Abstract

The reverse water gas shift reaction can be considered as a promising route to mitigate global warming by converting CO2 into syngas in a large scale, while it is still challenging for non-Cu-based catalysts to break the trade-off between activity and selectivity. Here, the relatively high loading of Ni species is highly dispersed on hydroxylated TiO2 through the strong Ni and −OH interactions, thereby inducing the formation of rich and stable Ni clusters (~1 nm) on anatase TiO2 during the reverse water gas shift reaction. This Ni cluster/TiO2 catalyst shows a simultaneous high CO2 conversion and high CO selectivity. Comprehensive characterizations and theoretical calculations demonstrate Ni cluster/TiO2 interfacial sites with strong CO2 activation capacity and weak CO adsorption are responsible for its unique catalytic performances. This work disentangles the activity-selectivity trade-off of the reverse water gas shift reaction, and emphasizes the importance of metal−OH interactions on surface.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As an available but inert source of carbon, greenhouse gas CO2 can be converted by hydrogen to form CO, which can be used as the feedstock for synthetic fuels1,2,3,4,5,6. Except for Cu-based catalysts, the selective hydrogenation of CO2 to CO, known as the reverse water gas shift (RWGS) reaction, is always accompanied by severe methanation, especially for the low-cost Ni-based catalysts with high C–O bond cleavage capacity7,8,9. Currently, methanation can be effectively inhibited through reported methods, including reducing metal loading10,11,12, forming metal carbide/phosphide2,13, applying the encapsulation layer over metal sites14,15,16, decreasing particle size9, and varying the support materials17. However, these methods decrease the density of surface active sites, leading to a significant activity trade-off for high CO selectivity. Therefore, it is important but challenging to develop a strategy to break such activity-selectivity trade-off over non-Cu-based catalysts18,19,20.

To enable a simultaneous high CO selectivity at high CO2 conversion, a catalyst must satisfy two key requirements21. On the one hand, sufficient active sites are required to activate and dissociate CO222,23,24. On the other hand, active sites must possess relatively weak CO adsorption capacity, thus preventing the C–H bond formation and further hydrogenation to CH42,25. It has been reported that compared to metal nanoparticles, supported metal clusters (SMCs) in high oxidation states have less adsorbing strength to CO, allowing a higher CO selectivity in CO2 hydrogenation22,26. However, the stability of SMCs is usually negatively correlated with their surface density under harsh CO2 hydrogenation conditions, leading to cluster sintering and rapid deactivation9,27,28.

As one typical reducible support, TiO2 with active surface oxygen has been widely used in supporting active metals to catalyze RWGS reaction29,30. Unfortunately, due to its limited ability to disperse metal species, metal loadings above 2 wt% usually trigger the aggregation of SMCs on TiO2 and, with selectivity, switch to methanation31,32. A feasible pathway to overcome the above challenges is to construct anchoring sites on the TiO2 surface that increase the binding strength to SMCs during the reaction. Recent reports suggest that surface hydroxyl (–OH) can be considered an effective anchoring site for dispersing active metals33,34,35,36. Even at room temperature, enriched surface –OH can effectively redisperse sintered metal particles into single atoms and clusters. Therefore, it can be expected that the sinter-resistant cluster catalyst can be designed by modifying the TiO2 surface with sufficient –OH, a method yet to be reported.

Herein, by converting the commercial anatase TiO2 into H2Ti3O7 tubes with abundant surface –OH groups, Ni species with relatively high loading (10 wt%) are dispersed as isolated atoms anchoring via the strong –OH-Ni binding force. Under the reducing atmosphere, accompanied by the removal of surface −OH and the reduction of Ni species, isolated Ni atoms are converted into stable clusters and a few TiOx-covered particles. In contrast, Ni species aggregate into large-size particles with poor activity on the reference commercial TiO2. Comprehensive characterizations and theoretical simulations confirm that due to the presence of Ni cluster/TiO2 interfaces with improved CO2 activation and weak CO adsorption, the activity-selectivity trade-off of the RWGS reaction is prevented, achieving simultaneous high CO2 conversion and high CO selectivity. The catalytic performance of this catalyst exceeds almost all reported values in RWGS, demonstrating that the hydroxylation of oxide supports can play an important role in developing high-performance supported catalysts.

Results

Formation and structure of the Ni-cluster/TiO2 catalyst

By using the commercial anatase TiO2 as a precursor (denoted by TiO2-Ref1, Fig. 1a), hydroxylated H2Ti3O7 was obtained as support for the Ni/TiO2 catalyst37,38. The detailed synthesis process and the corresponding catalyst structure evolution were shown as follows. Firstly, during a hydrothermal treatment under highly concentrated NaOH (10 mol/L) with subsequent HCl washing, a tube-shaped H2Ti3O7 phase (denoted by TiO2-OH, Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1) was prepared as the result of TiO2 reconstruction. Owing to the phase transformation, plenty of intrinsic –OH groups were identified on the surface of TiO2-OH, whereas very few –OH groups were present on the reference TiO2-Ref1 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Secondly, 10 wt% Ni was loaded on TiO2-OH by the deposition–precipitation method, and the obtained sample without air calcination was denoted by 10Ni/TiO2-OH-UC (Fig. 1c). The catalyst was subsequently calcinated in air at 600 °C. The hydroxylated H2Ti3O7 underwent dehydration, leading to a phase change back to anatase TiO2 (Supplementary Fig. 3). The attenuated total internal reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR) test proved the maintenance of –OH groups on the surface even after calcination (Supplementary Fig. 4). Meanwhile, Ni was still well dispersed (denoted by 10Ni/TiO2-OH, Fig. 1d). The residual surface –OH on the as-prepared 10Ni/TiO2-OH catalyst improved the stability of isolated Ni atoms. The absence of Ni diffraction peaks in the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern for 10Ni/TiO2-OH implied the very small crystalline size of Ni species (Supplementary Fig. 3). The high dispersion of Ni over 10Ni/TiO2-OH was further confirmed by the atomic-resolution high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images and X-ray energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping results (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 5). The Fourier-transform extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) results of 10Ni/TiO2-OH showed no Ni–Ni bond, demonstrating that Ni species were dispersed on the TiO2-OH support dominantly as single Ni atoms, though the presence of a small number of sub-nanometer Ni clusters could not be ruled out (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 1). It was noteworthy that Ni single atoms on the catalyst surface were very sensitive to the radiation of high energy electron beam in TEM operating at 300 kV, and they would aggregate (<1 nm) with the increase of radiation time (Supplementary Fig. 7). Therefore, all the STEM images were collected within 10 s under small beam current. The schematic illustration of the generation process of 10Ni/TiO2-OH is depicted in Fig. 1e.

Structure of the catalyst was further studied after the H2 pretreatment and CO2 hydrogenation (Fig. 2a). After the RWGS reaction (23%CO2/69%H2/8%N2) at 600 °C, isolated Ni atoms were converted into Ni clusters with the average size of ~1 nm (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 8) and a few large-sized Ni particles (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 9) on the sintered TiO2 support. The EDS-mapping results further indicated the good dispersion of Ni clusters, with Ni element appearing uniformly with Ti and O (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 10). Due to the strong metal-support interaction (SMSI)39, Ni particles were covered by a thin TiOx overlayer (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 11), which has been widely reported in previous literatures14,30,40. The X-ray absorption near edge spectroscopy (XANES) of used 10Ni/TiO2-OH indicated the reduction of Ni species during the H2 pretreatment and the subsequent reaction process (Supplementary Fig. 6a). As illustrated by the EXAFS profiles (Supplementary Fig. 6b) and the 2-D contour plots wavelet transform (WT) results (Supplementary Fig. 6c, f), the obvious Ni–Ni contribution over used Ni/TiO2-OH suggested the aggregation of single Ni atoms, which was consistent with the XRD result (Supplementary Fig. 12).

In contrast, fresh and used Ni/TiO2-Ref1 catalysts exhibited distinctly different structures. Although the TiO2-Ref1 support morphology maintained well during the synthesis process, Ni particles with an average size of ~9.6 nm were formed on the catalyst surface after the air calcination at 600 °C (Supplementary Fig. 13). After the pretreatment and reaction, this catalyst further underwent severe sintering, and the average size of Ni particles increased to ~27.6 nm (Supplementary Fig. 14). Large-size Ni particles was further confirmed by the element mapping (Supplementary Fig. 15). Interestingly, based on ex-situ EELS-mapping results for 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1, no obvious TiOx overlayer was found on Ni particles (Supplementary Fig. 16), which might be caused by the limited reducibility of TiO2-Ref1 (Supplementary Fig. 17). Based on above comprehensive experimental results, we provide a strategy for synthesizing Ni cluster catalysts by using hydroxylated TiO2 as support. Compared to commercial TiO2-Ref1 with poor ability to disperse Ni species, hydroxylated TiO2 with abundant –OH groups could effectively anchor Ni single atoms, thereby forming rich and durable Ni clusters even under harsh reaction conditions (600 °C and reducing atmosphere).

In order to explore the mechanism of the effect of –OH groups on anchoring single Ni atoms under the air calcination, we carried out density functional theory (DFT) calculations. We adopted the anatase TiO2(101) surface to model the substrate. We noted that (101) was the most abundant surface of anatase TiO241 that contained twofold coordinated O2c atoms and fivefold coordinated Ti5c atoms along the [010] direction (Supplementary Fig. 18). Supplementary Fig. 19 illustrated three types of hydroxylated TiO2(101) surfaces, in which the adsorption configurations of the Ni single atom were explored. The stable structures are shown in Fig. 3a, with the calculated adsorption energies listed in Supplementary Table 2. When single Ni atom adhered to an –OH group located at the fivefold coordinated Ti5c atom (OH5c/TiO2, Supplementary Fig. 19a), the corresponding adsorption energies of Ni/OH5c-TiO2-I and Ni/OH5c-TiO2-II were higher than that on a bare anatase TiO2(101) surface (−5.83 eV, −5.81 eV vs. −2.89 eV). Notably, these values were also higher than the calculated cohesive energy of bulk Ni (−5.83 eV, −5.81 eV vs. −5.47 eV), meaning that the interaction between the Ni atom and the OH5c/TiO2 substrate was stronger than the interaction between Ni atoms in their bulk phase. Bader charge analysis (Supplementary Table 2) showed that the single Ni atom in Ni/OH5c-TiO2-I and Ni/OH5c-TiO2-II exhibited considerable positive charges (+0.88 |e| and +0.78 |e|), which enabled it to be stabilized via the electrostatic attraction with surrounding O atoms42. In addition, the projected electronic density of states of the Ni atom overlapped with that of the bonded O atoms (Fig. 3b), indicating that covalent interaction also existed between Ni and O. Hence, both electrostatic and covalent interactions within the Ni–O bonds contributed to the excellent stability of the adsorbed Ni atoms on the Ni/OH5c-TiO2-I and Ni/OH5c-TiO2-II models.

a Two most stable adsorption configurations of a single Ni atom on an OH5c/TiO2 surface (denoted as Ni/OH5c-TiO2-I and Ni/OH5c-TiO2-II, respectively), with the corresponding adsorption energies shown in Supplementary Table 2. b Projected electronic density of states (PDOS) of the single Ni atom and of the O atoms bonded with Ni in Ni/OH5c-TiO2-I (left) and Ni/OH5c-TiO2-II (right). The Fermi level was set to 0 eV. c Potential energy diagram for the removal of –OH group and the generation of the Ni–H species. Here, TS represents the transition state, and S1 and S3 correspond to Ni/OH5c-TiO2-II and Ni/OH5c-TiO2-I, respectively. d Potential energy diagram for the diffusion of the Ni-H species on the TiO2(101) surface.

During the subsequent H2 pretreatment and the RWGS reaction, the potential mechanism of the transformation process from isolated Ni atoms to clusters was also explored by DFT simulations. Here, both Ni/OH5c-TiO2-I and Ni/OH5c-TiO2-II were considered as the initial states to investigate the subsequent structural changes of the Ni single atom. Under an H2 atmosphere, the −OH group in Ni/OH5c-TiO2-I could be easily removed by forming a water molecule with the H atom (Fig. 3c: S4 → TS → S5). Regarding Ni/OH5c-TiO2-II, although a direct removal of the –OH group (Supplementary Fig. 20: S2 → TS → S3) was a relatively hard process with an energy barrier of 1.06 eV, Ni/OH5c-TiO2-II could facilely transform to Ni/OH5c-TiO2-I with an energy barrier of only 0.03 eV (Fig. 3c: S1 → S2 →S3). It meant that the −OH removal in Ni/OH5c-TiO2-II could also occur easily, following the same pathway as that of Ni/OH5c-TiO2-I. Upon desorption of the water molecule (Fig. 3c: S5 → S6), a Ni–H species was left on the TiO2(101) surface. This Ni–H species could easily diffuse on the TiO2(101) surface, exhibiting an energy barrier of only 0.59 eV (Fig. 3d). As a comparison, the diffusion of an isolated Ni atom was also considered (Supplementary Fig. 21), and the corresponding energy barrier was calculated to be 1.03 eV. It could be seen that under reaction conditions, the H atom adsorbed on Ni could promote its diffusion, which was reminiscent of the effect of CO on the diffusion of Pt adatoms on Fe3O4(001)43. The removal of the –OH group and the promotion of the Ni diffusion under the H2 atmosphere well explained the agglomeration of Ni atoms to clusters observed after CO2 hydrogenation.

Catalytic performance of the Ni/TiO2-OH catalysts with rich and stable Ni clusters

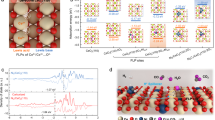

It has been reported that compared to large-size Ni particles, Ni clusters with poor electronic transfer to CO molecules can promote the desorption of carbonyl (CO*) species to form gaseous CO molecules9. Therefore, it can be expected that the obtained 10Ni/TiO2-OH catalyst with abundant Ni clusters could exhibit high catalytic performance to catalyze the RWGS reaction. As shown in Fig. 4a, 10Ni/TiO2-OH had high CO2 conversion, which was comparable to the thermodynamic equilibrium limitation at 500 °C and 600 °C. However, due to the aggregated Ni particles, the CO2 conversion of 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1 was less than 10% even at 600 °C. Meanwhile, 10Ni/TiO2-OH showed excellent CO selectivity, maintaining above 90% at all reaction temperatures, in clear contrast to the generally observed near 100% selectivity towards methane which is generally observed on nickel-based catalysts. In order to further compare the product selectivity of 10Ni/TiO2-OH and 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1 with distinctly different Ni structures, additional activity tests were performed. Through controlling GHSV, we tried to compare the product selectivity of 10Ni/TiO2-OH and 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1 under a similar CO2 conversion. As shown in Fig. 4b, even when the GHSV was increased to 800,000 mL gcat−1 h−1, the CO2 conversion of 10Ni/TiO2-OH was still much higher than that of 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1 with a much lower GHSV of 20,000 mL gcat−1 h−1. Under such test conditions, the CO selectivity of 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1 was slightly lower but still over 85% compared to that of 10Ni/TiO2-OH, over 98%, which seemed to conflict with the previously reported results that large-size metal particles led to the high CH4 selectivity9. To resolve this confusion, by reducing the air calcination temperature and the subsequent pretreatment temperature of 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1 from 600 °C to 500 °C, we further synthesized another reference catalyst with relative smaller Ni particles than 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1 and referred to as 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1-500, in which Ni particle size was ~12.4 nm (Supplementary Fig. 22). As the particle size decreased, the catalytic activity was improved compared to 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1, but it was still lower than that of 10Ni/TiO2-OH with abundant Ni clusters (Supplementary Fig. 23). Importantly, at similar CO2 conversion rates, the CO selectivity of 10Ni/TiO2-OH (98.9%) was much higher than that of 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1-500 (21.3%), indicating the selectivity difference between clusters and particles in catalyzing CO2 hydrogenation (Fig. 4b). Based on above results, the relationship between the Ni size on TiO2 and the product selectivity in atmospheric CO2 hydrogenation could be clearly revealed. On the one hand, compared to highly dispersed Ni clusters, Ni particles induced the formation of CH4. In addition, when the average size of Ni particle was larger than 27 nm, it was meaningless to discuss the product selectivity due to the very poor catalytic activity.

a The CO2 conversion and CO selectivity for 10Ni/TiO2-OH and 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1 catalysts under the GHSV of 400,000 mL gcat–1 h–1. b Comparison of CO selectivity at 500 °C within relative comparable CO2 conversion rates for 10Ni/TiO2-OH, 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1 and 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1 after calcination at 500 °C and H2 pretreatment at 500 °C (10Ni/TiO2-Ref1-500). c CO2 conversion rates versus CO selectivity reported non-Cu based catalyst for CH4 production (blue triangles, SelCO < 50%) and CO production (red squares, SelCO > 50%), and this work (red circle) at 400 °C. Inset: comparison of CO yield rates over 10Ni/TiO2-OH catalysts and Cu-based catalysts at 500 °C. d The long-term stability of the 10Ni/TiO2-OH catalyst tested for 300 h at 600 °C (GHSV = 800,000 mL gcat−1 h−1).

As reported, extensive efforts have been made to optimize the CO selectivity of non-Cu catalysts by regulating the catalyst structure2,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. However, due to the presence of an activity-selectivity trade-off, it was very challenging to achieve the combination of high activity and high selectivity (non-Cu-based catalysts ordered 1–1513,23,44,45,46,47,48 in Fig. 4c and Supplementary Table 3). Obviously, 10Ni/TiO2-OH successfully broke the trade-off between activity and selectivity with a high CO selectivity of 91.9% while maintaining an excellent reaction rate of 214.4 μmol gcat−1 s−1 at 400 °C. Furthermore, compared to Cu-based catalysts, which were regarded as prevailing catalysts for catalyzing the RWGS reaction, 10Ni/TiO2-OH with an excellent reaction rate of 873.0 μmolCO gcat−1 s−1 and a high CO selectivity of 98.0% at 500 °C was also highly advantageous (Cu-based catalysts ordered 16–196,49,50 in inset of Fig. 4c and Supplementary Table 3). The apparent activation energy (Ea) and the corresponding CO2 conversion and CO selectivity for 10Ni/TiO2-OH were shown in Supplementary Fig. 24. Besides, the catalytic performance of 10Ni/TiO2-OH was evaluated in different reaction atmospheres with various H2 to CO2 ratios. With the increase of the ratio of H2 to CO2, CO2 conversion increased slightly (Supplementary Fig. 25a), suggesting this catalyst possessed a high catalytic activity over a wide input reaction gas composition. Moreover, it was found that the CO selectivity maintained over 90% even when the H2 to CO2 ratio reached 4:1 (Supplementary Fig. 25b), which indicated that the methanation was indeed inhibited by this catalyst. Due to the harsh reaction conditions of the high-temperature RWGS reaction, reported supported catalysts are always severely deactivated by the catalyst sintering51,52. In this work, the long-term stability of 10Ni/TiO2-OH was evaluated. As shown in Fig. 4d, under very harsh reaction conditions (600 °C and GHSV = 800,000 mL gcat−1 h−1), 10Ni/TiO2-OH remained stable with the CO2 conversion more than ~55% and showed almost complete CO selectivity. Besides, 10Ni/TiO2-OH also suggested a high start-up cool-down stability (Supplementary Fig. 26a). In contrast, under relatively milder reaction conditions, 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1 lost almost all of its activity in only 2.5 h (Supplementary Fig. 26b), which was accompanied by the significant increase in particle size (Supplementary Fig. 27), further demonstrated the importance of suppressing the Ni sintering for reaction activity. Based on the above results, 10Ni/TiO2-OH with rich Ni clusters efficiently broke the activity-selectivity trade-off of the RWGS reaction and achieved a combination of high activity, high CO selectivity and excellent stability. To the best of our knowledge, the catalytic performance of 10Ni/TiO2-OH was unmatched by almost all other reported catalysts employed for the atmospheric high-temperature RWGS reaction.

The structure of the catalyst after 300 h of steady-state reaction at 600 °C was explored by HAADF-STEM. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 28, Ni clusters were still anchored on the catalyst surface. This result again emphasized the efficiency of –OH groups on the TiO2-OH support for constructing active Ni structure.

Strong interaction between the Ni cluster and TiO2-OH

It has been established that catalyst structures and catalytic performances are largely determined by the MSI. Therefore, it is essential to reveal the interaction between Ni species and the TiO2-OH support for 10Ni/TiO2-OH, thereby understanding the stable interfacial structure and the molecule activation behavior. Firstly, we used the temperature-programmed hydrogen reduction (H2-TPR) technique to investigate the redox properties of the 10Ni/TiO2-OH catalyst. As shown in the H2-TPR profile (Fig. 5a), pure NiO exhibited two reduction peaks centered at 352 °C and 401 °C, which could be attributed to the cascading reduction of Ni2+ to Ni+ and then to Ni0. 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1 showed similar reduction features to that of pure NiO, suggesting a very weak interaction between Ni species and TiO2-Ref1. Compared to pure NiO, the increased reduction temperatures for 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1 might be caused by the size difference of NiO. The reduction peak of the 10Ni/TiO2-OH sample was centered at 494 °C, much higher than that of the above two samples, which indicated a higher energy barrier to break the Ni-O bond. By quantifying the consumed H2 based on H2-TPR results (Supplementary Fig. 29), it could be found that the reduction peaks of 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1 were mainly from the NiO reduction to Ni since the actual hydrogen consumption was close to the theoretical value. This again confirmed the weak MSI between Ni species and TiO2-Ref1. However, the actual H2 consumption of 10Ni/TiO2-OH was much higher than the theoretical H2 consumption, suggesting that partial surface oxygen atoms of TiO2-OH support were reduced to generate TiOx structure. According to previous literature, the formation of TiOx could cover the large-size metal particles53,54, so large-size Ni particles on 10Ni/TiO2-OH were covered by TiOx, while the same phenomenon was not found on 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1. The above analysis of H2-TPR results clearly revealed that TiO2-OH with abundant –OH groups could induce the formation of the enhanced interaction between Ni and TiO2-OH, promoting the sintering-resisting capacity of Ni clusters on the TiO2 surface. Actually, in addition to anchoring Ni species, such a strong interaction stabilized the TiO2. Unlike pure TiO2-OH supports seriously sintered after the air calcination at 500 °C (Supplementary Fig. 30a, b), TiO2 in 10Ni/TiO2-OH maintained the tube-shape morphology well (Supplementary Fig. 30c, d).

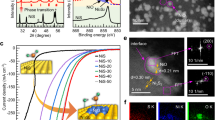

a H2-TPR profiles of the NiO, 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1 and 10Ni/TiO2-OH samples. b XPS spectra and corresponding fitting curves of Ni 2p in the 10Ni/TiO2-OH-UC and 10Ni/TiO2-OH catalysts. Quasi in situ XPS spectra and corresponding fitting curves of Ni 2p in 10Ni/TiO2-OH catalyst after RWGS reaction at 600 °C for 3 h. c In situ infrared spectra recorded after exposing the TiO2-OH after H2 pretreatment and 10Ni/TiO2-OH catalysts after H2 pretreatment and RWGS reaction to CO at 130 K with 1 × 10−2 mbar. d The in-situ Ni L-edge NAP-NEXAFS profile of the 10Ni/TiO2-OH catalyst.

The strong interaction between Ni and TiO2 in 10Ni/TiO2-OH was further verified by the following quasi in situ XPS, in situ infrared spectra (IR), and in situ near ambient pressure (NAP) near edge X-ray absorption fine structure (NEXAFS). From the Ni 2p XPS spectra (Fig. 5b), the Ni 2p1/2 binding energy (B.E.) of as-prepared 10Ni/TiO2-OH was at ~855.6 eV, which was attributed to the presence of Ni2+2. After the RWGS reaction, besides the Ni2+ species at ~855.6 eV, the Ni0 species at ~852.0 eV also appeared22, which suggested the reduction of Ni2+ under the reducing atmosphere. The Ni2+/(Ni0 + Ni2+) ratio was calculated to be ~66%, indicating that even after the treatment by the reaction gas with highly concentrated H2 of 69%, a majority of Ni2+ species still existed on the catalyst surface. The presence of abundant Ni2+ species represented the electronic metal-support interaction (EMSI) between Ni species and TiO2, which prevented Ni species from agglomerating on the TiO2 support surface caused by the easy reduction. Because the Ni species in 10Ni/TiO2-OH with excellent CO selectivity featured a weak adsorption capacity for CO molecules, it was difficult to use CO molecules as probes to characterize the state of Ni species by in situ DRIFTS at room temperature. In general, the decrease in temperature could improve the adsorption strength of metal species for CO molecules, so as to more clearly characterize the state of metal species55. Therefore, in situ IR spectra of CO adsorption were collected at a low testing temperature of 130 K with a pressure of 1 × 10−2 mbar (Fig. 5c). Pristine TiO2-OH pretreated with H2 exhibited a main peak at 2168 cm–1 with a shoulder peak at 2147 cm–1, ascribed to the adsorption of CO on distinct exposed facets of TiO256. By contrast, there were two extra peaks in the Ni/TiO2-OH catalyst. One at 2152 cm−1 was assigned to CO linearly adsorbed on Ni2+ sites57,58. In addition, the signal at 2090 cm−1 likely corresponded to sub-carbonyl Ni(CO)x (x = 2 or 3) species, which featured a highly disordered structure and were attributed to amorphous Ni sites59,60. Similar results were observed as the CO partial pressure was reduced to 1 × 10−7 mbar (Supplementary Fig. 31). The dominant Ni2+-CO signal confirmed the presence of rich Ni2+, which again presented the strong EMSI between Ni and TiO2. Moreover, the sub-carbonyl species were weakly adsorbed, which was favored by CO removal, thereby facilitating the high CO selectivity of the RWGS reaction. Ni L-edge NAP-NEXAFS was further measured to detect the surface Ni species under various atmospheres. Auger electron yield (AEY) for Ni L3 (853 eV to 856 eV) and L2 (870 eV to 872 eV) was observed (Fig. 5d), which were related to 2p3/2 to 3d and 2p1/2 to 3d transition, respectively. For 10Ni/TiO2-OH, the relatively stable Ni L edge signals suggested the high stability of Ni2+ even under H2 and RWGS reaction flows at 400 °C, which further indicated the EMSI between Ni and the support. In comparison, 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1 showed a significant change in intensity at 855.5 eV under the H2 atmosphere at 300 °C, demonstrating that Ni2+ was easily reduced to Ni0 (Supplementary Fig. 32). The surface structure of the TiO2 support over 10Ni/TiO2-OH was also explored by XPS and NAP-NEXAFS. The Ti 2p XPS spectra exhibited that even after the treatment by the RWGS reaction flow at 600 °C, only Ti4+ species but no obvious Ti3+ signal could be found (Supplementary Fig. 33a). The in situ Ti L-edge NAP-NEXAFS profile of 10Ni/TiO2-OH also did not detect the formation of Ti3+ under H2 and reaction flows (Supplementary Fig. 33b). Based on above results, we speculated that even though the MSI between Ni and TiO2 facilitated the partial reduction of TiO2, the limited concentration of surface Ti3+ sites were below the detection line of XPS and in situ NEXAFS techniques. The created Ti3+ might be moved into the bulk phase of anatase TiO261.

The proposed reaction mechanism of CO2 hydrogenation catalyzed by Ni/TiO2-OH

To identify the potential reaction mechanism of CO2 hydrogenation to CO catalyzed by this highly performed 10Ni/TiO2-OH catalyst, we first evaluated the CO2 adsorption ability through the temperature-programmed desorption of CO2 (CO2-TPD) (Supplementary Fig. 34). Compared to 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1 with weak capacity to adsorb CO2, two strong CO2 desorption peaks appeared over 10Ni/TiO2-OH. By comparing the result of Ar-TPD, the first feature at low temperatures could be ascribed to chemisorbed CO2 molecules, and the latter one was related to the decomposition of surface carbides. The strong CO2 desorption signal indicated that compared to 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1, rich Ni cluster-TiO2 interfaces might serve as crucial sites for absorbing CO2. Subsequently, DFT calculations were performed to further understand the adsorption and activation of CO2 on this Ni cluster catalyst through a catalyst model of Ni8/TiO2 surface (Ni8/TiO2 model seen Supplementary Fig. 35). It should be noted that because no distinct Ti3+ signal was detected on the catalyst surface, we did not consider the presence of oxygen vacancies in this constructed catalyst model. As shown in Fig. 6a, CO2 was easily adsorbed at the Ni cluster-TiO2 interface with an adsorption energy of −0.95 eV, and the Ni8 cluster became ship-shaped. Meanwhile, H2 was spontaneously dissociated into two H* on the Ni cluster. This result declared that the Ni cluster/TiO2 interface, which was ultra-stable in the RWGS reaction, could be considered as a significant active structure to activate reactant molecules.

a CO2 adsorption on Ni8/TiO2 system and H2 adsorption on CO2-Ni8/TiO2 system. b, c In situ diffused reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) spectra of 10Ni/TiO2-OH catalyst during CO2 treatment and reaction conditions (CO2 + H2) at 300 °C, respectively. d Potential energy diagram for the RWGS reaction on Ni8/TiO2(101) via carboxyl and formate pathways. The illustration showed the structures of some intermediate and transition states. The complete reaction pathways are shown in Supplementary Figs. 38 (carboxyl) and 39 (formate). “TS” represents the transition state.

Moreover, we also explored the CO2 hydrogenation mechanism of 10Ni/TiO2-OH. The mechanisms of the RWGS reaction have been categorized into two types: redox mechanism and associative mechanism. The dissociation experiment of CO2 was conducted to investigate the reaction pathway. After the H2/Ar pretreatment at 600 °C, the CO2/Ar mix gas was injected into the reactor after the sample was cooled to room temperature. However, there was no generation of CO and consumption of CO2 during the subsequent warming process, which indicated that CO might not be produced by the direct dissociation of CO2 on the 10Ni/TiO2-OH catalyst (Supplementary Fig. 36a). In contrast, the temperature-programmed surface reaction (TPSR) results showed that the CO2 signal gradually decreased start from 300 °C, accompanied by the increase of CO signal, demonstrating that the dissociation of CO2 into CO required the assistance of H2 (Supplementary Fig. 36b). By combining the results of the CO2 dissociation experiment and TPSR, it could be inferred that CO2 activation likely occurred through an associative intermediate pathway rather than the redox mechanism. Similar results were revealed by in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS). After CO2 injection, only carbonate species appeared, without signal of formate and CO signal, which further proved that it was difficult for CO2 to be directly dissociated to CO (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 37a). Subsequently, H2 flow was introduced to the 10Ni/TiO2-OH catalyst, a new feature corresponding to formate species was identified at 1606 cm‒1 61, while it was absent with N2 purging on the surface of the catalyst (Supplementary Fig. 37b). This result suggested that the reaction intermediate was generated in the presence of H2 during the CO2 dissociation. Moreover, the simultaneous injection of CO2 and H2 also promoted the formation of formate intermediates along with the gaseous and adsorbed CO signal (Fig. 6c), which was consistent with the TPSR results. DFT calculations were performed to further explore the associative mechanisms by using the Ni8/TiO2 catalyst model (Supplementary Fig. 35). Here, the carboxyl and the formate pathways were both taken into account. As shown in Fig. 6d and Supplementary Figs. 38 and 39, we presented the energy profiles of these two reaction pathways. It could be seen that the rate-determining steps of these two pathways were the formation of COOH* (carboxyl pathway) and HCOOH* (formate pathway), and the corresponding energy barriers were 1.57 eV and 1.94 eV (carboxyl: TS1; formate: TS3), respectively, indicating that the carboxyl pathway was kinetically favorable. Notably, the COOH* intermediate could easily decompose into CO* and OH*, while on the contrary, HCOO* was difficult to further hydrogenated and converted into products. This suggested that COOH* was a more active intermediate than HCOO*, which was in consistent with the previously reported spectator role of formate62.

Discussion

For heterogeneous catalytic reactions, the conversion of reactants and the selectivity of products often change largely along with the evolution of catalyst structures. Therefore, the construction of dense and stable active structures has always been at the core of the catalyst design. In this work, the ability of the commercial TiO2 to anchor active metals is greatly enhanced via the hydroxylation, which guarantees that highly loaded Ni species were anchored dominantly as single atoms. The strong interaction between intrinsic –OH groups and highly dispersed Ni species was proven to play an essential role in the formation of sintering-resisting clusters in the RWGS reaction. Due to the strong MSI between Ni clusters and TiO2 induced by the surface –OH, the formed rich Ni/TiO2 interfaces not only promoted the H2-assisted CO2 dissociation but also suppressed the formation of CH4, thereby breaking the activity-selectivity trade-off of the RWGS reaction. This work provides a strategy to design high-performance supported catalysts for heterogeneous reactions with harsh conditions by constructing hydroxylated oxides with enriched –OH groups.

Method

Preparation of TiO2 tube precursor

All of the chemicals applied to our experiments were of analytical grade and were used without further purification or modification. The TiO2 tube precursor was prepared by hydrothermal method in Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclaves. For a typical synthesis of support, 28 g of NaOH (Sinopharm) was dissolved in 70 mL of deionized water (10 mol/L). After that, 2 g of anatase TiO2 (Macklin, particle size = 100 nm, denoted as TiO2-Ref1) was added into the above solution with stirring for 1 h at room temperature. Then the mixture was heated at 130 °C for 24 h. After the hydrothermal synthesis, the fresh precipitates were filtered and washed with deionized water and 2 L of 0.2 M HCl (Sinopharm) aqueous solution followed by deionized water. The resulting material was dried in air at 80 °C for 18 h and then ground in a mortar. Hereafter, the TiO2 tube precursor was denoted as TiO2-OH.

Preparation of Ni catalysts

In a typical deposition-precipitation (DP) method, 0.5 g TiO2-OH powders were added to 25 mL deionized water at room temperature under vigorous stirring. 4.28 mL of 0.1 mol/L Ni(NO3)2·6H2O (Sinopharm) were added to the above suspension dropwise. The pH value of the solution was kept at ca. 9 with the assistance of Na2CO3 (Macklin) during the whole course. After stirring at room temperature for 30 min, the precipitates were further aged at room temperature for 1 h. Then, they were purified by suction filtration with deionized water (1 L) at room temperature. Finally, the product was dried at 70 °C for 10 h and then calcined in air at 600 °C for 4 h24,63. In our report, the nickel-titanium samples are denoted as xNi/TiO2-OH, where x is the nickel content in weight percent. The referenced catalyst was prepared by the same method only except that the calcination temperature was 500 °C was denoted as 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1-500. The referenced catalyst was also prepared by the DP method as above just with the other purchased commercial TiO2 (denoted as TiO2-Ref1).

Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) characterization

High-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) STEM images, X-ray EDS spectra and elemental mappings, and EELS measurements were obtained from a Thermo Scientific Themis Z microscope equipped with a probe-forming spherical-aberration corrector at an operating voltage of 300 kV (Analytical Instrumentation Center of Hunan University).

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)

The XPS measurements were carried out at a Thermo scientific ESCALAB Xi+ XPS spectrometer from Thermo Fisher. Quasi in situ XPS experiment was carried out on the same instrument. The spectrums of Ni 2p, Ti 2p, C 1s, and O 1s were obtained after 3 h of reaction in 15% CO2/30% H2/N2 atmosphere at 600 °C. The C 1s signal located at 284.8 eV was used to calibrate each spectrum for accurate binding energies24.

Catalytic tests

The catalytic performance evaluation was tested in a fixed-bed flow reactor under a gas atmosphere of 23% CO2/69% H2/N2 (66.7 mL min−1, Deyang Gas Company, Jinan) at 1 bar total pressure24. Before activity test, 10 mg catalysts (20‒40 mesh) diluted with 90 mg inert SiO2 were activated by 5% H2/Ar at 600 °C for 0.5 h followed by switching to the feed gas for testing. The 10Ni/TiO2-Ref1-500 catalyst was activated by 5% H2/Ar at 500 °C for 0.5 h followed by switching to the feed gas for testing. The test temperature ranges from 400 °C to 600 °C. Before the analysis of gas products, the RWGS reaction needs to stabilize for 1 h at each test temperature. The gas products were analyzed by using an on-line gas chromatograph equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). CO2 conversion and CO selectivity were calculated using the following equations:

where \({{{\mathrm{n}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{CO}}}}_{2}}^{{{\mathrm{in}}}}\) is the concentration of CO2 in the reaction stream, and \({{{\mathrm{n}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{CO}}}}_{2}}^{{{\mathrm{out}}}}\), \({{{\mathrm{n}}}}_{{{\mathrm{CO}}}}^{{{\mathrm{out}}}}\), \({{{\mathrm{n}}}}_{{{{\mathrm{CH}}}}_{4}}^{{{\mathrm{out}}}}\) are the concentrations of CO, CO2, CH4 in the outlet. For all catalysts, the Ea was measured by using the same reactor for catalytic performance above. Appropriate amounts of catalysts diluted with inlet SiO2 were used in the kinetics experiments. In order to obtain accurate kinetics data, the catalysts need to be first treated with reactive gas for an hour at 600 °C. During the kinetic test, the CO2 conversion remained between 5% and 15% by changing the gas flow rate. In order to minimize the effect of the external diffusion, for a reaction rate at 500 °C, 3 mg of catalyst and reaction gas flow of 120 mL/min were used, and CO2 conversion was 13.0% with CO selectivity of 98.07%. In order to better track the deactivation behavior, we used a much higher GHSV (800,000 mL gcat−1 h−1) in the long-term stability test. Due to the poor CO selectivity of the reference catalyst, the rate of CO2 conversion was used for the reaction rate at 400 °C, while the rate of CO production was used for the almost complete CO selectivity of the reference catalyst at 500 °C.

Theoretical calculations

Details of the computational methods and the calculation model are put in the Supplementary Materials.

Data availability

The main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. Additional data are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Zhang, X. et al. Reversible loss of core–shell structure for Ni–Au bimetallic nanoparticles during CO2 hydrogenation. Nat. Catal. 3, 411–417 (2020).

Galhardo, T. S. et al. Optimizing active sites for high CO selectivity during CO2 hydrogenation over supported nickel catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 4268–4280 (2021).

Yang, H. et al. A review of the catalytic hydrogenation of carbon dioxide into value-added hydrocarbons. Catal. Sci. Technol. 7, 4580–4598 (2017).

Wang, W., Wang, S., Ma, X. & Gong, J. Recent advances in catalytic hydrogenation of carbon dioxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 3703–3727 (2011).

Nelson, N. C., Chen, L., Meira, D., Kovarik, L. & Szanyi, J. In situ dispersion of palladium on TiO2 during reverse water–gas shift reaction: formation of atomically dispersed palladium. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 17657–17663 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Highly dispersed copper over β-Mo2C as an efficient and stable catalyst for the reverse water gas shift (RWGS) reaction. ACS Catal. 7, 912–918 (2017).

Winter, L. R., Gomez, E., Yan, B., Yao, S. & Chen, J. G. Tuning Ni-catalyzed CO2 hydrogenation selectivity via Ni-ceria support interactions and Ni-Fe bimetallic formation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 224, 442–450 (2018).

Zhao, B. et al. High selectivity of CO2 hydrogenation to CO by controlling the valence state of nickel using perovskite. Chem. Commun. 54, 7354–7357 (2018).

Vogt, C. et al. Unravelling structure sensitivity in CO2 hydrogenation over nickel. Nat. Catal. 1, 127–134 (2018).

Li, S. et al. Tuning the selectivity of catalytic carbon dioxide hydrogenation over iridium/cerium oxide catalysts with a strong metal–support interaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 129, 10901–10905 (2017).

Dong, C. et al. Disentangling local interfacial confinement and remote spillover effects in oxide-oxide interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 17056–17065 (2023).

Yang, B. et al. Size-dependent active site and its catalytic mechanism for CO2 hydrogenation reactivity and selectivity over Re/TiO2. ACS Catal. 13, 10364–10374 (2023).

Wei, X. et al. Surfactants used in colloidal synthesis modulate Ni nanoparticle surface evolution for selective CO2 hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 14298–14306 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Enhanced CO2 methanation activity of Ni/anatase catalyst by tuning strong metal-support interactions. ACS Catal. 9, 6342–6348 (2019).

Matsubu, J. C. et al. Adsorbate-mediated strong metal-support interactions in oxide-supported Rh catalysts. Nat. Chem. 9, 120–127 (2017).

Xin, H. et al. Overturning CO2 hydrogenation selectivity with high activity via reaction-induced strong metal-support interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 4874–4882 (2022).

Vogt, C. et al. Understanding carbon dioxide activation and carbon–carbon coupling over nickel. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–10 (2019).

Hu, J. et al. Sulfur vacancy-rich MoS2 as a catalyst for the hydrogenation of CO2 to methanol. Nat. Catal. 4, 242–250 (2021).

Guan, Q. et al. Bimetallic monolayer catalyst breaks the activity–selectivity trade-off on metal particle size for efficient chemoselective hydrogenations. Nat. Catal. 4, 840–849 (2021).

Jiao, F. et al. Disentangling the activity-selectivity trade-off in catalytic conversion of syngas to light olefins. Science 380, 727–730 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Breaking the linear scaling relationship of the reverse water-gas-shift reaction via construction of dual-atom Pt-Ni pairs. ACS Catal. 13, 3735–3742 (2023).

Zheng, H. et al. Unveiling the key factors in determining the activity and selectivity of CO2 hydrogenation over Ni/CeO2 catalysts. ACS Catal. 12, 15451–15462 (2022).

Zhang, C. et al. Tuning the CO2 hydrogenation activity and selectivity by highly dispersed Ni-In intermetallic alloy compounds. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 12, 166–177 (2024).

Liu, H. X. et al. Partially sintered copper‒ceria as excellent catalyst for the high-temperature reverse water gas shift reaction. Nat. Commun. 13, 867 (2022).

Lin, S. et al. Ni-Zn dual sites switch the CO2 hydrogenation selectivity via tuning of the d-Band center. ACS Catal. 12, 3346–3356 (2022).

Dong, C. et al. Supported metal clusters: fabrication and application in heterogeneous catalysis. ACS Catal. 10, 11011–11045 (2020).

Du, G. et al. Methanation of carbon dioxide on Ni-incorporated MCM-41 catalysts: the influence of catalyst pretreatment and study of steady-state reaction. J. Catal. 249, 370–379 (2007).

Sun, H. et al. Integrated carbon capture and utilization: synergistic catalysis between highly dispersed Ni clusters and ceria oxygen vacancies. Chem. Eng. J. 437, 135394 (2022).

Tang, Y. et al. Rh single atoms on TiO2 dynamically respond to reaction conditions by adapting their site. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–10 (2019).

Monai, M. et al. Restructuring of titanium oxide overlayers over nickel nanoparticles during catalysis. Science 380, 644–651 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Controlling CO2 hydrogenation selectivity by metal-supported electron transfer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 19983–19989 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Confinement-induced indium oxide nanolayers formed on oxide support for enhanced CO2 hydrogenation reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 5523–5531 (2024).

Fan, Y. et al. Water-assisted oxidative redispersion of Cu particles through formation of Cu hydroxide at room temperature. Nat. Commun. 15, 3046 (2024).

Wang, F. et al. Identification of direct anchoring sites for monoatomic dispersion of precious metals (Pt, Pd, Ag) on CeO2 support. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202318492 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. Construction of Ptδ+-O(H)-Ti3+ species for efficient catalytic production of hydrogen. ACS Catal. 13, 10500–10510 (2023).

Fan, Y. et al. Surface hydroxyl-determined migration and anchoring of silver on alumina in oxidative redispersion. ACS Catal. 13, 2277–2285 (2023).

Pappas, D. K. et al. Novel manganese oxide confined interweaved titania nanotubes for the low-temperature selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of NOx by NH3. J. Catal. 334, 1–13 (2016).

Kataoka, K. et al. Ion-exchange synthesis, crystal structure, and physical properties of hydrogen titanium oxide H2Ti3O7. Inorg. Chem. 52, 13861–13864 (2013).

Fu, Q. et al. Metal-oxide interfacial reactions: encapsulation of Pd on TiO2 (110). J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 944–951 (2005).

Liu, S. et al. Encapsulation of platinum by titania under an oxidative atmosphere: contrary to classical strong metal-support interactions. ACS Catal. 11, 6081–6090 (2021).

Lazzeri, M. et al. Structure and energetics of stoichiometric TiO2 anatase surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 63, 155409 (2001).

Qiao, B. et al. Ultrastable single-atom gold catalysts with strong covalent metal-support interaction (CMSI). Nano Res. 8, 2913–2924 (2015).

Bliem, R. et al. Dual role of CO in the stability of subnano Pt clusters at the Fe3O4(001) surface. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 8921–8926 (2016).

Ren, J. et al. Ni-based hydrotalcite-derived catalysts for enhanced CO2 methanation: thermal tuning of the metal-support interaction. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 340, 123245 (2024).

Li, W. et al. CO2 hydrogenation on unpromoted and M-promoted Co/TiO2 catalysts (M = Zr, K, Cs): effects of crystal phase of supports and metal-support interaction on tuning product distribution. ACS Catal. 9, 2739–2751 (2019).

Yan, B. et al. Tuning CO2 hydrogenation selectivity via metal-oxide interfacial sites. J. Catal. 374, 60–71 (2019).

Lin, L. et al. Reversing sintering effect of Ni particles on γ-Mo2N via strong metal support interaction. Nat. Commun. 12, 6978 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. Product selectivity controlled by nanoporous environments in zeolite crystals enveloping rhodium nanoparticle catalysts for CO2 hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 8482–8488 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Highly efficient Cu/CeO2-hollow nanospheres catalyst for the reverse water-gas shift reaction: Investigation on the role of oxygen vacancies through in situ UV-Raman and DRIFTS. Appl. Surf. Sci. 516, 146035 (2020).

Wang, L. X. et al. Dispersed nickel boosts catalysis by copper in CO2 hydrogenation. ACS Catal. 10, 9261–9270 (2020).

Campbell, C. T. et al. The effect of size-dependent nanoparticle energetics on catalyst sintering. Science 298, 811–814 (2002).

Dai, Y. et al. The physical chemistry and materials science behind sinter-resistant catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 4314–4331 (2018).

Du, X. et al. Size-dependent strong metal-support interaction in TiO2 supported Au nanocatalysts. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–8 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Structure sensitivity of Au-TiO2 strong metal–support interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 12074–12081 (2021).

Chen, A. et al. Structure of the catalytically active copper–ceria interfacial perimeter. Nat. Catal. 2, 334–341 (2019).

Chen, S. et al. Probing surface structures of CeO2, TiO2, and Cu2O nanocrystals with CO and CO2 chemisorption. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 21472–21485 (2016).

Millet, M. M. et al. Ni single atom catalysts for CO2 activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 2451–2461 (2019).

Cerdá-Moreno, C. et al. Ni-sepiolite and Ni-todorokite as efficient CO2 methanation catalysts: mechanistic insight by operando DRIFTS. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 264, 118546 (2020).

Jensen, M. B. et al. FT-IR characterization of supported Ni-catalysts: influence of different supports on the metal phase properties. Catal. Today 197, 38–49 (2012).

Zarfl, J. et al. DRIFTS study of a commercial Ni/γ-Al2O3 CO methanation catalyst. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 495, 104–114 (2015).

Scheiber, P. et al. Surface mobility of oxygen vacancies at the TiO2 anatase (101) surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 1–5 (2012).

Nelson, N. C. et al. Carboxyl intermediate formation via an in situ-generated metastable active site during water-gas shift catalysis. Nat. Catal. 2, 916–924 (2019).

Yu, W. Z. et al. Very high loading oxidized copper supported on ceria to catalyze the water-gas shift reaction. J. Catal. 402, 83–93 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars of China (22225110, C.-J.J.), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFA1501103, C.-J.J.), the National Science Foundation of China (22075166, C.-J.J. and 22271177, W.-W.W.), the Science Foundation of Shandong Province of China (ZR2023ZD21, C.-J.J.), the Young Scholars Program of Shandong University (W.-W.W.), EPSRC (EP/P02467X/1 and EP/S018204/2, F.-R.W.), Royal Society (RG160661, IES\R3\170097, IES\R1\191035, IEC\R3\193038, F.-R.W.). We acknowledge SPring-8 (Japan) for the XAFS experiments conducted under proposal No. 2021A1387 and Dr. Hiroyuki Asakura from Kyoto University for helping with the XAFS measurement. We thank the Center of Structural Characterizations and Property Measurements at Shandong University for the help on sample characterizations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.-J. Jia and F. R. Wang supervised the work; C.-X. Wang, X.-M. Lai, X.-H. Liu, X.-P. Fu and C.-J. Jia designed the experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote the manuscript; J.-Y. Li and Q. Fu performed the DFT simulations; C. -X. Wang, X.-M. Lai and W.-W. Wang performed the in situ DRIFTS, in situ Raman, and quasi in situ XPS; C. -X. Wang, and X.-M. Lai performed the catalysts preparation, catalytic tests and the TPR tests; C. Ma performed the aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM measurements and analyzed the results; H. Gu, X.-H. Liu and F. R. Wang performed the XAFS experiments and analyzed the data.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Bert Weckhuysen and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, CX., Liu, HX., Gu, H. et al. Hydroxylated TiO2-induced high-density Ni clusters for breaking the activity-selectivity trade-off of CO2 hydrogenation. Nat Commun 15, 8290 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52547-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-52547-4