Abstract

The recent literature has shown that vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (VSCC) can be stratified into two prognostically relevant groups based on human papillomavirus (HPV) status. The prognostic value of p53 for further sub-stratification, particularly in the HPV-independent group, has not been agreed upon. This disagreement is likely due to tremendous variations in p53 immunohistochemical (IHC) interpretation. To address this problem, we sought to compare p53 IHC patterns with TP53 mutation status. We studied 61 VSCC (48 conventional VSCC, 2 VSCC with sarcomatoid features, and 11 verrucous carcinomas) and 42 in situ lesions (30 differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia [dVIN], 9 differentiated exophytic vulvar intraepithelial lesions [deVIL], and 3 high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions or usual vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia [HSIL/uVIN]). IHC for p16 and p53, and sequencing of TP53 exons 4–9 were performed. HPV in situ hybridization (ISH) was performed in selected cases. We identified six major p53 IHC patterns, two wild-type patterns: (1) scattered, (2) mid-epithelial expression (with basal sparing), and four mutant patterns: (3) basal overexpression, (4) parabasal/diffuse overexpression, (5) absent, and (6) cytoplasmic expression. These IHC patterns were consistent with TP53 mutation status in 58/61 (95%) VSCC and 39/42 (93%) in situ lesions. Cases that exhibited strong scattered staining and those with a weak basal overexpression pattern could be easily confused. The mid-epithelial pattern was exclusively observed in p16-positive lesions; the basal and parabasal layers that had absent p53 staining, appeared to correlate with the cells that were positive for HPV-ISH. This study describes a pattern-based p53 IHC interpretation framework, which can be utilized as a surrogate marker for TP53 mutational status in both VSCC and vulvar in situ lesions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vulvar cancer constitutes <5% of malignancies affecting the gynecologic tract, but accounts for significant patient morbidity and mortality, particularly in the setting of recurrent or treatment refractory disease [1, 2]. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (VSCC) is the most common type of vulvar cancer and develops through two separate etiologic pathways: one that is driven by human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and one that is not [3, 4]. In the HPV-associated pathway, the squamous precursor lesion is known as high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion or usual vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (HSIL/uVIN) and in the HPV-independent pathway, the precursor lesion is known as differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN) [5]. The recent literature has proposed other precursor lesions in the HPV-independent pathway, referred to as deVIL (differentiated exophytic vulvar intraepithelial lesion (deVIL)) and vulvar acanthosis with altered differentiation (VAAD). Both are thought to occur independently of TP53 mutations and lead to well-differentiated or verrucous squamous cell carcinomas [6, 7].

Recent large-scale studies have shown that HPV-independent VSCC is associated with worse clinical outcomes compared with HPV-associated VSCC [8,9,10,11,12]. The prognostic value of p53, a key tumor suppressor, on the other hand, has not been agreed upon. Approximately half of published studies report that p53 is an adverse prognosticator in VSCC, while half have found no association with prognosis [10, 13,14,15,16,17,18]. This disagreement can be attributed to the tremendous variations in p53 immunohistochemical (IHC) interpretation. The vast majority of studies defined abnormal p53 staining by simply evaluating the percentage of cells showing staining, with cutoff values ranging widely from 5 to 70%, and did not take into consideration the distribution and localization of p53 staining [10, 13,14,15,16,17,18].

In 2000, Yang and Hart [19] were the first to propose an approach to p53 IHC interpretation in VSCC and in situ lesions. Recognizing the importance of the basal layer, the regenerative layer of the epidermis [20], they evaluated p53 staining in the basal cell layer, as well as the parabasal (suprabasilar) layers. They found that the labeling index (LI) was significantly higher in dVIN, compared with squamous hyperplasia and lichen sclerosus. Extension of staining into the parabasal layers was seen in dVIN, but not the other entities. This approach pioneered by Yang and Hart [19] almost two decades ago, unfortunately did not propagate into the subsequent literature and even those studies that tried to recapitulate this approach used varied methods of interpretation. Some authors set p53 basal staining LI cutoff values ranging between 10 and 50% [21,22,23]; Al Ghamdi et al. [24] and Ordi et al. [25] did not set cutoff values but reported dVIN p53 basal LIs ranging from 7% to 51% and 60% to 80%, respectively; Other authors [26,27,28,29,30,31] reported increased basal and parabasal p53 staining in dVIN and VSCC with sparse quantitative or qualitative details.

More importantly, very few studies have tried to correlate p53 IHC patterns with the underlying TP53 mutation status. In 2002, Vanin et al. was one of the first to attempt this but considered staining of any intensity of the basal layer as positive. Rolfe et al. [32] and Choschzick et al. [33] only assessed percentage of cells staining, not distribution or intensity. More recent studies observed strong basal and parabasal staining in dVIN and VSCC but without sufficient details to allow for pathologists to evaluate p53 on their own [7, 9, 34].

Before attempting to use p53 immunohistochemistry as either a diagnostic or prognostic tool, we first wanted to establish an approach to interpreting p53 IHC in VSCC and squamous precursor lesions, which pathologists can use in daily practice. In this study, we evaluated p53 IHC patterns in a series of VSCC and in situ lesions (taking into account proportion and intensity of basal layer staining, extent of parabasal layer staining and staining localization [nuclear vs cytoplasmic]), and compared the staining patterns with TP53 mutational status. Given that a larger proportion of TP53 mutations have been reported in HPV-independent VSCC [9, 33,34,35,36], we included a larger number of HPV-independent lesions.

Methods

Cases selection

Cases were selected from the electronic archives of Vancouver General Hospital from 1998 to 2019. Candidate cases were identified on vulvar excision specimens. Preference was given to HPV-independent cases based on morphologic features (absence of HSIL) [3, 10], and to cases where the in situ lesion and VSCC could be macrodissected separately for mutational analysis.

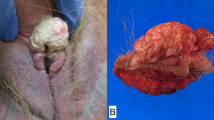

The histology for each case was re-reviewed and re-classified into the following categories: conventional VSCC (invasive carcinoma comprising of malignant squamous cells with variable keratinization and definite stromal invasion), verrucous carcinoma (VC: well-differentiated squamous tumors with minimal cytologic atypia, bullous epithelial pegs, and a broad pushing front into the stroma), VSCC with sarcomatoid features (VSCC-S: poorly differentiated squamous cells exhibiting spindle cell morphology; associated with conventional squamous cell carcinoma in our series), differentiated-type vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN: in situ squamous precursor lesion usually located adjacent to VSCC exhibiting moderate to marked basal nuclear atypia as well as variable degrees of hyperchromasia, karyomegaly, enlarged nucleoli, atypical mitoses, dyskeratosis, elongated, and anastomosing rete ridges), usual-type vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (HSIL/uVIN: in situ squamous lesion exhibiting basaloid morphology, hyperchromasia, crowding, and anisonucleosis), and deVIL (as defined by Watkins et al. [7], in situ squamous precursor lesion exhibiting prominent acanthosis or verruciform morphology, the absence of conspicuous basal atypia and abnormalities in keratinocyte differentiation such as hypogranulosis, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and dyskeratosis). Cases thought to represent VAAD (as defined by Nascimento et al. [6], triad of marked acanthosis with variable verruciform architecture, loss of the granular cell layer with superficial epithelial cell pallor and multilayered parakeratosis) were grouped into the deVIL category.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 4-µm whole tissue sections using the Dako Omnis and Dako EnVision™ FLEX + detection system as per manufacturer recommendations. Sections were mounted onto Dako FLEX microscope slides, air dried for 20 min and baked at 60 °C for 20 min. The heat-induced antigen retrieval method was performed using Envision FLEX Target Retrieval Solution (Dako) in Dako PT Link. The staining steps and incubation times were performed according to the Autostainer Link software. The following antibodies were used p16 (Roche CINtec, E6H4, mouse monoclonal, 1:5 dilution) and p53 (Dako, DO-7, mouse monoclonal, 1:500 dilution).

p16 IHC was scored as positive if there was diffuse block-like cytoplasmic and nuclear staining and as negative for any lesser staining (such as patchy staining or the absence of staining), according to the Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology recommendations [37].

For p53, we evaluated the basal layer for percentage of cells staining counted over 100 cells and the staining intensity into five groups (absent, uniformly weak, uniformly moderate, uniformly strong, or heterogeneous staining of varying intensities). For the parabasal staining, we divided staining into no parabasal extension, 1/3 thickness, 2/3 thickness, or 3/3 (full) thickness, and intensity (uniformly none, weak, moderate or strong, or heterogeneous staining of varying intensities). For VSCC, the basal layer was considered the peripheral cells in the invasive squamous nests and the parabasal layer corresponded to the central portions of the squamous nests. We also noted nuclear vs cytoplasmic localization. Scoring was performed on the area with the strongest staining and corresponded to the area where subsequent cores were taken from the corresponding formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks for TP53 sequencing.

TP53 sequencing

TP53 exons 4–9 were sequenced using a next generation sequencing (NGS) platform using FFPE cores as previously described [38]. Criteria for reporting of variants were a minimum read depth of 500, an allelic ratio ≥ 5%, a base quality score ≥ 30, and a probability score ≥ 0.90 for single nucleotide changes or a quality score of ≥1000 for insertion/deletion events. Post-core hematoxylin and eosin stained slides were reviewed to ensure the areas of interest were targeted.

HPV in situ hybridization

In selected cases, HPV in situ hybridization was performed using Advanced Cell Diagnostics RNA-scope, as per manufacturer instructions.

Results

A total of 61 VSCC (48 conventional VSCC, 2 VSCC with sarcomatoid features, and 11 VCs) and 42 in situ lesions (30 dVIN, 9 deVIL, and 3 HSIL/uVIN) were included. Twenty-four cases were paired in situ and invasive carcinomas. Only three VSCC and three HSIL/uVIN were p16 positive, the remaining cases were p16 negative.

Major p53 IHC patterns observed

We surveyed all the p53 IHC stains with the TP53 mutation status known (Supplementary Table 1) and documented the p53 staining characteristics (Fig. 1). We were able to find six major patterns of staining, which is summarized in Table 1 and Fig. 2. While we expected many of these patterns based on previous experience, the basal overexpression pattern and mid-epithelial pattern were not known to us prior to this study. The IHC patterns in this six-pattern framework were consistent with TP53 mutation status in 58 of 61 (95%) VSCC and 39 of 42 (93%) in situ lesions.

HPV human papillomavirus, C IHC consistent with TP53 mutation status, DC discordant, DVIN differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, deVIL differentiated exophytic vulvar intraepithelial lesion, *DVIN morphologic appearance of deVIL but with sufficient nuclear atypia to upgrade to DVIN, UVIN high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion/usual vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, VSCC vulvar squamous cell carcinoma, VSCC(S) VSCC with sarcomatoid features, VC verrucous carcinoma, W weak, M moderate, S strong, H heterogeneous, N/A not applicable.

P16 (HPV)-negative lesions

Squamous cell carcinomas

Fifty-eight out of 61 VSCC were p16 negative. In 55 cases (95%) the IHC pattern was consistent with the TP53 mutation status and 3 (5%) were discordant.

Among the 55 concordant cases, 24 (44%) had a hotspot missense mutation(s) in the TP53 gene. All exhibited the basal or parabasal/diffuse pattern(s). Three VSCC that exhibited the parabasal/diffuse pattern had an 18-base pair in-frame deletion within TP53 exon 5. Four VSCC had absent staining, corresponding to two nonsense and two frameshift mutations. Two VSCC had cytoplasmic staining, which corresponded to one-frameshift mutation (deletion) and one-splice acceptor mutation. Twenty-four cases (8 VC, 15 VSCC, and 1 VSCC with sarcomatoid features) had scattered p53 staining and did not bear any TP53 mutations.

Three VSCC had a TP53 missense mutation, as well as one other mutation (one VSCC had an additional nonsense mutation, one had a frameshift mutation, and one had a splice site mutation). All three cases showed the basal or parabasal/diffuse patterns.

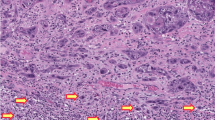

There were three discordant cases (Fig. 3). One discordant case (Case 23) had three TP53 missense mutations but the IHC staining pattern was scattered. p53 IHC was stained on two additional FFPE blocks; staining was scattered in the additional sections as well. The other discordant case (Case 57) had absent staining (and good internal control) but no TP53 mutation was detected. Similarly, Case 58 had predominantly absent staining but no TP53 nonsense, frameshift or deletion was detected. Case 58 did however, have a splice site mutation and on a second review, there was small area of tumor (~10%) that exhibited cytoplasmic staining.

a This VSCC had three different TP53 missense mutations but showed scattered p53 staining (Case 23). b VSCC had an absent pattern staining in the presence of positive staining in the background inflammatory cells but no TP53 mutation was detected (Case 57). VSCC shows predominantly absent staining (c) in the 90% of the tumor and cytoplasmic staining (d) in 10%. This tumor had a splice site mutation (Case 58). e, f Two dVIN lesions had TP53 missense mutations but exhibit scattered p53 staining (Cases 22 and 23).

There were 9 cases of VSCC where the distinction between the basal overexpression pattern and stronger wild-type pattern was difficult (Fig. 4).

a TP53 wild-type vulvar invasive squamous cell carcinoma (VSCC) showing stronger scattered staining (Case 53); b VSCC harboring a TP53 missense mutation, showing areas of prototypical basal overexpression and other areas c with weaker staining (Case 20); d A TP53 wild-type differentiated exophytic vulvar intraepithelial lesion (deVIL) showing stronger scattered staining (Case 61); e Differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN) harboring a TP53 missense mutation, with areas of basal overexpression and areas f with weaker staining (Case 20).

In situ squamous lesions

Of the 39 in situ squamous lesions, IHC in 36 cases (92%) was consistent with the TP53 mutation status and 3 cases (8%) were discordant.

In the 36 concordant cases, 18 had missense mutations and showed the basal or parabasal/diffuse pattern. Two had absent staining, corresponding to a nonsense and a frameshift mutations, 16 had scattered staining and no TP53 mutations.

In the three discordant cases, two dVIN had TP53 missense mutations but exhibited scattered staining. One dVIN had a frameshift mutation (duplication) and exhibited a basal overexpression pattern (Fig. 3).

Similar to the VSCC, there were 3 in-situ cases where distinction between the basal overexpression pattern and wild-type pattern with stronger staining was difficult (Fig. 4).

In the 24 paired in situ and invasive carcinomas, the IHC patterns was consistent with mutational status in 23. One pair (Case 24), as mentioned above, had a frameshift mutation in the dVIN but no mutations in the VSCC.

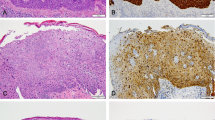

When scoring the in situ lesions, we found a few helpful features. We noted that the abnormal p53 patterns had a sharp interface with the background normal skin. We also noted that dVIN did not extend into the skin appendages, which is in contrast, a common finding for HSIL/uVIN (Fig. 5).

P16 (HPV)-positive lesions

In the three HSIL/uVIN and three VSCC that were p16 positive, all cases did not have any TP53 mutations and exhibited a distinct p53 IHC pattern (Fig. 6). In the HSIL/uVIN cases, p53 was completely negative in the basal layer and there was strong p53 staining in the parabasal layers. This mimicked an overexpression pattern, except the basal layer was entirely negative. In two HSIL/uVIN cases, p53 was completely negative in the basal layer, as well as the parabasal layers, with scattered cells showing strong p53 staining; this mimicked the appearance of an absent (null) pattern. We designated this pattern as the mid-epithelial (basal sparing) pattern. HPV in situ hybridization was performed revealing that the cells showing absence of p53 staining correlated with the cells harboring HPV.

a Case 75, TP53 wild-type HSIL/uVIN showing complete absence of p53 staining in the basal layer juxtaposed with strong p53 in the parabasal layers (mid-epithelial pattern). b In situ hybridization in Case 75 shows that the cells exhibiting absence of p53 staining correspond to those cells with HPV RNA. c Case 74, TP53 wild-type HSIL/uVIN had absence of staining in the basal layer as well as parabasal layers (again mid-epithelial pattern). d Case 77, TP53 wild-type HSIL/uVIN had clusters of cells showing complete absence of p53 juxtaposed to clusters of cells showing strong p53 staining. Staining of the basal layer is absent. e Case 76, TP53 wild-type VSCC exhibited little p53 expression and f was diffusely positive for HPV-ISH.

Discussion

In this study, we used TP53 mutation status to define p53 IHC patterns in vulvar squamous precursor lesions (HSIL/uVIN, dVIN, and deVIL) and VSCC. We found six major patterns of IHC staining. In this six-pattern framework, p53 IHC pattern was consistent with TP53 mutation status in 58/61 (95%) VSCC and 39/42 (93%) in situ lesions. However, some scenarios were challenging, such as strong scattered staining and weaker basal overexpression staining.

In the vast majority of cases, the type of TP53 alteration was consistent with the expected pattern of IHC staining. It is interesting to note that three VSCC with a TP53 missense mutation and an additional mutation (nonsense, frameshift, and splice site alteration) all exhibited overexpression patterns, despite the second mutation. One VSCC had an absent pattern but no mutations were detected. It is likely that a large deletion occurred that was not detected by our NGS panel, a known limitation of the NGS methodology. Also, mutations occurring outside of TP53 exons 4–9 would have been overlooked by the assay [39].

The greatest challenge in p53 IHC interpretation was distinguishing between the strong scattered and weaker basal-only staining patterns. Cases that exhibited stronger scattered staining tended to occur in well-differentiated VSCC and VCs. The basal overexpression pattern was one of the rarest patterns observed. Often the basal overexpression pattern was observed admixed with the easier to recognize, parabasal/diffuse pattern, where the basal overexpression pattern was seen in invasive squamous nests with significant central keratinization, leaving a peripheral rim of staining. This pattern has also been noted previously [32, 40]. In some cases, the basal overexpression pattern was seen adjacent to areas with weaker p53 staining. It is possible that some of these cases with heterogeneous staining may represent subclonal acquisition of TP53 mutations. However, as we did not sequence more than one area of the same tumor, we can only speculate. Suboptimal tissue fixation, typically in larger specimens, could also have contributed to weaker staining in some of the cases. Using biopsy material when available could be useful to facilitate the interpretation of the p53 IHC.

HPV-associated in situ (HSIL/uVIN) and VSCC had a unique and remarkable staining pattern, which we have referred to as the p53 mid-epithelial (basal sparing) pattern. The basal layers showed complete absence for p53 staining, juxtaposed to strong p53 staining in the parabasal layers. If a pathologist only notices the strong p53 staining in the parabasal layers and does not notice the absence of staining in the basal layer (which can be attenuated in VSCC), he or she may mistake this as an overexpression mutational p53 pattern. Recently, this particular staining pattern has been described by two groups prior to us [31, 41]. Both groups emphasized that this pattern should be acknowledged in order to prevent confusion with an abnormal p53 overexpression pattern. A helpful feature to note is that in the HPV-independent cases, cells show the strongest p53 staining in the basal layer and this staining gradually fades in the parabasal layers as the cells approach the epithelial surface. In the HPV-associated (mid-epithelial pattern) cases, cells show the reverse, strongest p53 staining near the epithelial surface, instead of the basal layer. In our study, we were also able to perform HPV in situ hybridization, which revealed that the cells showing complete absence of p53 staining, appeared to correlate to the same cells which were positive for HPV. This makes intuitive sense because the role of the HPV E6 oncoprotein is to bind and target p53 for degradation via complex formation with the cellular ubiquitin ligase E6-AP [42]. There were some cases where the mid-epithelial pattern showed the absence of staining the basal layer, as well as the parabasal layers; caution is also needed here because this feature can be easily confused with absent (null) staining. These cases showed diffuse involvement of squamous cells by HPV on in situ hybridization.

This study really emphasizes that scrutiny of the basal layer is the most important step in p53 IHC evaluation in squamous lesions of the vulva. Unlike the methodology used for interpretation of p53 in ovarian and endometrial carcinomas [43], proportion and intensity alone are insufficient. The basal layer is the most important layer as it is the germinative or proliferative layer, and acquisition of TP53 mutations in this layer would be subsequently passed onto the daughter cells as they mature toward the epithelial surface [44, 45]. The lack of abnormal p53 staining throughout the full thickness of the epithelium, is somewhat enigmatic. It may be a result of an early TP53 alteration where the mutant keratinocytes have not yet reached the upper layers, or the mutated p53 protein is degraded as a function of keratinocyte maturation [28]. The latter theory was first proposed by Pinto et al., who used laser capture microdissection to separately sequence the upper and lower layers of dVIN. They found that less TP53 mutations were evident in the upper layers, suggesting the p53 mutant protein was vulnerable to degradation in maturing keratinocytes [28].

This study allows us to find some helpful features for p53 interpretation. dVIN often exhibited a sharp interface with the adjacent normal skin as noted by previously by others [19, 46]. We also found that dVIN did not involve the hair follicles, unlike HSIL/uVIN, which commonly does. This finding has been noted once before by Mulvany et al. [27]. However, Yang and Hart did comment that some of their dVIN cases did involve the proximal follicular epithelium of the hair follicles (acrotrichium) [19]. Regardless, comparison of the p53 staining with adjacent normal skin or hair follicles can be informative.

There are several limitations of this study. We did not assess p53 staining patterns in vulvar squamous lesions in the differential diagnosis, such as lichen simplex chronicus and inflammatory dermatoses, and thus do not know if p53 staining in these lesions overlap with that seen in TP53 mutated dVIN. We also did not encounter any HSIL/uVIN or HPV-associated VSCC that concurrently harbored TP53 mutations and do not know what p53 staining pattern would be demonstrated. Since our cohort included only four HPV positive cases our conclusions on p53 IHC in this group of tumor is limited, but one must be careful verifying for staining in the basal layer since these cases may show strong mid-epithelial staining (with basal sparring), easily confused with the parabasal/diffuse overexpression mutant pattern, which retains strong basal cell staining. We further acknowledge that p53 staining will vary between laboratories. Some authors have noted no p53 staining in normal skin [27], but we have appreciated staining in all normal skin and used this as a reference for interpretation. We did not attempt to address nuanced questions (i.e., can the diagnosis of dVIN be made even if it lacks a TP53 mutation? Does the finding of a TP53 mutation automatically qualify a lesion dVIN even if it does not have all the histologic features?). Most importantly, we used TP53 mutation status to inform IHC pattern. Although our approach to of TP53 staining in vulvar lesion showed strong correlation with mutation status, the identification of certain interpretation challenges motivated validation efforts. A similar review of a larger cohort of vulvar skin lesions across three independent laboratories, where pathologists are blinded to TP53 status, is underway to answer if p53 IHC pattern can be used to accurately predict TP53 mutation.

This study, inspired by the work of Yang and Hart [19] published two decades ago, provides a blueprint for pathologists to more accurately interpret p53 IHC in vulvar in situ and invasive squamous lesions. This will allow us to accrue more reliable studies to explore the diagnostic and prognostic value of p53 in vulvar cancer.

References

Rogers LJ, Cuello MA. Cancer of the vulva. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;143:4–13.

Nooij LS, Brand FA, Gaarenstroom KN, Creutzberg CL, de Hullu JA, van Poelgeest MI. Risk factors and treatment for recurrent vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;106:1–13.

Toki T, Kurman RJ, Park JS, Kessis T, Daniel RW, Shah KV. Probable nonpapillomavirus etiology of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva in older women: a clinicopathologic study using in situ hybridization and polymerase chain reaction. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1991;10:107–25.

van der Avoort IA, Shirango H, Hoevenaars BM, Grefte JMM, de Hullu JA, de Wilde PCM, et al. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma is a multifactorial disease following two separate and independent pathways. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2006;25:22–9.

Hoang LN, Park KJ, Soslow RA, Murali R. Squamous precursor lesions of the vulva: current classification and diagnostic challenges. Pathology. 2016;48:291–302.

Nascimento AF, Granter SR, Cviko A, Yuan L, Hecht JL, Crum CP. Vulvar acanthosis with altered differentiation: a precursor to verrucous carcinoma? Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:638–43.

Watkins JC, Howitt BE, Horowitz NS, Ritterhouse LL, Dong F, MacConaill LE, et al. Differentiated exophytic vulvar intraepithelial lesions are genetically distinct from keratinizing squamous cell carcinomas and contain mutations in PIK3CA. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:448–58.

McAlpine JN, Leung SCY, Cheng A, Miller D, Talhouk A, Gilks CB, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV)-independent vulvar squamous cell carcinoma has a worse prognosis than HPV-associated disease: a retrospective cohort study. Histopathology. 2017;71:238–46.

Nooij LS, Ter Haar NT, Ruano D, Rakislova N, van Wezel T, Smit VTHBM, et al. Genomic characterization of vulvar (pre)cancers identifies distinct molecular subtypes with prognostic significance. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:6781–9.

Dong F, Kojiro S, Borger DR, Growdon WB, Oliva E. Squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: a subclassification of 97 cases by clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features (p16, p53, and EGFR). Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:1045–53.

Allo G, Yap ML, Cuartero J, Milosevic M, Ferguson S, Mackay H, et al. HPV-independent vulvar squamous cell carcinoma is associated with significantly worse prognosis compared with HPV-associated tumors. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1097/PGP.0000000000000620.

Hinten F, Molijn A, Eckhardt L, Massuger LFAG, Quint W, Bult P, et al. Vulvar cancer: two pathways with different localization and prognosis. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;149:310–7.

Scheistrøen M, Tropé C, Pettersen EO, Nesland JM. p53 protein expression in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Cancer. 1999;85:1133–8.

Hay CM, Lachance JA, Lucas FL, Smith KA, Jones MA. Biomarkers p16, human papillomavirus and p53 predict recurrence and survival in early stage squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20:252–6.

Gordinier ME, Steinhoff MM, Hogan JW, Peipert JF, Gajewski WH, Falkenberry SS, et al. S-Phase fraction, p53, and HER-2/neu status as predictors of nodal metastasis in early vulvar cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;67:200–2.

Kagie MJ, Kenter GG, Tollenaar RA, Hermans J, Trimbos JB, Fleuren GJ. p53 protein overexpression is common and independent of human papillomavirus infection in squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Cancer. 1997;80:1228–33.

Lerma E, Matias-Guiu X, Lee SJ, Prat J. Squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: study of ploidy, HPV, p53, and pRb. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1999;18:191–7.

Sand FL, Nielsen DMB, Frederiksen MH, Rasmussen CL, Kjaer SK. The prognostic value of p16 and p53 expression for survival after vulvar cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;152:208–17.

Yang B, Hart WR. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia of the simplex (differentiated) type: a clinicopathologic study including analysis of HPV and p53 expression. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:429–41.

Potten CS. The development of epithelial stem cell concepts. In: Lanza R, Atala A, editors. Handbook of stem cells. 2nd ed. San Diego, CA: Elsevier; 2013. p. 451–1.

Liegl B, Regauer S. p53 immunostaining in lichen sclerosus is related to ischaemic stress and is not a marker of differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (d-VIN). Histopathology. 2006;48:268–74.

Hoevenaars BM, van der Avoort IA, de Wilde PCM, Massuger LFAG, Melchers WJG, de Hullu JA, et al. A panel of p16(INK4A), MIB1 and p53 proteins can distinguish between the 2 pathways leading to vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2767–73.

Dasgupta S, Ewing-Graham PC, van Kemenade FJ, van Doorn HC, Noordhoek Hegt V, Koljenović S. Differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN): the most helpful histological features and the utility of cytokeratins 13 and 17. Virchows Arch. 2018;473:739–47.

Al-Ghamdi A, Freedman D, Miller D, Poh C, Rosin M, Zhang L, et al. Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma in young women: a clinicopathologic study of 21 cases. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;84:94–101.

Ordi J, Alejo M, Fusté V, Lloveras B, Del Pino M, Alonso I, et al. HPV-negative vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) with basaloid histologic pattern: an unrecognized variant of simplex (differentiated) VIN. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1659–65.

Santos M, Montagut C, Mellado B, García A, Ramón y Cajal S, Cardesa A, et al. Immunohistochemical staining for p16 and p53 in premalignant and malignant epithelial lesions of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2004;23:206–14.

Mulvany NJ, Allen DG. Differentiated intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2008;27:125–35.

Pinto AP, Miron A, Yassin Y, Monte N, Woo TYC, Mehra KK, et al. Differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia contains Tp53 mutations and is genetically linked to vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:404–12.

van der Avoort IA, van de Nieuwenhof HP, Otte-Höller I, Nirmala E, Bulten J. Massuger LFAG, et al. High levels of p53 expression correlate with DNA aneuploidy in (pre)malignancies of the vulva. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:1475–85.

Bigby SM, Eva LJ, Fong KL, Jones RW. The natural history of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, differentiated type: evidence for progression and diagnostic challenges. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2016;35:574–84.

Watkins JC, Yang E, Crum CP, Herfs M, Gheit T, Tommasino M, et al. Classic vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia with superimposed lichen simplex chronicus: a unique variant mimicking differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2019;38:175–82.

Rolfe KJ, MacLean AB, Crow JC, Benjamin E, Reid WMN, Perrett CW. TP53 mutations in vulval lichen sclerosus adjacent to squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:2249–53.

Choschzick M, Hantaredja W, Tennstedt P, Gieseking F, Wölber L, Simon R. Role of TP53 mutations in vulvar carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2011;30:497–504.

Kashofer K, Regauer S. Analysis of full coding sequence of the TP53 gene in invasive vulvar cancers: Implications for therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;146:314–8.

Kim YT, Thomas NF, Kessis TD, Wilkinson EJ, Hedrick L, Cho KR. p53 mutations and clonality in vulvar carcinomas and squamous hyperplasias: evidence suggesting that squamous hyperplasias do not serve as direct precursors of human papillomavirus-negative vulvar carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:389–95.

Vanin K, Scurry J, Thorne H, Yuen K, Ramsay RG. Overexpression of wild-type p53 in lichen sclerosus adjacent to human papillomavirus-negative vulvar cancer. J Investig Dermatol. 2002;119:1027–33.

Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Cox JT, Heller DS, Henry MR, Luff RD, et al. The lower anogenital squamous terminology standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012;16:205–42.

Prentice LM, Miller RR, Knaggs J, Mazloomian A, Aguirre Hernandez R, Franchini P, et al. Formalin fixation increases deamination mutation signature but should not lead to false positive mutations in clinical practice. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0196434.

Cho Y, Gorina S, Jeffrey PD, Pavletich NP. Crystal structure of a p53 tumor suppressor-DNA complex: understanding tumorigenic mutations. Science. 1994;265:346–55.

Wellenhofer A, Brustmann H. Expression of human telomerase reverse transcriptase in vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical study with survivin and p53. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:1359–65.

Jeffreys M, Jeffus SK, Herfs M, Quick CM. Accentuated p53 staining in usual type vulvar dysplasia-A potential diagnostic pitfall. Pathol Res Pract. 2018;214:76–9.

Martinez-Zapien D, Ruiz FX, Poirson J, Mitschler A, Ramirez J, Forster A, et al. Structure of the E6/E6AP/p53 complex required for HPV-mediated degradation of p53. Nature. 2016;529:541–5.

Köbel M, Ronnett BM, Singh N, Soslow RA, Gilks CB, McCluggage WG. Interpretation of P53 immunohistochemistry in endometrial carcinomas: toward increased reproducibility. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2019;38:S123–31.

Ren ZP, Hedrum A, Pontén F, Nistér M, Ahmadian A, Lundeberg J, et al. Human epidermal cancer and accompanying precursors have identical p53 mutations different from p53 mutations in adjacent areas of clonally expanded non-neoplastic keratinocytes. Oncogene. 1996;12:765–73.

Ren ZP, Pontén F, Nistér M, Pontén J. Two distinct p53 immunohistochemical patterns in human squamous-cell skin cancer, precursors and normal epidermis. Int J Cancer. 1996;69:174–9.

Singh N, Leen SL, Han G, Faruqi A, Kokka F, Rosenthal A, et al. Expanding the morphologic spectrum of differentiated VIN (dVIN) through detailed mapping of cases with p53 loss. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:52–60.

Acknowledgements

This study has supported by the Carraresi Foundation, Sumiko Kobayashi Marks Memorial Fund, OVCare and the UBC & VGH Hospital Foundations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tessier-Cloutier, B., Kortekaas, K.E., Thompson, E. et al. Major p53 immunohistochemical patterns in in situ and invasive squamous cell carcinomas of the vulva and correlation with TP53 mutation status. Mod Pathol 33, 1595–1605 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-020-0524-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-020-0524-1

This article is cited by

-

Role of human papillomavirus status in the classification, diagnosis, and prognosis of malignant cervical epithelial tumors and precursor lesions

Die Pathologie (2026)

-

A novel tumor budding and cell nest size-based grading system outperforms conventional methods in vulvar squamous cell carcinoma

Virchows Archiv (2025)

-

HPV-independent squamous sell carcinoma of cervix: a clinicopathological, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis of six cases

Virchows Archiv (2025)

-

Immunoreactivity of LMO7 and other molecular markers as potential prognostic factors in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma

BMC Oral Health (2024)

-

Simultaneous p53 and p16 Immunostaining for Molecular Subclassification of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas

Head and Neck Pathology (2024)