Abstract

DNA methylation plays a crucial role in the progression and metastasis of colorectal cancer (CRC), yet the mechanisms underlying its effect at specific loci remain poorly understood. We previously identified cg24067911 hypomethylation as a potential biomarker associated with poor CRC prognosis. To investigate the role of cg24067911 methylation in CRC metastasis and elucidate its underlying molecular mechanisms, we utilized the CRISPR-dCas9-DNMT3a system to specifically modify the methylation status of cg24067911. Then, we performed high-throughput transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing, RNA sequencing, and chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis. We demonstrated that cg24067911 was located within an enhancer region of the ATXN1 gene, where it was bound by BCL6. Hypomethylation of cg24067911 improved the binding of BCL6 to this enhancer, leading to upregulated transcription of ATXN1. Furthermore, ATXN1 was found to act as a transcription factor that upregulates CDH2, promoting epithelial-mesenchymal transition and facilitating CRC metastasis. These findings not only reveal that cg24067911 methylation modulates CRC metastasis through a novel epigenetic mechanism involving ATXN1 and CDH2, but also highlight cg24067911 as a potential prognostic marker for CRC and suggest that targeted epigenetic therapies could be an effective strategy for treating CRC metastasis in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide which has an increasing trend in morbidity and mortality [1]. About 20% of CRC patients present with metastatic disease at diagnosis. For patients receiving curative treatment, 25% of them would finally experience metastasis [2]. Efforts have been made to enhance accuracy in predicting the prognosis of CRC and metastasis [3, 4]. Metastatic CRC is associated with poor prognosis and limited treatment options, therefore highlighting the importance of understanding the mechanisms underlying metastasis for developing effective therapeutic strategies. Although the mechanism of CRC metastasis has been investigated for several decades in areas such as genetic abnormalities, metastasis-initiating cells, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and tumor microenvironment [5], little impact has been shed on the reduction of CRC metastasis in clinical practice.

Epigenetic modifications are the main mediators of gene regulation and play important roles in CRC metastasis [6]. As the major component, DNA methylation-based biomarkers are proven powerful diagnostic and prognostic markers in cancer [7]. CRC with and without metastasis was reported to have distinct profiles of DNA methylation evolution, and most DNA methylation statuses were established before metastasis [8], suggesting the metastasis-facilitating role of DNA methylation in CRC. Previous studies have typically used broad-spectrum methyltransferase inhibitors (such as decitabine, Azacitidine, and so on) to explore the function of the change of DNA methylation. However, there are limited mechanical studies about the role of individual loci of DNA methylation in CRC metastasis. CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) is a revolutionary gene-editing technology that allows for targeted modifications of the genome. Utilizing CRISPR-based tools such as dCas9 (catalytically dead Cas9) fused to DNA methyltransferases or demethylases (e.g. DNMT3A), researchers can now manipulate DNA methylation patterns at specific genomic loci [9]. These innovative tools make it possible to gain insights into the causal relationship between DNA methylation changes and biological phenotypes of cancer, and to pave the way for the development of novel therapeutic strategies targeting DNA methylation.

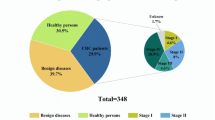

We have previously established predictive diagnostic and prognostic models using cell-free DNA methylation signature, based on a large cohort of 801 CRC patients and 1021 controls, which has a high accuracy [10]. Among the markers, cg24067911 has both diagnostic value and metastasis-predictive effect, indicating its potential role in CRC metastasis. The CpG site cg24067911 is a novel DNA methylation locus which has not been reported. Its host gene, ATXN1, is a protein-coding gene involved in transcriptional repression, and a component of the Notch signaling pathway [11]. Most of the studies related with ATXN1 are focused on neurology [12,13,14], while little is known about its function in cancer.

In the present study, utilizing CRISPR/dCas9-DNMT3a, we successfully edited the methylation status on our target locus cg24067911, and demonstrated its role in CRC metastasis in vitro and in vivo. We then explored the downstream key gene ATXN1 in CRC and found ATXN1 could promote CRC metastasis via epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) by facilitating CDH2 (N-cadherin) expression as a transcription factor. The clinical significance of cg24067911/ATXN1 was also validated. Our findings indicated a novel metastatic mechanism of CRC.

Materials and methods

Ethic statements

We received written informed consents obtained from all patients before sample collection, and the study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (B2017-019-01). The animal protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University with approval number L102012021020G. The specifically synthesized oligonucleotides sequence were listed on Table S2. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Human specimens

For the validation of the methylation level of cg24067911, a total of 40 paired tumor and adjacent normal tissues from 20 patients were performed dd-PCR. For the validation of the mRNA expression of ATXN1, a total of 84 paired tumor and adjacent normal tissues from 42 patients were performed qRT-PCR. For the validation of the protein expression of ATXN1, a total of 488 paired tumor and adjacent normal formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples from 244 patients were performed IHC.

Cancer cell culture

Human CRC cell lines, including DLD-1, HCT116, SW480, RKO, SW620, and non-cancerous HEK-293T cell line were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cryopreserved in our laboratory. Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; GIBCO, #C11995500BT) was used to culture SW480 and SW620, while DLD-1 and HCT116 were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO, #C11875500BT). And RKO cells were grown in minimum essential medium (MEM; GIBCO, #C11095500BT) containing MEM non-essential amino acids (GIBCO, #11140050). All medium were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; TransGen Biotech, #FS301-02) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (penicillin 100 U/mL and streptomycin 100 μg/mL; BasalMedia, #S110JV). All culture vessels were maintained in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. All cell lines have been recently authenticated by STR profiling and tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Mice

The HCT116 and SW620 cells were cultured as described above. Six-week-old female NSG mice (Bestest100, Zhuhai, China) were anesthetized and then inoculated with 1.5 × 106 of HCT116 or DLD-1 cells per mouse through spleen. Six-week-old female Balb/c nude mice (Bestest100, Zhuhai, China) were injected 2.5 × 106 of SW620 cells per mouse through portal vein. In vivo imaging was performed in 2 weeks or 4 weeks post inoculation. HCT116 or SW620 cells were treated with ATXN1 knockdown or negative control (NC). Animals were continuously monitored, and mice were euthanized via asphyxiation when any of the following endpoints were met: study termination, tumor ulceration, body weight loss equal or greater than 20%, or moribund appearance. After execution, the livers of mice were dissected and performed H&E stain.

Plasmids and virus transfection

For silencing targeted genes, small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting ATXN1 and BCL6 were synthesized by RiboBio (Guangzhou, China), and subsequently the plasmid was transfected by using Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #13778150). For construction of stable cell lines knockdown or overexpressing ATXN1, HEK-293T cells were used to package lentiviruses of ATXN1 short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) and overexpression ATXN1 plasmid, and then infected CRC cells for 18–24 h in the presence of polybrene (8 μg/mL; Beyotime, #C0351), followed by selection with appropriate concentration of puromycin (InvivoGen, #ant-pr-1) for at least 7 days.

Targeted DNA methylation

The guide RNA (sgRNA) was inserted into pdCas9-DNMT3a-EGFP vector (Addgene) synthesized by Lianfeng (Shanghai, China) or pPB-dCas9-DNMT3a-EGFP vector synthesized by VectorBuilder (Guangzhou, China). The CRC cell lines were transfected by the dCas9-DNMT3a-sgRNA plasmid. For transposon plasmid transfection, DLD-1 and HCT116 cells were cotransfected by the PB-dCas9-DNMT3a-sgRNA and hyPBase plasmid. EGFP positive cells were subsequently selected by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). The sorted cells were then verified targeting methylation at CpG site cg24067911.

Pyrosequencing

DNA extraction from cell lines was performed using the TIANamp Genomic DNA Kit (TIANGEN BIOTECH, #DP304), following by measurement using NanoDrop Spectrophotometer to normalize the concentration of samples. Normalized DNA samples were subjected to bisulfite conversion and purification using the EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen, #59104). Primers suitable for the analysis were designed using PyroMark Assay Design 2.0 (Qiagen), and a PCR reaction master mix was set up according to the protocol of KAPA2G Robust HotStart PCR Kit (ROCHE, #K5525). The PCR tubes were placed in a thermal cycler with the following programmed cycling conditions: an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min; 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 56 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min; a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. The amplified products were then proceeded with pyrosequencing experiment. The methylation levels of cg24067911 and its neighboring CpG site and ATXN1 promoter were quantitatively analyzed using the PyroMark Q96 ID pyrosequencing system (Qiagen) as described previously [15, 16]. The Pyro Q-CpG software was used to automatically analyze the methylation status of each site.

Western blot

Cell lysates or tissue lysates were prepared and protein concentrations were determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Invivogen, #23227). Equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% fat-free milk in TBST buffer for at least 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated with primary antibodies against ATXN1 (1:1000; Novus Biologicals, #NBP1-51689) and β-actin (1:1000; Cell signaling technology, #3700), N-cadherin (1:5000; Proteintech, #66219-1-Ig), E-cadherin (1:5000; Proteintech, #60335-1-Ig), and Vimentin (1:20000; Proteintech, #10366-1-AP) overnight at 4°C. After washing with TBST, the membrane was incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized using an ECL detection system (Tanon, #180-5001 A) and imaged with a chemiluminescent imaging system. β-Actin was used as a loading control for normalization.

Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA extraction from cell lines or tissues was performed using the RNA-Quick Purification Kit (ES Science, #RN001), and reverse transcribed the extracted RNA into cDNA using PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (Takara, #RR036Q). Prepare a master mix containing cDNA template, specific primers, and master mix (Promega, #A6001) to conduct RT-qPCR reactions on the LightCycler 480 Instrument (Roche). All steps were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Conduct RT-qPCR experiments for cells in triplicate. Utilize the 2−(ΔΔCt) method to quantitatively detect the relative expression levels of each gene. The specific primers synthesized by TsingKe (Beijing, China) were listed in the Table S2.

Transwell migration assay

Transwell inserts with a pore size of 8 μm were placed above a 24-well plate (Corning, #353097). Cells were serum-starved for 24 h and then seeded in the upper chamber of inserts with a density of 2-2.5×105 cells per chamber. The lower chamber was filled with medium containing 20% FBS. After 24 h of incubation, non-migrated cells were removed from the upper chamber, and migrated cells on the lower surface were fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde, stained by 0.1% crystal violet staining solution, and counted five random fields of each insert under a microscope. The number of migrated cells was quantified and normalized to the control group.

Matrigel invasion assays

Transwell inserts with a pore size of 8 μm were coated with Matrigel diluted 1:10 in serum-free medium (60 µL/insert), placed above a 24-well plate (Corning, #353097) and polymerized at 37°C for 1 h. After 24 h serum starvation, 5×105 cells were seeded in each upper chamber. The lower chamber was filled with medium containing 20% FBS. After 24 h incubation, non-invaded cells were removed from the upper chamber, and invaded cells on the lower surface were fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde, stained by 0.1% crystal violet staining solution, then counted in random fields per insert under a microscope. The number of invaded cells was quantified and normalized to the control group.

Scratch wound healing assay

Prior to seeding cells into 6-well plates at an appropriate density to ensure confluency the following day, lines were marked on the back of each well. On the second day post-seeding, sterile 200 μl pipette tips were used to gently create uniform and distinct scratches perpendicular to the marked lines. The previous culture medium was then aspirated, the cells were washed with PBS to remove cell debris resulting from the scratch, and obtained fresh medium to continue culturing. Images of the wounded area were captured by Leica X microscope (Leica, German) immediately after scratching as a baseline reference, and at every 24 h. The changes in wound area were measured using ImageJ, and the cell migration rates were calculated by comparing the wound area at different time points among different groups.

MTT assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates with a density of 5000 cells per well for 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, 96 h and 120 h gradient time culture. At each point in time, MTT solution (Beyotime, #C0009S) was added to the corresponding wells and incubated for 4 h. The formazan crystals were then dissolved in DMSO and the absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a microplate reader. Cell proliferation was calculated as the percentage of absorbance relative to the control group. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

The ChIP assay was conducted using MAGnify Chromatin Immunoprecipitation System (Invitrogen, #492024) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The resultant chromatin was immunoprecipitated using anti-ATXN1 (1:100; Novus Biologicals, #NBP1-51689), anti-BCL6 (1:200; Cell Signaling Technology, #5650) antibody, or anti-IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, #3900) as the isotype-control antibody. PCR was performed to verify the binding the potential TF and the cis-regulatory sequences, and the data were calculated as the percentage of the input. The amplified products were finally analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. The primers used are listed in the Supplementary Materials.

Dual-luciferase report assay

Cells were transfected with the plasmid containing cis-regulatory sequence and the firefly luciferase reporter gene (Synbio Technologies), along with the pRL-TK Renilla Luciferase plasmid. The Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, #E1910) was employed to conduct the assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The ratio of Renilla to firefly luciferase activity was calculated to normalize the data.

Droplet digital PCR

Total DNA extraction from cell lines or tissues was performed using the TIANamp Genomic DNA kit (TIANGEN, #DP304,), and converted the extracted DNA using EZ DNA Methylation-LightningTM Kit (ZYMO RESEARCH, #D5031). Add ddPCR mixtures DNA template after bisulfite conversion, specific primers & probes, and ddPCR Supermix (BIO-RAD, #1863024) and Droplet Generation Oil (BIO-RAD, #1863005) into DG8 Cartridges (BIO-RAD, #1864008) for droplet generation. Prepared droplet mixtures were PCR amplified using T100 Thermal Cycler, and detected by QX200TM Droplet Reader. All steps were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Conduct ddPCR experiments for cells in triplicate. Utilize QuantaSoftTM Analysis Pro to analyse cg24067911 methylation data.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay

IHC analysis was conducted on paraffin-embedded specimens as previously reported [17]. The IHC stained sections were reviewed and scored independently by two pathologists. A final score was then calculated. The IHC scores were compared between tumor tissues and adjacent normal tissues; as for the stratification analysis, the cutoff value for the high- and low- expression of ATXNl was obtained as tumortissues lHC scores 91.25 (range, 0 to 160) through ROC curve of each group.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test or Chi-square test was used for statistical analysis. The data were shown as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were analyzed by SPSS 21.0 software or GraphPad Prism 9.3, and a P < 0.05 was considered to be statistical significance. Survival analysis was conducted using Kaplan-Meier method and compared by Log-Rank test.

Results

Identification of the role of CpG site cg24067911 in the CRC metastasis

Our prior studies identified cg24067911 hypomethylation as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in colorectal cancer (CRC) (Fig. 1A, B, Fig. S1A), with CRC tissues exhibiting significantly reduced methylation levels compared to normal counterparts in our cohort [10] and the TCGA database (Fig. 1A, Fig. S1B–D). Further droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) on paired tissues revealed progressively intensified cg24067911 hypomethylation during CRC advancement, where metastatic lesions exhibited significantly lower methylation levels than matched primary tumors (Fig. S1E, F). In addition, recurrent or metastasis cases after radical resection additionally demonstrated more pronounced hypomethylation compared to non-recurrent counterparts (Fig. S1G). These data collectively underscored that cg24067911 hypomethylation was associated with disease aggressiveness.

A Hypomethylation of cg24067911 is a biomarker for CRC diagnosis. Left, the ROC curve of cg24067911 as a predictive marker for CRC diagnosis based on CRC patients from Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center previously reported. Right, box plot of the cg24067911 methylation level of normal and CRC patients’s cfDNA from Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center. Tumor (n = 801), Normal (n = 1021). AUC, area under curve. B Hypomethylation of cg24067911 is a prognostic biomarker for CRC and is associated with poor prognosis of CRC based on CRC patients from Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center previously reported. Up, the ROC curve of cg24067911 as a prognostic marker for CRC. Down, the association of cg24067911 hypomethylation with poor prognosis. AUC, area under curve; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval. C The schematic plot of CRISPR-dCas9-DNMT3a-mediated DNA methylation editing system. DNMT3a, DNA (Cytosine-5-)-Methyltransferase 3 Alpha. D Pyrosequencing examines methylation level of cg24067911, of the neighboring CpG site, and of ATXN1 promoter in dCas9-DNMT3a treated cells or controlled ones. Student’s t-test. E Representative images of transwell assays in dCas9-DNMT3a treated DLD-1 cells or controlled ones. F Quantified data of transwell assays in dCas9-DNMT3a treated DLD-1 cells or controlled ones. Student’s t-test. G Representative images of scratch wound healing assays in dCas9-DNMT3a treated DLD-1 cells or controlled ones. H Quantified data of scratch wound healing assays in dCas9-DNMT3a treated DLD-1 cells or controlled ones. Student’s t-test. The data are shown as the mean ± SD; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, ns for not significant.

To evaluate whether cg24067911 hypomethylation has a causal effect on CRC progression, we employed CRISPR-dCas9-DNMT3a-mediated DNA methylation editing system to upregulate the methylation level of the target CpG site cg24067911 (Fig. 1C), and carried out a series of assays in vitro to explore its cancer-associated phenotypes in CRC. Firstly, we succeeded in targeted methylation at cg24067911 in human colon cancer cell lines DLD-1, verifying by pyrosequencing. The methylation rate increased significantly at the targeted site of cg24069711, meanwhile, the methylation level was not significantly changed at the nearest CpG site neighboring cg24069711 and at the promoter of ATXN1 (Fig. 1D). Additionally, we employed a transposon system to deliver the dCas9-DNMT3A editing system in CRC cell lines, validating by ddPCR and pyrosequencing (Fig. S2A–E), and yielded results consistent with our prior approach using lentiviral transfection of the system. Then the dCas9-DNMT3a transfected cells were observed to show reduced migration potentials in transwell assays (Fig. 1E, F) and scratch assays (Fig. 1G, H). Nevertheless, the MTT assays demonstrated no significant changes in proliferation ability between the dCas9-DNMT3a transfected cells and controlled ones (Fig. S2F). These in vitro assays demonstrated that low methylation level of cg24067911 enhanced CRC cells migration, while upregulation of its methylation level could impair the metastatic ability.

Identification of an enhancer at cg24067911 and its regulatory influence on ATXN1 expression

The CpG site cg24067911 is located at 5’ UTR region of ATXN1 (Fig. 2A), and its methylation has possibility to influence the expression level of the host gene. The RNA-seq results showed that ATXN1 mRNA expression was downregulated in dCas9-DNMT3a cells compared to the controlled cells, which was validated by RT-qPCR results (Fig. 2B, C). Since the primary function of DNA methylation is epigenetic modulation, we investigated the epigenetic features of cg24067911 to further explore the underlying mechanism. We searched the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) Genome Browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu/) and WASHU EPIGENOME Browser (https://epigenomegateway.wustl.edu/), and collected the chromatin Immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) data of histone modification at cg24067911. We found that H3K4me1 and H3K27ac modifications were enriched in the region of cg24067911 in CRC cells, which indicated that the cg24067911 is located in an enhancer region, and a prominent enrichment of H3K27ac in CRC cells than normal colon mucosa implied the activation of the enhancer in CRC (Fig. 2D). As previously established, DNA methylation alters the spatial openness of the cis-regulatory sequences to combine with transcription factors (TFs), and consequently influences the downstream gene expression. The ATAC-seq result demonstrated a decreased chromatin accessibility in the region at cg24067911 site in dCas9-DNMT3a DLD-1 cell lines compared with controlled cells (Fig. 2E). These findings suggested that the methylation of cg24067911 could influence the enhancer functioning.

A The location of cg24067911 and corresponding cis-regulatory elements marked in UCSC Genome Browser. B Normalized read count from RNA-seq of ATXN1 in dCas9-DNMT3a treated cells and the controlled ones. C RT-qPCR data of ATXN1 in dCas9-DNMT3a treated cells and the controlled ones. Student’s t-test. D Peak of ChIP-seq of H3K4me1 and H3K27ac in colonic mucosa and CRC cell line HCT116, gathered from WASHU EPIGENOME Browser. The red arrow indicates the CpG site cg24067911. E ATAC-seq data shows the chromatin openness at cg24067911 is reduced in dCas9-DNMT3a treated cells than the controlled ones. The red arrow indicates the CpG site cg24067911. F Up, Schematic venn plot of the screening process of potential TFs binding to the region of cg24067911. Down, the statistics of expression correlation between ATXN1 and potential TFs (JUND, FOSL2, MZF1, BCL6). G RT-qPCR data of ATXN1 in si-BCL6 treated CRC cell lines and the controlled ones. H The predicted binding motif. I ChIP was used to assess the binding of BCL6 to cg24067911-locating enhancer. Up, the plot of DNA agarose gel electrophoresis shows BCL6 could bind to cg24067911-locating enhancer sequence. Down, quantified data of PCR of the immunoprecipitated DNA from ChIP. Student’s t-test. The data are shown as the mean ± SD; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

We then explored the transcription factor involved in the enhancer-functioning process. Searching the JASPAR (https://jaspar.elixir.no/) database and GeneHancer database [18], we predicted the possible TFs which have the potential to bind the region at CpG site cg24067911, and sorted out the TFs in significant correlation with mRNA level of ATXN1 based on RNA-seq data of TCGA CRC cohort (Fig. 2F). We knocked down the expression of the top 4 TFs by siRNA (si-BCL6, si-FOSL2, si-MZF1, si-JUND) and observed a significant decrease in ATXN1 mRNA expression caused by si-BCL6 (Fig. 2G; Fig. S3A–C). The binding ability of BCL6 to the cg24067911-locating enhancer was demonstrated by the chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay (Fig. 2H, I). Furthermore, we treated BCL6-knockdown CRC cell lines with decitabine or bobcat339, which is a non-target-specific demethylating or methylating agent, respectively, and observed significant downregulation of ATXN1 in all groups, which implied that non-target-specific epigenetic drugs play a limited role in the regulatory process (Fig. S3D).

ATXN1 could promote CRC metastasis

The function of ATXN1 in CRC was unveiled, and whether it could act as the downstream key factor of cg24067911 methylation remained unclear. In this study, we employed different CRC cell lines to knockdown ATXN1 or overexpress ATXN1 (Fig. S4A–F). We performed transwell assays and scratch wound healing assays, and found that downregulation of ATXN1 expression could significantly decrease the migration of CRC cells, while ATXN1 overexpression could promote CRC metastasis. (Fig. 3A–D; Fig. S5A–C). Nevertheless, the proliferation ability was measured by MTT assays and it found no significant differences altered by ATXN1 expression (Fig. S5D, E). In addition, we overexpressed ATXN1 in the DLD-1 or HCT116 dCas9-sgRNA3 cells (Fig. S2, Fig. S4G), and performed matrigel invasion assays and scratch wound healing assays demonstrated that the migratory capacity was restored in these cells (Fig. 3E, F, Fig. S4H).

A Representative images (left) and quantified data (right) of transwell assays in HCT116 cells with ATXN1 knockdown and the controlled ones (NC). Student’s t-test. B Representative images (left) and quantified data (right) of scratch wound healing assays in HCT116 cells with ATXN1 knockdown and the controlled ones. Student’s t-test. C Representative images (left) and quantified data (right) of transwell assays in RKO cells with ATXN1 overexpression and the controlled ones. Student’s t-test. D Representative images (left) and quantified data (right) of scratch wound healing assays in RKO cells with ATXN1 overexpression and the controlled ones. Student’s t-test. E Representative images (left) and quantified data (right) of matrigel invasion assays in DLD-1 cells. Student’s t-test. F Representative images (left) and quantified data (right) of scratch wound healing assays in DLD-1 cells. Student’s t-test. G–H The in vivo bioluminescence imaging G of NSG mouse with spleen injection of HCT116 cells with ATXN1 knockdown and the controlled ones, and the bar chart H of radiant efficiency of luminescence of liver metastases. Student’s t-test. I, J The bar chart of the weight I, and the representative gross and microscopic images J of the liver harvested from the NSG mouse with spleen injection of HCT116 cells with ATXN1 knockdown and the controlled ones. Student’s t-test. K, L The representative gross and microscopic images K, and the bar chart of the weight L of the liver harvested from the NSG mouse with spleen injection of HCT116 cells with ATXN1 knockdown and the controlled ones. Student’s t-test. The data are shown as the mean ± SD; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

The function of ATXN1 in CRC was further validated in vivo as well that significantly fewer liver metastatic lesions were observed in mice treated with shRNA-ATXN1 than those with NC (Fig. 3G–J, Fig. S6). Furthermore, we utilized the dCas9-sgRNA3 cells and the controlled ones to construct liver metastasis model, we observed that upregulation of cg24067911 methylation level significantly attenuated metastatic progression of CRC (Fig. 3K–L, Fig. S7). It accorded with the function of cg24067911 methylation/demethylation, which implied that cg24067911 might function with downstream ATXN1 to influence CRC metastasis under certain mechanisms.

ATXN1 could modulate EMT by regulating CDH2 expression as a transcription factor

The underlying mechanism might be simultaneously influenced by the methylation level of cg24067911 and expression level of ATXN1. We conducted GO/KEGG analysis to investigate the pathways where the differential expression genes by cg24067911 methylation and ATXN1 expression in COAD CRC cohort were enriched. It turned out that the pathways concerning cell adhesion were commonly enriched in cg24067911 hypermethylation and ATXN1 low expression (Fig. 4A). Through GSEA analysis, EMT pathway which could be the consequence of altered cell-cell adhesion was also enriched in ATXN1 functioning (Fig. 4B), which might underlie the promotion of CRC metastasis by cg24067911/ATXN1. We then explored whether ATXN1 functioned in EMT process. Western blot and RT-qPCR demonstrated the expression of EMT markers could be changed by ATXN1, that is ATXN1 knockdown decreased the expression of CDH2 (N-cadherin) and increased the expression of CDH1 (E-cadherin) (Fig. 4C, D). The regulation was validated by ATXN1 overexpression (Fig. 4C, E). Furthermore, protein-protein interaction among ATXN1 and EMT associated genes (Table S1) was explored based on STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/), and the direct association between ATXN1 and CDH2 was observed (Fig. 4F). There is possibility that CDH2 is the key effector of cg24067911/ATXN1 in CRC metastasis.

A GO/KEGG analysis of cg24067911 methylation status and ATXN1 expression level. Left, box plot of common GO terms enriched by DEGs of cg24067911 hypermethylation (dCas9-DNMT3a treated DLD-1 cells versus controlled DLD-1 cells); Right, box plot of common GO terms enriched by DEGs of ATXN1 (low versus high expression). GO, Gene Ontology. B GSEA plot of ATXN1 functioning enriched in Hallmark EMT pathway. C Immunoblotting by western blot of ATXN1 and EMT markers E-cadherin and N-cadherin in ATXN1-knockdown HCT116 by siRNA-ATXN1 and ATXN1-overexpressing RKO. D, E RT-qPCR data of ATXN1, CDH1 and CDH2 in ATXN1-knockdown HCT116 D and ATXN1-overexpressing RKO E Student’s t-test. F Protein-protein interaction analysis of ATXN1 and EMT-associated genes. G The binding ability of ATXN1 to CDH2 promoter sequence. Left up, the plot of DNA agarose gel electrophoresis of the ChIP assay. Left down, the predicted binding motif. Right, quantified data of PCR of the immunoprecipitated DNA from ChIP assay. H The dual luciferase reporter assay measured transcriptional regulatory activity of ATXN1 on CDH2 promoter with wild type or mutations. Left, the schematic plot of CDH2 promoter and designed mutations in promoter plasmids. Right, measurement and comparisons of relative luciferase activity of CDH2 promoter in wild type or mutated type between ATXN1 overexpression and normal control. Student’s t-test. The data are shown as the mean ± SD; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

ATXN1 used to be reported as a TF to bind DNA sequence or chromatin [11], based on which we conducted ATXN1-ChIP and demonstrated that ATXN1 could bind to the promoter (TSS -880 ~ -597) of CDH2 (Fig. 4G). By dual luciferase reporter gene expression assay, it was found that binding ATXN1 to CDH2 promoter could significantly increase CDH2 transcription, and the result was impaired when binding site was mutated (Fig. 4H). These findings above clarified the underlying mechanism that demethylation of cg24067911 enhances ATXN1 expression which functions as the TF of CDH2 to increase N-cadherin expression, and consequently promote CRC metastasis.

Clinical significance of ATXN1 in CRC samples

We examined ATXN1 expression in retrospectively collected CRC samples and paired normal adjacent tissues by RT-qPCR, and found that ATXN1 was significantly higher in CRC samples than the paired normal samples (Fig. 5A). Other public data collected from Oncomine database also demonstrated significantly higher expression in CRC tumor than normal tissues (Fig. 5B, C). Based on the immunohistochemical staining results of the CRC patients, the expression of ATXN1 was elevated in tumor tissues than the normal tissues (Fig. 5D). Moreover, we collected the corresponding clinical and pathological information, and proved that high expression of ATXN1 was more prominent in patients with stage IV, in oxaplatin-resistent patients, and in patients with recurrent disease (Fig. 5E–G). In terms of prognosis, we found that patients with higher expression of ATXN1 presented significantly shorter overall survival (OS) than those with lower expression (Fig. 5H), and relatively shortened DFS among patients with stage III CRC (Fig. 5I). And the survival analysis based on TCGA CRC COAD cohort showed higher expression of ATXN1 with decreased disease-free survival (DFS) (Fig. 5J).

A RT-qPCR data of ATXN1 in paired tumor and normal samples retrospectively collected from Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center. Paired student’s t-test. B, C Relative ATXN1 mRNA expression data of CRC tumor and normal tissues from Oncomine database collected by Kaiser B and Skrzypczak C. D Measurement of ATXN1 expression by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining in CRC compared to the adjacent normal tissue. Left, representative microscopic images of ATXN1-staining tumor sample and paired normal sample. Right, box plot of IHC staining scores of ATXN1. Student’s t-test. E Boxplot of ATXN1 expression between patients with stage III and stage IV CRC from SYSUCC. Chi-square test. F Boxplot of ATXN1 expression between patients sensitive to oxaplatin treatment and those resistant to oxaplatin treatment from SYSUCC. Chi-square test. G Boxplot of ATXN1 expression between stage III patients with or without progression from SYSUCC. Chi-square test. H Overall survival curves of patients with CRC stratified by ATXN1 expression from SYSUCC. Kaplan-Meier method and Log-Rank test. I Disease-free survival curves of patients with stage III CRC stratified by ATXN1 expression from SYSUCC. Kaplan-Meier method and Log-Rank test. J Disease-free survival curves of patients in TCGA CRC cohort stratified by ATXN1 expression. Kaplan-Meier method and Log-Rank test. The data are shown as the mean ± SD; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

Despite advances in screening and treatment options for CRC, there is a critical need to improve diagnostic methods and develop more effective therapies. DNA methylation has emerged as a promising area of research in the field of CRC. Aberrant DNA methylation patterns, characterized by global hypomethylation and gene-specific hypermethylation, have been frequently observed in colorectal cancer tissues compared to normal colon tissues [19]. These epigenetic alterations can result in the silencing of tumor suppressor genes and the activation of oncogenes, leading to uncontrolled cell growth and tumorigenesis. Based on the differences of DNA methylation patterns, CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) classification was established to stratify patients into CIMP-H (CIMP 1) and CIMP-L (CIMP 2) subgroups with different prognosis [20, 21]. Various individual loci of DNA methylation have been identified to be potential prognostic and metastatic-promoting factors, such as MPPED2 [22], SOX4 [23], FIGN, HTRA3, BDNF, HCN4 and STAC2 [24], while most of the reports lack further exploration in underlying mechanism. And only a few studies investigated the mechanism of modulation in certain methylated genes, including SLIT1 and ANGPTL4 in CRC metastasis [25, 26], but their identifications of target genes were based on very small samples. The present study is based on the screening of methylation markers in a large clinical population and cg24067911 locus was found to have both diagnostic and metastasis-predictive value in CRC [9].

Drugs that target DNA methylation, such as 5-azacytidine and decitabine, have been used in the treatment of hematological malignancies [27]. Other epigenetic drugs have also shown promising results for CRC in preclinical studies and early clinical trials [28]. These agents can reverse aberrant DNA methylation patterns, reactivating tumor suppressor genes and restoring normal gene expression, thereby inhibiting tumor growth and enhancing the effectiveness of conventional chemotherapies [29]. However, these drugs have limitations in terms of specificity and efficacy, especially in solid tumor. Of late, the study of DNA methylation has experienced a paradigm shift with the advent of CRISPR-based tools for manipulating DNA methylation patterns. The applications of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing system, which contained a CRISPR guide and a Cas9 endonuclease, had sprung up to step up efforts for targeted cancer therapy [30]. Cas9 protein with mutational inactivation of nuclease structure domain loses its endonuclease catalytic activity (dCas9), while the ability to bind to specific DNA sites through single guide RNA (sgRNA) is retained [9]. Epigenetic modulators, such as DNA methyltransferase 3a (DNMT3a) and Ten-eleven translocation 1 (Tet1), could be fused with dCas9 protein to modify DNA methylation levels. In addition, once ligated to appropriate sgRNA that determines dCas9 location, the sgRNA-dCas9-EE complexes could serve as variable genome modification tools and an emerging form of precision cancer therapy. The employment of CRISPR/dCas9-Dnmt3a-mediated DNA methylation editing system has been used to modulate targeted DNA methylation and gene expression efficiently. In a study, hypomethylation of the amyloid precursor protein gene (APP) in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) was reversed by the dCas9-Dnmt3a combined with sgRNAs targeting the APP promoter region, subsequently with reduction in APP expression, resulting in reduced Aβ levels [31]. In addition, the in vivo model with dCas9-Dnmt3a lentivirus microinjection validated the induction of APP hypermethylation and subsequent suppression of APP expression in the mouse brain, and contributed to better performance in behavior test, which indicated the utilization of dCas9-Dnmt3a treatment in AD therapeutic strategy. As for the application of in cancer, the system has been proved to target remarkable cancerous epigenetic alterations efficiently [32,33,34,35]. Through robust analysis, cg24067911 was found to be located in the enhancer region of ATXN1. Using the CRISPR/dCas9-DNMT3a editing system, we found that cg24067911 could influence CRC invasion by regulating the expression of ATXN1.

Although our targeted methylation approach achieved promise modification efficiency, this observation is consistent with recent reports highlighting the technical challenges of locus-specific epigenetic editing in enhancer regions. The incomplete methylation likely stems from chromatin accessibility barriers, as the BCL6-bound enhancer’s native open configuration may resist DNMT3A-mediated methylation, compounded by potential histone modification crosstalk where EZH2-mediated H3K27me3 - known to interact with DNMTs - could maintain this region’s epigenetic memory. Previous studies have shown that ATXN1 is capable of regulating EMT in a Notch-dependent manner [11, 36]. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is one of the most important processes in cancer metastasis [37, 38]. “Cadherin switching”, which is known as the loss of E-cadherin and gain of N-cadherin, is a hallmark of EMT in cancers [39]. N-cadherin, a cell adhesion molecule that is predominantly expressed in mesenchymal cells, is often observed in cells undergoing EMT, resulting in a loss of epithelial characteristics and acquisition of a mesenchymal phenotype [40]. Upregulated expression of N-cadherin has been reported to be associated with malignant progression and be indicative of a transition towards a more invasive phenotype [41, 42]. Although N-cadherin has been well-known to be involved in EMT and cancer metastasis, the epigenetic mechanism of N-cadherin modulation is not fully understood. Our present study reveals that cg24067911 methylation downregulates the expression of ATXN1, which is found to be a transcription factor of CDH2, thus leading to the upregulation of N-cadherin that promotes EMT of CRC cells and weakens the intercellular adhesion, contributing to CRC metastasis. The recurrent hypomethylation at cg24067911 in CRC pathogenesis likely stems from multifaceted mechanisms, where field cancerization may initiate early demethylation in premalignant epithelium to create permissive chromatin for subsequent oncogenic hits, while concurrent BCL6-ATXN1 axis dysregulation could stabilize BCL6 binding (Fig. 2) through methylation loss, forming a feedforward loop that perpetuates ATXN1 suppression. Clinically, these methylation dynamics hold dual promise: as a liquid biopsy-based early detection biomarker through longitudinal monitoring, and as a therapeutic vulnerability where EZH2 inhibitors could potentially disrupt BCL6 dependency.

The research derives from a large cohort analysis and conducts in vitro and in vivo experiments to mechanistically verify the role of cg24067911 methylation. Our findings reveals that the hypomethylation of cg24067911 in CRC enhances the binding to BCL6, which gives rise to the upregulation of ATXN1 and subsequent promotes EMT. Further studies are in need to evaluate the potential of clinical application of CRISPR/dCas9-DNMT3a on cg24067911 to CRC.

Data availability

The raw ATAC-seq and RNA-seq data have been deposited at Database Commons (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/databasecommons/) with accession number HRA009196, according to the requirements of the Human Genetic Resource Administration of China. Requests for the access are available from the lead contact on the basis of availability and scientific merit within the parameters of participant permission, study ethics approvals, and data governance. The public CRC data can be downloaded from TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) including RNA-seq data, 450 K methylation data and clinical data of COAD and READ cohort; and Oncomine database (https://www.oncomine.org/resource/) including RNA-seq data of colorectal cancer reported by Kaiser and Skrzypczak. The public ChIP-seq data can be accessible from UCSC Genome Browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu/) and WASHU EPIGENOME Browser (https://epigenomegateway.wustl.edu/) under accession number ENCSR661KMA, ENCFF225QAB, ENCSR161MXP, ENCFF285DIL. To predict the TFs correlated with the methylation level of cg24067911 and the expression of ATXN1, JASPAR database online (https://jaspar.elixir.no/), GeneHancer database (GH06J016720) and RNA-seq data of TCGA COAD and READ cohort were carried out to screen. The protein-protein interaction analysis was performed online by STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/). All the data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

The raw ATAC-seq and RNA-seq data have been deposited at Database Commons (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/databasecommons/) with accession number HRA009196, according to the requirements of the Human Genetic Resource Administration of China. Requests for the access are available from the lead contact on the basis of availability and scientific merit within the parameters of participant permission, study ethics approvals, and data governance. The public CRC data can be downloaded from TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/) including RNA-seq data, 450 K methylation data and clinical data of COAD and READ cohort; and Oncomine database (https://www.oncomine.org/resource/) including RNA-seq data of colorectal cancer reported by Kaiser and Skrzypczak. The public ChIP-seq data can be accessible from UCSC Genome Browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu/) and WASHU EPIGENOME Browser (https://epigenomegateway.wustl.edu/) under accession number ENCSR661KMA, ENCFF225QAB, ENCSR161MXP, ENCFF285DIL. To predict the TFs correlated with the methylation level of cg24067911 and the expression of ATXN1, JASPAR database online (https://jaspar.elixir.no/), GeneHancer database (GH06J016720) and RNA-seq data of TCGA COAD and READ cohort were carried out to screen. The protein-protein interaction analysis was performed online by STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/). All the data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Morgan E, Arnold M, Gini A, Lorenzoni V, Cabasag CJ, Laversanne M, et al. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut. 2023;72:338–44.

Biller LH, Schrag D. Diagnosis and treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: a review. JAMA. 2021;325:669–85.

Zhao J, Jiang O, Chen X, Liu Q, Li X, Wu M, et al. Development and validation of a prediction model for metastasis in colorectal cancer based on LncRNA CRNDE and radiomics. 2022. 1:e6.

Zhang Q, Xu Y, Kang S, Chen J, Yao Z, Wang H et al. A novel computational framework for integrating multidimensional data to enhance accuracy in predicting the prognosis of colorectal cancer. 2022. 1:e27.

Shin AE, Giancotti FG, Rustgi AK. Metastatic colorectal cancer: mechanisms and emerging therapeutics. Trends Pharm Sci. 2023;44:222–36.

Su R, Wu X, Tao L, Wang C. The role of epigenetic modifications in Colorectal Cancer Metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2022;39:521–39.

Koch A, Joosten SC, Feng Z, de Ruijter TC, Draht MX, Melotte V, et al. Analysis of DNA methylation in cancer: location revisited. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15:459–66.

Ju HX, An B, Okamoto Y, Shinjo K, Kanemitsu Y, Komori K, et al. Distinct profiles of epigenetic evolution between colorectal cancers with and without metastasis. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:1835–46.

Rahman MM, Tollefsbol TO. Targeting cancer epigenetics with CRISPR-dCAS9: Principles and prospects. Methods. 2021;187:77–91.

Luo H, Zhao Q, Wei W, Zheng L, Yi S, Li G, et al. Circulating tumor DNA methylation profiles enable early diagnosis, prognosis prediction, and screening for colorectal cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12:eaax7533.

Tong X, Gui H, Jin F, Heck BW, Lin P, Ma J, et al. Ataxin-1 and Brother of ataxin-1 are components of the Notch signalling pathway. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:428–35.

Ju H, Kokubu H, Lim J. Beyond the glutamine expansion: influence of posttranslational modifications of ataxin-1 in the pathogenesis of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;50:866–74.

Xie M, Swanson MS. UTteR control through miRs: fine-tuning ATXN1 levels to prevent ataxia. Genes Dev. 2020;34:1107–9.

Suh J, Romano DM, Nitschke L, Herrick SP, DiMarzio BA, Dzhala V, et al. Loss of Ataxin-1 Potentiates Alzheimer’s Pathogenesis by Elevating Cerebral BACE1 Transcription. Cell. 2019;178:1159–45.e17.

Tost J, Gut IG. DNA methylation analysis by pyrosequencing. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2265–75.

Taylor KH, Kramer RS, Davis JW, Guo J, Duff DJ, Xu D, et al. Ultradeep bisulfite sequencing analysis of DNA methylation patterns in multiple gene promoters by 454 sequencing. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8511–8.

Ju HQ, Lu YX, Chen DL, Tian T, Mo HY, Wei XL, et al. Redox Regulation of Stem-like Cells Though the CD44v-xCT Axis in Colorectal Cancer: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Theranostics. 2016;6:1160–75.

Fishilevich S, Nudel R, Rappaport N, Hadar R, Plaschkes I, Iny Stein T, et al. GeneHancer: genome-wide integration of enhancers and target genes in GeneCards. Database (Oxford). 2017;2017:bax028.

Bian S, Hou Y, Zhou X, Li X, Yong J, Wang Y, et al. Single-cell multiomics sequencing and analyses of human colorectal cancer. Science. 2018;362:1060–3.

Walther A, Johnstone E, Swanton C, Midgley R, Tomlinson I, Kerr D. Genetic prognostic and predictive markers in colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:489–99.

Schweiger MR, Hussong M, Röhr C, Lehrach H. Genomics and epigenomics of colorectal cancer. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2013;5:205–19.

Gu S, Lin S, Ye D, Qian S, Jiang D, Zhang X, et al. Genome-wide methylation profiling identified novel differentially hypermethylated biomarker MPPED2 in colorectal cancer. Clin Epigenet. 2019;11:41.

Rezayi Soufiani A, Dolatkhah R, Raeisi M, Chavoshi H, Mohammadi P, Mehdinavaz Aghdam A. Hypermethylation of MIR129-2 Regulates SOX4 Transcription and Associates with Metastasis in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2022;53:718–24.

Ili C, Buchegger K, Demond H, Castillo-Fernandez J, Kelsey G, Zanella L, et al. Landscape of genome-Wide DNA methylation of colorectal cancer metastasis. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:2710.

Zhang K, Zhai Z, Yu S, Tao Y. DNA methylation mediated down-regulation of ANGPTL4 promotes colorectal cancer metastasis by activating the ERK pathway. J Cancer. 2021;12:5473–85.

Shuai W, Wu J, Chen S, Liu R, Ye Z, Kuang C, et al. SUV39H2 promotes colorectal cancer proliferation and metastasis via tri-methylation of the SLIT1 promoter. Cancer Lett. 2018;422:56–69.

Pappalardi MB, Keenan K, Cockerill M, Kellner WA, Stowell A, Sherk C, et al. Discovery of a first-in-class reversible DNMT1-selective inhibitor with improved tolerability and efficacy in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Cancer. 2021;2:1002–17.

Rezapour S, Hosseinzadeh E, Marofi F, Hassanzadeh A. Epigenetic-based therapy for colorectal cancer: Prospect and involved mechanisms. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:19366–83.

Peng PL, Qin SY, Lei L, He ZJ, Li BW, Edouard N, et al. Epigenetic remodeling under oxidative stress: mechanisms driving tumor metastasis. MedComm – Oncol. 2024;3:e70000.

Wang SW, Gao C, Zheng YM, Yi L, Lu JC, Huang XY, et al. Current applications and future perspective of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2022;21:57.

Park H, Shin J, Kim Y, Saito T, Saido TC, Kim J. CRISPR/dCas9-Dnmt3a-mediated targeted DNA methylation of APP rescues brain pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Transl Neurodegener. 2022;11:41.

Wang H, Guo R, Du Z, Bai L, Li L, Cui J, et al. Epigenetic Targeting of Granulin in Hepatoma Cells by Synthetic CRISPR dCas9 Epi-suppressors. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2018;11:23–33.

Sarno F, Goubert D, Logie E, Rutten MGS, Koncz M, Deben C, et al. Functional Validation of the Putative Oncogenic Activity of PLAU. Biomedicines. 2022;11:102.

Lu H, Zhang Q, He S, Liu S, Xie Z, Li X, et al. Reduction-Sensitive Fluorinated-Pt(IV) Universal Transfection Nanoplatform Facilitating CT45-Targeted CRISPR/dCas9 Activation for Synergistic and Individualized Treatment of Ovarian Cancer. Small. 2021;17:e2102494.

Elumalai P, Ezhilarasan D, Lakshmi T. Targeting head and neck cancer epigenetics with CRISPR-dCas9: An emerging therapeutic approach. Oral Oncol. 2022;127:105801.

Kang AR, An HT, Ko J, Kang S. Ataxin-1 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition of cervical cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:18248–59.

Khan SU, Fatima K, Malik F, Kalkavan H, Wani A. Cancer metastasis: Molecular mechanisms and clinical perspectives. Pharm Ther. 2023;250:108522.

Tao L, Zhou Y, Qiu JH, Xiao YZ, Zou J, Zhang Y, et al. Epigenetic regulation in cancer therapy: from mechanisms to clinical advances. MedComm – Oncol. 2024;3:e59.

Nakajima S, Doi R, Toyoda E, Tsuji S, Wada M, Koizumi M, et al. N-cadherin expression and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4125–33.

Serrano-Gomez SJ, Maziveyi M, Alahari SK. Regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition through epigenetic and post-translational modifications. Mol Cancer. 2016;15:18.

Ye Z, Zhou M, Tian B, Wu B, Li J. Expression of lncRNA-CCAT1, E-cadherin and N-cadherin in colorectal cancer and its clinical significance. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:3707–15.

Yan X, Yan L, Liu S, Shan Z, Tian Y, Jin Z. N-cadherin, a novel prognostic biomarker, drives malignant progression of colorectal cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:2999–3006.

Acknowledgements

We thank the authors who shared their data with publicly available databases. We also appreciated the patients who generously provided their samples for this research. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82273402, 92374114 and 82203480), the Science and Technology Program of Guangdong (2019B020227002), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2024A1515012888, 2014A030312015 and 2019A1515011109), the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (202002030208 and 202206080008), Guangdong Institute of Esophageal Cancer Science and Technology Program Project (M202109), Young Talents Program of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (YTP-SYSUCC-0084).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Hui-Yan Luo and Rui-Hua Xu had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Lu-Ping Yang, Jia-Qian Huang, Chiu-Wing Yeung, Qi-Hua Zhang and Xiao-Li Wei contributed equally to this work as co-first authors. Conceptualization, HL, RX and LY; Methodology, Validation and Visualization, LY, JH, CY, QZ, QW, ZQ, LZ and DH; Software, LY, ZQ, YZ and ZZ; Formal Analysis and Data Curation, LY, JH, CY, XW, YZ, QZ and ZZ; Investigation, LY, YX, KZ, MY and ZY; Resources, QW, YZ and ZZ; Writing - Original Draft: LY, JH, CY, and XW; Writing - Review & Editing: HL, RX, JL, LY, JH, CY, XW, and QZ; Supervision, Project Administration and Funding Acquisition, JL, HL and RX.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, LP., Huang, JQ., Yeung, CW. et al. Targeted methylation of cg24067911 suppresses colorectal cancer metastasis through BCL6-ATXN1-CDH1 axis. Oncogene 45, 295–306 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-025-03638-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-025-03638-z