Abstract

Physical unclonable function labels have emerged as a promising candidate for achieving unbreakable anticounterfeiting. Despite their significant progress, two challenges for developing practical physical unclonable function systems remain, namely 1) fairly few high-dimensional encoded labels with excellent material properties, and 2) existing authentication methods with poor noise tolerance or inapplicability to unseen labels. Herein, we employ the linear polarization modulation of randomly distributed fluorescent nanodiamonds to demonstrate, for the first time, three-dimensional encoding for diamond-based labels. Briefly, our three-dimensional encoding scheme provides digitized images with an encoding capacity of 109771 and high distinguishability under a short readout time of 7.5 s. The high photostability and inertness of fluorescent nanodiamonds endow our labels with high reproducibility and long-term stability. To address the second challenge, we employ a deep metric learning algorithm to develop an authentication methodology that computes the similarity of deep features of digitized images, exhibiting a better noise tolerance than the classical point-by-point comparison method. Meanwhile, it overcomes the key limitation of existing artificial intelligence-driven classification-based methods, i.e., inapplicability to unseen labels. Considering the high performance of both fluorescent nanodiamonds labels and deep metric learning authentication, our work provides the basis for developing practical physical unclonable function anticounterfeiting systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Counterfeiting is a significant problem worldwide and is responsible for serious economic losses in a wide range of everyday transactions1,2. It can even be life-threatening when counterfeited goods such as fake medicines are passed off as genuine3,4. To tackle this critical issue, techniques such as watermarks or fluorescence labels have been developed, and such techniques are used on banknotes all over the world. However, these conventional approaches are now at risk of a resurgence of counterfeiting, due to the deterministic fabrication process which is prone to forgery5. To this end, the emerging physical unclonable function (PUF) systems, based on non-predictable responses of integrated circuits6 or random patterns of micro/nanostructures5, serve as an effective solution for unforgeable anticounterfeiting. Thanks to recent advancements in nanotechnology and optical cryptography techniques7, PUF labels have been successfully developed based on a large number of optical nanomaterials, including plasmonic nanoparticles8,9,10, surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy nanoparticles11, quantum dots12, Mie-resonant silicon nanoparticles13, upconverting nanoparticles14, and metasurfaces15. In general, these nanomaterials provide a variety of optical signals like photoluminescence, scattering and Raman signals, which can be tailored to carry authentic information for encryption/decryption.

To achieve unbreakable encryption for PUF labels, it is crucial to have a large enough encoding capacity which represents the theoretical maximum number of unique tags5. There are mainly two ways of enhancing encoding capacity5: (1) improving the pixel number of the encoded image, and/or (2) high-dimensional encoding. Compared with the former one, high-dimensional encoding requires a relatively short readout time and is thereby regarded as a promising solution. However, to date, there have been only a few attempts to create high-dimensional (≥3D) encoded PUF labels9,11,16,17. Particularly, the light has been intensively investigated to provide multi-dimensional encrypted information, owing to its abundant degrees of freedom such as polarization, phase, wavelength, and frequency18. Among them, polarization has been explored extensively in various applications such as three-dimensional display technology19, optical communication20, optical storage21, optical encryption22, super-resolution imaging23,24, and orientation measurements23,24. Among the different optical polarization-sensitive emitters (e.g., fluorescent molecules25, plasmonic nanorods26, upconverting nanorods27, carbon nanotubes28, defects in 2D materials29), nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers, a kind of photoluminescent defects hosted in diamond crystals, have been hailed as among the most promising candidates for anticounterfeiting labels due to their high contrast value in polarization modulation (~89% for single NV center30), unlimited photostability31,32, and cost-effective mass production33, not to mention the properties of diamond materials themselves34,35.

In a practical PUF anticounterfeiting system, the desired authentication method should have a low false-positive rate, low time consumption, and noise tolerance. However, prevailing techniques fall short of meeting these criteria. Firstly, due to broad applicability and a low false-positive rate5, the point-by-point comparison method (evaluated by the similarity index11 or Hamming distance36) is widely used11,37,38,39,40,41. However, this method shows poor noise tolerance, due to sensitivity to pixel level intensity information42 which is prone to being influenced by some common noise sources. Secondly, contemporary artificial intelligence (AI)-driven methods9,12,16,43 can achieve a low false-positive rate and be noise-resilient by learning robust feature representations with deep neural networks. Unfortunately, these approaches frame authentication as an image classification problem, which results in substantial time wastage in the training phase. Specifically, learning classifiers12 typically requires the collection of numerous training samples for a single PUF label and necessitates the retraining of data from all PUF labels whenever a new PUF label is produced43. Another AI-enhanced technique, known as deep metric learning44, directly learns the optimal standard of comparison between data based on deep image features, enabling it not only to authenticate unseen objects45 but also to be noise-robust46. Therefore, metric learning is emerging as a promising candidate to solve the existing drawbacks of both the point-by-point comparison and classification methods.

This paper presents the first demonstration of high-dimensional (3D) encoding for diamond-based PUF labels, based on our previously reported linear polarization modulation (LPM) of NV centers in fluorescent nanodiamonds (FNDs)47, as shown in Fig. 1a. Under the readout time of around 7.5 s, we achieved an encoding capacity of 910 × 1024 (109771) for digitized images with high distinguishability, reproducibility, and long-term stability proved by a point-by-point comparison method. Moreover, we redefine the authentication problem as a metric learning task and propose a deep metric learning algorithm for robust authentication, based on comparing the similarity of abstracted deep features, as illustrated in Fig. 1b. Our method is well-motivated and allows the model to amply satisfy practical application requirements. Specifically, noise resilience evaluation demonstrates that our metric learning method effectively addresses the noise sensitivity issue inherent in the point-by-point comparison method, which is commonly encountered during an end user’s readout. In addition, when compared to previous AI-driven methods that formulate the authentication problem as a deep classification task, our reformulation exhibits two clear benefits: (1) a reduced requirement for training data volume (only two sets of data are needed for a label), and (2) the capacity to effectively authenticate data from unseen labels, rather than necessitating retraining the whole system once a new label is added43. These dual efficiencies significantly enhance the potential of our method for deployment in large-scale commercial settings.

Results

LPM curves of FNDs providing feasibility for 3D anticounterfeiting

Diamond provides promising material properties for fabricating PUF labels, including high photostability, long-term stability, and tolerance to physical stress. Specifically, both the Raman signal of diamond and the fluorescent signal of NV centers can be continuously emitted without blinking or bleaching31,32,38, which provides the basis for maintaining the reproducibility of optical readout results. In addition, high hardness35 and inertness34 make diamond-based labels tolerant to physical stress and long-term storage, respectively. However, despite the huge potential of existing diamond-based PUF labels38,39,48, it has not yet been possible to achieve the much-desired high-dimensional (>2D) encoding. We here propose a method to achieve a 3D encoded diamond-based PUF label, based on the LPM47 curves of FNDs with random orientations.

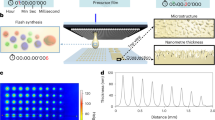

Fabricated via an electrostatic absorption approach (see section “Methods” for details), our PUF label is composed of FNDs with both high density and satisfactory dispersion on the cover glass (see SEM image in Fig. 2b). Due to the above two characteristics, there are 200–450 bright spots (BSs) over 30 × 30 µm area with a high probability close to diffraction-limited size, in fluorescent images of FND PUF labels. A typical example is given in Fig. 2a. As for the 3D anticounterfeiting information from FND PUF labels, the large number of BSs provides the basis for the distinguishability of encoded images (see Supplementary Notes 1 for detailed analysis), and diffraction-limited sizes of BSs are essential for sensitive optical readout (see latter content for details). In terms of more sample information, sample performance optimization data can be found in Supplementary Notes 6, and characteristics of FND distribution within BSs are shown in Fig. S6.

a A typical wide-field fluorescent image of FNDs. Insert: an enlarged view of six marked bright spots. b A representative SEM image of FNDs. c LPM curves corresponding to the six marked bright spots in (a). \({I}_{\beta }\): the fluorescent intensity. \(\beta\): the linear polarization direction of the excitation laser. d Histogram of LPM contrast distribution among all the identified bright spots in (a). All the scale bars are 2 µm.

In the fluorescent images of our FND PUF labels, diffraction-limited BSs with LPM curves provide the foundation for obtaining three-dimensional anticounterfeiting information. Specifically, based on the optical polarization selective excitation phenomenon of NV centers30, the LPM curves show the relationship between the polarization direction of linearly polarized excitation laser (\(\beta\)) and fluorescent intensity of FNDs (\({I}_{\beta }\)) (Fig. 1a). In actual measurement, when \(\beta\) is changed at a constant speed through rotating a half-wave plate with an electric rotation stage, wide-field fluorescent images are taken for a PUF label with a gap of \(\beta\) as 6° (see section “Methods” for more details). To exactly extract the fluorescent signal corresponding to diffraction-limited BS (size is around 10 pixels × 10 pixels), \({I}_{\beta }\) is calculated via the total signal of 13 pixels × 13 pixels matched with the identified position. Experimental results show that the LPM curves of the identified diffraction-limited BSs can be well fitted (solid lines in Fig. 2c) via Eq. 147 with a coefficient of determination usually larger than 0.85.

Where \({A}_{1},{A}_{2},\alpha\) are fitting parameters (\({A}_{1} \, > \, 0,{A}_{2} \, > \, 0\)), and \({I}_{\beta }\), \(\beta\) are input parameters. Examples of six fitted LPM curves are shown in Fig. 2c. It should be noted that these LPM curves show different LPM contrast values (\(\frac{{A}_{2}}{{A}_{1}}\)) and LPM phase (the fitting result of \(\alpha\)), corresponding to different orientations of FNDs. Therefore, based on the fluorescent images under different \(\beta\) values, it is possible to obtain the 3D encoded information, including LPM contrast values, LPM phases, and the positions of the diffraction-limited BSs.

For achieving a sensitive optical readout of the above 3D anticounterfeiting information, a sufficiently high LPM contrast value is required. We define the following criteria to determine a sufficiently high LPM contrast value: larger than 15%, which is 10 times the fluorescent intensity error (around 1.5%) in long-term detection (Fig. S1). Experimental results show that diffraction-limited BSs own LPM contrast values usually larger than 15%, but the LPM contrast values of bigger BSs have a high probability of less than 15% (Fig. S2). Therefore, the crucial point to obtain a sufficiently high LPM contrast value is the high probability of finding diffraction-limited BSs. Our PUF label is well matched with this crucial point (see the previous description of Fig. 2a), which causes a high ratio of obtaining high enough contrast values. A typical example is given in Fig. 2d: 215 of 306 identified BSs own LPM contrast values larger than 15%.

Anticounterfeiting performance of 3D encoded images

Then, based on the above-mentioned 3D anticounterfeiting information, we proposed a 3D encoding scheme to obtain digitized images. With the classical and widely used authentication method called point-by-point comparison5, the anticounterfeiting performances of digitized images were tested for distinguishability, reproducibility, long-term stability, and stability under sonication.

Digitized results were obtained based on the optical images of FND PUF labels under different \(\beta\) values with pixel resolution of 32 × 32 (see section “Methods” for details). To effectively show the information in the two dimensions including LPM contrast value and LPM phase, a feasible method is to utilize the relative change of \({I}_{\beta }\) corresponding to different \(\beta\). To reflect this relative change, we convert the photon number to contrast values in the image pixels via Eq. 2:

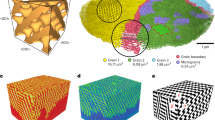

Where \({{\mbox{contrast}}}_{\beta={\mbox{n}}}\) and \({{\mbox{counts}}}_{\beta=n}\) mean the contrast values and photon number in image pixels, respectively, with the condition of \(\beta=n\). In the digitization process, nine contrast levels are set according to Table S3, which is designed based on the precision and range of the contrast value. An example of the digitized images is given in Fig. 3a: there are three encoding dimensions, including contrast levels, polarization angles, and pixel position. Calculated via the inserted formula5,11 in Fig. 3a, the encoding capacity of our PUF label can arrive at 910 × 1024 (109771), which is much larger than the commonly suggested minimum encoding capacity (10300)5. In addition, the readout time corresponding to these digitized images is just 7.5 s. Therefore, we achieved a sufficiently large encoding capacity as the basis for unbreakable encryption, within a relatively short readout time.

a Digitized results of obtained wide-field fluorescent images under different laser polarization directions (\(\beta\)). Insert: the formula to calculate the encoding capacity. Image resolution: 32 pixels × 32 pixels. b Authentication results for two groups of digitized readouts results of 300 PUF labels. Left panel: heating map showing pairwise match. Color bar represents the similarity index. Right panel: histogram showing the statistics of similarity indexes among digitized readout results for the different PUF labels (red bars) and the same PUF labels (blue bars). c Histogram showing the statistics of similarity indexes among digitized results for repeated readouts of the same PUF label. d Long-term stability curves for the readout results of 3D anticounterfeiting information.

To demonstrate the feasibility of the above encoding method in distinguishing different PUF labels, we applied the broadly used authentication method called point-by-point comparison5. Specifically, when two groups of digitized images are compared pixel-by-pixel, the ratio of the same pixels is recorded as the similarity index11. If there exists an evident gap between the similarity indexes of the same labels and different labels, a threshold value within the gap can be chosen to correctly distinguish the different PUF labels. In our authentication process, the similarity indexes are calculated among the two groups of digitized images for 300 PUF labels. Calculation results are shown in Fig. 3b: the similarity indexes of the same labels are always higher than 76%, and the similarity indexes of the different labels are always less than 70%. Therefore, we can choose the threshold value as 75% (within the gap of 70–76%) to successfully distinguish all the 300 PUF labels.

Moreover, based on the above threshold value, we evaluated the reproducibility, long-term stability, and stability under sonication of the digitized readout results for our PUF label. First, for reproducibility, we calculated the similarity indexes among 10 groups of digitized images for the same PUF label. All the authentication results for 20 PUF labels show satisfactory reproducibility in Fig. 3c: the similarity indexes are always significantly higher than the threshold value (75%) (see Fig. S3 for specific examples of the reproducibility of a specific label). Then, long-term stability was tested based on repeated readout results of nine PUF labels for a period of around 159 days. For each readout date, corresponding similarity indexes are calculated between the digitized readout results on this date and the digitized readout results on the first day. The authentication result confirmed satisfactory long-term stability: the similarity indexes are always evidently higher than the threshold value (75%) (Fig. 3d). Finally, stability under sonication was tested via comparing authentication results about identical eight labels in two conditions: (1) with sonication, and (2) without sonication. Test results (Fig. S7) show the satisfactory stability that sonication causes a little influence on the similarity index distribution, and different labels always can be successfully distinguished via the threshold value (75%).

Deep metric learning for authenticating noise-affected digitized images

In terms of practical authentication for anticounterfeiting labels, the system’s tolerance to common noise sources is crucial. Specifically, in the practical authentication process, manufacturers provide images taken under ideal laboratory conditions, but end users may employ images taken in environments saturated with various additional noise sources. Even if the optical signal from a PUF label is stable, these noise sources influence the readout process, which might prevent the authentication algorithms (i.e., point-by-point comparison) from working42.

To this end, simulating the actual authentication process, we conduct a noise resilience evaluation for point-by-point comparison method with FND PUF label. In the noise resilience evaluation, images of PUF labels taken under two different optical readout conditions are used for authentication based on the similarity index, as shown in the left panel of Fig. 4a. Specifically, our experiment mirrors the image capture process by both the manufacturer and the end users, where an optical readout of 150 PUF labels was conducted under ideal laboratory conditions and laboratory conditions contaminated with three kinds of noise sources, respectively (refer to Supplementary Notes 3 for details). These noise sources include background light, sample drift, and out-of-focus, all of which are common noise sources for the readout process. Digitized images corresponding to the above two optical readout conditions show evident differences, with a typical example in the right panel of Fig. 4a. As shown in Fig. 4b, experimental results show that there is an overlap between the distributions of the similarity index for intra-digitized images and inter-digitized images. This implies that it is impossible to find an appropriate threshold to distinguish PUF labels. In noise resilience evaluation results for other PUF labels based on point-by-point comparison42, negative results have also been found and were attributed to the widespread limitation of the point-by-point comparison method, i.e., sensitive to some noise sources. Therefore, this highlights the need for a more robust authentication algorithm.

a Digitized images (right panel) of the same FND PUF label corresponding to different optical readout conditions (left panel). b, c Authentication results for the digitized images of 150 FND PUF labels captured under the two optical readout conditions in (a). Heat map (b) showing the pairwise match; the color bar reflects the similarity index. Histogram (c) displaying the statistics of similarity indexes among digitized readout results for the different FND PUF labels (red bars) and the same FND PUF labels (blue bars).

To develop a more robust algorithm tolerant of noise, our key inspiration was that it was hard, using the naked eye, to differentiate digitized images of a PUF label in the presence of noise (such as Fig. 4a). However, it is possible for us to recognize natural images with the naked eye, even when they are mixed with noise49. The reason is that most of the noise in our daily life affects information at the pixel level, while we have seen many natural images and have been “trained” to recognize them based on high-level semantic information50. Thus, to solve the challenge in noise resilience evaluation, the critical factor is to show our machine as many PUF labels as possible at a training stage (i.e., prior information). It is essential to provide the model with training data, which are used to teach it to discern high-level information crucial for distinguishing samples and enhancing noise resilience.

Given the profound capacity of deep learning51,52,53 to learn prior information and the ability of a convolutional neural network (CNN) to extract deep patch-level features from images, we propose to exploit these features for our authentication system. In particular, we propose the use of deep metric learning44 to conduct anticounterfeiting authentication. Specifically, metric learning excels at identifying essential differences between data instances, making it well-suited for authentication tasks. By learning a distance metric that reflects intrinsic similarities and dissimilarities among instances, metric learning has demonstrated effectiveness in actual applications such as robust face verification in the wild54, variation-tolerant face recognition46,55, and person re-identification56.

The core concept of metric learning, as shown in Fig. 5a, is to enable the accurate clustering of images based on their content, even when subjected to noise or distortions. In the original image space depicted on the left side of Fig. 5a, we have an image \({I}_{X}\), which becomes more distant from its original position when affected by noise, resulting in the image \({I}_{X\hbox{'}}\). Consequently, if we measure the distance with the point-by-point comparison, image \({I}_{X}\) becomes closer to another image \({I}_{Y}\), which could cause a wrong matching. To tackle this issue, our metric learning framework utilizes a neural network trained to extract noise-resistant features, allowing images with similar content to be accurately categorized together, as depicted on the right side of Fig. 5a. In other words, high-level information of the digitized image is extracted and represented like a deep key in the metric space. In this way, we can compare digitized images’ similarity by calculating a similarity score (see section “Methods” for more details) in the metric space, instead of a point-by-point comparison in the original image space.

a Schematic diagram showing the design and insight of our metric learning framework. CNN: convolutional neural network. b Schematic diagram showing the training process of CNN in one loop. c, d Authentication results for the 150 pairs of digitized images used in Fig. 4b, c. Heat map (c) showing the pairwise match; the color bar reflects the similarity score. Histogram (d) displaying the statistics of similarity scores among digitized readout results for the different FND PUF labels (red bars) and the same FND PUF labels (blue bars).

To achieve this goal, the key innovation of metric learning lies in its unique training strategy. As shown in Fig. 5b, a deep neural network is trained to bring features (i.e., \({F}_{X}\) and \({F}_{X\hbox{'}}\)) belonging to the same PUF label closer together while pushing features (i.e., \({F}_{Y}\) and \({F}_{X\hbox{'}}\)) from different PUF labels further apart. Before training, features from the same label might be far apart in the metric space (or too close to a different label), which is contrary to our desired outcome. In such cases, the loss function penalizes the network, forcing it to adjust its parameters in the appropriate direction via back-propagation. After several iterations, our network learns how to extract the key information from images, resulting in a metric space where features of the same label are close together, and features of different labels are farther apart. Compared to similarity index based on point-by-point comparison, neural networks typically extract patch-level structural features, which are more resilient to noise.

We demonstrate the robustness of our method against a variety of noise sources commonly encountered during the readout process. Especially, during training, we do not assume prior knowledge about the noise that may present in practical use and apply PUF data from the ideal condition for training. This avoids introducing biased evaluation results. For validation, we use the same 150 pairs of PUF images employed in Fig. 4b. Notably, the PUF labels used for training are completely different from the PUF labels in the test set, thereby preventing any overfitting issue in our test results (see section “Methods” for more details). As depicted in Fig. 5c, d, even under challenging conditions, our method accurately distinguishes between different pairs of PUF labels and identical pairs of PUF labels with 100% precision. It can be seen that there is a significant gap (~13%–23%) between the similarity score distributions of intra-class PUF labels and inter-class PUF labels. By contrast, authentication with point-by-point comparison reveals a tendency to confusion (see Fig. 4b, c). These results demonstrate that our algorithm can recognize PUF labels better than the point-by-point comparison method in the presence of the investigated noise sources. Additionally, we provide validation results of our method under ideal conditions in Fig. S4, highlighting even more distinct decision boundaries. This further proves the robustness and reliability of our metric learning-based approach for accurate PUF label authentication, whether under ideal conditions or in real-life noise environments.

Characteristics of metric learning method compared to prior AI-driven methods

Prior to our work, there have been some AI-driven methods9,12,43 for tackling PUF label authentications. These methods typically formulate the problem as a discriminative image classification task which learns to map a data pattern to a category. In contrast, we redefine the problem as a deep metric learning problem, focusing on learning a similarity measurement between two samples using deep features to assess whether they are from the same label or not. Here, we analyzed the difference between our metric learning-based authentication method and classification-based authentication methods in the training and testing stages.

First, our method is more data-efficient during the training phase. Specifically, classification methods learn to map a data pattern to a category by predicting the probability for each category given an input. Since the mapping differs across categories, this requires a lot of data for each category for training (Fig. 6a). If there is not enough data for a category, the model is prone to overfitting the training data and performs poorly during testing57. The experimental demonstration can be found in Supplementary Notes 9. Our metric learning, on the other hand, focuses on learning a similarity measurement to evaluate whether a given pair of readout results are similar or not, specifically, predicting a similarity score for a pair of readout results. This task can be accomplished with pairs or triplets of samples (a reference sample, a positive sample from the same category, and a negative sample from a different category). Our training stage requires only two groups of readout results from each label (Fig. 6a), because the similarity measurement can be shared among different PUF labels57: with \(N\) readouts from PUF labels, our method derives \({C}_{N}^{2}\) unique pairs for training, leading to a much larger number of data pairs than classification methods (i.e., \({C}_{N}^{2} > > N\)). In sum, our method needs much less training data, thereby saving a lot of time that would otherwise be consumed in the repeated readout of PUF labels.

a Schematic diagram showing the difference in the amount of data required during the training process. b Schematic diagram showing the difference in the authentication process and the capability to authenticate unseen PUF labels, where the classifier cannot evaluate unseen class labels based on predicted class probabilities. “Key” denotes the anticounterfeiting information from a single readout of a PUF label.

Second, our method can effectively authenticate new PUF labels unseen during training (Fig. 5c, d), a capability that classification-based methods lack9,12,43. As shown in Fig. 6b, classification methods fix the number of categories (e.g., 10) during the training phase. In this case, the model predicts the probabilities of 10 categories and utilizes the highest one to determine the class to which a PUF label belongs. Consequently, if a provider manufactures a new 11th PUF label, the network will still only predict probabilities of 10 categories. Under these circumstances, the method would either predict all 10 probability values to be low, thereby deeming the label to be false, or one probability might be high, leading to an incorrect classification of the label (see Fig. S14). Although the features learned in the penultimate layer can indeed be utilized for unseen label authentication in a classifier, similar to the operation of deep metric learning in the testing phase, the efficacy of this approach remains unsatisfactory. This is supported by studies such as DeepFace58 and ArcFace59, which indicate that metric learning is still necessary, whether explicitly or implicitly, to facilitate the learning of discriminative features for unseen label inference through pairwise feature comparisons. A classification model trained using basic SoftMax loss, akin to recent approaches in the PUF authentication field, exhibits poor performance in similarity comparison for unseen labels when using the method described above. We confirmed these findings through additional experiments, as detailed in Supplementary Notes 9 (Experiment 3). By contrast, our method compares whether two readout results of PUF labels are similar, and the learned similarity metric can be applied for new PUF labels. Consequently, even if we only use digitized images of certain PUF labels (such as PUF1-PUF10) during the training stage, we can still compare two new readout results (for instance, from PUF11 and PUF12), as shown in Fig. 6b. The experimental demonstration can be found in Figs. 5c, d and S4, where all our experimental evaluations are on unseen labels. Therefore, our method is well-suited for use in real-world business situations where new PUF labels are continually being created, while the classification technique’s requirement for retraining makes it inconvenient to use in such conditions.

Discussion

Combining the advantages of both FNDs sample and our 3D encoding scheme, LPM of FND is a promising candidate to achieve a useful PUF label, which can satisfy most common requirements in both the aspects of commercial and anticounterfeiting performances. Specifically, common commercial requirements5 contain (1) low-cost and scalable fabrication and (2) convenient and fast readout. As for our FND PUF label, the estimated cost of a working label is considerably lower than 0.19 USD (Table S1). Its simple fabrication method using a mature commercial sample (see section “Methods” for details) offers the opportunity for scalable fabrication, and the strong optical signal of FNDs (Fig. S5) provides the basis for fast optical readout (in our scheme, integration time for an image is 50 ms, and total readout time is 7.5 s). In addition, some common requirements for anticounterfeiting performances of PUF labels are listed as (1) high encoding capacity for achieving unbreakable encryption5, (2) reproducible authentication results11, and (3) labels available for precise authentication within a long time. Authentication results (Fig. 3) prove that our FND PUF label is well able to meet these requirements: encoding capacity as high as 109771 with satisfactory distinguishability, reproducible authentication for 10 times of readout results of the same labels, and stable anticounterfeiting information for a period of around 159 days.

Other two core points about FND PUF label should be stressed here. Firstly, compared with three representative 3D encoded labels (Table S2), our 3D encoding scheme shows two advantages: (1) a higher encoding capacity under the same image pixel conditions; (2) simplified label fabrication requiring only one type of “ink”, i.e., FNDs. Secondly, an existing main challenge is achieving cost-effective and user-friendly readout device, which is crucial in practical usage. Fortunately, rapid development of portable microscopy points towards a promising solution to overcome this obstacle (see Supplementary Notes 5 for details).

Building on the similarity score extracted from the deep features of two sets of digitized results, we propose a metric learning authentication method showing better noise resilience and higher training efficiency than prior AI-driven methods. Specifically, unlike the previous classification method12 that uses the same artificially created “noise” or disruptions during both the training and testing phases, our CNN network is trained via data readout under ideal laboratory conditions, but demonstrates robust noise tolerance in evaluations (refer to Fig. 5b, c). This proves that our method potentially has a better capability to handle data readout in a variety of real-world scenarios. In addition, in contrast to the classification approach9,12,43, in which a large amount of training data for each PUF label is needed and repeated training is required when new labels are introduced, our method requires only two sets of readout results for each PUF label and obviates the need for retraining in the event of encountering new objects, thereby saving a lot of time. Our metric learning approach is flexible and can accommodate various PUF shapes due to its learning-based nature. We believe that our innovative approach will offer valuable insights into the PUF authentication field, encouraging real-world implementations and inspiring future research.

Our authentication method can also well satisfy the common requirements in practical usage: high enough authentication velocity and availability for product traceability. First, in our authentication method, the time of comparing digitized images with one set of stored objects is 1.38 ms, which is sufficiently rapid for practical use with a well-matched design of the authentication process (see Supplementary Notes 4 for detailed analysis). Secondly, in many previously established product traceability algorithms11,14,37, traditional point-by-point comparison methods play a crucial role in determining whether the two groups of encoded images belong to the same label. Seamlessly sharing the above role, our deep metric learning method aligns well with these algorithms.

Methods

Experimental apparatus

All fluorescent images for the FND PUF labels were taken by a customized wide-field fluorescence microscope. In the excitation optical path, the linear polarization direction of a continuous 532 nm laser is changed via a half-wave plate (WPH10M-532, Thorlabs) mounted on the electrical rotation stage (PT-GD62, PDV). Employing the above half-wave plate and a polarizer to control and verify the initial laser polarization direction (\(\beta=0\)), we can maintain a consistent initial laser polarization direction. The excitation laser is then focused on the back-focal plane of an oil immersion objective (NA 1.45, UPLXAPO100XO, Olympus) to illuminate the sample. The sample position can be finely adjusted via a nanopositioning stage (P561.3CD, Physik Instrumente). In the detection optical path, filtered with a long pass filter (FELH0650, Thorlabs), the fluorescence signal is detected via a water-cooled EMCCD (iXon Ultra 897, Andor) with a field of view of around 30 × 30 μm.

Fabrication of FND PUF label

The PUF label is fabricated by FND-COOH containing ensemble NV centers (BR100, FND Biotech, Inc.) through electrostatic absorption. Specifically, cover slides are activated by plasma for 10 min (200 W), and then immersed into the 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES, Sigma) solution in ethanol (v/v,5%). After reaction for 24 h at room temperature, the cover slides are taken out and washed with ethanol and water, respectively. After that, 0.02 mg/mL FND solution is drop-casted on the obtained positive-charged cover glass and incubated in the refrigerator for 3 h. Next, the obtained samples are washed with DI water and dried in air. Finally, a PDMS layer is coated onto the cover glass as a protection layer. Supplementary Notes 7 shows the influence of PDMS layer on the readout results of three encoding dimensions.

Particle location code

We use the peak location function (pkfind()) and spatial bandpass filter function (bpass()) in MATLAB particle location code from Daniel Blair and Eric Dufresne (https://site.physics.georgetown.edu/matlab/index.html). The spatial bandpass filter function is used to filter the noise from wide-field fluorescent images. The peak location function is then used to identify and locate the BSs. Without special instruction, the wide-field fluorescent images described in formal content and supporting information have been processed via spatial bandpass filter.

Measurement of LPM curves

First, wide-field fluorescent images of FND PUF label are taken with 6° gap of linear polarization direction of the excitation laser, 50 ms integration time, and around 10 mW laser power. Then, with the peak location function, we identify and locate BSs with threshold value as 3000 counts and spot size as 10 pixels. Next, the total signals of the 13 pixels × 13 pixels matched with the location of identified BSs are calculated as fluorescent intensity. Finally, the LPM curve is recorded as the relationship between fluorescent intensity and the linear polarization direction of the excitation laser. The recorded LPM curve is fitted via the curve fitting function (fit()) in MATLAB based on Eq. 1.

Optical readout and digitization

First, with parameters of 512 × 512 pixel resolution, 50 ms integration time, and around 10 mW laser power, wide-field fluorescent images of FND PUF label are taken under polarization directions of excitation laser as 0, 36, 48, 60, 72, 84, 96, 108, 120, 132, 144°. Next, by accumulating the total signal of 16 pixels × 16 pixels into a new pixel, we change the pixel resolution to 32 × 32. Then, contrast values for each pixel are calculated via Eq. 2. Finally, contrast values are digitized as shown in Table S3. Using the Lenovo Xiaoxin Pro16 laptop with i5-13500H CPU, it takes ~0.16 s to encode a set of readout results.

Training of metric learning

As shown in Fig. S13, the network used is a Siamese network, a type of CNN that processes two inputs concurrently and extracts their deep features. When provided with two digitized images X and X’, the Siamese network extracts their corresponding features as follows:

Within our metric learning framework, the objective is to maximize the cosine similarity between F and F’ if X and X’ belong to the same PUF label, and to minimize the similarity if they belong to different PUF labels. To achieve this, the CNN needs to extract the most notable characteristics of a PUF label that differentiate it from other labels. These features are often patch-level, preserve robust structural information, and exhibit greater resilience to noise. To train the network, we calculate the cosine similarity of feature maps and use the Focal loss to update the CNN. The model employs the Adam60 optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.0001. It is trained with a batch size of 32 for up to 10,000 iterations. Further details regarding the network architecture, cosine similarity calculation, and loss function can be found in Supplementary Notes 8.

Our training and testing datasets are completely distinct. For training, we utilized 240 pairs of readout results under ideal conditions from 240 different PUF labels. For testing, we employed 60 pairs of readout results under ideal conditions from 60 unique PUF labels for standard testing (i.e., results in Fig. S4) and 150 pairs under noisy conditions from 150 distinct PUF labels for noise robustness testing (i.e., results in Fig. 5c, d). Notably, these 450 PUF labels are entirely separate from one another.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information file. The fluorescent images of PUF labels with corresponding digitized images used for the PUF authentication have been deposited in the repository https://github.com/PBBlabwlz/PUF_Label, and a snapshot of the data is provided on Zenodo61. All other data that support the findings of the study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

All codes used for encoding fluorescent images and PUF authentication are available via https://github.com/PBBlabwlz/PUF_Label, and a snapshot of the code is provided on Zenodo61.

References

Hardy, J. Estimating the global economic and social impacts of counterfeiting and piracy. World Trademark Review. https://www.worldtrademarkreview.com/global-guide/anti-counterfeiting-and-online-brand-enforcement/2017/article/estimating-the-global-economic-and-social-impacts-of-counterfeiting-and-piracy (2017).

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)/European Union Intellectual Property Office. Trade in Counterfeit and Pirated Goods: Mapping the Economic Impact (OECD Publishing, 2016).

Aldhous, P. Murder by medicine. Nature 434, 132–134 (2005).

Mackey, T. K. & Nayyar, G. A review of existing and emerging digital technologies to combat the global trade in fake medicines. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 16, 587–602 (2017).

Arppe, R. & Sørensen, T. J. Physical unclonable functions generated through chemical methods for anti-counterfeiting. Nat. Rev. Chem. 1, 0031 (2017).

Suh, G. E. & Devadas, S. Physical unclonable functions for device authentication and secret key generation. In Proc. 44th ACM Annual Design Automation Conference 9–14 (ACM, 2007).

Fighting counterfeiting at the nanoscale. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 497 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-019-0484-0 (2019).

Smith, A. F., Patton, P. & Skrabalak, S. E. Plasmonic nanoparticles as a physically unclonable function for responsive anti-counterfeit nanofingerprints. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 1315–1321 (2016).

Smith, J. D. et al. Plasmonic anticounterfeit tags with high encoding capacity rapidly authenticated with deep machine learning. ACS Nano 15, 2901–2910 (2021).

Lu, Y. et al. Dynamic cryptography through plasmon-enhanced fluorescence blinking. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2201372 (2022).

Gu, Y. et al. Gap-enhanced Raman tags for physically unclonable anticounterfeiting labels. Nat. Commun. 11, 516 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Inkjet-printed unclonable quantum dot fluorescent anti-counterfeiting labels with artificial intelligence authentication. Nat. Commun. 10, 2409 (2019).

Kustov, P. et al. Mie-resonant silicon nanoparticles for physically unclonable anti-counterfeiting labels. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 5, 10548–10559 (2022).

Carro-Temboury, M. R., Arppe, R., Vosch, T. & Sørensen, T. J. An optical authentication system based on imaging of excitation-selected lanthanide luminescence. Sci. Adv. 4, e1701384 (2018).

Chen, F. et al. Unclonable fluorescence behaviors of perovskite quantum dots/chaotic metasurfaces hybrid nanostructures for versatile security primitive. Chem. Eng. J. 411, 128350 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Triple-layer unclonable anti-counterfeiting enabled by huge-encoding capacity algorithm and artificial intelligence authentication. Nano Today 41, 101324 (2021).

Li, J., He, C., Qu, H., Shen, F. & Ye, J. Five-dimensional unclonable anticounterfeiting orthogonal Raman labels. J. Mater. Chem. C 10, 7273–7282 (2022).

Liu, S., Liu, X., Yuan, J. & Bao, J. Multidimensional information encryption and storage: when the input is light. Research 2021, 7897849 (2021).

Geng, J. Three-dimensional display technologies. Adv. Opt. Photonics 5, 456–535 (2013).

Han, Y. & Li, G. Coherent optical communication using polarization multiple-input-multiple-output. Opt. Express 13, 7527–7534 (2005).

Gu, M., Li, X. & Cao, Y. Optical storage arrays: a perspective for future big data storage. Light Sci. Appl. 3, e177 (2014).

Li, X., Lan, T. H., Tien, C. H. & Gu, M. Three-dimensional orientation-unlimited polarization encryption by a single optically configured vectorial beam. Nat. Commun. 3, 998 (2012).

Backlund, M. P., Lew, M. D., Backer, A. S., Sahl, S. J. & Moerner, W. E. The role of molecular dipole orientation in single-molecule fluorescence microscopy and implications for super-resolution imaging. ChemPhysChem 15, 587–599 (2014).

Zhang, O. et al. Six-dimensional single-molecule imaging with isotropic resolution using a multi-view reflector microscope. Nat. Photonics 17, 179–186 (2023).

Forkey, J. N., Quinlan, M. E., Alexander Shaw, M., Corrie, J. E. T. & Goldman, Y. E. Three-dimensional structural dynamics of myosin v by single-molecule fluorescence polarization. Nature 422, 399–404 (2003).

Chen, K. et al. Characteristic rotational behaviors of rod-shaped cargo revealed by automated five-dimensional single particle tracking. Nat. Commun. 8, 887 (2017).

Kim, J. et al. Monitoring the orientation of rare-earth-doped nanorods for flow shear tomography. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 914–919 (2017).

Lu, W., Wang, D. & Chen, L. Near-static dielectric polarization of individual carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 7, 2729–2733 (2007).

Tran, T. T., Bray, K., Ford, M. J., Toth, M. & Aharonovich, I. Quantum emission from hexagonal boron nitride monolayers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 37–41 (2016).

Alegre, T. P. M., Santori, C., Medeiros-Ribeiro, G. & Beausoleil, R. G. Polarization-selective excitation of nitrogen vacancy centers in diamond. Phys. Rev. B 76, 165205 (2007).

Kurtsiefer, C., Mayer, S., Zarda, P. & Weinfurter, H. Stable solid-state source of single photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 290–293 (2000).

Yu, S. J., Kang, M. W., Chang, H. C., Chen, K. M. & Yu, Y. C. Bright fluorescent nanodiamonds: no photobleaching and low cytotoxicity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 17604–17605 (2005).

Chang, Y. R. et al. Mass production and dynamic imaging of fluorescent nanodiamonds. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 284–288 (2008).

Chipaux, M. et al. Nanodiamonds and their applications in cells. Small 14, e1704263 (2018).

Blank, V. et al. Ultrahard and superhard phases of fullerite C60: comparison with diamond on hardness and wear. Diam. Relat. Mater. 7, 427–431 (1998).

Maiti, A., Gunreddy, V. & Schaumont, P. A systematic method to evaluate and compare the performance of physical unclonable functions. in Embedded Systems Design with FPGAs 245–267 (Springer, 2013).

Leem, J. W. et al. Edible unclonable functions. Nat. Commun. 11, 328 (2020).

Hu, Y. W. et al. Flexible and biocompatible physical unclonable function anti‐counterfeiting label. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2102108 (2021).

Zhang, T. et al. Multimodal dynamic and unclonable anti-counterfeiting using robust diamond microparticles on heterogeneous substrate. Nat. Commun. 14, 2507 (2023).

Kim, J. H. et al. Nanoscale physical unclonable function labels based on block copolymer self-assembly. Nat. Electron. 5, 433–442 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. An all-in-one nanoprinting approach for the synthesis of a nanofilm library for unclonable anti-counterfeiting applications. Nat. Nanotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-023-01405-3 (2023).

Arenas, M., Demirci, H. & Lenzini, G. Cholesteric spherical reflectors as physical unclonable identifiers in anti-counterfeiting. In Proc. The 16th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security 1–11 (ACM, 2021).

Sun, N. et al. Random fractal-enabled physical unclonable functions with dynamic AI authentication. Nat. Commun. 14, 2185 (2023).

Hoffer, E. & Ailon, N. Deep metric learning using triplet network. in Similarity-Based Pattern Recognition 84–92 (Springer, 2015).

Zhai, A. & Wu, H. Y. Classification is a strong baseline for deep metric learning. In British Machine Vision Conference (BMVC, 2019).

Schroff, F., Kalenichenko, D. & Philbin, J. FaceNet: a unified embedding for face recognition and clustering. In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 815–823 (IEEE, 2015).

Wang, L. et al. All-optical modulation of single defects in nanodiamonds: revealing rotational and translational motions in cell traction force fields. Nano Lett. 22, 7714–7723 (2022).

Kehayias, P., Bussmann, E., Lu, T. M. & Mounce, A. M. A physically unclonable function using NV diamond magnetometry and micromagnet arrays. J. Appl. Phys. 127, 203904 (2020).

Pinto, N., DiCarlo, J. J. & Cox, D. D. How far can you get with a modern face recognition test set using only simple features? In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2591–2598 (IEEE, 2009).

Oliva, A. & Torralba, A. Modeling the shape of the scene: a holistic representation of the spatial envelope. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 42, 145–175 (2001).

LeCun, Y. et al. Backpropagation applied to handwritten zip code recognition. Neural Comput. 1, 541–551 (1989).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 60, 84–90 (2017).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. In Proc. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR, 2015).

Hu, J., Lu, J. & Tan, Y. P. Discriminative deep metric learning for face verification in the wild. In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 1875–1882 (IEEE, 2014).

Liu, W. et al. SphereFace: deep hypersphere embedding for face recognition. In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 212–220 (IEEE, 2017).

Yang, X., Wang, M. & Tao, D. Person re-identification with metric learning using privileged information. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 27, 791–805 (2019).

Song, H. O., Xiang, Y., Jegelka, S. & Savarese, S. Deep metric learning via lifted structured feature embedding. In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 4004–4012 (IEEE, 2016).

Taigman, Y., Yang, M., Ranzato, M. A. & Wolf, L. Deepface: closing the gap to human-level performance in face verification. In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 1701–1708 (IEEE, 2014).

Deng, J., Guo, J., Xue, N. & Zafeiriou, S. Arcface: additive angular margin loss for deep face recognition. In Proc. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 4685–4694 (IEEE, 2019).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. In Proc. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR, 2015).

Wang, L. & Yu, X. High-dimensional anticounterfeiting nanodiamonds authenticated with deep metric learning. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14058633 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Z.Q.C. acknowledges the financial support from the HKSAR Research Grants Council (RGC) Research Matching Grant Scheme (RMGS, No. 207300313); HKU Seed Fund; and the Health@InnoHK program of the Innovation and Technology Commission of the Hong Kong SAR Government. X.J.Q. acknowledges the financial support from the HKSAR RGC Early Career Scheme (No. 27209621), General Research Fund (No. 17202422), and Research Matching Grant Scheme. D.Y.L. acknowledges the financial support of the Innovation and Technology Commission of Hong Kong through the Guangdong-Hong Kong Technology Cooperation Funding Scheme (Reference no. GHP/026/19GD).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Q.C. and X.J.Q. conceived the idea and supervised the project. L.Z.W. performed the optical measurements and analyzed data. X.Y. designed the metric learning algorithm and conducted the experiments and evaluation. Y.H. fabricated the nanodiamonds-based anticounterfeiting label. L.Z.W. and X.Y. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. T.T.Z. and D.Y.L. discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Kun Zhang, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Yu, X., Zhang, T. et al. High-dimensional anticounterfeiting nanodiamonds authenticated with deep metric learning. Nat Commun 15, 10602 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55014-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-55014-2