Abstract

Background/Objectives

Reduced food intake is a key aetiological factor of malnutrition. The study purpose was to validate the ingesta Verbal Analogue Scale (ingesta-VAS), a promising tool for rapid food intake assessment, in older adults with cancer in whom malnutrition is frequent and affects treatment outcomes and survival.

Subjects/Methods

This prospective study focused on ≥70-year-old patients with a diet history undergoing their first oncological treatment at a French cancer centre. Exclusion criteria included surgery, oral intake cessation, or artificial nutrition use. Dietitians evaluated nutritional status, daily energy intake, and used the ingesta-VAS and Mini-Nutritional Assessment-Short Form (MNA-SF). The ingesta-VAS validity, sensitivity, specificity, and prognostic impact were assessed using daily food intake as primary criterion, then <25 kcal/kg/day as reference standard for inadequate energy intake. The Area Under the Curve was used to select the cut-off. Overall survival was assessed with the Kaplan-Meier analysis.

Results

The analysis involved 441 participants. The correlation between ingesta-VAS scores and energy intake was strong (\(\rho\) = 0.71), and moderate with the MNA-SF scores (\(\rho\) = 0.55, p < .001). Its sensitivity and specificity for detecting inadequate energy intake was 79.0% and 72.6%, respectively. Combined with performance status and body mass index, ingesta-VAS significantly predicted the inadequate energy intake (odds ratio: 10.2, p < 0.001). Difference in overall survival groups was significant with the cut-off of ≤7 [HR = 1.60 (95% CI: 1.29–1.98), p < 0.001].

Conclusions

The ingesta-VAS exhibits reliable metrological properties and may serve as an early, non-invasive, and simple tool to screen reduced food intake in older adults with cancer for detecting the risk of malnutrition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

More than 60% of patients with cancer are aged 65 years or more [1] and their number in the world will rise from 10.6 million in 2022 to 20.5 million in 2045 [2]. Despite significant advances in supportive cancer care [3, 4], the prevalence of malnutrition remains very high in this population, from 31.9 to 57.5% [1, 5, 6]. Malnutrition in older patients with cancer increases morbidity, disability and mortality [1, 7, 8]. Recently, the clinical nutrition community (Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition, GLIM) reached the agreement that reduced food intake is a well-established aetiologic criterion for malnutrition, with a strong validity [9, 10]. Previous studies highlighted variations in the mechanisms of food intake and unexplained weight loss (WL) between older and younger subjects [5, 11]. These studies suggest that aging may contribute to a diminished capacity to regulate food intake, potentially leading to poor appetite and anorexia, commonly linked to malnutrition. In cancer, reduced food intake and involuntary WL are closely related to anorexia, but also to skeletal muscle wasting, sarcopenia, cachexia and inflammation [10, 12]. Moreover, older patients with cancer who are malnourished are 2.5 times more likely to have major depression and 3.8 times more likely to exhibit frailty, compared with patients without malnutrition [13]. Thus, earlier food intake screening and appropriate nutrition support should be implemented in this population to improve the cancer treatment efficacy [14] and their health-related quality of life [1, 5].

To collect data on ingesta (i.e., solid and liquid substances taken into the body as nourishment during a period, including both food and drinks) and/or energy intake, clinicians often rely on a diet history spanning multiple days [15]. However, this method has drawbacks. It demands the self-completion of dietary records/recalls over 3–7 days, consuming considerable time, effort and expense [16]. Thibault et al. [17] showed the potential usefulness of a 10-point ingesta analogue scale to estimate the dietary intake in 114 participants. In line with their study, Senesse and coworkers validated an ingesta Visual Analogue Scale (ingesta-VAS) by assessing food intake in 1762 adults treated for cancer [18]. The tool consists simply in asking patients to rate how much they currently eat compared with their usual eating habits. In their study, the feasibility of using the ingesta-VAS in its verbal form was very high (̴95%) compared with the visual one (̴5%) [18]. However, older adults with cancer may have different treatment goals, preferences, and tolerances compared with younger patients. Moreover, physicians tend to overestimate food intake, particularly in older patients with cancer [5]. Among the older participants of this study, 62% of physicians, compared to 53% of patients, assessed food intake as being nearly normal, using the ingesta-VAS. Therefore, tools need to be validated in the specific population to collect reliable and accurate information that will guide clinical decision-making and research [19]. The aim of this study was to ensure that the ingesta-VAS is a valid, reliable, accurate and age-appropriate assessment tool of food intake in onco-geriatrics.

Materials and methods

Population

The study was part of a large, prospective population-based investigation on the patients’ nutritional status conducted at a comprehensive cancer centre in France from January 2009 to December 2011 [4, 18]. Patients were eligible for inclusion in the present prospective study if they came for their first hospitalization at the centre to initiate their first oncology treatment, were at least 70 years old, had data on diet history and current body weight, and ingesta-VAS score. Patients were excluded if they were hospitalized for surgery, had stopped oral intake or received artificial nutrition.

Methods

The ingesta verbal analogue scale

The ingesta-VAS [18] was used to assess consumed foods and drinks intake (i.e.,“ingesta”). The cheap and easy-to-use verbal form required patients to rate their current quantity of ingesta compared with usual, using the instruction: “If you consider that when you are in good health, you usually eat 10 out of 10, how much do you currently eat on a scale from 0 to 10?”. 0 would mean eating ‘Nothing at all’ and 10 ‘Eating as usual’”. In case of difficulty with the oral question, the visual form consisted of a line traced on a paper to answer the inquiry, with “I eat nothing at all” (on the left extremity, at 0), “I eat half the usual amount” (in the middle, at 5) and “I eat as usual” (on the right extremity, at 10). In a general population with cancer (mean age of 61.7 years, ranging from 15 to 96 years) [18], the level of correlation was strong positive (\(\rho\) = 0.67, p < 0.05) between the scores on the ingesta-VAS and the energy intake, calculated by a dietitian from a 24 h recall diet history. Using a cut-off of ≤7, the ingesta-VAS exhibited a good discriminatory power to identify patients consuming less than 25 kcal/kg/day, an energy level that is not enough to maintain a stable weight in individuals with cancer [3, 9]. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) was 0.804. The sensitivity to detect patients with an inadequate energy intake, positive predictive value (PPV), specificity and negative predictive value (NPV) were 80.8%, 83.6%, 67.5%, and 63.3%, respectively [18].

Daily energy intake

The dietary history for energy intake calculation was based on a 24 h recall, focusing on the day prior to hospitalization, collected by an experienced dietitian during a detailed 20 min interview. The interview explored how food was prepared, the specific ingredients used in mixed dishes, and the brand names of commercial products. Food quantities were estimated using common container sizes and standard measuring cups and spoons. Then, the dietitian calculated the energy intake using the French food composition tables (measured in kcal/kg/day), edited by the French ‘Centre d’Information sur la Qualité des Aliments’ (CIQUAL, Maisons-Alfort, France), which are managed by the National Agency of Food, Environmental and occupational Health Safety [20].

The mini-nutritional assessment-short form

The validated Mini-Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA®-SF) [21] is one of the most common and recommended tools in geriatric oncology to assess the nutritional status, predict outcomes, and guide interventions [6, 22]. It includes the six items from the full MNA® that exhibited the best sensitivity. It allows identifying three nutritional categories: ‘well-nourished’ (12–14 points), ‘at risk of malnutrition’ (8–11 points), and ‘malnourished’ (0–7 points). The full MNA is used only if a patient is classified as at risk (MNA-SF < 11) [21, 23].

Procedure

In line with the management of cancer cachexia and guidelines at our cancer centre, five dietitians assessed the patients’ nutritional status [4]. They used the ingesta-VAS in its verbal form (or the visual form in case of misunderstanding) and the MNA®-SF. They also collected data on age, sex, type of cancer, current weight and WL in the last month and the last 6 months, height, body mass index (BMI), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG-PS), C-reactive protein (CRP), ingesta-VAS score, then, daily energy intake.

Statistical considerations

Categorical variables were reported using contingency tables. For continuous variables, the median and range were calculated. To investigate their associations with the clinical and pathologic parameters, univariate statistical analyses were performed using the Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test and the Kruskal-Wallis or Student’s t test. The Spearman correlation coefficient (\(\rho\)) was used to determine the relationship between quantitative assessments. The tool feasibility was reported, as in the first study [18], by comparing the use of the verbal versus visual form, but also, calculating the proportion of patients having completed the ingesta-VAS score at the last selection criterion of the sample. Different criteria were used as reference methods to determine the external validity of the ingesta-VAS with the daily energy intake as primary criterion. The Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUROC) curves were used with the daily energy intake as reference standard (<25 kcal/kg/day identified patients with inadequate energy intake). The cut-off value corresponding to the highest predictive value was chosen, maximizing the Youden index [24]. Complementary analyses were conducted in two separate data sets for establishing the VAS cut-off: a derivation training set and a validation set, with a sensible ratio of 80:20% of the entire sample [25]. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and overall agreement [(number of true positives + number of true negatives)/n] was calculated using this cut-off value.

Multivariable analyses were carried out on the entire sample using logistic regressions or Cox’s proportional hazards regressions, with a stepwise selection procedure, to investigate known predictive or prognostics factors respectively. Odds ratio (OR) and hazard ratios (HR) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) were used to display risk reductions. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the date of the first hospitalization for the first oncology treatment to the date of death from any cause. The date of death was extracted from the death certificate or obtained by a phone call to the caregivers. Medians were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method and presented with their 95% CI. All pvalues were two sided and the significance level was set at 5% (p < 0.05). Statistical analyses were performed using the STATA© 16.1 software.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the samples

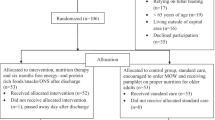

Over 3 years, 454 older inpatients, eligible for inclusion based on the main inclusion criteria, were referred to the centre to initiate an oncological treatment (Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy-STARD diagram [26] in Fig. 1). Among them, 441 participants had completed the ingesta-VAS score, reaching a feasibility of 97.1% in this population. Characteristics of the final selected 441 patients are in Table 1. Their median age was 76 years (range: 70–96), and 51.0% (n = 225) were women. The most frequent primary cancer sites were the gastrointestinal tract (30.9%, n = 133), urological tract (20.7%, n = 89), and breasts (14.9%, n = 64). Metastatic disease concerned 72.3% of patients (n = 319). The median CRP concentration was 29.8 mg/L (range: 0–293). The median ingesta-VAS score was 6 (range: 1–10) and 65.8% of patients (n = 290) had a score ≤7. The ECOG-PS score was 3 or 4 in 24.5% of patients (n = 108). Based on the MNA-SF score, 92.9% (n = 378) of participants were not normally nourished (range: 1-11). The ingesta-VAS feasibility was 97.1% in its verbal form (vs. visual for 2.9% of the patients). More than 60% of patients required professional assistance to complete the MNA-SF. In 68.3% of patients (n = 301), a WL of 5% or more was observed, compared with their usual weight. Moreover, 74.4% of patients (n = 328) ingested less than 25 kcal/kg/day.

For the complementary analyses, a derivation dataset including 341 patients, and a validation dataset with 100 patients, were considered, closed to a ratio of 80/20% of the entire sample. Clinical and nutritional characteristics did not statistically differ (p > .05) between sets, as detailed in Supplementary Table 1.

Construct and content validity

The ingesta-VAS accuracy was explored using the dietary intake as primary criterion; the correlation coefficient with the mean energy intake was significantly positive (Fig. 2A): \(\rho\) = 0.71, p < 0.001.

The ingesta-VAS score cut-off of ≤7 corresponded to the highest predictive value to detect inadequate energy intake (i.e., ingesting <25 kcal/kg/day) using the entire sample’s ROC and maximizing the Youden index. The AUROC was 0.81, p < 0.001 (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1), and sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were 79.0% (95% CI: 75.2–82.8), 72.6% (95% CI: 68.4–76.7), 89.3% (95% CI: 86.4–92.2), and 54.3%, (95% CI: 49.7–59.0), respectively. The overall agreement was 77.3% (95% CIs: 73.4–81.2). The complementary analyses on the derivation and the validation samples were consistent. The cut-off of ≤7 was the highest predictive value on the ROC in both samples to detect inadequate energy intake. The AUROC were 0.81 (95% CI: 0.76–0.86) and 0.84 (95% CI: 0.75–0.93), respectively (see Supplementary Fig. 2).

Lastly, the multivariable logistic regression (see Supplementary Table 2) showed that inadequate energy intake was predicted by ingesta-VAS score ≤7 (OR = 10.2, p < .001), ECOG-PS of 2 (OR = 2.4, p = 0.002), ECOG-PS of 3–4 (OR = 2.7, p = 0.004, and BMI ≤ 22 kg/m2 OR = 0.2, p < 0.001.

Convergent validity

Convergent validity was explored by comparing the ingesta-VAS and MNA-SF scores. Their correlation coefficient was significant and positive: \({\boldsymbol{\rho }}\) = 0.55, p < .001 (Fig. 2B). Moreover (Table 2), the ingesta-VAS score cut-off of ≤7 accurately detected 85.7% of patients who had a MNA-SF score between 0 to 7 (i.e., ‘malnourished’ category). It also accurately categorized 86.2% of patients with ‘normal nutrition status’ (MNA-SF score between 12 and 14).

Convergent validity was then explored by comparing the ingesta-VAS score and WL (Table 2). The ingesta-VAS score cut-off of ≤7 detected accurately 72.4% (95% CI: 68.3–76.6) of patients with WL ≥ 5%. Its specificity, PPV, NPV, and overall agreement were 48.6% (95% CI: 43.9–53.2), 75.2% (95% CI: 71.1–79.2), 45.0% (95% CI: 40.4-49.7), and 64.9% (95% CI: 60.4–69.3), respectively.

Lastly, the ingesta-VAS and CRP concentration were explored using the cut-off of ≤7, showing a sensitivity of 77.8% (95% CI: 72–81.5), a specificity of 47.4% (95% CI: 43.3–54.5), a PPV of 76.7% (95% CI: 73.2–82.5), a NPV of 48.9% (95% CI: 41.8–53) (Table 2).

Prognostic impact

The median follow-up was 28.8 months [95% CI: 26.5–38.4], ranging from 0 to 44.7 months. At the follow-up end, 364 patients were dead (82.5%). The median OS was 8.05 months (95% CI: 6.6–9.2). The 1-year and 2-year OS rates were 37.9% (95% CI: 33.2-42.5) and 19.4% (95% CI: 15.6–23.5), respectively. The median OS was 6.2 months (95%CI: 4.9–7.7) in patients with an ingesta-VAS score ≤7 and 13.5 months (95% CI: 8.7–16.6) in patients with a score >7 [HR = 1.60 (95% CI: 1.29–1.98)], p < 0.001 (Fig. 3). The multivariable analysis (Table 3) showed that in this sample, high ECOG-PS score ( > 1), WL ≥ 5%, and metastatic disease predicted a worse OS.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study validating the ingesta-VAS as a tool for assessing dietary intake in a specific and large sample of older patients with cancer. As data collection was undertaken from 2009 to 2011, the selection of patients was restrictive. Analysis focused on the first hospitalization scheduled for an oncology treatment (i.e., before interfering nutritional interventions), limiting the bias of changing dietary patterns. The ingesta-VAS feasibility was very high (97.1%) among older patients with cancer, as well as its feasibility in a verbal form (97.1%) in the final sample. The tool validity was confirmed by the strong and positive correlation (\(\rho\) = 0.71) with the energy intake calculated from 24 h dietary recall data. After haven taken several methodological precautions to ensure the validity of a cut-off of ≤7, the ingesta-VAS discrimination power was very good (AUC = 0.814) to identify patients with inadequate energy intake. The tool exhibited good sensitivity and specificity (79.0% and 72.6%, respectively), and a good concordance between the two measures (77.3%). The median OS was 7.3 months longer in patients with an ingesta-VAS score >7.

Reduced food intake is a well-established aetiologic criterion of malnutrition, according to the GLIM definition of 2018 [9]. Older adults with cancer often have multiple comorbidities, require polypharmacy and may have nutritional issues [22, 27]. Those with frailty, functional limitations, abnormal gait speed, neurocognitive impairments, major depression, or bad ECOG-PS are more likely to experience malnutrition compared with other patients [1, 13]. In our sample, ̴ 65% of patients reported a poor food intake compared with usually (ingesta-VAS score ≤7), and ̴ 75% of patients ingested <25 kcal/kg/day, which is not enough to maintain a stable weight. This high percentage is in line with previous studies showing that nutritional intake declines with age [28] and in patients with cancer [1]. Furthermore, more than two thirds of participants had a WL ≥ 5%. This cut-off was chosen because it is one of the malnutrition criteria in the standardized definition [5, 29]. The ingesta-VAS showed a sensitivity of 72.4% to detect patients with significant WL and a positive predictive value of 75.2%. This is in line with a recent analysis in a very large cohort (12,253 patients) showing that reduced food intake was the variable with the largest overall contribution to non-volitional WL [10]. As expected, in our study, a low ingesta-VAS score was associated with a low MNA-SF score (e.g., the cut-off of ≤7 accurately detected 85.7% of patients who were categorized as ‘malnourished’ based on the MNA-SF score). Considering that systemic inflammation is present in cachexia when CRP is ≥10 mg/L [30], more than two-third of the participants were significantly concerned. The ingesta-VAS correctly detected 76.7% of these patients. Since inflammation is accepted as one of the important modulators of appetite in cancer patients [10], these results, in addition to the previous ones, strengthen the good convergent validity of the ingesta-VAS in geriatric oncology.

The GLIM working group recommended validating the GLIM-defined malnutrition using the complete version of the MNA, whereas the MNA-SF could be used as a screening tool in the first step of the algorithm [6, 9]. As observed by Lacau St Guily et al. [4], also our population often required professional assistance to fill in the MNA-SF. Moreover, its completion took on average 10 min, as previously reported for >70-year-old individuals [4, 31]. Conversely, the ingesta-VAS was very quick (2 minutes) and easy-to-use, as previously reported [18], with a very high feasibility ( > 97%). The MNA-SF is a screening tool that does not intend to specifically evaluate food intake [31, 32]. This assessment must be performed once the risk has been detected and using more appropriate tools, for example, a 24h-dietary recall, food records or the ingesta-VAS [33]. Lastly, the ingesta-VAS could be an alternative for rapidly and easily exploring one of the aetiologic criteria of malnutrition according to the GLIM consensus. In that way, it may permit resource optimization. Its validation will ensure that healthcare providers and researchers invest their time and resources in tools that are valid and reliable for use in specific populations.

Moreover, physicians often overestimate food intake, particularly in geriatric oncology populations [5, 17]. In a French study, 62% of physicians versus 53% of older patients with cancer estimated that food intake was nearly normal. Using a VAS ranging from 1 (no impact) to 10 (extremely affected), the physicians underestimated the effect of the nutritional status on the patients’ quality of life, particularly on psychology and fatigue (whatever the age) [5]. Similarly, a recent systematic review found that the physicians’ assessments of dysphagia and eating scores did not match those done by the patients [20]. Patients could reliably and accurately self-screen their food intake with the simple ingesta-VAS tool. Reducing the discrepancy in perceptions between physicians and patients of food intake could reduce the risk of late nutritional management in geriatric oncology.

On this other side, the ingesta-VAS was specifically developed to help in screening inadequate nourishment leading to malnutrition. This explains that the tool does not include an “eating more” option, which is less common, but a possible finding. No participant reported to eat more than usually in our sample. In this case, they would not have been recorded as a score of 10/10. They would have been excluded, as this could be an issue as people eating more than usual could be following good advice to consume more (possibly little and often) to meet higher requirements, rather than it representing higher appetite or being in a better state of health or at lower risk of malnutrition.

Our data confirm that older adults with cancer have specific nutritional needs, high rates of involuntary WL, functional limitations, nutritional risk, malnourished status and/or reduced daily energy intake [34]. Validating the ingesta-VAS in this population may be one way to ensure that their specific needs are rapidly identified and addressed and also taken into account during clinical decision-making. Using unvalidated tools may also raise ethical concerns on the robustness and reliability of the collected data and decisions made based on them. In our study, patients with a low BMI had counterintuitively a 0.2 times lower risk of ingesting <25 kcal/kg/day, compared with patients with a BMI > 22. Two explanations can be suggested: (1) these body compositions usually do not need 25 kcal/kg/day to be stable, or (2) these patients were already slightly engaged in changing dietary patterns compared with patients who are usually not concerned by their BMI. More interestingly, patients with an ingesta-VAS score ≤7 had a 10.2 times higher nutritional risk. In the Martin et al. study [10], reduced food intake was significantly associated with WL and predicted OS. Similarly, a recent meta-analysis concluded that food intake measurements predicted mortality and should be included in the clinical enquiry in geriatric oncology [35]. In our study, the ingesta-VAS score was a predictive prognostic factor: OS was much shorter in patients with a score ≤7 (6.2 vs.13.5 months). However, in multivariable analysis, only ECOG-PS, WL and presence of metastases independently predicted OS. This points to food intake being dependent on the other parameters in our “small” sample, whereas in a previous impressive sample (N = 9952 patients), moderately and severely reduced food intake and CRP independently predicted OS [10]. In line with the GLIM, non-volitional WL remains a phenotypic criterion for malnutrition, whereas reduced food intake is an aetiologic factor. The next step would be the early and systematic use of the ingesta-VAS, not only by nutritionists and dietitians, but also by all supportive care providers.

Following the clinical nutrition guidelines of the French Speaking Society of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism for adults undergoing non-surgical anticancer treatment in 2012 [36] and 2014 [37], and supported by later major publications [18, 38], nutritional management has changed in all the French comprehensive cancer centres [4]. Nutritional assessment is now required at each visit (outpatients) or hospitalization (inpatients). Actually, the ingesta-VAS is systematically suggested to be used as a screening tool, as well as WL, both integrated into the oncological treatment plan. Patients should be defined at risk of malnutrition if the result of the ingesta-VAS is lower than 8. Most often, this is the first step towards malnutrition. A score [0-2] on the ingesta-VAS is a criterion of severe risk, alerting to a risk of refeeding syndrome (if its lasts more than 5 days with 2 criteria or more than 10 days alone), and a potential hospitalization if there is an indication for nutrition support as determined by a nutritional expert [39]. The presence of malnutrition is defined by a WL above than 5% compared with usual weight, and/or a BMI (but not used alone) lower than 22 for patients aged 70 and older [10]. If the score is [3,4,5,6,7] on the ingesta-VAS, a specialist expertise from a dietician/nutritionist is recommended, along with the use of oral nutritional supplements. Dietary counselling, and sip feeds, if necessary, are recommended (i.e., parenteral nutrition only in case of unusable or inaccessible small intestine). If the score is >8 on the ingesta-VAS, the risk of eating less than 25 kcal/kg/day is low, reducing the risk of WL. However, malnutrition could not formally be excluded, as the negative predictive value of the ingesta-VAS was low (only 54.3%) in our sample of older patients. Others important clinical data should be examined if available, such as WL and some modulators of appetite, such as inflammation. The supplementary Fig. 3 sums up the strategies.

There are limitations to the current study. First, the ingesta-VAS remains a qualitative tool for screening reduced food intake and cannot replace the quantitative assessment by a nutritional professional [17, 18] (e.g., determining energy and protein intake). Second, data about its reproducibility, test-retest reliability and sensitivity to change are lacking. Also, the ingesta-VAS convergent validity could have been cross-referenced with other convergent tools (e.g., Patient Generated Subjective Global Assessment [40]). No cross-validation between the two forms could be performed, as the use of verbal form was overwhelming (>97%) compared to the visual one. Although this did not lead to any significant bias in our results, it remains an option to be explored in the future. Then, age, cancer type and cancer treatment could negatively affect neurocognition, especially in adults with pre-existing impairment [41, 42]. The presence of significant neurocognitive deficits was not included in the eligibility/exclusion criteria, and may have influenced the self-assessments. It could have been useful to collect dietary information also from the patient’s caregiver. Lastly, cost-effectiveness should be studied in a contemporary cohort.

Conclusion

Reduced food intake is a well-established aetiologic criterion of malnutrition, which remains an important concern in geriatric oncology. Validating the ingesta-VAS in older adults with cancer was essential to ensure accurate assessment, safe and effective care, and ethical practice in clinical and research settings. This study validated the ingesta-VAS as an early, non-invasive, and simple tool to assess food intake and to screen for reduced dietary intake in geriatric oncology. It may contribute to collect reliable data for the development of evidence-based guidelines and interventions for older adults with cancer. Future research should determine the tool’s test-retest reliability and sensitivity to change.

Data availability

De-identified participant data will be made available upon request. Any requests for trial data and supporting material (data dictionary, protocol, and statistical analysis plan) will be reviewed by the nutritional management group in the first instance. Only requests that have a methodologically sound proposal will be considered. Proposals should be directed to the corresponding author in the first instance; to gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.

References

Zhang X, Pang L, Sharma SV, Li R, Nyitray AG, Edwards BJ. Prevalence and factors associated with malnutrition in older patients with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10:763–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2019.01.021.

World Health Organization. Cancer Tomorrow https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/en/dataviz/isotype?age_start=13&single_unit=500000, (accessed April 25, 2022).2020.

Arends J, Bachmann P, Baracos V, Barthelemy N, Bertz H, Bozzetti F, et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin Nutr. 2016 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2016.07.015.

Senesse P, Isambert A, Janiszewski C, Fiore S, Flori N, Poujol S, et al. Management of Cancer Cachexia and Guidelines Implementation in a Comprehensive Cancer Center: A Physician-Led Cancer Nutrition Program Adapted to the Practices of a Country. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;54:387–393.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.01.010.

Lacau St Guily J, Bouvard É, Raynard B, Goldwasser F, Maget B, Prevost A, et al. NutriCancer: A French observational multicentre cross-sectional study of malnutrition in elderly patients with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2018;9:74–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2017.08.003.

Sobrini P, Sánchez-Castellano C, Cruz-Jentoft AJ. MNA-SF as a screening tool for malnutrition diagnosed with the glim criteria in older persons with cancer. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12:653–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-020-00442-8.

Bourdel-Marchasson I, Blanc-Bisson C, Doussau A, Germain C, Blanc J-F, Dauba J, et al. Nutritional Advice in Older Patients at Risk of Malnutrition during Treatment for Chemotherapy: A Two-Year Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e108687. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0108687.

Presley CJ, Dotan E, Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, Jatoi A, Mohile SG, Won E, et al. Gaps in nutritional research among older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7:281–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2016.04.006.

Cederholm T, Jensen GL, Correia MITD, Gonzalez MC, Fukushima R, Higashiguchi T, et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition – A consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2018.08.002.

Martin L, Muscaritoli M, Bourdel-Marchasson I, Kubrak C, Laird B, Gagnon B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for cancer cachexia: reduced food intake and inflammation predict weight loss and survival in an international, multi-cohort analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2021;12:1189–202. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12756.

Volkert D, Beck AM, Cederholm T, Cruz-Jentoft A, Hooper L, Kiesswetter E, et al. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clin Nutr Edinb Scotl. 2022;41:958–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2022.01.024.

Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, Bosaeus I, Bruera E, Fainsinger RL, et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:489–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70218-7.

Zhang X, Sun M, McKoy JM, Bhulani NNA, Valero V, Barcenas CH, et al. Malnutrition in older patients with cancer: Appraisal of the Mini Nutritional Assessment, weight loss, and body mass index. J Geriatr Oncol. 2018;9:81–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2017.07.012.

Assenat E, Latournerie M, Thézenas S, Gaillet S, Janiszewski C, Flori N, et al. A prospective phase II study evaluating the efficacy of oral immune modulating formulae on acute oral mucositis during radiochemotherapy in head and neck neoplasms. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2011;6:e171–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclnm.2011.03.001.

Kumanyika SK, Mauger D, Mitchell DC, Phillips B, Smiciklas-Wright H, Palmer JR. Relative validity of food frequency questionnaire nutrient estimates in the Black Women’s Health Study. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:111–8.

Shim J-S, Oh K, Kim HC. Dietary assessment methods in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiol Health e2014009. https://doi.org/10.4178/epih/e2014009.2014:

Thibault R, Goujon N, Le Gallic E, Clairand R, Sébille V, Vibert J, et al. Use of 10-point analogue scales to estimate dietary intake: A prospective study in patients nutritionally at-risk. Clin Nutr. 2009;28:134–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2009.01.003.

Guerdoux-Ninot E, Flori N, Janiszewski C, Vaillé A, de Forges H, Raynard B, et al. Assessing dietary intake in accordance with guidelines: Useful correlations with an ingesta-Verbal/Visual Analogue Scale in medical oncology patients. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:1927–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2018.06.974.

Stueger A, Joerger M, De Nys K. Geriatric evaluation methods in oncology and their use in clinical studies: A systematic literature review. J Geriatr Oncol. 2024;15:101684.

Ciqual D. Table de composition nutritionnelle des aliments Ciqual - data.gouv.fr. 2020. https://www.data.gouv.fr/fr/datasets/table-de-composition-nutritionnelle-des-aliments-ciqual/.

Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Ramsch C, Uter W, Guigoz Y, Cederholm T, et al. Validation of the Mini Nutritional Assessment short-form (MNA-SF): a practical tool for identification of nutritional status. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13:782–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-009-0214-7.

Guyonnet S, Rolland Y. Screening for Malnutrition in Older People. Clin Geriatr Med. 2015;31:429–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2015.04.009.

Rubenstein LZ, Harker JO, Salvà A, Guigoz Y, Vellas B. Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M366–372. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.6.m366.

Youden WJ, Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3:32–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::AID-CNCR2820030106>3.0.CO;2-3.

Harrell, FE Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis. Cham: Springer International Publishing;(2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19425-7.

Korevaar, Cohen DA, Reitsma JF, Bruns DE JB, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, et al. Updating standards for reporting diagnostic accuracy: the development of STARD 2015. Res Integr Peer Rev. 2016;1:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-016-0014-7.

Hong X, Yan J, Xu L, Shen S, Zeng X, Chen L. Relationship between nutritional status and frailty in hospitalized older patients. Clin Inter Aging. 2019;ume 14:105–11. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S189040.

Ozer NT, Akin S, Gunes Sahin G, Sahin S. Prevalence of malnutrition diagnosed by the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition and Mini Nutritional Assessment in older adult outpatients and comparison between the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition and Mini Nutritional Assessment energy-protein intake: A cross-sectional study. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2022;46:367–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpen.2123.

Raynaud-Simon A, Revel-Delhom C, Hébuterne X. French Nutrition and Health Program, French Health High Authority. Clinical practice guidelines from the French Health High Authority: nutritional support strategy in protein-energy malnutrition in the elderly. Clin Nutr Edinb Scotl. 2011;30:312–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2010.12.003.

Fearon KC, Voss AC, Hustead DS. Cancer Cachexia Study Group. Definition of cancer cachexia: effect of weight loss, reduced food intake, and systemic inflammation on functional status and prognosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1345–50.

Vellas B, Villars H, Abellan G, Soto ME, Rolland Y, Guigoz Y, et al. OVERVIEW OF THE MNA® – ITS HISTORY AND CHALLENGES. J Nutr. 2006;10:11.

Guigoz Y, Vellas B, Garry PJ. Assessing the Nutritional Status of the Elderly: The Mini Nutritional Assessment as Part of the Geriatric Evaluation. Nutr Rev. 2009;54:S59–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.1996.tb03793.x.

van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MAE, Guaitoli PR, Jansma EP, de Vet HCW. Nutrition screening tools: does one size fit all? A systematic review of screening tools for the hospital setting. Clin Nutr Edinb Scotl. 2014;33:39–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2013.04.008.

Meza-Valderrama D, Marco E, Dávalos-Yerovi V, Muns MD, Tejero-Sánchez M, Duarte E, et al. Sarcopenia, Malnutrition, and Cachexia: Adapting Definitions and Terminology of Nutritional Disorders in Older People with Cancer. Nutrients. 2021;13:761. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030761.

Bullock AF, Greenley SL, McKenzie GAG, Paton LW, Johnson MJ. Relationship between markers of malnutrition and clinical outcomes in older adults with cancer: systematic review, narrative synthesis and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2020;74:1519–35. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-020-0629-0.

Senesse P, Hébuterne X. Nutrition chez le patient adulte atteint de cancer: besoins nutritionnels, énergétiques et protéiques, au cours de la prise en charge du cancer chez l’adulte. Nutr Clin Métabolisme. 2012;26:189–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nupar.2012.10.005.

Senesse P, Bachmann P, Bensadoun R-J, Besnard I, Bourdel-Marchasson I, Bouteloup C, et al. Clinical nutrition guidelines of the French Speaking Society of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (SFNEP): Summary of recommendations for adults undergoing non-surgical anticancer treatment. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:667–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2014.01.160.

Cederholm T, Jensen GL. To create a consensus on malnutrition diagnostic criteria: A report from the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) meeting at the ESPEN Congress 2016. Clin Nutr. 2017;36:7–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2016.12.001.

Stanga Z, Brunner A, Leuenberger M, Grimble RF, Shenkin A, Allison SP, et al. Nutrition in clinical practice—the refeeding syndrome: illustrative cases and guidelines for prevention and treatment. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62:687–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602854.

Detsky A, McLaughlin J, Baker J, Johnston N, Whittaker S, Mendelson R, et al. What is subjective global assessment of nutritional status? JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1987. https://doi.org/10.1177/014860718701100108.

Loh KP, Janelsins MC, Mohile SG, Holmes HM, Hsu T, Inouye SK, et al. Chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment in older patients with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7:270–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2016.04.008.

Magnuson A, Lei L, Gilmore N, Kleckner AS, Lin FV, Ferguson R, et al. Longitudinal Relationship Between Frailty and Cognition in Patients 50 Years and Older with Breast Cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:928–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15934.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the dietitians for their assistance with patient recruitment towards the end of the study and their support in completing the study: Stéphanie Arnac, Bérénice Clavie, Anne Fallières, Sophie Zaessinger, Helga Thoralsdottir and Arnaud Vaille. They thank Elisabetta Andermarcher for editing the manuscript. They also thank Dr. Héloïse Lecornu, Patrice Champoiral and Louise Coutant for helping in the daily supportive care practice, as well as Dr. Laurence Cristol, Dr Blandine Gallay-Suchet and Prof David Azria for their support in geriatric oncology.

Funding

This study was supported by SIRIC Montpellier Cancer (Grant INCa-DGOS-INSERM-ITMO Cancer_18004), which was not involved in study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, and in the decision to submit the article for publication. The supplementary Table 1 was designed freely with the resources from PoweredTemplate.com.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PS, EG and NF contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by NF, CJ, LF and JD. Analysis was performed by ST. The first draft of the manuscript was written by EG; PS revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors commented on previous versions, read and approved the final of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

PS reports, with no competing interests with the submitted work, personal fees from Nestle Health Science Bbraun, Theradial, Mayoly Spindler, Novartis, Fresenius Kabi, Lilly France SAS, Nutricia Nutrition Clinique, Baxter SAS, AgirADom, Andros, HomeAir, Servier, NHC, BMS, Salgen SAS, Sanofi Aventis France, Kephren, Nestlé home care, Experf. NF reports personal fees, outside the submitted work, from Fresenius Kabi, Nestlé Health, BBraun, Viatis and TSC France. ST, CJ, LF and JD declare no competing interests. EG reports personal fees, without competing interests with the submitted work, from AstraZeneca, Nestlé Health, CancerConsult and Sanofi, outside the submitted work. She also reports grants without competing interests from the French National Cancer Institute (Grant INCa_15779 and Grant INCa-DGOS-Inserm_12553) and from the Ligue contre le Cancer (Grant SHS2018 and Grant 2024).

Ethics approval

The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and data were subject to an official declaration to the CNIL, the French Data Protection Authority: methodological reference MR-004. MR-004 is a form of patient informed consent for publication: no non-opposition was declared.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

41430_2025_1681_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 3

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Senesse, P., Deffrennes, J., Flori, N. et al. Screening for reduced food intake in 2 minutes: validation of the ingesta verbal analogue scale in medical geriatric oncology. Eur J Clin Nutr (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-025-01681-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-025-01681-3