Abstract

Atomically-thin van der Waals layered materials, with both high in-plane stiffness and bending flexibility, offer a unique platform for thermomechanical engineering. However, the lack of effective characterization techniques hinders the development of this research topic. Here, we develop a direct experimental method and effective theoretical model to study the mechanical, thermal, and interlayer properties of van der Waals materials. This is accomplished by using a carefully designed WSe2-based heterostructure, where monolayer WSe2 serves as an in-situ strain meter. Combining experimental results and theoretical modelling, we are able to resolve the shear deformation and interlayer shear thermal deformation of each individual layer quantitatively in van der Waals materials. Our approach also provides important interlayer coupling information as well as key thermal parameters. The model can be applied to van der Waals materials with different layer numbers and various boundary conditions for both thermally-induced and mechanically-induced deformations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Triggered by the growing need of developing next-generation semiconductor devices, mechanical engineering has been moved forward from traditional semiconductors to van der Waals (vdW) materials due to their unique layered structures1,2. Through lattice deforming, the electronic structure of vdW materials can be tuned significantly, giving rise to intriguing physical phenomena and applications, such as shear-strain-generated pseudo magnetic fields3, one-dimensional moiré potentials4, confined states in soliton networks5, and actively variable-spectrum optoelectronics6. Mechanical approaches have been widely used to introduce compressive and tensile strain (lattice deformation) in vdW materials, including substrate engineering with nanopillars7,8,9, generating nanobubbles in vdW materials10,11,12,13, bending flexible substrates14,15,16, and utilizing the thermal expansion coefficient (TEC) mismatch between vdW materials and substrates17,18,19. Although much progress has been achieved in the mechanical engineering of vdW materials, investigations on their thermomechanical properties are scarce. Besides, understanding of the micro-mechanism of interlayer deformation when reacting to temperature variation lies at the heart of thermal engineering of vdW materials.

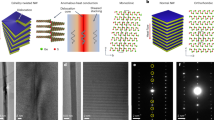

Since vdW materials are always supported by substrates, their thermomechanical properties are considered based on a whole vdW-materials/substrate system. vdW materials and substrates generally possess distinct TEC, leading to distinct intrinsic thermal deformation when temperature changes. Figure 1a shows the schematic diagram of thermal deformation in an N-layer vdW-material/SiO2 system from T0 to T1. Considering the strong clamping effect between SiO2 and vdW materials18, the deformation of the bottom layer (n = 1) is nearly equal to that of SiO2. Yet the top layer (n = N) is almost free from the clamping effect and exhibits intrinsic thermal deformation of vdW materials when N is large enough. In this case, the relaxation from layer to layer through interlayer interaction results in the in-plane lattice deformation difference between adjacent layers. For clarity, we define the shear thermal deformation (STD) τ and interlayer shear thermal deformation (ISTD) Δτ in Fig. 1a. Here, τ is the in-plane lattice deformation induced by temperature variation from T0 (high temperature) to T1 (low temperature) and Δτ is the in-plane lattice deformation difference between adjacent layers. However, owing to the lack of proper characterization technique, precise measurements of STD and ISTD layer by layer in vdW materials have not been reported yet.

a ISTD model of an N-layer phosphorene/SiO2 system when temperature decreases from T0 to T1. b ISTD model of a WSe2/N-layer phosphorene/SiO2 system when temperature decreases from T0 to T1. Here, N is the total layer number of phosphorene. n is the n-th (1 ≤ n ≤ N) phosphorene layer counting from bottom. τ (n) is the STD of the n-th phosphorene and Δτ (n) is the ISTD between the n-th and (n−1)-th phosphorene from T0 to T1.

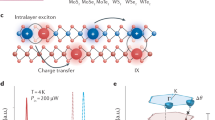

In this work, we choose phosphorene and hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) as the representative experimental subjects due to their exceptional thermal and mechanical properties18,20,21,22. Through monitoring the temperature-dependent photoluminescence (PL) spectra of delicately designed WSe2-based vdW heterostructures, where monolayer WSe2 serves as an in-situ “strain meter”, the mechanical behaviors of vdW materials are reflected conveniently. Taking account of interlayer interactions at both homo- and hetero-interfaces and the Young’s modulus and TEC of phosphorene and WSe2, we establish an effective ISTD model which allows us to access the layer-dependent STD and ISTD in phosphorene. The schematic diagram in Fig. 1b illustrates the thermal deformation reaction of phosphorene and WSe2 layers in the WSe2/phosphorene/SiO2 system from T0 to T1. Through fitting the experimental results, we can extract the interlayer coupling coefficients at phosphorene/phosphorene homo-interface and WSe2/phosphorene hetero-interface. Besides, key thermal parameters of vdW materials, such as TEC, are extracted from the model.

Results

Design of vdW heterostructures for ISTD studies

We choose monolayer WSe2 and phosphorene as building blocks of vdW heterostructures for STD and ISTD investigations for three reasons. First, phosphorene has been predicted to exhibit a large TEC of between 6.3 × 10−6 and 53 × 10−6 K−1 at room temperature23,24,25, which stands out from the family of vdW materials and is at least one order of magnitude larger than that of SiO2 (~0.5 × 10−6 K−1)26,27. Such a large TEC is expected to cause significant thermal deformation and corresponding effect on the physical properties of phosphorene and its adjacent 2D materials. Second, monolayer WSe2 is a flexible direct-bandgap semiconductor with very high luminescence efficiency28. Its strain-sensitive optical and electronic properties have been widely investigated16,17,28,29,30. Thus, we can use monolayer WSe2 as a convenient sensing layer to monitor the thermal deformation of phosphorene as illustrated in Fig. 2a. Third, phosphorene and WSe2 show strong coupling at their interface, which could enable efficient strain transfer from phosphorene to WSe2 through interlayer interactions (Fig. 2a)31.

a Monolayer WSe2 serves as a strain meter to probe the thermal deformation of the top phosphorene layer. Here, the blue arrows indicate that the in-plane lattice contraction when temperature decreases. The green arrows describe the strain transfer from phosphorene to WSe2 through interlayer interactions. b Schematic evolution trends of photon energy in WSe2/phosphorene/SiO2 and WSe2/SiO2 systems as a function of temperature. Photon energy difference (ΔE) between WSe2/phosphorene/SiO2 and WSe2/SiO2 at temperature T can directly reflect the thermal deformation of WSe2. c Optical image of a WSe2/phosphorene heterostructure. The scale bar is 5 μm. d Raman spectra of isolated monolayer WSe2, isolated phosphorene, and WSe2/phosphorene heterostructure at room temperature. e Photoluminescence (PL) spectra of isolated monolayer WSe2 and WSe2/phosphorene heterostructure at 180 K. Here, Xloc, Xtrion and X denotes the localized, charged and neutral exciton of monolayer WSe2, respectively.

To quantitatively investigate the STD and ISTD of phosphorene, we monitor the temperature-dependent PL photon energy of WSe2/phosphorene/SiO2 and use that of WSe2/SiO2 as a reference system, since the TEC of SiO2 can be neglected compared with that of phosphorene23,24,25,26. Even though WSe2 in WSe2/SiO2 and WSe2/phosphorene/SiO2 experiences different dielectric environments which could affect the exciton binding energies of WSe2, in this study we are focusing on ΔE’ = ΔE(T1) − ΔE(T0), where ΔE(T) is the relative shift of photon energy in WSe2/phosphorene/SiO2 compared with that in WSe2/SiO2 at temperature T (see Fig. 2b). The effect of dielectric environment plays a minor role in determining ΔE’ as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Note 1. As illustrated in Fig. 2b, ΔE’ directly reflects the STD of WSe2 in the temperature range from T0 to T1. Considering the interlayer coupling effect at the WSe2/phosphorene interface, information of STD and ISTD in phosphorene layers can be extracted.

Characterizations of WSe2/phosphorene heterostructures

Figure 2c shows the optical image of a WSe2/phosphorene heterostructure, assembled by the PDMS-assisted dry-transfer method32. To achieve a high-quality vdW interface, all exfoliation and transfer processes were performed in a N2-filled glove box. The cross-sectional scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) image and elemental mapping demonstrate a clean and amorphous-phase-free WSe2/phosphorene interface (see Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Note 2). The Raman spectra collected from isolated monolayer WSe2, isolated phosphorene, and WSe2/phosphorene heterostructure are displayed in Fig. 2d, respectively. The characteristic phonon vibration modes of the monolayer WSe2 (\({E}_{2{{{{{\rm{g}}}}}}}^{1}\))33 and few-layer phosphorene (\({A}_{{{{{{\rm{g}}}}}}}^{1}\), B2g, and \({A}_{{{{{{\rm{g}}}}}}}^{2}\))34,35,36 are all observed in the heterostructure region. Figure 2e shows the PL spectra of the isolated WSe2 and WSe2/phosphorene heterostructure at 180 K, where layer numbers of the phosphorene are 50 (~27.5 nm) determined by atomic force microscope. Three pronounced photon emission peaks, located at 1.59, 1.67, and 1.70 eV, are observed. They can be attributed to localized exciton (Xloc), charged exciton (Xtrion), and neutral exciton (X)37,38, respectively. The Xtrion emission is more pronounced in WSe2/phosphorene heterostructure which can be attributed to the charge transfer at vdW interface39.

Then we explore the temperature-dependent properties of PL in the isolated WSe2 on SiO2 and WSe2/phosphorene heterostructure (see the schematic diagram in Fig. 3a). As shown in Fig. 3b, both X and Xtrion show energy shift when temperature changes. Moreover, X and Xtrion of WSe2/phosphorene heterostructure go through a greater shift than those of the isolated WSe2 on SiO2, indicating that additional strain is induced to the WSe2 on phosphorene when temperature changes. Figure 3c further compares the normalized PL of isolated WSe2 and WSe2/phosphorene heterostructure at three representative temperatures. The photon energy of X and Xtrion in WSe2/phosphorene heterostructure is larger than that in WSe2 at 10 K, the same at 200 K, and smaller at 300 K. With temperature changing, the top phosphorene layer performs greater in-plane lattice deformation than SiO2. Therefore, an additional strain is transferred into WSe2 on phosphorene through vdW interlayer interactions, leading to the greater shift of photon energy relative to that of WSe2 on SiO2. According to previous research results, tensile/compressive strain in monolayer WSe2 will reduce/enlarge its optical bandgap16,17,28,29,30, showing excellent agreement with our observations.

a Schematic diagram of PL characterizations on WSe2/SiO2 and WSe2/phosphorene/SiO2 regions. b PL of neutral exciton (X), charged exciton (Xtrion) and localized exciton (Xloc) in isolated WSe2 on SiO2 substrate and WSe2/phosphorene heterostructure from 10 to 300 K. The red dashed lines serve as guide lines. c The normalized PL spectra of isolated WSe2 (gray lines) and WSe2/phosphorene heterostructure (blue lines) at 10, 200, and 300 K. Here, the gray-blue arrows indicate that the photon energy of X and Xtrion in WSe2/phosphorene/SiO2 heterostructure is blue-shifted/red-shifted relative to those in WSe2/SiO2.

ISTD model and experimental measurement

To confirm our expectations, an ISTD model considering interlayer coupling effect is established to quantitatively determine the STD and ISTD in vdW materials. When temperature changes, the in-plane interlayer interaction is generated between adjacent layers due to lattice deformation mismatch (i.e., the ISTD). This produces additional in-plane stress in individual layer. Here, the in-plane stress is linked to ISTD through a proportionality factor, which is defined as the interlayer coupling coefficient (c) between adjacent layers. cp and ch denote the interlayer coupling coefficient at phosphorene/phosphorene homo-interface and WSe2/phosphorene hetero-interface, respectively.

Taking T0 as the initial state, the strain in each layer is 0 (see Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 1a, the STD of the n-th phosphorene (1 ≤ n ≤ N, counting from the bottom layer) from T0 to T1 is noted as τ(n). When 2 ≤ n ≤ N−1, the n-th phosphorene interacts with the (n−1)-th as well as with the (n + 1)-th phosphorene layers. Therefore, τ(n) satisfies the following equation at T1 [Eq. 1]:

Here, ∆τ(n) is the ISTD between the n-th and (n−1)-th phosphorene (Fig. 1a). γp is the Young’s modulus of phosphorene, which is around 60 GPa according to previous works40. τp is the thermally-induced intrinsic deformation of phosphorene, which is a constant depending on the TEC of phosphorene.

The cases of phosphorene/SiO2 (Fig. 1a) and WSe2/phosphorene/SiO2 (Fig. 1b) share the same boundary condition for n = 1 (at phosphorene/SiO2 interface). When n = 1, considering the strong clamping effect between the bottom phosphorene and SiO2 substrate18 as well as the tiny TEC of SiO226,27, an approximation can be made that the STD of the bottom phosphorene is negligible, that is, τ(1) = 0. When n = N, the mechanical behaviors of the top phosphorene are totally different in phosphorene/SiO2 and WSe2/phosphorene/SiO2 systems. In WSe2/phosphorene/SiO2 system, the interlayer interaction at phosphorene/WSe2 interface and the mechanical and thermal properties of WSe2 have direct impact on the STD of phosphorene layers. Please refer to Supplementary Note 3 for the details, where the interlayer coupling coefficient between phosphorene and WSe2 (ch), the Young’s modulus of WSe2 \(({\gamma }_{{{{{{\rm{WS}}}}}}{{{{{{\rm{e}}}}}}}_{2}})\) and thermally-induced intrinsic deformation of WSe2 \(({\tau }_{{{{{{\rm{WS}}}}}}{{{{{{\rm{e}}}}}}}_{2}})\) are introduced. Here, ch is calculated as 2.72 × 1011 Pa, \({\gamma }_{{{{{{\rm{WS}}}}}}{{{{{{\rm{e}}}}}}}_{2}}\) is assigned to be 120 GPa according to previous reports41,42,43,44,45, and \({\tau }_{{{{{{\rm{WS}}}}}}{{{{{{\rm{e}}}}}}}_{2}}\) is extracted to be −0.17% at 10 K (see Supplementary Note 4).

To confirm the validity of our theory, we experimentally characterize WSe2/phosphorene heterostructures with various phosphorene layer number N from 1 to 50. Figure 4a shows measured ∆E as a function of temperature at three representative layer numbers of 1, 5, and 50 (cyan symbols), respectively. Then, taking advantage of η = −100 meV/% (see Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Note 5), where η is the coefficient of strain-induced energy shift in monolayer WSe2, the additional in-plane strain of WSe2 in the heterostructure ε = ∆E/η can be extracted (violet symbols in Fig. 4a). The fitting results at other η values are further shown and compared in Supplementary Table 2.

a Cyan symbols show the temperature-dependent photon energy difference (ΔE) between WSe2/phosphorene and isolated WSe2 at phosphorene layer numbers of 1, 5, and 50, respectively. Violet symbols shows the experimentally measured strain of WSe2 as a function of temperature. b From 300 to 10 K, experimentally measured and theoretically fitted STD of WSe2 (τh) in WSe2/phosphorene and WSe2/hBN systems with different total layer number N. Here, for each sample, PL signals are collected from at least three spots near the center of heterostructures. The average value (pink/orange symbols) and standard deviation (error bar, black solid line) of τh (Ν) are therefore obtained from the measured ∆E. c Theoretically calculated layer-dependent ISTD (Δτ) in the WSe2/50-layer phosphorene/SiO2 system. Here, the empty circles denote Δτ at phosphorene-phosphorene interface while the filled circle denotes Δτ at phosphorene-WSe2 interface.

Taking 300 K as the initial temperature T0 and 10 K as the final temperature T1, the STD of WSe2 on N-layer phosphorene, τh(N) = (∆E(T1) − ∆E(T0))/η, is shown in Fig. 4b. The measured STD (pink symbols) agrees well with the theoretical fitting results (blue symbols), with fitting parameters cp = 3.41 × 1011 Pa and τp = −0.71%. The error analysis of the theoretical fitting results is provided in Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Note 6. Here, the larger interlayer coupling coefficient cp at phosphorene/phosphorene homo-interfaces than ch at WSe2/phosphorene hetero-interfaces indicates the stronger coupling at phosphorene/phosphorene homo-interfaces. When N > 15, τh is almost independent of layer number and reaches the minimum value of −0.42%. This phenomenon is in accordance with our expectations since the substrate clamping effect is weaker for top phosphorene layers when N is larger. Utilizing the fitting results above, we are able to calculate the n-dependent STD and ISTD quantitatively in WSe2/phosphorene/SiO2 systems with various total layer number N. Figure 4c shows the n-dependent ISTD (∆τ) in a WSe2/50-layer phosphorene heterostructure. With n increasing, there appears a crossover point where the negative ∆τ turns into positive. The slope is steeper near the phosphorene/SiO2 and WSe2/phosphorene hetero-interfaces due to strong mismatch of in-plane strain. Besides, we can access the layer-dependent in-plane force in phosphorene and WSe2 layers as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. The in-plane force is large near phosphorene/SiO2 and WSe2/phosphorene interfaces (at order of 0.1 N m−1) while vanishes in the central region.

Utilizing the fitting results of cp = 3.41 × 1011 Pa and τp = −0.71%, STD and ISTD of phosphorene in phosphorene/SiO2 system can be also calculated (see Supplementary Note 3). Here, we compare the calculation results of phosphorene/SiO2 and WSe2/phosphorene/SiO2 systems with different N in Fig. 5. Figure 5a and d are the schematic diagrams of the two cases at N = 5. In phosphorene/SiO2 system, STD of phosphorene (τ) decreases monotonously and nonlinearly with n (see Fig. 5b). When N > n > 15, τ is almost independent of n and reaches the minimum value of −0.71%, which approaches the intrinsic thermal deformation of phosphorene at 10 K. On the other hand, in WSe2/phosphorene/SiO2 system, STD of phosphorene initially decreases and then increases from bottom to top, revealing the non-uniform deformation near the WSe2/phosphorene interface (Fig. 5e). When N is large enough, τ reaches the minimum value −0.71% in the middle region (17 < n < 28 for N = 50) and increases to −0.53% at n = N. In addition, ∆τ of phosphorene increases monotonously with n and approaches zero when N > n > 15 in phosphorene/SiO2 system (Fig. 5c), while in WSe2/phosphorene/SiO2 system, ∆τ turns into positive values near the WSe2/phosphorene interface due to the small TEC and large Young’s modulus of WSe2 (Fig. 5f). The distinctions between the two cases directly reflect the interlayer coupling effect between WSe2 and phosphorene.

a Schematic diagram of 5-layer phosphorene/SiO2 under thermomechanical deformation at low temperature. b, c Theoretically calculated layer-dependent τ (b) and ∆τ (c) in phosphorene/SiO2 at representative layer numbers N = 5, 10, 20, 30, 40 and 50. d Schematic diagram of WSe2/5-layer phosphorene/SiO2 at at low temperature. e, f Theoretically calculated layer-dependent τ (e) and ∆τ (f) in WSe2/phosphorene/SiO2 at representative layer numbers N = 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50. Here, the empty symbols denote values in phosphorene while the filled symbols denote values in WSe2.

TEC of phosphorene

To our best knowledge, experimental studies on the TEC (α) of atomically-thin vdW layered materials are scarce, all of which are based on the high-temperature X-ray diffraction technique23,25,46, temperature-dependent Raman and electron energy-loss spectroscopy21,27. In the following section, we are going to show that the additional strain measured in WSe2/phosphorene heterostructures can be utilized to achieve this goal.

Utilizing the temperature-dependent additional strain of WSe2 in the WSe2/50-layer phosphorene (Fig. 4a), the intrinsic thermal strain of phosphorene as a function of temperature can be extracted through the ISTD model (violet symbols in Fig. 6a). A local band average approach under Debye approximation has declared that the temperature-dependent TEC is proportional to the specific heat (Cv) and can be expressed as47 [Eq. 2]:

where A is a constant and θD is the Debye temperature. Then the thermal strain of the phosphorene can be obtained by integrating TEC [Eq. 3]:

According to previous reports, θD = 600 K is used to conduct the fitting48. As shown in Fig. 6a, the fitted results (blue solid line) match well with the experimental results (violet symbols) with parameter A = 1.64 × 10−4 K−1, indicating the validity of our ISTD model. Figure 6b shows the extracted TEC of phosphorene from our theoretical model. The TEC is very small at low temperature and increases to 4.52 × 10−5 K−1 at 300 K. The obtained TEC ~ 4.52 × 10−5 K−1 at room temperature agrees quite well with previously reported values at high temperature (>300 K)23,24,25.

STD and TEC of hBN

Distinct from phosphorene, hBN possesses a negative TEC instead, whose absolute value is an order of magnitude smaller than that of phosphorene according to previous studies21,46. Therefore, to confirm the validity of our ISTD model, we repeat experiments based on WSe2/hBN heterostructures. The layer-dependent STD of hBN τ (n) is extracted and plotted in Fig. 4b, with fitting parameters chBN = 5.03 × 1011 Pa and τhBN = 0.17%. STD of WSe2 in WSe2/hBN and WSe2/phosphorene shows distinct trend with N. This phenomenon is in accordance with the small and negative TEC of hBN. Then, the WSe2/220-layer hBN heterostructure is adopted to extract TEC of hBN utilizing θD = 410 K46. The temperature-dependent TEC of hBN is plotted in Fig. 6b (purple symbols). The extracted TEC is −8.83 × 10−6 K−1 at room temperature, showing good agreement with reported values21,46. Therefore, the investigation of hBN further confirms the validity of our ISTD model and the effectiveness of the technique for sensing thermal properties of vdW layered materials.

Discussion

At last, we discuss the novelty of this work and the distinction from previous works13,49,50. First, we provide a smart strategy, the WSe2-based heterostructure, to investigate the mechanical, thermal, and interlayer coupling properties of vdW materials. Second, the ISTD model can quantitatively resolve the interlayer deformation in individual layers of vdW materials and heterostructures with various layer numbers. Third, the model can provide important interlayer coupling information, such as the interlayer coupling coefficients and in-plane force at phosphorene/phosphorene homo-interface and WSe2/phosphorene hetero-interface. Fourth, the intrinsic-thermal-deformation-induced strain is more stable, reversible, and controllable compared with mechanical bending/stretching, allowing us to provide a clearer physical picture of interlayer shear deformation and extract key thermal parameters accurately. Last, the model can be applied and extended to various deformation situations (both thermally-induced and mechanically-induced deformations) with various boundary conditions, which can be easily modified and used by other researchers. Hence, we believe the smart experimental methodology, the ISTD model, the clear physical picture and the interlayer coupling information provided in this work will inspire thermomechanical engineering in vdW materials and be beneficial to the scientific community of 2D materials.

Methods

Sample preparation

Monolayer and few-layer phosphorene/hBN flakes were mechanically exfoliated from bulk crystals (purchased from HQ graphene) onto 285 nm SiO2/Si substrate through the standard scotch tape method. To avoid material degradation, the exfoliation process was carried out in a N2-filled glovebox (MIKROUNA-Universal Series) with O2 and H2O concentrations smaller than 0.01 ppm. The monolayer WSe2 was exfoliated onto PDMS substrate. Then the WSe2/phosphorene and WSe2/hBN heterostructures were assembled using the PDMS-assisted dry-transfer method in the glovebox. We intentionally left half WSe2 flake on SiO2 as a reference to extract the thermal deformation of phosphorene and hBN. To improve the interlayer coupling between WSe2 and phosphorene/hBN, the samples are annealed at 200 °C for 10 min inside the glovebox.

Optical characterizations

To carry out the temperature-dependent PL measurements, the samples were loaded in a He-flow closed-cycle cryostat (Advanced Research System) with a high vacuum of ~2 × 10−6 Torr. A 532 nm laser was used as the excitation source and focused on the sample by a 50× objective lens (NA = 0.5). The laser power was kept at a low value of 25 μW to avoid laser-induced damage and heating effect. The PL signals were dispersed by an Andor SR-500i-D2 spectrometer with a 150 g/mm grating and detected using an Andor iVac 316 CCD. As for the Raman measurements, which were conducted at room temperature, a 600 g/mm grating was used.

Data availability

Relevant data supporting the key findings of this study are available within the paper and the Supplementary Information file. All raw data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Peng, Z., Chen, X., Fan, Y., Srolovitz, D. J. & Lei, D. Strain engineering of 2D semiconductors and graphene: from strain fields to band-structure tuning and photonic applications. Light.: Sci. Appl. 9, 190 (2020).

Dai, Z., Liu, L. & Zhang, Z. Strain engineering of 2D materials: issues and opportunities at the interface. Adv. Mater. 31, 1805417 (2019).

Liu, Y. et al. Tailoring sample-wide pseudo-magnetic fields on a graphene-black phosphorus heterostructure. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 828–834 (2018).

Bai, Y. et al. Excitons in strain-induced one-dimensional moiré potentials at transition metal dichalcogenide heterojunctions. Nat. Mater. 19, 1068–1073 (2020).

Edelberg, D., Kumar, H., Shenoy, V., Ochoa, H. & Pasupathy, A. N. Tunable strain soliton networks confine electrons in van der Waals materials. Nat. Phys. 16, 1097–1102 (2020).

Kim, H. et al. Actively variable-spectrum optoelectronics with black phosphorus. Nature 596, 232–237 (2021).

Reserbat-Plantey, A. et al. Strain superlattices and macroscale suspension of graphene induced by corrugated substrates. Nano Lett. 14, 5044–5051 (2014).

Choi, J. et al. Three-dimensional integration of graphene via swelling, shrinking, and adaptation. Nano Lett. 15, 4525–4531 (2015).

Branny, A., Kumar, S., Proux, R. & Gerardot, B. D. Deterministic strain-induced arrays of quantum emitters in a two-dimensional semiconductor. Nat. Commun. 8, 15053 (2017).

Darlington, T. P. et al. Imaging strain-localized excitons in nanoscale bubbles of monolayer WSe2 at room temperature. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 854–860 (2020).

Settnes, M., Power, S. R., Brandbyge, M. & Jauho, A.-P. Graphene nanobubbles as valley filters and beam splitters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 276801 (2016).

Zhang, S. et al. Tuning friction to a superlubric state via in-plane straining. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 116, 24452 (2019).

Wang, G. et al. Measuring interlayer shear stress in bilayer graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 036101 (2017).

Li, Z. et al. Efficient strain modulation of 2D materials via polymer encapsulation. Nat. Commun. 11, 1151 (2020).

Liang, J. et al. Monitoring local strain vector in atomic-layered MoSe2 by second-harmonic generation. Nano Lett. 17, 7539–7543 (2017).

Schmidt, R. et al. Reversible uniaxial strain tuning in atomically thin WSe2. 2D Mater. 3, 021011 (2016).

Ahn, G. H. et al. Strain-engineered growth of two-dimensional materials. Nat. Commun. 8, 608 (2017).

Huang, S. et al. Strain-tunable van der Waals interactions in few-layer black phosphorus. Nat. Commun. 10, 2447 (2019).

Plechinger, G. et al. Control of biaxial strain in single-layer molybdenite using local thermal expansion of the substrate. 2D Mater. 2, 015006 (2015).

Huang, S. et al. From anomalous to normal: temperature dependence of the band gap in two-dimensional black phosphorus. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 156802 (2020).

Cai, Q. et al. High thermal conductivity of high-quality monolayer boron nitride and its thermal expansion. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav0129 (2019).

Falin, A. et al. Mechanical properties of atomically thin boron nitride and the role of interlayer interactions. Nat. Commun. 8, 15815 (2017).

Keyes, R. W. The electrical properties of black phosphorus. Phys. Rev. 92, 580–584 (1953).

Sansone, G. et al. On the exfoliation and anisotropic thermal expansion of black phosphorus. Chem. Commun. 54, 9793–9796 (2018).

Henry, L. et al. Anisotropic thermal expansion of black phosphorus from nanoscale dynamics of phosphorene layers. Nanoscale 12, 4491–4497 (2020).

Oishi, J. & Kimura, T. Thermal expansion of fused quartz. Metrologia 5, 50–55 (1969).

Hu, X. et al. Mapping thermal expansion coefficients in freestanding 2D materials at the nanometer scale. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 055902 (2018).

Desai, S. B. et al. Strain-induced indirect to direct bandgap transition in multilayer WSe2. Nano Lett. 14, 4592–4597 (2014).

Frisenda, R. et al. Biaxial strain tuning of the optical properties of single-layer transition metal dichalcogenides. npj 2D Mater. Appl. 1, 10 (2017).

Cho, C. et al. Highly strain-tunable interlayer excitons in MoS2/WSe2 heterobilayers. Nano Lett. 21, 3956–3964 (2021).

Akamatsu, T. et al. A van der Waals interface that creates in-plane polarization and a spontaneous photovoltaic effect. Science 372, 68 (2021).

Castellanos-Gomez, A. et al. Deterministic transfer of two-dimensional materials by all-dry viscoelastic stamping. 2D Mater. 1, 011002 (2014).

Sahin, H. et al. Anomalous Raman spectra and thickness-dependent electronic properties of WSe2. Phys. Rev. B 87, 165409 (2013).

Castellanos-Gomez, A. et al. Isolation and characterization of few-layer black phosphorus. 2D Mater. 1, 025001 (2014).

Liu, H. et al. Phosphorene: an unexplored 2D semiconductor with a high hole mobility. ACS Nano 8, 4033–4041 (2014).

Wang, X. et al. Highly anisotropic and robust excitons in monolayer black phosphorus. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 517–521 (2015).

You, Y. et al. Observation of biexcitons in monolayer WSe2. Nat. Phys. 11, 477–481 (2015).

Jones, A. M. et al. Optical generation of excitonic valley coherence in monolayer WSe2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 634–638 (2013).

Hong, X. et al. Ultrafast charge transfer in atomically thin MoS2/WS2 heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 682–686 (2014).

Yang, Z., Zhao, J. & Wei, N. Temperature-dependent mechanical properties of monolayer black phosphorus by molecular dynamics simulations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 023107 (2015).

Feng, L.-p, Li, N., Yang, M.-h & Liu, Z.-t Effect of pressure on elastic, mechanical and electronic properties of WSe2: a first-principles study. Mater. Res. Bull. 50, 503–508 (2014).

Zeng, F., Zhang, W.-B. & Tang, B.-Y. Electronic structures and elastic properties of monolayer and bilayer transition metal dichalcogenides MX2 (M = Mo, W; X = O, S, Se, Te): A comparative first-principles study. Chin. Phys. B 24, 097103 (2015).

Kang, J., Tongay, S., Zhou, J., Li, J. & Wu, J. Band offsets and heterostructures of two-dimensional semiconductors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 012111 (2013).

Çakır, D., Peeters, F. M. & Sevik, C. Mechanical and thermal properties of h-MX2 (M = Cr, Mo, W; X = O, S, Se, Te) monolayers: a comparative study. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 203110 (2014).

Ding, W., Han, D., Zhang, J. & Wang, X. Mechanical responses of WSe2 monolayers: a molecular dynamics study. Mater. Res. Express 6, 085071 (2019).

Pease, R. S. An X-ray study of boron nitride. Acta Crystallogr. 5, 356–361 (1952).

Gu, M., Zhou, Y. & Sun, C. Q. Local bond average for the thermally induced lattice expansion. J. Phys. Chem. B 112, 7992–7995 (2008).

Kaneta, C., Katayama-Yoshida, H. & Morita, A. Lattice dynamics of black phosphorus. Solid State Commun. 44, 613–617 (1982).

Gong, L. et al. Reversible loss of Bernal stacking during the deformation of few-Layer graphene in nanocomposites. ACS Nano 7, 7287–7294 (2013).

Wang, G. et al. Bending of multilayer van der Waals materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 116101 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the STEM support of Xin Zhou from National University of Singapore and Chao Zhu from Southeast University, and SUSTech Core Research Facilities. The work was financially supported by the open research fund of Songshan Lake Materials Laboratory (2021SLABFN02, X.C.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 61904077, X.C.; 92064010, L.W.; 61801210, L.W.; 91833302, L.W.), the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2020YFA0308900, L.W.), the funding for “Distinguished professors” and “High-level talents in six industries” of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. XYDXX-021, L.W.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.C. and L.W. conceived and supervised the projects. L.Z., H.W. and X.Z. fabricated WSe2/phosphorene and WSe2/hBN heterostructure samples. L.Z. performed temperature-dependent photoluminescence characterizations with assistance of H.W., X.Z., and Y.Z. L.Z. and X.C. analyzed the experimental data. H.W. and X.C. did the theoretical modelling. H.W. performed Raman characterizations. X.C., L.Z., L.W., H.W. and T.W. drafted the paper. All authors discussed and commented the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Robert Klie and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Wang, H., Zong, X. et al. Probing interlayer shear thermal deformation in atomically-thin van der Waals layered materials. Nat Commun 13, 3996 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-31682-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-31682-w

This article is cited by

-

Infrared optoelectronics in twisted black phosphorus

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Mechanics of 2D material bubbles

Nano Research (2023)