Abstract

N6-methyladenosine (m6A), a pivotal RNA modification, has garnered considerable attention in cell biology and disease research. m6A plays a critical role in the regulation of gene expression, cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis, with particular relevance to the onset and progression of ocular diseases. This review examines the current research on m6A in ocular diseases, including keratitis, cataracts, glaucoma, retinopathy, thyroid ophthalmopathy, and ocular tumors, highlighting its functional significance and potential mechanisms in these conditions. Recent studies suggest that m6A modification influences cellular fate and pathophysiological processes by modulating the expression of key genes. However, a deeper understanding of the precise mechanisms underlying m6A action in ocular diseases is still needed. By synthesizing the existing literature, this review seeks to offer novel insights and identify potential therapeutic targets, thereby advancing clinical applications for ocular disease treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Facts

-

1.

The molecular mechanisms by which m6A modification regulates ocular diseases remain to be fully elucidated. While current research has revealed that m6A modification influences cellular fate and pathophysiological processes through modulating the expression of key genes, the specific regulatory mechanisms of m6A modification in different types of ocular diseases require further exploration. Clarifying these mechanisms will provide a more solid theoretical foundation for the treatment of ocular diseases.

-

2.

The dynamic regulatory mechanisms of m6A modification in ocular diseases remain unclear. m6A modification is a dynamic and reversible process influenced by various factors such as environmental conditions and disease progression. However, the dynamic changes in m6A modification during the onset and progression of ocular diseases, as well as their regulatory mechanisms, are still poorly understood. Future research should focus on investigating the dynamic regulatory patterns of m6A modification in ocular diseases and the mechanisms of interaction between m6A modification and other signaling pathways.

-

3.

The potential of m6A modification as a therapeutic target for ocular diseases requires validation. Current research has identified some key m6A regulatory proteins and related signaling pathways involved in ocular diseases, but the safety and efficacy of therapies targeting m6A modification need to be further evaluated. In-depth studies on the therapeutic potential of m6A modification will help develop novel therapeutic strategies for ocular diseases and advance their clinical applications.

-

4.

The interplay between m6A modification and other epigenetic modifications in ocular diseases is worth exploring. Epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation and histone modification play significant roles in the regulation of ocular diseases. The relationship between m6A modification and other epigenetic modifications and their combined effects in ocular diseases remains largely unknown. Future research should investigate the synergistic or antagonistic effects of m6A modification with other epigenetic modifications to uncover their complex regulatory networks in ocular disease pathogenesis.

Introduction

Epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation, RNA modification, histone modification, and chromatin remodeling, regulate gene expression through chemical or structural alterations without changing the underlying DNA sequence [1]. Among these, RNA methylation—an essential and reversible form of RNA modification—has garnered considerable attention due to its pivotal role in post-transcriptional regulation [2]. Notably, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification, the most prevalent base methylation in mRNA, has attracted significant interest in light of studies on m6A content expression, the distribution of its modifiers in human tissues, and its involvement in cellular functions, as well as its potential as a biomarker [3, 4]. Under physiological conditions, m6A modification regulates gene expression, cell differentiation, and tissue homeostasis, ensuring normal cellular function and development. In pathological contexts, dysregulation of m6A modification is closely associated with the onset and progression of various diseases, affecting processes such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, inflammatory responses, and cell-cell interactions, thereby driving disease progression [5, 6].

The eye is a precise optical organ composed of structures such as the cornea, lens, and retina that are responsible for focusing light and converting it into neural signals to transmit to the brain (Fig. 1). Eye diseases represent a leading cause of visual impairment and blindness, with their pathogenesis intricately linked to epigenetic modifications [7]. Recent studies have highlighted the association between DNA and RNA methylation and the pathological processes of several common ocular diseases [8, 9]. In particular, m6A modification exhibits significant alterations in the cornea, retina, and choroid under pathological conditions, offering new insights into the pathophysiological mechanisms of ophthalmic diseases [10]. Given its importance, investigating RNA methylation in ocular diseases is essential, as it lays a crucial foundation for identifying potential gene therapy targets.

As an important part of the visual organ, the eye includes the cornea, lens, vitreous body, retina, optic nerve, etc. The cornea is composed of five different layers: the epithelial cell layer, Bowman’s layer, corneal stromal layer, Descemet’s membrane, and endothelial cell layer. Each layer is essential for the function of the cornea, not only as the first mechanical and immunological barrier of the eye, but also responsible for the transmission and convergence of external light to the retina to produce vision.

This paper aims to introduce the fundamental concepts, mechanisms, and detection methods of m6A modification. Furthermore, it investigates its regulatory role and potential therapeutic implications in various ocular diseases, including corneal diseases, cataracts, glaucoma, uveitis, retinopathy, Traumatic Optic Neuropathy (TON), thyroid eye disease (TED), myopia, and ocular tumors. Finally, the paper addresses future research directions and the challenges that must be overcome to deepen our understanding of m6A modification in ophthalmic diseases.

M6A modification

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification is one of the most prevalent RNA modifications in eukaryotes. It regulates gene expression by adding a methyl group to the nitrogen atom at the N6 position of adenosine in both mRNA and non-coding RNA. m6A is widespread across various organisms, including viruses, yeast, plants, insects, and mammals, occurring every 700–800 base pairs on average in polyadenylated RNA, and at lower frequencies in other types of RNA [11, 12]. In the human genome, over 12,000 m6A loci have been identified, primarily located in the coding regions and 3’ untranslated regions (3’ UTR) of approximately 7000 genes. The consensus sequence for these loci is RRACH (where R = G/A and H = A/C/U) [13, 14]. M6A modification is a dynamic and reversible process that plays a central role in post-transcriptional regulation, including RNA splicing, stability, trafficking, translation, and degradation. It influences various biological processes, such as cell differentiation, development, immune response, and neurological function [15, 16]. Furthermore, dysregulation of m6A modification is closely associated with the onset and progression of various diseases, including cancer, neurological disorders, metabolic diseases, and immune-related conditions [17, 18]. The dynamic regulation of m6A modification is controlled by three classes of enzymes: m6A methyltransferases (referred to as “writers”), demethylases (“erasers”), and m6A-binding proteins (“readers”), which are responsible for adding, removing, and recognizing the m6A modification, respectively (Table 1).

Writers

The m6A “writer” comprises an m6A methyltransferase complex (MTC), consisting of core members such as methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3), METTL14, and Wilms tumor 1-associated protein (WTAP), along with METTL16, zinc finger CCCH-containing type 13 (ZC3H13), RNA-binding methylprotein 15 (RBM15), and vir-m6A motif transferase-associated protein (VIRMA) [19]. METTL3 serves as the major catalytic subunit, transferring methyl groups from S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) to adenosine on RNA [20]. METTL14 enhances METTL3’s catalytic activity by stabilizing its conformation and facilitating RNA substrate recognition [21]. The METTL3/14 complex predominantly recognizes the GGACU consensus sequence. Although WTAP lacks intrinsic methyltransferase activity, it facilitates m6A deposition by interacting with the METTL3-METTL14 complex and plays a key regulatory role in RNA targeting and splicing [22]. VIRMA guides the METTL3/METTL14/WTAP complex to mediate region-specific mRNA methylation within the 3’ untranslated region (3’ UTR) and near the stop codon [23]. ZC3H13 ensures the nuclear localization of the MTC by bridging RBM15 to WTAP [24, 25].

Erasers

m6A modification on RNA can be reversed by demethylases, often referred to as “Erasers,” with Fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) and AlkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5) being the two primary RNA demethylases. FTO was the first identified m6A demethylase, achieving demethylation by oxidizing m6A to the intermediate N6-hydroxymethyladenosine (hm6A), which is further oxidized to N6-formyladenosine (f6A) and ultimately decomposes into adenosine (A) in aqueous solution [26, 27]. In contrast, ALKBH5, a nuclear protein that binds single-stranded nucleotides, catalyzes m6A demethylation by directly removing methyl groups from methylated adenosine in m6A, unlike FTO, which operates through an oxidative process [28]. Recently, a novel m6A demethylase, ALKBH3, has been identified and shown to be involved in tRNA demethylation [29]. FTO, ALKBH5, and ALKBH3 all belong to the alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase family, and their demethylation process utilizes 2-oxoglutarate (2OG) and Fe (II) as cofactors [29, 30].

Readers

The “reader” of m6A mainly consists of the YT521B homology (YTH) domain family (YTHDF1/2/3, YTHDC1/2), insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins (IGF2BP1/2/3), heterokaryotic nuclear factor RNA proteins (HNRNPC, HNRNPG, and HNRNPA2B1), and eukaryotic initiation factor 3 (eIF3).

The YTH domain is a conserved m6A-binding domain that selectively interacts with the m6A site in RNA. These molecules represent the most crucial “readers” of m6A modification [31]. As the first identified reader, the C-terminal YTH domain of YTHDF2 recognizes a specific m6A locus, while its N-terminal domain binds to the SH domain of the CCR4-NOT transcription complex subunit 1 (CNOT1), facilitating the recruitment of the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex. This interaction directs m6A-modified RNA to the processing body (P-body), promoting the deadenylation and degradation of its poly(A) tail, thereby enhancing RNA degradation [32, 33]. YTHDF1, specifically recognizing m6A-modified mRNAs through its YTH domain, interacts with the translation initiation factor eIF3 to direct these mRNAs into the translation initiation complex, thereby promoting translation initiation [34]. Additionally, the regulation of YTHDF1 depends on an eIF4G (eukaryotic initiation factor 4 G)-mediated loop structure, which enhances the efficiency of translation initiation for m6A-modified mRNAs, significantly boosting translation efficiency [35]. In contrast, YTHDF3 collaborates with the other two paralogues to regulate the translation and degradation of mRNA containing m6A in the cytoplasm [36].

YTHDC1 collaborates with nuclear RNA export factor 1 (NXF1) and the three-prime repair exonuclease (TREX) mRNA export complex, interacting with serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 3 (SRSF3) to facilitate mRNA nuclear export and regulate splicing [37, 38]. As a 3’/5’ RNA helicase, YTHDC2 promotes the degradation of m6A-modified mRNAs through its helicase activity. It also enhances mRNA stability by interacting with 5′–3′ exoribonuclease 1 (XRN1), thereby improving the translational efficiency of target mRNAs while simultaneously reducing their overall abundance [39, 40].

In RNA biology, m6A modification profoundly influences the secondary structure of RNA. HNRNPC and HNRNPG regulate mRNA abundance and its splicing process upon recognizing m6A, a mechanism referred to as the “m6A switch.” Additionally, HNRNPC and HNRNPG participate in the processing of precursor mRNAs, thereby affecting their stability, splicing, export, and translation [41, 42]. Moreover, HNRNPA2/B1 recognizes the m6A core motif RGAC and regulates selective RNA cleavage in a METTL3-dependent manner, thus promoting precursor miRNA processing. IGF2BPs recognize m6A-modified mRNAs and enhance mRNA stability and translation by recruiting RNA stabilizers in an m6A-dependent fashion (Fig. 2) [43, 44].

The molecular mechanisms of m6A modification involve dynamic interplay among three key groups of enzymes: the “writers,” “erasers,” and “readers.” These enzymes and associated factors work in concert to add, remove, and recognize m6A marks on RNA, thereby regulating various aspects of RNA metabolism. Specifically, m6A modifications influence critical RNA processes such as splicing, nuclear export, translation efficiency, and degradation, ultimately impacting gene expression and cellular function.

Techniques for identifying RNA m6A modifications

Studies on RNA modifications date back to the 1970s; however, it was not until 2012 that the combination of RNA immunoprecipitation with next-generation sequencing led to significant advances in m6A research [45]. Initially, identifying the m6A locus posed challenges due to technical limitations. The introduction of second-generation sequencing (seq) marked a milestone in m6A research, enabling substantial progress in the field [13].

MeRIP-seq (also known as m6A-seq) was the first widely used technique for transcriptome-wide mapping of m6A modifications. It employs anti-m6A antibodies to immunoprecipitate methylated mRNA fragments, which are then identified through high-throughput sequencing as enriched genomic regions known as “m6A peaks” [46]. The main advantages of this method include its relatively low RNA input requirement and a well-established experimental workflow, making it suitable for obtaining a broad, discovery-oriented overview of m6A modifications across the transcriptome. However, MeRIP-seq has several notable limitations. Its resolution is low—approximately 100–200 nt—which prevents the precise identification of methylated adenosines and yields only approximate modification regions [47]. More critically, the technique is highly dependent on the quality and specificity of the anti-m6A antibodies [48]. Issues such as non-specific binding to unrelated RNA structures or epitopes, as well as cross-reactivity, can lead to false-positive signals, while insufficient affinity for m6A in certain sequence contexts may result in false negatives. Furthermore, as an enrichment-based rather than an absolute quantitative approach, MeRIP-seq offers limited accuracy in comparing m6A dynamics across different samples.

To address the resolution limitations of MeRIP-seq, PA-m6A-seq was developed. This technique builds upon the MeRIP-seq protocol by incorporating a 4-thiouridine (4SU)-enhanced crosslinking step. A key advantage of PA-m6A-seq is its improved resolution—around 30 nt near the m6A site—enabling more precise mapping of modified regions [49]. The incorporation of 4SU introduces characteristic mutations at crosslinking sites during reverse transcription, providing a clearer molecular footprint of m6A locations. However, a major limitation of this method is its “blind-spot” nature: it can only detect m6A modifications situated near 4SU incorporation sites, thereby restricting its coverage and potentially missing functionally important m6A sites outside these regions. Moreover, like MeRIP-seq, PA-m6A-seq relies on anti-m6A antibodies for immunoprecipitation, meaning it remains susceptible to antibody-related artifacts such as non-specific binding and background bias [50].

The development of m6A individual-nucleotide-resolution crosslinking and immunoprecipitation (miCLIP) marked a major advance by enabling single-base resolution mapping of m6A sites [51]. In miCLIP, UV crosslinking covalently attaches antibodies to m6A-modified residues. During subsequent reverse transcription, the crosslinked antibody residues induce nucleotide misincorporation or truncation events in the cDNA, which are then detected by sequencing to pinpoint m6A sites with high precision. Despite this breakthrough, miCLIP still fundamentally depends on antibody recognition. Incomplete crosslinking efficiency can limit sensitivity, causing some authentic m6A sites to be missed. Additionally, the crosslinking process itself may introduce sequence-specific biases and lead to false-positive identifications. Consequently, even at single-base resolution, potential inaccuracies stemming from antibody specificity remain a concern, underscoring the need for careful data interpretation and validation using orthogonal experimental approaches.

M6A-REF-seq can quantitatively detect m6A loci at single-base resolution and accurately identify them across the entire transcriptome using the RNA endonuclease MazF and antibody-dependent methods [52]. In contrast, DART-seq eliminates the need for antibodies. It employs cytidine deaminase (APOBEC1) and YTH domain fusions to deaminate cytosines adjacent to uracil in m6A, detecting C-to-U editing events via RNA-seq and enabling high-resolution detection of m6A loci [53]. M6A-label-seq introduces N6-allyladenosine (a6A) at the m6A modification site using metabolic markers, which cyclizes to N1, N6-cyclic adenosine (cycA) through iodination. This method induces A-to-C/T/G mutations during reverse transcription, achieving single-base resolution detection at the m6A site [54]. The m6A-SEAL technology specifically labels the m6A site through FTO oxidation and a Dithiothreitol (DTT) chemical reaction, followed by biotin binding for enrichment. This approach enables highly sensitive detection of m6A modification sites across the transcriptome using high-throughput sequencing [55].

Building on m6A-seq, m6A-seq2 introduces multiplex sample mixing and barcode labeling technologies, which enhance experimental throughput and statistical power, improve the quantitative analysis of m6A modification, and enable efficient and accurate detection across multiple samples from a single sample [56]. MiCLIP2 significantly increases the accuracy and sensitivity of m6A detection by optimizing the experimental process and incorporating the machine learning model m6Aboost, while reducing the input material requirements [57]. M6A-LAIC-seq achieves single-nucleotide resolution detection of m6A-modified sites by photocrosslinking to immobilize m6A-modified RNA-protein complexes, followed by enrichment and sequencing using specific antibodies [50]. Techniques such as SELECT, MeRIP-qPCR, and MazF-qPCR are highly sensitive methods for detecting m6A, particularly suited for validation and quantitative analysis of m6A modifications at the single-gene level [52, 58]. SCARLET precisely localizes m6A modification sites through specific cleavage, radiolabeling, ligation-assisted extraction, and Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC) analysis, without requiring antibodies, making it versatile for various RNA types [59]. In addition, Mass Spectrometry (MS), Dot-blot, and Colorimetry are commonly employed to measure global m6A levels [60, 61] (Table 2).

M6A modification in the pathology of ocular disease

The study of m6A modification in ocular diseases is rapidly expanding, yet its precise role in specific ocular conditions remains poorly understood. M6A modification holds significant potential for ophthalmological research, particularly regarding its fundamental pathophysiological functions, such as oxidative stress, angiogenesis, inflammatory responses, and neurodegeneration. These processes are pivotal in the development of ocular diseases, and the regulatory mechanisms of m6A modification in these pathways require further exploration.

Oxidative stress

Oxidative stress (OS) refers to an imbalance between the oxidative and antioxidant systems within the body, typically characterized by an increased production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Reactive Nitrogen Species (RNS). When this imbalance surpasses the body’s antioxidant capacity, it disrupts the intracellular redox balance and results in cellular damage [62].

OS can damage retinal vascular endothelial cells, contributing to retinal vascular diseases such as Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) and Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) [63]. Crystallins, which are major proteins in the lens, play a crucial role in maintaining transparency. Excessive ROS induces conformational changes in crystallin proteins, ultimately leading to cataracts [64, 65]. OS markers, including 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8OHdG) and malondialdehyde (MDA), are elevated in the serum, aqueous humor, and trabecular meshwork of glaucoma patients. These markers are strongly correlated with elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), visual field defects, and an increased cup-disc ratio (CDR) [66, 67]. Moreover, antioxidants have shown promise in treating dry eye disease. For example, vitamin B12 eyedrops and hyaluronic acid-containing eyedrops have been shown to reduce oxidative stress and improve dry eye symptoms [68]. Recent studies indicate that m6A modification plays a pivotal role in the development of various oxidative stress-related ocular diseases, offering a promising new avenue for treatment based on m6A modulation [69].

Angiogenesis

Angiogenesis is crucial for wound healing and tissue repair under normal physiological conditions. However, abnormal angiogenesis can lead to severe vision loss and, in some cases, irreversible blindness in ocular diseases [70, 71]. For instance, wet AMD is triggered by excessive activation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), resulting in abnormal vascular growth, leakage, and macular damage, which contribute to significant visual impairment. While current anti-VEGF therapies slow disease progression, they do not fully reverse visual loss [72, 73]. Similarly, Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) is closely associated with abnormal angiogenesis and can lead to retinal vascular injury due to hyperglycemia (HG), inducing abnormal vessel formation, rupture, and bleeding. These changes result in blinding complications such as retinal edema, vitreous hemorrhage, and retinal detachment [74]. Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) causes retinal hypoxia due to obstructed venous blood flow, stimulating the release of pro-angiogenic factors like VEGF and precipitating abnormal vascular growth. These newly formed blood vessels, characterized by their immaturity, susceptibility to bleeding, and leakage, can further damage retinal structure and impair visual acuity [75, 76].

Hypoxia is a primary driver for the release of pro-angiogenic factors, and recent studies have demonstrated that m6A modification regulates hypoxia-induced angiogenic processes [77]. For example, hypoxia-induced upregulation of METTL3 was observed in endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), activating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, which subsequently promoted EPC-mediated angiogenesis [78]. In contrast, under hypoxic conditions, ALKBH5 expression increases in cardiac microvascular endothelial cells, leading to a reduction in m6A levels. This decrease in m6A triggers WNT5A mRNA degradation, ultimately inhibiting angiogenesis [79]. These findings highlight that m6A-related regulators exert complex effects on angiogenesis, depending on the cellular context.

Previous studies have highlighted the critical role of METTL3-dependent m6A modification in hypoxia-induced pathological ocular angiogenesis, demonstrated through an in vivo ocular neovascularization model [80]. Under hypoxic conditions, METTL3 activity increases, upregulating the protein expression of MMP2 and TIE2 via m6A modification. This, in turn, promotes the migration and tubular formation ability of Retinal Endothelial Cells (RECs), ultimately driving abnormal angiogenesis [81]. Additionally, Cytochrome P450 epoxygenase 2J2 (CYP2J2) overexpression enhances Annexin A1 (ANXA1) protein expression through METTL3-mediated ANXA1 m6A modification, protecting retinal vascular endothelial cells from oxidative stress and preserving the integrity of the Blood-Retinal Barrier (BRB) [82]. Furthermore, FTO regulates endothelial cell (EC) function and Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK) expression via its demethylase activity and the m6A-YTHDF2-dependent mechanism, contributing to pathological angiogenesis [83].

Angiogenesis is intricately linked to oxidative stress, often resulting from tissue hypoxia and unmet oxygen demands. Under physiological conditions, moderate oxidative stress promotes angiogenesis, playing a vital role in tissue repair and regeneration. However, excessive oxidative stress can lead to abnormal angiogenesis and vascular dysfunction under pathological conditions [84, 85].

Inflammatory response

Inflammation is the body’s immune response to injury or infection, characterized by redness, swelling, heat, pain, and dysfunction, with the primary aim of clearing pathogens and repairing tissues. In ocular diseases, inflammation activates a variety of cells and signaling pathways that drive pathological processes, with m6A modification playing a central role in regulating these processes.

Feng et al. found that FTO downregulation under diabetic conditions (DM) promotes macrophage polarization toward the M1 type, enhances the expression of inflammatory mediators, and exacerbates diabetic retinopathy (DR)-related microvascular inflammation. Mechanistically, FTO regulates FGF2 mRNA through YTHDF2-dependent m6A modification and activates the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway [86]. Dry eye disease (DED) is often secondary to DM. Guo et al. observed that the expression of WTAP and NEAT1 was upregulated in a mouse model of diabetic dry eye (DMDED), leading to severe corneal injury and inflammation. Knockdown of WTAP/NEAT1 alleviated these symptoms [87]. Moreover, the DM-induced hyperglycemic (HG) environment leads to FTO upregulation, which removes the m6A modification from TNIP1 mRNA, decreasing its stability and reducing TNIP1 protein expression. The reduction of TNIP1 relieves the inhibition of the NFκB signaling pathway, resulting in elevated levels of inflammatory factors (e.g., IL-1β and IL-18) and exacerbating retinal vascular inflammation and endothelial dysfunction [88]. Decreased FTO may promote microglial inflammation in autoimmune uveitis (EAU), suggesting that restoring or activating FTO function could serve as a potential therapeutic strategy for uveitis [89].

The complexity of m6A regulation

The expanding body of research on m6A in ocular diseases reveals a complex and often context-dependent regulatory landscape. A critical examination of apparent inconsistencies in the functions of individual m6A regulators is essential for a nuanced understanding of their roles in pathophysiology.

The expression and pathological contribution of the demethylase FTO demonstrate striking divergence across different disease environments, sometimes presenting a seeming paradox. In diabetic retinopathy, recent studies have demonstrated that FTO expression is upregulated in endothelial cells under diabetic conditions. This increase, driven by lactate-mediated histone lactylation, promotes angiogenesis, disrupts vascular integrity, and exacerbates inflammation by enhancing the m6A-dependent mRNA stability of targets like CDK2, thereby positioning FTO as a key driver of pathology [90]. In contrast to a hypothetical pro-inflammatory role, accumulating evidence indicates that FTO is downregulated in microglia during uveitis. This downregulation exacerbates the disease by disrupting m6A homeostasis and activating the GPC4/TLR4/NF-κB pathway, positioning FTO as a potential suppressor of microglia-driven inflammation [89].

The role of the methyltransferase METTL3 in inflammatory eye diseases demonstrates a complex, context-dependent pattern. In experimental autoimmune uveitis (EAU), METTL3 expression is significantly decreased in T cells, and its overexpression ameliorates disease by suppressing pathogenic Th17 responses through the ASH1L-YTHDC2 axis, revealing a clear anti-inflammatory function in this specific cellular context [91]. This protective role stands in contrast to its reported functions in broader immune dysregulation, where METTL3 is often associated with suppressing antiviral immunity and disrupting immune tolerance, with its overexpression linked to increased susceptibility to viral infections and autoimmune conditions [92]. These divergent findings underscore that the function of METTL3 is not intrinsic but is determined by the specific disease environment and, critically, the cell type in which it is expressed—demonstrating distinct consequences in lymphoid cells (e.g., T cells) versus myeloid cells.

In conclusion, the seemingly paradoxical functions of m6A regulators like FTO and METTL3 are not experimental artifacts but rather reflections of a sophisticated and dynamic regulatory network. Their ultimate biological output is determined by a confluence of factors, including the specific pathological context, cell type, disease stage, and the particular repertoire of target mRNAs they act upon. Acknowledging and systematically investigating this complexity is a crucial step toward moving from phenomenological observations to a mechanistic understanding that could inform future therapeutic strategies.

The multifaceted roles of m6A modification in specific ocular disease

As the core organ of visual perception, the integrity of both the structure and function of the human eye is essential for maintaining clear vision. The complexity of the eye is reflected not only in its intricate anatomy but also in its unique physiological functions and high sensitivity to various internal and external stimuli. In recent years, with the deepening of ocular disease research, m6A modification—a key epigenetic regulatory mechanism—has emerged as an important area of study. M6A modification plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of various ocular diseases by regulating gene expression, RNA stability, and translational efficiency. From oxidative stress to neurodegeneration, and from inflammatory responses to angiogenesis, m6A modification exerts diverse regulatory roles in different pathological processes. However, its specific mechanism of action in various ocular diseases remains incompletely understood, and in some cases, it may exert opposing effects. Therefore, a comprehensive investigation into the role of m6A modification in specific ocular diseases will not only illuminate its function in the development of eye diseases but also offer new insights for the development of targeted therapeutic strategies (Fig. 3).

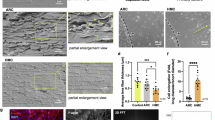

A Key regulatory factors of m6A modification in different ocular cell types and related diseases. This includes the expression and function of m6A methyltransferases (METTL3, METTL14), demethylases (FTO, ALKBH5), and reader proteins (YTHDF1, YTHDF2, IGF2BP1) in retinal ganglion cells (glaucoma, optic neuritis), endotheliocyte (diabetic retinopathy, age-related macular degeneration, retinopathy of prematurity), microglia (glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, uveitis), and RPE cells (diabetic retinopathy, retinitis pigmentosa, age-related maculardegeneration). B Molecular regulatory pathways of m6A modification in the ocular microenvironment. a FTO regulates COX10mRNA, affecting ATP production; METTL3 participates in the autophagy process by regulating Beclin1 mRNA. b METTL3/YTHDF1/YTHDF2 and FTO respectively regulate VEGF-A and Nrf pathways, influencing angiogenesis and oxidative stress. c METTL3 mediates inflammatory factors TNF-α/IL-6, and METTL14 is associated with iNOS mRNA expression, participating inneurotoxic responses. d ALKBH5 and YTHDF2 regulate RPE65 and TFEB mRNA, affecting retinol metabolism and mitochondrialfunction; METTL3/YTHDF1 regulate p16INK4a expression, participating in the cell cycle process.

Anterior segment and adnexal diseases

Keratitis

Keratitis is a common corneal disorder, typically characterized by pain, redness, lacrimation, photophobia, and decreased vision, often caused by bacteria, fungi, or viruses [93, 94]. If left untreated, infectious keratitis can result in corneal scarring, leading to opacity and significantly impairing vision [95, 96].

Fungal keratitis (FK) is a severe corneal infectious disease associated with vision loss. It is highly destructive and can result in permanent blindness or even the loss of the eyeball [97]. The main pathogens of FK include Fusarium, Aspergillus, and Candida, with Fusarium solani (F. solani) being the most commonly reported species [98]. In investigating the role of METTL3 in F. solani-induced FK, studies by Hu et al. and Huang et al. have each contributed to this area. Hu et al. focused on global changes in m6A modification and transcriptome analysis, revealing a broad upregulation of m6A modification in corneal tissue following infection. Huang et al. further explored the specific mechanism of METTL3 in the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and found that METTL3 significantly influences the onset and progression of keratitis by regulating this pathway. The findings of these two studies complement one another, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the role of m6A modification in fungal keratitis. [99, 100]. Moreover, Tang et al. demonstrated that inhibition of METTL3 mitigated the reduction in NFκB signaling, thereby alleviating Fusarium solani keratitis [101]. Therefore, METTL3 may regulate multiple signaling pathways that contribute to the development of FK, making it a potential target for therapeutic strategies.

Corneal neovascularization

Corneal neovascularization is typically triggered by factors such as trauma, infection, ischemia, hypoxia, inflammation, or following keratoplasty. It compromises vision by activating pro-angiogenic factors that promote the growth of blood vessels from the limbus to the center of the cornea, leading to the loss of corneal transparency [102].

Yao et al. found that hypoxia significantly increased m6A modification levels in both in vitro cell experiments and in vivo animal models. This increase may influence angiogenesis by regulating the expression of genes involved in the process. Moreover, hypoxia activated Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF), which induced METTL3 expression and promoted angiogenesis. Yao et al. further validated the role of METTL3 in pathological angiogenesis using an alkali burn-induced mouse corneal neovascularization model. METTL3 regulates the expression of Wnt signaling pathway-related genes (e.g., LRP6 and DVL1) through m6A modification, which subsequently affects angiogenesis. In the alkali burn model, specific knockdown of METTL3 reduced the expression of these genes, inhibiting neovascularization [80].

In addition, Dai et al. found that METTL3 knockout mice exhibited a significantly faster rate of corneal injury repair in an alkali burn-induced model, with sodium fluorescein staining showing a markedly increased rate of repair. This result may be linked to METTL3’s regulation of target genes AHNAK and DDIT4 expression through m6A modification, which in turn inhibits the function of limbal stem cells (LSCs). Previous studies have shown that LSCs suppress the formation of vascular endothelial cells under normal conditions, and their loss of function leads to the generation of new blood vessels [103, 104]. Therefore, knockdown of METTL3 may accelerate corneal injury repair and reduce neovascularization by relieving the inhibition of LSCs, promoting their proliferation and migration [105]. Wang et al. also found that METTL3, which is highly expressed in the herpes stromal keratitis (HSK) mouse model, promotes pathological angiogenesis through canonical Wnt and VEGF signaling in vitro and in vivo, providing a potential pharmacological target to prevent the progression of corneal neovascularization in HSK [106].

Furthermore, Shan et al. found that FTO silencing inhibited endothelial cell function and corneal neovascularization by increasing m6A modification levels, which prompted YTHDF2 to degrade FAK mRNA, resulting in decreased Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK) protein expression [83].

In summary, m6A modification plays a pivotal role in the formation of corneal neovascularization and injury repair by regulating key genes and signaling pathways. Therefore, precise modulation of m6A modification levels may provide novel strategies for the prevention and treatment of corneal neovascularization.

Cataract

The lens focuses light onto the retina through its transparent biconvex structure, forming a clear image essential for visual function [107]. Cataracts are caused by lens opacities, most of which develop after birth, primarily due to aging and oxidative stress [108]. Cataracts are classified into age-related cataract (ARC), congenital cataract, traumatic cataract, and metabolic cataract. ARC primarily affects individuals over 50 years of age and results from the gradual opacification of the lens with age, making it the most common type of cataract. Based on anatomical location or opacity features, cataracts can also be categorized as nuclear (opacification of the fetal and adult nucleus), cortical (spoke-like opacification of the lens fibers), and posterior (plaque-like opacification in the back portion of the lens fibers). From 2000 to 2020, cataract-related blindness increased by 30%, while moderate to severe visual impairment rose by 93%. Although advances in cataract surgery have reduced cataract-related blindness, the overall number of cataract cases continues to rise due to the aging population, particularly the increasing number of individuals over 60 years of age [108].

In the Malay adult population in Singapore, Lim et al. found through Mendelian randomization that rs9939609 in the FTO gene was significantly associated with an increased risk of nuclear cataract, but not cortical or posterior subcapsular cataract [109]. In a northern Indian population, Chandra et al. conducted a case-control study and found that this locus was significantly associated with an increased risk of cataracts, although it did not clearly differentiate between cataract subtypes [110]. Despite differences in study methods, these findings suggest that FTO gene polymorphisms may influence the development of cataracts through mechanisms independent of obesity. However, the specific mechanisms of action and affected cataract subtypes appear to vary across populations and warrant further investigation.

Investigating the effect of lens epithelium cell (LEC) RNA transcripts on cataract formation is critical, as the integrity and metabolic activity of LECs are essential for maintaining lens transparency. These functions depend on a normal transcriptome. Multiple proteins involved in m6A modification have been found to be aberrantly expressed in LECs from cataract patients. For instance, levels of m6A-modified circular RNAs (circRNAs) were found to be significantly reduced in LECs from age-related cataract (ARC) patients compared to normal controls, with high m6A-modified circRNAs predominantly downregulated. These m6A-modified circRNAs are closely associated with ARC-related pathways, including oxidative stress, DNA damage repair, and autophagy, suggesting that m6A modification may play a role in ARC development by inhibiting circRNA expression. Additionally, the demethylase ALKBH5 is significantly upregulated in ARC patients and may affect m6A-modified circRNAs through demethylation, thereby promoting ARC pathogenesis [111].

Additionally, Li et al. determined that m6A modification was significantly upregulated in ARC through MeRIP-Seq, with methyltransferase METTL3 being significantly increased in ARC tissues and high glucose-induced lens epithelial cells (HLE-B3). METTL3 overexpression was shown to promote m6A modification and the expression of hascirc0007905, which regulates EIF4EBP1 expression by sponging miR-6749-3p. Upregulation of EIF4EBP1 suppressed proliferation and promoted apoptosis in HLE-B3 cells, driving ARC development. This study highlights the critical role of the METTL3/hascirc0007905/miR-6749-3p/EIF4EBP1 axis in ARC and provides a novel target for ARC treatment [112].

Diabetic cataract (DC) is a type of metabolic cataract caused by lens metabolic disorders resulting from long-term hyperglycemia (HG), leading to lens opacification. Its pathogenesis is closely associated with oxidative stress and apoptosis in lens epithelial cells (LECs). Recent studies have revealed that m6A modification reduces the expression of its target gene superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) through METTL3-mediated miR-4654 maturation, exacerbating oxidative stress and apoptosis in LECs, and promoting lens opacification [113]. Moreover, METTL3 was found to be upregulated in high glucose-induced HLECs by MeRIP-Seq analysis, where it contributes to the pathogenesis of DC by targeting the 3’ UTR of ICAM-1, stabilizing its mRNA, and promoting protein expression [114].

Interestingly, Cai et al. revealed a significant increase in m6A modification levels in DCs and notable changes in m6A modification across multiple mRNAs, as determined through microarray analysis of the m6A transcriptome. Gene ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment analysis indicated that these differentially expressed mRNAs were primarily enriched in the ferroptosis pathway, suggesting that m6A modification may play a role in DC progression by regulating this pathway. Furthermore, the RNA methyltransferase RBM15 was found to be significantly upregulated in DCs, potentially promoting oxidative stress and ferroptosis in lens epithelial cells through m6A modification, thereby driving disease progression [115].

Overall, while significant progress has been made in studies of m6A modification in cataracts, a consistent observation across different types of cataracts is that METTL3 promotes LEC apoptosis. However, many unresolved questions remain in the existing literature. For example, is the regulatory mechanism of m6A modification in DC consistent with that in ARC? Is there a specific m6A modification pattern or target that can distinguish DC from ARC? Furthermore, the precise role of the ferroptosis pathway in DC remains unclear. How does m6A modification affect the survival of LECs by regulating the ferroptosis pathway, thereby influencing DC pathogenesis? Addressing these questions will help further elucidate the complex mechanisms of m6A modification in cataracts and provide new insights for the development of targeted therapeutic strategies.

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a leading irreversible cause of blindness worldwide, characterized by optic nerve damage and the progressive loss of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). The primary causes are elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) or impaired retinal blood flow, which result in thinning of the optic nerve fiber layer and cupping of the optic disc, leading to visual field defects and decreased visual acuity [116]. However, not all patients with elevated IOP develop glaucoma, and some individuals may present with typical glaucomatous optic neuropathy, known as normal tension glaucoma (NTG), even within the normal IOP range. The pathogenesis of glaucoma is multifactorial, involving genetics, oxidative stress, mechanical compression, vascular compression, neuroinflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Oxidative stress is closely associated with cellular aging, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neuroinflammation, all of which contribute to the pathological progression of glaucoma [117]. With the aging global population, the incidence of glaucoma is expected to continue rising, presenting a significant public health challenge [118].

Pseudoexfoliation glaucoma (PXG) is a major form of secondary glaucoma, characterized by the accumulation of abnormal extracellular fibrillar material in anterior segment structures. This leads to increased trabecular meshwork outflow resistance, elevated IOP, and, ultimately, optic nerve injury and visual field defects [119, 120].

Guan et al. analyzed the m6A modification profile in aqueous humor (AH) from PXG patients and found that m6A levels were significantly higher than those in ARC patients, suggesting that m6A modification may play an important regulatory role in PXG. Transcriptome analysis revealed numerous differential m6A modification peaks in the AH of PXG patients, primarily enriched in coding sequences (CDS) and 3’-untranslated regions (3’-UTR), which may influence the pathological process of PXG by regulating mRNA stability, translational efficiency, and intracellular localization. Additionally, m6A modification is closely associated with extracellular matrix (ECM) formation and histone deacetylation in PXG. Genes such as MMP14, ADAMTSL1, FN1, and HDAC1 exhibited significant m6A methylation and expression changes in PXG, highlighting the importance of ECM remodeling and cell phenotype regulation in the disease [121].

Additionally, recent studies have shown that lncRNAs in the aqueous humor (AH) of PXG patients exhibit significant m6A modification differences, which may contribute to the pathogenesis of PXG by influencing the expression and function of lncRNAs. By constructing an lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) network, it was found that specific lncRNAs (e.g., ENST00000485383) may bind multiple miRNAs through a sponge mechanism, relieving their inhibition of downstream mRNA (e.g., ROCK1) expression. This interaction may influence the inflammatory response of retinal pigment epithelial cells and the fibroproliferation of trabecular meshwork cells [122].

These findings not only offer new insights into the pathogenesis of PXG but also provide a direction for further investigation into its pathophysiology and potential therapeutic targets, which could lead to breakthroughs in PXG research. Future studies should validate these mechanisms through cellular and animal models and assess their generalizability across diverse ethnic and geographical populations.

The degeneration of RGCs shares a similar pathomechanism with Retinal Ischemia-Reperfusion (RIR) injury [123]. Recent studies have shown that RIR injury activates the autophagic process, leading to RGC death and impaired retinal electrophysiological function. Further mechanistic studies revealed that METTL3-mediated m6A modification levels decreased after RIR injury. Overexpression of METTL3 reduced FoxO1 protein expression by increasing m6A modification on FoxO1 mRNA, thereby inhibiting autophagy activation and protecting RGCs. Moreover, the use of FoxO1 inhibitors also alleviated RGC loss and retinal dysfunction caused by RIR injury by inhibiting autophagy [124]. In contrast, YTHDF2 is highly expressed in mouse RGCs, and its conditional knockout (cKO) significantly increased dendritic branch complexity in RGCs, while improving visual function. In an acute intraocular pressure elevation (AOH)-induced glaucoma model, RGCs from YTHDF2 cKO mice showed greater resistance to injury, reduced dendritic atrophy, and less neuronal loss [125].

Glaucoma Filtration Surgery (GFS) is a standard surgical approach for treating glaucoma, but postoperative scar formation remains the primary cause of surgical failure [126]. Studies have shown that excessive activation of human Tenon’s capsule fibroblasts (HTFs) and abnormal accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) are key factors in scar formation [127]. TGF-β1 was found to significantly enhance the proliferation and ECM accumulation of HTFs, elevating m6A modification levels by upregulating METTL3. Moreover, METTL3 modulated HTF function by regulating mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 3 (Smad3) expression. Overexpression of Smad3 reversed the inhibitory effect of METTL3 inhibition on ECM accumulation and cell proliferation. In a rabbit GFS model, METTL3 and Smad3 expression were significantly elevated in postoperative scar tissue, further confirming the critical role of the METTL3/Smad3 axis in scar formation after GFS [128].

In summary, m6A modification could serve as a potential therapeutic target for glaucoma by influencing gene expression and regulating cell phenotype. However, current studies have not fully elucidated the universal role of m6A modification in different glaucoma subtypes or its specific molecular mechanisms. While certain m6A-related genes, such as METTL3 and YTHDF2, have been identified as regulated in glaucoma models, it remains unclear whether the m6A modification pattern is consistent across all patients or universally applicable across different ethnic groups and individuals. This question requires further in-depth investigation. Therefore, accurately regulating m6A modification may represent a crucial direction for future glaucoma treatment research.

Uveitis

Uveitis is a complex disease characterized by intraocular inflammation, primarily affecting uveal structures such as the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. It is classified into two major categories: infectious and non-infectious. The former is primarily caused by pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, or parasites, while the latter is often associated with systemic immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), and Behcet’s disease [129]. Uveitis can present as either acute or chronic inflammation, involving the anterior, middle, or posterior segments of the eye, or even the entire uvea. Symptoms vary and include eye redness, pain, photophobia, blurred vision, and dark shadows, which, in severe cases, can lead to vision loss or blindness [130]. Globally, uveitis is a significant cause of visual impairment, particularly among children and adolescents, with a high incidence and rate of blindness. Due to its complex etiology, diagnosis, and treatment require close collaboration between ophthalmology and rheumatology is required to identify the underlying cause and develop an individualized treatment plan [131].

Microglia are the primary immune effector cells of the retina, exhibiting high plasticity and playing a critical role in the pathogenesis of uveitis. Their activation state is primarily categorized into two types: the M1 pro-inflammatory “classical activation” state and the M2 anti-inflammatory “alternative activation” state [132].

In the experimental autoimmune uveitis (EAU) mouse model and a LPS/IFN-γ-induced inflammatory environment, He et al. observed downregulation of FTO expression. FTO deletion significantly enhanced the pro-inflammatory properties of microglia, as evidenced by increased secretion of inflammatory factors, enhanced cell migration, and significantly elevated chemotaxis toward CD4 T cells. RNA sequencing analysis identified GPC4 as a downstream target gene of FTO, with its upregulation closely associated with the downregulation of YTHDF3. Increased GPC4 expression further activated the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway, driving microglial polarization toward the M1 phenotype and exacerbating the inflammatory response. In vivo, FB23-2, an FTO inhibitor, significantly aggravated inflammation in EAU by activating the GPC4/TLR4/NF-κB signaling axis. However, this exacerbated inflammation was alleviated by TAK-242, a TLR4 inhibitor [89].

Similarly, FTO expression in retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells was significantly downregulated in the EAU mouse model. FTO loss significantly enhanced the pro-inflammatory properties of RPE cells, as evidenced by increased secretion of inflammatory factors, enhanced cell migration, and decreased expression of tight junction proteins (e.g., ZO-1 and occludin). Further studies revealed that FTO regulates the translation efficiency of ATF4 by modulating its m6A modification level. Knockdown of FTO resulted in increased m6A modification of ATF4, thereby suppressing ATF4 protein expression. As a key transcription factor, reduced ATF4 expression activates the p-STAT3 signaling pathway, promoting the secretion of inflammatory factors and the degradation of tight junction proteins. Moreover, low FTO expression has been associated with enhanced proliferative capacity in RPE cells, potentially exacerbating the inflammatory response [133].

Moreover, significant downregulation of YTHDC1 expression in retinal microglia is closely associated with uveitis. Loss of YTHDC1 impairs the maintenance of SIRT1 mRNA stability, making it more prone to degradation, which in turn reduces SIRT1 protein levels. This alteration promotes acetylation and phosphorylation of STAT3, ultimately driving microglial polarization toward the M1 phenotype. This polarization is characterized by a marked upregulation of pro-inflammatory markers such as iNOS and COX2, along with increased expression of inflammatory factors like TNF-α, thereby exacerbating the inflammatory response in uveitis [134].

Pathogenic Th17 cells play a critical role in the pathology of uveitis [135]. The significance of METTL3 in EAU was first demonstrated in 2023 by Zhao et al. It was observed that METTL3 expression and m6A levels were both reduced in the ocular tissues and T cells of EAU mice. Lentivirus-mediated overexpression of METTL3 restored m6A levels, significantly alleviated EAU symptoms, reduced inflammatory cell infiltration, and improved retinal structural damage. METTL3 decreases Th17 cell activity by stabilizing ASH1L mRNA, inhibiting pathogenic Th17 cell responses, and reducing the expression of IL-17 and IL-23R. YTHDC2 plays a pivotal role in regulating ASH1L mRNA stability through METTL3, and its knockdown weakens the regulatory effect of METTL3 [91].

In the same year, Wei et al. injected miR-338-3p overexpressing dendritic cells (DCs) into mice with EAU and observed more severe symptoms, including increased inflammatory cell infiltration and retinopathy, as observed through ophthalmoscopy and OCT imaging. DCs are central to the development of Th17 cells, acting as a crucial bridge between innate and adaptive immunity. They provide essential microenvironmental support for Th17 cell polarization by secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-23. METTL3 significantly upregulated miR-338-3p expression by promoting the maturation of pri-miR-338 and alleviating its inhibition of the p38 signaling pathway by targeting dual-specificity phosphatase 16 (Dusp16), thereby enhancing the ability of DCs to secrete cytokines associated with Th17 cell polarization [136].

In summary, the effect of METTL3 in uveitis varies depending on cell type and experimental conditions. In the EAU model, METTL3 expression was significantly reduced in T cells and ocular tissues, and this reduction was closely associated with disease severity, suggesting that downregulation of METTL3 may promote the pathogenic response of Th17 cells, thereby exacerbating the development of EAU. However, METTL3 expression in DCs exhibited the opposite trend, ultimately enhancing Th17 cell polarization and pathogenic responses. This difference highlights the complex regulatory mechanisms of METTL3 in various cell types and pathological conditions, underscoring its versatility in immune responses. Therefore, differences in cell types and experimental conditions must be thoroughly considered when investigating METTL3’s role in uveitis to gain a comprehensive understanding of its mechanism in disease development.

Zhou et al. were the first to elucidate the distinctive metabolic profile of modified nucleosides in the serum of uveitis patients. Using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), they analyzed a total of 23 modified nucleosides, identifying 13 that were significantly altered in patients compared to healthy controls. Notably, different subtypes of uveitis exhibited unique combinations of these modified nucleosides. This discovery not only introduces novel biomarkers for more accurate diagnosis but also offers fresh insights into the underlying pathomechanisms of uveitis [137]. Furthermore, the findings underscore the potential role of RNA modifications in uveitis, laying a theoretical foundation for the development of “RNA epigenetics-based” diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Such strategies could significantly advance the progress of precision medicine for uveitis.

Graves’ ophthalmopathy (GO)/thyroid eye disease (TED)

GO, also known as TED, is the most common extrathyroidal manifestation of Graves’ disease and is classified as an autoimmune disorder. Its pathogenesis is complex and primarily involves the abnormal expression of thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR) in orbital tissues, which triggers inflammation and tissue remodeling in orbital fat, fibrocytes, and extraocular muscles (EOMs). This leads to exophthalmos, eyelid retraction, diplopia, and visual impairment. The pathogenesis of GO is closely associated with genetic and environmental factors, as well as thyroid dysfunction [138]. Treatment for GO depends on the severity and activity of the disease. Mild GO is generally managed symptomatically, while glucocorticoids are commonly required for moderate to severe active GO, although the recurrence rate remains high. Recently, targeted therapies such as teprotumumab, an insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R) blocker, have shown promising efficacy, offering new hope for treatment. Surgical intervention may be necessary for refractory or advanced cases of GO [139, 140].

Zhu et al. found significantly elevated m6A levels in EOM samples from GO patients, suggesting that m6A methylation may play a crucial role in the pathology of GO. Aberrant expression of several m6A methylation regulators, including WTAP, ALKBH5, and YTHDF2, was also observed. Changes in the expression of these regulators were closely associated with the upregulation of genes involved in inflammation and immune responses, indicating that m6A methylation may influence the inflammatory response in GO by regulating these genes. Furthermore, the expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, TNF, and IFN-γ, was significantly increased in the EOM of GO patients, further supporting the critical role of m6A methylation in the inflammatory pathology of GO [141]. Importantly, specific autoantibodies against EOM antigens have been identified in GO patients, strongly suggesting that EOM is a major target of autoimmune attack [142, 143].

DR is closely associated with the presence of DM, and similarly, the onset of GO/TED is strongly linked to thyroid disease. Recent studies have demonstrated a clear association between m6A modification and thyroid disease, which not only aids in understanding the pathogenesis of GO/TED but also provides a theoretical foundation for the development of targeted treatments and preventive strategies. HNRNPC significantly enhanced the transcriptional activity and translational efficiency of ATF4 by mediating its m6A modification. Activated ATF4 induced apoptosis and necrosis of thyroid follicular epithelial cells (ThyFoEp) through the ER stress pathway, contributing to the progression of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT) [144]. Additionally, METTL3 expression was downregulated in thyroid tissue from Graves’ disease (GD) patients, accompanied by upregulation of suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) family members. This suggests that METTL3 may influence immune cell function by regulating the m6A modification of SOCS family mRNAs, thereby playing a role in the pathogenesis of GD [145].

Despite significant progress in revealing epigenetic regulatory networks in thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy (TAO), this study has some limitations, including a small sample size, a lack of mechanistic validation, insufficient investigation of dynamic changes in epigenetic modifications, and limited depth of multi-omics data integration. Such limitations may impact the scope and practical value of the study’s conclusions. Future studies should validate these findings further and explore their potential clinical applications in TAO management by expanding sample size, conducting in vitro and in vivo experiments, analyzing dynamic changes in epigenetic modifications, and integrating multi-omics data more comprehensively.

Recent studies have revealed the epigenetic regulatory network in thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy (TAO) through the integration of multi-omics sequencing data, including DNA methylation, RNA-seq, and tRFs sequencing. These studies have shown that epigenetic modification levels undergo significant changes in TAO patients and are closely associated with the PI3K-Akt and IL-17 signaling pathways. In particular, m6A methylation regulates numerous genes involved in key processes such as cytokine production, immune response, and cell chemotaxis [146]. However, the study relied solely on bioinformatics analysis. Moving forward, dynamic changes in epigenetic modifications should be analyzed in greater detail through in vitro and in vivo experiments. Additionally, the integration of multi-omics data should be further refined to validate these findings and explore their potential applications in the clinical management of TAO.

Although these studies provide new insights into the pathogenesis of GO/TED, existing research is limited to a single molecular mechanism and does not fully elucidate the complex interactions between m6A methylation and other epigenetic modifications. An important question for future studies is whether they can explore the synergistic effects of various epigenetic modifications (e.g., DNA methylation, non-coding RNAs) in GO/TED, thereby offering a more comprehensive theoretical foundation for precision treatment.

Posterior segment diseases

Diabetic retinopathy (DR)

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is one of the primary microvascular complications of diabetes mellitus (DM) and remains the leading cause of vision loss in working-age individuals. According to the 2021 data from the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), approximately 537 million adults worldwide are living with DM, with projections indicating that this number will rise to 783 million by 2045 [147]. It is estimated that between 20% and 50% of DM patients will develop DR, a condition closely associated with prolonged hyperglycemia (HG), hypertension, and obesity [148]. Children and adolescents diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (T2D) face an extended disease course and are at a heightened risk for DR, with a significantly increased prevalence observed beyond five years after diagnosis [149]. Current treatment options for DR include anti-VEGF therapy, laser photocoagulation, and vitrectomy, although these interventions have limitations in terms of efficacy and are often accompanied by side effects [150]. Consequently, annual DR screening is strongly recommended for all patients with DM. Concurrently, further investigations into the pathogenesis of DR, as well as the identification of novel diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets, are essential for improving patient outcomes and reducing the risk of vision impairment. Recent advances in research on m6A modification—an important epigenetic modification—have shed new light on its potential role in DR, offering valuable insights into the complex mechanisms underlying this disease.

The Neurovascular Unit (NVU) encompasses a variety of cellular components, including retinal vascular endothelial cells, pericytes, neuroglial cells (such as Müller cells and retinal microvascular cells, rMC), neurons, and resident immune cells (e.g., microglia). The primary functions of the NVU are to maintain the integrity of the blood-retinal barrier (BRB), regulate retinal blood flow, support neural function, and modulate immune responses, thereby ensuring the normal physiological activity of the retina [151]. Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is classified into two main types: non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) and proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) [152]. NPDR is further divided into mild, moderate, and severe stages based on the severity of the disease. It is primarily characterized by microaneurysms, hemorrhages, and exudates, which reflect abnormal changes in the retinal vasculature. In contrast, PDR represents the advanced stage of DR, typically triggered by retinal ischemia and hypoxia, which induce retinal neovascularization (RNV). These neovascularizations are fragile and prone to rupture and bleeding, potentially leading to significant vision loss and, in severe cases, blindness [153].

Studies have shown that abnormal changes in the migration, proliferation, and capillary lumen formation of retinal microvascular endothelial cells (RMECs) are closely associated with the development of retinal neovascularization (RNV) and the progression of proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) [154]. Additionally, retinal microglial cells (rMCs), the principal glial cells of the retina, undergo gliosis under pathological conditions and secrete various pro-inflammatory factors, including IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and VEGF. These factors play a critical role in key pathological processes such as retinal inflammation, vascular leakage, and abnormal RNV formation [155, 156]. Lysine acetyltransferase 1 (KAT1), a key epigenetic regulator, has garnered attention due to its potential involvement in DR. Research by Qi et al. revealed that KAT1 expression is significantly downregulated in the retinal tissue of diabetic mice. Interestingly, overexpression of KAT1 was found to notably inhibit retinal inflammation, RNV formation, and vascular leakage. Molecular mechanistic studies indicated that KAT1 accelerates the degradation of ITGB1 mRNA and suppresses its protein expression by activating the transcription of YTHDF2, which enhances the m6A modification of ITGB1 mRNA. This process not only impedes the proliferation and migration of RMECs but also mitigates the abnormal activation and inflammatory response of rMCs by inhibiting the FAK/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway [157]

Pericytes, which surround the endothelial cells (ECs) of capillaries, play a crucial role in maintaining vascular integrity and function [158, 159]. Dysfunction of pericytes can lead to endothelial cell abnormalities and contribute to microvascular complications [160]. In diabetic retinopathy (DR), hyperglycemia (HG) triggers pericyte dysfunction, resulting in microaneurysms, destruction of the blood-retinal barrier (BRB), disruption of pericyte-endothelial cell interactions, and the formation of pathological retinal neovascularization (RNV). These alterations are closely associated with capillary remodeling, fibrosis, and retinal detachment [161, 162]. In the context of diabetes mellitus (DM), the upregulation of m6A modification mediated by METTL3 suppresses the expression of key genes, including PKC-η, FAT4, and PDGFRA. This inhibition impairs the survival, proliferation, and differentiation of pericytes, ultimately contributing to retinal vascular complications. In vitro experiments demonstrated that silencing METTL3 significantly alleviated high glucose-induced apoptosis and dysfunction of pericytes. Additionally, specific knockdown of METTL3 in pericytes in a diabetic mouse model reduced pericyte loss, diminished retinal vascular leakage, and alleviated microangiopathy [163].

The retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) normally maintains BRB integrity, regulates nutrient and ion transport, absorbs light energy, and engulfs the outer photoreceptor segment, while also secreting multiple factors to maintain retinal homeostasis [164]. Recently, pyroptosis, a form of programmed cell death, has garnered significant attention due to its crucial role in inflammation and cell injury [165]. In DR, high glucose-induced RPE dysfunction is a critical pathological event. High glucose has been shown to inhibit RPE cell proliferation and induce apoptosis. For example, METTL3 overexpression targets PTEN and activates the Akt signaling pathway by upregulating miR-25-3p, thereby alleviating the inhibitory effect of high glucose on RPE cell proliferation and reducing both apoptosis and pyroptosis [166]. Similarly, circFAT1 is significantly downregulated in high glucose-induced RPE, while its overexpression protects cells from high glucose-induced injury by promoting autophagy and inhibiting pyroptosis [167]. Furthermore, downregulation of miR-192 expression promotes FTO expression and activation of NOD-like receptor pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasomes under high glucose (HG) conditions, subsequently promoting pyroptosis of RPE cells [168].

Moreover, in DR, pathological factors such as high glucose (HG) not only inhibit RPE cell proliferation and induce apoptosis but also disrupt the balance of secreted factors, including the upregulation of pro-angiogenic factors (e.g., VEGF), the downregulation of anti-angiogenic factors (e.g., PEDF), and the increase of inflammatory factors (e.g., IL-6, IL-8). These changes lead to BRB destruction, vascular leakage, pathological RNV formation, and promote DR progression [164]. Therefore, targeting these molecular mechanisms, beginning with RPE cells, could offer new strategies for treating DR and may delay disease progression by regulating pyroptosis and secretory function.

The phenotypic switch of cells is a pivotal biological event, with endothelial-mesenchymal transition (EndoMT) referring to the loss of endothelial cell characteristics and the acquisition of mesenchymal traits by endothelial cells. This process is intricately linked to embryonic development, tissue repair, and several pathological conditions [169]. High glucose impairs endothelial cell (EC) function and induces EndoMT [170]. EndoMT is considered a critical early event in the pathological angiogenesis of retinal vasculopathy, and its regulation by m6A modification plays a crucial role in diabetic retinopathy (DR). METTL3 has been shown to inhibit EndoMT by enhancing the stability of SNHG7 and reducing the stability of MKL1 mRNA. In animal models, overexpression of METTL3 improved retinal architecture and reduced the expression of EndoMT markers, while knockdown of SNHG7 partially reversed these effects. These findings suggest that METTL3 plays a protective role in DR and highlight potential therapeutic strategies targeting m6A modification and non-coding RNA regulation [171].

The regulation of FTO plays a critical role in the progression of diabetic retinopathy (DR). Studies have demonstrated that FTO expression is upregulated in both diabetic patients and animal models, leading to a reduction in m6A modification levels. FTO decreases the stability of TNIP1 mRNA, thereby downregulating its protein expression, activating the NFκB pathway, and increasing inflammatory factor levels, such as IL-1β and IL-18. These changes exacerbate diabetes-induced retinal vascular leakage and acellular capillary formation. Endothelial cell-specific FTO knockout mice exhibit protection against DR, and sustained expression of TNIP1 through AAV-mediated gene therapy significantly mitigates diabetes-induced endothelial dysfunction [88]. In addition, FTO promotes angiogenesis by regulating the stability of CDK2 mRNA, facilitating endothelial cell cycle progression and tip cell formation. FTO also contributes to microvascular leakage, retinal inflammation, and neurodegenerative changes in DR by disrupting the interactions between endothelial cells, pericytes, and microglia. Mechanistically, the upregulation of FTO is driven by lactate-mediated histone lactylation (H3K18la), and its demethylase activity impacts CDK2 mRNA stability in a YTHDF2-dependent manner. The FTO inhibitor FB23-2 and its nanoplatform, NP-FB23-2, have been developed and shown to possess effective targeting and therapeutic effects in mouse models [90].

Inflammation plays a central role in the development and progression of diabetic vasculopathy. Notably, the polarization of macrophages into either the M1 pro-inflammatory phenotype or the M2 anti-inflammatory phenotype significantly influences the inflammatory response [172]. Downregulation of FTO expression is strongly associated with macrophage polarization toward the M1 phenotype under diabetic conditions. Recent studies have shown that FTO regulates mRNA stability through an m6A-YTHDF2-dependent pathway, which subsequently affects macrophage polarization. Knockdown of FTO accelerates the degradation of STAT1 and PPAR-γ mRNA, promoting M1 polarization. In contrast, silencing YTHDF2 increases the stability and expression of these mRNAs, inhibits M1 polarization, and reduces the inflammatory response.

Moreover, FTO modulates inflammation by stabilizing FGF2 mRNA and activating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Since fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) promotes macrophage polarization toward the M2 phenotype, the downregulation of FTO, resulting in decreased FGF2 expression, exacerbates M1 polarization and further intensifies inflammation [86].

In summary, the expression levels of FTO in DR studies show significant variability across different cell types and pathological conditions. In fibrovascular membranes (FVMs) from patients with PDR, FTO expression is upregulated and closely associated with elevated inflammatory factors, vascular leakage, and acellular capillary formation. This suggests that the upregulation of FTO in retinal endothelial cells and pericytes may exacerbate diabetes-induced vasculopathy. Conversely, FTO expression is significantly downregulated in THP-1 cells (mimetic macrophages) cultured under HG conditions, which correlates with macrophage polarization toward the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype, thus intensifying the inflammatory response. This contrast underscores the complex regulation of FTO across various cell types and highlights its involvement in multiple pathways within the pathogenesis of DR. Therefore, when considering FTO as a potential therapeutic target, it is essential to carefully assess its specific role in distinct cell types and pathological contexts.

M2 macrophages are typically considered anti-inflammatory and play key roles in tissue repair, immune regulation, and the resolution of inflammation under normal physiological conditions. However, under certain pathological states, the function of M2 macrophages may shift, potentially exacerbating the pathological process. For instance, Gao et al. demonstrated that after corneal injury, a substantial release of cytokines and chemokines induces macrophage polarization toward the M2 phenotype. Nevertheless, this polarization can alter M2 macrophage function, thereby enhancing their role in promoting angiogenesis [173]. In contrast, under diabetic conditions, macrophages tend to polarize toward the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype, a shift closely associated with aggravated tissue inflammation and vascular dysfunction [174, 175].

The rs9939609 polymorphism in the FTO gene is strongly associated with an increased risk of diabetic retinopathy (DR) in patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D). T1D patients carrying the AA genotype exhibit a significantly higher risk of developing DR (OR = 2.203, p = 0.008), whereas the AT genotype appears to confer a protective effect (OR = 0.433, p = 0.003). This association may stem from the regulation of inflammatory status and lipid metabolism by the FTO gene. Specifically, patients with the AA genotype show elevated levels of inflammatory markers, such as CRP, IL-6, and ICAM-1, suggesting that chronic low-grade inflammation may play a pivotal role in the progression of DR. Additionally, the influence of FTO gene polymorphisms on lipid profiles provides a metabolic basis for the increased risk of DR. These findings highlight the critical role of the FTO gene in T1D-related retinopathy and suggest potential new targets for therapeutic intervention in T1D complications [176].

Microglia are resident immune cells in the retina that play a crucial role in retinal inflammation [177]. Under HG conditions, retinal microglia exhibit reduced expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced protein 3 (TNFAIP3, A20), leading to a shift toward increased pro-inflammatory polarization. Moreover, decreased levels of ALKBH5 enhance m6A modification, which accelerates the degradation of A20 mRNA [178]. Additionally, a reduction in ALKBH5 promotes the expression of WNT5A, thereby accelerating angiogenesis in ischemic tissue. [79]. However, the specific mechanisms underlying these processes in the retina remain poorly understood and require further investigation.

DR is a secondary complication of DM, with DM serving as a prerequisite for the development of DR, suggesting a potential link between the two. Since 2015, studies have increasingly shown that reduced levels of m6A modification are strongly associated with the onset of T2D, positioning m6A modification as a potential risk factor and biomarker for the disease [179]. Understanding the regulatory mechanisms of m6A modification in the development of DM could lead to the identification of novel therapeutic targets. Such insights could pave the way for more precise treatments, reduce the incidence of DM and its complications, improve patients’ quality of life, and alleviate the societal medical burden.

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP)

ROP is a prevalent retinal vascular disorder in premature infants, particularly affecting those with very low birth weight and low gestational age. It is a leading cause of visual impairment and blindness in children. The pathogenesis of ROP is complex, involving multiple factors such as premature birth, oxygen exposure, infection, inflammation, and genetic susceptibility [180]. The pathological progression of ROP occurs in two stages: the initial abnormal proliferation of retinal vessels, which can potentially lead to retinal detachment, followed by abnormal vessel dilation and fibrosis, further impairing visual acuity [181]. In recent years, the incidence and severity of ROP have increased, largely due to the improved survival rates of preterm infants, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Currently, laser photocoagulation and anti-VEGF drug injections are the primary treatments; however, these approaches have limitations, including visual field defects, myopia, and systemic side effects. Thus, understanding the pathomechanisms of ROP and developing new diagnostic markers and treatment strategies are crucial for improving the visual outcomes of premature infants [182]