Abstract

Reducing uncertainty in the response of the Amazon rainforest, a vital component of the Earth system, to future climate change is crucial for refining climate projections. Here we demonstrate an emergent constraint (EC) on the future response of the Amazon carbon cycle to climate change across CMIP6 Earth system models. Models that overestimate past global warming trends, tend to estimate hotter and drier future Amazon conditions, driven by northward shifts of the intertropical convergence zone over the Atlantic Ocean, causing greater Amazon carbon loss. The proposed EC changes the mean CMIP6 Amazon climate-induced carbon loss estimate (excluding CO2 fertilisation and land-use change impacts) from −0.27 (−0.59–0.05) to −0.16 (−0.42–0.10) GtC year−1 at 4.4 °C warming level, reducing the variance by 34%. This study implies that climate-induced carbon loss in the Amazon rainforest by 2100 is less than thought and that past global temperature trends can be used to refine regional carbon cycle projections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Emergent constraints (ECs) based on statistical relationships between past and future climate simulations of Earth system models (ESMs) and observational data are promising approaches to constrain the uncertainties of future climate change projections1,2,3. They include the casual dependencies between models’ estimates of current and future climate, which are expressed in terms of correlations, and the bias in the models’ estimates of current climate. The correlations, contingent upon the physically understood underlying mechanisms, allow estimating a range of ESMs that are consistent with observations4,5,6.

Recent studies have shown that ECs based on recent past observed global temperature (Thist) trends allow effective constraining of future change projections of global mean temperature (∆Tft) and precipitation (∆Pft) from ESMs contributing to phases 5 and 6 of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5 and CMIP6)4,7. Furthermore, substantial efforts have been directed towards proposing ECs on the carbon cycle, which is a key unknown in Earth System modelling, dependent on the climate forcing2,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. The ECs on carbon cycle are applied globally to reduce uncertainty of the sensitivity of the future carbon budgets, as well as soil carbon turnover to the global temperature change9,11,14, and regionally to reduce uncertainty in projected gross photosynthesis over northern extratropical regions, permafrost area loss, tropical carbon–climate feedback3,10,12,13,16,17. Reducing uncertainty of the tropical climate-induced changes in the carbon fluxes are of particular interest because it dominates the uncertainty of the future tropical and global land carbon cycle projections18,19,20.

Application of ECs holds significant promise for addressing uncertainties in the carbon cycle dynamics in the Amazon, the world’s largest tropical forest and a potential tipping element under climate change due to its profound influence on atmospheric dynamics and circulation patterns21,22,23,24,25,26. Although many studies have been conducted in this area over the last few decades (e.g., the Large-scale Biosphere–Atmosphere Experiments in Amazonia27), our understanding of Amazon functions in the Earth system is far from sufficient. A recent observational study revealed an increasingly negative coupling between interannual variations in tropical water availability and land carbon fluxes28. A CMIP6 ESM-based study has also identified a localized dieback in the Amazon rainforest and projected a decrease in the extent of humid regions and an expansion of areas with intense dry periods by 210025. A CMIP5 ESM-based study revealed a projected long-term future decrease in the land carbon uptake induced by soil moisture reductions, attributed to the nonlinear responses of vegetation carbon fluxes to water stress29. There is a clear need to improve our understanding of the interactions between climate variables, particularly related to temperature and water availability, and the Amazon’s carbon cycle dynamics in ESMs.

This work is motivated by a recent study (Ref. 4) that identified significant positive inter-model correlations between past global Thist trends and future global mean ∆Pft among CMIP5 and CMIP6 ESMs. The emergent relationship is based on the strong correlation between global Thist trends and ∆Tft that are both dominated by the change in the greenhouse gas forcing7, and the strong correlation between ∆Tft, and ∆Pft (via interconnections between tropospheric warming, longwave radiative cooling and latent heat through precipitation4,30). The authors (Ref. 4) elaborate that regional ∆Tft correlates well with ∆Pft in large parts of the world, while the Amazon basin presents a contrasting pattern with negative correlations. Thus, models with greater warming tend to have more increase of ∆Pft globally but larger decreases of ∆Pft in the Amazon basin. By combining the knowledge gained from this emergent relationship on future Amazon ∆Pft4 and considering recent observation- and model-based findings25,27,28,29, we examine whether recent global Thist trends can constrain future projections of climate change-induced carbon loss (when excluding CO2 fertilisation and land-use change impacts) in the Amazon rainforest. We further aim to shed light on the complex relationships between climate variables and the Amazon’s carbon cycle dynamics.

Here, we use the simulation outputs of twelve CMIP6 ESMs with an interactive carbon cycle driven in fully coupled (COU) and biogeochemically coupled (BGC) setups (Table S1). The BGC simulations include impacts of changes in atmospheric CO2 concentration on biosphere processes, but they do not include the radiative effects of CO2 concentration changes. Thus, the difference between COU and BGC simulations enables estimating the CO2 radiative impact on the climate and carbon fluxes31. Hereafter, we refer to the radiative effects of CO2 on carbon fluxes as their climate-driven changes, even when the scenario includes non-CO2 greenhouse gasses (GHGs), because CO2 concentration accounts for most of the GHG-induced forcing by 2100 under the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways 5-8.5 (SSP5-8.5)32. We focus on two scenario experiments, namely, SSP5-8.5 and 1% per year CO2 concentration increases for 140 years until quadrupling of pre-industrial levels (1pctCO2) (see Methods, Tables S1, S2, and Figs. S1–S10).

Results

Defining region and timeframe for ECs

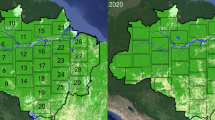

To propose ECs on future climate-driven changes in the carbon cycle, we first define the region for the analysis. As the region of interest is the Amazon rainforest, we limit it to the dense forest that contains a substantial carbon stock capable of accelerating global warming24 (we selected ESM output grids in which the total forest tree biomass exceeds 100 Mt degree grid−1, using data in Ref. 33, Fig. 1a). We considered alternatives such as defining the study area based on the Amazon basin or tropical rainforest vegetation type. However, we ultimately chose to prioritize the biomass threshold to focus on regions with substantial carbon storage potential. The decision to exclude broader areas like the Amazon basin aimed to prevent the inclusion of biomes beyond tropical forests, which might introduce confounding factors. Likewise, we avoided defining the study area solely based on vegetation type “tropical rainforest’ to ensure consistency across ESMs employing different vegetation maps.

a Total forest tree biomass in 195033. Black dots indicate grids with total biomass over 100 Mt. The middle and right panels indicate spatial patterns of inter-model Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the past 1980–2014 Thist trend and future changes in (b) precipitation ∆Pft and (c) climate-driven changes in NEPft estimated from the difference between fully coupled (COU) and biogeochemically coupled (BGC) simulations, respectively. We drew only correlations that are significant (p < 0.1 based on Welch’s t test). Here, N = 20 (SSP5-8.5 by 8 models and 1pctCO2 by 12 models).

Next, we verify the inter-model Pearson’s correlations between past global Thist trends and regional future changes in climate and the carbon cycle in those areas (Figs. 1 and S10). The Thist trends strongly depend on the radiative forcing, primarily driven by GHGs, although this relationship may be hindered by the uncertain aerosol forcing7. Here, we select the 1980–2014 period for defining the recent Thist trend to avoid the impacts of global aerosol emission changes on the Thist trend (the global aerosol emissions are nearly constant in this period due to the compensation between their decrease in North America and Europe and their increase in Asia)4,7. We estimate the future changes in surface climate and carbon fluxes using the COU and BGC ESM outputs of 1pctCO2 and SSP5-8.5 CMIP6 scenarios. To increase the sample size, we combine these two experiments by using the same (maximum possible) inter-model mean global ∆Tft level of 4.4 °C relative to preindustrial levels (see Methods). This level corresponds to the means over the periods of years 120–139 for the 1pctCO2 scenario (representing a nearly quadrupled CO2 concentration) and years 2072–2091 for the SSP5-8.5 scenario. Henceforth, we refer to ∆Tft and to future changes in other climate and carbon cycle variables, based on the aforementioned inter-model warming levels and time periods, unless otherwise indicated.

For estimating future changes in climate, we use COU, and for estimating climate-induced changes on carbon cycle we use the difference between COU and BGC simulation outputs of 1pctCO2 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios. Estimating the difference between BGC and COU (both of which have land-use change, non-CO2 GHG and aerosol impacts in SSP5-8.5) allows lessening (although not completely removing, see Ref. 34) the impacts of land-use change on carbon cycle primarily through alterations in carbon pools35 and radiative effects of non-CO2 GHGs and aerosols36 under the SSP5-8.5 scenario. Although the dynamics of carbon cycle feedbacks are intricately tied to the GHG concentration trajectories, a phenomenon referred to as scenario dependence37, simulation outputs from both the idealized 1pctCO2 and the more socially relevant SSP5-8.5 scenarios show comparable responses within the CMIP6 model ensemble mean. Consequently, our findings have potential applicability to a range of future scenarios characterized by high (4.4 °C) warming levels. Unlike some existing studies (Refs. 10,11), our approach does not involve estimating carbon-climate feedback. I.e., we do not normalise the climate-driven carbon flux estimates by each model’s ∆Tft (GtC year−1). Instead, our focus lies in estimating future changes in surface climate and climate-driven carbon fluxes corresponding to the mean warming level across ESMs. Thus, our estimation reflects the mean changes across the same future time periods.

In agreement with existing studies4,7, the inter-model Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the global Thist trend and regional grid-level ∆Tft changes are significantly positive (Fig. S10a). In contrast, the correlations between the global Thist trend and regional ∆Pft, as well as soil moisture (∆SMft), are significantly negative (Figs. 1b and S10b)4,38. Furthermore, the correlation coefficients between the global Thist trend and future grid-level climate-driven changes in carbon fluxes, namely, gross primary production (GPP) and net ecosystem production (NEP), defined as the balance between GPP and ecosystem respiration, are also significantly negative (Figs. 1c and S10c–e).

ECs of climate-driven changes in carbon uptake

We find statistically significant CMIP6 inter-model correlations (at p < 0.05) between global Thist trends and future changes in some climate variables averaged over the Amazon rainforest region (Figs. 2 and S11). In particular, global Thist trends positively correlate with regional ∆Tft and negatively correlate with ∆Pft4, as well as ∆SMft (Figs. 2a and S11). Additionally, we find strong negative correlations between the global Thist trends and future climate-driven changes in the Amazon carbon fluxes, i.e., ΔGPPft and ΔNEPft (Figs. 2b and S11). Previous studies have shown that ESMs with higher global Thist trends tend to project greater global warming in the future7. We show that “hot” ESMs with larger Thist past trends tend to project more warming and larger decreases in ΔPft4,38, ΔSMft, and climate-driven ΔGPPft and ΔNEPft over the Amazon region. The physical interpretation of these correlations is explained in the next section.

The vertical axes indicate the (a) ΔPft (%) and (b) climate-driven ΔNEPft (GtC year−1) in the Amazon forest estimated by the CMIP6 ESMs. The horizontal axes show the past global (1980–2014) trends of Thist (°C year−1). Pearson’s correlation coefficients and p values for two scenarios combined (SSP5-8.5 and 1pctCO2) are denoted at the bottom of the panels. The black dashed lines show the linear reduced major axis regressions. The horizontal box plots indicate the mean (white line), 17–83% range (box) and 5–95% range (horizontal bar) of the observed Thist trends of HadCRUT452 estimated by Ref. 4. (light blue). The vertical box plots show the same as the horizontal box plots but for the raw CMIP6 ESMs (black) and the constrained ranges using the observations (teal). The emergent constraint is estimated for the 120–139 year means of 1pctCO2 and 2072–2091 year means of SSP5-8.5 that both correspond to intermodel mean 4.4 °C warming relative to preindustrial level.

Because some ESMs overestimate the observed global mean Thist trends, the reliability of their projected ΔTft, ΔPft, ΔSMft, ΔGPPft, and ΔNEPft over the Amazon region is lower. Here, we apply a hierarchical ECs framework5 to constrain the uncertainty ranges of future changes in these variables (see Methods). By using this framework, we can constrain the means and ranges (Table S3) of future climate and climate-driven carbon fluxes over the Amazon region. We can lower the upper bounds (95th percentiles) of increase in ΔTft from 9.0 °C to 7.2 °C and raise the lower bounds (5th percentiles) of decrease in ΔPft (from 38% to 23%), ΔSMft (27% to 17%), climate-driven ΔGPPft (68% to 42%) and ΔNEPft (0.6 GtC year−1 to 0.4 GtC year−1), respectively. As a result, the variances of Tft, Pft, SMft, climate-driven GPPft, and NEPft can be reduced by 35%, 47%, 45%, 43%, and 34%, respectively.

Physical interpretation

ECs need explanations of the physical mechanisms underlying the correlations between the future changes and the observable past metric3. It is known that greater warming of the polar region than the other regions (polar amplification) leads to a northwards shift of the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ) over the Atlantic Ocean and drying and additional warming in the Amazon region39. Supplementary Fig. S12 shows future changes in vertical pressure velocity at the 500-hPa surface. ESMs with larger Thist trends tend to project downwards motion anomalies (positive values) over the Amazon region and the tropical Atlantic Ocean and upwards motion anomalies (negative values) over the subtropical region of the northern Atlantic Ocean, indicating more northwards shifts of the ITCZ. This suggests that ESMs with larger Thist trends (which project higher global warming in the future7) tend to project greater warming and drying in the Amazon basin due to these dynamical changes7.

We further find significant relationships across future changes in T, P and other variables over the Amazon region (Fig. 3). ESMs with larger warming (∆Tft) tend to project greater decreases in precipitation (∆Pft) and soil moisture (∆SMft) in the Amazon region. The climate-driven ΔGPPft exhibits significant negative correlations with ΔTft and positive correlations with ΔPft and ΔSMft. Hotter and drier conditions limit photosynthetic uptake (GPP) in tropical forests by the respective or combined stresses of high temperature and aridity. Concurrently, a larger ΔTft amplifies ecosystem respiration, comprising plant autotrophic respiration and soil decomposition40. The ecosystem response to the hotter and drier conditions via a simultaneous decrease in GPP and increase in ecosystem respiration results in a greater decrease in NEP. Consequently, the climate-driven ΔNEPft exhibits strong significant correlation with ΔTft (R = −0.68) and ΔPft (R = −0.80). These mechanisms can explain the correlations in Figs. 1, S10 and S12.

The matrix shows scatterplots, fitted linear regression lines (black lines) with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (grey shading), and Pearson’s correlation coefficients between future regional changes in climate variables, including ΔTft (°C), ΔPft (%) and ΔSMft (%), and climate-driven changes in carbon fluxes, including ΔGPPft (%) and ΔNEPft (GtC year−1), in the Amazon forest estimated by the considered CMIP6 ESMs for the 120–139 year means of 1pctCO2 and 2072–2091 year means of SSP5-8.5 that both correspond to intermodel mean 4.4 °C warming relative to preindustrial level. The statistical significance is shown by asterisks (** for p value < 0.01 and *** for p value < 0.001).

Discussion

We first constrain the climate-driven changes in tropical carbon uptake in the Amazon. The future CMIP6 model ensemble-mean climate-driven ΔNEPft and the 5–95% range (assuming a Gaussian distribution) under the SSP5-8.5 and 1pctCO2 scenarios (at the 4.4 °C ensemble mean warming level) can be constrained from −0.27 GtC year−1 and −0.59–0.05 GtC year−1 (mean and 5–95% range) to −0.16 GtC year−1 and −0.42–0.10 GtC year−1, the lower bands (5th percentile value) can be raised from −0.59 GtC year−1 to −0.42 GtC year−1, and the variance can be reduced by 34%. Increasing the mean Amazon climate-induced changes by the proposed EC corresponds to almost doubling future Amazon NEP, suggesting an enhanced carbon uptake capacity (Fig. S13). The proposed EC implies stronger resilience (less climate-induced carbon loss) of the Amazon rainforest to the projected changes in climate by the end of the 21st century.

We confirm that the EC is also valid on other lower multi-model ensemble mean warming levels, including 2.0 °C (that corresponds to the doubled CO2 concentration level of the idealized 1pctCO2 scenario) and 4.0 °C relative to preindustrial (Figs. S14 and Tables S4 and S5). The values of correlation coefficients increase with the increase of the warming level.

We show that climate-driven ΔNEPft in the Amazon rainforest is well related to ΔTft and ΔSMft, which in turn are well correlated with ΔPft. Notably, the highest correlation coefficient is between ΔNEPft and ΔPft. The proposed EC confirms the existing relationship between warming-induced precipitation shifts and consequential carbon cycle responses in the Amazon basin under high-warming scenarios. Under future warming, in addition to hotter conditions, the Amazon rainforest may be exposed to the lower mean annual precipitation. These conditions may lead to decreased ecosystem carbon sink / increased carbon source, increased risk of droughts and fires, favouring tropical forest biome transition to savanna, and thus triggering a potential tipping point41,42. To gain further understanding, in follow-up studies, it is necessary to decompose the contributions of T, P and SM and examine their mechanisms (e.g., via dynamic vegetation shifts and wildfire- and drought-related mortality) to the changes in the Amazon forest carbon cycle. Although the discussion of the possible mechanisms is ongoing25,26, most current generation ESMs lack adequate representation of these processes (Table S1, Refs. 43,44).

This study focuses on the climate-driven changes in the carbon fluxes, and therefore, the emergent constraint on CO2 concentration-driven and total changes in carbon flux in the Amazon were not presented. This is because the correlations between future changes in climate and carbon fluxes (concentration-driven and total) are small as shown in Fig. S15. The future uncertainty in the Amazon carbon uptake by CMIP6 ESMs is dominated by the ecosystem response to CO2 increase (Fig S13, also compare Figs. S1 and S2, S4 and S5). Even though the ESMs agree that rising CO2 concentrations increase the photosynthetic carbon uptake19,20,42, there are large uncertainties in the representations of CO2 concentration effects on carbon flux because there is still lack of evidence from the observation-based studies and large-scale free-air carbon dioxide enrichment (FACE) experiments on the long-term CO2 concentration effects on carbon fluxes19,20,28,42. This highlights a need for further investigating to what extent the larger climate-driven carbon loss in the Amazon basin is compensated by the CO2 concentration-driven carbon gains under future high warming scenarios. However, in contrast to changes driven by the CO2 concentration, the ESMs agree that climate-induced changes via warmer and drier conditions in the Amazon basin result in carbon loss due to reduced photosynthetic uptake, combined with increased respiration and tree mortality, as discussed above. The proposed EC allows reducing the uncertainty in the climate change-induced carbon loss in the Amazon forest.

The correlations between future changes in the surface climate and the climate-driven carbon cycle in the Amazon forest may be further decomposed into correlations between future changes driven by CO2 radiative effects (estimated from the difference between BGC and COU) and CO2 physiological effects (estimated from BGC) on climate. Strong statistically significant correlations between the carbon cycle and water cycle variables persist even when isolating the CO2 radiative effects but weaken when isolating the CO2 physiological effects (Fig. S15), underscoring the paramount role of CO2 radiative effects in the proposed EC.

Our analysis has unveiled robust and statistically significant correlations between the future climate-driven changes in the Amazon carbon fluxes and future global carbon fluxes when we exclude an ESM (CanESM5) whose global carbon–climate feedback parameter is positive (i.e., the negative impact of carbon-climate feedback at low latitudes is compensated by the positive impact of carbon–climate feedback at higher latitudes)31 and thus different from the others (Fig. S16). This provides model-based evidence that climate-induced changes in the Amazon carbon fluxes play a key role in driving the response of the global carbon cycle to climate change. Furthermore, the strong correlations between future climate-driven changes in the Amazon and global carbon fluxes suggest the potential applicability of our findings to a broader, global scale. The ESMs with larger recent past global mean temperature trends project greater climate-driven loss of carbon uptake in the Amazon and globally.

Considering these findings, we advocate for future studies to adopt integrated approaches, combining modelling, monitoring, and experimental methods to further analyse the future role of the Amazon forest carbon uptake in the global carbon cycle. Additionally, we urge further investigation into the causal relationship between large-scale circulation shifts and the observed increase in climate-induced carbon loss in the Amazon basin. Exploring whether these shifts lead to compensatory carbon gains in other global regions could be the next step in untangling the complex interplay of ecosystem responses to climate change and understanding its implications for global carbon cycle.

Methods

ESM simulations

We analysed historical, idealized 1pctCO2 (a scenario with an imposed 1% per year increase in the concentration of CO2 until quadrupling) and concentration-driven SSP5-8.5 simulations of twelve CMIP6 ESMs in the fully coupled (COU) and biogeochemically coupled (BGC) setups that were available at the time of analysis (Table S2). For the analysis, the following CMIP6 variables were utilized: near-surface air temperature, T (K); precipitation, P (kg m−2 s−1); surface downwelling shortwave radiation, RAD (W m−2); total cloud cover percentage, CLOUD (%); vertical velocity in pressure coordinates, ω (Pa s−1, positive values indicate downwards); moisture in upper 0.1 m of soil column, SM (kg m−2); carbon mass flux out of atmosphere due to gross primary production on land, GPP (kgC m−2 s−1); net primary production on land as carbon mass flux, NPP (kgC m−2 s−1); carbon mass flux into atmosphere due to autotrophic (plant) respiration on land, Ra (kgC m−2 s−1); and total heterotrophic (microbial) respiration on land as carbon mass flux, Rh (kgC m−2 s−1). The simulation outputs were corrected for the piControl drift, and the anomalies of the climate and carbon cycle variables (∆) were estimated relative to the mean over the 1850–1899 period of the historical simulations (Figs. S1–S6). In the scatterplot and time series figures (Figs. 2, S1 and S12), we express the changes in climate and carbon cycle fluxes, excluding NEP, as percentages. This choice is due to the considerable variation in the estimated absolute preindustrial values among ESMs. For NEP, which can fluctuate between positive and negative values, reflecting net ecosystem carbon sink/source dynamics, we employ units of GtC year−1.

Soil moisture in the soil column below 0.1 m may also be important for the Amazon forest, as developing deep root systems is one of the strategies employed by these ecosystems to cope with water stress45,46. Forests with well-developed root systems may exhibit greater resilience to droughts. Here we verified whether the established correlations between thin surface soil moisture and climate and carbon fluxes hold for the total soil moisture content, SM total (kgC m−2 s−1). We found that despite the large range of soil depths considered in ESMs (Table S1), correlations are significant between the future Amazon SMft total and GPP ft (p < 0.001) and the future Amazon SMft total and P ft (p < 0.01) (Fig. S17) across the ESMs. Thus, our findings stay valid for both soil moisture above and below 0.1 m.

To combine outputs of the 1pctCO2 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios, we estimated the ensemble mean ∆T of the twelve CMIP6 ESMs and found that the ΔT means of periods over years 120–139 of 1pctCO2 and years 2072–2091 of SSP5-8.5 both correspond to ∆T = 4.4 °C (Fig. S7). Consequently, these two periods were used for estimating the future response of climate and carbon cycle variables.

To isolate the impact of climate change on the carbon cycle, we used the carbon cycle feedback framework described in previous studies31,47. The changes in carbon storage (∆C, [GtC]) can be decomposed into the changes driven by the atmospheric CO2 concentration changes (∆CO2, [ppm]) and ∆T [°C]:

where \(\beta\) [GtC ppm−1] is the carbon–concentration feedback, \({{{\rm{\gamma }}}}\) [GtC °C−1] is the carbon–climate feedback, and \(\varepsilon\) [GtC] is the residual term. Analogously, the radiative impacts of ∆CO2 on climate variables can be estimated as the differences between the COU and BGC simulation outputs. These impacts exclude the biogeochemical impacts of ∆CO2 on climate36.

Evaluation of the ESM simulation outputs in the historical period

In order to ensure the reliability and accuracy of the estimates of climate and carbon cycle changes provided by the ESMs, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation of their simulation outputs in the historical period. This evaluation involved comparing ESM outputs with multiple historical datasets (Figs. S8 and S9). The surface climate estimates were evaluated against ERA5-Land reanalysis48, the GPP estimates were evaluated against the satellite-based products (GOSIF, MODIS and MUSES) and the NEP estimates were evaluated against Global Carbon Project 2021 (GCP2021) inversions. The ESMs adequately estimate the surface climate and carbon cycle over the historical period.

Emergent constraints

We established ECs based on temporal trends of past global Thist and future mean Amazon climate-driven ∆NEPft, following the methods used in global-scale climate EC studies7,38. The past global Thist trends estimates from HadCRUT4 are provided by Shiogama et al. (2022)4. The estimates account for the uncertainty of the internal climate variability in the observed trends using CMIP6 piControl runs and for the blending effects between air temperature over land, ice and the sea surface with limited coverage to the globally complete surface air temperature4.

To calculate the original uncertainty ranges, we assumed Gaussian distributions for the ESM spreads. We calculated the observationally constrained ranges of the future climate and carbon cycle projections by applying the hierarchical ECs framework, fully described by Bowman et al.5 and Shiogama et al.4.

In the hierarchical ECs framework, the mean of the constrained future projections (\(\mu \left(z | y\right)\)) are estimated as follows:

where z stands for unconstrained future projections by ESMs, x indicates past global Thist trends by ESMs, and y is the observational Thist trends of HadCRUT4. The \({\rho }_{x,\, z}\) indicates correlation between x and z. The \(\mu\) and \(\delta\) are the mean and standard deviations, respectively. The standard deviation of the constrained future projections (\(\delta \left(z | y\right)\)) is estimated as follows:

The relative reduction of variance (RRV) of the constrain relative to the unconstrained future projections can be estimated as follows:

Data availability

The data from the CMIP6 simulations are available from the CMIP6 archive: https://aims2.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/ (last accessed 20 July 2024). The global 1-degree maps of forest area, carbon stocks, and biomass for 1950–201033 are available from the ORNL DAAC archive: https://daac.ornl.gov/cgi-bin/dsviewer.pl?ds_id=1296 (last accessed 9 September 2023). ERA5-Land monthly averaged data from 1950 to the present48 are available from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS), https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-land-monthly-means?tab=form (last accessed 23 August 2023). The MUltiscale Satellite remotE Sensing (MUSES) product for GPP49 was downloaded from the Zenodo archive https://zenodo.org/record/3996814 (last accessed 23 August 2023). Globally gridded MODIS GPP MOD17A2H MODIS/Terra Gross Primary Productivity 8-Day L4 Global 500 m SIN Grid V00650 is available from NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mod17a2hv006/ (last accessed 24 August 2023). A global, fine-resolution dataset of GPP based on OCO-2, GOSIF GPP, is available from the Global Ecology Data Repository https://globalecology.unh.edu/data/GOSIF-GPP.html (last accessed 24 August 2023). Gridded top-down CO2 fluxes from GCP2021 inversions for 1970-2020, v2.1, were obtained from the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry data portal https://www.bgc-jena.mpg.de/geodb/projects/FileDetails.php (last accessed 24 August 2023). The processed data are available via Zenodo archive under accession code at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12195416.

Code availability

The data were analysed using CDO51 and Python. The code for reproducing the main plots of the manuscript are available via Code Ocean at https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.6574998.v1.

References

Hausfather, Z., Marvel, K., Schmidt, G. A., Nielsen-Gammon, J. W. & Zelinka, M. Climate simulations: recognize the ‘hot model’ problem. Nature 605, 26–29 (2022).

Hall, A., Cox, P., Huntingford, C. & Klein, S. Progressing emergent constraints on future climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 269–278 (2019).

Brient, F. Reducing uncertainties in climate projections with emergent constraints: concepts, examples and prospects. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 37, 1–15 (2020).

Shiogama, H., Watanabe, M., Kim, H. & Hirota, N. Emergent constraints on future precipitation changes. Nature 602, 612–616 (2022).

Bowman, K. W., Cressie, N., Qu, X. & Hall, A. A hierarchical statistical framework for emergent constraints: application to snow-albedo feedback. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 13,050–13,059 (2018).

Cox, P. M. Emergent constraints on climate-carbon cycle feedbacks. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 5, 275–281 (2019).

Tokarska, K. B. et al. Past warming trend constrains future warming in CMIP6 models. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz9549 (2020).

Raoult, N., Jupp, T., Booth, B. & Cox, P. Combining local model calibration with the emergent constraint approach to reduce uncertainty in the tropical land carbon cycle feedback. Earth Syst. Dyn. 14, 723–731 (2023).

Varney, R. M. et al. A spatial emergent constraint on the sensitivity of soil carbon turnover to global warming. Nat. Commun. 11, 5544 (2020).

Cox, P. M. et al. Sensitivity of tropical carbon to climate change constrained by carbon dioxide variability. Nature 494, 341–344 (2013).

Cox, P. M. et al. Emergent constraints on carbon budgets as a function of global warming. Nat. Commun. 15, 1885 (2024).

Wenzel, S., Cox, P. M., Eyring, V. & Friedlingstein, P. Projected land photosynthesis constrained by changes in the seasonal cycle of atmospheric CO2. Nature 538, 499–501 (2016).

Chadburn, S. E. et al. An observation-based constraint on permafrost loss as a function of global warming. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 340–344 (2017).

Wenzel, S., Cox, P. M., Eyring, V. & Friedlingstein, P. Emergent constraints on climate-carbon cycle feedbacks in the CMIP5 Earth system models. J. Geophys. Res.: Biogeosci. 119, 794–807 (2014).

Williams, R. G., Katavouta, A. & Goodwin, P. Carbon-cycle feedbacks operating in the climate system. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 5, 282–295 (2019).

Winkler, A. J., Myneni, R. B., Alexandrov, G. A. & Brovkin, V. Earth system models underestimate carbon fixation by plants in the high latitudes. Nat. Commun. 10, 885 (2019).

Zechlau, S., Schlund, M., Cox, P. M., Friedlingstein, P. & Eyring, V. Do emergent constraints on carbon cycle feedbacks hold in CMIP6? J. Geophys. Res.: Biogeosci. 127, e2022JG006985 (2022).

Berthelot, M., Friedlingstein, P., Ciais, P., Dufresne, J.-L. & Monfray, P. How uncertainties in future climate change predictions translate into future terrestrial carbon fluxes. Glob. Change Biol. 11, 959–970 (2005).

Zhang, K. et al. The fate of Amazonian ecosystems over the coming century arising from changes in climate, atmospheric CO2, and land use. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 2569–2587 (2015).

Ahlström, A. et al. Hydrologic resilience and Amazon productivity. Nat. Commun. 8, 387 (2017).

Sitch, S. et al. Recent trends and drivers of regional sources and sinks of carbon dioxide. Biogeosciences 12, 653–679 (2015).

Friedlingstein, P. et al. Global Carbon Budget 2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 4811–4900 (2022).

Gatti, L. V. et al. Amazonia as a carbon source linked to deforestation and climate change. Nature 595, 388–393 (2021).

Albert, J. S. et al. Human impacts outpace natural processes in the Amazon. Science 379, eabo5003 (2023).

Parry, I. M., Ritchie, P. D. L. & Cox, P. M. Evidence of localised Amazon rainforest dieback in CMIP6 models. Earth Syst. Dyn. 13, 1667–1675 (2022).

McKay, D. I. A. et al. Exceeding 1.5 °C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points. Science 377, eabn7950 (2022).

Avissar, R., Silva Dias, P. L., Silva Dias, M. A. F. & Nobre, C. The large-scale biosphere-atmosphere experiment in amazonia (LBA): Insights and future research needs. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 107, LBA 54–1 (2002).

Liu, L. et al. Increasingly negative tropical water–interannual CO2 growth rate coupling. Nature 618, 755–760 (2023).

Green, J. K. et al. Large influence of soil moisture on long-term terrestrial carbon uptake. Nature 565, 476–479 (2019).

Hohenegger, C. et al. Climate Statistics in Global Simulations of the Atmosphere, from 80 to 2.5 km Grid Spacing. J. Meteorological Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 98, 73–91 (2020).

Arora, V. K. et al. Carbon–concentration and carbon–climate feedbacks in CMIP6 models and their comparison to CMIP5 models. Biogeosciences 17, 4173–4222 (2020).

Meinshausen, M. et al. The shared socio-economic pathway (SSP) greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions to 2500. Geoscientific Model Dev. 13, 3571–3605 (2020).

Hengeveld, G. M. et al. Global 1-degree Maps of Forest Area, Carbon Stocks, and Biomass, 1950-2010. https://doi.org/10.3334/ORNLDAAC/1296 (2015).

Melnikova, I. et al. Impact of bioenergy crops expansion on climate-carbon cycle feedbacks in overshoot scenarios. Earth Syst. Dyn. 13, 779–794 (2022).

Gasser, T. et al. Historical CO2 emissions from land use and land cover change and their uncertainty. Biogeosciences 17, 4075–4101 (2020).

Jones, C. D. et al. C4MIP - The Coupled Climate–Carbon Cycle Model Intercomparison Project: experimental protocol for CMIP6. Geoscientific Model Dev. 9, 2853–2880 (2016).

Tachiiri, K. Relationship between physical and biogeochemical parameters and the scenario dependence of the transient climate response to cumulative carbon emissions. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 7, 74 (2020).

Shiogama, H., Takakura, J. & Takahashi, K. Uncertainty constraints on economic impact assessments of climate change simulated by an impact emulator. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 124028 (2022).

Shiogama, H. et al. Observational constraints indicate risk of drying in the Amazon basin. Nat. Commun. 2, 253 (2011).

Yao, Y. et al. A data-driven global soil heterotrophic respiration dataset and the drivers of its inter-annual variability. Glob. Biogeochemical Cycles 35, e2020GB006918 (2021).

Boers, N., Marwan, N., Barbosa, H. M. J. & Kurths, J. A deforestation-induced tipping point for the South American monsoon system. Sci. Rep. 7, 41489 (2017).

Flores, B. M. et al. Critical transitions in the Amazon forest system. Nature 626, 555–564 (2024).

Uribe, MdelR. et al. Net loss of biomass predicted for tropical biomes in a changing climate. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 274–281 (2023).

Cano, I. M. et al. Abrupt loss and uncertain recovery from fires of Amazon forests under low climate mitigation scenarios. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2203200119 (2022).

Nepstad, D. C. et al. The role of deep roots in the hydrological and carbon cycles of Amazonian forests and pastures. Nature 372, 666–669 (1994).

Liu, Y., Konings, A. G., Kennedy, D. & Gentine, P. Global coordination in plant physiological and rooting strategies in response to water stress. Glob. Biogeochemical Cycles 35, e2020GB006758 (2021).

Gregory, J. M., Jones, C. D., Cadule, P. & Friedlingstein, P. Quantifying carbon cycle feedbacks. J. Clim. 22, 5232–5250 (2009).

Sabater, M. J. ERA5-Land monthly averaged data from 1950 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.68d2bb30.

Wang, J. et al. New Global MuSyQ GPP/NPP remote sensing products from 1981 to 2018. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observations Remote Sens. 14, 5596–5612 (2021).

Running, S. W., Mu, Q. & Zhao, M. MOD17A2H MODIS/Terra Gross Primary Productivity 8-Day L4 Global 500m SIN Grid V006. NASA EOSDIS Land Process. Distrib. Act. Arch. Cent. https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MOD17A2H.006 (2015).

Schulzweida, U. CDO User Guide. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7112925 (2022).

Morice, C. P., Kennedy, J. J., Rayner, N. A. & Jones, P. D. Quantifying uncertainties in global and regional temperature change using an ensemble of observational estimates: The HadCRUT4 data set. J. Geophys. Res.: Atm. 117, D08101 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Ingrid Luijkx from Wageningen University & Research, Netherlands for providing the GCP2021 inversion data. We thank Mr. Kuniyasu Hamada for acquiring the necessary CMIP6 data. This work was supported by the Program for the Advanced Studies of Climate Change Projection (SENTAN, grant number JPMXD0722681344) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, by the Environment Research and Technology Development Fund (JPMEERF23S21130) of the Environmental Restoration and Conservation Agency and the Ministry of Environment of Japan and by KAKENHI (JP21H01161 and 21H05318) of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.S. initiated the study and provided insights about the hierarchical ECs framework. I.M. performed the analyses and wrote the paper with inputs from all the co-authors. T.Y., A.I., K. N. and K.T. contributed to the interpretation of the results. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Melnikova, I., Yokohata, T., Ito, A. et al. Emergent constraints on future Amazon climate change-induced carbon loss using past global warming trends. Nat Commun 15, 7623 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51474-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51474-8

This article is cited by

-

Combined emergent constraints on future extreme precipitation changes

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Amazon dieback beyond the 21st century under high-emission scenarios by Earth System models

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)