Abstract

Complement C1q initiates the classical complement pathway and becomes activated in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), contributing to the association between amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau pathologies. However, whether C1q influences AD pathology by modulating glial cell communication is unclear. We included 217 participants from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database to explore the associations of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) C1q with soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (sTREM2), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and AD biomarkers. Additionally, we incorporated data from 535 participants in the Chinese Alzheimer’s Biomarker and LifestylE (CABLE) study to explore associations. We employed 10,000 bootstrapped iterations of causal mediation analysis to examine the possible mediating role of sTREM2 or GFAP in the relationship between CSF C1q and AD pathology. We found that CSF rather than serum C1q were positively associated with CSF sTREM2, GFAP, Aβ42, phosphorylated-tau (P-tau) and total tau (T-tau) at baseline. CSF C1q was only longitudinally associated with CSF T-tau levels and AD assessment scale-cognitive subscale 13 (ADAS-Cog 13) scores. Mediation analysis demonstrated that Aβ pathology partly mediated the association between CSF C1q and sTREM2 levels, which in turn impacted tau pathology progression. Serum C1q showed a significant association with CSF sTREM2 at baseline as well.

Conclusions

C1q is associated with CSF sTREM2 and mediates the relationship between Aβ and tau pathologies. This suggests that C1q may play a crucial role in the progression from Aβ pathology to tau pathology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most prevalent form of dementia, is characterized by the buildup of extracellular amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and intraneuronal neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) composed of hyperphosphorylated tau proteins [1]. Chronic neuroinflammation featuring gliosis and increased proinflammatory cytokine levels is an important contributor to AD pathogenesis [2], during which triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) functions as a regulator [3,4,5,6]. Numerous previous studies suggest that the involvement of glial cell activation is important in the mechanism of neurodegeneration-associated inflammatory signaling [7, 8]. Notably, it has been demonstrated that inhibiting the complement cascade in AD mouse models could lessen cognitive decline and synapse loss [9]. Both aggregated Aβ and tau have been shown to trigger the classical complement cascade in biochemical tests, initiating AD pathology [10]. Our study aims to elucidate the relationship between neuroinflammation and the complement system in AD pathophysiology.

C1q, the key component of the classical complement cascade, is synthesized by postnatal neurons in reaction to developing astrocytes and is present at synapses across the postnatal central nervous system (CNS) [10]. Besides, activated microglia also secrete C1q, necessary and sufficient to trigger the formation of A1 reactive astrocytes which contributes to the degeneration of neurons and oligodendrocytes in AD [11]. Previous research has identified C3 as a central component of complement signaling, and in the central nervous system, C1q is primarily produced by activated microglia [12]. During nervous system development, microglia interact with C1q and C3 to regulate synapse pruning. When stimulated by foreign C1q, microglia produce C1q to activate more microglia, creating a positive feedback loop and promoting inflammation [13]. Additionally, in an AD mouse model, reducing microglial Tmem9 levels inhibited complement activation, alleviated complement-dependent synaptic loss, and ultimately improved emotional and cognitive impairments [14]. These findings collectively highlight the reciprocal interplay between microglia and C1q. What’s more, microglia and C1q mediate neurodegeneration in AD. TREM2 attenuates the activation of classical complement pathway through its high-affinity interaction with C1q. The elevated density of TREM2-C1q complexes in the brains of individuals with AD was correlated with lower C3 deposition and greater levels of synaptic protein. In mice with mutant human tau, a deficiency in TREM2 increases complement- driven synaptic loss, but a TREM2 peptide rescues synaptic impairments, highlighting TREM2’s protective role against AD [15]. Additionally, C1q is necessary maintaining prolonged synaptic strengthening in the hippocampus and the deleterious effects of soluble Aβ oligomers on synapses [16]. Microglial complement receptor CR3 or complement factors C3 and C1q gene deletion, decreases the quantity of phagocytic microglia and mitigates early synapse loss, which suggests that complement activation might play an early role in triggering synapse loss related to plaques in AD by stimulating phagocytic microglia [17]. However, there is a lack of epidemiological evidence about the role of C1q in the astrocyte–microglia communication and pathogenesis of AD, and more large-scale cohorts are needed in the future [18].

Our aim is to explore the associations of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum C1q levels with glial cell activation and AD biomarkers in order to systematically determine the multifaceted impact of C1q on AD development and its precise interactions with glial cells. Additionally, we plan to explore the effects of CSF C1q and CSF Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) [19] or soluble TREM2 (sTREM2) [20] on AD pathology using a mediation model. Based on astrocyte–microglial communication, we postulated that CSF C1q was associated with CSF GFAP or sTREM2, which could be crucial to the advancement of AD.

Methods and materials

ADNI database

The objective of the multicenter longitudinal Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) study is to establish early diagnostic indicators for late-onset AD through the integration of imaging, genetic, clinical, and biochemical biomarkers. The participants are adults aged 55 to 90 years. This study’s data are accessible through the database at (http://adni.loni.usc.edu) [21]. Data utilized in this survey were authorized by the institutional review boards of each participating ADNI institution. Before enrolling in the study, each subject provided written consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. We included 217 individuals at baseline having complete data on age, gender, years of education, apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele, CSF biomarkers, and cognitive assessment data. Exclusions (N = 86) were according to (1) no available CSF biomarkers (N = 44), (2) influence of comorbidities affecting CSF C1q such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [22], systemic lupus erythematosus [23], pneumococcal and meningococcal meningitis [24], Parkinson disease [25], neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders [26], coronary artery disease [27] (N = 26), (3) As well as 16 participants considered an outlier with baseline CSF biomarkers concentrations deviating 5 standard deviations (SD) from the overall population means.

Measurements of CSF C1q, sTREM2, GFAP and AD biomarker levels

A cobas 601 instrument was utilized to measure the CSF levels of Aβ42, phosphorylated tau (P-tau) 181, and total-tau (T-tau) by electrochemiluminescence immunoassays. Participants were categorized as A ± (Aβ42 < 976.6 pg/ml or ≥ 976.6 pg/ml), T ± (P-tau > 21.8 pg/ml or ≤ 21.8 pg/ml), and N ± (T-tau > 245 pg/ml or ≤ 245 pg/ml) [28]. Using previously-established methods which amalgamated tau (T) and neurodegeneration (N) groups, participants were then classified into distinct A/T/N classifications: Stage 0 (A − TN − ), Stage 1 (A + TN − ), Stage 2 (A + TN + ), and suspected Non-AD Pathology (SNAP) (A − TN + ) [29]. CSF sTREM2 levels were determined using an assay based on the MSD platform, with the method having been previously reported and validated in earlier publications [30]. In ADNI, CSF C1q (B_VPGLYYFTYHASSR and B_LEQGENVFLQATDK) [31] and GFAP were quantified using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) targeted mass spectrometry [32]. Comprehensive details regarding complement proteins evaluation and quality assurance may be accessed at (http://adni.loni.usc.edu/data-samples/biospecimen-data/).

CABLE study

To validate the findings of ADNI from the perspective of peripheral C1q, data of 535 individuals without dementia were drawn from the Chinese Alzheimer’s Biomarker and Lifestyle (CABLE) study. The CABLE study is a significant, independent cohort that aims to identify genetic and environmental factors influencing AD biomarkers and their application in the early diagnosis among the northern Han Chinese population [33, 34]. Included in the population aged between 40 and 90. The Qingdao Municipal Hospital’s Institutional Ethics Committee approved the CABLE study, which was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written consent was provided by all participants or their proxies. More detail was shown in (Supplementary CABLE). The analysis was conducted using standard clinical laboratory procedures in the clinical chemistry department of Qingdao Municipal Hospital, China. We included 535 individuals at baseline providing demographic and clinical characteristics, Serum Complement C1q, CSF biomarkers, and cognitive assessments. The China Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (CM-MMSE) and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) were used for global cognition. 5 participants were considered outliers with baseline CSF biomarker concentrations deviating 5 SD from the overall population means.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted with R v.4.1.0. To examine variations in CSF biomarkers and sociodemographic data, intergroup differences were assessed using chi-square analysis for categorical data, one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) for normally distributed data, and the Mann–Whitney U test for data not normally distributed. Furthermore, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was employed to examine if the dependent and independent variables did not follow a normal distribution. In cases where the dependent variable exhibited a skewed distribution, we applied normalization using the “car” package in R. Specifically, we first performed a log10 transformation to reduce skewness and approximate a normal distribution. Subsequently, we used the scale() function to compute Z-scores, standardizing the values by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation. After adjusting for potential confounding factors, we used the one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) for further comparisons, followed by Fisher’s LSD as a post hoc analysis. The associations of CSF and Serum C1q with CSF biomarkers and cognition were explored utilizing multiple linear regression (MLR), accounting for age, sex, years of education, and APOE ɛ4 allele. Afterwards, we examined if baseline among ADNI participants’ CSF C1q levels was associated with longitudinal change in ADAS-Cog 13 and CSF sTREM2, Aβ42, T-tau, and P-tau. This was done using a multiple linear mixed model, accounting for follow-up time, random slope, intercept, age, gender, years of education, and APOE ɛ4 allele. Selected parameters included in the analysis had follow-up measurements spanning 5 years (Supplementary Table 1).

Finally, the structural equation model (SEM) and mediation analyses were undertaken in the study according to the reported results of animal experiments [35, 36]. In hypothesis, we examined whether the relationship between CSF Aβ42 and C1q was mediated by CSF sTREM2-GFAP, which primarily reflects microglial activation and astrocyte reactivation. A second mediation model was employed to investigate if CSF C1q mediated the relationship between CSF sTREM2-GFAP and P-tau/T-tau. The goal of the series mediation model was to determine if CSF sTREM2/GFAP and C1q mediated the relationships between CSF Aβ42 and CSF P-tau/T-tau. The fourth mediation model investigated the possibility that CSF C1q and P-tau/T-tau mediated the relationship between CSF sTREM2/GFAP and cognition. The final mediation model investigated whether the association between CSF Aβ42 and cognition was mediated by CSF sTREM2, GFAP, C1q, and P-tau/T-tau. According to the actual condition, we implemented the hypothesis only If each mediation model requirement must be reached that the independent variable, the intermediate variable, and the dependent variable were correlated. Additionally, in the regression model, the association between the independent and dependent variables weakens when the mediator was included. Significance was determined through 10,000 bootstrapped resamples, and we calculated the attenuation or indirect effects. As with the previous MLR model, each mediation model pathway was controlled for the same covariates. Finally, the sensitivity analyses were conducted by using CSF C1q B_VPGLYYFTYHASSR for main analyses then reproduced by C1q B_LEQGENVFLQATDK [31].

In our analysis, we performed a single-step mediation analysis in R, which provided the mediation proportions along with standardized β values. For the multi-step mediation analysis, we used SPSS, and structural equation model was conducted using SmartPLS. A two-sided p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The “lmer”, “lme4”, “corrplot”, “lavaan”, “ggplot2”, and “car” packages in R version 4.1.0 software were used to perform the all above analyses.

Results

Basic characteristics and intergroup comparisons

The demographic, clinical, and biomarker characteristics of all the participants from ADNI and CABLE are shown in Table 1. As for the ADNI cohort, the 217 participants consist of 43 at stage 0, 31 at stage 1, 113 at stage 2, and 30 with SNAP. The average age of ADNI participants was 75.23 ( ± 6.64) years, and the female proportion was 40.1%. Significant differences were found among the four distinct A/T/N classifications in APOE4 allele, ADAS-Cog13 scores and CSF levels of C1q (both two peptide segments), sTREM2 and T-tau, but not in age, gender, and years of education (Table 1). As for the CABLE cohort, the 535 participants consist of 199 at stage 0, 127 at stage 1, 51 at stage 2, and 158 with SNAP. The CABLE cohort had a female proportion of 37%, a mean age of 62.13 ( ± 9.97) years. Different A/T/N groups showed significant intergroup differences in cognition and CSF biomarkers. At baseline, late-life and male groups showed higher levels of CSF C1q B_VPGLYYFTYHASSR, while only the male group exhibited higher levels of CSF C1q B_ LEQGENVFLQATDK (Supplementary Figure 1). The female participants also had higher baseline serum C1q than male participants (Supplementary Figure 2). In our ADNI cohort, the levels of CSF C1q (both peptide segments), CSF GFAP, and sTREM2 were positively correlated with age (Supplementary Table 2); in our CABLE cohort, the levels of serum C1q and CSF sTREM2 (Supplementary Table 3) were also positively correlated with age, suggesting that neuroinflammation is a characteristic of aging [37].

Dynamic changes of CSF C1q levels

The A+ group exhibited lower CSF C1q levels than the A- groups, while T+ and N+ groups had higher CSF C1q levels. To evaluate the associations of CSF C1q with Aβ deposition, tau pathology and neurodegeneration, we analyzed the changes of CSF C1q levels across the four stages of AD (stage 0; stage 1; stage 2; SNAP). One-way ANCOVA results revealed substantial variations in CSF C1q levels across the four stage groups. Intergroup comparisons indicated that the stage 1 group had notably lower CSF C1q levels than the other three groups. To be specific, the stage1 (P = 0.013), the stage 2 (P = 0.017) and the SNAP (P < 0.001) groups exhibited significantly higher CSF C1q levels relative to the stage 1 group (Fig. 1). This suggests that during the amyloid pathology stage, CSF C1q levels decrease as CSF Aβ levels increase, whereas in the downstream tau pathology and neurodegeneration stages, CSF C1q levels increase as CSF T-tau or P-tau levels increase. The CSF C1q levels change following alterations in brain amyloidosis and neuronal injury markers.

Notes: Levels of Transformed CSF C1q were significantly lower in A+ (A), T- (B), N- (C), and lowest in 1 group (D). CSF C1q levels fitted the normal distribution after log10 transformation and then standardized by z-scale. P values were computed with the One-way ANCOVA for comparison of means while Fisher’s LSD was employed for post hoc test. Models included age, gender, education, APOE ε4 status. Significant effects: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Abbreviations: CSF cerebrospinal fluid, C1q Complement 1q: B_VPGLYYFTYHASSR, AD Alzheimer Disease, APOE apolipoprotein E, A amyloidosis, T tau pathology, N neurodegeneration, 0/1/2 stage 0/1/2, SNAP Suspected Non-AD Pathology.

Associations of CSF C1q with AD biomarkers and cognition

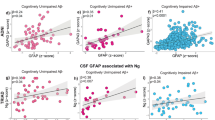

We initially explored the associations between CSF C1q and CSF biomarkers. The relationships of CSF C1q with CSF sTREM2, GFAP and CSF AD core markers were assessed using linear regression models adjusted for age, gender, educational level, and APOE ε4 carrier status. Our study on the ADNI participants showed that increased CSF C1q was associated with higher levels of CSF sTREM2 (β = 0.601, p < 0.001), GFAP (β = 0.337, p < 0.001), Aβ42 (β = 0.274, P < 0.001), P-tau (β = 0.335, P < 0.001) and T-tau (β = 0.390, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A–E). These findings suggest that higher CSF C1q correlates with higher levels of neuroinflammation, Aβ and tau pathology, implying that C1q may respond early to the initial signs of neurodegeneration. We found no meaningful association between CSF C1q levels and ADAS-Cog13 scores (Supplementary Table 4). Our longitudinal analysis revealed that elevated baseline CSF C1q levels were significantly associated with slower increases in CSF T-tau (β = −4.684, P = 0.033) and ADAS-Cog 13 scores (β = −1.204, P = 0.001) (Supplementary Table 5).

Levels of CSF C1q were positively associated with CSF sTREM2 (A), GFAP (B), Aβ42 (C), as well as higher levels of CSF P-tau (D) and T-tau (E). Measures were fitted the normal distribution after log10 transformation and then standardized by z-scale. Multiple linear regression was adjusted for age, gender, educational level, and APOE ε4 carrier status. Significant effects (P < 0.05) are shown in bold. Abbreviations: CSF cerebrospinal fluid, C1q Complement 1q: B_VPGLYYFTYHASSR, ADAS Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale, APOE apolipoprotein E, Aβ42 Amyloid-42, P-tau phosphorylated-tau, T-tau total-tau, sTREM2 soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2, GFAP glial fibrillary acidic protein.

CSF C1q and sTREM2 mediated the associations between amyloid pathology and tau pathology

We found significant associations of baseline CSF C1q with CSF AD core biomarkers, sTREM2 and GFAP, as shown in Supplementary Tables 6 and 7. Thus, we employed two possible mediation pathway analyses: (1) CSF Aβ42 → CSF sTREM2 → CSF C1q → CSF P-tau (Indirect effect, IE = 0.028, P = 0.016) (Fig. 3A); (2) CSF sTREM2→ CSF GFAP → CSF C1q → CSF P-tau (IE = 0.015, P = 0.031) (Fig. 3B) (Supplementary Table 7, 8). CSF C1q affected the process from Aβ to tau pathology in AD by regulating microglial activation and astrocyte reactivation (i.e., astrocyte-microglia crosstalk) (Fig. 3C) [35, 36].

A, B. The mediation analysis explored the influences of CSF sTREM2 and C1q on the association between CSF Aβ42 and p-tau: (A) CSF Aβ42 → CSF sTREM2 → CSF C1q→ CSF P-tau; (B) CSF sTREM2 → CSF GFAP → CSF C1q → CSF P-tau. Partial least squares structural equation modeling was used to examine priori hypothesized biomarker pathways. P-values for mediation effects were calculated by a bootstrap test with 10,000 resampling iterations. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. C Schematic representation of CSF C1q affected the process from Aβ to tau pathology in AD by regulating microglial activation and astrocyte reactivation (i.e. astrocytes-microglia crosstalk).

To further assess the robustness of these mediation effects, we conducted a single-step mediation analysis to supplement our findings, encompassing: (1) CSF Aβ42 → CSF sTREM2 → CSF C1q; (2) CSF sTREM2 → CSF C1q → CSF P-tau; (3) CSF sTREM2 → CSF GFAP → CSF C1q; (4) CSF GFAP → CSF C1q → CSF P-tau. In the first mediation model, CSF sTREM2 significantly mediated the association between CSF Aβ42 and CSF C1q (IE = 0.136, proportion = 43.9%, P < 0.001). In the second model, CSF C1q mediated the association between CSF sTREM2 and CSF P-tau (IE = 0.124, proportion = 42.8%, P = 0.003). n the third model, CSF GFAP partially mediated the association between CSF sTREM2 and CSF C1q (IE = 0.054, proportion = 10.1%, P = 0.005). And in the fourth model, CSF C1q partially mediated the association between CSF GFAP and CSF P-tau (IE = 0.085, proportion = 24.3%, P < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 9). Building upon these single-step mediation models, we further examined the overall pathway and found that CSF C1q and sTREM2 jointly mediated the relationship between CSF Aβ42 and CSF P-tau (β = −0.270, P < 0.001) (Fig. 4).

A, B Three mediation pathways were conducted between CSF Aβ42 and p-tau/t-tau: (1) Aβ42 → sTREM2 → C1q → p-tau/t-tau; (2) Aβ42 → sTREM2 → p-tau/t-tau; (3) Aβ42 → C1q → p-tau/t-tau. C, D Three mediation pathways were assessed between CSF sTREM2 and p-tau/t-tau: (1) sTREM2 → GFAP →C1q → p-tau/t-tau; (2) sTREM2 →GFAP →C1q; (3) sTREM2 → GFAP → p-tau/t-tau. These three pathways are presented using blue, yellow, and red lines. All mediation paths are adjusted by covariates (age, sex, education, and APOE ɛ4 status). The β coefficients in each path and P-values for mediation effects were calculated by a bootstrap test with 10,000 resampling iterations. The dotted line indicates that the indirect effect is not significant (P ≥ 0.05), and the solid line indicates that the indirect effect is significant (P < 0.05). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

Subgroup analyses

Interaction analyses revealed that the relationship of CSF C1q with sTREM2 was affected by tau pathology (β = −0.256, P = 0.030) and neurodegeneration (β =−0.243, P = 0.038) (Supplementary Table 10). Then additional subgroup analyses were conducted based on age, gender, education, APOE ɛ4 status and cognitive diagnosis. CSF C1q was only associated with CSF Aβ42 (β = 0.699, p = 0.012), sTREM2 (β = 0.651, p = 0.028) and GFAP (β = 0.615, p = 0.015) in mid-life group rather than late-life group (Supplementary Table 11). These associations were more pronounced in male, well-educated (Education year 13 years or more), and APOE ε4 carrier, A-, T + , and N+ groups (Supplementary Table 12). Besides, there was a correlation between CSF sTREM2 and CSF C1q in CN, MCI and AD groups, and the correlation was strongest in MCI subgroup (Supplementary Table 13).

Sensitivity analysis

We repeated sensitivity analyses for another peptide C1q B_ LEQGENVFLQATDK, yielding similar results to those for C1q B_VPGLYYFTYHASSR. In our sensitivity analysis, CSF C1q was still positively associated with tau pathology and neurodegeneration (Supplementary Figure 3); baseline CSF C1q was still significantly correlated with CSF CSF sTREM2, GFAP, Aβ42, P-tau and T-tau (all P < 0.010), and not with ADAS-Cog13 scores (Supplementary Table 14); higher baseline CSF C1q was still significantly associated with slower increases in P-tau (β = −0.681, P = 0.022), T-tau (β = −8.359, P = 0.006), and ADAS-Cog 13 scores (β = −1.184, P = 0.026) (Supplementary Table 15). In the sensitivity analysis, only one possible mediation pathway could be replicated: CSF Aβ42 → CSF sTREM2 → CSF C1q → CSF P-tau (IE = −0.236, P < 0.001) (Supplementary Figure 4). Subgroup analyses showed more significant association with AD biomarkers in male, A-, T + , and N+ subgroups. Besides, this connection was more substantial in mid-life, well-educated, and APOE ε4 carriers. CSF sTREM2 was associated with CSF C1q across CN, MCI, and AD groups, with the strongest association observed in the MCI subgroup (Supplementary Tables 16, 17, 18). Notably, both peptides were significant in the MCI.

Associations of serum C1q with cognition and CSF AD biomarkers

No difference in baseline serum C1q was found across the different groups divided based on the A/T/N classification scheme (Supplementary Figure 5). In the multiple linear regression model that accounted for age, gender, years of education and APOE ɛ4 status, serum C1q was still positively related to CSF sTREM2 levels (β = 0.097, P = 0.029) (Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 19). Interestingly, the association between serum C1q and CSF sTREM2 was significant in late-life, ill-educated (Education year less then 13 years), APOE ε4 (-), A-, and N- groups. Additionally, serum C1q was negatively correlated with levels of CSF P-tau (β = −0.118, P = 0.038) and T-tau (β = −0.116, P = 0.043) (Supplementary Table 20).

Discussion

In this research, we observed that CSF and serum C1q, as well as CSF sTREM2 levels were directly correlated with age. CSF C1q levels were dynamic during the AD pathological processes. We are the first population-based study which showed that CSF C1q levels were associated with neuroinflammation, CSF biomarkers, and cognitive changes. Furthermore, our mediation analysis revealed that CSF C1q and sTREM2 mediated the effect of CSF Aβ42 on CSF P-tau. These findings indicate that CSF C1q levels may be crucial in tau pathology and neurodegeneration through microglia–astrocyte communication in AD.

Interestingly, we observed that female participants had higher baseline serum C1q levels than males, whereas their CSF C1q levels were lower. This difference may be attributed to the interplay of immune regulation, hormonal influence, blood-brain barrier (BBB) function, and genetic factors. First, in the CNS, C1q is primarily produced by microglia, whereas in the peripheral nervous system, it is mainly synthesized by the liver and immune cells. This differential regulation may contribute to the observed variation in CSF and serum C1q levels. Second, hormonal influences, particularly estrogen and androgens, play a crucial role. Sex-related differences in complement-mediated immunity involving C1q and C3b have been observed in humans and rhesus macaques, suggesting distinct glycan recognition and balance between the classical and alternative activation pathways [38]. Studies suggest that males have greater early complement activation, whereas females show stronger antibody-mediated activation. Estrogen may further modulate C1q levels by regulating complement gene expression and immune factor recruitment in the CNS and periphery [39]. And estrogen can also suppress the phagocytosis of microglia [40]. Third, BBB integrity differs between sexes. Estrogen has protective effects on BBB permeability [41], and its decline with age or menopause may alter CNS immune responses [42]. Female-specific mechanisms may restrict CNS C1q production while permitting higher systemic levels. Additionally, X-linked genes may underlie sex differences in immune regulation and BBB function [43, 44]. These factors could influence complement activation and immune responses, further explaining the sex-specific divergence in C1q levels across compartments.

Consistent with previous studies, CSF and serum C1q levels might be pro-aging factors, indicating that neuroinflammation is a characteristic of aging [37]. Changes associated with aging might initiate inflammatory complement cascades [45]. Prior research only reported a strong association between phospho-tau levels and C1q levels, and tau pathology appears to more potently induce C1q accumulation at synapses than β-amyloidosis [46]. Our study builds on previous findings by revealing dynamic changes in CSF C1q levels across AD pathology. In the absence of tau deposition and neurodegeneration, Aβ pathology is linked to lower CSF C1q, while tau pathology and neurodegeneration are associated with higher levels, suggesting a role for microglial C1q in AD-related inflammation and pathogenesis. Our findings showed that elevated CSF C1q levels were associated with tau pathology or neurodegeneration, even in the absence of Aβ pathology. This supports the hypothesis that microglial and astrocytic activation occurs downstream of Aβ deposition and precedes tau accumulation [47]. Therefore, it is worthwhile to further examine the changes in peripheral and CSF C1q in AD continuum to ascertain whether C1q could be a cause or a consequence of neurodegeneration. Another interesting observation is that CSF C1q is positively correlated with baseline tau levels but negatively correlated with longitudinal tau changes. The complement system’s impact on tau pathology likely varies over time. In early AD, complement activation worsens tau pathology in mouse models, though the mechanisms remain unclear [48]. C1q is highly expressed in the adult brain, particularly in the hippocampus, and its levels increase with aging [49]. In amyloid pathology mouse models, C1q is upregulated even before amyloid plaque formation and is localized to synapses [16]. Early C1q accumulation may promote tau-related neurodegeneration, explaining its positive correlation with baseline tau levels. Over time, however, C1q might aid in clearing tau via immune mechanisms. C1q deficiency has been shown to reduce astrocyte-synapse interactions, impair glial synaptic engulfment, and preserve synaptic density in tauopathy models [46]. Astrocytes can eliminate synapses in a C1q-dependent manner, leading to pathological synapse loss, and their phagocytic activity may compensate for microglial dysfunction [35]. Additionally, C1q is involved in tagging apoptotic cells and cellular debris for clearance via complement activation, promoting downstream C3 deposition and phagocytosis [50]. This function may help reduce tau accumulation in the long term, potentially explaining the negative correlation between CSF C1q and longitudinal changes in tau. Taken together, these findings suggest that while C1q may initially contribute to tau pathology and neurodegeneration, it might later facilitate clearance mechanisms that slow tau progression. Further research is needed to elucidate the precise stage-dependent roles of C1q in tau pathology.

Our study found significantly positive associations of CSF C1q with CSF Aβ42, P-tau and T-tau. Compelling evidence has revealed that the complement system especially the classical complement pathway is essential in AD pathogenesis [51, 52]. This study found that CSF C1q and CSF sTREM2 mediated the association between CSF Aβ42 and P-tau, supporting the hypothesis that C1q promotes an inflammatory state and plays a detrimental role in the progression of AD pathology through complement activation and recruitment of activated glial cells [36, 53]. The amyloid cascade hypothesis for AD suggests that the buildup of Aβ in the brain is the first step in the development of AD, leading to tau pathology, synaptic loss, and cognitive decline [54]. Compelling evidence has shown that during AD progression, microglial activation increases with Aβ plaque metabolism and its distribution in brain regions mirrors the spread of tau protein tangles [55, 56].

C1q binds to fibrillar Aβ and initiates the activation of the classical complement pathway. C1q opsonizes synapses affected by tau protein, inducing subsequent microglial phagocytosis [45]. In AD mouse models, C1q is essential for the elimination of synapses induced by soluble β-amyloid oligomers before the formation of visible plaques, marking synapses and indicating its involvement in early AD pathology [16]. Our longitudinal analysis showed that increased baseline CSF C1q concentrations were associated with changes in tau pathology and cognitive alterations. However, the effect of neuroinflammation on cognition is complex. C1q-mediated synaptic pruning by microglia leads to synaptic loss and exacerbates cognitive dysfunction [57]. The communication between astrocytes and microglia is fundamental to neuronal function and dysfunction, and astrocyte dysfunction can exacerbate neurodegeneration, contributing to cognitive decline in AD [7]. The reactive astrocytes and microglia were linked to the C1q-positive Aβ plaques are frequently connected to degenerative processes [52, 58, 59]. The brain’s microglia are a primary source of both sTREM2 and C1q [46, 60, 61]. According to previous research, astrocytes interact with and remove synapses in a manner dependent on C1q, leading to the loss of pathological synapses [35]. The phagocytic activity of astrocytes can compensate for microglial dysfunction [35]. Although astrocytes play a crucial role in maintaining the BBB, CNS immune homeostasis, normal neuronal communication, and synaptic plasticity [62, 63], their mechanisms of action in the pathogenesis of AD remain unclear. Under pathological conditions, astrocytes which undergo various morphological and functional changes are collectively termed reactive astrocytes. Reactive astrocytes are involved in amyloid and tau protein pathology in CNS [64, 65]. In AD, reactive astrocytes secrete extracellular vesicles (EVs) that can affect neuronal mitochondria. Research suggests that Aβ induces acid sphingomyelinase (A-SMase) activity, which triggers ceramide production, leading to microglial release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (C1q, TNF-α, IL-1α). These cytokines induce the reactive astrocyte phenotype and promote the secretion of ceramide-enriched EVs, which may further propagate neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration [66]. Reactive astrocytes overexpress GFAP, which is recognized as a potential AD biomarker [19]. Research has shown that astrocytes could release transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), which might enhance C1q expression and promote microglial phagocytosis [67]. Astrocytic phagocytosis can compensate for microglial dysfunction. Additionally, age-related increases in astrocytic and microglial proteins in TauP301S synapse fractions are C1q-dependent [35]. Astrocytes regulate microglial phenotype and function, from motility to phagocytosis, and microglia also can determine the functions of reactive astrocytes, ranging from neuroprotective to neurotoxic [11, 68, 69]. In the ADNI cohort, CSF C1q was associated with CSF sTREM2, GFAP, and AD core biomarkers, whereas in the CABLE cohort, serum C1q correlated only with CSF sTREM2. This reflects the potential differences between peripheral and CSF C1q in their effects on AD pathology, for which astrocytes might be an explanation. Clarifying the mechanisms linking CSF C1q, neuroinflammation, and AD pathology may aid in developing targeted therapies.

Our results could impact the extension of the AT(N) system to the ATX(N) system, accommodating our advancing understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms within the AD continuum [70]. Given that the ATX(N) system’s ‘X’ component suggests potential biomarkers for other pathophysiological pathways. Excitingly, the 2023 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) proposed inflammatory/immune (I) biomarkers for the staging and outcomes of AD, which are currently reflected only by plasma or CSF GFAP [71].

Preventive methods targeting neuroinflammation may be very beneficial for patients with Aβ deposition who do not have tau pathology, as our findings indicate that CSF C1q is crucial in driving the progression of downstream events that follow Aβ pathology. Recent studies using new PET tracers have observed that astrocyte reactivity is highly and selectively associated with Aβ deposition and is correlated with a reduction in Aβ deposits in the sensory cortices and temporal [72, 73]. Besides, the results of subgroup analyses suggested the associations of CSF C1q with neuroinflammation and AD pathology were more significant in mid-life, male, well-educated, and APOE ε4 carrier subgroups. On the contrary, the association between serum C1q and CSF sTREM2 was significant in late-life, ill-educated, APOE ε4 (-), A-, and N- subgroups. This once again illustrates the difference in the potential detection effect of C1q in peripheral blood and cerebrospinal fluid, which may also be caused by ethnic differences. And it is necessary to develop individualized prevention and treatment programs for different populations in the future.

This research possesses several notable strengths. It is the first research to thoroughly examine the associations of C1q with GFAP, sTREM2 and AD pathology in a well-characterized population-based cohort. CSF and serum C1q were significantly correlated with CSF sTREM2 in 2 cohorts of different races. To further ensure the high caliber of our study, we classified AD biomarkers using the AD diagnostic criteria from the NIA-AA study. The analyses of two C1q peptides and the consideration of the concentration of C1q in comorbidity made our results more stable. Preclinical studies have shown that blocking C1q can prevent synaptic dysfunction and cognitive decline in AD models, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target. Nonetheless, it is crucial to recognize the limitations of our present study. First, there only 2 peptide fragments of CSF C1q. More types of CSF C1q peptides and the overall concentration of C1q need to be further studied. Second, this study’s C1q data came from the Biomarkers Consortium Project, which was intended as an exploratory study for generating hypotheses and developing models, rather than for hypothesis testing or model validation. Third, in future studies, we plan to further investigate this issue in additional cohorts and across different stages of cognitive impairment. Finally, the mediating models used in this observational study clearly reveal relationships between C1q, microglial and astrocyte activation, AD pathology, and cognitive function, but they cannot establish cause-and-effect relationships. Future studies should therefore explore the detailed mechanisms behind our findings through large-scale cohorts and high-sensitivity CSF C1q assays, as well as further cell and animal studies.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that CSF C1q was significantly correlated with CSF GFAP and sTREM2, and mediated the relationship between Aβ pathology and tau pathology. This suggests that C1q could play a key role in the spread from Aβ pathology to tau pathology and ultimately to cognitive decline. CSF C1q changed dynamically at different stages of AD pathology and increased with age. These findings have profound consequences for clinical practice and may prompt future research to explore elevating C1q levels as a potential therapeutic approach to mitigate the progression of AD pathology and cognitive decline.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Long JM, Holtzman DM. Alzheimer disease: an update on pathobiology and treatment strategies. Cell. 2019;179:312–39.

Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer’s disease is a synaptic failure. Science. 2002;298:789–91.

Singh D. Astrocytic and microglial cells as the modulators of neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19:206.

McGeer PL, Itagaki S, Tago H, McGeer EG. Reactive microglia in patients with senile dementia of the Alzheimer type are positive for the histocompatibility glycoprotein HLA-DR. Neurosci Lett. 1987;79:195–200.

Zotova E, Holmes C, Johnston D, Neal JW, Nicoll JA, Boche D. Microglial alterations in human Alzheimer’s disease following Aβ42 immunization. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2011;37:513–24.

Shao Y, Gearing M, Mirra SS. Astrocyte-apolipoprotein E associations in senile plaques in Alzheimer disease and vascular lesions: a regional immunohistochemical study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:376–81.

Uddin MS, Lim LW. Glial cells in Alzheimer’s disease: from neuropathological changes to therapeutic implications. Ageing Res Rev. 2022;78:101622.

Linnerbauer M, Wheeler MA, Quintana FJ. Astrocyte crosstalk in CNS inflammation. Neuron. 2020;108:608–22.

Krance SH, Wu CY, Zou Y, Mao H, Toufighi S, He X, et al. The complement cascade in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:5532–41.

Stevens B, Allen NJ, Vazquez LE, Howell GR, Christopherson KS, Nouri N, et al. The classical complement cascade mediates CNS synapse elimination. Cell. 2007;131:1164–78.

Liddelow SA, Guttenplan KA, Clarke LE, Bennett FC, Bohlen CJ, Schirmer L, et al. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature. 2017;541:481–7.

Peng X, Ju J, Li Z, Liu J, Jia X, Wang J, et al. C3/C3aR bridges spinal astrocyte-microglia crosstalk and accelerates neuroinflammation in morphine-tolerant rats. CNS Neurosci Therapeutics. 2025;31:e70216.

Zhang W, Chen Y, Pei H. C1q and central nervous system disorders. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1145649.

Li S, Li M, Li G, Li L, Yang X, Zuo Z, et al. Physical exercise decreases complement-mediated synaptic loss and protects against cognitive impairment by inhibiting microglial Tmem9-ATP6V0D1 in Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Cell. 2025;24:e14496.

Zhong L, Sheng X, Wang W, Li Y, Zhuo R, Wang K, et al. TREM2 receptor protects against complement-mediated synaptic loss by binding to complement C1q during neurodegeneration. Immunity. 2023;56:1794–808.e8.

Hong S, Beja-Glasser VF, Nfonoyim BM, Frouin A, Li S, Ramakrishnan S, et al. Complement and microglia mediate early synapse loss in Alzheimer mouse models. Science. 2016;352:712–6.

Fakhoury M. Microglia and astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease: implications for therapy. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16:508–18.

Wang ZB, Ma YH, Sun Y, Tan L, Wang HF, Yu JT. Interleukin-3 is associated with sTREM2 and mediates the correlation between amyloid-β and tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19:316.

Carter SF, Herholz K, Rosa-Neto P, Pellerin L, Nordberg A, Zimmer ER. Astrocyte biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Mol Med. 2019;25:77–95.

Suárez-Calvet M, Kleinberger G, Araque Caballero M, Brendel M, Rominger A, Alcolea D, et al. sTREM2 cerebrospinal fluid levels are a potential biomarker for microglia activity in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease and associate with neuronal injury markers. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8:466–76.

Aisen PS, Petersen RC, Donohue M, Weiner MW. Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative 2 clinical core: progress and plans. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2015;11:734–9.

Su D, Zhang Y, Bi F, Xiao B. [Proteomic analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid from patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis based on tandem mass spectrometry technique]. Nan fang yi ke da xue xue bao = J South Med Univ. 2019;39:428–36.

Bowness P, Davies K, Norsworthy P, Athanassiou P, Taylor-Wiedeman J, Borysiewicz L, et al. Hereditary C1q deficiency and systemic lupus erythematosus. QJM. 1994;87:455–64.

Mook-Kanamori BB, Brouwer MC, Geldhoff M, van der Ende A, van de Beek D. Cerebrospinal fluid complement activation in patients with pneumococcal and meningococcal meningitis. J Infect. 2014;68:542–7.

Depboylu C, Schäfer MK-H, Arias-Carrión O, Oertel WH, Weihe E, Höglinger GU, et al. Possible involvement of complement factor C1q in the clearance of extracellular neuromelanin from the substantia nigra in Parkinson disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2011;70:125–32.

Yoshikura N, Kimura A, Hayashi Y, Inuzuka T. Anti-C1q autoantibodies in patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. J Neuroimmunol. 2017;310:150–7.

Shen L, Wang S, Ling Y, Liang W. Association of C1q/TNF-related protein-1 (CTRP1) serum levels with coronary artery disease. J Int Med Res. 2019;47:2571–9.

Hansson O, Seibyl J, Stomrud E, Zetterberg H, Trojanowski JQ, Bittner T, et al. CSF biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease concord with amyloid-β PET and predict clinical progression: A study of fully automated immunoassays in BioFINDER and ADNI cohorts. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018;14:1470–81.

Suárez-Calvet M, Morenas-Rodríguez E, Kleinberger G, Schlepckow K, Araque Caballero M, Franzmeier N, et al. Early increase of CSF sTREM2 in Alzheimer’s disease is associated with tau related-neurodegeneration but not with amyloid-β pathology. Mol Neurodegener. 2019;14:1.

Suárez-Calvet M, Capell A, Araque Caballero M, Morenas-Rodríguez E, Fellerer K, Franzmeier N, et al. CSF progranulin increases in the course of Alzheimer’s disease and is associated with sTREM2, neurodegeneration and cognitive decline. EMBO Mol Med. 2018;10:e9712.

Picard C, Nilsson N, Labonté A, Auld D, Rosa-Neto P, Ashton NJ, et al. Apolipoprotein B is a novel marker for early tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2022;18:875–87.

Spellman DS, Wildsmith KR, Honigberg LA, Tuefferd M, Baker D, Raghavan N, et al. Development and evaluation of a multiplexed mass spectrometry based assay for measuring candidate peptide biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) CSF. Proteom Clin Appl. 2015;9:715–31.

Xu W, Tan L, Su BJ, Yu H, Bi YL, Yue XF, et al. Sleep characteristics and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease pathology in cognitively intact older adults: The CABLE study. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2020;16:1146–52.

Ma LZ, Tan L, Bi YL, Shen XN, Xu W, Ma YH, et al. Dynamic changes of CSF sTREM2 in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: the CABLE study. Mol Neurodegeneration. 2020;15:25.

Dejanovic B, Wu T, Tsai MC, Graykowski D, Gandham VD, Rose CM, et al. Complement C1q-dependent excitatory and inhibitory synapse elimination by astrocytes and microglia in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Nat Aging. 2022;2:837–50.

Guan PP, Ge TQ, Wang P. As a potential therapeutic target, C1q induces synapse loss via inflammasome-activating apoptotic and mitochondria impairment mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2023;18:267–84.

Sjögren M, Vanderstichele H, Agren H, Zachrisson O, Edsbagge M, Wikkelsø C, et al. Tau and Abeta42 in cerebrospinal fluid from healthy adults 21-93 years of age: establishment of reference values. Clin Chem. 2001;47:1776–81.

Kelkar NS, Goldberg BS, Dufloo J, Bruel T, Schwartz O, Hessell AJ, et al. Sex- and species-associated differences in complement-mediated immunity in humans and rhesus macaques. mBio. 2024;15:e0028224.

Kumwenda P, Cottier F, Hendry AC, Kneafsey D, Keevan B, Gallagher H, et al. Estrogen promotes innate immune evasion of Candida albicans through inactivation of the alternative complement system. Cell Rep. 2022;38:110183.

Wu D, Bi X, Chow KH. Identification of female-enriched and disease-associated microglia (FDAMic) contributes to sexual dimorphism in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2024;21:1.

Shao X, Shou Q, Felix K, Ojogho B, Jiang X, Gold BT, et al. Age-related decline in blood-brain barrier function is more pronounced in males than females in parietal and temporal regions. eLife. 2024;13:RP96155.

Bake S, Sohrabji F. 17beta-estradiol differentially regulates blood-brain barrier permeability in young and aging female rats. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5471–5.

Pinheiro I, Dejager L, Libert C. X-chromosome-located microRNAs in immunity: might they explain male/female differences? The X chromosome-genomic context may affect X-located miRNAs and downstream signaling, thereby contributing to the enhanced immune response of females. BioEssays: News and Reviews in Molecular, Cell Developmental Biology. 2011;33:791–802.

Spolarics Z. The X-files of inflammation: cellular mosaicism of X-linked polymorphic genes and the female advantage in the host response to injury and infection. Shock. 2007;27:597–604.

Datta D, Leslie SN, Morozov YM, Duque A, Rakic P, van Dyck CH, et al. Classical complement cascade initiating C1q protein within neurons in the aged rhesus macaque dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17:8.

Dejanovic B, Huntley MA, De Mazière A, Meilandt WJ, Wu T, Srinivasan K, et al. Changes in the synaptic proteome in tauopathy and rescue of tau-induced synapse loss by C1q antibodies. Neuron. 2018;100:1322–36.e7.

Selkoe DJ, Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8:595–608.

Hansen DV, Hanson JE, Sheng M. Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:459–72.

Stephan AH, Madison DV, Mateos JM, Fraser DA, Lovelett EA, Coutellier L, et al. A dramatic increase of C1q protein in the CNS during normal aging. J Neurosci. 2013;33:13460–74.

Gasque P. Complement: a unique innate immune sensor for danger signals. Mol Immunol. 2004;41:1089–98.

Tenner AJ. Complement-mediated events in Alzheimer’s disease: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. J Immunol. 2020;204:306–15.

Afagh A, Cummings BJ, Cribbs DH, Cotman CW, Tenner AJ. Localization and cell association of C1q in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Exp Neurol. 1996;138:22–32.

Fonseca MI, Kawas CH, Troncoso JC, Tenner AJ. Neuronal localization of C1q in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;15:40–6.

Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–5.

Pascoal TA, Benedet AL, Ashton NJ, Kang MS, Therriault J, Chamoun M, et al. Microglial activation and tau propagate jointly across Braak stages. Nat Med. 2021;27:1592–9.

Morenas-Rodríguez E, Li Y, Nuscher B, Franzmeier N, Xiong C, Suárez-Calvet M, et al. Soluble TREM2 in CSF and its association with other biomarkers and cognition in autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease: a longitudinal observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21:329–41.

Chung HY, Wickel J, Hahn N, Mein N, Schwarzbrunn M, Koch P, et al. Microglia mediate neurocognitive deficits by eliminating C1q-tagged synapses in sepsis-associated encephalopathy. Sci Adv. 2023;9:eabq7806.

Dickson DW. The pathogenesis of senile plaques. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:321–39.

Griffin WS, Sheng JG, Royston MC, Gentleman SM, McKenzie JE, Graham DI, et al. Glial-neuronal interactions in Alzheimer’s disease: the potential role of a ‘cytokine cycle’ in disease progression. Brain Pathol. 1998;8:65–72.

Frank S, Burbach GJ, Bonin M, Walter M, Streit W, Bechmann I, et al. TREM2 is upregulated in amyloid plaque-associated microglia in aged APP23 transgenic mice. Glia. 2008;56:1438–47.

Lue LF, Schmitz CT, Serrano G, Sue LI, Beach TG, Walker DG. TREM2 protein expression changes correlate with Alzheimer’s disease neurodegenerative pathologies in post-mortem temporal cortices. Brain Pathol. 2015;25:469–80.

Yao Y, Chen ZL, Norris EH, Strickland S. Astrocytic laminin regulates pericyte differentiation and maintains blood brain barrier integrity. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3413.

Santello M, Toni N, Volterra A. Astrocyte function from information processing to cognition and cognitive impairment. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22:154–66.

Benedet AL, Milà-Alomà M, Vrillon A, Ashton NJ, Pascoal TA, Lussier F, et al. Differences between plasma and cerebrospinal fluid glial fibrillary acidic protein levels across the alzheimer disease continuum. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78:1471–83.

Ferrari-Souza JP, Ferreira PCL, Bellaver B, Tissot C, Wang YT, Leffa DT, et al. Astrocyte biomarker signatures of amyloid-β and tau pathologies in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:4781–9.

Crivelli SM, Quadri Z, Vekaria HJ, Zhu Z, Tripathi P, Elsherbini A, et al. Inhibition of acid sphingomyelinase reduces reactive astrocyte secretion of mitotoxic extracellular vesicles and improves Alzheimer’s disease pathology in the 5xFAD mouse. Acta Neuropathologica Commun. 2023;11:135.

Bialas AR, Stevens B. Retraction Note: TGF-β signaling regulates neuronal C1q expression and developmental synaptic refinement. Nat Neurosci. 2022;25:265.

Rueda-Carrasco J, Martin-Bermejo MJ, Pereyra G, Mateo MI, Borroto A, Brosseron F, et al. SFRP1 modulates astrocyte-to-microglia crosstalk in acute and chronic neuroinflammation. EMBO Rep. 2021;22:e51696.

He D, Xu H, Zhang H, Tang R, Lan Y, Xing R, et al. Disruption of the IL-33-ST2-AKT signaling axis impairs neurodevelopment by inhibiting microglial metabolic adaptation and phagocytic function. Immunity. 2022;55:159–73.e9.

Hampel H, Cummings J, Blennow K, Gao P, Jack CR Jr., Vergallo A. Developing the ATX(N) classification for use across the Alzheimer disease continuum. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17:580–9.

Carrillo MC, Masliah E, editors. NIA-AA Revised Clinical Criteria for Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Association International Conference; 2023: ALZ.

Livingston NR, Calsolaro V, Hinz R, Nowell J, Raza S, Gentleman S, et al. Relationship between astrocyte reactivity, using novel (11)C-BU99008 PET, and glucose metabolism, grey matter volume and amyloid load in cognitively impaired individuals. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:2019–29.

Villemagne VL, Harada R, Doré V, Furumoto S, Mulligan R, Kudo Y, et al. Assessing reactive astrogliosis with (18)F-SMBT-1 across the Alzheimer disease spectrum. J Nucl Med. 2022;63:1560–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the researchers and participants in the ADNI initiative. Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf. We express appreciation to contributors of Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database. Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; BristolMyers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hofmann-La Roche Ltd and its afliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfzer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California. The authors thank all participants who donated their brains to the ADNI Neuropathology Core Center. The authors also thank all researchers who collected and processed specimens and performed neuropathological assessments in the ADNI.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32300824, 82271475 and 82201587), Taishan Scholars Program of Shandong Province (tsqn20161078), Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2023MH062), and Medical Science Research Guidance Plan of Qingdao (2021-WJZD001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MST, ZTW and LT conceptualized the study and revised the manuscript. FG, ZHS, YF, ZBW and RJX analyzed and interpreted the data, drafting and revision of the manuscript, and prepared the figures. All authors contributed to the writing and revisions of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by institutional review boards of all participating institutions, including Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board(IRB). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their guardians prior to any study procedures, in accordance with both the Declaration of Helsinki and institutional IRB guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, F., Sheng, ZH., Fu, Y. et al. Complement C1q is associated with neuroinflammation and mediates the association between amyloid-β and tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Transl Psychiatry 15, 247 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03458-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-025-03458-5

This article is cited by

-

Exploring Alzheimer’s diseases with focus on diagnostic strategies targeting amyloid beta 42 (Aβ42)

Discover Neuroscience (2025)