Abstract

We report an important role for microglia in regulating neuroplasticity within phrenic motor neurons. Brief episodes of low oxygen (acute intermittent hypoxia; AIH) elicit a form of respiratory motor plasticity known as phrenic long-term facilitation (pLTF) that is regulated by the balance of competing serotonin vs adenosine-initiated cellular mechanisms. Serotonin arises from brainstem raphe neurons, but the source of adenosine is unknown. We tested if hypoxic episodes initiate phrenic motor neuron to microglia fractalkine signaling that evokes extracellular adenosine formation using a well-defined neurophysiology preparation in male rats. With moderate AIH, phrenic motor neuron adenosine 2A receptor activation undermines serotonin-dominant pLTF whereas severe AIH induces pLTF by the adenosine-dependent mechanism. Consequently, phrenic motor neuron fractalkine knockdown, microglial fractalkine receptor inhibition, and microglial ablation enhance moderate AIH, but suppress severe AIH-induced pLTF. We conclude, microglia play important roles in healthy spinal cords, regulating plasticity in motor neurons responsible for breathing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microglia are resident immune cells of the central nervous system. In healthy brains, they also perform important physiological roles in neuronal homeostasis and regulation of synaptic plasticity by engaging in reciprocal communication with other cells through multiple ligands and receptors. For example, the neuro-chemokine fractalkine (Fkn; CX3CL1) is expressed by and released from neurons in response to physiological stimuli, such as neuronal activity or hypoxia, thereby activating Fkn receptors on nearby microglia1,2,3,4,5,6. In the healthy CNS, Fkn is expressed predominantly by neurons, whereas its receptor (CX3CR1) is expressed exclusively by microglia7,8,9. Previous studies indicate neuron-microglial Fkn signaling regulates important neural functions such as hippocampal synaptic plasticity10,11, medullary respiratory rhythm generation12, and respiratory rhythm facilitation in the preBötzinger complex13,14. Fractalkine modulates activity-dependent synaptic transmission via factors such as microglia-dependent increases in extracellular ATP and/or adenosine3,15,16. However, the role of microglia in regulating any form of spinal, motor, or activity-independent synaptic plasticity is unknown.

The neural system controlling breathing exhibits considerable neuroplasticity17. Spontaneous respiratory plasticity is of considerable importance when confronted with intrinsic or extrinsic physiological conditions (e.g., weight gain or loss), or with the onset of clinical disorders that compromise breathing, such as neurological and lung/chest wall disorders17,18. A powerful stimulus to respiratory plasticity is intermittent hypoxia, or intermittent exposure to low oxygen. Intermittent hypoxia elicits plasticity in the oxygen-sensitive carotid body chemoreceptors19,20, their brainstem integrating neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract21 or neurons critically involved in respiratory rhythm generation22,23,24. Intermittent hypoxia also elicits plasticity in the output neurons of the respiratory control system—respiratory (phrenic) motor neurons25,26. The phrenic motor system is located at cervical spinal segments 3-6, which provides innervation of the major inspiratory pump muscle, the diaphragm27,28,29.

The most extensively studied model of phrenic motor plasticity is known as phrenic long-term facilitation (pLTF), a persistent elevation in phrenic nerve activity lasting hours after exposure to 3, 5-minute episodes of moderate hypoxia (acute intermittent hypoxia; AIH). AIH elicits pLTF via distinct (but competing) cellular mechanisms, depending on the severity of hypoxic episodes within the AIH protocol30. Whereas AIH consisting of moderate hypoxic episodes (mAIH) elicits pLTF by a serotonin-dependent, adenosine-constrained mechanism, AIH consisting of severe hypoxic episodes (sAIH) elicits phenotypically similar pLTF by a distinct adenosine-driven and serotonin-constrained mechanism30,31,32,33. With intermediate hypoxia34 and pharmacological co-activation of the relevant cervical spinal serotonin (5-HT2) and adenosine (A2A) receptors, pLTF is canceled via powerful crosstalk inhibition35. Thus, the serotonin versus adenosine balance is a key regulator of AIH-induced phrenic motor plasticity.

While the relevant spinal serotonin is released from descending projections of brainstem raphe serotonergic neurons32, the cellular source of adenosine is unknown. Here we tested the hypothesis that AIH triggers phrenic motor neuron-microglial interactions mediated by fractalkine signaling that regulate the serotonin/adenosine balance and, thus, phrenic motor plasticity. Specifically, we tested the idea that, during hypoxic episodes, phrenic motor neuron Fkn activates microglial Fkn receptors (CX3CR1)—the lone cell type known to express CX3CR1 in the healthy CNS. In response, microglia increase the conversion of ATP to adenosine, increasing extracellular adenosine concentration. Thus, phrenic motor neuron-microglia interactions regulate the local serotonin/adenosine balance via reciprocal Fkn/CX3CR1-adenosine signaling. We demonstrate that: 1) cervical spinal Fkn is sufficient to drive phrenic motor plasticity by evoking local adenosine formation/accumulation; 2) microglia constrain mAIH-induced pLTF due to hypoxia-evoked adenosine accumulation, or (with sufficient adenosine accumulation) drive sAIH-induced, adenosine-dominant pLTF; 3) cervical spinal microglial CX3CR1 activation is necessary for sAIH-induced pLTF, but constrains mAIH-induced pLTF; and 4) the relevant Fkn protein is within phrenic motor neurons per se. Thus, through interactions with nearby microglia, phrenic motor neurons indirectly regulate the magnitude and mechanism of their own plasticity.

Results

Fkn increases extracellular adenosine levels and elicits phrenic motor facilitation

We first tested whether spinal Fkn receptor activation near the phrenic motor nucleus is sufficient to increase spinal extracellular adenosine levels. Fkn protein was delivered via intrathecal injection to the C4 cervical spinal cord segment in anesthetized, paralyzed and ventilated rats; changes in cervical spinal extracellular adenosine concentration were measured via adenosine and inosine microbiosensors (Fig. 1A). Phrenic nerve activity increased in a dose-dependent manner in response to intrathecal Fkn injections (see Supplementary Fig. 1; for details concerning experimental preparation or adenosine measurements, see Methods or36,37,38). Intrathecal Fkn injections (100 ng) slowly increased in vivo spinal extracellular adenosine concentration over ~30 min (p < 0.001; Fig. 1B). Concurrent blood gas measurements verified that rats remained well oxygenated (arterial PO2 = 291 ± 13 mmHg) and isocapnic (arterial PCO2 = 44.8 ± 0.5 mmHg) during recordings.

A Schematic of experimental setup with intrathecal drug delivery and placement of adenosine (ADO) and inosine (INO) micro-biosensors. B Intrathecal fractalkine (Fkn; 100 ng; 12 μL) delivery evoked a slow increase in extracellular adenosine concentration over 30 min (n = 3 independent recordings from 3 rats; Linear Regression ANOVA: *p < 0.001; r = 0.993, r2 = 0.986, Adjusted r2 = 0.986). Concurrently, phrenic nerve activity was recorded in urethane anesthetized rats maintained at baseline conditions during and after intrathecal Fkn injection (90 min post-delivery). Ventilator volumes were set for each rat based on body mass (0.007 ml * body mass, g; 72–74 breaths per minute). Inspired CO2 or ventilator frequency was adjusted to maintain end-tidal PCO2 between 38 and 41 mmHg. Blood gas measurements were taken 2–3 times during the initial baseline, and at 30, 60, and 90-min post-drug (Supplementary Table 1). C Schematic of inter-cellular signaling highlighting where receptors/enzymes were blocked/inhibited in D–H. Representative compressed neurograms of integrated phrenic nerve activity are shown for rats that received (D) vehicle (VEH; time controls; n = 7 rats, each rat with 1 independent recording), E VEH + Fkn (n = 6 rats, each rat with 1 independent recording), (F) CX3CR1 inhibitor, AZD8797 + Fkn (n = 7 rats, each with 1 independent recording), G ATPase inhibitor, ARL67156 + Fkn (n = 7 rats, each with 1 independent recording), and H A2A Receptor inhibitor, MSX-3 + Fkn (n = 7 rats, each with 1 independent recording). I Phrenic burst amplitude (percent change from baseline; % baseline) was significantly increased 90 min post-Fkn administration (VEH + Fkn); however, CX3CR1, ATPase and A2A receptor inhibition (schematized in C) attenuated or prevented phrenic motor facilitation (F(4,29) = 21.378, p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA). *p < 0.001, significant differences vs all groups; Tukey post-hoc Test. Bars show mean ± SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Figures created in BioRender. Marciante, A. (2024) https://BioRender.com/e55f542.

To determine if Fkn-induced increases in extracellular adenosine concentration elicit phrenic motor facilitation, phrenic nerve activity was recorded in the same anesthetized rats (for details concerning experimental preparation, see Methods36,37,38). At 90 min post-injection, intrathecal Fkn significantly increased phrenic nerve burst amplitude 82.4 ± 8.7% above baseline and vs vehicle time controls (VEH; -0.2 ± 6.4%; p < 0.001; n = 6–7 independent recordings per group; Fig. 1D, E). Thus, Fkn receptor activation is sufficient to elicit phrenic motor facilitation.

We next tested the involvement of spinal receptors and enzymes in phrenic motor neuron-microglia Fkn/adenosine signaling to assess their role in fractalkine-induced phrenic motor facilitation (Fig. 1C). Indeed, Fkn receptor (CX3CR1) expression is virtually exclusive to microglia in cervical spinal tissue (Supplementary Fig. 2). Microglia are also the primary cells expressing the CD39 ecto-ATPase in cervical spinal tissue (Supplementary Fig. 3). Fkn (100 ng) was injected over the phrenic motor pool 30 min after pretreatment with either: (1) microglial CX3CR1 inhibitor (Fig. 1F); (2) ectonucleotidase inhibitor to determine if extracellular ATP is converted to adenosine (vs adenosine release per se39 Fig. 1G); or (3) A2A receptor inhibitor, a receptor necessary and sufficient for adenosine-driven phrenic motor plasticity40 (Fig. 1H).

Each inhibitor prevented development of significant phrenic motor facilitation 90 min post-Fkn delivery (CX3CR1 inhibition: 10.7 ± 7.8%; ATPase inhibition: 13.7 ± 3.3%; A2A receptor inhibition: 5.9 ± 7.9%; all p < 0.001 vs VEH + Fkn; Fig. 1I). Thus, Fkn receptor activation on cervical microglia is sufficient to elicit spinal neuroplasticity via a mechanism that requires conversion of ATP to adenosine and subsequent A2A receptor activation.

Spinal extracellular adenosine accumulation is dependent on hypoxia severity

Within 5-minute hypoxic episodes, arterial hypoxemia invades cervical spinal tissues, lowering tissue PO2 to an extent that depends on the severity and duration of hypoxemia41. We now demonstrate that the severity of hypoxemia within episodes (and tissue hypoxia) has a major impact on spinal adenosine accumulation (i.e., mAIH vs sAIH). Hypoxia-evoked extracellular adenosine accumulation in the ventral cervical spinal cord near the phrenic motor nucleus exhibited dose-dependent adenosine accumulation during moderate (PaO2 = 43 ± 2 mmHg) vs severe (PaO2 = 27 ± 0.8 mmHg) hypoxic episodes (n = 5 recordings per group made in 3 rats; Fig. 2A and B). Peak adenosine levels were significantly higher during severe vs moderate hypoxic episodes (severe: 7.4 ± 0.8 µM; moderate: 3.3 ± 0.2 µM; t(8) = −5.299, p < 0.001; unpaired t-test; Fig. 2C); when expressed as an area under the curve to reflect total adenosine accumulation during hypoxic episodes, adenosine accumulation during severe vs moderate hypoxic episodes remained elevated (severe: 32.2 ± 3.8 µM; moderate: 15.8 ± 0.7 µM; t(8) = −4.218, p = 0.003; unpaired t-test; Fig. 2D). Thus, hypoxia evokes dose-dependent spinal adenosine accumulation near phrenic motor neurons (F(3,6) = 229.816, p < 0.001; r = 0.9957, r2 = 0.9914; Fig. 2E). Pretreatment with a CX3CR1 antagonist suppressed adenosine accumulation during severe hypoxia (Supplemental Fig. 4), demonstrating that reciprocal fractalkine/adenosine signaling via microglial CX3CR1 activation is necessary for hypoxia-evoked adenosine accumulation.

A Adenosine/inosine probes were placed between ventral C3/C4 to measure changes in adenosine accumulation during hypoxia. B Average traces of extracellular adenosine concentration (µM) during 5 min of moderate (PaO2 = 42.7 ± 2.0 mmHg) or severe (PaO2 = 27.2 ± 0.8 mmHg) hypoxia (n = 5 independent recordings per group, collected in 3 rats). Measurements of technical replicates allowed appropriate ‘washout’ time between subsequent hypoxic exposures for extracellular adenosine to return to baseline levels, consistent with published data from our laboratory38. Measurements between biological and within technical replicates did not differentiate more than one standard deviation from each other (see Source Data). Greater adenosine accumulation was observed in severe hypoxic episodes when expressed as C peak adenosine level ([ADO]peak; t(8) = −5.299, p < 0.001; unpaired t-test, two-sided) or D total area under the curve ([ADO]AUC; t(8) = −4.218, p = 0.003; unpaired t-test, two-sided). E PaO2 strongly correlates with measured extracellular adenosine levels (F(1,14) = 206.099, p < 0.0001; nonlinear regression ANOVA; r = 0.9677, r2 = 0.9364, adjusted r2 = 0.9318; nonlinear regression). Adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. Bars are means ± SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Figures created in BioRender. Marciante, A. (2024) https://BioRender.com/e55f542.

Fractalkine signaling undermines moderate (serotonin-dominant) AIH-induced pLTF

Moderate AIH-induced phrenic long-term facilitation (pLTF) manifests as a persistent (and progressive) increase in integrated nerve burst amplitude lasting many hours after AIH has ended. Historically, the most frequently studied mAIH protocol35 consists of 3, 5-minute episodes of moderate hypoxia (arterial PO2 ~ 40-55 mmHg), with 5 minute intervals of control oxygen conditions (arterial PO2 > 150 mmHg)22,42,43. To test the idea that Fkn/CX3CR1 signaling and adenosine accumulation during moderate AIH suppresses pLTF (Fig. 3A), intrathecal Fkn was delivered prior to moderate AIH (100 ng in 12 µL). As predicted, intrathecal fractalkine, delivered 30 min before abolished moderate AIH-induced pLTF (−1.7 ± 5.1%; vs vehicle controls: 43.2 ± 5.4%; p < 0.001; n = 7–8 each group; Fig. 3C and E). With combined Fkn and moderate AIH, powerful crosstalk inhibition likely cancels phrenic motor facilitation due to balanced (and offsetting) serotonin and adenosine receptor signaling35.

Schematic of hypothesized mechanisms for intrathecal and hypoxia-evoked fractalkine (Fkn) release on moderate (A: serotonin-driven Q pathway) vs severe AIH-induced pLTF (B: adenosine-driven S pathway). Phrenic nerve activity was recorded in urethane anesthetized rats during baseline, during intrathecal drug administration, and for 90 min post-treatment while baseline conditions were maintained. Inspired CO2 and/or ventilator frequency was adjusted to maintain end-tidal PCO2 between 38 and 41 mmHg. Blood gas measurements were taken 2-3 times during the initial baseline, during the last minute of the first hypoxic episode, and at 30, 60, and 90 min post-AIH (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Raw integrated phrenic nerve amplitude at baseline and during maximal chemoreceptor stimulation (10% O2, 7% CO2, balance N2) delivered at the end of each experiment are included in Supplementary Table 3 to assess recording quality. C, D Representative compressed neurograms with corresponding scale bars of integrated phrenic nerve activity from rats that received vehicle (VEH; top row) or fractalkine (Fkn; bottom row) ~30 min prior to moderate (C; VEH: n = 7 rats, each with 1 independent recording; Fkn: n = 8 independent recordings from 8 rats) or severe (D; VEH: n = 7 rats, each with 1 independent recording; Fkn: n = 5 independent recordings from 5 rats) AIH. Immediately below each neurogram are individual, integrated (∫) phrenic nerve bursts taken during baseline and 90 min post-AIH. One-minute averages of phrenic nerve burst amplitude were measured at 90 min post-AIH, and are presented as percent change from the pre-AIH baseline value (E); there was a statistically significant interaction between drug (VEH vs Fkn) and AIH protocol (moderate vs severe) on pLTF (F(1,23) = 22.316, p < 0.001; two-way ANOVA). *p < 0.001; Tukey post-hoc Test. Bars are means ± SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Figures created in BioRender. Marciante, A. (2024) https://BioRender.com/e55f542.

Severe AIH consisting of 3, 5 min episodes of severe hypoxia (PaO2: 25-30 mmHg), with 5 min intervals of baseline oxygen conditions, elicits pLTF by an adenosine-dominant mechanism26,30. Thus, in contrast to moderate AIH, intrathecal Fkn does not significantly affect severe AIH-induced pLTF (102 ± 7%; n = 5; vs vehicle controls: 88 ± 7%; n = 7; p = 0.159; Fig. 3D, E), consistent with the idea that adding Fkn-evoked adenosine beyond the already high degree of A2A receptor activation with severe AIH supports versus inhibits plasticity (Fig. 3B). Thus, the same treatment (i.e., Fkn protein) undermines serotonin-driven, but not adenosine-driven pLTF.

Microglia differentially regulate moderate vs severe AIH-induced pLTF

Although multiple cell types potentially generate extracellular ATP/adenosine during hypoxia, the source of spinal adenosine relevant to pLTF has not been previously studied. Here, we demonstrate that microglial ablation and/or CX3CR1 receptor inhibition on spinal microglia have similar effects on phrenic motor plasticity. First, cervical spinal CX3CR1 inhibition enhanced moderate (serotonin-dominant) but attenuated severe (adenosine-dominant) AIH-induced pLTF. Selective CX3CR1 inhibitors (AZD8797 or JMS-17-2) were delivered intrathecally ~30 min prior to moderate (Fig. 4A) or severe AIH (Fig. 4B) to antagonize cervical spinal fractalkine receptors. While severe AIH-induced pLTF is typically more robust than moderate AIH-induced pLTF, cervical spinal CX3CR1 inhibition significantly increased moderate AIH-induced pLTF (AZD8797: 82 ± 5% and JMS-17-2: 101 ± 21%, respectively) vs vehicle controls (43 ± 5%; n = 4–7 each group; p = 0.011 & p = 0.001, respectively). In contrast, cervical spinal CX3CR1 inhibition abolished severe AIH-induced pLTF (AZD8797: 1 ± 6% and JMS-17-2: 2 ± 2%, respectively) vs vehicle controls (88 ± 7%; n = 5–7 per group; both p < 0.001; Fig. 4C). Findings with both receptor antagonists are consistent with the idea that cervical spinal CX3CR1 inhibition reduces extracellular adenosine accumulation during hypoxic episodes (Supplementary Fig. 4).

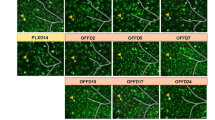

A, B Representative individual, integrated (∫) and raw phrenic (Phr) nerve bursts during baseline and 90 min post-AIH from a vehicle (VEH) control (top row), spinal CX3CR1-inhibited (CX3CR1i) rat using AZD8797 or JMS-17-2, and PLX3397-treated rat (bottom row) prior to moderate (mAIH; A) or severe AIH (sAIH; B). One-minute averages of phrenic nerve burst amplitude were measured 90 min post-AIH and are presented as percent change from baseline (C). There was a statistically significant effect of the drug (VEH vs AZD8797 or JMS-17-2 or PLX3397) on pLTF following moderate AIH (top; n = 4 rats, each with 1 independent recording per group (PLX3397 and JMS-17-2); or 7 rats, each with 1 independent recording per group (VEH and AZD8797); F(3,18) = 9.724, p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA) or severe AIH (bottom; n = 5 rats, each with 1 independent recording (JMS-17-2) or 6 rats, each with 1 independent recording (PLX3397); or 7 rats, each with 1 independent recording per group (VEH and AZD8797); F(3, 21) = 49.34, p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA); *p < 0.050, significant differences (vs VEH controls; moderate: AZD9797, p = 0.011; JMS-17-2, p = 0.002; PLX3397, p = 0.041; severe: all groups p < 0.0001; Tukey post-hoc Test). D Schematic outlining region of the ventral horn where microglia were counted after VEH (spinal tissue from n = 5 rats per group with at least 10 sections per rat) or PLEX3397 (spinal tissue from n = 6 rats per group with at least 10 sections per rat) treatment. Representative confocal microscope images from VEH control (E) and PLX3397-treated rats (F) stained for Iba-1 positive microglia (magenta) and phrenic motor neurons (CtB; green). Scale bar (left; 10x magnification): 150 µm; scale bar (right; 40x magnification): 50 µm. G Ventral horn Iba-1 positive microglia were counted using a custom code (see “Code Availability” section); Iba-1 positive microglia counts were significantly reduced in spinal cords of PLX3397-treated rats (spinal tissue from n = 6 rats per group with at least 10 sections per rat) versus controls that did not receive PLX3397 (spinal tissue from n = 5 rats per group with at least 10 sections per rat; t(9) = 8.347, p = 0.00002; unpaired t-test, two-sided). Bars are means ± SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Figures created in BioRender. Marciante, A. (2024) https://BioRender.com/e55f542.

Several cell types (e.g., microglia, astrocytes and/or neurons) could release ATP and/or adenosine during hypoxia and contribute to increased extracellular adenosine levels. To determine if microglia per se are necessary for the hypoxia-evoked adenosine increase, microglia were ablated by treating rats with the colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF1) receptor inhibitor PLX339744. CSF1 receptor signaling is required for microglial survival45. After 10 days of PLX3397 administration (80 mg/kg/day via syringe-feeding), microglial depletion was verified via computer-assisted counting of Iba-1 positive cells using a custom code (see “Code Availability” section) in cervical ventral horn (C3-C6; the region containing the phrenic motor nucleus; Fig. 4D-F). Iba-1 positive cells were counted only if they colocalized with nuclear DAPI staining. Indeed, Iba-1 positive microglia counts were significantly reduced in PLX3397-treated rats (to 13 ± 3% of control; n = 5-6 per group; t(9) = 8.347, p = 0.00002; unpaired t-test; Fig. 4G). Moderate (serotonin-dominant) AIH-induced pLTF increased nearly 2-fold in PLX3397-treated rats (77 ± 2%; n = 4; vs vehicle controls; p = 0.041; Fig. 4C). In contrast, severe (adenosine-dominant) AIH-induced pLTF was reduced 4-fold in PLX3397-treated rats (18 ± 6%; n = 6; vs vehicle controls; p < 0.001; Fig. 4C). Thus, microglial CX3CR1 inhibition and selective microglial ablation both shift the balance towards serotonin- vs adenosine-dominant plasticity.

Phrenic motor neurons are the relevant source of fractalkine for phrenic motor plasticity

Fractalkine is abundantly expressed in CNS neurons and is produced by/released from those neurons during hypoxia5,7,9,46. While dorsal horn neurons are known to express Fkn4,47, reports of Fkn expression in alpha motor neurons are limited. Here, we demonstrate phrenic (and non-phrenic) motor neurons in the ventral cervical spinal cord express Fkn protein48(Supplementary Fig. 5). However, it is uncertain if the relevant fractalkine for microglial regulation of AIH-induced pLTF originates within phrenic motor neurons per se vs other neurons. Thus, small interfering RNAs (siRNA) targeting fractalkine mRNA (siFkn) or a non-targeting sequence (controls; siNTg) were delivered to phrenic motor neurons via intrapleural injections at the 5th intercostal space along the anterior axial line on 3 consecutive days as described by others49,50,51. Intrapleural siRNA pools with the Accell modification (Dharmacon) are taken up by phrenic motor neuron axon terminals and retrogradely transported to their cell bodies where they selectively knock-down target mRNA (and protein)49,50,51,52 (Fig. 5A). One day after the final siRNA injection, rats were prepared for in vivo recordings of phrenic nerve activity and exposed to moderate or severe AIH. Phrenic motor neuron fractalkine knockdown via siRNAs significantly increased serotonin-dominant moderate AIH-induced pLTF (104 ± 7 %; n = 7) vs siNTg controls (55 ± 5%; n = 4; p = 0.002, Tukey post-hoc Test; Fig. 5B–D), consistent with reduced adenosine constraint of serotonin-driven pLTF. In contrast, severe AIH-induced (adenosine-dominant) pLTF was attenuated by siFkn (22 ± 9%; n = 7) vs siNTg controls (102 ± 16%; n = 4; p < 0.001, Tukey post-hoc Test). There was a significant interaction between siRNA (siFkn or siNTg) and AIH protocol on pLTF expression (F(1,18) = 45.431, p < 0.001).

A Schematic depicting intrapleural injections for retrograde siRNA transport (nontargeting controls, siNTg; rat CX3CL1/fractalkine, siFkn) and CtB to phrenic motor neurons. Representative individual, integrated (∫) and raw phrenic (Phr) nerve bursts taken during baseline and 90 min post-AIH from siNTg- (top row) and siFkn-injected rats (bottom row) prior to moderate (mAIH; B) or severe AIH (sAIH; C). One-minute averages of phrenic nerve amplitude were measured 90 min post-AIH, and are presented as percent change from baseline (D); there was a statistically significant interaction between siRNA (siNTg vs siFkn) and AIH protocol (moderate vs severe) on pLTF (siNTg: n = 4 rats each with 1 independent recording per group; siFkn: n = 7 rats, each with 1 independent recording per group; F(1,18) = 45.431, p < 0.001; two-way ANOVA). *p < 0.01 (siNTg vs siFkn: moderate, p = 0.002; severe, p < 0.001; mAIH vs sAIH: siNTg, p = 0.006; siFkn, p < 0.001; Tukey post-hoc Test). E Representative confocal microscope image of cervical ventral horn; phrenic motor nucleus circled; phrenic motor neurons identified with CtB (green); scale bar (10x magnification): 150 µm; spinal tissue from n = 10 rats. F Representative confocal microscope images from siNTg (left) and siFkn (right)-injected groups stained for CtB (green) and Fkn mRNA (red); scale bar (40x magnification): 20 µm; spinal tissue from n = 5 rats per group. G Fkn mRNA fluorescence intensity was significantly reduced in siFkn vs siNTg phrenic motor neurons (spinal tissue from n = 5 rats per group, at least 10 sections per rat; t(8) = 4.812, p = 0.001; unpaired t-test, two-sided). H Fractalkine mRNA fluorescent intensity in non-phrenic motor neurons was similar between siNTg and siFkn groups (t(8) = 0.542, p = 0.602; unpaired t-test, two-sided). Bars are means ± SEM. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Figures created in BioRender. Marciante, A. (2024) https://BioRender.com/e55f542.

Phrenic motor neuron Fkn mRNA knockdown was verified after in vivo neurophysiology experiments had been completed via fluorescent in situ hybridization. Phrenic motor neurons were identified in the cervical spinal cord via intrapleural injections of cholera toxin B fragment (CtB) to retrogradely label phrenic motor neurons (Fig. 5E). Abundant Fkn mRNA was observed in the nucleus and cytoplasm of all quantified (CtB-labeled) phrenic motor neuron somata (n = 50 ± 4 phrenic motor neurons per rat; Fig. 5F). Fkn mRNA was quantified within CtB‐labeled phrenic motor neurons for siNTg and siFkn rats; fluorescence intensity at the phrenic motor nucleus was reduced nearly 60% in siFkn vs siNTg treated rats (t(8) = 4.812, p = 0.001; unpaired t-test; Fig. 5G). To determine if siFkn affected Fkn expression in other cells, fluorescent intensity was measured in nearby non‐phrenic motor neurons, detected as large ventral horn cells (>300 μm2); no changes in fluorescence intensity could be appreciated in these cells (t(8) = 0.542, p = 0.602; unpaired t-test; Fig. 5H), consistent with prior reports of selective intrapleural siRNA delivery to phrenic motor neurons49,51. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that the relevant Fkn regulating AIH-induced phrenic motor plasticity is within phrenic motor neurons per se, demonstrating a means through which phrenic motor neurons regulate their own plasticity.

Discussion

We demonstrate that spinal microglia regulate the magnitude and mechanism of phrenic motor plasticity. We propose an intercellular model of reciprocal phrenic motor neuron-microglial interactions initiated by hypoxia-evoked phrenic motor neuron Fkn to microglial Fkn receptor signaling (Fig. 6). During AIH, phrenic motor neuron Fkn (CX3CL1) activates Fkn receptors (CX3CR1) on nearby microglia, triggering the conversion of extracellular ATP to adenosine. Depending on the severity of hypoxic episodes within the AIH protocol, hypoxia-evoked adenosine formation either constrains serotonin-driven pLTF or evokes pLTF by a distinct, adenosine-driven mechanism. Our demonstration that spinal microglia regulate hypoxia-evoked respiratory motor plasticity has important implications for ongoing translational efforts to harness AIH as a therapeutic modality to restore breathing and non-respiratory motor functions in clinical disorders that compromise breathing and other movements, such as spinal cord injury, ALS and multiple sclerosis18,53,54,55.

Hypoxia triggers phrenic motor neuron Fkn signaling in a hypoxia dose-dependent manner. Fkn binds to its receptor, CX3CR1, on nearby microglia, triggering microglia-dependent formation and accumulation of extracellular adenosine (ADO). ADO activates phrenic motor neuron adenosine 2A (A2A) receptors, constraining the serotonin-dominant (Q) pathway to pLTF during moderate hypoxia (left). In contrast, severe hypoxia, and greater extracellular adenosine accumulation, shifts the serotonin/adenosine balance sufficiently to drive the adenosine-dominant S pathway to pLTF (right). Figures created in BioRender. Marciante, A. (2024) https://BioRender.com/e55f542.

Fkn-adenosine signaling between phrenic motor neurons and microglia regulates spinal neuroplasticity

In other regions of the CNS, there is growing awareness that neuron/glia interactions regulate activity-dependent synaptic plasticity. Both astroglia and microglia regulate brain plasticity in healthy animals56,57,58. The microglial activity also has complex effects on IH-induced respiratory rhythm facilitation of the preBötzinger complex in vitro13. Here, we extend these principles to the spinal cord, specifically to the final common pathway—the alpha motor neurons.

Reciprocal Fkn-adenosine signaling between phrenic motor neurons and microglia has opposite effects on AIH-induced phrenic motor plasticity depending on a single variable: the severity of hypoxic episodes. Although mechanisms whereby hypoxia increases Fkn activation or release are unknown, it could require: (1) increased glutamatergic synaptic input and/or increased phrenic nerve activity, (2) activation of serotonin receptors on phrenic motor neurons (independent of motor neuron activity), and/or (3) hypoxia itself may directly trigger Fkn release and/or activation (e.g., via increased proteases/caspase activity that cleaves Fkn, enabling its release).

Another significant finding is that principles based on studies of hippocampal activity-dependent synaptic plasticity59,60,61 differ from activity-independent, serotonin-induced pLTF35,62,63. Although an important trigger for plasticity in cognitive learning and memory is the temporal association of pre- and post-synaptic neuron activity (i.e. activity-dependent synaptic plasticity or Hebbian plasticity), similar activity-driven plasticity would in fact be maladaptive in the context of breathing since breathing is produced by constitutively active neurons that routinely change activity in response to physiological stimuli such as exercise, sleep or conscious input35. For example, ersistent changes in breathing following exercise would disrupt blood gas homeostasis at rest after metabolic rate returns to resting values, highlighting the need to minimize activity-dependent synaptic plasticity in the respiratory motor system. Consequently, respiratory plasticity is more often triggered by alternative stimuli, including specific neurochemicals or neuromodulators35. Indeed, the phrenic motor system exhibits greater plasticity with reduced versus enhanced activity or with serotonin/adenosine-induced, activity-independent plasticity35. Collectively, data presented here demonstrate that reciprocal phrenic motor neuron-microglia signaling has complex effects on activity-independent, AIH-induced phrenic motor plasticity, depending on the severity of hypoxic episodes (Fig. 6).

Perhaps the most significant finding of this study is that phrenic motor neurons regulate their own plasticity via interactions with nearby microglia. Fkn knockdown within phrenic motor neurons demonstrates that these neurons contain the relevant Fkn mRNA and protein. Although motor neuron-microglia interactions differentially impact plasticity elicited by moderate (suppression) vs severe AIH (activation), the apparent complexity can be explained by dose-dependent adenosine accumulation, biasing a system characterized by competing serotonin vs adenosine-dependent mechanisms of plasticity35; each mechanism competes for dominance via powerful and mutual cross-talk inhibition. Even subtle shifts in the adenosine vs serotonin balance can profoundly impact the magnitude and mechanism of plasticity25,35,38.

Moderate hypoxia rapidly activates carotid chemo-afferent neurons that project to and activate brainstem circuits, including raphe serotonergic neurons that project to the phrenic motor nucleus64. There, serotonin type 2 receptor activation initiates intracellular signaling cascades giving rise to pLTF32,37,63. Spinal tissue hypoxia evolves more slowly during hypoxic episodes of the AIH protocol36,65 and evokes the extracellular adenosine accumulation38 that constrains serotonin-driven plasticity via phrenic motor neuron A2A receptor activation32,66. The intracellular signaling cascades initiated by Gq-coupled serotonin 2 vs Gs-coupled A2A receptors are distinct25,26, other than their crosstalk interactions33,52,67. Thus, by shifting the serotonin/adenosine balance, microglia regulate the magnitude and even dominant mechanism of pLTF25,30,40,68. Whereas modest adenosine accumulation during moderate hypoxia constrains serotonin-dominant pLTF, greater adenosine accumulation during severe hypoxic episodes tips the balance towards adenosine-dominant plasticity30,49,69. Consequently, cervical spinal A2A receptor inhibition enhances moderate AIH31 but virtually blocks severe AIH-induced pLTF30.

While other adenosine receptors may also have effects in the cervical spinal cord, our findings support prior data from our laboratory and others, indicating that the A2A receptors are the primary adenosine receptor subtype driving sAIH-induced pLTF. Whereas A1 and A2A receptors have similar affinities for adenosine70, A1 receptor antagonism does not affect ventilatory LTF in normal rats71. Further, A1 receptors inhibit intracellular cAMP accumulation (i.e., Gi/o-coupled) whereas A2A receptors promote cAMP accumulation (i.e., Gs-coupled). Thus, A1 receptors would have opposite effects from A2A. Other adenosine receptors, such as A2B and A3, have significantly lower affinities for adenosine (~5000–6000 fold)70; therefore, it is unlikely they would play a significant role in experiments reported here. The present study demonstrates that reciprocal phrenic motor neuron/microglial Fkn/adenosine signaling within the phrenic motor nucleus is a critical regulator of the magnitude and mechanism of AIH-induced phrenic motor plasticity. Since the source of relevant Fkn is the phrenic motor neurons per se (Fig. 5), these motor neurons indirectly regulate their own plasticity in response to AIH.

Spinal Fkn receptor activation modulates local extracellular adenosine levels

In the central nervous system, Fkn is synthesized predominantly by neurons, whereas its receptor (CX3CR1) is expressed almost exclusively by microglia7,8,9 (Supplementary Fig. 2). By activating microglial Fkn receptors, Fkn initiates the neuron-microglia communication that: (1) coordinates inflammatory responses and suppresses overproduction of microglial pro-inflammatory factors72,73; (2) stimulates microglial migration towards neurons9,74,75; (3) regulates hippocampal synaptic plasticity10,11; and (4) modulates breathing12. We extend these concepts by demonstrating Fkn regulates spinal cord extracellular adenosine levels.

Intrathecal Fkn administration (without hypoxia) elicits a slowly developing form of phrenic motor facilitation, accompanied by a steady increase in extracellular adenosine concentration (Fig. 1). Our interpretation is that, whereas hypoxia elicits rapid and localized Fkn release and microglial CX3CR1 receptor activation (Figs. 3 and 4), exogenous Fkn protein must diffuse from the subdural space to microglia within the phrenic motor nucleus, producing a slow time course that is an artifact of intrathecal protein delivery, similar to other proteins (e.g., BDNF)76. This kinetic likely differs from small molecule diffusion, which can reach the ventral cervical spinal targets within a relatively short duration, or local release from phrenic motor neurons under the influence of hypoxia.

Spinal CX3CR1 inhibition blunts hypoxia-evoked extracellular adenosine accumulation (Supplemental Fig. 4) as well as sAIH-induced adenosine-dominant pLTF and enhances mAIH-induced, serotonin-dominant pLTF (Fig. 3). To further demonstrate microglial cells themselves regulate AIH-induced plasticity, microglial ablation with the CSF1 receptor inhibitor PLX3397 mimics Fkn receptor inhibition. Thus, microglia per se mediate bidirectional Fkn/CX3CR1 regulation of phrenic motor plasticity in moderate vs severe hypoxia, consistent with their postulated role as adenosine donors that constrain (mAIH) or enhance (sAIH) pLTF in a dose-dependent manner.

In the microglial BV2 cell line, adenosine accumulates in the media following Fkn receptor activation2, consistent with our hypothesis that microglia convert ATP to adenosine in response to Fkn receptor activation via microglial ectonucleotidases. Microglia express 2 membrane-bound ectonucleotidases: CD39 (converts ATP to ADP or AMP) and CD73 (converts AMP to adenosine)77. We verified that cervical spinal microglia are the primary cell type expressing both CX3CR1 and CD39 (Supplemental Figs. 2 and 3), and Fkn-induced phrenic motor plasticity is impaired by an ecto-ATPase inhibitor, suggesting increased adenosine results from microglial ATPase activity (Fig. 1). However, the specific cells contributing to extracellular ATP (vs adenosine) accumulation is unclear.

Fkn within phrenic motor neurons regulates phrenic motor plasticity

An important finding of our study is that RNA interference and Fkn knockdown within phrenic motor neurons impacts mAIH and sAIH-induced pLTF in a manner similar to spinal CX3CR1 inhibition, A2A receptor inhibition and microglial ablation. Although non-phrenic motor neurons and interneurons also express Fkn, Fkn mRNA and protein knockdown within phrenic motor neurons per se: (1) enhances serotonin-dominant, mAIH-induced pLTF; and (2) attenuates adenosine-dominant, sAIH-induced pLTF. Since rats have only ~500 to 600 phrenic motor neurons amidst >3 million cells in C3-C5 spinal segments28,78,79, the impact of phrenic motor neuron Fkn knock-down clearly demonstrates that these neurons play a key role in regulating their own plasticity.

Microglia are key regulators of extracellular adenosine levels

Fractalkine/CX3CR1 signaling is an important regulator of hippocampal synaptic plasticity2,3,80,81. Differential microglial release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL6, TNFα, IL1β), as well as BDNF in ventral vs dorsal hippocampus, is associated with reduced dorsal and increased ventral LTP80, and can affect long-lasting neuroplasticity in the spinal dorsal horn82, suggesting complexity similar to our findings with spinal phrenic motor plasticity. With impaired CX3CR1 signaling, hippocampal LTP can be restored by IL1β receptor antagonists83. Whereas these studies suggest microglial cytokines could mediate Fkn effects on activity-dependent hippocampal LTP, reciprocal motor neuron/microglia signaling requires Fkn-induced adenosine accumulation to regulate phrenic motor plasticity. However, since mAIH-induced pLTF requires cervical spinal serotonin 2 receptor-dependent BDNF synthesis76, which activates TrkB receptors within phrenic motor neurons per se51, the potential of microglia-derived BDNF to modulate pLTF is worthy of future exploration.

We previously reported that mild systemic inflammation abolishes mAIH-induced pLTF by an adenosine-dependent mechanism84. However, since astroglia and microglia both mediate CNS pro-inflammatory responses85,86,87, the specific inflammation-activated cells undermining pLTF are not known. Our finding that healthy microglia regulate phrenic motor plasticity via adenosine-dependent mechanisms suggests that mild systemic inflammation may also act via microglial activation37.

Several cell types including microglia, astrocytes and neurons likely release ATP during hypoxia and contribute to increased extracellular adenosine levels88,89. We did not directly investigate the involvement of astrocytes or neurons in extracellular ATP accumulation; however, CX3CR1 and ecto-ATPases (specifically CD39) are highly enriched in microglia vs astrocytes or neurons (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). Virtually all spinal cord cells expressing CX3CR1 and more than 70% of cells expressing CD39 are microglia; the remaining CD39-positive cells are GFAP-positive (i.e., putative astrocytes), leaving open the possibility that they play some role in converting ATP to adenosine. In support of the primary role of microglia in producing adenosine, microglial ablation with PLX3397 had similar effects to CX3CR1 and A2A receptor inhibition on mAIH- and sAIH-induced phrenic LTF30,31, indicating that microglia are key regulators of phrenic motor plasticity.

While manipulating microglial CX3CR1 via knock-down or knock-out approaches (vs pharmacological CX3CR1 inhibition or microglial ablation) is of interest, options are limited in rats. Currently, CX3CR1 knockout models are available only for mice. Unfortunately, studies of phrenic motor plasticity in mice are difficult due to the need for precise control of arterial blood gases to enable distinctions between changes in chemoreflex feedback vs phrenic motor plasticity per se. While there are ways to knock down CNS microglia mRNAs using recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) technologies, the architecture of the rat spinal cord makes efficient delivery of rAAV vectors throughout the neuraxis challenging, requiring rAAV intraspinal delivery at birth90. Such experiments would suffer from the fact that manipulations of microglial CX3CR1 throughout development have profound (off-target) biological effects. For example, developmental CX3CR1 knockout causes motor dysfunction91, impairs neuroplasticity83, and contributes to multiple neuronal defects resulting from deficient microglial development and function92. These off-target biological effects would make interpretation of such studies difficult. Regardless, the methods used in this study should be adequate since (1) microglia are virtually the only cell type expressing CX3CR1 in the cervical spinal cord (Supplementary Fig. 2); (2) two CX3CR1 antagonists affected pLTF similarly despite their different mechanisms of action (Fig. 4); and (3) microglial ablation mimics CX3CR1 or A2A receptor30,31 inhibition (Fig. 4).

In conclusion, despite serving as CNS resident immune cells, microglia also play key roles in non-innate immune functions essential for normal CNS functions. For example, we demonstrate here that spinal microglia regulate plasticity in phrenic motor neurons via reciprocal Fkn and adenosine signaling between phrenic motor neurons and nearby microglia. This regulatory feed-back loop impacts plasticity in a hypoxia dose-dependent manner. Collectively, the findings reported here advance our fundamental understanding of phrenic motor plasticity, an activity-independent form of synaptic plasticity. The regulation of phrenic motor plasticity is not cell-autonomous, and requires interactions between (incoming) raphe neurons, nearby microglia and phrenic motor neurons35. Understanding the regulation of AIH-induced phrenic motor plasticity may accelerate the translation of AIH as a therapeutic modality to preserve/restore breathing (and non-respiratory movements) in severe neurological conditions that often end life due to respiratory failure, including cervical spinal cord injury, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and other disorders including multiple sclerosis, stroke and traumatic brain injury18.

Methods

Animals

All procedures were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol #: 202110316). Experiments were performed on young adult (3-4 months; 395 ± 5 g) male Sprague-Dawley rats (208A Colony, Envigo; IN, USA). Rats were housed in pairs at 24°C with a 12/12 light/dark cycle (lights on: 07:00; lights off: 19:00) with access to food and water ad libitum. All rats underwent a 14-day acclimation period prior to experiments. Sample size estimation was based on power analysis of previous studies31,37,38,41,67,93,94,95 and extensive experience with all experimental procedures.

Surgical Preparation

Neurophysiology experiments were performed as described below and in prior studies using this same experimental preparation30,31,38,96,97. Rats were induced with 2.5-3.0% isoflurane in oxygen in a plexiglass chamber and transferred to a heated surgical table where anesthesia was continued (2.5–3.0% isoflurane; 60% oxygen, balance nitrogen). Body temperature was monitored via rectal thermometer (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and maintained at 37.5 ± 1.0°C during experiments. A polyethylene catheter (i.d. 1.67 mm; PE 240; Intramedic, MD) was inserted into the trachea via mid-line neck incision, and rats were mechanically ventilated (0.07 mL/10 g bw/ breath; 72 breaths/min; VentElite small animal ventilator; Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA). End-tidal PCO2 was monitored throughout the experiment with a breathethrough capnograph with sufficient response time to monitor true end-tidal PCO2 in rats (Capnogard, Novametrix, Wallingford CT). The inspired CO2 fraction was adjusted as needed to keep end-tidal PCO2 within pre-determined levels.

Anesthesia was slowly converted to urethane via slow infusion into a tail vein catheter (1.8 g/kg at 6 mL/h; 24 gauge, Surflo, Elkton, MD), while progressively decreasing inspired isoflurane concentration 0.5% every 6 min. Anesthetic depth was verified by lack of physiological response to toe-pinch; supplemental anesthetic was infused if required. Rats were bilaterally vagotomized at the mid-cervical level to prevent phrenic nerve entrainment with the ventilator. The right femoral artery was isolated and cannulated with polyethylene tubing (i.d. 0.58 mm; PE 50; Intradermic, MD) to monitor blood pressure (TA-100 Transducer Amplifier, CWE, Inc.) and sample blood gases (PaO2, PaCO2, pH, base-excess and hemoglobin concentration) with a blood gas analyzer (ABL 90 Flex, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark). Once the conversion to urethane anesthesia was complete, intravenous fluids were administered to maintain fluid and acid-base balance (1.5 mL/h; started ~1 h after the beginning of surgery, or ~20 min after conversion to urethane was complete85; 1:4 of 8.4% Na2CO3 in lactated Ringer’s solution). Rats were then given neuromuscular block with pancuronium bromide (2 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Spinal adenosine and inosine measurements

In separate rats (n = 5), a dorsal midline incision was made from the base of the skull to the fifth cervical segment. Muscle layers were retracted to expose C3–C5 vertebrae. A laminectomy was performed at the C4 vertebrae. Extracellular changes in adenosine concentration were measured via differential enzymatic detection using adenosine and inosine micro-biosensors (Zimmer-Peacock, UK) positioned ∼1 mm lateral to the spinal midline between C3 and C4 (∼1.5 mm depth from dorsal root entry zone) as previously described38. Coordinates were obtained from previous studies98. A longitudinal cut was made in the dura to enable micro-biosensor insertion ~3–4 mm apart from each other on the same side of the spinal cord. Extracellular adenosine concentration was measured: (1) for 30 min following intrathecal Fkn protein (100 ng) delivery; or (2) during 5 min moderate (PaO2 = 40–55 mmHg) or severe (PaO2 = 25–30 mmHg) hypoxic episodes. Signals were acquired at 1 Hz and converted to concentrations via 3-point calibration. Measurements began ∼30–45 min after probe insertion. At the end of experiments, the adenosine biosensor was retracted from the spinal cord and immediately placed in a calibration chamber containing buffer solution. The signal obtained following exogenous adenosine delivery to the chamber (10 µM), measured in nanoamperes, was used to scale the adenosine signal (assuming linear response)38,99.

Neurophysiological experiments

Intrathecal drug delivery

A laminectomy was performed at the C2 vertebrae for intrathecal drug delivery. A small hole was cut in the dura near the junction of the C2 and C3 segments, and a flexible silicone catheter (O.D. 0.6 mm; Access Technologies) was advanced to the caudal end of C3. A 50 µL Hamilton syringe containing the drug (see Drugs and Vehicles) was attached to the catheter for drug delivery. To prevent off-target effects of pharmacological manipulation, we used intrathecal drug injections directly at C4 to limit unintended drug distribution. For example, in an anatomically separated motor pool (hypoglossal), mAIH-induced hypoglossal LTF is unaffected by C4 intrathecal drug delivery31,32, at least with injection volumes less than 20 µL.

Electrophysiological Recordings

Using a dorsal approach, the left phrenic nerve was isolated, cut distally, and de-sheathed. Suction recording electrodes filled with 0.9% saline were placed in the saline-filled phrenic pocket and the nerve was suctioned with a syringe to record respiratory neural activity. Nerve activity was amplified (10K, A-M systems, Everett, WA), filtered (bandpass 300–5000 Hz), integrated (time constant, 50 ms), digitized (CED 1401, Cambridge Electronic Design, UK), and analyzed using Spike2 software (CED, version 8.20). The inspiratory phrenic activity served as an index of respiratory motor output.

Experimental Protocols

At least 45 min after full conversion to urethane anesthesia, the CO2 apneic and recruitment thresholds of phrenic nerve activity were determined by: (1) lowering inspired CO2 levels, or (2) increasing ventilation rate until rhythmic phrenic nerve activity ceased. After ~1 min, inspired CO2 levels were slowly increased until rhythmic respiratory activity resumed. Baseline conditions were established by raising end-tidal PCO2 ~ 2 mmHg above the recruitment threshold. After stable nerve activity was observed, blood samples were taken to document blood gas levels during baseline conditions. Arterial PCO2 was maintained isocapnic (±1.5 mmHg) with respect to baseline blood gas values by actively manipulating inspired CO2 concentration and/or ventilation rate. Baseline oxygen levels (60% oxygen, balance nitrogen, and carbon dioxide; PaO2 ≥ 150 mmHg) were maintained during experiments, except for hypoxic challenges (PaO2 = 40–55 mmHg). At the end of protocols, maximum chemoreflex activation was determined by delivering 7% CO2 and 10% O2 in N2 for ~3 min to ensure preparation stability and to assure sufficient dynamic range in phrenic nerve burst amplitude (see Supplement). At the end of the experiments, rats were euthanized by urethane overdose.

Drugs and vehicles

Drugs used include MSX-3 (A2A receptor antagonist; #M3568; Millipore Sigma), Recombinant Rat CX3CL1 protein (#537-FT-025; FisherSci), AZD8797 (CX3CR1 antagonist; #2255; Axon Medchem), JMS-17-2 (selective CX3CR1 antagonist; #HY-123918; MedChemExpress) and ARL67156 (selective ecto-ATPase inhibitor; #128310; FisherSci). Upon arrival, all drugs were dissolved in 100% DMSO or 0.9% saline based on solubility and manufacturer recommendations. Aliquots of stock solutions were kept frozen at −20 °C or −80 °C, depending on manufacturer recommendations. On the day of experiments, drugs were diluted in sterile 0.9% saline to achieve the desired concentration, except for JMS-17-2 which was diluted in corn oil100,101. DMSO-saline ratios were determined by drug solubility; a final concentration of 10% DMSO was sufficient to dissolve all drugs in vehicle solution. Most drugs were dissolved to final effective concentrations previously determined in our laboratory via published dose-response studies37 or dose-response curves reported in the Supplement. Based on these (and other) reports, intrathecal drug doses were as follows: 10 µM MSX-338,84,102, 100 ng Fractalkine protein, 10 µM AZD8797, 10 mM JMS-17-2100,101, and 1 mM ARL67156.

Microglia depletion

A group of rats was treated with Pexidartinib (PLX3397; MedKoo Biosciences, Morrisville, NC), a colony-stimulating factor 1 inhibitor. PLX3397 was formulated in DMSO, 1% PS80 and 0.5% hydroxycellulose. Rats were dosed at 80 mg/kg per day via syringe feeding (PLX3397 in DMSO formulation and liquefied Diet Gel; n = 12) for 10 days. Rats were prepared for in vivo neurophysiology one day after the final dose.

Phrenic Motor Neuron CtB and siRNA delivery

Intrapleural injections of the β‐subunit of cholera toxin (CtB; Millipore Sigma, #C9903) were performed similar to prior studies49,50,51,79. Cholera toxin B subunit (15 μl per side; 30 μl total per rat; 2 μg μl−1 in sterile H2O) was injected intrapleurally on each side using 25 μl Hamilton syringes at a depth of 6 mm through the fifth intercostal space anterior axillary line 14 days prior to tissue harvest. After 11 days, a pool of small interfering RNAs (siRNA; Dharmacon, Inc.) targeting CX3CL1 (siFkn) mRNA (n = 14) or a non-targeting sequence (siNTg; n = 8) were delivered intrapleurally. Each siRNA consisted of 4 pooled 21-nucleotide duplexes with symmetrical 3’ overhangs (Accell SMARTpool). Target sequences of the 4 duplexes in the Fkn/CX3CL1 siRNA pool were:

-

UUAUCAACAUGAAUAGUACA

-

GGUUGGACUUUGUUGGUUC

-

CCAUUUUGUAUUUUACUAA

-

UUUUCAAGCAUCAUUACCA

Fkn and non-targeting siRNA (siNTg) were suspended in siRNA Universal Buffer (Dharmacon) to yield a concentration of 5 μM. The siRNA stocks were aliquoted and stored at −20 °C. Prior to injection, stock siRNA solutions (26.8 μl/injection; 100 pmol) were combined with Oligofectamine (3.2 μl/injection) and incubated at room temperature (22–24 °C) for 15 min.

Rats were lightly anesthetized with isoflurane in a closed chamber followed by inhalation of isoflurane via nose cone (2.5–3.5% in 50% O2, balance N2). Using aseptic technique and a sterile, RNase-free 25 μl Hamilton syringe, siRNAs were injected intrapleurally at the fifth intercostal space along the anterior axial line49,50,51. Each rat received daily bilateral intrapleural injections of the appropriate siRNAs for 3 consecutive days. On the 4th day, rats were prepared for in vivo neurophysiology experiments.

In situ hybridization

Detection of Fkn/CX3CL1 mRNA using in situ hybridization was done to verify siRNA knockdown in phrenic motor neurons. On day 14, rats were anaesthetized under isoflurane anesthesia (4% in O2) and transcardially perfused with ice-cold RNase-free 1X phosphate buffered solution (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. Spinal segments C3-C5 were harvested and dehydrated in RNase-free 30% sucrose. Twenty micrometer sections were cut on a microtome and collected in 10–15 sets of serial C3-C5 sections in RNase-free PBS to obtain representative staining across segments C3-C5. Sections were mounted on to Superfrost Plus Gold microscope slides (ThermoFisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA). After drying at room temperature for ~2 h, slide-mounted tissue was stored at -80°C until use. All reagents used for in situ hybridization were purchased from Advanced Cell Diagnostics (Newark, CA). In situ hybridization was used for Fkn/CX3CL1 mRNA detection (reference no. 531141) using a fluorescence-based assay (reference no. 323110)103. Experimental protocols were performed according to the manufacturer instructions in RNAscope Multiplex Fluorescent Detection Reagents V2 (Document No. UM 323100, Advanced Cell Diagnostics).

Immunohistochemistry

After in situ hybridization experiments, immunohistochemistry for CtB and Iba-1 was done to detect labeling in phrenic motor neurons and activated microglia, respectively. Slides were rinsed 3 times in TBS, treated with blocking solution (10% donkey serum and 0.1% TritonX-100 in TBS) at room temperature for 1 hour, and then incubated in primary antibody, goat anti-CtB (1:1500; reference no. 227040, Millipore) and rabbit anti-Iba-1 (1:500; reference no. 019-19741, Wako) overnight at 4 °C. The following day, slides were washed in TBS three times and incubated in donkey anti-goat secondary antibody (1:1500; AlexaFluor 488, Jackson ImmunoResearch, reference no. 705-545-147) and donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1500; Cy5, Jackson ImmunoResearch, reference no. 711-175-152) for 2 hrs at room temperature. Slides were rinsed in TBS 3 times and coverslipped with ProLong Gold + DAPI antifade reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific). Immunohistochemistry for CtB and Iba-1 was similarly done following microglial depletion using PLX3397 to verify microglial knockdown in spinal C3-C6 ventral horn near the phrenic motor nucleus. Negative controls omitting either primary or secondary antibodies confirmed minimal nonspecific signal.

Imaging and acquisition

Slides were imaged using a fluorescence/brightfield microscope (BZ‐X710, Keyence Co., Osaka, Japan) with a 20x or 40x lens. Fkn mRNA was detected using a TexasRed filter (model no: OP‐87765); CtB immunolabelling was detected via a GFP filter (model no: OP‐87763). Iba1 immunolabeling was detected via a Cy5 filter (model no. OP-87766). DAPI was detected via a DAPI filter (model no: OP‐87762). The same light exposures were used for both groups (20X: 1/20 s, 1/25 s, 1/30 s and 1/200 s; 40X: 1/8.5 s, 1/3 s, 1/4 s and 1/12 s for Fkn mRNA, CtB, Iba1, and DAPI, respectively). Representative images were obtained with a confocal microscope (FV1000, Olympus Fluoview).

Image quantification

Fluorescence intensity was analyzed with QuPath Software (version 0.4.3) using images localized to the CtB‐labeled area of the ventral horn. The background intensity level was determined using the median value of a control region (i.e., near the central canal for each side). A threshold for each image was determined by constructing a pixel intensity histogram for each image and selecting a fixed percentile value across all images, as previously described49,103. The QuPath “wand” tool was used to annotate CtB-positive (phrenic motor neuron) and negative (non-phrenic) cells; cell nuclei were identified using DAPI. The fluorescence intensity of Fkn mRNA labeling was calculated as the average intensity of the CtB‐positive cells in each section and normalized to control region values. Intensities of individual non‐phrenic motor neurons were calculated as previously described49,103. Fkn labeling in non‐phrenic cervical motor neurons was measured to assess potential non‐specific effects.

Image analysis was performed using in-house code (MATLAB R2021b; Mathworks)104 to count microglia labeled with the fluorescent marker CY5 in images of rat spinal cord slices. The code reads in overlay images showing CY5-labeled microglia, performs background subtraction and thresholding to identify microglia somata, and counts the number of microglia in each image. Key parameters used in the analysis include (1) image resolution (0.75488 μm/pixel); (2) radius for selecting microglia somata (35 μm); (3) percentile threshold for CY5 intensity (99.0); and 4) expected soma size (100 pixels).

Data across all measured cells of all sections were averaged for each rat, representing the measured value for that animal. All imaging and image analysis was done by blinded assessors.

Statistical Analyses

Measurements of peak integrated phrenic burst amplitude and burst frequency (bursts/min) were assessed in 1 min bins immediately before each arterial blood sample at: baseline, during the last minute of the first hypoxic episode, 30, 60, and 90 min post-AIH, and during the final minute of the maximum chemoreflex challenge (Supplementary Table 3). Measurements were made at equivalent time points in time-matched control experiments. Integrated nerve burst amplitude was normalized by subtracting the baseline value, dividing the difference by the baseline value, and reporting percentage changes from the baseline. Burst frequencies were also normalized to baseline, expressed as an absolute difference in bursts per minute. All statistical comparisons between treatment groups for nerve burst amplitude (baseline and 90 min) were made using a 2- or 3-way ANOVAs with a repeated measures design. Individual comparisons were made using the Tukey post-hoc test.

Comparisons of mean arterial pressures and arterial PCO2 and PO2 (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2) were made at baseline, during hypoxia episode 1, 30, 60, and 90 min post-AIH using a 2-way mixed effects ANOVA to test if there was an effect of protocol with drug pretreatment. Unpaired t-tests were used to compare measurements of adenosine concentration during moderate (PaO2 = 40–50 mmHg) vs severe (PaO2 = 25–30 mmHg) hypoxic episodes.

Fkn/CX3CL1 mRNA in situ hybridization and microglia counts were compared using unpaired t-test. All statistics were analyzed in SigmaPlot v.12.0 or GraphPad v.10.3.1. Differences between groups were considered significant if p < 0.050. Data are presented as mean ± standard error mean (SEM).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Analysis code is available in GitHub repository104: https://github.com/ABMARCIANTE/microglia_count_coloc-code_only_CY5_pink.

References

Imura, Y. et al. Microglia release ATP by exocytosis. Glia 61, 1320–1330 (2013).

Lauro, C. et al. Activity of adenosine receptors type 1 Is required for CX3CL1-mediated neuroprotection and neuromodulation in hippocampal neurons. J. Immunol. 180, 7590–7596 (2008).

Piccinin, S. et al. CX3CL1-induced modulation at CA1 synapses reveals multiple mechanisms of EPSC modulation involving adenosine receptor subtypes. J. Neuroimmunol. 224, 85–92 (2010).

Camacho-Hernandez, N. P. & Pena-Ortega, F. Fractalkine/CX3CR1-dependent modulation of synaptic and network plasticity in health and disease. Neural Plast. 2023, 4637073 (2023).

Sheridan, G. K. & Murphy, K. J. Neuron-glia crosstalk in health and disease: fractalkine and CX3CR1 take centre stage. Open Biol. 3, 130181 (2013).

Szukiewicz, D. CX3CL1 (Fractalkine)-CX3CR1 Axis in inflammation-induced angiogenesis and tumorigenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25094679 (2024).

Nishiyori, A. et al. Localization of fractalkine and CX3CR1 mRNAs in rat brain: does fractalkine play a role in signaling from neuron to microglia? FEBS Lett. 429, 167–172 (1998).

Meucci, O. et al. Chemokines regulate hippocampal neuronal signaling and gp120 neurotoxicity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 14500–14505 (1998).

Harrison, J. K. et al. Role for neuronally derived fractalkine in mediating interactions between neurons and CX3CR1-expressing microglia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 10896–10901 (1998).

Ragozzino, D. et al. Chemokine fractalkine/CX3CL1 negatively modulates active glutamatergic synapses in rat hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 26, 10488–10498 (2006).

Bertollini, C., Ragozzino, D., Gross, C., Limatola, C. & Eusebi, F. Fractalkine/CX3CL1 depresses central synaptic transmission in mouse hippocampal slices. Neuropharmacology 51, 816–821 (2006).

Lorea-Hernandez, J. J., Morales, T., Rivera-Angulo, A. J., Alcantara-Gonzalez, D. & Pena-Ortega, F. Microglia modulate respiratory rhythm generation and autoresuscitation. Glia 64, 603–619 (2016).

Camacho-Hernandez, N. P., Lorea-Hernandez, J. J. & Pena-Ortega, F. Microglial modulators reduce respiratory rhythm long-term facilitation in vitro. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 265, 9–18 (2019).

Camacho-Hernandez, P., Lorea-Hernandez, J. J., Pinedo-Vargas, L. & Pena-Ortega, F. Perinatal inflammation and gestational intermittent hypoxia disturbs respiratory rhythm generation and long-term facilitation in vitro: Partial protection by acute minocycline. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 297, 103829 (2022).

Corsi, G. et al. Microglia modulate hippocampal synaptic transmission and sleep duration along the light/dark cycle. Glia 70, 89–105 (2022).

Paul, D. & Basavan, D. Implications of fractalkine on glial function, ablation and glial proteins/receptors/markers—understanding its therapeutic usefulness in neurological settings: a narrative review. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 8, 56 (2022).

Mitchell, G. S. & Johnson, S. M. Neuroplasticity in respiratory motor control. J. Appl Physiol. (1985) 94, 358–374 (2003).

Vose, A. K. et al. Therapeutic acute intermittent hypoxia: A translational roadmap for spinal cord injury and neuromuscular disease. Exp. Neurol. 347, 113891 (2022).

Bisgard, G. E. Carotid body mechanisms in acclimatization to hypoxia. Respir. Physiol. 121, 237–246 (2000).

Kumar, P. & Prabhakar, N. R. Peripheral chemoreceptors: function and plasticity of the carotid body. Compr. Physiol. 2, 141–219 (2012).

Kline, D. D. Chronic intermittent hypoxia affects integration of sensory input by neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarii. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 174, 29–36 (2010).

Feldman, J. L., Mitchell, G. S. & Nattie, E. E. Breathing: rhythmicity, plasticity, chemosensitivity. Annu Rev. Neurosci. 26, 239–266 (2003).

Feldman, J. L., Neverova, N. V. & Saywell, S. A. Modulation of hypoglossal motoneuron excitability by intracellular signal transduction cascades. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 147, 131–143 (2005).

Blitz, D. M. & Ramirez, J. M. Long-term modulation of respiratory network activity following anoxia in vitro. J. Neurophysiol. 87, 2964–2971 (2002).

Dale-Nagle, E. A., MacFarlane, H. M. & Mitchell, P. M. GS. Multiple pathways to long-lasting phrenic motor facilitation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 669, 225–230 (2010).

Devinney, M. J., Huxtable, A. G., Nichols, N. L. & Mitchell, G. S. Hypoxia-induced phrenic long-term facilitation: emergent properties. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 1279, 143–153 (2013).

Keswani, N. H. & Hollinshead, W. H. The phrenic nucleus. III. Organization of the phrenic nucleus in the spinal cord of the cat and man. Proc. Staff Meet. Mayo Clin. 30, 566–577 (1955).

Fogarty, M. J., Mantilla, C. B. & Sieck, G. C. Breathing: Motor control of diaphragm muscle. Physiol. (Bethesda) 33, 113–126 (2018).

Fuller, D. D., Rana, S., Smuder, A. J. & Dale, E. A. The phrenic neuromuscular system. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 188, 393–408 (2022).

Nichols, N. L., Dale, E. A. & Mitchell, G. S. Severe acute intermittent hypoxia elicits phrenic long-term facilitation by a novel adenosine-dependent mechanism. J. Appl Physiol. (1985) 112, 1678–1688 (2012).

Hoffman, M. S., Golder, F. J., Mahamed, S. & Mitchell, G. S. Spinal adenosine A2(A) receptor inhibition enhances phrenic long term facilitation following acute intermittent hypoxia. J. Physiol. 588, 255–266 (2010).

Baker-Herman, T. L. & Mitchell, G. S. Phrenic long-term facilitation requires spinal serotonin receptor activation and protein synthesis. J. Neurosci. 22, 6239–6246 (2002).

Perim, R. R., Fields, D. P. & Mitchell, G. S. Cross-talk inhibition between 5-HT2B and 5-HT7 receptors in phrenic motor facilitation via NADPH oxidase and PKA. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 314, R709–R715 (2018).

Perim, R. R. & Mitchell, G. S. Circulatory control of phrenic motor plasticity. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 265, 19–23 (2019).

Mitchell, G. S. & Baker, T. L. Respiratory neuroplasticity: Mechanisms and translational implications of phrenic motor plasticity. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 188, 409–432 (2022).

Perim, R. R., El-Chami, M., Gonzalez-Rothi, E. J. & Mitchell, G. S. Baseline arterial CO2 pressure regulates acute intermittent hypoxia-induced phrenic long-term facilitation in rats. Front Physiol. 12, 573385 (2021).

Tadjalli, A. & Mitchell, G. S. Cervical Spinal 5-HT2A and 5-HT2B receptors are both necessary for moderate acute intermittent hypoxia-induced phrenic long-term facilitation. J Appl. Physiol. (1985), https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.01113.2018 (2019).

Marciante, A. B., Seven, Y. B., Kelly, M. N., Perim, R. R. & Mitchell, G. S. Magnitude and mechanism of phrenic long-term facilitation shift between daily rest vs active phase. Function, https://doi.org/10.1093/function/zqad041 (2023).

Acton, D. & Miles, G. B. Stimulation of Glia reveals modulation of mammalian spinal motor networks by adenosine. PLoS One 10, e0134488 (2015).

Golder, F. J. et al. Spinal adenosine A2a receptor activation elicits long-lasting phrenic motor facilitation. J. Neurosci. 28, 2033–2042 (2008).

Perim, R. R., Kubilis, P. S., Seven, Y. B. & Mitchell, G. S. Hypoxia-induced hypotension elicits adenosine-dependent phrenic long-term facilitation after carotid denervation. Exp. Neurol. 333, 113429 (2020).

Hayashi, F., Coles, S. K., Bach, K. B., Mitchell, G. S. & McCrimmon, D. R. Time-dependent phrenic nerve responses to carotid afferent activation: intact vs. decerebellate rats. Am. J. Physiol. 265, R811–819, (1993).

Mitchell, G. S. et al. Invited review: Intermittent hypoxia and respiratory plasticity. J. Appl Physiol. (1985) 90, 2466–2475 (2001).

Okojie, A. K. et al. Distinguishing the effects of systemic CSF1R inhibition by PLX3397 on microglia and peripheral immune cells. J. Neuroinflammation 20, 242 (2023).

Elmore, M. R. et al. Colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor signaling is necessary for microglia viability, unmasking a microglia progenitor cell in the adult brain. Neuron 82, 380–397 (2014).

Szepesi, Z., Manouchehrian, O., Bachiller, S. & Deierborg, T. Bidirectional microglia-neuron communication in health and disease. Front Cell Neurosci. 12, 323 (2018).

Zhu, W. et al. Elevated expression of fractalkine (CX3CL1) and fractalkine receptor (CX3CR1) in the dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: implications in multiple sclerosis-induced neuropathic pain. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 480702 (2013).

Tadjalli, A., Baker, T., Watters, J. J. & Mitchel, G. S. Fractalkine signaling in the cervical spinal cord orchestrates microglia-neuron interactions regulating intermittent hypoxia-induced phrenic motor plasticity. FASEB J. 35, https://doi.org/10.1096/fasebj.2021.35.S1.02364 (2021).

Seven, Y. B. et al. Phrenic motor neuron adenosine 2A receptors elicit phrenic motor facilitation. J. Physiol. 596, 1501–1512 (2018).

Devinney, M. J. et al. Phrenic long-term facilitation requires PKCtheta activity within phrenic motor neurons. J. Neurosci. 35, 8107–8117 (2015).

Dale, E. A., Fields, D. P., Devinney, M. J. & Mitchell, G. S. Phrenic motor neuron TrkB expression is necessary for acute intermittent hypoxia-induced phrenic long-term facilitation. Exp. Neurol. 287, 130–136 (2017).

Fields, D. P. & Mitchell, G. S. Divergent cAMP signaling differentially regulates serotonin-induced spinal motor plasticity. Neuropharmacology 113, 82–88 (2017).

Hayes, H. B. et al. Daily intermittent hypoxia enhances walking after chronic spinal cord injury: a randomized trial. Neurology 82, 104–113 (2014).

Sandhu, M. S., Perez, M. A., Oudega, M., Mitchell, G. S. & Rymer, W. Z. Efficacy and time course of acute intermittent hypoxia effects in the upper extremities of people with cervical spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 342, 113722 (2021).

Trumbower, R. D., Hayes, H. B., Mitchell, G. S., Wolf, S. L. & Stahl, V. A. Effects of acute intermittent hypoxia on hand use after spinal cord trauma: A preliminary study. Neurology 89, 1904–1907 (2017).

Tremblay, M. E. et al. The role of microglia in the healthy brain. J. Neurosci. 31, 16064–16069 (2011).

Li, Y., Du, X. F., Liu, C. S., Wen, Z. L. & Du, J. L. Reciprocal regulation between resting microglial dynamics and neuronal activity in vivo. Dev. Cell 23, 1189–1202 (2012).

Kettenmann, H., Hanisch, U. K., Noda, M. & Verkhratsky, A. Physiology of microglia. Physiol. Rev. 91, 461–553 (2011).

Morris, R. G. et al. Elements of a neurobiological theory of the hippocampus: the role of activity-dependent synaptic plasticity in memory. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 358, 773–786 (2003).

Sakata, K. et al. Role of activity-dependent BDNF expression in hippocampal-prefrontal cortical regulation of behavioral perseverance. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 15103–15108 (2013).

Citri, A. & Malenka, R. C. Synaptic plasticity: multiple forms, functions, and mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 18–41 (2008).

MacFarlane, P. M., Satriotomo, I., Windelborn, J. A. & Mitchell, G. S. NADPH oxidase activity is necessary for acute intermittent hypoxia-induced phrenic long-term facilitation. J. Physiol. 587, 1931–1942 (2009).

MacFarlane, P. M., Vinit, S. & Mitchell, G. S. Serotonin 2A and 2B receptor-induced phrenic motor facilitation: differential requirement for spinal NADPH oxidase activity. Neuroscience 178, 45–55 (2011).

Kinkead, R., Bach, K. B., Johnson, S. M., Hodgeman, B. A. & Mitchell, G. S. Plasticity in respiratory motor control: intermittent hypoxia and hypercapnia activate opposing serotonergic and noradrenergic modulatory systems. Comp. Biochem Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 130, 207–218 (2001).

Perim, R. R., Gonzalez-Rothi, E. J. & Mitchell, G. S. Cervical spinal injury compromises caudal spinal tissue oxygenation and undermines acute intermittent hypoxia-induced phrenic long-term facilitation. Exp. Neurol. 342, 113726 (2021).

Bach, K. B. & Mitchell, G. S. Hypoxia-induced long-term facilitation of respiratory activity is serotonin dependent. Respir. Physiol. 104, 251–260 (1996).

Devinney, M. J., Nichols, N. L. & Mitchell, G. S. Sustained Hypoxia elicits competing spinal mechanisms of phrenic motor facilitation. J. Neurosci. 36, 7877–7885 (2016).

Navarrete-Opazo, A., Dougherty, B. J. & Mitchell, G. S. Enhanced recovery of breathing capacity from combined adenosine 2A receptor inhibition and daily acute intermittent hypoxia after chronic cervical spinal injury. Exp. Neurol. 287, 93–101 (2017).

Nichols, N. L. & Mitchell, G. S. Mechanisms of severe acute intermittent hypoxia-induced phrenic long-term facilitation. J. Neurophysiol. 125, 1146–1156 (2021).

Stockwell, J., Jakova, E. & Cayabyab, F. S. Adenosine A1 and A2A receptors in the brain: current research and their role in neurodegeneration. Molecules 22, https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22040676 (2017).

McGuire, M., Liu, C., Cao, Y. & Ling, L. Formation and maintenance of ventilatory long-term facilitation require NMDA but not non-NMDA receptors in awake rats. J. Appl Physiol. (1985) 105, 942–950 (2008).

Finneran, D. J. & Nash, K. R. Neuroinflammation and fractalkine signaling in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflammation 16, 30 (2019).

Azizi, G., Khannazer, N. & Mirshafiey, A. The potential role of chemokines in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 29, 415–425 (2014).

Pawelec, P., Ziemka-Nalecz, M., Sypecka, J. & Zalewska, T. The impact of the CX3CL1/CX3CR1 axis in neurological disorders. Cells 9, https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9102277 (2020).

Chapman, G. A. et al. Fractalkine cleavage from neuronal membranes represents an acute event in the inflammatory response to excitotoxic brain damage. J. Neurosci. 20, RC87 (2000).

Baker-Herman, T. L. et al. BDNF is necessary and sufficient for spinal respiratory plasticity following intermittent hypoxia. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 48–55 (2004).

Matyash, M., Zabiegalov, O., Wendt, S., Matyash, V. & Kettenmann, H. The adenosine generating enzymes CD39/CD73 control microglial processes ramification in the mouse brain. PLoS One 12, e0175012 (2017).

Portiansky, E. L., Nishida, F., Barbeito, C. G., Gimeno, E. J. & Goya, R. G. Increased number of neurons in the cervical spinal cord of aged female rats. PLoS One 6, e22537 (2011).

Mantilla, C. B., Zhan, W. Z. & Sieck, G. C. Retrograde labeling of phrenic motoneurons by intrapleural injection. J. Neurosci. Methods 182, 244–249 (2009).

De Felice, E. et al. Microglial diversity along the hippocampal longitudinal axis impacts synaptic plasticity in adult male mice under homeostatic conditions. J. Neuroinflammation 19, 292 (2022).

Scianni, M. et al. Fractalkine (CX3CL1) enhances hippocampal N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) function via D-serine and adenosine receptor type A2 (A2AR) activity. J. Neuroinflammation 10, 108 (2013).

Taves, S., Berta, T., Chen, G. & Ji, R. R. Microglia and spinal cord synaptic plasticity in persistent pain. Neural Plast. 2013, 753656 (2013).

Rogers, J. T. et al. CX3CR1 deficiency leads to impairment of hippocampal cognitive function and synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci. 31, 16241–16250 (2011).

Marciante, A. B. & Mitchell, G. S. Mild inflammation impairs acute intermittent hypoxia-induced phrenic long-term facilitation by a spinal adenosine-dependent mechanism. J. Neurophysiol. 129, 799–806 (2023).

Rodriguez-Gomez, J. A. et al. Microglia: Agents of the CNS pro-inflammatory response. Cells 9, https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9071717 (2020).

Linnerbauer, M., Wheeler, M. A. & Quintana, F. J. Astrocyte crosstalk in CNS inflammation. Neuron 108, 608–622 (2020).

Sochocka, M., Diniz, B. S. & Leszek, J. Inflammatory response in the CNS: Friend or foe? Mol. Neurobiol. 54, 8071–8089 (2017).

Shigetomi, E., Sakai, K. & Koizumi, S. Extracellular ATP/adenosine dynamics in the brain and its role in health and disease. Front Cell Dev. Biol. 11, 1343653 (2023).

Martin, E. D. et al. Adenosine released by astrocytes contributes to hypoxia-induced modulation of synaptic transmission. Glia 55, 36–45 (2007).

Ayers, J. I. et al. Widespread and efficient transduction of spinal cord and brain following neonatal AAV injection and potential disease modifying effect in ALS mice. Mol. Ther. 23, 53–62 (2015).