Abstract

With the increasing practice of gender-affirming mastectomy as a therapeutic procedure in the setting of gender dysphoria, there has come a profusion of literature on the pathologic findings within these specimens. Findings reported in over 1500 patients have not included either prostatic metaplasia or pilar metaplasia of breast epithelium. We encountered both of these findings in the course of routine surgical pathology practice and therefore aimed to analyze these index cases together with a retrospective cohort to determine the prevalence, anatomic distribution, pathologic features, and associated clinical findings of prostatic metaplasia and pilar metaplasia in the setting of gender-affirming mastectomy. In addition to the 2 index cases, 20 additional archival gender-affirming mastectomy specimens were studied. Before mastectomies, all but 1 patient received testosterone cypionate, 6/22 patients received norethindrone, and 21/22 practiced breast binding. Prostatic metaplasia, characterized by glandular proliferation along the basal layer of epithelium in breast ducts, and in one case, within lobules, was seen in 18/22 specimens; 4/22 showed pilar metaplasia, consisting of hair shafts located within breast ducts, associated with squamoid metaplasia resembling hair matriceal differentiation. By immunohistochemistry, prostatic metaplasia was positive for PSA in 16/20 cases and positive for NKX3.1 in 15/20 cases. Forty-three reduction mammoplasty control cases showed no pilar metaplasia and no definite prostatic metaplasia, with no PSA and NKX3.1 staining observed. We demonstrate that prostatic metaplasia and pilar metaplasia are strikingly common findings in specimens from female-assigned-at-birth transgender patients undergoing gender-affirming mastectomy. Awareness of these novel entities in the breast is important, to distinguish them from other breast epithelial proliferations and to facilitate accrual of follow-up data for better understanding their natural history.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mastectomy as a means of gender affirmation has become an increasingly common practice in the U.S. and elsewhere [1, 2]. Paralleling this, publications describing the pathologic features of these specimens have emerged. Reports from five countries, detailing over 1500 patients undergoing gender-affirming mastectomy, describe stromal fibrosis, involutional changes/lobular atrophy, reduced number of terminal duct lobular units, duct ectasia, apocrine metaplasia, micro-calcifications, fibrocystic changes, lactational change, gynecomastoid changes, fibroadenomatoid change, sclerosing adenosis, columnar cell change, pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia, benign vascular lesions, intraductal papillomas, atypical lesions, in situ carcinomas, and invasive breast cancer [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. One study identified prostate-specific antigen (PSA) staining in 1 of 23 patients; the staining was confined to “atrophic lobular epithelial cells” without any histologic glandular differentiation or ductal involvement described [11]. Benign findings have been ascribed to androgen-induced changes in breast composition, altered hormone ratios between exogenous testosterone and endogenous estrogen, and increased lean body mass caused by sex hormone therapy. Atypical or malignant lesions have been attributed to peripheral conversion of androgens to estrogens and underlying genetic predisposition. In mastectomy specimens from transgender individuals, we encountered two features not previously described: prostatic and pilar metaplasia of breast ducts. We conducted the study herein to analyze these index cases of interest and to determine, via retrospective study, the prevalence, distribution, pathologic features, and associated clinical findings of prostatic and pilar metaplasia within breast epithelium in the setting of gender-affirming mastectomy.

Materials and methods

Case selection

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Boston Children’s Hospital. After encountering the two index cases, a retrospective study of archival material was conducted. Twenty consecutive bilateral mastectomy specimens resected for the indication of gender dysphoria between July and September 2020 were identified. All surgical operations occurred between July and September 2020. Forty-three consecutive bilateral reduction mammoplasty specimens from the same time period were identified as controls.

Histologic examination

During the study period, routine prosection for mastectomy specimens in the setting of gender dysphoria included the sampling of two blocks of tissue per breast, including 3 sections of breast and 1 section of periareolar skin. Additional blocks were submitted at the pathologist’s discretion. Histologic sampling for the reduction mammoplasty specimens included 2 blocks per breast (4 blocks per patient) in all cases except for 3 patients who had extra blocks sampled due to fibroadenoma (n = 2, including 1 patient with a focus equivocal for prostatic metaplasia identified) and due to a family history of breast cancer as well as atypical epithelial proliferation observed in the initial 4-block sample (n = 1, a patient with a focus equivocal for prostatic metaplasia identified). All original hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections were examined via light microscopy.

Immunohistochemistry

All cases in which there was definitive or equivocal evidence of prostatic metaplasia on routine histology were stained for both PSA (polyclonal rabbit at a dilution of 1:7500, DAKO, Carpinteria, CA, USA) and NKX3.1 (polyclonal rabbit at a dilution of 1:1000, Athena ES, Baltimore, MD, USA). Staining for these antibodies was completed using a Ventana Medical Systems (Tucson, AZ, USA) platform. A subset of transgender breast specimens showing prostatic metaplasia (patients #2, 5, 7, 10, and 13) as well as two transgender vaginectomy specimens showing prostatic metaplasia were stained with E-cadherin (clone 24E10 at a dilution of 1:200, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), using the Leica Biosystems (Buffalo Grove, IL) Refine Detection Kit on the Leica Bond III automated staining platform.

Medical record review

Clinical data were ascertained via a review of the electronic medical record in all cases. Data elements included age, underlying medical conditions, breast binding practices, and medical therapy. For the purposes of this study, “duration of androgen therapy” was defined as the period of continuous androgen therapy occurring before mastectomy.

Results

Index case #1

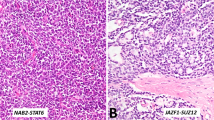

This 16-year-old transgender male was assigned female at birth. At the time of mastectomy, he had received 12 months of masculinizing androgen therapy (testosterone cypionate). He was on a multitherapy regimen for severe acne. Clinical history also included a repaired tetralogy of Fallot and psoriatic arthritis, for which he was on long-term immunosuppressive therapy. He reported the use of a pressure binder on his chest for 12 h a day, which caused discomfort. The patient underwent bilateral simple (complete) mastectomies with full-thickness grafts for nipple-areolar complex reconstruction. Gross examination of the breast tissue was unremarkable; however, attached skin showed a 1.1 cm area of dermal discoloration. Sections from different areas, including areas adjacent to the nipple and the area of dermal discoloration, were submitted for histologic examination. Microscopically, the breast showed diffuse lobular atrophy and prominent stroma. A deep dermal abscess without polarizable material was seen at the area of gross discoloration. Breast ducts showed an intra-epithelial proliferation of tubular glands resembling prostatic metaplasia and located along the periphery of the breast duct. The cells were cuboidal with uniform round nuclei, small nucleoli, and foamy clear to palely eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 1A, B). In some areas, the glands appeared as outpouchings of the breast duct which invaginated into the breast stroma, such that a fortuitous plane of the section could give the impression of discontinuity with the adjacent breast duct. Occasional eosinophilic secretions were present within the glands. Immunohistochemical staining for PSA showed moderate to strong staining along the luminal cytoplasmic border of the glandular proliferation (Fig. 1C). There was patchy staining for NKX3.1 in the basal glandular cells, ranging from weak to moderate, consistent with prostatic differentiation (Fig. 1D). No cellular atypia or mitotic activity and no pilar metaplasia were identified. Prostatic metaplasia was present in 3 of 4 blocks submitted.

Prostatic glands are scattered along the basal surface of the duct, above myoepithelial cells (A, B), sometimes associated with invagination into the stroma. Glands have cuboidal cells with foamy, clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm and nucleoli (C). D Positive immunohistochemical staining for PSA and E NKX3.1 (patchy).

Index Case #2

This 17-year-old transgender male, who was assigned female at birth, had been receiving testosterone cypionate intramuscularly for 19 months prior to mastectomy and used a pressure binder 6–9 h each day to disguise the feminine appearance of his breasts. Medical history included asthma and anorexia nervosa in remission. Gross examination of nipple-sparing mastectomy specimens revealed no abnormality. Microscopically, periareolar breast ducts contained hair shafts (Fig. 2). Mild to moderate chronic inflammation surrounded involved ducts. The ductular epithelium showed focal squamous metaplasia resembling hair follicle differentiation. In a few areas, the hair shafts filled and distended the ducts. In others, there were only single hair shafts with no ductular distention. Prostatic metaplasia was also seen. Pilar metaplasia was present in 6 of 24 blocks submitted, and prostatic metaplasia was present in all 24 blocks.

A Single hair shaft in a duct with squamous metaplasia and periductal chronic inflammation. B Another isolated intraductal hair shaft. C Multiple hair shafts distending lumen of the duct. Changes at the lower-left portion of the duct resembling prostatic metaplasia. D Another example of multiple hair shafts within a distended duct lumen with a single multinucleate giant cell. E High power of the duct with multiple hair shafts; ductal epithelial cells showing squamoid features, resembling matrix differentiation. F Fontana-Masson stain, delineating melanin in hair shafts.

Retrospective study

Clinical features

Patients with gender dysphoria (n = 20)

The clinical features of 20 additional patients with gender dysphoria are summarized in Table 1. All patients in this retrospective study identified as transmasculine and had been assigned female sex at birth. Ages at mastectomy ranged from 15-29 years (mean: 19.3 years; median: 18 years). None had a history of underlying metabolic/endocrine abnormalities or known chromosomal/genetic variants that could potentially contribute to their gender dysphoria. Eighteen of the twenty patients had received androgen therapy in the form of testosterone cypionate prior to mastectomy. The treatment duration for those 18 patients ranged from 1-53 months (mean: 21.7 months; median: 19 months). One patient (patient #7) had received 3 months of testosterone therapy prior to the diagnosis of an ovarian serous borderline tumor, reported elsewhere [12]; testosterone was discontinued for several months and then restarted for the 12 consecutive months prior to mastectomy. Another patient (patient #20) had 1 month of testosterone therapy a year prior to mastectomy, but then discontinued it because of side effects. Hormone therapy was resumed 1 month prior to mastectomy. Two patients had no androgen therapy prior to mastectomy. Six patients had been prescribed systemic hormonal therapy (norethindrone) for menstruation cessation. All but 1 patient reported the use of a pressure binder for concealing their breasts. For all patients, this was their first gender-affirming surgical procedure. All patients underwent bilateral simple mastectomy; thirteen patients underwent complete excision (including the nipple-areola complex) and 7 underwent nipple-sparing procedures.

Patients with macromastia (n = 43)

The control cohort included patients ranging in age from 17 to 24 years (median and mean, 19 years). None reported any history of androgen therapy. All underwent bilateral reduction mammoplasty in the setting of macromastia.

Histopathology

Patients with gender dysphoria (n = 20)

None of the specimens showed grossly discernable lesions. Histopathological and immunohistochemical findings are summarized in Table 2. Prostatic metaplasia was identified in 16 of 20 retrospectively examined cases. Microscopically, it appeared similar to the 2 index cases. There were glands located in the basal aspect of the large ducts leading up to the nipple and in smaller outpouchings from ducts distant from the nipple. In all instances, the glands were superficial to the myoepithelial cells. The glands were composed of a single layer of cuboidal cells that were slightly larger than the surrounding ductular epithelium. They had more abundant predominantly eosinophilic cytoplasm, with occasional vacuolization and foamy change. Eosinophilic secretions were seen in some cases. The centrally-placed nuclei were round with smooth contours, and small nucleoli were usually evident. No atypia or mitotic activity was seen. The anatomic extent ranged from focal on one side only to widely evident in bilateral breasts. The specimen from 1 patient (patient #19) showed microcalcifications in association with prostatic metaplasia (Fig. 3B). In another case (patient #20), the prostatic metaplasia was located at the periphery of a 0.8 cm fibroadenoma.

A Large duct with a peripheral/basal proliferation of glands composed of cells with round nuclei and more abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm than surrounding epithelium (patient #3). B Cells with more foamy, clear cytoplasm, and apical cytoplasmic “snouts”; intraluminal microcalcifications present (patient #19).

Three of the 20 consecutive retrospectively reviewed cases had hair shafts within breast ducts (Fig. 4). Two of these cases had a single hair shaft within an otherwise normal-appearing breast duct in the periareolar region. The third case had a breast duct with squamoid change, periductular chronic inflammation, and a single hair within a breast duct distant from the areola. One of 20 cases showed dilated periareolar breast ducts distended by acellular keratinaceous debris without hair shafts.

Two cases had gynecomastoid change, displaying the classic three-layered epithelium as previously described [13]. Other findings included prominent stroma, lobular atrophy, duct ectasia, and apocrine metaplasia. No atypical proliferation or malignancy was identified in any specimen.

Patients with macromastia (n = 43)

Pilar metaplasia was not identified in any patient. Areas suspicious for prostatic metaplasia were present in 2 patients. One was a 17-year-old with a localized area of pale prostate-like cells at the basal aspect of a duct. The other was a 19-year-old with epithelial changes that had been interpreted as atypical ductal and lobular hyperplasia as well as flat epithelial atypia. Areas of flat epithelial atypia bore a strong histologic resemblance to the prostatic metaplasia observed in the transgender cohort.

Immunohistochemical results

Patients with gender dysphoria (n = 20)

Immunohistochemical findings are summarized in Table 2 and depicted in Fig. 5. Nineteen of the 20 retrospective cases were stained. PSA was positive in 15 of 19 retrospective cases and in 16 of 20 overall cases (including index case 1). In all cases with PSA staining, the stain was localized to the foci of prostatic metaplasia observed on H&E-stained sections. The staining was generally intermediate to strong and confluent in the glandular epithelium and secretions; however, a proportion of cases (7/15) showed patchy, weak staining, highlighting only a single or a few cells within an area of prostatic metaplasia. One case showed moderate to strong staining in both the ductular and lobular foci.

NKX3.1 was positive in 14 of 19 retrospective cases and in 15 of 20 overall cases (including index case 1) The staining was nuclear and localized to the foci of prostatic metaplasia; it was patchy in all cases and ranged from weak to strong.

Of note, one case that was negative for PSA was positive for NKX3.1, and another case that was negative for NKX3.1 was positive for PSA. The two cases with equivocal prostatic metaplasia on H&E (evident as focal cellular enlargement of the basal portion of duct epithelium without gland formation) showed negative staining for both PSA and NKX3.1. One case without any histologic evidence of prostatic metaplasia on H&E also showed negative staining for both PSA and NKX3.1. There appeared to be no relationship between the intensity or pattern of staining and the duration of androgen therapy.

E-cadherin staining showed intact membranous labeling within prostatic metaplasia in 5/5 transgender breast and in 2/2 transgender vaginal specimens.

Patients with macromastia (n = 43)

Immunohistochemical staining for PSA and NKX3.1 was negative in both reduction mammoplasty specimens that showed areas histologically suspicious for prostatic metaplasia.

Discussion

This study characterizes two novel findings in the breast ductular epithelium of patients undergoing mastectomy for gender reassignment: prostatic metaplasia and pilar metaplasia. To our knowledge, neither finding has been previously described in this setting. Pilar metaplasia of breast ducts, in particular, has not been described histologically, in any setting. Both prostatic and pilar metaplasia are relatively common in this clinical setting, occurring in 80% and 15%, respectively, of randomly selected mastectomy specimens from transgender patients in our study, with an average of 2.4 slides submitted per breast.

Mastectomy specimens from transgender individuals have been extensively studied in recent years, with publications of histologic findings from 1992 to 2021, across five countries. A total of 1555 patients were included in these studies, with sampling ranging from 2 blocks to 29.5 blocks per case. All studies included at least a subset of patients on androgen therapy. Some studies focused on the overall histologic composition of the breast. Grynberg and colleagues reported that a decrease in glandular tissue with stromal fibrosis was common [5]. Others, such as van Renterghem and colleagues, have also shown that a high proportion of patients have a > 75% fibrous tissue composition to their breasts [7]. Lobular atrophy and predominately fibrous stroma were seen in 73% and 45% in a study by Torous et al. [8]. Similar findings were seen by Baker and colleagues, who found that a majority of subjects on testosterone therapy for at least 12 months had predominately fibrous stroma and moderate lobular atrophy [10]. Benign breast disease, particularly fibrocystic change and gynecomastoid changes, are relatively common in transgender breast specimens. The frequency of fibrocystic change ranged from 34 to 39.4% in various studies [4,5,6]. Gynecomastoid change has been described in 3 studies, occurring at a frequency between 39.7 and 41% [6, 8, 10]. Duct ectasia was seen almost universally (96–100%) in 2 studies [8, 10]. Microcalcifications were noted to be increased in transgender patients on androgen therapy in another [3]. One report described PSA staining in 1 of 23 patients, confined to “atrophic lobular epithelial cells” not further described histologically; this study did not find any metaplastic cells or PSA staining within breast ducts [11]. No significant differences in immunohistochemical staining patterns of estrogen or progesterone receptor have been observed [3]. The staining pattern of gynecomastoid change was similar to that seen in male breasts [6]. The prevalence of clinically significant breast lesions, including atypical lesions (atypical hyperplasia, flat epithelial atypia, atypical lobular hyperplasia) and carcinoma (both in situ and invasive), ranged in frequency from 0 to 4%. In studies where they were directly compared, patients on androgen therapy did not show any difference in the rate of substantial pathologic findings vs. those who did not receive androgen therapy and actually tended to have a lower rate of these findings.

Our study showed that prostatic metaplasia in the breasts of transgender individuals is common, identified in 80% of mastectomy specimens despite limited sampling (mean, 2.4 paraffin blocks per breast). It is characterized histologically by prostate-like cells arranged in variably well-formed glands along the basal aspect of the epithelium in ducts and, less frequently, lobules. It is characterized immunohistochemically by PSA and NKX3.1 staining in a majority of cases. No previous descriptions of prostatic metaplasia occurring within the breast ducts, to our knowledge, exist. There may be a few reasons for this. First, our patient cohort was younger than in previous studies. It may be that mammary epithelium is more plastic in younger adults and is, therefore, more responsive to androgens. Second, our institutional surgeons do not discontinue androgen therapy prior to mastectomy, guided by a systematic review that showed no increased morbidity when cross-sex hormone therapy was continued in the perioperative period [14]. Third, it is possible that in the past, these lesions were overlooked because of their patchy nature or their rather inconspicuous appearance, or perhaps misinterpreted as low-grade epithelial proliferations. Of note, the high proportion of patients on testosterone therapy in this cohort (20/22, 91%) is similar to rates observed in other studies.

The prostatic metaplasia observed in mastectomy specimens from transgender patients resembles the prostatic metaplasia described in the vagina and cervix of patients undergoing vaginectomy and hysterectomy in the setting of exogenous or endogenous androgen exposure [15, 16]. Both feature discontinuously distributed tubular glands occurring along the basal layer of epithelium and sometimes invaginating into the surrounding stroma. In both breast and cervicovaginal locations, the cells comprising those glands are cuboidal to columnar and have abundant clear-to-eosinophilic cytoplasm surrounding a centrally placed, round nucleus. Similar to the breast findings observed in our cohort, prostatic metaplasia occurring in the vagina and cervix also shows positive immunostaining for NKX3.1 and PSA in the majority of cases.

In the breast, atypical epithelial proliferations including atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) and flat epithelial atypia (FEA) enters into the histologic differential diagnosis of prostatic metaplasia. ALH is characterized by mild distention or distortion of ducts and lobules by uniform dyshesive cells with eosinophilic to occasionally pale cytoplasm and low-grade nuclear atypia. Occasionally, ALH can exhibit pagetoid spread whereby the cells spread and distend the space between luminal epithelial cells and myoepithelial cells, forming small outpouchings around ducts, that bears a strong resemblance to prostatic metaplasia. The cells in ALH, however, are more dyshesive, with less frequent and less prominent nucleoli, more hyperchromatic nuclei, more uniform involvement of a duct, and more prominent ductal outpouching/distention by multiple layers of cells. Retained E-cadherin staining in prostatic metaplasia may be an additional way to distinguish prostatic metaplasia since the pagetoid spread of ALH is most often characterized by a loss of E-cadherin staining. FEA is characterized by distended ducts lined by one or more layers of columnar cells with low-grade nuclear atypia. Similar to prostatic metaplasia, small nucleoli can be seen and the affected ducts often contain eosinophilic secretions. However, FEA, as the name suggests, shows flat rows of cells without gland formation. Furthermore, the involved cells have features of low-grade atypia such as an increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio and hyperchromasia, which were not observed in prostatic metaplasia.

Given the highly restricted expression of NKX3.1 in the human body, the positive staining observed in our study helps to support the interpretation of prostatic differentiation in the affected breast ducts. NKX3.1 is an androgen-regulated gene involved in cellular differentiation. Its expression in normal tissue is limited to prostatic epithelial cells and seminiferous tubules [17]. Its expression in malignant tissue is also quite restricted; it is seen in a majority of primary and metastatic prostate cancer as well as in low levels in a subset of metastatic lobular breast carcinoma and in a small proportion of metastatic infiltrating ductal carcinoma [17]. No NKX3.1 expression in benign breast tissue from either males or females has been described. On the other hand, PSA expression has been observed rarely in benign epithelial cells of the female breast in the setting of oral contraceptive use [18]. It has also been described within the ductal epithelium of male breasts with gynecomastia [19] and confined to “epithelium of moderately involuted lobules” in one gender-affirming mastectomy specimen [11].

Evidence from animal and human studies implicates androgens as a cause of prostatic metaplasia in the female lower genital tract [15, 16, 20, 21]. Of note, the duration of androgen therapy in our study is less than that in previously described human androgen-associated metaplasia, perhaps because chest-contouring is typically the first stage of gender reassignment surgery. Notably, 1 patient (patient #20) after only 1 month of therapy still showed histologic evidence of prostatic metaplasia, suggesting that this effect does not require long-term androgen therapy.

Our finding of pilar differentiation in mammary ductal epithelium appears to be novel, not to our knowledge previously described or illustrated pathologically. We find no mention of it in textbooks of breast pathology, nor in a PubMed search of medical literature. It is characterized histologically by the presence of one or more fine hairs within breast duct lumens, sometimes lined by squamoid cells resembling matriceal differentiation. In our series, it was identified in 15% of mastectomy specimens despite limited sampling (average, 2.5 paraffin blocks per breast).

Pilar metaplasia of breast ducts is distinct from other hair-bearing and squamoid lesions that can involve the breast and its dermal coverings. The squamoid changes, dilated ducts with keratinous debris, and associated inflammation we observed somewhat resemble squamous metaplasia of lactiferous ducts (SMOLD) [22]. Pilar metaplasia of the breast also shares some histologic characteristics with the dermal lesions vellus hair cyst and trichofolliculoma, in that these entities show epithelium-lined spaces filled with keratinous debris with or without hair shafts; however, both are dermal lesions with characteristic clinical findings, and they are not expected to occur as clinically occult lesions in the deeper breast parenchyma.

Hair growth within the lactiferous ducts is a distinctive clinical finding which, to our knowledge, is confined in humans to the setting of cerebello-oculo-facio-genital (COFG) syndrome, a recently described disorder characterized by heterozygous loss-of-function variants in MAB21L1. Females and males with this condition can show, among other features, tufts of vellus or terminal hair extruding from the lactiferous ducts in the setting of underdeveloped or absent nipples with no discernable areolae [23, 24]. The Mab21l2 protein product of the gene is involved in diverse pathways, and the precise mechanism of “hairy nipple” development is unclear. Histologic features of the breast in COFG syndrome have not been reported. In mouse models, overexpression of Noggin (a BMP antagonist) and loss of Gli3 have been associated with a hairy nipple phenotype [25, 26].

Given the high rate of testosterone therapy among the patients in our study, one might speculate that pilar metaplasia could be influenced by androgens, which are known for example to contribute to the development of pubertal pubic hair [27]. Notably, however, in our series, we found that one of the four patients with pilar metaplasia of breast ducts had not been taking exogenous androgens, and therefore other contributing factors besides androgens should be considered.

We found that breast-binding was practiced by a substantial proportion (95%) of patients in our transgender cohort in the time preceding their mastectomy procedures. This raises the question of whether breast-binding may contribute to prostatic metaplasia and/or pilar metaplasia, perhaps by altering mechanical forces, local temperature, vascular flow, or other conditions in a manner that potentiates metaplasia. Transmitted forces affecting the cellular cytoskeleton, in particular, can cause a cascade of signals that alter the nuclear shape, contractility, signal transduction, and growth factor release [28, 29]. In the breast, epithelial cells have been found to only differentiate into tubules in culture when they are surrounded by the proper density of collagen matrix, in a study that highlights the importance of the surrounding environment in epithelial development [30]. Furthermore, a negative-pressure bra has been shown to cause breast hypertrophy in women [31], and mechanical factors such as nipple piercing and inverted nipples have been linked to SMOLD [32]. It could also be hypothesized that pressure binding may force hair shafts around the nipple-areolar complex inward into the breast ducts; however, in a few sections of index patient #2 and inpatient #13, the hair shafts were seen in sites distant from the nipple and overlying skin; a theory of simple displacement also does not explain the matriceal differentiation seen. Thus, we believe that “pilar differentiation” is an apt term that encompasses the histogenesis of the finding; even though matrix may not be discernible in association with every ectopic hair shaft in these surgical pathology specimens, we believe that it may simply require fortuitous sectioning to capture it in histologic sections.

We also considered whether systemic hormone therapy other than testosterone cypionate may have contributed to the histologic findings. Twenty-seven percent of all patients in this study were on the progestin norethindrone, for menses suppression. It has been shown that breast tissue from patients receiving progestin-containing oral contraceptives can be immunoreactive for PSA. Norethindrone can also induce PSA expression in breast cancer [33]. Although norethindrone may indeed have a role in prostatic and/or pilar metaplasia in the breast, it does not seem to account for all cases, since 14 of the 18 cases of prostatic metaplasia occurred in patients without norethindrone therapy. Also, none of the 4 patients with pilar metaplasia in our study were on norethindrone. It is important to note that a variety of hormone regimens are commonly used for menstrual suppression in transmasculine patients, including those on testosterone. A recent study of breakthrough bleeding in transmasculine patients on testosterone found that more than half had been on overlapping menstrual suppression for at least some time [34].

The clinical significance of both prostatic metaplasia and pilar metaplasia of the breast remains to be determined, but because of potential significance, it remains an important aspect to consider for transgender patients who elect to retain their breasts as well as those with residual breast tissue post-mastectomy. Prostatic metaplasia could be expected to recapitulate prostatic epithelial secretory function to at least some extent, expressing innumerable proteins and factors with antibacterial, antioxidant, coagulant, and other functions [35], with potential clinical effects both in the breast and systemically. Subcutaneous hair is known to be an irritant in pilonidal disease and other conditions. Our finding of periductal chronic inflammation at affected sites in 2 of 3 cases suggests that local irritation may likewise be a sequela of pilar metaplasia. That mastodynia was present in 95% of patients in this series is noteworthy, but we have no specific evidence as to whether the metaplasia caused or contributed to mastodynia.

The presence of microcalcifications associated with prostatic metaplasia in one patient is worth highlighting since calcifications of this nature could produce radiologic findings that might prompt biopsy or other clinical intervention. Another consideration is that both prostatic and pilar differentiation have been observed in a subset of breast carcinomas [36, 37], and whether either of the metaplasia types we observed could be a precursor to cancer is unexplored. Although no patients in our study had concurrent cancerous lesions, the small sample size and lack of follow-up preclude drawing any conclusions about the risk of malignancy. Reports of breast cancer in transgender individuals are rare. Prostatic metaplasia and pilar metaplasia are histologically bland, and we believe that they are currently best interpreted as benign conditions; however, it remains unknown whether there could be long-term malignant potential.

To summarize, we conclude that prostatic metaplasia and pilar metaplasia of breast ducts are distinct clinicopathologic entities, identifiable in a substantial proportion of mastectomy specimens resected in gender transitioning. Potential contributing factors may include testosterone cypionate, other systemic hormonal therapy, breast binding, or a combination thereof. Our findings add to the growing body of pathology knowledge about transgender medical conditions, with the potential to help advance care in this emerging field. Awareness of these processes will aid in their recognition and distinction from other breast epithelial proliferation. Future work is needed to identify potential clinical sequelae and to understand biologic pathways responsible for this apparently unique differentiation pathway in the breast epithelium.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Cuccolo, N. G., Kang, C. O., Boskey, E. R., Ibrahim, A. M. S., Blankensteijn, L. L. & Taghinia, A. et al. Mastectomy in transgender and cisgender patients: a comparative analysis of epidemiology and postoperative outcomes. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open. 7, e2316 (2019).

Lane, M., Ives, G. C., Sluiter, E. C., Waljee, J. F., Yao, T. & Hu, H. M. et al. Trends in gender-affirming surgery in insured patients in the united states. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open. 6, e1738 (2018).

Burgess, H. E. & Shousha, S. An immunohistochemical study of the long-term effects of androgen administration on female-to-male transsexual breast: A comparison with normal female breast and male breast showing gynaecomastia. J. Pathol. 170, 37–43 (1993).

Kuroda, H., Ohnisi, K., Sakamoto, G. & Itoyama, S. Clinicopathological study of breast tissue in female-to-male transsexuals. Surg. Today 38, 1067–71 (2008).

Grynberg, M., Fanchin, R., Dubost, G., Colau, J., Brémon-Weil, C. & Frydman, R. et al. Histology of genital tract and breast tissue after long-term testosterone administration in a female-to-male transsexual population. Reprod. BioMedicine Online 20, 553–558 (2010).

East, E. G., Gast, K. M., Kuzon, W. M., Roberts, E., Zhao, L. & Jorns, J. Clinicopathological findings in female-to-male gender-affirming breast surgery. Histopathology 71, 859–65 (2017).

Van Renterghem, S. M. J., Van Dorpe, J., Monstrey, S. J., Defreyne, J., Claes, K. E. Y. & Praet, M. et al. Routine histopathological examination after female-to-male gender-confirming mastectomy. Br. J. Surg. 105, 885–892 (2018).

Torous, V. F. & Schnitt, S. J. Histopathologic findings in breast surgical specimens from patients undergoing female-to-male gender reassignment surgery. Mod. Pathol. 32, 346–353 (2019).

Hernandez, A., Schwartz, C. J., Warfield, D., Thomas, K. M., Bluebond-Langner, R. & Ozerdem, U. et al. Pathologic Evaluation of Breast Tissue From Transmasculine Individuals Undergoing Gender-Affirming Chest Masculinization. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 144, 888–893 (2020).

Baker, G. M., Guzman-Arocho, Y. D., Bret-Mounet, V. C., Torous, V. F., Schnitt, S. J. & Tobias, A. M. Testosterone therapy and breast histopathological features in transgender individuals. Mod. Pathol. 34, 85–94 (2021).

Slagter, M. H., Gooren, L. J., Scorilas, A., Petraki, C. D. & Diamandis, E. P. Effects of long-term androgen administration on breast tissue of female-to-male transsexuals. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 54, 905–910 (2006).

Millington, K., Hayes, K., Pilcher, S., Roberts, S., Vargas, S. O., French, A. et al. A serous borderline ovarian tumour in a transgender male adolescent. Br. J. Cancer 124, 567–569 (2021).

Kornegoor, R., Verschuur-Maes, A. H. J., Burger, H. & van Diest, P. J. The 3-layered ductal epithelium in gynecomastia. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 36, 762–768 (2012).

Boskey, E. R., Taghinia, A. H. & Ganor, O. Association of surgical risk with exogenous hormone use in transgender patients: A systematic review. JAMA Surg. 154, 159 (2019).

Anderson, W. J., Kolin, D. L., Neville, G., Diamond, D. A., Crum, C. P. & Hirsch, M. S. et al. Prostatic metaplasia of the vagina and uterine cervix: an androgen-associated glandular lesion of surface squamous epithelium. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 44, 1040–1049 (2020).

Singh, K., Sung, C. J., Lawrence, W. D. & Quddus, M. R. Testosterone-induced “Virilization” of mesonephric duct remnants and cervical squamous epithelium in female-to-male transgenders: A report of 3 cases. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 36, 328–333 (2017).

Gelmann, E. P., Bowen, C. & Bubendorf, L. Expression of NKX3.1 in normal and malignant tissues. Prostate 55, 111–117 (2003).

Yu, H. & Berkel, H. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in women. J. La. State. Med. Soc. 151, 209–213 (1999).

Gatalica, Z., Norris, B. A. & Kovatich, A. J. Immunohistochemical localization of prostate-specific antigen in ductal epithelium of male breast. Potential diagnostic pitfall in patients with gynecomastia. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 8, 158–161 (2000).

Boutin, E. L., Battle, E. & Cunha, G. R. The response of female urogenital tract epithelia to mesenchymal inductors is restricted by the germ layer origin of the epithelium: prostatic inductions. Differentiation 48, 99–105 (1999).

Cunha, G. R. Age-dependent loss of sensitivity of female urogenital sinus to androgenic conditions as a function of the epithelia-stromal interaction in mice. Endocrinology 97, 665–673 (1975).

Dillon, D. A. & Lester, S. C. Lesions of the nipple. Surg. Pathol. Clin. 2, 391–412 (2009).

Kayserili, H., Altunoglu, U., Yesil, G. & Rosti, R. Ö. Microcephaly, dysmorphic features, corneal dystrophy, hairy nipples, underdeveloped labioscrotal folds, and small cerebellum in four patients. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 170, 1391–1399 (2016).

Rad, A., Altunoglu, U., Miller, R., Maroofian, R., James, K. N. & Çağlayan, A. O. et al. MAB21L1 loss of function causes a syndromic neurodevelopmental disorder with distinctive cerebellar, ocular, craniofacial and genital features (COFG syndrome). J. Med. Genet. 56, 332–339 (2019).

Mayer, J. A., Foley, J., De La Cruz, D., Chuong, C. & Widelitz, R. Conversion of the nipple to hair-bearing epithelia by lowering bone morphogenetic protein pathway activity at the dermal-epidermal interface. Am. J. Pathol. 173, 1339–1348 (2008).

Chandramouli, A., Hatsell, S. J., Pinderhughes, A., Koetz, L. & Cowin, P. Gli activity is critical at multiple stages of embryonic mammary and nipple development. PLoS. One 8, e79845 (2013).

Rosenfield R. L. Normal and Premature Adrenarche. Endocr. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1210/endrev/bnab009, bnab009 (2021). published online ahead of print.

Eyckmans, J., Boudou, T., Yu, X. & Chen, C. S. A hitchhiker’s guide to mechanobiology. Dev. Cell. 21, 35–47 (2011).

Wipff, P.-J., Rifkin, D. B., Meister, J.-J. & Hinz, B. Myofibroblast contraction activates latent TGF-beta1 from the extracellular matrix. J. Cell. Biol. 179, 1311–1323 (2007).

Wozniak, M. A., Desai, R., Solski, P. A., Der, C. J. & Keely, P. J. ROCK-generated contractility regulates breast epithelial cell differentiation in response to the physical properties of a three-dimensional collagen matrix. J. Cell. Biol. 163, 583–595 (2003).

Mustoe, T. The mechanical bra for breast enlargement. Aeset. Surg. J. 20, 176–178 (2000).

Ofri, A., Dona, E. & O’Toole, S. Squamous metaplasia of lactiferous ducts (SMOLD): An under-recognised entity. BMJ. Case. Rep. 13, e237568 (2020).

Yu, H., Diamandis, E. P., Monne, M. & Croce, C. M. Oral contraceptive-induced expression of prostate-specific antigen in the female breast. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 6615–6618 (1995).

Grimstad, F., Kremen, J., Shim, J., Charlton, B. M. & Boskey, E. R. Breakthrough bleeding in transgender and gender diverse adolescents and young adults on long-term testosterone. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 34, 706–716 (2021).

García-Rodríguez, A., de la Casa, M., Peinado, H., Gosálves, J. & Roy, R. Human prostasomes from normozoospermic and non-normozoospermic men show a differential protein expression pattern. Andrology 6, 585–596 (2018).

Gököz, Ö., Presenti, L., Gambacorta, G., Zolfanelli, F., Trocarico, R. & Nistri, R. et al. Skin-type adnexal tumor with trichoblastic germinative differentiation in the breast: a case report. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 19, 527–533 (2011).

Yu, H., Diamandis, E. P., Levesque, M., Giai, M., Roagna, R. & Ponzone, R. et al. Prostate specific antigen in breast cancer, benign breast disease and normal breast tissue. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 40, 171–178 (1996).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center, Boston, MA, for the use of the Specialized Histopathology Core, that provided immunohistochemistry technical service. Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center is supported in part by an NCI Cancer Center Support Grant # NIH 5 P30 CA06516.

Funding

Funds provided by the Department of Pathology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, were used to support the costs of immunostaining.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CFK and SOV performed study concept and design; all authors performed development of methodology and writing, review and revision of the paper; CFK, DJ, HPWK, and SOV provided acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, C.F., Jou, D., Ganor, O. et al. Prostatic metaplasia and pilar differentiation in gender-affirming mastectomy specimens. Mod Pathol 35, 386–395 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-021-00951-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-021-00951-2

This article is cited by

-

Utilization of NKX3.1 and P501S to distinguish primary breast carcinoma from metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma in male patients

Virchows Archiv (2025)

-

Prostatic metaplasia of the vagina in transmasculine individuals

World Journal of Urology (2022)

-

Norethisterone/testosterone-cipionate

Reactions Weekly (2022)