Abstract

Fruit ripening is a highly-orchestrated process that requires the fine-tuning and precise control of gene expression, which is mainly governed by phytohormones, epigenetic modifiers, and transcription factors. How these intrinsic regulators coordinately modulate the ripening remains elusive. Here we report the identification and characterization of FvALKBH10B as an N6-methyladenosine (m6A) RNA demethylase necessary for the normal ripening of strawberry (Fragaria vesca) fruit. FvALKBH10B is induced by phytohormone abscisic acid (ABA), and ABA-Responsive Element Binding Factor 3 (FvABF3), a master regulator in ABA signaling, is responsible for this activation. FvALKBH10B mutation leads to a delay in fruit ripening and causes global m6A hypermethylation of 1859 genes. Further analyses show that FvALKBH10B positively modulates the mRNA stability of SEPALLATA3 (FvSEP3) encoding a transcription factor via m6A demethylation. In turn, FvSEP3 targets numerous ripening-related genes including those associated with biosynthesis of ABA and anthocyanin and regulates their expression. Our findings uncover an FvABF3-FvALKBH10B-FvSEP3 cascade in controlling fruit ripening in strawberry and provide insights into the complex regulatory networks involved in this process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ripening is the final stage of fruit development that involves a series of physiological and biochemical changes in the color, flavor, aroma, and texture1. Due to the specificity of this developmental process to plant biology and its pivotal impact on fruit nutritional quality and shelf life, the ripening of fruit has attracted considerable attention. Fruit ripening is regulated by both external environmental cues and intrinsic developmental signals2. Plant hormone ethylene plays a key role in controlling the ripening of a group of fleshy fruits called climacteric fruits, e.g. tomato, apple, and banana, and substantial insights have been made toward the mechanisms of ethylene-induced fruit ripening2,3. In contrast, the ripening of another group of fleshy fruits, namely non-climacteric fruits, e.g. strawberry, grape, and citrus, appears to be ethylene-independent. Instead, abscisic acid (ABA) is responsible for the ripening of non-climacteric fruit4,5, although the molecular basis of how ABA regulates fruit ripening is poorly understood.

As one of the most important phytohormones known, ABA is synthesized via the mevalonate pathway using C40 carotenoid precursors6. In this process, 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (NCED) serves as the rate-limiting enzyme6. The ABA core signaling pathway comprises three protein classes: Pyrabactin Resistance/Pyrabactin Resistance-like/Regulatory Component of ABA Receptor (PYR/PYL/RCAR), the ABA receptors; Protein Phosphatase 2 C (PP2C) group A family, the negative regulators; SNF1-Related Protein Kinases type 2 (SnRK2s), the positive regulators7. In the absence of ABA, the ABA receptors are inactivated and the PP2C proteins inhibit the SnRK2 proteins. Upon ABA binding, the PYR/PYL/RCAR receptors inhibit PP2C activity, allowing the activation of SnRK2s through autophosphorylation. Activated SnRK2s then phosphorylate their downstream key transcriptional regulators, such as the ABA-Responsive Element Binding Factors/Proteins (ABFs/AREBs) transcription factors, which bind to the ABA-responsive element (ABRE) in the promoters of ABA-inducible genes and modulate their expression7. Recently, it was shown that repression of ABA biosynthesis or signaling by silencing of FaNCED1 or FaPYR1, respectively, inhibits fruit ripening in octoploid strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa)4,8, a typical non-climacteric fruit, but the underlying mechanisms and how ABA signaling integrates with other intrinsic cues to coordinately regulate fruit ripening remain elusive.

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most prevalent chemical modification in eukaryotic mRNAs9,10. It may impact mRNA metabolism, including mRNA stability, splicing, translation efficiency, and nuclear export11,12,13, therefore affecting multiple biological pathways. As a dynamic and reversible post-transcriptional modification, m6A is installed by the methyltransferase complex (writer) and removed by the demethylase (eraser), which belongs to the AlkB family of proteins14,15. Recognition of m6A is achieved by the “reader” proteins, such as YTH-domain family proteins and specific RNA binding proteins (RBPs)16,17. In plants, the m6A methylation has been elucidated to regulate various developmental and biological processes, such as vegetative growth18,19,20, floral transition21,22, reproductive development23,24, photomorphogenesis25,26, circadian clock27,28, and biotic and abiotic stress responses29,30,31,32. We previously uncovered that m6A modification participates in the regulation of ripening in diploid strawberry (Fragaria vesca)33 and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum)34. However, the mechanistic basis of m6A-mediated ripening control is still not well understood. Moreover, how m6A methylation is regulated remains obscure. Such information is critical for understanding the connections of m6A with other regulatory pathways in controlling fruit ripening.

In the present work, we discovered that FvALKBH10B acts as a strawberry m6A demethylase, whose expression is regulated by ABA through FvABF3. Mutation of FvALKBH10B via CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing system results in a delay in fruit ripening and global m6A hypermethylation. We further established that FvALKBH10B-mediated m6A demethylation stabilizes mRNA of SEPALLATA3 (FvSEP3) encoding a transcription factor, which in turn regulates the expression of ripening-related genes. Our study reveals the FvABF3-FvALKBH10B-FvSEP3 regulatory cascade in the control of strawberry fruit ripening, highlighting the complex relationship between ABA, epigenetic regulators, and transcription factors during ripening.

Results

FvALKBH10B is a demethylase for mRNA m6A demethylation in strawberry

We previous revealed that m6A modification represents a common feature of mRNAs in fruits of diploid strawberry F. vesca and is highly enriched around the stop codon or within the 3’ untranslated region (UTR)33. During fruit ripening, m6A depositions in these regions display a substantial decline on a large number of transcripts33, but the mechanistic basis remains unknown. We hypothesize that this process is regulated by specific m6A demethylase, which oxidatively reverses m6A in mRNAs. To identify m6A demethylase candidates in strawberry, we performed BLAST analysis, which predicted 9 potential orthologs of Arabidopsis AlkB homologs (ALKBHs)35 (Supplementary Data 1). All these strawberry ALKBH members, named based on their phylogenetic relationships with Arabidopsis ALKBHs (Fig. 1a), possess an intact and highly conserved AlkB domain (Supplementary Fig. 1a) with Fe (II) binding sites and alpha-ketoglutaramate (α-KG) binding sites (Supplementary Fig. 1b). By mining the transcriptome data of our previous analysis33, we found that, among the 9 strawberry ALKBH genes, only FvALKBH10B, the ortholog of Arabidopsis ALKBH10B21, exhibited a dramatic increase during fruit ripening, and this was confirmed by RT-qPCR (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). It should be noted that no significant decrease in gene expression of m6A writers, including the methyltransferases MTA and MTB, was observed during fruit ripening, indicating that the decline in m6A deposition in this process is not regulated by m6A writers (Supplementary Fig. 2c).

a Phylogenetic analysis of strawberry ALKBH proteins. An unrooted neighbor-joining tree was generated by MEGA (version 6). The bootstrap supporting values is showed next to the nodes (1000 replicates). Species names are abbreviated as follows: Mm Mus musculus, At Arabidopsis thaliana, Fv Fragaria vesca. b Expression pattern of FvALKBH10B as determined by RT-qPCR. RT root, ST stem, LE leaf, FL flowers, SG small green, LG large green, WF white fruit, TF turning fruit, RF red fruit. Values are means ± standard error of mean (SEM) (n = 3 biological replicates), in which ACTIN (FvH4_6g22300) was used as an internal control. c Sequence alignment of the highly conserved AlkB domain in FvALKBH10B, Arabidopsis ALKBH10B (AtALKBH10B), and mouse ALKBH5 (MmALKBH5B). Highlighted by blue and pink rectangles are Fe (II) binding sites and alpha-ketoglutaramate (α-KG) binding sites, respectively. d Recombinant FvALKBH10B protein demethylates the m6A modification in m6A-containing ssRNA probe in vitro. LC-MS/MS chromatograms of digested m6A-containing ssRNA are shown. e FvALKBH10B demethylates m6A modification in mRNA in vivo. The mRNAs isolated from Nicotiana benthamiana leaves transiently expressing the FvALKBH10B-HA protein or the empty plasmid control (HA) were used for measurement of m6A contents by LC-MS/MS. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3 biological replicates). Asterisks indicate significant differences (unpaired two-sided t-test; **P < 0.01). Immunoblot analysis was performed to detect the expression of FvALKBH10B-HA fusion protein. f Subcellular location showing that FvALKBH10B locates in both cytoplasm and nucleus. N. benthamiana protoplasts co-expressing eGFP and mCherry were used as the negative control. The histone H2B serves as a nucleus marker. Protoplasts of the N. benthamiana leaves transiently co-expressing eGFP-FvALKBH10B and H2B-mCherry were isolated and observed under a Zeiss confocal microscopy. The experiment was repeated independently three times with similar results, and one representative result is shown. Scale bar = 10 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Sequence alignment confirmed the existence of AlkB domain in FvALKBH10B as that in Arabidopsis ALKBH10B and mouse ALKBH5, the reported m6A demethylases14,21 (Fig. 1c). To determine if FvALKBH10B possesses demethylation activity, the MBP-tagged FvALKBH10B (MBP-FvALKBH10B) recombinant protein was incubated with a synthetic 16 nucleotide-long m6A-modified ssRNA. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis of the nucleosides digested from the reaction products revealed that more than 50% of the methyls in m6A were effectively removed by the recombinant FvALKBH10B (Supplementary Fig. 3a) compared to the control, concomitant with a corresponding increase in adenosine (A) (Fig. 1d), indicating that FvALKBH10B has m6A demethylation activity in vitro. To explore the oxidative demethylation activity of FvALKBH10B in vivo, HA-tagged FvALKBH10B (FvALKBH10B-HA) was transiently expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves, and the full-length mRNAs were then isolated for LC-MS/MS detection of overall m6A levels. The expression of FvALKBH10B resulted in a decrease in total m6A levels (Fig. 1e), confirming the demethylation activity of FvALKBH10B in vivo.

Subcellular localization analysis showed that an enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP)-tagged FvALKBH10B (eGFP-FvALKBH10B) driven by its native promoter produced fluorescent signals in the cytoplasmic structure (Fig. 1f). Moreover, the fluorescent signals of eGFP-FvALKBH10B co-localized with those of a mCherry-tagged histone H2B (H2B-mCherry), a nucleus marker36. These results suggest that FvALKBH10B was localized in both cytoplasm and nucleus. Together, our data indicate that FvALKBH10B is an m6A demethylase that functions in both cytoplasm and nucleus to demethylate mRNA m6A modifications.

FvALKBH10B is induced by ABA and transcriptionally activated by FvABF3

During the development and ripening of strawberry fruit, the concentration of ABA gradually increases37. This, together with the observation that FvALKBH10B increases markedly in the ripening process (Fig. 1b), promoted us to hypothesize that FvALKBH10B expression may be regulated by ABA. As expected, FvALKBH10B was strongly induced by exogenous application of ABA (Fig. 2a), concomitant with a substantial decrease in overall m6A levels (Fig. 2b). To explore how FvALKBH10B expression is regulated by ABA, its promoter sequence was submitted to PlantRegMap (http://plantregmap.gao-lab.org/regulation_prediction.php), which predicted ABF3, a master transcription factor in ABA signaling, as a potential upstream regulator. Strawberry ABF3 (FvABF3) appeared to be ABA-responsive (Fig. 2c). There exist 4 ABRE cis-elements, the ABF3 binding motifs, in the promoter region (2.0 kb upstream of the start codon) of FvALKBH10B. Yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) indicated that FvABF3 binds to the promoter of FvALKBH10B (Fig. 2d). Moreover, the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) showed a distinct band shift was observed when the purified recombinant FvABF3 protein (Supplementary Fig. 3b) was mixed with the biotin-labeled probe (30-mer oligo-nucleotide) containing the ABRE element (Fig. 2e). The shifted band was out-competed by the addition of excess unlabeled probe with intact ABRE element (cold probe), but not by a probe with mutated ABRE element (mutant cold probe) (Fig. 2e), confirming the binding of FvABF3 to the promoter of FvALKBH10B in vitro. Finally, to investigate whether FvABF3 directly binds to the promoter of FvALKBH10B in vivo, we performed a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay. For that purpose, an HA-tagged FvABF3 (FvABF3-HA) was overexpressed in diploid strawberry F. vesca, and the cross-linked DNA-protein complexes were captured by immunoprecipitation with anti-HA magnetic beads. Significant enrichment for the promoter region of FvALKBH10B containing the ABRE element was observed in FvABF3-bound chromatin (Fig. 2f), indicating that FvABF3 binds to FvALKBH10B promoter in vivo.

a The changes in gene expression of FvALKBH10B in response to ABA (50 μM) in strawberry fruits at large green stage as determined by RT-qPCR. ACTIN was used as an internal control. b LC-MS/MS assay revealing the decrease in total m6A levels after exogenous application of ABA in strawberry fruits at large green stage. c Expression pattern of FvABF3 in response to ABA in strawberry fruits at large green stage. In a–c, fruit samples were treated with ABA for indicated times before sampling. d Y1H assay showing the binding of FvABF3 to the promoter fragment of FvALKBH10B. The empty pGADT7 was used as the negative control. AbA Aureobasidin. e EMSA reveals that FvABF3 directly binds to the ABRE cis-acing elements in the FvALKBH10B promoter. The probe sequences are shown, with red letters representing the intact or mutated ABRE elements. For d, e, the experiment was repeated independently three times with similar results. f ChIP-qPCR assay shows the direct binding of FvABF3 to the promoter of FvALKBH10B. Pink boxes, ABRE elements; blue lines, regions used for ChIP-qPCR. Negative controls (ACTIN and TUBULIN) are included. g Transcriptional activity assay of FvABF3. The reporter plasmid contains the FvALKBH10B promoter fused with firefly luciferase (LUC), with renilla luciferase (REN) as an internal control. A representative image is shown. h, i Representative images of strawberry fruits silencing (h) or overexpressing (i) FvABF3. Fruits at large green stage were used for agroinfiltration and considered as days 0. EV, empty vector. Scale bar, 0.5 cm. j, k Anthocyanin contents in fruits shown in h (j) and i (k). l, m The mRNA levels of FvABF3 and FvALKBH10B in fruits at days 2 shown in h (l) and i (m), as determined by RT-qPCR. For a–c, f, and j–m, values are means ± SEM (n = 3 biological replicates). For g, values are means ± SEM (n = 5 biological replicates). Asterisks indicate significant differences (unpaired two-sided t-test; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). NS no significant. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We next carried out a dual-luciferase reporter analysis in N. benthamiana leaves by co-expressing a reporter containing the FvALKBH10B promoter region fused with the firefly luciferase (LUC) reporter gene and an effector harboring the FvABF3 coding sequence driven by CaMV35S. As shown in Fig. 2g, FvABF3 activated the expression of FvALKBH10B, which was indicated by an increase in relative LUC to renilla luciferase (REN) ratio in N. benthamiana expressing FvABF3 compared to that expressing the empty effector (negative control). We then transiently silenced (via RNA interference; RNAi-FvABF3) and overexpressed (35S:FvABF3) FvABF3 in strawberry fruits and observed a delay in fruit ripening in FvABF3-RNAi fruits and an acceleration in 35S:FvABF3 fruits (Fig. 2h, i). Consistent with these results, anthocyanin contents were significantly reduced in RNAi-FvABF3 fruits and increased in 35S:FvABF3 fruits (Fig. 2j, k). Moreover, silencing of FvABF3 decreased the expression of FvALKBH10, while overexpression of FvABF3 exhibited an opposite effect (Fig. 2l, m). Together, these data suggest that ABA promotes FvALKBH10B transcription through FvABF3, which positively regulates fruit ripening and binds directly to the promoter of FvALKBH10B and transcriptionally activates its expression.

FvALKBH10B affects the normal ripening of strawberry fruit

To determine the physiological role of FvALKBH10B, we generated stable Fvalkbh10b knockout mutants in diploid strawberry, F. vesca variety Ruegen, using a CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing system. Two single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) containing different target sequences (T1 and T2) were designed to specifically target the exons of FvALKBH10B (Fig. 3a). We obtained three independent homozygous mutant lines (Fvalkbh10b-1, Fvalkbh10b-2, Fvalkbh10b-3) in the second generation, which were verified by sequencing genomic regions flanking the target sites. Line Fvalkbh10b-1 and Fvalkbh10b-2 carry 1-bp insertion, respectively, while line Fvalkbh10b-3 harbors 1-bp deletion (Fig. 3b). All mutants were predicted to cause premature termination of FvALKBH10B protein translation within the following 60-bp sequence of the editing sites, just before the AlkB domain. The potential off-target sites in the strawberry genome were predicted by CRISPR-P (version 2.0, http://crispr.hzau.edu.cn/cgi-bin/CRISPR2/CRISPR), and no editing events were observed in the 5 potential off-target sites (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b), indicating the specific mutation for FvALKBH10B.

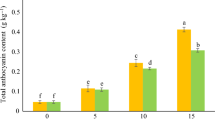

a Schematic diagram of sgRNAs with two target sequences (T1 and T2) designed to specifically target the exons of FvALKBH10B. Red letters, protospacer adjacent motif (PAM); red vertical line, target sequence location; red horizontal line, Alkb domain location. b Genotyping of mutations mediated by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in the Fvalkbh10b-1, Fvalkbh10b-2, Fvalkbh10b-3 mutant lines. Sequences of the isolated mutant alleles are aligned to the wild type (WT). The inserted/deleted nucleotides are colored with red to indicate the editing sites. Red arrowheads indicate the sites of frameshift in the translated mutant proteins. Red asterisks indicate protein translation termination site. c LC-MS/MS assay revealing the total m6A level in fruits of WT and Fvalkbh10b mutants at 25 days post anthesis (DPA). d, e Phenotypes of strawberry flowers (d) and fruits (e) from WT and Fvalkbh10b mutants. Scale bar, 0.5 cm. f–i Changes in anthocyanin contents (f) and sugar contents, including sucrose (g), glucose (h), and fructose (i) in the mutant lines at 27 and 33 DPA. j LC-MS/MS assay revealing the changes in total m6A level in fruits of overexpression lines (FvALKBH10B-OE) at 28 DPA. k Relative expression of FvALKBH10B in control and overexpression lines as determined by RT-qPCR. ACTIN was used as an internal control. l Phenotypes of fruit ripening in overexpression lines. EV empty vector. Scale bar, 0.5 cm. m Changes in anthocyanin contents in overexpression lines at 27 and 33 DPA. For c, f–k, and m, values are means ± SEM (n = 3 biological replicates). Data are analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.05). Different lowercase letters represent significant differences. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

FvALKBH10B mutation led to elevated m6A levels in total mRNA (Fig. 3c), confirming the in vivo m6A demethylation activity of FvALKBH10B. All three mutant lines (Fvalkbh10b-1, Fvalkbh10b-2, and Fvalkbh10b-3) displayed an obvious petal non-shedding phenotype, i.e. the fruits retained the petals throughout the whole ripening process (Fig. 3d). This may be related to the effect of FvALKBH10B on floral transition as previously reported in Arabidopsis21. Intriguingly, the mutant lines showed similar and obvious ripening-delayed phenotypes (with petals artificially removed; Fig. 3e). A visible color change was observed at 27 days post anthesis (DPA) in fruits of the wild type, while the fruits in the Fvalkbh10b lines remained green at this stage (Fig. 3e). At 33 DPA, when the fruits in the wild type turned to a fully red color, the fruits from the mutants were only just starting to change color. Consistent with the color phenotype, the anthocyanin content was significantly decreased in fruits of the Fvalkbh10b lines (Fig. 3f). Moreover, the fruits in the mutants exhibited significantly lower levels for the major sugars, including sucrose, glucose, and fructose compared to the wild type (Fig. 3g–i). Notably, exogenous application of ABA could not rescue the delayed ripening phenotype of the Fvalkbh10b mutants, indicating that FvALKBH10B mediates the effect of ABA to regulating strawberry fruit ripening (Supplementary Fig. 5).

To confirm the positive role of FvALKBH10B in the regulation of fruit ripening, we also generated stable FvALKBH10B overexpression lines (FvALKBH10B-OE-L1 and FvALKBH10B-OE-L2) in diploid strawberry. These overexpression lines, which exhibited declined m6A levels in total mRNA (Fig. 3j), showed phenotypes opposite to those seen in the Fvalkbh10b mutants (Fig. 3k, l). Compared to the control, the anthocyanin content was significantly increased in FvALKBH10B-OE fruits (Fig. 3m). Together, our data support the notion that FvALKBH10B is indispensable for the normal ripening of strawberry fruit.

FvALKBH10B mutation leads to global m6A hypermethylation

To decipher the mechanisms by which FvALKBH10B regulates fruit ripening, we performed m6A sequencing (m6A-seq) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) using mRNA from fruits of wild-type and Fvalkbh10b mutant at 27 DPA. The libraries for sequencing were prepared with three replicates, in which the mRNA samples were independently prepared. Pearson correlation coefficient analysis between biological replicates confirmed the reliable repeatability of our m6A-seq data (Supplementary Fig. 6a). A total of 30−32 million clean reads were produced for each library, of which 93−97% were mapped to the F. vesca Whole Genome v4.0.a2 (Supplementary Data 2). We identified 22012 m6A peaks in common between the samples (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Data 3, 4), with 1954 peaks specific to the wild type (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Data 5) and 2856 peaks specific to the Fvalkbh10b mutant (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Data 6). The m6A cumulative curve indicated that the overall m6A level in Fvalkbh10b line was higher than that in wild type (Supplementary Fig. 6b), which was in accordance with the results observed in LC-MS/MS showing that mutation of FvALKBH10B led to elevated m6A levels (Fig. 3c).

a Venn diagrams showing the number of common and specific m6A peaks in the wild type (WT) and Fvalkbh10b mutant identified by m6A-seq. b Percentage of the m6A-modified transcripts with various m6A peak numbers. c Metagenomic profiles of m6A peak distribution along transcripts in WT and Fvalkbh10b. UTR untranslated region, CDS coding sequence. d–g The percentage (d, e) and relative enrichment (f, g) of m6A peaks in five non-overlapping transcript segments. h Consensus motifs identified within m6A-containing peak regions by HOMER. i Volcano plot showing hypermethylated (blue) and hypomethylates (yellow) m6A peaks in fruits of Fvalkbh10b mutant across three biological replicates (fold change ≥ 1.5 and P value < 0.05; two-sided Wald test). The gray plot depicts the peaks with no significant difference. j Volcano plots revealing the upregulated (blue) and downregulated (yellow) genes in fruits of Fvalkbh10b mutant compared to WT by RNA-seq (fold change ≥ 2.0 and P value < 0.05; two-sided Exact test). k Venn diagram showing the overlap between differentially expressed genes and m6A-hypermethylated genes. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Most of the m6A-containing transcripts (53.35% in wild type and 54.34% in Fvalkbh10b line) possess one m6A peak, while some transcripts possess two or more m6A peaks in wild type and the mutant (Fig. 4b). The metagenomic profiles of m6A peaks in wild type and Fvalkbh10b line indicated that the m6A modifications were highly enriched around both the start and stop codons and within the 3’ UTR (Fig. 4c). We divided the transcripts into 5 non-overlapping segments and found the m6A peaks were most abundant around stop codon (39.71% in wild type and 40.27% in Fvalkbh10b), followed by 3’ UTR (23.13% in wild type and 23.14% in Fvalkbh10b), coding sequence (CDS) (17.67% in wild type and 17.68% in Fvalkbh10b), start codon (15.11% in wild type and 14.43% in Fvalkbh10b), and least abundant in 5’ UTR (4.38% in wild type and 4.48% in Fvalkbh10b) (Fig. 4d, e). After segment normalization by the relative fraction that each segment occupied in the transcriptome, the m6A modifications in wild type and Fvalkbh10b line were exclusively enriched around the start and stop codons and within the 3’ UTR (Fig. 4f, g). We next examined the sequence motifs within the m6A peaks and identified two typical m6A consensus sequences (Fig. 4h), the RRACH (R = A/G; H = A/C/U) found in plants10 and animals38 and the URUAY (Y = C/U) specific for plants39.

Subsequently, we explored the differential m6A peaks and identified 2072 hypermethylated peaks and 1298 hypomethylated peaks, covering 1859 and 1200 genes, respectively, in the Fvalkbh10b mutant (Fig. 4i; Supplementary Data 7). The m6A modification has been shown to affect mRNA abundance34,40,41. Our parallel RNA-seq analysis identified 3563 upregulated (Log2(fold-change [FC]) ≥ 1; P value < 0.05) and 1365 downregulated (Log2(FC) ≤ − 1; P value < 0.05) genes in the Fvalkbh10b mutant relative to the wild type (Fig. 4j, Supplementary Data 8). To assess if the changes in m6A modification caused by FvALKBH10B disruption influences mRNA abundance, we compared the differentially expressed genes with the 1859 m6A hypermethylated genes, which led to the identification of 588 overlapping genes (Fig. 4k; Supplementary Data 9). Among them, 324 genes (55.1%) were expressed at higher levels and 264 genes (44.9%) were expressed at lower levels in the Fvalkbh10b mutant (Fig. 4k). Together, our data suggest that loss of FvALKBH10B function results in global m6A hypermethylation, which in turn leads to the changes in mRNA levels.

FvALKBH10 affects mRNA abundance of ripening-related genes

Among the m6A-hypermethylated genes with differential expression in the Fvalkbh10b mutant, some are relevant to fruit ripening, such as SEPALLATA3 (FvSEP3)42, ABA-RESPONSIVE ELEMENT-BINDING PROTEIN 1 (FvAREB1)43, and DOMAINS REARRANGED METHYLASE3.1 (FvDRM3.1)44 (Supplementary Data 9). FvSEP3 encodes a MADS-box transcription factor positively regulates strawberry fruit development and ripening42, while FvAREB1 encodes a bZIP transcription factor in the ABA signaling pathway43. FvDRM3.1 encodes a key enzyme in the RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway that is negatively correlated with strawberry fruit ripening44. FvSEP3 and FvAREB1 exhibited m6A hypermethylation in the 3’UTR (Fig. 5a), whereas FvDRM3.1, which appeared to be Fvalkbh10b-specific (Supplementary Data 6), displayed m6A peaks in the CDS region (Fig. 5a). The differential m6A modification in these 3 genes was confirmed by m6A-IP-qPCR analysis (Fig. 5b). The transcript level of FvSEP3 declined significantly in the Fvalkbh10b mutant as revealed by RNA-seq (Fig. 5c) and RT-qPCR (Fig. 5d). Although the transcript level of FvAREB1 exhibited no significant change in the Fvalkbh10b mutant in the RNA-seq analysis (Fig. 5c), it displayed a significant decrease in the Fvalkbh10b line in RT-qPCR (Fig. 5d). By contrast, the transcript level of FvDRM3.1 showed a significant increase in the Fvalkbh10b mutant as revealed by RNA-seq (Fig. 5c) and RT-qPCR (Fig. 5d). Considering the m6A hypermethylation of FvSEP3 and FvAREB1 in the 3’UTR and that of DRM3.1 in the CDS region, it appears that, consistent with our previous observation33, m6A deposition in the 3’UTR decreases mRNA levels, while m6A in the CDS exhibits the opposite effect. Notably, the m6A levels or expression of several ethylene-related genes, including FvACS1, FvACS4, and FvCTR1, showed no significant changes in the Fvalkbh10b mutant, suggesting that FvALKBH10B-mediated fruit ripening of strawberry is not regulated by ethylene-dependent process (Supplementary Fig. 7).

a Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) tracks showing the distribution of m6A reads in transcripts of FvSEP3, FvAREB1, and FvDRM3.1. The red dot line rectangles indicate the position of m6A peaks with significantly increased m6A enrichment (P value < 0.05; two-sided Wald test) in fruits of Fvalkbh10b mutant compared to wild type (WT). b Validations of the m6A enrichment by m6A-immunoprecipitation (IP)-qPCR. c, d Transcript levels of the indicated genes determined by RNA-seq (c) and RT-qPCR (d). FPKM, fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments. ACTIN was used as an internal control in RT-qPCR analysis. e Transcription inhibition assay for the indicated genes. The mRNAs were isolated from WT and Fvalkbh10b mutant treated with actinomycin D, and subjected to RT-qPCR analysis. f Translation efficiency assay for the indicated genes. Translation efficiency was expressed as the abundance ratio of mRNA in the polysomal RNA versus the total RNA. For b–f, data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 3 biological replicates). For b–d, asterisks indicate significant differences (unpaired two-sided t-test; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). NS no significant. For f, data are analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.05). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To determine how m6A modification affects mRNA abundance, we performed transcription inhibition assay by using actinomycin D, the transcription inhibiter. Compared to the wild type, the degradation rate of FvSEP3 and FvAREB1 was dramatically increased, while the degradation rate of FvDRM3.1 was decreased in the Fvalkbh10b mutant after actinomycin D treatment (Fig. 5e). These data suggest that FvALKBH10-mediated m6A demethylation affects mRNA abundance of ripening-related genes, probably due to the effect of m6A modification on mRNA stability. We also examined the translation efficiency of FvSEP3, FvAREB1, and FvDRM3.1, which was determined by calculating the abundance ratio of mRNA in the polysomal RNA versus the total RNA33. Notably, FvALKBH10B mutation significantly enhanced the translation efficiency of FvDRM3.1 mRNA, but showed no effects on that of FvSEP3 or FvAREB1 (Fig. 5f), demonstrating that FvALKBH10B-mediated m6A demethylation modulates translation of FvDRM3.1, but not that of FvSEP3 or FvAREB1. Collectively, our data suggest that FvALKBH10B may regulate strawberry fruit ripening by targeting ripening-related genes, leading to the changes in mRNA stability or translation efficiency of these genes.

FvALKBH10B-mediated m6A demethylation regulates FvSEP3 function by stabilizing its mRNA

FvSEP3 acts as an important positive regulator for strawberry fruit ripening, as mutation of FvSEP3 resulted in a dramatic delay in ripening42. The expression of FvSEP3 increased significantly during fruit ripening (Fig. 6a), similar to that of FvALKBH10B, suggesting that the ripening-inhibited phenotype observed in the Fvalkbh10b mutant may be partially attributed to the changes in FvSEP3 abundance caused by FvALKBH10B disruption. Silencing of FvSEP3 in the Fvalkbh10b mutant background by RNAi showed an obviously additive effect on ripening inhibition (Fig. 6b–d), while overexpression of FvSEP3 reversed the delayed ripening phenotype of the Fvalkbh10b mutant (Fig. 6e–g), confirming that FvSEP3 may regulate fruit ripening downstream of FvALKBH10B. We next explored whether FvALKBH10B directly binds to the transcripts of FvSEP3 using RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP). The FvALKBH10B-bound mRNAs were immunoprecipitated from fruits of the Fvalkbh10b mutant transiently expressing the HA-tagged FvALKBH10B protein (FvALKBH10B-HA), and this led to an enrichment of FvSEP3 (Fig. 6h), suggesting the direct binding of FvALKBH10B to the FvSEP3 transcript.

a Gene expression of FvSEP3 as determined by RT-qPCR. RT root, ST stem, LE leaf, FL flowers, SG small green, LG large green, WF white fruit, TF turning fruit, RF red fruit. ACTIN was used as an internal control. b Representative images of fruits silencing FvSEP3 in the Fvalkbh10b mutant background. Fruits at large green stage were used for agroinfiltration and considered as days 0. EV empty vector, WT wild type. Scale bar, 0.5 cm. c The mRNA levels of FvSEP3 in fruits shown in (b) as determined by RT-qPCR. d Anthocyanin contents in the fruits shown in b. e, Representative images of fruits overexpressing FvSEP3 in the Fvalkbh10b mutant background. Fruits at large green stage were used for agroinfiltration and considered as days 0. Scale bar, 0.5 cm. f The mRNA levels of FvSEP3 in fruits shown in (e), as determined by RT-qPCR. g Anthocyanin contents in the fruits shown in (e). h RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay showing that FvALKBH10B directly binds FvSEP3 transcript. The FvALKBH10B-HA fusion protein was transiently expressed in fruits of Fvalkbh10b mutant, and then the FvALKBH10B-bound mRNAs were immunoprecipitated and submitted to RT-qPCR assay. For a, c, d, and f–h, values are means ± SEM (n = 3 biological replicates). For c, d, f, and g, data are analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.05). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences. For h, asterisks indicate significant differences (unpaired two-sided t-test; ***P < 0.001). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In the m6A-seq analysis, we identified one m6A peak within 3’UTR of the FvSEP3 transcript (Fig. 5a). There are 13 m6A sequence motifs in this m6A-containing peak region (roughly 200 nt wide), including 5 RRACH consensus sequences and 8 URUAH sequences (Supplementary Fig. 8a). We applied SELECT assay, a method for detection of single m6A locus45, to determine the specific m6A sites in FvSEP3 transcript. This led to the identification of 4 m6A sites, i.e. m6A1016 within the RRACH motif and m6A896, m6A912, and m6A1012 within the URUAH motif, which were mediated by FvALKBH10B (Supplementary Fig. 8b, c). To examine if these specific m6A sites affects FvSEP3 mRNA stability, the native cDNA fragment of FvSEP3 (FvSEP3-WT) or the mutated form (FvSEP3-Mu) in which each of these 4 m6A sites was individually mutated from A to guanosine (G) was transformed into fruits of F. vesca, and then the degradation rate of mRNAs was monitored. As shown in Fig. 7a, the mRNA of native FvSEP3 (FvSEP3-WT) degraded quickly in the presence of actinomycin D. Mutation of m6A896 (FvSEP3-Mu896), but not m6A912 (FvSEP3-Mu912), m6A1012 (FvSEP3-Mu1012), or m6A1016 (FvSEP3-Mu1016), led to an increase in mRNA stability of FvSEP3 (Fig. 7a), indicating that m6A896 serves as the key site essential for FvSEP3 stability. When FvALKBH10B was co-expressed with FvSEP3-WT in F. vesca, the degradation rate of FvSEP3-WT mRNA declined (Fig. 7b), concomitant with a significant decrease in m6A enrichment of FvSEP3 (Fig. 7c). Importantly, co-expression of FvALKBH10B with FvSEP3-Mu896 further decreased the degradation rate of FvSEP3 mRNA (Fig. 7b). These results demonstrated that FvALKBH10B-mediated m6A demethylation at m6A896 stabilizes FvSEP3 mRNA.

a Determination of the FvSEP3 mRNA stability. The native (FvSEP3-WT) or mutated FvSEP3 (FvSEP3-Mu) cDNA fragment was transiently expressed in fruits of F. vesca. After actinomycin D treatment for 1 or 2 h, the total RNAs were extracted and subjected to RT-qPCR analysis. ACTIN gene severed as an internal control. b Influence of FvALKBH10B on FvSEP3 mRNA stability. The native (FvSEP3-WT) or mutated FvSEP3 (FvSEP3-Mu896) cDNA fragment was co-expressed with FvALKBH10B-HA or empty vector control (HA) in fruits of F. vesca. c m6A-IP-qPCR assay showing the m6A enrichment in FvSEP3 transcript shown in b. Immunoblot analysis shows the FvALKBH10B-HA protein expression. d Representative images showing the fruits of the wild type transiently expressing the native (FvSEP3-WT) or mutated FvSEP3 (FvSEP3-Mu896) cDNA fragment. Fruits at large green stage were used for agroinfiltration and considered as days 0. EV, empty vector. Scale bar, 0.5 cm. e The mRNA levels of FvSEP3 in fruits shown in (d), as determined by RT-qPCR. f Anthocyanin contents in fruits shown in (d). g Representative images showing the fruits of the Fvsep3 mutant transiently expressing the native (FvSEP3-WT) or mutated FvSEP3 (FvSEP3-Mu896) cDNA fragment. Fruits at 30 days post anthesis were used for agroinfiltration and considered as days 0. Scale bar, 0.5 cm. h The mRNA levels of FvSEP3 in fruits shown in (g), as determined by RT-qPCR. i Anthocyanin contents in fruits shown in (g). For a–c, e, f, h, and i, values are means ± SEM (n = 3 biological replicates). For c, e, f, h, and i, data are analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD test (P < 0.05). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To explore whether m6A modification affects physiological function of FvSEP3 in vivo, we transiently expressed various constructs in fruits of the wild-type F. vesca: native FvSEP3 (FvSEP3-WT) or its mutated form FvSEP3-Mu896, in which the key m6A site (m6A896) was mutated to G. As shown in Fig. 7d–f, overexpression of FvSEP3-WT accelerated fruit ripening, confirming the function of FvSEP3 in controlling ripening. Compared to the fruits overexpressing FvSEP3-WT, fruits overexpressing FvSEP3-Mu896 ripened more quickly (Fig. 7d), accompanied by higher levels of anthocyanin (Fig. 7f). These results indicate that m6A modification in FvSEP3 regulates its function.

To further confirm that m6A methylation regulates the function of FvSEP3 in the control of strawberry fruit ripening, either native FvSEP3 (FvSEP3-WT) or the mutated form (FvSEP3-Mu896) was transiently expressed in fruits of the Fvsep3 mutant (kindly provided by Dr. Chunying Kang from Huazhong Agricultural University). The Fvsep3 mutant harbors a point mutation in FvSEP3 causing a single amino acid G to E conversion in the conserved MADS domain, which leads to a significant delay in fruit ripening42. We found that native FvSEP3 rescued the delayed ripening phenotype of the Fvsep3 mutant (Fig. 7g–i). By contrast, fruits of the Fvsep3 mutant transiently expressing FvSEP3-Mu896 ripened faster than those expressing native FvSEP3 (Fig. 7g–i). Together, these findings suggest that FvALKBH10B-mediated m6A modification plays a critical role in the regulation of FvSEP3 function in strawberry.

FvSEP3 directly targets numerous genes relevant to fruit ripening

Although FvSEP3 plays a critical role in the control of strawberry fruit ripening42, the mechanisms underlying FvSEP3-mediated transcriptional regulation remain unclear. We performed DNA affinity purification sequencing (DAP-seq)46 to unravel FvSEP3 binding sites on a genome-wide scale. For that purpose, recombinant FvSEP3 fused to HaloTag sequence was used to purify sheared genomic DNA from fruits of F. vesca. Two independent biological replicates for DAP-seq and DNA “input” libraries were prepared for high-throughput sequencing. We consistently obtained a total of 13,283 enriched peaks, corresponding to 10,674 genes, in both biological replicates (Fig. 8a; Supplementary Fig. 9a; Supplementary Data 10–13). The binding sites were highly enriched around transcriptional start sites (TSS) (Fig. 8b; Supplementary Fig. 9b). A detailed analysis of the binding profiles indicated that 20.8% and 8.5% of the binding sites were located within promoter regions (up to 2.0 kb upstream from a TSS) and 5’UTRs (Fig. 8c), respectively, corresponding to a total of 3706 genes (Supplementary Data 14). The binding sites of FvSEP3 were distributed evenly across the length of all 7 F. vesca chromosomes (Supplementary Fig. 9c), suggesting that FvSEP3 has no preference for a specific chromosome.

a DAP-seq using two biological replicates (rep) identifies 13,283 high-confidence FvSEP3 binding peaks in the whole genome. b Metaplot of FvSEP3 binding sites. The FvSEP3 binding sites are centered on the TSS. TSS, transcription start site; TES transcription end site. c Distribution of FvSEP3 binding peaks across genomic features. d DNA logo of enriched DNA binding sites for FvSEP3. The P-value is provided. e Gene ontology (GO) enrichment for FvSEP3-bound genes determined by DAP-seq (One-sided hypergeometric test). Bigger dots represent more genes. f FvSEP3 binding peaks (Repeat 1 and 2) and negative control (mock) over the FvGH3.1, FvGA3ox1, FvNCED1, and FvCHS1 loci as determined by DAP-seq. g EMSA reveals that FvSEP3 directly binds to the sequence motifs in the FvGH3.1, FvGA3ox1, FvNCED1, and FvCHS1 promoters. The probe sequences are shown, with red letters representing the intact or mutated CArG-box elements. Recombinant purified FvSEP3 was incubated with biotin-labeled probe or unlabeled probe with intact (cold probe) or mutated (mutant cold probe) CArG-box elements. The experiment was repeated independently three times with similar results. h ChIP-qPCR assay shows the direct binding of FvSEP3 to the promoter of indicated genes. The promoter structures of the target genes are shown (left panel). Pink boxes, CArG-box elements; Green lines, regions used for ChIP-qPCR. Values are the percentage of DNA fragments that coimmunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies in fruits overexpressing FvSEP3-HA or HA control relative to the input DNAs (right panel). Negative controls (ACTIN and TUBULIN) are included. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3 biological replicates). Asterisks indicate significant differences (unpaired two-sided t-test; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). NS no significant. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

A de novo motif prediction based on the FvSEP3-bound regions in the DAP-seq data showed the most enriched motif was represented by CCAWWWWAAG (W = A/T) (Fig. 8d), which is derived from a previously reported MADS-box recognition motif CArG-box47. Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the genes that contained FvSEP3 binding sites in promoter regions revealed a significant overrepresentation (P < 0.05; hypergeometric test) of catagories including “hormone-mediated signaling pathway”, “fatty acid biosynthetic process”, and “DNA binding and transcription regulation” (Fig. 8e), suggesting that FvSEP3 may directly control multiple biological pathways relevant to fruit ripening.

Subsequently, we compared the 10,671 FvSEP3 binding genes identified in our DAP-seq with the differentially expressed genes that have been previously revealed in the Fvsep3 mutant42. A total of 1177 genes were identified in common, suggesting they are direct targets of FvSEP3 (Supplementary Data 15). Among them, 624 genes (53.0%) were considered as targets positively regulated by FvSEP3, as they were downregulated in the Fvsep3 mutants, while 553 genes (47.0%) represented targets negatively regulated by FvSEP3, since they were upregulated in the Fvsep3 lines.

Fruit development and ripening in strawberry are controlled by multiple phytohormones, of which auxin and gibberellic acid (GA) promote fruit development in the early stage37, while ABA plays a central role in fruit ripening4,5. Interestingly, we identified multiple key genes in the biosynthetic pathway of auxin, GA, and ABA as direct targets of FvSEP3 (Supplementary Data 15), consistent with the role of FvSEP3 in the control of fruit development and ripening. We next selected 4 genes, i.e. GH3.1, GA3ox1, NCED1, and CHS1, which displayed FvSEP3 binding peaks in their promoter regions in the DAP-seq analysis (Fig. 8f), to validate their direct regulation by FvSEP3. GH3.1 (encoding IAA-amido synthetase) and GA3ox1 (encoding GA3-oxidase) participate in biosynthesis of auxin and GA48,49, respectively, while NCED1 (encoding 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase) controls ABA biosynthesis6. FvCHS1 encodes chalcone synthase, a key enzyme responsible for anthocyanin biosynthesis50.

To verify that FvSEP3 interacts with the promoter fragments of the selected genes, we performed an EMSA with purified recombinant FvSEP3 protein (Supplementary Fig. 3c). We observed a band shift for each promoter fragment when purified FvSEP3 protein was co-incubated with the biotin-labeled DNA probe (30-mer oligo-nucleotide) containing the CArG-box element (Fig. 8g), suggesting that FvSEP3 binds to the biotin-labeled promoter fragments. The shifted band was effectively competed by the addition of excess unlabeled DNA probe with intact CArG-box element (cold probe), but not by a probe with mutated CArG-box element (mutant cold probe) (Fig. 8g). These results indicated that FvSEP3 binds specifically to the promoters of FvGH3.1, FvGA3ox1, FvNCED1, and FvCHS1 in vitro. Furthermore, we performed a ChIP assay to determine whether FvSEP3 directly binds to the promoters of the selected genes in vivo. The cross-linked DNA-protein complexes were enriched from fruits of F. vesca overexpressing an HA-tagged FvSEP3 (FvSEP3-HA). Specific enrichment for the promoter regions of FvGH3.1, FvGA3ox1, FvNCED1, and FvCHS1 were observed in FvSEP3-bound chromatin (Fig. 8h), indicating that FvSEP3 binds to the promoter of these genes in vivo. Taken together, these data suggest that FvSEP3 regulates fruit development and ripening by directly targeting genes involved in biosynthesis of phytohormones and anthocyanins.

Based on our results presented in this study, we propose a model for strawberry fruit ripening governed by the FvABF3-FvALKBH10B-FvSEP3 regulatory cascade (Fig. 9). During the ripening of strawberry fruit, the accumulated plant hormone ABA activates the downstream transcription factor FvABF3, which directly binds to the ABRE cis-element in the promoter of the m6A demethylase gene FvALKBH10B and promotes its expression. The induced FvALKBH10B stabilizes mRNAs of numerous ripening-related genes, including FvSEP3, by mediating their m6A demethylation. In turn, FvSEP3 regulates fruit ripening by directly targeting ripening-related genes.

ABA activates the transcription of FvABF3, which in turn targets FvALKBH10B through the ABRE cis-element in the promoter and promote its expression. The enhanced FvALKBH10B stabilizes mRNAs of FvSEP3 via m6A-demethylation, which directly regulates ripening-related genes to control strawberry fruit ripening.

Discussion

The m6A RNA demethylase responsible for the removal of m6A has been characterized in various organisms. The fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) and ALKBH5 represent the m6A demethylases14,51 in mammals. FTO affects human obesity and energy homeostasis51, while ALKBH5 impacts mouse fertility14. In Arabidopsis, two m6A RNA demethylases have been currently characterized, of which AtALKBH10B regulates floral transition21, whereas AtALKBH9B affects the infectivity of RNA viruses52 and promotes mobilization of a heat-activated long terminal repeat retrotransposon30. Here, we identified FvALKBH10B, the homolog of Arabidopsis AtALKBH10B, as a strawberry m6A demethylase that oxidatively reverses m6A methylation in mRNA in vitro and in vivo. We demonstrated that FvALKBH10-mediated m6A demethylation promotes mRNA stability of FvSEP3 and FvAREB1, but decreases mRNA stability of FvDRM3.1. The contrasting effect may be caused by different m6A-binding proteins that recognize the specific sequence contexts around m6A marks. We speculate that, similar to YTHDF2 in mammals40, certain m6A-binding proteins recognizing FvSEP3 and FvAREB1 interact with components in processing bodies (P-bodies), thereby promoting mRNA decay. On the contrary, another type of m6A-binding proteins, resembling IGF2BPs in mammals17 and ECT2 in Arabidopsis41, recognize FvDRM3.1, leading to the delay in mRNA degradation, probably by disrupting the process of RNA decay in P-bodies. The detailed mechanisms deserve further investigation in the future.

We have speculated that FvALKBH10B may negatively regulate strawberry fruit ripening, since our previous work has shown that MTA, the m6A methyltransferase, function as a positive ripening regulator in strawberry. Contrary to expectations, however, we observed that the Fvalkbh10b mutant lines exhibit a delay in fruit ripening, suggesting that FvALKBH10B plays a positive role in regulating fruit ripening. Consistent with this observation, we found that FvALKBH10B-mediates m6A demethylation stabilizes mRNAs of ripening-related genes. We propose that the m6A levels for specific ripening-related genes should be maintained at appropriate extent in strawberry to ensure fruit ripening. Disruption of MTA or FvALKBH10B may disturb the homeostasis of m6A methylation of these genes and decrease their mRNA abundance, leading to the delay in fruit ripening. Notably, different mechanisms were utilized by MTA and FvALKBH10B to regulate fruit ripening in strawberry. MTA functions by facilitating mRNA stability of genes involved in ABA pathway including NCED533, while FvALKBH10B regulates fruit ripening mainly by stabilizing FvSEP3 transcript (Figs. 6, 7). This may partially explain why both MTA and FvALKBH10B positively regulate strawberry fruit ripening. In fact, a similar phenomenon has also been observed in humans where both m6A methyltransferase METTL353 and demethylase ALKBH554 promoted tumor growth and progression by modulating different genes. Notably, the expression of the homologous gene (FvH4_1g11920) of tomato SlALKBH2, which shows a sharp increase in the process of fruit ripening34, remained relatively constant during strawberry fruit ripening (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). It appears that this gene (FvH4_1g11920) does not contribute to the regulation of fruit ripening in strawberry. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that other ALKBHs besides FvALKBH10B contribute to the ripening regulation of strawberry fruit and further investigation is required to verify their involvement.

The activity or biological function of m6A methyltransferases and demethylases has been elucidated to be regulated by protein post-translational modification (PTM), such as SUMOylation, phosphorylation, and lactylation55,56,57,58. In contrast to PTM, transcriptional regulation of m6A machineries is poorly understood. In the present study, we revealed that the m6A demethylase FvALKBH10B is regulated by ABA signaling in strawberry. ABA induces the expression of FvABF3 encoding a downstream master transcription factor in the ABA signaling pathway, which in turn directly targets FvALKBH10B and activates its expression. Exogenous application of ABA led to the decrease in m6A levels, further confirming the regulation of FvALKBH10-mediated m6A demethylation by ABA signaling. Besides being critical for plant growth, development, and stress responses, ABA serves as a dominant regulator of ripening and quality in non-climacteric fruits4. How ABA coordinates with other regulators such as epigenetic modifiers to regulate fruit ripening makes for an attractive research question. ABA signal transduction appears to be complicated and there exist two pathways, one of which is the “ABA-PYR/PYL-PP2C-SnRK2-ABF/AREB” core signaling network59. In this pathway, ABA signals are transmitted to downstream ABA-responsive genes through ABFs/AREBs, which belong to the basic-domain leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor60. There are 9 ABF/AREB homologs in the Arabidopsis genome61 and FvABF3 appears to be the homolog of Arabidopsis ABF3. We propose that ABA regulates fruit ripening partially by reprogramming of m6A epitranscriptome. Our study not only uncovers a previously unknown layer of regulation on m6A methylation, but also reveals a mechanism underlying ABA-mediated ripening regulation.

The m6A modification modulates multiple biological processes by affecting mRNA metabolism of key genes; for instance, m6A on transcripts of WUSCHEL (WUS) and SHOOTMERISTEMLESS (STM), the key shoot meristem regulator genes, inversely correlates with their mRNA stability, thus regulating shoot stem cell fate18. m6A also impacts mRNA stability of FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT), SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN LIKE 3 (SPL3), and SPL9, which encode the key flowering time regulators, thereby influencing floral transition21. Here, we showed that FvSEP3, a MADS-box gene critical for strawberry fruit development and ripening, is regulated by FvALKBH10B-mediated m6A demethylation. FvALKBH10B binds directly to the transcript of FvSEP3 and modulates its stability via m6A demethylation. As a homolog of the Arabidopsis SEP3, FvSEP3 belongs to the class E floral homeotic genes in the well-known ABCE model for flower development42. Other clades of the SEP genes, such as MADS-RIN in tomato, a SEP1-like gene, acts as a master regulator of tomato fruit ripening, which directly regulates the expression of key enzymes in the ethylene biosynthetic pathway47. In this study, we provide several lines of evidence that FvSEP3 directly modulates genes in the ABA and anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway, suggesting that FvSEP3 plays a direct role in the regulation of ABA biosynthesis and anthocyanin generation.

Considering that FvALKBH10B and its homologs from various non-climacteric fruits exhibit high similarity (Supplementary Fig. 10), we propose that the FvALKBH10B-mediated control of fruit ripening and the regulatory mechanism we describe here may exist in other non-climacteric fruits.

Methods

Plant materials and growth condition

Diploid strawberry F. vesca variety Ruegen was grown in a greenhouse under standard culture conditions or in a growth room under a 12-h-light/12-h-dark photoperiod with a light intensity of 200 − 300 µmol m−2 s−1 at 23 °C. Fruits were harvested at different development stages, including small green (SG, about 15 DPA), large green (LG, about 22 DPA), white fruit (WF, about 25 DPA), turning fruit (TF, about 27 DPA), and red fruits (RF, about 31 DPA). All fruit samples with achenes stripped were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use.

Strawberry ALKBHs identification and phylogenetic analysis

The amino acid sequences of Arabidopsis ALKBHs35 were used as queries to search against the F. vesca reference genome database (https://www.rosaceae.org/species/fragaria_vesca/genome_v4.0.a2) by the BLASTP program with default parameters. Multiple sequence alignment was performed with the ALKBH protein sequences of Arabidopsis35, mouse14, and strawberry using ClustalX (version 2.1, http://www.clustal.org/clustal2/) with multiple alignment mode. The resulting alignment file was loaded into MEGA6 software (https://www.megasoftware.net/dload_win_gui) to construct a neighbor-joining (NJ) phylogenetic tree.

RNA isolation and RT-qPCR

Total RNAs were isolated from strawberry fruits using the plant RNA extraction kit (Magen, China, R4165-02). The extracted RNAs was digested with DNase I (Takara, D2215) and then reversely transcribed into cDNA using HiScript® III RT SuperMix for qPCR kit (Vazyme, China, R323-01). qPCR was carried out on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA) with the following program: 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 30 s. The 2(−ΔΔCT) method was used for calculating the relative levels of gene expression62. Strawberry ACTIN (FvH4_6g22300) was applied to normalize the expression values. Three biological replicates were conducted and the primers are listed in Supplementary Data 16.

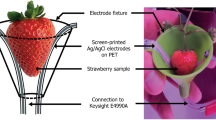

Quantitation of mRNA m6A by LC-MS/MS

Total RNAs were extracted from three biological replicates of strawberry fruits or N. benthamiana leaves. Each replicate consisted of a pool of ten fruits or six leaves collected from three plants. The mRNAs were isolated from total RNAs by the Dynabeads mRNA purification kit (Life Technologies, USA, 61006). Then, 200 ng of mRNAs from each sample were digested by 1 unit of nuclease P1 (Wako, Japan, 145-08221) at 37 °C for 6 h. The digested samples were separated using a UPLC (Waters, USA) equipped with an ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 column (2.1 × 100 mm; 1.7 μm internal diameter). The mobile phase containing buffer A (0.1% formic acid in ultrapure water) and buffer B (100% acetonitrile) were performed at a 0.38 mL min−1 flow rate with the following buffer gradient: 1%/99% (A/B) at 0 min, 10%/90% at 4 min, 90%/10% at 8 min, and 1%/99% at 10 min. After separation, the nucleosides were detected by a Triple Quad Xevo TQ-S mass spectrometer (Waters, USA) using MassLynx software (version 4.1) with the following parameters: positive ion mode, capillary voltage, 3 kV; cone voltage, 25 V for adenosine (A) and 20 V for N6-methyladenosine (m6A); desolvation temperature, 400 °C; source temperature, 150 °C; desolvation gas flow, 800 L h−1; collision gas flow, 0.14 mL min−1; collision energy, 20 V. The nucleosides were quantified on basis of the nucleoside-to-base ion mass transitions from m/z 268.0 to 136.0 (A) and m/z 282.0 to 150.1 (m6A)33. The pure commercial adenosine (A; TargetMol, China, T0853) and N6-methyladenosine (m6A; TargetMol, China, T6599) were employed to generate the standard curves, which were subsequently used to calculate the contents of A and m6A in each sample by fitting the peak areas to the standard curves. The m6A levels were presented in the form of m6A/A ratio. The mass spectrometry data are provided in the Supplementary Data 17.

Demethylation activity assay

For demethylation activity assay in vitro, the coding sequence of FvALKBH10B was PCR-amplified and inserted into the pETMALc-H-MBP vector (Merck KGaA) to generate MBP-tagged FvALKBH10B (MBP-FvALKBH10B). The resulting vector was transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3) competent cells, which were then cultured at 16 °C for 18 h with induction of 1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG). To obtain recombinant MBP-ALKBH10B proteins, the bacterial cells were collected and lysed by ultrasonication, and the crude lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was subjected to a gravity-flow column filled with Amylose Resin (NEB, E8021V), and then the bound recombinant MBP-ALKBH10B proteins were eluted. To measure the demethylation activity, 20 μg of MBP-FvALKBH10B or MBP protein was incubated with 1 nM m6A-containing ssRNA (AUUGUCAG[m6A]CAGCAGC) at 25 °C for 1 h21. The ssRNA was purified from the mixtures and submitted to LC-MS/MS analysis as described above. All primers used for constructing vector are listed in Supplementary Data 16.

For demethylation assay in vivo, the coding region of FvALKBH10B was PCR-amplified from strawberry cDNA and inserted into the pCAMBIA1302 vector. The resulting construct and the empty vector were transformed into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101, which was used for transient transformation of N. benthamiana leaves63. The demethylation activity was detected by analyzing the abundance of mRNA m6A in N. benthamiana leaves that transiently expressed FvALKBH10B or empty vector (control) using LC-MS/MS assay as describe above. The experiment was performed with 3 biological replicates. Primers are listed in Supplementary Data 16.

Western blot analysis

Proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and then electro-transferred onto an Immobilon-P PVDF membrane (Millipore, USA, IPVH00010). The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in 1× TBST buffer for 1 h at 25 °C, and then incubated with anti-HA (1:5000 dilution, MBL, M180), or anti-ACTIN (1:5000 dilution, Abmart, M001814) antibodies for 2 h. After washing three times by TBST buffer, the PVDF membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:5000 dilution, Abmart, M21002) secondary antibody for another 1 h. The immunoreactive bands were visualized by a chemiluminescence imaging system (5200 Multi, Tanon, China).

Subcellular localization

The promoter and coding sequence of FvALKBH10B were separately cloned from DNA or cDNA of F. vesca and insert into the pCAMBIA1302-eGFP vector to generate FvALKBH10Bpro:eGFP-FvALKBH10B construct. The resulting plasmid was introduced into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101, which was then injected into N. benthamiana leaves63. To obtain an accurate subcellular localization, the nucleus marker fused with mCherry (H2B-mCherry) was co-expressed with the FvALKBH10Bpro:eGFP-FvALKBH10B. After 42 h of infiltration at 22 °C, the mesophyll protoplasts were isolated64 and visualized under a Zeiss ultra-high resolution confocal microscope (Zeiss, German, LSM 980 with Elyra7) at the excitation/emission wavelength of 488/510 nm (eGFP) or 587/610 nm (mCherry). Primers are listed in Supplementary Data 16.

ABA treatment

For gene expression and m6A level analysis upon ABA treatment, the diploid strawberry fruits with achenes stripped were pre-cooled to 4 °C, sliced into 1 mm discs, and then incubated in equilibration buffer (50 mM MES, pH 5.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM EDTA, 5 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM Vc) with 200 mM mannitol for 30 min. The discs were then immersed in the equilibration buffer containing 50 μM ABA65. Discs incubated in the equilibration buffer with 200 mM mannitol served as control. After incubation for 0, 1, 2, 4, and 8 h, the discs were harvested and subjected to RT-qPCR and m6A level analysis. For the phenotype observation of strawberry fruits after ABA treatment, fruits from the Fvalkbh10b mutants and the wild-type control were treated with 100 μM ABA every 2 days after pollination until turning stage37.

Y1H analysis

Y1H assays were conducted according to the Matchmaker Gold Yeast One-Hybrid Library Screening System user manual (Clontech, USA). The coding sequence of FvABF3 were amplified from cDNA of strawberry and ligated into the pGADT7 vector (Clontech, USA), while specific DNA sequences from promoter region of FvALKBH10B were amplified from genomic DNA of strawberry and inserted into the pAbAi vector (Clontech, USA). The resulting pAbAi construct was digested with BstB1 or BbS1 and then transformed into the yeast (S. cerevisiae) strain Y1H Gold, which was then plated on synthetic defined (SD)/−Ura agar medium. Primers used in vector construction are listed in Supplementary Data 16.

EMSA

The full-length coding sequence of FvABF3 was inserted into the pGEX-6P-1-GST (GE Healthcare, USA) vector to generate the GST-FvABF3 recombinant protein, while that of FvSEP3 was cloned into the pETMALc-H-MBP (Merck KGaA, Germany) vector to generate MBP-FvSEP3. The resulting vectors were separately transformed into E. coli strain BL21 or BL21 (DE3) competent cells, which were used for purification of recombinant proteins34,66. The 5’ biotin-labeled double-stranded DNA probes were prepared by annealing 5’ biotin-labeled oligonucleotides to the corresponding complementary strands. The purified recombinant proteins were incubated with biotin-labeled or unlabeled DNA probes for 20 min at 25 °C, and then the samples were separated by a 6% (w/v) native polyacrylamide gel. All primers used for vector construction and the oligonucleotide probes are listed in Supplementary Data 16.

ChIP assay

The coding sequence of FvABF3 and FvSEP3 was individually amplified from cDNA of F. vesca and separately ligated into the pCAMBIA1302 plasmid to generate 35S:FvABF3-HA and 35S:FvSEP3-HA vectors. The resulting constructs were individually transformed into the A. tumefaciens strain GV3101, which was subsequently infiltrated into fruits of F. vesca at large green stage66. The empty vector served as the control. For ChIP assay, the infiltrated fruits with achenes stripped were sliced and fixed in 1% (w/v) formaldehyde and then subjected to nuclear isolation66. The enriched nuclei were lysed to obtain the chromatin with an average size of 250 − 1500 bp. A small part of the sonicated chromatin was retained as the input sample, and the remaining fragmented chromatin was incubated with HA-Nanoab-Magnetic beads (Lablead, China, HNM-25-1000) at 4 °C for 4 h. Subsequently, the beads were collected, and the DNA-protein complexes were detached from the beads by rotation at 65 °C for 1 h. The cross-linking was then reversed by incubation at 65 °C for 12 h with the supplementation of NaCl at a final concentration of 200 mM. The immunoprecipitated DNA was recovered using a TIANquick Mini Purification Kit (TIANGEN, China, DP214) and subjected to qPCR analysis as described above. Values are expressed as the percentage of DNA fragments that coimmunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies in fruits overexpressing FvABF3-HA or HA control relative to the input DNAs. The primers used for ChIP assay are provided in Supplementary Data 16.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

For dual-luciferase reporter assay, the coding sequence of FvABF3 was inserted into the pCAMBIA1302 plasmid as effector, and the FvALKBH10B promoter was cloned into the pGreen-II-0800-LUC dual reporter vector. Both effector and reporter were co-transformed into the N. benthamiana leaves by using Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. LUC and renilla (REN) luciferase activities were measured using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, USA. E1910). The relative luciferase activity was presented by the representative image and calculated as the ratio of LUC to REN67. Primers are listed in Supplementary Data 16.

CRISPR/Cas9 and overexpression vector construction and plant transformation

Two specific sgRNAs targeting the coding region of FvALKBH10B was designed using CRISPR-P2.0 (http://crispr.hzau.edu.cn/cgi-bin/CRISPR2/CRISPR). The sgRNA expression cassettes that driven by the AtU6-1 and AtU3b promoter, respectively, were amplified and inserted into the pYLCRISPR/Cas9Pubi-H binary vector using the Golden Gate method68. To construct the overexpression vector, the full-length coding sequence of FvALKBH10B was cloned from cDNA of the F. vesca fruits and insert into the pCAMBIA2300-eGFP vector.

The resultant constructs were separately transformed into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101. The A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation of diploid strawberry leaf discs was performed as previously reported69. To identify mutant genotypes, genomic DNA was extracted from homozygous mutant lines in the second generation. The genome regions containing the target sites and potential off-target sits were PCR-amplified and Sanger-sequenced. For transgenic overexpression plants, PCR genotyping was performed to amplify the flanking regions of the vector insertion site. All primers used for constructing vectors and screening the transgenic plants are listed in Supplementary Data 16.

Measurement of anthocyanin and soluble sugar

For anthocyanin measurement, the samples were subjected to high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis on an ACQUITY UPLC system (Waters, USA) equipped with a C18 column according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Cyanidin-3-glucoside (C3G) was employed as standard66.

For soluble sugar analysis, 0.5 g of fruit powder was added into 2.5 mL of double distilled water and incubated in a water bath for 30 min at 80 °C. The individual sugars (sucrose, glucose, and fructose) were identified and quantified using HPLC system (e2695, Waters, USA) equipped with a Waters 2414 RI detector. Each sample (10 μL) was injected onto a Sugar-ParkTM Ι column (6.5 × 300 mm, Waters, USA) with a column temperature of 90 °C at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. D-(+) glucose, D-(−) fructose, and sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were applied as standards for generating dose-response curves. There were three biological replicates and each sample contained five fruits from three plants.

m6A-seq and RNA-seq

For m6A-seq, total RNAs were extracted from fruits of wild type and the Fvalkbh10b mutant at 27 DPA. mRNAs were isolated from the qualified RNA samples and fragmented into ~100 nucleotide-long fragments. The cleaved mRNA fragments were incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with anti-m6A polyclonal antibody (Synaptic Systems, German, 202003). NEBNext Ultra RNA library preparation kit (NEB, USA, E7530) was used for constructing the libraries from immunoprecipitated mRNAs or pre-immunoprecipitated mRNAs (input)70. Sequencing was carried out on the Illumina NovaseqTM 6000 platform with a paired-end read length of 150 bp. The sequencing reads from the input samples were also used for RNA-seq analysis as previously reported21. The experiments were performed with three biological replicates, and each RNA sample was prepared from a mixture of at least 30 fruits to avoid individual differences among fruits.

For m6A-seq data analysis, the quality of clean reads was assessed using FastQC (version 0.12.0, https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Sequencing reads were mapped to the F. vesca whole genome v4.0.a2 using HISAT2 (version 2.2.1, http://www.ccb.jhu.edu/software/hisat/index.shtml). Peak calling and differential peak analysis were carried out by a R package exomePeak (version 2, https://bioconductor.org/packages/3.9/bioc/html/exomePeak.html) with a criterion of enrichment fold change ≥ 1.5 and P value < 0.05. ANNOVAR (an R package, https://annovar.openbioinformatics.org/en/latest/) was applied to annotate peaks using the strawberry genome annotation file. The de novo and known m6A motifs were identified by HOMER (version 4.1.0, http://homer.ucsd.edu/homer/motif/). The visualization of m6A peaks were performed using Integrated Genome Viewer (IGV, version 2.16.1, http://www.broadinstitute.org/igv/). For RNA-seq analysis, StringTie (version 2.1.2, https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/stringtie/) was employed for calculating fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped fragments (FPKM). An R package edgeR (https://bioconductor.org/) was used for differential gene expression analysis with a selection criterion of log2(FC) ≥ 1 or log2 (FC) ≤ − 1 and P value < 0.05.

m6A-IP-qPCR

For m6A-IP-qPCR analysis, mRNAs were fragmented into ~250-nucleotide-long fragments, which were incubated with anti-m6A polyclonal antibody (Synaptic Systems, German, 202003). The immunoprecipitated mRNAs and pre-immunoprecipitated mRNAs (input control) were reverse-transcribed into cDNA and submitted to qPCR analysis using the primers provided in Supplementary Data 16. Relative m6A level in specific region of a transcript was calculated using the 2(−ΔCT) method62. The value of the immunoprecipitated sample was normalized against that of the input control33. The experiment was performed with three biological replicates.

Transient transformation in strawberry fruit

To construct the RNAi vector, a ~ 300 bp fragment of FvABF3 or FvSEP3 coding sequence was cloned and ligated into the pCR8 plasmid, and then restructured into the pK7GWIWGD (II) plasmid. To construct the overexpression vectors, the coding sequence of FvABF3, FvSEP3 or the cDNA fragments of FvSEP3-WT and FvSEP3-Mu896 were separately ligated into the pCAMIA1302 plasmid under the 35S promoter or native promoter. The resulting constructs were separately transformed into Agrobacterium strain GV3101, which were subsequently injected into the fruits of the Fvalkbh10b mutant or wild type at the large green stage or the fruits of the Fvsep3 mutant (kindly provided by Dr. Chunying Kang from Huazhong Agricultural University) at 30 DPA. The empty vectors were used as the negative control. More than 10 fruits were injected for each construct. The infected fruits were remained on the plants to continue growth until the color changes71. The primers used for vector construction are listed in Supplementary Data 16.

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP)

RIP was performed following the method21 with minor modifications. In brief, the coding region of FvALKBH10B was amplified from cDNA of F. vesca and inserted into the pCAMBIA1302 vector to generate 35S:FvALKBH10B-HA construct. The resulting vector and the empty vector control were transformed into the fruits of the Fvalkbh10b mutant at large green stage via the A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation66. After three days of incubation at 23 °C, the fruits with achenes stripped were sliced and fixed in 1% (w/v) formaldehyde. The cross-linked fruits were ground in liquid nitrogen, and then homogenized in lysis buffer containing 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM KCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40 (v/v), 0.5 mM DTT, 1× cocktail protease inhibitor (Roche, 4693116001), and 300 units mL−1 of RNase Inhibitor (Beyotime, China, R0102-2KU). The mixture was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min after incubation at 4 °C for 1 h. Two hundred microliters of the supernatant were retained as the input control, and the remainder was immunoprecipitated by incubation with HA-Nanoab-Magnetic beads (Lablead, China, HNM-25-1000) at 4 °C for 3 h. The beads were washed five times with lysis buffer, followed by digestion with proteinase K (Takara, Japan, 9034) at 55 °C for 1 h. The immunoprecipitated RNAs and input RNAs were subsequently isolated by Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, USA, 10296028). Equal amounts of RNAs from IP sample and input were reverse-transcribed into cDNA and submitted to qPCR analysis as described above. The primers are provided in Supplementary Data 16.

SELECT analysis

For SELECT analysis, 20 ng of mRNAs were mixed with 40 nM Up-primer, 40 nM Down-primer, and 5 μM dNTP45. The mixture was annealed under a temperature gradient of 90 °C for 1 min, 80 °C for 1 min, 70 °C for 1 min, 60 °C for 1 min, 50 °C for 1 min, and 40 °C for 6 min. Subsequently, the mixture was supplemented with 0.01 unit Bst 2.0 DNA polymerase (NEB, USA, M0537S), 0.5 unit SplintR ligase (NEB, USA, M0375S), and 10 nmol ATP to a final volume of 20 μL, and then incubated at 40 °C for 20 min, followed by at 80 °C for 20 min. The mixture was diluted in DEPC-treated water and submitted to RT-qPCR analysis using SELECT-q-F primer and SELECT-q-R primer. Primers used in the SELECT analysis are listed in Supplementary Data 16.

Transcription inhibition and mRNA stability assay

For transcription inhibition assay, 20-d-old seedlings of the wild type or the mutant lines were treated with actinomycin D (Sigma-Aldrich, USA, A4262) at a final concentration of 20 μg mL−1. After 1 h of incubation, 20 seedlings were harvested and considered as time 0 controls, and the subsequent samples were collected every 1 h in triplicate21. The mRNA levels were examined by RT-qPCR as described above.

For mRNA stability assay, the intact cDNA fragment of FvSEP3 containing coding sequence and 3’ UTR was amplified from cDNA of F. vesca. The mutated form of the cloned sequence with mutations on the potential m6A sites were generated using the site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent, USA, 200518). The fragments were individually inserted into the pCAMBIA1302 vector, which was subsequently transformed into the fruits of F. vesca71 alone or with the FvALKBH10B-expressing vector (pCAMBIA1302-FvALKBH10B-HA). After 36 h of incubation, the infection parts of the F. vesca were infiltrated with 20 μg mL−1 actinomycin D. The fruit discs were taken after 30 min of incubation and considered as time 0 controls. The subsequent samples were taken every 1 h in triplicate33. The mRNA levels were then determined by RT-qPCR as described above. All primers are listed in Supplementary Data 16.

Translation efficiency assay

For translation efficiency assay, 5 g of strawberry fruits were ground into fine powder in liquid nitrogen. One gram of sample was applied for total RNA extraction, and the rest was used for polysome extraction33. The total RNAs, as well as the polysomal RNAs, were isolated and used for RT-qPCR analysis as described above. Translation efficiency was expressed as the abundance ratio of mRNA in the polysomal RNA versus the total RNA by the cycle threshold (CT) 2(−ΔΔCT) method62 using ACTIN (FvH4_6g22300) gene as an internal reference. The primers are listed in Supplementary Data 16.

DAP-seq and data analysis

For DAP-seq, a genomic DNA library of F. vesca was constructed by a NEBNext DNA Library Prep Master Mix Set Kit for Illumina (NEB, USA, E7645L). Recombinant FvSEP3 was prepared as a fusion protein with the HaloTag sequence using a TNT SP6 High-Yield Protein Expression System (Promega, USA, L3260). The recombinant FvSEP3-HaloTag protein was purified by Magne HaloTag Beads (Promega, USA, G7281). Then, the FvSEP3-HaloTag Beads mixtures or HaloTag beads were incubated at 4 °C for 2 h with the genomic DNA library. The DNA fragments were eluted from the FvSEP3-HaloTag beads, and then the DAP-seq library was generated using a KAPA Library Quantification Kit (KAPA, USA, KK4824), followed by high-throughput sequencing on a Nova S4 instrument with a paired-end read length of 150-bp (Illumina, USA).

For DAP-seq data analysis, clean reads were mapped to the F. vesca whole genome v4.0.a2 annotation using BWA-MEM (https://janis.readthedocs.io/en/latest/tools/bioinformatics/bwa/bwamem.html). Peak identification was performed by MACS2 (version 2.1.1, https://hbctraining.github.io/Intro-to-ChIPseq/lessons/05_peak_calling_macs.html) using default parameters. Only peaks present in both biological replicates were considered as confident peaks. Binding motifs in the peak region were discovered by MEME-ChIP (https://meme-suite.org/meme/doc/meme-chip.html?man_type=web). depTools2 (https://deeptools.readthedocs.io/en/develop/) was used for calculating the distribution frequency of peaks near the transcription start site (TSS) and plotting the distribution of peaks on chromosomes. The binding peaks were visualized by Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV, version 2.16.1, http://www.broadinstitute.org/igv/). GO enrichment analysis was performed according to the Gene Ontology Resource database (https://geneontology.org/).

Accession numbers

Sequence data from this study can be obtained in the GDR (https://www.rosaceae.org/) database under the following accession numbers: FvALKBH10B, FvH4_2g24110; FvABF3, FvH4_2g05900; FvSEP3, FvH4_4g23530; FvAREB1, FvH4_2g34330; FvDRM3.1, FvH4_1g24280; FvCHS1, FvH4_7g01160; FvGA3ox1, FvH4_6g30780; FvGH3.1, FvH4_2g04750; FvNCED1, FvH4_3g16730; ACTIN, FvH4_6g22300.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics (version 20) software. All numerical data are showed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) from at least three independent experiments unless otherwise specified in the figure legend and analyzed using unpaired two-sided t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s HSD test. A P-value of <0.05 represents statistically significant. The number of replicates for each experiment is indicated in the figure legends.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability