Abstract

Oceanic gateways play a crucial role in controlling global ocean circulation. However, gateway effects on low-latitude deep-water circulation are poorly understood. The South China Sea, located in the western Pacific, was influenced by changes in the equatorial and low-latitude gateways, which recorded significant oceanographic variations since the Oligocene. Here, we identify contourite features in the deep South China Sea from seismic data and drill cores from Ocean Drilling Program Leg 184 and International Ocean Discovery Program Expeditions 349 and 367/368, as evidence for the influence of Circumpolar Deep Water originating from the eastern Indian Ocean until ca. 10 Ma. Final closure of the deep Indonesian Gateway at ca. 10 Ma caused disruption of the deep-water connection between the Pacific and Indian Oceans and a reorganization of global deep-water circulation. These changes in gateway tectonics may significantly contribute to the Middle to Late Miocene global climate and oceanic conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global thermohaline circulation and climate have been profoundly influenced by oceanic gateway tectonics1,2,3. Three major gateway events, including closing of the Central American Seaway, opening of the Bering Strait, and closing of the Indonesian Gateway, have led to the establishment and stabilization of the present-day Pacific circulation3. Prior to this modern setting, however, the deep Pacific circulation experienced several stages of reorganization4,5. A suggested factor is global climate change, such as the Mi-1 glaciation during the latest Oligocene or the Antarctic ice sheet expansion in the Middle Miocene4,5,6. Nevertheless, the effect of oceanic gateways, especially the Indonesian Gateway, on paleocirculation patterns remain unclear. Previous studies suggested that deep-water connection existed through the Indonesian Gateway during the Early to Middle Miocene7. The deep pathway allowed bottom water to flow from the Indian to the Pacific Oceans, which subsequently influenced the intermediate Miocene Indian Ocean Equatorial Jet (MIOJet) during the Middle Miocene8. Restriction on the surface throughflow occurred between 12 and 3 Ma9, but their precise timing and impact are still a matter of debate7,9.

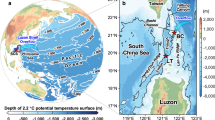

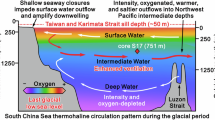

At present, heat and freshwater exchange across the restricted Indonesian Gateway is affected by the South China Sea overturning circulation, which is formed by mixing, downwelling, and upwelling of the Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW) and North Pacific Deep Water (NPDW)10,11 (Fig. 1). Results from Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) Leg 18412,13 confirmed persistent influences of southern component waters in the deep (>2500 m depth) South China Sea since its opening at ca. 32 Ma. Sedimentary depositional systems in the East (since ca. 32 Ma), Northwest (since ca. 32 Ma), and Southwest (since ca. 23 Ma) subbasins14,15,16 of the South China Sea can, thus, document paleoceanographic changes in the western Pacific and record oceanic gateway evolution and its effects since the Oligocene.

a Present-day oceanic circulation in the eastern Indian and western Pacific Oceans11,13,49. b Modern oxygen profile across the South China Sea and the Philippine Sea. The projected IODP drilling sites are shown in the oxygen profile to indicate their respective water masses. Location of transect b is indicated in (a). c Location of the datasets. Seismic data were from China National Offshore Oil Corporation, China Geological Survey, and previous studies16,27,56,63. (ODP Ocean Drilling Program, IODP International Ocean Discovery Program, DSDP Deep Sea Drilling Project).

In this study, we investigated contourite sedimentary features formed by bottom currents on the lower continental slope and abyssal plain (below 2500 m depth) of the South China Sea using drill cores (Fig. 2) from ODP Site 1148 (Leg 184) and International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) Expeditions 349 and 367/368 and seismic data (Fig. 3). Distinct sedimentary changes in the contourite features reveal substantial variations in CDW and NPDW since ca. 32 Ma. These changes are linked to paleoceanographic patterns of the Indian and western Pacific Oceans, which suggest a reorganization of deep-water circulation triggered by oceanic gateway tectonics during the Late Miocene.

a Correlations between downhole measurements for Site U1505 and time-based seismic data56. b Synthetic seismogram. Time to depth conversion is established based on synthetic seismograms and a time-depth relationship model. Plane-wave construction velocity is used in the calculation. c Age-depth model and average sedimentation rate from IODP Sites U1505, U1501, U1504, U1500, U1431, and ODP Site 114813,16,56. d Lithology from IODP Sites U1505C, U1501C, U1504A, U1500A-B, and U1431D-E16,56. Variations in the natural gamma radiation log are correlated with major seismic discontinuities and contourite drift evolution.

a–f Interpretations of seismic units and contourite features in the South China Sea deep basins. g Contourite features of Benham Rise (Philippine Sea)41,42. h Buried contourite features of Bone Gulf (Offshore Sulawesi)63. Seismic discontinuities were correlated to previous chronostratigraphic studies15,27,59,60. Locations of seismic lines are indicated in Fig. 1c.

Results and discussion

Contourite features in the deep South China Sea

Contourite drifts are large sedimentary bodies deposited by bottom currents, where their evolution indicates variations on ocean circulation through geological time2. Contourite drifts of distinct morphologies (i.e. mounded, plastered, and sheeted drifts; Supplementary Fig. 1) are widely identified in the South China Sea (Fig. 3). Seismic interpretation shows that the contourite drifts exhibit large variations within the different South China Sea subbasins (Fig. 3). The drifts are observed in different seismic units, which are divided by major seismic discontinuities T60 (ca. 23 Ma), T51 (ca. 19 Ma), T50 (ca. 15.5 Ma), T40 (ca. 10 Ma), T30 (ca. 5.3 Ma), T20 (ca. 2.6 Ma), and T1 (ca. 0.9 Ma).

A mounded drift with a paleo-moat is identified across seismic units A (ca. 23–19 Ma), B (ca.19–15.5 Ma), and C (ca.15.5–10 Ma) in the southern East Subbasin (Fig. 3f), while several mounded drifts (Fig. 3a–c), paleo-moats, and bottom current-related erosional troughs17 are found in seismic units B (ca. 19–15.5 Ma) and C (ca. 15.5–10 Ma) on the northern part of the subbasin. Mounded geometries are not observed for seismic unit D (ca. 10–5.3 Ma) in most parts of the East Subbasin (Fig. 3), with exceptions along some structural highs in the northeast East Subbasin, where small-scale low-relief mounded drifts (since 7.16 Ma) were discovered18. Moats, along with mounded19, plastered, and sheeted drifts, are widely identified in seismic units E (ca. 5.3–2.6 Ma)18, F (ca. 2.6–0.9 Ma) and G (ca. 0.9 Ma to present) in the East Subbasin (Fig. 3).

In the Northwest Subbasin, mounded drifts are recognized in seismic units B (ca. 19–15.5 Ma) and C (ca. 15.5–10 Ma) (Fig. 3e). Turbidites and basin-floor fan systems20 dominated seismic units D (ca. 10–5.3 Ma) and E (ca. 5.3–2.6 Ma), whereas plastered and mounded drifts can be further observed in seismic units F (ca. 2.6–0.9 Ma) and G (ca. 0.9 Ma to present) (Fig. 3e; Supplementary Fig. 2c). In contrast, no large-scale mounded drifts can be identified from seismic interpretation in the Southwest Subbasin (Supplementary Fig. 2a).

Furthermore, sedimentary features from drill cores show similar changes but at different scales in their sedimentary stacking patterns, when compared to the results of seismic interpretation (Fig. 4). Interbedded contourites (thin-bedded, with bi-gradational or coarsening-upward sequences), hemipelagites, and turbidites (with fining-upward sequences) are observed for both the Early to Middle Miocene (seismic units A-C; ca. 23–10 Ma) and the Pliocene to Pleistocene units (seismic units E-G; ca. 5.3 Ma to present) (Fig. 4). For the Late Miocene unit (seismic unit D; ca. 10–5.3 Ma), overall fining-upward sedimentary sections with turbidite-contourite-turbidite sequences are observed. Bi-gradational contourites with ripples and wavy lamination are generally found at the lower part or base of the sedimentary section (Fig. 4), which can be observed in all drill cores acquired from the South China Sea abyssal plain. These sections are defined as bottom current reworked turbidites and are comparable to examples identified in the Gulf of Cadiz21, Antarctic Peninsula22, and Tanzania23.

Interpretation of sedimentary facies is based on lithology and sedimentary structures from drill cores. Age model is based on biostratigraphic and magnetostratigraphic data16,56 in Fig. 2c. Main seismic units, contourite drift evolution, paleodepth reconstruction13,29, and dominant water masses are indicated in the right column.

IODP Sites U1501C and U1504A were drilled near moats and paleo-moats in the northern East Subbasin (Fig. 3a and c). Several bi-gradational contourite sequences (each 3–51 cm thick) can be found correlated to seismic units A-C (ca. 23–10 Ma) and F-G (ca. 2.6 Ma to present) (Fig. 4). Contourites in these units are characterized by structureless muddy to silty deposits with relatively low to moderate sedimentation rates (6-35 mm/kyr; Fig. 4). These features represent fine-grained abyssal contourites, which are distinct from typical sandy contourite deposits recovered from IODP Expedition 33921,24,25. Natural gamma radiation (NGR) logs, which generally represent variation in sediment grain-size26, exhibit significant changes at ca. 23 Ma, ca. 19 Ma, ca. 15.5-14 Ma, ca. 11–10 Ma, ca. 5 Ma, ca. 2.6 Ma, and ca. 0.9 Ma (Fig. 2d). These timings are coeval with the occurrence of major seismic discontinuities (T60, T51, T50, T40, T30, T20, and T1) in the deep South China Sea (Fig. 2d).

Contourite evolutionary stages since ca. 32 Ma

Uncertainties still remain for the precise age of major seismic discontinuities due to the sampling interval, but approximate geological time for discontinuities T60 (ca. 23 Ma), T51 (ca. 19 Ma), T50 (ca. 15.5 Ma), T40 (ca. 10 Ma), T30 (ca. 5.3 Ma), T20 (ca. 2.6 Ma), and T1 (ca. 0.9 Ma) were determined. Major changes in the internal sedimentary stacking pattern, geometry, sedimentation rate, and scale of the contourite drifts in the deep South China Sea suggest the occurrence of five distinct evolutionary stages since the Oligocene.

Stage I (Oligocene, ca. 32-23 Ma) marks the preliminary period when contourite drifts were absent in the South China Sea deep basin. Sedimentary processes during this stage were dominated by turbidity currents, debris flows, and mass wasting, which were influenced by active seafloor spreading in the South China Sea27,28.

Stage II (Early Miocene, ca. 23-15.5 Ma) marks the onset of contourite drifts formation. Muddy contourite drifts, paleo-moats (Fig. 3), and erosional troughs17 were generated in the South China Sea deep basin, which suggest an initial growth of contourite features.

Stage III (Middle Miocene, ca. 15.5-10 Ma) marks the growth of contourite drifts into larger sizes (Fig. 3e) and development of thicker bi-gradational sequences (Fig. 4), which indicate a more established contourite system in the South China Sea deep basin.

Stage IV (Late Miocene, ca. 10-5.3 Ma) marks a significant change in the sedimentary and oceanographic processes in the deep basin of the South China Sea. Previously constructed mounded drifts abruptly ceased at ca. 10 Ma (Fig. 3), but drift development recurred after 7.16 Ma18. Presence of bottom current reworked turbidites indicates strong interactions between downslope and alongslope sedimentary processes between ca. 10-5.3 Ma.

Stage V (ca. 5.3 Ma - present) reflects the generation of modern deep-water contourite depositional system of the South China Sea. Related contourite features were deposited with increasing sedimentation rates (Fig. 4), becoming significant morphological units in the South China Sea (Fig. 3).

All of the identified contourite features were formed at a depth of >2500 m, according to paleodepth reconstructions from ODP Site 114813 (Fig. 4) and IODP Site U150229. These evolutionary stages suggest that the South China Sea deep-water circulation experienced significant changes at ca. 23, 15.5, 10, and 5.3 Ma.

Circumpolar Deep Water variations

The Early to Middle Miocene deep Pacific Ocean was dominated by the CDW sourced from the Southern Ocean30,31,32. Two types of CDW existed in the NW Pacific: (1) CDW from the southern Pacific32 and (2) CDW from the eastern Indian Ocean through the Indonesian Gateway8. Benthic δ13C proxies from the South China Sea (ODP Site 1148)13 and the Ontong Java Plateau (ODP Sites 28930,33 and 80734) are comparable after 8-10 Ma (Fig. 5b). Conversely, benthic δ13C proxies of the South China Sea13 and the NE Indian Ocean (IODP Site 1443, the Bay of Bengal)35 show similarities in their trend before 10 Ma (Fig. 5c). Studies from IODP Site U14385 indicate that CDW from the SW Pacific only reached the NW Pacific (20-30°N) after the Middle Miocene Climate Transition (MMCT; ca. 14 Ma). This Pacific-influenced CDW could hardly explain the onset of contourite drifts at ca. 23 Ma in the deep South China Sea (10-22°N). The evidence supports the hypothesis that the CDW in the South China Sea shared an Indian Ocean influence during the Early Miocene.

a εNd (t) values derived from fish tooth and ferromanganese nodules of ODP Site 80732, IODP Site U14385, core D137-144, IODP Site 149938, core 05E10764, core DODO 232D39, and ODP Site 7588. Modern εNd (t) values in deep (>2000 m depth) North and South Pacific65 and NE Indian Ocean8,66 are shown. b, c Benthic δ13C proxies from IODP Site 144335, ODP Site 80734, ODP Site 28930,33, ODP Site 114813, ODP Sites 757 and 75853, and global ocean composite record1. d Major gateway tectonics and climate events since earliest Miocene1,3. Location of drilling sites are shown in Fig. 1 (NH - Northern Hemisphere; N-pac - North Pacific; S-pac - South Pacific; Pleist. - Pleistocene; Plio. - Pliocene).

Previous studies suggested a continuous influence of deep-water circulation in the South China Sea since the Late Oligocene (ca. 26 Ma), based on benthic foraminifera assemblages and isotope proxies13. However, contourite drifts were not immediately seen at ca. 26 Ma in the deep South China Sea, but appeared only since the earliest Early Miocene (ca. 23 Ma) (Figs. 3, 4). This timing is coeval with CDW enhancement due to the major expansion of marine ice sheets in the Southern Ocean at 22-23 Ma6,36 and an Early Miocene restriction of the Drake Passage at 22 Ma37. Construction of contourite drifts in the South China Sea were, therefore, closely linked to CDW paleoceanography. The CDW possibly flowed into the South China Sea in an anticyclonic pattern during the Early Miocene (Fig. 6a), where this flow pathway could explain the eastward bottom currents along the lower continental slope in the northern South China Sea at that time17.

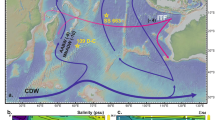

a-c Variation of Circumpolar Deep Water, development of contourite drifts, and final closure of the Indonesian Gateway. d Modern geography of the Sulawesi and Miocene deep-water sedimentary features47. e Shoaling and restriction of the Sulawesi pathway through geological timescale. Regional paleobathymetry maps48 (Mollweide projection) and bathymetric profiles3,48 are derived from previous models (Supplementary Fig. 4).

After ca. 15-14 Ma, an enhanced CDW reached the northern Pacific from the SW Pacific5. However, Nd isotope compositions from the South China Sea (IODP Site U1499; εNd = −6.1 to −8.9)38 showed an increasing influence from the eastern Indian Ocean-sourced CDW (εNd = −6.7 to −10)8,39, rather than from the SW Pacific (ODP Site 807 from the Ontong Java Plateau; εNd = −3 to −5)32 and (Fig. 5a). In addition, benthic δ13C proxies of the South China Sea and the Bay of Bengal are more comparable between 10 and 15 Ma (Fig. 5b, c), which indicate the domination of CDW from the eastern Indian Ocean in the deep South China Sea. This variation in CDW significantly influenced the construction of contourite drifts in the South China Sea, where some contourite features developed more pronounced mounded geometries and U-shaped moats (in seismic unit C; Fig. 3b, e). NGR logs (from IODP Sites U1501C, U1504A, and U1505C) gradually decreased between ca. 15.5 and 10 Ma (Fig. 2d), suggesting the transportation of coarser sediments by enhanced bottom currents along the lower continental slope of the South China Sea. Such changes in the bottom current behaviour were consistent with major short-term variations in global climates40. The East Antarctic Ice Sheet expansion, global sea-level fall, partial atmospheric CO2 drawdown, and increased aridity in the mid-latitudes occurred during this interval5,40, which may also affect bottom current intensity in the deep South China Sea.

At ca. 10 Ma, the development of previously constructed large-scale contourite drifts abruptly ceased in the deep South China Sea basin and the Bone Gulf (Fig. 3). Conversely, contourite drifts were constructed on the Benham Rise (the Philippine Sea) after 10.5 Ma (Figs. 1c, 3g)41,42, reflecting a major change in paleocirculation patterns. Coevally, benthic foraminifera species C. wuellerstorfi and high-oxygen benthic faunal groups suddenly declined in the South China Sea (ODP Site 114812,13), contrary to those in the eastern Indian Ocean (ODP Site 1443)35. Benthic δ13C proxies from ODP Site 114812,13 in the South China Sea were also not consistent with those acquired in the Indian Ocean35 after ca. 10 Ma (Fig. 5b). These changes probably indicate a disconnection of deep-water masses between the eastern Indian and western Pacific Oceans (Fig. 6b).

During the Late Miocene (ca. 10–5.3 Ma), the southern Pacific-influenced CDW passed the Benham Rise in the Philippine Sea before entering the deep South China Sea. Benthic δ13C proxies from ODP Site 114812,13 were lower than those reported in the global record1 during this time interval (Fig. 5c). This variation was related to the formation of regional deep or bottom water circulation, suggesting reduced influences of CDW and PDW in the South China Sea12,13. From the latest Miocene (ca. 5.3 Ma) onwards, increasing number of contourite drifts with larger dimensions are continuously generated in the deep South China Sea (Figs. 3, 6c). Previous studies confirmed the vital role of the Luzon Strait tectonics in the deep South China Sea circulation since 5.3 Ma43, where both paleoceanography12 and sedimentary records19 suggest the establishment of a modern-like South China Sea overturning circulation. Initiation of the deep South China Sea circulation at ca. 5.3 Ma coincided with several major paleoceanographic and climatic events1,2, leading to the present ocean circulation system.

Regional and global implications

The variations in CDW circulation indicate final closure of the deep Indonesian Gateway at ca. 10 Ma. Previous studies suggest a reduced deep-water exchange through the Indonesian Gateway between 14 and 9 Ma8, followed by a more dominant equatorial Pacific deep water after 10 Ma44. These paleoceanographic changes, along with contourite evolution in the South China Sea, may indicate an initial shoaling (at ca. 14-15 Ma) and the final closure (at ca. 10 Ma) of the deep Indonesian Gateway. This deep pathway was most likely present in the Central Sulawesi during the Early to Middle Miocene (Fig. 6a and d). Evidences include collision of the Sula Spur and West Sulawesi (15–10 Ma)7,45,46, Miocene paleobathymetric reconstruction3 (Fig. 6e; Supplementary Fig. 4), Miocene deep-marine sedimentary outcrop near Tambarana Village (Central Sulawesi)47, and seismic interpretation of contourite drifts (before ca. 10 Ma) in the Bone Gulf, offshore Sulawesi (Fig. 3h). Hence, the Central Sulawesi is key for the discovery of bottom current related sedimentary outcrops, which can provide higher resolution CDW paleoceanographic information. Reconstructed paleobathymetry3,48 of the deep Sulawesi pathway is, thus, suggested to be considered for Miocene climate and ocean simulation models.

Closure of the Sulawesi pathway may have taken two steps: (1) initial shoaling and restriction of the pathway and (2) final disruption of deep-water connections between the Indian and Pacific Oceans. The first step includes the partial disconnection of the deep Pacific and Indian Oceans, where paleobathymetric reconstruction3,48 showed that the Sulawesi pathway was shallower than 3000 m after 15 Ma (Fig. 6e), due to the Miocene tectonic settings of East Java and West Sulawesi7,45,46. The CDW (2000–4000 m)49 in the eastern Indian Ocean could not fully pass through the Sulawesi pathway. However, there were occurrences of strong upwelling in the Indian Ocean after 13–13.8 Ma due to intensification of the South Asian monsoon35,50. Restriction and shallowing of the Sulawesi pathway may not immediately influence CDW flow pattern due to significant upwelling, but water mass transports (Sv) may theoretically change. This change can cause heat and carbon transport between the Indian and Pacific Oceans, similar to the impacts presented by models and simulations of the Indonesian gateway51. Seawater εNd values dropped to –8.938 in the South China Sea (IODP Site U1499) after ca. 15 Ma (Fig. 5a), which may indicate profound contribution of the eastern Indian Ocean-sourced CDW to the South China Sea. Bottom currents associated with CDW probably were more intense after exiting the Sulawesi pathway. Also, these events were coeval with major climate and paleoceanographic changes1, including Middle Miocene climatic optimum (MMCO)1, onset of MMCT40, and the Late Miocene CO2 reduction and global cooling52. The gateway tectonic may contribute to global climate change of the Middle Miocene.

The second step involves the full disconnection of the deep Pacific and Indian Oceans. As the Sulawesi pathway became shallower than ca. 1250 m3,48 at 10 Ma (Fig. 6d, e), the CDW was no longer able to penetrate through the gateway. This gateway tectonics may explain a significant increasing in seawater εNd values from IODP Site U1499 in the South China Sea at ca. 10–11 Ma (Fig. 5a). The Indonesian Gateway would then only allow the throughflow of shallow water masses from the Pacific to the Indian Oceans as it does today9. The termination of CDW through the Sulawesi pathway and its subsequent influences on the upper-layer ocean circulation (i.e. MIOJet)8 likely played a significant role in the Late Miocene climatic conditions and the equatorial carbonate crash during 12.6–8.6 Ma35.

The final closure of the deep Indonesian Gateway caused reorganization of the deep-water circulation at ca. 10 Ma, which had widespread impact on the Miocene ocean. The deep-water circulation of the eastern Indian Ocean shifted from a Pacific-dominated setting to the modern oceanographic scenario after 9 Ma49. CDW from the SW Pacific dominated the equatorial deep Pacific Ocean after 10 Ma44. Reorganization of deep-sea faunas occurred in both the western Pacific (10.5–10 Ma)31 and eastern Indian (10–8 Ma)53,54 Oceans. Closure of the deep-pathway also may have strongly impacted the meridional overturning circulation in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans, similar to the effect caused by the shallowing of the Central American Seaway at ca. 11 Ma3.

In addition, the onset of deep-water contourite features in the South China Sea was much earlier than previously documented18,19, which indicates a significant influence of CDW as early as ca. 23 Ma in the low-latitudes of the North Pacific. This deep-water circulation pattern may be linked to the carbonate dissolution event at 21 Ma13, enhanced paleoproductivity13, increased sediment budgets27, and the occurrence of rhythmic brown-green claystone55 after 23 Ma in the South China Sea. Anticyclonic deep-water circulation existed in the deep South China Sea until the formation of modern cyclonic deep and bottom water masses at ca. 10 Ma (Fig. 6). Changes in bottom current pathway and direction should be re-evaluated through studies on the sedimentary depositional systems (i.e. canyon migration, contourite drifts, and moats). There may be contourite features yet to be discovered in the Celebes and Banda Seas (Fig. 1c), given that the CDW flowed across these regions during the Early Miocene (Fig. 6a). These examples, along with contourite drifts in the South China Sea, may improve our understanding of the Oligocene-Miocene deep-water circulation in the South East Asian marginal seas.

Methods

Datasets

The dataset used for this study contains multichannel seismic reflection profiles and drill cores from ODP and IODP Expeditions. The multichannel seismic reflection data are provided by China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), China Geological Survey, and IODP Site Survey Data Bank16,56 (Fig. 1c). High-resolution core images and shipboard datasets of IODP Expeditions 349 and 367/368 were obtained from IODP LIMS Online Report Portal (https://web.iodp.tamu.edu/OVERVIEW/). Paleobathymetry maps are based on previous models3,48, while paleobathymetric profiles3 of the deep Sulawesi pathway (Fig. 6e) were made using Global Mapper Software. Modern oxygen profile across the South China Sea (Fig. 1b) were maded using the Ocean Data View software based on the World Ocean Database (WOD) 2013 (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/world-ocean-database).

Biostratigraphy

Correlation between biostratigraphic and seismic data was based on sampling and logging results from IODP Expeditions 349 and 367/368, especially Site U1505 Hole U1505C, as it contains a continuous sedimentary succession from the earliest Oligocene onwards56 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Hole U1505C, located at 18°55.0570′N, 115°51.5370′E with a water depth of 2917.4 m, was drilled to 480.2 mbsf (meters below seafloor) and achieved a remarkable core recovery of 480.15 m. Calcareous nannofossils, which are generally common to abundant in most sections of Hole U1505C were analysed. Planktonic foraminifera were also examined56 (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

Seismic interpretation

Seismic reflection profiles are interpreted using IHS Kingdom™ Suite and Petrel software, with vertical scale expressed in two-way travel time (TWT). The seismic stratigraphic division for major depositional units is based on the identification of regional discontinuities and vertical variations in acoustic facies57. Interpretation of contourite drifts is based on the varying degrees of mounded geometries, continuous wavy or divergent to subparallel reflections, and onlap reflection terminations, whereas moats are identified as V- to U-shaped erosional features parallel and adjacent to the contourite drifts58.

Seismic units A to G recorded major changes in seismic facies, depositional style, and deformation (Fig. 3). They are divided by major seismic discontinuities (T60, T51, T50, T40, T30, T20, and T1) marked by high-amplitude reflections. The Oligocene unit below discontinuity T60 displays low to moderate amplitude chaotic to transparent seismic reflections and is interpreted as tectonic-related turbidites and debrites based on the deposits recovered from drill cores28.

Correlation to seismic data

Time-to-depth conversion was performed for the ages of major seismic discontinuities. Ages are based on biostratigraphic and magnetostratigraphic dating from IODP Expeditions 349 and 367/36816,56 (Fig. 2c). Correlations between downhole measurements and time-domain seismic data were established based on synthetic seismograms and a time-depth relationship (TDR) model using Matlab scripts and Petrel software56 (Fig. 2a, b). Biostratigraphic information from IODP Site 1505 was tied to identified seismic stratigraphic framework (Fig. 2; Supplementary Fig. 3). The seismic discontinuities were also correlated to previous chronostratigraphic studies15,27,59,60 and drill cores from industry wells (performed by China National Offshore Oil Corporation).

Sedimentary facies and contourite evolutionary stages

The sedimentary facies are interpreted based on previous descriptions of bi-gradational contourite, Bouma, and BCRS (bottom current reworked sands) sequences61,62. Hemipelagites are characterized as clay and bioturbated facies, while muddy contourites are comprised of bi-gradational facies that coarsened upwards from clay to silt and sandy silt before fining upwards to clay once again (Fig. 4). Turbidites, which vary from sand and silty sand at the bottom towards clay at the top, display distinct erosional surfaces and fining-upward facies with planar parallel lamination and cross-bedding. Bottom current reworked turbidites are characterized by fining-upward sequences with bi-gradational beds and ripples within the lower part, and are further characterized by planar parallel lamination in the upper part (Fig. 4).

Contourite evolutionary stages in the deep South China Sea were based on variations in the sedimentary stacking pattern identified in this study and in previous works17,18,19. The flow pathway of CDW in Fig. 6 was determined as the location of Early Miocene to present-day contourite features in the East Asian marginal seas (Fig. 3).

Paleobathymetry maps

Paleobathymetry maps were based on two models3,48. The global paleogeography and tectonics in Fig. 6 were established from recent plate-tectonic models48. Time slices of this model have mainly 10 myr time steps. These maps showed the positions of North, West, and East Sulawesi since 20 Ma (Fig. 6a–c). Another global paleobathymetry model was used to construct the paleobathymetric profiles of deep Sulawesi pathway3 (Supplementary Fig. 4). Time slices of this model have mainly 1 myr time steps, showing detailed evolution of deep Sulawesi pathway since 20 Ma (Fig. 6e).

Data availability

Most of the datasets used in this study are publicly available. Bathymetric data were obtained from Global Multi-Resolution Topography (GMRT) (https://www.gmrt.org). Seismic data were partially downloaded from IODP Expeditions 349 and 367/368 (http://publications.iodp.org/proceedings/367_368/367368title.html). Rest of the seismic data were acquired from China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) and China Geological Survey. But these datasets are protected and not available due to commercial restriction and data privacy laws. High-resolution core images and downhole logging from IODP Expeditions 349 and 367/368 were downloaded from LIMS Online Report Portal (https://web.iodp.tamu.edu/OVERVIEW/). Paleobathymetry data (maps) were obtained from Deep Time MapsTM (https://deeptimemaps.com). Modern oceanographic datasets were downloaded from World Ocean Database (2013) (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/products/world-ocean-database).

References

Zachos, J., Pagani, M., Sloan, L., Thomas, E. & Billups, K. Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma to present. Science 292, 686 (2001).

Hernández-Molina, F. J. et al. Onset of Mediterranean outflow into the North Atlantic. Science 344, 1244–1250 (2014).

Straume, E. O., Gaina, C., Medvedev, S. & Nisancioglu, K. H. Global Cenozoic paleobathymetry with a focus on the northern hemisphere oceanic gateways. Gondwana Res. 86, 126–143 (2020).

McKinley, C. C., Thomas, D. J., LeVay, L. J. & Rolewicz, Z. Nd isotopic structure of the Pacific Ocean 40–10 Ma, and evidence for the reorganization of deep North Pacific Ocean circulation between 36 and 25. Ma. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 521, 139–149 (2019).

Kender, S., Bogus, K. A., Cobb, T. D. & Thomas, D. J. Neodymium evidence for increased circumpolar deep water flow to the North Pacific during the middle Miocene climate transition. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 33, 672–682 (2018).

Evangelinos, D. et al. Absence of a strong, deep-reaching Antarctic Circumpolar Current zonal flow across the Tasmanian gateway during the Oligocene to early Miocene. Glob. Planet. Change 208, 103718 (2022).

Gaina, C. & Müller, D. Cenozoic tectonic and depth/age evolution of the Indonesian gateway and associated back-arc basins. Earth-Sci. Rev. 83, 177–203 (2007).

Gourlan, A. T., Meynadier, L. & Allègre, C. J. Tectonically driven changes in the Indian Ocean circulation over the last 25 Ma: neodymium isotope evidence. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 267, 353–364 (2008).

Kuhnt, W., Holbourn, A., Hall, R., Zuvela, M. & Kase, R. Neogene History of the Indonesian throughflow. in Continent-Ocean Interactions Winthin East Asian Marginal Seas (eds. Peter Clift, Wolfgang Kuhnt, Pinxian Wang & D.E. Hayes.) 299-320 (American Geophysical Union, 2004).

Qu, T., Song, Y. T. & Yamagata, T. An introduction to the South China Sea throughflow: Its dynamics, variability, and application for climate. Dyn. Atmos. Oceans 47, 3–14 (2009).

Fuhr, M., Laukert, G., Yu, Y., Nürnberg, D. & Frank, M. Tracing water mass mixing from the equatorial to the North Pacific ocean with dissolved neodymium isotopes and concentrations. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 603761 (2021).

Li, Q. et al. A 33 Ma lithostratigraphic record of tectonic and paleoceanographic evolution of the South China Sea. Mar. Geol. 230, 217–235 (2006).

Zhao, Q., Li, Q. & Jian, Z. Deep waters and oceanic connection. In The South China Sea: Paleoceanography and Sedimentology (eds. P. Wang & Q. Li) 395–437 (Springer Netherlands, 2009).

Sibuet, J.-C., Yeh, Y.-C. & Lee, C.-S. Geodynamics of the South China Sea. Tectonophysics 692, 98–119 (2016).

Xie, X., Zhao, S., Ren, J., Yang, Y. & Yao, Y. Marginal sea closure process and genetic mechanism of South China Sea during post-spreading period. Earth Sci. 47, 3524–33542 (2022).

Li, C.-F., Lin, J., Kulhanek, D.K. & the Expedition 349 Scientists. Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 349: South China Sea Tectonics: College Station, TX. https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.349.2015 (International Ocean Discovery Program, 2015)

Sun, Q. et al. Submarine erosional troughs in the northern South China Sea: evidence for Early Miocene deepwater circulation and paleoceanographic change. Mar. Pet. Geol. 77, 75–91 (2016).

Liang, C. et al. Depositional evolution of sediment drifts inside intra-slope basins on the lower southeastern slope of the Dongsha Islands (South China Sea) and their paleoceanographic implications. Geo-Mar. Lett. 39, 101–116 (2019).

Yin, S. et al. Plate convergence controls long-term full-depth circulation of the South China Sea. Mar. Geol. 459, 107050 (2023).

Chen, H. et al. Depositional architecture and evolution of basin-floor fan systems since the Late Miocene in the Northwest Sub-Basin, South China Sea. Mar. Pet. Geol. 126, 104803 (2021).

de Castro, S. et al. Contourites and bottom current reworked sands: Bed facies model and implications. Mar. Geol. 428, 106267 (2020).

Rodrigues, S. et al. Sedimentary model for mixed depositional systems along the Pacific margin of the Antarctic Peninsula: decoding the interplay of deep-water processes. Mar. Geol. 445, 106754 (2022).

Fuhrmann, A. et al. Hybrid turbidite-drift channel complexes: an integrated multiscale model. Geology 48, 562–568 (2020).

Hernández-Molina, F. J. et al. Evolution of the Gulf of Cadiz margin and southwest Portugal contourite depositional system: tectonic, sedimentary and paleoceanographic implications from IODP expedition 339. Mar. Geol. 377, 7–39 (2016).

Stow, D. et al. Anatomy of the bi-gradational contourite sequence: case study from the Gulf of Cadiz. Mar. Geol. 458, 107026 (2023).

Lofi, J. et al. Quaternary chronostratigraphic framework and sedimentary processes for the Gulf of Cadiz and Portuguese Contourite Depositional Systems derived from Natural Gamma Ray records. Mar. Geol. 377, 40–57 (2016).

Wang, F. & Ding, W. How did sediments disperse and accumulate in the oceanic basin, South China Sea. Mar. Pet. Geol. 147, 105979 (2023).

Ma, P. et al. Oligocene evolution of the outermost continental margin in response to breakup and early spreading of the South China Sea. Mar. Geol. 427, 106241 (2020).

Jian, Z. et al. Discovery of the marine Eocene in the northern South China Sea. Natl. Sci. Rev. 6, 881–885 (2019).

Savin, S. M. et al. Miocene benthic foraminiferal isotope records: a synthesis. Mar. Micropaleontol. 6, 423–450 (1981).

Woodruff, F. & Savin, S. M. Miocene deepwater oceanography. Paleoceanography 4, 87–140 (1989).

Le Houedec, S., Meynadier, L. & Allègre, C. J. Seawater Nd isotope variation in the Western Pacific Ocean since 80Ma (ODP 807, Ontong Java Plateau). Mar. Geol. 380, 138–147 (2016).

Hodell, D. A. & Vayavananda, A. Middle Miocene paleoceanography of the western equatorial Pacific (DSDP site 289) and the evolution ofGloborotalia (Fohsella). Mar. Micropaleontol. 22, 279–310 (1993).

Feng, H., Tian, J., Lyle, M., Westerhold, T. & Wilkens, R. High resolution benthic foraminiferal δ18O and δ13C records at ODP site 807 over the past 5 Ma, Ontong Java Plateau: evolution of North Pacific ventilation, Pliocene to Holocene. Glob. Planet. Change 217, 103945 (2022).

Kochhann, K. G. D. et al. Impacts of the Middle Miocene Climatic Transition on deep-water carbonate preservation and oxygenation in the equatorial Indian Ocean. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 576, 110511 (2021).

Lyle, M., Gibbs, S., Moore, T. C. & Rea, D. K. Late Oligocene initiation of the Antarctic circumpolar current: evidence from the South Pacific. Geology 35, 691–694 (2007).

Lagabrielle, Y., Goddéris, Y., Donnadieu, Y., Malavieille, J. & Suarez, M. The tectonic history of Drake Passage and its possible impacts on global climate. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 279, 197–211 (2009).

Shu, W., Colin, C., Liu, Z. & Dapoigny, A. Late Oligocene–Miocene evolution of deep-water circulation in the abyssal South China Sea: insights from Nd isotopes of fossil fish teeth. Geology 52, 620–624 (2024).

Frank, M., Whiteley, N., van de Flierdt, T., Reynolds, B. C. & O’Nions, K. Nd and Pb isotope evolution of deep water masses in the eastern Indian Ocean during the past 33 Myr. Chem. Geol. 226, 264–279 (2006).

Flower, B. P. & Kennett, J. P. The middle Miocene climatic transition: East Antarctic ice sheet development, deep ocean circulation and global carbon cycling. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 108, 537–555 (1994).

Ingle, J. et al. Site 292. Initial Reports of the Deep-Sea Drilling Projects 31, 67–130 (1975).

Barretto, J., Wood, R. & Milsom, J. Benham Rise unveiled: Morphology and structure of an Eocene large igneous province in the West Philippine Basin. Mar. Geol. 419, 106052 (2020).

Chen, W.-H. et al. Depleted deep South China Sea δ13C paleoceanographic events in response to tectonic evolution in Taiwan–Luzon Strait since Middle Miocene. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 122, 195–225 (2015).

van de Flierdt, T. et al. Deep and bottom water export from the Southern Ocean to the Pacific over the past 38 million years. Paleoceanography 19, PA1020 (2004).

Hall, R. Late Jurassic–Cenozoic reconstructions of the Indonesian region and the Indian Ocean. Tectonophysics 570-571, 1–41 (2012).

Hall, R., Cottam, M. A. & Wilson, M. E. J. The SE Asian gateway: history and tectonics of the Australia–Asia collision. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 355, 1–6 (2011).

Nugraha, A. M. S., Hall, R. & BouDagher-Fadel, M. The Celebes Molasse: a revised Neogene stratigraphy for Sulawesi, Indonesia. J. Asian Earth Sci. 228, 105140 (2022).

Blakey, R.C. Global Paleogeography and Tectonics in Deep Time, Deep Time Maps™dataset. https://deeptimemaps.com (2016).

Prabhat, P. et al. Modern-like deep water circulation in the Indian Ocean caused by Central American Seaway closure. Nat. Commun. 13, 7561 (2022).

Sarr, A.-C. et al. Neogene South Asian monsoon rainfall and wind histories diverged due to topographic effects. Nat. Geosci. 15, 314–319 (2022).

Brierley, C. M. & Fedorov, A. V. Comparing the impacts of Miocene–Pliocene changes in inter-ocean gateways on climate: Central American Seaway, Bering Strait, and Indonesia. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 444, 116–130 (2016).

Burls, N. J. et al. Simulating Miocene warmth: insights From an Opportunistic Multi-Model Ensemble (MioMIP1). Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 36, e2020PA004054 (2021).

Gupta, A. K., Singh, R. K., Joseph, S. & Thomas, E. Indian Ocean high-productivity event (10–8 Ma): linked to global cooling or to the initiation of the Indian monsoons? Geology 32, 753–756 (2004).

Smart, C. W., Thomas, E. & Ramsay, A. T. S. Middle–late Miocene benthic foraminifera in a western equatorial Indian Ocean depth transect: Paleoceanographic implications. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 247, 402–420 (2007).

Zhang, Z. & Sun, Z. The early-mid Miocene abyssal brown/green claystone from IODP Site U1503A in the northern South China Sea: Implications for paleoclimate and paleoceanography. Gondwana Res. 120, 286–303 (2023).

Sun, Z. et al. South China sea rifted margin. Proceedings of the International Ocean Discovery Program, 367/368: College Station, TX (International Ocean Discovery Program). https://doi.org/10.14379/iodp.proc.367368.2018 (2018).

Catuneanu, O. et al. Towards the standardization of sequence stratigraphy. Earth-Sci. Rev. 92, 1–33 (2009).

Rebesco, M., Hernández-Molina, F. J., Van Rooij, D. & Wåhlin, A. Contourites and associated sediments controlled by deep-water circulation processes: State-of-the-art and future considerations. Mar. Geol. 352, 111–154 (2014).

Franke, D. et al. The continent-ocean transition at the southeastern margin of the South China Sea. Mar. Pet. Geol. 28, 1187–1204 (2011).

Yin, S. et al. Migration of the lower North Palawan submarine canyon: characteristics and controls. Int. Geol. Rev. 62, 988–1005 (2020).

de Castro, S. et al. Contourite characterization and its discrimination from other deep-water deposits in the Gulf of Cadiz contourite depositional system. Sedimentology 68, 987–1027 (2021).

Stow, D. & Smillie, Z. Distinguishing between deep-water sediment facies: turbidites, contourites and hemipelagites. Geosciences 10, 68 (2020).

Camplin, D. J. & Hall, R. Neogene history of Bone Gulf, Sulawesi, Indonesia. Mar. Pet. Geol. 57, 88–108 (2014).

Zhong, Y. et al. Tectonic and paleoceanographic conditions during the formation of ferromanganese nodules from the northern South China Sea based on the high-resolution geochemistry, mineralogy and isotopes. Mar. Geol. 410, 146–163 (2019).

Hu, R. & Piotrowski, A. M. Neodymium isotope evidence for glacial-interglacial variability of deepwater transit time in the Pacific Ocean. Nat. Commun. 9, 4709 (2018).

Bang, S. et al. Deep-water circulation over the last two glacial cycles reconstructed from authigenic neodymium isotopes in the equatorial Indian Ocean (Core HI1808-GPC04). Ocean Sci. J. 57, 324–333 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 42206044 and 42130408) and Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai) (No. SML2021SP307). The authors thank Global Multi-Resolution Topography Synthesis (GMRT), World Ocean Database (WOD), Ocean Drilling Program (ODP), and International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) for providing the data. We also thank Marine Geoscience Data System (MGDS) for providing free public access to the geophysical datasets.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. designed the project, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript; H.C., M.S. contributed to seismic interpretation; K.L. J.W., Y.G., Z.M. contributed to core lithology, benthic foraminifera, and stable isotope analyses; S.R., D.D., Z.L.N. contributed to the discussion of gateway tectonics; Z.S., H.Z., X.X. contributed to data acquisition and collection.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Stephen Jones, Xin Shan, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S., Chen, H., Su, M. et al. South China Sea records Late Miocene reorganization of western Pacific deep circulation. Nat Commun 15, 10228 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54739-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54739-4

This article is cited by

-

Sea-level variations influence weak layer formation and submarine landslides on a low-latitude continental margin

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)