Abstract

Background/objectives

Low vitamin B12 and folate levels in community-dwelling older people are usually corrected with supplements. However, the effect of this supplementation on haematological parameters in older persons is not known. Therefore, we executed a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials (RCTs).

Subjects/methods

We performed a systematic search in PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Cochrane and CENTRAL for RCTs published between January 1950 and April 2016, where community-dwelling elderly (60+ years) who were treated with vitamin B12 or folic acid or placebo. The presence of anaemia was not required. We analysed the data on haematological parameters with a two-stage IPD meta-analysis.

Results

We found 494 full papers covering 14 studies. Data were shared by the authors of four RCTs comparing vitamin B12 with placebo (n = 343) and of three RCTs comparing folic acid with placebo (n = 929). We found no effect of vitamin B12 supplementation on haemoglobin (change 0.00 g/dL, 95% CI: −0.19;0.18), and no effect of folic acid supplementation (change −0.09 g/dL, 95% CI: −0.19;0.01). The effects of supplementation on other haematological parameters were similar. The effects did not differ by sex or by age group. Also, no effect was found in a subgroup of patients with anaemia and a subgroup of patients who were treated >4 weeks.

Conclusions

Evidence on the effects of supplementation of low concentrations of vitamin B12 and folate on haematological parameters in community-dwelling older people is inconclusive. Further research is needed before firm recommendations can be made concerning the supplementation of vitamin B12 and folate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The prevalence of anaemia in older persons is high (around 10% among people aged ≥65 years) and rises with advancing age [1, 2]. In about one-third of older persons with anaemia co-incidental nutritional deficiencies, such as iron, vitamin B12 and folate deficiency, exist [2]. Among people aged ≥75 years, the prevalence of both vitamin B12 and folate deficiency is >10% [3,4,5,6,7]. These deficiencies are not only associated with macrocytic anaemia but also with dementia, peripheral neuropathy, combined degeneration of the spinal cord and cardiovascular disease [8,9,10,11].

As the prevalence of deficiencies in vitamin B12 and folate are high, screening for deficiencies in vitamin B12 and folate has been recommended as part of a geriatric work-up [12, 13]. Guidelines recommend vitamin B12 supplementation in patients with very low serum vitamin B12 concentrations due to lack of intrinsic factor (IF) (pernicious anaemia) or food-vitamin B12 malabsorption. Several studies have shown significant increases in haemoglobin after vitamin B12 administration in these patients [14,15,16]. Thus, when low levels of vitamin B12 and folate are found, patients are often treated with injections or oral supplements [9, 11, 17].

Interestingly, evidence of an association between a low serum vitamin B12 concentration and anaemia in older individuals in the general population is limited and inconclusive. Data from the Leiden 85-plus study showed that low vitamin B12 concentrations (<150 pmol/L) in 85-year-old persons are not associated with anaemia [18]. Also, the effect of vitamin B12 supplementation on haemoglobin and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) in elderly with low levels of vitamin B12 is unclear [19].

In contrast to vitamin B12 deficiency, folate deficiency seems to be associated with the presence and the development of anaemia in older individuals [18]. Therefore, early detection of folate deficiency may identify older individuals at risk of anaemia. Preventive folic acid supplementation or folic acid fortification of grain and cereal products has been recommended and has already been initiated at population level in several countries. However, to date, it is not known if older persons benefit from prophylactic folic acid supplementation with regards to haemoglobin levels, as no evidence is available to support this assumption.

In order to evaluate the effect of vitamin B12 and folic acid supplementation on haematological parameters in elderly, we executed a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this meta-analysis

We considered all randomised controlled trials (RCTs), where community-dwelling elderly (60+ years) were treated with vitamin B12 or folic acid (all dosages and all forms of administration) and were compared with elderly who were given a placebo. The presence of anaemia or a vitamin B12/folate deficiency was not required for inclusion. Exclusion criteria were: mean or median age less than 60 years, no availability of haemoglobin concentrations or haematocrit at baseline and during follow-up, combinations of vitamin B12 and folic acid supplementation, and specific populations (e.g., studies in diabetes patients or patients with renal failure).

Search strategy

We performed a search on PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Cochrane and CENTRAL with relevant MeSH-headings and title words for vitamin B12 and folic acid for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published between January 1950 and April 2016. Case reports and letters were excluded. We also searched ClinicalTrials.gov for (ongoing) trials on vitamin B12 or folic acid supplementation in older persons. We also used backward and forward citation screening. The electronic search was performed by an information scientist from the Walaeus Library of the Leiden University Medical Center. The exact search strategy can be found in Supplementary File 1.

Selection of studies

All titles and abstracts found in the electronic databases were assessed by the last author. Full copies were acquired of articles that were potentially relevant or in case of uncertainty. WPJdE and LWB appraised these full copies. Disagreement was resolved by consensus. Investigators from each eligible study were invited to join the project and to share their data. The risk of bias of the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment table (see Supplemental File 3).

Data collection

We centrally collected data on demographic characteristics, pre- and post-treatment concentrations of serum vitamin B12, serum/red cell folate, homocysteine, methylmalonic acid, haemoglobin, as well as on levels of haematocrit, mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and red blood cell count (RBC) for all individuals included in the studies. Since vitamin B12 and folate deficiency is defined ideally in terms of serum values of vitamin B12 and folate in combination with homocysteine and methylmalonic acid [8], we also collected data on homocysteine and methylmalonic acid, when available.

Analyses

We combined the results of the individual studies into two meta-analyses; one on the effect of vitamin B12 supplementation and one on the effect of folic acid supplementation on haematological parameters. We performed a two-stage individual participant data meta-analysis. First, for all individual studies separately, we calculated the mean change in haematological parameters between baseline and follow-up (i.e., follow-up minus baseline) in the active treatment group, and in the placebo group (IBM SPSS Statistics 20). Subsequently, we calculated the difference in mean change (together with its standard error) between the active treatment group and placebo group. Then, pooled estimates for each outcome were calculated using a fixed-effects model, using Review Manager version 5.3.3. The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014. We measured statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. An I2 value greater than 50% indicates at least moderate statistical heterogeneity [20].

We performed subgroup analyses for sex and age. Interaction between treatment and sex, and treatment and age, was evaluated by linear regression analysis. Further post hoc analyses were performed in the subgroup of participants with anaemia at baseline, in MCV subgroups, and in studies with a short (≤4 weeks) vs. long duration of treatment (>4 weeks).

Results

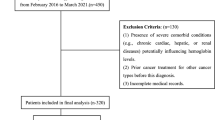

Selection of studies

The electronic search identified 5691 potentially relevant titles and abstracts of papers (performed 25-3-2016). We identified 494 papers, of which 47 fulfilled our inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Investigators from these studies were invited to join the project and to share their data. Eight authors could not provide haematological data because these were not measured or because individual data were not available anymore. Seven authors did not respond to our request [21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. The authors of the other 32 papers (n = 10 for vitamin B12 and n = 22 for folic acid) agreed to participate in this project and to share their data on haemoglobin concentrations or haematocrit fractions after supplementation. These 32 papers comprised 4 unique studies on vitamin B12 supplementation [28,29,30,31] and 3 unique studies on folic acid supplementation (Table 1) [32,33,34]. No additional (ongoing) studies were found on ClinicalTrials.gov. The risk of bias of included studies was low (see Supplemental File 3).

Table 1 describes a summary of the characteristics of the included studies. The sample sizes of the included studies varied from ‘n = 24’ [33] to ‘n = 802’ [32]. Also, the dosage and the forms of administration and the time to follow-up varied to a great extent (Table 1).

Heterogeneity

We found no indications for statistical heterogeneity in the studies on vitamin B12 (I2 = 0%) for all four outcomes, but for the studies on folic acid we found indications for at least moderate statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 72%) when analysing RBC as an outcome. Also, clinical heterogeneity existed between studies due to different methods of administration, dosage of vitamin B12 and folic acid, outcomes and follow-up time. Therefore, we show both the results of the individual studies and the results of the pooled effect estimates (Table 2).

Results of analyses

In Table 2, we show the baseline values of haemoglobin, vitamin B12 and folate. The number of individuals with anaemia was relatively small. None of the individual studies showed a significant effect of vitamin B12 (total n = 343) or folic acid supplementation (total n = 929) on changes in haematological parameters, except for the study by Ntaios on RBC (Table 3). The pooled estimate of the effect on haemoglobin was 0.00 g/dL (95% CI: −0.19;0.18) for vitamin B12 supplementation and −0.09 g/dL (95% CI: −0.19;0.01) for folic acid supplementation, meaning that there was no difference in the mean change in haemoglobin concentrations during follow-up between vitamin B12 and placebo, and folic acid and placebo.

In addition, no differences in the mean change in other haematological parameters were observed. For vitamin B12 supplementation, the pooled estimate of the effect was 0.00 g/dL (95% CI: −0;0.01) for haematocrit, 0.07 g/dL (95% CI: −0.58;0.72) for MCV and 0.00 g/dL (95% CI: −0.06;0.06) for RBC. For folic acid supplementation, the pooled estimate of effect was 0.00 g/dL (95% CI: −0.01;0) for haematocrit, −0.37 g/dL (95% CI: −0.82;0.08) for MCV and −0.02 g/dL (95% CI: −0.05;0.02) for RBC.

Subgroup analyses

In none of the subgroups on sex and age, a significant effect of vitamin B12 or folic acid supplementation on haemoglobin concentrations was found (Table 4). The effect of vitamin B12 and folic acid on haemoglobin was the same for men and women (Pinteraction = 0.577 for vitamin B12 and Pinteraction = 0.545 for folic acid) or between different age groups (Pinteraction = 0.793 for vitamin B12 and Pinteraction = 0.836 for folic acid). Similar results were found when we repeated the analyses for haematocrit, MCV and RBC (data not shown).

Post hoc analyses

When we repeated the analyses in participants with anaemia, we did not observe differences in the change in haemoglobin levels between those who were treated with vitamin B12 and those treated with placebo (Table 4). In those treated with folic acid, a significantly larger decline in haemoglobin levels was observed (Table 4). Moreover, when we stratified on MCV (<80, 80–100 and >100 fL), in none of the subgroups we observed an effect of vitamin B12 or folic acid administration on haemoglobin. In addition, no effect on haemoglobin was found in studies with treatment duration of ≤4 weeks or in studies with a treatment duration of >4 weeks, both with vitamin B12 and folic acid (Table 4).

Results from studies without individual participant data

Of the seven studies that could not be included because of a lack of response from the authors, four studies did not report having measured haemoglobin and/or haematocrit levels. We here discuss the three studies that reported having measured haemoglobin and/or haematocrit levels but of which we did not retrieve data (see Supplemental File 2).

The first study, by Smidt et al., measured haemoglobin and haematocrit at baseline [25], but did not report haematological data at follow-up. The second study, by Hughes et al., measured haemoglobin at baseline and at follow-up [26]. In their study, 93 men and 132 women were given intramuscular hydroxocobalamin (1000 µg.), twice in the first week and then at weekly intervals for a further 4 weeks. During their study, there was a small fall in haemoglobin level, but the difference between the mean changes in those given B12 and those given placebo was small and not statistically significant (0.01 ± 0.35 g.). In the third study by Rampersaud et al. in 33 healthy, postmenopausal women aged 60–85 years, treatment groups received two different folate repletion intakes (i.e., ≈200 and ≈400 µg folate/d) [23]. In this study, haematocrit values did not change significantly over the 14-week study period.

Discussion

In this individual participant data meta-analysis, we did not observe any significant measurable change in routine haematological parameters after treatment with vitamin B12 or folic acid in older persons with either normal or vitamin B12 or folate concentrations below the reference range.

There are several possible explanations for the lack of effect. First, some studies consisted mostly of participants without vitamin B12 or folate deficiency or just below the cutoff values. As these participants may not have had a true tissue deficiency of vitamin B12 or folate, this may have diluted the effect of supplementation. Second, many of the included studies mainly consisted of participants without anaemia. Perhaps haemoglobin levels in non-anaemic patients are less likely to increase in response to vitamin B12 or folic acid treatment than haemoglobin levels in anaemic patients [29]. Unfortunately, the low numbers of people with anaemia refrained us from drawing definite conclusions on the effects of supplementation in an anaemic population with low vitamin B12 or folate concentrations. Third, a low vitamin B12 or folate concentration alone may not be the only reason to develop anaemia, and treatment of these low levels may not be sufficient to raise haemoglobin levels. Other genetic or environmental factors may be involved in the onset of anaemia [19]. Also, other causes such as chronic inflammation may play a role in the development of anaemia [35].

Macrocytic anaemia is one of the most well-known consequences of vitamin B12 and folate deficiency. An elevated mean corpuscular volume (MCV) is often seen as an indication to test for the presence of vitamin B12 or folate deficiency. However, both the sensitivity and the specificity of a high MCV for these deficiencies are low [10, 36]. In our study, we did not observe an effect of vitamin B12 and folic administration on the change in MCV. Also, we did not observe an effect of vitamin B12 or folic acid on haemoglobin in the MCV subcategories. We have to be cautious in interpreting these results as the groups are small and the heterogeneity between studies is large. However, these results are in line with previous analyses in the Leiden 85-plus study, where no relationship was found between vitamin B12 or folate deficiency and changes in MCV over time [18].

This review has some weaknesses. First, there was substantial clinical heterogeneity between studies, due to differences in methods of administration, dose of vitamin B12 and folic acid, outcome measures, treatment follow-up time and sample size, so the results of the meta-analysis have to be interpreted with caution. However, the fact that the results of the individual studies point in the same direction is reassuring. Second, in the post hoc analyses in the subgroup with anaemia, we observed a significantly larger decline in haemoglobin levels in those treated with folic acid. This unexpected finding may perhaps be explained by random error due to multiple testing and the low number of participants this subgroup. Third, we cannot exclude the possibility of bias as not all studies that were identified in our systematic search of the literature could be included, because some authors did not respond to our request or individual participant data were no longer available. However, these studies confirm our findings as they also did not observe significant changes in haemoglobin or haematocrit levels [23, 25, 26].

Conclusions

We did not observe any significant change in routine haematological parameters after treatment with vitamin B12 or folic acid in older persons with either normal vitamin B12 or folate concentrations, or concentrations of vitamin B12 or folate below the reference range. However, we cannot draw firm conclusions because the amount of studies was low, relatively few individuals with anaemia could be included, and the clinical heterogeneity between studies was substantial. Furthermore, we cannot draw conclusions on other benefits of supplementation of vitamin B12 or folate other than haematological outcomes.

Further, well-designed large studies are required to determine whether vitamin B12 and folic acid supplementation are beneficial for older patients with low vitamin B12 or folate concentrations and anaemia or prophylactic effects of these supplements.

References

Beghe C, Wilson A, Ershler WB. Prevalence and outcomes of anemia in geriatrics: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Med. 2004;116:3S–10S.

Guralnik JM, Eisenstaedt RS, Ferrucci L, Klein HG, Woodman RC. Prevalence of anemia in persons 65 years and older in the United States: evidence for a high rate of unexplained anemia. Blood. 2004;104:2263–8.

Clarke R, Grimley EJ, Schneede J, Nexo E, Bates C, Fletcher A, et al. Vitamin B12 and folate deficiency in later life. Age Ageing. 2004;33:34–41.

Flood VM, Smith WT, Webb KL, Rochtchina E, Anderson VE, Mitchell P. Prevalence of low serum folate and vitamin B12 in an older Australian population. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2006;30:38–41.

Lindenbaum J, Rosenberg IH, Wilson PW, Stabler SP, Allen RH. Prevalence of cobalamin deficiency in the Framingham elderly population. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;60:2–11.

Pennypacker LC, Allen RH, Kelly JP, Matthews LM, Grigsby J, Kaye K, et al. High prevalence of cobalamin deficiency in elderly outpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:1197–204.

Wahlin A, Backman L, Hultdin J, Adolfsson R, Nilsson LG. Reference values for serum levels of vitamin B12 and folic acid in a population-based sample of adults between 35 and 80 years of age. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:505–11.

Andres E, Loukili NH, Noel E, Kaltenbach G, Abdelgheni MB, Perrin AE, et al. Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency in elderly patients. CMAJ. 2004;171:251–9.

Hoffbrand A. Megaloblastic anemias. In: Longo D, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, editors. Harrison’s principles of internam medicine. 18 ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

Snow CF. Laboratory diagnosis of vitamin B12 and folate deficiency: a guide for the primary care physician. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1289–98.

Wolters M, Strohle A, Hahn A. Cobalamin: a critical vitamin in the elderly. Prev Med. 2004;39:1256–66.

Clarke R, Refsum H, Birks J, Evans JG, Johnston C, Sherliker P, et al. Screening for vitamin B-12 and folate deficiency in older persons. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:1241–7.

Stabler SP. Screening the older population for cobalamin (vitamin B12) deficiency. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:1290–7.

Vidal-Alaball J, Butler CC, Cannings-John R, Goringe A, Hood K, McCaddon A, et al. Oral vitamin B12 versus intramuscular vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;CD004655.

Mooney FS, Heathcote JG. Oral treatment of pernicious anaemia: first fifty cases. Br Med J. 1966;1:1149–51.

Andres E, Kaltenbach G, Noel E, Noblet-Dick M, Perrin AE, Vogel T, et al. Efficacy of short-term oral cobalamin therapy for the treatment of cobalamin deficiencies related to food-cobalamin malabsorption: a study of 30 patients. Clin Lab Haematol. 2003;25:161–6.

Kolnaar BGM, Pijnenborg L, Van Wijk MAM, Assendelft WJJ, Gans ROB. The standard ‘anemia’ of the Dutch College of General Practitioners. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2003;147:2193–4.

den Elzen WP, Westendorp RG, Frolich M, de RW, Assendelft WJ, Gussekloo J. Vitamin B12 and folate and the risk of anemia in old age: the Leiden 85-Plus Study. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2238–44.

den Elzen WP, van der Weele GM, Gussekloo J, Westendorp RG, Assendelft WJ. Subnormal vitamin B12 concentrations and anaemia in older people: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2010;10:42.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J. 2003;327:557–60.

Bryan J, Calvaresi E, Hughes D. Short-term folate, vitamin B-12 or vitamin B-6 supplementation slightly affects memory performance but not mood in women of various ages. J Nutr. 2002;132:1345–56.

Rydlewicz A, Simpson JA, Taylor RJ, Bond CM, Golden MH. The effect of folic acid supplementation on plasma homocysteine in an elderly population. QJM. 2002;95:27–35.

Rampersaud GC, Kauwell GP, Hutson AD, Cerda JJ, Bailey LB. Genomic DNA methylation decreases in response to moderate folate depletion in elderly women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:998–1003.

Keane EM, O’Broin S, Kelleher B, Coakley D, Walsh JB. Use of folic acid-fortified milk in the elderly population. Gerontology. 1998;44:336–9.

Smidt LJ, Cremin FM, Grivetti LE, Clifford AJ. Influence of folate status and polyphenol intake on thiamin status of Irish women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;52:1077–82.

Hughes D, Elwood PC, Shinton NK, Wrighton RJ. Clinical trial of the effect of vitamin B12 in elderly subjects with low serum B12 levels. Br Med J. 1970;1:458–60.

Garcia A, Pulman K, Zanibbi K, Day A, Galaraneau L, Freedman M. Cobalamin reduces homocysteine in older adults on folic acid-fortified diet: a pilot, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1410–2.

Dangour AD, Allen E, Clarke R, Elbourne D, Fletcher AE, Letley L, et al. Effects of vitamin B-12 supplementation on neurologic and cognitive function in older people: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102:639–47.

Favrat B, Vaucher P, Herzig L, Burnand B, Ali G, Boulat O, et al. Oral vitamin B12 for patients suspected of subtle cobalamin deficiency: a multicentre pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:2.

Hvas AM, Ellegaard J, Nexo E. Vitamin B12 treatment normalizes metabolic markers but has limited clinical effect: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Clin Chem. 2001;47:1396–404.

Seal EC, Metz J, Flicker L, Melny J. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of oral vitamin B12 supplementation in older patients with subnormal or borderline serum vitamin B12 concentrations. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:146–51.

Durga J, Bots ML, Schouten EG, Grobbee DE, Kok FJ, Verhoef P. Effect of 3 y of folic acid supplementation on the progression of carotid intima-media thickness and carotid arterial stiffness in older adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:941–9.

Pathansali R, Mangoni AA, Creagh-Brown B, Lan ZC, Ngow GL, Yuan XF, et al. Effects of folic acid supplementation on psychomotor performance and hemorheology in healthy elderly subjects. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2006;43:127–37.

Ntaios G, Savopoulos C, Karamitsos D, Economou I, Destanis E, Chryssogonidis I, et al. The effect of folic acid supplementation on carotid intima-media thickness in patients with cardiovascular risk: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Int J Cardiol. 2010;143:16–9.

Nemeth E, Ganz T. Anemia of inflammation. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2014;28:671–81.

Oosterhuis WP, Niessen RW, Bossuyt PM, Sanders GT, Sturk A. Diagnostic value of the mean corpuscular volume in the detection of vitamin B12 deficiency. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2000;60:9–18.

Acknowledgements

We thank Anne-Mette Hvas and Ebba Nexo for sharing study data for this project. We thank Jan Schoones from the Walaeus Library of the Leiden University Medical Center for constructing and performing the electronic search strategies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smelt, A.F., Gussekloo, J., Bermingham, L.W. et al. The effect of vitamin B12 and folic acid supplementation on routine haematological parameters in older people: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr 72, 785–795 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-018-0118-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-018-0118-x

This article is cited by

-

Vitamin B12 is associated negatively with anemia in older Chinese adults with a low dietary diversity level: evidence from the Healthy Ageing and Biomarkers Cohort Study (HABCS)

BMC Geriatrics (2024)

-

The effects of single and a combination of determinants of anaemia in the very old: results from the TULIPS consortium

BMC Geriatrics (2021)

-

No association between subnormal serum vitamin B12 and anemia in older nursing home patients

European Geriatric Medicine (2020)