Abstract

Background

Early identification of children at risk for metabolic syndrome (MetS) can reveal traits linked to cardiometabolic disease. We aimed to develop a simple, user-friendly tool to detect pediatric cardiometabolic risk using clinical, nutritional, and lifestyle data.

Methods

A total of 317 patients (11.35 ± 3.62) were assessed using clinical, dietary, and biochemical data. Metabolic risk was defined by a MetS z-score >0.75, and MetS diagnosis required at least three altered parameters (body composition, blood pressure, glucose, lipids). A 22-variable binary tool generated a cumulative risk score: ≥7 altered components indicated high risk; otherwise, low risk.

Results

A pathological MetS-score was found in 62.15% of subjects, while MetS was diagnosed in 39.4%. The MetS z-score was significantly correlated with MetS prevalence (r = 0.581). When considering a screening tool score ≥7, along with patients presenting at least 3 of 4 altered MetS parameters, the results demonstrated good sensitivity (0.768 [0.715, 0.835]), negative predictive value (0.775 [0.702, 0.848]), and accuracy (0.618 [0.564, 0.672]), though specificity (52.1% [0.420, 0.600]) and positive predictive value (0.511 [0.439, 0.582]) were moderate.

Conclusion

A score ≥7 reliably identifies children at cardiometabolic risk, providing a sensitive, non-invasive tool that supports early detection, prevention, and personalized care while reducing time and healthcare costs.

Impact

-

Early detection of at-risk children can uncover cardio-metabolic traits.

-

A 22-noninvasive variable tool was developed to identify pediatric cardio-metabolic risk.

-

A score ≥7 effectively identifies children at cardiometabolic risk.

-

The proposed non-invasive tool achieves good sensitivity (76.8%) and moderate specificity (52.1%).

-

The tool supports clinicians in prevention, monitoring, and personalized care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-communicable diseases pose a significant public health challenge in pediatrics, both now and in the future.1 The pediatric population represents the cornerstone of life-course approaches for the prevention, management, and treatment of NCDs.1,2

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) arises from a combination of risk factors that begin in the prenatal period and continue through childhood and adulthood3 Specifically, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) classifies CVD risk factors into two main categories: non-modifiable (such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, familial and genetic predispositions, congenital conditions, and socioeconomic status) and modifiable factors. The latter can be further divided into cardiometabolic factors (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia) and lifestyle factors (e.g., physical inactivity, poor diet, and obesity).4,5

While CVD and T2D are uncommon during childhood, early risk factors are often identifiable from a young age. The progression toward these conditions occurs along a continuum, becoming more pronounced as risk factors accumulate.6 These factors often interact and amplify one another, progressively leading to metabolic derangement, endothelial damage, vascular and myocardial remodeling, and the onset of atherosclerotic processes.4 Therefore, early detection of these interconnected variables, along with timely intervention on modifiable risk factors, is crucial to protecting pediatric health.

Early identification of children at risk for metabolic syndrome (MetS) can reveal individual traits linked to cardio-metabolic disease development and treatment outcomes.7,8 MetS refers to a combination of cardio-metabolic risk factors, including visceral obesity, high blood pressure, abnormal lipid levels, and impaired glucose regulation, that collectively heighten the risk of CVD and T2D.9 Its prevalence in youth varies widely, from 0.2% to 38.9%, and is estimated at 3.3% in the general pediatric population. Rates increase significantly in those with excess weight: 11.9% in children with overweight and 29.2% in those with obesity.10 The condition often reflects obesity trends, especially in high-income countries, and its distribution also depends on variables like age, sex, ethnicity, and diagnostic standards used.

Although there is consensus on the distinctive features of MetS, no international diagnostic criteria currently exist for the pediatric population.11 Recently, Gurka et al.12 proposed a metabolic score (MetS z-score) as a highly sensitive and specific tool for detecting risk markers of MetS, which was also found to be strongly associated with the incidence of T2D.13 The MetS z-score is a dynamic index useful for monitoring changes over time within a population and for identifying differences in the rate of change based on clinical status.

Several tools have been proposed to screen metabolic disorders in children, ranging from simple anthropometric indices (e.g. waist circumference or waist-to-height ratio) to more complex composite index (e.g. visceral adiposity index or body shape index, triponderal mass index, conicity index).14,15,16,17 Although simple anthropometric indices can provide useful information, their accuracy is limited because they mainly capture current body size and adiposity, without considering the metabolic and environmental factors that shape long-term cardiometabolic risk. Early-life influences, including parental health status, intrauterine environment, and fetal growth patterns, play a pivotal role in these processes6,11,18,19 and may not be reflected in conventional anthropometric measures. Accounting for early-life and contextual factors enhances risk estimation by capturing latent susceptibilities and developmental influences beyond cross-sectional body measurements. An integrated approach thus allows for more accurate and individualized cardiometabolic risk stratification, particularly during growth and maturation.

The aim of this study was to develop a simple, practical, and user-friendly tool to detect at cardio-metabolic risk (CMR) pediatric patients based on clinical features, medical history, nutrition, and lifestyle behaviors. We used the MetS z-score to stratify at-risk patients and the prevalence of MetS to assess the accuracy of the tool in detecting it. A high-quality risk score for cardiometabolic disorders in toddlers and young children could significantly improve awareness and enhance the guidance pediatricians offer to both parents and children to prevent CVD and to personalize care and promote every child’s right to health.

Methods

Study design

The study is a cross-sectional analysis, part of the “Fight against Pediatric Obesity: from a predictive tool for type 2 Diabetes and Cardiovascular diseases risk to healthy educational programs (PODiaCar)” european project (101128946-PODiaCar-EU4H-2022-PJ-3). PODiaCar (www.podiacar.eu) is a project aimed at addressing childhood obesity and its related complications, such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. It through multidisciplinary collaboration and digital innovation promotes a proactive, data-driven approach to child health and disease prevention. The project aligns with the European Commission’s “Healthier Together” initiative, targeting significant non- communicable diseases (NCDs) and is an initiative within the strategic framework of the European Digital and Health Executive Agency (HaDEA). The project team is composed of Buzzi’s Children Hospital, Milano, Italy (coordinator); University of Pavia, Pavia (Italy); University of Granada, Granada, Spain; Asomi College of Sciences, Marsa, Malta; LUNEX International University of Health, Exercise and Sports, Differdange, Luxembourg.

The study protocol received approval from the Ethics Committee of Lombardia 1 (protocol number CET 202–2023). It was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Before participation, both children and their parents were thoroughly informed about the study’s aims and procedures. Verbal and/or written assent was obtained from the children according to age, while written informed consent was signed by their parents or legal guardians.

Participants

We consecutively included 317 patients (aged between 3 and 18 years) of both sexes who were referred to the Vittore Buzzi Children’s Hospital (Milano, Italy) and University of Granada (Granada, Spain) by their general practitioner or primary care pediatrician for auxological assessment related to weight management, between November 2023 and March 2025.

Exclusion criteria were any genetic syndromes known to be usually associated with obesity (e.g., Prader–Willi, Bardet–Biedl), any ongoing medical therapy, and concomitant chronic or acute illnesses.

Historical data, clinical evaluation, dietary patterns, and biochemical profiles were considered for all participants to create the screening tool and define the MetS severity z-score and MetS prevalence. To minimize potential bias during evaluations and data collection, study staff provided comprehensive guidance to all individuals responsible for assessing outcomes.

Historical data

Evaluation of the anamnestic data include:

-

Family history, assessed through interview with the parents, was considered positive when the presence of obesity in parents and diabetes mellitus and hypertension in parents and grandparents were reported.

-

Socioeconomic status, determined according to parents’ level of education, occupation, and income.

-

Maternal age, cardio-metabolic conditions (diabetes, obesity, hypertension) and maternal weight gain during pregnancy.

-

Type of delivery (vaginal or cesarean section)

-

Maternal and/or paternal exposure to environmental factors during pregnancy (smoke, alcohol consumption, stress, environmental disruptors)

-

Neonatal data. On the basis of gestational age and birth weight, the children were defined appropriate for gestational age with a birth weight ≥10th percentile, small for gestational age with a birth weight <10th percentile, and large for gestational age with a birth weight >90th.20

-

Early life nutritional data (breast/formula/cow’s milk; timing of complementary feeding).

-

Infants’ antibiotics exposure.

-

Inappropriate bottle use, defined as children over 12 months of age drinking ≥2 bottle-type containers/day.

-

Sleep duration, assessed according to age-specific WHO guidelines.21

-

Physical activity level and/or sedentariness, assessed according to age-specific WHO guidelines.21

Clinical evaluation

In all participants, height (Ht), weight, pubertal stage, waist circumference (WC), WC/Ht, body mass index (BMI) were recorded. Systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP) blood pressure measurements were also collected.

Standing Ht was assessed using a Harpenden stadiometer equipped with a fixed vertical backboard and an adjustable headpiece. The measurement was taken with the subject standing upright without shoes, heels together, toes apart, hands relaxed at their sides, and the head aligned in the Frankfort horizontal plane. Weight was recorded with participants wearing light clothing and no shoes, standing in the center of the scale platform while facing the recorder, with hands at their sides and eyes directed forward. Two measurements were obtained for each parameter, and a third measurement was taken if the difference between the initial readings exceeded 0.5 cm for Ht or 500 g for weight.

WC was measured in accordance with WHO guidelines, in the horizontal plane midway between the lowest ribs and the iliac crest.

Pubertal stage was clinically assessed according to Tanner’s criteria. Participants were classified into three groups: prepubertal (stage 1 = Tanner 1), middle puberty (stage 2 = Tanner 2–3), and late puberty (stage 3 = Tanner 4–5). Clinical evaluation of pubertal status was performed by trained physicians through inspection and palpation of secondary sexual characteristics (breast development in girls, genital development in boys, and pubic hair in both sexes). Pubertal development was included in the score as it represents a critical stage marked by transient insulin resistance and the combined influence of increased adiposity, hormonal changes, and metabolic alterations, all contributing to heightened cardiometabolic risk. Pubertal progression is closely linked to the consolidation of MS,22 making this stage a key window to improve risk stratification and to guide preventive interventions in the pediatric population.

BMI was calculated as body weight (kilograms) divided by Ht (meters squared) and was transformed into BMI z-scores using WHO reference values.

Blood pressure (BP) was assessed using a mercury sphygmomanometer after the participant had been seated comfortably for five minutes. An appropriately sized cuff was placed on the slightly flexed right arm at heart level, and two consecutive measurements were taken. The second reading was used for analysis.

Assessment of dietary and lifestyle patterns

To assess adherence to the Mediterranean dietary pattern, the KIDMED Mediterranean Diet Quality Index questionnaire was administered. This tool consisted of 16 self-administered questions evaluating individuals’ dietary habits in relation to the Mediterranean diet. The KIDMED index provided a score ranging from 0 to 12, reflecting the level of adherence to the diet. Based on the total score, individuals were classified into three categories: (a) ≥8: optimal adherence to the Mediterranean diet (good); (b) 4–7: moderate adherence, indicating the need for dietary improvement (average); (c) ≤3: poor adherence, indicating very low diet quality (poor).23

Information on physical activity and sleep duration was obtained during the clinical anamnesis focused on children’s lifestyle, as reported by parents and/or caregivers. Data were then categorized according to the WHO age-specific guidelines21 for sleep and physical activity.

Biochemical evaluation

Plasma glucose, insulin, triglycerides (TG), total, LDL and HDL cholesterol levels were evaluated. As a surrogate of insulin resistance (IR), homeostasis model analysis—insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) index and Triglyceride–glucose (TyG) index were calculated as following.

-

-HOMA-IR24 = (insulin × glucose)/22.5;

-

-TyG-index25= ln[fasting triglycerides (mg/dl)×fasting plasma glucose (mg/dl)/2]).

Dyslipidemia was defined by TC > 200 mg/dl and/or LDL-C > 130 mg/dl and/or TG > 150 mg/dl.26

To test the risk of MetS, we computed the MetS z-score as proposed by Gurka et al.12. Children were considered having MetS if the MetS z-score was higher than 0.75.

The formula to assess the MetS z-score is presented below:

Boys: MetS z-score = −4.931 + 0.2804 * BMI z-score - 0.0257 * HDL-C + 0.0189 * Systolic blood pressure +0.6240 * log(triglycerides) + 0.0140 * fasting glucose

Girls: MetS z-score = −4.3757 + 0.4849 * BMI z-score - 0.0176 * HDL-C + 0.0257 * Systolic blood pressure + 0.3172 * log(triglycerides) + 0.0083 * fasting glucose

The MetS z-score proposed by Gurka et al.12 offers several operational and methodological advantages over other scores, such as the IDEFICS score by Ahrens.27 It is derived via confirmatory factor analysis, yielding data-driven weights for each component (WC, triglycerides, HDL-C, BP, fasting glucose) and sex- and ethnicity-specific equations, which improves construct validity and comparability across subgroups. Practically, it does not require insulin, making it easier to apply where insulin is not measured. In addition, the Gurka score has shown longitudinal associations with future cardiometabolic outcomes, enabling continuous tracking of MetS severity over time.28,29

As previously reported,30,31 MetS was defined as the presence of at least three of the following risk factors:

-

BMI z score ≥2 and/or WC/Ht >0.515;

-

SBP ≥ 130 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 85 mmHg32;

-

glycemia ≥ 100 mg/dL and/or HOMA-IR24 ≥ 2.5 if prepubertal stage 1 o ≥ 4 if pubertal stage 2, 3 and/or TryG index>7.8825;

-

total cholesterol >200 mg/dl and/or cholesterol-HDL < 40 mg/dL in females and <50 mg/dL in males and/or triglycerides ≥ 100 mg/dL ( < 10 years) or ≥130 mg/dL ( ≥ 10 years).26

We used a pre-specified pediatric MetS definition based on fixed, clinically interpretable thresholds, rather than the percentile-based algorithms used for certain parameters in other pediatric classifications,33,34,35,36 to improve feasibility and cross-cohort comparability. In addition, because our cohort includes participants aged 3–18 years, frameworks restricted to narrower age bands (e.g., the International Diabetes Federation definition,33 for which a formal diagnosis is limited to 10–16 years; Cook et al.35 an adaptation of the National Centers for Environmental Prediction definition applied to adolescents aged 12–19 years; Ferranti et al36 developed using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data from adolescents aged 12–19 years) or derived from selected samples (e.g., the definition by Viner et al.37 is based on only 103 patients with obesity) or adults38,39,40 are suboptimal. Beyond BMI, we preferred to use the WHtR because it effectively identifies cardiometabolic risk in children15 and, compared with waist circumference alone, better tracks changes in abdominal adiposity during adolescence.41 Regarding glucose metabolism, since insulin resistance typically precedes overt dysglycemia in pediatric populations, we included HOMA-IR and/or the TyG index alongside fasting glucose.9,11 We did not use OGTT-based classification owing to the time burden, the limited reproducibility of the 2-hour glucose value in pediatrics, and its poor applicability in routine or large-scale settings.42 The euglycemic–hyperinsulinemic clamp remains the reference method for assessing insulin resistance; however, its invasive nature, time requirements, and complexity limit its use in pediatric practice.

CMR screening score tool

Data based on 22 variables were used to create a tool for CMR assessment. Each parameter represents a dichotomous variable: for each of them, criteria have been defined to assign a score of 1 for a pathological situation or 0 for a normal condition, see Table 1 (score calculator in Supplementary Material 1).

The cumulative risk factors were summed to obtain a total risk score. To dichotomize the population, we selected a cut-off of seven dysregulated components, as this threshold corresponded to the median number of dysregulated components observed in individuals exhibiting a pathological MetS z-score. The median was selected as it represents a robust measure of central tendency, minimizes the influence of outliers, and ensures a balanced distribution of participants across risk groups. Accordingly, participants with ≥7 dysregulated components were classified as high risk, while those with fewer than 7 components were categorized as low risk.

Statistical analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of quantitative variables. Since the quantitative variables followed a normal distribution, results were reported as mean values with standard deviations (SD). Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, and group comparisons were conducted using the unpaired t-test. In order to evaluate the relationship between the presence of a certain number of pathological variables and the MetS, a contingency table was constructed. As two dichotomous variables were considered, the tool score above/below the median and the presence or absence of at least 3 altered parameters characteristic of the MetS. To evaluate the level of significance through the contingency tables between these variables, the χ2-square test was used. To evaluate the tool’s accuracy in detecting MetS, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), accuracy, and likelihood ratios (LR) were calculated. Data analysis included the 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

Sample size and power calculations were performed a priori. Assuming a prevalence of 3.3% in the general pediatric population and 11.9% among children with overweight,10 with 95% power and a two-sided alpha of 0.05, the minimum sample size required was 243 participants. Given that our study included 317 children, the achieved statistical power under the same assumptions was greater than 99%.

All statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel, with additional specific extensions (e.g., the Solver add-in) and advanced data analysis features enabled through the Data Analysis ToolPak.

Results

We enrolled 317 patients (11.35 ± 3.62 years, range 2.95–17.62 years). Among them, 177 (55.83%) were males, and 140 (44.17%) were females. In Table 2, values of clinical parameters and biochemical data are reported.

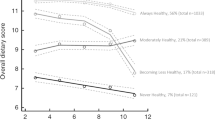

A pathological level of MetS-score was noted in 197 (62.15%) subjects. These subjects showed a median of 7 pathological parameters included in CMR score.

The distribution of the variables and the number of the pathological parameters included in the CMR score, are reported in Table 3 and Fig. 1, respectively.

As expected, a statistically significant difference was found between the two groups of patients with a high or low CMR score for the following parameters: WC (p = 0.007), BMI (p < 0.001), SBP (p = 0.004) and DBP (p < 0.001), and all metabolic parameters except for total and LDL cholesterol (p > 0.05), Table 4.

The prevalence of MetS was 39.4%. In Fig. 2, the number of MetS parameters was reported.

The MetS severity z-score was correlated with the prevalence of MetS (Pearson’s r = 0.581). Linear association between the CMR tool and MetS severity z-score indicate a fair positive correlation (Pearson’s r = 0.334), suggesting that while the tool is useful for distinguishing the presence or absence of the condition, it is less sensitive to gradual variations in metabolic risk.

When considering a screening tool score over/above the median value of 7, along with patients presenting at least 3 out of 4 altered parameters of the MetS, the results demonstrated good sensitivity (76.8%), NPV (77.5%), accuracy (61.8%). However, specificity (52.1%), PPV (51.1%), +LR (1.603) and -LR (0.445) presented more limited performance. Table 5 presents all key diagnostic metrics of CMR tool along with their corresponding confidence intervals (CI). The diagnostic performance of the individual parameters included in the CMR assessment is reported in the Supplementary Material (Table S1).

The AUROC of screening tool score upon detection of cumulative biological dysregulation (pathological if at least 3 over 4 altered parameters) was 0.645 (95% CI 0.592–0.698).

Discussion

We proposed a score to detect CMR in children and adolescents, based on their medical history, clinical characteristics, and lifestyle behaviors. A score ≥7 identified at-risk individuals and demonstrated good sensitivity in detecting MetS in the pediatric population. Despite its relatively limited sensitivity in this population, the tool nonetheless appears to hold considerable potential. It represents a non-invasive approach for the early identification of children at risk of cardiometabolic dysfunction, and may support both preventive strategies and personalized diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.

MetS is widely recognized as a significant risk factor for the development of both CVD and T2DM.43,44,45 Characterized by a cluster of interrelated conditions, such as central obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and insulin resistance, MetS reflects a state of heightened metabolic dysfunction. Their constellation of abnormalities not only increases the likelihood of atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction, which are key contributors to cardiovascular events, but also accelerates the progression from IR to overt diabetes.9

During childhood and adolescence, increased fat mass together with hormonal and metabolic changes of puberty, such as heightened insulin resistance, contribute to the risk of developing MetS. As highlighted by de Lamas et al.22 pubertal progression is strongly associated with the consolidation of MS, and most children with early-onset MetS remain affected during puberty, markedly raising their likelihood of adult obesity, diabetes, and CVD.

As highlighted by Gurka et al.12 standard diagnostic definitions for MetS have certain limitations, as they only classify individuals as at-risk when specific thresholds are exceeded. This binary approach overlooks the idea that MetS may represent a continuum of risk. In fact, individuals with values just below the threshold in all five components might face a higher risk than those who exceed criteria in three components but have normal levels in the others. To address this, Gurka et al.12 proposed continuous MetS severity scores, enabling the monitoring of trends over time and the detection of variations based on clinical status. Several studies have demonstrated that these continuous scores correlate with unhealthy behaviors and elevated cardiovascular and metabolic risk.46,47,48 Moreover, they are associated with early markers of disease, including abnormal insulin and glucose levels, in both children and adults.28,29

In our pediatric population, pathological levels of the MetS severity z-score were observed in 62.15% of subjects. The MetS was correlated with the prevalence of MetS (r = 0.581), which was confirmed by the presence of at least three risk factors exceeding the age- and sex-specific thresholds, detected in 39.4% of participants.

These prevalence data are consistent with the recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Porchia et al.49 which analyzed 57 studies including a total of 27.923 participants. The overall prevalence of MetS among individuals with obesity varied widely across studies, ranging from 2.1% to 74.4%, with an average prevalence of 29.4%.

These alarming data underscore the urgent need for increased awareness and action regarding this issue.

Given the significant resources and time involved in diagnosing MetS, conducting large-scale screenings is often unfeasible. As a result, there has been a shift toward more practical and affordable methods, such as self-reported questionnaires. These tools are advantageous because they are straightforward to use, require minimal time, eliminate the need for blood samples or trained personnel, and incur lower costs.

Among adults, many self-administered questionnaires have demonstrated strong predictive performance. For instance, the American Diabetes Association created a tool50 to assess the likelihood of developing T2D, showing reasonable agreement with clinical diagnoses (sensitivity 79%; specificity 65%). In Greece, the Finnish diabetes risk score (FINDRISC)51 was found to effectively detect MetS with high sensitivity (89%–98%), though specificity remained low (14%–37%).

Considering that the development of chronic cardiometabolic diseases results from the combination of risk factors across prenatal, childhood, and adulthood stages, we proposed a tool for the pediatric population that takes into account both modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for the development of MetS, CVD, and T2D.

Our results show that, although the proposed score achieves good sensitivity (76.8%) and a satisfactory PNV (77.5%), specificity (52.1%) and positive predictive value (51.1%) remain moderate, leading to a non-negligible number of false positives. While this represents a limitation for its use as a diagnostic or confirmatory test, as it is less sensitive to gradual variations in metabolic risk, it does not diminish the potential value of the tool as a simple, non-invasive first-level screening aid, designed to maximize the identification of at-risk individuals without requiring blood tests, while minimizing missed cases. The moderate discriminatory ability (AUROC 0.645) further underscores its value, not as a definitive diagnostic tool but rather as a first-level risk assessment for stratifying the pediatric population and identifying individuals who may benefit from further evaluation through blood testing, thereby reducing unnecessary consultations and costs while facilitating earlier diagnosis. However, in cases where MetS is already suspected, this tool is not intended to replace medical consultations or follow-up assessments, but rather to help identify those at potential risk.

The authors acknowledge the limitations of this study. First, the number of enrolled participants is relatively small, and further validation studies will be needed to confirm and enhance the tool’s accuracy. Secondly, the questionnaire did not consider certain factors that may be relevant to increased risk, such as ethnicity, and could therefore be improved by incorporating additional data.

Secondly, the participants were recruited from a clinical setting, where the prevalence of MetS is higher than in the general population. This may have influenced the predictive values of the tool, and although sensitivity and specificity are intrinsic test characteristics, some evidence suggests that prevalence may also affect these measures. Therefore, our findings should currently be interpreted with caution, as they may not be directly generalizable to the general population and will require validation in larger, population-based cohorts.

Additionally, physical activity and sleep duration were obtained from parent- or caregiver-reported information during clinical anamnesis. Although self- or proxy-reported measures may be subject to recall bias, previous studies have shown that parent-reported lifestyle information in children provides acceptable reproducibility and validity when compared with objective measures, especially in large-scale or clinical settings where accelerometry or actigraphy are not feasible.52,53 Moreover, categorization of these variables according to WHO age-specific guidelines increases their interpretability and comparability across studies.

Finally, our tool was developed and evaluated using a single, pre-specified pediatric MetS definition based on fixed, clinically interpretable thresholds, demonstrating its reliability through key diagnostic metrics: accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and AUROC, with appropriate confidence intervals. These measures directly reflect the discriminative ability and robustness of the score in the defined context. We did not perform cross-validation against other widely used pediatric definitions33,35,37 or continuous scores.27 Consequently, performance estimates and case classifications may not be directly comparable with percentile-based or cohort-referenced approaches, and some reclassification of individuals would be expected under alternative frameworks. While cross-definition validation could improve generalizability, we believe the current diagnostic analysis provides a solid foundation for initial use and represents a prudent intermediate step before possible future extensions, which we identify as a priority for future work.

Conclusions

The proposed CMR score demonstrated good sensitivity and satisfactory overall accuracy, although its specificity was more limited. The accuracy data support its value as a non-invasive, first-level risk assessment tool for the early identification of cardiometabolic risk in children, rather than as a definitive diagnostic tool. By enabling the timely recognition of at-risk individuals, the CMR score can support prompt interventions and more personalized diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, ultimately saving time and reducing healthcare costs through earlier diagnosis.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Calcaterra, V. & Zuccotti, G. Non-Communicable Diseases and Rare Diseases: A Current and Future Public Health Challenge within Pediatrics. Children 9, 1491 (2022).

Tohi, M., Bay, J. L., Tu’akoi, S. & Vickers, M. H. The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease: Adolescence as a Critical Lifecourse Period to Break the Transgenerational Cycle of NCDs—A Narrative Review. IJERPH 19, 6024 (2022).

World Health Organization (WHO). Obesity and overweight. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (2025).

Faienza, M. F. et al. The Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Risk Continuum from Prenatal Life to Adulthood: A Literature Review. Int J. Environ. Res Public Health 19, 8282 (2022).

Yusuf, S., Reddy, S., Ounpuu, S. & Anand, S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases: part I: general considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation 104, 2746–2753 (2001).

Calcaterra, V. et al. Cardiovascular Risk in Pediatrics: A Dynamic Process during the First 1000 Days of Life. Pediatr. Rep. 15, 636–659 (2023).

Obeidat, A. A. et al. Developmental Trends of Metabolic Syndrome in the Past Two Decades: A Narrative Review. JCM 14, 2402 (2025).

Mohamed, S. M. et al. Metabolic syndrome: risk factors, diagnosis, pathogenesis, and management with natural approaches. Food Chem. Adv. 3, 100335 (2023).

Iafusco, D. et al. From Metabolic Syndrome to Type 2 Diabetes in Youth. Child. (Basel) 10, 516 (2023).

Tailor, A. M., Peeters, P. H. M., Norat, T., Vineis, P. & Romaguera, D. An update on the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. Int J. Pediatr. Obes. 5, 202–213 (2010).

Wasniewska, M. et al. Skeptical Look at the Clinical Implication of Metabolic Syndrome in Childhood Obesity. Child. (Basel) 10, 735 (2023).

Gurka, M. J., Ice, C. L., Sun, S. S. & DeBoer, M. D. A confirmatory factor analysis of the metabolic syndrome in adolescents: an examination of sex and racial/ethnic differences. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 11, 128 (2012).

DeBoer, M. D., Gurka, M. J., Woo, J. G. & Morrison, J. A. Severity of the metabolic syndrome as a predictor of type 2 diabetes between childhood and adulthood: the Princeton Lipid Research Cohort Study. Diabetologia 58, 2745–2752 (2015).

Leone, A. et al. Evaluation of Different Adiposity Indices and Association with Metabolic Syndrome Risk in Obese Children: Is there a Winner?. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 4083 (2020).

Maffeis, C., Banzato, C. & Talamini, G. Obesity Study Group of the Italian Society of Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetology. Waist-to-height ratio, a useful index to identify high metabolic risk in overweight children. J. Pediatr. 152, 207–213 (2008).

Sun, J., Yang, R., Zhao, M., Bovet, P. & Xi, B. Tri-Ponderal Mass Index as a Screening Tool for Identifying Body Fat and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 694681 (2021).

Vizzuso, S. et al. Visceral Adiposity Index (VAI) in Children and Adolescents with Obesity: No Association with Daily Energy Intake but Promising Tool to Identify Metabolic Syndrome (MetS). Nutrients 13, 413 (2021).

Kardelen, A. D. & Darendeliler, F. The Role of the Intrauterine Environment in Shaping Childhood and Adolescence Metabolic Outcomes. Metabolites 15, 252 (2025).

Yadav, A. et al. Relationships between intrauterine fetal growth trajectories and markers of adiposity and inflammation in young adults. Int. J. Obes. (2005) 46, 1925–1935 (2022).

Villar, J. et al. International standards for newborn weight, length, and head circumference by gestational age and sex: the Newborn Cross-Sectional Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. Lancet 384, 857–868 (2014).

World Health Organization. Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep for Children under 5 Years of Age. (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2019).

de Lamas, C. et al. Progression of metabolic syndrome and associated cardiometabolic risk factors from prepuberty to puberty in children: The PUBMEP study. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 1082684 (2022).

Serra-Majem, L. et al. Food, youth and the Mediterranean diet in Spain. Development of KIDMED, Mediterranean Diet Quality Index in children and adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 7, 931–935 (2004).

Matthews, D. R. et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28, 412–419 (1985).

Simental-Mendía, L. E., Rodríguez-Morán, M. & Guerrero-Romero, F. The product of fasting glucose and triglycerides as surrogate for identifying insulin resistance in apparently healthy subjects. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 6, 299–304 (2008).

Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents & National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: summary report. Pediatrics 128, S213–S256 (2011).

Ahrens, W. et al. Metabolic syndrome in young children: definitions and results of the IDEFICS study. Int J. Obes. 38, S4–S14 (2014).

Gurka, M. J. et al. Independent associations between a metabolic syndrome severity score and future diabetes by sex and race: the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities Study and Jackson Heart Study. Diabetologia 60, 1261–1270 (2017).

Wang, L. X., Filipp, S. L., Urbina, E. M., Gurka, M. J. & DeBoer, M. D. Longitudinal Associations of Metabolic Syndrome Severity Between Childhood and Young Adulthood: The Bogalusa Heart Study. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 16, 208–214 (2018).

Calcaterra, V. et al. The impact of vitamin D status on lipid profiles and atherogenic dyslipidemia markers in children and adolescents with obesity. Nutr., Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 34, 2596–2605 (2024).

Calcaterra, V. et al. Diabetes Type 2 in Neurologically Impaired Children and Adolescents Without Obesity: A New Emerging Entity? Front. Neurol. 10, 947, https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00947 (2019).

Lurbe, E. et al. 2016 European Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. J. Hypertens. 34, 1887–1920 (2016).

Zimmet, P. et al. The metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents - an IDF consensus report. Pediatr. diabetes 8, 299–306 (2007).

Weiss, R. et al. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 2362–2374 (2004).

Cook, S., Weitzman, M., Auinger, P., Nguyen, M. & Dietz, W. H. Prevalence of a metabolic syndrome phenotype in adolescents: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 157, 821–827 (2003).

de Ferranti, S. D. et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in American adolescents: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Circulation 110, 2494–2497 (2004).

Viner, R. M., Segal, T. Y., Lichtarowicz-Krynska, E. & Hindmarsh, P. Prevalence of the insulin resistance syndrome in obesity. Arch. Dis. Child. 90, 10–14 (2005).

Alberti, K. G. & Zimmet, P. Z. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet. Med. : a J. Br. Diabet. Assoc. 15, 539–553 (1998).

Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 285, 2486–2497 (2001).

Alberti, K. G. et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 120, 1640–1645 (2009).

Valerio, G. et al. Cardiometabolic risk in children and adolescents with obesity: a position paper of the Italian Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetology. Ital. J. pediatrics 50, 205 (2024).

Libman, I. M., Barinas-Mitchell, E., Bartucci, A., Robertson, R. & Arslanian, S. Reproducibility of the oral glucose tolerance test in overweight children. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 93, 4231–4237 (2008).

Guembe, M. J. et al. Risk for cardiovascular disease associated with metabolic syndrome and its components: a 13-year prospective study in the RIVANA cohort. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 19, 195 (2020).

Neeland, I. J. et al. Metabolic syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 10, 77 (2024).

Tune, J. D., Goodwill, A. G., Sassoon, D. J. & Mather, K. J. Cardiovascular consequences of metabolic syndrome. Transl. Res 183, 57–70 (2017).

Hsu, P. W.-C., Chen, Y.-R. & Sheu, W. H.-H. MetS-Z: A. gender- and age-specific scoring system for predicting type 2 diabetes. J. Diabetes Investig. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.70004 (2025).

Summer, S. S., Jenkins, T., Inge, T., Deka, R. & Khoury, J. C. Association of diet quality, physical activity, and abdominal obesity with metabolic syndrome z-score in black and white adolescents in the US. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc Dis. 32, 346–354 (2022).

DeBoer, M. D., Filipp, S. L. & Gurka, M. J. Use of a Metabolic Syndrome Severity Z Score to Track Risk During Treatment of Prediabetes: An Analysis of the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care 41, 2421–2430 (2018).

Porchia, L. M. et al. Validation of a non-laboratorial questionnaire to identify Metabolic Syndrome among a population in central Mexico. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 43, e9 (2019).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)DC & American Diabetes Association. Prediabetes Risk Test. https://www.cdc.gov/prediabetes/risktest/index.html (2022).

Makrilakis, K. et al. Validation of the Finnish diabetes risk score (FINDRISC) questionnaire for screening for undiagnosed type 2 diabetes, dysglycaemia and the metabolic syndrome in Greece. Diabetes Metab. 37, 144–151 (2011).

Chaput, J. P. et al. (2016). Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl. Physiol., Nutr., Metab. = Physiologie Appl., Nutr. et. Metab. 41, S266–S282 (2016).

Biddle, S. et al. Tracking of sedentary behaviours of young people: A systematic review. Preventive Med. 51, 345–351 (2010).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to (1) Martina Tosi, Caterina Cavallo, Khatija Bahdur for their support on the project; (2) National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.4 - Call for tender No. 3138 of 16 December 2021, rectified by Decree n.3175 of 18 December 2021 of Italian Ministry of University and Research funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU; Project code CN_00000033, Concession Decree No. 1034 of 17 June 2022 adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, CUP F13C22000720007, Project title “National Biodiversity Future Center – NBFC”.

Funding

The project received contributions from PODiaCar Project 101128946-PODiaCar-EU4H-2022-PJ-3 co-funded by European Union. Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Pavia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.C., G.Z. C.C., M.V., E.E., conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising the article; L.L. statistical analysis, drafting the article; V.R., G.F., M.E.M, L.P.R, V.C.P, A.G., L.M., V.P., C.C., S.M., U.C acquisition of data, drafting the article. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Lombardia 1 (protocol number CET 202-2023).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all parents and/or guardians involved in the study after they were briefed on the study’s purpose and nature.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Calcaterra, V., Labati, L., Campoy, C. et al. A non-invasive tool for the early identification of children at risk of cardiometabolic dysfunction: data from the PODiaCar project. Pediatr Res (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-025-04603-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-025-04603-y