Abstract

The boreal summer circumglobal teleconnection (CGT) provides a primary predictability source for mid-latitude Northern Hemisphere climate anomalies and extreme events. Here, we show that the CGT’s circulation structure has been displaced westward by half a wavelength since the late 1970s, more severely impacting heatwaves and droughts over East Europe, East Asia, and southwestern North America. We present empirical and modelling evidence of the essential role of El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) in shaping this change. Before the late 1970s, ENSO indirectly promoted CGT by modulating the Indian summer monsoon rainfall (ISMR). Since 1980s, the ENSO–ISMR link has weakened, but the westward-displaced ENSO forcing has been able to directly trigger a Rossby wave response at the exit of the East Asian westerly jet, resulting in a shift of the previous CGT’s North Pacific and downstream centers westward along the westerly jet waveguide. State-of-the-art climate models with prescribed anthropogenic forcing cannot simulate these changes, suggesting that they are driven by natural variability. This work highlights the importance of studying the impacts of changing ENSO to improve seasonal prediction of mid-latitude extreme events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the latitudes with the largest land area and population, the mid-latitude Northern Hemisphere (NH) has suffered from more and more frequent and severe heatwaves and droughts in the context of global warming1,2,3,4, causing massive casualties and economic losses such as Europe heatwaves in 2003, 2010 and 20195,6,7, North America heatwaves in 2018 and 20218,9, and East China heatwaves in 2013 and 202210,11,12. Since there is more difficulty of current dynamical models in forecasting the extratropics than tropics13,14, the mid-latitude NH climate’s predictability urgently needs to be improved to meet the growing need for disaster prevention and mitigation.

As one of the leading modes of the Northern Hemisphere upper-troposphere circulations in boreal summer (June–July–August), the circumglobal teleconnection (CGT) is a stationary Rossby wave pattern embedded in the subtropical westerly jet15. The positive-phase CGT is featured as a zonal 5-wavenumber structure with geographically phase-locked centers of action over the mid-latitude West Asia, East Asia, North Pacific, North America and West Europe16, promoting the descending motion and suppressed the cloud cover and rainfall along the wave train and thereby inducing heatwaves and droughts over the mid-latitude NH17,18 (vice versa). For example, the intense CGT was the direct cause of unprecedented heatwaves in the Yangtze River valley of China, the whole of Europe, and the Great Lakes region of America in 2022 midsummer11,19. Besides the atmospheric internal variability, the CGT is a typical tropical-extratropical teleconnection associated with the tropical monsoon rainfall and El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)20. Specifically, the positive(negative)-phase CGT is significantly modulated by enhanced (suppressed) Indian summer monsoon rainfall (ISMR) and a La Niña (El Niño) developing phase16,21. Notably, the robust ENSO impacts on CGT are essential for seasonal predictions and long-term projections, as ENSO can provide valuable sources of interannual predictability and plenty of references for the CGT and mid-latitude NH summer climate in dynamical models22,23.

The consensus of previous studies is that the ENSO’s effects on CGT are indirect. The summertime development of La Niña always enhances the ISMR, and thus indirectly promotes the CGT. The abundant diabatic heating released by the enhanced ISMR generates a Rossby wave response to its northwest near the westerly jet24,25, propagating downstream along the jet waveguide and forming the 5-wavenumber pattern. In turn, the upper-level anticyclone over the West Asia center of CGT helps maintain the ISMR by enhancing convection and easterly vertical shear to its southeast over the Indian Peninsula. Moreover, pacemaker simulations from the Community Earth System Model version 1 (CESM1) revealed that the CGT pattern is more directly related to sea surface temperature (SST) variability in the Indo-Western Pacific than the eastern tropical Pacific, suggesting another indirect pathway of the ENSO–CGT linkage26. Except for these indirect pathways, the zonally symmetric seesaw pattern forced by ENSO is another reason for the robust ENSO–CGT linkage: The summertime development of La Niña can induce a zonally symmetric low in tropics and thereby favors a consistent high in mid-latitudes due to meridional compensation21.

It has been noted that the CGT has experienced an interdecadal change in structure and variability after the late 1970s27,28,29. The pronounced change of CGT was observed over the North Atlantic, Europe, and Central Asia, due to the enhanced coupling to North African monsoon rainfall and southward shift of upper-level westerly jet27. More importantly, the weakening of major CGT centers, as a response to the decreased ISMR variability27,28, was attributed to the much weakened ENSO–ISMR linkage during the recent period30,31 (Supplementary Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. 2a). However, it is surprised that the explained variance and predictability of CGT are even higher after the late 1970s, which implies an enhanced linkage between the ENSO development and CGT28. Note that the enhanced ENSO–CGT linkage cannot be explained by weakened ENSO–ISMR linkage; other processes must be explored to understand the intensity changes.

Previous studies have extensively examined how the ENSO affects summertime extratropical teleconnections and their stability21,27,32,33, particularly during the transition from El Niño to La Niña, which significantly triggers Rossby wave propagation and warming anomalies over the central and western regions of North America34,35. However, few studies have discussed the possibility that ENSO directly triggers the CGT, even though Ding et al.21 noted the occurrence of the zonally symmetric seesaw pattern across the Northern Hemisphere even under the cases with normal ISMR. Also, previous studies have indicated that the ENSO itself has also exhibited an interdecadal change in the spatial pattern, asymmetry, amplitude, periodicity and impacts36,37,38. The possible role of ENSO’s change in the recent enhanced ENSO–CGT linkage needs to be answered.

Above all, better understanding the recent ENSO’s impacts on CGT motivates us to conduct this study. Here, we find that the recent change of the summertime ENSO can generate a local tropical-extratropical teleconnection over the North Pacific to directly affect the CGT, which is responsible for the structure change of CGT since the late 1970s. This work goes beyond the traditional view that the ENSO effects on CGT are indirect, mainly through modulating the ISMR.

Results

Change of the CGT structure and impacts

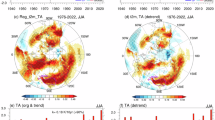

We carried out an empirical orthogonal function (EOF) analysis of the summertime 200-hPa geopotential height anomalies over the NH during the whole period. The second EOF mode (EOF2) and principal component (PC2) are applied to define the CGT16. Consistent with the previous studies27,28, we divide the 70 years of the 1951–2020 period into 1951–1979 and 1980–2020 in this study, and 200-hPa geopotential height anomalies are respectively regressed onto the separated PC2 during these two sub-periods to represent the structure change of CGT, as shown in Fig. 1. This is a common method to investigate the interdecadal structure change of a pattern defined by an EOF mode39. Note that the main results and conclusions are similar when the EOF analysis is conducted independently during each period.

200-hPa geopotential height (shading; gpm) anomalies regressed onto the PC2 of the summertime 200-hPa geopotential height over the Northern Hemisphere during the (a) 1951–1979 period (P1), (b) 1980–2020 period (P2), and (c) their differences (P2–P1). Stippling represents the shading values exceeding the 95% confidence level. The green dotted (black solid) boxes refer to the locations of the observed action centers of CGT during the 1951–1979 (1980–2020) period.

After the late 1970s, the most significant change in the CGT structure is that the North Pacific center was much enhanced with a half-wavelength westward movement combined with the East Asia center. Meanwhile, the downstream centers have correspondingly exhibited a half-wavelength shift along the westerly jet waveguide, with the North America and West Europe centers shifting southwestward and the West Asia center shifting northwestward to the Ural Mountain. Such an interdecadal change of CGT structure coincides nicely with the enhancement of the positive geopotential height anomalies across Eurasia and the North Pacific along 60°N, southwestern North America, and mid-latitude North Atlantic, as well as the negative geopotential height anomalies over West Asia, East Asia and West Europe, as supported by the EOF analysis onto the forty 31-years sliding CGT modes during the whole period (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Furthermore, the impact of CGT on the climate anomalies over the mid-latitude NH considerably differs before and after the late 1970s. The recent westward-displaced CGT has resulted in much more severe heatwaves across most areas of the mid-latitude Eurasia, especially for East Europe and East Asia stretching from eastern China to Japan (Supplementary Fig. 4). The affected region of heatwaves and droughts in North America changed from eastern Canada to southwestern North America (Supplementary Fig. 4), consistent with the southwestward shift of the North America center, which has been proven to be an essential factor for the more frequent, persistent and severe California heatwaves and droughts recently40,41,42.

Role of the ENSO

The above-normal ISMR associated with summertime La Niña development is the main factor responsible for the formation and maintenance of the CGT21. Figure 2 presents the ISMR-related and La Niña-related 200-hPa geopotential height anomalies during the two sub-periods. Before the late 1970s, the effects of the ISMR and La Niña on the mid-latitude upper-troposphere circulations were much similar to each other (Fig. 2a vs. c), consistent with the traditional CGT structure (Fig. 1a), indicating the indirect effects of ENSO on the CGT that imposed by the ISMR16. After the late 1970s, the independent effects of ISMR on the mid-latitude upper-troposphere circulations remain almost unchanged (Fig. 2b vs. e). The relatively weakened West Asia and East Asia centers should be attributed to the weakened ISMR variability since the late 1970s27. The most robust difference between the two periods appears in the La Niña-induced pattern: The enhanced North Pacific center has shifted westward and combined with the East Asia center, and the North America center and West Europe center have shifted southwestward, as well as the northwestward shift of the West Asia center (Fig. 2c vs. f). These features correspond well to the CGT structure during the latter period (Fig. 1b), suggesting the essential role of ENSO in the recent westward movement of the CGT structure.

200-hPa geopotential height (shading; gpm) anomalies regressed onto the (a) ISMR, (b) ISMR with the effects of ENSO removed, and (c) inverted summertime Niño 3.4 index during the 1951–1979 period. d–f Same as (a–c), but for the 1980–2020 period. Stippling represents the shading values exceeding the 95% confidence level. The green dotted (black solid) boxes refer to the locations of the observed action centers of the circumglobal teleconnection (CGT) during the 1951–1979 (1980–2020) period.

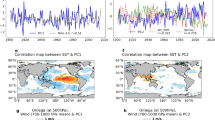

By performing the composite analysis during the anomalous summertime ENSO years and EOF analysis onto the summertime tropical Pacific SST, we find that the structure of the summertime ENSO has also experienced a considerable interdecadal change: The center of the SST anomaly shifted westward from the equatorial eastern Pacific and the Chilean coast to the equatorial central Pacific between the two sub-periods (Fig. 3a–c; Supplementary Fig. 5), consistent with the increased central Pacific-type ENSO recently37,43,44,45,46. Note that this ENSO structure change is symmetric for both La Niña and El Niño when composited (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Composite differences of sea surface temperature (SST) (shading; K) anomalies between the summertime La Niña (Niño 3.4 indices <–0.5) and El Niño (Niño 3.4 indices > 0.5) years during the (a) 1951–1979 period (P1), (b) 1980–2020 period (P2), and (c) their differences (P2–P1). d–f Same as (a–c), but for the rainfall (shading; mm day-1), 850-hPa velocity potential (contours at the interval of 2 x 10-5 m2 s-1; red solid contours are positive and blue dotted contours are negative), and 850-hPa divergence wind (vectors; m s-1) anomalies. Stippling represents the shading values exceeding the 95% confidence level.

As a result, the descending motion of the Walker Circulation induced by the summertime La Niña shifts westward after the late 1970s, leading to the suppressed convection and rainfall over the tropical western North Pacific (TWNP) (Fig. 3d–f). Due to the convection-induced diabatic cooling, a tropical baroclinic structure is formed over the TWNP (Fig. 4b). It should be noted that the background zonal flow exhibits a robust easterly shear over the TWNP (Fig. 4f), which is conducive to conveying the thermal-induced baroclinic disturbances to the extratropic with opposite signal and generating a tropical-extratropical teleconnection39,47. Accordingly, the TWNP baroclinic structure propagates northward and is converted into the extratropical barotropic disturbance with consistent negative relative vorticity anomalies to eastern Japan (Fig. 4d). Because the high-pressure barotropic disturbance to eastern Japan is located near the exit region of the westerly jet, the North Pacific center tends to be formed there as a Rossby wave response and further propagates downstream along the westerly jet waveguide (Fig. 4b). Thus, the North Pacific center during the latter period is phase-locked to the eastern Japan and combined with the East Asia center, accompanied by a half-wavelength westward shift of the CGT centers downstream.

200-hPa stream function (shading; m2 s–1) and horizontal wave activity flux (green vector; m2 s–2; only the values above 2 x 10−2 m2 s–2 are shown) anomalies regressed onto the inverted summertime Niño 3.4 index during the (a) 1951–1979 period and (b) 1980–2020 period. Hovmöller plot of relative vorticity anomalies (shading; 10–6 s–1) from the surface to the 100-hPa level regressed onto the inverted summertime Niño 3.4 index (c) zonally averaged over 170°E–150°W (black box in a) during the 1951–1979 period, and (d) zonally averaged over 130°E–170°E (black box in b) during the 1980–2020 period. Zonal wind of the basic flow (e) averaged over 5°N–20°N/170°E–140°W during the 1951–1979 period, and (f) averaged over 5°N–20°N/100°E–170°E during the 1980–2020 period. Stippling represents the shading values exceeding the 95% confidence level.

In contrast, the La Niña-induced diabatic cooling is located over the tropical central North Pacific (TCNP) before the late 1970s (Fig. 3a, d), where the easterly shear of the background zonal flow is absent due to the upper-level westerly winds east of 170°E (Fig. 4e; Supplementary Fig. 7). Thus, the impacts of the tropical thermal-induced baroclinic disturbance are unable to be conveyed to the extratropic, as evidenced by the unrobust and interrupted tropical-extratropical teleconnection around 30°N (Fig. 4c). The CGT action center over the North Pacific should be formed by the upstream disturbances. Thus, the ENSO impacts on CGT were mainly imposed via the ISMR during the former period.

Role of the westerly jet

The subtropical westerly jet plays a vital role in the formation and propagation of CGT. The barotropic energy conversion (CK) is applied to measure the efficiency of kinetic energy conversion from the basic flow to anomalies, which is dominant at the jet exit region due to the barotropic instability. In response to the summertime La Niña, the energy conversion between the anomalous CGT and westerly jet shift westward (eastward) and becomes more (less) efficient after (before) the late 1970s, as evidenced by the much stronger (weaker) positive 200-hPa CK anomalies to the eastern Japan (over the North Pacific) (Fig. 5b vs. c). The CGT disturbances have been more westerly and closer to the East Asian westerly jet exit region since the late 1970s, induced by the westward shift of the summertime ENSO mentioned above. On the other hand, the recently enhanced East Asian westerly jet at its exit region could convey more kinetic energy to CGT and reinforce the barotropic instability (Fig. 5a), which should be another cause for the stronger CK. These results can explain the much stronger North Pacific center during the recent period.

a Differences of the climatological-mean 200-hPa zonal wind (shading; m s–1) between the two period (1980–2020 (P2) minus 1951–1979 (P1)). The blue box represents the exit region of the East Asian westerly jet. The green line represents the westerly jet axis, defined as the maximum value between 30°N–60°N of the climatological-mean 200 hPa zonal wind during the 1951–2020 period. 200-hPa barotropic energy conversion (CK) (shading; 10–5 m2 s–3) based on the regressed anomalies onto the inverted summertime Niño 3.4 index and the climatological-mean 200-hPa wind (vector; m s–1) during the (b) 1951–1979 period and (c) 1980–2020 period.

Additionally, the robust southward shift of the subtropical westerly jet over the North Pacific and North Atlantic (Fig. 5a) should contribute to the southward movement of the North America and West Europe centers after the late 1970s (Fig. 1c). The stronger westerly jet at the jet exit region over Europe (Fig. 5a) helps promote the occurrence of Ural Mountain center (Fig. 1c), due to the stronger barotropic instability and energy conversion there.

Numerical experiments validations

The Pacific pacemaker experiment and the fully coupled pre-industry large ensemble (LE) experiment based on the Community Earth System Model version 2 (CESM2) are conducted for validation. The outputs of the Pacific pacemaker experiment represent the atmosphere response to the observed tropical central-eastern Pacific SST anomalies (i.e., ENSO). Similar to the observations, the half-wavelength westward movement of the North Pacific center and other centers downstream after the 1970s was successfully reproduced (Fig. 6b vs. Fig. 2f).

200-hPa geopotential height (shading; gpm) anomalies regressed onto the inverted summertime Niño 3.4 index in the Community Earth System Model version 2 (CESM2) Pacific pacemaker experiment during the (a) 1951–1979 period, (b) 1980–2019 period, and (c) their differences. The composite 200-hPa geopotential height (shading; gpm) anomalies of the (d) eastern Pacific-type (Cluster 1), (e) central Pacific-type (Cluster 2) and (f) their differences in the CESM2 large ensemble (LE) experiment. Stippling represents the shading variability exceeding the 95% confidence level.

In order to eliminate the effect of small sample sizes of observations, the composite difference results in the pre-industry LE are presented in Fig. 6d–f. The summertime ENSO years are selected among the last 1000 years according to the summertime Niño 3.4 index, which is divided into the eastern Pacific type (Cluster 1) and the central Pacific type (Cluster 2) by comparing the intensity of Niño 3 and Niño 4 indices (Supplementary Fig. 8). The CGT pattern associated with the westward-displacement ENSO is almost similar with the observed CGT since the late 1970s (Fig. 6e vs. Fig. 1b). Above all, both the pacemaker and pre-industry LE experiments validate the essential role of ENSO in the recent CGT structure.

In comparison, the forced patterns show much weaker amplitude in both the pacemaker experiment before the late 1970s (Fig. 6a vs. b) and the eastern Pacific type experiment (Fig. 6d vs. e). Although the traditional CGT pattern during the former period fails to be reproduced, the models can simulate it when regressed onto the ISMR in both experiments (Supplementary Fig. 9), consistent with Yu et al.48. The above results support our conclusion that the linkage between ENSO and CGT during the former period is indirect.

Additionally, the linear baroclinic model (LBM) is conducted to verify the impact of the position changes of upstream disturbances on the downstream propagation of the CGT structure. Consistent with the observation (Fig. 1), the westward shift of the barotropic disturbances over the mid-latitude North Pacific leads to the enhanced and westward-displaced North Pacific center, as well as a half-wavelength westward movement of the North America center from eastern Canada to southwestern North America (Supplementary Fig. 10a vs. b). The less westward shift of the West Europe center may be attributed to the LBM limitations in reproducing this center and the rapid signal damping downstream.

Discussion

In this study, we have shown that the summertime ENSO has exerted a direct effect on the CGT after the late 1970s, leading to the interdecadal change of the CGT structure, with a half-wavelength westward shift of the North Pacific center and other centers downstream. The specific mechanisms are summarized in the schematic diagram in Fig. 7. Before the late 1970s, the summertime ENSO that centered in the equatorial eastern Pacific indirectly affected the CGT by modulating the ISMR, which can trigger a zonal 5-wavenumber structure with geographically phase-locked centers over the mid-latitude West Asia, East Asia, the North Pacific, North America and West Europe (Fig. 7a). After the late 1970s, the anomalous center of the summertime ENSO has exhibited a significant westward shift from the equatorial eastern Pacific to the equatorial central Pacific. The induced diabatic cooling shifted to the TWNP, where the zonal basic flow exhibits a robust easterly vertical shear. The easterly vertical shear can convert the La Niña-induced baroclinic disturbances to the extratropical barotropic disturbances via triggering a tropical-extratropical teleconnection, leading to an enhanced North Pacific center and an overall westward shift of the whole CGT pattern along the westerly jet waveguide (Fig. 7b). Meanwhile, the interdecadal change of the subtropical westerly jet also matters: the recently enhanced East Asian westerly jet at its exit region favors a more robust Rossby response near the North Pacific center, whereas the southward shift of the westerly jet over North America and North Atlantic contributes to the southward movement of the CGT centers there. The experiments of the CESM2 Pacific pacemaker, pre-industry LE, and the LBM jointly validate the essential role of ENSO in shaping the CGT structure change.

The formation mechanisms of CGT during the (a) 1951–1979 period, (b) 1980–2019 period. The red centers at mid-latitudes represent the action centers of CGT, and the dotted red arrow represents the waveguide. The blue center in the equatorial Pacific refers to the location of the La Niña center. See the text for details.

This work may be helpful for future model improvements in predictions and projections. Despite the highly-predictable interannual intensity of CGT sourced from ENSO, the CGT’s centers of action simulations are still facing challenges22,49. A deeper understanding of the recent CGT structure change should help improve the seasonal predictions of the mid-latitude NH heatwaves and droughts associated with the ENSO. Moreover, a better understanding of the ENSO–CGT linkage may provide some references for constraining extensive ensemble simulations to improve the projection accuracy of future climate change over the mid-latitude NH.

A question arose: Why has the summertime ENSO shifted westward after the late 1970s? We argue that global warming may not be the leading cause, as the historical simulations from 24 models in Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) cannot reproduce the recent change of the summertime ENSO and CGT structure (Supplementary Fig. 11). Note that the summertime ENSO before the late 1970s naturally evolved in the equatorial eastern Pacific and developed into the following winter. In comparison, the summertime ENSO after the late 1970s is much more associated with the Pacific meridional mode (PMM) in the preceding winter (December–January–February) and spring (March–April–May) (Supplementary Fig. 12). As suggested by the previous studies50,51,52,53, the extratropical North Pacific forcings promote the occurrences of the central Pacific-type ENSO through the wind-evaporation-SST feedback, trade wind charging, and Rossby wave response mechanisms. They thus may contribute to the recent westward shift of the summertime ENSO.

Methods

Observational data

The observed monthly rainfall data derived from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Precipitation Reconstruction (PREC) with a horizontal resolution of 2.5° × 2.5°, which merges the observed rainfall over land, is used for the calculation of the ISMR. The global geopotential height, wind, rainfall and surface air temperature are given by the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Reanalysis 5 (ERA5), with a 0.25° × 0.25° horizontal resolution. The selection of global rainfall is due to the fact that ERA5 is more consistent with Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) than NOAA PERC during 1980–2020 period (Supplementary Fig. 13). The SST data are from the NOAA Extended Reconstruction of Historical Sea Surface Temperature version 5 (ERSSTv5) at a 2.0° × 2.0° horizontal resolution54. The 3-months timescale of the standardized precipitation-evapotranspiration index (SPEI) is given by the global 0.5° gridded SPEI base v2.9 dataset based on the Climatic Research Unit gridded Time Series version 4.07 (CRU TS 4.07) data to measure the droughts55. The anomalies are calculated by the original values minus the climatological mean during the 1951‒2020 period and detrended to exclude the potential effect of global warming. The summertime results in this study refer to the average values of June, July and August (JJA). The robustness of this work has been confirmed by repeating with other alternative datasets such as JRA-55 and HadISST.

Numerical experiments

Based on the Community Earth System Model version 2 (CESM2), the Pacific pacemaker experiment and pre-industry large ensemble (LE) experiment conducted by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) are applied for the validation of statistical evidence. The Pacific pacemaker experiment is forced by the observed tropical Pacific SST derived from the ERSSTv5 dataset with 10 simulations during the 1880–2019 period. The nudging area is 15°S–15°N from the dateline to American coast. The linearly tapering buffer area extends 5 degrees of latitude to the south and north in the eastern Pacific, and shapes as a wedge toward the Maritime continent west of the dateline. The coupled system of model in the rest areas evolves freely. The Pacific pacemaker experiment represents the atmosphere response to the observed external forcing by ENSO without considering the effects of the other oceans (https://www.cesm.ucar.edu/working-groups/climate/simulations/cesm2-pacific-pacemaker). The LE experiment is a fully-coupled free run at the pre-industrial (1850) level with a large sample of 1200 years, which is widely used to measure the internal climate evolutions without the anthropogenic forcing56.

The LBM is an ideal model based on the primitive equations linearized at a given state. Two dry experiments are designed to verify the impact of the position changes of upstream disturbances on the downstream propagation of the CGT structure. The EXP-WP experiment is forced by an anticyclonic vorticity anomaly over mid-latitude western Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 10b), representing the disturbances on jets associated with westward-shifted ENSO during the recent period. In comparison, the EXP-CP experiment is forced by the same prescribed relative vorticity, but over the central Pacific consistent with the North Pacific CGT center during the former period (Supplementary Fig. 10a). The vertical profile of vorticity is featured as a barotropic structure following a gamma function with a maximum value of about 4 x 10–10 s–2 at 200 hPa (Supplementary Fig. 10c). The experiments are set with a horizontal resolution of T42 and 20 sigma levels (T42l20). The average response between 20 and 30 days is regarded as a steady result.

ISMR and ENSO indices

The ISMR index is defined as the normalized rainfall anomalies over the Indian summer monsoon region (5°‒30°N and 70°‒90°E) based on the NOAA PREC dataset21. The Niño 3, Niño 4 and Niño 3.4 indices are defined as the normalized SST anomalies over 5°S‒5°N/90°W‒150°W, 5°S‒5°N/160°E‒150°W, and 5°S‒5°N/120°W‒170°W, respectively.

Statistical tools and significance

The barotropic energy conversion (CK) is applied to quantitatively measure the contributions of the westerly jet57,58, which is given by:

The overbars (primes) denote the climatology (anomaly), and u (v) denotes the zonal (meridional) winds at a certain pressure level. Positive CK stands for gaining kinetic energy from the climatological mean flow to the anomalies.

The main statistical tools in this study include the empirical orthogonal function (EOF), composite, correlation and regression analysis. Commonly, the CGT can be defined as the second EOF mode (EOF2) of the summertime Northern Hemisphere (NH) 200-hPa geopotential height or the first maximum covariance analysis (MCA) mode of the tropical rainfall and NH 200 hPa geopotential height16. In this study, the EOF analysis is applied to identify the CGT, and the main conclusions remain unchanged when using the MCA analysis. The stationary wave activity flux is calculated to depict Rossby wave propagations59. The Student’s t-test is applied to examine the statistical significance level in composite, difference, correlation, and regression analysis.

Data availability

All the raw data used in this study are publicly available online. The global geopotential height, wind, rainfall and surface air temperature data are available in the ERA5. The SST data are available in the ERSSTv5 (https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.noaa.ersst.v5.html). The rainfall data used for the calculation of the ISMR are available in the NOAA PREC. The SPEI are available in the SPEI v2.9 database (https://digital.csic.es/handle/10261/332007). The numerical experiment data are available in the CESM2 Pacific pacemaker and LE experiment outputs (https://www.cesm.ucar.edu/working-groups/climate/simulations). The numerical historical simulations are available in the CMIP6.

Code availability

Code for the main results is available on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14467595.

References

Thompson, V. et al. The most at-risk regions in the world for high-impact heatwaves. Nat. Commun. 14, 2152 (2023).

Kreibich, H. et al. The challenge of unprecedented floods and droughts in risk management. Nature 608, 80–86 (2022).

Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S. E. & Lewis, S. C. Increasing trends in regional heatwaves. Nat. Commun. 11, 3357 (2020).

Seneviratne, S. I., Luethi, D., Litschi, M. & Schaer, C. Land-atmosphere coupling and climate change in Europe. Nature 443, 205–209 (2006).

Luterbacher, J., Dietrich, D., Xoplaki, E., Grosjean, M. & Wanner, H. European seasonal and annual temperature variability, trends, and extremes since 1500. Science 303, 1499–1503 (2004).

Trenberth, K. E. & Fasullo, J. T. Climate extremes and climate change: The Russian heat wave and other climate extremes of 2010. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 117, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012jd018020 (2012).

Xu, P., Wang, L., Liu, Y., Chen, W. & Huang, P. The record-breaking heat wave of June 2019 in Central Europe. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 21, https://doi.org/10.1002/asl.964 (2020).

Kornhuber, K. et al. Extreme weather events in early summer 2018 connected by a recurrent hemispheric wave-7 pattern. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab13bf (2019).

Dong, Z., Wang, L., Xu, P., Cao, J. & Yang, R. Heatwaves Similar to the Unprecedented One in Summer 2021 Over Western North America Are Projected to Become More Frequent in a Warmer World. Earths Future 11, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022ef003437 (2023).

Sun, Y. et al. Rapid increase in the risk of extreme summer heat in Eastern China. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 1082–1085 (2014).

Tang, S. et al. Linkages of unprecedented 2022 Yangtze River Valley heatwaves to Pakistan flood and triple-dip La Niña. npj Climate Atmos. Sci. 6, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-023-00386-3 (2023).

Tang, S. et al. Predictability of the unprecedented 2022 late summer Yangtze River Valley and Tibetan Plateau heatwaves by the NCEP CFSv2. Atmos. Res. 296, 107053 (2023).

Wang, B. et al. Advance and prospectus of seasonal prediction: assessment of the APCC/CliPAS 14-model ensemble retrospective seasonal prediction (1980-2004). Clim. Dyn. 33, 93–117 (2009).

Saha, S. et al. The NCEP Climate Forecast System Version 2. J. Clim. 27, 2185–2208 (2014).

Barnston, A. G. & Livezey, R. E. Classification, seasonality and persistence of low-frequency atmospheric circulation patterns. Mon. Wea. Rev. 115, 1083–1126 (1987).

Ding, Q. H. & Wang, B. Circumglobal teleconnection in the Northern Hemisphere summer. J. Clim. 18, 3483–3505 (2005).

Screen, J. A. & Simmonds, I. Amplified mid-latitude planetary waves favour particular regional weather extremes. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 704–709 (2014).

Lee, M.-H., Lee, S., Song, H.-J. & Ho, C.-H. The Recent Increase in the Occurrence of a Boreal Summer Teleconnection and Its Relationship with Temperature Extremes. J. Clim. 30, 7493–7504 (2017).

Zhang, L. X. et al. Understanding and Attribution of Extreme Heat and Drought Events in 2022: Current Situation and Future Challenges. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 40, 1941–1951 (2023).

Trenberth, K. E. et al. Progress during TOGA in understanding and modeling global teleconnections associated with tropical sea surface temperatures. J. Geophys. Res. 103, 14291–14324 (1998).

Ding, Q., Wang, B., Wallace, J. M. & Branstator, G. Tropical-Extratropical Teleconnections in Boreal Summer: Observed Interannual Variability. J. Clim. 24, 1878–1896 (2011).

Lee, J.-Y. et al. How predictable is the northern hemisphere summer upper-tropospheric circulation? Clim. Dyn. 37, 1189–1203 (2011).

Beverley, J. D., Woolnough, S. J., Baker, L. H., Johnson, S. J. & Weisheimer, A. The northern hemisphere circumglobal teleconnection in a seasonal forecast model and its relationship to European summer forecast skill. Clim. Dyn. 52, 3759–3771 (2019).

Gill, A. E. Some simple solutions for heat-induced tropical circulation. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 106, 447–462 (1980).

Fu, Z.-H., Zhou, W., Xie, S.-P., Zhang, R. & Wang, X. Dynamic pathway linking Pakistan flooding to East Asian heatwaves. Sci. Adv. 10, eadk9250 (2024).

Lin, Y. H., Fosu, B. & Ikuyajolu, O. J. The impact of tropical SST variability on the northern hemisphere circumglobal teleconnection pattern. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1033789 (2023).

Wang, H., Wang, B., Huang, F., Ding, Q. & Lee, J.-Y. Interdecadal change of the boreal summer circumglobal teleconnection (1958-2010). Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L12704 (2012).

Lee, J.-Y. & Ha, K.-J. Understanding of Interdecadal Changes in Variability and Predictability of the Northern Hemisphere Summer Tropical-Extratropical Teleconnection. J. Clim. 28, 8634–8647 (2015).

Liu, Y., Zhou, W., Qu, X. & Wu, R. G. An Interdecadal Change of the Boreal Summer Silk Road Pattern around the Late 1990s. J. Clim. 33, 7083–7100 (2020).

Ashrit, R. G., Kumar, K. R. & Kumar, K. K. ENSO-Monsoon relationships in a greenhouse warming scenario. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 1727–1730 (2001).

Naidu, C. V. et al. Is summer monsoon rainfall decreasing over India in the global warming era? J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 114, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008jd011288 (2009).

Martija-Díez, M., Rodríguez-Fonseca, B. & López-Parages, J. ENSO Influence on Western European Summer and Fall Temperatures. J. Clim. 34, 8013–8031 (2021).

Martija-Díez, M., López-Parages, J., Rodríguez-Fonseca, B. & Losada, T. The stationarity of the ENSO teleconnection in European summer rainfall. Clim. Dyn. 61, 489–506 (2023).

Jong, B. T., Ting, M. F., Seager, R. & Anderson, W. B. ENSO Teleconnections and Impacts on US Summertime Temperature during a Multiyear La Niña Life Cycle. J. Clim. 33, 6009–6024 (2020).

Jong, B. T., Ting, M. F. & Seager, R. Assessing ENSO Summer Teleconnections, Impacts, and Predictability in North America. J. Clim. 34, 3629–3644 (2021).

An, S. I. & Wang, B. Interdecadal change of the structure of the ENSO mode and its impact on the ENSO frequency. J. Clim. 13, 2044–2055 (2000).

Ashok, K. & Yamagata, T. The El Niño with a difference. Nature 461, 481–484 (2009).

Sun, L. Y., Yang, X. Q., Tao, L. F., Fang, J. B. & Sun, X. G. Changing Impact of ENSO Events on the Following Summer Rainfall in Eastern China since the 1950s. J. Clim. 34, 8105–8123 (2021).

Xu, P. Q., Wang, L., Chen, W., Feng, J. & Liu, Y. Y. Structural Changes in the Pacific-Japan Pattern in the Late 1990s. J. Clim. 32, 607–621 (2019).

Steiger, N. J., Smerdon, J. E., Seager, R., Williams, A. P. & Varuolo-Clarke, A. M. ENSO-driven coupled megadroughts in North and South America over the last millennium. Nat. Geosci. 14, 739–744 (2021).

Yoon, J. H. et al. Increasing water cycle extremes in California and in relation to ENSO cycle under global warming. Nat. Commun. 6, 8657 (2015).

Williams, A. P., Cook, B. I. & Smerdon, J. E. Rapid intensification of the emerging southwestern North American megadrought in 2020-2021. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 232–234 (2022).

Geng, T. et al. Emergence of changing Central-Pacific and Eastern-Pacific El Niño-Southern Oscillation in a warming climate. Nat. Commun. 13, 6616 (2022).

Shin, N. Y. et al. More frequent central Pacific El Niño and stronger eastern pacific El Niño in a warmer climate. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 5443 (2022).

Yeh, S.-W. et al. El Niño in a changing climate. Nature 461, 511–514 (2009).

Lee, T. & McPhaden, M. J. Increasing intensity of El Niño in the central-equatorial Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, 14603 (2010).

Kosaka, Y. & Nakamura, H. Structure and dynamics of the summertime Pacific-Japan teleconnection pattern. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 132, 2009–2030 (2006).

Yu, H. Z., Zhou, T. J. & He, L. Q. Indian Summer Monsoon Precipitation Dominates the Reproduction of Circumglobal Teleconnection Pattern: A Comparison of CMIP5 and CMIP6 Models. J. Clim. 37, 5009–5023 (2024).

Tang, S. K. et al. Asymmetry of probabilistic prediction skills of the midsummer surface air temperature over the middle and lower reach of the Yangtze River valley. Clim. Dyn. 57, 3285–3302 (2021).

Jia, F., Cai, W. J., Gan, B. L., Wu, L. X. & Di Lorenzo, E. Enhanced North Pacific impact on El Niño/Southern Oscillation under greenhouse warming. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 840–847 (2021).

Amaya, D. J. The Pacific Meridional Mode and ENSO: a Review. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 5, 296–307 (2019).

Chen, S. et al. Enhanced impact of the Aleutian Low on increasing the Central Pacific ENSO in recent decades. npj Climate Atmos. Sci. 6, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-023-00350-1 (2023).

Wang, B. et al. Understanding the recent increase in multiyear La Niñas. Nat. Clim. Change 13, 1075–1081 (2023).

Huang, B. et al. Extended Reconstructed Sea Surface Temperature, Version 5 (ERSSTv5): Upgrades, Validations, and Intercomparisons. J. Clim. 29, 8179–8205 (2016).

Vicente-Serrano, S. M., Begueria, S., Lopez-Moreno, J. I., Angulo, M. & El Kenawy, A. A New Global 0.5° Gridded Dataset (1901−2006) of a Multiscalar Drought Index: Comparison with Current Drought Index Datasets Based on the Palmer Drought Severity Index. J. Hydrometeorol. 11, 1033–1043 (2010).

Yeager, S. G. et al. Predicting near-term changes in the earth system: A large ensemble of initialized decadal prediction simulations using the Community Earth System Model. Bull. Am. Meteorol.Soc. 99, 1867–1886 (2018).

Hoskins, B. J., James, I. N. & White, G. H. The shape, propagation and mean-flow interaction of large-scale weather systems. J. Atmos. Sci. 40, 1595–1612 (1983).

Simmons, A. J., Wallace, J. M. & Branstator, G. W. Barotropic wave propagation and instability, and atmospheric teleconnection patterns. J. Atmos. Sci. 40, 1363–1392 (1983).

Takaya, K. & Nakamura, H. A formulation of a phase-independent wave-activity flux for stationary and migratory quasigeostrophic eddies on a zonally varying basic flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 58, 608–627 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42261144687, No. 42130610, No. U2342211 and No. 42175028), the Project supported by Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai) (No.SML2023SP208), the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (2022CFD014), and the Science and Technology Program of Gansu Province (No.24JRRA482). BW acknowledge support by NSF award No. 2025057.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.T., S.Q. and T.F. conceived the idea for the study. S.T. downloaded the data, made the calculations, created the Figures. S.T. and S.Q. wrote the paper. B.W., T.F., F.L., X.Z, G.F. and W.D. contributed to the revision. All authors discussed the results throughout the whole process.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, S., Qiao, S., Wang, B. et al. Recent changes in ENSO’s impacts on the summertime circumglobal teleconnection and mid-latitude extremes. Nat Commun 16, 646 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-55925-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-55925-8

This article is cited by

-

Early summer climate variability over Northern China modulated by Indian monsoon activity

Climate Dynamics (2026)

-

ENSO-induced latitudinal variation of zonal wind modulates heatwaves over Northwestern South Asia

Theoretical and Applied Climatology (2026)

-

Volcanic eruptions disrupt ENSO teleconnections with land summer temperature

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Quantifying the ENSO’s multifaceted influence on atmospheric predictability across variables and vertical levels

Climate Dynamics (2025)

-

Emerging Teleconnected Patterns Enhance Predictability of East Asian Summer Extremes

Journal of Meteorological Research (2025)