Abstract

The incidence of endometrial cancer (EC) continues to rise. Disulfidptosis, a novel form of cell death, may represent a potential therapeutic target in EC. Through bioinformatic analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database, E2F1 mRNA-stabilizing lncRNA (EMSLR) was identified as a lncRNA related to disulfidptosis in EC. Functional assays, including cell proliferation and xenograft assays, demonstrated that knockdown of EMSLR significantly impeded EC cell proliferation, whereas overexpression of EMSLR promoted cell viability. Additionally, EMSLR was found to be associated with glucose uptake and NADPH production in glucose-restricted culture conditions. Moreover, downregulation of EMSLR markedly increased cell death and induced cytoskeletal collapse under glucose deprivation, as evidenced by F-actin and cell death staining. Notably, we observed a strong correlation between EMSLR and the c-MYC-GLUT1 pathway. Mechanistically, EMSLR was found to mediate the expression and nuclear translocation of c-MYC, thereby regulating the progression of EC and its associated disulfidptosis. In conclusion, EMSLR is identified as a disulfidptosis-related gene in endometrial cancer. Elucidating the function and molecular mechanisms of EMSLR in EC presents a promising avenue for therapeutic intervention in patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Endometrial cancer (EC) is one of the most common gynecological malignances [1]. The 5-year survival rates of patients with advanced tumors, especially stage III/IV, remain only 48% and 15%, respectively [2]. Worse still, the median overall survival (OS) of recurrent/metastatic EC patients is extremely short, less than 15 months [3]. Cell death can be generally classified into apoptosis and necrosis [4]. The understanding of cell death is of great significance for revealing the underlying mechanisms of disease. Disulfidptosis is a novel type of cell death caused by disulfide stress due to excess cystine accumulation [5]. Unlike conventional cell death modes such as apoptosis and ferroptosis, it cannot be inhibited by known cell death inhibitors, nor can it be inhibited by silence of key genes for ferroptosis or apoptosis. Elevated levels of reactive oxy are thought to be oncogenic, causing damage to DNA, proteins and lipids, promoting genetic instability in cancer. But toxic levels of ROS production in cancers are anti-tumourigenic, resulting in an increase of oxidative stress and induction of tumor cell death [6]. Tumor cells require sufficient cysteine to form reduced GSH to maintain stable intracellular ROS levels. Generally, the cystine uptake increases when the cancer cells, those with abnormal expression of cysteine transporter SLC7A11, confront glucose starvation. In the meantime, the insufficient supply of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) also leads to abnormal accumulation of disulfides such as cystine, thus inducing disulfide stress. Disulfide stress triggers the formation of intracellular disulfide bonds amongst actin cytoskeletal proteins, further leading to the collapse of the cytoplasmic membrane and cell death [7]. Disulfidptosis regulators exhibited the highest average SNV frequency in EC tumors [8]. In a pan-cancer disulfidptosis study, lower disulfidptosis levels were observed in EC tissue compared to normal endometrial tissue, and EC patients with higher disulfidptosis risk exhibited better overall survival compared to patients with lower risk [9]. However, the specific molecular mechanism of disulfidptosis in endometrial cancer has not been well understood.

In recent years, the relationship between lncRNA and tumors has received extensive attention. lncRNAs belong to a class of RNAs that are longer than 200 nucleotides and do not participate in coding [10]. It plays an important role in epigenetic regulation, transcriptional regulation and post-transcriptional regulation. Besides, lncRNAS are reported to closely relate to the occurrence, development and prognosis of cancer [11, 12]. Numerous studies have shown that lncRNA can be used as a biomarker and a potential therapeutic target in endometrial cancer [13, 14]. Previously, E2F1 mRNA stabilizing lncRNA (EMSLR) has been reported as cancer stem cell-associated lncRNA in triple-negative breast cancer, suggesting it could serve as a potential prognostic biomarker [15]. In addition, EMSLR was also thought to play an important role in cell cycle regulation [16]. Moreover, EMSLR regulates tumor proliferation and differentiation in lung cancer, and is positively correlated with the expression of c-myc [17]. Importantly, EMSLR has been identified as a disulfidptosis-associated lncRNA in lung cancer [18, 19]. However, the cellular function and molecular mechanism of EMSLR in endometrial cancer are not well understood.

In this study, EMSLR has been identified as a disulfidptosis-related lncRNA through bioinformatics analysis. It is highly expressed in endometrial cancer tissue compared to normal tissue and indicates a poorer prognosis. Mechanistically, EMSLR was found to promote tumor growth and inhibit disulfidptosis via regulating c-MYC in endometrial cancer. It can be a promising target in the treatment of UCEC.

Methods

Data collection

Clinical information and expression profiles of EC patients were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database.

Screen disulfidptosis-related lncRNAs

The disulfidptosis-related lncRNAswere obtained using Pearson correlation analysis (|Pearson R| > 0.35、P < 0.001). The “ggplot2”, “dplyr”, “ggalluvial”, “limma”package were utilized for visualization of disulfidptosis-related lncRNAs. The disulfidptosis-related genes were identified according to the previous research [20].

Construction and validation of the risk signature

The EC samples were assigned as training group and testing group at the ratio of 1 to 1. In training group, the univariate Cox regression analysis was applied to obtain disulfidptosis-related lncRNAs. Then, the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator regression analysis (LASSO), together with the multivariate Cox regression analysis were applied to acquire the disulfidptosis-related lncRNAs for risk signature establishment. The calculating formula was as follow:

\({\rm{Risk\; score}}=\sum \left[{\rm{Exp}}({\rm{lncRNA}})\times {\rm{coef}}({\rm{lncRNA}})\right]\)

The Exp (lncRNA) refers to the expression of above-mentioned lncRNAs. The coef (lncRNA) refers to the regression coefficient of disulfidptosis-related lncRNAs. The “survmine” and “survival” packages were applied to verify the risk signature using receiver operating characteristic curves (ROC) and the area under the time-dependent ROC curves (AUCs).

Principal component analysis (PCA)

PCA, plotted by the “Scatterplot3d” package, was used to observe the group ability of predictive models or other clinicopathological indicators.

Tissue Microarray and clinical samples

EC patients tissue samples and their clinical information were obtained from Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine according to the approval of Ethical Review Board. All patients did not receive chemo- or radiotherapy before surgery. The written informed consents were obtained from patients under the approval of Ethical Review Board.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and in site hybridization (ISH) staining

IHC was performed as previously described [21].The antibody applied in the research were as Mouse-anti-c-MYC(1:50, Proteintech, Cat#67447-1-Ig), Rabbit-anti-GLUT1(1:50, Proteintech, Cat#21829-1-AP). The EMSLR-specific probe was synthesized by Servicebio (Wuhan, China). The IHC and ISH quantification were completed by two pathologists in a blinded manner. The staining intensity was classified as 0 = negative, 1 = weak, 2=moderate, 3=positive.

Cell culture and transfection

The ISHIKAWA and HEC-1-A endometrial cancer cell lines were obtained from Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital and Ruijin Hospital. The cell lines were authenticated by short tandem repeat (STR) profiling and were tested for mycoplasma contamination. Cells were maintained in the Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, GIBCO) added with fetal bovine serum (FBS, 10%) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S). Cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The reagents used in the study were as: 2.85 mM β-mercaptoethanol (2ME) (Macklin, CAT#M6230), 1 µM BAY-876 (MCE, CAT#HY-100017) according to the manufacturer’s guideline.

The siRNA targeting against EMSLR were purchased from Gene Pharma (Shanghai, China). siEMSLR-1: 5-CCUCUGACGGGAACCGAAGTT-3, siEMSLR-2: 5- CAGCAAUUCUGGAUAUGGUTT-3. EMSLR overexpression was achieved using plenti-CMV-MCS-PGK-Puro synthesized by YiXueSheng Biosciences Inc (Shanghai, China). Stable cell line was maintained in the complete medium with 5 μg/mL of puromycin. Cell transfection was performed as previously described [22].

Cell functional assays and 5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation assay

CCK-8 cell viability assay was performed using Cell Counting Kit-8 (KTA1020, Abbkine, China). The treated cells were seeded in the 96 well plate at the density of 2000/well. Cell viability was measured by microplate reader (M1000 PRO, TECAN) under the absorbance wavelength of 450 nm. The experiments were done in triplicates. The cell colony formation assay was performed as previously mentioned [23]. EdU staining assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s guideline using EdU assay detection kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). 3х104 cells were plated in each well of the 8-well chamber (ibidi, Germany, Cat#80826). After staining, the sample was imaged by Zeiss LSM 510 (Zeiss, Germany). All assays were performed in triplicate and the results were obtained in three independent experiments.

Xenograft assays

5-week-old BALB/C nude female mice were kept in the Specific Pathogen Free (SPF) Laboratory Animal Center according to the NIH guidelines. Briefly, 2 × 106 of HEC-1-A cells which stably express shNC/shEMSLR were injected subcutaneously at the posterior axillary line of each mouse (randomized into 2 groups, n = 5). Tumor size was measured using vernier calipers every week (volume=long diameter × short diameter × short diameter × 1/2). Mice were sacrificed one month after the injection. Tumors were weighted and prepared for the following analysis.

Western blotting (WB) and quantitative real time PCR (qPCR)

Proteins were isolated from cells by using RIPA Lysis Buffer (Servicebio, Wuhan, China), and the protein concentrations were quantified by Enhanced BCA Protein Assay Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Protein samples were added to the holes and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, followed by transferring onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. After blocking with 5% skim milk, the membranes were then probed with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight. After that, HRP-labeled secondary antibodies were added for 1 h treatment at 37 °C. Signals were detected by BeyoECL Plus (Beyotime) and quantified using ImageLab software. β-actin was served as the endogenous control. The antibody were as mouse-anti-β-actin (1:3000, Servicebio, Cat#GB12001), Mouse-anti-c-MYC(1:50, Proteintech, Cat#67447-1-Ig), Rabbit-anti-GLUT1(1:50, Proteintech, Cat#21829-1-AP), Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) HRP (1:5000, AB0101, Abways), Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) HRP (1:5000, AB0102, Abways).

Total RNA was extracted by SteadyPure Quick RNA Extraction Kit (ACCURATE BIOLOGY, China). RNA reverse transcription was completed using Evo M-MLV RT Mix Kit (ACCURATE BIOLOGY, China). SYBR green Premix Pro taq HS qPCR Kit (ACCURATE BIOLOGY, China),10µl system (4.2 µl cDNA+5 µl SYBR green 2 × premix+0.4 µl primer forward+0.4 µl primer reverse) was applied to perform PCR at the recommended thermal setting in Viia7 Thermo Scientific. The primer sequences were as: EMSLR (human) forward GCACGCACCTCTCCTCTGAC, reverse GTGGCTTCTCGGCTGAATCCC; 18S forward GGCCCTGTAATTGGAATGAGTC, reverse CCAAGATCCAACTACGAGCTT. Triplicate reactions were performed for each sample. The quantitative mRNA expressions were normalized to 18S and determined by 2−ΔΔCt method.

F-actin staining

3 × 104 cells were seeded in each well. Once attached to the plate, cells were fixed by paraformaldehyde for 15 min. 0.4% Triton X-100 was applied for permeabilization. 5 min after, 594-phalloidin (ShareBio, Cat. No. SB-YP0052) was utilized at the diluting ratio of 1:200 for 20 min at room temperature, followed by 10 min of DAPI staining. Cells were imaged by Zeiss LSM 510 (Zeiss, Germany).

Cell death staining

Cells were seeded in the 12 well plate at appropriate density and cultivated in glucose present/deprivation medium (DMEM no-glucose, GIBCO) or treated with required drugs. Dead cells were stained with PI (ShareBio, Cat. No. SB-Y6002) and detected by flow cytometry (LSRFortessa, Becton Dickinson). All data were analyzed by FlowJo V1.

Glucose consumption assay and NADP+/NADPH measurement

The glucose consumption assay was performed using Glucose kit (glucose oxidase method) (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute CAT#A154-1-1) following the manufacturer’s instruction. The value was measured by microplate reader under the absorbance wavelength of 505 nm. NADP+/NADPH Assay Kit with WST-8 (S0179, Beyotime, China) was applied to detect the relative value of NADP+/NADPH. All samples were detected measured by microplate reader (M1000 PRO, TECAN) under the absorbance wavelength of 450 nm.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 25BK.0) was used for statistical analysis. Graphs generation was completed by GraphPad Prism 8 (San Diego, USA). All data was represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) in histogram. Significance was calculated by Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA. Correlation analysis was performed by Pearson’s correlation analysis. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

Results

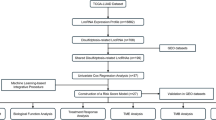

Identification of disulfidptosis-related lncRNAs, construction and validation of dislufidptosis-related lncRNAs risk signature

The expression profiles with clinical and pathological information were downloaded from TCGA database. The disulfidptosis-related genes were obtained from the published research. Initially, 1405 disulfidptosis-related lncRNAs associated with (|Pearson R| > 0.35, and p < 0.001) were identified through Pearson correlation analysis (Fig. 1B). A total of 472 endometrial cancer samples were randomly divided into training group (236 samples) and testing group (236 samples) (Fig. 1A). In training group, 80 prognosis-associated lncRNAs were identified via univariate COX regression analysis. Subsequently, through LASSO regression analysis and multivariate COX regression analysis, 12 genes related to disulfidptosis were selected to construct a disulfidptosis-related risk signature (Fig. 1C–E). Among these genes, 6 genes are protective factors (AL359220.1, NRAV, AL161421.1, AC020765.2, AC083855.2, AC004596.1) and the other six are detrimental factors (AP003059.1, AC103563.9, EMSLR, AL356481.2, AC010761.1, LINC01719). The calculation formula for the risk scores of the risk signature is as follow: risk score =0.8904×Exp (AP003059.1)+ -0.7578×Exp (AL359220.1) + 1.0380×Exp (AC103563.9) + 0.4320×Exp (EMSLR) + 1.3204×Exp (AL356481.2) + 0.5031×Exp (AC010761.1) + 0.8328×Exp (LINC01719) +-0.7031×Exp (NRAV) +-0.3444×Exp (AL161421.1) +-0.9563×Exp (AC020765.2) +-0.7123×Exp (AC083855.2) +-0.7063×Exp (AC004596.1). Based on the median of risk scores, 472 endometrial cancer samples were divided into high-risk and low-risk groups.

A Flowchart of establishing disulfidptosis risk model. B Sankey diagram of disulfidptosis-related genes and disulfidptosis-related lncRNAs. C Cross-validation plot for the penalty term. D LASSO expression coefficient plot of disulfidptosis-related lncRNAs. E Correlation heatmap of disulfidptosis-related lncRNAs and disulfidptosis-related genes. F Risk heatmap of the training group. G Distribution plot of risk scores in the training group. H Scatter plot of survival status in the training group. I, J Kaplan–Meier (KM) analysis for overall survival and progression-free survival in the training group based on the TCGA database. K ROC curve predicting the overall survival in training group. L–O PCA plot of all genes, of disulfidptosis-related genes, of disulfidptosis-related lncRNAs and of risk signature.

As was shown, the heatmap depicted the expression level of 12 disulfidptosis-related lncRNAs (Fig. 1F). The risk signature presented a good predictive ability for the prognosis of EC patients as the risk scores calculated based on the risk signature are negatively correlated with the prognosis of EC patients (Fig. 1G). With the augmentation of risk scores, the number of deceased patients also increased (Fig. 1H). Moreover, patients in the high-risk group had a worse prognosis compared to those in the low-risk group (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1I, J). In addition, the areas under the ROC curves (AUCs) also indicated that the risk signature had good accuracy in predicting the prognosis of EC patients (0.740 at 1-year, 0.852 at 2-year, 0.864 at 3-year) (Fig. 1K). Ultimately, the risk signature was found to be an independent risk factor affecting the prognosis of EC patients through univariate and multivariate COX regression analyses in examining the influencing factors of EC.

To validate the accuracy of the risk signature in predicting patient prognosis, we included it in both testing group and entire group for examination. The heatmap showed the expression levels of 12 disulfidptosis-related lncRNAs in each sample of testing group and entire group (Supplementary Fig. 1A). In both testing group and entire group, risk scores are positively correlated with the number of deaths among UCEC patients, while patients in the high-risk group have a worse prognosis (Supplementary Fig. 1B–D). In addition, the AUCs have also indicated that the risk signature had good predictive ability in both testing group and entire group (Supplementary Fig. 1E). Through univariate and multivariate COX regression analyses of two groups, the risk signature was identified as an independent risk factor affecting the prognosis of EC patients. In summary, the risk signature demonstrates accurate predictive ability for the prognosis of EC patients in both the testing group and the entire group, yielding results similar to those in the training group.

After verifying the predictive ability of the risk signature, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed to assess the grouping capability of the risk signature. The image displayed the PCA plots based on whole-genome expression profiles, 10 disulfidptosis-related genes, 12 disulfidptosis-related lncRNAs, and the risk signature (Fig. 1L–O). It is evident that the risk signature effectively separates the samples into two distinct groups.

The expression of EMSLR is upregulated in endometrial cancer and correlates with poor prognosis

To validate that the disulfidptosis occurs in high-SLC7A11-expressed tumor, we detected the expression of SLC7A11 in different types of cancer. It was found that compared with other cancer type, endometrial cancer samples performed higher SLC7A11, which was in accordance with our expectation (Fig 2A). Next, we applied the online server GEPIA to further determine the important role of EMSLR in endometrial cancer. It was found that EMSLR highly expressed in endometrial cancer tissue compared to normal tissue and correlated with poorer prognosis (Fig. 2B, C). The IHC staining results have also verified the above-mentioned findings (Fig. 2E). In addition to that, the expression of EMSLR in endometrial cancer increased along with the pathological grade of tumor, suggesting its important role in the progression of EC. We have also analyzed the correlation of EMSLR expression and immune characteristics. As a result, higher EMSLR expression was observed in microsatellite instability-low (MSI-L) or microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) tumors rather than microsatellite-stable (MSS) tumors, which is related to better prognosis (Fig. 2D). This finding also provided us a new approach in EC patients personal treatment. To conclude, EMSLR highly expresses in endometrial samples and relates to a poorer prognosis of EC patients.

A IHC staining of SLC7A11 in pan-cancer tissue samples. B Expression profile of EMSLR in TCGA datasets. C Kaplan–Meier analysis of overall survival and disease-free survival in patients with high or low EMSLR expression on GEPIA. D Representative images and histogram of EMSLR IHC staining in endometrial cancer tissue with MSS, MSI-L and MSI-H. Scale bar = 50 µm. E Representative images of EMSLR IHC staining in different grade of endometrial cancer or para-tumor tissue with its analysis. Scale bar = 50 µm. ***P < 0.001.

EMSLR promotes cell proliferation of endometrial cancer in vitro and in vivo

To further investigate the role of EMSLR in the development of endometrial cancer, we first knockdown or overexpressed the expression of EMSLR in HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cells (Fig. 3A). As a result, the CCK-8 cell viability assay, cell colony formation assay and EdU assay have significantly suggested that the knockdown of EMSLR impeded the proliferation of endometrial cancer cells while EMSLR overexpression showed the opposite results (Fig. 3B–E). These findings have initially confirmed the important role of EMSLR during the development of endometrial cancer. In addition, we have also injected the shNC/shEMSLR HEC-1-A cells subcutaneously in the BALB/C nude female mice. As was expected, it was found that EMSLR also promoted tumor growth in vivo in terms of tumor size and weight. In conclusion, EMSLR promotes endometrial cancer cell proliferation both in vitro and in vivo, indicating its importance in the progression of endometrial carcinoma.

A Knockdown and overexpression efficiency of EMSLR validated by qPCR. B CCK-8 analysis in EMSLR knockdown or overexpressed HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cells with its statistical analysis. C, D Representative image of cell colony formation assay of EMSLR knockdown or overexpressed HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cells with its statistical analysis. E Representative image of EdU staining of EMSLR knockdown HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cells with its statistical analysis. Scale bar = 100 µm. F Image of injected shNC/shEMSLR HEC-1-A cells formed tumors. Scale bar = 1 cm. G, H Tumor growth curve of xenograft assay and histogram of tumor weight with its analysis. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

EMSLR involves in disulfidptosis triggered by glucose deprivation in EC

To investigate whether EMSLR is involved in the disulfidptosis of endometrial cancer, cells with EMSLR knockdown or overexpression cell line were subjected to F-actin staining and cell death staining. As a result, cell skeleton presented no difference under the circumstance of glucose complete medium (Fig. 4A). However, EMSLR knockdown significantly increased cell shrinkage compared to control group in glucose-deprived medium. On the contrary, EMSLR overexpression could resist the morphological alteration of the cytoskeleton to a large extent under this situation. Consistent with the findings in cytoskeleton, EMSLR downregulation augmented cell death in glucose starving medium while the overexpression of EMSLR decreased the death rate (Fig. 4B, Supplementary Fig. 3A). Then, we applied disulfidptosis inhibitor 2ME, a strong reducing agent, in the glucose-deprived medium. It was found that 2ME could rescue cell death when glucose was deprived.

A F-actin staining of siNC/siEMSLR, VECTOR/EMSLR HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cells maintained in glucose complete or free medium for 4 h. Scale bar =100 µm. B Cell dead staining of siNC/siEMSLR HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cells in glucose complete, glucose free, glucose free with 2.85 mM 2ME medium for 12 h with statistical analysis. C GSEA used a KEGG gene set of EMSLR in TCGA database. D Correlation analysis between EMSLR with G6PD, PGD, RPE, TKT and RPIA using GEPIA. E Glucose consumption assay of siNC/siEMSLR HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cells. F NADP+/NADPH detecting assay of siNC/siEMSLR HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cells in glucose complete and glucose free medium. N.S: not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

The occurrence of disulfidptosis was greatly due to the inadequate supply of NADPH, which was generated from glucose through the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) [24]. Next, we conducted the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of lncRNA EMSLR in the TCGA database. Intriguingly, EMSLR was found to be significantly correlated with the PPP pathway. Moreover, it was also strongly associated with pathway enzyme G6PD, PGD, RPE, TKT and RPIA at the transcriptional level using Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) online server (Fig. 4C, D) [25]. To confirm this, we first detected glucose consumption in EMSLR knockdown/overexpressed endometrial cells. As was expected, EMSLR significantly regulated glucose consumption while knockdown decreased the uptake level and vice versa (Fig. 4E, Supplementary Fig. 3B). To further explore the role of EMSLR in EC disulfidptosis, we detected the NADP+/NADPH ratio of endometrial cancer cells. The down-expression of EMSLR enhanced the NADP+/NADPH ratio significantly while forced expression of EMSLR reduced the value under the condition where glucose was restricted (Fig. 4F, Supplementary Fig. 3C). In conclusion, EMSLR is involved in disulfidptosis in endometrial cancer which is triggered by glucose deprivation.

EMSLR regulated EC cell disulfidptosis and proliferation through GLUT1

As was previously reported, the inhibition of glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) led to the disulfidptosis of cancer cells [26]. As a transporter for glucose, GLUT1 highly expressed in many cancer types including endometrial carcinoma, playing an important role in the tumorigenesis. In this study, we utilized GLUT1 inhibitor BAY876 to explore whether EMSLR influenced GLUT1 to modulate cancer progression and cell disulfidptosis of EC. Firstly, we verified the association between GLUT1 and EMSLR through correlation analysis and immunoblotting (Fig. 5A, B). Through cell colony formation assay and EdU staining, it was found that the application of BAY876 significantly impeded endometrial cancer cell viability. Interestingly, the overexpression of EMSLR restored the inhibitive effect (Fig. 5C–F). These results suggested that EMSLR promoted endometrial cancer cell proliferation via regulating GLUT1. Subsequently, to further investigate whether EMSLR modulated EC disulfidptosis through GLUT1, F-actin staining and cell death staining were performed. In accordance with the findings above, cell morphology and death rate presented no difference in glucose-abundant condition (Supplementary Fig. 4B). However, GLUT1 inhibitor induced cell shrinkage and cell death when glucose was deprived, while the forced expression of EMSLR reversed the detrimental impact (Fig. 6A, B). In summary, EMSLR is involved in EC cell disulfidptosis and growth via regulating GLUT1.

A Correlation analysis of EMSLR with GLUT1 via GEPIA. B Western blotting of GLUT1 in EMSLR knockdown or overexpressed HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cells. C, D Representative images of EdU staining of VECTOR/EMSLR HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cells treated with DMSO or BAY876 and its statistical analysis. Scale bar = 100 µm. E, F Representative images of cell colony formation assay of VECTOR/EMSLR HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cells treated with DMSO or BAY876 and its statistical analysis. Scale bar = 1 cm. N.S: not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

A F-actin staining of VECTOR/EMSLR HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cells treated with DMSO or BAY876 maintained in glucose-free medium for 4 h. Scale bar = 50 µm. B Cell death staining of VECTOR/EMSLR HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cells treated with DMSO or BAY876 in glucose complete/free/glucose free with 2.85 mM 2ME medium for 12 h and its statistical analysis. N.S: not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

EMSLR involves in EC cell progression via c-MYC-GLUT1 pathway

To further investigate how EMSLR modulate GLUT1 in the development of EC, we explored the potential mechanism by GSEA analysis. Surprisingly, we found that EMSLR was significantly associated with c-MYC pathway (Fig. 7A). Moreover, the correlation analysis indicated that the expression of c-MYC strongly correlated with EMSLR (Fig. 7B). It was well known that the transcription factor c-MYC upregulated glycolytic gene GLUT1 in glucose metabolism [27]. To verify the conjecture that EMSLR enhance c-MYC—GLUT1 pathway to promote EC, we first detected the expression of c-MYC in EMSLR knockdown or expression EC cells. In the expectation with our hypothesis, we observed a positive correlation of EMSLR and c-MYC by western blotting (Fig. 7C). Then, the CCK-8 assay and cell colony formation assay have shown that the overexpression of c-MYC could abrogate the inhibitive effect brought by EMSLR knockdown, indicating that EMSLR modulated EC cell proliferation through regulation of c-MYC (Fig. 7D–F). Subsequently, we performed F-actin staining and cell death staining to detect the influence in EC disulfidptosis. As a result, c-MYC overexpression restored the cell death rate and cytoskeleton alteration caused by EMSLR knockdown compared to the control group in glucose-limited situation (Fig. 7G–I). In accordance with the above-mentioned results, no significance was observed in glucose-abundant circumstance (Supplymentary Fig. 4A). However, the addition of 2-ME partially decreased the cell death in glucose-deprivation condition. In addition, IHC and IF staining on EC tissue from patients have verified the positive correlation of EMSLR expression with c-MYC and GLUT1(Fig. 8A). Intriguingly, we have noticed the nuclear translocation of c-MYC in EMSLR overexpressed ISHIKAWA cells, which suggested that EMSLR regulated c-MYC from many aspects (Fig. 8B). These results strongly support the hypothesis that EMSLR regulates EC cell proliferation and disulfidptosis via c-MYC-GLUT1 pathway.

A GSEA used a HALLMARK gene set of EMSLR in TCGA database. B Correlation analysis between EMSLR with MYC using GEPIA. C Western blotting of c-MYC in EMSLR knockdown or overexpression HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cell lines. D CCK-8 assay of siNC/siEMSLR with VECTOR/ c-MYC HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cells with its analysis. E, F Cell colony formation assay using siNC/siEMSLR with VECTOR/ c-MYC HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cells and Statistical analysis. G F-actin staining of siNC/siEMSLR with VECTOR/ c-MYC HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cells maintained in glucose free medium for 4 h. Scale bar =50 µm. H, I Cell death staining of siNC/siEMSLR with VECTOR/c-MYC HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cells in glucose complete/free/glucose free with 2.85 mM 2ME medium for 12 h and its statistical analysis. N.S: not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

A Representative images of IHC and ISH staining of c-MYC, GLUT1 and EMSLR in EC patients. Scare bar = 50 µm. B IF staining of c-MYC in EMSLR knockdown and overexpression HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cells. Scare bar = 50 µm. C Mechanical illustration of EMSLR regulating c-MYC-GLUT1 pathway in cervical cancer cell disulfidptosis and progression.

Plus, the sensitivity of EC cells to paclitaxel is influenced by the expression of the lncRNA EMSLR. Paclitaxel is the first choice for EC chemotherapy. Through CCK-8 cell viability assay, as EMSLR knocked down, paclitaxel IC50 of both HEC-1-A and ISHIKAWA cells decreased. And EMSLR overexpression showed higher paclitaxel IC50 (Supplementary Fig. 5C).

Discussion

The incident of EC is rapidly increasing. Although early diagnosed endometrial cancer with surgical treatment carries a good prognosis, it is still a challenge for high-grade, recurrent or metastatic EC and other non-endometrioid histologies [28]. Hence, it is vital to explore potential molecular therapeutic targets. Multiple types of RCD were found to correlate with cancer drug sensitivity [29]. Disulfidptosis is a newly discovered modality of cell death. Its mechanism is different from apoptosis and ferroptosis, which cannot be inhibited by conventional cell death inhibitors. There is no doubt that in-depth exploration of disulfidptosis in endometrial cancer and targeting potential molecular targets is of great significance for the screening and treatment of EC.

In this study, we performed bioinformatics analysis to establish a risk signature based on 12 disulfidptosis-related lncRNAs in predicting the prognosis of EC patients. Through the analysis of the GEPIA database and EC patients from our hospital, we found that EMSLR was highly expressed in EC tissue compared to normal tissue and correlated with poor prognosis. EMSLR has been identified as a disulfidptosis-related lncRNA in many other cancers. We have verified that EMSLR promoted EC cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo. In addition, we found that high expression of EMSLR promoted paclitaxel resistance of EC cells. More importantly, EMSLR was found to impede disulfidptosis of endometrial cancer cells under the condition where glucose was deprived. EMSLR is an important molecule in endometrial cancer progression. Targeting EMSLR with genetic tools, such as siRNA, shRNA and CRISPR/Cas9, in conjunction with chemotherapy, has the potential to improve outcomes in patients with advanced poor prognosis/recurrent endometrial cancer. However, its exact mechanism in endometrial cancer is not clear yet.

GLUT1 plays an important role in the progression of endometrial cancer. Importantly, a previous study has confirmed that inhibition of GLUT1 can lead to enhancement of NADP+/NADPH ratio and ultimately render disulfidptosis. In our research, we have verified the role of EMSLR in regulating UCEC progression and disulfidptosis was dependent on GLUT1. c-MYC is an important glycolysis-related transcription factor. Many studies have confirmed the core role of c-MYC in the regulation of GLUT1. In this study, through TCGA-based GSEA analysis, we found that EMSLR was closely related to the c-MYC pathway. According to our findings, it was showed that EMSLR was positively correlated with c-MYC expression in endometrial cancer. The subsequent functional assays confirmed that EMSLR relied on the c-myc-GLUT1 pathway to regulate EC progression and disulfidptosis. In addition to that, we have also found that EMSLR might induce c-MYC nuclear translocation. We hypothesized that EMSLR regulated the expression of c-MYC in the nucleus via binding to it and, in the meantime, locked c-MYC in the nucleus. However, the underlying mechanism remains to be unveiled and further exploration is required.

In conclusion, we constructed a risk signature that could predict the prognosis of EC patients. EMSLR was highly expressed in EC and associated with poor prognosis. EMSLR plays a regulatory role in EC progression and disulfidptosis through c-MYC-GLUT1 pathway. This study was the first to confirm the inhibitory effect of EMSLR on endometrial disulfidptosis and elucidate the potential mechanism.

Data availability

All data and materials supporting the results and analysis in the article are included within the article and its additional files. TCGA database (https://cancergenome.nih.gov/), GEPIA (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/).

References

Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:12–49.

Gordhandas S, Zammarrelli WA, Rios-Doria EV, Green AK, Makker V. Current evidence-based systemic therapy for advanced and recurrent endometrial cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21:217–26.

Brooks RA, Fleming GF, Lastra RR, Lee NK, Moroney JW, Son CH, et al. Current recommendations and recent progress in endometrial cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:258–79.

Newton K, Strasser A, Kayagaki N, Dixit VM. Cell death. Cell. 2024;187:235–56.

Liu X, Zhuang L, Gan B. Disulfidptosis: disulfide stress-induced cell death. Trends Cell Biol. 2024;34:327–37.

Moloney JN, Cotter TG. ROS signalling in the biology of cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2018;80:50–64.

Zheng P, Zhou C, Ding Y, Duan S. Disulfidptosis: a new target for metabolic cancer therapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2023;42:103.

Xie J, Deng X, Xie Y, Zhu H, Liu P, Deng W, et al. Multi-omics analysis of disulfidptosis regulators and therapeutic potential reveals glycogen synthase 1 as a disulfidptosis triggering target for triple-negative breast cancer. MedComm (2020). 2024;5:e502.

Zhao D, Meng Y, Dian Y, Zhou Q, Sun Y, Le J, et al. Molecular landmarks of tumor disulfidptosis across cancer types to promote disulfidptosis-target therapy. Redox Biol. 2023;68:102966.

Kopp F, Mendell JT. Functional Classification and Experimental Dissection of Long Noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2018;172:393–407.

Tan YT, Lin JF, Li T, Li JJ, Xu RH, Ju HQ. LncRNA-mediated posttranslational modifications and reprogramming of energy metabolism in cancer. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2021;41:109–20.

Bhan A, Soleimani M, Mandal SS. Long noncoding RNA and cancer: a new paradigm. Cancer Res. 2017;77:3965–81.

Wang J, Lei C, Shi P, Teng H, Lu L, Guo H, et al. LncRNA DCST1-AS1 promotes endometrial cancer progression by modulating the MiR-665/HOXB5 and MiR-873-5p/CADM1 pathways. Front Oncol. 2021;11:714652.

Bieńkiewicz J, Romanowicz H, Szymańska B, Domańska-Senderowska D, Wilczyński M, Stepowicz A, et al. Analysis of lncRNA sequences: FAM3D-AS1, LINC01230, LINC01315 and LINC01468 in endometrial cancer. BMC Cancer. 2022;22:343.

Hegre SA, Samdal H, Klima A, Stovner EB, Nørsett KG, Liabakk NB, et al. Joint changes in RNA, RNA polymerase II, and promoter activity through the cell cycle identify non-coding RNAs involved in proliferation. Sci Rep. 2021;11:18952.

Zhang M, Zhang F, Wang J, Liang Q, Zhou W, Liu J. Comprehensive characterization of stemness-related lncRNAs in triple-negative breast cancer identified a novel prognostic signature related to treatment outcomes, immune landscape analysis and therapeutic guidance: a silico analysis with in vivo experiments. J Transl Med. 2024;22:423.

Priyanka P, Sharma M, Das S, Saxena S. E2F1-induced lncRNA, EMSLR regulates lncRNA LncPRESS1. Sci Rep. 2022;12:2548.

Zhang L, Wang S, Wang L. Construction of lncRNA prognostic model related to disulfidptosis in lung adenocarcinoma. Heliyon. 2024;10:e35657.

Nie X, Ge H, Wu K, Liu R, He C. Unlocking the potential of disulfidptosis-related LncRNAs in lung adenocarcinoma: a promising prognostic LncRNA Model for survival and immunotherapy prediction. Cancer Med. 2024;13:e70337.

Shi S, Tang X, Liu H. Disulfidptosis-related lncRNA for the Establishment of novel prognostic signature and therapeutic response prediction to endometrial cancer. Reprod Sci. 2024;31:811–22.

Sun Y, Peng Q, Wang R, Yin Y, Mutailifu M, Hu L, et al. Elevated expression of Golgi Transport 1B promotes the progression of cervical cancer by activating NF-κB signaling pathway via interaction with TBK1. Carcinogenesis. 2024;46:bgae054.

Yin YF, Jia QY, Yao HF, Zhu YH, Zheng JH, Duan ZH, et al. OCIAD2 promotes pancreatic cancer progression through the AKT signaling pathway. Gene. 2024;927:148735.

Wang YY, Zhou YQ, Xie JX, Zhang X, Wang SC, Li Q, et al. MAOA suppresses the growth of gastric cancer by interacting with NDRG1 and regulating the Warburg effect through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2023;46:1429–44.

Chen L, Zhang Z, Hoshino A, Zheng HD, Morley M, Arany Z, et al. NADPH production by the oxidative pentose-phosphate pathway supports folate metabolism. Nat Metab. 2019;1:404–15.

Tang Z, Li C, Kang B, Gao G, Li C, Zhang Z. GEPIA: a web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W98–w102.

Liu X, Nie L, Zhang Y, Yan Y, Wang C, Colic M, et al. Actin cytoskeleton vulnerability to disulfide stress mediates disulfidptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2023;25:404–14.

Dang CV, Le A, Gao P. MYC-induced cancer cell energy metabolism and therapeutic opportunities. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6479–83.

Urick ME, Bell DW. Clinical actionability of molecular targets in endometrial cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19:510–21.

Zou Y, Yang A, Chen B, Deng X, Xie J, Dai D, et al. crVDAC3 alleviates ferroptosis by impeding HSPB1 ubiquitination and confers trastuzumab deruxtecan resistance in HER2-low breast cancer. Drug Resist Updat. 2024;77:101126.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (ID 82172934, to Y.C. Teng; ID 82372675, to Y.C.Teng, ID 82102707, to Y. Zhou).This work was also supported by Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital (ynqn202521) to Y.X.SUN.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XLZ and YFY contributed to the study's conceptualization and design of the project. YXS, RWW, and XZL contributed to the bioinformatic analysis, methodology and original draft of the manuscript. WZZ and XHH contributed to analyzing data. YZ contributed to the collection of clinical and pathological data, YCT supervised the study and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Authors declare no financial or non-financial interests that are directly or indirectly related to the work submitted for publication.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (No.2023-YS-020 for nude mice, No.2023-0048 for human). All participants provided written informed consent. We have also obtained written informed consent from human research participants for publication of the images.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, Y., Wang, R., Li, X. et al. The involvement of lncRNA EMSLR in the disulfidptosis and progression of endometrial carcinoma. Cancer Gene Ther 32, 1107–1119 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41417-025-00918-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41417-025-00918-4

This article is cited by

-

Disulfidptosis in cancer: from redox stress to therapeutic strategy

Cancer Gene Therapy (2025)