Abstract

Background

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I encompasses peptide-binding proteins that regulate T-cell interactions. We examined HLA class I expression in prostate cancers (PC), exploring associations with clinical outcomes, molecular features, and tumor immune microenvironment.

Methods

We analyzed 8040 PC samples from the Caris Life Sciences database, stratifying them into HLA-high (upper quartile) and -low (lower quartile) groups. Genomic and transcriptomic alterations were compared. Immune cell fractions were inferred using quanTIseq, and overall survival (OS) data was obtained from insurance claims. Differences were computed with Cox proportional hazards.

Results

Among 66 cancer types, PC ranked 3rd-, 11th-, and 19th-lowest for HLA-A, -B, and -C expression, respectively. In PC, genes tied to androgen receptor (AR) signaling, immune checkpoint molecules (CTLA4, PD-L1), and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition were significantly higher in HLA-high tumors. HLA-high status was linked to greater tumor immune activity, marked by higher T cell fractions and enhanced immune hallmarks. HLA-high tumors were less likely to possess alterations in AR, FOXA1, and CDK12, but harbored increased alterations in tumor suppressor gene (RB1, PTEN) alterations. Tumors with high HLA-A and HLA-B had elevated TMB-H/MSI-H/dMMR status. Finally, shorter OS was observed in patients with high HLA-A or HLA-B expression, while longer OS was associated with high HLA-C expression.

Conclusions

In PC, elevated HLA class I levels correlate with immune activity, molecular characteristics, and clinical outcomes. We suggest considering HLA expression as a supplementary marker of immune activity in PC, alongside genetic mutations and transcriptomic markers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PC) is the most commonly diagnosed malignancy in men globally [1, 2]. The androgen receptor (AR) is the main therapeutic target for the current standard treatment of PC [3, 4]. However, resistance to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) ultimately leads to cancer progression and a need for other treatment options [5]. ADT resistance is associated with changes in the tumor microenvironment (TME), which impacts tumor immune cell interactions and responses to immune therapies against PCs [6, 7]. Altogether, it is essential to examine other factors shaping the TME to identify other avenues for targeted therapeutics and to inform PC prognosis.

Class I human leukocyte antigens (HLA) comprise HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C subclasses [8]. These encode peptide-binding domains on the cell surface and mediate T cell activation, thereby directing cytotoxic T cell-based antitumor immunity. HLA downregulation on cancer cells is an established mechanism of immune escape. As evidence of this, HLA allele deletion, or loss of heterozygosity, is more frequently observed in advanced cancers relative to primary tumors and is associated with poor prognosis and limited response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) in some malignancies [9,10,11,12]. PC, as compared to other cancers, is considered “immune-cold” with respect to tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and responses to ICIs [13], with <5% of PCs harboring markers of immunotherapy responsiveness [10,11,12,13]. Our recent case report of two PC nodules within the same patient demonstrated that despite both tumors being TMB-high and MMR-deficient divergent, HLA expression patterns can drive differences in immune cell interactions [14]. Separately, recent studies have indicated that HLA expression may be suppressed by AR signaling, in which AR blockade results in gaining responsiveness to immunotherapies [15, 16]. This evidence suggests that in prostate tumor cells, HLAs interact with various tumoral features that altogether mediate tumor and immune cell interactions.

This study is centered on the hypothesis that differences in classical HLA class I expression in PC will be associated with differences in the tumor microenvironment, somatic features, and clinical outcomes. By analyzing a database of molecularly-profiled real-world patient samples, we retrospectively examined 8,040 PC samples partitioned by high and low expression of HLA-A, -B, and -C. Our study is the first to analyze HLA class I allele expression using a large clinical cohort compared to previous studies (Supplementary Table 1). We identified differences in molecular features, signaling pathways, and patient outcomes, which suggests that consideration of HLA expression status may inform prognosis and facilitate future studies to improve outcomes for patients with PC.

Methods

Study approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, Belmont report, and U.S. Common Rule. In keeping with 45 CFR 46.101(b) 32, this study was performed using retrospective, de-identified clinical data. Therefore, this study is considered institutional review board (IRB) exempt, and no patient consent was necessary from the subjects. This study has been granted an IRB exemption (Study No. 00013548). However, the construction of the source database and its use for research purposes have received IRB approval (IRB No. 00013548).

Clinical information and survival analysis

We queried a de-identified dataset of real-world patients’ samples that underwent comprehensive molecular profiling at a CLIA/CAP-certified lab (Caris Life Sciences). Overall survival (OS) was defined as the date of tissue collection to either death or last contact extracted from insurance claims data. Hazard ratios (HR) were calculated using the Cox proportional hazards model, and P values were calculated using the log-rank test. Treatment information was derived from insurance-claimed data. Multivariate analyses were conducted adjusting for age, race, histology, TP53, TMB, and MSI statuses.

Next-generation sequencing of the DNA

NGS was performed on genomic DNA isolated from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor samples using the NextSeq or NovaSeq 6000 platforms. Clinically relevant genes (either 592 or 700 genes) were sequenced at high coverage with an average sequencing depth of >500. Genetic variants identified were interpreted by board-certified molecular geneticists and categorized according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) standards. ‘Pathogenic’ and ‘likely pathogenic’ were counted as mutations. The copy number alteration (CNA) of each exon is determined by calculating the average depth of the sample along with the sequencing depth of each exon and comparing this calculated result to a pre-calibrated value.

HLA genotypes

The Caris WES HLA assay provides a genotype for the MHC Class I HLAs (A, B and C genes) down to the allele using OptiType [17], when reads are >10x depth. Samples with homozygous HLA were defined as having identical high-resolution HLA genotypes [18], while those with heterozygous HLA had different HLA genotypes. The RNA-Seq data is read by arcasHLA [19] to provide a genotype for the HLA alleles present and expressed in the patient sample. At least 100 reads for a given HLA Class I gene is necessary to obtain an HLA call for that gene via WTS.

RNA expression

The same FFPE specimens were processed as previously discussed to collect RNA [20, 21]. The Illumina NovaSeq 6500 was then used to sequence the whole transcriptome from patients to an average of 60 M reads. Raw data was demultiplexed by Illumina Dragen BioIT accelerator, trimmed, and counted, and PCR-duplicates were removed and aligned to human reference genome hg19 by STAR aligner [22]. For transcription counting, transcripts per million values noted in transcripts per million (TPM) were generated using the Salmon expression pipeline [23].

Transcription analysis

The Hallmarks of gene sets of Gene Set Enrichment Analysis was used to evaluate pathway enrichment [24]. Immune cell tumor infiltration was inferred using quanTIseq based on the deconvolution of bulk RNA-seq data as previously described [25].

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared using non-parametric tests, including Mann Whitney-U tests, while categorical data were compared using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, where appropriate. Comparisons among groups of more than three were made using the ANOVA test. Differential gene expression analysis was done using the Mann-Whitney U test and corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg ad hoc test. A p-value of <0.05 or an adjusted p-value of < 0.05 was considered a significant difference [26]. Unless otherwise specified, in figures, the bars show min to max values, and asterisks represent the following p-values: * <0.05, ** <0.01, *** < 0.001. If there was no significant difference between the analysis (p > 0.05), the statistical significance was not shown on the graphs.

Results

Prostate cancers exhibit reduced HLA class I expression

We investigated the Caris database, comprised of 10,759 PC samples, including 6,344 primary and 4,415 metastatic biopsies. Among these, HLA expression data was available for 75% (8,040) of samples (Supplementary Tables 2-3). Reported in TPM for all samples, we found that among 66 cancer types, PC ranked 3rd-, 11th-, and 19th-lowest with respect to HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C expression, respectively (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table 4). When stratified by biopsy site, median expressions for all HLA class I loci were lower in biopsies obtained from metastatic sites as compared to primary sites (Fig. 1B). Among the most common metastatic sites, lymph node biopsies had the lowest HLA expression, followed by bone, liver, and bladder biopsies (Fig. 1C). Altogether, HLA class I expression in PC was low compared to other cancers, with expression levels decreased further in metastatic tumors relative to primary tumors.

. HLA class I expression among all cancers from the Caris database ranked by median expression level. Red text denotes prostate adenocarcinoma A. HLA class I expression among PC stratified by biopsy (bx) sites (primary prostate vs. metastatic sites) B and stratified by common metastatic sites C. The Venn diagram showed the number of PCs in each subgroup stratified by HLA class I expression D. Stacked bar graphs showing percentage of each race in each HLA expression subgroup E.

To explore the impact of HLA class I expression in PC, we stratified PC samples into HLA-high (>75th percentile; upper quartile) and -low (<25th percentile; lower quartile) groups for HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C expression (Fig. 1D). When examining these HLA-high and -low groups with respect to self-reported race, white PC patients had significant increases in the HLA-high group, whereas African Americans demonstrated the opposite trend (Fig. 1E and Supplementary Table 5). PCs appear to regulate the expression of all three HLA class I genes in a concordant fashion. However, our results also indicate that racial background influences HLA expression.

High HLA expression is associated with increased alterations of tumor suppressor genes and decreased AR-related mutations

To investigate the molecular associations of increased HLA class I expression, we compared the prevalence of pathogenic alterations between HLA-high and -low subgroups. Pathogenic alterations in AR and FOXA1, a pioneering AR transcription co-factor [27, 28], were more common in the HLA-low relative to the HLA-high groups by two-fold. Alterations of SPOP, another regulator of AR protein stability [29], was significantly higher in the HLA-A–low group but lower in the HLA-C–low group. (Fig. 2A). We next examined tumor suppressors that drive poor clinical outcomes in PC [30,31,32,33]. HLA-A and HLA-B–high groups had elevated rates of PTEN and RB1 alterations, while only the HLA-A–high group had elevated TP53 alterations (Fig. 2B). PCs harboring mutations in homologous recombination repair (HRR) genes can be managed with PARP inhibitors [34], therefore we also explored HRR gene alterations. Interestingly, PC with high HLA expression had reduced CDK12 mutations, but no differences in other HRR genes (Fig. 2C). Some of the genomic findings were validated in two external cohorts: primary prostate cancer from the Cancer Genome Atlas Program (TCGA) and advanced prostate cancer from the Stand Up To Cancer (SU2C), especially for FOXA1 and TP53 alterations (Fig. 2D, E and Supplementary Fig. 1A, B). In summary, elevated expression of HLA was associated with numerous somatic characteristics that regulate PC progression, including key regulators that may activate AR signaling and alterations in tumor suppressor genes. Conversely, CDK12 mutations may drive low HLA expression.

Bar graphs showing percentages of pathogenic alterations in AR-related genes A, tumor suppressors B, and HRR-pathway genes C. Bar graphs showing percentages of pathogenic alteration of FOXA1 D and TP53 E in TCGA and SU2C cohorts. Color key for figure A–E is presented next to the figure E. Bubble plots showing differential gene expression of CTLA4 and CD274 (PD-L1) in the Caris cohort, compared to the TCGA and SU2C cohorts F. Bubble plots showing gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of cancer-related hallmark gene sets relative to HLA-high groups G.

Increased HLA expression is associated with elevated PD-L1 and CTLA4 expression and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT)

Next, we examined transcriptomes to determine the association of HLA expression with genes or pathways that regulate PC progression. HLA-high vs. -low tumors harbored significant transcriptomic differences. Genes involved in AR regulation, immunoglobins, immune targets, and neuroendocrine differentiation [14, 31, 35] were generally enriched in HLA-high patients (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 6–9). We then examined targets of immunotherapy and cell surface proteins that represent therapeutic targets in PC [36,37,38,39,40] (Supplementary Fig. 3A). CD274 (PD-L1) and CTLA4 were significantly enriched in all HLA-high groups, which were consistent in 2 external cohorts (Fig. 2F). AR- and NEPC-related genes were variably expressed in different cohorts (Supplementary Fig. 3A–C). To identify biological pathways associated with HLA expression, we performed a GSEA study. Among Hallmark pathways, EMT, TGF-β signaling, and oxidative phosphorylation were highly enriched (NES > 1.5) in all HLA class I–high groups, while TP53 and DNA repair were enriched in HLA-B and HLA-C–high groups (Fig. 2G). Altogether, increased HLA class I expression was associated with somatic alterations of genes in the AR pathway, as well as druggable cell surface proteins and pro-tumor signaling pathways.

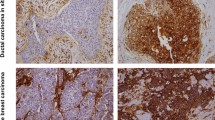

HLA expression is associated with increased T cells and immunotherapy markers

We next examined the association of HLA expression with immune infiltrates using quanTIseq [25]. Regulatory T cells (Tregs), cytotoxic T cells (CD8 + ), and helper T cells (CD4 + ) were all significantly increased across HLA-high groups (Fig. 3A). B cells, NK cells, M1 and M2 macrophages, and myeloid dendritic cells were all increased in HLA-high groups. IFNα and IFNγ pathways were highly enriched (NES > 1.8) in all HLA-high groups. Other pathways, including IL2, IL6, TNF-α, complement, and inflammatory response, were also generally enriched (NES > 1.5) in HLA-high groups, particularly in HLA-B and HLA-C loci (Fig. 3B). HLA-A and HLA-B–high tumors exhibited numerical increases in microsatellite instability (MSI-H) and deficiencies in mismatch repair (dMMR) status (Fig. 3C). These analyses indicate that elevated HLA expression is associated with increased T cell infiltration, augmentation of various immune regulatory pathways, as well as enrichment of ICI biomarkers.

Bar graphs showing mean percentages of immune cells inferred by quanTIseq between PC with high and low HLA class I expression A. Bubble plots showing GSEA of hallmark gene sets related to immunologic processes relative to HLA-high groups B. Bar graphs showing percentages of immunotherapy-related markers (TMB-high, MSI-high, MMR deficient, and PD-L1 positive) C.

Genomic mechanisms of HLA expression

To understand the mechanisms of differential HLA expression and potential relationships with allele zygosity, we explored associations between HLA zygosity and HLA expression. Compared to primary tumors, metastatic tumors exhibited a higher proportion of samples that were homozygous for HLA-B and homozygous for any of HLA-A/B/C (Fig. 4A). However, when considering all PC samples together, the HLA-high and -low groups did not exhibit differences in the rates of HLA homozygosity (Fig. 4B). Genome-wide loss of heterozygosity (gLOH) is another potential mechanism that may influence HLA expression [41, 42]. PC with low HLA expression exhibited a ~ 1.7-fold greater prevalence of high gLOH (Fig. 4C). Altogether, in PC, there may be complex mechanisms that regulate HLA expression beyond allele homozygosity and genome-wide LOH status. Furthermore, a greater degree of gLOH may result in an adaptive suppression of HLA class I expression.

Bar graphs showing the percentage of PC with HLA homozygosity in primary prostate and metastatic biopsies (Bx) A. Bar graphs showing the percentage of PC with HLA homozygosity B and PC with high genome-wide LOH ( > 16%) C stratified by HLA-high and HLA-low groups. Color key for figure B, C is presented next to the figure C.

HLA class I expression and survival outcomes

Last, we investigated the effects of HLA expression on patient outcomes. OS was compared between HLA-high and HLA-low groups, which were further stratified by biopsy sites (primary versus metastatic). Multivariate analyses were conducted, adjusted for age, race, histology, TP53, TMB, and MSI statuses. Worse OS was seen with HLA-A or HLA-B–high status from prostate biopsies (HR = 1.37, p < 0.0001; HR = 1.25, p = 0.0003) or HLA-A–high status from metastatic tumors (HR = 1.17, p = 0.025) (Fig. 5A). HLA-C expression status had no prognostic value among patients with either prostate or metastatic biopsies. Given that the majority of PC exhibited concordant up-and down-regulation of all three HLA loci (Fig. 1D), to evaluate the specific effect of each locus, we focused on the smaller subset of tumors in which only one class I HLA was changed (non-overlap groups). In this subset analysis, elevated HLA-A status alone from primary or metastatic biopsies was still associated with worse OS (HR 1.39, p = 0.022; HR 1.78, p = 0.0002). No significant findings were associated with HLA-B, whereas improved OS was seen in HLA-C–high prostate biopsies (HR 0.73, p = 0.021) (Fig. 5B). Altogether, the status of HLA-A was prognostic when considering OS.

Racial Differences in HLA-Associated Survival and Underlying Genomic Alterations

Given the racial differences in HLA expression distribution (Fig. 1E), we performed univariate OS analyses stratified by race, as sample sizes were limited. In the Caucasian cohort, OS patterns were similar to the overall cohort, whereas the African cohort showed a trend toward improved survival with higher HLA expression, particularly in the HLA-A allele group, opposite to the overall trend (Supplementary Fig. 4A). To assess potential confounders, we compared known prognostic genomic alterations in prostate cancer [43] between racial groups within each HLA expression subgroup. African patients had significantly lower rates of TMPRSS2 fusion and TP53 alterations than Caucasian patients, while rates of AR mutations, PTEN loss, and SMAD4 loss were comparable (Supplementary Fig. 4B). These genomic differences, along with a known HLA genotype heterogeneity among races [18], may partly explain the reversed OS trend in the African subgroup.

Discussion

This study evaluated HLA class I levels in 8,040 PC tumors from the clinicogenomics database. High HLA expression samples exhibited distinct genomic and transcriptomic features as compared to low HLA samples. Tumors with high HLA expression had more mutations in tumor suppressors, while AR and FOXA1 alterations were higher in low HLA groups. High HLA tumors showed unique gene expression patterns, including increased EMT and TGFβ pathways. Unsurprisingly, high HLA expression correlated with more immune infiltrates, checkpoint molecules, and cytokine pathways. However, despite indications of immune activation, high HLA was mostly linked to worse overall survival in PC patients. These findings underscore the complexities of measuring outcomes in PC and suggest interactions between HLA class I genes and other molecular and immunologic features in PC.

Our findings, in which PC cases have lower HLA expression compared to 66 other malignancies, align with prior evaluations of HLA in smaller studies of PC patients [16, 44]. These findings hint at the developmental process of tumors in the prostate gland, an environment without robust antitumor immunity. However, further decreased HLA expression in metastatic samples suggests that the progression towards metastasis outside of the prostate gland requires additional downregulation of immune cell interactions. Interestingly, African American patients are a subset with an increased risk of de novo metastatic disease [45, 46], and we found that a greater proportion of their tumors were lower in HLA expression. As this finding is based on statistical associations, it requires orthogonal approaches for further validation in these populations.

We examined genomic alterations in patients related to HLA expression and found pathogenic changes in AR and FOXA1 linked to low expression of HLA. This aligns with PC cell line screens showing that increased AR signaling leads to reduced HLA expression [16]. Since AR alterations are selected in metastatic tumors [30, 31], this partially helps explain their lower HLA class I expression. Additionally, HLA-high tumors showed higher levels of AR cofactors (HOXB13 and FOXA1) and enrichment of the Hallmark androgen response. Intriguingly, tumor suppressor alterations were associated with the HLA-high group. Research has shown that TP53 and PTEN mutations yield neoantigens that activate TIL responses in PC [47,48,49]. Overall, while the independent effects in metastatic prostate tumors require further investigation, alterations in tumor suppressors and AR signaling distinctly affect HLA expression.

In HLA-high patients, we identified that PD-L1 and CTLA4 are important components of immune checkpoints that are frequently upregulated in patients with robust antitumor immunity [50]. However, when considering immune cell subsets, increased HLA expression was associated with immune cells that have pro- (M2 macrophages) or anti-tumor (NK cells, T-cells) functions [51]. Note that prior clinical studies revealed upregulation of CD8 + T cells and Tregs following ADT [52, 53]. Here, we report that PCs with a high expression of HLA-A and HLA-B tended to have higher rates of dMMR, MSI-H, and TMB-H status and, importantly, elevated TIL, all indicators for the use of pembrolizumab. In conjunction with recent studies of pembrolizumab modulation through AR signaling activity [16], it is possible that HLA expression has value in predicting ICI sensitivity, which would expand the number of eligible patients. This rationale is further supported by studies that have indicated that inadequate neoantigen presentation by HLA class I expression accounts for ICI unresponsiveness in tumors with high TMB [54,55,56]. However, to implement these concepts in practice, a review of HLA expression and immune cell infiltrate status must be determined through clinical trials [13, 57].

We are the first to report poor prognostic trends based on HLA class I expression in PC. Increased HLA expression is associated with improved outcomes in certain malignancies, such as colorectal, ovarian, and triple-negative breast cancer [58,59,60,61,62,63]. Here, we confirm in a large and diverse cohort that increased HLA-A and HLA-B in PC is associated with shorter OS. This poor prognosis seems counterintuitive to the increased immune cell engagement seen in these samples, which would, in theory, predict a good prognosis. However, the overall poor prognosis might be due to the increased alteration frequency of tumor suppressor genes. In PCs, these aberrant events may drive HLA class I upregulation through an adaptive (compensatory) response. Relevant to patient management, we could not determine if HLA levels were predictive of response to ICI, as the small ICI-treated sample size (n = 114) prevented a well-powered analysis.

Limitations

Our clinical database is the largest cohort known to examine HLA class I expression in PC. However, this study has certain limitations. Clinical characteristics in our cohort were limited; for example, the samples do not contain cancer staging or Gleason grading data. Additionally, our database does not include germline and ploidy status of the HLA alleles, which may act as confounders when examining HLA homozygosity. Further, our TME analysis relied on quanTIseq analysis of WTS data rather than a direct method of immunohistochemistry staining or flow cytometry. Given the above limitations, data interpretation must be approached with caution. Our study lacks experimental validation to confirm mechanistic drivers of HLA expression. However, given the limited availability of preclinical models that recapitulate the immune system of prostate cancer, we believe that analysis of human specimens offers a necessary foundation for future investigations.

Conclusions

In summary, our study explores the pattern of HLA class I expression in PC, in which we found significant associations with somatic genetic features, immune activity, and clinical outcomes. Due to these findings, we propose that it may be relevant to assess HLA class I expression levels through molecular diagnostic tests, such as that from Caris Life Sciences. These may have value as a secondary evaluation for the use of current or future forms of ICI. The many genomic and molecular associations with HLA status reported here require subsequent research through laboratory studies, in which further studies may elucidate refined mechanisms of HLA regulation in PCs.

Data availability

The principal investigator of this study has full access to all the data and takes responsibility for its integrity and accuracy. The data is not publicly available due to the data usage agreement between the study team’s facilities. When possible, derived data supporting the findings of this study have been made available within the paper and its Supplementary Figures/Tables. Other data can be acquired through a letter of intent to Caris Life Sciences (https://www.carislifesciences.com/letter-of-intent/). Additional inquiries can be sent to Andrew Elliott at aelliott@carisls.com.

References

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229–63.

Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:12–49.

Schaeffer EM, Srinivas S, Adra N, An Y, Barocas D, Bitting R, et al. Prostate Cancer, Version 4.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw JNCCN. 2023;21:1067–96.

Virgo KS, Rumble RB, Talcott J. Initial Management of Noncastrate Advanced, Recurrent, or Metastatic Prostate Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:3652–6.

Tilki D, Schaeffer EM, Evans CP. Understanding Mechanisms of Resistance in Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer: The Role of the Androgen Receptor. Eur Urol Focus. 2016;2:499–505.

Kissick HT, Sanda MG, Dunn LK, Pellegrini KL, On ST, Noel JK, et al. Androgens alter T-cell immunity by inhibiting T-helper 1 differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:9887–92.

Mercader M, Bodner BK, Moser MT, Kwon PS, Park ES, Manecke RG, et al. T cell infiltration of the prostate induced by androgen withdrawal in patients with prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:14565–70.

Klein J, Sato A. The HLA System. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:702–9.

McGranahan N, Rosenthal R, Hiley CT, Rowan AJ, Watkins TBK, Wilson GA, et al. Allele-Specific HLA Loss and Immune Escape in Lung Cancer Evolution. Cell. 2017;171:1259–71.e11.

Chowell D, Morris LGT, Grigg CM, Weber JK, Samstein RM, Makarov V, et al. Patient HLA class I genotype influences cancer response to checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Science. 2018;359:582–7.

Montesion M, Murugesan K, Jin DX, Sharaf R, Sanchez N, Guria A, et al. Somatic HLA Class I Loss Is a Widespread Mechanism of Immune Evasion Which Refines the Use of Tumor Mutational Burden as a Biomarker of Checkpoint Inhibitor Response. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:282–92.

Rosenthal R, Cadieux EL, Salgado R, Bakir MA, Moore DA, Hiley CT, et al. Neoantigen directed immune escape in lung cancer evolution. Nature. 2019;567:479–85.

Antonarakis ES, Park SH, Goh JC, Shin SJ, Lee JL, Mehra N, et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Olaparib for Patients With Previously Treated and Biomarker-Unselected Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: The Randomized, Open-Label, Phase III KEYLYNK-010 Trial. J Clin Oncol J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2023;41:3839–50.

Bergom HE, Sena LA, Day A, Miller B, Miller CD, Lozada JR, et al. Divergent immune microenvironments in two tumor nodules from a patient with mismatch repair-deficient prostate cancer. Npj Genom Med. 2024;9:1–9.

Guan X, Polesso F, Wang C, Sehrawat A, Hawkins RM, Murray SE, et al. Androgen receptor activity in T cells limits checkpoint blockade efficacy. Nature. 2022;606:791–6.

Chesner LN, Polesso F, Graff JN, Hawley JE, Smith AK, Lundberg A, et al. Androgen receptor inhibition increases MHC Class I expression and improves immune response in prostate cancer. Cancer Discov 2025;15:481–94.

Szolek A, Schubert B, Mohr C, Sturm M, Feldhahn M, Kohlbacher O. OptiType: precision HLA typing from next-generation sequencing data. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 2014;30:3310–6.

Gragert L, Madbouly A, Freeman J, Maiers M. Six-locus high resolution HLA haplotype frequencies derived from mixed-resolution DNA typing for the entire US donor registry. Hum Immunol. 2013;74:1313–20.

Orenbuch R, Filip I, Comito D, Shaman J, Pe’er I, Rabadan R. arcasHLA: high-resolution HLA typing from RNAseq. Bioinforma Oxf Engl. 2020;36:33–40.

Dawood S, Natarajan V, Danchaivijitr P. Comprehensive molecular profiling identifies actionable biomarkers for patients from Thailand and the United Arab Emirates with advanced malignancies. Front Oncol. 2024;14:1374087.

Hwang J, Likasitwatanakul P, Deshmukh SK, Wu S, Kwon JJ, Toye E et al. Structurally-oriented classification of FOXA1 alterations identifies prostate cancers with opposing clinical outcomes and distinct molecular and immunologic subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2025;31:936–48.

Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21.

Patro R, Duggal G, Love MI, Irizarry RA, Kingsford C. Salmon: fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression using dual-phase inference. Nat Methods. 2017;14:417–9.

Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–50.

Finotello F, Mayer C, Plattner C, Laschober G, Rieder D, Hackl H, et al. Molecular and pharmacological modulators of the tumor immune contexture revealed by deconvolution of RNA-seq data. Genome Med. 2019;11:34.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol. 1995;57:289–300.

Teng M, Zhou S, Cai C, Lupien M, He HH. Pioneer of prostate cancer: past, present and the future of FOXA1. Protein Cell. 2021;12:29–38.

Jozwik KM, Carroll JS. Pioneer factors in hormone-dependent cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:381–5.

Geng C, Rajapakshe K, Shah SS, Shou J, Eedunuri VK, Foley C, et al. Androgen receptor is the key transcriptional mediator of the tumor suppressor SPOP in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:5631–43.

Abida W, Cyrta J, Heller G, Prandi D, Armenia J, Coleman I, et al. Genomic correlates of clinical outcome in advanced prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:11428–36.

Dan R, Van Allen EM, Wu Y-M, Schultz N, Lonigro RJ, Mosquera J-M, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;161:1215–28.

Maughan BL, Guedes LB, Boucher K, Rajoria G, Liu Z, Klimek S, et al. p53 status in the primary tumor predicts efficacy of subsequent abiraterone and enzalutamide in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2018;21:260–8.

Velez MG, Kosiorek HE, Egan JB, McNatty AL, Riaz IB, Hwang SR, et al. Differential impact of tumor suppressor gene (TP53, PTEN, RB1) alterations and treatment outcomes in metastatic, hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2022;25:479–83.

Bono, de J, Mateo J, Fizazi K, Saad F, Shore N, et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2091–102.

Beltran H, Rickman DS, Park K, Chae SS, Sboner A, MacDonald TY, et al. Molecular characterization of neuroendocrine prostate cancer and identification of new drug targets. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:487–95.

Bhatia V, Kamat NV, Pariva TE, Wu L-T, Tsao A, Sasaki K, et al. Targeting advanced prostate cancer with STEAP1 chimeric antigen receptor T cell and tumor-localized IL-12 immunotherapy. Nat Commun. 2023;14:2041.

Perera MPJ, Thomas PB, Risbridger GP, Taylor R, Azad A, Hofman MS, et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy in Metastatic Castrate-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Cancers. 2022;14:503.

Mjaess G, Aoun F, Rassy E, Diamand R, Albisinni S, Roumeguère T. Antibody-Drug Conjugates in Prostate Cancer: Where Are we?. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2023;21:171–4.

Palecki J, Bhasin A, Bernstein A, Mille PJ, Tester WJ, Kelly WmK, et al. T-Cell redirecting bispecific antibodies: a review of a novel class of immuno-oncology for advanced prostate cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2024;25:2356820.

Zarrabi KK, Narayan V, Mille PJ, Zibelman MR, Miron B, Bashir B, et al. Bispecific PSMA antibodies and CAR-T in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Ther Adv Urol. 2023;15:17562872231182219.

Wang XC, Zhang JQ, Shen YQ, Miao FQ, Xie W. Loss of heterozygosity at 6p21.3 underlying HLA class I downregulation in gastric cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res CR. 2006;25:115–9.

Zhao X, Sun Q, Tian H, Cong B, Jiang X, Peng C. Loss of heterozygosity at 6p21 and HLA class I expression in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas in China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2011;12:2741–5.

Martin NE, Mucci LA, Loda M, DePinho RA. Prognostic Determinants in Prostate Cancer. Cancer J Sudbury Mass. 2011;17:429–37.

Schaafsma E, Fugle CM, Wang X, Cheng C. Pan-cancer association of HLA gene expression with cancer prognosis and immunotherapy efficacy. Br J Cancer. 2021;125:422–32.

Powell IJ, Banerjee M, Sakr W, Grignon D, Wood DP, Novallo M, et al. Should African-American men be tested for prostate carcinoma at an earlier age than white men?. Cancer. 1999;85:472–7.

Powell IJ, Heilbrun LK, Sakr W, Grignon D, Montie J, Novallo M, et al. The predictive value of race as a clinical prognostic factor among patients with clinically localized prostate cancer: a multivariate analysis of positive surgical margins. Urology. 1997;49:726–31.

Malekzadeh P, Pasetto A, Robbins PF, Parkhurst MR, Paria BC, Jia L, et al. Neoantigen screening identifies broad TP53 mutant immunogenicity in patients with epithelial cancers. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:e123791.

Vidotto T, Melo CM, Castelli E, Koti M, dos Reis RB, Squire JA. Emerging role of PTEN loss in evasion of the immune response to tumours. Br J Cancer. 2020;122:1732–43.

Williams JL, Greer PA, Squire JA. Recurrent copy number alterations in prostate cancer: an in silico meta-analysis of publicly available genomic data. Cancer Genet. 2014;207:474–88.

Buchbinder EI, Desai A. CTLA-4 and PD-1 Pathways. Am J Clin Oncol. 2016;39:98–106.

Zorko NA, Makovec A, Elliott A, Kellen S, Lozada JR, Arafa AT, et al. Natural Killer Cell Infiltration in Prostate Cancers Predict Improved Patient Outcomes. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2025;28:129–37.

Dallos MC, Obradovic AZ, McCann P, Chowdhury N, Pratapa A, Aggen DH, et al. Androgen Deprivation Therapy Drives a Distinct Immune Phenotype in Localized Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2024;30:5218–30.

Obradovic A, Dallos MC, Zahurak ML, Partin AW, Schaeffer EM, Ross AE, et al. T-Cell Infiltration and Adaptive Treg Resistance in Response to Androgen Deprivation With or Without Vaccination in Localized Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res J Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2020;26:3182–92.

Marty R, Kaabinejadian S, Rossell D, Slifker MJ, van de Haar J, Engin HB, et al. MHC-I Genotype Restricts the Oncogenic Mutational Landscape. Cell. 2017;171:1272–83.e15.

Goodman AM, Castro A, Pyke RM, Okamura R, Kato S, Riviere P, et al. MHC-I genotype and tumor mutational burden predict response to immunotherapy. Genome Med. 2020;12:45.

Yamaguchi H, Hsu J-M, Sun L, Wang S-C, Hung M-C. Advances and prospects of biomarkers for immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cell Rep Med 2024; 5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101621.

Antonarakis ES, Piulats JM, Gross-Goupil M, Goh J, Ojamaa K, Hoimes CJ, et al. Pembrolizumab for Treatment-Refractory Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Multicohort, Open-Label Phase II KEYNOTE-199 Study. J Clin Oncol J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2020;38:395–405.

Michelakos T, Kontos F, Kurokawa T, Cai L, Sadagopan A, Krijgsman D, et al. Differential role of HLA-A and HLA-B, C expression levels as prognostic markers in colon and rectal cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10:e004115.

Matsushita H, Hasegawa K, Oda K, Yamamoto S, Asada K, Karasaki T, et al. Neoantigen load and HLA-class I expression identify a subgroup of tumors with a T-cell-inflamed phenotype and favorable prognosis in homologous recombination-proficient high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8:e000375.

Shehata M, Mukherjee A, Deen S, Al-Attar A, Durrant LG, Chan S. Human leukocyte antigen class I expression is an independent prognostic factor in advanced ovarian cancer resistant to first-line platinum chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1321–8.

Zeestraten ECM, Reimers MS, Saadatmand S, Dekker J-WT, Liefers GJ, van den Elsen PJ, et al. Combined analysis of HLA class I, HLA-E and HLA-G predicts prognosis in colon cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:459–68.

Paulson KG, Voillet V, McAfee MS, Hunter DS, Wagener FD, Perdicchio M, et al. Acquired cancer resistance to combination immunotherapy from transcriptional loss of class I HLA. Nat Commun. 2018;9:3868.

Han S-H, Kim M, Chung YR, Woo JW, Choi HY, Park SY. Expression of HLA class I is associated with immune cell infiltration and patient outcome in breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2022;12:20367.

Funding

P.L. is supported by internal medicine residency program at University of Minnesota. J.H. is supported by R37CA288972. E.S.A. is partially supported by NCI grant P30 CA077598 and DOD grant W81XWH-22-2-0025. A.T.A. is supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship, PF-23-1153194-01-CDP.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PL conceptualized, designed experiments, conducted analysis, analyzed data, visualization, and wrote the original manuscript. CB wrote the original manuscript (introduction). AT conceptualized and wrote the original manuscript (discussion). NS conducted analysis, analyzed data and visualization, and wrote the original manuscript (methods). AE supervised, analyzed data, and validated data accuracy. AA conceptualized. RP, LC, MF, PRK, AP, VN, JH, LAS reviewed the manuscript. NZ& EA conceptualized and designed experiments. JH conceptualized, designed experiments, supervised and wrote the original manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

JH consults for Tempus and Astrin Biosciences and is a co-founder of EMRGNSE. ESA reports grants and personal fees from Janssen, Sanofi, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Curium, Merck, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Clovis, Constellation; personal fees from Astellas, Amgen, Blue Earth, Exact Sciences, Invitae, Eli Lilly, and Foundation Medicine; grants from Novartis, Celgene, and grants from Orion outside the submitted work; and has a patent for an AR-V7 biomarker technology that has been licensed to Qiagen. Other co-authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Likasitwatanakul, P., Besonen, C., Tsai, A.K. et al. HLA class I expression shapes the tumor immune microenvironment and influences prognosis in prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-025-01045-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-025-01045-9