to directly classify spatial temperature field patterns in hardware, facilitating intelligent fault detection in thermal management scenarios. Moreover, due to the high robustness of TDI-DQS, which is similar to artificial neural networks, the introduction of thermal noise from microwave antennas during the encoding process of the responsivity matrix does not significantly affect the actual recognition rate (Supplementary Note 2). Cooling fans, heat dissipation metal blocks, or active temperature control systems such as ETC can be used to further eliminate the impact of system thermal noise and improve recognition rates.

a The TDI-DQS performs temperature field detection and real-time data processing, enabling ultra-fast identification of electronic device faults by evaluating output current characteristics. b Schematic of the ANN classifier (adapted to 9 × 3 array scale TDI-DQS), through which the temperature field of three different types of faults of electronic equipment is trained with label classification task: ‘Battery failure(I1)’, ‘Radiator failure (I2)’ and ‘Chip failure (I3)’. The right training results show that the loss function decreased to 0.01 within 200 training epochs. c Post-training temperature responsivity distribution of the sensor. d Experimental setup for temperature field recognition, using insulated NiCr heating elements to apply multi-pixel temperature fields. e Sensor output currents for three different types of temperature fields

To experimentally validate the temperature field detection and identification capabilities of the TDI-DQS, a dedicated test platform was constructed (Fig. 4d). The setup included a multi-channel oscilloscope for real-time signal acquisition, an integrated fixed-frequency microwave generator for responsivity tuning, and insulated nichrome heating elements for generating temperature fields with distinct spatial patterns. As shown in Fig. 4e, the TDI-DQS was exposed to three representative spatial temperature distributions-‘Battery Failure shaped’, ‘Radiator Failure shaped’, and ‘Chip Failure shaped’ all maintained at 99.2 °C, the upper limit of the device’s linear response range. The corresponding three-channel output currents displayed clear, well-separated responses for each pattern, with one dominant current channel uniquely associated with each distribution. The three channel output current of TDI-DQS for detecting temperature fields of different fault types highly matches the ideal output value of the model (Supplementary Note 3), proving its excellent ability to resist environmental interference. In addition, due to the magnetic sensitivity of diamond sensors, by adding an additional diamond sensor to the sub-pixel to design a three-unit differential structure (Supplementary Fig. 13), anti-magnetic field interference during temperature detection can be achieved. These results confirm the TDI-DQS’s ability to accurately detect and distinguish spatial temperature field configurations in real time, demonstrating its practical potential for intelligent thermal diagnostics.

TDI-DQS, with its high technical maturity and advantages in recognition time, power consumption, and cost, is expected to become a practical sensor. Through continuous operation analysis of TDI-DQS multi-module units (Supplementary Note 4), the current main degradation mechanisms are: long-term operation of the array laser and excessive heat introduced by the testing environment, leading to laser component failure and photodetector performance drift. By integrating TDI-DQS with an active temperature control system35, performance and lifespan can be significantly improved, enhancing practicality.

Conclusion

We have developed an ultrafast diamond-based temperature field detection and identification sensor operating in fixed microwave frequency mode, wherein tunable temperature responsivity-both in magnitude and polarity-is achieved via multi-parameter microwave spin manipulation (frequency, power). By leveraging this tunable quantum sensing capability, we are implementing an ISC architecture tailored for real-time temperature field detection and identification. The resulting platform, termed the TDI-DQS, combines high-speed quantum sensing with embedded neural-network-style computation, offering a compact solution with low power consumption and minimal hardware overhead. The fabricated TDI-DQS device was successfully programmed to execute a fully connected artificial neural network (ANN) classifier for spatial temperature field recognition. It demonstrated efficient and accurate multi-target classification under realistic thermal conditions. Our results establish the TDI-DQS as a viable and scalable hardware solution for intelligent thermal sensing, offering promising opportunities for deployment in energy system diagnostics, biomedical monitoring, and advanced industrial applications.

Methods

Device fabrication

The diamond used (size: 1 × 1 × 0.6 mm3) is of the Element Six company’s high-temperature and high-pressure CD1008 (100) model, with a nitrogen content of 100 ppm, and its thickness was reduced through laser cutting. After undergoing 10 MeV electron irradiation for 4 hours and annealing at 850 °C for 2 h, the nitrogen vacancy concentration in the diamond is approximately 0.8 ppm. A filter film is deposited on its polished surface, with a cutoff at 532 ± 35 nm (OD2-3) and a transmittance of ≥90% in the 600–800 nm range. A folded dipole array antenna (size: 22 × 9 × 0.6 mm3)(exciting only one diamond in each sub-pixel) is employed, operating at a frequency of 2.87 GHz (VSWR ≤ 2.5). A circuit structure is fabricated by horizontally integrating 54 laser diodes (GH15130C8C, Manufacturer: SHARP, size: 4.4 × 5.1 × 1.8 mm3) with copper plates for heat dissipation. According to the ANN model, 54 photodetectors (TEMD5010X01, Manufacturer: Vishay, size: 5 × 4.2 × 1.2 mm3) are integrated, utilizing OPA380 (Manufacturer: Texas Instruments) operational amplifier chips for signal amplification. Each group consists of 18 photodetectors (9 of which provide reverse current for baseline compensation, allowing adjustment of the operational amplifier to make the temperature-baseline variation slope consistent for the two diamonds in each sub-pixel) and one compensation resistor connected in parallel to form an independent output. Finally, all modules are assembled to complete the device fabrication.

Experimental setup

The three channels of the device are all equipped with I/V conversion circuits, and all data were tested using the Tektronix MDO4104C oscilloscope. In the “Temperature Field Target Detection and identification” experiment, insulated copper-nickel alloy heating wires were used to construct temperature fields with different patterns. In the photoresponse time test experiment, a pulse signal generator was used to control the AOM, regulating the grating to produce pulse laser signals (532 nm), thereby completing the evaluation of the device’s photoresponse time.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are included in the manuscript and supplemental information and will be made available from the lead contact upon reasonable request.

References

Chen, B., Gao, D., Yang, J. & Li, Z. Design of an active detection system for ice and snow pollutants and freezing temperature on runway. Meas Sci Technol 34, 105102 (2023).

Feng, W. et al. Online defect detection method and system based on similarity of the temperature field in the melt pool. Addit Manuf 54, 102760 (2022).

Kacso, G., Hantila, I. F., Drosu, O. M., Maricaru, M. & Stanculescu, M. Qualitative analysis of the temperature field produced by an early stage tumor. Rev Roum Des Sci Tech -Ser Electrotech ET Energ 59, 433–443 (2014).

Yu, R., Han, J., Bai, L. & Zhao, Z. Identification of butt welded joint penetration based on infrared thermal imaging. J Mater Res Technol 12, 1486–1495 (2021).

Bhaskar, K. et al. Data-driven thermal anomaly detection in large battery packs. Batteries 9, 70 (2023).

Chen, S. et al. Battery pack temperature field compression sensing based on deep learning algorithm. In: Proceedings of 2019 14th IEEE International Conference On Electronic Measurement & Instruments (ICEMI) (2019).

Zhao, L. et al. Integrated arrays of micro resistance temperature detectors for monitoring of the short-circuit point in lithium metal batteries. Batteries 8, 264 (2022).

Vetshev, P. S. et al. Radiothermometry in diagnosis of thyroid diseases. Khirurgiia 86, 54–58 (2006).

Zaman, N. I. D., Hau, Y. W., Leong, M. C. & Al-ashwal, R. H. A. A review on the significance of body temperature interpretation for early infectious disease diagnosis. Artif Intell Rev 56, 15449–15494 (2023).

Ren, W. et al. A novel integral image recognition method and system with verification measurement by sensors for hot steel-bar stack accident detection. Sens Mater 36, 2297–2314 (2024).

Nakajima, T. & Tsuchiya, T. Ultrafine-fiber thermistors for microscale biomonitoring. J Mater Chem C 11, 2089–2097 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Simulation, fabrication, and characteristics of high-temperature, quick-response tungsten-rhenium thin-film thermocouple probe sensor. Meas Sci Technol 33, 105105 (2022).

Tang, X. et al. Low-Power SAR ADC design: overview and survey of state-of-the-art techniques. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst I-Regul Pap 69, 2249–2262 (2022).

Azizimazreah, A. & Chen, L. Polymorphic accelerators for deep neural networks. IEEE Trans Computers 71, 534–546 (2022).

Feng, W., Qin, T. & Tang, X. Advances in Infrared Detectors for In-Memory Sensing and Computing. Photonics 11, 1138 (2024).

Chen, C., Zhou, Y., Tong, L., Pang, Y. & Xu, J. Emerging 2D ferroelectric devices for in-sensor and in-memory computing. Adv Mater 37, 2400332 (2025).

Kumar, D. et al. Artificial visual perception neural system using a solution-processable MoS2-based in-memory light sensor. Light-Sci Appl 12, 109 (2023).

Li, C. et al. Charge-selective 2D heterointerface-driven multifunctional floating gate memory for in situ sensing-memory-computing. Nano Lett 24, 15025–15034 (2024).

Mennel, L. et al. Ultrafast machine vision with 2D material neural network image sensors. Nature 579, 62–6 (2020).

Sharmila, B. & Dwivedi, P. Wafer scale WS2 based ultrafast photosensing and memory computing devices for neuromorphic computing. Nanotechnology 35, 425201 (2024).

Cao, -B. et al. Recent progress on fabrication, spectroscopy properties, and device applications in Sn-doped CdS micro-nano structures. J Semicond 45, 091101 (2024).

Li, Z. et al. A reconfigurable heterostructure transistor array for monocular 3D parallax reconstruction. Nat Electron 8, 46–55 (2025).

Zhang, T. et al. Toward Quantitative Bio-sensing with Nitrogen-Vacancy Center in Diamond. Acs Sens 6, 2077–2107 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Temperature dependence of magnetic sensitivity in ensemble NV centers. Jpn J Appl Phys 63, 062001 (2024).

OnnWitek, Qiu, Anthony & Banholzer Some aspects of the thermal conductivity of isotopically enriched diamond single crystals. Phys Rev Lett 68, 2806–2809 (1992).

Du, Z. et al. Widefield diamond quantum sensing with neuromorphic vision sensors. Adv Sci 11, 2304355 (2024).

Wu, G. et al. Ferroelectric-defined reconfigurable homojunctions for in-memory sensing and computing. Nat Mater 22, 1499-1506 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. An organic electrochemical transistor for multi-modal sensing, memory and processing. Nat Electron 6, 281–291 (2023).

Yu, R. et al. Programmable ferroelectric bionic vision hardware with selective attention for high-precision image classification. Nat Commun 13, 7019 (2022).

Yang, M. et al. A diamond temperature sensor based on the energy level shift of nitrogen-vacancy color centers. Nanomaterials 9, 1576 (2019).

Sumikura, H., Hirama, K., Nishiguchi, K., Shinya, A. & Notomi M. Highly nitrogen-vacancy doped diamond nanostructures fabricated by ion implantation and optimum annealing. Appl Mater 8, 031113 (2020).

Su, J. et al. Fluorescent nanodiamonds for quantum sensing in biology. Wiley Interdiscip Rev-Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 17, e70012 (2025).

Fujiwara, M. & Shikano, Y. Diamond quantum thermometry: from foundations to applications. Nanotechnology 32, 482002 (2021).

Shim, J. H. et al. Multiplexed sensing of magnetic field and temperature in real time using a nitrogen-vacancy ensemble in diamond. Phys Rev Appl 17, 014009 (2022).

Zhang, D.-X. et al. Design and the transient thermal control performance analysis of a novel PCM-based active-passive cooling heat sink. Appl Therm Eng 220, 119525 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants 62175219, 52275576, and U21A20141; and the Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province (202403021223007), and the Sanjin Talent Program of Shanxi Province.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: W.G., H.G., L.W., J.T., and J.L.; Methodology: W.G., J.T., Z.X., F.D., H.W., W.Z., and Z.L.; Investigation: W.G., H.G., and J.T.; Visualization: W.G., H.G., and J.T.; Funding acquisition: H.G., J.T., and J.L.; Project administration: H.G., J.T,. and J.L.; Supervision: H.G., J.T., L.W., and J.L.; Writing-original draft: W.G., L.W. and H.G.; Writing-review & editing: W.G., H.G,. and the other authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, W., Tai, J., Xiang, Z. et al. Temperature field ultrafast detection and identification quantum sensor based on diamond array. Microsyst Nanoeng 11, 244 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01076-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01076-1